User login

FDA announces clearance of modified endoscope connector

which was designed to reduce the risk of cross-contamination previously identified by the FDA.

The FDA approval of the modified ERBEFLO port connector is based on a review of the functional and simulated use testing of the modified device design. The effectiveness of the device at reducing the risk of backflow and contamination is also supported by simulated testing.

Revised labeling included with the product identifies compatible endoscopes and accessories and provides warnings to ensure proper usage.

“The clearance of the modified ERBEFLO 24-hour use port connector provides another option for health care facilities whose staff understand and can fully implement the instructions for use to reduce the risk of cross-contamination and infection,” the FDA said in the May 23 update letter.

AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology will continue to monitor this issue and encourages all GIs to follow the most up-to-date FDA guidance.

which was designed to reduce the risk of cross-contamination previously identified by the FDA.

The FDA approval of the modified ERBEFLO port connector is based on a review of the functional and simulated use testing of the modified device design. The effectiveness of the device at reducing the risk of backflow and contamination is also supported by simulated testing.

Revised labeling included with the product identifies compatible endoscopes and accessories and provides warnings to ensure proper usage.

“The clearance of the modified ERBEFLO 24-hour use port connector provides another option for health care facilities whose staff understand and can fully implement the instructions for use to reduce the risk of cross-contamination and infection,” the FDA said in the May 23 update letter.

AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology will continue to monitor this issue and encourages all GIs to follow the most up-to-date FDA guidance.

which was designed to reduce the risk of cross-contamination previously identified by the FDA.

The FDA approval of the modified ERBEFLO port connector is based on a review of the functional and simulated use testing of the modified device design. The effectiveness of the device at reducing the risk of backflow and contamination is also supported by simulated testing.

Revised labeling included with the product identifies compatible endoscopes and accessories and provides warnings to ensure proper usage.

“The clearance of the modified ERBEFLO 24-hour use port connector provides another option for health care facilities whose staff understand and can fully implement the instructions for use to reduce the risk of cross-contamination and infection,” the FDA said in the May 23 update letter.

AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology will continue to monitor this issue and encourages all GIs to follow the most up-to-date FDA guidance.

One versus two uterotonics: Which is better for minimizing postpartum blood loss?

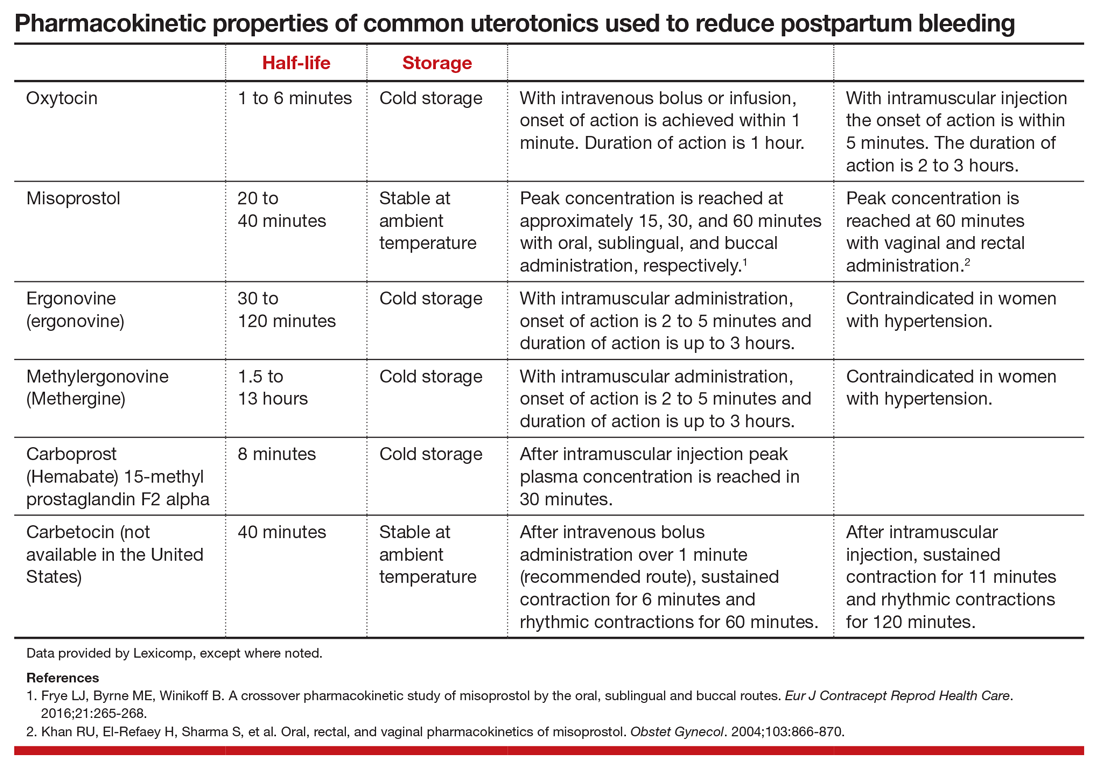

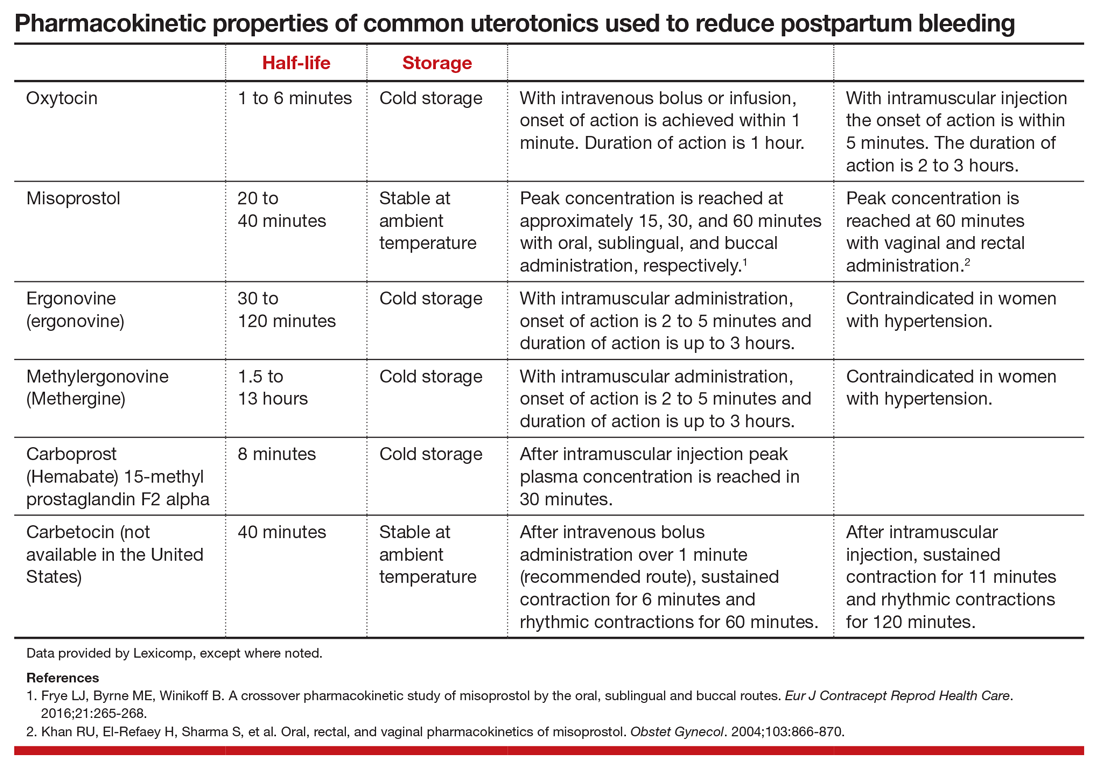

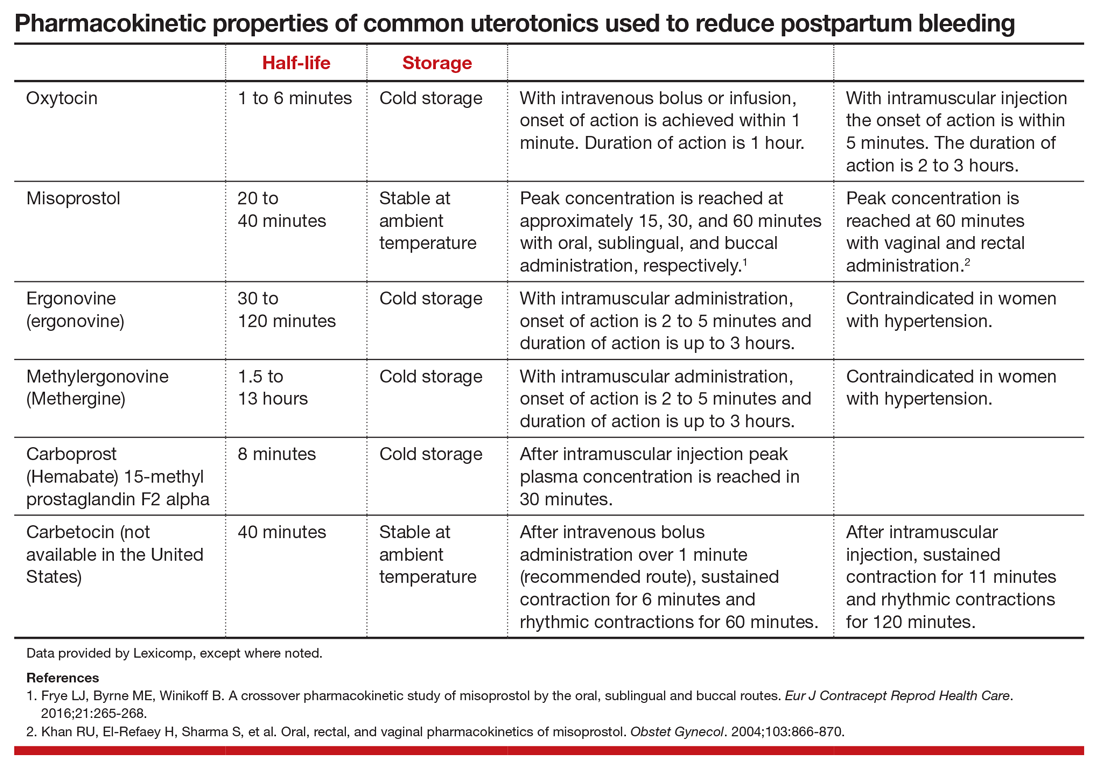

Excessive postpartum bleeding is a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Worldwide, obstetric hemorrhage is the most common cause of maternal death.1,2 Medications reported to reduce postpartum bleeding include oxytocin, misoprostol, ergonovine, methylergonovine, carboprost, and tranexamic acid. A recent Cochrane network meta-analysis of 196 trials, including 135,559 women, distilled in 1,361 pages of analysis, reported on the medications associated with the greatest reduction in postpartum bleeding.3 Surprisingly, for preventing blood loss ≥ 500 mL, misoprostol plus oxytocin and ergonovine plus oxytocin were the highest ranked interventions. This evidence is summarized here.

Misoprostol plus oxytocin

After newborn delivery, active management of the third stage of labor, including uterotonic administration, is strongly recommended because it will reduce postpartum blood loss, decreasing the rate of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH).4 Both oxytocin and misoprostol are effective uterotonics. However, the combination of oxytocin plus misoprostol appears to be more effective than oxytocin alone in reducing the frequency of postpartum blood loss greater than 500 mL.3 To understand the clinical efficacy and adverse effects (AEs) of combined oxytocin plus misoprostol a meta-analysis was performed for both vaginal and cesarean deliveries (CDs).

Efficacy and AEs during vaginal delivery. In the meta-analysis, about 6,000 vaginal deliveries were analyzed, with no significant differences for misoprostol plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone found for the following outcomes: maternal death, intensive care unit admissions, and rate of blood loss ≥ 1,000 mL (1.7% for both uterotonics vs 2.2% for oxytocin alone).3 Misoprostol plus oxytocin was significantly superior to oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: reduced risk of blood transfusion (0.95% vs 2.5%), reduced risk of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (5.9% vs 8.0%), reduced risk of requiring an additional uterotonic (3.6% vs 5.8%), and a smaller decrease in hemoglobin concentration from pre- to postdelivery (-0.89 g/L).3

In my opinion, the difference in hemoglobin concentration, although statistically significant, is not of clinical significance. However, compared with oxytocin alone, misoprostol plus oxytocin caused significantly more nausea (2.4% vs 0.66%), vomiting (3.1% vs 0.86%), and fever (21% vs 3.9%).3 A weakness of this meta-analysis is that the trials used a wide range of misoprostol dosages (200 to 600 µg) and multiple routes of administration, including sublingual (under the tongue), buccal, and rectal. This makes it impossible to identify a best misoprostol dosage and administration route.

Efficacy and AEs during CD. In the same meta-analysis about 2,000 CDs were analyzed, with no significant difference for misoprostol plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: maternal death, intensive care unit admissions, and PPH ≥ 1,000 mL blood loss (6.2% vs 6.5%).3 Misoprostol plus oxytocin was significantly superior to oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: reduced risk of blood transfusion (2.6% vs 5.4%), reduced risk of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (32% vs 47%), reduced risk of requiring an additional uterotonic (14% vs 28%), and a smaller decrease in hemoglobin concentration from before to after delivery (-4.0 g/L).3 In my opinion, the statistically significant difference in hemoglobin concentration is not clinically significant. However, compared with oxytocin alone, misoprostol plus oxytocin caused significantly more nausea (12% vs 6.1%), vomiting (8.1% vs 5.4%), shivering (13% vs 7%), and fever (7.7% vs 4.0%).3

Continue to: Ergonovine plus oxytocin...

Ergonovine plus oxytocin

Ergonovine is an ergot derivative that causes uterine contractions and has been shown to effectively reduce blood loss at delivery. In the United States a methyl-derivative of ergonovine, methylergonovine, is widely available. In a meta-analysis with mostly vaginal deliveries, there were no significant differences for ergonovine plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: death, intensive care unit admission, rate of blood loss ≥ 1,000 mL(2.0% vs 2.7%), blood transfusion, administration of an additional uterotonic, change in hemoglobin from pre- to postdelivery, nausea, hypertension, shivering, and fever.3 However, ergonovine plus oxytocin, compared with oxytocin alone, resulted in a significantly reduced rate of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (8.3% vs 10.2%) and an increased rate of vomiting (8.1% vs 1.6%).3 In these trials women with a blood pressure ≥ 150/100 mm Hg were generally excluded from receiving ergonovine because of its hypertensive effect.

Clinical practice options

Given the Cochrane meta-analysis results, ObGyns have two approaches for optimizing PPH reduction.

Option 1: Use a single uterotonic to reduce postpartum blood loss. If excess bleeding occurs, rapidly administer a second uterotonic agent. Currently, monotherapy with intravenous or intramuscular oxytocin is the standard for reducing postpartum blood loss.5,6 Advantages of this approach compared with dual agent therapy include simplification of care and minimization of AEs. However, oxytocin monotherapy for minimizing postpartum bleeding may be suboptimal. In the largest trial ever performed (involving 29,645 women) when oxytocin was administered postpartum, the rates of estimated blood loss ≥ 500 mL and ≥ 1,000 mL were 9.1% and 1.45%, respectively.5 Is 9% an optimal rate for blood loss ≥ 500 mL following a vaginal delivery? Or should we try to achieve a lower rate?

Given the “high” rate of blood loss ≥ 500 mL with oxytocin alone, it is important for clinicians using the one-uterotonic approach to promptly recognize patients who have excessive bleeding and transition rapidly from prevention to treatment. When PPH cases are reviewed, a common finding is that the clinicians did not timely recognize excess bleeding, delaying transition to treatment with additional uterotonics and other interventions. When routinely using oxytocin monotherapy, lowering the threshold for administering a second uterotonic (methylergonovine, carboprost, misoprostol, or tranexamic acid) may help decrease the frequency of excess postpartum blood loss.

Option 2: Administer two uterotonics to reduce postpartum blood loss at all deliveries. Given the “high” rate of excess postpartum blood loss with oxytocin monotherapy, an alternative is to administer two uterotonics at all births or at births with a high risk of excess blood loss. As discussed, administering two uterotonics, oxytocin plus misoprostol or oxytocin plus ergonovine, has been reported to be more effective than oxytocin alone for reducing postpartum bleeding ≥ 500 mL.3 In the Cochrane meta-analysis, per 1,000 women given oxytocin following a vaginal birth, 122 would have blood loss ≥ 500 mL, compared with 85 given oxytocin plus misoprostol or oxytocin plus ergonovine.3

Misoprostol is administered sublingually, buccally, or rectally, and methylergonovine is administered by intramuscular injection. Although dual uterotonic therapy is more effective than monotherapy, dual therapy is associated with more AEs. As noted, compared with oxytocin monotherapy, the combination of oxytocin plus misoprostol is associated with more nausea, vomiting, shivering, and fever. Oxytocin plus ergonovine is associated with a higher rate of vomiting than oxytocin monotherapy. In my practice I prefer using intramuscular methylergonovine as the second agent to avoid the high rate of fever associated with misoprostol.

For dual agent therapy, one approach is to administer misoprostol 200 µg or 400 µg through the buccal7,8 or sublingual9,10 routes. Higher dosages of misoprostol (600 µg to 800 µg) have been used11,12 but are likely associated with higher rates of nausea, vomiting,shivering, and fever than the lower dosages. Methylergonovine 0.2 mg is administered intramuscularly.

Continue to: The bottom line...

The bottom line

PPH is a major cause of maternal morbidity, and in low-resource settings, mortality. Oxytocin is the standard for reducing postpartum blood loss, but rates of blood loss ≥ 500 mL are high following this monotherapy. To reduce postpartum blood loss beyond what is possible with oxytocin alone, clinicians can more rapidly transition to administering a second uterotonic when they suspect blood loss is becoming excessive or they can use two uterotonic agents with all births or in those at high risk for excess bleeding. If blood loss does become excessive, clinicians need to pivot rapidly from prevention with oxytocin to treatment with our entire therapeutic armamentarium.

- Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e323-e333.

- Slomski A. Why do hundreds of US women die annually in childbirth? JAMA. 2019;321:1239-1241.

- Gallos ID, Papadopoulou A, Man R, et al. Uterotonic agents for preventing postpartum haemorrhage: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD011689.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e168-e186.

- Widmer M, Piaggio G, Nguyen TM, et al; WHO Champion Trial Group. Heat-stable carbetocin versus oxytocin to prevent hemorrhage after vaginal birth. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:743-752.

- Adnan N, Conlan-Trant R, McCormick C, et al. Intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin to prevent postpartum haemorrhage at vaginal delivery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2018;362:k3546.

- Hamm J, Russell Z, Botha T, et al. Buccal misoprostol to prevent hemorrhage at cesarean delivery: a randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1404-1406.

- Bhullar A, Carlan SJ, Hamm J, et al. Buccal misoprostol to decrease blood loss after vaginal delivery: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1282-1288.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Fawole B, Mugerwa K, et al. Administration of 400 µg of misoprostol to augment routine active management of the third stage of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;112:98-102.

- Chaudhuri P, Majumdar A. A randomized trial of sublingual misoprostol to augment routine third-stage management among women at risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;132:191-195.

- Winikoff B, Dabash R, Durocher J, et al. Treatment of post-partum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin in women not exposed to oxytocin during labor: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375:210-216.

- Blum J, Winikoff B, Raghavan S, et al. Treatment of post-partum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin in women receiving prophylactic oxytocin: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375:217-223.

Excessive postpartum bleeding is a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Worldwide, obstetric hemorrhage is the most common cause of maternal death.1,2 Medications reported to reduce postpartum bleeding include oxytocin, misoprostol, ergonovine, methylergonovine, carboprost, and tranexamic acid. A recent Cochrane network meta-analysis of 196 trials, including 135,559 women, distilled in 1,361 pages of analysis, reported on the medications associated with the greatest reduction in postpartum bleeding.3 Surprisingly, for preventing blood loss ≥ 500 mL, misoprostol plus oxytocin and ergonovine plus oxytocin were the highest ranked interventions. This evidence is summarized here.

Misoprostol plus oxytocin

After newborn delivery, active management of the third stage of labor, including uterotonic administration, is strongly recommended because it will reduce postpartum blood loss, decreasing the rate of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH).4 Both oxytocin and misoprostol are effective uterotonics. However, the combination of oxytocin plus misoprostol appears to be more effective than oxytocin alone in reducing the frequency of postpartum blood loss greater than 500 mL.3 To understand the clinical efficacy and adverse effects (AEs) of combined oxytocin plus misoprostol a meta-analysis was performed for both vaginal and cesarean deliveries (CDs).

Efficacy and AEs during vaginal delivery. In the meta-analysis, about 6,000 vaginal deliveries were analyzed, with no significant differences for misoprostol plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone found for the following outcomes: maternal death, intensive care unit admissions, and rate of blood loss ≥ 1,000 mL (1.7% for both uterotonics vs 2.2% for oxytocin alone).3 Misoprostol plus oxytocin was significantly superior to oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: reduced risk of blood transfusion (0.95% vs 2.5%), reduced risk of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (5.9% vs 8.0%), reduced risk of requiring an additional uterotonic (3.6% vs 5.8%), and a smaller decrease in hemoglobin concentration from pre- to postdelivery (-0.89 g/L).3

In my opinion, the difference in hemoglobin concentration, although statistically significant, is not of clinical significance. However, compared with oxytocin alone, misoprostol plus oxytocin caused significantly more nausea (2.4% vs 0.66%), vomiting (3.1% vs 0.86%), and fever (21% vs 3.9%).3 A weakness of this meta-analysis is that the trials used a wide range of misoprostol dosages (200 to 600 µg) and multiple routes of administration, including sublingual (under the tongue), buccal, and rectal. This makes it impossible to identify a best misoprostol dosage and administration route.

Efficacy and AEs during CD. In the same meta-analysis about 2,000 CDs were analyzed, with no significant difference for misoprostol plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: maternal death, intensive care unit admissions, and PPH ≥ 1,000 mL blood loss (6.2% vs 6.5%).3 Misoprostol plus oxytocin was significantly superior to oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: reduced risk of blood transfusion (2.6% vs 5.4%), reduced risk of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (32% vs 47%), reduced risk of requiring an additional uterotonic (14% vs 28%), and a smaller decrease in hemoglobin concentration from before to after delivery (-4.0 g/L).3 In my opinion, the statistically significant difference in hemoglobin concentration is not clinically significant. However, compared with oxytocin alone, misoprostol plus oxytocin caused significantly more nausea (12% vs 6.1%), vomiting (8.1% vs 5.4%), shivering (13% vs 7%), and fever (7.7% vs 4.0%).3

Continue to: Ergonovine plus oxytocin...

Ergonovine plus oxytocin

Ergonovine is an ergot derivative that causes uterine contractions and has been shown to effectively reduce blood loss at delivery. In the United States a methyl-derivative of ergonovine, methylergonovine, is widely available. In a meta-analysis with mostly vaginal deliveries, there were no significant differences for ergonovine plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: death, intensive care unit admission, rate of blood loss ≥ 1,000 mL(2.0% vs 2.7%), blood transfusion, administration of an additional uterotonic, change in hemoglobin from pre- to postdelivery, nausea, hypertension, shivering, and fever.3 However, ergonovine plus oxytocin, compared with oxytocin alone, resulted in a significantly reduced rate of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (8.3% vs 10.2%) and an increased rate of vomiting (8.1% vs 1.6%).3 In these trials women with a blood pressure ≥ 150/100 mm Hg were generally excluded from receiving ergonovine because of its hypertensive effect.

Clinical practice options

Given the Cochrane meta-analysis results, ObGyns have two approaches for optimizing PPH reduction.

Option 1: Use a single uterotonic to reduce postpartum blood loss. If excess bleeding occurs, rapidly administer a second uterotonic agent. Currently, monotherapy with intravenous or intramuscular oxytocin is the standard for reducing postpartum blood loss.5,6 Advantages of this approach compared with dual agent therapy include simplification of care and minimization of AEs. However, oxytocin monotherapy for minimizing postpartum bleeding may be suboptimal. In the largest trial ever performed (involving 29,645 women) when oxytocin was administered postpartum, the rates of estimated blood loss ≥ 500 mL and ≥ 1,000 mL were 9.1% and 1.45%, respectively.5 Is 9% an optimal rate for blood loss ≥ 500 mL following a vaginal delivery? Or should we try to achieve a lower rate?

Given the “high” rate of blood loss ≥ 500 mL with oxytocin alone, it is important for clinicians using the one-uterotonic approach to promptly recognize patients who have excessive bleeding and transition rapidly from prevention to treatment. When PPH cases are reviewed, a common finding is that the clinicians did not timely recognize excess bleeding, delaying transition to treatment with additional uterotonics and other interventions. When routinely using oxytocin monotherapy, lowering the threshold for administering a second uterotonic (methylergonovine, carboprost, misoprostol, or tranexamic acid) may help decrease the frequency of excess postpartum blood loss.

Option 2: Administer two uterotonics to reduce postpartum blood loss at all deliveries. Given the “high” rate of excess postpartum blood loss with oxytocin monotherapy, an alternative is to administer two uterotonics at all births or at births with a high risk of excess blood loss. As discussed, administering two uterotonics, oxytocin plus misoprostol or oxytocin plus ergonovine, has been reported to be more effective than oxytocin alone for reducing postpartum bleeding ≥ 500 mL.3 In the Cochrane meta-analysis, per 1,000 women given oxytocin following a vaginal birth, 122 would have blood loss ≥ 500 mL, compared with 85 given oxytocin plus misoprostol or oxytocin plus ergonovine.3

Misoprostol is administered sublingually, buccally, or rectally, and methylergonovine is administered by intramuscular injection. Although dual uterotonic therapy is more effective than monotherapy, dual therapy is associated with more AEs. As noted, compared with oxytocin monotherapy, the combination of oxytocin plus misoprostol is associated with more nausea, vomiting, shivering, and fever. Oxytocin plus ergonovine is associated with a higher rate of vomiting than oxytocin monotherapy. In my practice I prefer using intramuscular methylergonovine as the second agent to avoid the high rate of fever associated with misoprostol.

For dual agent therapy, one approach is to administer misoprostol 200 µg or 400 µg through the buccal7,8 or sublingual9,10 routes. Higher dosages of misoprostol (600 µg to 800 µg) have been used11,12 but are likely associated with higher rates of nausea, vomiting,shivering, and fever than the lower dosages. Methylergonovine 0.2 mg is administered intramuscularly.

Continue to: The bottom line...

The bottom line

PPH is a major cause of maternal morbidity, and in low-resource settings, mortality. Oxytocin is the standard for reducing postpartum blood loss, but rates of blood loss ≥ 500 mL are high following this monotherapy. To reduce postpartum blood loss beyond what is possible with oxytocin alone, clinicians can more rapidly transition to administering a second uterotonic when they suspect blood loss is becoming excessive or they can use two uterotonic agents with all births or in those at high risk for excess bleeding. If blood loss does become excessive, clinicians need to pivot rapidly from prevention with oxytocin to treatment with our entire therapeutic armamentarium.

Excessive postpartum bleeding is a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Worldwide, obstetric hemorrhage is the most common cause of maternal death.1,2 Medications reported to reduce postpartum bleeding include oxytocin, misoprostol, ergonovine, methylergonovine, carboprost, and tranexamic acid. A recent Cochrane network meta-analysis of 196 trials, including 135,559 women, distilled in 1,361 pages of analysis, reported on the medications associated with the greatest reduction in postpartum bleeding.3 Surprisingly, for preventing blood loss ≥ 500 mL, misoprostol plus oxytocin and ergonovine plus oxytocin were the highest ranked interventions. This evidence is summarized here.

Misoprostol plus oxytocin

After newborn delivery, active management of the third stage of labor, including uterotonic administration, is strongly recommended because it will reduce postpartum blood loss, decreasing the rate of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH).4 Both oxytocin and misoprostol are effective uterotonics. However, the combination of oxytocin plus misoprostol appears to be more effective than oxytocin alone in reducing the frequency of postpartum blood loss greater than 500 mL.3 To understand the clinical efficacy and adverse effects (AEs) of combined oxytocin plus misoprostol a meta-analysis was performed for both vaginal and cesarean deliveries (CDs).

Efficacy and AEs during vaginal delivery. In the meta-analysis, about 6,000 vaginal deliveries were analyzed, with no significant differences for misoprostol plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone found for the following outcomes: maternal death, intensive care unit admissions, and rate of blood loss ≥ 1,000 mL (1.7% for both uterotonics vs 2.2% for oxytocin alone).3 Misoprostol plus oxytocin was significantly superior to oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: reduced risk of blood transfusion (0.95% vs 2.5%), reduced risk of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (5.9% vs 8.0%), reduced risk of requiring an additional uterotonic (3.6% vs 5.8%), and a smaller decrease in hemoglobin concentration from pre- to postdelivery (-0.89 g/L).3

In my opinion, the difference in hemoglobin concentration, although statistically significant, is not of clinical significance. However, compared with oxytocin alone, misoprostol plus oxytocin caused significantly more nausea (2.4% vs 0.66%), vomiting (3.1% vs 0.86%), and fever (21% vs 3.9%).3 A weakness of this meta-analysis is that the trials used a wide range of misoprostol dosages (200 to 600 µg) and multiple routes of administration, including sublingual (under the tongue), buccal, and rectal. This makes it impossible to identify a best misoprostol dosage and administration route.

Efficacy and AEs during CD. In the same meta-analysis about 2,000 CDs were analyzed, with no significant difference for misoprostol plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: maternal death, intensive care unit admissions, and PPH ≥ 1,000 mL blood loss (6.2% vs 6.5%).3 Misoprostol plus oxytocin was significantly superior to oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: reduced risk of blood transfusion (2.6% vs 5.4%), reduced risk of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (32% vs 47%), reduced risk of requiring an additional uterotonic (14% vs 28%), and a smaller decrease in hemoglobin concentration from before to after delivery (-4.0 g/L).3 In my opinion, the statistically significant difference in hemoglobin concentration is not clinically significant. However, compared with oxytocin alone, misoprostol plus oxytocin caused significantly more nausea (12% vs 6.1%), vomiting (8.1% vs 5.4%), shivering (13% vs 7%), and fever (7.7% vs 4.0%).3

Continue to: Ergonovine plus oxytocin...

Ergonovine plus oxytocin

Ergonovine is an ergot derivative that causes uterine contractions and has been shown to effectively reduce blood loss at delivery. In the United States a methyl-derivative of ergonovine, methylergonovine, is widely available. In a meta-analysis with mostly vaginal deliveries, there were no significant differences for ergonovine plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: death, intensive care unit admission, rate of blood loss ≥ 1,000 mL(2.0% vs 2.7%), blood transfusion, administration of an additional uterotonic, change in hemoglobin from pre- to postdelivery, nausea, hypertension, shivering, and fever.3 However, ergonovine plus oxytocin, compared with oxytocin alone, resulted in a significantly reduced rate of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (8.3% vs 10.2%) and an increased rate of vomiting (8.1% vs 1.6%).3 In these trials women with a blood pressure ≥ 150/100 mm Hg were generally excluded from receiving ergonovine because of its hypertensive effect.

Clinical practice options

Given the Cochrane meta-analysis results, ObGyns have two approaches for optimizing PPH reduction.

Option 1: Use a single uterotonic to reduce postpartum blood loss. If excess bleeding occurs, rapidly administer a second uterotonic agent. Currently, monotherapy with intravenous or intramuscular oxytocin is the standard for reducing postpartum blood loss.5,6 Advantages of this approach compared with dual agent therapy include simplification of care and minimization of AEs. However, oxytocin monotherapy for minimizing postpartum bleeding may be suboptimal. In the largest trial ever performed (involving 29,645 women) when oxytocin was administered postpartum, the rates of estimated blood loss ≥ 500 mL and ≥ 1,000 mL were 9.1% and 1.45%, respectively.5 Is 9% an optimal rate for blood loss ≥ 500 mL following a vaginal delivery? Or should we try to achieve a lower rate?

Given the “high” rate of blood loss ≥ 500 mL with oxytocin alone, it is important for clinicians using the one-uterotonic approach to promptly recognize patients who have excessive bleeding and transition rapidly from prevention to treatment. When PPH cases are reviewed, a common finding is that the clinicians did not timely recognize excess bleeding, delaying transition to treatment with additional uterotonics and other interventions. When routinely using oxytocin monotherapy, lowering the threshold for administering a second uterotonic (methylergonovine, carboprost, misoprostol, or tranexamic acid) may help decrease the frequency of excess postpartum blood loss.

Option 2: Administer two uterotonics to reduce postpartum blood loss at all deliveries. Given the “high” rate of excess postpartum blood loss with oxytocin monotherapy, an alternative is to administer two uterotonics at all births or at births with a high risk of excess blood loss. As discussed, administering two uterotonics, oxytocin plus misoprostol or oxytocin plus ergonovine, has been reported to be more effective than oxytocin alone for reducing postpartum bleeding ≥ 500 mL.3 In the Cochrane meta-analysis, per 1,000 women given oxytocin following a vaginal birth, 122 would have blood loss ≥ 500 mL, compared with 85 given oxytocin plus misoprostol or oxytocin plus ergonovine.3

Misoprostol is administered sublingually, buccally, or rectally, and methylergonovine is administered by intramuscular injection. Although dual uterotonic therapy is more effective than monotherapy, dual therapy is associated with more AEs. As noted, compared with oxytocin monotherapy, the combination of oxytocin plus misoprostol is associated with more nausea, vomiting, shivering, and fever. Oxytocin plus ergonovine is associated with a higher rate of vomiting than oxytocin monotherapy. In my practice I prefer using intramuscular methylergonovine as the second agent to avoid the high rate of fever associated with misoprostol.

For dual agent therapy, one approach is to administer misoprostol 200 µg or 400 µg through the buccal7,8 or sublingual9,10 routes. Higher dosages of misoprostol (600 µg to 800 µg) have been used11,12 but are likely associated with higher rates of nausea, vomiting,shivering, and fever than the lower dosages. Methylergonovine 0.2 mg is administered intramuscularly.

Continue to: The bottom line...

The bottom line

PPH is a major cause of maternal morbidity, and in low-resource settings, mortality. Oxytocin is the standard for reducing postpartum blood loss, but rates of blood loss ≥ 500 mL are high following this monotherapy. To reduce postpartum blood loss beyond what is possible with oxytocin alone, clinicians can more rapidly transition to administering a second uterotonic when they suspect blood loss is becoming excessive or they can use two uterotonic agents with all births or in those at high risk for excess bleeding. If blood loss does become excessive, clinicians need to pivot rapidly from prevention with oxytocin to treatment with our entire therapeutic armamentarium.

- Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e323-e333.

- Slomski A. Why do hundreds of US women die annually in childbirth? JAMA. 2019;321:1239-1241.

- Gallos ID, Papadopoulou A, Man R, et al. Uterotonic agents for preventing postpartum haemorrhage: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD011689.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e168-e186.

- Widmer M, Piaggio G, Nguyen TM, et al; WHO Champion Trial Group. Heat-stable carbetocin versus oxytocin to prevent hemorrhage after vaginal birth. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:743-752.

- Adnan N, Conlan-Trant R, McCormick C, et al. Intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin to prevent postpartum haemorrhage at vaginal delivery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2018;362:k3546.

- Hamm J, Russell Z, Botha T, et al. Buccal misoprostol to prevent hemorrhage at cesarean delivery: a randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1404-1406.

- Bhullar A, Carlan SJ, Hamm J, et al. Buccal misoprostol to decrease blood loss after vaginal delivery: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1282-1288.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Fawole B, Mugerwa K, et al. Administration of 400 µg of misoprostol to augment routine active management of the third stage of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;112:98-102.

- Chaudhuri P, Majumdar A. A randomized trial of sublingual misoprostol to augment routine third-stage management among women at risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;132:191-195.

- Winikoff B, Dabash R, Durocher J, et al. Treatment of post-partum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin in women not exposed to oxytocin during labor: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375:210-216.

- Blum J, Winikoff B, Raghavan S, et al. Treatment of post-partum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin in women receiving prophylactic oxytocin: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375:217-223.

- Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e323-e333.

- Slomski A. Why do hundreds of US women die annually in childbirth? JAMA. 2019;321:1239-1241.

- Gallos ID, Papadopoulou A, Man R, et al. Uterotonic agents for preventing postpartum haemorrhage: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD011689.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e168-e186.

- Widmer M, Piaggio G, Nguyen TM, et al; WHO Champion Trial Group. Heat-stable carbetocin versus oxytocin to prevent hemorrhage after vaginal birth. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:743-752.

- Adnan N, Conlan-Trant R, McCormick C, et al. Intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin to prevent postpartum haemorrhage at vaginal delivery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2018;362:k3546.

- Hamm J, Russell Z, Botha T, et al. Buccal misoprostol to prevent hemorrhage at cesarean delivery: a randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1404-1406.

- Bhullar A, Carlan SJ, Hamm J, et al. Buccal misoprostol to decrease blood loss after vaginal delivery: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1282-1288.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Fawole B, Mugerwa K, et al. Administration of 400 µg of misoprostol to augment routine active management of the third stage of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;112:98-102.

- Chaudhuri P, Majumdar A. A randomized trial of sublingual misoprostol to augment routine third-stage management among women at risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;132:191-195.

- Winikoff B, Dabash R, Durocher J, et al. Treatment of post-partum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin in women not exposed to oxytocin during labor: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375:210-216.

- Blum J, Winikoff B, Raghavan S, et al. Treatment of post-partum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin in women receiving prophylactic oxytocin: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375:217-223.

Pustular Tinea Id Reaction

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a tender pruritic rash on the left wrist that was spreading to the bilateral arms and legs of several years’ duration. An area of a prior biopsy on the left wrist was healing well with use of petroleum jelly and halcinonide cream. The patient denied any constitutional symptoms.

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous papules coalescing into plaques on the bilateral anterior and posterior arms and legs, including some erythematous macules and papules on the palms and soles. The original area of involvement on the left dorsal medial wrist demonstrated a background of erythema with overlying peripheral scaling and resolving violaceous to erythematous papules with signs of serosanguineous crusting (Figure 1). Scattered perifollicular erythema was present on the posterior aspects of the bilateral thighs and arms (Figure 2). Baseline complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel were within reference range.

Clinical histopathology showed evidence of a pustular superficial dermatophyte infection, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated numerous fungal hyphae within subcorneal pustules, indicating pustular tinea. Based on the clinicopathologic correlation, the initial presentation was diagnosed as pustular tinea of the entire left wrist, followed by a generalized id reaction 1 week later.

The patient was prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily to treat the diffuse involvement of the pustular tinea as well as once-daily oral cetirizine, once-daily oral diphenhydramine, a topical emollient, and a topical nonsteroidal antipruritic gel.

Tinea is a superficial fungal infection commonly caused by the dermatophytes Epidermophyton, Trichophyton, and Microsporum. It has a variety of clinical presentations based on the anatomic location, including tinea capitis (hair/scalp), tinea pedis (feet), tinea corporis (face/trunk/extremities), tinea cruris (groin), and tinea unguium (nails).1 Tinea infections occur in the stratum corneum, hair, and nails, thriving on dead keratin in these areas.2 Tinea corporis usually appears as an erythematous ring-shaped lesion with a scaly border, but atypical cases presenting with vesicles, pustules, and bullae also have been reported.3 Additionally, secondary eruptions called id reactions, or autoeczematization, can present in the setting of dermatophyte infections. Such outbreaks may be due to a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the fungal antigens. Id reactions can manifest in many forms of tinea with patients generally exhibiting pruritic papulovesicular lesions that can present far from the site of origin.4

Patients with id reactions can have atypical and varied presentations. In a case of id reaction due to tinea corporis, a patient presented with vesicles and pustules that grew in number and coalesced to form annular lesions.5 A case of an id reaction caused by tinea pedis also noted the presence of pustules, which are atypical in this form of tinea.6 In another case of tinea pedis, a generalized id reaction was noted, illustrating that such eruptions do not necessarily appear at the original site of infection.7 Additionally, in a rare presentation of tinea invading the nares, a patient developed an erythema multiforme id reaction.8 Id reactions also were noted in 14 patients with refractory otitis externa, illustrating the ability of this fungal infection to persist and infect distant locations.9

Because the differential diagnoses for tinea infection are extensive, pathology or laboratory confirmation is necessary for diagnosis, and potassium hydroxide preparation often is used to diagnose dermatophyte infections.1,2 Additionally, the possibility of a hypersensitivity drug rash should remain in the differential if the patient received allergy-inducing medications prior to the outbreak, which may in turn complicate the diagnosis.

Tinea infections typically can be treated with topical antifungals such as terbinafine, butenafine,1 and luliconazole10; however, more involved cases may require oral antifungal treatment.1 Systemic treatment of tinea corporis includes itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole,11 all of which exhibit fewer side effects and greater efficacy when compared to griseofulvin.12-15

Treatment of id reactions centers on the proper clearance of the dermatophyte infection, and treatment with oral antifungals generally is sufficient. In the cases of id reaction in patients with refractory otitis, some success was achieved with treatment involving immunotherapy with dermatophyte and dust mite allergen extracts coupled with a yeast elimination diet.9 In acute id reactions, topical corticosteroids and antipruritic agents can be applied.4 Rarely, systemic glucocorticoids are required, such as in cases in which the id reaction persists despite proper treatment of the primary infection.16

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury Stone M. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:702-710.

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Hanover, NH: Elsevier, Inc; 2010.

- Ziemer M, Seyfarth F, Elsner P, et al. Atypical manifestations of tinea corporis. Mycoses. 2007;50(suppl 2):31-35.

- Cheng N, Rucker Wright D, Cohen BA. Dermatophytid in tinea capitis: rarely reported common phenomenon with clinical implications [published online July 4, 2011]. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e453-e457.

- Ohno S, Tanabe H, Kawasaki M, et al. Tinea corporis with acute inflammation caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. J Dermatol. 2008;35:590-593.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Pustular tinea pedis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:132-133.

- Iglesias ME, España A, Idoate MA, et al. Generalized skin reaction following tinea pedis (dermatophytids). J Dermatol. 1994;21:31-34.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste M. Erythema multiforme ID reaction in atypical dermatophytosis: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:699-701.

- Derebery J, Berliner KI. Foot and ear disease—the dermatophytid reaction in otology. Laryngoscope. 1996;106(2 Pt 1):181-186.

- Khanna D, Bharti S. Luliconazole for the treatment of fungal infections: an evidence-based review. Core Evid. 2014;9:113-124.

- Korting HC, Schöllmann C. The significance of itraconazole for treatment of fungal infections of skin, nails and mucous membranes. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:11-20.

- Goldstein AO, Goldstein BG. Dermatophyte (tinea) infections. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatophyte-tinea-infections. Updated December 28, 2018. Accessed April 24, 2019.

- Cole GW, Stricklin G. A comparison of a new oral antifungal, terbinafine, with griseofulvin as therapy for tinea corporis. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1537.

- Panagiotidou D, Kousidou T, Chaidemenos G, et al. A comparison of itraconazole and griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris: a double-blind study. J Int Med Res. 1992;20:392-400.

- Faergemann J, Mörk NJ, Haglund A, et al. A multicentre (double-blind) comparative study to assess the safety and efficacy of fluconazole and griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:575-577.

- Ilkit M, Durdu M, Karakas M. Cutaneous id reactions: a comprehensive review of clinical manifestations, epidemiology, etiology, and management. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2012;38:191-202.

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a tender pruritic rash on the left wrist that was spreading to the bilateral arms and legs of several years’ duration. An area of a prior biopsy on the left wrist was healing well with use of petroleum jelly and halcinonide cream. The patient denied any constitutional symptoms.

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous papules coalescing into plaques on the bilateral anterior and posterior arms and legs, including some erythematous macules and papules on the palms and soles. The original area of involvement on the left dorsal medial wrist demonstrated a background of erythema with overlying peripheral scaling and resolving violaceous to erythematous papules with signs of serosanguineous crusting (Figure 1). Scattered perifollicular erythema was present on the posterior aspects of the bilateral thighs and arms (Figure 2). Baseline complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel were within reference range.

Clinical histopathology showed evidence of a pustular superficial dermatophyte infection, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated numerous fungal hyphae within subcorneal pustules, indicating pustular tinea. Based on the clinicopathologic correlation, the initial presentation was diagnosed as pustular tinea of the entire left wrist, followed by a generalized id reaction 1 week later.

The patient was prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily to treat the diffuse involvement of the pustular tinea as well as once-daily oral cetirizine, once-daily oral diphenhydramine, a topical emollient, and a topical nonsteroidal antipruritic gel.

Tinea is a superficial fungal infection commonly caused by the dermatophytes Epidermophyton, Trichophyton, and Microsporum. It has a variety of clinical presentations based on the anatomic location, including tinea capitis (hair/scalp), tinea pedis (feet), tinea corporis (face/trunk/extremities), tinea cruris (groin), and tinea unguium (nails).1 Tinea infections occur in the stratum corneum, hair, and nails, thriving on dead keratin in these areas.2 Tinea corporis usually appears as an erythematous ring-shaped lesion with a scaly border, but atypical cases presenting with vesicles, pustules, and bullae also have been reported.3 Additionally, secondary eruptions called id reactions, or autoeczematization, can present in the setting of dermatophyte infections. Such outbreaks may be due to a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the fungal antigens. Id reactions can manifest in many forms of tinea with patients generally exhibiting pruritic papulovesicular lesions that can present far from the site of origin.4

Patients with id reactions can have atypical and varied presentations. In a case of id reaction due to tinea corporis, a patient presented with vesicles and pustules that grew in number and coalesced to form annular lesions.5 A case of an id reaction caused by tinea pedis also noted the presence of pustules, which are atypical in this form of tinea.6 In another case of tinea pedis, a generalized id reaction was noted, illustrating that such eruptions do not necessarily appear at the original site of infection.7 Additionally, in a rare presentation of tinea invading the nares, a patient developed an erythema multiforme id reaction.8 Id reactions also were noted in 14 patients with refractory otitis externa, illustrating the ability of this fungal infection to persist and infect distant locations.9

Because the differential diagnoses for tinea infection are extensive, pathology or laboratory confirmation is necessary for diagnosis, and potassium hydroxide preparation often is used to diagnose dermatophyte infections.1,2 Additionally, the possibility of a hypersensitivity drug rash should remain in the differential if the patient received allergy-inducing medications prior to the outbreak, which may in turn complicate the diagnosis.

Tinea infections typically can be treated with topical antifungals such as terbinafine, butenafine,1 and luliconazole10; however, more involved cases may require oral antifungal treatment.1 Systemic treatment of tinea corporis includes itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole,11 all of which exhibit fewer side effects and greater efficacy when compared to griseofulvin.12-15

Treatment of id reactions centers on the proper clearance of the dermatophyte infection, and treatment with oral antifungals generally is sufficient. In the cases of id reaction in patients with refractory otitis, some success was achieved with treatment involving immunotherapy with dermatophyte and dust mite allergen extracts coupled with a yeast elimination diet.9 In acute id reactions, topical corticosteroids and antipruritic agents can be applied.4 Rarely, systemic glucocorticoids are required, such as in cases in which the id reaction persists despite proper treatment of the primary infection.16

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a tender pruritic rash on the left wrist that was spreading to the bilateral arms and legs of several years’ duration. An area of a prior biopsy on the left wrist was healing well with use of petroleum jelly and halcinonide cream. The patient denied any constitutional symptoms.

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous papules coalescing into plaques on the bilateral anterior and posterior arms and legs, including some erythematous macules and papules on the palms and soles. The original area of involvement on the left dorsal medial wrist demonstrated a background of erythema with overlying peripheral scaling and resolving violaceous to erythematous papules with signs of serosanguineous crusting (Figure 1). Scattered perifollicular erythema was present on the posterior aspects of the bilateral thighs and arms (Figure 2). Baseline complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel were within reference range.

Clinical histopathology showed evidence of a pustular superficial dermatophyte infection, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated numerous fungal hyphae within subcorneal pustules, indicating pustular tinea. Based on the clinicopathologic correlation, the initial presentation was diagnosed as pustular tinea of the entire left wrist, followed by a generalized id reaction 1 week later.

The patient was prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily to treat the diffuse involvement of the pustular tinea as well as once-daily oral cetirizine, once-daily oral diphenhydramine, a topical emollient, and a topical nonsteroidal antipruritic gel.

Tinea is a superficial fungal infection commonly caused by the dermatophytes Epidermophyton, Trichophyton, and Microsporum. It has a variety of clinical presentations based on the anatomic location, including tinea capitis (hair/scalp), tinea pedis (feet), tinea corporis (face/trunk/extremities), tinea cruris (groin), and tinea unguium (nails).1 Tinea infections occur in the stratum corneum, hair, and nails, thriving on dead keratin in these areas.2 Tinea corporis usually appears as an erythematous ring-shaped lesion with a scaly border, but atypical cases presenting with vesicles, pustules, and bullae also have been reported.3 Additionally, secondary eruptions called id reactions, or autoeczematization, can present in the setting of dermatophyte infections. Such outbreaks may be due to a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the fungal antigens. Id reactions can manifest in many forms of tinea with patients generally exhibiting pruritic papulovesicular lesions that can present far from the site of origin.4

Patients with id reactions can have atypical and varied presentations. In a case of id reaction due to tinea corporis, a patient presented with vesicles and pustules that grew in number and coalesced to form annular lesions.5 A case of an id reaction caused by tinea pedis also noted the presence of pustules, which are atypical in this form of tinea.6 In another case of tinea pedis, a generalized id reaction was noted, illustrating that such eruptions do not necessarily appear at the original site of infection.7 Additionally, in a rare presentation of tinea invading the nares, a patient developed an erythema multiforme id reaction.8 Id reactions also were noted in 14 patients with refractory otitis externa, illustrating the ability of this fungal infection to persist and infect distant locations.9

Because the differential diagnoses for tinea infection are extensive, pathology or laboratory confirmation is necessary for diagnosis, and potassium hydroxide preparation often is used to diagnose dermatophyte infections.1,2 Additionally, the possibility of a hypersensitivity drug rash should remain in the differential if the patient received allergy-inducing medications prior to the outbreak, which may in turn complicate the diagnosis.

Tinea infections typically can be treated with topical antifungals such as terbinafine, butenafine,1 and luliconazole10; however, more involved cases may require oral antifungal treatment.1 Systemic treatment of tinea corporis includes itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole,11 all of which exhibit fewer side effects and greater efficacy when compared to griseofulvin.12-15

Treatment of id reactions centers on the proper clearance of the dermatophyte infection, and treatment with oral antifungals generally is sufficient. In the cases of id reaction in patients with refractory otitis, some success was achieved with treatment involving immunotherapy with dermatophyte and dust mite allergen extracts coupled with a yeast elimination diet.9 In acute id reactions, topical corticosteroids and antipruritic agents can be applied.4 Rarely, systemic glucocorticoids are required, such as in cases in which the id reaction persists despite proper treatment of the primary infection.16

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury Stone M. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:702-710.

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Hanover, NH: Elsevier, Inc; 2010.

- Ziemer M, Seyfarth F, Elsner P, et al. Atypical manifestations of tinea corporis. Mycoses. 2007;50(suppl 2):31-35.

- Cheng N, Rucker Wright D, Cohen BA. Dermatophytid in tinea capitis: rarely reported common phenomenon with clinical implications [published online July 4, 2011]. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e453-e457.

- Ohno S, Tanabe H, Kawasaki M, et al. Tinea corporis with acute inflammation caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. J Dermatol. 2008;35:590-593.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Pustular tinea pedis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:132-133.

- Iglesias ME, España A, Idoate MA, et al. Generalized skin reaction following tinea pedis (dermatophytids). J Dermatol. 1994;21:31-34.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste M. Erythema multiforme ID reaction in atypical dermatophytosis: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:699-701.

- Derebery J, Berliner KI. Foot and ear disease—the dermatophytid reaction in otology. Laryngoscope. 1996;106(2 Pt 1):181-186.

- Khanna D, Bharti S. Luliconazole for the treatment of fungal infections: an evidence-based review. Core Evid. 2014;9:113-124.

- Korting HC, Schöllmann C. The significance of itraconazole for treatment of fungal infections of skin, nails and mucous membranes. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:11-20.

- Goldstein AO, Goldstein BG. Dermatophyte (tinea) infections. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatophyte-tinea-infections. Updated December 28, 2018. Accessed April 24, 2019.

- Cole GW, Stricklin G. A comparison of a new oral antifungal, terbinafine, with griseofulvin as therapy for tinea corporis. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1537.

- Panagiotidou D, Kousidou T, Chaidemenos G, et al. A comparison of itraconazole and griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris: a double-blind study. J Int Med Res. 1992;20:392-400.

- Faergemann J, Mörk NJ, Haglund A, et al. A multicentre (double-blind) comparative study to assess the safety and efficacy of fluconazole and griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:575-577.

- Ilkit M, Durdu M, Karakas M. Cutaneous id reactions: a comprehensive review of clinical manifestations, epidemiology, etiology, and management. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2012;38:191-202.

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury Stone M. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:702-710.

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Hanover, NH: Elsevier, Inc; 2010.

- Ziemer M, Seyfarth F, Elsner P, et al. Atypical manifestations of tinea corporis. Mycoses. 2007;50(suppl 2):31-35.

- Cheng N, Rucker Wright D, Cohen BA. Dermatophytid in tinea capitis: rarely reported common phenomenon with clinical implications [published online July 4, 2011]. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e453-e457.

- Ohno S, Tanabe H, Kawasaki M, et al. Tinea corporis with acute inflammation caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. J Dermatol. 2008;35:590-593.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Pustular tinea pedis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:132-133.

- Iglesias ME, España A, Idoate MA, et al. Generalized skin reaction following tinea pedis (dermatophytids). J Dermatol. 1994;21:31-34.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste M. Erythema multiforme ID reaction in atypical dermatophytosis: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:699-701.

- Derebery J, Berliner KI. Foot and ear disease—the dermatophytid reaction in otology. Laryngoscope. 1996;106(2 Pt 1):181-186.

- Khanna D, Bharti S. Luliconazole for the treatment of fungal infections: an evidence-based review. Core Evid. 2014;9:113-124.

- Korting HC, Schöllmann C. The significance of itraconazole for treatment of fungal infections of skin, nails and mucous membranes. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:11-20.

- Goldstein AO, Goldstein BG. Dermatophyte (tinea) infections. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatophyte-tinea-infections. Updated December 28, 2018. Accessed April 24, 2019.

- Cole GW, Stricklin G. A comparison of a new oral antifungal, terbinafine, with griseofulvin as therapy for tinea corporis. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1537.

- Panagiotidou D, Kousidou T, Chaidemenos G, et al. A comparison of itraconazole and griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris: a double-blind study. J Int Med Res. 1992;20:392-400.

- Faergemann J, Mörk NJ, Haglund A, et al. A multicentre (double-blind) comparative study to assess the safety and efficacy of fluconazole and griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:575-577.

- Ilkit M, Durdu M, Karakas M. Cutaneous id reactions: a comprehensive review of clinical manifestations, epidemiology, etiology, and management. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2012;38:191-202.

Practice Points

• Id reactions, or autoeczematization, can occur secondary to dermatophyte infections, possibly due to a hypersensitivity reaction to the fungus. These eruptions can occur in many forms of tinea and in a variety of clinical presentations.

• Treatment is based on clearance of the original dermatophyte infection.

In women with late preterm mild hypertensive disorders, does immediate delivery versus expectant management differ in terms of neonatal neurodevelopmental outcomes?

Zwertbroek EF, Franssen MT, Broekhuijsen K, et al; HYPITAT-II Study Group. Neonatal developmental and behavioral outcomes of immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring of mild hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: 2-year outcomes of the HYPITAT-II trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.03.024.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

In women with mild hypertensive disorders in the preterm period, the maternal benefits of delivery should be weighed against the consequences of preterm birth for the neonate. In a recent study, Zwertbroek and colleagues sought to evaluate the long-term neurodevelopmental effects of this decision on the offspring.

Details of the study

The authors conducted a follow-up study of the randomized, controlled Hypertension and Preeclampsia Intervention Trial At Term II (HYPITAT-II), in which 704 women diagnosed with late preterm (34–37 weeks) hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, or mild preeclampsia) were randomly assigned to immediate delivery or expectant management.

Expectant management consisted of close monitoring until 37 weeks or until an indication for delivery occurred, whichever came first. Children born to those mothers were eligible for this study (women enrolled during 2011–2015) when they reached 2 years of age; 342 children were included in this analysis. Of note, children from the expectant management group had been delivered at a more advanced gestational age (median, 37.0 vs 36.1 weeks; P<.001) than those in the immediate-delivery group.

Survey tools. Parents completed 2 response surveys, the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ) and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), between 23 and 26 months’ corrected age. The ASQ is designed to detect developmental delay, while the CBCL assesses behavioral and emotional problems. The primary outcome was an abnormal result on either screen.

Results. Based on 330 returned questionnaires, the authors found more abnormal ASQ scores (45 of 162 [28%] vs 27 of 148 [18%] children; P = .045) in the immediate-delivery group versus the expectant management group, most pronounced in the fine motor domain. They found no difference in the CBCL scores. The authors concluded that immediate delivery for women with late preterm mild hypertensive disorders in pregnancy increases the risk of developmental delay in the children.

Study strengths and limitations

This study is unique as a planned follow-up to a randomized, controlled trial, allowing for 2-year outcomes to be assessed on children of enrolled women with mild hypertensive disorders in the late preterm period. The authors used validated surveys that are known to predict long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Continue to: This work has several limitations...

This work has several limitations, however. Randomization was not truly maintained given the less than 50% response rate of original participants. Additionally, parents completed the surveys and provider confirmation of developmental concerns or diagnoses was not obtained. Further, assessments at 2 years of age may be too early to detect subtle differences, with evaluations at 5 years more predictive of long-term outcomes; the authors stated that these data already are being collected.

Finally, while these data importantly reinforce the conclusions of the parent HYPITAT-II trial, which support expectant management for mild hypertensive disorders in the late preterm period,1 clinicians must always take care to individualize decisions in the face of worsening maternal disease.

This follow-up study of the HYPITAT-II randomized, controlled trial demonstrates poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring of late preterm mild hypertensives who undergo immediate delivery. These data support current practice recommendations to expectantly manage women with late preterm mild hypertensive disease until 37 weeks or signs of clinical worsening, whichever comes first.

- Broekjuijsen K, van Baaren GJ, van Pampus MG, et al; HYPITAT-II Study Group. Immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation (HYPITAT-II): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2492-2501.

Zwertbroek EF, Franssen MT, Broekhuijsen K, et al; HYPITAT-II Study Group. Neonatal developmental and behavioral outcomes of immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring of mild hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: 2-year outcomes of the HYPITAT-II trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.03.024.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

In women with mild hypertensive disorders in the preterm period, the maternal benefits of delivery should be weighed against the consequences of preterm birth for the neonate. In a recent study, Zwertbroek and colleagues sought to evaluate the long-term neurodevelopmental effects of this decision on the offspring.

Details of the study

The authors conducted a follow-up study of the randomized, controlled Hypertension and Preeclampsia Intervention Trial At Term II (HYPITAT-II), in which 704 women diagnosed with late preterm (34–37 weeks) hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, or mild preeclampsia) were randomly assigned to immediate delivery or expectant management.

Expectant management consisted of close monitoring until 37 weeks or until an indication for delivery occurred, whichever came first. Children born to those mothers were eligible for this study (women enrolled during 2011–2015) when they reached 2 years of age; 342 children were included in this analysis. Of note, children from the expectant management group had been delivered at a more advanced gestational age (median, 37.0 vs 36.1 weeks; P<.001) than those in the immediate-delivery group.

Survey tools. Parents completed 2 response surveys, the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ) and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), between 23 and 26 months’ corrected age. The ASQ is designed to detect developmental delay, while the CBCL assesses behavioral and emotional problems. The primary outcome was an abnormal result on either screen.

Results. Based on 330 returned questionnaires, the authors found more abnormal ASQ scores (45 of 162 [28%] vs 27 of 148 [18%] children; P = .045) in the immediate-delivery group versus the expectant management group, most pronounced in the fine motor domain. They found no difference in the CBCL scores. The authors concluded that immediate delivery for women with late preterm mild hypertensive disorders in pregnancy increases the risk of developmental delay in the children.

Study strengths and limitations

This study is unique as a planned follow-up to a randomized, controlled trial, allowing for 2-year outcomes to be assessed on children of enrolled women with mild hypertensive disorders in the late preterm period. The authors used validated surveys that are known to predict long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Continue to: This work has several limitations...

This work has several limitations, however. Randomization was not truly maintained given the less than 50% response rate of original participants. Additionally, parents completed the surveys and provider confirmation of developmental concerns or diagnoses was not obtained. Further, assessments at 2 years of age may be too early to detect subtle differences, with evaluations at 5 years more predictive of long-term outcomes; the authors stated that these data already are being collected.

Finally, while these data importantly reinforce the conclusions of the parent HYPITAT-II trial, which support expectant management for mild hypertensive disorders in the late preterm period,1 clinicians must always take care to individualize decisions in the face of worsening maternal disease.

This follow-up study of the HYPITAT-II randomized, controlled trial demonstrates poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring of late preterm mild hypertensives who undergo immediate delivery. These data support current practice recommendations to expectantly manage women with late preterm mild hypertensive disease until 37 weeks or signs of clinical worsening, whichever comes first.

Zwertbroek EF, Franssen MT, Broekhuijsen K, et al; HYPITAT-II Study Group. Neonatal developmental and behavioral outcomes of immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring of mild hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: 2-year outcomes of the HYPITAT-II trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.03.024.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

In women with mild hypertensive disorders in the preterm period, the maternal benefits of delivery should be weighed against the consequences of preterm birth for the neonate. In a recent study, Zwertbroek and colleagues sought to evaluate the long-term neurodevelopmental effects of this decision on the offspring.

Details of the study

The authors conducted a follow-up study of the randomized, controlled Hypertension and Preeclampsia Intervention Trial At Term II (HYPITAT-II), in which 704 women diagnosed with late preterm (34–37 weeks) hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, or mild preeclampsia) were randomly assigned to immediate delivery or expectant management.

Expectant management consisted of close monitoring until 37 weeks or until an indication for delivery occurred, whichever came first. Children born to those mothers were eligible for this study (women enrolled during 2011–2015) when they reached 2 years of age; 342 children were included in this analysis. Of note, children from the expectant management group had been delivered at a more advanced gestational age (median, 37.0 vs 36.1 weeks; P<.001) than those in the immediate-delivery group.

Survey tools. Parents completed 2 response surveys, the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ) and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), between 23 and 26 months’ corrected age. The ASQ is designed to detect developmental delay, while the CBCL assesses behavioral and emotional problems. The primary outcome was an abnormal result on either screen.

Results. Based on 330 returned questionnaires, the authors found more abnormal ASQ scores (45 of 162 [28%] vs 27 of 148 [18%] children; P = .045) in the immediate-delivery group versus the expectant management group, most pronounced in the fine motor domain. They found no difference in the CBCL scores. The authors concluded that immediate delivery for women with late preterm mild hypertensive disorders in pregnancy increases the risk of developmental delay in the children.

Study strengths and limitations

This study is unique as a planned follow-up to a randomized, controlled trial, allowing for 2-year outcomes to be assessed on children of enrolled women with mild hypertensive disorders in the late preterm period. The authors used validated surveys that are known to predict long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Continue to: This work has several limitations...

This work has several limitations, however. Randomization was not truly maintained given the less than 50% response rate of original participants. Additionally, parents completed the surveys and provider confirmation of developmental concerns or diagnoses was not obtained. Further, assessments at 2 years of age may be too early to detect subtle differences, with evaluations at 5 years more predictive of long-term outcomes; the authors stated that these data already are being collected.

Finally, while these data importantly reinforce the conclusions of the parent HYPITAT-II trial, which support expectant management for mild hypertensive disorders in the late preterm period,1 clinicians must always take care to individualize decisions in the face of worsening maternal disease.

This follow-up study of the HYPITAT-II randomized, controlled trial demonstrates poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring of late preterm mild hypertensives who undergo immediate delivery. These data support current practice recommendations to expectantly manage women with late preterm mild hypertensive disease until 37 weeks or signs of clinical worsening, whichever comes first.

- Broekjuijsen K, van Baaren GJ, van Pampus MG, et al; HYPITAT-II Study Group. Immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation (HYPITAT-II): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2492-2501.

- Broekjuijsen K, van Baaren GJ, van Pampus MG, et al; HYPITAT-II Study Group. Immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation (HYPITAT-II): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2492-2501.

Lack of inhaler at school a major barrier to asthma care

BALTIMORE – frequently because the parent did not provide an inhaler or did not provide a written order for one, according to new research. Only seven U.S. states have laws allowing schools to stock albuterol for students.

“Most students only have access to this lifesaving medication when they bring a personal inhaler,” Alexandra M. Sims, MD, of Children’s National Hospital in Washington and colleagues wrote in their abstract at the annual meeting of Pediatric Academic Societies. “Interventions that address medication availability may be an important step in removing obstacles to asthma care in school.”

One such option is a stock inhaler available for any students to use. National guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that students with asthma have access to inhaled albuterol at school, yet most states do not have legislation related to albuterol stocking in schools, according to the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America.

Not having access to rescue inhaler medication at school contributes to lost class time and referrals to the emergency department, the authors note in their background information. Yet, “in most U.S. jurisdictions, including the school district we examined, students need both a personal albuterol inhaler and a physician order to receive medication at school.”

To determine what barriers exist regarding students’ asthma care in schools, the authors sent 166 school nurses in an urban school district an anonymous survey during the 2015-2016 school year. The survey asked about 21 factors that could delay or prevent students from returning to class and asked nurses’ agreement or disagreement with 25 additional statements.

The 130 respondents made up a 78% response rate. The institutions represented by the nurses included 44% elementary schools, 9% middle schools, 16% high schools, and 32% other (such as those who may serve multiple schools).

The majority of respondents (72%) agreed that asthma is one of the biggest health problems students face, particularly among middle and high school students (P less than .05). Most (74%) also said an albuterol inhaler at school could reduce the likelihood of students with asthma needing to leave school early.

The largest barrier to students returning to class was parents not providing an albuterol inhaler and/or a written order for an inhaler despite a request from the nurse, according to 69% of the respondents (P less than .05). In high schools in particular, another barrier was students simply not bringing their inhaler to school even though they usually carry one (P less than .01).

Only 15% of nurses saw disease severity as a significant barrier, and 17% cited the staff not adequately recognizing a student’s symptoms.

The researchers did not note use of external funding or author disclosures.

BALTIMORE – frequently because the parent did not provide an inhaler or did not provide a written order for one, according to new research. Only seven U.S. states have laws allowing schools to stock albuterol for students.

“Most students only have access to this lifesaving medication when they bring a personal inhaler,” Alexandra M. Sims, MD, of Children’s National Hospital in Washington and colleagues wrote in their abstract at the annual meeting of Pediatric Academic Societies. “Interventions that address medication availability may be an important step in removing obstacles to asthma care in school.”

One such option is a stock inhaler available for any students to use. National guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that students with asthma have access to inhaled albuterol at school, yet most states do not have legislation related to albuterol stocking in schools, according to the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America.

Not having access to rescue inhaler medication at school contributes to lost class time and referrals to the emergency department, the authors note in their background information. Yet, “in most U.S. jurisdictions, including the school district we examined, students need both a personal albuterol inhaler and a physician order to receive medication at school.”

To determine what barriers exist regarding students’ asthma care in schools, the authors sent 166 school nurses in an urban school district an anonymous survey during the 2015-2016 school year. The survey asked about 21 factors that could delay or prevent students from returning to class and asked nurses’ agreement or disagreement with 25 additional statements.

The 130 respondents made up a 78% response rate. The institutions represented by the nurses included 44% elementary schools, 9% middle schools, 16% high schools, and 32% other (such as those who may serve multiple schools).

The majority of respondents (72%) agreed that asthma is one of the biggest health problems students face, particularly among middle and high school students (P less than .05). Most (74%) also said an albuterol inhaler at school could reduce the likelihood of students with asthma needing to leave school early.

The largest barrier to students returning to class was parents not providing an albuterol inhaler and/or a written order for an inhaler despite a request from the nurse, according to 69% of the respondents (P less than .05). In high schools in particular, another barrier was students simply not bringing their inhaler to school even though they usually carry one (P less than .01).

Only 15% of nurses saw disease severity as a significant barrier, and 17% cited the staff not adequately recognizing a student’s symptoms.

The researchers did not note use of external funding or author disclosures.

BALTIMORE – frequently because the parent did not provide an inhaler or did not provide a written order for one, according to new research. Only seven U.S. states have laws allowing schools to stock albuterol for students.

“Most students only have access to this lifesaving medication when they bring a personal inhaler,” Alexandra M. Sims, MD, of Children’s National Hospital in Washington and colleagues wrote in their abstract at the annual meeting of Pediatric Academic Societies. “Interventions that address medication availability may be an important step in removing obstacles to asthma care in school.”

One such option is a stock inhaler available for any students to use. National guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that students with asthma have access to inhaled albuterol at school, yet most states do not have legislation related to albuterol stocking in schools, according to the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America.

Not having access to rescue inhaler medication at school contributes to lost class time and referrals to the emergency department, the authors note in their background information. Yet, “in most U.S. jurisdictions, including the school district we examined, students need both a personal albuterol inhaler and a physician order to receive medication at school.”

To determine what barriers exist regarding students’ asthma care in schools, the authors sent 166 school nurses in an urban school district an anonymous survey during the 2015-2016 school year. The survey asked about 21 factors that could delay or prevent students from returning to class and asked nurses’ agreement or disagreement with 25 additional statements.