User login

2019 Update on cervical disease

Cervical cancer rates remain low in the United States, with the incidence having plateaued for decades. And yet, in 2019, more than 13,000 US women will be diagnosed with cervical cancer.1 Globally, in 2018 almost 600,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer2; it is the fourth most frequent cancer in women. This is despite the fact that we have adequate primary and secondary prevention tools available to minimize—and almost eliminate—cervical cancer. We must continue to raise the bar for preventing, screening for, and managing this disease.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines provide a highly effective primary prevention strategy, but we need to improve our ability to identify and diagnose dysplastic lesions prior to the development of cervical cancer. Highly sensitive HPV testing and cytology is a powerful secondary prevention approach that enables us to assess a woman’s risk of having precancerous cells both now and in the near future. These modalities have been very successful in decreasing the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States and other areas with organized screening programs. In low- and middle-income countries, however, access to, availability of, and performance with these modalities is not optimal. Innovative strategies and new technologies are being evaluated to overcome these limitations.

Advances in radiation and surgical technology have enabled us to vastly improve cervical cancer treatment. Women with early-stage cervical cancer are candidates for surgical management, which frequently includes a radical hysterectomy and lymph node dissection. While these surgeries traditionally have been performed via an exploratory laparotomy, minimally invasive techniques (laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgical techniques) have decreased the morbidity with these surgeries. Notable new studies have shed light on the comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive technologies and have shown us that new is not always better.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released its updated cervical cancer screening guidelines. The suggested approach to screening differs from previous recommendations. HPV testing as a primary test (that is, HPV testing alone or followed by cytology) takes the spotlight now, according to the analysis by the Task Force.

In this Update, we highlight important studies published in the past year that address these issues.

Continue to: New tech's potential to identify high-grade...

New tech's potential to identify high-grade cervical dysplasia may be a boon to low-resource settings

Hu L, Bell D, Antani S, et al. An observational study of deep learning and automated evaluation of cervical images for cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;doi:10.1093/jnci/djy225.

When cervical screening tests like cytology and HPV testing show abnormal results, colposcopy often is recommended. The goal of colposcopy is to identify the areas that might harbor a high-grade precancerous lesion or worse. The gold standard in this case, however, is histology, not colposcopic impression, as many studies have shown that colposcopy without biopsies is limited and that performance is improved with more biopsies.3,4

Visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) is an approach used often in low-resource settings where visual impression is the gold standard. However, as with colposcopy, a visual evaluation without histology does not perform well, and often women are overtreated. Many attempts have been made with new technologies to overcome the limitations of time, cost, and workforce required for cytology and histology services. New disruptive technologies may be able to surmount human limitations and improve on not only VIA but also the need for histology.

Novel technology uses images to develop algorithm with predictive ability

In a recent observational study, Hu and colleagues used images that were collected during a large population study in Guanacaste, Costa Rica.5 More than 9,000 women were followed for up to 7 years, and cervical photographs (cervigrams) were obtained. Well-annotated histopathology results were obtained for women with abnormal screening, and 279 women had a high-grade dysplastic lesion or cancer.

Cervigrams from women with high-grade lesions and matched controls were collected, and a deep learning-based algorithm using artificial intelligence technology was developed using 70% of the images. The remaining 30% of images were used as a validation set to test the algorithm's ability to "predict" high-grade dysplasia without knowing the final result.

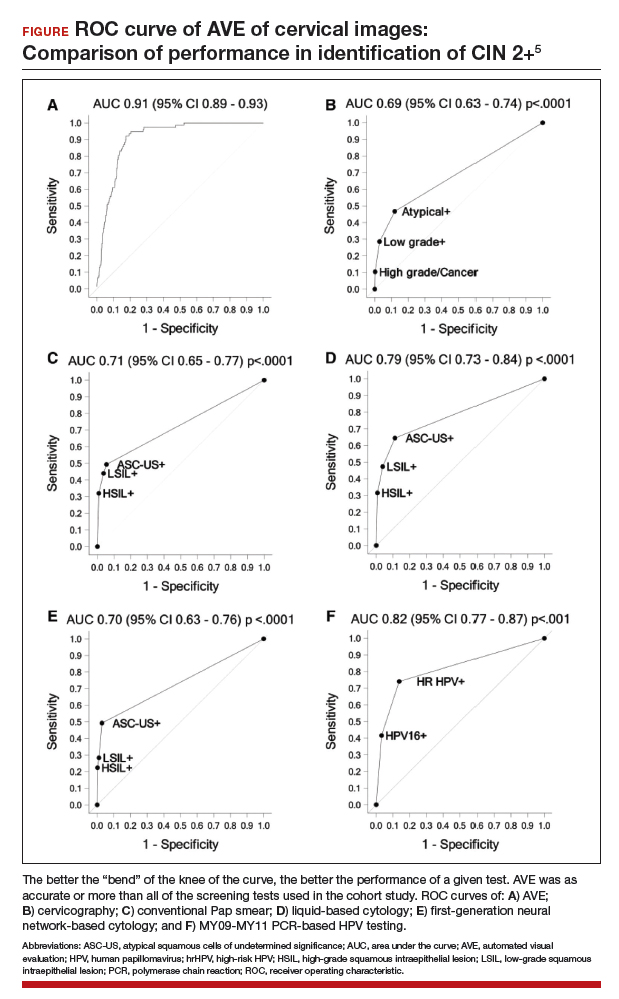

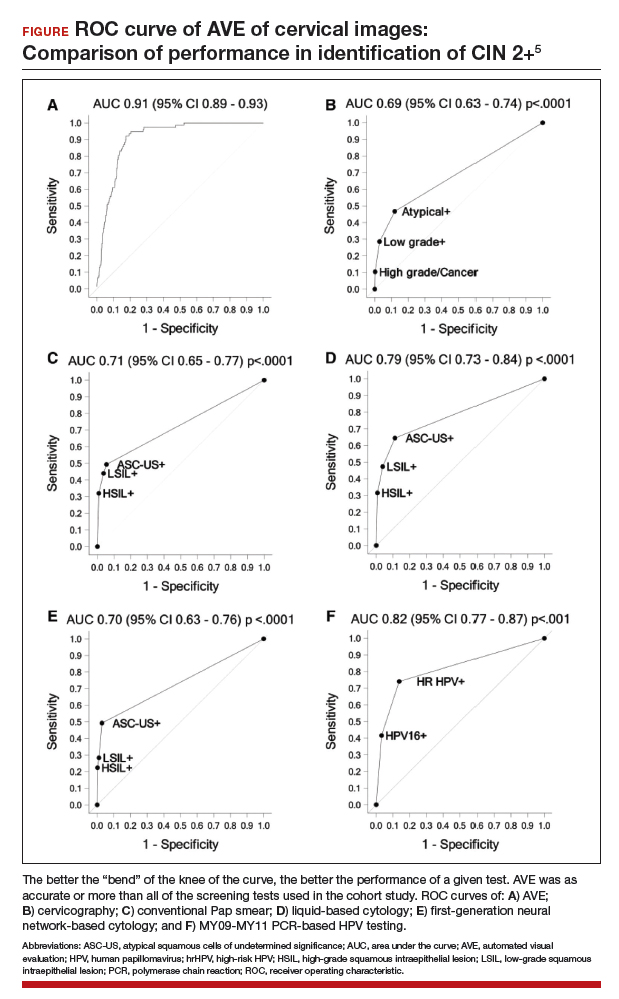

Findings. Termed automated visual evaluation (AVE), this new technology demonstrated a very accurate ability to identify high-grade dysplasia or worse, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.91 from merely a cervicogram (FIGURE). This outperformed conventional Pap smears (AUC, 0.71), liquid-based cytology (AUC, 0.79) and, surprisingly, highly sensitive HPV testing (AUC, 0.82) in women in the prime of their screening ages (>25 years of age).

Colposcopy remains the gold standard for evaluating abnormal cervical cancer screening tests in the United States. But can we do better for our patients using new technologies like AVE? If validated in large-scale trials, AVE has the potential to revolutionize cervical cancer screening in low-resource settings where follow-up and adequate histology services are limited or nonexistent. Future large studies are necessary to evaluate the role of AVE alone versus in combination with other diagnostic testing (such as HPV testing) to detect cervical lesions globally.

Continue to: Data offer persuasive evidence...

Data offer persuasive evidence to abandon minimally invasive surgery in management of early-stage cervical cancer

Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

Over the past decade, gynecologic cancer surgery has shifted from what routinely were open procedures to the adoption of minimally invasive techniques. Recently, a large, well-designed prospective study and a large retrospective study both demonstrated worse outcomes with minimally invasive radical hysterectomy (MIRH) as compared with traditional open radical abdominal hysterectomy (RAH). These 2 landmark studies, initially presented at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology's 2018 annual meeting and later published in the New England Journal of Medicine, have really affected the gynecologic oncology community.

Shorter overall survival in women who had MIRH

Melamed and colleagues conducted a large, retrospective US-based study to evaluate all-cause mortality in women with cervical cancer who underwent MIRH compared with those who had RAH.6 The authors also sought to evaluate national trends in 4-year relative survival rates after minimally invasive surgery was adopted.

The study included 2,461 women who met the inclusion criteria; 49.8% (1,225) underwent MIRH procedures and, of those, 79.8% (978) had robot-assisted laparoscopy. Most women had stage IB1 tumors (88%), and most carcinomas were squamous cell (61%); 40.6% of tumors were less than 2 cm in size. There were no differences between the 2 groups with respect to rates of positive parametria, surgical margins, and lymph node involvement. Administration of adjuvant therapy, in those who qualified, was also similar between groups.

Results. At a median follow-up of 45 months, 94 deaths occurred in the minimally invasive group and 70 in the open surgery group. The risk of death at 4 years was 9.1% in the minimally invasive group versus 5.3% in the open surgery group, with a 65% higher risk of death from any cause, which was highly statistically significant.

Prospective trial showed MIRH was associated with lower survival rates

From 2008 to 2017, Ramirez and colleagues conducted a phase 3, multicenter, randomized controlled trial to prospectively establish the noninferiority of MIRH compared with RAH.7 The study included 631 women from 33 centers. The prespecified expected disease-free survival rate was 90% at 4.5 years.

To be included as a site, centers were required to submit details from 10 minimally invasive cases as well as 2 unedited videos for review by the trial management committee. In contrast to Melamed and colleagues' retrospective study, of the 319 procedures that were classified as minimally invasive, only 15.6% were robotically assisted. Similarly, most women had stage IB1 tumors (91.9%), and most were squamous cell carcinomas (67%). There were also no differences in the postoperative pathology findings or the need for adjuvant therapy administered between groups. The median follow-up was 2.5 years.

Results. At that time there were 27 recurrences in the MIRH group and 7 in the RAH group; there were also 19 deaths after MIRH and 3 after RAH. Disease-free survival at 4.5 years was 86% with MIRH versus 96.5% with RAH. Reported 3-year disease-free survival and overall survival were also significantily lower in the minimally invasive subgroup (91.2% vs 97.1%, 93.8% vs 99.0%, respectively).

Study limitations. Criticisms of this trial are that noninferiority could not be declared; in addition, the investigators were unable to complete enrollment secondary to early enrollment termination after the data and safety monitoring board raised survival concerns.

Many argue that subgroup analyses suggest a lower risk of poor outcomes in patients with smaller tumors (<2 cm); however, it is critical to note that this study was not powered to detect these differences.

The evidence is compelling and demonstrates potentially worse disease-related outcomes using MIRH when compared to traditional RAH with respect to cervical cancer recurrence, rates of death, and disease-free and overall survival. Several hypotheses have been proposed, and future research is needed to elucidate the differences in variables responsible for the outcomes demonstrated in these studies. Although there has been no ban on robot-assisted surgical devices or traditional minimally invasive techniques, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network has updated its recommendations to include careful counseling of patients who require a surgical approach for the management of early-stage cervical cancer.

Continue to: USPSTF updated guidance on cervical cancer screening...

USPSTF updated guidance on cervical cancer screening

Melnikow J, Henderson JT, Burda BU, et al. Screening for cervical cancer with high-risk human papillomavirus testing: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:687-705.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

Past guidelines for cervical cancer screening have included testing for high-risk HPV (hrHPV) as a cotest with cytology or for triage of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) in women aged 30 to 65 years.8 The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology, with other stakeholder organizations, issued interim guidance for primary HPV testing--that is, HPV test first and, in the case of non-16/18 hrHPV types, cytology as a triage. The most recent evidence report and systematic review by Melnikow and colleagues for the USPSTF offers an in-depth analysis of risks, benefits, harms, and value of cotesting and other management strategies.9

Focus on screening effectiveness

Large trials of cotesting were conducted in women aged 25 to 65.10-13 These studies all consistently showed that primary hrHPV screening led to a statistically significant increased detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3+ in the initial round of screening, with a relative risk of detecting CIN 3+ ranging from 1.61 to 7.46 compared with cytology alone.

Four additional studies compared cotesting with conventional cytology for the detection of CIN 3+. None of these trials demonstrated a significantly higher detection rate of CIN 3+ with cotesting compared with conventional cytology testing alone. Notably, the studies reviewed were performed in European countries that had organized screening programs in place and a nationalized health care system. Thus, these data may not be as applicable to women in the United States, particularly to women who have limited health care access.

Risks of screening

In the same studies reviewed for screening effectiveness, the investigators found that overall, screening with hrHPV primary or cotesting was associated with more false-positive results and higher colposcopy rates. Women screened with hrHPV alone had a 7.9% referral rate to colposcopy, while those screened with cytology had a 2.8% referral rate to colposcopy. Similarly, the rate of biopsy was higher in the hrHPV-only group (3.2% vs 1.3%).

Overall, while cotesting might have some improvement in performance compared with hrHPV as a single modality, there might be risks of overreferral to colposcopy and overtreatment with additional cytology over hrHPV testing alone.

This evidence review also included an analysis of more potential harms. Very limited evidence suggests that positive hrHPV test results may be associated with greater psychological harm, including decreased sexual satisfaction, increased anxiety and distress, and worse feelings about sexual partners, than abnormal cytology results. These were assessed, however, 1 to 2 weeks after the test results were provided to the patients, and long-term assessment was not done.

New recommendations from the USPSTF

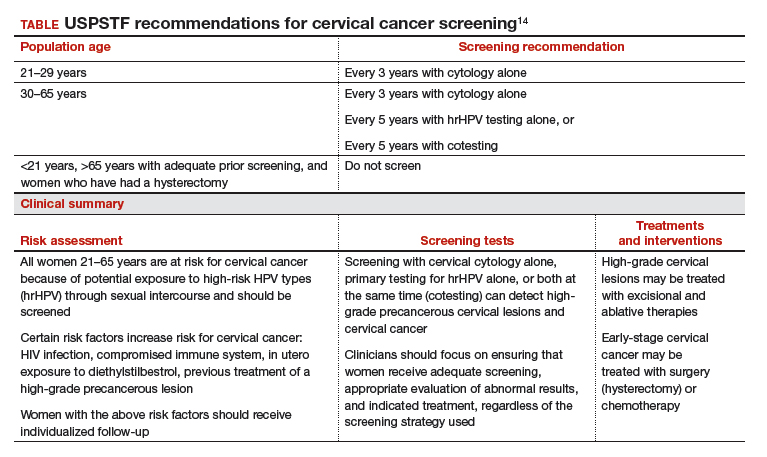

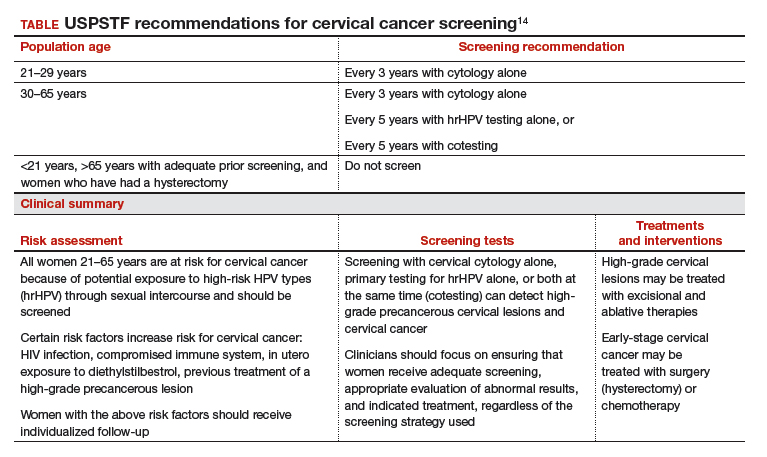

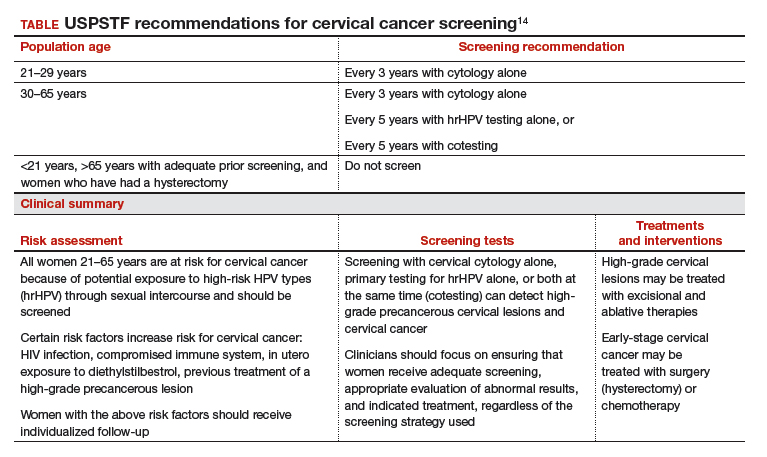

Based on these data, the USPSTF issued new recommendations regarding screening (TABLE).14 For women aged 21 to 29, cytology alone should be used for screening every 3 years. Women aged 30 to 65 can be screened with cytology alone every 3 years, with hrHPV testing alone every 5 years, or with cotesting every 5 years.

Primary screening with hrHPV is more effective in diagnosing a CIN 3+ than cytology alone. Cotesting with cytology and hrHPV testing appears to have limited performance improvement, with potential harm, compared with hrHPV testing alone in diagnosing CIN 3+. The Task Force recommendation is hrHPV testing alone or cotesting every 5 years.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34.

- World Health Organization website. Cervical cancer. https://www.who.int/cancer/prevention/diagnosis-screening/cervical-cancer/en/. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Wentzensen N, Walker JL, Gold MA, et al. Multiple biopsies and detection of cervical cancer precursors at colposcopy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:83-89.

- Gage JC, Hanson VW, Abbey K, et al. Number of cervical biopsies and sensitivity of colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:264-272.

- Hu L, Bell D, Antani S, et al. An observational study of deep learning and automated evaluation of cervical images for cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;doi:10.1093/jnci/djy225.

- Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

- Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al; ACS-ASCCP-ASCP Cervical Cancer Guideline Committee. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:147-172.

- Melnikow J, Henderson JT, Burda BU, et al. Screening for cervical cancer with high-risk human papillomavirus testing: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:687-705.

- Canfell K, Caruana M, Gebski V, et al. Cervical screening with primary HPV testing or cytology in a population of women in which those aged 33 years or younger had previously been offered HPV vaccination: results of the Compass pilot randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002388. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002388.

- Leinonen MK, Nieminen P, Lonnberg S, et al. Detection rates of precancerous and cancerous cervical lesions within one screening round of primary human papillomavirus DNA testing: prospective randomised trial in Finland. BMJ. 2012;345:e7789.

- Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52.

- Ronco G, Fioprgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al; New Technologies for Cervical Cancer screening (NTCC) Working Group. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:249-257.

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

Cervical cancer rates remain low in the United States, with the incidence having plateaued for decades. And yet, in 2019, more than 13,000 US women will be diagnosed with cervical cancer.1 Globally, in 2018 almost 600,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer2; it is the fourth most frequent cancer in women. This is despite the fact that we have adequate primary and secondary prevention tools available to minimize—and almost eliminate—cervical cancer. We must continue to raise the bar for preventing, screening for, and managing this disease.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines provide a highly effective primary prevention strategy, but we need to improve our ability to identify and diagnose dysplastic lesions prior to the development of cervical cancer. Highly sensitive HPV testing and cytology is a powerful secondary prevention approach that enables us to assess a woman’s risk of having precancerous cells both now and in the near future. These modalities have been very successful in decreasing the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States and other areas with organized screening programs. In low- and middle-income countries, however, access to, availability of, and performance with these modalities is not optimal. Innovative strategies and new technologies are being evaluated to overcome these limitations.

Advances in radiation and surgical technology have enabled us to vastly improve cervical cancer treatment. Women with early-stage cervical cancer are candidates for surgical management, which frequently includes a radical hysterectomy and lymph node dissection. While these surgeries traditionally have been performed via an exploratory laparotomy, minimally invasive techniques (laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgical techniques) have decreased the morbidity with these surgeries. Notable new studies have shed light on the comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive technologies and have shown us that new is not always better.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released its updated cervical cancer screening guidelines. The suggested approach to screening differs from previous recommendations. HPV testing as a primary test (that is, HPV testing alone or followed by cytology) takes the spotlight now, according to the analysis by the Task Force.

In this Update, we highlight important studies published in the past year that address these issues.

Continue to: New tech's potential to identify high-grade...

New tech's potential to identify high-grade cervical dysplasia may be a boon to low-resource settings

Hu L, Bell D, Antani S, et al. An observational study of deep learning and automated evaluation of cervical images for cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;doi:10.1093/jnci/djy225.

When cervical screening tests like cytology and HPV testing show abnormal results, colposcopy often is recommended. The goal of colposcopy is to identify the areas that might harbor a high-grade precancerous lesion or worse. The gold standard in this case, however, is histology, not colposcopic impression, as many studies have shown that colposcopy without biopsies is limited and that performance is improved with more biopsies.3,4

Visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) is an approach used often in low-resource settings where visual impression is the gold standard. However, as with colposcopy, a visual evaluation without histology does not perform well, and often women are overtreated. Many attempts have been made with new technologies to overcome the limitations of time, cost, and workforce required for cytology and histology services. New disruptive technologies may be able to surmount human limitations and improve on not only VIA but also the need for histology.

Novel technology uses images to develop algorithm with predictive ability

In a recent observational study, Hu and colleagues used images that were collected during a large population study in Guanacaste, Costa Rica.5 More than 9,000 women were followed for up to 7 years, and cervical photographs (cervigrams) were obtained. Well-annotated histopathology results were obtained for women with abnormal screening, and 279 women had a high-grade dysplastic lesion or cancer.

Cervigrams from women with high-grade lesions and matched controls were collected, and a deep learning-based algorithm using artificial intelligence technology was developed using 70% of the images. The remaining 30% of images were used as a validation set to test the algorithm's ability to "predict" high-grade dysplasia without knowing the final result.

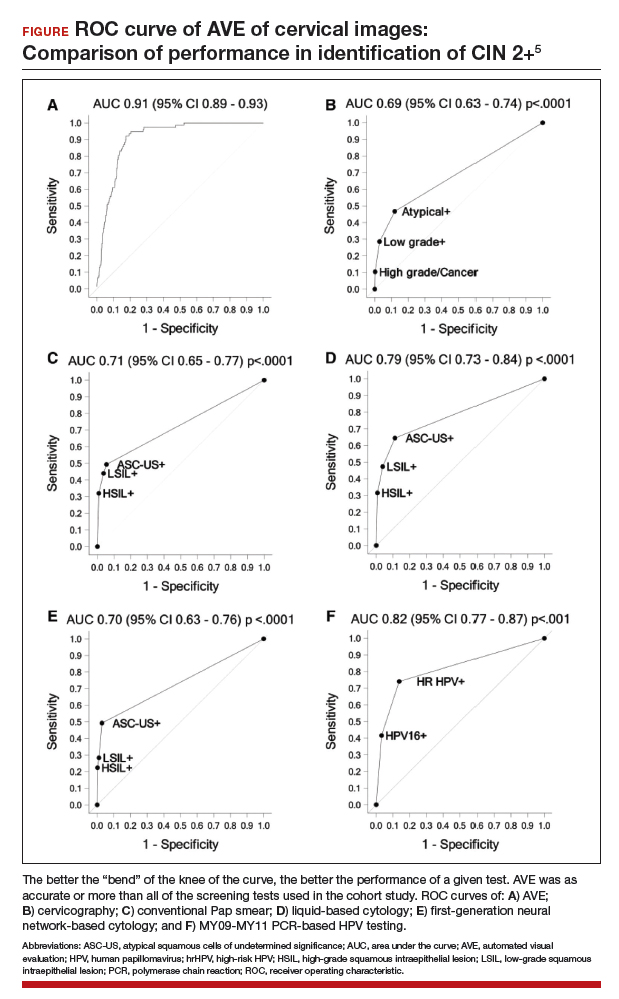

Findings. Termed automated visual evaluation (AVE), this new technology demonstrated a very accurate ability to identify high-grade dysplasia or worse, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.91 from merely a cervicogram (FIGURE). This outperformed conventional Pap smears (AUC, 0.71), liquid-based cytology (AUC, 0.79) and, surprisingly, highly sensitive HPV testing (AUC, 0.82) in women in the prime of their screening ages (>25 years of age).

Colposcopy remains the gold standard for evaluating abnormal cervical cancer screening tests in the United States. But can we do better for our patients using new technologies like AVE? If validated in large-scale trials, AVE has the potential to revolutionize cervical cancer screening in low-resource settings where follow-up and adequate histology services are limited or nonexistent. Future large studies are necessary to evaluate the role of AVE alone versus in combination with other diagnostic testing (such as HPV testing) to detect cervical lesions globally.

Continue to: Data offer persuasive evidence...

Data offer persuasive evidence to abandon minimally invasive surgery in management of early-stage cervical cancer

Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

Over the past decade, gynecologic cancer surgery has shifted from what routinely were open procedures to the adoption of minimally invasive techniques. Recently, a large, well-designed prospective study and a large retrospective study both demonstrated worse outcomes with minimally invasive radical hysterectomy (MIRH) as compared with traditional open radical abdominal hysterectomy (RAH). These 2 landmark studies, initially presented at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology's 2018 annual meeting and later published in the New England Journal of Medicine, have really affected the gynecologic oncology community.

Shorter overall survival in women who had MIRH

Melamed and colleagues conducted a large, retrospective US-based study to evaluate all-cause mortality in women with cervical cancer who underwent MIRH compared with those who had RAH.6 The authors also sought to evaluate national trends in 4-year relative survival rates after minimally invasive surgery was adopted.

The study included 2,461 women who met the inclusion criteria; 49.8% (1,225) underwent MIRH procedures and, of those, 79.8% (978) had robot-assisted laparoscopy. Most women had stage IB1 tumors (88%), and most carcinomas were squamous cell (61%); 40.6% of tumors were less than 2 cm in size. There were no differences between the 2 groups with respect to rates of positive parametria, surgical margins, and lymph node involvement. Administration of adjuvant therapy, in those who qualified, was also similar between groups.

Results. At a median follow-up of 45 months, 94 deaths occurred in the minimally invasive group and 70 in the open surgery group. The risk of death at 4 years was 9.1% in the minimally invasive group versus 5.3% in the open surgery group, with a 65% higher risk of death from any cause, which was highly statistically significant.

Prospective trial showed MIRH was associated with lower survival rates

From 2008 to 2017, Ramirez and colleagues conducted a phase 3, multicenter, randomized controlled trial to prospectively establish the noninferiority of MIRH compared with RAH.7 The study included 631 women from 33 centers. The prespecified expected disease-free survival rate was 90% at 4.5 years.

To be included as a site, centers were required to submit details from 10 minimally invasive cases as well as 2 unedited videos for review by the trial management committee. In contrast to Melamed and colleagues' retrospective study, of the 319 procedures that were classified as minimally invasive, only 15.6% were robotically assisted. Similarly, most women had stage IB1 tumors (91.9%), and most were squamous cell carcinomas (67%). There were also no differences in the postoperative pathology findings or the need for adjuvant therapy administered between groups. The median follow-up was 2.5 years.

Results. At that time there were 27 recurrences in the MIRH group and 7 in the RAH group; there were also 19 deaths after MIRH and 3 after RAH. Disease-free survival at 4.5 years was 86% with MIRH versus 96.5% with RAH. Reported 3-year disease-free survival and overall survival were also significantily lower in the minimally invasive subgroup (91.2% vs 97.1%, 93.8% vs 99.0%, respectively).

Study limitations. Criticisms of this trial are that noninferiority could not be declared; in addition, the investigators were unable to complete enrollment secondary to early enrollment termination after the data and safety monitoring board raised survival concerns.

Many argue that subgroup analyses suggest a lower risk of poor outcomes in patients with smaller tumors (<2 cm); however, it is critical to note that this study was not powered to detect these differences.

The evidence is compelling and demonstrates potentially worse disease-related outcomes using MIRH when compared to traditional RAH with respect to cervical cancer recurrence, rates of death, and disease-free and overall survival. Several hypotheses have been proposed, and future research is needed to elucidate the differences in variables responsible for the outcomes demonstrated in these studies. Although there has been no ban on robot-assisted surgical devices or traditional minimally invasive techniques, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network has updated its recommendations to include careful counseling of patients who require a surgical approach for the management of early-stage cervical cancer.

Continue to: USPSTF updated guidance on cervical cancer screening...

USPSTF updated guidance on cervical cancer screening

Melnikow J, Henderson JT, Burda BU, et al. Screening for cervical cancer with high-risk human papillomavirus testing: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:687-705.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

Past guidelines for cervical cancer screening have included testing for high-risk HPV (hrHPV) as a cotest with cytology or for triage of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) in women aged 30 to 65 years.8 The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology, with other stakeholder organizations, issued interim guidance for primary HPV testing--that is, HPV test first and, in the case of non-16/18 hrHPV types, cytology as a triage. The most recent evidence report and systematic review by Melnikow and colleagues for the USPSTF offers an in-depth analysis of risks, benefits, harms, and value of cotesting and other management strategies.9

Focus on screening effectiveness

Large trials of cotesting were conducted in women aged 25 to 65.10-13 These studies all consistently showed that primary hrHPV screening led to a statistically significant increased detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3+ in the initial round of screening, with a relative risk of detecting CIN 3+ ranging from 1.61 to 7.46 compared with cytology alone.

Four additional studies compared cotesting with conventional cytology for the detection of CIN 3+. None of these trials demonstrated a significantly higher detection rate of CIN 3+ with cotesting compared with conventional cytology testing alone. Notably, the studies reviewed were performed in European countries that had organized screening programs in place and a nationalized health care system. Thus, these data may not be as applicable to women in the United States, particularly to women who have limited health care access.

Risks of screening

In the same studies reviewed for screening effectiveness, the investigators found that overall, screening with hrHPV primary or cotesting was associated with more false-positive results and higher colposcopy rates. Women screened with hrHPV alone had a 7.9% referral rate to colposcopy, while those screened with cytology had a 2.8% referral rate to colposcopy. Similarly, the rate of biopsy was higher in the hrHPV-only group (3.2% vs 1.3%).

Overall, while cotesting might have some improvement in performance compared with hrHPV as a single modality, there might be risks of overreferral to colposcopy and overtreatment with additional cytology over hrHPV testing alone.

This evidence review also included an analysis of more potential harms. Very limited evidence suggests that positive hrHPV test results may be associated with greater psychological harm, including decreased sexual satisfaction, increased anxiety and distress, and worse feelings about sexual partners, than abnormal cytology results. These were assessed, however, 1 to 2 weeks after the test results were provided to the patients, and long-term assessment was not done.

New recommendations from the USPSTF

Based on these data, the USPSTF issued new recommendations regarding screening (TABLE).14 For women aged 21 to 29, cytology alone should be used for screening every 3 years. Women aged 30 to 65 can be screened with cytology alone every 3 years, with hrHPV testing alone every 5 years, or with cotesting every 5 years.

Primary screening with hrHPV is more effective in diagnosing a CIN 3+ than cytology alone. Cotesting with cytology and hrHPV testing appears to have limited performance improvement, with potential harm, compared with hrHPV testing alone in diagnosing CIN 3+. The Task Force recommendation is hrHPV testing alone or cotesting every 5 years.

Cervical cancer rates remain low in the United States, with the incidence having plateaued for decades. And yet, in 2019, more than 13,000 US women will be diagnosed with cervical cancer.1 Globally, in 2018 almost 600,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer2; it is the fourth most frequent cancer in women. This is despite the fact that we have adequate primary and secondary prevention tools available to minimize—and almost eliminate—cervical cancer. We must continue to raise the bar for preventing, screening for, and managing this disease.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines provide a highly effective primary prevention strategy, but we need to improve our ability to identify and diagnose dysplastic lesions prior to the development of cervical cancer. Highly sensitive HPV testing and cytology is a powerful secondary prevention approach that enables us to assess a woman’s risk of having precancerous cells both now and in the near future. These modalities have been very successful in decreasing the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States and other areas with organized screening programs. In low- and middle-income countries, however, access to, availability of, and performance with these modalities is not optimal. Innovative strategies and new technologies are being evaluated to overcome these limitations.

Advances in radiation and surgical technology have enabled us to vastly improve cervical cancer treatment. Women with early-stage cervical cancer are candidates for surgical management, which frequently includes a radical hysterectomy and lymph node dissection. While these surgeries traditionally have been performed via an exploratory laparotomy, minimally invasive techniques (laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgical techniques) have decreased the morbidity with these surgeries. Notable new studies have shed light on the comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive technologies and have shown us that new is not always better.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released its updated cervical cancer screening guidelines. The suggested approach to screening differs from previous recommendations. HPV testing as a primary test (that is, HPV testing alone or followed by cytology) takes the spotlight now, according to the analysis by the Task Force.

In this Update, we highlight important studies published in the past year that address these issues.

Continue to: New tech's potential to identify high-grade...

New tech's potential to identify high-grade cervical dysplasia may be a boon to low-resource settings

Hu L, Bell D, Antani S, et al. An observational study of deep learning and automated evaluation of cervical images for cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;doi:10.1093/jnci/djy225.

When cervical screening tests like cytology and HPV testing show abnormal results, colposcopy often is recommended. The goal of colposcopy is to identify the areas that might harbor a high-grade precancerous lesion or worse. The gold standard in this case, however, is histology, not colposcopic impression, as many studies have shown that colposcopy without biopsies is limited and that performance is improved with more biopsies.3,4

Visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) is an approach used often in low-resource settings where visual impression is the gold standard. However, as with colposcopy, a visual evaluation without histology does not perform well, and often women are overtreated. Many attempts have been made with new technologies to overcome the limitations of time, cost, and workforce required for cytology and histology services. New disruptive technologies may be able to surmount human limitations and improve on not only VIA but also the need for histology.

Novel technology uses images to develop algorithm with predictive ability

In a recent observational study, Hu and colleagues used images that were collected during a large population study in Guanacaste, Costa Rica.5 More than 9,000 women were followed for up to 7 years, and cervical photographs (cervigrams) were obtained. Well-annotated histopathology results were obtained for women with abnormal screening, and 279 women had a high-grade dysplastic lesion or cancer.

Cervigrams from women with high-grade lesions and matched controls were collected, and a deep learning-based algorithm using artificial intelligence technology was developed using 70% of the images. The remaining 30% of images were used as a validation set to test the algorithm's ability to "predict" high-grade dysplasia without knowing the final result.

Findings. Termed automated visual evaluation (AVE), this new technology demonstrated a very accurate ability to identify high-grade dysplasia or worse, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.91 from merely a cervicogram (FIGURE). This outperformed conventional Pap smears (AUC, 0.71), liquid-based cytology (AUC, 0.79) and, surprisingly, highly sensitive HPV testing (AUC, 0.82) in women in the prime of their screening ages (>25 years of age).

Colposcopy remains the gold standard for evaluating abnormal cervical cancer screening tests in the United States. But can we do better for our patients using new technologies like AVE? If validated in large-scale trials, AVE has the potential to revolutionize cervical cancer screening in low-resource settings where follow-up and adequate histology services are limited or nonexistent. Future large studies are necessary to evaluate the role of AVE alone versus in combination with other diagnostic testing (such as HPV testing) to detect cervical lesions globally.

Continue to: Data offer persuasive evidence...

Data offer persuasive evidence to abandon minimally invasive surgery in management of early-stage cervical cancer

Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

Over the past decade, gynecologic cancer surgery has shifted from what routinely were open procedures to the adoption of minimally invasive techniques. Recently, a large, well-designed prospective study and a large retrospective study both demonstrated worse outcomes with minimally invasive radical hysterectomy (MIRH) as compared with traditional open radical abdominal hysterectomy (RAH). These 2 landmark studies, initially presented at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology's 2018 annual meeting and later published in the New England Journal of Medicine, have really affected the gynecologic oncology community.

Shorter overall survival in women who had MIRH

Melamed and colleagues conducted a large, retrospective US-based study to evaluate all-cause mortality in women with cervical cancer who underwent MIRH compared with those who had RAH.6 The authors also sought to evaluate national trends in 4-year relative survival rates after minimally invasive surgery was adopted.

The study included 2,461 women who met the inclusion criteria; 49.8% (1,225) underwent MIRH procedures and, of those, 79.8% (978) had robot-assisted laparoscopy. Most women had stage IB1 tumors (88%), and most carcinomas were squamous cell (61%); 40.6% of tumors were less than 2 cm in size. There were no differences between the 2 groups with respect to rates of positive parametria, surgical margins, and lymph node involvement. Administration of adjuvant therapy, in those who qualified, was also similar between groups.

Results. At a median follow-up of 45 months, 94 deaths occurred in the minimally invasive group and 70 in the open surgery group. The risk of death at 4 years was 9.1% in the minimally invasive group versus 5.3% in the open surgery group, with a 65% higher risk of death from any cause, which was highly statistically significant.

Prospective trial showed MIRH was associated with lower survival rates

From 2008 to 2017, Ramirez and colleagues conducted a phase 3, multicenter, randomized controlled trial to prospectively establish the noninferiority of MIRH compared with RAH.7 The study included 631 women from 33 centers. The prespecified expected disease-free survival rate was 90% at 4.5 years.

To be included as a site, centers were required to submit details from 10 minimally invasive cases as well as 2 unedited videos for review by the trial management committee. In contrast to Melamed and colleagues' retrospective study, of the 319 procedures that were classified as minimally invasive, only 15.6% were robotically assisted. Similarly, most women had stage IB1 tumors (91.9%), and most were squamous cell carcinomas (67%). There were also no differences in the postoperative pathology findings or the need for adjuvant therapy administered between groups. The median follow-up was 2.5 years.

Results. At that time there were 27 recurrences in the MIRH group and 7 in the RAH group; there were also 19 deaths after MIRH and 3 after RAH. Disease-free survival at 4.5 years was 86% with MIRH versus 96.5% with RAH. Reported 3-year disease-free survival and overall survival were also significantily lower in the minimally invasive subgroup (91.2% vs 97.1%, 93.8% vs 99.0%, respectively).

Study limitations. Criticisms of this trial are that noninferiority could not be declared; in addition, the investigators were unable to complete enrollment secondary to early enrollment termination after the data and safety monitoring board raised survival concerns.

Many argue that subgroup analyses suggest a lower risk of poor outcomes in patients with smaller tumors (<2 cm); however, it is critical to note that this study was not powered to detect these differences.

The evidence is compelling and demonstrates potentially worse disease-related outcomes using MIRH when compared to traditional RAH with respect to cervical cancer recurrence, rates of death, and disease-free and overall survival. Several hypotheses have been proposed, and future research is needed to elucidate the differences in variables responsible for the outcomes demonstrated in these studies. Although there has been no ban on robot-assisted surgical devices or traditional minimally invasive techniques, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network has updated its recommendations to include careful counseling of patients who require a surgical approach for the management of early-stage cervical cancer.

Continue to: USPSTF updated guidance on cervical cancer screening...

USPSTF updated guidance on cervical cancer screening

Melnikow J, Henderson JT, Burda BU, et al. Screening for cervical cancer with high-risk human papillomavirus testing: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:687-705.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

Past guidelines for cervical cancer screening have included testing for high-risk HPV (hrHPV) as a cotest with cytology or for triage of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) in women aged 30 to 65 years.8 The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology, with other stakeholder organizations, issued interim guidance for primary HPV testing--that is, HPV test first and, in the case of non-16/18 hrHPV types, cytology as a triage. The most recent evidence report and systematic review by Melnikow and colleagues for the USPSTF offers an in-depth analysis of risks, benefits, harms, and value of cotesting and other management strategies.9

Focus on screening effectiveness

Large trials of cotesting were conducted in women aged 25 to 65.10-13 These studies all consistently showed that primary hrHPV screening led to a statistically significant increased detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3+ in the initial round of screening, with a relative risk of detecting CIN 3+ ranging from 1.61 to 7.46 compared with cytology alone.

Four additional studies compared cotesting with conventional cytology for the detection of CIN 3+. None of these trials demonstrated a significantly higher detection rate of CIN 3+ with cotesting compared with conventional cytology testing alone. Notably, the studies reviewed were performed in European countries that had organized screening programs in place and a nationalized health care system. Thus, these data may not be as applicable to women in the United States, particularly to women who have limited health care access.

Risks of screening

In the same studies reviewed for screening effectiveness, the investigators found that overall, screening with hrHPV primary or cotesting was associated with more false-positive results and higher colposcopy rates. Women screened with hrHPV alone had a 7.9% referral rate to colposcopy, while those screened with cytology had a 2.8% referral rate to colposcopy. Similarly, the rate of biopsy was higher in the hrHPV-only group (3.2% vs 1.3%).

Overall, while cotesting might have some improvement in performance compared with hrHPV as a single modality, there might be risks of overreferral to colposcopy and overtreatment with additional cytology over hrHPV testing alone.

This evidence review also included an analysis of more potential harms. Very limited evidence suggests that positive hrHPV test results may be associated with greater psychological harm, including decreased sexual satisfaction, increased anxiety and distress, and worse feelings about sexual partners, than abnormal cytology results. These were assessed, however, 1 to 2 weeks after the test results were provided to the patients, and long-term assessment was not done.

New recommendations from the USPSTF

Based on these data, the USPSTF issued new recommendations regarding screening (TABLE).14 For women aged 21 to 29, cytology alone should be used for screening every 3 years. Women aged 30 to 65 can be screened with cytology alone every 3 years, with hrHPV testing alone every 5 years, or with cotesting every 5 years.

Primary screening with hrHPV is more effective in diagnosing a CIN 3+ than cytology alone. Cotesting with cytology and hrHPV testing appears to have limited performance improvement, with potential harm, compared with hrHPV testing alone in diagnosing CIN 3+. The Task Force recommendation is hrHPV testing alone or cotesting every 5 years.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34.

- World Health Organization website. Cervical cancer. https://www.who.int/cancer/prevention/diagnosis-screening/cervical-cancer/en/. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Wentzensen N, Walker JL, Gold MA, et al. Multiple biopsies and detection of cervical cancer precursors at colposcopy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:83-89.

- Gage JC, Hanson VW, Abbey K, et al. Number of cervical biopsies and sensitivity of colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:264-272.

- Hu L, Bell D, Antani S, et al. An observational study of deep learning and automated evaluation of cervical images for cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;doi:10.1093/jnci/djy225.

- Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

- Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al; ACS-ASCCP-ASCP Cervical Cancer Guideline Committee. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:147-172.

- Melnikow J, Henderson JT, Burda BU, et al. Screening for cervical cancer with high-risk human papillomavirus testing: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:687-705.

- Canfell K, Caruana M, Gebski V, et al. Cervical screening with primary HPV testing or cytology in a population of women in which those aged 33 years or younger had previously been offered HPV vaccination: results of the Compass pilot randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002388. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002388.

- Leinonen MK, Nieminen P, Lonnberg S, et al. Detection rates of precancerous and cancerous cervical lesions within one screening round of primary human papillomavirus DNA testing: prospective randomised trial in Finland. BMJ. 2012;345:e7789.

- Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52.

- Ronco G, Fioprgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al; New Technologies for Cervical Cancer screening (NTCC) Working Group. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:249-257.

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34.

- World Health Organization website. Cervical cancer. https://www.who.int/cancer/prevention/diagnosis-screening/cervical-cancer/en/. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Wentzensen N, Walker JL, Gold MA, et al. Multiple biopsies and detection of cervical cancer precursors at colposcopy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:83-89.

- Gage JC, Hanson VW, Abbey K, et al. Number of cervical biopsies and sensitivity of colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:264-272.

- Hu L, Bell D, Antani S, et al. An observational study of deep learning and automated evaluation of cervical images for cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;doi:10.1093/jnci/djy225.

- Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

- Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al; ACS-ASCCP-ASCP Cervical Cancer Guideline Committee. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:147-172.

- Melnikow J, Henderson JT, Burda BU, et al. Screening for cervical cancer with high-risk human papillomavirus testing: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:687-705.

- Canfell K, Caruana M, Gebski V, et al. Cervical screening with primary HPV testing or cytology in a population of women in which those aged 33 years or younger had previously been offered HPV vaccination: results of the Compass pilot randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002388. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002388.

- Leinonen MK, Nieminen P, Lonnberg S, et al. Detection rates of precancerous and cancerous cervical lesions within one screening round of primary human papillomavirus DNA testing: prospective randomised trial in Finland. BMJ. 2012;345:e7789.

- Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52.

- Ronco G, Fioprgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al; New Technologies for Cervical Cancer screening (NTCC) Working Group. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:249-257.

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

Cluster headache is associated with increased suicidality

Short- and long-term cluster headache disease burden, as well as depressive symptoms, contributes to suicidality, according to research published online Cephalalgia. Development of treatments that reduce the headache-related burden and prevent future bouts could reduce suicidality, said the researchers.

Although cluster headache has been called the “suicide headache,” few studies have examined suicidality in patients with cluster headache. Research by Rozen et al. found that the rate of suicidal attempt among patients was similar to that among the general population. The results have not been replicated, however, and the investigators did not examine whether suicidality varied according to the phases of the disorder.

A prospective, multicenter study

Mi Ji Lee, MD, PhD, clinical assistant professor of neurology at Samsung Medical Center in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues conducted a prospective study to investigate the suicidality associated with cluster headache and the factors associated with increased suicidality in that disorder. The researchers enrolled 193 consecutive patients with cluster headache between September 2016 and August 2018 at 15 hospitals. They examined the patients and used the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and the General Anxiety Disorder–7 item scale (GAD-7) screening tools. During the ictal and interictal phases, the researchers asked the patients whether they had had passive suicidal ideation, active suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, or suicidal attempt. Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues performed univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses to evaluate the factors associated with high ictal suicidality, which was defined as two or more positive responses during the ictal phase. Participants were followed up during the between-bout phase.

The researchers excluded 18 patients from analysis because they were between bouts at enrollment. The mean age of the remaining 175 patients was 38.4 years. Mean age at onset was 29.9 years. About 85% of the patients were male. The diagnosis was definite cluster headache for 87.4% of the sample and probable cluster headache for 12.6%. In addition, 88% of the population had episodic cluster headache.

Suicidal ideation increased during the ictal phase

During the ictal phase, 64.2% of participants reported passive suicidal ideation, and 35.8% reported active suicidal ideation. Furthermore, 5.8% of patients had a suicidal plan, and 2.3% attempted suicide. In the interictal phase, 4.0% of patients reported passive suicidal ideation, and 3.5% reported active suicidal ideation. Interictal suicidal planning was reported by 2.9% of participants, and 1.2% of participants attempted suicide interictally. The results were similar between patients with definite and probable cluster headache.

The ictal phase increased the odds of passive suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR], 42.46), active suicidal ideation (OR, 15.55), suicidal planning (OR, 2.06), and suicidal attempt (OR, 2.02), compared with the interictal phase. The differences in suicidal planning and suicidal attempt between the ictal and interictal phases, however, were not statistically significant.

Longer disease duration, higher attack intensity, higher Headache Impact Test–6 (HIT-6) score, GAD-7 score, and PHQ-9 score were associated with high ictal suicidality. Disease duration, HIT-6, and PHQ-9 remained significantly associated with high ictal suicidality in the multivariate analysis. Younger age at onset, longer disease duration, total number of lifetime bouts, and higher GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores were significantly associated with interictal suicidality in the univariable analysis. The total number of lifetime bouts and the PHQ-9 scores remained significant in the multivariable analysis.

In all, 54 patients were followed up between bouts. None reported passive suicidal ideation, 1.9% reported active suicidal ideation, 1.9% reported suicidal planning, and none reported suicidal attempt. Compared with the between-bouts period, the ictal phase was associated with significantly higher odds of active suicidal ideation (OR, 37.32) and nonsignificantly increased suicidal planning (OR, 3.20).

Patients need a disease-modifying treatment

Taken together, the study results underscore the importance of proper management of cluster headache to reduce its burden, said the authors. “Given that greater headache-related impact was independently associated with ictal suicidality, an intensive treatment to reduce the headache-related impact might be beneficial to prevent suicide in cluster headache patients,” they said. In addition to reducing headache-related impact and headache intensity, “a disease-modifying treatment to prevent further bouts is warranted to decrease suicidality in cluster headache patients.”

Although patients with cluster headache had increased suicidality in the ictal and interictal phases, they had lower suicidality between bouts, compared with the general population. This result suggests that patients remain mentally healthy when the bouts are over, and that “a strategy to shorten the length of bout is warranted,” said Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues. Furthermore, the fact that suicidality did not differ significantly between patients with definite cluster headache and those with probable cluster headache “prompts clinicians for an increased identification and intensive treatment strategy for probable cluster headache.”

The current study is the first prospective investigation of suicidality in the various phases of cluster headache, according to the investigators. It nevertheless has several limitations. The prevalence of chronic cluster headache was low in the study population, and not all patients presented for follow-up during the period between bouts. In addition, the data were obtained from recall, and consequently may be less accurate than those gained from prospective recording. Finally, Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues did not gather information on personality disorders, insomnia, substance abuse, or addiction, even though these factors can influence suicidality in patients with chronic pain.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest related to their research. The study was supported by a grant from the Korean Neurological Association.

SOURCE: Ji Lee M et al. Cephalalgia. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1177/0333102419845660.

Short- and long-term cluster headache disease burden, as well as depressive symptoms, contributes to suicidality, according to research published online Cephalalgia. Development of treatments that reduce the headache-related burden and prevent future bouts could reduce suicidality, said the researchers.

Although cluster headache has been called the “suicide headache,” few studies have examined suicidality in patients with cluster headache. Research by Rozen et al. found that the rate of suicidal attempt among patients was similar to that among the general population. The results have not been replicated, however, and the investigators did not examine whether suicidality varied according to the phases of the disorder.

A prospective, multicenter study

Mi Ji Lee, MD, PhD, clinical assistant professor of neurology at Samsung Medical Center in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues conducted a prospective study to investigate the suicidality associated with cluster headache and the factors associated with increased suicidality in that disorder. The researchers enrolled 193 consecutive patients with cluster headache between September 2016 and August 2018 at 15 hospitals. They examined the patients and used the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and the General Anxiety Disorder–7 item scale (GAD-7) screening tools. During the ictal and interictal phases, the researchers asked the patients whether they had had passive suicidal ideation, active suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, or suicidal attempt. Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues performed univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses to evaluate the factors associated with high ictal suicidality, which was defined as two or more positive responses during the ictal phase. Participants were followed up during the between-bout phase.

The researchers excluded 18 patients from analysis because they were between bouts at enrollment. The mean age of the remaining 175 patients was 38.4 years. Mean age at onset was 29.9 years. About 85% of the patients were male. The diagnosis was definite cluster headache for 87.4% of the sample and probable cluster headache for 12.6%. In addition, 88% of the population had episodic cluster headache.

Suicidal ideation increased during the ictal phase

During the ictal phase, 64.2% of participants reported passive suicidal ideation, and 35.8% reported active suicidal ideation. Furthermore, 5.8% of patients had a suicidal plan, and 2.3% attempted suicide. In the interictal phase, 4.0% of patients reported passive suicidal ideation, and 3.5% reported active suicidal ideation. Interictal suicidal planning was reported by 2.9% of participants, and 1.2% of participants attempted suicide interictally. The results were similar between patients with definite and probable cluster headache.

The ictal phase increased the odds of passive suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR], 42.46), active suicidal ideation (OR, 15.55), suicidal planning (OR, 2.06), and suicidal attempt (OR, 2.02), compared with the interictal phase. The differences in suicidal planning and suicidal attempt between the ictal and interictal phases, however, were not statistically significant.

Longer disease duration, higher attack intensity, higher Headache Impact Test–6 (HIT-6) score, GAD-7 score, and PHQ-9 score were associated with high ictal suicidality. Disease duration, HIT-6, and PHQ-9 remained significantly associated with high ictal suicidality in the multivariate analysis. Younger age at onset, longer disease duration, total number of lifetime bouts, and higher GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores were significantly associated with interictal suicidality in the univariable analysis. The total number of lifetime bouts and the PHQ-9 scores remained significant in the multivariable analysis.

In all, 54 patients were followed up between bouts. None reported passive suicidal ideation, 1.9% reported active suicidal ideation, 1.9% reported suicidal planning, and none reported suicidal attempt. Compared with the between-bouts period, the ictal phase was associated with significantly higher odds of active suicidal ideation (OR, 37.32) and nonsignificantly increased suicidal planning (OR, 3.20).

Patients need a disease-modifying treatment

Taken together, the study results underscore the importance of proper management of cluster headache to reduce its burden, said the authors. “Given that greater headache-related impact was independently associated with ictal suicidality, an intensive treatment to reduce the headache-related impact might be beneficial to prevent suicide in cluster headache patients,” they said. In addition to reducing headache-related impact and headache intensity, “a disease-modifying treatment to prevent further bouts is warranted to decrease suicidality in cluster headache patients.”

Although patients with cluster headache had increased suicidality in the ictal and interictal phases, they had lower suicidality between bouts, compared with the general population. This result suggests that patients remain mentally healthy when the bouts are over, and that “a strategy to shorten the length of bout is warranted,” said Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues. Furthermore, the fact that suicidality did not differ significantly between patients with definite cluster headache and those with probable cluster headache “prompts clinicians for an increased identification and intensive treatment strategy for probable cluster headache.”

The current study is the first prospective investigation of suicidality in the various phases of cluster headache, according to the investigators. It nevertheless has several limitations. The prevalence of chronic cluster headache was low in the study population, and not all patients presented for follow-up during the period between bouts. In addition, the data were obtained from recall, and consequently may be less accurate than those gained from prospective recording. Finally, Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues did not gather information on personality disorders, insomnia, substance abuse, or addiction, even though these factors can influence suicidality in patients with chronic pain.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest related to their research. The study was supported by a grant from the Korean Neurological Association.

SOURCE: Ji Lee M et al. Cephalalgia. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1177/0333102419845660.

Short- and long-term cluster headache disease burden, as well as depressive symptoms, contributes to suicidality, according to research published online Cephalalgia. Development of treatments that reduce the headache-related burden and prevent future bouts could reduce suicidality, said the researchers.

Although cluster headache has been called the “suicide headache,” few studies have examined suicidality in patients with cluster headache. Research by Rozen et al. found that the rate of suicidal attempt among patients was similar to that among the general population. The results have not been replicated, however, and the investigators did not examine whether suicidality varied according to the phases of the disorder.

A prospective, multicenter study

Mi Ji Lee, MD, PhD, clinical assistant professor of neurology at Samsung Medical Center in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues conducted a prospective study to investigate the suicidality associated with cluster headache and the factors associated with increased suicidality in that disorder. The researchers enrolled 193 consecutive patients with cluster headache between September 2016 and August 2018 at 15 hospitals. They examined the patients and used the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and the General Anxiety Disorder–7 item scale (GAD-7) screening tools. During the ictal and interictal phases, the researchers asked the patients whether they had had passive suicidal ideation, active suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, or suicidal attempt. Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues performed univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses to evaluate the factors associated with high ictal suicidality, which was defined as two or more positive responses during the ictal phase. Participants were followed up during the between-bout phase.

The researchers excluded 18 patients from analysis because they were between bouts at enrollment. The mean age of the remaining 175 patients was 38.4 years. Mean age at onset was 29.9 years. About 85% of the patients were male. The diagnosis was definite cluster headache for 87.4% of the sample and probable cluster headache for 12.6%. In addition, 88% of the population had episodic cluster headache.

Suicidal ideation increased during the ictal phase

During the ictal phase, 64.2% of participants reported passive suicidal ideation, and 35.8% reported active suicidal ideation. Furthermore, 5.8% of patients had a suicidal plan, and 2.3% attempted suicide. In the interictal phase, 4.0% of patients reported passive suicidal ideation, and 3.5% reported active suicidal ideation. Interictal suicidal planning was reported by 2.9% of participants, and 1.2% of participants attempted suicide interictally. The results were similar between patients with definite and probable cluster headache.

The ictal phase increased the odds of passive suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR], 42.46), active suicidal ideation (OR, 15.55), suicidal planning (OR, 2.06), and suicidal attempt (OR, 2.02), compared with the interictal phase. The differences in suicidal planning and suicidal attempt between the ictal and interictal phases, however, were not statistically significant.

Longer disease duration, higher attack intensity, higher Headache Impact Test–6 (HIT-6) score, GAD-7 score, and PHQ-9 score were associated with high ictal suicidality. Disease duration, HIT-6, and PHQ-9 remained significantly associated with high ictal suicidality in the multivariate analysis. Younger age at onset, longer disease duration, total number of lifetime bouts, and higher GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores were significantly associated with interictal suicidality in the univariable analysis. The total number of lifetime bouts and the PHQ-9 scores remained significant in the multivariable analysis.

In all, 54 patients were followed up between bouts. None reported passive suicidal ideation, 1.9% reported active suicidal ideation, 1.9% reported suicidal planning, and none reported suicidal attempt. Compared with the between-bouts period, the ictal phase was associated with significantly higher odds of active suicidal ideation (OR, 37.32) and nonsignificantly increased suicidal planning (OR, 3.20).

Patients need a disease-modifying treatment

Taken together, the study results underscore the importance of proper management of cluster headache to reduce its burden, said the authors. “Given that greater headache-related impact was independently associated with ictal suicidality, an intensive treatment to reduce the headache-related impact might be beneficial to prevent suicide in cluster headache patients,” they said. In addition to reducing headache-related impact and headache intensity, “a disease-modifying treatment to prevent further bouts is warranted to decrease suicidality in cluster headache patients.”

Although patients with cluster headache had increased suicidality in the ictal and interictal phases, they had lower suicidality between bouts, compared with the general population. This result suggests that patients remain mentally healthy when the bouts are over, and that “a strategy to shorten the length of bout is warranted,” said Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues. Furthermore, the fact that suicidality did not differ significantly between patients with definite cluster headache and those with probable cluster headache “prompts clinicians for an increased identification and intensive treatment strategy for probable cluster headache.”

The current study is the first prospective investigation of suicidality in the various phases of cluster headache, according to the investigators. It nevertheless has several limitations. The prevalence of chronic cluster headache was low in the study population, and not all patients presented for follow-up during the period between bouts. In addition, the data were obtained from recall, and consequently may be less accurate than those gained from prospective recording. Finally, Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues did not gather information on personality disorders, insomnia, substance abuse, or addiction, even though these factors can influence suicidality in patients with chronic pain.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest related to their research. The study was supported by a grant from the Korean Neurological Association.

SOURCE: Ji Lee M et al. Cephalalgia. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1177/0333102419845660.

FROM CEPHALAGIA

Key clinical point: Cluster headache is associated with increased suicidality during attacks and within the active period.

Major finding: Cluster headache attacks increased the risk of active suicidal ideation (odds ratio, 15.55).

Study details: A prospective, multicenter study of 175 patients with cluster headache.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a grant from the Korean Neurological Association.

Source: Ji Lee M et al. Cephalalgia. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1177/0333102419845660.

ASCO: Deintensified treatment in p16+ oropharyngeal cancer needs evaluation

Treatment deintensification for patients with p16+ oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) should occur only in the context of a clinical trial, according to a provisional clinical opinion released by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

“The hypothesis that deescalation of treatment intensity for patients with p16+ OPC can reduce long-term toxicity without compromising survival is compelling and necessitates careful study and the analysis of well-designed clinical trials before changing current treatment standards, wrote David J. Adelstein, MD, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, along with his associates on the expert panel. Their report is in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The panel undertook a review of the literature for evidence pertaining to the treatment of patients with HPV-mediated p16+ OPC with radiation, transoral surgery, concomitant chemoradiotherapy, and chemotherapy, in addition to immunotherapy and targeted therapy. Both randomized and nonrandomized studies were included in the review, and expert consensus opinion was taken into consideration.

After the review, the panelists concluded that the presumption that deintensified treatment in patients with p16+ OPC can lower long-term adverse effects without impacting survival is still a hypothesis that warrants further testing. While early findings of deintensified treatment techniques show promise, current treatment recommendations have not changed, they said.

“The standard of care for the definitive nonoperative management of cisplatin-eligible patients with advanced disease is concurrent chemoradiation with high-dose cisplatin given every 3 weeks,” the panel wrote. “For patients undergoing initial surgical resection, adjuvant chemoradiation with concurrent high-dose cisplatin given every 3 weeks is recommended for patients with positive margins and/or extranodal tumor extension,” they added.

At present, they recommend that deintensified treatment for patients with p16+ OPC should occur only in the context of a clinical trial.

The panel acknowledged that establishing definitive recommendations for all possible clinical scenarios is challenging because of restrictive exclusion criteria in key clinical trials. As a result, the accuracy of outcome data may be limited to specific patient populations.

More information on the provisional clinical opinion is available on the ASCO website.

ASCO funded the study. The authors reported financial affiliations with AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Genentech, PDS Biotechnology, and several others.

SOURCE: Adelstein DJ et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Apr 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00441.

Treatment deintensification for patients with p16+ oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) should occur only in the context of a clinical trial, according to a provisional clinical opinion released by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

“The hypothesis that deescalation of treatment intensity for patients with p16+ OPC can reduce long-term toxicity without compromising survival is compelling and necessitates careful study and the analysis of well-designed clinical trials before changing current treatment standards, wrote David J. Adelstein, MD, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, along with his associates on the expert panel. Their report is in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The panel undertook a review of the literature for evidence pertaining to the treatment of patients with HPV-mediated p16+ OPC with radiation, transoral surgery, concomitant chemoradiotherapy, and chemotherapy, in addition to immunotherapy and targeted therapy. Both randomized and nonrandomized studies were included in the review, and expert consensus opinion was taken into consideration.

After the review, the panelists concluded that the presumption that deintensified treatment in patients with p16+ OPC can lower long-term adverse effects without impacting survival is still a hypothesis that warrants further testing. While early findings of deintensified treatment techniques show promise, current treatment recommendations have not changed, they said.

“The standard of care for the definitive nonoperative management of cisplatin-eligible patients with advanced disease is concurrent chemoradiation with high-dose cisplatin given every 3 weeks,” the panel wrote. “For patients undergoing initial surgical resection, adjuvant chemoradiation with concurrent high-dose cisplatin given every 3 weeks is recommended for patients with positive margins and/or extranodal tumor extension,” they added.

At present, they recommend that deintensified treatment for patients with p16+ OPC should occur only in the context of a clinical trial.

The panel acknowledged that establishing definitive recommendations for all possible clinical scenarios is challenging because of restrictive exclusion criteria in key clinical trials. As a result, the accuracy of outcome data may be limited to specific patient populations.

More information on the provisional clinical opinion is available on the ASCO website.

ASCO funded the study. The authors reported financial affiliations with AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Genentech, PDS Biotechnology, and several others.

SOURCE: Adelstein DJ et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Apr 25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00441.

Treatment deintensification for patients with p16+ oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) should occur only in the context of a clinical trial, according to a provisional clinical opinion released by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

“The hypothesis that deescalation of treatment intensity for patients with p16+ OPC can reduce long-term toxicity without compromising survival is compelling and necessitates careful study and the analysis of well-designed clinical trials before changing current treatment standards, wrote David J. Adelstein, MD, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, along with his associates on the expert panel. Their report is in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The panel undertook a review of the literature for evidence pertaining to the treatment of patients with HPV-mediated p16+ OPC with radiation, transoral surgery, concomitant chemoradiotherapy, and chemotherapy, in addition to immunotherapy and targeted therapy. Both randomized and nonrandomized studies were included in the review, and expert consensus opinion was taken into consideration.