User login

Ulcers on lower leg

The FP recognized this as classic pyoderma gangrenosum (PG)—a challenging condition to treat and not within the typical scope of practice for an FP. Nonhealing, well-defined leg ulcers in a person with Crohn's disease (or any type of inflammatory bowel disease) are often seen with PG. Pathergy—the development of an exaggerated injury following minor trauma—is known to occur with PG.

The FP also noted the violet-blue coloration around the borders of the ulcers, which is referred to as a “gun-metal border.” He considered doing a biopsy on the edge of the ulcer to rule out other conditions and to see if there was a neutrophilic infiltrate that is typically seen with PG. However, the FP realized that pathergy could be stimulated by a biopsy, so he decided to refer the patient to Dermatology.

Knowing that the patient might have to wait a few months to see a dermatologist, the FP consulted online sources and prescribed topical clobetasol ointment to be applied twice daily as an initial therapy. This was not successful, so after a phone consult with the dermatologist, the FP added oral prednisone 40 mg/d for the next 2 weeks until the dermatologist could see the patient.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1147-1152.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized this as classic pyoderma gangrenosum (PG)—a challenging condition to treat and not within the typical scope of practice for an FP. Nonhealing, well-defined leg ulcers in a person with Crohn's disease (or any type of inflammatory bowel disease) are often seen with PG. Pathergy—the development of an exaggerated injury following minor trauma—is known to occur with PG.

The FP also noted the violet-blue coloration around the borders of the ulcers, which is referred to as a “gun-metal border.” He considered doing a biopsy on the edge of the ulcer to rule out other conditions and to see if there was a neutrophilic infiltrate that is typically seen with PG. However, the FP realized that pathergy could be stimulated by a biopsy, so he decided to refer the patient to Dermatology.

Knowing that the patient might have to wait a few months to see a dermatologist, the FP consulted online sources and prescribed topical clobetasol ointment to be applied twice daily as an initial therapy. This was not successful, so after a phone consult with the dermatologist, the FP added oral prednisone 40 mg/d for the next 2 weeks until the dermatologist could see the patient.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1147-1152.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized this as classic pyoderma gangrenosum (PG)—a challenging condition to treat and not within the typical scope of practice for an FP. Nonhealing, well-defined leg ulcers in a person with Crohn's disease (or any type of inflammatory bowel disease) are often seen with PG. Pathergy—the development of an exaggerated injury following minor trauma—is known to occur with PG.

The FP also noted the violet-blue coloration around the borders of the ulcers, which is referred to as a “gun-metal border.” He considered doing a biopsy on the edge of the ulcer to rule out other conditions and to see if there was a neutrophilic infiltrate that is typically seen with PG. However, the FP realized that pathergy could be stimulated by a biopsy, so he decided to refer the patient to Dermatology.

Knowing that the patient might have to wait a few months to see a dermatologist, the FP consulted online sources and prescribed topical clobetasol ointment to be applied twice daily as an initial therapy. This was not successful, so after a phone consult with the dermatologist, the FP added oral prednisone 40 mg/d for the next 2 weeks until the dermatologist could see the patient.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1147-1152.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Painless Nodule on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Plasmablastic Lymphoma

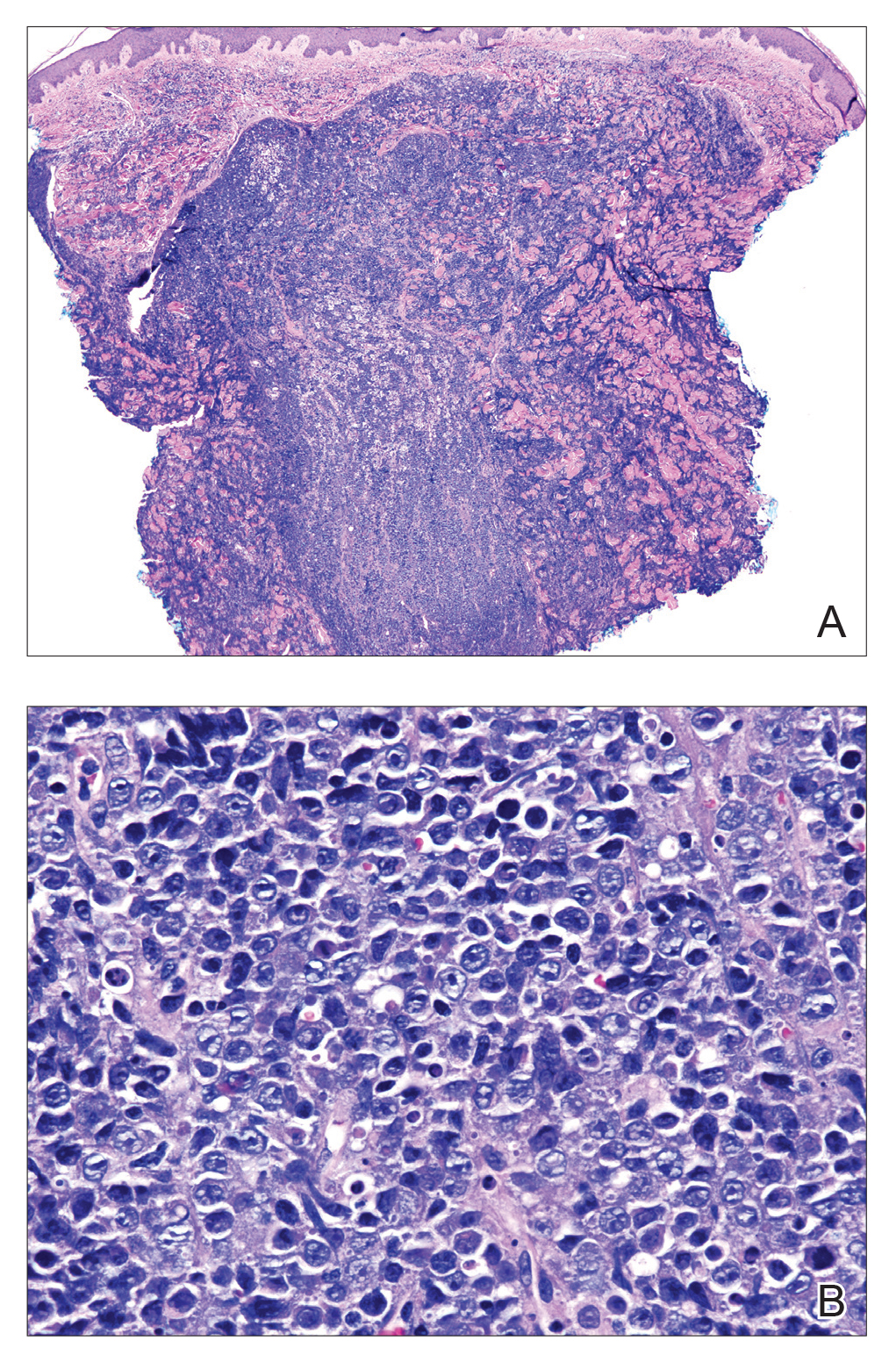

Histopathologic examination revealed a diffuse dense proliferation of large, atypical, and pleomorphic mononuclear cells with prominent nucleoli and many mitotic figures representing plasmacytoid cells in the dermis (Figure). Immunostaining was positive for MUM-1 (marker of late-stage plasma cells and activated T cells) and BCL-2 (antiapoptotic marker). Fluorescent polymerase chain reaction was positive for clonal IgH gene arrangement, and fluorescence in situ hybridization was positive for C-MYC rearrangement in 94% of cells. Epstein-Barr encoding region in situ hybridization also was positive. Rare cells stained positive for T-cell markers. CD20, BCL-6, and CD30 immunostains were negative, suggesting that these cells were not B or T cells, though terminally differentiated B cells also can lack these markers. Bone marrow biopsy showed a similar staining pattern to the skin with 10% atypical plasmacytoid cells. Computed tomography of the left leg showed an enlargement of the semimembranosus muscle with internal areas of high density and heterogeneous enhancement. The patient underwent decompression of the left peroneal nerve. Biopsy showed a staining pattern similar to the right skin nodule and bone marrow, consistent with lymphoma.

He was diagnosed with stage IV human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) and received 6 cycles of R-EPOCH (rituximab, etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) without vincristine with intrathecal methotrexate, followed by 3 cycles of DHAP (dexamethasone, high dose Ara C, cisplatin) with bortezomib and daratumumab after relapse. Ultimately, he underwent autologous stem cell transplantation and was alive 13 months after diagnosis.

Plasmablastic lymphoma is a rare subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that most commonly arises in the oral cavity of individuals with HIV.1 In addition to HIV infection, PBL also is seen in patients with other causes of immunodeficiency such as iatrogenic immunosuppression following solid organ transplantation.1 The typical disease presentation is an expanding mass in the oral cavity; however, 34% (52/151) of reported cases arose at extraoral primary sites, with a minority of cases confined to cutaneous sites with no systemic involvement.2 Cutaneous PBL presentations may include flesh-colored or purple, grouped or solitary nodules; an erythematous infiltrated plaque; or purple-red ulcerated nodules. The lesions usually are asymptomatic and located on the arms and legs.3

On histologic examination, PBL is characterized by a diffuse monomorphic lymphoid infiltrate that sometimes invades the surrounding soft tissue.4-6 The neoplastic cells have eccentric round nucleoli. Plasmablastic lymphoma characteristically displays a high proliferation index with many mitotic figures and signs of apoptosis.4-6 Definitive diagnosis requires immunohistochemical staining. Typical B-cell antigens (CD20) as well as CD45 are negative, while plasma cell markers such as CD38 are positive. Other B- and T-cell markers usually are negative.5,7 The pathogenesis of PBL is thought to be related to Epstein-Barr virus or human herpesvirus 8 infection. In a series of PBL cases, Epstein-Barr virus and human herpesvirus 8 was positive in 75% (97/129) and 17% (13/75) of tested cases, respectively.1

The prognosis for PBL is poor, with a median overall survival of 15 months and a 3-year survival rate of 25% in HIV-infected individuals.8 However, cutaneous PBL without systemic involvement has a considerably better prognosis, with only 1 of 12 cases resulting in death.2,3,9 Treatment of PBL depends on the extent of the disease. Cutaneous PBL can be treated with surgery and adjuvant radiation.3 Chemotherapy is required for patients with multiple lesions or systemic involvement. Current treatment regimens are similar to those used for other aggressive lymphomas such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone).1 Transplant recipients should have their immunosuppression reduced, and HIV-infected patients should have their highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens optimized. Patients presenting with PBL without HIV should be tested for HIV, as PBL has previously been reported to be the presenting manifestation of HIV infection.10

The differential diagnosis for a rapidly expanding, vascular-appearing, red mass on the legs in an immunosuppressed individual includes abscess, malignancy, Kaposi sarcoma, Sweet syndrome, and tertiary syphilis.

Acknowledgment

We thank Sameera Husain, MD (New York, New York), for her assistance with histopathologic photographs and interpretation.

- Riedel DJ, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Zhao XF, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity: a rapidly progressive lymphoma associated with HIV infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:261-267.

- Heiser D, Müller H, Kempf W, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma of the lower leg in an HIV-negative patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E202-E205.

- Jambusaria A, Shafer D, Wu H, et al. Cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:676-678.

- Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1997;89:1413-1420.

- Gaidano G, Cerri M, Capello D, et al. Molecular histogenesis of plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity. Br J Haematol. 2002;119:622-628.

- Folk GS, Abbondanzo SL, Childers EL, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma: a clinicopathologic correlation. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2006;10:8-12.

- Castillo JJ, Bibas M, Miranda RN. The biology and treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125:2323-2330.

- Castillo J, Pantanowitz L, Dezube BJ. HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma: lessons learned from 112 published cases. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:804-809.

- Horna P, Hamill JR, Sokol L, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma in an immunocompetent patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:E274-E276.

- Desai RS, Vanaki SS, Puranik RS, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma presenting as a gingival growth in a previously undiagnosed HIV-positive patient: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1358-1361.

The Diagnosis: Plasmablastic Lymphoma

Histopathologic examination revealed a diffuse dense proliferation of large, atypical, and pleomorphic mononuclear cells with prominent nucleoli and many mitotic figures representing plasmacytoid cells in the dermis (Figure). Immunostaining was positive for MUM-1 (marker of late-stage plasma cells and activated T cells) and BCL-2 (antiapoptotic marker). Fluorescent polymerase chain reaction was positive for clonal IgH gene arrangement, and fluorescence in situ hybridization was positive for C-MYC rearrangement in 94% of cells. Epstein-Barr encoding region in situ hybridization also was positive. Rare cells stained positive for T-cell markers. CD20, BCL-6, and CD30 immunostains were negative, suggesting that these cells were not B or T cells, though terminally differentiated B cells also can lack these markers. Bone marrow biopsy showed a similar staining pattern to the skin with 10% atypical plasmacytoid cells. Computed tomography of the left leg showed an enlargement of the semimembranosus muscle with internal areas of high density and heterogeneous enhancement. The patient underwent decompression of the left peroneal nerve. Biopsy showed a staining pattern similar to the right skin nodule and bone marrow, consistent with lymphoma.

He was diagnosed with stage IV human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) and received 6 cycles of R-EPOCH (rituximab, etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) without vincristine with intrathecal methotrexate, followed by 3 cycles of DHAP (dexamethasone, high dose Ara C, cisplatin) with bortezomib and daratumumab after relapse. Ultimately, he underwent autologous stem cell transplantation and was alive 13 months after diagnosis.

Plasmablastic lymphoma is a rare subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that most commonly arises in the oral cavity of individuals with HIV.1 In addition to HIV infection, PBL also is seen in patients with other causes of immunodeficiency such as iatrogenic immunosuppression following solid organ transplantation.1 The typical disease presentation is an expanding mass in the oral cavity; however, 34% (52/151) of reported cases arose at extraoral primary sites, with a minority of cases confined to cutaneous sites with no systemic involvement.2 Cutaneous PBL presentations may include flesh-colored or purple, grouped or solitary nodules; an erythematous infiltrated plaque; or purple-red ulcerated nodules. The lesions usually are asymptomatic and located on the arms and legs.3

On histologic examination, PBL is characterized by a diffuse monomorphic lymphoid infiltrate that sometimes invades the surrounding soft tissue.4-6 The neoplastic cells have eccentric round nucleoli. Plasmablastic lymphoma characteristically displays a high proliferation index with many mitotic figures and signs of apoptosis.4-6 Definitive diagnosis requires immunohistochemical staining. Typical B-cell antigens (CD20) as well as CD45 are negative, while plasma cell markers such as CD38 are positive. Other B- and T-cell markers usually are negative.5,7 The pathogenesis of PBL is thought to be related to Epstein-Barr virus or human herpesvirus 8 infection. In a series of PBL cases, Epstein-Barr virus and human herpesvirus 8 was positive in 75% (97/129) and 17% (13/75) of tested cases, respectively.1

The prognosis for PBL is poor, with a median overall survival of 15 months and a 3-year survival rate of 25% in HIV-infected individuals.8 However, cutaneous PBL without systemic involvement has a considerably better prognosis, with only 1 of 12 cases resulting in death.2,3,9 Treatment of PBL depends on the extent of the disease. Cutaneous PBL can be treated with surgery and adjuvant radiation.3 Chemotherapy is required for patients with multiple lesions or systemic involvement. Current treatment regimens are similar to those used for other aggressive lymphomas such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone).1 Transplant recipients should have their immunosuppression reduced, and HIV-infected patients should have their highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens optimized. Patients presenting with PBL without HIV should be tested for HIV, as PBL has previously been reported to be the presenting manifestation of HIV infection.10

The differential diagnosis for a rapidly expanding, vascular-appearing, red mass on the legs in an immunosuppressed individual includes abscess, malignancy, Kaposi sarcoma, Sweet syndrome, and tertiary syphilis.

Acknowledgment

We thank Sameera Husain, MD (New York, New York), for her assistance with histopathologic photographs and interpretation.

The Diagnosis: Plasmablastic Lymphoma

Histopathologic examination revealed a diffuse dense proliferation of large, atypical, and pleomorphic mononuclear cells with prominent nucleoli and many mitotic figures representing plasmacytoid cells in the dermis (Figure). Immunostaining was positive for MUM-1 (marker of late-stage plasma cells and activated T cells) and BCL-2 (antiapoptotic marker). Fluorescent polymerase chain reaction was positive for clonal IgH gene arrangement, and fluorescence in situ hybridization was positive for C-MYC rearrangement in 94% of cells. Epstein-Barr encoding region in situ hybridization also was positive. Rare cells stained positive for T-cell markers. CD20, BCL-6, and CD30 immunostains were negative, suggesting that these cells were not B or T cells, though terminally differentiated B cells also can lack these markers. Bone marrow biopsy showed a similar staining pattern to the skin with 10% atypical plasmacytoid cells. Computed tomography of the left leg showed an enlargement of the semimembranosus muscle with internal areas of high density and heterogeneous enhancement. The patient underwent decompression of the left peroneal nerve. Biopsy showed a staining pattern similar to the right skin nodule and bone marrow, consistent with lymphoma.

He was diagnosed with stage IV human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) and received 6 cycles of R-EPOCH (rituximab, etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) without vincristine with intrathecal methotrexate, followed by 3 cycles of DHAP (dexamethasone, high dose Ara C, cisplatin) with bortezomib and daratumumab after relapse. Ultimately, he underwent autologous stem cell transplantation and was alive 13 months after diagnosis.

Plasmablastic lymphoma is a rare subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that most commonly arises in the oral cavity of individuals with HIV.1 In addition to HIV infection, PBL also is seen in patients with other causes of immunodeficiency such as iatrogenic immunosuppression following solid organ transplantation.1 The typical disease presentation is an expanding mass in the oral cavity; however, 34% (52/151) of reported cases arose at extraoral primary sites, with a minority of cases confined to cutaneous sites with no systemic involvement.2 Cutaneous PBL presentations may include flesh-colored or purple, grouped or solitary nodules; an erythematous infiltrated plaque; or purple-red ulcerated nodules. The lesions usually are asymptomatic and located on the arms and legs.3

On histologic examination, PBL is characterized by a diffuse monomorphic lymphoid infiltrate that sometimes invades the surrounding soft tissue.4-6 The neoplastic cells have eccentric round nucleoli. Plasmablastic lymphoma characteristically displays a high proliferation index with many mitotic figures and signs of apoptosis.4-6 Definitive diagnosis requires immunohistochemical staining. Typical B-cell antigens (CD20) as well as CD45 are negative, while plasma cell markers such as CD38 are positive. Other B- and T-cell markers usually are negative.5,7 The pathogenesis of PBL is thought to be related to Epstein-Barr virus or human herpesvirus 8 infection. In a series of PBL cases, Epstein-Barr virus and human herpesvirus 8 was positive in 75% (97/129) and 17% (13/75) of tested cases, respectively.1

The prognosis for PBL is poor, with a median overall survival of 15 months and a 3-year survival rate of 25% in HIV-infected individuals.8 However, cutaneous PBL without systemic involvement has a considerably better prognosis, with only 1 of 12 cases resulting in death.2,3,9 Treatment of PBL depends on the extent of the disease. Cutaneous PBL can be treated with surgery and adjuvant radiation.3 Chemotherapy is required for patients with multiple lesions or systemic involvement. Current treatment regimens are similar to those used for other aggressive lymphomas such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone).1 Transplant recipients should have their immunosuppression reduced, and HIV-infected patients should have their highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens optimized. Patients presenting with PBL without HIV should be tested for HIV, as PBL has previously been reported to be the presenting manifestation of HIV infection.10

The differential diagnosis for a rapidly expanding, vascular-appearing, red mass on the legs in an immunosuppressed individual includes abscess, malignancy, Kaposi sarcoma, Sweet syndrome, and tertiary syphilis.

Acknowledgment

We thank Sameera Husain, MD (New York, New York), for her assistance with histopathologic photographs and interpretation.

- Riedel DJ, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Zhao XF, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity: a rapidly progressive lymphoma associated with HIV infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:261-267.

- Heiser D, Müller H, Kempf W, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma of the lower leg in an HIV-negative patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E202-E205.

- Jambusaria A, Shafer D, Wu H, et al. Cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:676-678.

- Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1997;89:1413-1420.

- Gaidano G, Cerri M, Capello D, et al. Molecular histogenesis of plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity. Br J Haematol. 2002;119:622-628.

- Folk GS, Abbondanzo SL, Childers EL, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma: a clinicopathologic correlation. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2006;10:8-12.

- Castillo JJ, Bibas M, Miranda RN. The biology and treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125:2323-2330.

- Castillo J, Pantanowitz L, Dezube BJ. HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma: lessons learned from 112 published cases. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:804-809.

- Horna P, Hamill JR, Sokol L, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma in an immunocompetent patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:E274-E276.

- Desai RS, Vanaki SS, Puranik RS, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma presenting as a gingival growth in a previously undiagnosed HIV-positive patient: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1358-1361.

- Riedel DJ, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Zhao XF, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity: a rapidly progressive lymphoma associated with HIV infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:261-267.

- Heiser D, Müller H, Kempf W, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma of the lower leg in an HIV-negative patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E202-E205.

- Jambusaria A, Shafer D, Wu H, et al. Cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:676-678.

- Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1997;89:1413-1420.

- Gaidano G, Cerri M, Capello D, et al. Molecular histogenesis of plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity. Br J Haematol. 2002;119:622-628.

- Folk GS, Abbondanzo SL, Childers EL, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma: a clinicopathologic correlation. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2006;10:8-12.

- Castillo JJ, Bibas M, Miranda RN. The biology and treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125:2323-2330.

- Castillo J, Pantanowitz L, Dezube BJ. HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma: lessons learned from 112 published cases. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:804-809.

- Horna P, Hamill JR, Sokol L, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma in an immunocompetent patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:E274-E276.

- Desai RS, Vanaki SS, Puranik RS, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma presenting as a gingival growth in a previously undiagnosed HIV-positive patient: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1358-1361.

A 44-year-old man presented with numbness and a burning sensation of the left lateral leg and dorsal foot of 3 days' duration as well as a left foot drop of 1 day's duration. A painless red nodule on the right shin also developed over a 10-day period. He had been diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus a year prior and reported compliance with antiretroviral therapy. There was a newly identified, well-demarcated, 6-cm, round, red-purple, flat-topped, nodular tumor with central depression on the right lateral shin. Ultrasonography of the nodule revealed a heterogeneous septate structure with increased vascularity. There was no regional or generalized lymphadenopathy. Laboratory values were notable for microcytic anemia. The white blood cell count was within reference range. Human immunodeficiency virus RNA viral load was elevated (3183 viral copies/mL [reference range, <20 viral copies/mL]). Two punch biopsies of the nodule were performed.

Practical advice for colorectal cancer screening

Douglas K. Rex, MD, AGAF, MACP, MACG, FASGE; offers advice and insight for colorectal cancer screening, highlighting:

- Clinically relevant facts about the spectrum of precancerous lesions that can be targeted during screening;

- Key practical aspects of the 3 screening tests that receive significant use in the United States.

- Why some tests are used more than others

Click HERE to read the supplement

Douglas K. Rex, MD, AGAF, MACP, MACG, FASGE; offers advice and insight for colorectal cancer screening, highlighting:

- Clinically relevant facts about the spectrum of precancerous lesions that can be targeted during screening;

- Key practical aspects of the 3 screening tests that receive significant use in the United States.

- Why some tests are used more than others

Click HERE to read the supplement

Douglas K. Rex, MD, AGAF, MACP, MACG, FASGE; offers advice and insight for colorectal cancer screening, highlighting:

- Clinically relevant facts about the spectrum of precancerous lesions that can be targeted during screening;

- Key practical aspects of the 3 screening tests that receive significant use in the United States.

- Why some tests are used more than others

Click HERE to read the supplement

Medicaid expansion associated with lower cardiovascular mortality

Counties in states that expanded Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act have experienced a significantly smaller increase in cardiovascular mortality rates among middle-aged adults, compared with counties in states that did not expand coverage, according to findings from a new study.

In expansion-state counties, the change in cardiovascular mortality was stable between the pre-expansion (2010-2013) and postexpansion (2014-2016) periods, at 146.5-146.4 deaths per 100,000 residents per year, compared with mortality rates in nonexpansion counties during the same periods (176.3-180.9 deaths per 100,000), Sameed Ahmed M. Khatana, MD, and colleagues wrote in JAMA Cardiology.

“After accounting for demographic, clinical, and economic differences, counties in expansion states had 4.3 fewer deaths per 100,000 residents per year from cardiovascular causes after Medicaid expansion than if they had followed the same trends as counties in nonexpansion states,” Dr. Khatana, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues wrote..

That translated into 2,039 fewer total deaths per year in residents aged between 45 and 64 years from cardiovascular causes after Medicaid expansion, the authors noted.

In all, 29 states, plus Washington, D.C., were included in the expansion group, and 19 states were in the nonexpansion (control) group. During the study period, from 2010 to 2016, the number of expansion counties ranged between 912 and 931, and for the nonexpansion counties, between 985 and 1,029. About half of the residents in each group were women. The percentage of black residents was lower in expansion states, but the percentage of Hispanic residents did not differ. Compared with nonexpansion counties, expansion counties also had a lower prevalence of diabetes (8.5% vs. 9.7% in the nonexpansion counties), obesity (26.2% vs. 29.1%), and smoking (17.1 vs. 18.9%); a lower mean percentage of poor residents (14.4% vs 16.6%; all with P less than .001); and a higher median household income.

Expansion counties also fared better when it came to health insurance coverage. In 2010, 14.6% of their residents had no coverage, compared with 19.5% of residents in nonexpansion counties. During the study period, the decrease in the percentage of middle-aged residents without health coverage was larger in expansion than in nonexpansion counties (7.3% vs. 5.6%, respectively), as was the decrease in low-income residents without coverage (19.8% vs. 13.5%).

However, the authors cautioned that, given the observational nature of the study, they were “not able to make a causal association between expansion of Medicaid eligibility and differences in the cardiovascular mortality rates between the two groups of counties. It is possible that there were other unmeasured time varying factors that can explain the observed association.”

Despite that limitation of the study, which observed adults in all income categories and was not limited to low-income residents, the researchers noted that, given the association between Medicaid expansion and cardiovascular mortality rates, as well as the “high burden of cardiovascular risk factors among individuals without insurance and those with lower socioeconomic status,” policy makers might consider the results in future discussions about changes to eligibility for and expansion of Medicaid.

Dr. Khatana is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Two authors reported relationships with drug companies outside of the reported study; the rest of the authors had no disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Khatana SAM et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Jun 5. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.1651.

Counties in states that expanded Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act have experienced a significantly smaller increase in cardiovascular mortality rates among middle-aged adults, compared with counties in states that did not expand coverage, according to findings from a new study.

In expansion-state counties, the change in cardiovascular mortality was stable between the pre-expansion (2010-2013) and postexpansion (2014-2016) periods, at 146.5-146.4 deaths per 100,000 residents per year, compared with mortality rates in nonexpansion counties during the same periods (176.3-180.9 deaths per 100,000), Sameed Ahmed M. Khatana, MD, and colleagues wrote in JAMA Cardiology.

“After accounting for demographic, clinical, and economic differences, counties in expansion states had 4.3 fewer deaths per 100,000 residents per year from cardiovascular causes after Medicaid expansion than if they had followed the same trends as counties in nonexpansion states,” Dr. Khatana, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues wrote..

That translated into 2,039 fewer total deaths per year in residents aged between 45 and 64 years from cardiovascular causes after Medicaid expansion, the authors noted.

In all, 29 states, plus Washington, D.C., were included in the expansion group, and 19 states were in the nonexpansion (control) group. During the study period, from 2010 to 2016, the number of expansion counties ranged between 912 and 931, and for the nonexpansion counties, between 985 and 1,029. About half of the residents in each group were women. The percentage of black residents was lower in expansion states, but the percentage of Hispanic residents did not differ. Compared with nonexpansion counties, expansion counties also had a lower prevalence of diabetes (8.5% vs. 9.7% in the nonexpansion counties), obesity (26.2% vs. 29.1%), and smoking (17.1 vs. 18.9%); a lower mean percentage of poor residents (14.4% vs 16.6%; all with P less than .001); and a higher median household income.

Expansion counties also fared better when it came to health insurance coverage. In 2010, 14.6% of their residents had no coverage, compared with 19.5% of residents in nonexpansion counties. During the study period, the decrease in the percentage of middle-aged residents without health coverage was larger in expansion than in nonexpansion counties (7.3% vs. 5.6%, respectively), as was the decrease in low-income residents without coverage (19.8% vs. 13.5%).

However, the authors cautioned that, given the observational nature of the study, they were “not able to make a causal association between expansion of Medicaid eligibility and differences in the cardiovascular mortality rates between the two groups of counties. It is possible that there were other unmeasured time varying factors that can explain the observed association.”

Despite that limitation of the study, which observed adults in all income categories and was not limited to low-income residents, the researchers noted that, given the association between Medicaid expansion and cardiovascular mortality rates, as well as the “high burden of cardiovascular risk factors among individuals without insurance and those with lower socioeconomic status,” policy makers might consider the results in future discussions about changes to eligibility for and expansion of Medicaid.

Dr. Khatana is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Two authors reported relationships with drug companies outside of the reported study; the rest of the authors had no disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Khatana SAM et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Jun 5. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.1651.

Counties in states that expanded Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act have experienced a significantly smaller increase in cardiovascular mortality rates among middle-aged adults, compared with counties in states that did not expand coverage, according to findings from a new study.

In expansion-state counties, the change in cardiovascular mortality was stable between the pre-expansion (2010-2013) and postexpansion (2014-2016) periods, at 146.5-146.4 deaths per 100,000 residents per year, compared with mortality rates in nonexpansion counties during the same periods (176.3-180.9 deaths per 100,000), Sameed Ahmed M. Khatana, MD, and colleagues wrote in JAMA Cardiology.

“After accounting for demographic, clinical, and economic differences, counties in expansion states had 4.3 fewer deaths per 100,000 residents per year from cardiovascular causes after Medicaid expansion than if they had followed the same trends as counties in nonexpansion states,” Dr. Khatana, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues wrote..

That translated into 2,039 fewer total deaths per year in residents aged between 45 and 64 years from cardiovascular causes after Medicaid expansion, the authors noted.

In all, 29 states, plus Washington, D.C., were included in the expansion group, and 19 states were in the nonexpansion (control) group. During the study period, from 2010 to 2016, the number of expansion counties ranged between 912 and 931, and for the nonexpansion counties, between 985 and 1,029. About half of the residents in each group were women. The percentage of black residents was lower in expansion states, but the percentage of Hispanic residents did not differ. Compared with nonexpansion counties, expansion counties also had a lower prevalence of diabetes (8.5% vs. 9.7% in the nonexpansion counties), obesity (26.2% vs. 29.1%), and smoking (17.1 vs. 18.9%); a lower mean percentage of poor residents (14.4% vs 16.6%; all with P less than .001); and a higher median household income.

Expansion counties also fared better when it came to health insurance coverage. In 2010, 14.6% of their residents had no coverage, compared with 19.5% of residents in nonexpansion counties. During the study period, the decrease in the percentage of middle-aged residents without health coverage was larger in expansion than in nonexpansion counties (7.3% vs. 5.6%, respectively), as was the decrease in low-income residents without coverage (19.8% vs. 13.5%).

However, the authors cautioned that, given the observational nature of the study, they were “not able to make a causal association between expansion of Medicaid eligibility and differences in the cardiovascular mortality rates between the two groups of counties. It is possible that there were other unmeasured time varying factors that can explain the observed association.”

Despite that limitation of the study, which observed adults in all income categories and was not limited to low-income residents, the researchers noted that, given the association between Medicaid expansion and cardiovascular mortality rates, as well as the “high burden of cardiovascular risk factors among individuals without insurance and those with lower socioeconomic status,” policy makers might consider the results in future discussions about changes to eligibility for and expansion of Medicaid.

Dr. Khatana is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Two authors reported relationships with drug companies outside of the reported study; the rest of the authors had no disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Khatana SAM et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Jun 5. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.1651.

FROM JAMA CARDIOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Counties in expansion states had 4.3 fewer deaths from cardiovascular causes per 100,000 residents per year after Medicaid expansion, compared with counties in nonexpansion states.

Study details: In this longitudinal, observational study from 2010 to 2016, researchers used a difference-in-difference approach with county-level data for adults from 48 states (excluding Massachusetts and Wisconsin) and Washington, D.C., who were aged between 45 and 64 years. The county-level data were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Online Data for Epidemiologic Research mortality database.

Disclosures: Dr. Khatana is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Two authors reported relationships with drug companies outside of the reported study; the rest of the authors had no disclosures to report.

Source: Khatana SAM et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Jun 5. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.1651.

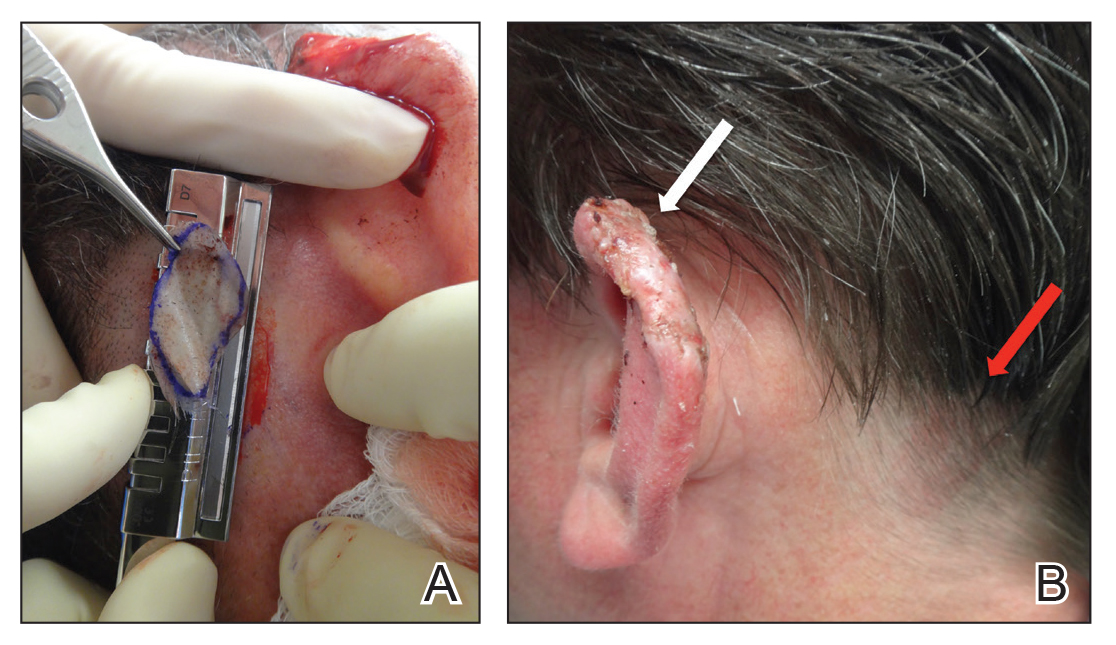

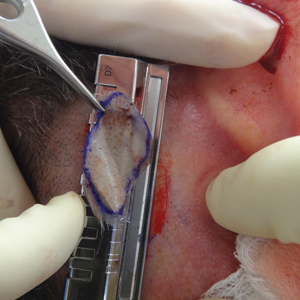

When the Right Medication Has the Wrong Effect

For several years, this 16-year-old boy has had severe acne on his chest and back. The condition has steadily worsened despite use of OTC medications, including benzoyl peroxide–containing topical products. He has never received prescription treatment. His primary care provider, concerned that something more than acne could be involved, refers him to dermatology for evaluation and treatment.

The boy’s health is reportedly otherwise excellent. Family history is positive for severe acne on both sides of his family; two of his older siblings have had similar problems.

EXAMINATION

The central portion of the boy’s chest is covered by an impressive collection of discrete and confluent crusts and erosions. Some are quite deep, and the patient admits to picking at them. Little if any erythema surrounds the lesions.

Very little acne is seen on the boy’s face, but fairly dense acne vulgaris is observed on his upper back.

Following a brief but thorough discussion, the decision is made to start therapy with low-dose isotretinoin (20 mg/d), after the appropriate bloodwork is obtained. Within a week, the patient presents to the emergency department (ED) for worsening of his chest acne, along with pain and bleeding from some of the lesions.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The risk for granulation tissue formation is a well-known though rare adverse effect of isotretinoin use—one that had been discussed thoroughly with the patient and his parents prior to prescription. There is no unanimity of opinion regarding the mechanism whereby this response occurs, but it is real. It can affect such areas as seen in this patient’s case but also causes a similar problem in the perionychial tissues, creating a condition quite similar to an ingrown toenail (cryptonychia). This author has also seen the same phenomenon in fingernails.

In this patient’s case, after discharge from the ED, he presented immediately to his primary care provider, who in turn called the dermatology clinic. When we saw him, there was clear evidence of inappropriate granulation formation—far worse than the initial acne had been.

The patient was given an intramuscular injection of 40 mg triamcinolone and prescribed minocycline 100 mg bid. He had already stopped taking the isotretinoin and was strongly advised not to restart it for the foreseeable future. In hindsight, he probably should have been started on minocycline and a 3-week prednisone taper to calm down his chest acne before the isotretinoin was started.

At a follow-up appointment 3 weeks later, his condition was much improved (at least back to baseline). But he will almost certainly develop hypertrophic scarring on his chest—and given the severity of his acne and the strong family history, he may well have a suboptimal response to isotretinoin when and if we return to that medication.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- In rare instances, isotretinoin therapy can trigger the formation of inappropriate granulation tissue on the face, back, chest, and even perionychial areas.

- There is evidence that the more inflamed the acne, the greater the likelihood of this adverse effect.

- With severely inflamed acne, consideration should be given to using small initial doses of isotretinoin or decreasing the inflammation through use of systemic steroids or doxycycline or minocycline.

For several years, this 16-year-old boy has had severe acne on his chest and back. The condition has steadily worsened despite use of OTC medications, including benzoyl peroxide–containing topical products. He has never received prescription treatment. His primary care provider, concerned that something more than acne could be involved, refers him to dermatology for evaluation and treatment.

The boy’s health is reportedly otherwise excellent. Family history is positive for severe acne on both sides of his family; two of his older siblings have had similar problems.

EXAMINATION

The central portion of the boy’s chest is covered by an impressive collection of discrete and confluent crusts and erosions. Some are quite deep, and the patient admits to picking at them. Little if any erythema surrounds the lesions.

Very little acne is seen on the boy’s face, but fairly dense acne vulgaris is observed on his upper back.

Following a brief but thorough discussion, the decision is made to start therapy with low-dose isotretinoin (20 mg/d), after the appropriate bloodwork is obtained. Within a week, the patient presents to the emergency department (ED) for worsening of his chest acne, along with pain and bleeding from some of the lesions.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The risk for granulation tissue formation is a well-known though rare adverse effect of isotretinoin use—one that had been discussed thoroughly with the patient and his parents prior to prescription. There is no unanimity of opinion regarding the mechanism whereby this response occurs, but it is real. It can affect such areas as seen in this patient’s case but also causes a similar problem in the perionychial tissues, creating a condition quite similar to an ingrown toenail (cryptonychia). This author has also seen the same phenomenon in fingernails.

In this patient’s case, after discharge from the ED, he presented immediately to his primary care provider, who in turn called the dermatology clinic. When we saw him, there was clear evidence of inappropriate granulation formation—far worse than the initial acne had been.

The patient was given an intramuscular injection of 40 mg triamcinolone and prescribed minocycline 100 mg bid. He had already stopped taking the isotretinoin and was strongly advised not to restart it for the foreseeable future. In hindsight, he probably should have been started on minocycline and a 3-week prednisone taper to calm down his chest acne before the isotretinoin was started.

At a follow-up appointment 3 weeks later, his condition was much improved (at least back to baseline). But he will almost certainly develop hypertrophic scarring on his chest—and given the severity of his acne and the strong family history, he may well have a suboptimal response to isotretinoin when and if we return to that medication.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- In rare instances, isotretinoin therapy can trigger the formation of inappropriate granulation tissue on the face, back, chest, and even perionychial areas.

- There is evidence that the more inflamed the acne, the greater the likelihood of this adverse effect.

- With severely inflamed acne, consideration should be given to using small initial doses of isotretinoin or decreasing the inflammation through use of systemic steroids or doxycycline or minocycline.

For several years, this 16-year-old boy has had severe acne on his chest and back. The condition has steadily worsened despite use of OTC medications, including benzoyl peroxide–containing topical products. He has never received prescription treatment. His primary care provider, concerned that something more than acne could be involved, refers him to dermatology for evaluation and treatment.

The boy’s health is reportedly otherwise excellent. Family history is positive for severe acne on both sides of his family; two of his older siblings have had similar problems.

EXAMINATION

The central portion of the boy’s chest is covered by an impressive collection of discrete and confluent crusts and erosions. Some are quite deep, and the patient admits to picking at them. Little if any erythema surrounds the lesions.

Very little acne is seen on the boy’s face, but fairly dense acne vulgaris is observed on his upper back.

Following a brief but thorough discussion, the decision is made to start therapy with low-dose isotretinoin (20 mg/d), after the appropriate bloodwork is obtained. Within a week, the patient presents to the emergency department (ED) for worsening of his chest acne, along with pain and bleeding from some of the lesions.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The risk for granulation tissue formation is a well-known though rare adverse effect of isotretinoin use—one that had been discussed thoroughly with the patient and his parents prior to prescription. There is no unanimity of opinion regarding the mechanism whereby this response occurs, but it is real. It can affect such areas as seen in this patient’s case but also causes a similar problem in the perionychial tissues, creating a condition quite similar to an ingrown toenail (cryptonychia). This author has also seen the same phenomenon in fingernails.

In this patient’s case, after discharge from the ED, he presented immediately to his primary care provider, who in turn called the dermatology clinic. When we saw him, there was clear evidence of inappropriate granulation formation—far worse than the initial acne had been.

The patient was given an intramuscular injection of 40 mg triamcinolone and prescribed minocycline 100 mg bid. He had already stopped taking the isotretinoin and was strongly advised not to restart it for the foreseeable future. In hindsight, he probably should have been started on minocycline and a 3-week prednisone taper to calm down his chest acne before the isotretinoin was started.

At a follow-up appointment 3 weeks later, his condition was much improved (at least back to baseline). But he will almost certainly develop hypertrophic scarring on his chest—and given the severity of his acne and the strong family history, he may well have a suboptimal response to isotretinoin when and if we return to that medication.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- In rare instances, isotretinoin therapy can trigger the formation of inappropriate granulation tissue on the face, back, chest, and even perionychial areas.

- There is evidence that the more inflamed the acne, the greater the likelihood of this adverse effect.

- With severely inflamed acne, consideration should be given to using small initial doses of isotretinoin or decreasing the inflammation through use of systemic steroids or doxycycline or minocycline.

Pain coping skills training doesn’t improve knee arthroplasty outcomes

TORONTO – A high level of pain catastrophizing prior to scheduled knee arthroplasty is not, as previously thought, a harbinger of poor outcomes, and affected patients don’t benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy–based training in pain coping skills, Daniel L. Riddle, PhD, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

“The take-home message for us is knee arthroplasty is incredibly effective and there really is no reason to do pain coping skills training in these high–pain catastrophizing patients because the great majority of them have such good outcomes,” said Dr. Riddle, professor of physical therapy at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

“The other clear message from our trial is that, when you have pain-catastrophizing patients and you lower their pain, their catastrophizing is also lowered. So pain catastrophizing is clearly a response to pain and not a personality trait per se,” he said at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

He presented the results of a 402-patient, randomized, three-arm, single-blind trial conducted at five U.S. medical centers. All participants were scheduled for knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis, and all had moderate- to high-level pain catastrophizing as reflected in the group’s average Pain Catastrophizing Score of 30. They were assigned to an arthritis education active control group, usual care, or an intervention developed specifically for this study: a cognitive-behavioral therapy–based training program for pain coping skills. Similar pain coping skills training interventions have been shown to be beneficial in patients with medically treated knee OA but hadn’t previously been evaluated in surgically treated patients. The primary study endpoint was change in the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) Pain Scale at 2, 6, and 12 months after surgery.

The improvement in WOMAC pain in the three study arms was virtually superimposable, going from an average pain score of about 12 preoperatively to 2 postoperatively.

“This was a clear no-effect trial,” Dr. Riddle observed. “These are patients we thought to be at increased risk for poor outcome, but indeed they’re not.”

Pain Catastrophizing Scores improved from 30 preoperatively to roughly 7 at 1 year. “We’ve never seen pain catastrophizing improvements of this magnitude,” the researcher commented.

The study participants typically had a large number of chronically painful areas, but only minimal change in pain scores occurred except in the surgically treated knee.

Of note, even with the impressively large improvements in knee pain, function, and other secondary endpoints in the study group as a whole, roughly 20% of study participants experienced essentially no improvement in their function-limiting knee pain during the first year after arthroplasty. These nonresponders were spread equally across all three study arms. Further research will be needed to develop interventions to help this challenging patient subgroup.

The pain coping skills training consisted of 8 weekly sessions, each an hour long, which began prior to surgery and continued afterward. The intervention was delivered by physical therapists who had been trained by pain psychologists with expertise in cognitive-behavioral therapy. The intervention was delivered by telephone and in face-to-face sessions. The trainers were tracked over the course of the study to make sure that the structured intervention was delivered as planned.

Dr. Riddle reported having no financial conflicts regarding the National Institutes of Health-funded study, the full details of which have been published (J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019 Feb 6;101[3]:218-227).

TORONTO – A high level of pain catastrophizing prior to scheduled knee arthroplasty is not, as previously thought, a harbinger of poor outcomes, and affected patients don’t benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy–based training in pain coping skills, Daniel L. Riddle, PhD, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

“The take-home message for us is knee arthroplasty is incredibly effective and there really is no reason to do pain coping skills training in these high–pain catastrophizing patients because the great majority of them have such good outcomes,” said Dr. Riddle, professor of physical therapy at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

“The other clear message from our trial is that, when you have pain-catastrophizing patients and you lower their pain, their catastrophizing is also lowered. So pain catastrophizing is clearly a response to pain and not a personality trait per se,” he said at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

He presented the results of a 402-patient, randomized, three-arm, single-blind trial conducted at five U.S. medical centers. All participants were scheduled for knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis, and all had moderate- to high-level pain catastrophizing as reflected in the group’s average Pain Catastrophizing Score of 30. They were assigned to an arthritis education active control group, usual care, or an intervention developed specifically for this study: a cognitive-behavioral therapy–based training program for pain coping skills. Similar pain coping skills training interventions have been shown to be beneficial in patients with medically treated knee OA but hadn’t previously been evaluated in surgically treated patients. The primary study endpoint was change in the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) Pain Scale at 2, 6, and 12 months after surgery.

The improvement in WOMAC pain in the three study arms was virtually superimposable, going from an average pain score of about 12 preoperatively to 2 postoperatively.

“This was a clear no-effect trial,” Dr. Riddle observed. “These are patients we thought to be at increased risk for poor outcome, but indeed they’re not.”

Pain Catastrophizing Scores improved from 30 preoperatively to roughly 7 at 1 year. “We’ve never seen pain catastrophizing improvements of this magnitude,” the researcher commented.

The study participants typically had a large number of chronically painful areas, but only minimal change in pain scores occurred except in the surgically treated knee.

Of note, even with the impressively large improvements in knee pain, function, and other secondary endpoints in the study group as a whole, roughly 20% of study participants experienced essentially no improvement in their function-limiting knee pain during the first year after arthroplasty. These nonresponders were spread equally across all three study arms. Further research will be needed to develop interventions to help this challenging patient subgroup.

The pain coping skills training consisted of 8 weekly sessions, each an hour long, which began prior to surgery and continued afterward. The intervention was delivered by physical therapists who had been trained by pain psychologists with expertise in cognitive-behavioral therapy. The intervention was delivered by telephone and in face-to-face sessions. The trainers were tracked over the course of the study to make sure that the structured intervention was delivered as planned.

Dr. Riddle reported having no financial conflicts regarding the National Institutes of Health-funded study, the full details of which have been published (J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019 Feb 6;101[3]:218-227).

TORONTO – A high level of pain catastrophizing prior to scheduled knee arthroplasty is not, as previously thought, a harbinger of poor outcomes, and affected patients don’t benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy–based training in pain coping skills, Daniel L. Riddle, PhD, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

“The take-home message for us is knee arthroplasty is incredibly effective and there really is no reason to do pain coping skills training in these high–pain catastrophizing patients because the great majority of them have such good outcomes,” said Dr. Riddle, professor of physical therapy at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

“The other clear message from our trial is that, when you have pain-catastrophizing patients and you lower their pain, their catastrophizing is also lowered. So pain catastrophizing is clearly a response to pain and not a personality trait per se,” he said at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

He presented the results of a 402-patient, randomized, three-arm, single-blind trial conducted at five U.S. medical centers. All participants were scheduled for knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis, and all had moderate- to high-level pain catastrophizing as reflected in the group’s average Pain Catastrophizing Score of 30. They were assigned to an arthritis education active control group, usual care, or an intervention developed specifically for this study: a cognitive-behavioral therapy–based training program for pain coping skills. Similar pain coping skills training interventions have been shown to be beneficial in patients with medically treated knee OA but hadn’t previously been evaluated in surgically treated patients. The primary study endpoint was change in the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) Pain Scale at 2, 6, and 12 months after surgery.

The improvement in WOMAC pain in the three study arms was virtually superimposable, going from an average pain score of about 12 preoperatively to 2 postoperatively.

“This was a clear no-effect trial,” Dr. Riddle observed. “These are patients we thought to be at increased risk for poor outcome, but indeed they’re not.”

Pain Catastrophizing Scores improved from 30 preoperatively to roughly 7 at 1 year. “We’ve never seen pain catastrophizing improvements of this magnitude,” the researcher commented.

The study participants typically had a large number of chronically painful areas, but only minimal change in pain scores occurred except in the surgically treated knee.

Of note, even with the impressively large improvements in knee pain, function, and other secondary endpoints in the study group as a whole, roughly 20% of study participants experienced essentially no improvement in their function-limiting knee pain during the first year after arthroplasty. These nonresponders were spread equally across all three study arms. Further research will be needed to develop interventions to help this challenging patient subgroup.

The pain coping skills training consisted of 8 weekly sessions, each an hour long, which began prior to surgery and continued afterward. The intervention was delivered by physical therapists who had been trained by pain psychologists with expertise in cognitive-behavioral therapy. The intervention was delivered by telephone and in face-to-face sessions. The trainers were tracked over the course of the study to make sure that the structured intervention was delivered as planned.

Dr. Riddle reported having no financial conflicts regarding the National Institutes of Health-funded study, the full details of which have been published (J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019 Feb 6;101[3]:218-227).

REPORTING FROM OARSI 2019

Stewart Tepper: Emgality approval ‘very exciting’

The drug, a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), is administered by self-injection in 300-mg doses.

Galcanezumab is the first medication for episodic cluster headache that reduces the frequency of attacks, the agency said in an announcement.

Cluster headache can be more intense than migraine. The pain is unilateral and occurs in the orbital, supraorbital, or temporal regions. It reaches its peak intensity within 5-10 minutes and generally lasts for 30-90 minutes. Symptoms include a burning sensation, conjunctival injection, rhinorrhea, and photosensitivity. Patients often have one to three of these headaches per day, and the headaches appear to be linked to the circadian rhythm. An episodic cluster cycle can last for weeks to months of daily or near daily attacks.

A study presented at the recent meeting of the American Academy of Neurology provided evidence of the drug’s efficacy in cluster headache. In this trial, researchers randomized 106 patients with episodic cluster headache to galcanezumab or placebo. The baseline cluster headache frequency was 17.3 attacks per week, and galcanezumab reduced this frequency to 9.1 attacks per week, compared with 12.1 attacks per week with placebo. The most common side effect reported in this and other clinical trials was injection-site reactions.

Galcanezumab entails a risk of hypersensitivity reactions, according to the FDA. These reactions may occur several days after administration and may be prolonged. “If a serious hypersensitivity reaction occurs, treatment should be discontinued,” the agency said.

“It’s a very exciting day. There had never been a drug approved for prevention of cluster headache,” said Stewart J. Tepper, MD, professor of neurology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and director of the Dartmouth Headache Center, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

It is difficult to achieve therapeutic concentrations of current preventive medications that do not have FDA approval for this indication, such as verapamil, lithium, or antiepileptic drugs. Galcanezumab, in contrast, works quickly. It is important to note that the approval was for preventive treatment of episodic cluster headache, not for prevention of chronic cluster headache, and not for acute treatment, Dr. Tepper said.

“It’s important to get optimal therapy for cluster headache. It is one of the most disabling, terrible disorders on Earth,” Dr. Tepper said. “The importance [of this approval] cannot be overestimated.”

When asked for comment, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, said “If this monoclonal antibody to the CGRP ligand works as well in real life as in the trial, it will be an important advance in the treatment of cluster headache.”

Prior to the approval of galcanezumab, noninvasive vagal nerve stimulation was approved in November 2018 for adjunctive use in the preventive treatment of cluster headache in adults.

The FDA granted the application for galcanezumab using a Priority Review and Breakthrough Therapy designation. The agency approved galcanezumab for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults in September 2018. The drug appears to have a similar safety profile in both patient populations. Eli Lilly, which is based in Indianapolis, Indiana, manufactures the drug.

This article was updated June 5, 2019.

The drug, a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), is administered by self-injection in 300-mg doses.

Galcanezumab is the first medication for episodic cluster headache that reduces the frequency of attacks, the agency said in an announcement.

Cluster headache can be more intense than migraine. The pain is unilateral and occurs in the orbital, supraorbital, or temporal regions. It reaches its peak intensity within 5-10 minutes and generally lasts for 30-90 minutes. Symptoms include a burning sensation, conjunctival injection, rhinorrhea, and photosensitivity. Patients often have one to three of these headaches per day, and the headaches appear to be linked to the circadian rhythm. An episodic cluster cycle can last for weeks to months of daily or near daily attacks.

A study presented at the recent meeting of the American Academy of Neurology provided evidence of the drug’s efficacy in cluster headache. In this trial, researchers randomized 106 patients with episodic cluster headache to galcanezumab or placebo. The baseline cluster headache frequency was 17.3 attacks per week, and galcanezumab reduced this frequency to 9.1 attacks per week, compared with 12.1 attacks per week with placebo. The most common side effect reported in this and other clinical trials was injection-site reactions.

Galcanezumab entails a risk of hypersensitivity reactions, according to the FDA. These reactions may occur several days after administration and may be prolonged. “If a serious hypersensitivity reaction occurs, treatment should be discontinued,” the agency said.

“It’s a very exciting day. There had never been a drug approved for prevention of cluster headache,” said Stewart J. Tepper, MD, professor of neurology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and director of the Dartmouth Headache Center, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

It is difficult to achieve therapeutic concentrations of current preventive medications that do not have FDA approval for this indication, such as verapamil, lithium, or antiepileptic drugs. Galcanezumab, in contrast, works quickly. It is important to note that the approval was for preventive treatment of episodic cluster headache, not for prevention of chronic cluster headache, and not for acute treatment, Dr. Tepper said.

“It’s important to get optimal therapy for cluster headache. It is one of the most disabling, terrible disorders on Earth,” Dr. Tepper said. “The importance [of this approval] cannot be overestimated.”

When asked for comment, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, said “If this monoclonal antibody to the CGRP ligand works as well in real life as in the trial, it will be an important advance in the treatment of cluster headache.”

Prior to the approval of galcanezumab, noninvasive vagal nerve stimulation was approved in November 2018 for adjunctive use in the preventive treatment of cluster headache in adults.

The FDA granted the application for galcanezumab using a Priority Review and Breakthrough Therapy designation. The agency approved galcanezumab for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults in September 2018. The drug appears to have a similar safety profile in both patient populations. Eli Lilly, which is based in Indianapolis, Indiana, manufactures the drug.

This article was updated June 5, 2019.

The drug, a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), is administered by self-injection in 300-mg doses.

Galcanezumab is the first medication for episodic cluster headache that reduces the frequency of attacks, the agency said in an announcement.

Cluster headache can be more intense than migraine. The pain is unilateral and occurs in the orbital, supraorbital, or temporal regions. It reaches its peak intensity within 5-10 minutes and generally lasts for 30-90 minutes. Symptoms include a burning sensation, conjunctival injection, rhinorrhea, and photosensitivity. Patients often have one to three of these headaches per day, and the headaches appear to be linked to the circadian rhythm. An episodic cluster cycle can last for weeks to months of daily or near daily attacks.

A study presented at the recent meeting of the American Academy of Neurology provided evidence of the drug’s efficacy in cluster headache. In this trial, researchers randomized 106 patients with episodic cluster headache to galcanezumab or placebo. The baseline cluster headache frequency was 17.3 attacks per week, and galcanezumab reduced this frequency to 9.1 attacks per week, compared with 12.1 attacks per week with placebo. The most common side effect reported in this and other clinical trials was injection-site reactions.

Galcanezumab entails a risk of hypersensitivity reactions, according to the FDA. These reactions may occur several days after administration and may be prolonged. “If a serious hypersensitivity reaction occurs, treatment should be discontinued,” the agency said.

“It’s a very exciting day. There had never been a drug approved for prevention of cluster headache,” said Stewart J. Tepper, MD, professor of neurology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and director of the Dartmouth Headache Center, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

It is difficult to achieve therapeutic concentrations of current preventive medications that do not have FDA approval for this indication, such as verapamil, lithium, or antiepileptic drugs. Galcanezumab, in contrast, works quickly. It is important to note that the approval was for preventive treatment of episodic cluster headache, not for prevention of chronic cluster headache, and not for acute treatment, Dr. Tepper said.

“It’s important to get optimal therapy for cluster headache. It is one of the most disabling, terrible disorders on Earth,” Dr. Tepper said. “The importance [of this approval] cannot be overestimated.”

When asked for comment, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, said “If this monoclonal antibody to the CGRP ligand works as well in real life as in the trial, it will be an important advance in the treatment of cluster headache.”

Prior to the approval of galcanezumab, noninvasive vagal nerve stimulation was approved in November 2018 for adjunctive use in the preventive treatment of cluster headache in adults.

The FDA granted the application for galcanezumab using a Priority Review and Breakthrough Therapy designation. The agency approved galcanezumab for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults in September 2018. The drug appears to have a similar safety profile in both patient populations. Eli Lilly, which is based in Indianapolis, Indiana, manufactures the drug.

This article was updated June 5, 2019.

Acroangiodermatitis of Mali and Stewart-Bluefarb Syndrome

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 56-year-old white man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, sleep apnea, bilateral knee replacement, and cataract removal presented to the emergency department with a worsening rash on the left posterior medial leg of 6 months’ duration. He reported associated redness and tenderness with the plaques as well as increased swelling and firmness of the leg. He was admitted to the hospital where the infectious disease team treated him with cefazolin for presumed cellulitis. His condition did not improve, and another course of cefazolin was started in addition to oral fluconazole and clotrimazole–betamethasone dipropionate lotion for a possible fungal cause. Again, treatment provided no improvement.

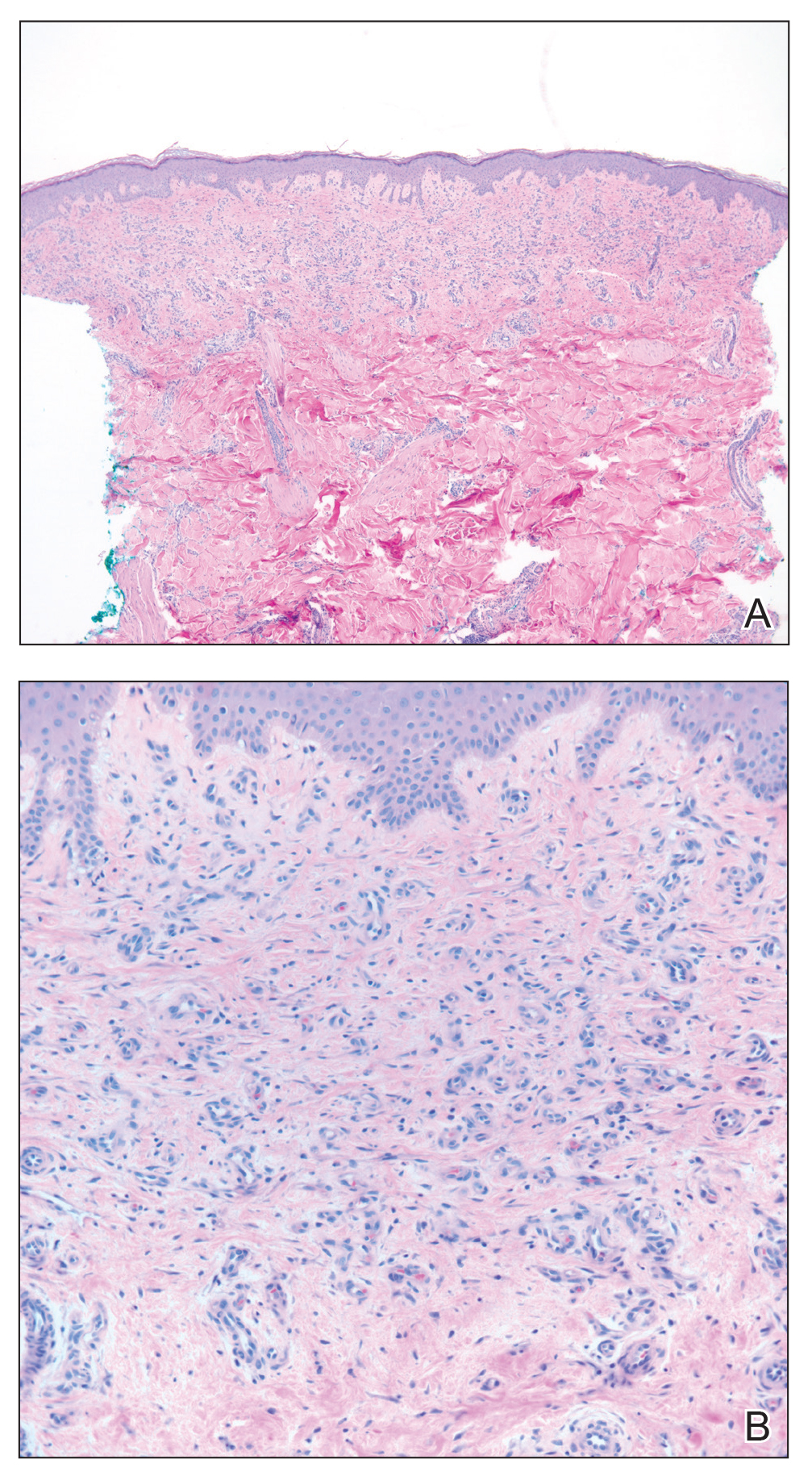

He was then evaluated by dermatology. On physical examination, the patient had edema, warmth, and induration of the left lower leg. There also was an annular and serpiginous indurated plaque with minimal scale on the left lower leg (Figure 1). A firm, dark red to purple plaque on the left medial thigh with mild scale was present. There also was scaling of the right plantar foot.

Skin biopsy revealed a dermal capillary proliferation with a scattering of inflammatory cells including eosinophils as well as dermal fibrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) immunostains were negative. Considering the degree and depth of vascular proliferation, Mali-type acroangiodermatitis (AAD) was the favored diagnosis.

Patient 2

A 72-year-old white man presented with a firm asymptomatic growth on the left dorsal forearm of 3 months’ duration. It was located near the site of a prior squamous cell carcinoma that was excised 1 year prior to presentation. The patient had no treatment or biopsy of the presenting lesion. His medical and surgical history included polycystic kidney disease and renal transplantation 4 years prior to presentation. He also had an arteriovenous fistula of the left arm. His other chronic diseases included chronic obstructive lung disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obstructive sleep apnea.

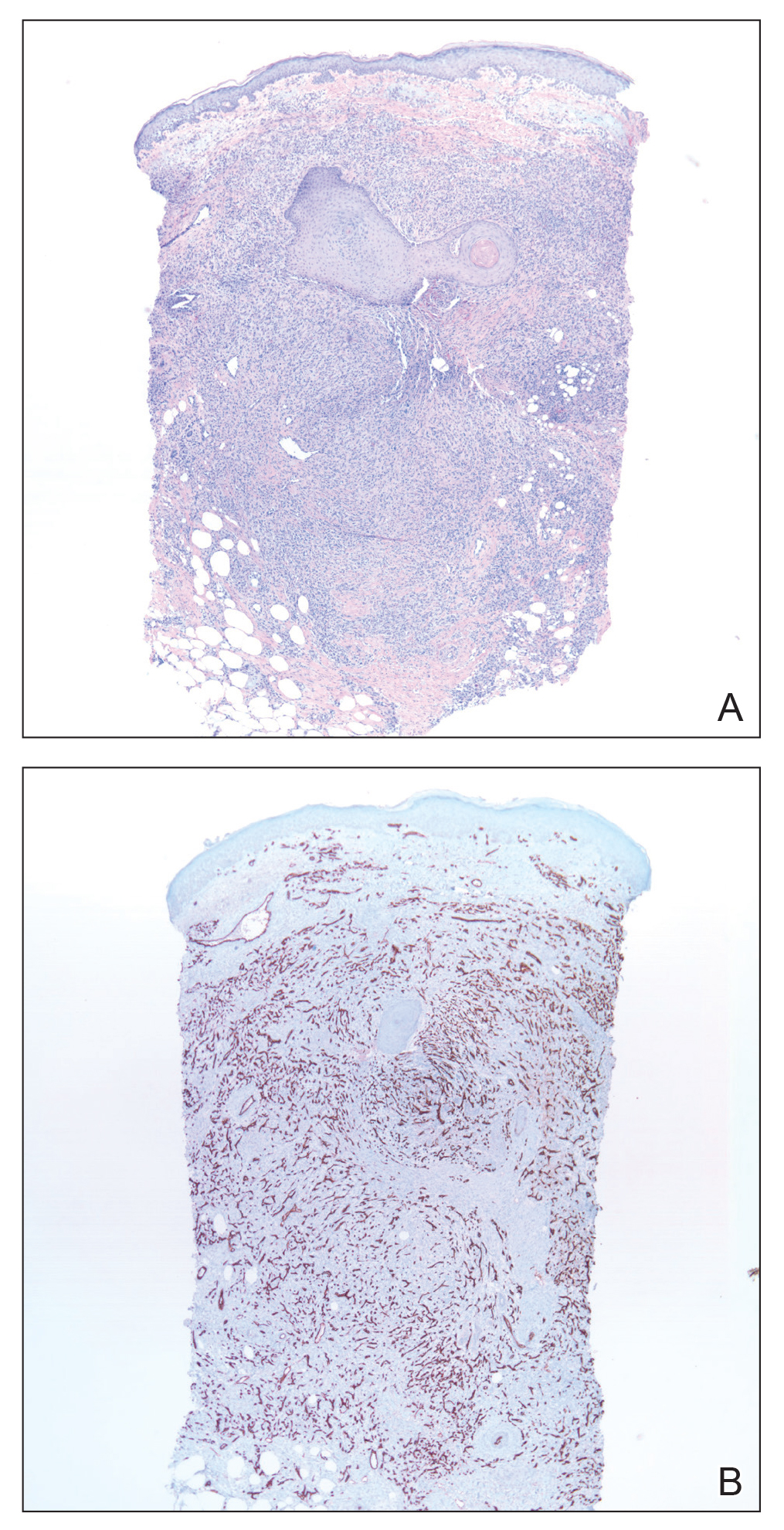

On physical examination, the patient had a 1-cm violaceous nodule on the extensor surface of the left mid forearm. An arteriovenous fistula was present proximal to the lesion on the left arm (Figure 3).

Skin biopsy revealed a tightly packed proliferation of small vascular channels that tested negative for HHV-8, tumor protein p63, and cytokeratin 5/6. Erythrocytes were noted in the lumen of some of these vessels. Neutrophils were scattered and clustered throughout the specimen (Figure 4A). Blood vessels were highlighted with CD34 (Figure 4B). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain was negative for infectious agents. These findings favored AAD secondary to an arteriovenous malformation, consistent with Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome (SBS).

Comment

Presentation of AAD

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare chronic inflammatory skin process involving a reactive proliferation of capillaries and fibrosis of the skin that resembles Kaposi sarcoma both clinically and histopathologically. The condition has been reported in patients with chronic venous insufficiency,1 congenital arteriovenous malformation,2 acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula,3 paralyzed extremity,4 suction socket lower limb prosthesis (amputees),5 and minor trauma.6-8 The lesions of AAD tend to be circumscribed, slowly evolving, red-violaceous (or brown or dusky) macules, papules, or plaques that may become verrucous or develop into painful ulcerations. They generally occur on the distal dorsal aspects of the lower legs and feet.110

Variants of AAD

Mali et al9 first reported cutaneous manifestations resembling Kaposi sarcoma in 18 patients with chronic venous insufficiency in 1965. Two years later, Bluefarb and Adams10 described kaposiform skin lesions in one patient with a congenital arteriovenous malformation without chronic venous insufficiency. It was not until 1974, however, that Earhart et al11 proposed the term pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma.10,11 Based on these findings, AAD is described as 2 variants: Mali type and SBS.

Mali-type AAD is more common and typically occurs in elderly men. It classically presents bilaterally on the lower extremities in association with severe chronic venous insufficiency.5 Skin lesions usually occur on the medial aspect of the lower legs (as in patient 1), dorsum of the heel, hallux, or second toe.12

The etiology of Mali-type AAD is poorly understood. The leading theory is that the condition involves reduced perfusion due to chronic edema, resulting in neovascularization, fibroblast proliferation, hypertrophy, and inflammatory skin changes. When AAD occurs in the setting of a suction socket prosthesis, the negative pressure of the stump-socket environment is thought to alter local circulation, leading to proliferation of small blood vessels.5,13

Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome usually involves a single extremity in young adults with congenital arteriovenous malformations, amputees, and individuals with hemiplegia or iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulae (as in patient 2).1 It was once thought to occur secondary to Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome; however, SBS rarely is accompanied by limb hypertrophy.9 Pathogenesis is thought to involve an angiogenic response to a high perfusion rate and high oxygen saturation, which leads to fibroblast proliferation and reactive endothelial hyperplasia.1,14

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Prompt identification of an underlying arteriovenous anomaly is critical, given the sequelae of high-flow shunts, which may result in skin ulceration, limb length discrepancy, cortical thinning of bone with regional osteoporosis, and congestive heart failure.1,5 Duplex ultrasonography is the first-line diagnostic modality because it is noninvasive and widely available. The key doppler feature of an arteriovenous malformation is low resistance and high diastolic pulsatile flow,1 which should be confirmed with magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomography angiography if present on ultrasonography.

The differential diagnosis of AAD includes Kaposi sarcoma, reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angiomatosis, intravascular histiocytosis, glomeruloid angioendotheliomatosis, and angiopericytomatosis.15,16 These entities present as multiple erythematous, violaceous, purpuric patches and plaques generally on the extremities but can have a widely varied distribution. Some lesions evolve to necrosis or ulceration. Histopathologic analysis is useful to differentiate these entities.

Histopathology

The histopathologic features of AAD can be nonspecific; clinicopathologic correlation often is necessary to establish the diagnosis. Features include a proliferation of small thick-walled vessels, often in a lobular arrangement, in an edematous papillary dermis. Small thrombi may be observed. There may be increased fibroblasts; plump endothelial cells; a superficial mixed infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils; and deposition of hemosiderin.2,5 These characteristics overlap with features of Kaposi sarcoma; AAD, however, lacks slitlike vascular spaces, perivascular CD34+ expression, and nuclear atypia. A negative HHV-8 stain will assist in ruling out Kaposi sarcoma.1,17

Management

Treatment reports are anecdotal. The goal is to correct underlying venous hypertension. Conservative measures with compression garments, intermittent pneumatic compression, and limb elevation are first line.18 Oral antibiotics and local wound care with topical emollients and corticosteroids have been shown to be effective treatments.19-21

Oral erythromycin 500 mg 4 times daily for 3 weeks and clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% healed a lower extremity ulcer in a patient with Mali-type AAD.21 In another patient, conservative treatment of Mali-type AAD failed, but rapid improvement of 2 lower extremity ulcers resulted after 3 weeks of oral dapsone 50 mg twice daily.22

Conclusion