User login

Genetic data boost HIV surveillance efforts

SEATTLE – Advances in genetic sequencing are boosting efforts to identify new clusters of HIV infections and guiding public health interventions to address them. The method relies on resistance testing at diagnosis and virologic failure and allows public health researchers to determine the genetic relatedness of viruses responsible for new infections. If the viruses are genetically, geographically, and temporally associated, it indicates a previously unknown transmission cluster.

“The presence of a cluster indicates gaps in our preventative services, which we must address to improve service delivery and stop transmission,” Alexandra M. Oster, MD, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Surveillance, and Epidemiology at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, said during a talk at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

She noted that HIV brings special challenges to outbreak detection. The median delay between infection and diagnosis is 3 years. Individuals are highly mobile, and signals of new outbreaks can be quickly drowned out in high-burden areas. But these challenges aren’t unique. Tuberculosis has a similarly lengthy latency period, yet more than 75% of new TB outbreaks are now identified through the use of genetic data. Sequencing also is used to track food-borne illness. The CDC’s PulseNet is a network of laboratories that examines DNA sequences from bacterial infections in search of previously unrecognized outbreaks.

In the HIV setting, molecular surveillance has great potential in identifying and intervening in evolving networks of HIV transmission, but also carries ethical and other challenges.

Nevertheless, “I hope to make the case that cluster detection and response [using molecular surveillance] can help bring the nation closer to ending the HIV epidemic,” said Dr. Oster.

Molecular surveillance obtains most of its data from drug resistance testing, both at entry to care and after virologic failure, which then gets passed to the U.S. National HIV Surveillance System. The data are then stripped of patient identifying information and submitted to the CDC.

With data from multiple individuals in hand, researchers create a phylogenetic tree, in which closely-related viruses appear as close neighbors on a branch. “By tracing back along the tree, you can see the inferred ancestor of [individual strains], and also the inferred ancestor of all strains on the tree,” said Dr. Oster. Together with geographical data, that information allows researchers to identify clusters of patients connected in a transmission network, and that information can be passed along to federal, state, and local agencies to prevent infections and improve care.

From 1997 through 2012, the CDC’s molecular surveillance program focused on drug resistance patterns, but in 2013 the agency decided to expand to include transmission clusters. It now uses a tool called HIV Trace, which helps public health workers with no background in bioinformatics to visualize the DNA sequences and potential clusters, though Dr. Oster cautioned against overinterpretation of the results. “The links shown can easily be misinterpreted as actual social connections,” she said.

As proof of the approach’s potential, an analysis of the clusters identified showed their potential for HIV spread. On average in the United States, four new HIV infections occur per 100 people living with HIV. In the first 13 clusters that CDC identified, the number of infections was 33 per 100 person-years. The first 60 clusters had an average of 44 transmissions per 100 person-years. “None of these clusters had been found by [standard] epidemiologic methods, demonstrating that rapid transmission can be hard to detect without molecular data,” said Dr. Oster.

In 2018, all health departments began collecting sequencing data, and almost 40% of newly diagnosed patients have had sequencing data reported, more than 340,000 patients in total. Researchers have identified 145 priority clusters.

But use of molecular data is not the only method available. The CDC monitors increases in diagnoses in specific areas and conducts time-space analyses. These more traditional methods are particularly useful in areas with small populations or low HIV burden.

With a cluster identified, public health officials can attempt to identify all of the members of the network and help them to access services, such as testing, preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), syringe service programs, and linkage to care.

In San Antonio, Tex., an analysis identified a cluster of 24 gay and bisexual men, and further analysis revealed an extended network of 87 sexual or needle-sharing partners. Researchers also identified missed opportunities for diagnosis of acute infection as well as low access to PrEP, so the health department sent out an alert clarifying diagnosis testing guidelines, highlighting the concern over acute infection, and containing PrEP educational material.

Analysis of another network in Michigan found that all identified individuals were virally suppressed, even though the network continued to grow. That suggested that there were unidentified individuals who were contributing to transmission, which prompted efforts by providers to encourage testing, linkage to care, and prevention.

All of these developments are good news for efforts to eradicate HIV, but they come with pitfalls. Local communities have expressed concerned that molecular data could be used to identify direction of transmission and for prosecution, since there are HIV laws that criminalize lack of disclosure and potential exposure to the virus, even when transmission doesn’t occur. “These laws are not aligned with current science and have not been found to help curb HIV,” said Dr. Oster.

She noted that current molecular methods are incapable of identifying direction of transmission. Still, the CDC is reemphasizing efforts to protect public health data from nonpublic health use. “CDC and health departments implement unprecedented policies and procedures to ensure confidentiality and security of the data,” Dr. Oster said.

She reported having no relevant disclosures.

SEATTLE – Advances in genetic sequencing are boosting efforts to identify new clusters of HIV infections and guiding public health interventions to address them. The method relies on resistance testing at diagnosis and virologic failure and allows public health researchers to determine the genetic relatedness of viruses responsible for new infections. If the viruses are genetically, geographically, and temporally associated, it indicates a previously unknown transmission cluster.

“The presence of a cluster indicates gaps in our preventative services, which we must address to improve service delivery and stop transmission,” Alexandra M. Oster, MD, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Surveillance, and Epidemiology at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, said during a talk at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

She noted that HIV brings special challenges to outbreak detection. The median delay between infection and diagnosis is 3 years. Individuals are highly mobile, and signals of new outbreaks can be quickly drowned out in high-burden areas. But these challenges aren’t unique. Tuberculosis has a similarly lengthy latency period, yet more than 75% of new TB outbreaks are now identified through the use of genetic data. Sequencing also is used to track food-borne illness. The CDC’s PulseNet is a network of laboratories that examines DNA sequences from bacterial infections in search of previously unrecognized outbreaks.

In the HIV setting, molecular surveillance has great potential in identifying and intervening in evolving networks of HIV transmission, but also carries ethical and other challenges.

Nevertheless, “I hope to make the case that cluster detection and response [using molecular surveillance] can help bring the nation closer to ending the HIV epidemic,” said Dr. Oster.

Molecular surveillance obtains most of its data from drug resistance testing, both at entry to care and after virologic failure, which then gets passed to the U.S. National HIV Surveillance System. The data are then stripped of patient identifying information and submitted to the CDC.

With data from multiple individuals in hand, researchers create a phylogenetic tree, in which closely-related viruses appear as close neighbors on a branch. “By tracing back along the tree, you can see the inferred ancestor of [individual strains], and also the inferred ancestor of all strains on the tree,” said Dr. Oster. Together with geographical data, that information allows researchers to identify clusters of patients connected in a transmission network, and that information can be passed along to federal, state, and local agencies to prevent infections and improve care.

From 1997 through 2012, the CDC’s molecular surveillance program focused on drug resistance patterns, but in 2013 the agency decided to expand to include transmission clusters. It now uses a tool called HIV Trace, which helps public health workers with no background in bioinformatics to visualize the DNA sequences and potential clusters, though Dr. Oster cautioned against overinterpretation of the results. “The links shown can easily be misinterpreted as actual social connections,” she said.

As proof of the approach’s potential, an analysis of the clusters identified showed their potential for HIV spread. On average in the United States, four new HIV infections occur per 100 people living with HIV. In the first 13 clusters that CDC identified, the number of infections was 33 per 100 person-years. The first 60 clusters had an average of 44 transmissions per 100 person-years. “None of these clusters had been found by [standard] epidemiologic methods, demonstrating that rapid transmission can be hard to detect without molecular data,” said Dr. Oster.

In 2018, all health departments began collecting sequencing data, and almost 40% of newly diagnosed patients have had sequencing data reported, more than 340,000 patients in total. Researchers have identified 145 priority clusters.

But use of molecular data is not the only method available. The CDC monitors increases in diagnoses in specific areas and conducts time-space analyses. These more traditional methods are particularly useful in areas with small populations or low HIV burden.

With a cluster identified, public health officials can attempt to identify all of the members of the network and help them to access services, such as testing, preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), syringe service programs, and linkage to care.

In San Antonio, Tex., an analysis identified a cluster of 24 gay and bisexual men, and further analysis revealed an extended network of 87 sexual or needle-sharing partners. Researchers also identified missed opportunities for diagnosis of acute infection as well as low access to PrEP, so the health department sent out an alert clarifying diagnosis testing guidelines, highlighting the concern over acute infection, and containing PrEP educational material.

Analysis of another network in Michigan found that all identified individuals were virally suppressed, even though the network continued to grow. That suggested that there were unidentified individuals who were contributing to transmission, which prompted efforts by providers to encourage testing, linkage to care, and prevention.

All of these developments are good news for efforts to eradicate HIV, but they come with pitfalls. Local communities have expressed concerned that molecular data could be used to identify direction of transmission and for prosecution, since there are HIV laws that criminalize lack of disclosure and potential exposure to the virus, even when transmission doesn’t occur. “These laws are not aligned with current science and have not been found to help curb HIV,” said Dr. Oster.

She noted that current molecular methods are incapable of identifying direction of transmission. Still, the CDC is reemphasizing efforts to protect public health data from nonpublic health use. “CDC and health departments implement unprecedented policies and procedures to ensure confidentiality and security of the data,” Dr. Oster said.

She reported having no relevant disclosures.

SEATTLE – Advances in genetic sequencing are boosting efforts to identify new clusters of HIV infections and guiding public health interventions to address them. The method relies on resistance testing at diagnosis and virologic failure and allows public health researchers to determine the genetic relatedness of viruses responsible for new infections. If the viruses are genetically, geographically, and temporally associated, it indicates a previously unknown transmission cluster.

“The presence of a cluster indicates gaps in our preventative services, which we must address to improve service delivery and stop transmission,” Alexandra M. Oster, MD, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Surveillance, and Epidemiology at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, said during a talk at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

She noted that HIV brings special challenges to outbreak detection. The median delay between infection and diagnosis is 3 years. Individuals are highly mobile, and signals of new outbreaks can be quickly drowned out in high-burden areas. But these challenges aren’t unique. Tuberculosis has a similarly lengthy latency period, yet more than 75% of new TB outbreaks are now identified through the use of genetic data. Sequencing also is used to track food-borne illness. The CDC’s PulseNet is a network of laboratories that examines DNA sequences from bacterial infections in search of previously unrecognized outbreaks.

In the HIV setting, molecular surveillance has great potential in identifying and intervening in evolving networks of HIV transmission, but also carries ethical and other challenges.

Nevertheless, “I hope to make the case that cluster detection and response [using molecular surveillance] can help bring the nation closer to ending the HIV epidemic,” said Dr. Oster.

Molecular surveillance obtains most of its data from drug resistance testing, both at entry to care and after virologic failure, which then gets passed to the U.S. National HIV Surveillance System. The data are then stripped of patient identifying information and submitted to the CDC.

With data from multiple individuals in hand, researchers create a phylogenetic tree, in which closely-related viruses appear as close neighbors on a branch. “By tracing back along the tree, you can see the inferred ancestor of [individual strains], and also the inferred ancestor of all strains on the tree,” said Dr. Oster. Together with geographical data, that information allows researchers to identify clusters of patients connected in a transmission network, and that information can be passed along to federal, state, and local agencies to prevent infections and improve care.

From 1997 through 2012, the CDC’s molecular surveillance program focused on drug resistance patterns, but in 2013 the agency decided to expand to include transmission clusters. It now uses a tool called HIV Trace, which helps public health workers with no background in bioinformatics to visualize the DNA sequences and potential clusters, though Dr. Oster cautioned against overinterpretation of the results. “The links shown can easily be misinterpreted as actual social connections,” she said.

As proof of the approach’s potential, an analysis of the clusters identified showed their potential for HIV spread. On average in the United States, four new HIV infections occur per 100 people living with HIV. In the first 13 clusters that CDC identified, the number of infections was 33 per 100 person-years. The first 60 clusters had an average of 44 transmissions per 100 person-years. “None of these clusters had been found by [standard] epidemiologic methods, demonstrating that rapid transmission can be hard to detect without molecular data,” said Dr. Oster.

In 2018, all health departments began collecting sequencing data, and almost 40% of newly diagnosed patients have had sequencing data reported, more than 340,000 patients in total. Researchers have identified 145 priority clusters.

But use of molecular data is not the only method available. The CDC monitors increases in diagnoses in specific areas and conducts time-space analyses. These more traditional methods are particularly useful in areas with small populations or low HIV burden.

With a cluster identified, public health officials can attempt to identify all of the members of the network and help them to access services, such as testing, preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), syringe service programs, and linkage to care.

In San Antonio, Tex., an analysis identified a cluster of 24 gay and bisexual men, and further analysis revealed an extended network of 87 sexual or needle-sharing partners. Researchers also identified missed opportunities for diagnosis of acute infection as well as low access to PrEP, so the health department sent out an alert clarifying diagnosis testing guidelines, highlighting the concern over acute infection, and containing PrEP educational material.

Analysis of another network in Michigan found that all identified individuals were virally suppressed, even though the network continued to grow. That suggested that there were unidentified individuals who were contributing to transmission, which prompted efforts by providers to encourage testing, linkage to care, and prevention.

All of these developments are good news for efforts to eradicate HIV, but they come with pitfalls. Local communities have expressed concerned that molecular data could be used to identify direction of transmission and for prosecution, since there are HIV laws that criminalize lack of disclosure and potential exposure to the virus, even when transmission doesn’t occur. “These laws are not aligned with current science and have not been found to help curb HIV,” said Dr. Oster.

She noted that current molecular methods are incapable of identifying direction of transmission. Still, the CDC is reemphasizing efforts to protect public health data from nonpublic health use. “CDC and health departments implement unprecedented policies and procedures to ensure confidentiality and security of the data,” Dr. Oster said.

She reported having no relevant disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CROI 2019

FDA concerned about e-cigs/seizures in youth

the agency announced April 3.

Between 2010 and early 2019, the FDA and poison control centers received 35 reports of seizures that mentioned the use of e-cigarettes. Most reports involved youth or young adults, and the reports have increased slightly since June 2018, the announcement says.

“We want to be clear that we don’t yet know if there’s a direct relationship between the use of e-cigarettes and a risk of seizure,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, and Principal Deputy Commissioner Amy Abernethy, MD, PhD, in a statement. “We believe these 35 cases warrant scientific investigation into whether there is in fact a connection.”

In addition, the FDA is trying to determine whether any e-cigarette product-specific factors may be associated with the risk of seizures.

Seizures have been reported after a few puffs or up to 1 day after e-cigarette use and among first-time and experienced users. A few patients had a prior history of seizures or also used other substances, such as marijuana or amphetamines.

“While 35 cases may not seem like much compared to the total number of people using e-cigarettes, we are nonetheless concerned by these reported cases. We also recognized that not all of the cases may be reported,” Dr. Gottlieb and Dr. Abernethy said.

Although seizures are known side effects of nicotine toxicity and have been reported in the context of intentional or accidental swallowing of e-cigarette liquid, the voluntary reports of seizures occurring with vaping could represent a new safety issue, the FDA said.

The agency encouraged people to report cases via an online safety reporting portal. It also provided redacted case reports that involve vaping and seizures.

the agency announced April 3.

Between 2010 and early 2019, the FDA and poison control centers received 35 reports of seizures that mentioned the use of e-cigarettes. Most reports involved youth or young adults, and the reports have increased slightly since June 2018, the announcement says.

“We want to be clear that we don’t yet know if there’s a direct relationship between the use of e-cigarettes and a risk of seizure,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, and Principal Deputy Commissioner Amy Abernethy, MD, PhD, in a statement. “We believe these 35 cases warrant scientific investigation into whether there is in fact a connection.”

In addition, the FDA is trying to determine whether any e-cigarette product-specific factors may be associated with the risk of seizures.

Seizures have been reported after a few puffs or up to 1 day after e-cigarette use and among first-time and experienced users. A few patients had a prior history of seizures or also used other substances, such as marijuana or amphetamines.

“While 35 cases may not seem like much compared to the total number of people using e-cigarettes, we are nonetheless concerned by these reported cases. We also recognized that not all of the cases may be reported,” Dr. Gottlieb and Dr. Abernethy said.

Although seizures are known side effects of nicotine toxicity and have been reported in the context of intentional or accidental swallowing of e-cigarette liquid, the voluntary reports of seizures occurring with vaping could represent a new safety issue, the FDA said.

The agency encouraged people to report cases via an online safety reporting portal. It also provided redacted case reports that involve vaping and seizures.

the agency announced April 3.

Between 2010 and early 2019, the FDA and poison control centers received 35 reports of seizures that mentioned the use of e-cigarettes. Most reports involved youth or young adults, and the reports have increased slightly since June 2018, the announcement says.

“We want to be clear that we don’t yet know if there’s a direct relationship between the use of e-cigarettes and a risk of seizure,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, and Principal Deputy Commissioner Amy Abernethy, MD, PhD, in a statement. “We believe these 35 cases warrant scientific investigation into whether there is in fact a connection.”

In addition, the FDA is trying to determine whether any e-cigarette product-specific factors may be associated with the risk of seizures.

Seizures have been reported after a few puffs or up to 1 day after e-cigarette use and among first-time and experienced users. A few patients had a prior history of seizures or also used other substances, such as marijuana or amphetamines.

“While 35 cases may not seem like much compared to the total number of people using e-cigarettes, we are nonetheless concerned by these reported cases. We also recognized that not all of the cases may be reported,” Dr. Gottlieb and Dr. Abernethy said.

Although seizures are known side effects of nicotine toxicity and have been reported in the context of intentional or accidental swallowing of e-cigarette liquid, the voluntary reports of seizures occurring with vaping could represent a new safety issue, the FDA said.

The agency encouraged people to report cases via an online safety reporting portal. It also provided redacted case reports that involve vaping and seizures.

Marcela Romero-Reyes, DDS, PhD, Comments on Peripheral and Central Headache Challenges

###

Dr. Rapoport: Do you commonly see patients who present with symptoms of both central and peripheral symptoms in practice?

Dr. Romero-Reyes: Yes, I see patients that present with temporomandibular disorders (TMD) and headache comorbidity, as well as patients with migraine, tension-type headache, and cervicogenic headache with myofascial pain.

Dr. Rapoport: Why do you think this condition is so challenging to treat?

Dr. Romero-Reyes: I think this is because of the lack of understanding and awareness that in addition to the multifactorial nature of headache disorders, other types of disorders that are not neurovascular in origin may influence trigeminovascular nociception, and these types of non-neurovascular disorders involve the skill and knowledge of other expertise.

Headaches receiving inputs from extracranial structures such as in TMD (temporomandibular joint [TMJ] and muscles of mastication) and/or cervical structures (cervical spine, cervical muscles) require multidisciplinary evaluation and management. In these cases, the management should involve a neurologist specialized in headache disorders, a dentist trained in TMD and orofacial pain disorders, and a physical therapist with special training in craniofacial and cervical Therapeutics. Multidisciplinary communication is key for successful management.

Another reason is that myofascial pain (MFP) is often overlooked in patients with headache disorders. In my experience, patients with episodic and chronic migraine, episodic and chronic tension-type headache, cervicogenic headache, and patients presenting TMD and headache comorbidity can present trigger points in the craniofacial and cervical muscles, an indication of MFP. It has been reported that these patients present a higher disability impact. The presence of MFP may be contributing to the activation of the trigeminovascular system and therefore facilitate, exacerbate, and perpetuate headache symptomatology and may accelerate the progression to a more chronic form of the disorder.

Dr. Rapoport: In your opinion, is this considered a controversial topic? Why or why not?

Dr. Romero-Reyes: Yes, I think it is necessary to clarify that tenderness in the back of the head or of neck muscles present in headache patients does not necessarily imply that it is due to a nerve compression. This could also be caused by local myalgia but more commonly, from latent or active myofascial trigger points present in the muscles of the area being palpated, or by referred pain beyond the area of the muscle being palpated. Suboccipital muscles (in the occiput area) are not the only muscle group that is associated with headache and neck pain symptomatology. For example, the trapezius muscle, which is an overlooked source of tension- type and cervicogenic headache, can present trigger points that can refer pain to the shoulder, neck, head, face and the eye. In addition, other craniofacial and cervical muscles such as the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and temporalis muscles have been shown to be associated with headache symptomatology in the migraineur, as well as the chronic tension-type headache patient. Other muscles that also refer to the craniofacial area and can elicit headache and neck pain symptomatology include the masseter, occipitofrontalis, splenius capitis, splenius cervicis, semispinalis capitis, semispinalis cervicis and multifidi (cervical). The presence of trigger points in these muscles do not support or warrant the need to be removed or managed with non-conservative approaches.

Myofascial trigger points can result from muscle injury and overload, parafunctional activity, and poor head and neck posture. MFP is characterized by a regional pain and presence of localized tender areas (trigger points) in muscle, fascia or tendons that reproduce pain when palpated, and produce a pattern of regional pain spreading along the muscle palpated, or beyond the location boundary of the muscle palpated. It has been shown by microdyalisis that inflammatory mediators and neuropeptides are present in the area of an active trigger point. In addition, an increase of electromyography activity has been shown in trigger points in patients with chronic tension-type headache when compared with controls.

The importance of an evaluation by a skilled clinician in the craniofacial and cervical area to verify the source of pain is critical. The patient may be reporting pain in one area, but the source of the pain is in another area, and this is typical symptomatology present when there are active trigger points. In addition, an assessment of any contributing factors arising from the cervical spine (eg, poor posture) and craniofacial area (eg, TMD) that may exacerbate headache symptomatology is vital to proper diagnosis.

In my experience, patients with migraine, tension-type headache, cervicogenic headache, and TMD and headache comorbidity present MFP perpetuating headache symptomatology. MFP is not managed by surgical interventions. This perpetuating factor can be managed effectively with conservative measures. The plan is tailored for each patient’s needs. In general, the plan of management may include trigger point injections in the muscle with anesthetics, dry needling, and a physical therapy plan that may include education regarding habits and posture, exercises and physical therapy modalities, which are crucial to relieve pain and increase function. In cases of TMD and headache comorbidity, an occlusal appliance (stabilization appliance) can be included if necessary. We should also consider behavioral therapies (especially EMG biofeedback training) and some oral anti-inflammatories or muscle relaxants in the beginning of management, together with the plan of management mentioned above.

With these approaches to manage the MFP component in headache patients, I have been able to see that in migraineurs with MFP, the frequency and severity of the attacks decrease significantly. The patient may still experience migraine attacks, but feel happy to have the possibility to reduce medication intake and be in more control of their pain. In patients with tension-type headache, I have seen this even more dramatically.

This is telling us that headache pathophysiology involves a “conversation” between the peripheral and central nervous system, which influence each other. Peripheral nociceptive input coming from extracranial structures can induce trigeminovascular activation and therefore exacerbate a headache disorder and vice versa. Chronic myofascial pain may be the result of central sensitization due to the protracted peripheral nociceptive input (eg, poor posture, neck strain, parafunctional activity), therefore perpetuating the headache disorder even more.

Dr. Rapoport: Do you have any other comments about the article Treatment Challenges When Headache Has Central and Peripheral Involvement that you would like to share with our readers?

Dr. Romero-Reyes: It is simplistic to say migraine is either a peripheral or a central disorder, or that symptoms are either peripheral or central. Beyond thinking about migraine pain, migraine is fundamentally a brain (central) disorder. Its associated symptoms (nausea, phonophobia, photophobia) tell us this. Migraine headache is complex, and most likely the result of central mechanisms that can be influenced by peripheral inputs from the craniofacial and cervical region.

Embarking on surgical interventions for the management of headache disorders warrants a caution since it is still an experimental research question and the need of such therapies should be evaluated against conservative management. We are in a very exciting and hopeful time for migraine management. New evidence-based options from biological agents, such as anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) therapies, to non-pharmacological approaches, such as neuromodulation, can be offered to the patients. If the patient is experiencing pain in the neck area or other craniofacial area, it is recommended to have a thorough evaluation by a physical therapist with special training in cervical and craniofacial therapeutics and/or a dentist trained in TMD and orofacial pain disorders to work in consultation with a neurologist to elaborate a personalized management plan. Do not overlook the contribution of myofascial pain (trigger points) as well as TMD in the symptomatology of headache disorders. Few patients need to undergo surgical measures of peripheral nerves and muscles for improvement. An exhaustive evaluation must be undertaken first.

Resources for patients:

AHS

https://americanheadachesociety.org/

https://americanheadachesociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Choosing-Wisely-Flyer.pdf

AAOP

https://aaop.clubexpress.com/content.aspx?sl=1152088466

PTBCTT

###

Dr. Rapoport: Do you commonly see patients who present with symptoms of both central and peripheral symptoms in practice?

Dr. Romero-Reyes: Yes, I see patients that present with temporomandibular disorders (TMD) and headache comorbidity, as well as patients with migraine, tension-type headache, and cervicogenic headache with myofascial pain.

Dr. Rapoport: Why do you think this condition is so challenging to treat?

Dr. Romero-Reyes: I think this is because of the lack of understanding and awareness that in addition to the multifactorial nature of headache disorders, other types of disorders that are not neurovascular in origin may influence trigeminovascular nociception, and these types of non-neurovascular disorders involve the skill and knowledge of other expertise.

Headaches receiving inputs from extracranial structures such as in TMD (temporomandibular joint [TMJ] and muscles of mastication) and/or cervical structures (cervical spine, cervical muscles) require multidisciplinary evaluation and management. In these cases, the management should involve a neurologist specialized in headache disorders, a dentist trained in TMD and orofacial pain disorders, and a physical therapist with special training in craniofacial and cervical Therapeutics. Multidisciplinary communication is key for successful management.

Another reason is that myofascial pain (MFP) is often overlooked in patients with headache disorders. In my experience, patients with episodic and chronic migraine, episodic and chronic tension-type headache, cervicogenic headache, and patients presenting TMD and headache comorbidity can present trigger points in the craniofacial and cervical muscles, an indication of MFP. It has been reported that these patients present a higher disability impact. The presence of MFP may be contributing to the activation of the trigeminovascular system and therefore facilitate, exacerbate, and perpetuate headache symptomatology and may accelerate the progression to a more chronic form of the disorder.

Dr. Rapoport: In your opinion, is this considered a controversial topic? Why or why not?

Dr. Romero-Reyes: Yes, I think it is necessary to clarify that tenderness in the back of the head or of neck muscles present in headache patients does not necessarily imply that it is due to a nerve compression. This could also be caused by local myalgia but more commonly, from latent or active myofascial trigger points present in the muscles of the area being palpated, or by referred pain beyond the area of the muscle being palpated. Suboccipital muscles (in the occiput area) are not the only muscle group that is associated with headache and neck pain symptomatology. For example, the trapezius muscle, which is an overlooked source of tension- type and cervicogenic headache, can present trigger points that can refer pain to the shoulder, neck, head, face and the eye. In addition, other craniofacial and cervical muscles such as the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and temporalis muscles have been shown to be associated with headache symptomatology in the migraineur, as well as the chronic tension-type headache patient. Other muscles that also refer to the craniofacial area and can elicit headache and neck pain symptomatology include the masseter, occipitofrontalis, splenius capitis, splenius cervicis, semispinalis capitis, semispinalis cervicis and multifidi (cervical). The presence of trigger points in these muscles do not support or warrant the need to be removed or managed with non-conservative approaches.

Myofascial trigger points can result from muscle injury and overload, parafunctional activity, and poor head and neck posture. MFP is characterized by a regional pain and presence of localized tender areas (trigger points) in muscle, fascia or tendons that reproduce pain when palpated, and produce a pattern of regional pain spreading along the muscle palpated, or beyond the location boundary of the muscle palpated. It has been shown by microdyalisis that inflammatory mediators and neuropeptides are present in the area of an active trigger point. In addition, an increase of electromyography activity has been shown in trigger points in patients with chronic tension-type headache when compared with controls.

The importance of an evaluation by a skilled clinician in the craniofacial and cervical area to verify the source of pain is critical. The patient may be reporting pain in one area, but the source of the pain is in another area, and this is typical symptomatology present when there are active trigger points. In addition, an assessment of any contributing factors arising from the cervical spine (eg, poor posture) and craniofacial area (eg, TMD) that may exacerbate headache symptomatology is vital to proper diagnosis.

In my experience, patients with migraine, tension-type headache, cervicogenic headache, and TMD and headache comorbidity present MFP perpetuating headache symptomatology. MFP is not managed by surgical interventions. This perpetuating factor can be managed effectively with conservative measures. The plan is tailored for each patient’s needs. In general, the plan of management may include trigger point injections in the muscle with anesthetics, dry needling, and a physical therapy plan that may include education regarding habits and posture, exercises and physical therapy modalities, which are crucial to relieve pain and increase function. In cases of TMD and headache comorbidity, an occlusal appliance (stabilization appliance) can be included if necessary. We should also consider behavioral therapies (especially EMG biofeedback training) and some oral anti-inflammatories or muscle relaxants in the beginning of management, together with the plan of management mentioned above.

With these approaches to manage the MFP component in headache patients, I have been able to see that in migraineurs with MFP, the frequency and severity of the attacks decrease significantly. The patient may still experience migraine attacks, but feel happy to have the possibility to reduce medication intake and be in more control of their pain. In patients with tension-type headache, I have seen this even more dramatically.

This is telling us that headache pathophysiology involves a “conversation” between the peripheral and central nervous system, which influence each other. Peripheral nociceptive input coming from extracranial structures can induce trigeminovascular activation and therefore exacerbate a headache disorder and vice versa. Chronic myofascial pain may be the result of central sensitization due to the protracted peripheral nociceptive input (eg, poor posture, neck strain, parafunctional activity), therefore perpetuating the headache disorder even more.

Dr. Rapoport: Do you have any other comments about the article Treatment Challenges When Headache Has Central and Peripheral Involvement that you would like to share with our readers?

Dr. Romero-Reyes: It is simplistic to say migraine is either a peripheral or a central disorder, or that symptoms are either peripheral or central. Beyond thinking about migraine pain, migraine is fundamentally a brain (central) disorder. Its associated symptoms (nausea, phonophobia, photophobia) tell us this. Migraine headache is complex, and most likely the result of central mechanisms that can be influenced by peripheral inputs from the craniofacial and cervical region.

Embarking on surgical interventions for the management of headache disorders warrants a caution since it is still an experimental research question and the need of such therapies should be evaluated against conservative management. We are in a very exciting and hopeful time for migraine management. New evidence-based options from biological agents, such as anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) therapies, to non-pharmacological approaches, such as neuromodulation, can be offered to the patients. If the patient is experiencing pain in the neck area or other craniofacial area, it is recommended to have a thorough evaluation by a physical therapist with special training in cervical and craniofacial therapeutics and/or a dentist trained in TMD and orofacial pain disorders to work in consultation with a neurologist to elaborate a personalized management plan. Do not overlook the contribution of myofascial pain (trigger points) as well as TMD in the symptomatology of headache disorders. Few patients need to undergo surgical measures of peripheral nerves and muscles for improvement. An exhaustive evaluation must be undertaken first.

Resources for patients:

AHS

https://americanheadachesociety.org/

https://americanheadachesociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Choosing-Wisely-Flyer.pdf

AAOP

https://aaop.clubexpress.com/content.aspx?sl=1152088466

PTBCTT

###

Dr. Rapoport: Do you commonly see patients who present with symptoms of both central and peripheral symptoms in practice?

Dr. Romero-Reyes: Yes, I see patients that present with temporomandibular disorders (TMD) and headache comorbidity, as well as patients with migraine, tension-type headache, and cervicogenic headache with myofascial pain.

Dr. Rapoport: Why do you think this condition is so challenging to treat?

Dr. Romero-Reyes: I think this is because of the lack of understanding and awareness that in addition to the multifactorial nature of headache disorders, other types of disorders that are not neurovascular in origin may influence trigeminovascular nociception, and these types of non-neurovascular disorders involve the skill and knowledge of other expertise.

Headaches receiving inputs from extracranial structures such as in TMD (temporomandibular joint [TMJ] and muscles of mastication) and/or cervical structures (cervical spine, cervical muscles) require multidisciplinary evaluation and management. In these cases, the management should involve a neurologist specialized in headache disorders, a dentist trained in TMD and orofacial pain disorders, and a physical therapist with special training in craniofacial and cervical Therapeutics. Multidisciplinary communication is key for successful management.

Another reason is that myofascial pain (MFP) is often overlooked in patients with headache disorders. In my experience, patients with episodic and chronic migraine, episodic and chronic tension-type headache, cervicogenic headache, and patients presenting TMD and headache comorbidity can present trigger points in the craniofacial and cervical muscles, an indication of MFP. It has been reported that these patients present a higher disability impact. The presence of MFP may be contributing to the activation of the trigeminovascular system and therefore facilitate, exacerbate, and perpetuate headache symptomatology and may accelerate the progression to a more chronic form of the disorder.

Dr. Rapoport: In your opinion, is this considered a controversial topic? Why or why not?

Dr. Romero-Reyes: Yes, I think it is necessary to clarify that tenderness in the back of the head or of neck muscles present in headache patients does not necessarily imply that it is due to a nerve compression. This could also be caused by local myalgia but more commonly, from latent or active myofascial trigger points present in the muscles of the area being palpated, or by referred pain beyond the area of the muscle being palpated. Suboccipital muscles (in the occiput area) are not the only muscle group that is associated with headache and neck pain symptomatology. For example, the trapezius muscle, which is an overlooked source of tension- type and cervicogenic headache, can present trigger points that can refer pain to the shoulder, neck, head, face and the eye. In addition, other craniofacial and cervical muscles such as the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and temporalis muscles have been shown to be associated with headache symptomatology in the migraineur, as well as the chronic tension-type headache patient. Other muscles that also refer to the craniofacial area and can elicit headache and neck pain symptomatology include the masseter, occipitofrontalis, splenius capitis, splenius cervicis, semispinalis capitis, semispinalis cervicis and multifidi (cervical). The presence of trigger points in these muscles do not support or warrant the need to be removed or managed with non-conservative approaches.

Myofascial trigger points can result from muscle injury and overload, parafunctional activity, and poor head and neck posture. MFP is characterized by a regional pain and presence of localized tender areas (trigger points) in muscle, fascia or tendons that reproduce pain when palpated, and produce a pattern of regional pain spreading along the muscle palpated, or beyond the location boundary of the muscle palpated. It has been shown by microdyalisis that inflammatory mediators and neuropeptides are present in the area of an active trigger point. In addition, an increase of electromyography activity has been shown in trigger points in patients with chronic tension-type headache when compared with controls.

The importance of an evaluation by a skilled clinician in the craniofacial and cervical area to verify the source of pain is critical. The patient may be reporting pain in one area, but the source of the pain is in another area, and this is typical symptomatology present when there are active trigger points. In addition, an assessment of any contributing factors arising from the cervical spine (eg, poor posture) and craniofacial area (eg, TMD) that may exacerbate headache symptomatology is vital to proper diagnosis.

In my experience, patients with migraine, tension-type headache, cervicogenic headache, and TMD and headache comorbidity present MFP perpetuating headache symptomatology. MFP is not managed by surgical interventions. This perpetuating factor can be managed effectively with conservative measures. The plan is tailored for each patient’s needs. In general, the plan of management may include trigger point injections in the muscle with anesthetics, dry needling, and a physical therapy plan that may include education regarding habits and posture, exercises and physical therapy modalities, which are crucial to relieve pain and increase function. In cases of TMD and headache comorbidity, an occlusal appliance (stabilization appliance) can be included if necessary. We should also consider behavioral therapies (especially EMG biofeedback training) and some oral anti-inflammatories or muscle relaxants in the beginning of management, together with the plan of management mentioned above.

With these approaches to manage the MFP component in headache patients, I have been able to see that in migraineurs with MFP, the frequency and severity of the attacks decrease significantly. The patient may still experience migraine attacks, but feel happy to have the possibility to reduce medication intake and be in more control of their pain. In patients with tension-type headache, I have seen this even more dramatically.

This is telling us that headache pathophysiology involves a “conversation” between the peripheral and central nervous system, which influence each other. Peripheral nociceptive input coming from extracranial structures can induce trigeminovascular activation and therefore exacerbate a headache disorder and vice versa. Chronic myofascial pain may be the result of central sensitization due to the protracted peripheral nociceptive input (eg, poor posture, neck strain, parafunctional activity), therefore perpetuating the headache disorder even more.

Dr. Rapoport: Do you have any other comments about the article Treatment Challenges When Headache Has Central and Peripheral Involvement that you would like to share with our readers?

Dr. Romero-Reyes: It is simplistic to say migraine is either a peripheral or a central disorder, or that symptoms are either peripheral or central. Beyond thinking about migraine pain, migraine is fundamentally a brain (central) disorder. Its associated symptoms (nausea, phonophobia, photophobia) tell us this. Migraine headache is complex, and most likely the result of central mechanisms that can be influenced by peripheral inputs from the craniofacial and cervical region.

Embarking on surgical interventions for the management of headache disorders warrants a caution since it is still an experimental research question and the need of such therapies should be evaluated against conservative management. We are in a very exciting and hopeful time for migraine management. New evidence-based options from biological agents, such as anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) therapies, to non-pharmacological approaches, such as neuromodulation, can be offered to the patients. If the patient is experiencing pain in the neck area or other craniofacial area, it is recommended to have a thorough evaluation by a physical therapist with special training in cervical and craniofacial therapeutics and/or a dentist trained in TMD and orofacial pain disorders to work in consultation with a neurologist to elaborate a personalized management plan. Do not overlook the contribution of myofascial pain (trigger points) as well as TMD in the symptomatology of headache disorders. Few patients need to undergo surgical measures of peripheral nerves and muscles for improvement. An exhaustive evaluation must be undertaken first.

Resources for patients:

AHS

https://americanheadachesociety.org/

https://americanheadachesociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Choosing-Wisely-Flyer.pdf

AAOP

https://aaop.clubexpress.com/content.aspx?sl=1152088466

PTBCTT

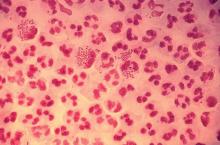

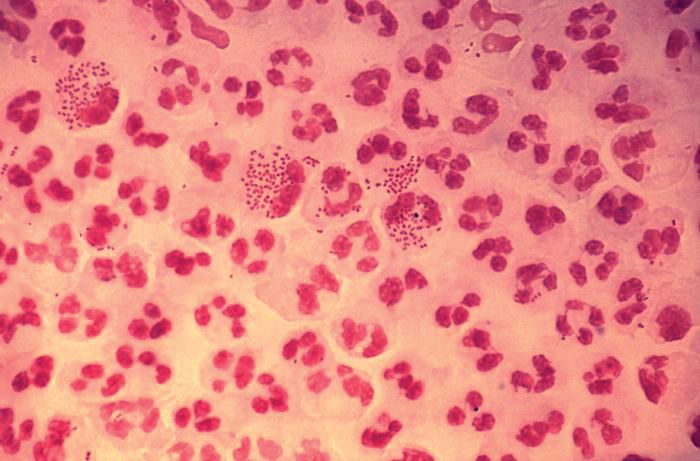

STIs pose complex challenge to HIV efforts

SEATTLE – Sexually-transmitted infections (STIs) such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis are on the rise among HIV-infected individuals, and emerging antimicrobial resistance in these organisms is presenting serious challenges to physicians. The issue may be traceable to the introduction of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in 2011, which previous studies have shown to be associated with less condom use.

In the United States, a 2017 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed rising incidences of chlamydia (+5% from 2015 to 2017), gonorrhea (+19%), and syphilis (+18%). “We have an incidence among men who have sex with men [MSM] that is above the pre-AIDS era estimates, and we have evidence of spread into heterosexual networks, and a very scary collision with the methamphetamine and heroine using networks,” said Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, professor of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

But the numbers alone don’t tell the whole story. “It’s not just the burden of these infections. What’s characterizing these trends is that we have continuing evolution of microbial resistance, which is really a crisis,” Dr. Marrazzo added during a plenary she delivered at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

These infections also remain intricately linked with HIV. An analysis of syphilis cases found that 88% occurred in men. Of those, 80% were MSM. Of the cases in MSM, 46% were coinfected with HIV. “Those are incredible rates,” said Dr. Marrazzo. Among women, the trends are even more alarming. There has been a greater than 150% increase in primary/secondary and congenital syphilis between 2013 and 2017.

Resistance to ceftriaxone and azithromycin remains on the rise in gonorrhea, with 24% of countries reporting at least a 5% incidence of strains that are less susceptible or resistant to ceftriaxone, and 81% of countries reporting similar trends with azithromycin.

In the absence of new drugs to overcome that resistance, or vaccines that can prevent gonorrhea and other infections, what are clinicians to do?

One option may be postexposure doxycycline. One trial in MSM showed that a 200-mg dose taken 24-72 hours after sex was associated with about a 70% increase in both time to first chlamydia and time to first syphilis infection, though no effect was seen on gonorrhea infections. “We shouldn’t be surprised. We know that gonorrhea is classically resistant to tetracyclines, and the MSM population has the highest prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in gonorrhea,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

There are pros and cons to this strategy, of course. On the one hand, doxycycline works for chlamydia and syphilis, it’s safe, and it’s easy to administer. “We’re up a tree when it comes to syphilis, so why not?” opined Dr. Marrazzo. In fact, some MSM have read the literature and are already using it prophylactically. But there are downsides, including adverse effects such as esophagitis/ulceration and photosensitivity, and it is contraindicated in pregnant women. And then there’s the potential for evolving greater resistance. “The horse is out of the barn with respect to gonorrhea, but I think it’s worth thinking about resistance to other pathogens, where we still rely on doxycycline [to treat] in rare cases,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

Finally, Dr. Marrazzo discussed the role of STI treatment in the effort to eradicate HIV. Should the Getting to 0 strategies include aggressive prevention and treatment of STIs? Despite the potentiating role of some STIs in the spread HIV, some urban areas are approaching zero new infections even as other STIs remain a problem. It could be that undetectable = untransmittable, regardless of the presence an STI. Some view targeting STIs as a regressive practice in a setting where the U=U mantra has opened up an era of sexual freedom living with or at risk of HIV.

On the other hand, there are also good arguments to target STIs while trying to eliminate HIV. Results from high-resource locales such as San Francisco and New York City are unlikely to be replicated in places like Sub-Saharan Africa. The public health burden of STIs is extensive, and antibiotic resistance and antibiotic shortages can make treatment difficult. The situation is also different for women, who may experience impacts on fertility or pregnancies, and do not have the same freedom as men in many countries. “Stigma is highly operative and I would wager that sexual pleasure and freedom remain a very elusive goal for women across the globe,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

Dr. Marrazzo has a research grant/grant pending from Cepheid, and is on the advisory panels of BioFire and Gilead.

SEATTLE – Sexually-transmitted infections (STIs) such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis are on the rise among HIV-infected individuals, and emerging antimicrobial resistance in these organisms is presenting serious challenges to physicians. The issue may be traceable to the introduction of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in 2011, which previous studies have shown to be associated with less condom use.

In the United States, a 2017 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed rising incidences of chlamydia (+5% from 2015 to 2017), gonorrhea (+19%), and syphilis (+18%). “We have an incidence among men who have sex with men [MSM] that is above the pre-AIDS era estimates, and we have evidence of spread into heterosexual networks, and a very scary collision with the methamphetamine and heroine using networks,” said Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, professor of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

But the numbers alone don’t tell the whole story. “It’s not just the burden of these infections. What’s characterizing these trends is that we have continuing evolution of microbial resistance, which is really a crisis,” Dr. Marrazzo added during a plenary she delivered at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

These infections also remain intricately linked with HIV. An analysis of syphilis cases found that 88% occurred in men. Of those, 80% were MSM. Of the cases in MSM, 46% were coinfected with HIV. “Those are incredible rates,” said Dr. Marrazzo. Among women, the trends are even more alarming. There has been a greater than 150% increase in primary/secondary and congenital syphilis between 2013 and 2017.

Resistance to ceftriaxone and azithromycin remains on the rise in gonorrhea, with 24% of countries reporting at least a 5% incidence of strains that are less susceptible or resistant to ceftriaxone, and 81% of countries reporting similar trends with azithromycin.

In the absence of new drugs to overcome that resistance, or vaccines that can prevent gonorrhea and other infections, what are clinicians to do?

One option may be postexposure doxycycline. One trial in MSM showed that a 200-mg dose taken 24-72 hours after sex was associated with about a 70% increase in both time to first chlamydia and time to first syphilis infection, though no effect was seen on gonorrhea infections. “We shouldn’t be surprised. We know that gonorrhea is classically resistant to tetracyclines, and the MSM population has the highest prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in gonorrhea,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

There are pros and cons to this strategy, of course. On the one hand, doxycycline works for chlamydia and syphilis, it’s safe, and it’s easy to administer. “We’re up a tree when it comes to syphilis, so why not?” opined Dr. Marrazzo. In fact, some MSM have read the literature and are already using it prophylactically. But there are downsides, including adverse effects such as esophagitis/ulceration and photosensitivity, and it is contraindicated in pregnant women. And then there’s the potential for evolving greater resistance. “The horse is out of the barn with respect to gonorrhea, but I think it’s worth thinking about resistance to other pathogens, where we still rely on doxycycline [to treat] in rare cases,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

Finally, Dr. Marrazzo discussed the role of STI treatment in the effort to eradicate HIV. Should the Getting to 0 strategies include aggressive prevention and treatment of STIs? Despite the potentiating role of some STIs in the spread HIV, some urban areas are approaching zero new infections even as other STIs remain a problem. It could be that undetectable = untransmittable, regardless of the presence an STI. Some view targeting STIs as a regressive practice in a setting where the U=U mantra has opened up an era of sexual freedom living with or at risk of HIV.

On the other hand, there are also good arguments to target STIs while trying to eliminate HIV. Results from high-resource locales such as San Francisco and New York City are unlikely to be replicated in places like Sub-Saharan Africa. The public health burden of STIs is extensive, and antibiotic resistance and antibiotic shortages can make treatment difficult. The situation is also different for women, who may experience impacts on fertility or pregnancies, and do not have the same freedom as men in many countries. “Stigma is highly operative and I would wager that sexual pleasure and freedom remain a very elusive goal for women across the globe,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

Dr. Marrazzo has a research grant/grant pending from Cepheid, and is on the advisory panels of BioFire and Gilead.

SEATTLE – Sexually-transmitted infections (STIs) such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis are on the rise among HIV-infected individuals, and emerging antimicrobial resistance in these organisms is presenting serious challenges to physicians. The issue may be traceable to the introduction of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in 2011, which previous studies have shown to be associated with less condom use.

In the United States, a 2017 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed rising incidences of chlamydia (+5% from 2015 to 2017), gonorrhea (+19%), and syphilis (+18%). “We have an incidence among men who have sex with men [MSM] that is above the pre-AIDS era estimates, and we have evidence of spread into heterosexual networks, and a very scary collision with the methamphetamine and heroine using networks,” said Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, professor of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

But the numbers alone don’t tell the whole story. “It’s not just the burden of these infections. What’s characterizing these trends is that we have continuing evolution of microbial resistance, which is really a crisis,” Dr. Marrazzo added during a plenary she delivered at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

These infections also remain intricately linked with HIV. An analysis of syphilis cases found that 88% occurred in men. Of those, 80% were MSM. Of the cases in MSM, 46% were coinfected with HIV. “Those are incredible rates,” said Dr. Marrazzo. Among women, the trends are even more alarming. There has been a greater than 150% increase in primary/secondary and congenital syphilis between 2013 and 2017.

Resistance to ceftriaxone and azithromycin remains on the rise in gonorrhea, with 24% of countries reporting at least a 5% incidence of strains that are less susceptible or resistant to ceftriaxone, and 81% of countries reporting similar trends with azithromycin.

In the absence of new drugs to overcome that resistance, or vaccines that can prevent gonorrhea and other infections, what are clinicians to do?

One option may be postexposure doxycycline. One trial in MSM showed that a 200-mg dose taken 24-72 hours after sex was associated with about a 70% increase in both time to first chlamydia and time to first syphilis infection, though no effect was seen on gonorrhea infections. “We shouldn’t be surprised. We know that gonorrhea is classically resistant to tetracyclines, and the MSM population has the highest prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in gonorrhea,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

There are pros and cons to this strategy, of course. On the one hand, doxycycline works for chlamydia and syphilis, it’s safe, and it’s easy to administer. “We’re up a tree when it comes to syphilis, so why not?” opined Dr. Marrazzo. In fact, some MSM have read the literature and are already using it prophylactically. But there are downsides, including adverse effects such as esophagitis/ulceration and photosensitivity, and it is contraindicated in pregnant women. And then there’s the potential for evolving greater resistance. “The horse is out of the barn with respect to gonorrhea, but I think it’s worth thinking about resistance to other pathogens, where we still rely on doxycycline [to treat] in rare cases,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

Finally, Dr. Marrazzo discussed the role of STI treatment in the effort to eradicate HIV. Should the Getting to 0 strategies include aggressive prevention and treatment of STIs? Despite the potentiating role of some STIs in the spread HIV, some urban areas are approaching zero new infections even as other STIs remain a problem. It could be that undetectable = untransmittable, regardless of the presence an STI. Some view targeting STIs as a regressive practice in a setting where the U=U mantra has opened up an era of sexual freedom living with or at risk of HIV.

On the other hand, there are also good arguments to target STIs while trying to eliminate HIV. Results from high-resource locales such as San Francisco and New York City are unlikely to be replicated in places like Sub-Saharan Africa. The public health burden of STIs is extensive, and antibiotic resistance and antibiotic shortages can make treatment difficult. The situation is also different for women, who may experience impacts on fertility or pregnancies, and do not have the same freedom as men in many countries. “Stigma is highly operative and I would wager that sexual pleasure and freedom remain a very elusive goal for women across the globe,” said Dr. Marrazzo.

Dr. Marrazzo has a research grant/grant pending from Cepheid, and is on the advisory panels of BioFire and Gilead.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CROI 2019

Anterior, apical, posterior: Vaginal anatomy for the gynecologic surgeon

CASE 1 Defining anatomic structures to assure surgical precision

A 44-year-old woman is scheduled for a vaginal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding. In your academic practice, a resident routinely operates with you and is accompanied by a medical student. As this is your first case with each learner, you review the steps of the procedure along with pertinent anatomy. During this discussion, numerous anatomic terms are used to describe anterior cul-de-sac entry, including pubocervical fascia, vesicouterine fold, and vesicovaginal space. Which of these terms, if any, are correct? Is there a preferred term that should be used to teach future learners so we can all “speak” the same language?

What’s in a name?

ObGyns must thoroughly understand pelvic anatomy, since much of our patient care relates to structures in that region. We also must understand the terminology that most appropriately describes each pelvic structure so that we can communicate effectively with colleagues and other providers. The case described above lists several terms that are commonly found in gynecologic textbooks and surgical atlases to describe dissection for vaginal hysterectomy. Lack of a standardized vocabulary, however, often confuses teachers and learners alike, and it highlights the importance of having a universal language to ensure the safe, effective performance of surgical procedures.1

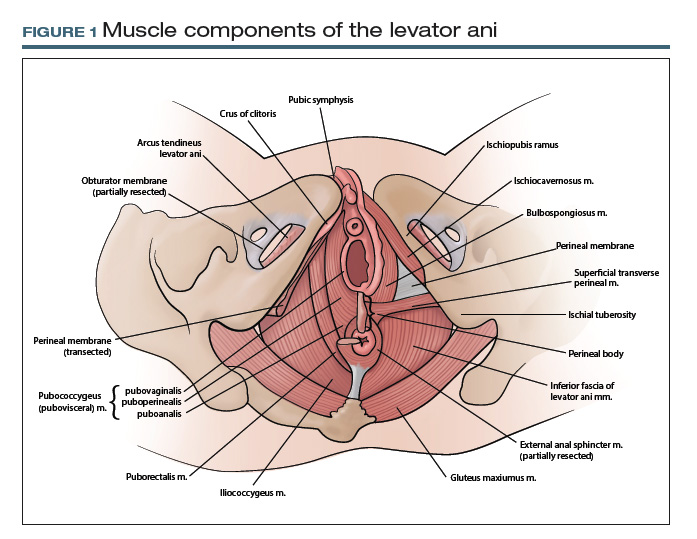

At first glance, it may seem that anatomic terms are inherently descriptive of the structure they represent; for example, the terms uterus and vagina seem rather obvious. However, many anatomic terms convey ambiguity. Which muscles, for example, constitute the levator ani: pubococcygeus, pubovisceral, pubovisceralis, puboperinealis, puboanalis, pubovaginalis, puborectalis, puborectal, iliococcygeus, ischiococcygeus? Do any of these terms redundantly describe the same structure, or does each term refer to an independent structure?

Standard terminology is essential

Anatomists long have recognized the need for standardized terminology to facilitate clear communication. To provide historical background, the term anatomy is derived from the Greek word for “dissection” or “to cut open.”2 Records on the scientific study of human anatomy date back thousands of years.

A brief review of current standardized terminology can be traced back to 1895, with the publication of Basle Terminologia Anatomica.3 That work was intended to provide a consolidated reference with clear direction regarding which anatomic terms should be used. It was updated several times during the ensuing century and was later published as Nomina Anatomica.

In 1990, an international committee was formed with representatives from many anatomical organizations, again with the intention of providing standardized anatomic terminology. Those efforts resulted in the publication of Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology, commonly referred to as TA, in 1998. TA continues to be the referent standard for human anatomic terminology; it was most recently updated in 2011.4

CASE 2 Conveying details of mesh erosion

A 52-year-old woman presents to the general gynecology clinic with a 10-year history of pelvic pain and dyspareunia after undergoing vaginal mesh surgery for prolapse and urinary incontinence. On examination, there is a visible ridge of mesh extending from the left side of the midurethra along the anterior and lateral vagina for a length of 1.5 cm. There also is a palpable tight band on the right vaginal wall near the ischial spine that reproduces her pain and causes spasm of the levator ani. You believe the patient needs a urogynecology referral for complications of vaginal mesh. How do you best describe your findings to your urogynecology colleague?

Continue to: Pelvic anatomy from the SGS perspective...

Pelvic anatomy from the SGS perspective

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) recognized the importance of standardizing terminology specific to the pelvis. The SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group thus was organized in 2016. The Pelvic Anatomy Group’s purpose is to help educate physicians about pelvic anatomy, with the overarching goal of compiling instructional materials, primarily from dissections (surgical or cadaveric), and radiologic imaging for all pelvic structures. Throughout the discussions on this initiative, it became clear that standardized terms needed to be established and used for pelvic structures.

While TA is an excellent reference work, it does not include all of the clinically relevant structures for gynecologic surgeons. As physicians, surgeons, and women’s health care providers, we read about and discuss pelvic anatomy structures in medical textbooks, medical literature, and clinical settings that are not necessarily included in TA. In addition, advances in information technology have facilitated the creation of clinically oriented computer-based anatomy programs and expanded the number and availability of electronic publications on surgical and clinical anatomy.5 As a result, there is a need not only to standardize nomenclature but also to continually revise and update terminology and integrate new terms, both from an anatomic and a clinical perspective.

The Pelvic Anatomy Group developed a novel approach to anatomic terminology. We decided to review the medical literature, identify the terms used, adjudicate the terms with current TA terms, and provide consensus for the terms and structures in the pelvis. Because of the volume of literature available and the existing number of terms, we divided the pelvis into 4 regions—anterior, apical, posterior, and vulvar—to improve the feasibility of reviewing the medical literature for the entire female pelvis.

Our process for tackling terminology

Our literature review started with the anterior compartment. (For complete details, see our prior publication.3) Modeled on a systematic review, we searched the MEDLINE database for terms related to the anterior pelvis, screened all associated abstracts, and then extracted terms from appropriate papers. We also identified several book chapters from various disciplines (anatomy, gynecology, urology, and radiology) to ensure wide representation of disciplines. We then extracted all terms pertinent to the anterior pelvis.

We organized the terms, with terms that referred to the same anatomic structure grouped together. Whenever possible, we used TA terms as the preferred terms. In this process, however, we identified several clinically relevant terms that were not included in TA: pelvic sidewall, pelvic bones, anterior compartment, pubourethral ligament, vaginal sulcus, and levator hiatus, among others. The new terms were then proposed and agreed on by members of the SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group and accepted by SGS members. We currently are completing a similar process for the apical pelvis, posterior pelvis, and vulvar regions.

TA code numbers pinpoint the nomenclature

As we move forward, we suggest that physicians use TA or other approved terms for patient and research communication. Such use will help standardize anatomic terms and also will improve communication between providers and education for learners.

Continue to: TA includes approved options...

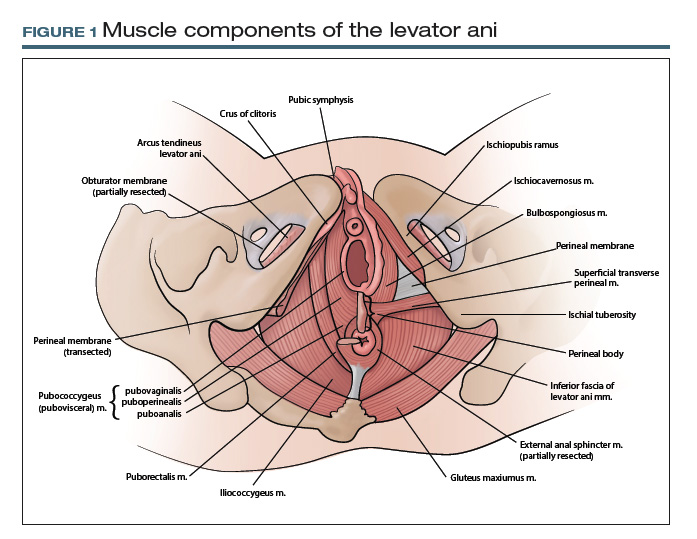

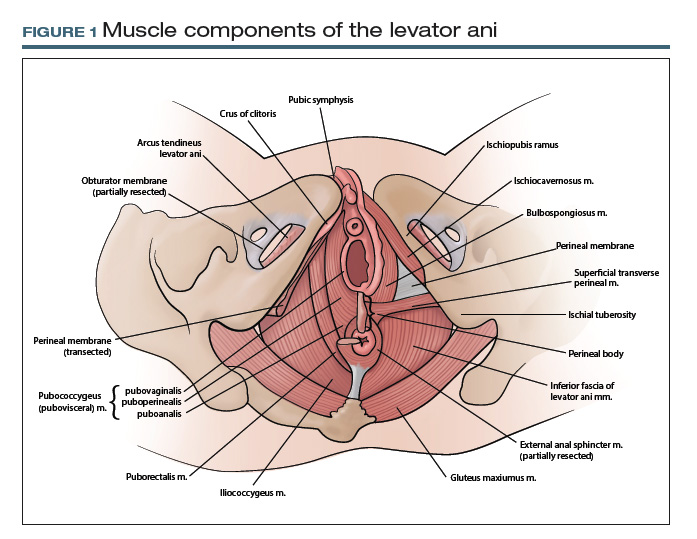

TA includes approved options in English and Latin and lists a unique identification number for each term (shown in parentheses in the examples that follow). For instance, to answer the question posed earlier, the levator ani (A04.5.04.002) is comprised of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), puborectalis (A04.5.04.007), and iliococcygeus (A04.5.04.008) muscles (FIGURE 1).The terms pubovisceral and pubovisceralis are used synonymously in the literature with pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003).3 The additional terms puboperinealis (A04.5.04.004), pubovaginalis (A04.5.04.005), and puboanalis (A04.5.04.006) are subcomponents of the pubococcygeus (A04.5.04.003), and this relationship is indicated in TA by indentation formatting.4 Finally, the ischiococcygeus (A04.5.04.011) muscle is not considered part of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).

Revisiting the mesh erosion case: Reporting your findings

After reviewing the recommended terminology for the anterior pelvis,3,4 you might draft a report as follows: “A mesh erosion was visualized in anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006) at the level of the mid-urethra extending into ‘anterior and lateral vaginal sulci’ (proposed term). In addition, there is a painful tight band in the ‘lateral vaginal wall’ (proposed term) near the ischial spine (A02.5.01.205). Palpation of this band reproduces the patient’s pain and causes secondary spasm of the levator ani (A04.5.04.002).” Certainly, TA identification numbers would not be expected to be included in medical communication; they are included here for reference.

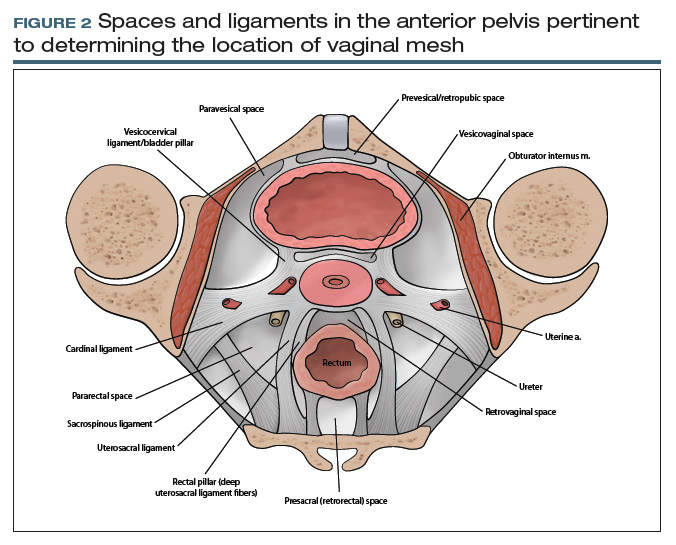

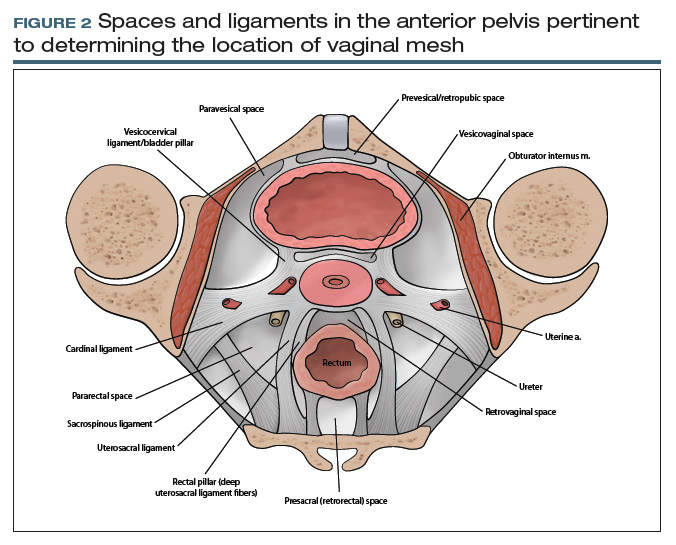

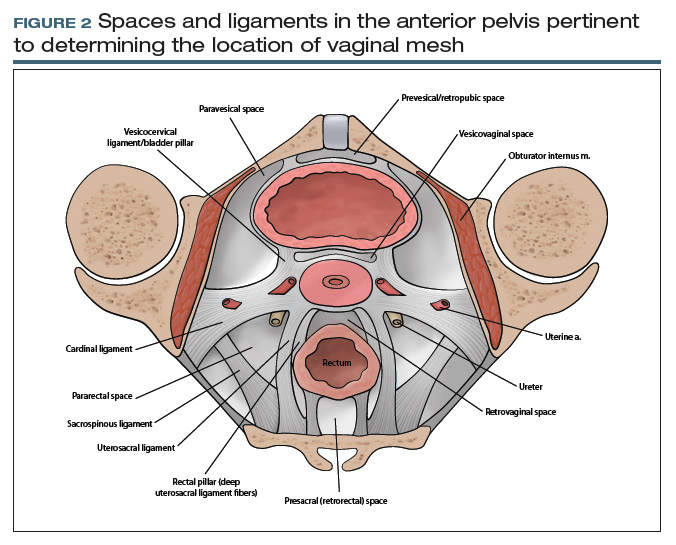

From your description, your urogynecology colleague has a better understanding of the location of your patient’s vaginal mesh and requests her operative report from an outside facility. In the operative report, the surgeon described “placement of mesh into the vagina, dissection through the rectal spaces, and anchoring of the mesh into the levator/pelvic muscles, the cervix, and lastly to the paraurethral ligaments,” and “passage of trocars through the cave of Retzius at the level of the midurethra” (FIGURE 2).

Based on this description, the urogynecologist ascertains that the mesh is located in the anterior vaginal wall (A09.1.04.006), with passage of anchoring arms through the bilateral sacrospinous ligaments (A03.6.03.007) and retropubic space (A10.1.01.003). Exposed mesh is visible, extending from the midurethra to the “anterior and lateral vaginal sulci” (proposed term).

This case clearly demonstrates the importance of communication between providers for patient care, since understanding the patient’s anatomy and the location of the vaginal mesh is important for planning surgical excision of the exposed mesh.

Additional initiatives

Outlining standardized terminology is just the first step toward improving the anatomic “language” used among providers. Ongoing efforts from the SGS Pelvic Anatomy Group include a special imaging group’s review of imaging modalities (ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, computerized tomography) to improve standardization on reporting clinical anatomy. In addition, SGS has developed a group to create educational content related to the structures identified by the terminology group from cadaveric or surgical dissections. Educational materials will be compiled to help physicians and learners expand their anatomic understanding and improve their communication.

Further details of the Pelvic Anatomy Group’s efforts can be found on the SGS website at https://www.sgsonline.org.

- American Association of Clinical Anatomists, Educational Affairs Committee. The clinical anatomy of several invasive procedures. Clin Anat. 1999;12:43-54.

- Venes D, ed. Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. 23rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Company; 2017.

- Jeppson PC, Balgobin S, Washington BB, et al; for the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Pelvic Anatomy Group. Recommended standardized terminology of the anterior female pelvis based on a structured medical literature review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:26-39.

- Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminologies (FCAT). Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme; 2011.

- Rosse C. Terminologia Anatomica: considered from the perspective of next-generation knowledge sources. Clin Anat. 2001;14:120-133.

CASE 1 Defining anatomic structures to assure surgical precision

A 44-year-old woman is scheduled for a vaginal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding. In your academic practice, a resident routinely operates with you and is accompanied by a medical student. As this is your first case with each learner, you review the steps of the procedure along with pertinent anatomy. During this discussion, numerous anatomic terms are used to describe anterior cul-de-sac entry, including pubocervical fascia, vesicouterine fold, and vesicovaginal space. Which of these terms, if any, are correct? Is there a preferred term that should be used to teach future learners so we can all “speak” the same language?

What’s in a name?

ObGyns must thoroughly understand pelvic anatomy, since much of our patient care relates to structures in that region. We also must understand the terminology that most appropriately describes each pelvic structure so that we can communicate effectively with colleagues and other providers. The case described above lists several terms that are commonly found in gynecologic textbooks and surgical atlases to describe dissection for vaginal hysterectomy. Lack of a standardized vocabulary, however, often confuses teachers and learners alike, and it highlights the importance of having a universal language to ensure the safe, effective performance of surgical procedures.1

At first glance, it may seem that anatomic terms are inherently descriptive of the structure they represent; for example, the terms uterus and vagina seem rather obvious. However, many anatomic terms convey ambiguity. Which muscles, for example, constitute the levator ani: pubococcygeus, pubovisceral, pubovisceralis, puboperinealis, puboanalis, pubovaginalis, puborectalis, puborectal, iliococcygeus, ischiococcygeus? Do any of these terms redundantly describe the same structure, or does each term refer to an independent structure?

Standard terminology is essential

Anatomists long have recognized the need for standardized terminology to facilitate clear communication. To provide historical background, the term anatomy is derived from the Greek word for “dissection” or “to cut open.”2 Records on the scientific study of human anatomy date back thousands of years.

A brief review of current standardized terminology can be traced back to 1895, with the publication of Basle Terminologia Anatomica.3 That work was intended to provide a consolidated reference with clear direction regarding which anatomic terms should be used. It was updated several times during the ensuing century and was later published as Nomina Anatomica.