User login

Seasonality of birth and psychiatric illness

“To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven.”

— Ecclesiastes

The month of birth is not just relevant to one’s astrological sign. It may have medical consequences. An impressive number of published studies have found that the month and season of birth may be related to a higher risk of various medical and psychiatric disorders.

For decades, it has been reported in more than 250 studies1 that a disproportionate number of individuals with schizophrenia are born during the winter months (January/February/March in the Northern Hemisphere and July/August/September in the Southern Hemisphere). This seasonal pattern was eventually linked to the lack of sunlight during winter months and a deficiency of vitamin D, a hormone that is critical for normal brain development. Recent studies have reported that very low serum levels of vitamin D during pregnancy significantly increase the risk of schizophrenia in offspring.2

But the plot thickens. Numerous studies over the past 20 to 30 years have reported an association between month or season of birth with sundry general medical and psychiatric conditions. Even longevity has been reported to vary with season of birth, with a longer life span for people born in autumn (October to December), compared with those born in spring (April to June).3 Of note, a longer life span for an individual born in autumn has been attributed to a higher birth weight during that season compared with those born in other seasons. In addition, the shorter life span of those with spring births has been attributed to factors during fetal life that increase the susceptibility to disease later in life (after age 50).

The following studies have reported an association between month/season of birth and general medical disorders:

- Higher rate of myopia for summer births4

- Tenfold higher risk of respiratory syntactical virus in babies born in January compared with October, and a 2 to 3 times higher risk of hospitalization5

- Higher rates of asthma during childhood for March and April births6

- Lower rate of lung cancer for winter births compared with all other seasons7

- An excess of colon and rectal cancer for people born in September, and the lowest rate for spring births8

- Lowest diabetes risk for summer births9

- For males: Cardiac mortality is 11% less likely for 4th-quarter births compared with 1st-quarter births. For females: Cancer mortality is lowest in 3rd-quarter vs 1st-quarter births10

- The peak risk for both Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma is for April births compared with other months11

- A strong trend for malignant neoplasm in males was reported for births during the 1st trimester of the year (January through April) compared with the rest of the year12

- Higher rate of spring births among patients who have insulin-dependent diabetes13

- Breast cancer is 5% higher for June births compared with December births14

- Higher risk of developing an allergy later in life for those born approximately 3 months before the main allergy season.15

The above studies may imply that birth seasonality is medical destiny. However, most such reports need further replication, or may be due to chance findings in various databases. However, they are worth considering as hypothesis-generating signals.

Continue to: And now for the risk of psychiatric disorders...

And now for the risk of psychiatric disorders and month or season of birth. Here, too, there are multiple published reports:

- Higher social anhedonia and schizoid features among persons born in June and July16

- Higher autism rates for children conceived in December to March compared with those conceived during summer months17

- In contrast to the above report, the risk of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom was higher for those born in summer18

- Another study labeled seasonality of birth in autism as “fiction”!19

- Significant spring births for persons with anxiety20

- Highest occurrence of postpartum depression in December21

- High prepartum depression in winter and postpartum depression in fall22

- Lower performance IQ among spring births23

- Disproportionate excess of births in April, May, and June for those who die by suicide24

- Suicide by burning oneself is higher among individuals born in January compared with any other month25

- Relative increase in March and August births among patients with anorexia26

- Season of birth is a predictor of emotional and behavioral regulation27

- Serotonin metabolites show a peak in spring and a trough in fall28

- Increase of spring births in individuals with Down syndrome29

- Excess of spring births among patients with Alzheimer’s disease.30

As with the seasonality of medical illness risk, the association of the month or season of birth with psychiatric disorders may be based on skewed samples or simply a chance finding. However, there may be some seasonal environmental factors that could increase the risk for disorders of the body or the brain/mind. The most plausible factors may be season-related fetal developmental disruptions caused by maternal infection, diet, lack of sunlight, temperature, substance use, or immune dysregulation from comorbid medical conditions during pregnancy. Some researchers have speculated that fluctuations in the availability of various fresh fruits and vegetables during certain seasons of the year may influence fetal development or increase the susceptibility to some medical disorders. This may be at the time of conception or during the 2nd trimester of pregnancy, when the brain develops.

On the other hand, those studies, published in peer-reviewed journals, may constitute a sophisticated form of “psychiatric astrology” whose credibility could be as suspect as the imaginative predictions of one’s horoscope in the daily newspaper…

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: henry.nasrallah@currentpsychiatry.com.

1. Torrey EF, Miller J, Rawlings R, et al. Seasonality of births in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. Schizophr Res. 1997;28(1):1-38.

2. McGrath J, Welham J, Pemberton M. Month of birth, hemisphere of birth and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(6):783-785.

3. Doblhammer G, Vaupel JW. Lifespan depends on month of birth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(5):2934-2939.

4. Mandel Y, Grotto I, El-Yaniv R, et al. Season of birth, natural light, and myopia. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(4):686-692.

5. Lloyd PC, May L, Hoffman D, et al. The effect of birth month on the risk of respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization in the first year of life in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(6):e135-e140.

6. Gazala E, Ron-Feldman V, Alterman M, et al. The association between birth season and future development of childhood asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006;41(12):1125-1128.

7. Hao Y, Yan L, Ke E, et al. Birth in winter can reduce the risk of lung cancer: A retrospective study of the birth season of patients with lung cancer in Beijing area, China. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34(4):511-518.

8. Francis NK, Curtis NJ, Noble E, et al. Is month of birth a risk factor for colorectal cancer? Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:5423765. doi: 10.1155/2017/5423765.

9. Si J, Yu C, Guo Y, et al; China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group. Season of birth and the risk of type 2 diabetes in adulthood: a prospective cohort study of 0.5 million Chinese adults. Diabetologia. 2017;60(5):836-842.

10. Sohn K. The influence of birth season on mortality in the United States. Am J Hum Biol. 2016;28(5):662-670.

11. Crump C, Sundquist J, Sieh W, et al. Season of birth and risk of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(11):2735-2739.

12. Stoupel E, Abramson E, Fenig E. Birth month of patients with malignant neoplasms: links to longevity? J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2012;23(2):57-60.

13. Rothwell PM, Gutnikov SA, McKinney PA, et al. Seasonality of birth in children with diabetes in Europe: multicentre cohort study. European Diabetes Study Group. BMJ. 1999;319(7214):887-888.

14. Yuen J, Ekbom A, Trichopoulos D, et al. Season of birth and breast cancer risk in Sweden. Br J Cancer. 1994;70(3):564-568.

15. Aalberse RC, Nieuwenhuys EJ, Hey M, et al. ‘Horoscope effect’ not only for seasonal but also for non-seasonal allergens. Clin Exp Allergy. 1992;22(11):1003-1006.

16. Kirkpatrick B, Messias E, LaPorte D. Schizoid-like features and season of birth in a nonpatient sample. Schizophr Res. 2008;103:151-155.

17. Zerbo O, Iosif AM, Delwiche L, et al. Month of conception and risk of autism. Epidemiology. 2011;22(4):469-475.

18. Hebert KJ, Miller LL, Joinson CJ. Association of autistic spectrum disorder with season of birth and conception in a UK cohort. Autism Res. 2010;3(4):185-190.

19. Landau EC, Cicchetti DV, Klin A, et al. Season of birth in autism: a fiction revisited. J Autism Dev Disord. 1999;29(5):385-393.

20. Parker G, Neilson M. Mental disorder and season of birth--a southern hemisphere study. Br J Psychiatry. 1976;129:355-361.

21. Sit D, Seltman H, Wisner KL. Seasonal effects on depression risk and suicidal symptoms in postpartum women. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(5):400-405.

22. Chan JE, Samaranayaka A, Paterson H. Seasonal and gestational variation in perinatal depression in a prospective cohort in New Zealand. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12912.

23. Grootendorst-van Mil NH, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Hofman A, et al. Brighter children? The association between seasonality of birth and child IQ in a population-based birth cohort. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e012406. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012406.

24. Salib E, Cortina-Borja M. Effect of month of birth on the risk of suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:416-422.

25. Salib E, Cortina-Borja M. An association between month of birth and method of suicide. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2010;14(1):8-17.

26. Brewerton TD, Dansky BS, O’Neil PM, et al. Seasonal patterns of birth for subjects with bulimia nervosa, binge eating, and purging: results from the National Women’s Study. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45(1):131-134.

27. Asano R, Tsuchiya KJ, Harada T, et al; for Hamamatsu Birth Cohort (HBC) Study Team. Season of birth predicts emotional and behavioral regulation in 18-month-old infants: Hamamatsu birth cohort for mothers and children (HBC Study). Front Public Health. 2016;4:152.

28. Luykx JJ, Bakker SC, Lentjes E, et al. Season of sampling and season of birth influence serotonin metabolite levels in human cerebrospinal fluid. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030497.

29. Videbech P, Nielsen J. Chromosome abnormalities and season of birth. Hum Genet. 1984;65(3):221-231.

30. Vézina H, Houde L, Charbonneau H, et al. Season of birth and Alzheimer’s disease: a population-based study in Saguenay-Lac-St-Jean/Québec (IMAGE Project). Psychol Med. 1996;26(1):143-149.

“To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven.”

— Ecclesiastes

The month of birth is not just relevant to one’s astrological sign. It may have medical consequences. An impressive number of published studies have found that the month and season of birth may be related to a higher risk of various medical and psychiatric disorders.

For decades, it has been reported in more than 250 studies1 that a disproportionate number of individuals with schizophrenia are born during the winter months (January/February/March in the Northern Hemisphere and July/August/September in the Southern Hemisphere). This seasonal pattern was eventually linked to the lack of sunlight during winter months and a deficiency of vitamin D, a hormone that is critical for normal brain development. Recent studies have reported that very low serum levels of vitamin D during pregnancy significantly increase the risk of schizophrenia in offspring.2

But the plot thickens. Numerous studies over the past 20 to 30 years have reported an association between month or season of birth with sundry general medical and psychiatric conditions. Even longevity has been reported to vary with season of birth, with a longer life span for people born in autumn (October to December), compared with those born in spring (April to June).3 Of note, a longer life span for an individual born in autumn has been attributed to a higher birth weight during that season compared with those born in other seasons. In addition, the shorter life span of those with spring births has been attributed to factors during fetal life that increase the susceptibility to disease later in life (after age 50).

The following studies have reported an association between month/season of birth and general medical disorders:

- Higher rate of myopia for summer births4

- Tenfold higher risk of respiratory syntactical virus in babies born in January compared with October, and a 2 to 3 times higher risk of hospitalization5

- Higher rates of asthma during childhood for March and April births6

- Lower rate of lung cancer for winter births compared with all other seasons7

- An excess of colon and rectal cancer for people born in September, and the lowest rate for spring births8

- Lowest diabetes risk for summer births9

- For males: Cardiac mortality is 11% less likely for 4th-quarter births compared with 1st-quarter births. For females: Cancer mortality is lowest in 3rd-quarter vs 1st-quarter births10

- The peak risk for both Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma is for April births compared with other months11

- A strong trend for malignant neoplasm in males was reported for births during the 1st trimester of the year (January through April) compared with the rest of the year12

- Higher rate of spring births among patients who have insulin-dependent diabetes13

- Breast cancer is 5% higher for June births compared with December births14

- Higher risk of developing an allergy later in life for those born approximately 3 months before the main allergy season.15

The above studies may imply that birth seasonality is medical destiny. However, most such reports need further replication, or may be due to chance findings in various databases. However, they are worth considering as hypothesis-generating signals.

Continue to: And now for the risk of psychiatric disorders...

And now for the risk of psychiatric disorders and month or season of birth. Here, too, there are multiple published reports:

- Higher social anhedonia and schizoid features among persons born in June and July16

- Higher autism rates for children conceived in December to March compared with those conceived during summer months17

- In contrast to the above report, the risk of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom was higher for those born in summer18

- Another study labeled seasonality of birth in autism as “fiction”!19

- Significant spring births for persons with anxiety20

- Highest occurrence of postpartum depression in December21

- High prepartum depression in winter and postpartum depression in fall22

- Lower performance IQ among spring births23

- Disproportionate excess of births in April, May, and June for those who die by suicide24

- Suicide by burning oneself is higher among individuals born in January compared with any other month25

- Relative increase in March and August births among patients with anorexia26

- Season of birth is a predictor of emotional and behavioral regulation27

- Serotonin metabolites show a peak in spring and a trough in fall28

- Increase of spring births in individuals with Down syndrome29

- Excess of spring births among patients with Alzheimer’s disease.30

As with the seasonality of medical illness risk, the association of the month or season of birth with psychiatric disorders may be based on skewed samples or simply a chance finding. However, there may be some seasonal environmental factors that could increase the risk for disorders of the body or the brain/mind. The most plausible factors may be season-related fetal developmental disruptions caused by maternal infection, diet, lack of sunlight, temperature, substance use, or immune dysregulation from comorbid medical conditions during pregnancy. Some researchers have speculated that fluctuations in the availability of various fresh fruits and vegetables during certain seasons of the year may influence fetal development or increase the susceptibility to some medical disorders. This may be at the time of conception or during the 2nd trimester of pregnancy, when the brain develops.

On the other hand, those studies, published in peer-reviewed journals, may constitute a sophisticated form of “psychiatric astrology” whose credibility could be as suspect as the imaginative predictions of one’s horoscope in the daily newspaper…

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: henry.nasrallah@currentpsychiatry.com.

“To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven.”

— Ecclesiastes

The month of birth is not just relevant to one’s astrological sign. It may have medical consequences. An impressive number of published studies have found that the month and season of birth may be related to a higher risk of various medical and psychiatric disorders.

For decades, it has been reported in more than 250 studies1 that a disproportionate number of individuals with schizophrenia are born during the winter months (January/February/March in the Northern Hemisphere and July/August/September in the Southern Hemisphere). This seasonal pattern was eventually linked to the lack of sunlight during winter months and a deficiency of vitamin D, a hormone that is critical for normal brain development. Recent studies have reported that very low serum levels of vitamin D during pregnancy significantly increase the risk of schizophrenia in offspring.2

But the plot thickens. Numerous studies over the past 20 to 30 years have reported an association between month or season of birth with sundry general medical and psychiatric conditions. Even longevity has been reported to vary with season of birth, with a longer life span for people born in autumn (October to December), compared with those born in spring (April to June).3 Of note, a longer life span for an individual born in autumn has been attributed to a higher birth weight during that season compared with those born in other seasons. In addition, the shorter life span of those with spring births has been attributed to factors during fetal life that increase the susceptibility to disease later in life (after age 50).

The following studies have reported an association between month/season of birth and general medical disorders:

- Higher rate of myopia for summer births4

- Tenfold higher risk of respiratory syntactical virus in babies born in January compared with October, and a 2 to 3 times higher risk of hospitalization5

- Higher rates of asthma during childhood for March and April births6

- Lower rate of lung cancer for winter births compared with all other seasons7

- An excess of colon and rectal cancer for people born in September, and the lowest rate for spring births8

- Lowest diabetes risk for summer births9

- For males: Cardiac mortality is 11% less likely for 4th-quarter births compared with 1st-quarter births. For females: Cancer mortality is lowest in 3rd-quarter vs 1st-quarter births10

- The peak risk for both Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma is for April births compared with other months11

- A strong trend for malignant neoplasm in males was reported for births during the 1st trimester of the year (January through April) compared with the rest of the year12

- Higher rate of spring births among patients who have insulin-dependent diabetes13

- Breast cancer is 5% higher for June births compared with December births14

- Higher risk of developing an allergy later in life for those born approximately 3 months before the main allergy season.15

The above studies may imply that birth seasonality is medical destiny. However, most such reports need further replication, or may be due to chance findings in various databases. However, they are worth considering as hypothesis-generating signals.

Continue to: And now for the risk of psychiatric disorders...

And now for the risk of psychiatric disorders and month or season of birth. Here, too, there are multiple published reports:

- Higher social anhedonia and schizoid features among persons born in June and July16

- Higher autism rates for children conceived in December to March compared with those conceived during summer months17

- In contrast to the above report, the risk of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom was higher for those born in summer18

- Another study labeled seasonality of birth in autism as “fiction”!19

- Significant spring births for persons with anxiety20

- Highest occurrence of postpartum depression in December21

- High prepartum depression in winter and postpartum depression in fall22

- Lower performance IQ among spring births23

- Disproportionate excess of births in April, May, and June for those who die by suicide24

- Suicide by burning oneself is higher among individuals born in January compared with any other month25

- Relative increase in March and August births among patients with anorexia26

- Season of birth is a predictor of emotional and behavioral regulation27

- Serotonin metabolites show a peak in spring and a trough in fall28

- Increase of spring births in individuals with Down syndrome29

- Excess of spring births among patients with Alzheimer’s disease.30

As with the seasonality of medical illness risk, the association of the month or season of birth with psychiatric disorders may be based on skewed samples or simply a chance finding. However, there may be some seasonal environmental factors that could increase the risk for disorders of the body or the brain/mind. The most plausible factors may be season-related fetal developmental disruptions caused by maternal infection, diet, lack of sunlight, temperature, substance use, or immune dysregulation from comorbid medical conditions during pregnancy. Some researchers have speculated that fluctuations in the availability of various fresh fruits and vegetables during certain seasons of the year may influence fetal development or increase the susceptibility to some medical disorders. This may be at the time of conception or during the 2nd trimester of pregnancy, when the brain develops.

On the other hand, those studies, published in peer-reviewed journals, may constitute a sophisticated form of “psychiatric astrology” whose credibility could be as suspect as the imaginative predictions of one’s horoscope in the daily newspaper…

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: henry.nasrallah@currentpsychiatry.com.

1. Torrey EF, Miller J, Rawlings R, et al. Seasonality of births in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. Schizophr Res. 1997;28(1):1-38.

2. McGrath J, Welham J, Pemberton M. Month of birth, hemisphere of birth and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(6):783-785.

3. Doblhammer G, Vaupel JW. Lifespan depends on month of birth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(5):2934-2939.

4. Mandel Y, Grotto I, El-Yaniv R, et al. Season of birth, natural light, and myopia. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(4):686-692.

5. Lloyd PC, May L, Hoffman D, et al. The effect of birth month on the risk of respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization in the first year of life in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(6):e135-e140.

6. Gazala E, Ron-Feldman V, Alterman M, et al. The association between birth season and future development of childhood asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006;41(12):1125-1128.

7. Hao Y, Yan L, Ke E, et al. Birth in winter can reduce the risk of lung cancer: A retrospective study of the birth season of patients with lung cancer in Beijing area, China. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34(4):511-518.

8. Francis NK, Curtis NJ, Noble E, et al. Is month of birth a risk factor for colorectal cancer? Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:5423765. doi: 10.1155/2017/5423765.

9. Si J, Yu C, Guo Y, et al; China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group. Season of birth and the risk of type 2 diabetes in adulthood: a prospective cohort study of 0.5 million Chinese adults. Diabetologia. 2017;60(5):836-842.

10. Sohn K. The influence of birth season on mortality in the United States. Am J Hum Biol. 2016;28(5):662-670.

11. Crump C, Sundquist J, Sieh W, et al. Season of birth and risk of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(11):2735-2739.

12. Stoupel E, Abramson E, Fenig E. Birth month of patients with malignant neoplasms: links to longevity? J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2012;23(2):57-60.

13. Rothwell PM, Gutnikov SA, McKinney PA, et al. Seasonality of birth in children with diabetes in Europe: multicentre cohort study. European Diabetes Study Group. BMJ. 1999;319(7214):887-888.

14. Yuen J, Ekbom A, Trichopoulos D, et al. Season of birth and breast cancer risk in Sweden. Br J Cancer. 1994;70(3):564-568.

15. Aalberse RC, Nieuwenhuys EJ, Hey M, et al. ‘Horoscope effect’ not only for seasonal but also for non-seasonal allergens. Clin Exp Allergy. 1992;22(11):1003-1006.

16. Kirkpatrick B, Messias E, LaPorte D. Schizoid-like features and season of birth in a nonpatient sample. Schizophr Res. 2008;103:151-155.

17. Zerbo O, Iosif AM, Delwiche L, et al. Month of conception and risk of autism. Epidemiology. 2011;22(4):469-475.

18. Hebert KJ, Miller LL, Joinson CJ. Association of autistic spectrum disorder with season of birth and conception in a UK cohort. Autism Res. 2010;3(4):185-190.

19. Landau EC, Cicchetti DV, Klin A, et al. Season of birth in autism: a fiction revisited. J Autism Dev Disord. 1999;29(5):385-393.

20. Parker G, Neilson M. Mental disorder and season of birth--a southern hemisphere study. Br J Psychiatry. 1976;129:355-361.

21. Sit D, Seltman H, Wisner KL. Seasonal effects on depression risk and suicidal symptoms in postpartum women. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(5):400-405.

22. Chan JE, Samaranayaka A, Paterson H. Seasonal and gestational variation in perinatal depression in a prospective cohort in New Zealand. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12912.

23. Grootendorst-van Mil NH, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Hofman A, et al. Brighter children? The association between seasonality of birth and child IQ in a population-based birth cohort. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e012406. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012406.

24. Salib E, Cortina-Borja M. Effect of month of birth on the risk of suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:416-422.

25. Salib E, Cortina-Borja M. An association between month of birth and method of suicide. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2010;14(1):8-17.

26. Brewerton TD, Dansky BS, O’Neil PM, et al. Seasonal patterns of birth for subjects with bulimia nervosa, binge eating, and purging: results from the National Women’s Study. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45(1):131-134.

27. Asano R, Tsuchiya KJ, Harada T, et al; for Hamamatsu Birth Cohort (HBC) Study Team. Season of birth predicts emotional and behavioral regulation in 18-month-old infants: Hamamatsu birth cohort for mothers and children (HBC Study). Front Public Health. 2016;4:152.

28. Luykx JJ, Bakker SC, Lentjes E, et al. Season of sampling and season of birth influence serotonin metabolite levels in human cerebrospinal fluid. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030497.

29. Videbech P, Nielsen J. Chromosome abnormalities and season of birth. Hum Genet. 1984;65(3):221-231.

30. Vézina H, Houde L, Charbonneau H, et al. Season of birth and Alzheimer’s disease: a population-based study in Saguenay-Lac-St-Jean/Québec (IMAGE Project). Psychol Med. 1996;26(1):143-149.

1. Torrey EF, Miller J, Rawlings R, et al. Seasonality of births in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. Schizophr Res. 1997;28(1):1-38.

2. McGrath J, Welham J, Pemberton M. Month of birth, hemisphere of birth and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(6):783-785.

3. Doblhammer G, Vaupel JW. Lifespan depends on month of birth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(5):2934-2939.

4. Mandel Y, Grotto I, El-Yaniv R, et al. Season of birth, natural light, and myopia. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(4):686-692.

5. Lloyd PC, May L, Hoffman D, et al. The effect of birth month on the risk of respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization in the first year of life in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(6):e135-e140.

6. Gazala E, Ron-Feldman V, Alterman M, et al. The association between birth season and future development of childhood asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006;41(12):1125-1128.

7. Hao Y, Yan L, Ke E, et al. Birth in winter can reduce the risk of lung cancer: A retrospective study of the birth season of patients with lung cancer in Beijing area, China. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34(4):511-518.

8. Francis NK, Curtis NJ, Noble E, et al. Is month of birth a risk factor for colorectal cancer? Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:5423765. doi: 10.1155/2017/5423765.

9. Si J, Yu C, Guo Y, et al; China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group. Season of birth and the risk of type 2 diabetes in adulthood: a prospective cohort study of 0.5 million Chinese adults. Diabetologia. 2017;60(5):836-842.

10. Sohn K. The influence of birth season on mortality in the United States. Am J Hum Biol. 2016;28(5):662-670.

11. Crump C, Sundquist J, Sieh W, et al. Season of birth and risk of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(11):2735-2739.

12. Stoupel E, Abramson E, Fenig E. Birth month of patients with malignant neoplasms: links to longevity? J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2012;23(2):57-60.

13. Rothwell PM, Gutnikov SA, McKinney PA, et al. Seasonality of birth in children with diabetes in Europe: multicentre cohort study. European Diabetes Study Group. BMJ. 1999;319(7214):887-888.

14. Yuen J, Ekbom A, Trichopoulos D, et al. Season of birth and breast cancer risk in Sweden. Br J Cancer. 1994;70(3):564-568.

15. Aalberse RC, Nieuwenhuys EJ, Hey M, et al. ‘Horoscope effect’ not only for seasonal but also for non-seasonal allergens. Clin Exp Allergy. 1992;22(11):1003-1006.

16. Kirkpatrick B, Messias E, LaPorte D. Schizoid-like features and season of birth in a nonpatient sample. Schizophr Res. 2008;103:151-155.

17. Zerbo O, Iosif AM, Delwiche L, et al. Month of conception and risk of autism. Epidemiology. 2011;22(4):469-475.

18. Hebert KJ, Miller LL, Joinson CJ. Association of autistic spectrum disorder with season of birth and conception in a UK cohort. Autism Res. 2010;3(4):185-190.

19. Landau EC, Cicchetti DV, Klin A, et al. Season of birth in autism: a fiction revisited. J Autism Dev Disord. 1999;29(5):385-393.

20. Parker G, Neilson M. Mental disorder and season of birth--a southern hemisphere study. Br J Psychiatry. 1976;129:355-361.

21. Sit D, Seltman H, Wisner KL. Seasonal effects on depression risk and suicidal symptoms in postpartum women. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(5):400-405.

22. Chan JE, Samaranayaka A, Paterson H. Seasonal and gestational variation in perinatal depression in a prospective cohort in New Zealand. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12912.

23. Grootendorst-van Mil NH, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Hofman A, et al. Brighter children? The association between seasonality of birth and child IQ in a population-based birth cohort. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e012406. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012406.

24. Salib E, Cortina-Borja M. Effect of month of birth on the risk of suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:416-422.

25. Salib E, Cortina-Borja M. An association between month of birth and method of suicide. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2010;14(1):8-17.

26. Brewerton TD, Dansky BS, O’Neil PM, et al. Seasonal patterns of birth for subjects with bulimia nervosa, binge eating, and purging: results from the National Women’s Study. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45(1):131-134.

27. Asano R, Tsuchiya KJ, Harada T, et al; for Hamamatsu Birth Cohort (HBC) Study Team. Season of birth predicts emotional and behavioral regulation in 18-month-old infants: Hamamatsu birth cohort for mothers and children (HBC Study). Front Public Health. 2016;4:152.

28. Luykx JJ, Bakker SC, Lentjes E, et al. Season of sampling and season of birth influence serotonin metabolite levels in human cerebrospinal fluid. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030497.

29. Videbech P, Nielsen J. Chromosome abnormalities and season of birth. Hum Genet. 1984;65(3):221-231.

30. Vézina H, Houde L, Charbonneau H, et al. Season of birth and Alzheimer’s disease: a population-based study in Saguenay-Lac-St-Jean/Québec (IMAGE Project). Psychol Med. 1996;26(1):143-149.

Fulfillment within success: A physician’s dilemma

They say success without fulfillment is of little value in life. Whether this concept is actually driving the spate of depression and substance abuse currently experienced by youth and middle-aged adults in developed countries is rarely discussed and needs to be explored.

We have all reflected on the tragic ends of Anthony Bourdain, Kate Spade, and Robin Williams. Much has been said about the accolades they achieved and the heights they scaled, and just as much about their struggles with substance abuse over the years. Sensational portrayals by the media also encouraged youth to spend time dissecting the details of these high-profile deaths, lending popularity to the notion of suicide contagion. But somewhere in the myriad theories and conclusions, we still seem baffled by the questions of why these suicides occurred, and why no one had seen them coming.

As humans, we are designed to build. For many people, including physicians, the final product is a rewarding career built on years of hard work, or a flourishing family to look back on be proud of. Sometimes, however, these larger ideas barely intersect with our pictures of success.

As physicians and high achievers, we dream of goals and ambitions and set stringent deadlines for achieving them. Falling short sometimes finds us grappling with self-punishment and doubt. When one goal is achieved, another one is automatically created, or the goal post is pushed further. And the cycle continues.

Having said this, I will ask: What are you looking for? What is it that will give you a sense of purpose?

This is not a redundant question, nor is it an easy one. So are you really taking the time to think about it? Does any of this border on self-reflection and self-awareness for you? If it does, then developing that insight into yourself is perhaps a better way of serving your patients.

Peace and gratification often lie in the little things; not everything you do has to be acknowledged with an award. There is a sense of fulfillment that comes from developing others. The key is to realize that there is never a moment to start doing that—it is an ongoing journey. Therefore, give generously, of your time, of your skills, of your knowledge, but above all, of your kindness. Do it because in the end, you will have something to look back on and be proud of. Do it because maybe somewhere you will find meaning in it. And your success may not be bereft of fulfillment.

They say success without fulfillment is of little value in life. Whether this concept is actually driving the spate of depression and substance abuse currently experienced by youth and middle-aged adults in developed countries is rarely discussed and needs to be explored.

We have all reflected on the tragic ends of Anthony Bourdain, Kate Spade, and Robin Williams. Much has been said about the accolades they achieved and the heights they scaled, and just as much about their struggles with substance abuse over the years. Sensational portrayals by the media also encouraged youth to spend time dissecting the details of these high-profile deaths, lending popularity to the notion of suicide contagion. But somewhere in the myriad theories and conclusions, we still seem baffled by the questions of why these suicides occurred, and why no one had seen them coming.

As humans, we are designed to build. For many people, including physicians, the final product is a rewarding career built on years of hard work, or a flourishing family to look back on be proud of. Sometimes, however, these larger ideas barely intersect with our pictures of success.

As physicians and high achievers, we dream of goals and ambitions and set stringent deadlines for achieving them. Falling short sometimes finds us grappling with self-punishment and doubt. When one goal is achieved, another one is automatically created, or the goal post is pushed further. And the cycle continues.

Having said this, I will ask: What are you looking for? What is it that will give you a sense of purpose?

This is not a redundant question, nor is it an easy one. So are you really taking the time to think about it? Does any of this border on self-reflection and self-awareness for you? If it does, then developing that insight into yourself is perhaps a better way of serving your patients.

Peace and gratification often lie in the little things; not everything you do has to be acknowledged with an award. There is a sense of fulfillment that comes from developing others. The key is to realize that there is never a moment to start doing that—it is an ongoing journey. Therefore, give generously, of your time, of your skills, of your knowledge, but above all, of your kindness. Do it because in the end, you will have something to look back on and be proud of. Do it because maybe somewhere you will find meaning in it. And your success may not be bereft of fulfillment.

They say success without fulfillment is of little value in life. Whether this concept is actually driving the spate of depression and substance abuse currently experienced by youth and middle-aged adults in developed countries is rarely discussed and needs to be explored.

We have all reflected on the tragic ends of Anthony Bourdain, Kate Spade, and Robin Williams. Much has been said about the accolades they achieved and the heights they scaled, and just as much about their struggles with substance abuse over the years. Sensational portrayals by the media also encouraged youth to spend time dissecting the details of these high-profile deaths, lending popularity to the notion of suicide contagion. But somewhere in the myriad theories and conclusions, we still seem baffled by the questions of why these suicides occurred, and why no one had seen them coming.

As humans, we are designed to build. For many people, including physicians, the final product is a rewarding career built on years of hard work, or a flourishing family to look back on be proud of. Sometimes, however, these larger ideas barely intersect with our pictures of success.

As physicians and high achievers, we dream of goals and ambitions and set stringent deadlines for achieving them. Falling short sometimes finds us grappling with self-punishment and doubt. When one goal is achieved, another one is automatically created, or the goal post is pushed further. And the cycle continues.

Having said this, I will ask: What are you looking for? What is it that will give you a sense of purpose?

This is not a redundant question, nor is it an easy one. So are you really taking the time to think about it? Does any of this border on self-reflection and self-awareness for you? If it does, then developing that insight into yourself is perhaps a better way of serving your patients.

Peace and gratification often lie in the little things; not everything you do has to be acknowledged with an award. There is a sense of fulfillment that comes from developing others. The key is to realize that there is never a moment to start doing that—it is an ongoing journey. Therefore, give generously, of your time, of your skills, of your knowledge, but above all, of your kindness. Do it because in the end, you will have something to look back on and be proud of. Do it because maybe somewhere you will find meaning in it. And your success may not be bereft of fulfillment.

Can lifestyle modifications delay or prevent Alzheimer’s disease?

Clinicians have devoted strenuous efforts to secondary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) by diagnosing and treating patients as early as possible. Unfortunately, there is no cure for AD, and the field has witnessed recurrent failures of several pharmacotherapy candidates with either symptomatic or disease-modifying properties.1 An estimated one-third of AD cases can be attributed to modifiable risk factors.2 Thus, implementing primary prevention measures by addressing modifiable risk factors thought to contribute to the disease, with the goal of reducing the risk of developing AD, or at least delaying its onset, is a crucial public health strategy.

Cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hyperhomocysteinemia, obesity, and smoking, have emerged as substantive risk factors for AD.3 Optimal management of these major risk factors, especially in mid-life, may be a preventive approach against AD. Although detailing the evidence on the impact of managing cardiovascular risk factors to delay or prevent AD is beyond the scope of this article, it is becoming clear that “what is good for the heart is good for the brain.”

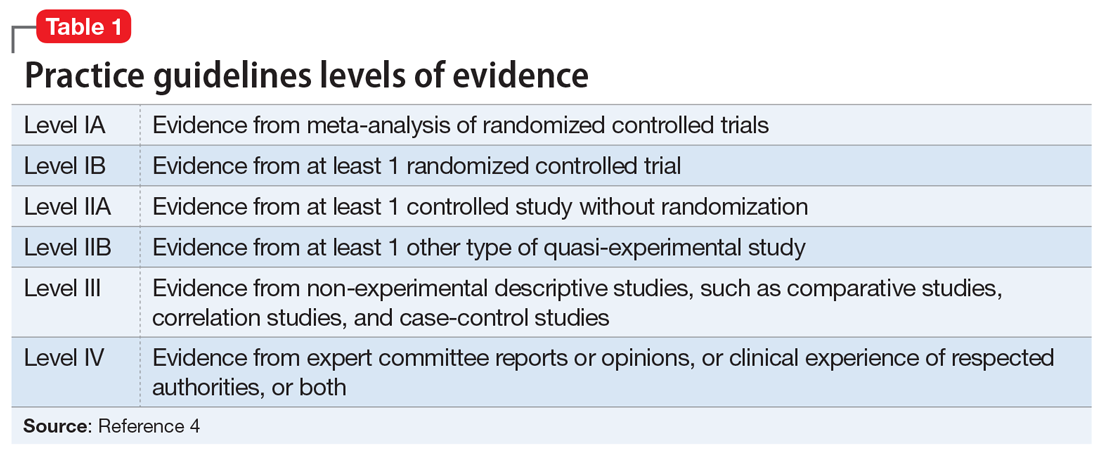

Additional modifiable risk factors are related to lifestyle habits, such as physical exercise, mental and social activity, meditation/spiritual activity, and diet. This article reviews the importance of pursuing a healthy lifestyle in delaying AD, with the corresponding levels of evidence that support each specific lifestyle modification. The levels of evidence are defined in Table 1.4

Physical exercise

Twenty-one percent of AD cases in the United States are attributable to physical inactivity.5 In addition to its beneficial effect on metabolic syndrome, in animal and human research, regular exercise has been shown to have direct neuroprotective effects. High levels of physical activity increase hippocampal neurogenesis and neuroplasticity, increase vascular circulation in the brain regions implicated in AD, and modulate inflammatory mediators as well as brain growth factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1).6

The definition of regular physical exercise varies across the literature, but usually implies aerobic exercise—an ongoing activity sufficient to increase the heart rate and the need for oxygen, sustained for 20 to 30 minutes per session.7 Modalities include household activities and leisure-time activities. In a large prospective cohort study, Scarmeas et al8 categorized leisure-time activities into 3 types:

- light (walking, dancing, calisthenics, golfing, bowling, gardening, horseback riding)

- moderate (bicycling, swimming, hiking, playing tennis)

- vigorous (aerobic dancing, jogging, playing handball).

These types of physical exercise were weighed by the frequency of participation per week. Compared with being physically inactive, low levels of weekly physical activity (0.1 hours of vigorous, 0.8 hours of moderate, or 1.3 hours of light exercise) were associated with a 29% to 41% lower risk of developing AD, while higher weekly physical activity (1.3 hours of vigorous, 2.3 hours of moderate, or 3.8 hours of light exercise) were associated with a 37% to 50% lower risk (level III).8

In another 20-year cohort study, engaging in leisure-time physical activity at least twice a week in mid-life was significantly associated with a reduced risk of AD, after adjusting for age, sex, education, follow-up time, locomotor disorders, apolipoprotein E (ApoE) genotype, vascular disorders, smoking, and alcohol intake (level III).9 Moreover, a systematic review of 29 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed that aerobic exercise training, such as brisk walking, jogging, and biking, was associated with improvements in attention, processing speed, executive function, and memory among healthy older adults and those with mild cognitive impairment (MCI; level IA).10

Continue to: From a pathophysiological standpoint...

From a pathophysiological standpoint, higher levels of physical exercise in cognitively intact older adults have been associated with reduced brain amyloid beta deposits, especially in ApoE4 carriers.11 This inverse relationship also has been demonstrated in patients who are presymptomatic who carry 1 of the 3 known autosomal dominant mutations for the familial forms of AD.12

Overall, physicians should recommend that patients—especially those with cardiovascular risk factors that increase their risk for AD—exercise regularly by following the guidelines of the American Heart Association or the American College of Sports Medicine.13 These include muscle-strengthening activities (legs, hips, back, abdomen, shoulders, and arms) at least 2 days/week, in addition to either 30 minutes/day of moderate-intensity aerobic activity such as brisk walking, 5 days/week; or 25 minutes of vigorous aerobic activity such as jogging and running, 3 days/week14 (level IA evidence for overall improvement in cognitive function; level III evidence for AD delay/risk reduction). Neuromotor exercise, such as yoga and tai chi, and flexibility exercise such as muscle stretching, especially after a hot bath, 2 to 3 days/week are also recommended (level III).15

Mental activity

Nineteen percent of AD cases worldwide and 7% in the United States. can be attributed to low educational attainment, which is associated with low brain cognitive reserve.5 Cognitive resilience in later life may be enhanced by building brain reserves through intellectual stimulation, which affects neuronal branching and plasticity.16 Higher levels of complex mental activities measured across the lifespan, such as education, occupation, reading, and writing, are correlated with significantly less hippocampal volume shrinkage over time.17 Frequent participation in mentally stimulating activities—such as listening to the radio; reading newspapers, magazines, or books; playing games (cards, checkers, crosswords or other puzzles); and visiting museums—was associated with an up to 64% reduction in the odds of developing AD in a cohort of cognitively intact older adults followed for 4 years.18 The correlation between mental activity and AD was found to be independent of physical activity, social activity, or baseline cognitive function.19

In a large cohort of cognitively intact older adults (mean age 70), engaging in a mentally stimulating activity (craft activities, computer use, or going to the theater/movies) once to twice a week was significantly associated with a reduced incidence of amnestic MCI.20 Another prospective 21-year study demonstrated a significant reduction in AD risk in community-dwelling cognitively intact older adults (age 75 to 85) who participated in cognitively stimulating activities, such as reading books or newspapers, writing for pleasure, doing crossword puzzles, playing board games or cards, or playing musical instruments, several times/week.21

Growing scientific evidence also suggests that lifelong multilingualism can delay AD onset by 4 to 5 years.22 Multilingualism is associated with greater cognitive reserve, gray matter volume, functional connectivity and white matter density.23

Continue to: Physicians should encourage their patients...

Physicians should encourage their patients to engage in intellectually stimulating activities and creative leisure-time activities several times/week to enhance their cognitive reserves and delay AD onset (level III evidence with respect to AD risk reduction/delay).

Social activity

Social engagement may be an additional protective factor against AD. In a large 4-year prospective study, increased loneliness in cognitively intact older adults doubled the risk of AD.24 Data from the large French cohort PAQUID (Personnes Agées QUID) emphasized the importance of a patient’s social network as a protective factor against AD. In this cohort, the perception of reciprocity in relationships with others (the perception that a person had received more than he or she had given) was associated with a 53% reduction in AD risk (level III).25 In another longitudinal cohort study, social activity was found to decrease the incidence of subjective cognitive decline, which is a prodromal syndrome for MCI and AD (level III).26

A major confounder in studies assessing for social activity is the uncertainty if social withdrawal is a modifiable risk factor or an early manifestation of AD, since apathetic patients with AD tend to be socially withdrawn.27 Another limitation of measuring the impact of social activity relative to AD risk is the difficulty in isolating social activities from activities that have physical and mental activity components, such as leisure-time activities.28

Meditation/spiritual activity

Chronic psychological stress is believed to compromise limbic structures that regulate stress-related behaviors and the memory network, which might explain how being prone to psychological distress may be associated with MCI or AD.29 Cognitive stress may increase the oxidative stress and telomere shortening implicated in the neurodegenerative processes of AD.30 In one study, participants who were highly prone to psychological distress were found to be at 3 times increased risk for developing AD, after adjusting for depression symptoms and physical and mental activities (level III).31 By reducing chronic psychological stress, meditation techniques offer a promising preventive option against AD.

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBI) have gained increased attention in the past decade. They entail directing one’s attention towards the present moment, thereby decreasing ruminative thoughts and stress arousal.32 Recent RCTs have shown that MBI may promote brain health in older adults not only by improving psychological well-being but also by improving attentional control33 and functional connectivity in brain regions implicated in executive functioning,34 as well as by modulating inflammatory processes implicated in AD.35 Furthermore, an RCT of patients diagnosed with MCI found that compared with memory enhancement training, a weekly 60-minute yoga session improved memory and executive functioning.36

Continue to: Kirtan Kriya is a medication technique...

Kirtan Kriya is a meditation technique that is easy to learn and practice by older adults and can improve memory in patients at risk for developing AD.37 However, more rigorous RCTs conducted in larger samples of older adults are needed to better evaluate the effect of all meditation techniques for delaying or preventing AD (level IB with respect to improvement in cognitive functioning/level III for AD delay/risk reduction).38

Spiritual activities, such as going to places of worship or religious meditation, have been associated with a lower prevalence of AD. Attending religious services, gatherings, or retreats involves a social component because these activities often are practiced in groups. They also confer a method of dealing with psychological distress and depression. Additionally, frequent readings of religious texts represents a mentally stimulating activity that may also contribute to delaying/preventing AD (level III).39

Diet

In the past decade, a growing body of evidence has linked diet to cognition. Individuals with a higher intake of calories and fat are at higher risk for developing AD.40 The incidence of AD rose in Japan after the country transitioned to a more Westernized diet.41 A modern Western diet rich in saturated fatty acids and simple carbohydrates may negatively impact hippocampus-mediated functions such as memory and learning, and is associated with an increased risk of AD.42 In contrast with high-glycemic and fatty diets, a “healthy diet” is associated with a decrease in beta-amyloid burden, inflammation, and oxidative stress.43,44

Studies focusing on dietary patterns rather than a single nutrient for delaying or preventing AD have yielded more robust and consistent results.45 In a recent meta-analysis, adhering to a Mediterranean diet—which is rich in fruits and vegetables, whole grains, olive oil, and fish; moderate in some dairy products and wine; and low in red meat—was associated with a decreased risk of AD; this evidence was derived mostly from epidemiologic studies.46 Scarmeas et al8 found that high adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with 32% to 40% reduced risk of AD. Combining this diet with physical exercise was associated with an up to 67% reduced risk (level III). The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, which is rich in total grains, fruits, vegetables, and dairy products, but low in sodium and sweets, correlated with neurocognitive improvement in patients with hypertension.47 Both the Mediterranean and DASH diets have been associated with better cognitive function48 and slower cognitive decline.49 Thus, an attempt to combine the neuroprotective components from both diets led to the creation of the MIND (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) diet, which also has been associated with a lower incidence of AD.50

Besides specific diets, some food groups have also been found to promote brain health and may help delay or prevent AD. Berries have the highest amount of antioxidants of all fruit. Among vegetables, tomatoes and green leafy vegetables have the highest amount of nutrients for the brain. Nuts, such as walnuts, which are rich in omega-3 fatty acids, are also considered “power foods” for the brain; however, they should be consumed in moderation because they are also rich in fat. Monounsaturated fatty acids, which are found in olives and olive oil, are also beneficial for the brain. Among the 3 types of omega-3 fatty acids, the most important for cognition is docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) because it constitutes 40% of all fatty acids in the brain. Mainly found in oily fish, DHA has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that may delay or prevent AD. Low levels of DHA have been found in patients with AD.51

Continue to: Curcumin, which is derived from...

Curcumin, which is derived from the curry spice turmeric, is a polyphenol with anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-amyloid properties that may have a promising role in preventing AD in cognitively intact individuals. Initial trials with curcumin have yielded mixed results on cognition, which was partly related to the low solubility and bioavailability of its formulation.52 However, a recent 18-month double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial found positive effects on memory and attention, as well as reduction of amyloid plaques and tau tangles deposition in the brain, in non-demented older adults age 51 to 84 who took Theracumin, a highly absorptive oral form of curcumin dispersed with colloidal nanoparticles.53 A longer follow-up is required to determine if curcumin can delay or prevent AD.

Alcohol

The role of alcohol in AD prevention is controversial. Overall, data from prospective studies has shown that low to moderate alcohol consumption may be associated with a reduced risk of AD (level III).54 Alcohol drinking in mid-life showed a U-shaped relationship with cognitive impairment; both abstainers and heavy drinkers had an increased risk of cognitive decline compared with light to moderate drinkers (level III).55 Binge drinking significantly increased the odds of cognitive decline, even after controlling for total alcohol consumption per week.55

The definition of low-to-moderate drinking varies substantially among countries. In addition, the size and amount of alcohol contained in a standard drink may differ.56 According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA),57 moderate drinking is defined as up to 1 drink daily for women and 2 drinks daily for men. Binge drinking involves drinking >4 drinks for women and >5 drinks for men, in approximately 2 hours, at least monthly. In the United States, one standard drink contains 14 grams of pure alcohol, which is usually found in 12 ounces of regular beer, 5 ounces of wine, and 1.5 ounces of distilled spirits (vodka or whiskey).58

In a 5-year prospective Canadian study, having 1 drink weekly (especially wine) was associated with an up to 50% reduced risk of AD (level III).59 In the French cohort PAQUID, mild drinkers (<1 to 2 drinks/day) and moderate drinkers (3 to 4 drinks daily) had a reduced incidence of AD compared with non-drinkers. Wine was the most frequently consumed beverage in this study.60 Other studies have found cognitive benefits from mild to moderate drinking regardless of beverage type.54 However, a recent study that included a 30-year follow-up failed to find a significant protective effect of light drinking over abstinence in terms of hippocampal atrophy.61 Atrophy of the hippocampus was correlated with increasing alcohol amounts in a dose-dependent manner, starting at 7 to 14 drinks/week (level III).61

Research has shown that moderate and heavy alcohol use or misuse can directly induce microglial activation and inflammatory mediators’ release, which induce amyloid beta pathology and leads to brain atrophy.62 Hence, non-drinkers should not be advised to begin drinking, because of the lack of RCTs and the concern that beginning to drink may lead to heavy drinking. All drinkers should be advised to adhere to the NIAAA recommendations.13

Continue to: Coffee/tea

Coffee/tea

Although studies of caffeinated coffee have been heterogeneous and yielded mixed results (beneficial effect vs no effect on delaying cognitive decline), systematic reviews and meta-analyses of cross-sectional, case-control, and longitudinal cohort studies have found a general trend towards a favorable preventive role (level III).63-65 Caffeine exhibits its neuroprotective effect by increasing brain serotonin and acetylcholine, and by stabilizing blood-brain-barrier integrity.66 Moreover, in an animal study, mice given caffeine in their drinking water from young adulthood into older age had lower amyloid beta plasma levels compared with those given decaffeinated water.67 These findings suggest that in humans, 5 cups of regular caffeinated coffee daily, equivalent to 500 mg of caffeine,

An Italian study showed that older adults who don’t or rarely drink coffee (<1 cup daily) and those who recently increased their consumption pattern to >1 cup daily had a higher incidence of MCI than those who habitually consumed 1 to 2 cups daily.69 Therefore, it is not recommended to advise a change in coffee drinking pattern in old age. Older adults who are coffee drinkers should, however, be educated about the association between heavier caffeine intake and anxiety, insomnia, and cardiac arrhythmias.70

Despite its more modest caffeine levels, green tea is rich in polyphenols, which belong to the family of catechins and are characterized by antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.71 In a Japanese cohort, higher green tea consumption (up to 1 cup daily) was associated with a decreased incidence of MCI in older adults.72 More studies are needed to confirm its potential preventative role in AD.

Which lifestyle change is the most important?

Focusing on a single lifestyle change may be insufficient, especially because the bulk of evidence for individual interventions comes from population-based cohort studies (level III), rather than strong RCTs with a long follow-up. There is increasing evidence that combining multiple lifestyle modifications may yield better outcomes in maintaining or improving cognition.73

The Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER), a large, 2-year RCT that included community-dwelling older adults (age 60 to 77) with no diagnosis of major neurocognitive disorder, found that compared with regular health advice, multi-domain interventions reduced cognitive decline and improved overall cognition, executive functioning, and processing speed. The interventions evaluated in this study combined the following 4 modalities74:

- a healthy diet according to the Finnish nutrition recommendations (eating vegetables, fruits, and berries [minimum: 500 g/d], whole grain cereals [several times a day], and fish [2 to 3 times/week]; using low-salt products; consuming fat-free or low-fat milk products; and limiting red meat consumption to <500 g/week

- regular physical exercise tailored for improving muscle strength (1 to 3 times/week) coupled with aerobic exercise (2 to 5 times/week)

- cognitive training, including group sessions that have a social activity component and computer-based individual sessions 3 times/week that target episodic and working memory and executive functioning

- optimal management of cardiovascular risk factors.

Continue to: This multi-domain approach...

This multi-domain approach for lifestyle modification should be strongly recommended to cognitively intact older patients (level IB).

Modeled after the FINGER study, the Alzheimer’s Association U.S. Study to Protect Brain Health Through Lifestyle Intervention to Reduce Risk (U.S. POINTER) is a 2-year, multicenter, controlled clinical trial aimed at testing the ability of a multidimensional lifestyle intervention to prevent AD in at-risk older adults (age 60 to 79, with established metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors). Interventions include a combination of physical exercise, nutritional counseling and management, cognitive and social stimulation, and improved management of cardiovascular risk factors. Recruitment for this large-scale trial was estimated to begin in January 2019 (NCT03688126).75

On a practical basis, Desai et al13 have proposed a checklist (Table 213) that physicians can use in their routine consultations to improve primary prevention of AD among their older patients.

Bottom Line

Advise patients that pursuing a healthy lifestyle is a key to delaying or preventing Alzheimer’s disease. This involves managing cardiovascular risk factors and a combination of staying physically, mentally, socially, and spiritually active, in addition to adhering to a healthy diet such as the Mediterranean diet.

Related Resources

- Anderson K, Grossberg GT. Brain games to slow cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(8):536-537.

- Small G, Vorgan G. The memory prescription: Dr. Garry Small’s 14-day plan to keep your brain and body young. New York, NY: Hyperion; 2004.

- Small G, Vorgan G. The Alzheimer’s prevention program; keep your brain healthy for the rest of your life. New York, NY: Workman Publishing Company, Inc.; 2012.

Drug Brand Name

Curcumin • Theracurmin

1. Mehta D, Jackson R, Paul G, et al. Why do trials for Alzheimer’s disease drugs keep failing? A discontinued drug perspective for 2010-2015. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26(6):735-739.

2. Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, et al. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(8):788-794.

3. Meng XF, Yu JT, Wang HF, et al. Midlife vascular risk factors and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(4):1295-1310.

4. Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, et al. Developing clinical guidelines. West J Med. 1999;170(6):348-351.

5. Barnes DE, Yaffe Y. The projected impact of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(9):819-828.

6. Cotman CW, Berchtold NC, Christie LA. Exercise builds brain health: key roles of growth factor cascades and inflammation. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30(9):464-472.

7. Ahlskog JE, Geda YE, Graff-Radford NR, et al. Physical exercise as a preventive or disease-modifying treatment of dementia and brain aging. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(9):876-884.

8. Scarmeas N, Luchsinger JA, Schupf N, et al. Physical activity, diet, and risk of Alzheimer Disease. JAMA. 2009;302(6):627-637.

9. Rovio S, Kåreholt I, Helkala EL, et al. Leisure-time physical activity at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(11):705-711.

10. Smith PJ et al. Aerobic exercise and neurocognitive performance: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(3):239-252.

11. Brown BM, Peiffer JJ, Taddei K, et al. Physical activity and amyloid-beta plasma and brain levels: results from the Australian imaging, biomarkers and lifestyle study of ageing. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(8):875-881.

12. Brown BM, Sohrabi HR, Taddei K, et al. Habitual exercise levels are associated with cerebral amyloid load in presymptomatic autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(11):1197-1206.

13. Desai AK, Grossberg GT, Chibnall JT. Healthy brain aging: a road map. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(1):1-16.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical activity: how much physical activity do older adults need?

15. Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, et al; American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1334-1359.

16. Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113);2673-2734.

17. Valenzuela MJ, Sachdev P, Wen W, et al. Lifespan mental activity predicts diminished rate of hippocampal atrophy. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2598. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002598.

18. Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Bienias JL, et al. Cognitive activity and incident AD in a population-based sample of older persons. Neurology. 2002;59(12):1910-1914.

19. Wilson RS, Scherr PA, Schneider JA, et al. Relation of cognitive activity to risk of developing Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;69(20):1911-1920.

20. Krell-Roesch J, Vemuri P, Pink A, et al. Association between mentally stimulating activities in late life and the outcome of incident mild cognitive impairment, with an analysis of the apoe ε4 genotype. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(3):332-338.

21. Verghese J, Lipton RB, Katz MJ, et al. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(25):2508-2516.

22. Klein RM, Christie J, Parkvall M. Does multilingualism affect the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease?: a worldwide analysis by country. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:463-467.

23. Grundy JG, Anderson JAE, Bialystok E. Neural correlates of cognitive processing in monolinguals and bilinguals. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017;1396(1):183-201.

24. Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Arnold SE, et al. Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(2):234-240.

25. Amieva H, Stoykova R, Matharan F, et al. What aspects of social network are protective for dementia? Not the quantity but the quality of social interactions is protective up to 15 years later. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(9):905-911.

26. Kuiper JS, Oude Voshaar RC, Zuidema SU, et al. The relationship between social functioning and subjective memory complaints in older persons: a population-based longitudinal cohort study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(10):1059-1071.

27. Robert P, Onyike CU, Leentjens AF, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(2):98-104.

28. Marioni RE, Proust-Lima C, Amieva H, et al. Social activity, cognitive decline and dementia risk: a 20-year prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1089.

29. Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Boyle PA, et al. Chronic distress and incidence of mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2007;68(24):2085-2092.

30. Cai Z, Yan LJ, Ratka A. Telomere shortening and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2013;15(1):25-48.

31. Wilson RS, Arnold SE, Schneider JA, et al. Chronic psychological distress and risk of Alzheimer’s disease in old age. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;27(3):143-153.

32. Epel E, Daubenmier J, Moskowitz JT, et al. Can meditation slow rate of cellular aging? Cognitive stress, mindfulness, and telomeres. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1172:34-53.

33. Malinowski P, Moore AW, Mead Br, et al. Mindful aging: the effects of regular brief mindfulness practice on electrophysiological markers of cognitive and affective processing in older adults. Mindfulness (N Y). 2017;8(1):78-94.

34. Taren AA, Gianaros PJ, Greco CM, et al. Mindfulness meditation training and executive control network resting state functional connectivity: a randomized controlled trial. Psychosom Med. 2017;79(6):674-683.

35. Fountain-Zaragoza S, Prakash RS. Mindfulness training for healthy aging: impact on attention, well-being, and inflammation. Front in Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:11.

36. Eyre HA, Siddarth P, Acevedo B, et al. A randomized controlled trial of Kundalini yoga in mild cognitive impairment. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(4):557-567.

37. Khalsa DS. Stress, meditation, and Alzheimer’s disease prevention: where the evidence stands. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48(1):1-12.

38. Berk L, van Boxtel M, van Os J. Can mindfulness-based interventions influence cognitive functioning in older adults? A review and considerations for future research. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(11):1113-1120.

39. Hosseini S, Chaurasia A, Oremus M. The effect of religion and spirituality on cognitive function: a systematic review. Gerontologist. 2017. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx024.

40. Luchsinger JA, Tang MX, Shea S, et al. Caloric intake and the risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(8):1258-1263.

41. Grant WB. Trends in diet and Alzheimer’s disease during the nutrition transition in Japan and developing countries. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;38(3):611-620.

42. Kanoski SE, Davidson TL. Western diet consumption and cognitive impairment: links to hippocampal dysfunction and obesity. Physiol Behav. 2011;103(1):59-68.

43. Hu N, Yu JT, Tan L, et al. Nutrition and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:524820. doi: 10.1155/2013/524820.

44. Taylor MK, Sullivan DK, Swerdlow RH, et al. A high-glycemic diet is associated with cerebral amyloid burden in cognitively normal older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(6):1463-1470.

45. van de Rest O, Berendsen AM, Haveman-Nies A, et al. Dietary patterns, cognitive decline, and dementia: a systematic review. Adv Nutr. 2015;6(2):154-168.

46. Petersson SD, Philippou E. Mediterranean diet, cognitive function, and dementia: a systematic review of the evidence. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(5):889-904.

47. Smith PJ, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, et al. Effects of the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet, exercise, and caloric restriction on neurocognition in overweight adults with high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2010;55(6):1331-1338.

48. Wengreen H, Munger RG, Cutler A, et al. Prospective study of dietary approaches to stop hypertension- and Mediterranean-style dietary patterns and age-related cognitive change: the Cache County study on memory, health and aging. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(5):1263-1271.

49. Tangney CC, Li H, Wang Y, et al. Relation of DASH- and Mediterranean-like dietary patterns to cognitive decline in older persons. Neurology. 2014;83(16):1410-1416.

50. Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, et al. MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(9):1007-1014.

51. Desai AK, Rush J, Naveen L, et al. Nutrition and nutritional supplements to promote brain health. In: Hartman-Stein PE, Rue AL, eds. Enhancing cognitive fitness in adults: a guide to the use and development of community-based programs. New York, NY: Springer; 2011:249-269.

52. Goozee KG, Shah TM, Sohrabi HR, et al. Examining the potential clinical value of curcumin in the prevention and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Nutr. 2016;115(3):449-465.

53. Small GW, Siddarth P, Li Z, et al. Memory and brain amyloid and tau effects of a bioavailable form of curcumin in non-demented adults: a double-blind, placebo-controlled 18-month trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(3):266-277.

54. Kim JW, Lee DY, Lee BC, et al. Alcohol and cognition in the elderly: a review. Psychiatry Investig. 2012;9(1):8-16.

55. Virtaa JJ, Järvenpää T, Heikkilä K, et al. Midlife alcohol consumption and later risk of cognitive impairment: a twin follow-up study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(3):939-948.

56. Kerr WC, Stockwell T. Understanding standard drinks and drinking guidelines. Drug and Alcohol Rev. 2012;31(2):200-205.

57. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking levels defined. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking. Accessed December 9, 2017.

58. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. What is a standard drink? https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/what-standard-drink. Accessed November 9, 2017.

59. Lindsay J, Laurin D, Verreault R, et al. Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective analysis from the Canadian study of health and aging. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(5):445-453.

60. Orgogozo JM, Dartigues JF, Lafont S, et al. Wine consumption and dementia in the elderly: a prospective community study in the Bordeaux area. Rev Neurol (Paris). 1997;153(3):185-192.

61. Topiwala A, Allan CL, Valkanova V, et al. Moderate alcohol consumption as risk factor for adverse brain outcomes and cognitive decline: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357.

62. Venkataraman A, Kalk N, Sewell G, et al. Alcohol and Alzheimer’s disease-does alcohol dependence contribute to beta-amyloid deposition, neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease? Alcohol Alcohol. 2017;52(2):151-158.

63. Ma QP, Huang C, Cui QY, et al. Meta-analysis of the association between tea intake and the risk of cognitive disorders. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0165861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165861.

64. Santos C, Costa J, Santos J, et al. Caffeine intake and dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 1):S187-204.

65. Panza F, Solfrizzi V, Barulli MR, et al. Coffee, tea, and caffeine consumption and prevention of late-life cognitive decline and dementia: a systematic review. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19(3):313-328.

66. Wierzejska R. Can coffee consumption lower the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease? A literature review. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13(3):507-514.

67. Arendash GW, Cao C. Caffeine and coffee as therapeutics against Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20 (Suppl 1):S117-S126.

68. Eskelinen MH, Ngandu T, Tuomilehto J, et al. Midlife coffee and tea drinking and the risk of late-life dementia: a population-based CAIDE study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16(1):85-91.

69. Solfrizzi V, Panza F, Imbimbo BP, et al. Coffee consumption habits and the risk of mild cognitive impairment: the Italian longitudinal study on aging. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47(4):889-899.

70. Vittoria Mattioli. Beverages of daily life: impact of caffeine on atrial fibrillation. J Atr Fibrillation. 2014;7(2):1133.

71. Chacko SM, Thambi PT, Kuttan R, et al. Beneficial effects of green tea: a literature review. Chin Med. 2010;5:13.

72. Noguchi-Shinohara M, Yuki S, Dohmoto C, et al. Consumption of green tea, but not black tea or coffee, is associated with reduced risk of cognitive decline. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096013.

73. Schneider N, Yvon C. A review of multidomain interventions to support healthy cognitive ageing. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(3):252-257.

74. Ngandu T, Lehitsalo J, Solomon A, et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9984):2255-2263.

75. U.S. National Library of Medicing. ClinicalTrials.gov. U.S. study to protect brain health through lifestyle intervention to reduce risk (POINTER). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03688126?term=pointer&cond=Alzheimer+Disease&rank=1. Published September 28, 2018. Accessed November 3, 2018.

Clinicians have devoted strenuous efforts to secondary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) by diagnosing and treating patients as early as possible. Unfortunately, there is no cure for AD, and the field has witnessed recurrent failures of several pharmacotherapy candidates with either symptomatic or disease-modifying properties.1 An estimated one-third of AD cases can be attributed to modifiable risk factors.2 Thus, implementing primary prevention measures by addressing modifiable risk factors thought to contribute to the disease, with the goal of reducing the risk of developing AD, or at least delaying its onset, is a crucial public health strategy.

Cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hyperhomocysteinemia, obesity, and smoking, have emerged as substantive risk factors for AD.3 Optimal management of these major risk factors, especially in mid-life, may be a preventive approach against AD. Although detailing the evidence on the impact of managing cardiovascular risk factors to delay or prevent AD is beyond the scope of this article, it is becoming clear that “what is good for the heart is good for the brain.”

Additional modifiable risk factors are related to lifestyle habits, such as physical exercise, mental and social activity, meditation/spiritual activity, and diet. This article reviews the importance of pursuing a healthy lifestyle in delaying AD, with the corresponding levels of evidence that support each specific lifestyle modification. The levels of evidence are defined in Table 1.4

Physical exercise