User login

Purple-red papules on foot

An 88-year-old Caucasian man of Italian ancestry came into our clinic with multiple, painful purple-red “growths” on his left foot that he’d had for several years (FIGURE 1).

The patient had no systemic complaints (no fever, chills, weight loss, night sweats). He had a history of hypertension, a cardiac valve replacement, and chronic back pain (secondary to a motor vehicle accident). He was taking warfarin and nadolol.

The patient had multiple, 0.1– to 0.5-cm purple-red papules and nodules on the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the left foot, with associated moderate lower extremity edema and mottled dyspigmentation.

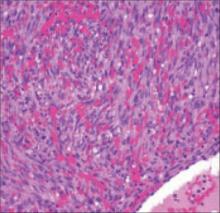

We did a punch biopsy, which showed a nodular neoplasm composed of moderately plump, spindle-shaped cells in short interweaving fascicles and numerous extravasated erythrocytes in the spaces (“vascular slits”) between the spindle-shaped cells (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 1

Painful papules and nodules

FIGURE 2

Hematoxylin/eosin stain

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Kaposi’s sarcoma

Classic Kaposi’s sarcoma is a rare mesenchymal tumor most often seen in elderly men of Mediterranean or Ashkenazi Jewish origin with an annual incidence in the United States of between 0.02% and 0.06%, with a peak occurring in the 5th to 8th decade of life.1 (Two-thirds of cases develop after the age of 50.) Population-based studies in the United States have shown a male-to-female ratio of 4:1.1

First described by the Hungarian dermatologist Moritz Kaposi in 1872, Kaposi’s sarcoma assumed prominence during the emerging HIV epidemic and is now the most common tumor in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).2

Recent research has implicated the human herpes virus–8 (HHV–8) as an inductive agent (necessary though not sufficient) in all epidemiologic subsets of the disease.2

There are 4 principal clinical variants of Kaposi’s sarcoma:

- classic (or chronic),

- African endemic (includes childhood lymphadenopathic),

- transplant-associated, and

- AIDS-related.

What you’ll see

Clinically, classic Kaposi’s sarcoma often first manifests as blue-red, well-demarcated, painless macules confined to the distal lower extremities.3 These slow-growing lesions may enlarge to forms papules and plaques, or progress to nodules and tumors. Unilateral involvement is often observed at the outset of the disease, with potential centripetal spread occurring late-in-course.3

Early lesions are generally soft, spongy, and “angiomatous,” while in the advanced state, lesional skin becomes hard, solid, and brown in color.3 Edema of the surrounding tissue is common. In addition to the skin, classic Kaposi’s sarcoma also involves mucosal sites (especially the oral and gastrointestinal mucosae).

Differential includes melanocytic nevus

A differential diagnosis for classic Kaposi’s sarcoma includes stasis dermatitis (“acroangiodermatitis”), melanocytic nevus, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, granuloma annulare, arthropod assault, and dermatofibroma/dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DF/DFSP).

Melanocytic nevi, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, granuloma annulare, and DF/DFSP ordinarily feature single lesions, while Kaposi’s sarcoma has multiple lesions. An arthropod assault is pruritic, and stasis dermatitis typically has dilated/varicose veins.

Histology will confirm your suspicions

While epidemiological and clinical factors may suggest classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, a final diagnosis ultimately rests on confirmatory histology. The pathology of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma (like all of the variant subtypes) is based solely on stage of the lesion.

Early patch-stage lesions exhibit papillary dermal proliferation of small, angulated vessels lined by bland endothelial cells with an accompanying sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

As the disease progresses to the plaque stage, the vascular proliferation expands into the reticular dermis and subcutis. The transition to nodular Kaposi’s sarcoma develops when a population of spindle cells expressing endothelial markers occurs between the “vascular slits” (FIGURE 2).

Chemotherapy for rapidly progressive disease

There is minimal evidence-based data for the treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Treatment options for limited disease include surgical excision, cryotherapy, laser ablation, topical retinoids (alitretinoin), interferon-alpha, and radiation.1

If rapidly progressive disease (>10 new lesions per month) exists, the most effective treatment remains systemic chemotherapy (vincristine, doxorubicin, vinblastine,4 bleomycin,4 or paclitaxel5). The benefits of chemotherapy can last for months—and even years.

Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy does the trick

We treated our patient with liquid nitrogen cryotherapy that was applied at regular 4- to 6-week intervals over several months. After 3 months, our patient’s lesions were nearly resolved. We followed him monthly thereafter.

Correspondence

John Patrick Welsh, MD, Associates in Dermatology, 4727 Friendship Avenue, Suite 300, Pittsburgh, PA 15224-1778; jp_welsh@hotmail.com.

1. Iscovich J, Boffetta P, Franceschi S, Azizi E, Sarid R. Classic Kaposi sarcoma: epidemiology and risk factors. Cancer. 2000;88:500-517.

2. Pellet C, Kerob D, Dupuy A, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viremia is associated with the progression of classic and endemic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:621-627.

3. Schwartz R. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151.

4. Brambilla L, Miedico A, Ferrucci S, et al. Combination of vinblastine and bleomycin as first line therapy in advanced classic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1090-1094.

5. Baskan EB, Tunali S, Adim SB, et al. Treatment of advanced classic Kaposi’s sarcoma with weekly low-dose paclitaxel therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1441-1443.

An 88-year-old Caucasian man of Italian ancestry came into our clinic with multiple, painful purple-red “growths” on his left foot that he’d had for several years (FIGURE 1).

The patient had no systemic complaints (no fever, chills, weight loss, night sweats). He had a history of hypertension, a cardiac valve replacement, and chronic back pain (secondary to a motor vehicle accident). He was taking warfarin and nadolol.

The patient had multiple, 0.1– to 0.5-cm purple-red papules and nodules on the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the left foot, with associated moderate lower extremity edema and mottled dyspigmentation.

We did a punch biopsy, which showed a nodular neoplasm composed of moderately plump, spindle-shaped cells in short interweaving fascicles and numerous extravasated erythrocytes in the spaces (“vascular slits”) between the spindle-shaped cells (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 1

Painful papules and nodules

FIGURE 2

Hematoxylin/eosin stain

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Kaposi’s sarcoma

Classic Kaposi’s sarcoma is a rare mesenchymal tumor most often seen in elderly men of Mediterranean or Ashkenazi Jewish origin with an annual incidence in the United States of between 0.02% and 0.06%, with a peak occurring in the 5th to 8th decade of life.1 (Two-thirds of cases develop after the age of 50.) Population-based studies in the United States have shown a male-to-female ratio of 4:1.1

First described by the Hungarian dermatologist Moritz Kaposi in 1872, Kaposi’s sarcoma assumed prominence during the emerging HIV epidemic and is now the most common tumor in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).2

Recent research has implicated the human herpes virus–8 (HHV–8) as an inductive agent (necessary though not sufficient) in all epidemiologic subsets of the disease.2

There are 4 principal clinical variants of Kaposi’s sarcoma:

- classic (or chronic),

- African endemic (includes childhood lymphadenopathic),

- transplant-associated, and

- AIDS-related.

What you’ll see

Clinically, classic Kaposi’s sarcoma often first manifests as blue-red, well-demarcated, painless macules confined to the distal lower extremities.3 These slow-growing lesions may enlarge to forms papules and plaques, or progress to nodules and tumors. Unilateral involvement is often observed at the outset of the disease, with potential centripetal spread occurring late-in-course.3

Early lesions are generally soft, spongy, and “angiomatous,” while in the advanced state, lesional skin becomes hard, solid, and brown in color.3 Edema of the surrounding tissue is common. In addition to the skin, classic Kaposi’s sarcoma also involves mucosal sites (especially the oral and gastrointestinal mucosae).

Differential includes melanocytic nevus

A differential diagnosis for classic Kaposi’s sarcoma includes stasis dermatitis (“acroangiodermatitis”), melanocytic nevus, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, granuloma annulare, arthropod assault, and dermatofibroma/dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DF/DFSP).

Melanocytic nevi, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, granuloma annulare, and DF/DFSP ordinarily feature single lesions, while Kaposi’s sarcoma has multiple lesions. An arthropod assault is pruritic, and stasis dermatitis typically has dilated/varicose veins.

Histology will confirm your suspicions

While epidemiological and clinical factors may suggest classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, a final diagnosis ultimately rests on confirmatory histology. The pathology of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma (like all of the variant subtypes) is based solely on stage of the lesion.

Early patch-stage lesions exhibit papillary dermal proliferation of small, angulated vessels lined by bland endothelial cells with an accompanying sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

As the disease progresses to the plaque stage, the vascular proliferation expands into the reticular dermis and subcutis. The transition to nodular Kaposi’s sarcoma develops when a population of spindle cells expressing endothelial markers occurs between the “vascular slits” (FIGURE 2).

Chemotherapy for rapidly progressive disease

There is minimal evidence-based data for the treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Treatment options for limited disease include surgical excision, cryotherapy, laser ablation, topical retinoids (alitretinoin), interferon-alpha, and radiation.1

If rapidly progressive disease (>10 new lesions per month) exists, the most effective treatment remains systemic chemotherapy (vincristine, doxorubicin, vinblastine,4 bleomycin,4 or paclitaxel5). The benefits of chemotherapy can last for months—and even years.

Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy does the trick

We treated our patient with liquid nitrogen cryotherapy that was applied at regular 4- to 6-week intervals over several months. After 3 months, our patient’s lesions were nearly resolved. We followed him monthly thereafter.

Correspondence

John Patrick Welsh, MD, Associates in Dermatology, 4727 Friendship Avenue, Suite 300, Pittsburgh, PA 15224-1778; jp_welsh@hotmail.com.

An 88-year-old Caucasian man of Italian ancestry came into our clinic with multiple, painful purple-red “growths” on his left foot that he’d had for several years (FIGURE 1).

The patient had no systemic complaints (no fever, chills, weight loss, night sweats). He had a history of hypertension, a cardiac valve replacement, and chronic back pain (secondary to a motor vehicle accident). He was taking warfarin and nadolol.

The patient had multiple, 0.1– to 0.5-cm purple-red papules and nodules on the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the left foot, with associated moderate lower extremity edema and mottled dyspigmentation.

We did a punch biopsy, which showed a nodular neoplasm composed of moderately plump, spindle-shaped cells in short interweaving fascicles and numerous extravasated erythrocytes in the spaces (“vascular slits”) between the spindle-shaped cells (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 1

Painful papules and nodules

FIGURE 2

Hematoxylin/eosin stain

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Kaposi’s sarcoma

Classic Kaposi’s sarcoma is a rare mesenchymal tumor most often seen in elderly men of Mediterranean or Ashkenazi Jewish origin with an annual incidence in the United States of between 0.02% and 0.06%, with a peak occurring in the 5th to 8th decade of life.1 (Two-thirds of cases develop after the age of 50.) Population-based studies in the United States have shown a male-to-female ratio of 4:1.1

First described by the Hungarian dermatologist Moritz Kaposi in 1872, Kaposi’s sarcoma assumed prominence during the emerging HIV epidemic and is now the most common tumor in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).2

Recent research has implicated the human herpes virus–8 (HHV–8) as an inductive agent (necessary though not sufficient) in all epidemiologic subsets of the disease.2

There are 4 principal clinical variants of Kaposi’s sarcoma:

- classic (or chronic),

- African endemic (includes childhood lymphadenopathic),

- transplant-associated, and

- AIDS-related.

What you’ll see

Clinically, classic Kaposi’s sarcoma often first manifests as blue-red, well-demarcated, painless macules confined to the distal lower extremities.3 These slow-growing lesions may enlarge to forms papules and plaques, or progress to nodules and tumors. Unilateral involvement is often observed at the outset of the disease, with potential centripetal spread occurring late-in-course.3

Early lesions are generally soft, spongy, and “angiomatous,” while in the advanced state, lesional skin becomes hard, solid, and brown in color.3 Edema of the surrounding tissue is common. In addition to the skin, classic Kaposi’s sarcoma also involves mucosal sites (especially the oral and gastrointestinal mucosae).

Differential includes melanocytic nevus

A differential diagnosis for classic Kaposi’s sarcoma includes stasis dermatitis (“acroangiodermatitis”), melanocytic nevus, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, granuloma annulare, arthropod assault, and dermatofibroma/dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DF/DFSP).

Melanocytic nevi, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, granuloma annulare, and DF/DFSP ordinarily feature single lesions, while Kaposi’s sarcoma has multiple lesions. An arthropod assault is pruritic, and stasis dermatitis typically has dilated/varicose veins.

Histology will confirm your suspicions

While epidemiological and clinical factors may suggest classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, a final diagnosis ultimately rests on confirmatory histology. The pathology of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma (like all of the variant subtypes) is based solely on stage of the lesion.

Early patch-stage lesions exhibit papillary dermal proliferation of small, angulated vessels lined by bland endothelial cells with an accompanying sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

As the disease progresses to the plaque stage, the vascular proliferation expands into the reticular dermis and subcutis. The transition to nodular Kaposi’s sarcoma develops when a population of spindle cells expressing endothelial markers occurs between the “vascular slits” (FIGURE 2).

Chemotherapy for rapidly progressive disease

There is minimal evidence-based data for the treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Treatment options for limited disease include surgical excision, cryotherapy, laser ablation, topical retinoids (alitretinoin), interferon-alpha, and radiation.1

If rapidly progressive disease (>10 new lesions per month) exists, the most effective treatment remains systemic chemotherapy (vincristine, doxorubicin, vinblastine,4 bleomycin,4 or paclitaxel5). The benefits of chemotherapy can last for months—and even years.

Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy does the trick

We treated our patient with liquid nitrogen cryotherapy that was applied at regular 4- to 6-week intervals over several months. After 3 months, our patient’s lesions were nearly resolved. We followed him monthly thereafter.

Correspondence

John Patrick Welsh, MD, Associates in Dermatology, 4727 Friendship Avenue, Suite 300, Pittsburgh, PA 15224-1778; jp_welsh@hotmail.com.

1. Iscovich J, Boffetta P, Franceschi S, Azizi E, Sarid R. Classic Kaposi sarcoma: epidemiology and risk factors. Cancer. 2000;88:500-517.

2. Pellet C, Kerob D, Dupuy A, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viremia is associated with the progression of classic and endemic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:621-627.

3. Schwartz R. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151.

4. Brambilla L, Miedico A, Ferrucci S, et al. Combination of vinblastine and bleomycin as first line therapy in advanced classic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1090-1094.

5. Baskan EB, Tunali S, Adim SB, et al. Treatment of advanced classic Kaposi’s sarcoma with weekly low-dose paclitaxel therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1441-1443.

1. Iscovich J, Boffetta P, Franceschi S, Azizi E, Sarid R. Classic Kaposi sarcoma: epidemiology and risk factors. Cancer. 2000;88:500-517.

2. Pellet C, Kerob D, Dupuy A, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viremia is associated with the progression of classic and endemic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:621-627.

3. Schwartz R. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151.

4. Brambilla L, Miedico A, Ferrucci S, et al. Combination of vinblastine and bleomycin as first line therapy in advanced classic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1090-1094.

5. Baskan EB, Tunali S, Adim SB, et al. Treatment of advanced classic Kaposi’s sarcoma with weekly low-dose paclitaxel therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1441-1443.

How to make exercise counseling more effective: Lessons from rural America

- To help overweight patients and those with a sedentary lifestyle to adopt and stick with an exercise regimen, develop a detailed and realistic plan with their help, and follow up with them periodically to see how they’re doing.

Purpose: Exercise counseling by primary care physicians has been shown to improve physical activity in patients. However, the prevalence and effectiveness of physician counseling is unknown in rural populations that are at increased risk for chronic diseases.

Methods: Using a population-based telephone survey at baseline and again at 1-year follow-up, we assessed physical activity behavior among 1141 adults (75% female, 95% white) living within 12 rural communities of Missouri, Tennessee, and Arkansas. We tested the association between physician counseling and patients meeting current physical activity recommendations using logistic regression analysis controlling for demographic variables.

Results: Participants who saw a doctor for regular care were 54% more likely to be physically active (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]=1.54; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04-2.28). Overweight adults (body mass index [BMI]=25-29.9 kg/m2) who had been advised by their physician to exercise more were nearly 5 times more likely to meet physical activity recommendations if their doctor helped develop an exercise plan (aOR=4.99; 95% CI, 1.69-14.73).

Overweight individuals who received additional follow-up with the exercise plan from their doctor had a 5½-fold increase in likelihood of meeting physical activity recommendations (P<.05).

In the overall sample, patients were significantly more likely to initiate (P=.01) and maintain (P=.002) physical activity when the physician prescribed and followed up on an exercise plan.

Conclusion: This longitudinal study provides evidence that exercise counseling is most effective when the physician presents the counseling as a plan or prescription and when he or she follows up with the patient on it.

Simply telling sedentary patients that they need to exercise may not help them much. If the goal is to inspire action, a more effective approach would be to help them devise a plan for exercise and then inquire periodically about how it’s going. That premise was the basis for our study.

There’s good reason to get your patients moving

Physical inactivity is an independent risk factor for the most prevalent chronic diseases, including obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes. Physical activity at moderate or vigorous intensities reduces stress and depressive symptoms, controls high blood pressure and cholesterol levels, improves sleep, reduces or reverses weight gain, and prevents or controls chronic diseases.1 Based on these benefits, all physicians are encouraged to counsel sedentary patients to increase activity levels.2

National disease prevention objectives of Healthy People 2010 call for physicians to counsel at-risk patients on health behaviors such as physical activity and diet.3 Knowledge of patients’ families, environments, and communities makes primary care physicians uniquely suited to give effective advice,4 and physician counseling is known to positively influence patients’ health-related behavior.5-12

To date, findings on counseling effectiveness have been mixed. Unfortunately, previous controlled trials of primary care physicians counseling adult patients on physical activity have varied in quality and yielded mixed results.13 Therefore, in its Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, the US Preventive Services Task Force did not recommend for or against behavioral counseling in primary care settings to promote physical activity.14 The guidelines state that existing studies do not provide a clear picture of which counseling components are effective.13

A population-based study by Glasgow and colleagues suggests that follow-up support by the physician may be needed to change physical activity behavior. Generalizations were limited, though, by the cross-sectional study design and post hoc analysis.15

More research is also needed to determine which strategies help patients stay physically active, a necessary component to sustaining the health benefits of exercise.16 Unfortunately, few primary care physicians counsel overweight or inactive patients on the benefits of diet and physical activity, let alone assist them with long-term follow-through.7,8,11,16-18

Why we chose to study a rural population

Rural Americans are among the groups at highest risk for chronic diseases. On average they are older, less educated, and poorer than their urban counterparts.19,20 And rural residents walk 13% less than suburbanites.21 According to the Rural Healthy People 2010 survey, 5 of the top 10 health concerns are chronic conditions that can be prevented or ameliorated with adequate physical activity.22

Studies have shown that healthy adults believe their health care providers are a credible source of information, and that they are motivated to comply with physician advice.23 Nondisabled adults believe their physicians want them to be physically active.19 However, to our knowledge, no study has examined the effects of physician counseling on physical activity behavior for patients at increased risk for chronic diseases in rural areas.

Our objectives. The first objective of this study was to identify the prevalence of specific components of physician counseling in a tri-state sample of at-risk, rural adults using telephone survey data. A second objective was to measure the longitudinal relationship between physician counseling and physical activity.

Methods

The Saint Louis University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Study population and design

This study reports on baseline and 1-year follow-up telephone survey data collected as part of a larger 3-year intervention study in 12 rural communities from Missouri (6), Tennessee (4), and Arkansas (2). Project WOW (Walk the Ozarks to Wellness) aims to promote walking among overweight rural adults by integrating individual, interpersonal, and community-level interventions. Methods and details of the intervention are described in detail elsewhere.24 The target communities ranged in population from 766 to 12,993 adults, and in geographic area from 1.4 to 16.1 square miles.25

At baseline in the summer of 2003, we used a modified version of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) interview protocol26,27 and randomly dialed telephone numbers to recruit participants residing within a 2-mile radius of a walking trail. In all, 2470 English-speaking adults, ages 18 and older, completed the baseline survey (65.2% response rate).28 Sampling was proportionate to community size.

At follow-up in the summer of 2004, participants identified at baseline completed the same telephone survey used a year earlier. This time, 1531 participants completed the survey (62.0% response rate).28

Demographic variables included age, sex, education, race/ethnicity, and annual combined household income (TABLE 1). Overweight and obesity, based on self-reported height and weight, were defined by a body mass index (BMI) of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2 or greater, respectively.

TABLE 1

The population sample

| PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS | FOLLOW-UP SURVEY (N =1141) % |

|---|---|

| Female | 74.6 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 94.6 |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 9.7* |

| High school graduate | 30.8 |

| Some college | 23.9 |

| College graduate | 35.6 |

| Age | |

| 18-24 | 6.4* |

| 25-44 | 35.4 |

| 45-64 | 39.1 |

| 65+ | 19.1 |

| Annual household combined income (n=1102) | |

| < $25,000 31.7* | |

| ‡ $25,000 | 68.3 |

| Body mass index (n=1107) | |

| Normal (<25) | 43.7 |

| Overweight (25-29.9) | 31.5 |

| Obese (‡ 30) | 24.8 |

| Physician encounters/counseling | |

| Has doctor for regular care | 87.8* |

| In usual year, has seen doctor ≤1 time | 28.2* |

| Has been advised to exercise more | 35.1 |

| Doctor helped develop plan to exercise more | 33.8 |

| Doctor followed up on plan to exercise more | 46.3 |

| * Significant P value <.001 between responders and nonresponders at 1-year follow-up. | |

Measurement of dependent and independent variables

The survey instrument incorporated questions from the BRFSS, as well as questions developed by researchers from San Diego; Sumter County, South Carolina; and St. Louis.29-34 Psychometric properties of the questions and scales are reported elsewhere.35 The survey instrument contained 106 questions, including skip patterns; the average administration time was 34 minutes.

We assessed physician counseling about exercise with 5 questions from the survey (TABLE 2). These questions were modeled on the “4 As” counseling approach (Ask, Advise, Assist, and Arrange follow-up) recommended by the National Cancer Institute36 and used in a previous, similar BRFSS-based telephone survey.15 The questions were:

- Do you have a doctor whom you see for regular health care?

- In a usual year, how often do you see your doctor?

- Have you been advised within the last year by a doctor to exercise more?

- Has your doctor helped you to develop a plan to increase exercise?

- Has your doctor followed up with you at subsequent visits to see how you increased exercise?

We administered the questions at baseline and at follow-up. For our analyses, we used patient reports of physician counseling at 1-year follow-up, which covered all counseling received in the past 12 months.

We considered respondents to have met recommendations for physical activity if they had engaged in prescribed moderate or vigorous physical activities, or had walked for exercise 150 minutes a week.

Moderate physical activity was defined (according to the current CDC recommendations) as 30 cumulative minutes of moderate-intensity activity (brisk walking or jogging) at least 5 days per week.1

Vigorous physical activity was defined as 20 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity (running) at least 3 days per week.1

The sample was limited to participants who completed the baseline and follow-up surveys, and who reported at follow-up that they had no physical impairment that prevented walking (n=1141).

Statistical analysis

To evaluate how physician counseling would change a patient’s physical activity between baseline and 1-year follow-up, we used multivariate logistic regression analysis. In accordance with the questions asked in the survey, we defined 5 potential predictors of a patient’s decision to start exercising and keep exercising:

- Patient has seen a doctor for regular care.

- In a usual year, patient has seen a doctor once or less.

- Patient has been advised to exercise more.

- Doctor helped develop a plan to exercise more.

- Doctor followed up on plan to exercise more

For every patient who met physical activity recommendations at the 1-year follow-up, we performed regression analysis on each of these 5 measures, adjusting for baseline physical activity and potential confounders of age, education, and sex. This method allowed us to examine the independent effect of physician counseling on physical activity at 1-year follow-up.

The number of respondents analyzed differed according to the measure being examined. For example, we included all respondents in analyzing the effect of visit frequency and the effect of being advised to exercise more (n=1141). However, only those respondents who reported being advised to exercise more were included in the analyses of a physician helping to develop an exercise plan and physician follow-up in supporting exercise behavior (n=402).

To determine whether physician counseling was consistent across BMI categories and income (dichotomized at $25,000), we performed stratified analyses on the multilevel logistic regressions.

TABLE 2

What increased the likelihood of exercise? Regular medical care, a physician-assisted exercise plan, and physician follow-up (n=1141)

| PHYSICIAN ENCOUNTERS/COUNSELING | PATIENTS MEETING PHYSICAL ACTIVITY RECOMMENDATIONS | |

|---|---|---|

| aOR* | 95% CI | |

| 1. Do you have a doctor whom you see for regular health care? | ||

| Yes | 1.54 | 1.04-2.28 |

| No | Ref | |

| 2. In a usual year, how often do you see your doctor? | ||

| Once a year or less | 1.41 | 1.02-1.95 |

| Twice a year or more | Ref | |

| 3. Have you been advised within the last year by a doctor to exercise more? | ||

| Yes | 0.68 | 0.52-0.90 |

| No | Ref | |

| Of those advised to exercise more (n=402): 4. Has your doctor helped you to develop a plan to increase exercise? | ||

| Yes | 1.93 | 1.19-3.15 |

| No | Ref | |

| 5. Has your doctor followed up with you at subsequent visits to see how you increased exercise? | ||

| Yes | 2.84 | 1.78-4.53 |

| No | Ref | |

| aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference group. | ||

| *Adjusted for sex, age, educational attainment, and baseline physical activity. | ||

Results

The final cohort consisted of 1141 adults (TABLE 2). Those who did not respond to the follow-up survey were significantly more likely to be younger (P<.001), have less than a high school education (P<.001), and have an annual household combined income <$25,000 (P<.001). Those completing the follow-up survey were more likely to have a doctor for regular care (P<.001), although they saw their doctor, on average, significantly less per year than nonrespondents (P<.001).

Ninety percent of the cohort sample reported having a doctor whom they saw for regular care. Within the last year, 35% had been advised by their doctor to exercise more. Of those who had been so advised, 34% received help from their physician in developing a plan to increase exercise, and 46% were queried at subsequent visits as to how they were progressing with their exercise program.

After adjusting for age, sex, education, and baseline physical activity, we found that those who had a doctor for regular care were 54% more likely to be physically active than those who reported not having a doctor for regular care (aOR=1.54; 95% CI, 1.04-2.28). If the advising physician also developed a plan with the patient to increase exercise, there was nearly a 2-fold increase in physical activity compared with those who received only advice to exercise more (aOR=1.93; 95% CI, 1.19-3.15). If the physician followed up with the exercise plan at subsequent visits, the likelihood of physical activity increased further (aOR=2.84; 95% CI, 1.78-4.53) compared with those who did not receive follow-up from the physician.

Results of stratified analysis by BMI status are shown in TABLE 3. Individuals at normal weight were significantly more likely to be physically active if they had a physician for regular care (aOR=2.76; 95% CI, 1.49-5.13). Overweight adults (BMI 25-29.9 kg/m2) who had been advised by their physician to exercise more were significantly more likely to attain recommended levels of physical activity if their doctor helped develop an exercise plan than were those given more general advice about exercise (aOR=4.99; 95% CI, 1.69-14.73). Overweight individuals who received further counseling with follow-up inquiries were 5.64 times more likely to be physically active (95% CI, 2.10-15.17). A physician-developed exercise plan did not appreciably improve physical activity in obese adults (BMI ≥30 kg/m2); however, benefit in this group was demonstrated when physicians prescribed and followed up with the exercise plan (aOR=2.13; 95% CI, 1.10-4.12). Stratified analysis by income status provided no clear pattern (data not shown).

TABLE 3

What role does BMI play in patients achieving activity goals? (n=1107)

| PHYSICIAN ENCOUNTERS/COUNSELING | PATIENTS MEETING PHYSICAL ACTIVITY RECOMMENDATIONS* (aOR [95% CI]) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| NORMAL (BMI<25) | OVERWEIGHT (BMI 25-29.9) | OBESE (BMI ≥30) | |

| Has seen a doctor for regular care | 2.76 (1.49-5.13) | 1.08 (0.51-2.29) | 1.34 (0.62-2.91) |

| In a usual year, has seen a doctor ≤1 time | 1.98 (1.13-3.47) | 0.95 (0.54-1.68) | 0.95 (0.47-1.92) |

| Has been advised to exercise more | 1.02 (0.56-1.85) | 0.75 (0.46-1.25) | 0.77 (0.46-1.31) |

| Doctor helped develop a plan to exercise more | 0.69 (0.22-2.18) | 4.99 (1.69-14.73) | 1.76 (0.87-3.56) |

| Doctor followed up on plan to exercise more | 2.59 (0.80-8.36) | 5.64 (2.10-15.17) | 2.13 (1.10-4.12) |

| aOR, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, body-mass index; CI, confidence interval. | |||

| *Adjusted for sex, age, educational attainment, and baseline physical activity. | |||

Discussion

Findings from our analyses support the need for more detailed and more frequent exercise counseling (including follow-up) by rural primary care physicians. In our study, physicians’ counsel was most effective when presented as a plan or prescription that was followed up with periodic inquiries. Patients’ initiation and maintenance of physical activity were significantly associated with physicians’ follow-up of exercise plans. Those who were merely “advised” to exercise more were less likely to meet physical activity recommendations. This illustrates the importance of detailed physician counseling over simple advice to exercise more.

Over 80% of normal-weight individuals, who comprised more than 40% of the sample, reported that their physician had not suggested they exercise more. There are many possible explanations for these reports. Rural populations are relatively isolated and slow to adopt changes. Thus patients may be unaware of new recommendations for physical activity and their significant benefit for disease prevention, and therefore unlikely to discuss such matters with their physician. Physicians also may perceive normal-weight individuals as healthy regardless of their actual health behaviors. On the other hand, 1 study showed that patients with disease risk factors (eg, high cholesterol, elevated BMI) were more likely to be counseled on preventive health behaviors.37

With overweight patients, who are at increased risk of developing chronic diseases, physician counseling strengthened their resolve significantly. Overweight individuals who received directives from their physician (a plan to increase exercise and subsequent follow-up) were 5½ times more likely to be physically active than those who received less counseling.

Obese patients did not receive counseling as often as overweight patients, or benefit from it as much when given, perhaps due to the presence of comorbidities. However, many studies show that regardless of BMI status, physical activity reduces all-cause mortality.38-41

Interestingly, our results showed that seeing a doctor less than once a year was associated with increases in physical activity. Patients who see their physician once a year may be going for annual wellness exams, providing more opportunity to discuss health behavior.

Overall, patients are counseled less often/thoroughly than needed. Our findings agree with those of a previous statewide study that used Missouri BRFSS data to assess the extent to which overweight or physically inactive people received advice from their physicians concerning these risk factors.42 Although most Missouri residents who were overweight or inactive reported seeing their physician within the past year, less than half said their doctors advised them to alter their risk behavior(s).42 Our findings are also consistent with a recent nationwide study by Ma and colleagues that focused on adults with obesity, diabetes, or other related conditions.43 Participants from across the United States reported receiving counseling for physical activity in <30% of visits to private physician offices and hospital outpatient departments.43

Our study was unique in that it examined a tri-state sample of the nation’s rural population for both evidence and effectiveness of physician counseling. It is one of very few studies using a longitudinal design, strengthening the associations found. Causality is limited, however, due to the multifaceted design of the intervention program from which the data were obtained. Future research should evaluate varying degrees of physician counseling and other indirect measures of its impact.

Limitations of the study

Our observational cohort design and the large, randomly selected sample resulted in fewer limitations than were seen with previous similar studies. However, our study had several limitations.

- Recall bias may be present. We assessed counseling with patient memory alone; we made no attempts to interview physicians or audit charts.

- Self-reported height and weight data tend to underestimate the prevalence of obesity.44,45 Resultant misclassification of overweight subjects as being at normal weight could have skewed the stratified analysis.

- The external validity of the physician-counseling questions we used has not been formally confirmed. Given the demographics of the analytic sample (ie, mostly female, white, low income), it would be appropriate to generalize our findings only to similar, rural populations.

Barriers to counseling, and means of removing them

Primary care physicians—rural or urban—are no doubt aware of the health risks associated with physical inactivity. However, the barriers physicians face in counseling at-risk patients overwhelm most efforts. These barriers include lack of time, inadequate provider counseling skills and training, perceived ineffectiveness and nonadherence, patient comorbidities, and lack of organizational support and reimbursement.46-48

Intervention programs and tools have been developed to help health care providers overcome time, skill, and training barriers. These programs, available even to rural providers, have proven effective.49,50 (Go to www.paceproject.org/Home.html and click on “Projects” to learn about the PACE program.) However, application of such skills and tools may be more successful if training is incorporated into medical school curricula and residency training programs rather than through CME endeavors.49 This would require medical institutions and organizations to prioritize the direct link between healthy lifestyle behaviors and disease prevention and the vital role physicians play in underscoring this link.

Finally, health care policy makers and systems must be persuaded to address the lack of organizational support and reimbursement that prevents physicians from counseling at-risk patients on unhealthy lifestyle behaviors. Responsible payers and providers should aggressively explore low-cost ways to promote physical activity and weight loss in primary care settings, to stem the tide of obesity-related chronic diseases. At the local level, physicians can team up to support policies that may enhance preventive counseling efforts2—increasing access to places for activity, encouraging physical activity programming in communities, schools, and organizations, and physical environment enhancements such as safe sidewalks, adequate lighting, and improved zoning.44,51,44,52

Acknowledgments

We thank the communities that are participating in the ongoing intervention study. For their assistance in data collection, we thank the Department of Health Management and Informatics, Behavioral Risk Research Unit at the University of Missouri, Columbia.

Funding/support

This study was funded through the National Institutes of Health grant NIDDK #5 R18 DK061706 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention contract U48/CCU710806 (Centers for Research and Demonstration of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention). Human subjects approval was obtained from the Saint Louis University Institutional Review Board.

Correspondence

Sarah L. Lovegreen, MPH, Prevention Research Center and Department of Community Health, Saint Louis University School of Public Health, 3545 Lafayette Ave., Salus Center, Suite 300, St. Louis, MO 63146; slove green@oasisnet.org.

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 1996.

2. Chakravarthy MV, Joyner MJ, Booth FW. An obligation for primary care physicians to prescribe physical activity to sedentary patients to reduce the risk of chronic health conditions. Mayo Clin Proc 2002;77:165-173.

3. US. Department of Health and Human Services. Health People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, November 2000.

4. Iverson D, Fielding J, Crow R, Christenson G. The promotion of physical activity in the U.S. population: the status of programs in medical, worksite, community, and school settings. Public Health Rep 1985;100:212-224.

5. Kreuter MW, Chheda SG, Bull FC. How does physician advice influence patient behavior? Evidence for a priming effect. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:426-433.

6. The Writing Group for the Activity Counseling Trial Research Group. Effects of physical activity counseling in primary care: the Activity Counseling Trial: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;286:677-687.

7. Galuska DA, Will JC, Serdula MK, Ford ES. Are health care professionals advising obese patients to lose weight? JAMA 1999;282:1576-1578.

8. Calfas KJ, Long BJ, Sallis JF, Wooten WJ, Pratt M, Patrick K. A controlled trial of physician counseling to promote the adoption of physical activity. Prev Med 1996;25:225-233.

9. Sallis JF, Patrick K, Calfas KJ. Counseling patients/clients about physical activity and nutrition. Weight Control Digest 1999;9:843, 846-850.

10. Calfas KJ, Zabinski MF, Rupp J. Practical nutrition assessment in primary care settings: a review. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:289-299.

11. Marcus BH, Goldstein MG, Jette A, et al. Training physicians to conduct physical activity counseling. Prev Med 1997;26:382-388.

12. Godin R, Shephard RJ. An evaluation of the potential role of the physician in influencing community exercise behavior. Am J Health Prom 1990;4:255-259.

13. Eden KB, Orleans CT, Mulrow CD, Pender NJ, Teutsch SM. Does counseling by clinicians improve physical activity? A summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:208-215.

14. US. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral Counseling in Primary Care to Promote Physical Activity: Recommendations and Rationale. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; July 2002. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/physactivity/physactrr.htm. Accessed April 24, 2008.

15. Glasgow RE, Eakin EG, Fisher EB, Bacak SJ, Brownson RC. Physician advice and support for physical activity: results from a national survey. Am J Prev Med 2001;21:189-196.

16. Marcus BH, Dubbert PM, Forsyth LH, et al. Physical activity behavior change: issues in adoption and maintenance. Health Psychol 2000;19(1 suppl):32-41.

17. Stafford RS, Farhat JH, Misra B, Schoenfeld DA. National patterns of physician activities related to obesity management. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:631-638.

18. Potter MB, Vu JD, Croughan-Minihane M. Weight management what patients want from their primary care physician. J Fam Pract 2001;50:513-518.

19. Sobal J, Troiana RP, Frongillo EA, Jr. Rural-urban differences in obesity. Rural Sociol 1996;2:289-305.

20. Miller MK, Stokes CS, Clifford WB. A comparison of the rural-urban mortality differential for deaths from all causes, cardiovascular disease and cancer. J Rural Health 1987;3(2):23-34.

21. Eyler AA, Brownson RC, Bacak SJ, Housemann RA. The epidemiology of walking for physical activity in the United States. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:1529-36.

22. Gamm L, Hutchison L, Bellamy G, et al. Rural healthy people 2010: identifying rural health priorities and models for practice. J Rural Health 2002;18(1):9-14.

23. Schappert SM. National ambulatory medical care survey: 1991 Summary. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 1993.

24. Brownson R, Hagood L, Lovegreen S, et al. A multilevel, ecological approach to promoting walking in rural communities. Prev Med 2005;41:837-842.

25. US. Census Bureau. Census 2000. Available at: http://www.census.gov/main/www/cen2000.html. Accessed November 2004.

26. Gentry EM, Kalsbeek WD, Hogelin GC, et al. The behavioral risk factor surveys: II. Design, methods, and estimates from combined state data. Am J Prev Med 1985;1(6):9-14.

27. Remington PL, Smith MY, Williamson DF, Anda RF, Gentry EM, Hogelin GC. Design, characteristics, and usefulness of state-based behavioral risk factor surveillance: 1981-87. Public Health Rep 1988;103:366-375.

28. Council of American Survey Research Organizations (CASRO) Task Force on Completion Rates. On the Definitions of Response Rates. Special Report. New York, NY: Council of American Survey Organizations; 1982.

29. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/. Accessed November 2004.

30. Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Black JB, Chen D. Neighborhood-based differences in physical activity: an environment scale evaluation. Am J Public Health 2003;93:1552-1558.

31. Eyler AA, Brownson RC, Donatelle RJ, King AC, Brown D, Sallis JF. Physical activity social support and middle- and older-aged minority women: results from a US survey. Soc Sci Med 1999;49:781-789.

32. King AC, Castro C, Wilcox S, Eyler AA, Sallis JF, Brownson RC. Personal and environmental factors associated with physical inactivity among different racial-ethnic groups of US middle- aged and older-aged women. Health Psychol 2000;19:354-364.

33. Ainsworth BE, Bassett DR, Jr, Strath SJ, et al. Comparison of three methods for measuring the time spent in physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32(9 suppl):S457-S464.

34. Brownson RC, Baker EA, Housemann RA, Brennan LK, Bacak SJ. Environmental and policy determinants of physical activity in the United States. Am J Public Health 2001;91:1995-2003.

35. Brownson RC, Chang JJ, Eyler AA. Measuring the environment for friendliness toward physical activity: a comparison of the reliability of three questionnaires. Am J Public Health 2004;94:473-483.

36. Manely M, Epps R, Husten C, Glynn T, Shopland D. Clinical interventions in tobacco control: a National Cancer Institute training program for physicians. JAMA 1991;266:3172-3173.

37. Kreuter MW, Scharff DP, Brennan LK, Lukwago SN. Physician recommendations for diet and physical activity: which patients get advised to change? Prev Med 1997;26:825-833.

38. Hu FB, Willett WC, Li T, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Manson JE. Adiposity as compared with physical activity in predicting mortality among women. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2694-2703.

39. Lee CD, Blair SN, Jackson AS. Cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, and all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Am J Clin Nut 1999;69:373-380.

40. Stevens J, Cai J, Evenson KR, Thomas R. Fitness and fatness as predictors of mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular disease in men and women in the Lipid Research Clinics Study. Am J Epidemiol 2002;156:832-841.

41. Wei M, Kampert JB, Barlow CE, et al. Relationship between low cardiorespiratory fitness and mortality in normal-weight, overweight and obese men. JAMA 1999;282:1547-1553.

42. Friedman C, Brownson RC, Peterson DE, Wilkerson JC. Physician advice to reduce chronic disease risk factors. Am J Prev Med 1994;10:367-371.

43. Ma J, Urizar GG, Alehegn T, Stafford R. Diet and physical activity counseling during ambulatory care visits in the United States. Prev Med 2004;39:815-822.

44. Palta M, Prineas RJ, Berman R, Hannan P. Comparison of self-reported and measured height and weight. Am J Epidemiol 1982;115:223-230.

45. Kuskowska-Wolk A, Karlsson P, Stolt M, Rossner S. The predictive validity of body mass index based on self-reported weight and height. Int J Obes 1989;13:441-453.

46. Kushner RF. Barriers to providing nutritional counseling by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Prev Med 1995;24:546-552.

47. Rogers LQ, Bailey JE, Gutin B, et al. Teaching resi-dent physicians to provide physician counseling: a needs assessment. Acad Med 2002;77:841-844.

48. Hiss RG. Barriers to care in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Michigan experience. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:146-148.

49. Calfas KJ, Sallis JF, Zabinski MF, et al. Preliminary evaluation of a multi-component program for nutrition and physical activity change in primary care: PACE+ for adults. Prev Med 2002;34:153-161.

50. Sallis JF, Patrick K, Calfas KJ, et al. A multi-media behavior change program for nutrition and physical activity in primary care: PACE+ for adults. Homeostasis 1999;39:196-202.

51. Health GW, Brownson RC, Kruger J, et al. The effectiveness of urban design and land use and transport policies and practices to increase physical activity: a systematic review. J Phys Act Health 2006;3(suppl 1):555-576.

52. Sallis JF, Glanz K. The role of built environment in physical activity, eating and obesity in childhood. Future Child 2006 Spring;16(1):89-108.

- To help overweight patients and those with a sedentary lifestyle to adopt and stick with an exercise regimen, develop a detailed and realistic plan with their help, and follow up with them periodically to see how they’re doing.

Purpose: Exercise counseling by primary care physicians has been shown to improve physical activity in patients. However, the prevalence and effectiveness of physician counseling is unknown in rural populations that are at increased risk for chronic diseases.

Methods: Using a population-based telephone survey at baseline and again at 1-year follow-up, we assessed physical activity behavior among 1141 adults (75% female, 95% white) living within 12 rural communities of Missouri, Tennessee, and Arkansas. We tested the association between physician counseling and patients meeting current physical activity recommendations using logistic regression analysis controlling for demographic variables.

Results: Participants who saw a doctor for regular care were 54% more likely to be physically active (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]=1.54; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04-2.28). Overweight adults (body mass index [BMI]=25-29.9 kg/m2) who had been advised by their physician to exercise more were nearly 5 times more likely to meet physical activity recommendations if their doctor helped develop an exercise plan (aOR=4.99; 95% CI, 1.69-14.73).

Overweight individuals who received additional follow-up with the exercise plan from their doctor had a 5½-fold increase in likelihood of meeting physical activity recommendations (P<.05).

In the overall sample, patients were significantly more likely to initiate (P=.01) and maintain (P=.002) physical activity when the physician prescribed and followed up on an exercise plan.

Conclusion: This longitudinal study provides evidence that exercise counseling is most effective when the physician presents the counseling as a plan or prescription and when he or she follows up with the patient on it.

Simply telling sedentary patients that they need to exercise may not help them much. If the goal is to inspire action, a more effective approach would be to help them devise a plan for exercise and then inquire periodically about how it’s going. That premise was the basis for our study.

There’s good reason to get your patients moving

Physical inactivity is an independent risk factor for the most prevalent chronic diseases, including obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes. Physical activity at moderate or vigorous intensities reduces stress and depressive symptoms, controls high blood pressure and cholesterol levels, improves sleep, reduces or reverses weight gain, and prevents or controls chronic diseases.1 Based on these benefits, all physicians are encouraged to counsel sedentary patients to increase activity levels.2

National disease prevention objectives of Healthy People 2010 call for physicians to counsel at-risk patients on health behaviors such as physical activity and diet.3 Knowledge of patients’ families, environments, and communities makes primary care physicians uniquely suited to give effective advice,4 and physician counseling is known to positively influence patients’ health-related behavior.5-12

To date, findings on counseling effectiveness have been mixed. Unfortunately, previous controlled trials of primary care physicians counseling adult patients on physical activity have varied in quality and yielded mixed results.13 Therefore, in its Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, the US Preventive Services Task Force did not recommend for or against behavioral counseling in primary care settings to promote physical activity.14 The guidelines state that existing studies do not provide a clear picture of which counseling components are effective.13

A population-based study by Glasgow and colleagues suggests that follow-up support by the physician may be needed to change physical activity behavior. Generalizations were limited, though, by the cross-sectional study design and post hoc analysis.15

More research is also needed to determine which strategies help patients stay physically active, a necessary component to sustaining the health benefits of exercise.16 Unfortunately, few primary care physicians counsel overweight or inactive patients on the benefits of diet and physical activity, let alone assist them with long-term follow-through.7,8,11,16-18

Why we chose to study a rural population

Rural Americans are among the groups at highest risk for chronic diseases. On average they are older, less educated, and poorer than their urban counterparts.19,20 And rural residents walk 13% less than suburbanites.21 According to the Rural Healthy People 2010 survey, 5 of the top 10 health concerns are chronic conditions that can be prevented or ameliorated with adequate physical activity.22

Studies have shown that healthy adults believe their health care providers are a credible source of information, and that they are motivated to comply with physician advice.23 Nondisabled adults believe their physicians want them to be physically active.19 However, to our knowledge, no study has examined the effects of physician counseling on physical activity behavior for patients at increased risk for chronic diseases in rural areas.

Our objectives. The first objective of this study was to identify the prevalence of specific components of physician counseling in a tri-state sample of at-risk, rural adults using telephone survey data. A second objective was to measure the longitudinal relationship between physician counseling and physical activity.

Methods

The Saint Louis University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Study population and design

This study reports on baseline and 1-year follow-up telephone survey data collected as part of a larger 3-year intervention study in 12 rural communities from Missouri (6), Tennessee (4), and Arkansas (2). Project WOW (Walk the Ozarks to Wellness) aims to promote walking among overweight rural adults by integrating individual, interpersonal, and community-level interventions. Methods and details of the intervention are described in detail elsewhere.24 The target communities ranged in population from 766 to 12,993 adults, and in geographic area from 1.4 to 16.1 square miles.25

At baseline in the summer of 2003, we used a modified version of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) interview protocol26,27 and randomly dialed telephone numbers to recruit participants residing within a 2-mile radius of a walking trail. In all, 2470 English-speaking adults, ages 18 and older, completed the baseline survey (65.2% response rate).28 Sampling was proportionate to community size.

At follow-up in the summer of 2004, participants identified at baseline completed the same telephone survey used a year earlier. This time, 1531 participants completed the survey (62.0% response rate).28

Demographic variables included age, sex, education, race/ethnicity, and annual combined household income (TABLE 1). Overweight and obesity, based on self-reported height and weight, were defined by a body mass index (BMI) of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2 or greater, respectively.

TABLE 1

The population sample

| PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS | FOLLOW-UP SURVEY (N =1141) % |

|---|---|

| Female | 74.6 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 94.6 |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 9.7* |

| High school graduate | 30.8 |

| Some college | 23.9 |

| College graduate | 35.6 |

| Age | |

| 18-24 | 6.4* |

| 25-44 | 35.4 |

| 45-64 | 39.1 |

| 65+ | 19.1 |

| Annual household combined income (n=1102) | |

| < $25,000 31.7* | |

| ‡ $25,000 | 68.3 |

| Body mass index (n=1107) | |

| Normal (<25) | 43.7 |

| Overweight (25-29.9) | 31.5 |

| Obese (‡ 30) | 24.8 |

| Physician encounters/counseling | |

| Has doctor for regular care | 87.8* |

| In usual year, has seen doctor ≤1 time | 28.2* |

| Has been advised to exercise more | 35.1 |

| Doctor helped develop plan to exercise more | 33.8 |

| Doctor followed up on plan to exercise more | 46.3 |

| * Significant P value <.001 between responders and nonresponders at 1-year follow-up. | |

Measurement of dependent and independent variables

The survey instrument incorporated questions from the BRFSS, as well as questions developed by researchers from San Diego; Sumter County, South Carolina; and St. Louis.29-34 Psychometric properties of the questions and scales are reported elsewhere.35 The survey instrument contained 106 questions, including skip patterns; the average administration time was 34 minutes.

We assessed physician counseling about exercise with 5 questions from the survey (TABLE 2). These questions were modeled on the “4 As” counseling approach (Ask, Advise, Assist, and Arrange follow-up) recommended by the National Cancer Institute36 and used in a previous, similar BRFSS-based telephone survey.15 The questions were:

- Do you have a doctor whom you see for regular health care?

- In a usual year, how often do you see your doctor?

- Have you been advised within the last year by a doctor to exercise more?

- Has your doctor helped you to develop a plan to increase exercise?

- Has your doctor followed up with you at subsequent visits to see how you increased exercise?

We administered the questions at baseline and at follow-up. For our analyses, we used patient reports of physician counseling at 1-year follow-up, which covered all counseling received in the past 12 months.

We considered respondents to have met recommendations for physical activity if they had engaged in prescribed moderate or vigorous physical activities, or had walked for exercise 150 minutes a week.

Moderate physical activity was defined (according to the current CDC recommendations) as 30 cumulative minutes of moderate-intensity activity (brisk walking or jogging) at least 5 days per week.1

Vigorous physical activity was defined as 20 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity (running) at least 3 days per week.1

The sample was limited to participants who completed the baseline and follow-up surveys, and who reported at follow-up that they had no physical impairment that prevented walking (n=1141).

Statistical analysis

To evaluate how physician counseling would change a patient’s physical activity between baseline and 1-year follow-up, we used multivariate logistic regression analysis. In accordance with the questions asked in the survey, we defined 5 potential predictors of a patient’s decision to start exercising and keep exercising:

- Patient has seen a doctor for regular care.

- In a usual year, patient has seen a doctor once or less.

- Patient has been advised to exercise more.

- Doctor helped develop a plan to exercise more.

- Doctor followed up on plan to exercise more

For every patient who met physical activity recommendations at the 1-year follow-up, we performed regression analysis on each of these 5 measures, adjusting for baseline physical activity and potential confounders of age, education, and sex. This method allowed us to examine the independent effect of physician counseling on physical activity at 1-year follow-up.

The number of respondents analyzed differed according to the measure being examined. For example, we included all respondents in analyzing the effect of visit frequency and the effect of being advised to exercise more (n=1141). However, only those respondents who reported being advised to exercise more were included in the analyses of a physician helping to develop an exercise plan and physician follow-up in supporting exercise behavior (n=402).

To determine whether physician counseling was consistent across BMI categories and income (dichotomized at $25,000), we performed stratified analyses on the multilevel logistic regressions.

TABLE 2

What increased the likelihood of exercise? Regular medical care, a physician-assisted exercise plan, and physician follow-up (n=1141)

| PHYSICIAN ENCOUNTERS/COUNSELING | PATIENTS MEETING PHYSICAL ACTIVITY RECOMMENDATIONS | |

|---|---|---|

| aOR* | 95% CI | |

| 1. Do you have a doctor whom you see for regular health care? | ||

| Yes | 1.54 | 1.04-2.28 |

| No | Ref | |

| 2. In a usual year, how often do you see your doctor? | ||

| Once a year or less | 1.41 | 1.02-1.95 |

| Twice a year or more | Ref | |

| 3. Have you been advised within the last year by a doctor to exercise more? | ||

| Yes | 0.68 | 0.52-0.90 |

| No | Ref | |

| Of those advised to exercise more (n=402): 4. Has your doctor helped you to develop a plan to increase exercise? | ||

| Yes | 1.93 | 1.19-3.15 |

| No | Ref | |

| 5. Has your doctor followed up with you at subsequent visits to see how you increased exercise? | ||

| Yes | 2.84 | 1.78-4.53 |

| No | Ref | |

| aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference group. | ||

| *Adjusted for sex, age, educational attainment, and baseline physical activity. | ||

Results

The final cohort consisted of 1141 adults (TABLE 2). Those who did not respond to the follow-up survey were significantly more likely to be younger (P<.001), have less than a high school education (P<.001), and have an annual household combined income <$25,000 (P<.001). Those completing the follow-up survey were more likely to have a doctor for regular care (P<.001), although they saw their doctor, on average, significantly less per year than nonrespondents (P<.001).

Ninety percent of the cohort sample reported having a doctor whom they saw for regular care. Within the last year, 35% had been advised by their doctor to exercise more. Of those who had been so advised, 34% received help from their physician in developing a plan to increase exercise, and 46% were queried at subsequent visits as to how they were progressing with their exercise program.

After adjusting for age, sex, education, and baseline physical activity, we found that those who had a doctor for regular care were 54% more likely to be physically active than those who reported not having a doctor for regular care (aOR=1.54; 95% CI, 1.04-2.28). If the advising physician also developed a plan with the patient to increase exercise, there was nearly a 2-fold increase in physical activity compared with those who received only advice to exercise more (aOR=1.93; 95% CI, 1.19-3.15). If the physician followed up with the exercise plan at subsequent visits, the likelihood of physical activity increased further (aOR=2.84; 95% CI, 1.78-4.53) compared with those who did not receive follow-up from the physician.

Results of stratified analysis by BMI status are shown in TABLE 3. Individuals at normal weight were significantly more likely to be physically active if they had a physician for regular care (aOR=2.76; 95% CI, 1.49-5.13). Overweight adults (BMI 25-29.9 kg/m2) who had been advised by their physician to exercise more were significantly more likely to attain recommended levels of physical activity if their doctor helped develop an exercise plan than were those given more general advice about exercise (aOR=4.99; 95% CI, 1.69-14.73). Overweight individuals who received further counseling with follow-up inquiries were 5.64 times more likely to be physically active (95% CI, 2.10-15.17). A physician-developed exercise plan did not appreciably improve physical activity in obese adults (BMI ≥30 kg/m2); however, benefit in this group was demonstrated when physicians prescribed and followed up with the exercise plan (aOR=2.13; 95% CI, 1.10-4.12). Stratified analysis by income status provided no clear pattern (data not shown).

TABLE 3

What role does BMI play in patients achieving activity goals? (n=1107)

| PHYSICIAN ENCOUNTERS/COUNSELING | PATIENTS MEETING PHYSICAL ACTIVITY RECOMMENDATIONS* (aOR [95% CI]) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| NORMAL (BMI<25) | OVERWEIGHT (BMI 25-29.9) | OBESE (BMI ≥30) | |

| Has seen a doctor for regular care | 2.76 (1.49-5.13) | 1.08 (0.51-2.29) | 1.34 (0.62-2.91) |

| In a usual year, has seen a doctor ≤1 time | 1.98 (1.13-3.47) | 0.95 (0.54-1.68) | 0.95 (0.47-1.92) |

| Has been advised to exercise more | 1.02 (0.56-1.85) | 0.75 (0.46-1.25) | 0.77 (0.46-1.31) |

| Doctor helped develop a plan to exercise more | 0.69 (0.22-2.18) | 4.99 (1.69-14.73) | 1.76 (0.87-3.56) |

| Doctor followed up on plan to exercise more | 2.59 (0.80-8.36) | 5.64 (2.10-15.17) | 2.13 (1.10-4.12) |

| aOR, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, body-mass index; CI, confidence interval. | |||

| *Adjusted for sex, age, educational attainment, and baseline physical activity. | |||

Discussion

Findings from our analyses support the need for more detailed and more frequent exercise counseling (including follow-up) by rural primary care physicians. In our study, physicians’ counsel was most effective when presented as a plan or prescription that was followed up with periodic inquiries. Patients’ initiation and maintenance of physical activity were significantly associated with physicians’ follow-up of exercise plans. Those who were merely “advised” to exercise more were less likely to meet physical activity recommendations. This illustrates the importance of detailed physician counseling over simple advice to exercise more.

Over 80% of normal-weight individuals, who comprised more than 40% of the sample, reported that their physician had not suggested they exercise more. There are many possible explanations for these reports. Rural populations are relatively isolated and slow to adopt changes. Thus patients may be unaware of new recommendations for physical activity and their significant benefit for disease prevention, and therefore unlikely to discuss such matters with their physician. Physicians also may perceive normal-weight individuals as healthy regardless of their actual health behaviors. On the other hand, 1 study showed that patients with disease risk factors (eg, high cholesterol, elevated BMI) were more likely to be counseled on preventive health behaviors.37

With overweight patients, who are at increased risk of developing chronic diseases, physician counseling strengthened their resolve significantly. Overweight individuals who received directives from their physician (a plan to increase exercise and subsequent follow-up) were 5½ times more likely to be physically active than those who received less counseling.

Obese patients did not receive counseling as often as overweight patients, or benefit from it as much when given, perhaps due to the presence of comorbidities. However, many studies show that regardless of BMI status, physical activity reduces all-cause mortality.38-41

Interestingly, our results showed that seeing a doctor less than once a year was associated with increases in physical activity. Patients who see their physician once a year may be going for annual wellness exams, providing more opportunity to discuss health behavior.

Overall, patients are counseled less often/thoroughly than needed. Our findings agree with those of a previous statewide study that used Missouri BRFSS data to assess the extent to which overweight or physically inactive people received advice from their physicians concerning these risk factors.42 Although most Missouri residents who were overweight or inactive reported seeing their physician within the past year, less than half said their doctors advised them to alter their risk behavior(s).42 Our findings are also consistent with a recent nationwide study by Ma and colleagues that focused on adults with obesity, diabetes, or other related conditions.43 Participants from across the United States reported receiving counseling for physical activity in <30% of visits to private physician offices and hospital outpatient departments.43

Our study was unique in that it examined a tri-state sample of the nation’s rural population for both evidence and effectiveness of physician counseling. It is one of very few studies using a longitudinal design, strengthening the associations found. Causality is limited, however, due to the multifaceted design of the intervention program from which the data were obtained. Future research should evaluate varying degrees of physician counseling and other indirect measures of its impact.

Limitations of the study

Our observational cohort design and the large, randomly selected sample resulted in fewer limitations than were seen with previous similar studies. However, our study had several limitations.

- Recall bias may be present. We assessed counseling with patient memory alone; we made no attempts to interview physicians or audit charts.

- Self-reported height and weight data tend to underestimate the prevalence of obesity.44,45 Resultant misclassification of overweight subjects as being at normal weight could have skewed the stratified analysis.

- The external validity of the physician-counseling questions we used has not been formally confirmed. Given the demographics of the analytic sample (ie, mostly female, white, low income), it would be appropriate to generalize our findings only to similar, rural populations.

Barriers to counseling, and means of removing them

Primary care physicians—rural or urban—are no doubt aware of the health risks associated with physical inactivity. However, the barriers physicians face in counseling at-risk patients overwhelm most efforts. These barriers include lack of time, inadequate provider counseling skills and training, perceived ineffectiveness and nonadherence, patient comorbidities, and lack of organizational support and reimbursement.46-48

Intervention programs and tools have been developed to help health care providers overcome time, skill, and training barriers. These programs, available even to rural providers, have proven effective.49,50 (Go to www.paceproject.org/Home.html and click on “Projects” to learn about the PACE program.) However, application of such skills and tools may be more successful if training is incorporated into medical school curricula and residency training programs rather than through CME endeavors.49 This would require medical institutions and organizations to prioritize the direct link between healthy lifestyle behaviors and disease prevention and the vital role physicians play in underscoring this link.

Finally, health care policy makers and systems must be persuaded to address the lack of organizational support and reimbursement that prevents physicians from counseling at-risk patients on unhealthy lifestyle behaviors. Responsible payers and providers should aggressively explore low-cost ways to promote physical activity and weight loss in primary care settings, to stem the tide of obesity-related chronic diseases. At the local level, physicians can team up to support policies that may enhance preventive counseling efforts2—increasing access to places for activity, encouraging physical activity programming in communities, schools, and organizations, and physical environment enhancements such as safe sidewalks, adequate lighting, and improved zoning.44,51,44,52

Acknowledgments

We thank the communities that are participating in the ongoing intervention study. For their assistance in data collection, we thank the Department of Health Management and Informatics, Behavioral Risk Research Unit at the University of Missouri, Columbia.

Funding/support

This study was funded through the National Institutes of Health grant NIDDK #5 R18 DK061706 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention contract U48/CCU710806 (Centers for Research and Demonstration of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention). Human subjects approval was obtained from the Saint Louis University Institutional Review Board.

Correspondence

Sarah L. Lovegreen, MPH, Prevention Research Center and Department of Community Health, Saint Louis University School of Public Health, 3545 Lafayette Ave., Salus Center, Suite 300, St. Louis, MO 63146; slove green@oasisnet.org.

- To help overweight patients and those with a sedentary lifestyle to adopt and stick with an exercise regimen, develop a detailed and realistic plan with their help, and follow up with them periodically to see how they’re doing.

Purpose: Exercise counseling by primary care physicians has been shown to improve physical activity in patients. However, the prevalence and effectiveness of physician counseling is unknown in rural populations that are at increased risk for chronic diseases.

Methods: Using a population-based telephone survey at baseline and again at 1-year follow-up, we assessed physical activity behavior among 1141 adults (75% female, 95% white) living within 12 rural communities of Missouri, Tennessee, and Arkansas. We tested the association between physician counseling and patients meeting current physical activity recommendations using logistic regression analysis controlling for demographic variables.

Results: Participants who saw a doctor for regular care were 54% more likely to be physically active (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]=1.54; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04-2.28). Overweight adults (body mass index [BMI]=25-29.9 kg/m2) who had been advised by their physician to exercise more were nearly 5 times more likely to meet physical activity recommendations if their doctor helped develop an exercise plan (aOR=4.99; 95% CI, 1.69-14.73).

Overweight individuals who received additional follow-up with the exercise plan from their doctor had a 5½-fold increase in likelihood of meeting physical activity recommendations (P<.05).

In the overall sample, patients were significantly more likely to initiate (P=.01) and maintain (P=.002) physical activity when the physician prescribed and followed up on an exercise plan.

Conclusion: This longitudinal study provides evidence that exercise counseling is most effective when the physician presents the counseling as a plan or prescription and when he or she follows up with the patient on it.

Simply telling sedentary patients that they need to exercise may not help them much. If the goal is to inspire action, a more effective approach would be to help them devise a plan for exercise and then inquire periodically about how it’s going. That premise was the basis for our study.

There’s good reason to get your patients moving

Physical inactivity is an independent risk factor for the most prevalent chronic diseases, including obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes. Physical activity at moderate or vigorous intensities reduces stress and depressive symptoms, controls high blood pressure and cholesterol levels, improves sleep, reduces or reverses weight gain, and prevents or controls chronic diseases.1 Based on these benefits, all physicians are encouraged to counsel sedentary patients to increase activity levels.2