User login

Translating the 2019 AAD-NPF Guidelines of Care for the Management of Psoriasis With Biologics to Clinical Practice

Psoriasis is a systemic immune-mediated disorder characterized by erythematous, scaly, well-demarcated plaques on the skin that affects approximately 3% of the world’s population.1 The disease is moderate to severe for approximately 1 in 6 individuals with psoriasis.2 These patients, particularly those with symptoms that are refractory to topical therapy and/or phototherapy, can benefit from the use of biologic agents, which are monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins engineered to inhibit the action of cytokines that drive psoriatic inflammation.

In February 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released an updated set of guidelines for the use of biologics in treating adult patients with psoriasis.3 The prior guidelines were released in 2008 when just 3 biologics—etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab—were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of psoriasis. These older recommendations were mostly based on studies of the efficacy and safety of biologics for patients with psoriatic arthritis.4 Over the last 11 years, 8 novel biologics have gained FDA approval, and numerous large phase 2 and phase 3 trials evaluating the risks and benefits of biologics have been conducted. The new guidelines contain considerably more detail and are based on evidence more specific to psoriasis rather than to psoriatic arthritis. Given the large repertoire of biologics available today and the increased amount of published research regarding each one, these guidelines may aid dermatologists in choosing the optimal biologic and managing therapy.

The AAD-NPF recommendations discuss the mechanism of action, efficacy, safety, and adverse events of the 10 biologics that have been FDA approved for the treatment of psoriasis as of March 2019, plus risankizumab, which was pending FDA approval at the time of publication and was later approved in April 2019. They also address dosing regimens, potential to combine biologics with other therapies, and different forms of psoriasis for which each may be effective.3 The purpose of this discussion is to present these guidelines in a condensed form to prescribers of biologic therapies and review the most clinically significant considerations during each step of treatment. Of note, we highlight only treatment of adult patients and do not discuss information relevant to risankizumab, as it was not FDA approved when the AAD-NPF guidelines were released.

Choosing a Biologic

Biologic therapy may be considered for patients with psoriasis that affects more than 3% of the body’s surface and is recalcitrant to localized therapies. There is no particular first-line biologic recommended for all patients with psoriasis; rather, choice of therapy should be individualized to the patient, considering factors such as body parts affected, comorbidities, lifestyle, and drug cost.

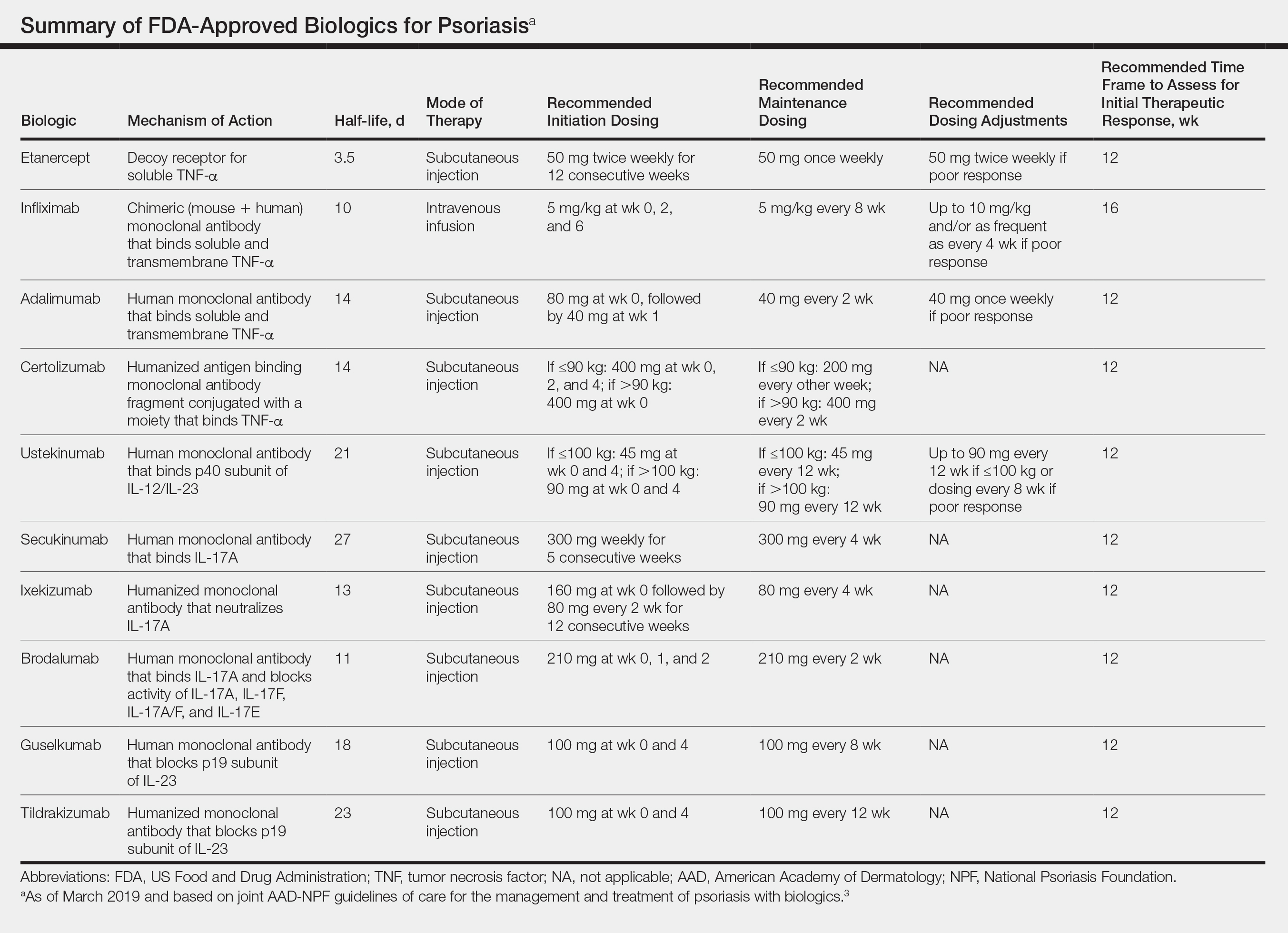

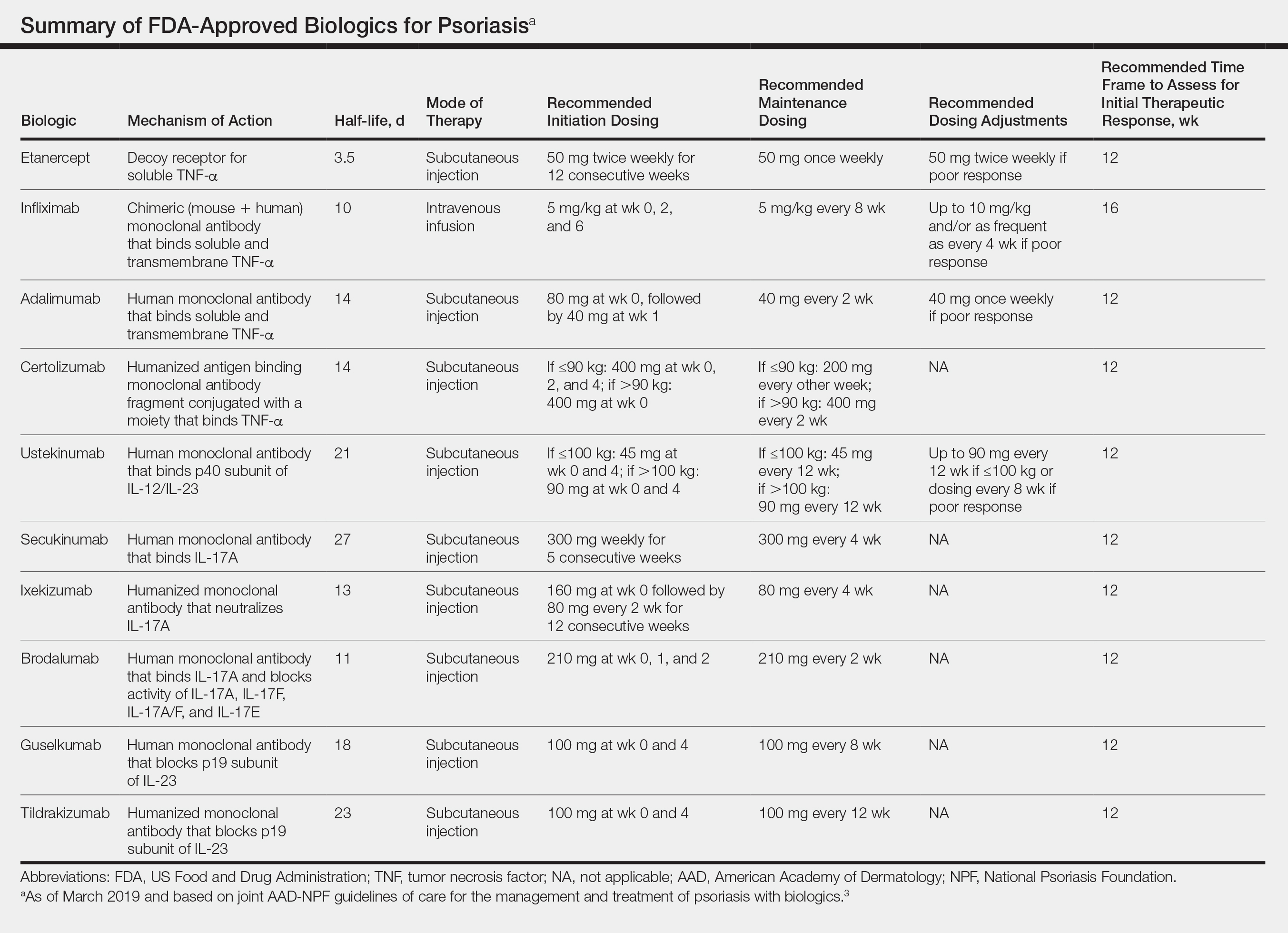

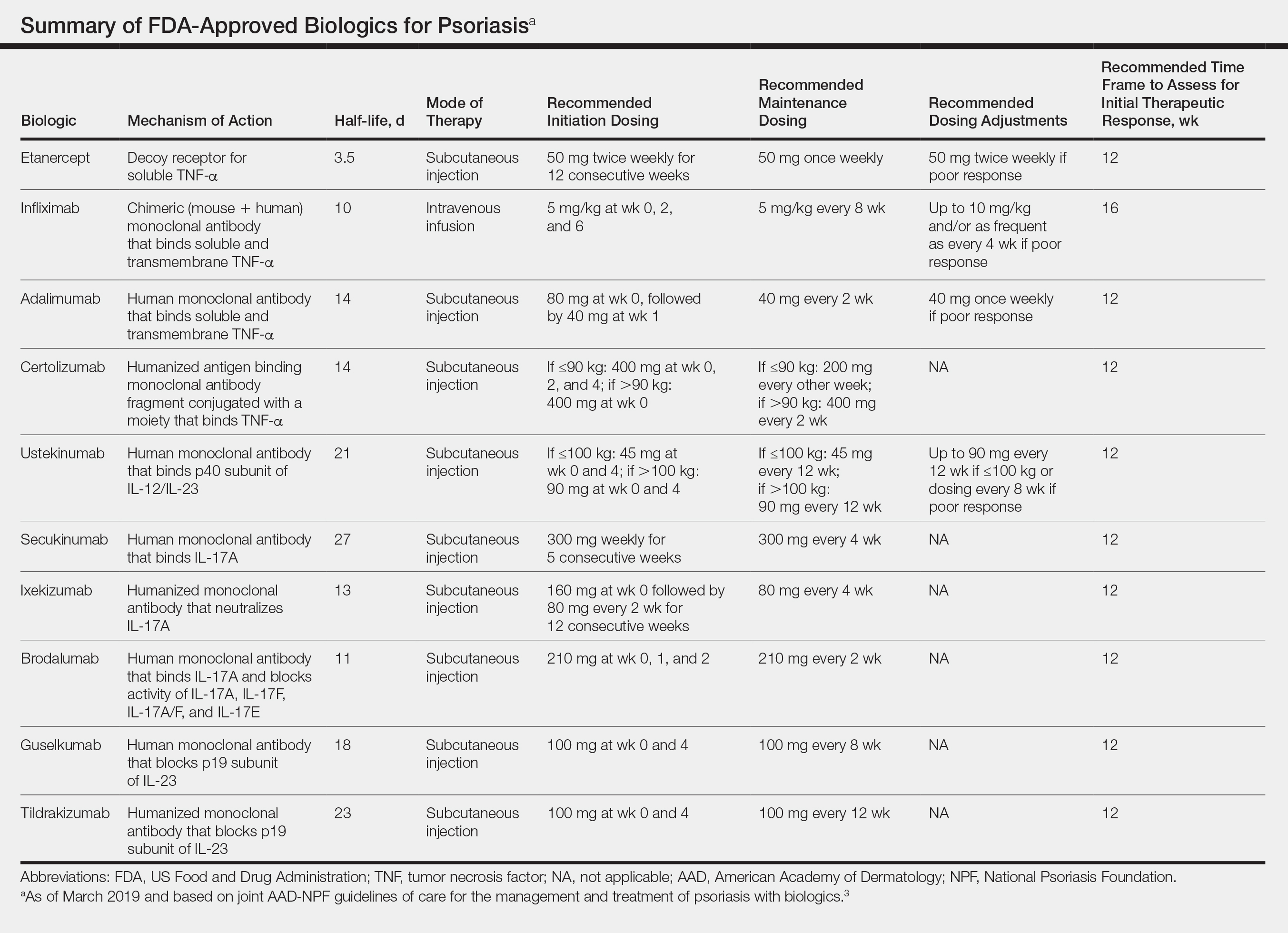

All 10 FDA-approved biologics (Table) have been ranked by the AAD and NPF as having grade A evidence for efficacy as monotherapy in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque-type psoriasis. Involvement of difficult-to-treat areas may be considered when choosing a specific therapy. The tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors etanercept and adalimumab, the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab, and the IL-23 inhibitor guselkumab have the greatest evidence for efficacy in treatment of nail disease. For scalp involvement, etanercept and guselkumab have the highest-quality evidence, and for palmoplantar disease, adalimumab, secukinumab, and guselkumab are considered the most effective. The TNF-α inhibitors are considered the optimal treatment option for concurrent psoriatic arthritis, though the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab and the IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab also have shown grade A evidence of efficacy. Of note, because TNF-α inhibitors received the earliest FDA approval, there is most evidence available for this class. Therapies with lower evidence quality for certain forms of psoriasis may show real-world effectiveness in individual patients, though more trials will be necessary to generate a body of evidence to change these clinical recommendations.

In pregnant women or those are anticipating pregnancy, certolizumab may be considered, as it is the only biologic shown to have minimal to no placental transfer. Other TNF-α inhibitors may undergo active placental transfer, particularly during the latter half of pregnancy,5 and the greatest theoretical risk of transfer occurs in the third trimester. Although these drugs may not directly harm the fetus, they do cause fetal immunosuppression for up to the first 3 months of life. All TNF-α inhibitors are considered safe during lactation. There are inadequate data regarding the safety of other classes of biologics during pregnancy and lactation.

Overweight and obese patients also require unique considerations when choosing a biologic. Infliximab is the only approved psoriasis biologic that utilizes proportional-to-weight dosing and hence may be particularly efficacious in patients with higher body mass. Ustekinumab dosing also takes patient weight into consideration; patients heavier than 100 kg should receive 90-mg doses at initiation and during maintenance compared to 45 mg for patients who weigh 100 kg or less. Other approved biologics also may be utilized in these patients but may require closer monitoring of treatment efficacy.

There are few serious contraindications for specific biologic therapies. Any history of allergic reaction to a particular therapy is an absolute contraindication to its use. In patients for whom IL-17 inhibitor treatment is being considered, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should be ruled out given the likelihood that IL-17 could reactivate or worsen IBD. Of note, TNF-α inhibitors and ustekinumab are approved therapies for patients with IBD and may be recommended in patients with comorbid psoriasis. Phase 2 and phase 3 trials have found no reactivation or worsening of IBD in patients with psoriasis who were treated with the IL-23 inhibitor tildrakizumab,6 and phase 2 trials of treatment of IBD with guselkumab are currently underway (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03466411). In patients with New York Heart Association class III and class IV congestive heart failure or multiple sclerosis, initiation of TNF-α inhibitors should be avoided. Among 3 phase 3 trials encompassing nearly 3000 patients treated with the IL-17 inhibitor brodalumab, a total of 3 patients died by suicide7,8; hence, the FDA has issued a black box warning cautioning against use of this drug in patients with history of suicidal ideation or recent suicidal behavior. Although a causal relationship between brodalumab and suicide has not been well established,9 a thorough psychiatric history should be obtained in those initiating treatment with brodalumab.

Initiation of Therapy

Prior to initiating biologic therapy, it is important to obtain a complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, tuberculosis testing, and hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus serologies. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus may be pursued at the clinician’s discretion. It is important to address any positive or concerning results prior to starting biologics. In patients with active infections, therapy may be initiated alongside guidance from an infectious disease specialist. Those with a positive purified protein derivative test, T-SPOT test, or QuantiFERON-TB Gold test must be referred for chest radiographs to rule out active tuberculosis. Patients with active HBV infection should receive appropriate referral to initiate antiviral therapy as well as core antibody testing, and those with active hepatitis C virus infection may only receive biologics under the combined discretion of a dermatologist and an appropriate specialist. Patients with human immunodeficiency virus must concurrently receive highly active antiretroviral therapy, show normal CD4+ T-cell count and undetectable viral load, and have no recent history of opportunistic infection.

Therapy should be commenced using specific dosing regimens, which are unique for each biologic (Table). Patients also must be educated on routine follow-up to assess treatment response and tolerability.

Assessment and Optimization of Treatment Response

Patients taking biologics may experience primary treatment failure, defined as lack of response to therapy from initiation. One predisposing factor may be increased body mass; patients who are overweight and obese are less likely to respond to standard regimens of TNF-α inhibitors and 45-mg dosing of ustekinumab. In most cases, however, the cause of primary nonresponse is unpredictable. For patients in whom therapy has failed within the recommended initial time frame (Table), dose escalation or shortening of dosing intervals may be pursued. Recommended dosing adjustments are outlined in the Table. Alternatively, patients may be switched to a different biologic.

If desired effectiveness is not reached with biologic monotherapy, topical corticosteroids, topical vitamin D analogues, or narrowband UVB light therapy may be concurrently used for difficult-to-treat areas. Evidence for safety and effectiveness of systemic adjuncts to biologics is moderate to low, warranting caution with their use. Methotrexate, cyclosporine, and apremilast have synergistic effects with biologics, though they may increase the risk for immunosuppression-related complications. Acitretin, an oral retinoid, likely is the most reasonable systemic adjunct to biologics because of its lack of immunosuppressive properties.

In patients with a suboptimal response to biologics, particularly those taking therapies that require frequent dosing, poor compliance should be considered.10 These patients may be switched to a biologic with less-frequent maintenance dosing (Table). Ustekinumab and tildrakizumab may be the best options for optimizing compliance, as they require dosing only once every 12 weeks after administration of loading doses.

Secondary treatment failure is diminished efficacy of treatment following successful initial response despite no changes in regimen. The best-known factor contributing to secondary nonresponse to biologics is the development of antidrug antibodies (ADAs), a phenomenon known as immunogenicity. The development of efficacy-limiting ADAs has been observed in response to most biologics, though ADAs against etanercept and guselkumab do not limit therapeutic response. Patients taking adalimumab and infliximab have particularly well-documented efficacy-limiting immunogenicity, and those who develop ADAs to infliximab are considered more prone to developing infusion reactions. Methotrexate, which limits antibody formation, may concomitantly be prescribed in patients who experience secondary treatment failure. It should be considered in all patients taking infliximab to increase efficacy and tolerability of therapy.

Considerations During Active Therapy

In addition to monitoring adherence and response to regimens, dermatologists must be heavily involved in counseling patients regarding the risks and adverse effects associated with these therapies. During maintenance therapy with biologics, patients must follow up with the prescriber at minimum every 3 to 6 months to evaluate for continued efficacy of treatment, extent of side effects, and effects of treatment on overall health and quality of life. Given the immunosuppressive effects of biologics, annual testing for tuberculosis should be considered in high-risk individuals. In those who are considered at low risk, tuberculosis testing may be done at the discretion of the dermatologist. In those with a history of HBV infection, HBV serologies should be pursued routinely given the risk for reactivation.

Annual screening for nonmelanoma skin cancer should be performed in all patients taking biologics. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy in particular confers an elevated risk for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, especially in patients who are immunosuppressed at baseline and those with history of UV phototherapy. Use of acitretin alongside TNF-α inhibitors or ustekinumab may prevent squamous cell carcinoma formation in high-risk patients.

Because infliximab treatment poses an elevated risk of liver injury,11 liver function tests should be repeated 3 months following initiation of treatment and then every 6 to 12 months subsequently if results are normal. Periodic assessment of suicidal ideation is recommended in patients on brodalumab therapy, which may necessitate more frequent follow-up visits and potentially psychiatry referrals in certain patients. Patients taking IL-17 inhibitors, particularly those who are concurrently taking methotrexate, are at increased risk for developing mucocutaneous Candida infections; these patients should be monitored for such infections and treated appropriately.12

It is additionally important for prescribing dermatologists to ensure that patients on biologics are following up with their general providers to receive timely age-appropriate preventative screenings and vaccines. Inactivated vaccinations may be administered during therapy with any biologic; however, live vaccinations may induce systemic infection in those who are immunocompromised, which theoretically includes individuals taking biologic agents, though incidence data in this patient population are scarce.13 Some experts believe that administration of live vaccines warrants temporary discontinuation of biologic therapy for 2 to 3 half-lives before and after vaccination (Table). Others recommend stopping treatment at least 4 weeks before and until 2 weeks after vaccination. For patients taking biologics with half-lives greater than 20 days, which would theoretically require stopping the drug 2 months prior to vaccination, the benefit of vaccination should be weighed against the risk of prolonged discontinuation of therapy. Until recently, this recommendation was particularly important, as a live herpes zoster vaccination was recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for adults older than 60 years. In 2017, a new inactivated herpes zoster vaccine was introduced and is now the preferred vaccine for all patients older than 50 years.14 It is especially important that patients on biologics receive this vaccine to avoid temporary drug discontinuation.

Evidence that any particular class of biologics increases risk for solid tumors or lymphoreticular malignancy is limited. One case-control analysis reported that more than 12 months of treatment with TNF-α inhibitors may increase risk for malignancy; however, the confidence interval reported hardly allows for statistical significance.15 Another retrospective cohort study found no elevated incidence of cancer in patients on TNF-α inhibitors compared to nonbiologic comparators.16 Ustekinumab was shown to confer no increased risk for malignancy in 1 large study,15 but no large studies have been conducted for other classes of drugs. Given the limited and inconclusive evidence available, the guidelines recommend that age-appropriate cancer screenings recommended for the general population should be pursued in patients taking biologics.

Surgery while taking biologics may lead to stress-induced augmentation of immunosuppression, resulting in elevated risk of infection.17 Low-risk surgeries that do not warrant discontinuation of treatment include endoscopic, ophthalmologic, dermatologic, orthopedic, and breast procedures. In patients preparing for elective surgery in which respiratory, gastrointestinal, or genitourinary tracts will be entered, biologics may be discontinued at least 3 half-lives (Table) prior to surgery if the dermatologist and surgeon collaboratively deem that risk of infection outweighs benefit of continued therapy.18 Therapy may be resumed within 1 to 2 weeks postoperatively if there are no surgical complications.

Switching Biologics

Changing therapy to another biologic should be considered if there is no response to treatment or the patient experiences adverse effects while taking a particular biologic. Because evidence is limited regarding the ideal time frame between discontinuation of a prior medication and initiation of a new biologic, this interval should be determined at the discretion of the provider based on the patient’s disease severity and response to prior treatment. For individuals who experience primary or secondary treatment failure while maintaining appropriate dosing and treatment compliance, switching to a different biologic is recommended to maximize treatment response.19 Changing therapy to a biologic within the same class is generally effective,20 and switching to a biologic with another mechanism of action should be considered if a class-specific adverse effect is the major reason for altering the regimen. Nonetheless, some patients may be unresponsive to biologic changes. Further research is necessary to determine which biologics may be most effective when previously used biologics have failed and particular factors that may predispose patients to biologic unresponsiveness.

Resuming Biologic Treatment Following Cessation

In cases where therapy is discontinued for any reason, it may be necessary to repeat initiation dosing when resuming treatment. In patients with severe or flaring disease or if more than 3 to 4 half-lives have passed since the most recent dose, it may be necessary to restart therapy with the loading dose (Table). Unfortunately, restarting therapy may preclude some patients from experiencing the maximal response that they attained prior to cessation. In such cases, switching biologic therapy to a different class may prove beneficial.

Final Thoughts

These recommendations contain valuable information that will assist dermatologists when initiating biologics and managing outcomes of their psoriasis patients. It is, however, crucial to bear in mind that these guidelines serve as merely a tool. Given the paucity of comprehensive research, particularly regarding some of the more recently approved therapies, there are many questions that are unanswered within the guidelines. Their utility for each individual patient situation is therefore limited, and clinical judgement may outweigh the information presented. The recommendations nevertheless provide a pivotal and unprecedented framework that promotes discourse among patients, dermatologists, and other providers to optimize the efficacy of biologic therapy for psoriasis.

- Michalek IM, Loring B, John SM. A systematic review of worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:205-212.

- Kurd SK, Gelfand JM. The prevalence of previously diagnosed and undiagnosed psoriasis in US adults: results from NHANES 2003-2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:218-224.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics [published online February 13, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826-850.

- Förger F, Villiger PM. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis during pregnancy: present and future. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12:937-944.

- Gooderham M, Elewski B, Pariser D, et al. Incidence of serious gastrointestinal events and inflammatory bowel disease among tildrakizumab-treated patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: data from 3 large randomized clinical trials [abstract]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(suppl 1):AB166.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318-328.

- Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:273-286

- Beck KM, Koo J. Brodalumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: up-to-date. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:287-292.

- Fouéré S, Adjadj L, Pawin H. How patients experience psoriasis: results from a European survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(suppl 3):2-6.

- Björnsson ES, Bergmann OM, Björnsson HK, et al. Incidence, presentation, and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1419-1425, 1425.e1-3; quiz e19-20.

- Saunte DM, Mrowietz U, Puig L, et al. Candida infections in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treated with interleukin-17 inhibitors and their practical management. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:47-62.

- Huber F, Ehrensperger B, Hatz C, et al. Safety of live vaccines on immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory therapy—a retrospective study in three Swiss Travel Clinics [published online January 1, 2018]. J Travel Med. doi:10.1093/jtm/tax082.

- Dooling KL, Guo A, Patel M, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for Use of Herpes Zoster Vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:103-108.

- Fiorentino D, Ho V, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of malignancy with systemic psoriasis treatment in the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment Registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:845-854.e5.

- Haynes K, Beukelman T, Curtis JR, et al. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy and cancer risk in chronic immune-mediated diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:48-58.

- Fabiano A, De Simone C, Gisondi P, et al. Management of patients with psoriasis treated with biologic drugs needing a surgical treatment. Drug Dev Res. 2014;75(suppl 1):S24-S26.

- Choi YM, Debbaneh M, Weinberg JM, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: perioperative management of systemic immunomodulatory agents in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:798-805.e7.

- Honda H, Umezawa Y, Kikuchi S, et al. Switching of biologics in psoriasis: reasons and results. J Dermatol. 2017;44:1015-1019.

- Bracke S, Lambert J. Viewpoint on handling anti-TNF failure in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2013;305:945-950.

Psoriasis is a systemic immune-mediated disorder characterized by erythematous, scaly, well-demarcated plaques on the skin that affects approximately 3% of the world’s population.1 The disease is moderate to severe for approximately 1 in 6 individuals with psoriasis.2 These patients, particularly those with symptoms that are refractory to topical therapy and/or phototherapy, can benefit from the use of biologic agents, which are monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins engineered to inhibit the action of cytokines that drive psoriatic inflammation.

In February 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released an updated set of guidelines for the use of biologics in treating adult patients with psoriasis.3 The prior guidelines were released in 2008 when just 3 biologics—etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab—were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of psoriasis. These older recommendations were mostly based on studies of the efficacy and safety of biologics for patients with psoriatic arthritis.4 Over the last 11 years, 8 novel biologics have gained FDA approval, and numerous large phase 2 and phase 3 trials evaluating the risks and benefits of biologics have been conducted. The new guidelines contain considerably more detail and are based on evidence more specific to psoriasis rather than to psoriatic arthritis. Given the large repertoire of biologics available today and the increased amount of published research regarding each one, these guidelines may aid dermatologists in choosing the optimal biologic and managing therapy.

The AAD-NPF recommendations discuss the mechanism of action, efficacy, safety, and adverse events of the 10 biologics that have been FDA approved for the treatment of psoriasis as of March 2019, plus risankizumab, which was pending FDA approval at the time of publication and was later approved in April 2019. They also address dosing regimens, potential to combine biologics with other therapies, and different forms of psoriasis for which each may be effective.3 The purpose of this discussion is to present these guidelines in a condensed form to prescribers of biologic therapies and review the most clinically significant considerations during each step of treatment. Of note, we highlight only treatment of adult patients and do not discuss information relevant to risankizumab, as it was not FDA approved when the AAD-NPF guidelines were released.

Choosing a Biologic

Biologic therapy may be considered for patients with psoriasis that affects more than 3% of the body’s surface and is recalcitrant to localized therapies. There is no particular first-line biologic recommended for all patients with psoriasis; rather, choice of therapy should be individualized to the patient, considering factors such as body parts affected, comorbidities, lifestyle, and drug cost.

All 10 FDA-approved biologics (Table) have been ranked by the AAD and NPF as having grade A evidence for efficacy as monotherapy in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque-type psoriasis. Involvement of difficult-to-treat areas may be considered when choosing a specific therapy. The tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors etanercept and adalimumab, the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab, and the IL-23 inhibitor guselkumab have the greatest evidence for efficacy in treatment of nail disease. For scalp involvement, etanercept and guselkumab have the highest-quality evidence, and for palmoplantar disease, adalimumab, secukinumab, and guselkumab are considered the most effective. The TNF-α inhibitors are considered the optimal treatment option for concurrent psoriatic arthritis, though the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab and the IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab also have shown grade A evidence of efficacy. Of note, because TNF-α inhibitors received the earliest FDA approval, there is most evidence available for this class. Therapies with lower evidence quality for certain forms of psoriasis may show real-world effectiveness in individual patients, though more trials will be necessary to generate a body of evidence to change these clinical recommendations.

In pregnant women or those are anticipating pregnancy, certolizumab may be considered, as it is the only biologic shown to have minimal to no placental transfer. Other TNF-α inhibitors may undergo active placental transfer, particularly during the latter half of pregnancy,5 and the greatest theoretical risk of transfer occurs in the third trimester. Although these drugs may not directly harm the fetus, they do cause fetal immunosuppression for up to the first 3 months of life. All TNF-α inhibitors are considered safe during lactation. There are inadequate data regarding the safety of other classes of biologics during pregnancy and lactation.

Overweight and obese patients also require unique considerations when choosing a biologic. Infliximab is the only approved psoriasis biologic that utilizes proportional-to-weight dosing and hence may be particularly efficacious in patients with higher body mass. Ustekinumab dosing also takes patient weight into consideration; patients heavier than 100 kg should receive 90-mg doses at initiation and during maintenance compared to 45 mg for patients who weigh 100 kg or less. Other approved biologics also may be utilized in these patients but may require closer monitoring of treatment efficacy.

There are few serious contraindications for specific biologic therapies. Any history of allergic reaction to a particular therapy is an absolute contraindication to its use. In patients for whom IL-17 inhibitor treatment is being considered, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should be ruled out given the likelihood that IL-17 could reactivate or worsen IBD. Of note, TNF-α inhibitors and ustekinumab are approved therapies for patients with IBD and may be recommended in patients with comorbid psoriasis. Phase 2 and phase 3 trials have found no reactivation or worsening of IBD in patients with psoriasis who were treated with the IL-23 inhibitor tildrakizumab,6 and phase 2 trials of treatment of IBD with guselkumab are currently underway (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03466411). In patients with New York Heart Association class III and class IV congestive heart failure or multiple sclerosis, initiation of TNF-α inhibitors should be avoided. Among 3 phase 3 trials encompassing nearly 3000 patients treated with the IL-17 inhibitor brodalumab, a total of 3 patients died by suicide7,8; hence, the FDA has issued a black box warning cautioning against use of this drug in patients with history of suicidal ideation or recent suicidal behavior. Although a causal relationship between brodalumab and suicide has not been well established,9 a thorough psychiatric history should be obtained in those initiating treatment with brodalumab.

Initiation of Therapy

Prior to initiating biologic therapy, it is important to obtain a complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, tuberculosis testing, and hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus serologies. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus may be pursued at the clinician’s discretion. It is important to address any positive or concerning results prior to starting biologics. In patients with active infections, therapy may be initiated alongside guidance from an infectious disease specialist. Those with a positive purified protein derivative test, T-SPOT test, or QuantiFERON-TB Gold test must be referred for chest radiographs to rule out active tuberculosis. Patients with active HBV infection should receive appropriate referral to initiate antiviral therapy as well as core antibody testing, and those with active hepatitis C virus infection may only receive biologics under the combined discretion of a dermatologist and an appropriate specialist. Patients with human immunodeficiency virus must concurrently receive highly active antiretroviral therapy, show normal CD4+ T-cell count and undetectable viral load, and have no recent history of opportunistic infection.

Therapy should be commenced using specific dosing regimens, which are unique for each biologic (Table). Patients also must be educated on routine follow-up to assess treatment response and tolerability.

Assessment and Optimization of Treatment Response

Patients taking biologics may experience primary treatment failure, defined as lack of response to therapy from initiation. One predisposing factor may be increased body mass; patients who are overweight and obese are less likely to respond to standard regimens of TNF-α inhibitors and 45-mg dosing of ustekinumab. In most cases, however, the cause of primary nonresponse is unpredictable. For patients in whom therapy has failed within the recommended initial time frame (Table), dose escalation or shortening of dosing intervals may be pursued. Recommended dosing adjustments are outlined in the Table. Alternatively, patients may be switched to a different biologic.

If desired effectiveness is not reached with biologic monotherapy, topical corticosteroids, topical vitamin D analogues, or narrowband UVB light therapy may be concurrently used for difficult-to-treat areas. Evidence for safety and effectiveness of systemic adjuncts to biologics is moderate to low, warranting caution with their use. Methotrexate, cyclosporine, and apremilast have synergistic effects with biologics, though they may increase the risk for immunosuppression-related complications. Acitretin, an oral retinoid, likely is the most reasonable systemic adjunct to biologics because of its lack of immunosuppressive properties.

In patients with a suboptimal response to biologics, particularly those taking therapies that require frequent dosing, poor compliance should be considered.10 These patients may be switched to a biologic with less-frequent maintenance dosing (Table). Ustekinumab and tildrakizumab may be the best options for optimizing compliance, as they require dosing only once every 12 weeks after administration of loading doses.

Secondary treatment failure is diminished efficacy of treatment following successful initial response despite no changes in regimen. The best-known factor contributing to secondary nonresponse to biologics is the development of antidrug antibodies (ADAs), a phenomenon known as immunogenicity. The development of efficacy-limiting ADAs has been observed in response to most biologics, though ADAs against etanercept and guselkumab do not limit therapeutic response. Patients taking adalimumab and infliximab have particularly well-documented efficacy-limiting immunogenicity, and those who develop ADAs to infliximab are considered more prone to developing infusion reactions. Methotrexate, which limits antibody formation, may concomitantly be prescribed in patients who experience secondary treatment failure. It should be considered in all patients taking infliximab to increase efficacy and tolerability of therapy.

Considerations During Active Therapy

In addition to monitoring adherence and response to regimens, dermatologists must be heavily involved in counseling patients regarding the risks and adverse effects associated with these therapies. During maintenance therapy with biologics, patients must follow up with the prescriber at minimum every 3 to 6 months to evaluate for continued efficacy of treatment, extent of side effects, and effects of treatment on overall health and quality of life. Given the immunosuppressive effects of biologics, annual testing for tuberculosis should be considered in high-risk individuals. In those who are considered at low risk, tuberculosis testing may be done at the discretion of the dermatologist. In those with a history of HBV infection, HBV serologies should be pursued routinely given the risk for reactivation.

Annual screening for nonmelanoma skin cancer should be performed in all patients taking biologics. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy in particular confers an elevated risk for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, especially in patients who are immunosuppressed at baseline and those with history of UV phototherapy. Use of acitretin alongside TNF-α inhibitors or ustekinumab may prevent squamous cell carcinoma formation in high-risk patients.

Because infliximab treatment poses an elevated risk of liver injury,11 liver function tests should be repeated 3 months following initiation of treatment and then every 6 to 12 months subsequently if results are normal. Periodic assessment of suicidal ideation is recommended in patients on brodalumab therapy, which may necessitate more frequent follow-up visits and potentially psychiatry referrals in certain patients. Patients taking IL-17 inhibitors, particularly those who are concurrently taking methotrexate, are at increased risk for developing mucocutaneous Candida infections; these patients should be monitored for such infections and treated appropriately.12

It is additionally important for prescribing dermatologists to ensure that patients on biologics are following up with their general providers to receive timely age-appropriate preventative screenings and vaccines. Inactivated vaccinations may be administered during therapy with any biologic; however, live vaccinations may induce systemic infection in those who are immunocompromised, which theoretically includes individuals taking biologic agents, though incidence data in this patient population are scarce.13 Some experts believe that administration of live vaccines warrants temporary discontinuation of biologic therapy for 2 to 3 half-lives before and after vaccination (Table). Others recommend stopping treatment at least 4 weeks before and until 2 weeks after vaccination. For patients taking biologics with half-lives greater than 20 days, which would theoretically require stopping the drug 2 months prior to vaccination, the benefit of vaccination should be weighed against the risk of prolonged discontinuation of therapy. Until recently, this recommendation was particularly important, as a live herpes zoster vaccination was recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for adults older than 60 years. In 2017, a new inactivated herpes zoster vaccine was introduced and is now the preferred vaccine for all patients older than 50 years.14 It is especially important that patients on biologics receive this vaccine to avoid temporary drug discontinuation.

Evidence that any particular class of biologics increases risk for solid tumors or lymphoreticular malignancy is limited. One case-control analysis reported that more than 12 months of treatment with TNF-α inhibitors may increase risk for malignancy; however, the confidence interval reported hardly allows for statistical significance.15 Another retrospective cohort study found no elevated incidence of cancer in patients on TNF-α inhibitors compared to nonbiologic comparators.16 Ustekinumab was shown to confer no increased risk for malignancy in 1 large study,15 but no large studies have been conducted for other classes of drugs. Given the limited and inconclusive evidence available, the guidelines recommend that age-appropriate cancer screenings recommended for the general population should be pursued in patients taking biologics.

Surgery while taking biologics may lead to stress-induced augmentation of immunosuppression, resulting in elevated risk of infection.17 Low-risk surgeries that do not warrant discontinuation of treatment include endoscopic, ophthalmologic, dermatologic, orthopedic, and breast procedures. In patients preparing for elective surgery in which respiratory, gastrointestinal, or genitourinary tracts will be entered, biologics may be discontinued at least 3 half-lives (Table) prior to surgery if the dermatologist and surgeon collaboratively deem that risk of infection outweighs benefit of continued therapy.18 Therapy may be resumed within 1 to 2 weeks postoperatively if there are no surgical complications.

Switching Biologics

Changing therapy to another biologic should be considered if there is no response to treatment or the patient experiences adverse effects while taking a particular biologic. Because evidence is limited regarding the ideal time frame between discontinuation of a prior medication and initiation of a new biologic, this interval should be determined at the discretion of the provider based on the patient’s disease severity and response to prior treatment. For individuals who experience primary or secondary treatment failure while maintaining appropriate dosing and treatment compliance, switching to a different biologic is recommended to maximize treatment response.19 Changing therapy to a biologic within the same class is generally effective,20 and switching to a biologic with another mechanism of action should be considered if a class-specific adverse effect is the major reason for altering the regimen. Nonetheless, some patients may be unresponsive to biologic changes. Further research is necessary to determine which biologics may be most effective when previously used biologics have failed and particular factors that may predispose patients to biologic unresponsiveness.

Resuming Biologic Treatment Following Cessation

In cases where therapy is discontinued for any reason, it may be necessary to repeat initiation dosing when resuming treatment. In patients with severe or flaring disease or if more than 3 to 4 half-lives have passed since the most recent dose, it may be necessary to restart therapy with the loading dose (Table). Unfortunately, restarting therapy may preclude some patients from experiencing the maximal response that they attained prior to cessation. In such cases, switching biologic therapy to a different class may prove beneficial.

Final Thoughts

These recommendations contain valuable information that will assist dermatologists when initiating biologics and managing outcomes of their psoriasis patients. It is, however, crucial to bear in mind that these guidelines serve as merely a tool. Given the paucity of comprehensive research, particularly regarding some of the more recently approved therapies, there are many questions that are unanswered within the guidelines. Their utility for each individual patient situation is therefore limited, and clinical judgement may outweigh the information presented. The recommendations nevertheless provide a pivotal and unprecedented framework that promotes discourse among patients, dermatologists, and other providers to optimize the efficacy of biologic therapy for psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a systemic immune-mediated disorder characterized by erythematous, scaly, well-demarcated plaques on the skin that affects approximately 3% of the world’s population.1 The disease is moderate to severe for approximately 1 in 6 individuals with psoriasis.2 These patients, particularly those with symptoms that are refractory to topical therapy and/or phototherapy, can benefit from the use of biologic agents, which are monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins engineered to inhibit the action of cytokines that drive psoriatic inflammation.

In February 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released an updated set of guidelines for the use of biologics in treating adult patients with psoriasis.3 The prior guidelines were released in 2008 when just 3 biologics—etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab—were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of psoriasis. These older recommendations were mostly based on studies of the efficacy and safety of biologics for patients with psoriatic arthritis.4 Over the last 11 years, 8 novel biologics have gained FDA approval, and numerous large phase 2 and phase 3 trials evaluating the risks and benefits of biologics have been conducted. The new guidelines contain considerably more detail and are based on evidence more specific to psoriasis rather than to psoriatic arthritis. Given the large repertoire of biologics available today and the increased amount of published research regarding each one, these guidelines may aid dermatologists in choosing the optimal biologic and managing therapy.

The AAD-NPF recommendations discuss the mechanism of action, efficacy, safety, and adverse events of the 10 biologics that have been FDA approved for the treatment of psoriasis as of March 2019, plus risankizumab, which was pending FDA approval at the time of publication and was later approved in April 2019. They also address dosing regimens, potential to combine biologics with other therapies, and different forms of psoriasis for which each may be effective.3 The purpose of this discussion is to present these guidelines in a condensed form to prescribers of biologic therapies and review the most clinically significant considerations during each step of treatment. Of note, we highlight only treatment of adult patients and do not discuss information relevant to risankizumab, as it was not FDA approved when the AAD-NPF guidelines were released.

Choosing a Biologic

Biologic therapy may be considered for patients with psoriasis that affects more than 3% of the body’s surface and is recalcitrant to localized therapies. There is no particular first-line biologic recommended for all patients with psoriasis; rather, choice of therapy should be individualized to the patient, considering factors such as body parts affected, comorbidities, lifestyle, and drug cost.

All 10 FDA-approved biologics (Table) have been ranked by the AAD and NPF as having grade A evidence for efficacy as monotherapy in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque-type psoriasis. Involvement of difficult-to-treat areas may be considered when choosing a specific therapy. The tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors etanercept and adalimumab, the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab, and the IL-23 inhibitor guselkumab have the greatest evidence for efficacy in treatment of nail disease. For scalp involvement, etanercept and guselkumab have the highest-quality evidence, and for palmoplantar disease, adalimumab, secukinumab, and guselkumab are considered the most effective. The TNF-α inhibitors are considered the optimal treatment option for concurrent psoriatic arthritis, though the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab and the IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab also have shown grade A evidence of efficacy. Of note, because TNF-α inhibitors received the earliest FDA approval, there is most evidence available for this class. Therapies with lower evidence quality for certain forms of psoriasis may show real-world effectiveness in individual patients, though more trials will be necessary to generate a body of evidence to change these clinical recommendations.

In pregnant women or those are anticipating pregnancy, certolizumab may be considered, as it is the only biologic shown to have minimal to no placental transfer. Other TNF-α inhibitors may undergo active placental transfer, particularly during the latter half of pregnancy,5 and the greatest theoretical risk of transfer occurs in the third trimester. Although these drugs may not directly harm the fetus, they do cause fetal immunosuppression for up to the first 3 months of life. All TNF-α inhibitors are considered safe during lactation. There are inadequate data regarding the safety of other classes of biologics during pregnancy and lactation.

Overweight and obese patients also require unique considerations when choosing a biologic. Infliximab is the only approved psoriasis biologic that utilizes proportional-to-weight dosing and hence may be particularly efficacious in patients with higher body mass. Ustekinumab dosing also takes patient weight into consideration; patients heavier than 100 kg should receive 90-mg doses at initiation and during maintenance compared to 45 mg for patients who weigh 100 kg or less. Other approved biologics also may be utilized in these patients but may require closer monitoring of treatment efficacy.

There are few serious contraindications for specific biologic therapies. Any history of allergic reaction to a particular therapy is an absolute contraindication to its use. In patients for whom IL-17 inhibitor treatment is being considered, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should be ruled out given the likelihood that IL-17 could reactivate or worsen IBD. Of note, TNF-α inhibitors and ustekinumab are approved therapies for patients with IBD and may be recommended in patients with comorbid psoriasis. Phase 2 and phase 3 trials have found no reactivation or worsening of IBD in patients with psoriasis who were treated with the IL-23 inhibitor tildrakizumab,6 and phase 2 trials of treatment of IBD with guselkumab are currently underway (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03466411). In patients with New York Heart Association class III and class IV congestive heart failure or multiple sclerosis, initiation of TNF-α inhibitors should be avoided. Among 3 phase 3 trials encompassing nearly 3000 patients treated with the IL-17 inhibitor brodalumab, a total of 3 patients died by suicide7,8; hence, the FDA has issued a black box warning cautioning against use of this drug in patients with history of suicidal ideation or recent suicidal behavior. Although a causal relationship between brodalumab and suicide has not been well established,9 a thorough psychiatric history should be obtained in those initiating treatment with brodalumab.

Initiation of Therapy

Prior to initiating biologic therapy, it is important to obtain a complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, tuberculosis testing, and hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus serologies. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus may be pursued at the clinician’s discretion. It is important to address any positive or concerning results prior to starting biologics. In patients with active infections, therapy may be initiated alongside guidance from an infectious disease specialist. Those with a positive purified protein derivative test, T-SPOT test, or QuantiFERON-TB Gold test must be referred for chest radiographs to rule out active tuberculosis. Patients with active HBV infection should receive appropriate referral to initiate antiviral therapy as well as core antibody testing, and those with active hepatitis C virus infection may only receive biologics under the combined discretion of a dermatologist and an appropriate specialist. Patients with human immunodeficiency virus must concurrently receive highly active antiretroviral therapy, show normal CD4+ T-cell count and undetectable viral load, and have no recent history of opportunistic infection.

Therapy should be commenced using specific dosing regimens, which are unique for each biologic (Table). Patients also must be educated on routine follow-up to assess treatment response and tolerability.

Assessment and Optimization of Treatment Response

Patients taking biologics may experience primary treatment failure, defined as lack of response to therapy from initiation. One predisposing factor may be increased body mass; patients who are overweight and obese are less likely to respond to standard regimens of TNF-α inhibitors and 45-mg dosing of ustekinumab. In most cases, however, the cause of primary nonresponse is unpredictable. For patients in whom therapy has failed within the recommended initial time frame (Table), dose escalation or shortening of dosing intervals may be pursued. Recommended dosing adjustments are outlined in the Table. Alternatively, patients may be switched to a different biologic.

If desired effectiveness is not reached with biologic monotherapy, topical corticosteroids, topical vitamin D analogues, or narrowband UVB light therapy may be concurrently used for difficult-to-treat areas. Evidence for safety and effectiveness of systemic adjuncts to biologics is moderate to low, warranting caution with their use. Methotrexate, cyclosporine, and apremilast have synergistic effects with biologics, though they may increase the risk for immunosuppression-related complications. Acitretin, an oral retinoid, likely is the most reasonable systemic adjunct to biologics because of its lack of immunosuppressive properties.

In patients with a suboptimal response to biologics, particularly those taking therapies that require frequent dosing, poor compliance should be considered.10 These patients may be switched to a biologic with less-frequent maintenance dosing (Table). Ustekinumab and tildrakizumab may be the best options for optimizing compliance, as they require dosing only once every 12 weeks after administration of loading doses.

Secondary treatment failure is diminished efficacy of treatment following successful initial response despite no changes in regimen. The best-known factor contributing to secondary nonresponse to biologics is the development of antidrug antibodies (ADAs), a phenomenon known as immunogenicity. The development of efficacy-limiting ADAs has been observed in response to most biologics, though ADAs against etanercept and guselkumab do not limit therapeutic response. Patients taking adalimumab and infliximab have particularly well-documented efficacy-limiting immunogenicity, and those who develop ADAs to infliximab are considered more prone to developing infusion reactions. Methotrexate, which limits antibody formation, may concomitantly be prescribed in patients who experience secondary treatment failure. It should be considered in all patients taking infliximab to increase efficacy and tolerability of therapy.

Considerations During Active Therapy

In addition to monitoring adherence and response to regimens, dermatologists must be heavily involved in counseling patients regarding the risks and adverse effects associated with these therapies. During maintenance therapy with biologics, patients must follow up with the prescriber at minimum every 3 to 6 months to evaluate for continued efficacy of treatment, extent of side effects, and effects of treatment on overall health and quality of life. Given the immunosuppressive effects of biologics, annual testing for tuberculosis should be considered in high-risk individuals. In those who are considered at low risk, tuberculosis testing may be done at the discretion of the dermatologist. In those with a history of HBV infection, HBV serologies should be pursued routinely given the risk for reactivation.

Annual screening for nonmelanoma skin cancer should be performed in all patients taking biologics. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy in particular confers an elevated risk for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, especially in patients who are immunosuppressed at baseline and those with history of UV phototherapy. Use of acitretin alongside TNF-α inhibitors or ustekinumab may prevent squamous cell carcinoma formation in high-risk patients.

Because infliximab treatment poses an elevated risk of liver injury,11 liver function tests should be repeated 3 months following initiation of treatment and then every 6 to 12 months subsequently if results are normal. Periodic assessment of suicidal ideation is recommended in patients on brodalumab therapy, which may necessitate more frequent follow-up visits and potentially psychiatry referrals in certain patients. Patients taking IL-17 inhibitors, particularly those who are concurrently taking methotrexate, are at increased risk for developing mucocutaneous Candida infections; these patients should be monitored for such infections and treated appropriately.12

It is additionally important for prescribing dermatologists to ensure that patients on biologics are following up with their general providers to receive timely age-appropriate preventative screenings and vaccines. Inactivated vaccinations may be administered during therapy with any biologic; however, live vaccinations may induce systemic infection in those who are immunocompromised, which theoretically includes individuals taking biologic agents, though incidence data in this patient population are scarce.13 Some experts believe that administration of live vaccines warrants temporary discontinuation of biologic therapy for 2 to 3 half-lives before and after vaccination (Table). Others recommend stopping treatment at least 4 weeks before and until 2 weeks after vaccination. For patients taking biologics with half-lives greater than 20 days, which would theoretically require stopping the drug 2 months prior to vaccination, the benefit of vaccination should be weighed against the risk of prolonged discontinuation of therapy. Until recently, this recommendation was particularly important, as a live herpes zoster vaccination was recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for adults older than 60 years. In 2017, a new inactivated herpes zoster vaccine was introduced and is now the preferred vaccine for all patients older than 50 years.14 It is especially important that patients on biologics receive this vaccine to avoid temporary drug discontinuation.

Evidence that any particular class of biologics increases risk for solid tumors or lymphoreticular malignancy is limited. One case-control analysis reported that more than 12 months of treatment with TNF-α inhibitors may increase risk for malignancy; however, the confidence interval reported hardly allows for statistical significance.15 Another retrospective cohort study found no elevated incidence of cancer in patients on TNF-α inhibitors compared to nonbiologic comparators.16 Ustekinumab was shown to confer no increased risk for malignancy in 1 large study,15 but no large studies have been conducted for other classes of drugs. Given the limited and inconclusive evidence available, the guidelines recommend that age-appropriate cancer screenings recommended for the general population should be pursued in patients taking biologics.

Surgery while taking biologics may lead to stress-induced augmentation of immunosuppression, resulting in elevated risk of infection.17 Low-risk surgeries that do not warrant discontinuation of treatment include endoscopic, ophthalmologic, dermatologic, orthopedic, and breast procedures. In patients preparing for elective surgery in which respiratory, gastrointestinal, or genitourinary tracts will be entered, biologics may be discontinued at least 3 half-lives (Table) prior to surgery if the dermatologist and surgeon collaboratively deem that risk of infection outweighs benefit of continued therapy.18 Therapy may be resumed within 1 to 2 weeks postoperatively if there are no surgical complications.

Switching Biologics

Changing therapy to another biologic should be considered if there is no response to treatment or the patient experiences adverse effects while taking a particular biologic. Because evidence is limited regarding the ideal time frame between discontinuation of a prior medication and initiation of a new biologic, this interval should be determined at the discretion of the provider based on the patient’s disease severity and response to prior treatment. For individuals who experience primary or secondary treatment failure while maintaining appropriate dosing and treatment compliance, switching to a different biologic is recommended to maximize treatment response.19 Changing therapy to a biologic within the same class is generally effective,20 and switching to a biologic with another mechanism of action should be considered if a class-specific adverse effect is the major reason for altering the regimen. Nonetheless, some patients may be unresponsive to biologic changes. Further research is necessary to determine which biologics may be most effective when previously used biologics have failed and particular factors that may predispose patients to biologic unresponsiveness.

Resuming Biologic Treatment Following Cessation

In cases where therapy is discontinued for any reason, it may be necessary to repeat initiation dosing when resuming treatment. In patients with severe or flaring disease or if more than 3 to 4 half-lives have passed since the most recent dose, it may be necessary to restart therapy with the loading dose (Table). Unfortunately, restarting therapy may preclude some patients from experiencing the maximal response that they attained prior to cessation. In such cases, switching biologic therapy to a different class may prove beneficial.

Final Thoughts

These recommendations contain valuable information that will assist dermatologists when initiating biologics and managing outcomes of their psoriasis patients. It is, however, crucial to bear in mind that these guidelines serve as merely a tool. Given the paucity of comprehensive research, particularly regarding some of the more recently approved therapies, there are many questions that are unanswered within the guidelines. Their utility for each individual patient situation is therefore limited, and clinical judgement may outweigh the information presented. The recommendations nevertheless provide a pivotal and unprecedented framework that promotes discourse among patients, dermatologists, and other providers to optimize the efficacy of biologic therapy for psoriasis.

- Michalek IM, Loring B, John SM. A systematic review of worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:205-212.

- Kurd SK, Gelfand JM. The prevalence of previously diagnosed and undiagnosed psoriasis in US adults: results from NHANES 2003-2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:218-224.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics [published online February 13, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826-850.

- Förger F, Villiger PM. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis during pregnancy: present and future. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12:937-944.

- Gooderham M, Elewski B, Pariser D, et al. Incidence of serious gastrointestinal events and inflammatory bowel disease among tildrakizumab-treated patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: data from 3 large randomized clinical trials [abstract]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(suppl 1):AB166.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318-328.

- Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:273-286

- Beck KM, Koo J. Brodalumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: up-to-date. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:287-292.

- Fouéré S, Adjadj L, Pawin H. How patients experience psoriasis: results from a European survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(suppl 3):2-6.

- Björnsson ES, Bergmann OM, Björnsson HK, et al. Incidence, presentation, and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1419-1425, 1425.e1-3; quiz e19-20.

- Saunte DM, Mrowietz U, Puig L, et al. Candida infections in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treated with interleukin-17 inhibitors and their practical management. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:47-62.

- Huber F, Ehrensperger B, Hatz C, et al. Safety of live vaccines on immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory therapy—a retrospective study in three Swiss Travel Clinics [published online January 1, 2018]. J Travel Med. doi:10.1093/jtm/tax082.

- Dooling KL, Guo A, Patel M, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for Use of Herpes Zoster Vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:103-108.

- Fiorentino D, Ho V, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of malignancy with systemic psoriasis treatment in the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment Registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:845-854.e5.

- Haynes K, Beukelman T, Curtis JR, et al. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy and cancer risk in chronic immune-mediated diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:48-58.

- Fabiano A, De Simone C, Gisondi P, et al. Management of patients with psoriasis treated with biologic drugs needing a surgical treatment. Drug Dev Res. 2014;75(suppl 1):S24-S26.

- Choi YM, Debbaneh M, Weinberg JM, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: perioperative management of systemic immunomodulatory agents in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:798-805.e7.

- Honda H, Umezawa Y, Kikuchi S, et al. Switching of biologics in psoriasis: reasons and results. J Dermatol. 2017;44:1015-1019.

- Bracke S, Lambert J. Viewpoint on handling anti-TNF failure in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2013;305:945-950.

- Michalek IM, Loring B, John SM. A systematic review of worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:205-212.

- Kurd SK, Gelfand JM. The prevalence of previously diagnosed and undiagnosed psoriasis in US adults: results from NHANES 2003-2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:218-224.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics [published online February 13, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826-850.

- Förger F, Villiger PM. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis during pregnancy: present and future. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12:937-944.

- Gooderham M, Elewski B, Pariser D, et al. Incidence of serious gastrointestinal events and inflammatory bowel disease among tildrakizumab-treated patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: data from 3 large randomized clinical trials [abstract]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(suppl 1):AB166.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318-328.

- Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:273-286

- Beck KM, Koo J. Brodalumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: up-to-date. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:287-292.

- Fouéré S, Adjadj L, Pawin H. How patients experience psoriasis: results from a European survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(suppl 3):2-6.

- Björnsson ES, Bergmann OM, Björnsson HK, et al. Incidence, presentation, and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1419-1425, 1425.e1-3; quiz e19-20.

- Saunte DM, Mrowietz U, Puig L, et al. Candida infections in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treated with interleukin-17 inhibitors and their practical management. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:47-62.

- Huber F, Ehrensperger B, Hatz C, et al. Safety of live vaccines on immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory therapy—a retrospective study in three Swiss Travel Clinics [published online January 1, 2018]. J Travel Med. doi:10.1093/jtm/tax082.

- Dooling KL, Guo A, Patel M, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for Use of Herpes Zoster Vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:103-108.

- Fiorentino D, Ho V, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of malignancy with systemic psoriasis treatment in the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment Registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:845-854.e5.

- Haynes K, Beukelman T, Curtis JR, et al. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy and cancer risk in chronic immune-mediated diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:48-58.

- Fabiano A, De Simone C, Gisondi P, et al. Management of patients with psoriasis treated with biologic drugs needing a surgical treatment. Drug Dev Res. 2014;75(suppl 1):S24-S26.

- Choi YM, Debbaneh M, Weinberg JM, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: perioperative management of systemic immunomodulatory agents in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:798-805.e7.

- Honda H, Umezawa Y, Kikuchi S, et al. Switching of biologics in psoriasis: reasons and results. J Dermatol. 2017;44:1015-1019.

- Bracke S, Lambert J. Viewpoint on handling anti-TNF failure in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2013;305:945-950.

Practice Points

- There are currently 11 biologics approved for psoriasis, but there is no first-line or optimalbiologic. The choice must be made using clinical judgment based on a variety of medical and social factors.

- Frequent assessment for efficacy of and adverse events due to biologic therapy is warranted, as lack of response, loss of response, or severe side effects may warrant addition of concurrent therapies or switching to a different biologic.

- There are important considerations to make when immunizing and planning for surgery in patients on biologics.

Systemic Therapies in Psoriasis: An Update on Newly Approved and Pipeline Biologics and Oral Treatments

Recent advances in our understanding of psoriatic immune pathways have led to new generations of targeted therapies developed over the last 5 years. Although the pathogenesis of psoriasis remains to be fully elucidated, the success of these targeted therapies has confirmed a critical role of the IL-23/helper T cell (TH17) axis in maintaining the psoriatic immune cascade, a positive feedback loop in which IL-17, IL-12, and IL-23 released from myeloid dendritic cells lead to activation of helperT cells. Activated helper T cells—namely TH1, TH17, and TH22—release IL-17, IL-22, and other proinflammatory cytokines, amplifying the immune response and leading to keratinocyte proliferation and immune cell migration to psoriatic lesions. Inhibition of IL-17 and IL-23 by several biologics disrupts this aberrant inflammatory cascade and has led to dramatic improvements in outcomes, particularly among patients with moderate to severe disease.

Numerous biologics targeting these pathways and several oral treatments have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of psoriasis; in addition, a number of promising therapies are on the horizon, and knowledge of these medications might help guide our treatment approach to the patient with psoriasis. This article provides an update on the most recent (as of 2019) approved therapies and medications in the pipeline for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with a focus on systemic agents in phase 3 clinical trials. (Medications targeting psoriatic arthritis, biosimilars, and existing medications approved by the FDA prior to 2019 will not be discussed.)

Risankizumab

Risankizumab-rzaa (formerly BI 655066) is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that targets the p19 subunit of IL-23, selectively inhibiting the role of this critical cytokine in psoriatic inflammation.

Phase 1 Trial

In a phase 1 proof-of-concept study, 39 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis received varying dosages of intravenous or subcutaneous risankizumab or placebo.1 At week 12, the percentage of risankizumab-treated patients achieving reduction in the psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score by 75% (PASI 75), 90% (PASI 90), and 100% (PASI 100) was 87% (27/31; P<.001 vs placebo), 58% (18/31; P=.007 vs placebo), and 16% (5/31; P=.590 vs placebo), respectively. Improvements in PASI scores were observed as early as week 2. Adverse events (AEs) were reported by 65% of the risankizumab group and 88% of the placebo group. Serious AEs were reported in 4 patients receiving risankizumab, none of which were considered related to the study medication.1

Phase 2 Trial

A phase 2 comparator trial demonstrated noninferiority at higher dosages of risankizumab in comparison to the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab.2 Among 166 participants with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, PASI 90 at week 12 was met by 77% of participants receiving 90 or 180 mg of risankizumab compared to 40% receiving ustekinumab (P<.001). Onset of activity with risankizumab was faster and the duration of effect longer vs ustekinumab; by week 8, at least PASI 75 was achieved by approximately 80% of participants in the 90-mg and 180-mg risankizumab groups compared to 60% in the ustekinumab group; PASI score reductions generally were maintained for as long as 20 weeks after the final dose of risankizumab was administered.2

Phase 3 Trials

The 52-week UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2 phase 3 trials compared subcutaneous risankizumab (150 mg) to ustekinumab (45 or 90 mg [weight-based dosing]) or placebo administered at weeks 0, 4, 16, 28, and 40 in approximately 1000 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.3 Patients initially assigned to placebo switched to risankizumab 150 mg at week 16. At week 16, PASI 90 was achieved by 75.3% of risankizumab-treated patients, 42.0% of ustekinumab-treated patients, and 4.9% of placebo-treated patients in UltIMMa-1, and by 74.8% of risankizumab-treated patients, 47.5% of ustekinumab-treated patients, and 2.0% of placebo-treated patients in UltIMMa-2 (P<.0001 vs placebo and ustekinumab for both studies). Achievement of a static physician’s global assessment (sPGA) score of 0 or 1 at week 16 similarly favored risankizumab, with 87.8%, 63.0%, and 7.8% of patients in UltIMMa-1 meeting an sPGA score of 0 or 1 in the risankizumab, ustekinumab, and placebo groups, respectively, and 83.7%, 61.6%, and 5.1% in UltIMMa-2 meeting an sPGA score of 0 or 1 in the risankizumab, ustekinumab, and placebo groups, respectively (P<.0001 vs placebo and ustekinumab for both studies). Among patients initially assigned to risankizumab, improvements in PASI and sPGA continued to increase until week 52, with 81.9% achieving PASI 90 at week 52 compared to 44.0% on ustekinumab in UltIMMa-1, and 80.6% achieving PASI 90 at week 52 compared to 50.5% on ustekinumab in UltIMMa-2 (P<.0001 vs ustekinumab for both studies). Treatment-emergent AE profiles were similar for risankizumab and ustekinumab in both studies, and there were no unexpected safety findings.3

Risankizumab received FDA approval for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in April 2019.

Bimekizumab

Bimekizumab (UCB4940), a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody, selectively neutralizes the biologic functions of IL-17A and IL-17F, the latter of which has only recently been implicated in contributing to the psoriatic immune cascade.4

First-in-Human Study

Thirty-nine participants with mild psoriasis demonstrated efficacy after single-dose intravenous bimekizumab, with maximal improvements in all measures of disease activity observed between weeks 8 and 12 in participants receiving 160 to 640 mg.5

Proof-of-Concept Phase 1b Study

A subsequent trial of 53 participants with psoriatic arthritis demonstrated sustained efficacy to week 20 with varying dosages of intravenous bimekizumab.6 At week 8, PASI 100 was met by 86.7% of participants receiving the top 3 dosages of bimekizumab compared to none of the placebo-treated participants. Treatment-emergent AEs, including neutropenia and elevation of liver transaminases, were mostly mild to moderate and resolved spontaneously. There were 3 severe AEs and 3 serious AEs, none of which were related to treatment.6

Importantly, bimekizumab was shown in this small study to have the potential to be highly effective at treating psoriatic arthritis. American College of Rheumatology ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 response criteria were very high, with an ACR20 of 80% and an ACR50 of 40%.6 Further trials are necessary to gather more data and confirm these findings; however, these levels of response are higher than those of any other biologic on the market.

Phase 2b Dose-Ranging Study

In this trial, 250 participants with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis received either 64 mg, 160 mg with a 320-mg loading dose, 320 mg, or 480 mg of subcutaneous bimekizumab or placebo at weeks 0, 4, and 8.7 At week 12, PASI 90 was achieved by significantly more patients in all bimekizumab-treated groups compared to the placebo group (46.2%–79.1% vs 0%; P<.0001 for all dosages); PASI 100 also was achieved by significantly more bimekizumab-treated patients (27.9%–60.0% vs 0%; P<.0002). Improvement began as early as week 4, with clinically meaningful responses observed in all bimekizumab groups across all measures of disease activity. Treatment-emergent AEs occurred more frequently in bimekizumab-treated participants (61%) than in placebo-treated participants (36%); the most common AEs were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection. Of note, fungal infections were reported by 4.3% of participants receiving bimekizumab; all cases were localized superficial infection, and none led to discontinuation. Three serious AEs were reported, none of which were considered related to the study treatment.7

Mirikizumab

Mirikizumab (LY3074828) is a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody that selectively binds and inhibits the p19 subunit of IL-23, with no action on IL-12.

Phase 1 Trial

Mirikizumab was shown to improve PASI scores in patients with plaque psoriasis.8

Phase 2 Trial

Subsequently, a trial of 205 participants with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis compared 3 dosing regimens of subcutaneous mirikizumab—30, 100, or 300 mg—at weeks 0 and 8 compared to placebo.9 Primary end point results at week 16 demonstrated PASI 90 response rates of 0%, 29% (P=.009), 59% (P<.001), and 67% (P<.001) in the placebo, 30-mg, 100-mg, and 300-mg mirikizumab groups, respectively. Complete clearance of psoriasis, measured by PASI 100 and sPGA 0, was achieved by 0%, 16%, 31%, and 31%, respectively (P=.039 for 30 mg vs placebo; P=.007 for the higher dosage groups vs placebo). Response rates for all efficacy outcomes were statistically significantly higher for all mirikizumab treatment groups compared to placebo and were highest in the 100-mg and 300-mg treatment groups. Frequencies of participants reporting AEs were similar across treatment and placebo groups.9

Oral Medications

Only a few small-molecule, orally bioavailable therapies are on the market for the treatment of psoriasis, some of which are associated with unfavorable side-effect profiles that preclude long-term therapy.

BMS-986165

The intracellular signaling enzyme tyrosine kinase 2 is involved in functional responses of IL-12 and IL-23. BMS-986165, a potent oral inhibitor of tyrosine kinase 2 with greater selectivity than other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, demonstrated efficacy in a phase 2 trial of 267 participants with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis receiving any of 5 dosing regimens—3 mg every other day, 3 mg daily, 3 mg twice daily, 6 mg twice daily, and 12 mg daily—compared to placebo.10 At week 12, the percentage of patients with a 75% or greater reduction in PASI was 7% with placebo, 9% with 3 mg every other day (P=.49 vs placebo), 39% with 3 mg daily (P<.001 vs placebo), 69% with 3 mg twice daily (P<.001 vs placebo), 67% with 6 mg twice daily (P<.001 vs placebo), and 75% with 12 mg once daily (P<.001 vs placebo). Adverse events occurred in 51% of patients in the placebo group and in 55% to 80% of BMS-986165–treated patients; the most common AEs were nasopharyngitis, headache, diarrhea, nausea, and upper respiratory tract infection.10

A phase 3 trial comparing BMS-986165 with placebo and apremilast is underway (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03611751).

Piclidenoson (CF101)

A novel small molecule that binds the Gi protein–associated A3 adenosine receptor piclidenoson induces an anti-inflammatory response via deregulation of the Wnt and nuclear factor κB signal transduction pathways, leading to downregulation of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-17 and IL-23.11