User login

Five pitfalls in optimizing medical management of HFrEF

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Many of the abundant missed opportunities to optimize pharmacotherapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction revolve around not getting fully on board with the guideline-directed medical therapy shown to be highly effective at improving clinical outcomes, Akshay S. Desai, MD, asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

“If you take nothing else away from this talk, is really quite profound,” declared Dr. Desai, director of the cardiomyopathy and heart failure program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and a cardiologist at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

He highlighted five common traps or pitfalls for physicians with regard to medical therapy of patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF):

Underutilization of guideline-directed medical therapy

The current ACC/American Heart Association/Heart Failure Society of America guidelines on heart failure management (Circulation. 2017 Aug 8;136[6]:e137-61) reflect 20 years of impressive progress in improving heart failure outcomes through the use of increasingly effective guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT). The magnitude of this improvement was nicely captured in a meta-analysis of 57 randomized controlled trials published during 1987-2015. The meta-analysis showed that, although ACE inhibitor therapy alone had no significant impact on all-cause mortality compared to placebo in patients with HFrEF, the sequential addition of guideline-directed drugs conferred stepwise improvements in survival. This approach culminated in a 56% reduction in all-cause mortality with the combination of an ACE inhibitor, beta-blocker, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA), compared with placebo, and a 63% reduction with an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), beta-blocker, and MRA (Circ Heart Fail. 2017 Jan;10(1). pii: e003529).

Moreover, the benefits of contemporary GDMT extend beyond reductions in all-cause mortality, death due to heart failure, and heart failure–related hospitalizations into areas where one wouldn’t necessarily have expected to see much benefit. For example, an analysis of data on more than 40,000 HFrEF patients in 12 clinical trials showed a sharp decline in the rate of sudden death over the years as new agents were incorporated into GDMT. The cumulative incidence of sudden death within 90 days after randomization plunged from 2.4% in the earliest trial to 1.0% in the most recent one (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 6;377[1]:41-51).

“We’re at the point where we now question whether routine use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in primary prevention patients with nonischemic heart failure is really worthwhile on the backdrop of effective medical therapy,” Dr. Desai observed.

But there’s a problem: “We don’t do a great job with GDMT, even with this incredible evidence base that we have,” the cardiologist said.

He cited a report from the CHAMP-HF registry that scrutinized the use of GDMT in more than 3,500 ambulatory HFrEF patients in 150 U.S. primary care and cardiology practices. It found that 67% of patients deemed eligible for an MRA weren’t on one. Neither were 33% with no contraindications to beta-blocker therapy and 27% who were eligible for an ACE inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), or ARNI (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jul 24;72[4]:351-66).

“This highlights a huge opportunity for further guideline-directed optimization of therapy,” he said.

Underdosing of GDMT

The CHAMP-HF registry contained further disappointing news regarding the state of treatment of patients with HFrEF in ambulatory settings: Among those patients who were on GDMT, very few were receiving the recommended target doses of the medications as established in major clinical trials and specified in the guidelines. Only 14% of patients on an ARNI were on the target dose, as were 28% on a beta-blocker, and 17% of those on an ACE inhibitor or ARB. And among patients who were eligible for all classes of GDMT, just 1% were simultaneously on the target doses of an MRA, beta-blocker, and ARNI, ACE inhibitor, or ARB. This despite solid evidence that, although some benefit is derived from initiating these medications, incremental benefit comes from dose titration.

“Even for those of us who feel like we do this quite well, if we examine our practices systematically – and we’ve done this in our own practices at Brigham and Women’s – you see that a lot of eligible patients aren’t on optimal therapy. And you might argue that many of them have contraindications, but even when you do a deep dive into the literature or the electronic medical record and ask the question – Why is this patient with normal renal function and normal potassium with class II HFrEF not on an MRA? – sometimes it’s hard to establish why that’s the case,” said Dr. Desai.

Interrupting GDMT during hospitalizations

This is common practice. But in fact, continuation of GDMT is generally well tolerated in the setting of acute decompensated heart failure in the absence of severe hypotension and cardiogenic shock. Moreover, in-hospital discontinuation or dose reduction is associated with increased risks of readmission and mortality.

And in treatment-naive HFrEF patients, what better place to introduce a medication and assess its tolerability than the hospital? Plus, medications prescribed at discharge are more likely to be continued in the outpatient setting, he noted.

Being seduced by the illusion of stability

The guidelines state that patients with NYHA class II or III HFrEF who tolerate an ACE inhibitor or ARB should be transitioned to an ARNI to further reduce their risk of morbidity and mortality. Yet many physicians wait to make the switch until clinical decompensation occurs. That’s a mistake, as was demonstrated in the landmark PARADIGM-HF trial. Twenty percent of study participants without a prior hospitalization for heart failure experienced cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization during the follow-up period. Patients who were clinically stable as defined by no prior heart failure hospitalization or none within 3 months prior to enrollment were as likely to benefit from ARNI therapy with sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) as were those with a recent decompensation (JACC Heart Fail. 2016 Oct;4[10]:816-22). “A key message is that stability is an illusion in patients with symptomatic heart failure,”said Dr. Desai. “In PARADIGM-HF, the first event for about half of patients was not heralded by a worsening of symptoms or a heart failure hospitalization, it was an abrupt death at home. This may mean that a missed opportunity to optimize treatment may not come back to you down the road, so waiting until patients get worse in order to optimize their therapy may not be the best strategy.”

Inadequate laboratory monitoring

The MRAs, spironolactone and eplerenone (Inspra), are the GDMT drugs for which laboratory surveillance takes on the greatest importance because of their potential to induce hyperkalemia. The guidelines are clear that a potassium level and measurement of renal function should be obtained within a week of initiating therapy with an MRA, again at 4 weeks, and periodically thereafter.

“In general, this is done in clinical practice almost never,” Dr. Desai stressed.

These agents should be avoided in patients with prior hyperkalemia or advanced chronic kidney disease, and used with care in groups known to be at increased risk for hyperkalemia, including the elderly and patients with diabetes.

He considers spironolactone equivalent to eplerenone so long as the dosing is adequate. He generally reserves eplerenone for patients with poorly tolerated antiandrogenic effects on spironolactone.

Dr. Desai reported serving as a paid consultant to more than half a dozen pharmaceutical or medical device companies.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Many of the abundant missed opportunities to optimize pharmacotherapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction revolve around not getting fully on board with the guideline-directed medical therapy shown to be highly effective at improving clinical outcomes, Akshay S. Desai, MD, asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

“If you take nothing else away from this talk, is really quite profound,” declared Dr. Desai, director of the cardiomyopathy and heart failure program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and a cardiologist at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

He highlighted five common traps or pitfalls for physicians with regard to medical therapy of patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF):

Underutilization of guideline-directed medical therapy

The current ACC/American Heart Association/Heart Failure Society of America guidelines on heart failure management (Circulation. 2017 Aug 8;136[6]:e137-61) reflect 20 years of impressive progress in improving heart failure outcomes through the use of increasingly effective guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT). The magnitude of this improvement was nicely captured in a meta-analysis of 57 randomized controlled trials published during 1987-2015. The meta-analysis showed that, although ACE inhibitor therapy alone had no significant impact on all-cause mortality compared to placebo in patients with HFrEF, the sequential addition of guideline-directed drugs conferred stepwise improvements in survival. This approach culminated in a 56% reduction in all-cause mortality with the combination of an ACE inhibitor, beta-blocker, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA), compared with placebo, and a 63% reduction with an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), beta-blocker, and MRA (Circ Heart Fail. 2017 Jan;10(1). pii: e003529).

Moreover, the benefits of contemporary GDMT extend beyond reductions in all-cause mortality, death due to heart failure, and heart failure–related hospitalizations into areas where one wouldn’t necessarily have expected to see much benefit. For example, an analysis of data on more than 40,000 HFrEF patients in 12 clinical trials showed a sharp decline in the rate of sudden death over the years as new agents were incorporated into GDMT. The cumulative incidence of sudden death within 90 days after randomization plunged from 2.4% in the earliest trial to 1.0% in the most recent one (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 6;377[1]:41-51).

“We’re at the point where we now question whether routine use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in primary prevention patients with nonischemic heart failure is really worthwhile on the backdrop of effective medical therapy,” Dr. Desai observed.

But there’s a problem: “We don’t do a great job with GDMT, even with this incredible evidence base that we have,” the cardiologist said.

He cited a report from the CHAMP-HF registry that scrutinized the use of GDMT in more than 3,500 ambulatory HFrEF patients in 150 U.S. primary care and cardiology practices. It found that 67% of patients deemed eligible for an MRA weren’t on one. Neither were 33% with no contraindications to beta-blocker therapy and 27% who were eligible for an ACE inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), or ARNI (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jul 24;72[4]:351-66).

“This highlights a huge opportunity for further guideline-directed optimization of therapy,” he said.

Underdosing of GDMT

The CHAMP-HF registry contained further disappointing news regarding the state of treatment of patients with HFrEF in ambulatory settings: Among those patients who were on GDMT, very few were receiving the recommended target doses of the medications as established in major clinical trials and specified in the guidelines. Only 14% of patients on an ARNI were on the target dose, as were 28% on a beta-blocker, and 17% of those on an ACE inhibitor or ARB. And among patients who were eligible for all classes of GDMT, just 1% were simultaneously on the target doses of an MRA, beta-blocker, and ARNI, ACE inhibitor, or ARB. This despite solid evidence that, although some benefit is derived from initiating these medications, incremental benefit comes from dose titration.

“Even for those of us who feel like we do this quite well, if we examine our practices systematically – and we’ve done this in our own practices at Brigham and Women’s – you see that a lot of eligible patients aren’t on optimal therapy. And you might argue that many of them have contraindications, but even when you do a deep dive into the literature or the electronic medical record and ask the question – Why is this patient with normal renal function and normal potassium with class II HFrEF not on an MRA? – sometimes it’s hard to establish why that’s the case,” said Dr. Desai.

Interrupting GDMT during hospitalizations

This is common practice. But in fact, continuation of GDMT is generally well tolerated in the setting of acute decompensated heart failure in the absence of severe hypotension and cardiogenic shock. Moreover, in-hospital discontinuation or dose reduction is associated with increased risks of readmission and mortality.

And in treatment-naive HFrEF patients, what better place to introduce a medication and assess its tolerability than the hospital? Plus, medications prescribed at discharge are more likely to be continued in the outpatient setting, he noted.

Being seduced by the illusion of stability

The guidelines state that patients with NYHA class II or III HFrEF who tolerate an ACE inhibitor or ARB should be transitioned to an ARNI to further reduce their risk of morbidity and mortality. Yet many physicians wait to make the switch until clinical decompensation occurs. That’s a mistake, as was demonstrated in the landmark PARADIGM-HF trial. Twenty percent of study participants without a prior hospitalization for heart failure experienced cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization during the follow-up period. Patients who were clinically stable as defined by no prior heart failure hospitalization or none within 3 months prior to enrollment were as likely to benefit from ARNI therapy with sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) as were those with a recent decompensation (JACC Heart Fail. 2016 Oct;4[10]:816-22). “A key message is that stability is an illusion in patients with symptomatic heart failure,”said Dr. Desai. “In PARADIGM-HF, the first event for about half of patients was not heralded by a worsening of symptoms or a heart failure hospitalization, it was an abrupt death at home. This may mean that a missed opportunity to optimize treatment may not come back to you down the road, so waiting until patients get worse in order to optimize their therapy may not be the best strategy.”

Inadequate laboratory monitoring

The MRAs, spironolactone and eplerenone (Inspra), are the GDMT drugs for which laboratory surveillance takes on the greatest importance because of their potential to induce hyperkalemia. The guidelines are clear that a potassium level and measurement of renal function should be obtained within a week of initiating therapy with an MRA, again at 4 weeks, and periodically thereafter.

“In general, this is done in clinical practice almost never,” Dr. Desai stressed.

These agents should be avoided in patients with prior hyperkalemia or advanced chronic kidney disease, and used with care in groups known to be at increased risk for hyperkalemia, including the elderly and patients with diabetes.

He considers spironolactone equivalent to eplerenone so long as the dosing is adequate. He generally reserves eplerenone for patients with poorly tolerated antiandrogenic effects on spironolactone.

Dr. Desai reported serving as a paid consultant to more than half a dozen pharmaceutical or medical device companies.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Many of the abundant missed opportunities to optimize pharmacotherapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction revolve around not getting fully on board with the guideline-directed medical therapy shown to be highly effective at improving clinical outcomes, Akshay S. Desai, MD, asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

“If you take nothing else away from this talk, is really quite profound,” declared Dr. Desai, director of the cardiomyopathy and heart failure program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and a cardiologist at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

He highlighted five common traps or pitfalls for physicians with regard to medical therapy of patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF):

Underutilization of guideline-directed medical therapy

The current ACC/American Heart Association/Heart Failure Society of America guidelines on heart failure management (Circulation. 2017 Aug 8;136[6]:e137-61) reflect 20 years of impressive progress in improving heart failure outcomes through the use of increasingly effective guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT). The magnitude of this improvement was nicely captured in a meta-analysis of 57 randomized controlled trials published during 1987-2015. The meta-analysis showed that, although ACE inhibitor therapy alone had no significant impact on all-cause mortality compared to placebo in patients with HFrEF, the sequential addition of guideline-directed drugs conferred stepwise improvements in survival. This approach culminated in a 56% reduction in all-cause mortality with the combination of an ACE inhibitor, beta-blocker, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA), compared with placebo, and a 63% reduction with an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), beta-blocker, and MRA (Circ Heart Fail. 2017 Jan;10(1). pii: e003529).

Moreover, the benefits of contemporary GDMT extend beyond reductions in all-cause mortality, death due to heart failure, and heart failure–related hospitalizations into areas where one wouldn’t necessarily have expected to see much benefit. For example, an analysis of data on more than 40,000 HFrEF patients in 12 clinical trials showed a sharp decline in the rate of sudden death over the years as new agents were incorporated into GDMT. The cumulative incidence of sudden death within 90 days after randomization plunged from 2.4% in the earliest trial to 1.0% in the most recent one (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 6;377[1]:41-51).

“We’re at the point where we now question whether routine use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in primary prevention patients with nonischemic heart failure is really worthwhile on the backdrop of effective medical therapy,” Dr. Desai observed.

But there’s a problem: “We don’t do a great job with GDMT, even with this incredible evidence base that we have,” the cardiologist said.

He cited a report from the CHAMP-HF registry that scrutinized the use of GDMT in more than 3,500 ambulatory HFrEF patients in 150 U.S. primary care and cardiology practices. It found that 67% of patients deemed eligible for an MRA weren’t on one. Neither were 33% with no contraindications to beta-blocker therapy and 27% who were eligible for an ACE inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), or ARNI (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jul 24;72[4]:351-66).

“This highlights a huge opportunity for further guideline-directed optimization of therapy,” he said.

Underdosing of GDMT

The CHAMP-HF registry contained further disappointing news regarding the state of treatment of patients with HFrEF in ambulatory settings: Among those patients who were on GDMT, very few were receiving the recommended target doses of the medications as established in major clinical trials and specified in the guidelines. Only 14% of patients on an ARNI were on the target dose, as were 28% on a beta-blocker, and 17% of those on an ACE inhibitor or ARB. And among patients who were eligible for all classes of GDMT, just 1% were simultaneously on the target doses of an MRA, beta-blocker, and ARNI, ACE inhibitor, or ARB. This despite solid evidence that, although some benefit is derived from initiating these medications, incremental benefit comes from dose titration.

“Even for those of us who feel like we do this quite well, if we examine our practices systematically – and we’ve done this in our own practices at Brigham and Women’s – you see that a lot of eligible patients aren’t on optimal therapy. And you might argue that many of them have contraindications, but even when you do a deep dive into the literature or the electronic medical record and ask the question – Why is this patient with normal renal function and normal potassium with class II HFrEF not on an MRA? – sometimes it’s hard to establish why that’s the case,” said Dr. Desai.

Interrupting GDMT during hospitalizations

This is common practice. But in fact, continuation of GDMT is generally well tolerated in the setting of acute decompensated heart failure in the absence of severe hypotension and cardiogenic shock. Moreover, in-hospital discontinuation or dose reduction is associated with increased risks of readmission and mortality.

And in treatment-naive HFrEF patients, what better place to introduce a medication and assess its tolerability than the hospital? Plus, medications prescribed at discharge are more likely to be continued in the outpatient setting, he noted.

Being seduced by the illusion of stability

The guidelines state that patients with NYHA class II or III HFrEF who tolerate an ACE inhibitor or ARB should be transitioned to an ARNI to further reduce their risk of morbidity and mortality. Yet many physicians wait to make the switch until clinical decompensation occurs. That’s a mistake, as was demonstrated in the landmark PARADIGM-HF trial. Twenty percent of study participants without a prior hospitalization for heart failure experienced cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization during the follow-up period. Patients who were clinically stable as defined by no prior heart failure hospitalization or none within 3 months prior to enrollment were as likely to benefit from ARNI therapy with sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) as were those with a recent decompensation (JACC Heart Fail. 2016 Oct;4[10]:816-22). “A key message is that stability is an illusion in patients with symptomatic heart failure,”said Dr. Desai. “In PARADIGM-HF, the first event for about half of patients was not heralded by a worsening of symptoms or a heart failure hospitalization, it was an abrupt death at home. This may mean that a missed opportunity to optimize treatment may not come back to you down the road, so waiting until patients get worse in order to optimize their therapy may not be the best strategy.”

Inadequate laboratory monitoring

The MRAs, spironolactone and eplerenone (Inspra), are the GDMT drugs for which laboratory surveillance takes on the greatest importance because of their potential to induce hyperkalemia. The guidelines are clear that a potassium level and measurement of renal function should be obtained within a week of initiating therapy with an MRA, again at 4 weeks, and periodically thereafter.

“In general, this is done in clinical practice almost never,” Dr. Desai stressed.

These agents should be avoided in patients with prior hyperkalemia or advanced chronic kidney disease, and used with care in groups known to be at increased risk for hyperkalemia, including the elderly and patients with diabetes.

He considers spironolactone equivalent to eplerenone so long as the dosing is adequate. He generally reserves eplerenone for patients with poorly tolerated antiandrogenic effects on spironolactone.

Dr. Desai reported serving as a paid consultant to more than half a dozen pharmaceutical or medical device companies.

REPORTING FROM ACC SNOWMASS 2019

Dupilumab to undergo FDA Priority Review for CRSwNP treatment

The Food and Drug Administration will conduct a Priority Review on the supplemental Biologics License Application (sBLA) for dupilumab (Dupixent) as an add-on treatment for adults with inadequately controlled severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP).

CRSwNP is a chronic disease of the upper airway in which patients can experience severe nasal obstruction with breathing difficulties, nasal discharge, reduction or loss of sense of smell and taste, and facial pain or pressure. There are currently no FDA-approved treatments for the disease, Regeneron said in the press release.

The sBLA is based on results from a pair of phase 3 trials in which patients with CRSwNP received either dupilumab plus a standard-of-care corticosteroid nasal spray or the standard-of-care spray alone. In results presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, dupilumab plus the spray improved nasal polyp size, nasal congestion severity, chronic sinus disease, sense of smell, and comorbid asthma outcomes while reducing the need for corticosteroid use and nasal/sinus surgery.

Dupilumab is currently approved in the United States to treat moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults whose disease is poorly controlled with topical agents and as a maintenance treatment in combination with other asthma medications in patients aged 12 years and older whose disease is not controlled with their current prescription. The most common adverse events include injection-site reactions, oropharyngeal pain, and cold sores.

The target action date for the FDA decision is June 26, 2019, Regeneron said.

Find the full press release on the Regeneron website.

The Food and Drug Administration will conduct a Priority Review on the supplemental Biologics License Application (sBLA) for dupilumab (Dupixent) as an add-on treatment for adults with inadequately controlled severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP).

CRSwNP is a chronic disease of the upper airway in which patients can experience severe nasal obstruction with breathing difficulties, nasal discharge, reduction or loss of sense of smell and taste, and facial pain or pressure. There are currently no FDA-approved treatments for the disease, Regeneron said in the press release.

The sBLA is based on results from a pair of phase 3 trials in which patients with CRSwNP received either dupilumab plus a standard-of-care corticosteroid nasal spray or the standard-of-care spray alone. In results presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, dupilumab plus the spray improved nasal polyp size, nasal congestion severity, chronic sinus disease, sense of smell, and comorbid asthma outcomes while reducing the need for corticosteroid use and nasal/sinus surgery.

Dupilumab is currently approved in the United States to treat moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults whose disease is poorly controlled with topical agents and as a maintenance treatment in combination with other asthma medications in patients aged 12 years and older whose disease is not controlled with their current prescription. The most common adverse events include injection-site reactions, oropharyngeal pain, and cold sores.

The target action date for the FDA decision is June 26, 2019, Regeneron said.

Find the full press release on the Regeneron website.

The Food and Drug Administration will conduct a Priority Review on the supplemental Biologics License Application (sBLA) for dupilumab (Dupixent) as an add-on treatment for adults with inadequately controlled severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP).

CRSwNP is a chronic disease of the upper airway in which patients can experience severe nasal obstruction with breathing difficulties, nasal discharge, reduction or loss of sense of smell and taste, and facial pain or pressure. There are currently no FDA-approved treatments for the disease, Regeneron said in the press release.

The sBLA is based on results from a pair of phase 3 trials in which patients with CRSwNP received either dupilumab plus a standard-of-care corticosteroid nasal spray or the standard-of-care spray alone. In results presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, dupilumab plus the spray improved nasal polyp size, nasal congestion severity, chronic sinus disease, sense of smell, and comorbid asthma outcomes while reducing the need for corticosteroid use and nasal/sinus surgery.

Dupilumab is currently approved in the United States to treat moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults whose disease is poorly controlled with topical agents and as a maintenance treatment in combination with other asthma medications in patients aged 12 years and older whose disease is not controlled with their current prescription. The most common adverse events include injection-site reactions, oropharyngeal pain, and cold sores.

The target action date for the FDA decision is June 26, 2019, Regeneron said.

Find the full press release on the Regeneron website.

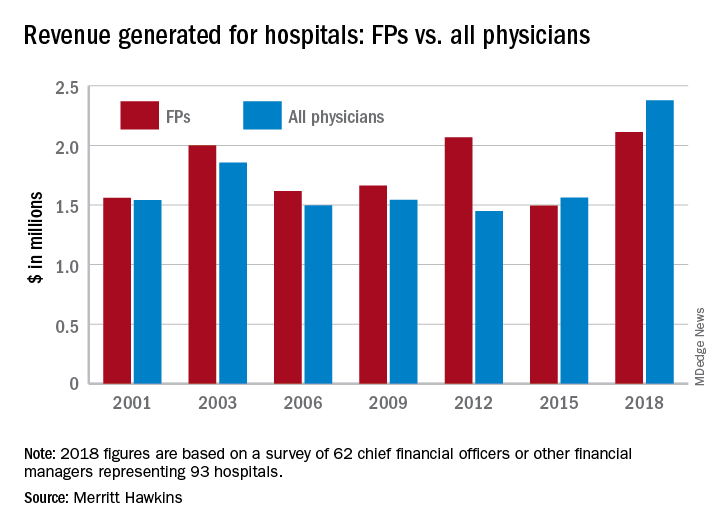

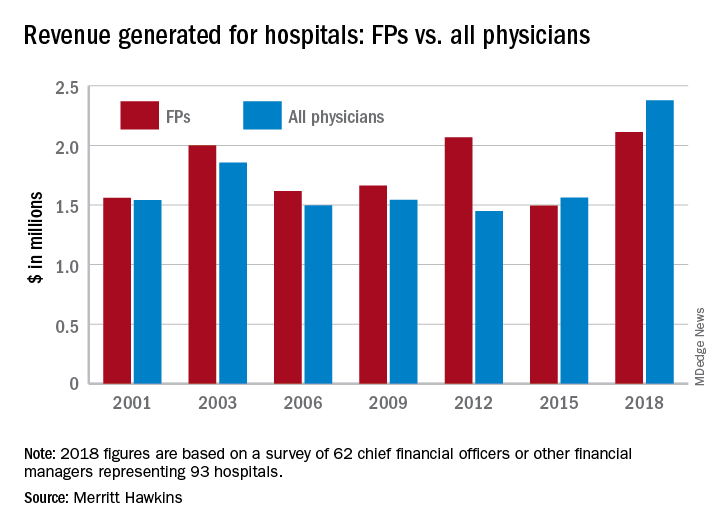

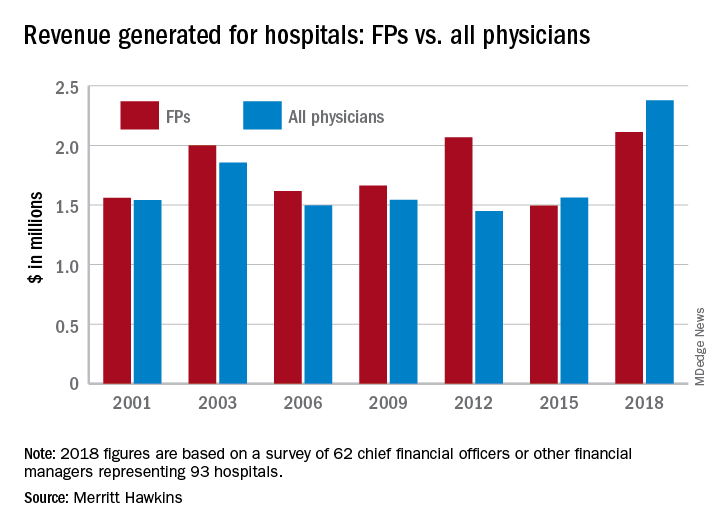

For FPs, 2018 was a big year for generating hospital revenue

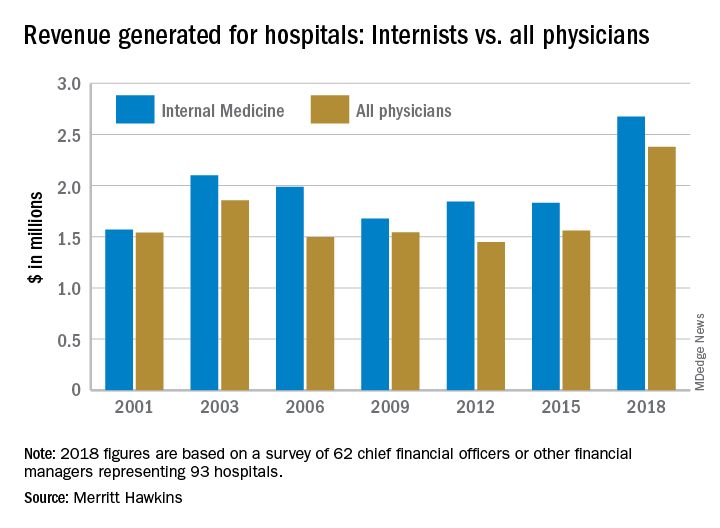

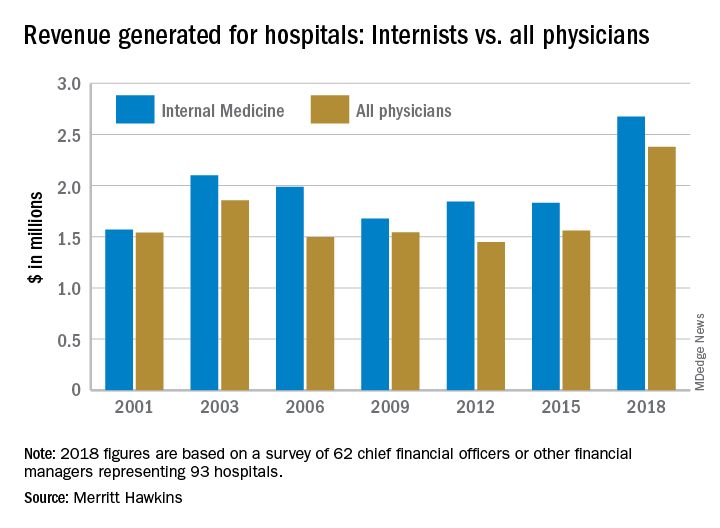

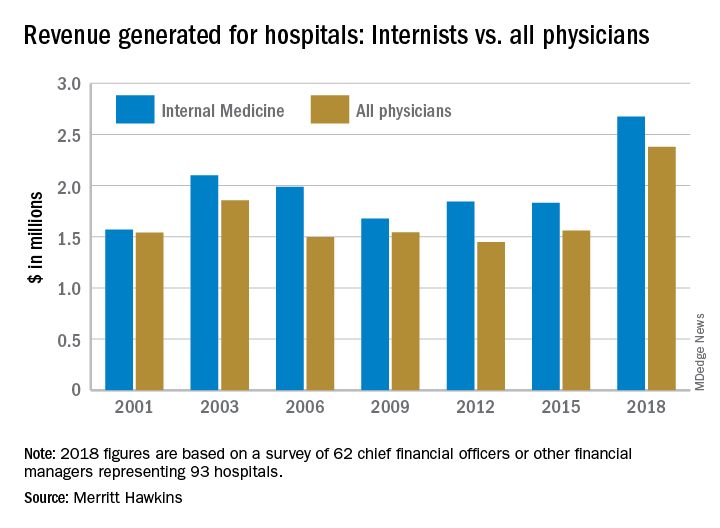

Physicians continue to be the major drivers of hospital revenue, and according to a new survey by physician search firm Merritt Hawkins.

“The value of physician care is not only related to the quality of patient outcomes,” Travis Singleton, the company’s executive vice president, said in a written statement. “Physicians continue to drive the financial health and viability of hospitals, even in a health care system that is evolving towards value-based payments.”

Family physicians generated an average of $2.11 million for their affiliated hospitals last year, which was up by 41% over 2015 (the survey is conducted every 3 years) and even managed to top the previous FP high of $2.07 million in 2012, Merritt Hawkins reported.

Primary care physicians as a group averaged just over $2.13 million in revenue in 2018, compared with almost $2.45 million for specialists, which “suggests that emerging value-based delivery models have yet to inhibit the revenue generating power of physician specialists,” the report said. The average revenue for physicians in all 19 specialties in the survey was almost $2.38 million, an increase of 52% since Merritt Hawkins’ last survey.

The current survey was conducted from October to December 2018 and is based on responses from 62 chief financial officers or other financial managers who represented 93 hospitals. Responses from smaller hospitals (0-99 beds) were “somewhat overrepresented in the survey” relative to their number nationwide, Merritt Hawkins said.

Physicians continue to be the major drivers of hospital revenue, and according to a new survey by physician search firm Merritt Hawkins.

“The value of physician care is not only related to the quality of patient outcomes,” Travis Singleton, the company’s executive vice president, said in a written statement. “Physicians continue to drive the financial health and viability of hospitals, even in a health care system that is evolving towards value-based payments.”

Family physicians generated an average of $2.11 million for their affiliated hospitals last year, which was up by 41% over 2015 (the survey is conducted every 3 years) and even managed to top the previous FP high of $2.07 million in 2012, Merritt Hawkins reported.

Primary care physicians as a group averaged just over $2.13 million in revenue in 2018, compared with almost $2.45 million for specialists, which “suggests that emerging value-based delivery models have yet to inhibit the revenue generating power of physician specialists,” the report said. The average revenue for physicians in all 19 specialties in the survey was almost $2.38 million, an increase of 52% since Merritt Hawkins’ last survey.

The current survey was conducted from October to December 2018 and is based on responses from 62 chief financial officers or other financial managers who represented 93 hospitals. Responses from smaller hospitals (0-99 beds) were “somewhat overrepresented in the survey” relative to their number nationwide, Merritt Hawkins said.

Physicians continue to be the major drivers of hospital revenue, and according to a new survey by physician search firm Merritt Hawkins.

“The value of physician care is not only related to the quality of patient outcomes,” Travis Singleton, the company’s executive vice president, said in a written statement. “Physicians continue to drive the financial health and viability of hospitals, even in a health care system that is evolving towards value-based payments.”

Family physicians generated an average of $2.11 million for their affiliated hospitals last year, which was up by 41% over 2015 (the survey is conducted every 3 years) and even managed to top the previous FP high of $2.07 million in 2012, Merritt Hawkins reported.

Primary care physicians as a group averaged just over $2.13 million in revenue in 2018, compared with almost $2.45 million for specialists, which “suggests that emerging value-based delivery models have yet to inhibit the revenue generating power of physician specialists,” the report said. The average revenue for physicians in all 19 specialties in the survey was almost $2.38 million, an increase of 52% since Merritt Hawkins’ last survey.

The current survey was conducted from October to December 2018 and is based on responses from 62 chief financial officers or other financial managers who represented 93 hospitals. Responses from smaller hospitals (0-99 beds) were “somewhat overrepresented in the survey” relative to their number nationwide, Merritt Hawkins said.

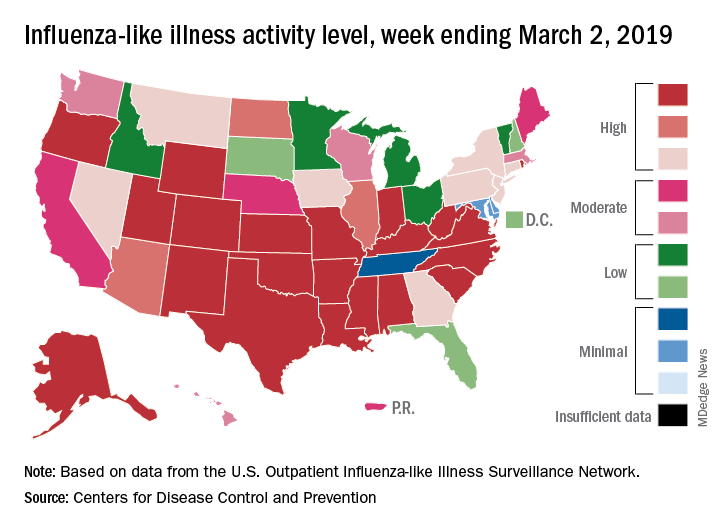

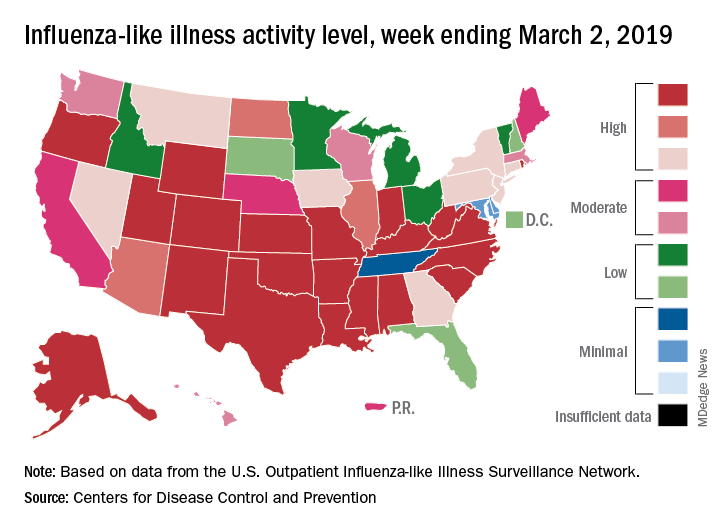

Flu activity down for a second straight week

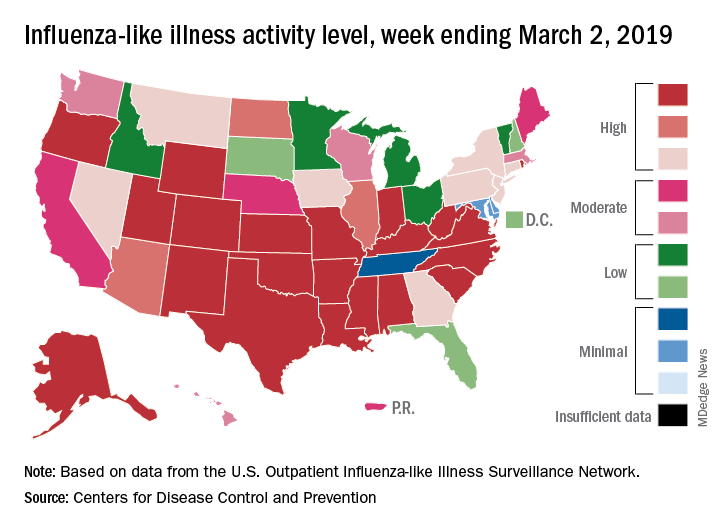

A second straight week of reduced influenza activity suggests that the 2018-2019 flu season is on the decline, according to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 4.7% during the week ending March 2, which means that, thanks to a revision of the number for the previous week (Feb. 23) from 5.0% down to 4.9%, there have been two straight weeks of declines since outpatient visits reached a season-high 5.0% for the week ending Feb. 16, the CDC’s influenza division said March 8. The national baseline level is 2.2%.

This marks the second 2-week drop in ILI visits for the 2018-2019 season, as there was similar dip in the beginning of January before activity started rising again.

This compares with 24 the week before; 32 states were in the high range of 8-10, compared with the 33 reported last week, based on data from the Outpatient ILI Surveillance Network.

There were nine flu-related pediatric deaths reported during the week, with three occurring in the week ending March 2. To underscore the preliminary nature of these data, one of the deaths reported this week occurred in 2016. A total of 64 deaths in children have been associated with influenza so far for the 2018-2019 season, and the total for the 2015-2016 season is now 95, the CDC said.

A second straight week of reduced influenza activity suggests that the 2018-2019 flu season is on the decline, according to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 4.7% during the week ending March 2, which means that, thanks to a revision of the number for the previous week (Feb. 23) from 5.0% down to 4.9%, there have been two straight weeks of declines since outpatient visits reached a season-high 5.0% for the week ending Feb. 16, the CDC’s influenza division said March 8. The national baseline level is 2.2%.

This marks the second 2-week drop in ILI visits for the 2018-2019 season, as there was similar dip in the beginning of January before activity started rising again.

This compares with 24 the week before; 32 states were in the high range of 8-10, compared with the 33 reported last week, based on data from the Outpatient ILI Surveillance Network.

There were nine flu-related pediatric deaths reported during the week, with three occurring in the week ending March 2. To underscore the preliminary nature of these data, one of the deaths reported this week occurred in 2016. A total of 64 deaths in children have been associated with influenza so far for the 2018-2019 season, and the total for the 2015-2016 season is now 95, the CDC said.

A second straight week of reduced influenza activity suggests that the 2018-2019 flu season is on the decline, according to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 4.7% during the week ending March 2, which means that, thanks to a revision of the number for the previous week (Feb. 23) from 5.0% down to 4.9%, there have been two straight weeks of declines since outpatient visits reached a season-high 5.0% for the week ending Feb. 16, the CDC’s influenza division said March 8. The national baseline level is 2.2%.

This marks the second 2-week drop in ILI visits for the 2018-2019 season, as there was similar dip in the beginning of January before activity started rising again.

This compares with 24 the week before; 32 states were in the high range of 8-10, compared with the 33 reported last week, based on data from the Outpatient ILI Surveillance Network.

There were nine flu-related pediatric deaths reported during the week, with three occurring in the week ending March 2. To underscore the preliminary nature of these data, one of the deaths reported this week occurred in 2016. A total of 64 deaths in children have been associated with influenza so far for the 2018-2019 season, and the total for the 2015-2016 season is now 95, the CDC said.

Hepatitis vaccination update

One of the most important commitments family physicians can undertake in protecting the health of their patients and communities is to ensure that their patients are fully vaccinated. This task is increasingly complicated as new vaccines are approved every year and recommendations change regarding new and established vaccines. To assist primary care providers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) annually updates 2 immunization schedules—one for children and adolescents, and one for adults. These schedules are available on the CDC Web site (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/index.html).

These updates originate from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which meets 3 times a year to consider and adopt changes to the schedules. During 2018, relatively few new recommendations were adopted. The September 2018 Practice Alert1 in this journal covered the updated recommendations for influenza immunization, which included reinstating live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) to the active list of influenza vaccines.

This current Practice Alert reviews 3 additional updates: 1) a new hepatitis B (HepB) vaccine; 2) updated recommendations for the use of hepatitis A (HepA) vaccine for post-exposure prevention and before travel; and 3) inclusion of the homeless among those who should be routinely vaccinated with HepA vaccine.

Hepatitis B: New 2-dose product

As of 2015, the annual incidence of new hepatitis B cases had declined by 88.5% since the first HepB vaccine was licensed in 1981 and recommendations for its routine use were issued in 1982.2 The HepB vaccine products available in the United States are 2 single-antigen products, Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.). Both can be used in all age groups, starting at birth, in a 3-dose series. HepB vaccine is also available in 2 combination products: Pediarix, containing HepB, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis, and inactivated poliovirus (GlaxoSmithKline), approved for use in children 6 weeks to 6 years old; and Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline), which contains both HepB and HepA and is approved for use in adults 18 years and older.

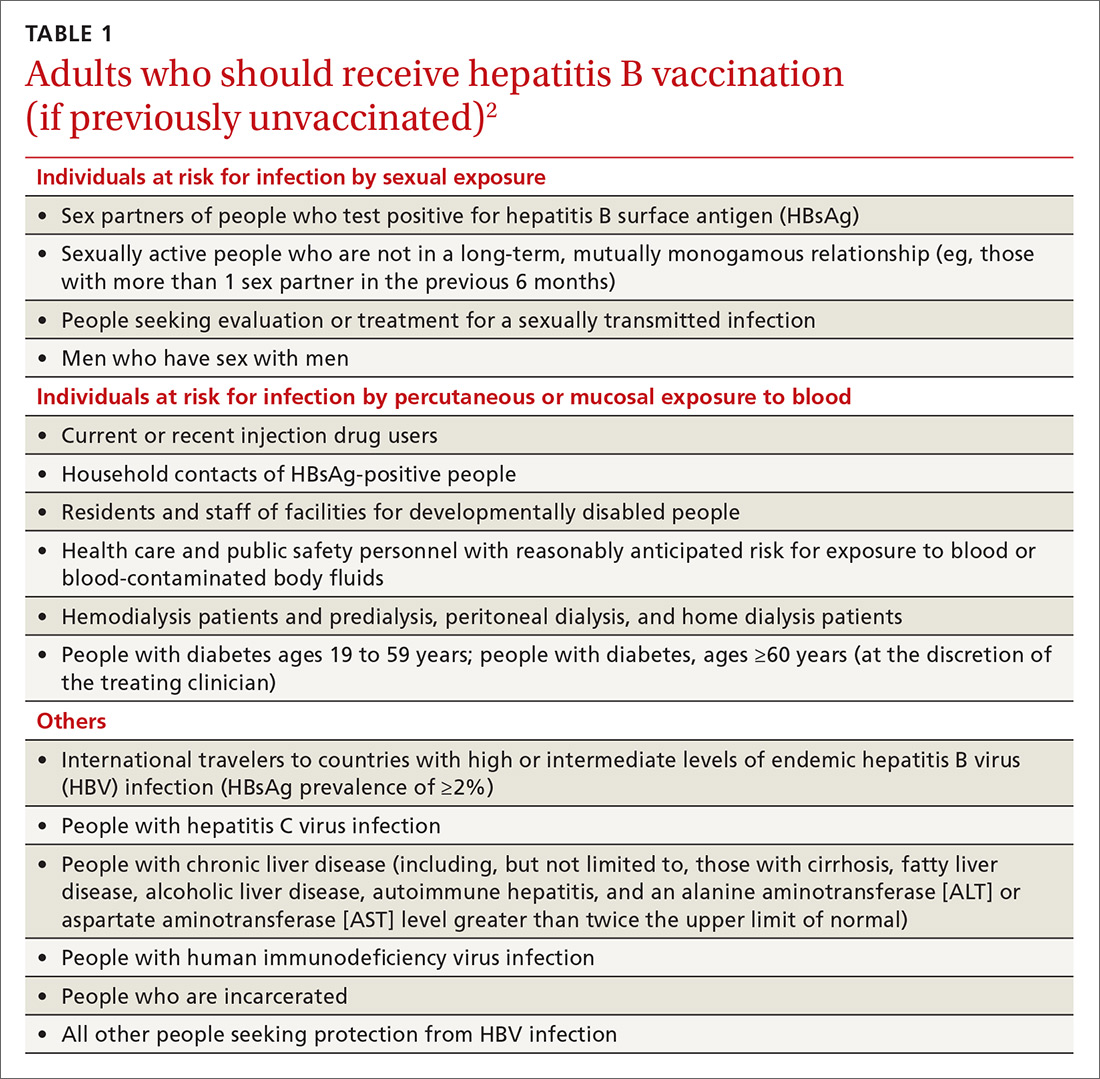

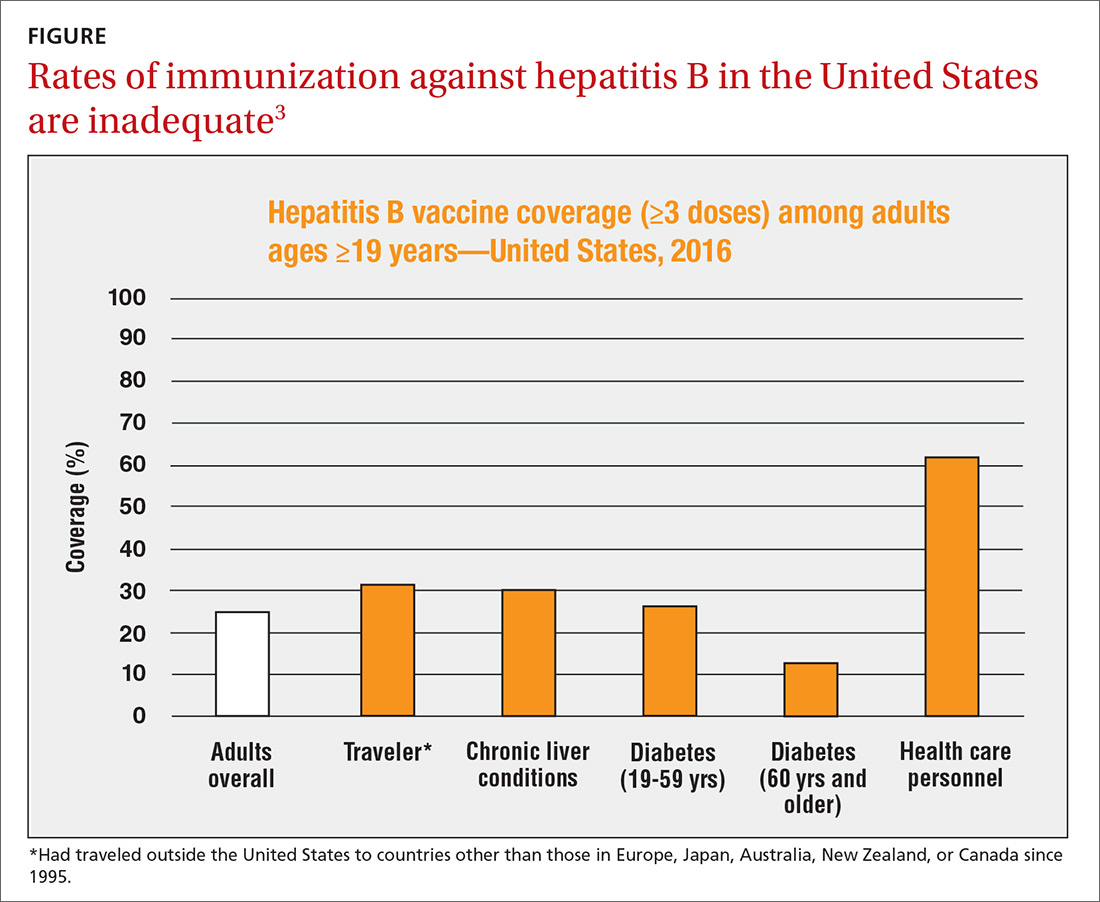

The HepB vaccine is recommended for all children and unvaccinated adolescents as part of the routine vaccination schedule. It is also recommended for unvaccinated adults with specific risks (TABLE 12). However, the rate of HepB vaccination in adults for whom it is recommended is suboptimal (FIGURE),3 and just a little more than half of adults who start a 3-dose series of HepB complete it.4A new vaccine against hepatitis B, HEPLISAV-B (Dynavax Technologies), was licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration in late 2017. ACIP now recommends it as an option along with other available HepB products. HEPLISAV-B is given in 2 doses separated by 1 month. It is hoped that this shortened 2-dose series will increase the number of adults who achieve full vaccination. In addition, it appears that HEPLISAV-B provides higher levels of protection in some high-risk groups—those with type 2 diabetes or chronic kidney disease.3 However, initial safety studies have shown a small absolute increase in cardiac events after vaccination with HEPLISAV-B. Post-marketing surveillance will be needed to show whether this is causal or coincidental.3

As with other HepB products, use of HEPLISAV-B should follow the latest CDC directives on who to test serologically for prior immunity, and on post-vaccination testing to ensure protective antibody levels were achieved.2 It is best to complete a HepB series with the same product, but, if necessary, a combination of products at different doses can be used to complete the HepB series. Any such combination should include 3 doses, even if one of the doses is HEPLISAV-B.

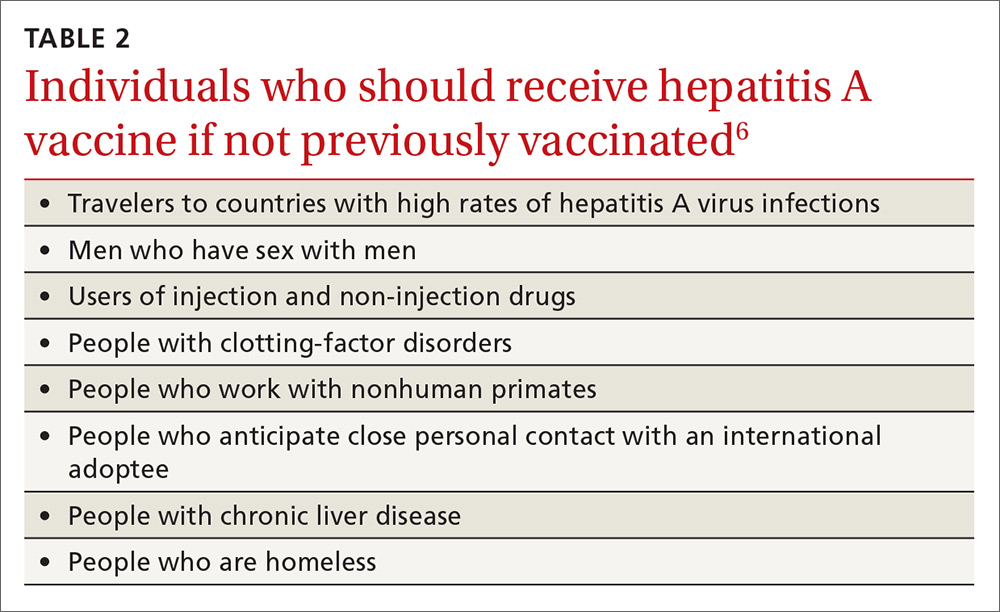

Hepatitis A: Vaccination assumes greater importance for more people

A Practice Alert in early 2018 described a series of outbreaks of hepatitis A around the country and the high rates of associated hospitalizations.5 These outbreaks have occurred primarily among the homeless and their contacts and those who use illicit drugs. This nationwide outbreak has now spread, resulting in more than 7500 cases since July 1, 2016.6 The progress of this epidemic can be viewed on the CDC Web site

Continue to: Remember that the current recommendation...

Remember that the current recommendation is to vaccinate all children 12 to 23 months old with HepA, in 2 separate doses. Two single-antigen HepA products are available: Havrix (GSK) and Vaqta (Merck). For the 2-dose sequence, Havrix is given at 0 and 6 to 12 months; Vaqta at 0 and 6 to 18 months. Even a single dose will provide protection for up to 11 years. In addition to these vaccines, there is the combination HepA and HepB vaccine (Twinrix) mentioned earlier.

Previous recommendations for preventing hepatitis A after exposure, made in 2007, stated that HepA vaccine was preferred for healthy individuals ages 12 months through 40 years, while immune globulin (IG) was preferred for adults older than 40, infants before their first birthday, immunocompromised individuals, those with chronic liver disease, and those for whom HepA vaccine is contraindicated.8 The 2007 recommendations also advised vaccinating individuals traveling to countries with intermediate to high hepatitis A endemicity.

A single dose of HepA vaccine was recommended for all those 12 months or older, although older adults, immunocompromised individuals, and those with chronic liver disease or other chronic medical conditions planning to visit an endemic area in ≤ 2 weeks were supposed to receive the initial dose of vaccine and could also receive IG (0.02 mL/kg) if their provider advised it. Travelers who declined vaccination, those younger than 12 months, or those allergic to a vaccine component could receive a single dose of IG (0.02 mL/kg), which provides protection up to 3 months.

Several factors influenced ACIP to reconsider both the pre- and post-exposure recommendations. Regarding IG, evidence of its decreased potency over time led the committee to increase the recommended dose (see below). IG also must be re-administered every 2 months, the supply of the product is questionable, and many health care facilities do not stock it. By comparison, HepA vaccine offers the advantages of easier administration, inducing active immunity, and providing longer protection. Another issue involved infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling to an area with endemic measles transmission and who must therefore receive the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. MMR and IG should not be co-administered, and, for infants, the health risk from measles outweighs that from hepatitis A.

Updated recommendations. After considering all this information, ACIP made the following changes to its hepatitis A virus (HAV) prevention recommendations (in addition to adding homeless people to the list of HepA vaccine recipients)9:

- Administer HepA vaccine as post-exposure prophylaxis to all individuals 12 months and older.

- IG may be administered, in addition to HepA vaccine, to those older than 40 years, depending on the provider’s risk assessment (degree of exposure and medical conditions that might lead to severe complications from HAV infection). The recommended IG dose is now 0.1 mL/kg for post-exposure prevention; it is 0.1 to 0.2 mL/kg for pre-exposure prophylaxis for travelers, depending on the length of planned travel.

- Administer HepA vaccine alone to infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling outside the United States when protection against hepatitis A is recommended.

These recommendations have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.9

1. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC recommendations for the 2018-2019 influenza season. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:550-553.

2. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-31.

3. CDC. Schillie S. HEPLISAV-B: considerations and proposed recommendations, vote. Presented at: meeting of the Hepatitis Work Group, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 21, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-02/Hepatitis-03-Schillie-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

4. Nelson JC, Bittner RC, Bounds L, et al. Compliance with multiple-dose vaccine schedules among older children, adolescents, and adults: results from a vaccine safety datalink study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 2):S389-S397.

5. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC provides advice on recent hepatitis A outbreaks. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:30-32.

6. CDC. Nelson N. Background – hepatitis A among the homeless. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; October 24, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-10/Hepatitis-02-Nelson-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

7. CDC. 2017 – Outbreaks of hepatitis A in multiple states among people who use drugs and/or people who are homeless. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/2017March-HepatitisA.htm. Accessed January 19, 2019.

8. CDC. Update: Prevention of hepatitis A after exposure to hepatitis A virus and in international travelers. Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1080-1084. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5641a3.htm. Accessed February 9, 2019.

9. Nelson NP, Link-Gelles R, Hofmeister MG, et al. Update: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of hepatitis A vaccine for postexposure prophylaxis and for preexposure prophylaxis for international travel. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1216-1220.

One of the most important commitments family physicians can undertake in protecting the health of their patients and communities is to ensure that their patients are fully vaccinated. This task is increasingly complicated as new vaccines are approved every year and recommendations change regarding new and established vaccines. To assist primary care providers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) annually updates 2 immunization schedules—one for children and adolescents, and one for adults. These schedules are available on the CDC Web site (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/index.html).

These updates originate from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which meets 3 times a year to consider and adopt changes to the schedules. During 2018, relatively few new recommendations were adopted. The September 2018 Practice Alert1 in this journal covered the updated recommendations for influenza immunization, which included reinstating live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) to the active list of influenza vaccines.

This current Practice Alert reviews 3 additional updates: 1) a new hepatitis B (HepB) vaccine; 2) updated recommendations for the use of hepatitis A (HepA) vaccine for post-exposure prevention and before travel; and 3) inclusion of the homeless among those who should be routinely vaccinated with HepA vaccine.

Hepatitis B: New 2-dose product

As of 2015, the annual incidence of new hepatitis B cases had declined by 88.5% since the first HepB vaccine was licensed in 1981 and recommendations for its routine use were issued in 1982.2 The HepB vaccine products available in the United States are 2 single-antigen products, Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.). Both can be used in all age groups, starting at birth, in a 3-dose series. HepB vaccine is also available in 2 combination products: Pediarix, containing HepB, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis, and inactivated poliovirus (GlaxoSmithKline), approved for use in children 6 weeks to 6 years old; and Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline), which contains both HepB and HepA and is approved for use in adults 18 years and older.

The HepB vaccine is recommended for all children and unvaccinated adolescents as part of the routine vaccination schedule. It is also recommended for unvaccinated adults with specific risks (TABLE 12). However, the rate of HepB vaccination in adults for whom it is recommended is suboptimal (FIGURE),3 and just a little more than half of adults who start a 3-dose series of HepB complete it.4A new vaccine against hepatitis B, HEPLISAV-B (Dynavax Technologies), was licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration in late 2017. ACIP now recommends it as an option along with other available HepB products. HEPLISAV-B is given in 2 doses separated by 1 month. It is hoped that this shortened 2-dose series will increase the number of adults who achieve full vaccination. In addition, it appears that HEPLISAV-B provides higher levels of protection in some high-risk groups—those with type 2 diabetes or chronic kidney disease.3 However, initial safety studies have shown a small absolute increase in cardiac events after vaccination with HEPLISAV-B. Post-marketing surveillance will be needed to show whether this is causal or coincidental.3

As with other HepB products, use of HEPLISAV-B should follow the latest CDC directives on who to test serologically for prior immunity, and on post-vaccination testing to ensure protective antibody levels were achieved.2 It is best to complete a HepB series with the same product, but, if necessary, a combination of products at different doses can be used to complete the HepB series. Any such combination should include 3 doses, even if one of the doses is HEPLISAV-B.

Hepatitis A: Vaccination assumes greater importance for more people

A Practice Alert in early 2018 described a series of outbreaks of hepatitis A around the country and the high rates of associated hospitalizations.5 These outbreaks have occurred primarily among the homeless and their contacts and those who use illicit drugs. This nationwide outbreak has now spread, resulting in more than 7500 cases since July 1, 2016.6 The progress of this epidemic can be viewed on the CDC Web site

Continue to: Remember that the current recommendation...

Remember that the current recommendation is to vaccinate all children 12 to 23 months old with HepA, in 2 separate doses. Two single-antigen HepA products are available: Havrix (GSK) and Vaqta (Merck). For the 2-dose sequence, Havrix is given at 0 and 6 to 12 months; Vaqta at 0 and 6 to 18 months. Even a single dose will provide protection for up to 11 years. In addition to these vaccines, there is the combination HepA and HepB vaccine (Twinrix) mentioned earlier.

Previous recommendations for preventing hepatitis A after exposure, made in 2007, stated that HepA vaccine was preferred for healthy individuals ages 12 months through 40 years, while immune globulin (IG) was preferred for adults older than 40, infants before their first birthday, immunocompromised individuals, those with chronic liver disease, and those for whom HepA vaccine is contraindicated.8 The 2007 recommendations also advised vaccinating individuals traveling to countries with intermediate to high hepatitis A endemicity.

A single dose of HepA vaccine was recommended for all those 12 months or older, although older adults, immunocompromised individuals, and those with chronic liver disease or other chronic medical conditions planning to visit an endemic area in ≤ 2 weeks were supposed to receive the initial dose of vaccine and could also receive IG (0.02 mL/kg) if their provider advised it. Travelers who declined vaccination, those younger than 12 months, or those allergic to a vaccine component could receive a single dose of IG (0.02 mL/kg), which provides protection up to 3 months.

Several factors influenced ACIP to reconsider both the pre- and post-exposure recommendations. Regarding IG, evidence of its decreased potency over time led the committee to increase the recommended dose (see below). IG also must be re-administered every 2 months, the supply of the product is questionable, and many health care facilities do not stock it. By comparison, HepA vaccine offers the advantages of easier administration, inducing active immunity, and providing longer protection. Another issue involved infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling to an area with endemic measles transmission and who must therefore receive the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. MMR and IG should not be co-administered, and, for infants, the health risk from measles outweighs that from hepatitis A.

Updated recommendations. After considering all this information, ACIP made the following changes to its hepatitis A virus (HAV) prevention recommendations (in addition to adding homeless people to the list of HepA vaccine recipients)9:

- Administer HepA vaccine as post-exposure prophylaxis to all individuals 12 months and older.

- IG may be administered, in addition to HepA vaccine, to those older than 40 years, depending on the provider’s risk assessment (degree of exposure and medical conditions that might lead to severe complications from HAV infection). The recommended IG dose is now 0.1 mL/kg for post-exposure prevention; it is 0.1 to 0.2 mL/kg for pre-exposure prophylaxis for travelers, depending on the length of planned travel.

- Administer HepA vaccine alone to infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling outside the United States when protection against hepatitis A is recommended.

These recommendations have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.9

One of the most important commitments family physicians can undertake in protecting the health of their patients and communities is to ensure that their patients are fully vaccinated. This task is increasingly complicated as new vaccines are approved every year and recommendations change regarding new and established vaccines. To assist primary care providers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) annually updates 2 immunization schedules—one for children and adolescents, and one for adults. These schedules are available on the CDC Web site (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/index.html).

These updates originate from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which meets 3 times a year to consider and adopt changes to the schedules. During 2018, relatively few new recommendations were adopted. The September 2018 Practice Alert1 in this journal covered the updated recommendations for influenza immunization, which included reinstating live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) to the active list of influenza vaccines.

This current Practice Alert reviews 3 additional updates: 1) a new hepatitis B (HepB) vaccine; 2) updated recommendations for the use of hepatitis A (HepA) vaccine for post-exposure prevention and before travel; and 3) inclusion of the homeless among those who should be routinely vaccinated with HepA vaccine.

Hepatitis B: New 2-dose product

As of 2015, the annual incidence of new hepatitis B cases had declined by 88.5% since the first HepB vaccine was licensed in 1981 and recommendations for its routine use were issued in 1982.2 The HepB vaccine products available in the United States are 2 single-antigen products, Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.). Both can be used in all age groups, starting at birth, in a 3-dose series. HepB vaccine is also available in 2 combination products: Pediarix, containing HepB, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis, and inactivated poliovirus (GlaxoSmithKline), approved for use in children 6 weeks to 6 years old; and Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline), which contains both HepB and HepA and is approved for use in adults 18 years and older.

The HepB vaccine is recommended for all children and unvaccinated adolescents as part of the routine vaccination schedule. It is also recommended for unvaccinated adults with specific risks (TABLE 12). However, the rate of HepB vaccination in adults for whom it is recommended is suboptimal (FIGURE),3 and just a little more than half of adults who start a 3-dose series of HepB complete it.4A new vaccine against hepatitis B, HEPLISAV-B (Dynavax Technologies), was licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration in late 2017. ACIP now recommends it as an option along with other available HepB products. HEPLISAV-B is given in 2 doses separated by 1 month. It is hoped that this shortened 2-dose series will increase the number of adults who achieve full vaccination. In addition, it appears that HEPLISAV-B provides higher levels of protection in some high-risk groups—those with type 2 diabetes or chronic kidney disease.3 However, initial safety studies have shown a small absolute increase in cardiac events after vaccination with HEPLISAV-B. Post-marketing surveillance will be needed to show whether this is causal or coincidental.3

As with other HepB products, use of HEPLISAV-B should follow the latest CDC directives on who to test serologically for prior immunity, and on post-vaccination testing to ensure protective antibody levels were achieved.2 It is best to complete a HepB series with the same product, but, if necessary, a combination of products at different doses can be used to complete the HepB series. Any such combination should include 3 doses, even if one of the doses is HEPLISAV-B.

Hepatitis A: Vaccination assumes greater importance for more people

A Practice Alert in early 2018 described a series of outbreaks of hepatitis A around the country and the high rates of associated hospitalizations.5 These outbreaks have occurred primarily among the homeless and their contacts and those who use illicit drugs. This nationwide outbreak has now spread, resulting in more than 7500 cases since July 1, 2016.6 The progress of this epidemic can be viewed on the CDC Web site

Continue to: Remember that the current recommendation...

Remember that the current recommendation is to vaccinate all children 12 to 23 months old with HepA, in 2 separate doses. Two single-antigen HepA products are available: Havrix (GSK) and Vaqta (Merck). For the 2-dose sequence, Havrix is given at 0 and 6 to 12 months; Vaqta at 0 and 6 to 18 months. Even a single dose will provide protection for up to 11 years. In addition to these vaccines, there is the combination HepA and HepB vaccine (Twinrix) mentioned earlier.

Previous recommendations for preventing hepatitis A after exposure, made in 2007, stated that HepA vaccine was preferred for healthy individuals ages 12 months through 40 years, while immune globulin (IG) was preferred for adults older than 40, infants before their first birthday, immunocompromised individuals, those with chronic liver disease, and those for whom HepA vaccine is contraindicated.8 The 2007 recommendations also advised vaccinating individuals traveling to countries with intermediate to high hepatitis A endemicity.

A single dose of HepA vaccine was recommended for all those 12 months or older, although older adults, immunocompromised individuals, and those with chronic liver disease or other chronic medical conditions planning to visit an endemic area in ≤ 2 weeks were supposed to receive the initial dose of vaccine and could also receive IG (0.02 mL/kg) if their provider advised it. Travelers who declined vaccination, those younger than 12 months, or those allergic to a vaccine component could receive a single dose of IG (0.02 mL/kg), which provides protection up to 3 months.

Several factors influenced ACIP to reconsider both the pre- and post-exposure recommendations. Regarding IG, evidence of its decreased potency over time led the committee to increase the recommended dose (see below). IG also must be re-administered every 2 months, the supply of the product is questionable, and many health care facilities do not stock it. By comparison, HepA vaccine offers the advantages of easier administration, inducing active immunity, and providing longer protection. Another issue involved infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling to an area with endemic measles transmission and who must therefore receive the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. MMR and IG should not be co-administered, and, for infants, the health risk from measles outweighs that from hepatitis A.

Updated recommendations. After considering all this information, ACIP made the following changes to its hepatitis A virus (HAV) prevention recommendations (in addition to adding homeless people to the list of HepA vaccine recipients)9:

- Administer HepA vaccine as post-exposure prophylaxis to all individuals 12 months and older.

- IG may be administered, in addition to HepA vaccine, to those older than 40 years, depending on the provider’s risk assessment (degree of exposure and medical conditions that might lead to severe complications from HAV infection). The recommended IG dose is now 0.1 mL/kg for post-exposure prevention; it is 0.1 to 0.2 mL/kg for pre-exposure prophylaxis for travelers, depending on the length of planned travel.

- Administer HepA vaccine alone to infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling outside the United States when protection against hepatitis A is recommended.

These recommendations have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.9

1. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC recommendations for the 2018-2019 influenza season. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:550-553.

2. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-31.

3. CDC. Schillie S. HEPLISAV-B: considerations and proposed recommendations, vote. Presented at: meeting of the Hepatitis Work Group, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 21, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-02/Hepatitis-03-Schillie-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

4. Nelson JC, Bittner RC, Bounds L, et al. Compliance with multiple-dose vaccine schedules among older children, adolescents, and adults: results from a vaccine safety datalink study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 2):S389-S397.

5. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC provides advice on recent hepatitis A outbreaks. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:30-32.

6. CDC. Nelson N. Background – hepatitis A among the homeless. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; October 24, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-10/Hepatitis-02-Nelson-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

7. CDC. 2017 – Outbreaks of hepatitis A in multiple states among people who use drugs and/or people who are homeless. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/2017March-HepatitisA.htm. Accessed January 19, 2019.

8. CDC. Update: Prevention of hepatitis A after exposure to hepatitis A virus and in international travelers. Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1080-1084. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5641a3.htm. Accessed February 9, 2019.

9. Nelson NP, Link-Gelles R, Hofmeister MG, et al. Update: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of hepatitis A vaccine for postexposure prophylaxis and for preexposure prophylaxis for international travel. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1216-1220.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC recommendations for the 2018-2019 influenza season. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:550-553.

2. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-31.

3. CDC. Schillie S. HEPLISAV-B: considerations and proposed recommendations, vote. Presented at: meeting of the Hepatitis Work Group, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 21, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-02/Hepatitis-03-Schillie-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

4. Nelson JC, Bittner RC, Bounds L, et al. Compliance with multiple-dose vaccine schedules among older children, adolescents, and adults: results from a vaccine safety datalink study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 2):S389-S397.

5. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC provides advice on recent hepatitis A outbreaks. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:30-32.

6. CDC. Nelson N. Background – hepatitis A among the homeless. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; October 24, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-10/Hepatitis-02-Nelson-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

7. CDC. 2017 – Outbreaks of hepatitis A in multiple states among people who use drugs and/or people who are homeless. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/2017March-HepatitisA.htm. Accessed January 19, 2019.

8. CDC. Update: Prevention of hepatitis A after exposure to hepatitis A virus and in international travelers. Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1080-1084. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5641a3.htm. Accessed February 9, 2019.

9. Nelson NP, Link-Gelles R, Hofmeister MG, et al. Update: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of hepatitis A vaccine for postexposure prophylaxis and for preexposure prophylaxis for international travel. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1216-1220.

Best practices lower postsepsis risk, but only if implemented

SAN DIEGO – North Carolina health care workers often failed to provide best-practice follow-up to patients who were released after hospitalization for sepsis, a small study has found. There may be a cost to this gap:

“It’s disappointing to see that we are not providing these seemingly common-sense care processes to our sepsis patients at discharge,” said study lead author Stephanie Parks Taylor, MD, of Atrium Health’s Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, in an interview following the presentation of the study findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. “We need to develop and implement strategies to improve outcomes for sepsis patients, not just while they are in the hospital, but after discharge as well.”

A 2017 report estimated that 1.7 million adults were hospitalized for sepsis in the United States in 2014, and 270,000 died (JAMA. 2017;318[13]:1241-9). Age-adjusted sepsis death rates in the United States are highest in states in the Eastern and Southern regions, a 2017 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggested; North Carolina has the 32nd-worst sepsis death rate in the country (12.4 deaths per 100,000 population).

Dr. Taylor said some recent news about sepsis is promising. “We’ve seen decreasing mortality rates from initiatives that improve the early detection of sepsis and rapid delivery of antibiotics, fluids, and other treatment. However, there is growing evidence that patients who survive an episode of sepsis face residual health deficits. Many sepsis survivors are left with new functional, cognitive, or mental health declines or worsening of their underlying comorbidities. Unfortunately, these patients have high rates of mortality and hospital readmission that persist for multiple years after hospitalization.”

Indeed, a 2013 report linked sepsis to significantly higher mortality risk over 5 years, after accounting for comorbidities. Postsepsis patients were 13 times more likely to die over the first year after hospitalization than counterparts who didn’t have sepsis (BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004283).

For the new study, Dr. Taylor said, “we aimed to evaluate current care practices with the hope to identify a postsepsis management strategy that could help nudge these patients towards a more meaningful recovery.”

The researchers retrospectively tracked a random sample of 100 patients (median age, 63 years), who were discharged following an admission for sepsis in 2017. They were treated at eight acute care hospitals in western and central North Carolina and hospitalized for a median of 5 days; 75 were discharged to home (17 received home health services there), 17 went to skilled nursing or long-term care facilities, and 8 went to hospice or another location.

The researchers analyzed whether the patients received four kinds of postsepsis care within 90 days, as recommended by a 2018 review: screening for common functional impairments (53/100 patients received this screening); adjustment of medications as needed following discharge (53/100 patients); monitoring for common and preventable causes for health deterioration, such as infection, chronic lung disease, or heart failure exacerbation (37/100); and assessment for palliative care (25/100 patients) (JAMA. 2018;319[1]:62-75).

Within 90 days of discharge, 34 patients were readmitted and 17 died. The 32 patients who received at least two recommended kinds of postsepsis care were less likely to be readmitted or die (9/32) than those who got zero or one recommended kind of care (34/68; odds ratio, 0.26; 95% confidence ratio, 0.09-0.82).

In an interview, study coauthor Marc Kowalkowski, PhD, associate professor with Atrium Health’s Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, said he was hesitant to only allocate blame to hospitals or outpatient providers. “Transition out of the hospital is an extremely complex event, involving often fragmented care settings, and sepsis patients tend to be more complicated than other patients. It probably makes sense to provide an added layer of support during the transition out of the hospital for patients who are at high risk for poor outcomes.”

Overall, the findings are “a call for clinicians to realize sepsis is more than just an acute illness. The combination of a growing number of sepsis survivors and the increased health problems following an episode of sepsis creates an urgent public health challenge,” Dr. Taylor said.

Is more home health an important part of a solution? It may be helpful, Dr. Taylor said, but “our data suggest that there really needs to be better coordination to bridge between the inpatient and outpatient transition. We are currently conducting a randomized study to investigate whether these types of care processes can be delivered effectively through a nurse navigator to improve patient outcomes.”

Fortunately, she said, the findings suggest “we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. We just have to work on implementation of strategies for care processes that we are already familiar with.”

No funding was reported. None of the study authors reported relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Taylor SP et al. CCC48, Abstract 1320.

SAN DIEGO – North Carolina health care workers often failed to provide best-practice follow-up to patients who were released after hospitalization for sepsis, a small study has found. There may be a cost to this gap:

“It’s disappointing to see that we are not providing these seemingly common-sense care processes to our sepsis patients at discharge,” said study lead author Stephanie Parks Taylor, MD, of Atrium Health’s Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, in an interview following the presentation of the study findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. “We need to develop and implement strategies to improve outcomes for sepsis patients, not just while they are in the hospital, but after discharge as well.”

A 2017 report estimated that 1.7 million adults were hospitalized for sepsis in the United States in 2014, and 270,000 died (JAMA. 2017;318[13]:1241-9). Age-adjusted sepsis death rates in the United States are highest in states in the Eastern and Southern regions, a 2017 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggested; North Carolina has the 32nd-worst sepsis death rate in the country (12.4 deaths per 100,000 population).

Dr. Taylor said some recent news about sepsis is promising. “We’ve seen decreasing mortality rates from initiatives that improve the early detection of sepsis and rapid delivery of antibiotics, fluids, and other treatment. However, there is growing evidence that patients who survive an episode of sepsis face residual health deficits. Many sepsis survivors are left with new functional, cognitive, or mental health declines or worsening of their underlying comorbidities. Unfortunately, these patients have high rates of mortality and hospital readmission that persist for multiple years after hospitalization.”

Indeed, a 2013 report linked sepsis to significantly higher mortality risk over 5 years, after accounting for comorbidities. Postsepsis patients were 13 times more likely to die over the first year after hospitalization than counterparts who didn’t have sepsis (BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004283).

For the new study, Dr. Taylor said, “we aimed to evaluate current care practices with the hope to identify a postsepsis management strategy that could help nudge these patients towards a more meaningful recovery.”

The researchers retrospectively tracked a random sample of 100 patients (median age, 63 years), who were discharged following an admission for sepsis in 2017. They were treated at eight acute care hospitals in western and central North Carolina and hospitalized for a median of 5 days; 75 were discharged to home (17 received home health services there), 17 went to skilled nursing or long-term care facilities, and 8 went to hospice or another location.

The researchers analyzed whether the patients received four kinds of postsepsis care within 90 days, as recommended by a 2018 review: screening for common functional impairments (53/100 patients received this screening); adjustment of medications as needed following discharge (53/100 patients); monitoring for common and preventable causes for health deterioration, such as infection, chronic lung disease, or heart failure exacerbation (37/100); and assessment for palliative care (25/100 patients) (JAMA. 2018;319[1]:62-75).

Within 90 days of discharge, 34 patients were readmitted and 17 died. The 32 patients who received at least two recommended kinds of postsepsis care were less likely to be readmitted or die (9/32) than those who got zero or one recommended kind of care (34/68; odds ratio, 0.26; 95% confidence ratio, 0.09-0.82).

In an interview, study coauthor Marc Kowalkowski, PhD, associate professor with Atrium Health’s Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, said he was hesitant to only allocate blame to hospitals or outpatient providers. “Transition out of the hospital is an extremely complex event, involving often fragmented care settings, and sepsis patients tend to be more complicated than other patients. It probably makes sense to provide an added layer of support during the transition out of the hospital for patients who are at high risk for poor outcomes.”

Overall, the findings are “a call for clinicians to realize sepsis is more than just an acute illness. The combination of a growing number of sepsis survivors and the increased health problems following an episode of sepsis creates an urgent public health challenge,” Dr. Taylor said.

Is more home health an important part of a solution? It may be helpful, Dr. Taylor said, but “our data suggest that there really needs to be better coordination to bridge between the inpatient and outpatient transition. We are currently conducting a randomized study to investigate whether these types of care processes can be delivered effectively through a nurse navigator to improve patient outcomes.”

Fortunately, she said, the findings suggest “we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. We just have to work on implementation of strategies for care processes that we are already familiar with.”

No funding was reported. None of the study authors reported relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Taylor SP et al. CCC48, Abstract 1320.

SAN DIEGO – North Carolina health care workers often failed to provide best-practice follow-up to patients who were released after hospitalization for sepsis, a small study has found. There may be a cost to this gap:

“It’s disappointing to see that we are not providing these seemingly common-sense care processes to our sepsis patients at discharge,” said study lead author Stephanie Parks Taylor, MD, of Atrium Health’s Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, in an interview following the presentation of the study findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. “We need to develop and implement strategies to improve outcomes for sepsis patients, not just while they are in the hospital, but after discharge as well.”