User login

New Topical Treatments for Psoriasis

The size of the baby boomers’ hepatitis C problem

Baby boomers account for more than 74% of chronic hepatitis C virus cases. Noncardiac surgery has a 7% covert stroke rate in the elderly. Enterovirus in at-risk children is associated with later celiac disease. And why you shouldn’t fear spironolactone, isotretinoin, or oral contraceptives for acne.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Baby boomers account for more than 74% of chronic hepatitis C virus cases. Noncardiac surgery has a 7% covert stroke rate in the elderly. Enterovirus in at-risk children is associated with later celiac disease. And why you shouldn’t fear spironolactone, isotretinoin, or oral contraceptives for acne.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Baby boomers account for more than 74% of chronic hepatitis C virus cases. Noncardiac surgery has a 7% covert stroke rate in the elderly. Enterovirus in at-risk children is associated with later celiac disease. And why you shouldn’t fear spironolactone, isotretinoin, or oral contraceptives for acne.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

How to review scientific literature

And Ilana Yurkiewicz, MD, talks about chaos and opportunity. Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University and is also a columnist for Hematology News. More from Dr. Yurkiewicz here.

Subscribe to Blood & Cancer here:

Show notes

By Hitomi Hosoya, MD, PhD,

Resident in the department of internal medicine, University of Pennsylvania Health System

- If you are a peer reviewer of a manuscript submitted to a journal, you should be unbiased, consistent, constructive, and focused on the research. COPE guideline is a good resource.

- If you are a reader of a published article, it is important to ensure that the abstract has the same conclusion as the body of the article.

- If you are a clinical practitioner and wondering how to apply findings of published data, the editorial section is a good source.

- If you are a trainee and wondering how to stay up-to-date, Oxford Textbook of Oncology or ASCO University are recommended.

Reference:

https://publicationethics.org/resources/guidelines-new/cope-ethical-guidelines-peer-reviewers

And Ilana Yurkiewicz, MD, talks about chaos and opportunity. Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University and is also a columnist for Hematology News. More from Dr. Yurkiewicz here.

Subscribe to Blood & Cancer here:

Show notes

By Hitomi Hosoya, MD, PhD,

Resident in the department of internal medicine, University of Pennsylvania Health System

- If you are a peer reviewer of a manuscript submitted to a journal, you should be unbiased, consistent, constructive, and focused on the research. COPE guideline is a good resource.

- If you are a reader of a published article, it is important to ensure that the abstract has the same conclusion as the body of the article.

- If you are a clinical practitioner and wondering how to apply findings of published data, the editorial section is a good source.

- If you are a trainee and wondering how to stay up-to-date, Oxford Textbook of Oncology or ASCO University are recommended.

Reference:

https://publicationethics.org/resources/guidelines-new/cope-ethical-guidelines-peer-reviewers

And Ilana Yurkiewicz, MD, talks about chaos and opportunity. Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University and is also a columnist for Hematology News. More from Dr. Yurkiewicz here.

Subscribe to Blood & Cancer here:

Show notes

By Hitomi Hosoya, MD, PhD,

Resident in the department of internal medicine, University of Pennsylvania Health System

- If you are a peer reviewer of a manuscript submitted to a journal, you should be unbiased, consistent, constructive, and focused on the research. COPE guideline is a good resource.

- If you are a reader of a published article, it is important to ensure that the abstract has the same conclusion as the body of the article.

- If you are a clinical practitioner and wondering how to apply findings of published data, the editorial section is a good source.

- If you are a trainee and wondering how to stay up-to-date, Oxford Textbook of Oncology or ASCO University are recommended.

Reference:

https://publicationethics.org/resources/guidelines-new/cope-ethical-guidelines-peer-reviewers

Brain Biomarkers May Help Explain Severe PTSD Symptoms

A current theory holds that during a traumatic event, a person may learn to associate the people, locations, and objects in the situation with the trauma, and long after the event even the “safe” stimuli can trigger fearful and defensive responses. Experts believe it is an “overlearned response” to a threatening experience. But the way in which that learning happens is not well understood, say researchers from Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. Their study, though, may shed new light on how people with PTSD symptoms learn and unlearn fear.

In the study, funded in part by the National Institute of Mental Health, the researchers examined how the mental adjustments performed during learning and the way the brain tracks these adjustments relate to symptom severity.

They gave combat veterans with varying levels of PTSD symptom severity a reversal learning task. Participants were shown 2 mildly angry human faces and mildly shocked after viewing 1 face, but not the other. Then the task was reversed, with the aim of having the participants “unlearn” their original fear conditioning and testing their ability to relearn how to respond to negative surprises in the environment.

Although all participants were able to perform the reversal learning, the researchers found “pronounced differences in the ‘learning rates.’” Highly symptomatic veterans tended to overreact when what they expected to happen and what actually happened did not match up.

The researchers say they found biomarkers that could explain the different reactions. In the highly symptomatic veterans, 2 areas of the brain—the amygdala and striatum—were less able to track changes in threat level.

“One’s inability to adequately adjust expectations for potentially aversive outcomes has potential clinical relevance,” said Ilan Harpaz-Rotem, PhD, co-leader of the study, “as this deficit may lead to avoidance and depressive behavior.”

The researchers say their findings could give a “more fine-grained understanding of how learning processes may go awry in the aftermath of combat trauma.”

A current theory holds that during a traumatic event, a person may learn to associate the people, locations, and objects in the situation with the trauma, and long after the event even the “safe” stimuli can trigger fearful and defensive responses. Experts believe it is an “overlearned response” to a threatening experience. But the way in which that learning happens is not well understood, say researchers from Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. Their study, though, may shed new light on how people with PTSD symptoms learn and unlearn fear.

In the study, funded in part by the National Institute of Mental Health, the researchers examined how the mental adjustments performed during learning and the way the brain tracks these adjustments relate to symptom severity.

They gave combat veterans with varying levels of PTSD symptom severity a reversal learning task. Participants were shown 2 mildly angry human faces and mildly shocked after viewing 1 face, but not the other. Then the task was reversed, with the aim of having the participants “unlearn” their original fear conditioning and testing their ability to relearn how to respond to negative surprises in the environment.

Although all participants were able to perform the reversal learning, the researchers found “pronounced differences in the ‘learning rates.’” Highly symptomatic veterans tended to overreact when what they expected to happen and what actually happened did not match up.

The researchers say they found biomarkers that could explain the different reactions. In the highly symptomatic veterans, 2 areas of the brain—the amygdala and striatum—were less able to track changes in threat level.

“One’s inability to adequately adjust expectations for potentially aversive outcomes has potential clinical relevance,” said Ilan Harpaz-Rotem, PhD, co-leader of the study, “as this deficit may lead to avoidance and depressive behavior.”

The researchers say their findings could give a “more fine-grained understanding of how learning processes may go awry in the aftermath of combat trauma.”

A current theory holds that during a traumatic event, a person may learn to associate the people, locations, and objects in the situation with the trauma, and long after the event even the “safe” stimuli can trigger fearful and defensive responses. Experts believe it is an “overlearned response” to a threatening experience. But the way in which that learning happens is not well understood, say researchers from Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. Their study, though, may shed new light on how people with PTSD symptoms learn and unlearn fear.

In the study, funded in part by the National Institute of Mental Health, the researchers examined how the mental adjustments performed during learning and the way the brain tracks these adjustments relate to symptom severity.

They gave combat veterans with varying levels of PTSD symptom severity a reversal learning task. Participants were shown 2 mildly angry human faces and mildly shocked after viewing 1 face, but not the other. Then the task was reversed, with the aim of having the participants “unlearn” their original fear conditioning and testing their ability to relearn how to respond to negative surprises in the environment.

Although all participants were able to perform the reversal learning, the researchers found “pronounced differences in the ‘learning rates.’” Highly symptomatic veterans tended to overreact when what they expected to happen and what actually happened did not match up.

The researchers say they found biomarkers that could explain the different reactions. In the highly symptomatic veterans, 2 areas of the brain—the amygdala and striatum—were less able to track changes in threat level.

“One’s inability to adequately adjust expectations for potentially aversive outcomes has potential clinical relevance,” said Ilan Harpaz-Rotem, PhD, co-leader of the study, “as this deficit may lead to avoidance and depressive behavior.”

The researchers say their findings could give a “more fine-grained understanding of how learning processes may go awry in the aftermath of combat trauma.”

Working With Parents to Vaccinate Children

Global outbreaks of infectious diseases—such as smallpox, pertussis, dysentery, and scarlet fever—seem like fodder for the history books. It was centuries ago that epidemics wiped out large swathes of the world population. Many people living and raising children today have never witnessed the devastating effects of measles, mumps, polio, and influenza—diseases that have been substantially reduced or even eradicated.1 Why? Because since the early 1900s, we have had scientifically developed and widely distributed vaccines at our disposal.

In context, it is incredible to realize that we are still in the beginning stages of vaccine research and development. From that perspective, it is perhaps not as surprising that some parents are hesitant to vaccinate their children—after all, do we really know everything we can and should know about inoculation? Parental resistance to or refusal of vaccination is further fueled by tainted research (Andrew Wakefield was forced to retract his findings that “validated” a link between thimerosal in vaccines and autism) and misinformation propagated on the Internet.2

But what has long been a source of frustration to those who support routine vaccination has, in recent years, started to become a public health issue. Measles outbreaks are no longer historical artifacts—they are real, as evidenced by the current rise in cases centered in Clark County, Washington. Through the first full week of February 2019, there were 101 confirmed cases of measles in the US, half of which occurred in Washington State—leading the governor to declare a public health emergency.3

This has, of course, reinvigorated the ongoing discussion about parental refusal to vaccinate. Enough has been said on this topic, by both public officials and private individuals, in a variety of venues over the years. So I’d like to focus instead on the role that individual health care providers can play in this situation.

Over the years, many of my colleagues have shared stories about parents who have refused to vaccinate their children. We know many things: These parents often fear complications from vaccination more than complications of disease. Many have religious or philosophical reasons for their reluctance or refusal to vaccinate their children. Some have concerns about vaccine safety or effectiveness. We know these things … but we don’t always know how to speak with parents about these issues.

It is somewhat ironic that the core motivation for hesitant parents and well-meaning clinicians is the same: care and protection of the child. The difficulty lies in the disparate view of what that entails. As NPs and PAs, though, our duty is to seek health benefits for and minimize harm to the patients in our care. Part of our role, when those patients are children, is to provide parents with the necessary risk-benefit information to help them make informed decisions. When the subject is vaccination, we must listen carefully and be respectful of parents’ concerns; we must recognize that their decision-making criteria may differ from ours.

So how can we bridge the gap with parents who “don’t see it the way we do”? We start by being honest with them about what is and isn’t known as far as the risks and benefits of vaccination in general or a vaccine in particular. This means acknowledging that although vaccines are very safe, they are not risk-free or 100% effective. But this also gives us the opportunity to provide them with validated data and to emphasize that the risks of any vaccine should not be considered in a silo but rather in comparison with the risks of the disease in question or of the lack of immunization.

Continue to: Helpfully, Leask and colleagues...

Helpfully, Leask and colleagues have classified parental positions on vaccination, which also provided the groundwork to offer strategies for communicating with each group.4 They identified five classes:

Unquestioning acceptors (30% to 40% of parents), who vaccinate their children and typically have no specific questions about the need for or safety of vaccines. Since this group tends to have a good relationship with their health care team but less detailed knowledge about vaccination, clinicians should continue to build rapport while providing scientific information about the vaccine being recommended or administered.4

Cautious acceptors (25% to 35%), who vaccinate their children despite having minor concerns. They tend to recognize the risk for adverse effects and hope their child will not be affected. In addition to building rapport, clinicians should provide verbal and numeric descriptions of relevant vaccine data and explain common adverse effects and disease risks.4

Hesitant vaccinators (20% to 30%), who are on the fence about the benefits and safety of vaccination. Their focus is more on the negative aspects, and they may not feel particularly trusting of their health care provider. Therefore, gaining trust is vital—parents in this group are eager to discuss their concerns with their clinician and have their questions answered satisfactorily. Motivational interviewing using a guiding style may be a helpful tool.4

Late or selective vaccinators (2% to 27%), who have significant doubts about the safety and necessity of vaccines, resulting in their choice to delay vaccination or select only some of the recommended vaccines for their child. These parents may require additional time—possibly a second appointment—in which to fully discuss their concerns. Be sure to provide up-to-date information on the risks and benefits of a vaccine, and use decision aids as appropriate.4

Continue to: Refusers...

Refusers (<2%), who have concerns about the number of vaccines children receive and conflicting feelings about whom to trust and how best to get answers to their questions. This group tends to demonstrate high knowledge levels about vaccination but may be the most argumentative when presented with information. Emphasize the importance of protecting the child from an infectious disease and reinforce the effectiveness of the vaccine. Use statistics rather than anecdotes. But above all, spend the time needed to provide refusers with a thorough understanding of the risks of not immunizing their child.4

Although it is not a universal sentiment, many parents confer trust on their health care providers. We can use this trust in a respectful, noncoercive, and non-condescending manner by providing research-supported facts about vaccines. Clinicians who listen with a compassionate ear will be in the best position to lead the hesitant, late or selective, or refusing parents to confidently make an informed decision that immunization is the best way to protect their children from vaccine-preventable diseases.4

Rather than yet again focusing on the negative, I’d like to ask: Have you had a success story of helping parents to choose vaccination for their children? How did you overcome their concerns? Share your experience with me at PAeditor@mdege.com.

1. CDC. Achievements in public health, 1900-1999 impact of vaccines universally recommended for children—United States, 1990-1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(12):243-248.

2. Wakefield AJ, Murch SH, Anthony A, et al. RETRACTED: Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet. 1998;351(9103):637-641.

3. Franki R. United States now over 100 measles cases for the year. MDEdge Family Practice. February 11, 2019.

4. Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, et al. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatrics. 2012;12:154.

Global outbreaks of infectious diseases—such as smallpox, pertussis, dysentery, and scarlet fever—seem like fodder for the history books. It was centuries ago that epidemics wiped out large swathes of the world population. Many people living and raising children today have never witnessed the devastating effects of measles, mumps, polio, and influenza—diseases that have been substantially reduced or even eradicated.1 Why? Because since the early 1900s, we have had scientifically developed and widely distributed vaccines at our disposal.

In context, it is incredible to realize that we are still in the beginning stages of vaccine research and development. From that perspective, it is perhaps not as surprising that some parents are hesitant to vaccinate their children—after all, do we really know everything we can and should know about inoculation? Parental resistance to or refusal of vaccination is further fueled by tainted research (Andrew Wakefield was forced to retract his findings that “validated” a link between thimerosal in vaccines and autism) and misinformation propagated on the Internet.2

But what has long been a source of frustration to those who support routine vaccination has, in recent years, started to become a public health issue. Measles outbreaks are no longer historical artifacts—they are real, as evidenced by the current rise in cases centered in Clark County, Washington. Through the first full week of February 2019, there were 101 confirmed cases of measles in the US, half of which occurred in Washington State—leading the governor to declare a public health emergency.3

This has, of course, reinvigorated the ongoing discussion about parental refusal to vaccinate. Enough has been said on this topic, by both public officials and private individuals, in a variety of venues over the years. So I’d like to focus instead on the role that individual health care providers can play in this situation.

Over the years, many of my colleagues have shared stories about parents who have refused to vaccinate their children. We know many things: These parents often fear complications from vaccination more than complications of disease. Many have religious or philosophical reasons for their reluctance or refusal to vaccinate their children. Some have concerns about vaccine safety or effectiveness. We know these things … but we don’t always know how to speak with parents about these issues.

It is somewhat ironic that the core motivation for hesitant parents and well-meaning clinicians is the same: care and protection of the child. The difficulty lies in the disparate view of what that entails. As NPs and PAs, though, our duty is to seek health benefits for and minimize harm to the patients in our care. Part of our role, when those patients are children, is to provide parents with the necessary risk-benefit information to help them make informed decisions. When the subject is vaccination, we must listen carefully and be respectful of parents’ concerns; we must recognize that their decision-making criteria may differ from ours.

So how can we bridge the gap with parents who “don’t see it the way we do”? We start by being honest with them about what is and isn’t known as far as the risks and benefits of vaccination in general or a vaccine in particular. This means acknowledging that although vaccines are very safe, they are not risk-free or 100% effective. But this also gives us the opportunity to provide them with validated data and to emphasize that the risks of any vaccine should not be considered in a silo but rather in comparison with the risks of the disease in question or of the lack of immunization.

Continue to: Helpfully, Leask and colleagues...

Helpfully, Leask and colleagues have classified parental positions on vaccination, which also provided the groundwork to offer strategies for communicating with each group.4 They identified five classes:

Unquestioning acceptors (30% to 40% of parents), who vaccinate their children and typically have no specific questions about the need for or safety of vaccines. Since this group tends to have a good relationship with their health care team but less detailed knowledge about vaccination, clinicians should continue to build rapport while providing scientific information about the vaccine being recommended or administered.4

Cautious acceptors (25% to 35%), who vaccinate their children despite having minor concerns. They tend to recognize the risk for adverse effects and hope their child will not be affected. In addition to building rapport, clinicians should provide verbal and numeric descriptions of relevant vaccine data and explain common adverse effects and disease risks.4

Hesitant vaccinators (20% to 30%), who are on the fence about the benefits and safety of vaccination. Their focus is more on the negative aspects, and they may not feel particularly trusting of their health care provider. Therefore, gaining trust is vital—parents in this group are eager to discuss their concerns with their clinician and have their questions answered satisfactorily. Motivational interviewing using a guiding style may be a helpful tool.4

Late or selective vaccinators (2% to 27%), who have significant doubts about the safety and necessity of vaccines, resulting in their choice to delay vaccination or select only some of the recommended vaccines for their child. These parents may require additional time—possibly a second appointment—in which to fully discuss their concerns. Be sure to provide up-to-date information on the risks and benefits of a vaccine, and use decision aids as appropriate.4

Continue to: Refusers...

Refusers (<2%), who have concerns about the number of vaccines children receive and conflicting feelings about whom to trust and how best to get answers to their questions. This group tends to demonstrate high knowledge levels about vaccination but may be the most argumentative when presented with information. Emphasize the importance of protecting the child from an infectious disease and reinforce the effectiveness of the vaccine. Use statistics rather than anecdotes. But above all, spend the time needed to provide refusers with a thorough understanding of the risks of not immunizing their child.4

Although it is not a universal sentiment, many parents confer trust on their health care providers. We can use this trust in a respectful, noncoercive, and non-condescending manner by providing research-supported facts about vaccines. Clinicians who listen with a compassionate ear will be in the best position to lead the hesitant, late or selective, or refusing parents to confidently make an informed decision that immunization is the best way to protect their children from vaccine-preventable diseases.4

Rather than yet again focusing on the negative, I’d like to ask: Have you had a success story of helping parents to choose vaccination for their children? How did you overcome their concerns? Share your experience with me at PAeditor@mdege.com.

Global outbreaks of infectious diseases—such as smallpox, pertussis, dysentery, and scarlet fever—seem like fodder for the history books. It was centuries ago that epidemics wiped out large swathes of the world population. Many people living and raising children today have never witnessed the devastating effects of measles, mumps, polio, and influenza—diseases that have been substantially reduced or even eradicated.1 Why? Because since the early 1900s, we have had scientifically developed and widely distributed vaccines at our disposal.

In context, it is incredible to realize that we are still in the beginning stages of vaccine research and development. From that perspective, it is perhaps not as surprising that some parents are hesitant to vaccinate their children—after all, do we really know everything we can and should know about inoculation? Parental resistance to or refusal of vaccination is further fueled by tainted research (Andrew Wakefield was forced to retract his findings that “validated” a link between thimerosal in vaccines and autism) and misinformation propagated on the Internet.2

But what has long been a source of frustration to those who support routine vaccination has, in recent years, started to become a public health issue. Measles outbreaks are no longer historical artifacts—they are real, as evidenced by the current rise in cases centered in Clark County, Washington. Through the first full week of February 2019, there were 101 confirmed cases of measles in the US, half of which occurred in Washington State—leading the governor to declare a public health emergency.3

This has, of course, reinvigorated the ongoing discussion about parental refusal to vaccinate. Enough has been said on this topic, by both public officials and private individuals, in a variety of venues over the years. So I’d like to focus instead on the role that individual health care providers can play in this situation.

Over the years, many of my colleagues have shared stories about parents who have refused to vaccinate their children. We know many things: These parents often fear complications from vaccination more than complications of disease. Many have religious or philosophical reasons for their reluctance or refusal to vaccinate their children. Some have concerns about vaccine safety or effectiveness. We know these things … but we don’t always know how to speak with parents about these issues.

It is somewhat ironic that the core motivation for hesitant parents and well-meaning clinicians is the same: care and protection of the child. The difficulty lies in the disparate view of what that entails. As NPs and PAs, though, our duty is to seek health benefits for and minimize harm to the patients in our care. Part of our role, when those patients are children, is to provide parents with the necessary risk-benefit information to help them make informed decisions. When the subject is vaccination, we must listen carefully and be respectful of parents’ concerns; we must recognize that their decision-making criteria may differ from ours.

So how can we bridge the gap with parents who “don’t see it the way we do”? We start by being honest with them about what is and isn’t known as far as the risks and benefits of vaccination in general or a vaccine in particular. This means acknowledging that although vaccines are very safe, they are not risk-free or 100% effective. But this also gives us the opportunity to provide them with validated data and to emphasize that the risks of any vaccine should not be considered in a silo but rather in comparison with the risks of the disease in question or of the lack of immunization.

Continue to: Helpfully, Leask and colleagues...

Helpfully, Leask and colleagues have classified parental positions on vaccination, which also provided the groundwork to offer strategies for communicating with each group.4 They identified five classes:

Unquestioning acceptors (30% to 40% of parents), who vaccinate their children and typically have no specific questions about the need for or safety of vaccines. Since this group tends to have a good relationship with their health care team but less detailed knowledge about vaccination, clinicians should continue to build rapport while providing scientific information about the vaccine being recommended or administered.4

Cautious acceptors (25% to 35%), who vaccinate their children despite having minor concerns. They tend to recognize the risk for adverse effects and hope their child will not be affected. In addition to building rapport, clinicians should provide verbal and numeric descriptions of relevant vaccine data and explain common adverse effects and disease risks.4

Hesitant vaccinators (20% to 30%), who are on the fence about the benefits and safety of vaccination. Their focus is more on the negative aspects, and they may not feel particularly trusting of their health care provider. Therefore, gaining trust is vital—parents in this group are eager to discuss their concerns with their clinician and have their questions answered satisfactorily. Motivational interviewing using a guiding style may be a helpful tool.4

Late or selective vaccinators (2% to 27%), who have significant doubts about the safety and necessity of vaccines, resulting in their choice to delay vaccination or select only some of the recommended vaccines for their child. These parents may require additional time—possibly a second appointment—in which to fully discuss their concerns. Be sure to provide up-to-date information on the risks and benefits of a vaccine, and use decision aids as appropriate.4

Continue to: Refusers...

Refusers (<2%), who have concerns about the number of vaccines children receive and conflicting feelings about whom to trust and how best to get answers to their questions. This group tends to demonstrate high knowledge levels about vaccination but may be the most argumentative when presented with information. Emphasize the importance of protecting the child from an infectious disease and reinforce the effectiveness of the vaccine. Use statistics rather than anecdotes. But above all, spend the time needed to provide refusers with a thorough understanding of the risks of not immunizing their child.4

Although it is not a universal sentiment, many parents confer trust on their health care providers. We can use this trust in a respectful, noncoercive, and non-condescending manner by providing research-supported facts about vaccines. Clinicians who listen with a compassionate ear will be in the best position to lead the hesitant, late or selective, or refusing parents to confidently make an informed decision that immunization is the best way to protect their children from vaccine-preventable diseases.4

Rather than yet again focusing on the negative, I’d like to ask: Have you had a success story of helping parents to choose vaccination for their children? How did you overcome their concerns? Share your experience with me at PAeditor@mdege.com.

1. CDC. Achievements in public health, 1900-1999 impact of vaccines universally recommended for children—United States, 1990-1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(12):243-248.

2. Wakefield AJ, Murch SH, Anthony A, et al. RETRACTED: Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet. 1998;351(9103):637-641.

3. Franki R. United States now over 100 measles cases for the year. MDEdge Family Practice. February 11, 2019.

4. Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, et al. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatrics. 2012;12:154.

1. CDC. Achievements in public health, 1900-1999 impact of vaccines universally recommended for children—United States, 1990-1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(12):243-248.

2. Wakefield AJ, Murch SH, Anthony A, et al. RETRACTED: Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet. 1998;351(9103):637-641.

3. Franki R. United States now over 100 measles cases for the year. MDEdge Family Practice. February 11, 2019.

4. Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, et al. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatrics. 2012;12:154.

Trametinib effectively treats case of giant congenital melanocytic nevus

according to a case report presented in Pediatrics.

Her nevus covered most of her back and much of her torso and had thickened significantly over the years since initial presentation to the point of disfigurement, even invading the fascia and musculature of the trunk and pelvis, reported Adnan Mir, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his coauthors. Furthermore, she presented with intractable pruritus and pain that interfered with sleep and responded minimally to treatments. Although initial immunohistochemical staining and gene sequencing did not reveal any mutations, such as BRAF V600E, further testing uncovered an AKAP9-BRAF fusion.

There are few if any effective ways of treating GCMNs. With that knowledge, as well as general theories of the mechanism GCMNs in mind, the patient’s health care team decided to try a 0.5-mg daily dose of trametinib when she was 7 years old. Her pruritus and pain resolved completely, and after 6 months of treatment with trametinib, repeat MRI “revealed decreased thickening of the dermis and near resolutions of muscular invasion.” According to the patient’s family, her quality of life improved dramatically.

SOURCE: Mir A et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20182469.

according to a case report presented in Pediatrics.

Her nevus covered most of her back and much of her torso and had thickened significantly over the years since initial presentation to the point of disfigurement, even invading the fascia and musculature of the trunk and pelvis, reported Adnan Mir, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his coauthors. Furthermore, she presented with intractable pruritus and pain that interfered with sleep and responded minimally to treatments. Although initial immunohistochemical staining and gene sequencing did not reveal any mutations, such as BRAF V600E, further testing uncovered an AKAP9-BRAF fusion.

There are few if any effective ways of treating GCMNs. With that knowledge, as well as general theories of the mechanism GCMNs in mind, the patient’s health care team decided to try a 0.5-mg daily dose of trametinib when she was 7 years old. Her pruritus and pain resolved completely, and after 6 months of treatment with trametinib, repeat MRI “revealed decreased thickening of the dermis and near resolutions of muscular invasion.” According to the patient’s family, her quality of life improved dramatically.

SOURCE: Mir A et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20182469.

according to a case report presented in Pediatrics.

Her nevus covered most of her back and much of her torso and had thickened significantly over the years since initial presentation to the point of disfigurement, even invading the fascia and musculature of the trunk and pelvis, reported Adnan Mir, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his coauthors. Furthermore, she presented with intractable pruritus and pain that interfered with sleep and responded minimally to treatments. Although initial immunohistochemical staining and gene sequencing did not reveal any mutations, such as BRAF V600E, further testing uncovered an AKAP9-BRAF fusion.

There are few if any effective ways of treating GCMNs. With that knowledge, as well as general theories of the mechanism GCMNs in mind, the patient’s health care team decided to try a 0.5-mg daily dose of trametinib when she was 7 years old. Her pruritus and pain resolved completely, and after 6 months of treatment with trametinib, repeat MRI “revealed decreased thickening of the dermis and near resolutions of muscular invasion.” According to the patient’s family, her quality of life improved dramatically.

SOURCE: Mir A et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20182469.

FROM PEDIATRICS

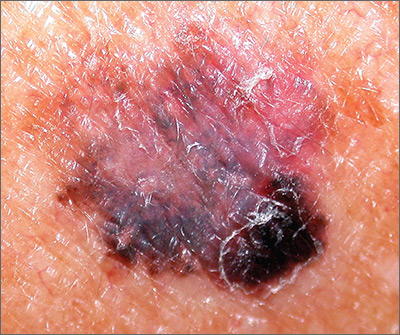

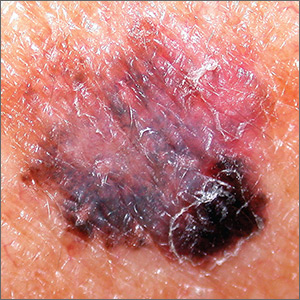

Dark spot on arm

The FP suspected that this was a melanoma or a pigmented basal cell carcinoma.

Going through the ABCDE criteria, the FP noted that the spot was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was >6 mm, and the history was positive for an Enlarging lesion. With 5 out of the 5 criteria positive, it was likely that this was a melanoma. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy (saucerization) with 1- to 2-mm margins to provide full sampling for the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The depth of the tissue biopsy was approximately 1 to 1.5 mm (a dime is 1.4 mm in depth), which was adequate for a lesion of this type. The pathology report came back as invasive melanoma with a 0.25 mm Breslow depth.

The FP referred the patient to a local dermatologist, who agreed to see the patient within the next 2 weeks rather than the standard 3- to 4-month wait time for a new patient. The dermatologist performed a wide local excision with a 1-cm margin down to the fascia. While this melanoma was invasive, this depth did not require sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging. On a follow-up visit, the FP counseled the patient about sun protection and the need for regular skin exams. Note that while brown skin and regular sun exposure may be less risky for melanoma than fair skin with multiple sunburns, anyone can get a melanoma.

Photo courtesy of Eric Kraus, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this was a melanoma or a pigmented basal cell carcinoma.

Going through the ABCDE criteria, the FP noted that the spot was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was >6 mm, and the history was positive for an Enlarging lesion. With 5 out of the 5 criteria positive, it was likely that this was a melanoma. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy (saucerization) with 1- to 2-mm margins to provide full sampling for the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The depth of the tissue biopsy was approximately 1 to 1.5 mm (a dime is 1.4 mm in depth), which was adequate for a lesion of this type. The pathology report came back as invasive melanoma with a 0.25 mm Breslow depth.

The FP referred the patient to a local dermatologist, who agreed to see the patient within the next 2 weeks rather than the standard 3- to 4-month wait time for a new patient. The dermatologist performed a wide local excision with a 1-cm margin down to the fascia. While this melanoma was invasive, this depth did not require sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging. On a follow-up visit, the FP counseled the patient about sun protection and the need for regular skin exams. Note that while brown skin and regular sun exposure may be less risky for melanoma than fair skin with multiple sunburns, anyone can get a melanoma.

Photo courtesy of Eric Kraus, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this was a melanoma or a pigmented basal cell carcinoma.

Going through the ABCDE criteria, the FP noted that the spot was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was >6 mm, and the history was positive for an Enlarging lesion. With 5 out of the 5 criteria positive, it was likely that this was a melanoma. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy (saucerization) with 1- to 2-mm margins to provide full sampling for the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The depth of the tissue biopsy was approximately 1 to 1.5 mm (a dime is 1.4 mm in depth), which was adequate for a lesion of this type. The pathology report came back as invasive melanoma with a 0.25 mm Breslow depth.

The FP referred the patient to a local dermatologist, who agreed to see the patient within the next 2 weeks rather than the standard 3- to 4-month wait time for a new patient. The dermatologist performed a wide local excision with a 1-cm margin down to the fascia. While this melanoma was invasive, this depth did not require sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging. On a follow-up visit, the FP counseled the patient about sun protection and the need for regular skin exams. Note that while brown skin and regular sun exposure may be less risky for melanoma than fair skin with multiple sunburns, anyone can get a melanoma.

Photo courtesy of Eric Kraus, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Health spending: Boomers will spike costs, but growing uninsured will soften their impact

Spending on health care is projected to rise at a faster-than-average rate throughout the next decade, according to the Office of the Actuary at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

“Overall, national health spending is projected to grow at 5.5% per year, on average, for 2018-27,” wrote Andrea Sisko, economist in the Office of the Actuary, and colleagues (Health Aff. 2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05499). “This is faster than the average growth rate experienced following the last recession (3.9% for 2008-2013) and the more recent period inclusive of the Affordable Care Act’s major coverage expansions (5.3% for 2014-16).”

Medicare is projected to see the fastest growth in spending at 7.4% per year “as the shift of the Baby Boom generation into the program continues to result in robust growth in enrollment,” according to the authors.

Private payers should see a corollary slower growth in spending (4.8% per year) over the same period, while Medicaid spending is projected at 5.5% per year.

Faster growth in Medicare spending is expected to come from higher spending on prescription drugs and hospital services, as well as higher fee-for-service payment updates.

Spending increases are projected to be mitigated somewhat by the end of the ACA penalty for not having insurance – which is projected to add 1.3 million people this year to the ranks of the uninsured, according to the report.

Half of the overall growth in health care spending is attributable to rising prices in personal health care prices, on average, Ms. Sisko and colleagues wrote. “Growth in use and intensity is expected to account for just under one-third of the average annual personal health care spending growth, with population growth and the changing age-sex mix of the population accounting for the remainder.”

For those with private insurance, out-of-pocket spending is projected to accelerate to a 3.6% growth rate in 2018 from 2.6% in 2017 “a rate that is consistent with faster income growth as well as with the higher average deductibles for employer-based private health insurance enrollees in 2018 compared to 2017,” the authors note.

“Growth in out-of-pocket spending, which is also primarily influenced by economic factors, is expected to be similar to that of private health insurance spending in 2020-27, at 5%,” they add.

Prescription drug spending also is expected to grow.

“Following growth of just 0.4% in 2017, prescription drug spending is expected to have grown 3.3% in 2018 but still be among the slowest-growing health care sectors,” according to the authors. “Higher utilization growth is anticipated, compared to the relatively low growth in 2016 and 2017, partially driven by an increase in the number of new drug introductions.”

Growth in prescription drug spending is expected to accelerate further to 4.6% in 2019, based on growth in utilization and a “modest increase in drug price growth.”

Starting in 2020, that growth rate is projected to increase, on average, by 6.1% per year, based on the expectation that employers and insurers will lower barriers to maintenance medications for chronic conditions.

In 2019, growth in spending for physician clinical services is projected to accelerate to 5.4% from 4.9% in 2018.

“An acceleration in Medicaid spending growth is the primary factor contributing to the trend, which is in part associated with program’s expansion by additional states,” the authors note.

From 2020 to 2027, growth in spending on physician and clinical services is expected to average 5.4% per year, driven in part by price growth for these services.

“Underlying this acceleration are projected rising costs related to the provision of care,” the report said. “In particular, wages are expected to increase as a result of the supply of physicians not being able to meet expected increases in demand for care connected with the aging population. Furthermore, some of the productivity gains that have been achieved through the use of lower-cost providers as a substitute for physician care within physician practices may be less pronounced in the future, because of limitations such as licensing restrictions on the scope of care that may be provided by nonphysician providers.”

SOURCE: Sisko A et al. Health Aff. 2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05499.

Spending on health care is projected to rise at a faster-than-average rate throughout the next decade, according to the Office of the Actuary at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

“Overall, national health spending is projected to grow at 5.5% per year, on average, for 2018-27,” wrote Andrea Sisko, economist in the Office of the Actuary, and colleagues (Health Aff. 2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05499). “This is faster than the average growth rate experienced following the last recession (3.9% for 2008-2013) and the more recent period inclusive of the Affordable Care Act’s major coverage expansions (5.3% for 2014-16).”

Medicare is projected to see the fastest growth in spending at 7.4% per year “as the shift of the Baby Boom generation into the program continues to result in robust growth in enrollment,” according to the authors.

Private payers should see a corollary slower growth in spending (4.8% per year) over the same period, while Medicaid spending is projected at 5.5% per year.

Faster growth in Medicare spending is expected to come from higher spending on prescription drugs and hospital services, as well as higher fee-for-service payment updates.

Spending increases are projected to be mitigated somewhat by the end of the ACA penalty for not having insurance – which is projected to add 1.3 million people this year to the ranks of the uninsured, according to the report.

Half of the overall growth in health care spending is attributable to rising prices in personal health care prices, on average, Ms. Sisko and colleagues wrote. “Growth in use and intensity is expected to account for just under one-third of the average annual personal health care spending growth, with population growth and the changing age-sex mix of the population accounting for the remainder.”

For those with private insurance, out-of-pocket spending is projected to accelerate to a 3.6% growth rate in 2018 from 2.6% in 2017 “a rate that is consistent with faster income growth as well as with the higher average deductibles for employer-based private health insurance enrollees in 2018 compared to 2017,” the authors note.

“Growth in out-of-pocket spending, which is also primarily influenced by economic factors, is expected to be similar to that of private health insurance spending in 2020-27, at 5%,” they add.

Prescription drug spending also is expected to grow.

“Following growth of just 0.4% in 2017, prescription drug spending is expected to have grown 3.3% in 2018 but still be among the slowest-growing health care sectors,” according to the authors. “Higher utilization growth is anticipated, compared to the relatively low growth in 2016 and 2017, partially driven by an increase in the number of new drug introductions.”

Growth in prescription drug spending is expected to accelerate further to 4.6% in 2019, based on growth in utilization and a “modest increase in drug price growth.”

Starting in 2020, that growth rate is projected to increase, on average, by 6.1% per year, based on the expectation that employers and insurers will lower barriers to maintenance medications for chronic conditions.

In 2019, growth in spending for physician clinical services is projected to accelerate to 5.4% from 4.9% in 2018.

“An acceleration in Medicaid spending growth is the primary factor contributing to the trend, which is in part associated with program’s expansion by additional states,” the authors note.

From 2020 to 2027, growth in spending on physician and clinical services is expected to average 5.4% per year, driven in part by price growth for these services.

“Underlying this acceleration are projected rising costs related to the provision of care,” the report said. “In particular, wages are expected to increase as a result of the supply of physicians not being able to meet expected increases in demand for care connected with the aging population. Furthermore, some of the productivity gains that have been achieved through the use of lower-cost providers as a substitute for physician care within physician practices may be less pronounced in the future, because of limitations such as licensing restrictions on the scope of care that may be provided by nonphysician providers.”

SOURCE: Sisko A et al. Health Aff. 2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05499.

Spending on health care is projected to rise at a faster-than-average rate throughout the next decade, according to the Office of the Actuary at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

“Overall, national health spending is projected to grow at 5.5% per year, on average, for 2018-27,” wrote Andrea Sisko, economist in the Office of the Actuary, and colleagues (Health Aff. 2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05499). “This is faster than the average growth rate experienced following the last recession (3.9% for 2008-2013) and the more recent period inclusive of the Affordable Care Act’s major coverage expansions (5.3% for 2014-16).”

Medicare is projected to see the fastest growth in spending at 7.4% per year “as the shift of the Baby Boom generation into the program continues to result in robust growth in enrollment,” according to the authors.

Private payers should see a corollary slower growth in spending (4.8% per year) over the same period, while Medicaid spending is projected at 5.5% per year.

Faster growth in Medicare spending is expected to come from higher spending on prescription drugs and hospital services, as well as higher fee-for-service payment updates.

Spending increases are projected to be mitigated somewhat by the end of the ACA penalty for not having insurance – which is projected to add 1.3 million people this year to the ranks of the uninsured, according to the report.

Half of the overall growth in health care spending is attributable to rising prices in personal health care prices, on average, Ms. Sisko and colleagues wrote. “Growth in use and intensity is expected to account for just under one-third of the average annual personal health care spending growth, with population growth and the changing age-sex mix of the population accounting for the remainder.”

For those with private insurance, out-of-pocket spending is projected to accelerate to a 3.6% growth rate in 2018 from 2.6% in 2017 “a rate that is consistent with faster income growth as well as with the higher average deductibles for employer-based private health insurance enrollees in 2018 compared to 2017,” the authors note.

“Growth in out-of-pocket spending, which is also primarily influenced by economic factors, is expected to be similar to that of private health insurance spending in 2020-27, at 5%,” they add.

Prescription drug spending also is expected to grow.

“Following growth of just 0.4% in 2017, prescription drug spending is expected to have grown 3.3% in 2018 but still be among the slowest-growing health care sectors,” according to the authors. “Higher utilization growth is anticipated, compared to the relatively low growth in 2016 and 2017, partially driven by an increase in the number of new drug introductions.”

Growth in prescription drug spending is expected to accelerate further to 4.6% in 2019, based on growth in utilization and a “modest increase in drug price growth.”

Starting in 2020, that growth rate is projected to increase, on average, by 6.1% per year, based on the expectation that employers and insurers will lower barriers to maintenance medications for chronic conditions.

In 2019, growth in spending for physician clinical services is projected to accelerate to 5.4% from 4.9% in 2018.

“An acceleration in Medicaid spending growth is the primary factor contributing to the trend, which is in part associated with program’s expansion by additional states,” the authors note.

From 2020 to 2027, growth in spending on physician and clinical services is expected to average 5.4% per year, driven in part by price growth for these services.

“Underlying this acceleration are projected rising costs related to the provision of care,” the report said. “In particular, wages are expected to increase as a result of the supply of physicians not being able to meet expected increases in demand for care connected with the aging population. Furthermore, some of the productivity gains that have been achieved through the use of lower-cost providers as a substitute for physician care within physician practices may be less pronounced in the future, because of limitations such as licensing restrictions on the scope of care that may be provided by nonphysician providers.”

SOURCE: Sisko A et al. Health Aff. 2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05499.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

ICYMI: Rivaroxaban reduces VTE incidence in ambulatory cancer patients

While treatment with rivaroxaban did not significantly reduce venous thromboembolism incidence in high-risk ambulatory patients with cancer over the entire course of a 180-day intervention period (6.0% vs. 8.8% in controls; hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.40-1.09), it did reduce major bleeding incidence while patients were on treatment (2.0% vs. 6.4%; HR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.20 0.80), according to results from the multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase 3b CASSINI trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814630).

We reported this story at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology before it was published in the journal. Find our coverage at the link below.

While treatment with rivaroxaban did not significantly reduce venous thromboembolism incidence in high-risk ambulatory patients with cancer over the entire course of a 180-day intervention period (6.0% vs. 8.8% in controls; hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.40-1.09), it did reduce major bleeding incidence while patients were on treatment (2.0% vs. 6.4%; HR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.20 0.80), according to results from the multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase 3b CASSINI trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814630).

We reported this story at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology before it was published in the journal. Find our coverage at the link below.

While treatment with rivaroxaban did not significantly reduce venous thromboembolism incidence in high-risk ambulatory patients with cancer over the entire course of a 180-day intervention period (6.0% vs. 8.8% in controls; hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.40-1.09), it did reduce major bleeding incidence while patients were on treatment (2.0% vs. 6.4%; HR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.20 0.80), according to results from the multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase 3b CASSINI trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814630).

We reported this story at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology before it was published in the journal. Find our coverage at the link below.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Durable responses to ADC sacituzumab in mTNBC

The novel antibody-drug conjugate sacituzumab govitecan was associated with durable clinical responses in one third of patients with heavily pretreated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), investigators in a multicenter study found.

Among a cohort of 108 patients with TNBC, the objective response rate (ORR) to treatment with sacituzumab govitecan was 33.3%, which included three complete and 33 partial responses (CR and PR), with a median duration of response of 7.7 months, reported Aditya Bardia, MD, from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and his colleagues.

“The duration of treatment with sacituzumab govitecan-hziy was longer than with the immediate previous antitumor therapy (5.1 months vs. 2.5 months); this provides further evidence of clinical activity in patients with difficult-to-treat metastatic triple-negative breast,” they wrote in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Sacituzumab govitecan (the suffix “hziy” used in the article is not sanctioned by the FDA, according to an editor’s note) is an antibody-drug conjugate consisting of SN-38, the active metabolite of the topoisomerase I inhibitor irinotecan, linked to a humanized monoclonal antibody targeted to Trop-2, a cell-surface glycoprotein expressed in triple-negative breast cancers and most other epithelial malignancies.

The study, preliminary results of which were previously reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium in 2017, was part of a larger a phase 1/2 basket trial that resulted in sacituzumab govitecan receiving a breakthrough designation from the Food and Drug Administration.

The breast cancer cohort included 108 patients (107 women and one man; median age, 55 years) with TNBC who had received a median of 3 prior lines of anticancer therapies. Most had received taxanes (98%) and anthracyclines (86%).

At the time of data cutoff on December 1, 2017, the median duration of follow-up was 9.7 months. By that time, 100 of the 108 patients had discontinued therapy: 86 because of disease progression, three because of adverse events, 7 at the investigator’s discretion, and 2 for withdrawal of consent.

Four patients died during treatment; all of the deaths were judged to be caused by disease progression.

Grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurring in 10% or more of patients included neutropenia in 42% and anemia in 11%. Febrile neutropenia occurred in 9.3% of patients.

As noted before, the investigator-assessed ORR was 33.3%, and the median duration of response was 7.7 months. The ORR as assessed by independent central reviewers was 34.7%, and the median duration of response 9.1%. The clinical benefit rate, a composite of ORR plus stable disease of at a least 6 months duration, was 45.4%. The median progression-free survival was 5.5 months, and median overall survival was 13 months.

There were no significant differences in outcomes in a subgroup analysis broken down by patient age, metastatic disease, number of prior therapies, or presence of visceral metastases, the investigators noted, but they cautioned that the numbers were small, which led to wide confidence intervals, “and thus the homogeneity of clinical outcomes observed in these subgroups is weak and should be interpreted with caution,” they wrote.

The study was supported by Immunomedics. Dr. Bardia disclosed advisory board activities and institutional research grants from Immunomedics, Sanofi, and Radius Health. Multiple coauthors reported similar relationships with these and other companies.

SOURCE: Bardia A et al. NEJM 2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814213.

The novel antibody-drug conjugate sacituzumab govitecan was associated with durable clinical responses in one third of patients with heavily pretreated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), investigators in a multicenter study found.

Among a cohort of 108 patients with TNBC, the objective response rate (ORR) to treatment with sacituzumab govitecan was 33.3%, which included three complete and 33 partial responses (CR and PR), with a median duration of response of 7.7 months, reported Aditya Bardia, MD, from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and his colleagues.

“The duration of treatment with sacituzumab govitecan-hziy was longer than with the immediate previous antitumor therapy (5.1 months vs. 2.5 months); this provides further evidence of clinical activity in patients with difficult-to-treat metastatic triple-negative breast,” they wrote in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Sacituzumab govitecan (the suffix “hziy” used in the article is not sanctioned by the FDA, according to an editor’s note) is an antibody-drug conjugate consisting of SN-38, the active metabolite of the topoisomerase I inhibitor irinotecan, linked to a humanized monoclonal antibody targeted to Trop-2, a cell-surface glycoprotein expressed in triple-negative breast cancers and most other epithelial malignancies.

The study, preliminary results of which were previously reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium in 2017, was part of a larger a phase 1/2 basket trial that resulted in sacituzumab govitecan receiving a breakthrough designation from the Food and Drug Administration.

The breast cancer cohort included 108 patients (107 women and one man; median age, 55 years) with TNBC who had received a median of 3 prior lines of anticancer therapies. Most had received taxanes (98%) and anthracyclines (86%).

At the time of data cutoff on December 1, 2017, the median duration of follow-up was 9.7 months. By that time, 100 of the 108 patients had discontinued therapy: 86 because of disease progression, three because of adverse events, 7 at the investigator’s discretion, and 2 for withdrawal of consent.

Four patients died during treatment; all of the deaths were judged to be caused by disease progression.

Grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurring in 10% or more of patients included neutropenia in 42% and anemia in 11%. Febrile neutropenia occurred in 9.3% of patients.

As noted before, the investigator-assessed ORR was 33.3%, and the median duration of response was 7.7 months. The ORR as assessed by independent central reviewers was 34.7%, and the median duration of response 9.1%. The clinical benefit rate, a composite of ORR plus stable disease of at a least 6 months duration, was 45.4%. The median progression-free survival was 5.5 months, and median overall survival was 13 months.

There were no significant differences in outcomes in a subgroup analysis broken down by patient age, metastatic disease, number of prior therapies, or presence of visceral metastases, the investigators noted, but they cautioned that the numbers were small, which led to wide confidence intervals, “and thus the homogeneity of clinical outcomes observed in these subgroups is weak and should be interpreted with caution,” they wrote.

The study was supported by Immunomedics. Dr. Bardia disclosed advisory board activities and institutional research grants from Immunomedics, Sanofi, and Radius Health. Multiple coauthors reported similar relationships with these and other companies.

SOURCE: Bardia A et al. NEJM 2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814213.

The novel antibody-drug conjugate sacituzumab govitecan was associated with durable clinical responses in one third of patients with heavily pretreated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), investigators in a multicenter study found.

Among a cohort of 108 patients with TNBC, the objective response rate (ORR) to treatment with sacituzumab govitecan was 33.3%, which included three complete and 33 partial responses (CR and PR), with a median duration of response of 7.7 months, reported Aditya Bardia, MD, from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and his colleagues.

“The duration of treatment with sacituzumab govitecan-hziy was longer than with the immediate previous antitumor therapy (5.1 months vs. 2.5 months); this provides further evidence of clinical activity in patients with difficult-to-treat metastatic triple-negative breast,” they wrote in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Sacituzumab govitecan (the suffix “hziy” used in the article is not sanctioned by the FDA, according to an editor’s note) is an antibody-drug conjugate consisting of SN-38, the active metabolite of the topoisomerase I inhibitor irinotecan, linked to a humanized monoclonal antibody targeted to Trop-2, a cell-surface glycoprotein expressed in triple-negative breast cancers and most other epithelial malignancies.

The study, preliminary results of which were previously reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium in 2017, was part of a larger a phase 1/2 basket trial that resulted in sacituzumab govitecan receiving a breakthrough designation from the Food and Drug Administration.

The breast cancer cohort included 108 patients (107 women and one man; median age, 55 years) with TNBC who had received a median of 3 prior lines of anticancer therapies. Most had received taxanes (98%) and anthracyclines (86%).

At the time of data cutoff on December 1, 2017, the median duration of follow-up was 9.7 months. By that time, 100 of the 108 patients had discontinued therapy: 86 because of disease progression, three because of adverse events, 7 at the investigator’s discretion, and 2 for withdrawal of consent.

Four patients died during treatment; all of the deaths were judged to be caused by disease progression.

Grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurring in 10% or more of patients included neutropenia in 42% and anemia in 11%. Febrile neutropenia occurred in 9.3% of patients.

As noted before, the investigator-assessed ORR was 33.3%, and the median duration of response was 7.7 months. The ORR as assessed by independent central reviewers was 34.7%, and the median duration of response 9.1%. The clinical benefit rate, a composite of ORR plus stable disease of at a least 6 months duration, was 45.4%. The median progression-free survival was 5.5 months, and median overall survival was 13 months.

There were no significant differences in outcomes in a subgroup analysis broken down by patient age, metastatic disease, number of prior therapies, or presence of visceral metastases, the investigators noted, but they cautioned that the numbers were small, which led to wide confidence intervals, “and thus the homogeneity of clinical outcomes observed in these subgroups is weak and should be interpreted with caution,” they wrote.

The study was supported by Immunomedics. Dr. Bardia disclosed advisory board activities and institutional research grants from Immunomedics, Sanofi, and Radius Health. Multiple coauthors reported similar relationships with these and other companies.

SOURCE: Bardia A et al. NEJM 2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814213.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Sacituzumab govitecan induced responses in patients with heavily pretreated TNBC.

Major finding: The objective response rate among 108 patients with metastatic TNBC was 33.3%.

Study details: Phase 1/2 trial cohort of 107 women and one man with advanced triple-negative breast cancer.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Immunomedics. Dr. Bardia disclosed advisory board activities with and institutional research grants from Immunomedics, Sanofi, and Radius Health. Multiple coauthors reported similar relationships with these and other companies.

Source: Bardia A et al. NEJM. 2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814213.