User login

Mobile SpA apps abound, but there’s room for quality improvement

MADISON, WISC. – according to a recent review.

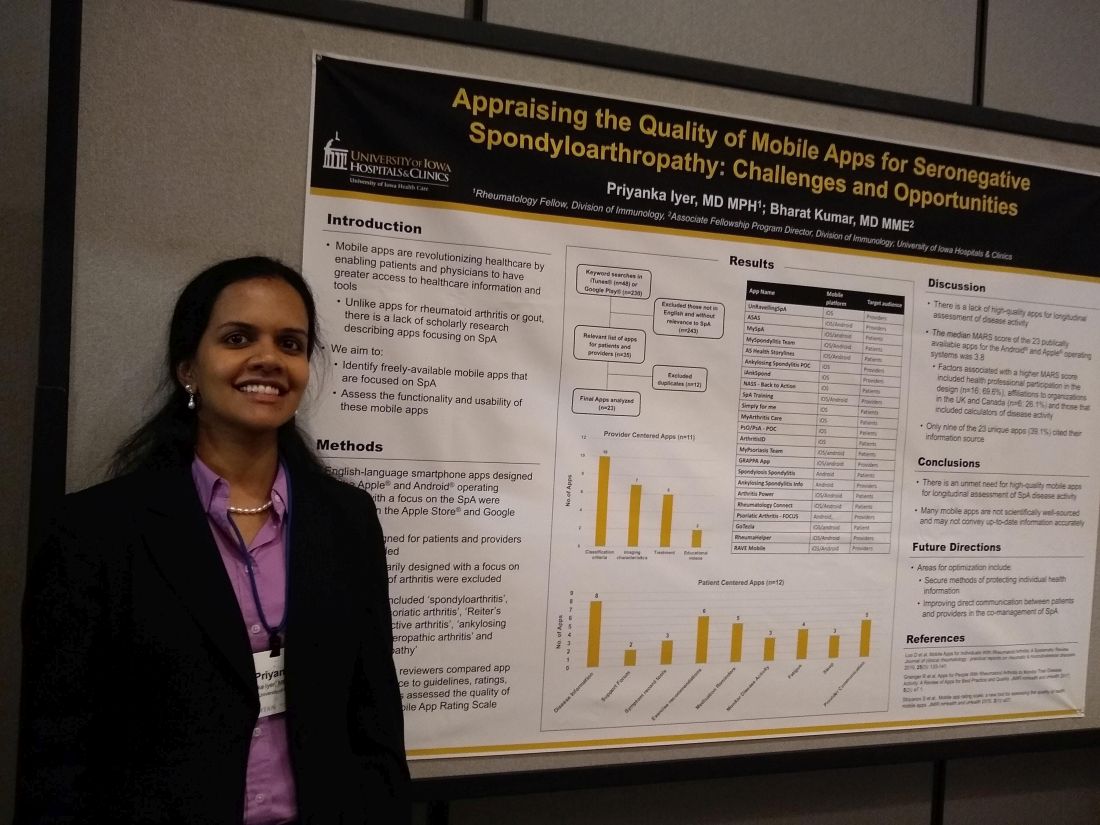

In assessing the 23 publicly available apps aimed at patients or providers, the median score on a common assessment of smartphone apps was just 3.8 on a 5-point scale, said Priyanka Iyer, MBBS, MPH.

Speaking in an interview at the annual meeting of the Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network (SPARTAN), Dr. Iyer pointed out several ways that apps could be optimized. Foremost, she said, is providing secure ways to store and transmit protected health information. Also, apps still haven’t realized their potential to support true comanagement of spondyloarthritis (SpA) via secure, direct patient-provider communication.

“This is an area that we researched previously in rheumatoid arthritis and gout,” explained Dr. Iyer, a rheumatology fellow at the University of Iowa, Iowa City. “We found 23 apps that are available between the Android and iOS platforms; most of them are actually centered towards patients.” In their review, Dr. Iyer and coauthor, Bharat Kumar, MD, had excluded apps that primarily focused on other types of arthritis, using search terms that focused on SpA.

In looking at the 11 provider-centered apps and the 12 that were patient focused, Dr. Iyer and coauthor independently reviewed features of each app. Factors they considered included adherence to guidelines, amount of correct medical information provided, and specific features including capacity to store imaging and test results, and ability to host patient-provider communication.

Of the provider-centered apps, 10 contained appropriate classification criteria, and 7 also contained medical imaging characteristics of the target conditions. Six apps guided providers through treatment options, and two had educational videos.

Of the 12 patient-centered apps, 8 provided disease information, and 6 gave exercise recommendations. Five of the apps had prompts that reminded patients to take medication, and three had tools to help patients record and track symptoms. Similarly, three apps had features to help patients monitor disease activity. Two of the apps were primarily access points for a patient support forum.

Additionally, each app was evaluated by each reviewer using the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS), said Dr. Iyer. “The overall rating was pretty low, at 3.8 [of a possible 5.0]. Factors that increased the MARS scores included affiliations to organizations in the United Kingdom and Canada; for patients who use these apps, their information is automatically transmitted to their providers, and they are able to also access imaging and most of their other health care information on the app.”

Another factor associated with a higher MARS score was design that included health professional participation, which was the case for 16 apps (69.6%). Apps that included calculators of disease activity were also more likely to achieve a higher MARS score, Dr. Iyer and coauthor wrote.

Notably, just 9 of 23 apps (39.1%) included citations referencing their source for medical information.

“I think future areas for improvement and for development of apps include securing individual health information to allow direct communication between patients and providers,” Dr. Iyer said. “I hope that some patients use these apps to learn, and to help their self-management improve.”

“There is an unmet need for high-quality mobile apps for longitudinal assessment of SpA disease activity,” Dr. Iyer and colleagues wrote in the poster accompanying the presentation. “Many mobile apps are not scientifically well sourced and may not convey up-to-date information accurately.”

The authors reported no conflicts of interest and no outside sources of funding.

SOURCE: Iyer P et al. SPARTAN 2019.

MADISON, WISC. – according to a recent review.

In assessing the 23 publicly available apps aimed at patients or providers, the median score on a common assessment of smartphone apps was just 3.8 on a 5-point scale, said Priyanka Iyer, MBBS, MPH.

Speaking in an interview at the annual meeting of the Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network (SPARTAN), Dr. Iyer pointed out several ways that apps could be optimized. Foremost, she said, is providing secure ways to store and transmit protected health information. Also, apps still haven’t realized their potential to support true comanagement of spondyloarthritis (SpA) via secure, direct patient-provider communication.

“This is an area that we researched previously in rheumatoid arthritis and gout,” explained Dr. Iyer, a rheumatology fellow at the University of Iowa, Iowa City. “We found 23 apps that are available between the Android and iOS platforms; most of them are actually centered towards patients.” In their review, Dr. Iyer and coauthor, Bharat Kumar, MD, had excluded apps that primarily focused on other types of arthritis, using search terms that focused on SpA.

In looking at the 11 provider-centered apps and the 12 that were patient focused, Dr. Iyer and coauthor independently reviewed features of each app. Factors they considered included adherence to guidelines, amount of correct medical information provided, and specific features including capacity to store imaging and test results, and ability to host patient-provider communication.

Of the provider-centered apps, 10 contained appropriate classification criteria, and 7 also contained medical imaging characteristics of the target conditions. Six apps guided providers through treatment options, and two had educational videos.

Of the 12 patient-centered apps, 8 provided disease information, and 6 gave exercise recommendations. Five of the apps had prompts that reminded patients to take medication, and three had tools to help patients record and track symptoms. Similarly, three apps had features to help patients monitor disease activity. Two of the apps were primarily access points for a patient support forum.

Additionally, each app was evaluated by each reviewer using the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS), said Dr. Iyer. “The overall rating was pretty low, at 3.8 [of a possible 5.0]. Factors that increased the MARS scores included affiliations to organizations in the United Kingdom and Canada; for patients who use these apps, their information is automatically transmitted to their providers, and they are able to also access imaging and most of their other health care information on the app.”

Another factor associated with a higher MARS score was design that included health professional participation, which was the case for 16 apps (69.6%). Apps that included calculators of disease activity were also more likely to achieve a higher MARS score, Dr. Iyer and coauthor wrote.

Notably, just 9 of 23 apps (39.1%) included citations referencing their source for medical information.

“I think future areas for improvement and for development of apps include securing individual health information to allow direct communication between patients and providers,” Dr. Iyer said. “I hope that some patients use these apps to learn, and to help their self-management improve.”

“There is an unmet need for high-quality mobile apps for longitudinal assessment of SpA disease activity,” Dr. Iyer and colleagues wrote in the poster accompanying the presentation. “Many mobile apps are not scientifically well sourced and may not convey up-to-date information accurately.”

The authors reported no conflicts of interest and no outside sources of funding.

SOURCE: Iyer P et al. SPARTAN 2019.

MADISON, WISC. – according to a recent review.

In assessing the 23 publicly available apps aimed at patients or providers, the median score on a common assessment of smartphone apps was just 3.8 on a 5-point scale, said Priyanka Iyer, MBBS, MPH.

Speaking in an interview at the annual meeting of the Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network (SPARTAN), Dr. Iyer pointed out several ways that apps could be optimized. Foremost, she said, is providing secure ways to store and transmit protected health information. Also, apps still haven’t realized their potential to support true comanagement of spondyloarthritis (SpA) via secure, direct patient-provider communication.

“This is an area that we researched previously in rheumatoid arthritis and gout,” explained Dr. Iyer, a rheumatology fellow at the University of Iowa, Iowa City. “We found 23 apps that are available between the Android and iOS platforms; most of them are actually centered towards patients.” In their review, Dr. Iyer and coauthor, Bharat Kumar, MD, had excluded apps that primarily focused on other types of arthritis, using search terms that focused on SpA.

In looking at the 11 provider-centered apps and the 12 that were patient focused, Dr. Iyer and coauthor independently reviewed features of each app. Factors they considered included adherence to guidelines, amount of correct medical information provided, and specific features including capacity to store imaging and test results, and ability to host patient-provider communication.

Of the provider-centered apps, 10 contained appropriate classification criteria, and 7 also contained medical imaging characteristics of the target conditions. Six apps guided providers through treatment options, and two had educational videos.

Of the 12 patient-centered apps, 8 provided disease information, and 6 gave exercise recommendations. Five of the apps had prompts that reminded patients to take medication, and three had tools to help patients record and track symptoms. Similarly, three apps had features to help patients monitor disease activity. Two of the apps were primarily access points for a patient support forum.

Additionally, each app was evaluated by each reviewer using the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS), said Dr. Iyer. “The overall rating was pretty low, at 3.8 [of a possible 5.0]. Factors that increased the MARS scores included affiliations to organizations in the United Kingdom and Canada; for patients who use these apps, their information is automatically transmitted to their providers, and they are able to also access imaging and most of their other health care information on the app.”

Another factor associated with a higher MARS score was design that included health professional participation, which was the case for 16 apps (69.6%). Apps that included calculators of disease activity were also more likely to achieve a higher MARS score, Dr. Iyer and coauthor wrote.

Notably, just 9 of 23 apps (39.1%) included citations referencing their source for medical information.

“I think future areas for improvement and for development of apps include securing individual health information to allow direct communication between patients and providers,” Dr. Iyer said. “I hope that some patients use these apps to learn, and to help their self-management improve.”

“There is an unmet need for high-quality mobile apps for longitudinal assessment of SpA disease activity,” Dr. Iyer and colleagues wrote in the poster accompanying the presentation. “Many mobile apps are not scientifically well sourced and may not convey up-to-date information accurately.”

The authors reported no conflicts of interest and no outside sources of funding.

SOURCE: Iyer P et al. SPARTAN 2019.

REPORTING FROM SPARTAN 2019

NHIA Conference Wrap-Up

This supplement to Neurology Reviews compiles news briefs from the 2019 National Home Infusion Association annual meeting, which was held in March in Orlando, Florida.

Click here to read the supplement.

This supplement to Neurology Reviews compiles news briefs from the 2019 National Home Infusion Association annual meeting, which was held in March in Orlando, Florida.

Click here to read the supplement.

This supplement to Neurology Reviews compiles news briefs from the 2019 National Home Infusion Association annual meeting, which was held in March in Orlando, Florida.

Click here to read the supplement.

Combo proves most effective in HMA-naive, higher-risk MDS

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – The combination of oral rigosertib and azacitidine is proceeding to a phase 3 trial in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), but it isn’t clear if the combination will continue to be developed for acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

In a phase 1/2 trial, oral rigosertib plus azacitidine produced a 90% response rate in higher-risk MDS patients who were naive to hypomethylating agents (HMAs), a 54% response rate in higher-risk MDS patients who had failed HMA therapy, and a 50% response rate in patients with AML.

Genitourinary toxicities were initially a concern in this trial, but researchers found ways to mitigate the risk of these toxicities, according to Richard Woodman, MD, chief medical officer and senior vice president of research and development at Onconova Therapeutics, the company developing rigosertib.

Dr. Woodman and his colleagues presented results from the phase 1/2 trial in two posters at the Acute Leukemia Forum of Hemedicus.

Results in AML

The researchers reported phase 1 results in 17 patients with AML. Eleven patients had AML, according to investigator assessment, and six patients had refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation, according to French American British criteria, as well as least 20% excess blasts at baseline.

The median age of the patients was 73 years, and 53% were men. Two patients had received no prior therapies, six patients had relapsed disease, and nine were refractory to their last therapy.

Patients received oral rigosertib at escalating doses twice daily on days 1-21 of a 28-day cycle. The recommended phase 2 dose was 840 mg daily (560 mg in the morning and 280 mg in the afternoon), but there were two expansion cohorts in which patients received 1,120 mg daily (560 mg twice a day or 840 mg in the morning and 280 mg in the afternoon). The patients also received azacitidine at 75 mg/m2 per day subcutaneously or intravenously for 7 days starting on day 8.

Patients received a median of three treatment cycles. Fifteen of the 17 patients (88%) discontinued treatment, most because of progressive disease (n = 5), toxicity (n = 4), or death (n = 3).

Twelve patients were evaluable for response, and six (50%) responded. One patient achieved a morphologic complete remission (CR), three achieved a morphologic leukemia-free state, and two had a partial response.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were fatigue (53%), diarrhea (53%), nausea (53%), constipation (47%), back pain (41%), pyrexia (41%), and pneumonia (35%). Grade 3 or higher TEAEs included pneumonia (35%) and anemia (24%).

These results haven’t provided a clear way forward for oral rigosertib and azacitidine in AML. Dr. Woodman said the researchers will have to review past studies and evaluate how AML patients (with at least 20% blasts) have responded to intravenous rigosertib, consult experts in the field, and then decide how they will move forward with oral rigosertib and azacitidine in AML.

Results in MDS

Dr. Woodman and his colleagues presented data on 74 patients with higher-risk MDS. The median age was 69 years, and 59% were men. Most patients were high risk (n = 23) or very high risk (n = 33), according to the Revised International Prognostic Scoring System.

The patients received oral rigosertib at a dose of 840 mg/day or higher on days 1-21 of a 28-day cycle. They also received azacitidine at 75 mg/m2 per day subcutaneously or intravenously for 7 days starting on day 8.

The median duration of treatment was 7.8 months in patients who were HMA naive and 4.9 months in patients who failed HMA therapy. The most common reasons for treatment discontinuation in the HMA-naive patients were toxicity (n = 8), progression (n = 7), and patient request (n = 7). The most common reasons for discontinuation in patients who had failed HMA therapy were progression (n = 12), toxicity (n = 5), and investigator decision (n = 4).

In total, 55 patients were evaluable for response, 26 who had failed HMA therapy and 29 who were HMA naive.

“The best responses, not surprisingly, were in patients that were HMA naive,” Dr. Woodman said.

In the HMA-naive patients, the overall response rate was 90%. Ten patients had a CR, five had a marrow CR with hematologic improvement, three had hematologic improvement alone, eight had a marrow CR alone, and three patients had stable disease. None of the patients progressed.

In the patients who had failed HMA therapy, the overall response rate was 54%. One patient achieved a CR, one had a partial response, five had a marrow CR with hematologic improvement, two had hematologic improvement alone, five had a marrow CR alone, seven had stable disease, and five progressed.

The median duration of response was 10.8 months in patients who failed HMA therapy and 12.2 months in the HMA-naive patients.

The most common TEAEs in the entire MDS cohort were hematuria (45%), constipation (43%), diarrhea (42%), fatigue (42%), dysuria (38%), pyrexia (36%), nausea (35%), neutropenia (31%), and thrombocytopenia (30%).

Grade 3 or higher TEAEs were neutropenia (27%), thrombocytopenia (26%), hematuria (9%), dysuria (9%), diarrhea (5%), fatigue (4%), and pyrexia (1%).

Dr. Woodman said patients who were most likely to be at risk for genitourinary toxicities (hematuria and dysuria) were those who weren’t well hydrated, took rigosertib at night, and didn’t void their bladders before bedtime. He said the researchers’ hypothesis is that there is some local bladder irritation in that setting.

However, the researchers found ways to mitigate the risk of genitourinary toxicities, including:

- Requiring the second dose of rigosertib to be taken in the afternoon rather than evening (about 3 p.m.).

- Asking patients to consume at least 2 liters of fluid per day.

- Having patients empty their bladders before bedtime.

- Assessing urine pH roughly 2 hours after the morning dose of rigosertib and prescribing sodium bicarbonate if the pH is less than 7.5.

Dr. Woodman said the phase 2 results in MDS patients have prompted the development of a phase 3 trial in which researchers will compare oral rigosertib plus azacitidine to azacitidine plus placebo.

Dr. Woodman is employed by Onconova Therapeutics, which sponsored the phase 1/2 trial. The Acute Leukemia Forum is held by Hemedicus, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – The combination of oral rigosertib and azacitidine is proceeding to a phase 3 trial in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), but it isn’t clear if the combination will continue to be developed for acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

In a phase 1/2 trial, oral rigosertib plus azacitidine produced a 90% response rate in higher-risk MDS patients who were naive to hypomethylating agents (HMAs), a 54% response rate in higher-risk MDS patients who had failed HMA therapy, and a 50% response rate in patients with AML.

Genitourinary toxicities were initially a concern in this trial, but researchers found ways to mitigate the risk of these toxicities, according to Richard Woodman, MD, chief medical officer and senior vice president of research and development at Onconova Therapeutics, the company developing rigosertib.

Dr. Woodman and his colleagues presented results from the phase 1/2 trial in two posters at the Acute Leukemia Forum of Hemedicus.

Results in AML

The researchers reported phase 1 results in 17 patients with AML. Eleven patients had AML, according to investigator assessment, and six patients had refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation, according to French American British criteria, as well as least 20% excess blasts at baseline.

The median age of the patients was 73 years, and 53% were men. Two patients had received no prior therapies, six patients had relapsed disease, and nine were refractory to their last therapy.

Patients received oral rigosertib at escalating doses twice daily on days 1-21 of a 28-day cycle. The recommended phase 2 dose was 840 mg daily (560 mg in the morning and 280 mg in the afternoon), but there were two expansion cohorts in which patients received 1,120 mg daily (560 mg twice a day or 840 mg in the morning and 280 mg in the afternoon). The patients also received azacitidine at 75 mg/m2 per day subcutaneously or intravenously for 7 days starting on day 8.

Patients received a median of three treatment cycles. Fifteen of the 17 patients (88%) discontinued treatment, most because of progressive disease (n = 5), toxicity (n = 4), or death (n = 3).

Twelve patients were evaluable for response, and six (50%) responded. One patient achieved a morphologic complete remission (CR), three achieved a morphologic leukemia-free state, and two had a partial response.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were fatigue (53%), diarrhea (53%), nausea (53%), constipation (47%), back pain (41%), pyrexia (41%), and pneumonia (35%). Grade 3 or higher TEAEs included pneumonia (35%) and anemia (24%).

These results haven’t provided a clear way forward for oral rigosertib and azacitidine in AML. Dr. Woodman said the researchers will have to review past studies and evaluate how AML patients (with at least 20% blasts) have responded to intravenous rigosertib, consult experts in the field, and then decide how they will move forward with oral rigosertib and azacitidine in AML.

Results in MDS

Dr. Woodman and his colleagues presented data on 74 patients with higher-risk MDS. The median age was 69 years, and 59% were men. Most patients were high risk (n = 23) or very high risk (n = 33), according to the Revised International Prognostic Scoring System.

The patients received oral rigosertib at a dose of 840 mg/day or higher on days 1-21 of a 28-day cycle. They also received azacitidine at 75 mg/m2 per day subcutaneously or intravenously for 7 days starting on day 8.

The median duration of treatment was 7.8 months in patients who were HMA naive and 4.9 months in patients who failed HMA therapy. The most common reasons for treatment discontinuation in the HMA-naive patients were toxicity (n = 8), progression (n = 7), and patient request (n = 7). The most common reasons for discontinuation in patients who had failed HMA therapy were progression (n = 12), toxicity (n = 5), and investigator decision (n = 4).

In total, 55 patients were evaluable for response, 26 who had failed HMA therapy and 29 who were HMA naive.

“The best responses, not surprisingly, were in patients that were HMA naive,” Dr. Woodman said.

In the HMA-naive patients, the overall response rate was 90%. Ten patients had a CR, five had a marrow CR with hematologic improvement, three had hematologic improvement alone, eight had a marrow CR alone, and three patients had stable disease. None of the patients progressed.

In the patients who had failed HMA therapy, the overall response rate was 54%. One patient achieved a CR, one had a partial response, five had a marrow CR with hematologic improvement, two had hematologic improvement alone, five had a marrow CR alone, seven had stable disease, and five progressed.

The median duration of response was 10.8 months in patients who failed HMA therapy and 12.2 months in the HMA-naive patients.

The most common TEAEs in the entire MDS cohort were hematuria (45%), constipation (43%), diarrhea (42%), fatigue (42%), dysuria (38%), pyrexia (36%), nausea (35%), neutropenia (31%), and thrombocytopenia (30%).

Grade 3 or higher TEAEs were neutropenia (27%), thrombocytopenia (26%), hematuria (9%), dysuria (9%), diarrhea (5%), fatigue (4%), and pyrexia (1%).

Dr. Woodman said patients who were most likely to be at risk for genitourinary toxicities (hematuria and dysuria) were those who weren’t well hydrated, took rigosertib at night, and didn’t void their bladders before bedtime. He said the researchers’ hypothesis is that there is some local bladder irritation in that setting.

However, the researchers found ways to mitigate the risk of genitourinary toxicities, including:

- Requiring the second dose of rigosertib to be taken in the afternoon rather than evening (about 3 p.m.).

- Asking patients to consume at least 2 liters of fluid per day.

- Having patients empty their bladders before bedtime.

- Assessing urine pH roughly 2 hours after the morning dose of rigosertib and prescribing sodium bicarbonate if the pH is less than 7.5.

Dr. Woodman said the phase 2 results in MDS patients have prompted the development of a phase 3 trial in which researchers will compare oral rigosertib plus azacitidine to azacitidine plus placebo.

Dr. Woodman is employed by Onconova Therapeutics, which sponsored the phase 1/2 trial. The Acute Leukemia Forum is held by Hemedicus, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – The combination of oral rigosertib and azacitidine is proceeding to a phase 3 trial in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), but it isn’t clear if the combination will continue to be developed for acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

In a phase 1/2 trial, oral rigosertib plus azacitidine produced a 90% response rate in higher-risk MDS patients who were naive to hypomethylating agents (HMAs), a 54% response rate in higher-risk MDS patients who had failed HMA therapy, and a 50% response rate in patients with AML.

Genitourinary toxicities were initially a concern in this trial, but researchers found ways to mitigate the risk of these toxicities, according to Richard Woodman, MD, chief medical officer and senior vice president of research and development at Onconova Therapeutics, the company developing rigosertib.

Dr. Woodman and his colleagues presented results from the phase 1/2 trial in two posters at the Acute Leukemia Forum of Hemedicus.

Results in AML

The researchers reported phase 1 results in 17 patients with AML. Eleven patients had AML, according to investigator assessment, and six patients had refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation, according to French American British criteria, as well as least 20% excess blasts at baseline.

The median age of the patients was 73 years, and 53% were men. Two patients had received no prior therapies, six patients had relapsed disease, and nine were refractory to their last therapy.

Patients received oral rigosertib at escalating doses twice daily on days 1-21 of a 28-day cycle. The recommended phase 2 dose was 840 mg daily (560 mg in the morning and 280 mg in the afternoon), but there were two expansion cohorts in which patients received 1,120 mg daily (560 mg twice a day or 840 mg in the morning and 280 mg in the afternoon). The patients also received azacitidine at 75 mg/m2 per day subcutaneously or intravenously for 7 days starting on day 8.

Patients received a median of three treatment cycles. Fifteen of the 17 patients (88%) discontinued treatment, most because of progressive disease (n = 5), toxicity (n = 4), or death (n = 3).

Twelve patients were evaluable for response, and six (50%) responded. One patient achieved a morphologic complete remission (CR), three achieved a morphologic leukemia-free state, and two had a partial response.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were fatigue (53%), diarrhea (53%), nausea (53%), constipation (47%), back pain (41%), pyrexia (41%), and pneumonia (35%). Grade 3 or higher TEAEs included pneumonia (35%) and anemia (24%).

These results haven’t provided a clear way forward for oral rigosertib and azacitidine in AML. Dr. Woodman said the researchers will have to review past studies and evaluate how AML patients (with at least 20% blasts) have responded to intravenous rigosertib, consult experts in the field, and then decide how they will move forward with oral rigosertib and azacitidine in AML.

Results in MDS

Dr. Woodman and his colleagues presented data on 74 patients with higher-risk MDS. The median age was 69 years, and 59% were men. Most patients were high risk (n = 23) or very high risk (n = 33), according to the Revised International Prognostic Scoring System.

The patients received oral rigosertib at a dose of 840 mg/day or higher on days 1-21 of a 28-day cycle. They also received azacitidine at 75 mg/m2 per day subcutaneously or intravenously for 7 days starting on day 8.

The median duration of treatment was 7.8 months in patients who were HMA naive and 4.9 months in patients who failed HMA therapy. The most common reasons for treatment discontinuation in the HMA-naive patients were toxicity (n = 8), progression (n = 7), and patient request (n = 7). The most common reasons for discontinuation in patients who had failed HMA therapy were progression (n = 12), toxicity (n = 5), and investigator decision (n = 4).

In total, 55 patients were evaluable for response, 26 who had failed HMA therapy and 29 who were HMA naive.

“The best responses, not surprisingly, were in patients that were HMA naive,” Dr. Woodman said.

In the HMA-naive patients, the overall response rate was 90%. Ten patients had a CR, five had a marrow CR with hematologic improvement, three had hematologic improvement alone, eight had a marrow CR alone, and three patients had stable disease. None of the patients progressed.

In the patients who had failed HMA therapy, the overall response rate was 54%. One patient achieved a CR, one had a partial response, five had a marrow CR with hematologic improvement, two had hematologic improvement alone, five had a marrow CR alone, seven had stable disease, and five progressed.

The median duration of response was 10.8 months in patients who failed HMA therapy and 12.2 months in the HMA-naive patients.

The most common TEAEs in the entire MDS cohort were hematuria (45%), constipation (43%), diarrhea (42%), fatigue (42%), dysuria (38%), pyrexia (36%), nausea (35%), neutropenia (31%), and thrombocytopenia (30%).

Grade 3 or higher TEAEs were neutropenia (27%), thrombocytopenia (26%), hematuria (9%), dysuria (9%), diarrhea (5%), fatigue (4%), and pyrexia (1%).

Dr. Woodman said patients who were most likely to be at risk for genitourinary toxicities (hematuria and dysuria) were those who weren’t well hydrated, took rigosertib at night, and didn’t void their bladders before bedtime. He said the researchers’ hypothesis is that there is some local bladder irritation in that setting.

However, the researchers found ways to mitigate the risk of genitourinary toxicities, including:

- Requiring the second dose of rigosertib to be taken in the afternoon rather than evening (about 3 p.m.).

- Asking patients to consume at least 2 liters of fluid per day.

- Having patients empty their bladders before bedtime.

- Assessing urine pH roughly 2 hours after the morning dose of rigosertib and prescribing sodium bicarbonate if the pH is less than 7.5.

Dr. Woodman said the phase 2 results in MDS patients have prompted the development of a phase 3 trial in which researchers will compare oral rigosertib plus azacitidine to azacitidine plus placebo.

Dr. Woodman is employed by Onconova Therapeutics, which sponsored the phase 1/2 trial. The Acute Leukemia Forum is held by Hemedicus, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

REPORTING FROM ALF 2019

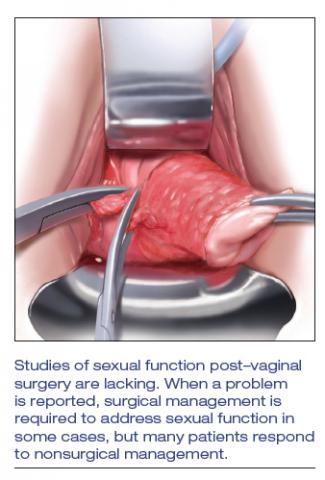

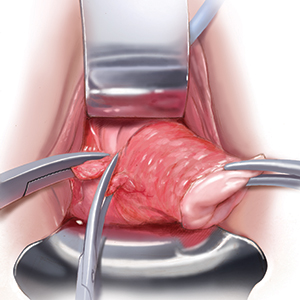

Energy-based therapies in female genital cosmetic surgery: Hype, hope, and a way forward

Energy-based therapy use in gynecology dates back to the early 1970s, when ablative carbon dioxide (C02) lasers were employed to treat cervical erosions.1 Soon after, reports were published on laser treatment for diethylstilbestrol-associated vaginal adenosis, laser laparoscopy for adhesiolysis, laser hysteroscopy, and laser genital wart ablation.2 Starting around 2011, the first articles were published on the use of fractional C02 laser treatment for vulvovaginal atrophy.3,4 Use of laser and light-based therapies to treat “vaginal rejuvenation” is now increasing at an annual rate of 26%. In a few years, North America is expected to be the largest market for vaginal laser rejuvenation. In 2016, more than 500,000 feminine rejuvenation procedures were performed in the United States, and it is estimated that more than 27,000 energy-based devices will be in operation by 2021.5

Clearly, there is considerable public interest and intrigue in office-based female genital cosmetic procedures. In 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration contacted 7 manufacturers of energy-based devices to request revision and clarification for marketing of these devices, since these technologies are neither cleared nor approved for cosmetic vulvovaginal conditions.6 The companies responded within 30 days.

In this article, we appraise the existing literature regarding the mechanism of action of energy-based therapies used in gynecology and review outcomes of their use in female genital cosmetic surgery.

Laser technology devices and how they work

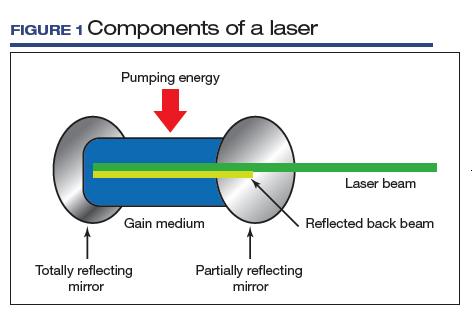

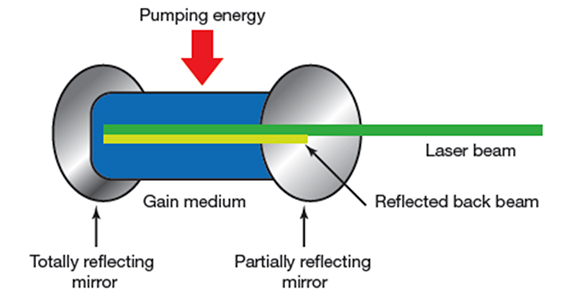

LASER is an acronym for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. Laser devices are composed of 1) an excitable medium (gas, liquid, solid) needed to emit light, 2) an energy source to excite the medium, 3) mirrors to bounce the light back and forth, and 4) a delivery and cooling system (FIGURE 1).

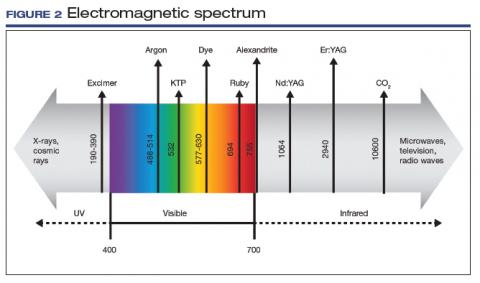

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of all the wavelengths of light, including visible light, radio waves, infrared light, ultraviolet light, x-rays, and gamma rays (FIGURE 2). Most lasers used for the treatment of vulvovaginal disorders, typically C02 and erbium:yttrium aluminum garnet (Er:YAG) lasers, involve the infrared wavelengths.

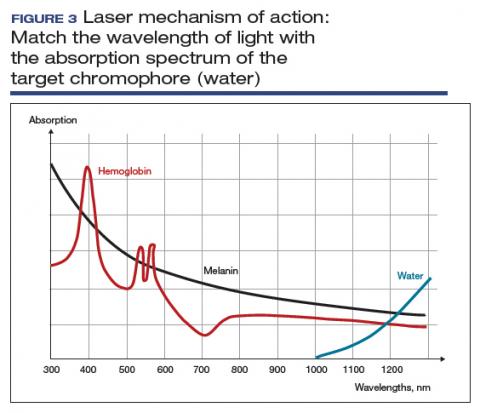

The basic principle of laser treatment is to match the wavelength of the laser with the absorption spectrum of the desired target—a chromophore such as hemoglobin, melanin, or water (FIGURE 3). In essence, light is absorbed by the chromophore (which in vulvar and vaginal tissues is mostly water) and transformed into heat, leading to target destruction. In a fractionated (or fractional) laser beam, the laser is broken up into many smaller beams that treat only portions of the treatment area, with areas of intact epithelium in between the treated areas. At appropriately low thermal denaturation temperatures (45° to 50°C), tissue regeneration can occur through activation of heat shock proteins and tissue growth factors, creating neocollagenesis and neovascularization.

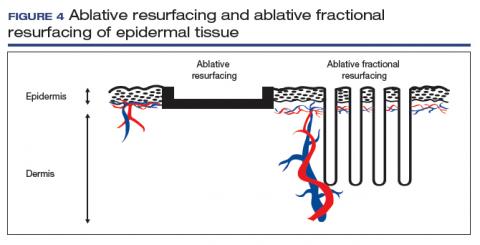

The concept of ablative resurfacing versus fractional resurfacing is borrowed from dermatology (FIGURE 4), understanding that tissue ablation and thermal denaturation occur at temperatures greater than 100°C, as occurs with carbonization of vulvar condylomata.

Continue to: In dermatology, fractionated lasers...

In dermatology, fractionated lasers have been used in the treatment of hair removal, vascular and pigmented lesions, scars, wound healing, tattoo removal, warts, and actinic keratoses. For these conditions, the targeted chromophores are water, hemoglobin, melanosomes, and tattoo ink. The laser pulses must be shorter than the target tissue thermal relaxation times in order to avoid excess heating and collateral tissue damage. Choosing appropriate settings is critical to achieve selective heating, or destruction, of the target tissue. These settings include appropriate wavelengths, pulse durations, and fluence, which is energy delivered per unit area (typically, joules per square centimeter).

For gynecologic conditions, the lasers used are most often CO2, Er:YAG, and hybrid (which include ablative and nonablative wavelengths) devices. In the epithelium of the vagina and vulva, these lasers generally have a very shallow depth of optical penetration, on the order of 10 to 200 µm.

Radiofrequency-based devices emit focused electromagnetic waves

Radiofrequency systems use a wand to deliver radiofrequency energy to create heat within the subepithelial layers of vulvar and vaginal tissues, while the surface remains cool. These devices can use monopolar or bipolar energy (current) to create a reverse thermal gradient designed to heat the deeper tissues transepithelially at a higher temperature while a coolant protects the surface epithelium. Some wand technologies require multiple treatments, while others require only a single treatment.

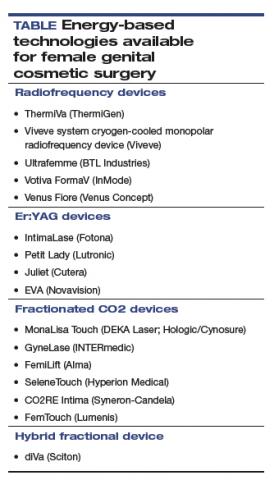

The TABLE lists currently available energy-based technologies.

Therapeutic uses for energy-based devices

Investigators have studied laser devices for treating various gynecologic conditions, including vulvovaginal atrophy, stress urinary incontinence (UI), vaginal laxity, lichen sclerosus, and vulvodynia.

Vulvovaginal atrophy

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) includes symptoms of vulvovaginal irritation, burning, itching, discharge, dyspareunia, lower urinary tract symptoms such as frequency and urinary tract infections, and vaginal dryness or vulvovaginal atrophy.7 First-line treatment for vulvovaginal atrophy includes the use of nonhormonal lubricants for intercourse and vaginal moisturizers, which temporarily moisten the vaginal epithelium. Low-dose vaginal estrogen is a second-line therapy for symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy; newer pharmacologic options include dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) suppositories (prasterone), solubilized estradiol capsules, and the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) ospemifene.

Fractionated CO2, Erb:YAG, and hybrid lasers also have been used to treat women with symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy and GSM through similar mechanisms described in dermatologic conditions with low-temperature laser activation of tissue proteins and growth factors creating new connective tissue and angiogenesis. A number of landmark studies have been published detailing patient outcomes with energy-based treatments for these symptoms.

Three-arm trial. Cruz and colleagues conducted a double-blind randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of fractional CO2 laser vaginal treatment compared with local estriol therapy and the combination of laser plus estriol.8 The investigators randomly assigned 45 postmenopausal women to treatment with fractional CO2 laser with placebo vaginal cream, estriol with sham laser, or laser plus estriol. Treatment consisted of 2 sessions 4 weeks apart, with 20 consecutive weeks of estriol or placebo 3 times per week.

At weeks 8 and 20, the Vaginal Health Index (VHI) average score was significantly higher in all study arms. At week 20, the laser plus estriol group also showed incremental improvement in the VHI score (P = .01). The laser and the laser plus estriol groups had significant improvement in dyspareunia, burning, and dryness, while the estriol group improved only in dryness (P<.001). The laser plus estriol group had significant improvement in the total Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) score (P = .02) and in the individual domains of pain, desire, and lubrication. Although the laser-alone group had significant worsening in the FSFI pain domain (P = .04), all treatment arms had comparable FSFI total scores at week 20. No adverse events were recorded during the study period.

Continue to: Retrospective study...

Retrospective study. To assess the efficacy of 3, 4, or 5 treatments with microablative fractional CO2 laser therapy for symptoms of GSM, Athanasiou and colleagues studied outcomes in 94 postmenopausal women.9 The intensity or bothersomeness of GSM symptoms as well as sexual function significantly improved in this cohort. The intensity of dyspareunia and dryness decreased from a median of 9 (minimum–maximum, 5–10) and 8 (0–10), respectively, at baseline to 0 (0–6) and 0 (0–8) at 1 month after the last laser therapy (P<.001 for all). The FSFI score and the frequency of sexual intercourse rose from 10.8 (2–26.9) and 1 (0–8) at baseline to 27.8 (15.2–35.4) and 4 (2–8) at 1 month after the last laser therapy (P<.001 for all).

The positive effects of laser therapy were unchanged throughout the 12 months of follow-up, and the pattern was the same for symptom-free rates. No adverse events were recorded during the study period.

The investigators noted that, based on short- and long-term follow-up, 4 or 5 laser treatments may be superior to 3 treatments for lowering the intensity of GSM symptoms. They found no differences in outcomes between 4 and 5 laser treatments.

Prospective comparative cohort study. Gaspar and colleagues recruited 50 postmenopausal women with GSM and assigned 25 participants to 2 weeks of pretreatment with estriol ovules 3 times per week (for epithelial hydration) followed by 3 sessions of Er:YAG nonablative laser treatments; 25 women in the active control group received treatment with estriol ovules over 8 weeks.10 Pre- and posttreatment biopsies, maturation index, maturation value, pH, and VAS symptom analysis were recorded up to 18 months after treatment.

Up to the 6-month follow-up, both treatment groups had a statistically significant reduction of all GSM symptoms. At all follow-ups, however, symptom relief was more prominent in the laser-treated group. In addition, the effects of the laser therapy remained statistically significant at the 12- and 18-month follow-ups, while the treatment effects of estriol were diminished at 12 months and, at 18 months, this group had some symptoms that were significantly worse than before treatment.

Overall, adverse effects were minimal and transient in both groups, affecting 4% of participants in the laser group, and 12% in the estriol group.

Long-term effectiveness evaluation. To assess the long-term efficacy and acceptability of vaginal laser treatment for the management of GSM, Gambacciani and colleagues treated 205 postmenopausal women with an Er:YAG laser for 3 applications every 30 days, with evaluations performed after 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months from the last laser treatment.11 An active control group (n = 49) received 3 months of local treatment with either hormonal (estriol gel twice weekly) or nonhormonal (hyaluronic acid-based preparations or moisturizers and lubricants) agents.

Treatment with the ER:YAG laser induced a significant decrease (P<.01) in scores of the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for vulvovaginal atrophy symptoms for vaginal dryness and dyspareunia and an increase in the VHI score (P<.01) up to 12 months after the last treatment. After 18 and 24 months, values returned to levels similar to those at baseline.

Women who also had stress UI (n = 114) received additional laser treatment of the anterior vaginal wall specifically designed for UI, with assessment based on the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF). Laser treatment induced a significant decrease (P<.05) in ICIQ-UI SF scores compared with baseline values, and scores remained lower than baseline values after 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 months after the last laser treatment. Values measured after 18 and 24 months, however, did not differ significantly from baseline.

In the control group, the VAS score showed a similar decrease and comparable pattern during the treatment period. However, after the end of the treatment period, the control group’s VAS scores for vaginal dryness and dyspareunia showed a progressive increase, and after 6 months, the values were significantly different from corresponding values measured in the laser therapy group. The follow-up period in the control group ended after 6 months, because almost all patients started a new local or systemic treatment for their GSM symptoms. No adverse events related to treatment were recorded throughout the study period.

In an earlier pilot study by the same authors, 19 women with GSM who also had mild to moderate stress UI were treated with a vaginal Er:YAG laser.12 Compared with vaginal estriol treatment in the active control group, laser treatment was associated with a significant improvement (P<.01) in ICIQ-SF scores, with rapid and long-lasting effects that persisted up to week 24 of the observation period.

Continue to: Urinary incontinence...

Urinary incontinence

The cause of UI is considered to be multifactorial, including disruption in connective tissue supports of the urethrovesical junction leading to urethral hypermobility, pelvic floor muscle weakness, nerve damage to the urethral rhabdosphincter related to pudendal neuropathy or pelvic plexopathy, and atrophic changes of the urethra mucosa and submucosa. Purported mechanisms of action for energy-based therapies designed for treatment of UI relate to direct effects on connective tissue, blood vessels, and possibly nerves.

In 3 clinical trials designed specifically to treat UI with an Er:YAG laser, women showed subjective symptomatic improvement.

Ogrinc and colleagues followed 175 pre- and postmenopausal women with stress UI or mixed UI in a prospective nonrandomized study.13 They treated women with an Er:YAG laser for an average of 2.5 (0.5) procedures separated by a 2-month period and performed follow-up assessments at 2, 6, and 12 months after treatment.

After treatment, 77% of women with stress UI had significant improvement in symptoms based on the ICIQ SF and the Incontinence Severity Index (ISI), while only 34% of those with mixed UI had no symptoms at 1-year follow-up. No major adverse effects were noted in either group.

Okui compared the effects of Er:YAG laser treatment with those of tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) or transobturator tape (TOT) sling procedures (n = 50 in each group) in women with stress UI or mixed UI.14 At 12 months after treatment, all 3 treatments demonstrated comparable improvements in the women with stress UI. Some patients with mixed UI in the TVT and TOT groups showed exacerbation, while all women in the laser-treated group tended to have symptom improvement.

In another recent study, Blaganje and colleagues randomly assigned 114 premenopausal parous women with stress UI to an Er:YAG laser procedure or sham treatment.15 Three months after treatment, ICIQ-UI SF scores were significantly more improved (P<.001) in the laser-treated group than in the sham group. In addition, 21% of laser-treated patients were dry at follow-up compared with 4% of the sham-treated group.

Key takeaway. While these studies showed promising short-term results for laser treatment of UI, they need to be replicated in appropriately powered clinical trials that include critical subjective and objective outcomes as well as longer-term follow-up for both effectiveness and safety.

Vaginal laxity/pre-prolapse

Vaginal laxity is defined as the symptom of excessive vaginal looseness.16 Also referred to as “pre-prolapse,” this subjective symptom generally refers to a widened vaginal opening (genital hiatus) but with pelvic organ prolapse that is within the vagina or hymen.17 Notably, the definition is ambiguous, and rigorous clinical data based on validated outcomes and prolapse grading are lacking.

Krychman and colleagues conducted the first randomized controlled study comparing monopolar radiofrequency at the vaginal introitus with sham therapy for vaginal laxity in 174 premenopausal women, known as the VIVEVE I trial.18 The primary outcome, the proportion of women reporting no vaginal laxity at 6 months after treatment, was assessed using a vaginal laxity questionnaire, a 7-point rating scale for laxity or tightness ranging from very loose to very tight. With a single radiofrequency treatment, 43.5% of the active group and 19.6% (P = .002) of the sham group obtained the primary outcome.

There were also statistically significant improvements in overall sexual function and decreased sexual distress. The adjusted odds ratio (OR, 3.39; 95% confidence interval, 1.54–7.45) showed that the likelihood of no vaginal laxity at 6 months was more than 3 times greater for women who received the active treatment compared with those who received sham treatment. Adverse events were mild, resolved spontaneously, and were similar in the 2 groups.

Continue to: Outlook for energy-based...

Outlook for energy-based therapies: Cautiously optimistic

Preliminary outcome data on the use of energy-based therapies for female genital cosmetic surgery is largely positive for the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy, but some case series suggest the potential for scarring, burning, and inefficacy. This prompted the FDA to send “It has come to our attention” letters to a number of device manufacturers in 2018.6

Supportive evidence is weak. Early data are encouraging regarding fractionated laser therapy for the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy and stress UI and radiofrequency wand therapy for vaginal laxity and stress UI. Unfortunately, the level of evidence to support wide use of these technologies for all pelvic floor disorders is weak. A recent committee opinion from the International Urogynecology Association noted that only 8 studies (1 randomized trial and 7 observational studies) on these conditions fulfilled the criteria of good quality.19 The International Continence Society and the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disorders recently published a best practice consensus document declaring laser and energy-based treatments in gynecology and urology to be largely experimental.20

Questions persist. Knowledge gaps exist, and recommendations related to subspecialty training—who should perform these procedures (gynecologists, plastic surgeons, urologists, dermatologists, family practitioners) and the level of training needed to safely perform them—are lacking. Patient selection and physician knowledge and experience related to female genital anatomy, female sexual function and dysfunction, multidisciplinary treatment options for various pelvic support problems and UI, as well as psychologic screening for body dysmorphic disorders, need to be considered in terms of treating both the functional and aesthetic aspects related to cosmetic and reconstructive gynecologic surgery.

Special considerations. The use of energy-based therapies in special populations, such as survivors of breast cancer or other gynecologic cancers, as well as women undergoing chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and hormonal manipulation (particularly with antiestrogenic SERMs and aromatase inhibitors) has not been adequately evaluated. A discussion of the risks, benefits, alternatives, and limited long-term outcome data for energy-based therapies in cancer survivors, as for all patients, must be included for adequate informed consent prior to undertaking these treatments.

Guidelines for appropriate tissue priming, laser settings, and concomitant energy-based technology with local hormone treatment (also known as laser-augmented drug delivery) need to be developed. Comparative long-term studies are needed to determine the safety and effectiveness of these technologies.

Caution advised. Given the lack of long-term safety and effectiveness data on energy-based therapies for the vague indications of vaginal laxity, and even for the well-defined conditions of stress UI and vulvovaginal atrophy, clinicians should exercise caution before promoting treatment, which can be expensive and is not without potential complications, such as vaginal pain, adhesive agglutination, and persistent dryness and dyspareunia.21

Fortunately, many randomized trials on various energy-based devices for gynecologic indications (GSM, stress UI, vaginal laxity, lichen sclerosus) are underway, and results from these studies will help inform future clinical practice and guideline development.

- Kaplan I, Goldman J, Ger R. The treatment of erosions of the uterine cervix by means of the CO2 laser. Obstet Gynecol. 1973;41:795-796.

- Tadir Y, Gaspar A, Lev-Sagie A, et al. Light and energy-based therapeutics for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: consensus and controversies. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:137-159.

- Gaspar A, Addamo G, Brandi H. Vaginal fractional CO2 laser: a minimally invasive option for vaginal rejuvenation. Am J Cosmetic Surg. 2011;28:156-162.

- Salvatore S, Leone Roberti Maggiore U, Athanasiou S, et al. Histological study on the effects of microablative fractional CO2 laser on atrophic vaginal tissue: an ex vivo study. Menopause. 2015;22:845-849.

- Benedetto AV. What's new in cosmetic dermatology. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:117-128.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA warns against use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal rejuvenation or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA safety communication. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm615013.htm. Accessed April 8, 2019.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21:1063-1068.

- Cruz VL, Steiner ML, Pompei LM, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial for evaluating the efficacy of fractional CO2 laser compared with topical estriol in the treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2018;25:21-28.

- Athanasiou S, Pitsouni E, Grigoradis T, et al. Microablative fractional CO2 laser for the genitourinary syndrome of menopause: up to 12-month results. Menopause. 2019;26:248-255.

- Gaspar A, Brandi H, Gomez V, et al. Efficacy of Erbium:YAG laser treatment compared to topical estriol treatment for symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:160-168.

- Gambacciani M, Levancini M, Russo E, et al. Long-term effects of vaginal erbium laser in the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Climacteric. 2018;21:148-152.

- Gambacciani M, Levancini M, Cervigni M. Vaginal erbium laser: the second-generation thermotherapy for the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Climacteric. 2015;18:757-763.

- Ogrinc UB, Sencar S, Lenasi H. Novel minimally invasive laser treatment of urinary incontinence in women. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47:689-697.

- Okui N. Comparison between erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser therapy and sling procedures in the treatment of stress and mixed urinary incontinence. World J Urol. 2018. doi:10.1007/s00345-018-2445-x.

- Blaganje M, Scepanovic D, Zgur L, et al. Non-ablative Er:YAG laser therapy effect on stress urinary incontinence related to quality of life and sexual function: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;224:153-158.

- Haylen BT, Maher CF, Barber MD, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Int Urogynecologic J. 2016;27:165-194.

- Garcia B, Pardo J. Academic cosmetic gynecology and energy-based therapies: ambiguities, explorations, and the FDA advisories. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:1-2.

- Krychman M, Rowan CG, Allan BB, et al. Effect of single-treatment, surface-cooled radiofrequency therapy on vaginal laxity and female sexual function: the VIVEVE I randomized controlled trial. J Sex Med. 2017;14:215-225.

- Shobeiri SA, Kerkhof MH, Minassian VA, et al; IUGA Research and Development Committee. IUGA committee opinion: laser-based vaginal devices for treatment of stress urinary incontinence, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, and vaginal laxity. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:371-376.

- Preti M, Vieira-Baptista P, Digesu GA, et al. The clinical role of LASER for vulvar and vaginal treatments in gynecology and female urology: an ICS/ISSVD best practice consensus document. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38:1009-1023.

- Gordon C, Gonzales S, Krychman ML. Rethinking the techno vagina: a case series of patient complications following vaginal laser treatment for atrophy. Menopause. 2019;26:423-427.

Energy-based therapy use in gynecology dates back to the early 1970s, when ablative carbon dioxide (C02) lasers were employed to treat cervical erosions.1 Soon after, reports were published on laser treatment for diethylstilbestrol-associated vaginal adenosis, laser laparoscopy for adhesiolysis, laser hysteroscopy, and laser genital wart ablation.2 Starting around 2011, the first articles were published on the use of fractional C02 laser treatment for vulvovaginal atrophy.3,4 Use of laser and light-based therapies to treat “vaginal rejuvenation” is now increasing at an annual rate of 26%. In a few years, North America is expected to be the largest market for vaginal laser rejuvenation. In 2016, more than 500,000 feminine rejuvenation procedures were performed in the United States, and it is estimated that more than 27,000 energy-based devices will be in operation by 2021.5

Clearly, there is considerable public interest and intrigue in office-based female genital cosmetic procedures. In 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration contacted 7 manufacturers of energy-based devices to request revision and clarification for marketing of these devices, since these technologies are neither cleared nor approved for cosmetic vulvovaginal conditions.6 The companies responded within 30 days.

In this article, we appraise the existing literature regarding the mechanism of action of energy-based therapies used in gynecology and review outcomes of their use in female genital cosmetic surgery.

Laser technology devices and how they work

LASER is an acronym for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. Laser devices are composed of 1) an excitable medium (gas, liquid, solid) needed to emit light, 2) an energy source to excite the medium, 3) mirrors to bounce the light back and forth, and 4) a delivery and cooling system (FIGURE 1).

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of all the wavelengths of light, including visible light, radio waves, infrared light, ultraviolet light, x-rays, and gamma rays (FIGURE 2). Most lasers used for the treatment of vulvovaginal disorders, typically C02 and erbium:yttrium aluminum garnet (Er:YAG) lasers, involve the infrared wavelengths.

The basic principle of laser treatment is to match the wavelength of the laser with the absorption spectrum of the desired target—a chromophore such as hemoglobin, melanin, or water (FIGURE 3). In essence, light is absorbed by the chromophore (which in vulvar and vaginal tissues is mostly water) and transformed into heat, leading to target destruction. In a fractionated (or fractional) laser beam, the laser is broken up into many smaller beams that treat only portions of the treatment area, with areas of intact epithelium in between the treated areas. At appropriately low thermal denaturation temperatures (45° to 50°C), tissue regeneration can occur through activation of heat shock proteins and tissue growth factors, creating neocollagenesis and neovascularization.

The concept of ablative resurfacing versus fractional resurfacing is borrowed from dermatology (FIGURE 4), understanding that tissue ablation and thermal denaturation occur at temperatures greater than 100°C, as occurs with carbonization of vulvar condylomata.

Continue to: In dermatology, fractionated lasers...

In dermatology, fractionated lasers have been used in the treatment of hair removal, vascular and pigmented lesions, scars, wound healing, tattoo removal, warts, and actinic keratoses. For these conditions, the targeted chromophores are water, hemoglobin, melanosomes, and tattoo ink. The laser pulses must be shorter than the target tissue thermal relaxation times in order to avoid excess heating and collateral tissue damage. Choosing appropriate settings is critical to achieve selective heating, or destruction, of the target tissue. These settings include appropriate wavelengths, pulse durations, and fluence, which is energy delivered per unit area (typically, joules per square centimeter).

For gynecologic conditions, the lasers used are most often CO2, Er:YAG, and hybrid (which include ablative and nonablative wavelengths) devices. In the epithelium of the vagina and vulva, these lasers generally have a very shallow depth of optical penetration, on the order of 10 to 200 µm.

Radiofrequency-based devices emit focused electromagnetic waves

Radiofrequency systems use a wand to deliver radiofrequency energy to create heat within the subepithelial layers of vulvar and vaginal tissues, while the surface remains cool. These devices can use monopolar or bipolar energy (current) to create a reverse thermal gradient designed to heat the deeper tissues transepithelially at a higher temperature while a coolant protects the surface epithelium. Some wand technologies require multiple treatments, while others require only a single treatment.

The TABLE lists currently available energy-based technologies.

Therapeutic uses for energy-based devices

Investigators have studied laser devices for treating various gynecologic conditions, including vulvovaginal atrophy, stress urinary incontinence (UI), vaginal laxity, lichen sclerosus, and vulvodynia.

Vulvovaginal atrophy

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) includes symptoms of vulvovaginal irritation, burning, itching, discharge, dyspareunia, lower urinary tract symptoms such as frequency and urinary tract infections, and vaginal dryness or vulvovaginal atrophy.7 First-line treatment for vulvovaginal atrophy includes the use of nonhormonal lubricants for intercourse and vaginal moisturizers, which temporarily moisten the vaginal epithelium. Low-dose vaginal estrogen is a second-line therapy for symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy; newer pharmacologic options include dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) suppositories (prasterone), solubilized estradiol capsules, and the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) ospemifene.

Fractionated CO2, Erb:YAG, and hybrid lasers also have been used to treat women with symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy and GSM through similar mechanisms described in dermatologic conditions with low-temperature laser activation of tissue proteins and growth factors creating new connective tissue and angiogenesis. A number of landmark studies have been published detailing patient outcomes with energy-based treatments for these symptoms.

Three-arm trial. Cruz and colleagues conducted a double-blind randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of fractional CO2 laser vaginal treatment compared with local estriol therapy and the combination of laser plus estriol.8 The investigators randomly assigned 45 postmenopausal women to treatment with fractional CO2 laser with placebo vaginal cream, estriol with sham laser, or laser plus estriol. Treatment consisted of 2 sessions 4 weeks apart, with 20 consecutive weeks of estriol or placebo 3 times per week.

At weeks 8 and 20, the Vaginal Health Index (VHI) average score was significantly higher in all study arms. At week 20, the laser plus estriol group also showed incremental improvement in the VHI score (P = .01). The laser and the laser plus estriol groups had significant improvement in dyspareunia, burning, and dryness, while the estriol group improved only in dryness (P<.001). The laser plus estriol group had significant improvement in the total Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) score (P = .02) and in the individual domains of pain, desire, and lubrication. Although the laser-alone group had significant worsening in the FSFI pain domain (P = .04), all treatment arms had comparable FSFI total scores at week 20. No adverse events were recorded during the study period.

Continue to: Retrospective study...

Retrospective study. To assess the efficacy of 3, 4, or 5 treatments with microablative fractional CO2 laser therapy for symptoms of GSM, Athanasiou and colleagues studied outcomes in 94 postmenopausal women.9 The intensity or bothersomeness of GSM symptoms as well as sexual function significantly improved in this cohort. The intensity of dyspareunia and dryness decreased from a median of 9 (minimum–maximum, 5–10) and 8 (0–10), respectively, at baseline to 0 (0–6) and 0 (0–8) at 1 month after the last laser therapy (P<.001 for all). The FSFI score and the frequency of sexual intercourse rose from 10.8 (2–26.9) and 1 (0–8) at baseline to 27.8 (15.2–35.4) and 4 (2–8) at 1 month after the last laser therapy (P<.001 for all).

The positive effects of laser therapy were unchanged throughout the 12 months of follow-up, and the pattern was the same for symptom-free rates. No adverse events were recorded during the study period.

The investigators noted that, based on short- and long-term follow-up, 4 or 5 laser treatments may be superior to 3 treatments for lowering the intensity of GSM symptoms. They found no differences in outcomes between 4 and 5 laser treatments.

Prospective comparative cohort study. Gaspar and colleagues recruited 50 postmenopausal women with GSM and assigned 25 participants to 2 weeks of pretreatment with estriol ovules 3 times per week (for epithelial hydration) followed by 3 sessions of Er:YAG nonablative laser treatments; 25 women in the active control group received treatment with estriol ovules over 8 weeks.10 Pre- and posttreatment biopsies, maturation index, maturation value, pH, and VAS symptom analysis were recorded up to 18 months after treatment.

Up to the 6-month follow-up, both treatment groups had a statistically significant reduction of all GSM symptoms. At all follow-ups, however, symptom relief was more prominent in the laser-treated group. In addition, the effects of the laser therapy remained statistically significant at the 12- and 18-month follow-ups, while the treatment effects of estriol were diminished at 12 months and, at 18 months, this group had some symptoms that were significantly worse than before treatment.

Overall, adverse effects were minimal and transient in both groups, affecting 4% of participants in the laser group, and 12% in the estriol group.

Long-term effectiveness evaluation. To assess the long-term efficacy and acceptability of vaginal laser treatment for the management of GSM, Gambacciani and colleagues treated 205 postmenopausal women with an Er:YAG laser for 3 applications every 30 days, with evaluations performed after 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months from the last laser treatment.11 An active control group (n = 49) received 3 months of local treatment with either hormonal (estriol gel twice weekly) or nonhormonal (hyaluronic acid-based preparations or moisturizers and lubricants) agents.

Treatment with the ER:YAG laser induced a significant decrease (P<.01) in scores of the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for vulvovaginal atrophy symptoms for vaginal dryness and dyspareunia and an increase in the VHI score (P<.01) up to 12 months after the last treatment. After 18 and 24 months, values returned to levels similar to those at baseline.

Women who also had stress UI (n = 114) received additional laser treatment of the anterior vaginal wall specifically designed for UI, with assessment based on the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF). Laser treatment induced a significant decrease (P<.05) in ICIQ-UI SF scores compared with baseline values, and scores remained lower than baseline values after 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 months after the last laser treatment. Values measured after 18 and 24 months, however, did not differ significantly from baseline.

In the control group, the VAS score showed a similar decrease and comparable pattern during the treatment period. However, after the end of the treatment period, the control group’s VAS scores for vaginal dryness and dyspareunia showed a progressive increase, and after 6 months, the values were significantly different from corresponding values measured in the laser therapy group. The follow-up period in the control group ended after 6 months, because almost all patients started a new local or systemic treatment for their GSM symptoms. No adverse events related to treatment were recorded throughout the study period.

In an earlier pilot study by the same authors, 19 women with GSM who also had mild to moderate stress UI were treated with a vaginal Er:YAG laser.12 Compared with vaginal estriol treatment in the active control group, laser treatment was associated with a significant improvement (P<.01) in ICIQ-SF scores, with rapid and long-lasting effects that persisted up to week 24 of the observation period.

Continue to: Urinary incontinence...

Urinary incontinence

The cause of UI is considered to be multifactorial, including disruption in connective tissue supports of the urethrovesical junction leading to urethral hypermobility, pelvic floor muscle weakness, nerve damage to the urethral rhabdosphincter related to pudendal neuropathy or pelvic plexopathy, and atrophic changes of the urethra mucosa and submucosa. Purported mechanisms of action for energy-based therapies designed for treatment of UI relate to direct effects on connective tissue, blood vessels, and possibly nerves.

In 3 clinical trials designed specifically to treat UI with an Er:YAG laser, women showed subjective symptomatic improvement.

Ogrinc and colleagues followed 175 pre- and postmenopausal women with stress UI or mixed UI in a prospective nonrandomized study.13 They treated women with an Er:YAG laser for an average of 2.5 (0.5) procedures separated by a 2-month period and performed follow-up assessments at 2, 6, and 12 months after treatment.

After treatment, 77% of women with stress UI had significant improvement in symptoms based on the ICIQ SF and the Incontinence Severity Index (ISI), while only 34% of those with mixed UI had no symptoms at 1-year follow-up. No major adverse effects were noted in either group.

Okui compared the effects of Er:YAG laser treatment with those of tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) or transobturator tape (TOT) sling procedures (n = 50 in each group) in women with stress UI or mixed UI.14 At 12 months after treatment, all 3 treatments demonstrated comparable improvements in the women with stress UI. Some patients with mixed UI in the TVT and TOT groups showed exacerbation, while all women in the laser-treated group tended to have symptom improvement.

In another recent study, Blaganje and colleagues randomly assigned 114 premenopausal parous women with stress UI to an Er:YAG laser procedure or sham treatment.15 Three months after treatment, ICIQ-UI SF scores were significantly more improved (P<.001) in the laser-treated group than in the sham group. In addition, 21% of laser-treated patients were dry at follow-up compared with 4% of the sham-treated group.

Key takeaway. While these studies showed promising short-term results for laser treatment of UI, they need to be replicated in appropriately powered clinical trials that include critical subjective and objective outcomes as well as longer-term follow-up for both effectiveness and safety.

Vaginal laxity/pre-prolapse

Vaginal laxity is defined as the symptom of excessive vaginal looseness.16 Also referred to as “pre-prolapse,” this subjective symptom generally refers to a widened vaginal opening (genital hiatus) but with pelvic organ prolapse that is within the vagina or hymen.17 Notably, the definition is ambiguous, and rigorous clinical data based on validated outcomes and prolapse grading are lacking.

Krychman and colleagues conducted the first randomized controlled study comparing monopolar radiofrequency at the vaginal introitus with sham therapy for vaginal laxity in 174 premenopausal women, known as the VIVEVE I trial.18 The primary outcome, the proportion of women reporting no vaginal laxity at 6 months after treatment, was assessed using a vaginal laxity questionnaire, a 7-point rating scale for laxity or tightness ranging from very loose to very tight. With a single radiofrequency treatment, 43.5% of the active group and 19.6% (P = .002) of the sham group obtained the primary outcome.

There were also statistically significant improvements in overall sexual function and decreased sexual distress. The adjusted odds ratio (OR, 3.39; 95% confidence interval, 1.54–7.45) showed that the likelihood of no vaginal laxity at 6 months was more than 3 times greater for women who received the active treatment compared with those who received sham treatment. Adverse events were mild, resolved spontaneously, and were similar in the 2 groups.

Continue to: Outlook for energy-based...

Outlook for energy-based therapies: Cautiously optimistic

Preliminary outcome data on the use of energy-based therapies for female genital cosmetic surgery is largely positive for the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy, but some case series suggest the potential for scarring, burning, and inefficacy. This prompted the FDA to send “It has come to our attention” letters to a number of device manufacturers in 2018.6

Supportive evidence is weak. Early data are encouraging regarding fractionated laser therapy for the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy and stress UI and radiofrequency wand therapy for vaginal laxity and stress UI. Unfortunately, the level of evidence to support wide use of these technologies for all pelvic floor disorders is weak. A recent committee opinion from the International Urogynecology Association noted that only 8 studies (1 randomized trial and 7 observational studies) on these conditions fulfilled the criteria of good quality.19 The International Continence Society and the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disorders recently published a best practice consensus document declaring laser and energy-based treatments in gynecology and urology to be largely experimental.20

Questions persist. Knowledge gaps exist, and recommendations related to subspecialty training—who should perform these procedures (gynecologists, plastic surgeons, urologists, dermatologists, family practitioners) and the level of training needed to safely perform them—are lacking. Patient selection and physician knowledge and experience related to female genital anatomy, female sexual function and dysfunction, multidisciplinary treatment options for various pelvic support problems and UI, as well as psychologic screening for body dysmorphic disorders, need to be considered in terms of treating both the functional and aesthetic aspects related to cosmetic and reconstructive gynecologic surgery.

Special considerations. The use of energy-based therapies in special populations, such as survivors of breast cancer or other gynecologic cancers, as well as women undergoing chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and hormonal manipulation (particularly with antiestrogenic SERMs and aromatase inhibitors) has not been adequately evaluated. A discussion of the risks, benefits, alternatives, and limited long-term outcome data for energy-based therapies in cancer survivors, as for all patients, must be included for adequate informed consent prior to undertaking these treatments.

Guidelines for appropriate tissue priming, laser settings, and concomitant energy-based technology with local hormone treatment (also known as laser-augmented drug delivery) need to be developed. Comparative long-term studies are needed to determine the safety and effectiveness of these technologies.

Caution advised. Given the lack of long-term safety and effectiveness data on energy-based therapies for the vague indications of vaginal laxity, and even for the well-defined conditions of stress UI and vulvovaginal atrophy, clinicians should exercise caution before promoting treatment, which can be expensive and is not without potential complications, such as vaginal pain, adhesive agglutination, and persistent dryness and dyspareunia.21

Fortunately, many randomized trials on various energy-based devices for gynecologic indications (GSM, stress UI, vaginal laxity, lichen sclerosus) are underway, and results from these studies will help inform future clinical practice and guideline development.

Energy-based therapy use in gynecology dates back to the early 1970s, when ablative carbon dioxide (C02) lasers were employed to treat cervical erosions.1 Soon after, reports were published on laser treatment for diethylstilbestrol-associated vaginal adenosis, laser laparoscopy for adhesiolysis, laser hysteroscopy, and laser genital wart ablation.2 Starting around 2011, the first articles were published on the use of fractional C02 laser treatment for vulvovaginal atrophy.3,4 Use of laser and light-based therapies to treat “vaginal rejuvenation” is now increasing at an annual rate of 26%. In a few years, North America is expected to be the largest market for vaginal laser rejuvenation. In 2016, more than 500,000 feminine rejuvenation procedures were performed in the United States, and it is estimated that more than 27,000 energy-based devices will be in operation by 2021.5

Clearly, there is considerable public interest and intrigue in office-based female genital cosmetic procedures. In 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration contacted 7 manufacturers of energy-based devices to request revision and clarification for marketing of these devices, since these technologies are neither cleared nor approved for cosmetic vulvovaginal conditions.6 The companies responded within 30 days.

In this article, we appraise the existing literature regarding the mechanism of action of energy-based therapies used in gynecology and review outcomes of their use in female genital cosmetic surgery.

Laser technology devices and how they work

LASER is an acronym for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. Laser devices are composed of 1) an excitable medium (gas, liquid, solid) needed to emit light, 2) an energy source to excite the medium, 3) mirrors to bounce the light back and forth, and 4) a delivery and cooling system (FIGURE 1).

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of all the wavelengths of light, including visible light, radio waves, infrared light, ultraviolet light, x-rays, and gamma rays (FIGURE 2). Most lasers used for the treatment of vulvovaginal disorders, typically C02 and erbium:yttrium aluminum garnet (Er:YAG) lasers, involve the infrared wavelengths.