User login

Comparison of Dermatologist Ratings on Health Care–Specific and General Consumer Websites

Health care–specific (eg, Healthgrades, Zocdoc, Vitals, WebMD) and general consumer websites (eg, Google, Yelp) are popular platforms for patients to find physicians, schedule appointments, and review physician experiences. Patients find ratings on these websites more trustworthy than standardized surveys distributed by hospitals, but many physicians do not trust the reviews on these sites. For example, in a survey of both physicians (n=828) and patients (n=494), 36% of physicians trusted online reviews compared to 57% of patients.1 The objective of this study was to determine if health care–specific or general consumer websites more accurately reflect overall patient sentiment. This knowledge can help physicians who are seeking to improve the patient experience understand which websites have more accurate and trustworthy reviews.

Methods

A list of dermatologists from the top 10 most and least dermatologist–dense areas in the United States was compiled to examine different physician populations.2 Equal numbers of male and female dermatologists were randomly selected from the most dense areas. All physicians were included from the least dense areas because of limited sample size. Ratings were collected from websites most likely to appear on the first page of a Google search for a physician name, as these are most likely to be seen by patients. Descriptive statistics were generated to describe the study population; mean and median physician rating (using a scale of 1–5); SD; and minimum, maximum, and interquartile ranges. Spearman correlation coefficients were generated to examine the strength of association between ratings from website pairs. P<.05 was considered statistically significant, with analyses performed in R (3.6.2) for Windows (the R Foundation).

Results

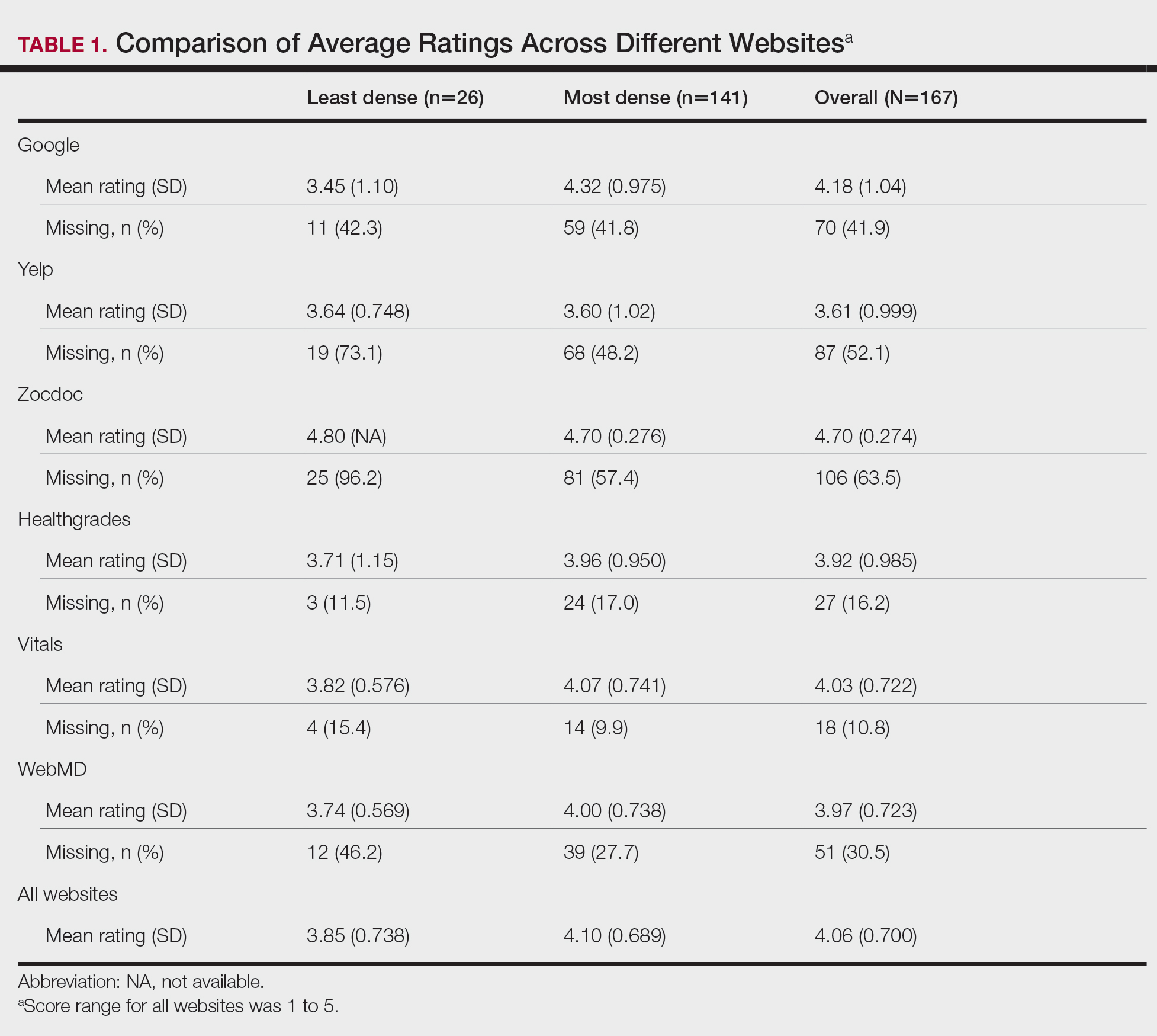

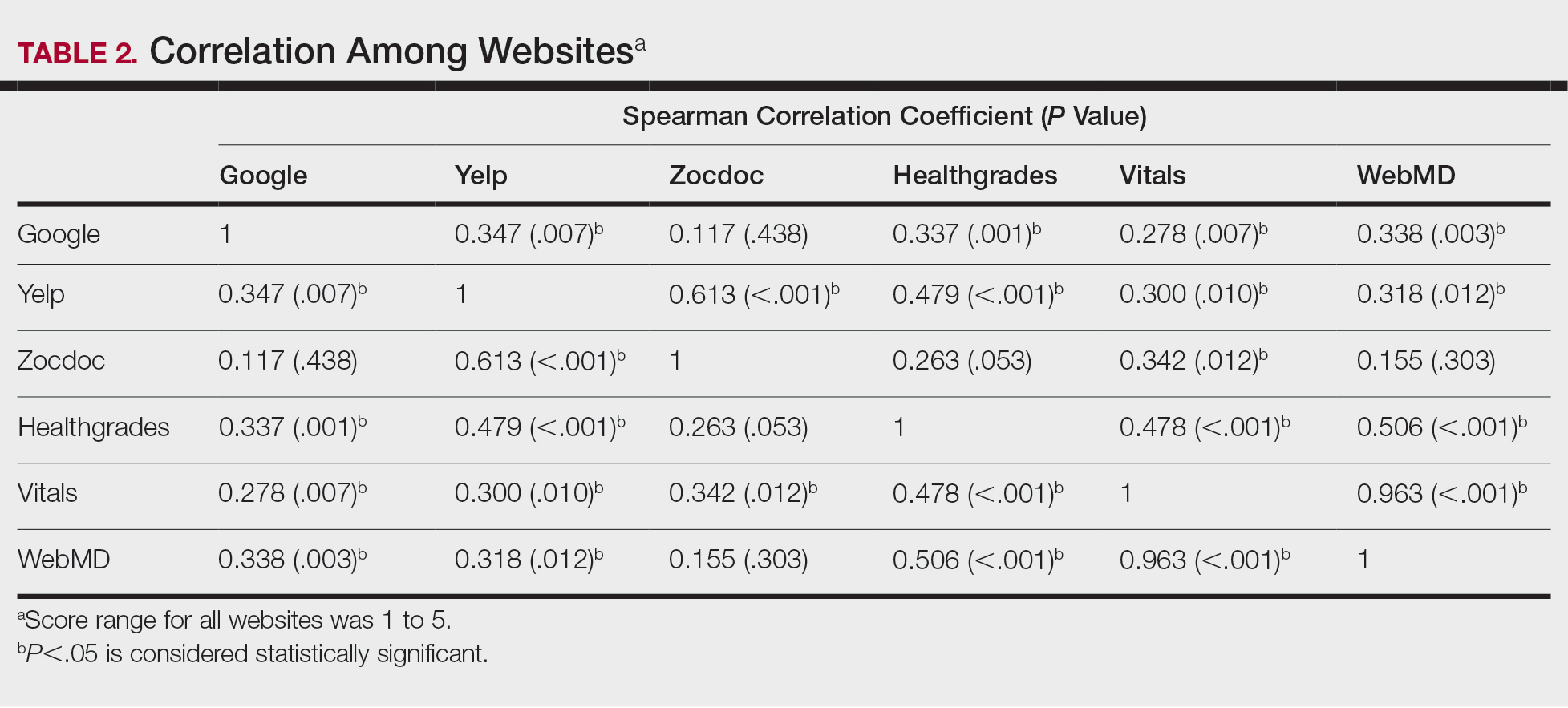

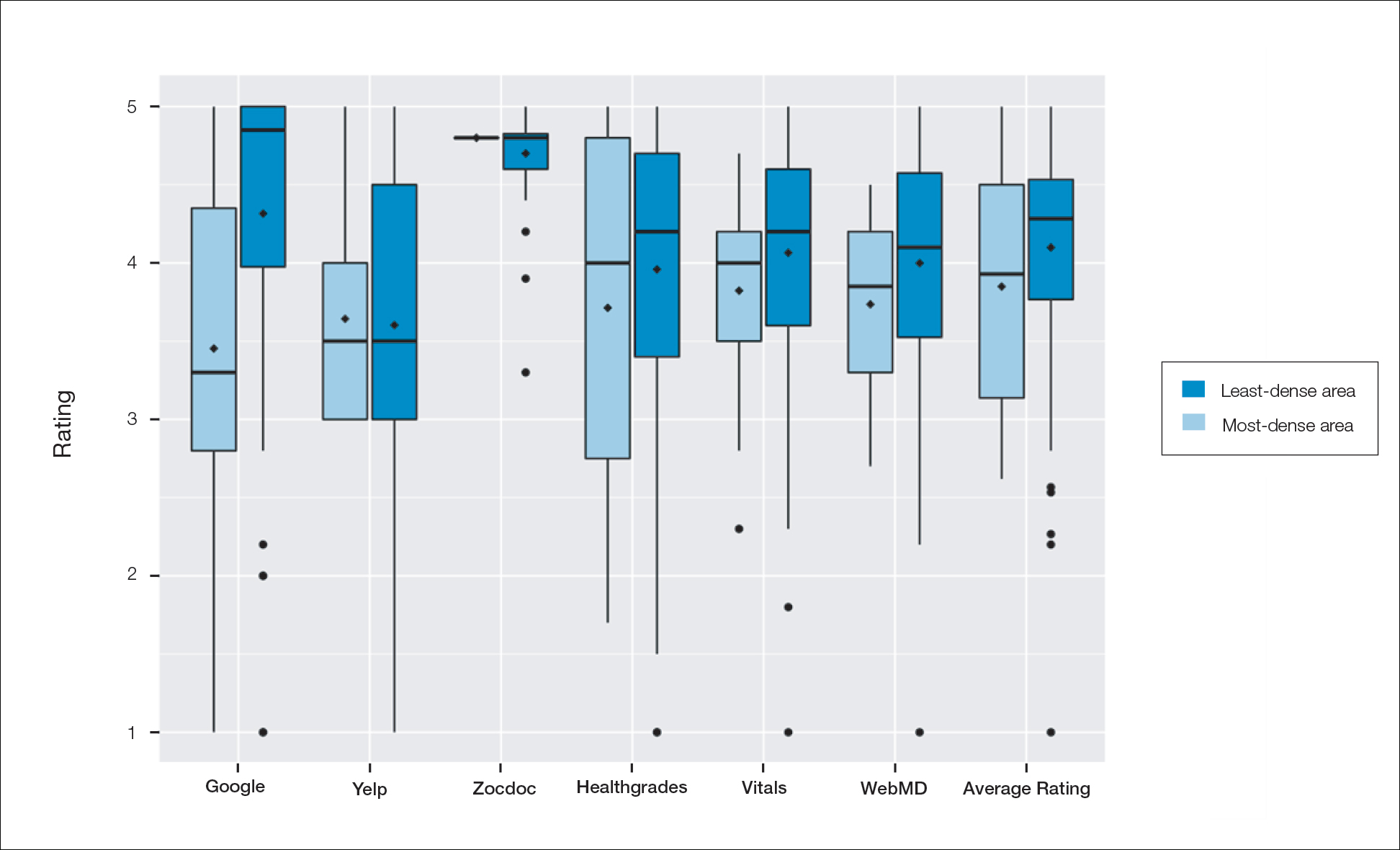

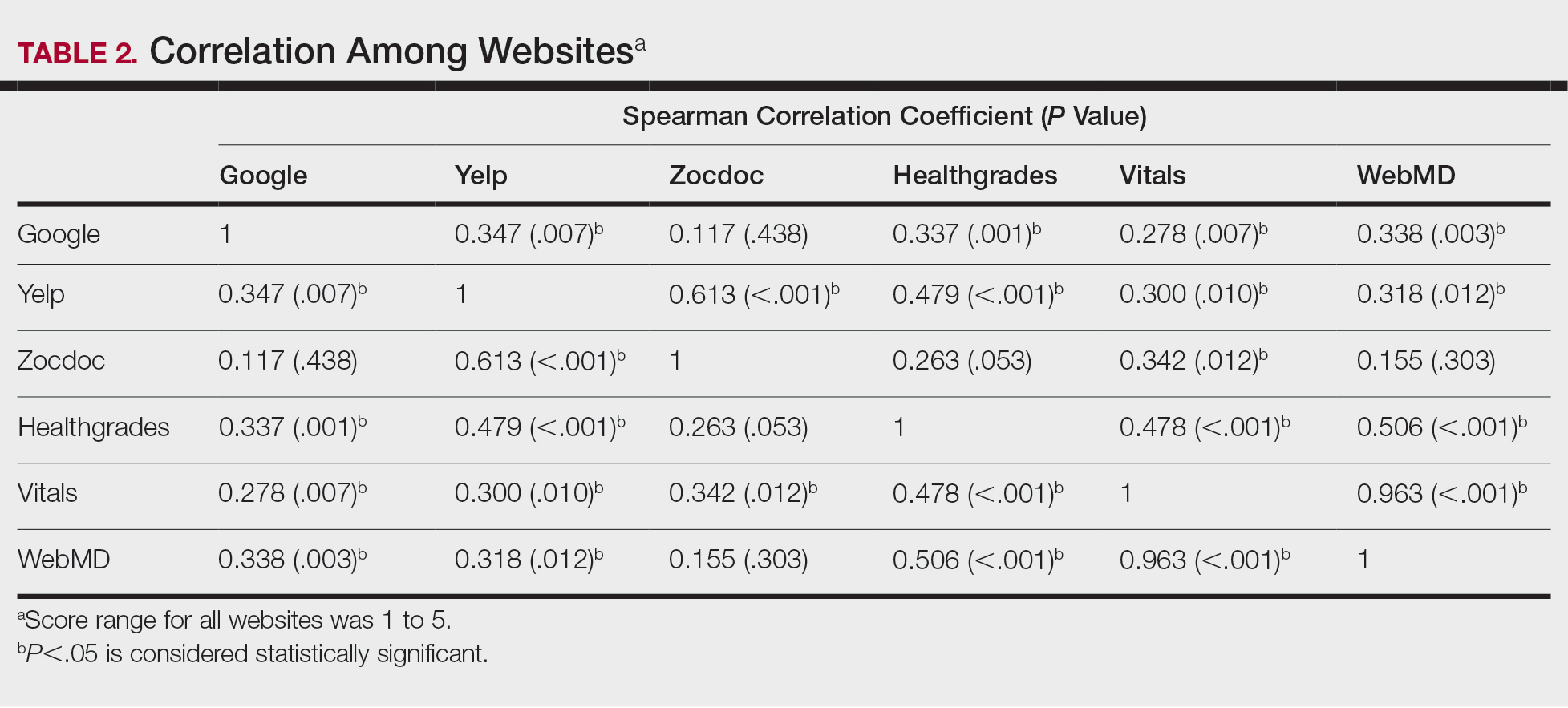

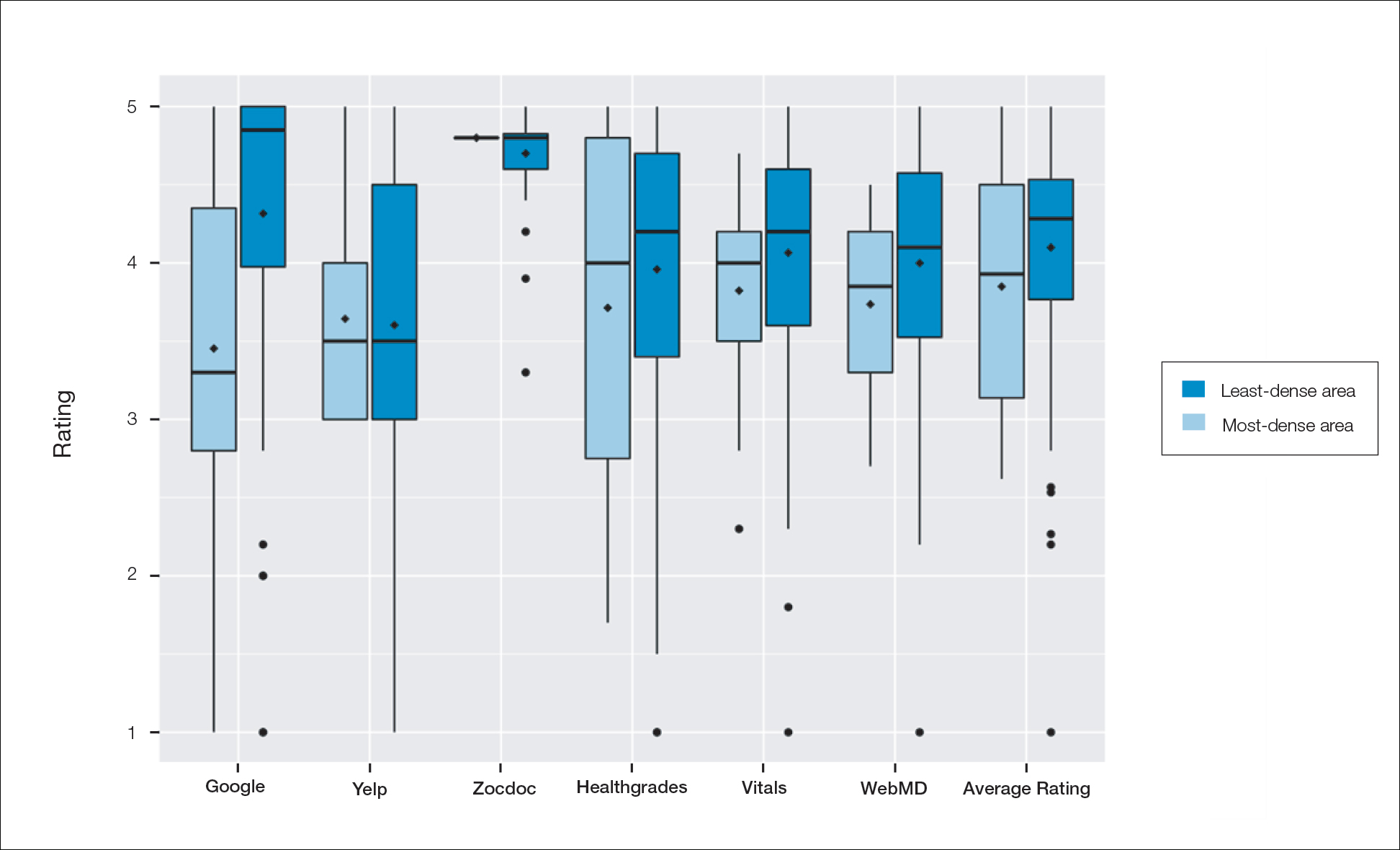

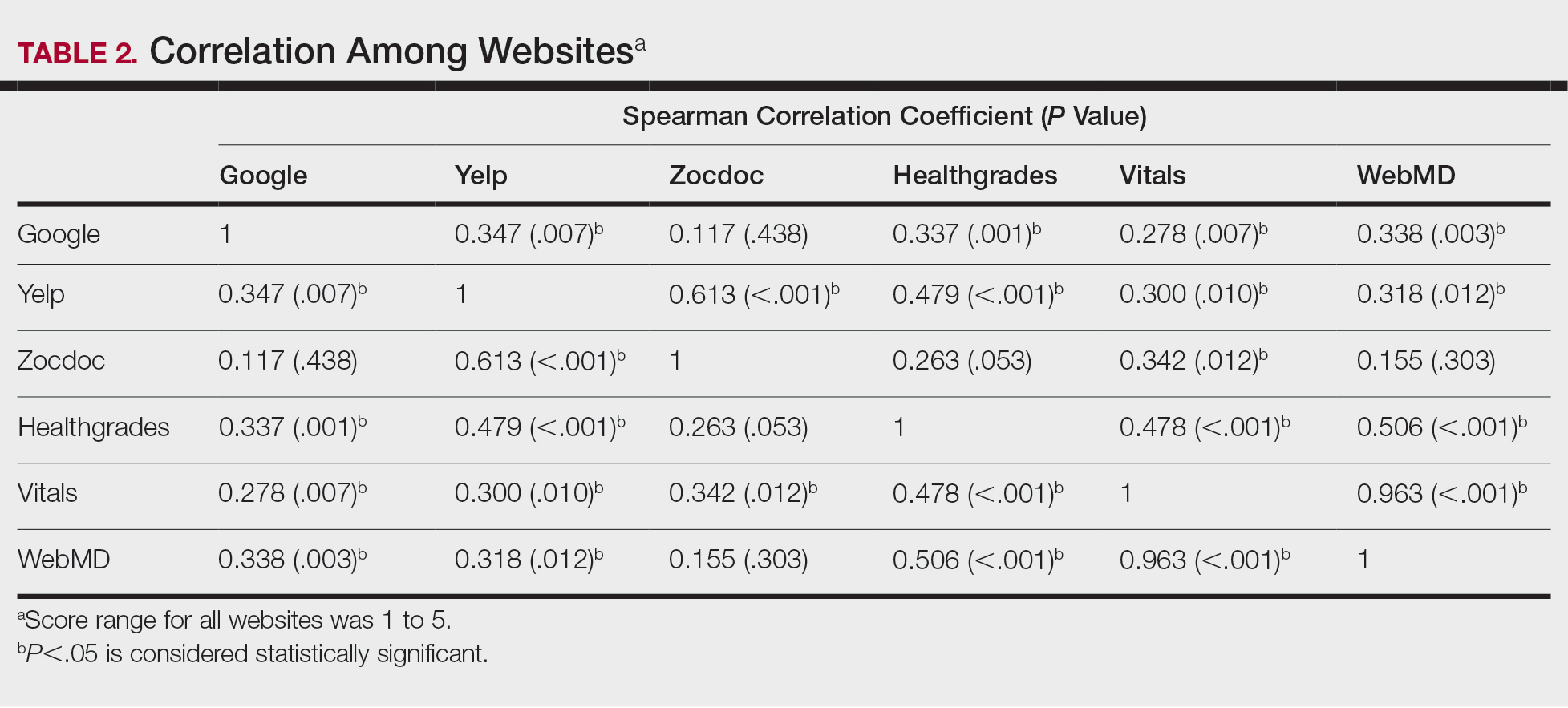

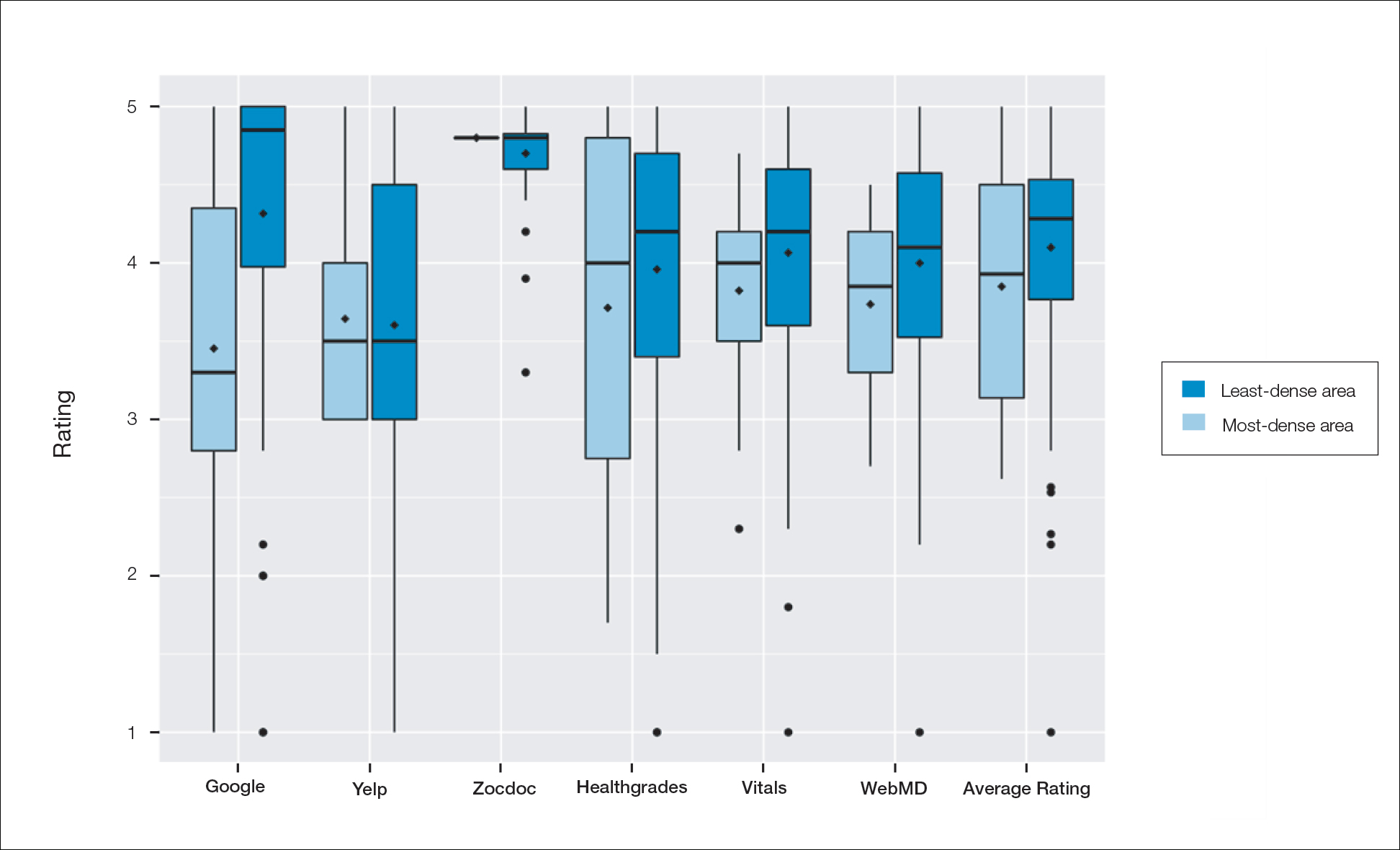

A total of 167 representative physicians were included in this analysis; 141 from the most dense areas, and 26 from the least dense areas. The lowest average ratings for the entire sample and most dermatologist–dense areas were found on Yelp (3.61 and 3.60, respectively), and the lowest ratings in the least dermatologist–dense areas were found on Google (3.45)(Table 1). Correlation coefficient values were lowest for Zocdoc and Healthgrades (0.263) and highest for Vitals and WebMD (0.963)(Table 2). The health care–specific sites were closer to the overall average (4.06) than the general consumer sites (eFigure).

Comment

Although dermatologist ratings on each site had a broad range, we found that patients typically expressed negative interactions on general consumer websites rather than health care–specific websites. When comparing the ratings of the same group of dermatologists across different sites, ratings on health care–specific sites had a higher degree of correlation, with physician ratings more similar between 2 health care–specific sites and less similar between a health care–specific and a general consumer website. This pattern was consistent in both dermatologist-dense and dermatologist-poor areas, despite patients having varying levels of access to dermatologic care and medical resources and potentially different regional preferences of consumer websites. Taken together, these findings imply that health care–specific websites more consistently reflect overall patient sentiment.

Although one 2016 study comparing reviews of dermatology practices on Zocdoc and Yelp also demonstrated lower average ratings on Yelp,3 our study suggests that this trend is not isolated to these 2 sites but can be seen when comparing many health care–specific sites vs general consumer sites.

Our study compared ratings of dermatologists among popular websites to understand those that are most representative of patient attitudes toward physicians. These findings are important because online reviews reflect the entire patient experience, not just the patient-physician interaction, which may explain why physician scores on standardized questionnaires, such as Press Ganey surveys, do not correlate well with their online reviews.4 In a study comparing 98 physicians with negative online ratings to 82 physicians in similar departments with positive ratings, there was no significant difference in scores on patient-physician interaction questions on the Press Ganey survey.5 However, physicians who received negative online reviews scored lower on Press Ganey questions related to nonphysician interactions (eg, office cleanliness, interactions with staff).

The current study was subject to several limitations. Our analysis included all physicians in our random selection without accounting for those physicians with a greater online presence who might be more cognizant of these ratings and try to manipulate them through a reputation-management company or public relations consultant.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that consumer websites are not primarily used by disgruntled patients wishing to express grievances; instead, on average, most physicians received positive reviews. Furthermore, health care–specific websites show a higher degree of concordance than and may more accurately reflect overall patient attitudes toward their physicians than general consumer sites. Reviews from these health care–specific sites may be more helpful than general consumer websites in allowing physicians to understand patient sentiment and improve patient experiences.

- Frost C, Mesfin A. Online reviews of orthopedic surgeons: an emerging trend. Orthopedics. 2015;38:e257-e262. doi:10.3928/01477447-20150402-52

- Waqas B, Cooley V, Lipner SR. Association of sex, location, and experience with online patient ratings of dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:954-955.

- Smith RJ, Lipoff JB. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews: lessons from qualitative analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3950

- Chen J, Presson A, Zhang C, et al. Online physician review websites poorly correlate to a validated metric of patient satisfaction. J Surg Res. 2018;227:1-6.

- Widmer RJ, Maurer MJ, Nayar VR, et al. Online physician reviews do not reflect patient satisfaction survey responses. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2018;93:453-457.

Health care–specific (eg, Healthgrades, Zocdoc, Vitals, WebMD) and general consumer websites (eg, Google, Yelp) are popular platforms for patients to find physicians, schedule appointments, and review physician experiences. Patients find ratings on these websites more trustworthy than standardized surveys distributed by hospitals, but many physicians do not trust the reviews on these sites. For example, in a survey of both physicians (n=828) and patients (n=494), 36% of physicians trusted online reviews compared to 57% of patients.1 The objective of this study was to determine if health care–specific or general consumer websites more accurately reflect overall patient sentiment. This knowledge can help physicians who are seeking to improve the patient experience understand which websites have more accurate and trustworthy reviews.

Methods

A list of dermatologists from the top 10 most and least dermatologist–dense areas in the United States was compiled to examine different physician populations.2 Equal numbers of male and female dermatologists were randomly selected from the most dense areas. All physicians were included from the least dense areas because of limited sample size. Ratings were collected from websites most likely to appear on the first page of a Google search for a physician name, as these are most likely to be seen by patients. Descriptive statistics were generated to describe the study population; mean and median physician rating (using a scale of 1–5); SD; and minimum, maximum, and interquartile ranges. Spearman correlation coefficients were generated to examine the strength of association between ratings from website pairs. P<.05 was considered statistically significant, with analyses performed in R (3.6.2) for Windows (the R Foundation).

Results

A total of 167 representative physicians were included in this analysis; 141 from the most dense areas, and 26 from the least dense areas. The lowest average ratings for the entire sample and most dermatologist–dense areas were found on Yelp (3.61 and 3.60, respectively), and the lowest ratings in the least dermatologist–dense areas were found on Google (3.45)(Table 1). Correlation coefficient values were lowest for Zocdoc and Healthgrades (0.263) and highest for Vitals and WebMD (0.963)(Table 2). The health care–specific sites were closer to the overall average (4.06) than the general consumer sites (eFigure).

Comment

Although dermatologist ratings on each site had a broad range, we found that patients typically expressed negative interactions on general consumer websites rather than health care–specific websites. When comparing the ratings of the same group of dermatologists across different sites, ratings on health care–specific sites had a higher degree of correlation, with physician ratings more similar between 2 health care–specific sites and less similar between a health care–specific and a general consumer website. This pattern was consistent in both dermatologist-dense and dermatologist-poor areas, despite patients having varying levels of access to dermatologic care and medical resources and potentially different regional preferences of consumer websites. Taken together, these findings imply that health care–specific websites more consistently reflect overall patient sentiment.

Although one 2016 study comparing reviews of dermatology practices on Zocdoc and Yelp also demonstrated lower average ratings on Yelp,3 our study suggests that this trend is not isolated to these 2 sites but can be seen when comparing many health care–specific sites vs general consumer sites.

Our study compared ratings of dermatologists among popular websites to understand those that are most representative of patient attitudes toward physicians. These findings are important because online reviews reflect the entire patient experience, not just the patient-physician interaction, which may explain why physician scores on standardized questionnaires, such as Press Ganey surveys, do not correlate well with their online reviews.4 In a study comparing 98 physicians with negative online ratings to 82 physicians in similar departments with positive ratings, there was no significant difference in scores on patient-physician interaction questions on the Press Ganey survey.5 However, physicians who received negative online reviews scored lower on Press Ganey questions related to nonphysician interactions (eg, office cleanliness, interactions with staff).

The current study was subject to several limitations. Our analysis included all physicians in our random selection without accounting for those physicians with a greater online presence who might be more cognizant of these ratings and try to manipulate them through a reputation-management company or public relations consultant.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that consumer websites are not primarily used by disgruntled patients wishing to express grievances; instead, on average, most physicians received positive reviews. Furthermore, health care–specific websites show a higher degree of concordance than and may more accurately reflect overall patient attitudes toward their physicians than general consumer sites. Reviews from these health care–specific sites may be more helpful than general consumer websites in allowing physicians to understand patient sentiment and improve patient experiences.

Health care–specific (eg, Healthgrades, Zocdoc, Vitals, WebMD) and general consumer websites (eg, Google, Yelp) are popular platforms for patients to find physicians, schedule appointments, and review physician experiences. Patients find ratings on these websites more trustworthy than standardized surveys distributed by hospitals, but many physicians do not trust the reviews on these sites. For example, in a survey of both physicians (n=828) and patients (n=494), 36% of physicians trusted online reviews compared to 57% of patients.1 The objective of this study was to determine if health care–specific or general consumer websites more accurately reflect overall patient sentiment. This knowledge can help physicians who are seeking to improve the patient experience understand which websites have more accurate and trustworthy reviews.

Methods

A list of dermatologists from the top 10 most and least dermatologist–dense areas in the United States was compiled to examine different physician populations.2 Equal numbers of male and female dermatologists were randomly selected from the most dense areas. All physicians were included from the least dense areas because of limited sample size. Ratings were collected from websites most likely to appear on the first page of a Google search for a physician name, as these are most likely to be seen by patients. Descriptive statistics were generated to describe the study population; mean and median physician rating (using a scale of 1–5); SD; and minimum, maximum, and interquartile ranges. Spearman correlation coefficients were generated to examine the strength of association between ratings from website pairs. P<.05 was considered statistically significant, with analyses performed in R (3.6.2) for Windows (the R Foundation).

Results

A total of 167 representative physicians were included in this analysis; 141 from the most dense areas, and 26 from the least dense areas. The lowest average ratings for the entire sample and most dermatologist–dense areas were found on Yelp (3.61 and 3.60, respectively), and the lowest ratings in the least dermatologist–dense areas were found on Google (3.45)(Table 1). Correlation coefficient values were lowest for Zocdoc and Healthgrades (0.263) and highest for Vitals and WebMD (0.963)(Table 2). The health care–specific sites were closer to the overall average (4.06) than the general consumer sites (eFigure).

Comment

Although dermatologist ratings on each site had a broad range, we found that patients typically expressed negative interactions on general consumer websites rather than health care–specific websites. When comparing the ratings of the same group of dermatologists across different sites, ratings on health care–specific sites had a higher degree of correlation, with physician ratings more similar between 2 health care–specific sites and less similar between a health care–specific and a general consumer website. This pattern was consistent in both dermatologist-dense and dermatologist-poor areas, despite patients having varying levels of access to dermatologic care and medical resources and potentially different regional preferences of consumer websites. Taken together, these findings imply that health care–specific websites more consistently reflect overall patient sentiment.

Although one 2016 study comparing reviews of dermatology practices on Zocdoc and Yelp also demonstrated lower average ratings on Yelp,3 our study suggests that this trend is not isolated to these 2 sites but can be seen when comparing many health care–specific sites vs general consumer sites.

Our study compared ratings of dermatologists among popular websites to understand those that are most representative of patient attitudes toward physicians. These findings are important because online reviews reflect the entire patient experience, not just the patient-physician interaction, which may explain why physician scores on standardized questionnaires, such as Press Ganey surveys, do not correlate well with their online reviews.4 In a study comparing 98 physicians with negative online ratings to 82 physicians in similar departments with positive ratings, there was no significant difference in scores on patient-physician interaction questions on the Press Ganey survey.5 However, physicians who received negative online reviews scored lower on Press Ganey questions related to nonphysician interactions (eg, office cleanliness, interactions with staff).

The current study was subject to several limitations. Our analysis included all physicians in our random selection without accounting for those physicians with a greater online presence who might be more cognizant of these ratings and try to manipulate them through a reputation-management company or public relations consultant.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that consumer websites are not primarily used by disgruntled patients wishing to express grievances; instead, on average, most physicians received positive reviews. Furthermore, health care–specific websites show a higher degree of concordance than and may more accurately reflect overall patient attitudes toward their physicians than general consumer sites. Reviews from these health care–specific sites may be more helpful than general consumer websites in allowing physicians to understand patient sentiment and improve patient experiences.

- Frost C, Mesfin A. Online reviews of orthopedic surgeons: an emerging trend. Orthopedics. 2015;38:e257-e262. doi:10.3928/01477447-20150402-52

- Waqas B, Cooley V, Lipner SR. Association of sex, location, and experience with online patient ratings of dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:954-955.

- Smith RJ, Lipoff JB. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews: lessons from qualitative analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3950

- Chen J, Presson A, Zhang C, et al. Online physician review websites poorly correlate to a validated metric of patient satisfaction. J Surg Res. 2018;227:1-6.

- Widmer RJ, Maurer MJ, Nayar VR, et al. Online physician reviews do not reflect patient satisfaction survey responses. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2018;93:453-457.

- Frost C, Mesfin A. Online reviews of orthopedic surgeons: an emerging trend. Orthopedics. 2015;38:e257-e262. doi:10.3928/01477447-20150402-52

- Waqas B, Cooley V, Lipner SR. Association of sex, location, and experience with online patient ratings of dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:954-955.

- Smith RJ, Lipoff JB. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews: lessons from qualitative analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3950

- Chen J, Presson A, Zhang C, et al. Online physician review websites poorly correlate to a validated metric of patient satisfaction. J Surg Res. 2018;227:1-6.

- Widmer RJ, Maurer MJ, Nayar VR, et al. Online physician reviews do not reflect patient satisfaction survey responses. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2018;93:453-457.

Practice Points

- Online physician-rating websites are commonly used by patients to find physicians and review experiences.

- Health care–specific sites may more accurately reflect patient sentiment than general consumer sites.

- Dermatologists can use health care–specific sites to understand patient sentiment and learn how to improve patient experiences.

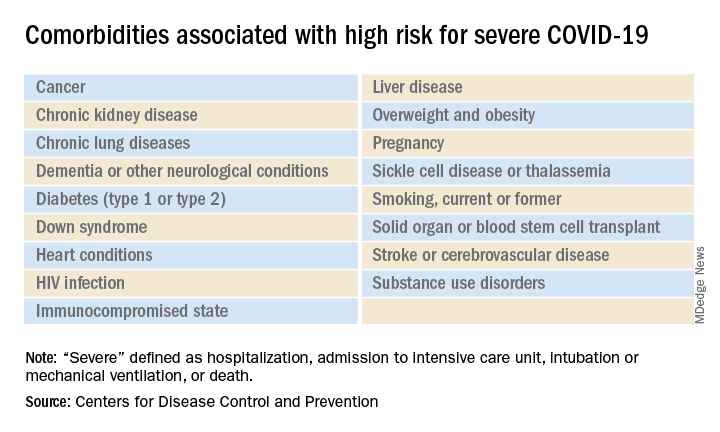

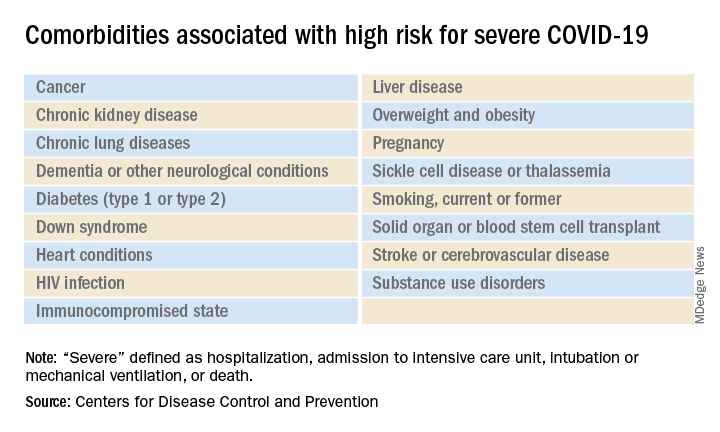

List of COVID-19 high-risk comorbidities expanded

The list of medical according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC’s latest list consists of 17 conditions or groups of related conditions that may increase patients’ risk of developing severe outcomes of COVID-19, the CDC said on a web page intended for the general public.

On a separate page, the CDC defines severe outcomes “as hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death.”

Asthma is included in the newly expanded list with other chronic lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cystic fibrosis; the list’s heart disease entry covers coronary artery disease, heart failure, cardiomyopathies, and hypertension, the CDC said.

The list of medical according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC’s latest list consists of 17 conditions or groups of related conditions that may increase patients’ risk of developing severe outcomes of COVID-19, the CDC said on a web page intended for the general public.

On a separate page, the CDC defines severe outcomes “as hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death.”

Asthma is included in the newly expanded list with other chronic lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cystic fibrosis; the list’s heart disease entry covers coronary artery disease, heart failure, cardiomyopathies, and hypertension, the CDC said.

The list of medical according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC’s latest list consists of 17 conditions or groups of related conditions that may increase patients’ risk of developing severe outcomes of COVID-19, the CDC said on a web page intended for the general public.

On a separate page, the CDC defines severe outcomes “as hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death.”

Asthma is included in the newly expanded list with other chronic lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cystic fibrosis; the list’s heart disease entry covers coronary artery disease, heart failure, cardiomyopathies, and hypertension, the CDC said.

COVID-19 Monoclonal Antibody Infusions: A Multidisciplinary Initiative to Operationalize EUA Novel Treatment Options

From Mount Sinai Medical Center, Miami Beach, FL.

Abstract

Objective: To develop and implement a process for administering COVID-19 monoclonal antibody infusions for outpatients with mild or moderate COVID-19 at high risk for hospitalization, using multidisciplinary collaboration, US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance, and infection prevention standards.

Methods: When monoclonal antibody therapy became available for mild or moderate COVID-19 outpatients via Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), our institution sought to provide this therapy option to our patients. We describe the process for planning, implementing, and maintaining a successful program for administering novel therapies based on FDA guidance and infection prevention standards. Key components of our implementation process were multidisciplinary planning involving decision makers and stakeholders; setting realistic goals in the process; team communication; and measuring and reporting quality improvement on a regular basis.

Results: A total of 790 COVID-19 monoclonal antibody infusions were administered from November 20, 2020 to March 5, 2021. Steps to minimize the likelihood of adverse drug reactions were implemented and a low incidence (< 1%) has occurred. There has been no concern from staff regarding infection during the process. Rarely, patients have raised cost-related concerns, typically due to incomplete communication regarding billing prior to the infusion. Patients, families, nursing staff, physicians, pharmacy, and hospital administration have expressed satisfaction with the program.

Conclusion: This process can provide a template for other hospitals or health care delivery facilities to provide novel therapies to patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 in a safe and effective manner.

Keywords: COVID-19; monoclonal antibody; infusion; emergency use authorization.

SARS-CoV-2 and the disease it causes, COVID-19, have transformed from scientific vernacular to common household terms. It began with a cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown etiology in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, with physicians there reporting a novel coronavirus strain (2019-nCoV), now referred to as SARS-CoV-2. Rapid spread of this virus resulted in the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring an international public health emergency. Since this time, the virus has evolved into a worldwide pandemic. COVID-19 has dramatically impacted our society, resulting in more than 2.63 million global deaths as of this writing, of which more than 527,000 deaths have occurred in the United States.1 This novel virus has resulted in a flurry of literature, research, therapies, and collaboration across multiple disciplines in an effort to prevent, treat, and mitigate cases and complications of this disease.

On November 9, 2020, and November 21, 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued Emergency Use Authorizations (EUA) for 2 novel COVID-19 monoclonal therapies, bamlanivimab2-3 and casirivimab/imdevimab,3-4 respectively. The EUAs granted permission for these therapies to be administered for the treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 in adult and pediatric patients (≥ 12 years and weighing at least 40 kg) with positive results of direct SARS-CoV-2 viral testing and who are at high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19 and/or hospitalization. The therapies work by targeting the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and subsequent attachment to human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors. Clinical trial data leading to the EUA demonstrated a reduction in viral load, safe outcome, and most importantly, fewer hospitalization and emergency room visits, as compared to the placebo group.5-7 The use of monoclonal antibodies is not new and gained recognition during the Ebola crisis, when the monoclonal antibody to the Ebola virus showed a significant survival benefit.8 Providing monoclonal antibody therapy soon after symptom onset aligns with a shift from the onset of the pandemic to the current focus on the administration of pharmaceutical therapy early in the disease course. This shift prevents progression to severe COVID-19, with the goal of reducing patient mortality, hospitalizations, and strain on health care systems.

The availability of novel neutralizing monoclonal antibodies for COVID-19 led to discussions of how to incorporate these therapies as new options for patients. Our institution networked with colleagues from multiple disciplines to discuss processes and policies for the safe administration of the monoclonal antibody infusion therapies. Federal health leaders urge more use of monoclonal antibodies, but many hospitals have been unable to successfully implement infusions due to staff and logistical challenges.9 This article presents a viable process that hospitals can use to provide these novel therapies to outpatients with mild to moderate COVID-19.

The Mount Sinai Medical Center, Florida Experience

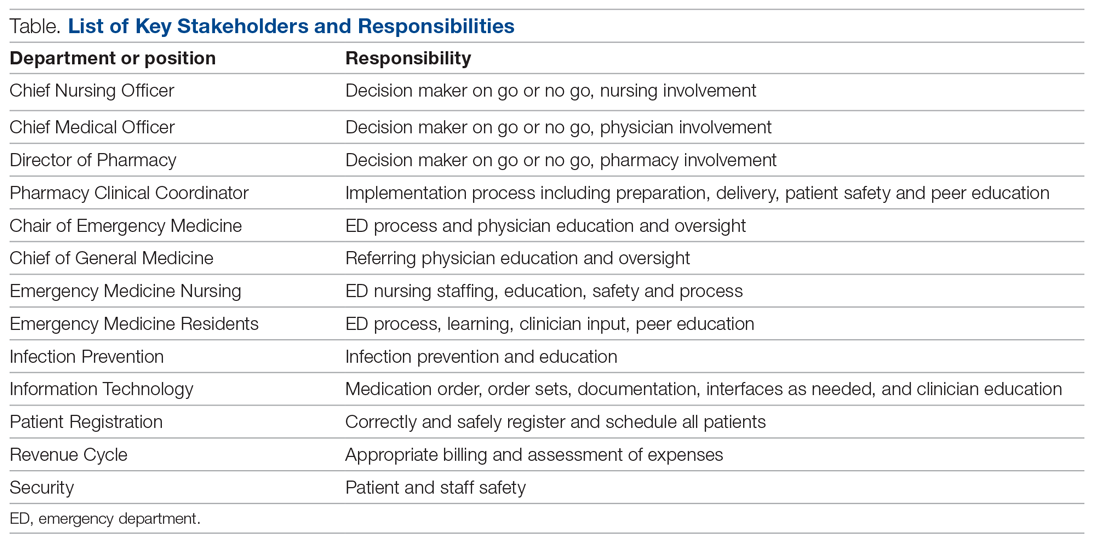

Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami Beach, Florida, is the largest private, independent, not-for-profit teaching hospital in South Florida, comprising 672 licensed beds and supporting 150,000 emergency department (ED) visits annually. Per the EUA criteria for use, COVID-19 monoclonal antibody therapies are not authorized for patients who are hospitalized or who require oxygen therapy due to COVID-19. Therefore, options for outpatient administration needed to be evaluated. Directly following the first EUA press release, a task force of key stakeholders was assembled to brainstorm and develop a process to offer this therapy to the community. A multidisciplinary task force with representation from the ED, nursing, primary care, hospital medicine, pharmacy, risk management, billing, information technology, infection prevention, and senior level leadership participated (Table).

The task force reviewed institutional outpatient locations to determine whether offering this service would be feasible (eg, ED, ambulatory care facilities, cancer center). The ED was selected because it would offer the largest array of appointment times to meet the community needs with around-the-clock availability. While Mount Sinai Medical Center offers care in 3 emergency center locations in Aventura, Hialeah, and Miami Beach, it was determined to initiate the infusions at the main campus center in Miami Beach only. The main campus affords an onsite pharmacy with suitable staffing to prepare the anticipated volume of infusions in a timely manner, as both therapies have short stabilities following preparation. Thus, it was decided that patients from freestanding emergency centers in Aventura and Hialeah would be moved to the Miami Beach ED location to receive therapy. Operating at a single site also allowed for more rapid implementation, monitoring, and ability to make modifications more easily. Discussions for the possible expansion of COVID-19 monoclonal antibody infusions at satellite locations are underway.

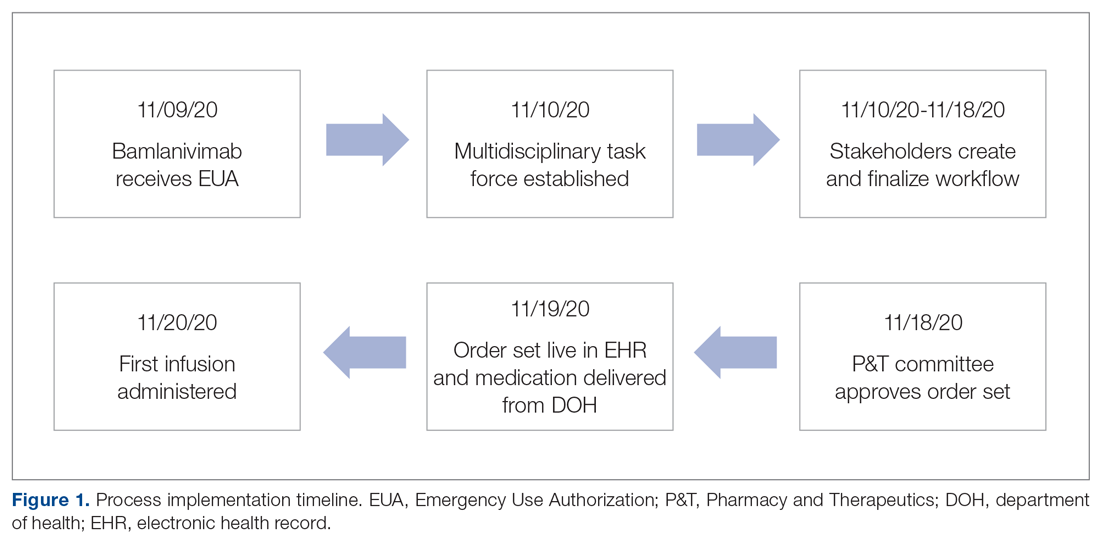

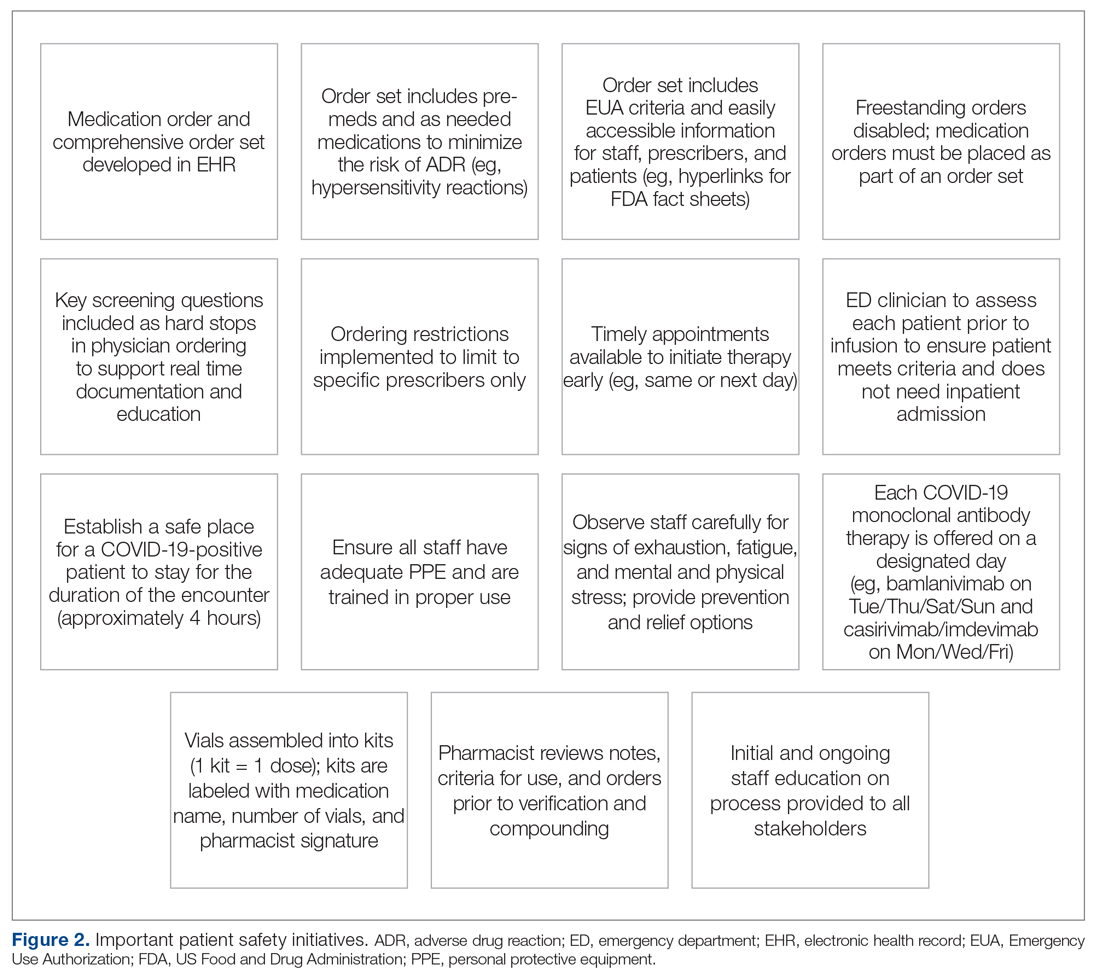

On November 20, 2020, 11 days after the formation of the multidisciplinary task force, the first COVID-19 monoclonal infusion was successfully administered. Figure 1 depicts the timeline from assessment to program implementation. Critical to implementation was the involvement of decision makers from all necessary departments early in the planning process to ensure that standard operating procedures were followed and that the patients, community, and organization had a positive experience. This allowed for simultaneous planning of electronic health record (Epic; EHR) builds, departmental workflows, and staff education, as described in the following section. Figure 2 shows the patient safety activities included in the implementation process.

Key Stakeholder Involvement and Workflow

On the day of bamlanivimab EUA release, email communication was shared among hospital leadership with details of the press release. Departments were quickly involved to initiate a task force to assess if and how this therapy could be offered at Mount Sinai Medical Center. The following sections explain the role of each stakeholder and their essential role to operationalize these novel EUA treatment options. The task force was organized and led by our chief medical officer and chief nursing officer.

Information Technology

Medication Ordering and Documentation EHR and Smart Pumps. Early in the pandemic, the antimicrobial stewardship (ASP) clinical coordinator became the designated point person for pharmacy assessment of novel COVID-19 therapies. As such, this pharmacist began reviewing the bamlanivimab and, later, the casirivimab/imdevimab EUA Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers. All necessary elements for the complete and safe ordering and dispensing of the medication were developed and reviewed by pharmacy administration and ED nursing leadership for input, prior to submitting to the information technology team for implementation. Building the COVID-19 monoclonal medication records into the EHR allowed for detailed direction (ie, administration and preparation instructions) to be consistently applied. The medication records were also built into hospital smart pumps so that nurses could access prepopulated, accurate volumes and infusion rates to minimize errors.

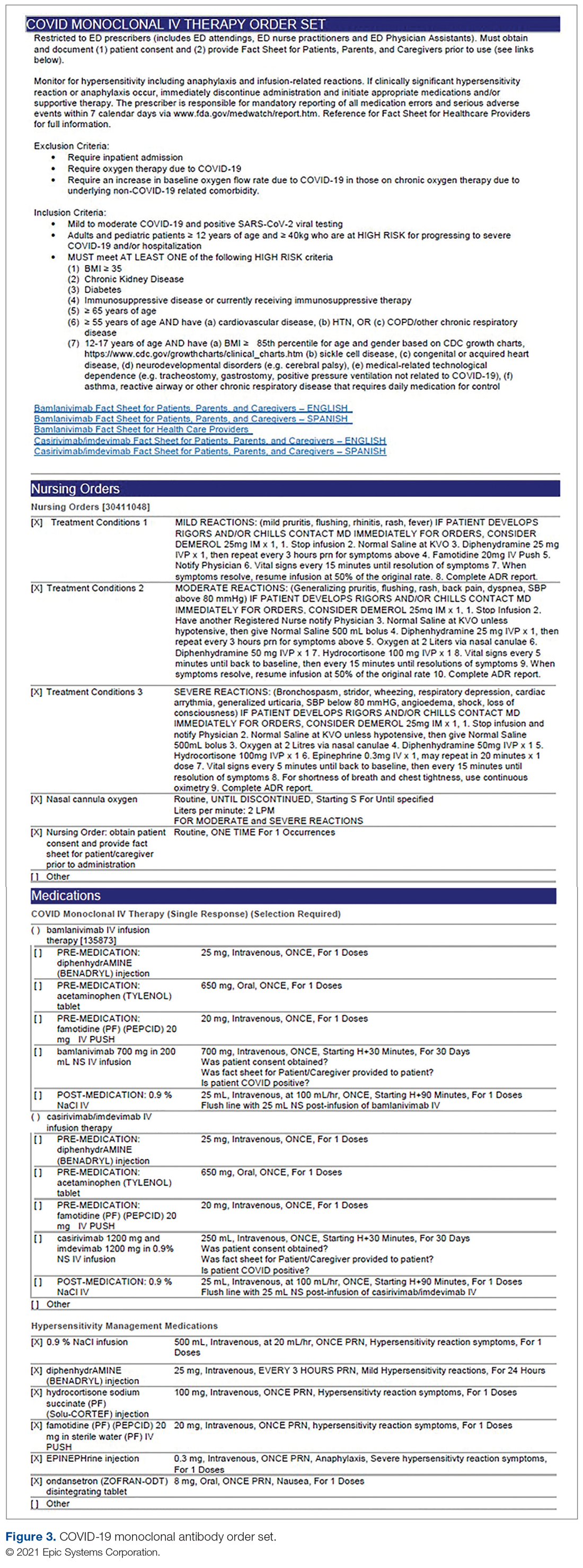

Order Set Development. The pharmacy medication build was added to a comprehensive order set (Figure 3), which was then developed to guide prescribers and standardize the process around ordering of COVID-19 monoclonal therapies. While these therapies are new, oncology monoclonal therapies are regularly administered to outpatients at Mount Sinai Cancer Center. The cancer center was therefore consulted on their process surrounding best practices in administration of monoclonal antibody therapies. This included protocols for medications used in pretreatment and management of hypersensitivity reactions and potential adverse drug reactions of both COVID-19 monoclonal therapies. These medication orders were selected by default in the order set to ensure that all patients received premedications aimed at minimizing the risk of hypersensitivity reaction, and had as-needed medication orders, in the event a hypersensitivity reaction occurred. Reducing hypersensitivity reaction risk is important as well to increase the likelihood that the patient would receive full therapy, as management of this adverse drug reactions involves possible cessation of therapy depending on the level of severity. The pharmacy department also ensured these medications were stocked in ED automated dispensing cabinets to promote quick access. In addition to the aforementioned nursing orders, we added EUA criteria for use and hyperlinks to the Fact Sheets for Patients and Caregivers and Health Care Providers for each monoclonal therapy, and restricted ordering to ED physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants.

The order set underwent multidisciplinary review by pharmacy administration, the chair of emergency medicine, physicians, and ED nursing leadership prior to presentation and approval by the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee. Lastly, at time of implementation, the order set was added to the ED preference list, preventing inpatient access. Additionally, as a patient safety action, free- standing orders of COVID-19 monoclonal therapies were disabled, so providers could only order therapies via the approved, comprehensive order set.

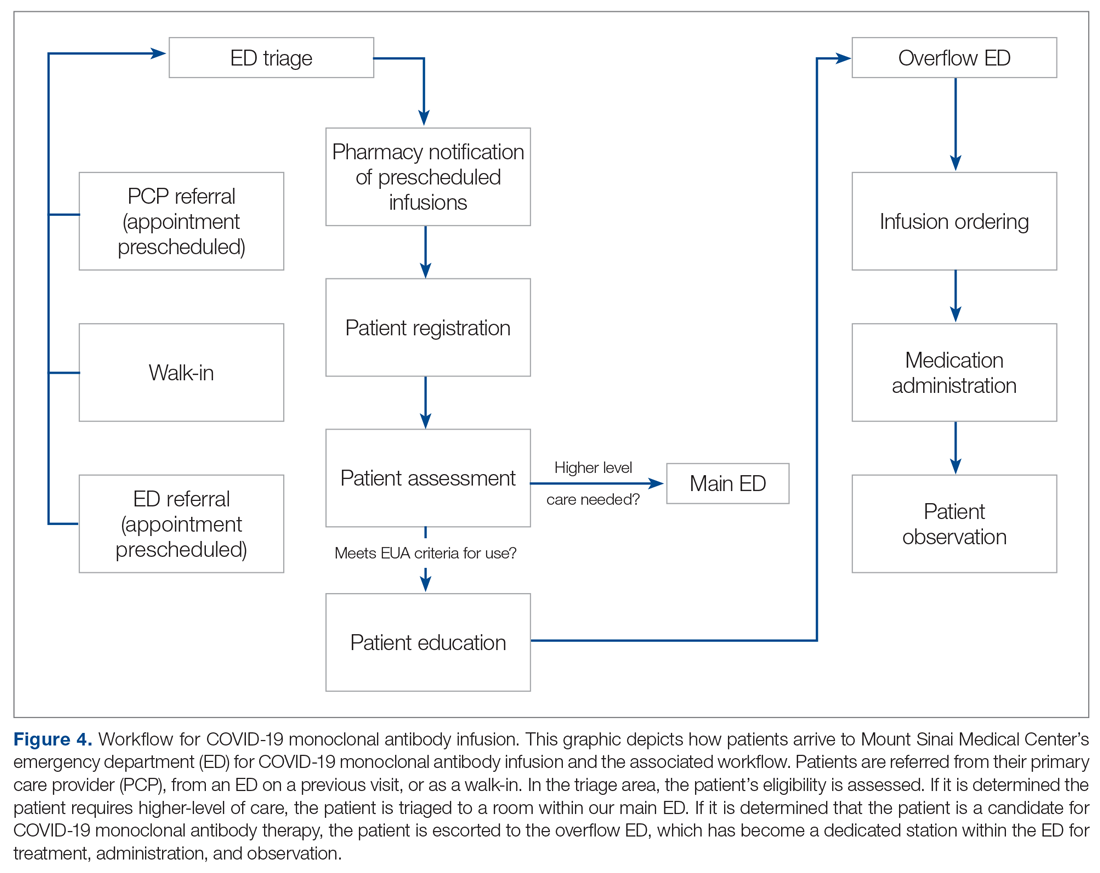

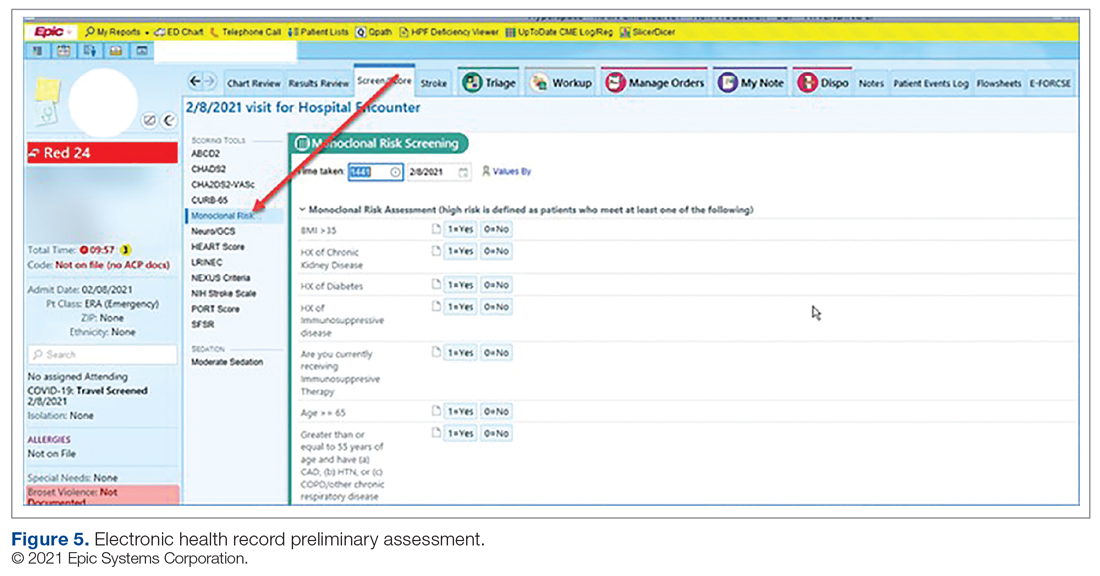

Preliminary Assessment Tool. A provider assessment tool was developed to document patient-specific EUA criteria for use during initial assessment (Figure 4). This tool serves as a checklist and is visible to the full multidisciplinary team in the patient’s EHR. It is used as a resource at the time of pharmacist verification and ED physician assessment to ensure criteria for use are met.

Outpatient Offices

Patient Referral. Patients with symptoms or concerns of COVID-19 exposure can make physician appointments via telemedicine or in person at Mount Sinai Medical Center’s primary care and specialty offices. At the time of patient encounter, physicians suspecting a COVID-19 diagnosis will refer patients for outpatient COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) laboratory testing, which has an approximate 24-hour turnaround to results. Physicians also assess whether the patient meets EUA criteria for use, pending results of testing. In the event a patient meets EUA criteria for use, the physician provides patient counseling and requests verbal consent. Following this, the physician enters a note in the EHR describing the patient’s condition, criteria for use evaluation, and the patient’s verbal agreement to therapy. This preliminary screening is beneficial to begin planning with both the patient and ED to minimize delays. Patients are notified of the results of their test once available. If the COVID-19 PCR test returns positive, the physician will call the ED at the main campus and schedule the patient for COVID-19 monoclonal therapy. As the desired timeframe for administering COVID-19 monoclonal therapies is within less than 10 days of symptom onset, timely scheduling of appointments is crucial. Infusion appointments are typically provided the same or next day. The patients are informed that they must bring documentation of their positive COVID-19 PCR test to their ED visit. Lastly, because patients are pretreated with medication that may potentially impair driving, they are instructed that they cannot drive themselves home; ride shares also are not allowed in order to limit the spread of infection.

Emergency Department

Patient Arrival and Screening. A COVID-19 patient can be evaluated in the ED 1 of 2 ways. The first option is via outpatient office referral, as described previously. Upon arrival to the ED, a second screening is performed to ensure the patient still meets EUA criteria for use and the positive COVID-19 PCR test result is confirmed. If the patient no longer meets criteria, the patient is triaged accordingly, including evaluation for higher-level care (eg, supplemental oxygen, hospital admission). The second optoion is via new patient walk-ins without outpatient physician referral (Figure 4). In these cases, an initial screening is performed, documenting EUA criteria for use in the preliminary assessment (Figure 5). Physicians will consider an outside COVID-19 test as valid, so long as documentation is readily available confirming a positive PCR result. Otherwise, an in-house COVID-19 PCR test will be performed, which has a 2-hour turnaround time.

Infusion Schedule. The ED offers a total of 16 COVID-19 monoclonal infusions slots daily. These are broken up into 4 infusion time blocks (eg, 8

Patient Education. Prior to administration of the monoclonal therapy, physician and nursing staff obtain a formal, written patient consent for therapy and provide patients with the option of participating in the institutional review board (IRB) approved study. Details of this are discussed in the risk management and IRB sections of the article. Nursing staff also provides the medication-specific Fact Sheet for Patients and Caregivers in either Spanish or English, which is also included as a hyperlink on the COVID-19 Monoclonal Antibody Order Set for ease of access. Interpreter services are available for patients who speak other languages. An ED decentralized pharmacist is also available onsite Monday through Friday from 12

Infusion Ordering. Once the patient is ready to begin therapy, the he/she is brought to a dedicated overflow area of the ED. There are few, if any, patients in this location, and it is adjacent to the main emergency center for easy access by the patients, nurses, pharmacists, and physicians. The physician then enters orders in the EHR using the COVID-19 Monoclonal Antibody Order Set (Figure 3). Three discrete questions were built into the medication order: (1) Was patient consent obtained? (2) Was the Fact Sheet for Patient/Caregiver provided to the patient? (3) Is the patient COVID-19 PCR-positive? These questions were built as hard stops so that the medication orders cannot be placed without a response. This serves as another double-check to ensure processes are followed and helps facilitate timely verification by the pharmacist.

Medication Administration. One nurse is dedicated to administering the monoclonal therapies scheduled at 8

Pharmacy Department

Medication Receipt Process. Inventory is currently allocated biweekly from the state department of health and will soon be transitioning to a direct order system. The pharmacy technician in charge of deliveries notifies the pharmacy Antimicrobial Stewardship Program (ASP) clinical coordinator upon receipt of the monoclonal therapies. Bamlanivimab is supplied as 1 vial per dose, whereas casirivimab/imdevimab is supplied as 4 vials or 8 vials per dose, depending how it is shipped. To reduce the likelihood of medication errors, the ASP clinical coordinator assembles each of the casirivimab/imdevimab vials into kits, where 1 kit equals 1 dose. Labels are then affixed to each kit indicating the medication name, number of vials which equal a full dose, and pharmacist signature. The kits are stored in a dedicated refrigerator, and inventory logs are affixed to the outside of the refrigerator and updated daily. This inventory is also communicated daily to ED physician, nursing, and pharmacy leadership, as well as the director of patient safety, who reports weekly usage to the state Department of Health and Human Services. These weekly reports are used to determine allocation amounts.

Medication Verification and Delivery. The Mount Sinai Medical Center pharmacist staffing model consists of centralized order entry and specialized, decentralized positions. All orders are verified by the ED pharmacist when scheduled (not a 24/7 service) and by the designated pharmacist for all other times. At the time of medication verification, the pharmacist documents patient-specific EUA criteria for use and confirms that consent was obtained and the Fact Sheet for Patients/Caregivers was provided. A pharmacist intervention was developed to assist with this documentation. Pharmacists input smart text “.COVIDmonoclonal” and a drop-down menu of EUA criteria for use appears. The pharmacist reviews the patient care notes and medication order question responses to ascertain this information, contacting the ED prescriber if further clarification is required. This verification serves as another check to ensure processes put in place are followed. Lastly, intravenous preparation and delivery are electronically recorded in the EHR, and the medications require nursing signature at the time of delivery to ensure a formal chain of custody.

Risk Management

At Mount Sinai Medical Center, all EUA and investigational therapies require patient consent. Consistent with this requirement, a COVID-19 monoclonal specific consent was developed by risk management. This is provided to every patient receiving a COVID-19 monoclonal infusion, in addition to the FDA EUA Fact Sheet for Patients and Caregivers, and documented as part of their EHR. The questions providers must answer are built into the order set to ensure this process is followed and these patient safety checks are incorporated into the workflow.

Billing and Finance Department

In alignment with Mount Sinai Medical Center’s mission to provide high-quality health care to its diverse community through teaching, research, charity care, and financial responsibility, it was determined that this therapy would be provided to all patients regardless of insurance type, including those who are uninsured. The billing and finance department was consulted prior to this service being offered, to provide patients with accurate and pertinent information. The billing and finance department provided guidance on how to document patient encounters at time of registration to facilitate appropriate billing. At this time, the medication is free of charge, but nonmedication-related ED fees apply. This is explained to patients so there is a clear understanding prior to booking their appointment.

Infection Prevention

As patients receiving COVID-19 monoclonal therapies can transmit the virus to others, measures to ensure protection for other patients and staff are vital. To minimize exposure, specific nursing and physician staff from the ED are assigned to the treatment of these patients, and patients receive infusions and postobservation monitoring in a designated wing of the ED. Additionally, all staff who interact with these patients are required to don full personal protective equipment. This includes not only physicians and nurses but all specialties such as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, and laboratory technicians. Moreover, patients are not permitted to go home in a ride share and are counseled on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention quarantining following infusion.

Measurement of Process and Outcomes and Reporting

IRB approval was sought and obtained early during initiation of this service, allowing study consent to be offered to patients at the time general consent was obtained, which maximized patient recruitment and streamlined workflow. The study is a prospective observational research study to determine the impact of administration of COVID-19 monoclonal antibody therapy on length of symptoms, chronic illness, and rate of hospitalization. Most patients were eager to participate and offer their assistance to the scientific community during this pandemic.

Staff Education

In order to successfully implement this multidisciplinary EUA treatment option, comprehensive staff education was paramount after the workflow was developed. Prior to the first day of infusions, nurses and pharmacists were provided education during multiple huddle announcements. The pharmacy team also provided screen captures via email to the pharmacists so they could become familiar with the order set, intervention documentation, and location of the preliminary assessment of EUA criteria for use at the time of order verification. The emergency medicine department chair and chief medical officer also provided education via several virtual meetings and email to referring physicians (specialists and primary care) and residents in the emergency centers involved in COVID-19 monoclonal therapy-related patient care.

Factors Contributing to Success

We believe the reasons for continued success of this process are multifactorial and include the following key elements. Multidisciplinary planning, which included decision makers and all stakeholders, began at the time the idea was conceived. This allowed quick implementation of this service by efficiently navigating barriers to engaging impacted staff early on. Throughout this process, the authors set realistic step-wise goals. While navigating through the many details to implementation described, we also kept in mind the big picture, which was to provide this potentially lifesaving therapy to as many qualifying members of our community as possible. This included being flexible with the process and adapting when needed to achieve this ultimate goal. A focus on safety remained a priority to minimize possible errors and enhance patient and staff satisfaction. The optimization of the EHR streamlined workflow, provided point-of-care resources, and enhanced patient safety. Additionally, the target date set for implementation allowed staff and department leads adequate time to plan for and anticipate the changes. Serving only 1 patient on the first day allowed time for staff to experience this new process hands-on and provided opportunity for focused education. This team communication was essential to implementing this project, including staff training of processes and procedures prior to go-live. Early incorporation of IRB approval allowed the experience to be assessed and considered for contribution to the scientific literature to tackle this novel virus that has impacted our communities locally, nationally, and abroad. Moreover, continued measurement and reporting on a regular basis leads to performance improvement. The process outlined here can be adapted to incorporate other new therapies in the future, such as the recent February 9, 2021, EUA of the COVID-19 monoclonal antibody combination bamlanivimab and etesevimab.10

Conclusion

We administered 790 COVID-19 monoclonal antibody infusions between November 20, 2020 and March 5, 2021. Steps to minimize the likelihood of hypersensitivity reactions were implemented, and a low incidence (< 1%) has been observed. There has been no incidence of infection, concern from staff about infection prevention, or risk of infection during the processes. There have been very infrequent cost-related concerns raised by patients, typically due to incomplete communication regarding billing prior to the infusion. To address these issues, staff education has been provided to enhance patient instruction on this topic. The program has provided patient and family satisfaction, as well nursing, physician, pharmacist, clinical staff, and hospital administration pride and gratification. Setting up a new program to provide a 4-hour patient encounter to infuse therapy to high-risk patients with COVID-19 requires commitment and effort. This article describes the experience, ideas, and formula others may consider using to set up such a program. Through networking and formal phone calls and meetings about monoclonal antibody therapy, we have heard about other institutions who have not been able to institute this program due to various barriers to implementation. We hope our experience serves as a resource for others to provide this therapy to their patients and expand access in an effort to mitigate COVID-19 consequences and cases affecting our communities.

Corresponding author: Kathleen Jodoin, PharmD, BCPS, Mount Sinai Medical Center, 4300 Alton Rd, Miami Beach, FL 33140; kathleen.jodoin@msmc.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. COVID Data Tracker. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#global-counts-rates. Accessed March 12, 2021.

2. Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of Bamlanivimab. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated February 2021. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/143603/download

3. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Monoclonal Antibodies for Treatment of COVID-19 | FDA. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-monoclonal-antibodies-treatment-covid-19. Accessed February 14, 2021.

4. Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of Casirivimab and Imdevimab. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated December 2020. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/143892/download

5. Chen P, Nirula A, Heller B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 in outpatients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(3):229-237. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2029849

6. Gottlieb RL, Nirula A, Chen P, et al. Effect of bamlanivimab as monotherapy or in combination with etesevimab on viral load in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. 10.1JAMA. 2021;325(7):632-644. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.0202

7. Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al. REGN-COV2, a neutralizing antibody cocktail, in outpatients with COVID-19. 10.1N Engl J Med. 2021;384:238-251. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2035002

8. Mulangu S, Dodd LE, Davey RT Jr, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of Ebola virus disease therapeutics. 10.1N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2293-2303. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1910993

9. Boyle, P. Can an experimental treatment keep COVID-19 patients out of hospitals? Association of American Medical Colleges. January 29, 2021. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/can-experimental-treatment-keep-covid-19-patients-out-hospitals

10. Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of Bamlanivimab and Etesevimab. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated February 2021. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/145802/download

From Mount Sinai Medical Center, Miami Beach, FL.

Abstract

Objective: To develop and implement a process for administering COVID-19 monoclonal antibody infusions for outpatients with mild or moderate COVID-19 at high risk for hospitalization, using multidisciplinary collaboration, US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance, and infection prevention standards.

Methods: When monoclonal antibody therapy became available for mild or moderate COVID-19 outpatients via Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), our institution sought to provide this therapy option to our patients. We describe the process for planning, implementing, and maintaining a successful program for administering novel therapies based on FDA guidance and infection prevention standards. Key components of our implementation process were multidisciplinary planning involving decision makers and stakeholders; setting realistic goals in the process; team communication; and measuring and reporting quality improvement on a regular basis.

Results: A total of 790 COVID-19 monoclonal antibody infusions were administered from November 20, 2020 to March 5, 2021. Steps to minimize the likelihood of adverse drug reactions were implemented and a low incidence (< 1%) has occurred. There has been no concern from staff regarding infection during the process. Rarely, patients have raised cost-related concerns, typically due to incomplete communication regarding billing prior to the infusion. Patients, families, nursing staff, physicians, pharmacy, and hospital administration have expressed satisfaction with the program.

Conclusion: This process can provide a template for other hospitals or health care delivery facilities to provide novel therapies to patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 in a safe and effective manner.

Keywords: COVID-19; monoclonal antibody; infusion; emergency use authorization.

SARS-CoV-2 and the disease it causes, COVID-19, have transformed from scientific vernacular to common household terms. It began with a cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown etiology in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, with physicians there reporting a novel coronavirus strain (2019-nCoV), now referred to as SARS-CoV-2. Rapid spread of this virus resulted in the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring an international public health emergency. Since this time, the virus has evolved into a worldwide pandemic. COVID-19 has dramatically impacted our society, resulting in more than 2.63 million global deaths as of this writing, of which more than 527,000 deaths have occurred in the United States.1 This novel virus has resulted in a flurry of literature, research, therapies, and collaboration across multiple disciplines in an effort to prevent, treat, and mitigate cases and complications of this disease.

On November 9, 2020, and November 21, 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued Emergency Use Authorizations (EUA) for 2 novel COVID-19 monoclonal therapies, bamlanivimab2-3 and casirivimab/imdevimab,3-4 respectively. The EUAs granted permission for these therapies to be administered for the treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 in adult and pediatric patients (≥ 12 years and weighing at least 40 kg) with positive results of direct SARS-CoV-2 viral testing and who are at high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19 and/or hospitalization. The therapies work by targeting the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and subsequent attachment to human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors. Clinical trial data leading to the EUA demonstrated a reduction in viral load, safe outcome, and most importantly, fewer hospitalization and emergency room visits, as compared to the placebo group.5-7 The use of monoclonal antibodies is not new and gained recognition during the Ebola crisis, when the monoclonal antibody to the Ebola virus showed a significant survival benefit.8 Providing monoclonal antibody therapy soon after symptom onset aligns with a shift from the onset of the pandemic to the current focus on the administration of pharmaceutical therapy early in the disease course. This shift prevents progression to severe COVID-19, with the goal of reducing patient mortality, hospitalizations, and strain on health care systems.

The availability of novel neutralizing monoclonal antibodies for COVID-19 led to discussions of how to incorporate these therapies as new options for patients. Our institution networked with colleagues from multiple disciplines to discuss processes and policies for the safe administration of the monoclonal antibody infusion therapies. Federal health leaders urge more use of monoclonal antibodies, but many hospitals have been unable to successfully implement infusions due to staff and logistical challenges.9 This article presents a viable process that hospitals can use to provide these novel therapies to outpatients with mild to moderate COVID-19.

The Mount Sinai Medical Center, Florida Experience

Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami Beach, Florida, is the largest private, independent, not-for-profit teaching hospital in South Florida, comprising 672 licensed beds and supporting 150,000 emergency department (ED) visits annually. Per the EUA criteria for use, COVID-19 monoclonal antibody therapies are not authorized for patients who are hospitalized or who require oxygen therapy due to COVID-19. Therefore, options for outpatient administration needed to be evaluated. Directly following the first EUA press release, a task force of key stakeholders was assembled to brainstorm and develop a process to offer this therapy to the community. A multidisciplinary task force with representation from the ED, nursing, primary care, hospital medicine, pharmacy, risk management, billing, information technology, infection prevention, and senior level leadership participated (Table).

The task force reviewed institutional outpatient locations to determine whether offering this service would be feasible (eg, ED, ambulatory care facilities, cancer center). The ED was selected because it would offer the largest array of appointment times to meet the community needs with around-the-clock availability. While Mount Sinai Medical Center offers care in 3 emergency center locations in Aventura, Hialeah, and Miami Beach, it was determined to initiate the infusions at the main campus center in Miami Beach only. The main campus affords an onsite pharmacy with suitable staffing to prepare the anticipated volume of infusions in a timely manner, as both therapies have short stabilities following preparation. Thus, it was decided that patients from freestanding emergency centers in Aventura and Hialeah would be moved to the Miami Beach ED location to receive therapy. Operating at a single site also allowed for more rapid implementation, monitoring, and ability to make modifications more easily. Discussions for the possible expansion of COVID-19 monoclonal antibody infusions at satellite locations are underway.

On November 20, 2020, 11 days after the formation of the multidisciplinary task force, the first COVID-19 monoclonal infusion was successfully administered. Figure 1 depicts the timeline from assessment to program implementation. Critical to implementation was the involvement of decision makers from all necessary departments early in the planning process to ensure that standard operating procedures were followed and that the patients, community, and organization had a positive experience. This allowed for simultaneous planning of electronic health record (Epic; EHR) builds, departmental workflows, and staff education, as described in the following section. Figure 2 shows the patient safety activities included in the implementation process.

Key Stakeholder Involvement and Workflow

On the day of bamlanivimab EUA release, email communication was shared among hospital leadership with details of the press release. Departments were quickly involved to initiate a task force to assess if and how this therapy could be offered at Mount Sinai Medical Center. The following sections explain the role of each stakeholder and their essential role to operationalize these novel EUA treatment options. The task force was organized and led by our chief medical officer and chief nursing officer.

Information Technology

Medication Ordering and Documentation EHR and Smart Pumps. Early in the pandemic, the antimicrobial stewardship (ASP) clinical coordinator became the designated point person for pharmacy assessment of novel COVID-19 therapies. As such, this pharmacist began reviewing the bamlanivimab and, later, the casirivimab/imdevimab EUA Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers. All necessary elements for the complete and safe ordering and dispensing of the medication were developed and reviewed by pharmacy administration and ED nursing leadership for input, prior to submitting to the information technology team for implementation. Building the COVID-19 monoclonal medication records into the EHR allowed for detailed direction (ie, administration and preparation instructions) to be consistently applied. The medication records were also built into hospital smart pumps so that nurses could access prepopulated, accurate volumes and infusion rates to minimize errors.

Order Set Development. The pharmacy medication build was added to a comprehensive order set (Figure 3), which was then developed to guide prescribers and standardize the process around ordering of COVID-19 monoclonal therapies. While these therapies are new, oncology monoclonal therapies are regularly administered to outpatients at Mount Sinai Cancer Center. The cancer center was therefore consulted on their process surrounding best practices in administration of monoclonal antibody therapies. This included protocols for medications used in pretreatment and management of hypersensitivity reactions and potential adverse drug reactions of both COVID-19 monoclonal therapies. These medication orders were selected by default in the order set to ensure that all patients received premedications aimed at minimizing the risk of hypersensitivity reaction, and had as-needed medication orders, in the event a hypersensitivity reaction occurred. Reducing hypersensitivity reaction risk is important as well to increase the likelihood that the patient would receive full therapy, as management of this adverse drug reactions involves possible cessation of therapy depending on the level of severity. The pharmacy department also ensured these medications were stocked in ED automated dispensing cabinets to promote quick access. In addition to the aforementioned nursing orders, we added EUA criteria for use and hyperlinks to the Fact Sheets for Patients and Caregivers and Health Care Providers for each monoclonal therapy, and restricted ordering to ED physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants.

The order set underwent multidisciplinary review by pharmacy administration, the chair of emergency medicine, physicians, and ED nursing leadership prior to presentation and approval by the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee. Lastly, at time of implementation, the order set was added to the ED preference list, preventing inpatient access. Additionally, as a patient safety action, free- standing orders of COVID-19 monoclonal therapies were disabled, so providers could only order therapies via the approved, comprehensive order set.

Preliminary Assessment Tool. A provider assessment tool was developed to document patient-specific EUA criteria for use during initial assessment (Figure 4). This tool serves as a checklist and is visible to the full multidisciplinary team in the patient’s EHR. It is used as a resource at the time of pharmacist verification and ED physician assessment to ensure criteria for use are met.

Outpatient Offices

Patient Referral. Patients with symptoms or concerns of COVID-19 exposure can make physician appointments via telemedicine or in person at Mount Sinai Medical Center’s primary care and specialty offices. At the time of patient encounter, physicians suspecting a COVID-19 diagnosis will refer patients for outpatient COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) laboratory testing, which has an approximate 24-hour turnaround to results. Physicians also assess whether the patient meets EUA criteria for use, pending results of testing. In the event a patient meets EUA criteria for use, the physician provides patient counseling and requests verbal consent. Following this, the physician enters a note in the EHR describing the patient’s condition, criteria for use evaluation, and the patient’s verbal agreement to therapy. This preliminary screening is beneficial to begin planning with both the patient and ED to minimize delays. Patients are notified of the results of their test once available. If the COVID-19 PCR test returns positive, the physician will call the ED at the main campus and schedule the patient for COVID-19 monoclonal therapy. As the desired timeframe for administering COVID-19 monoclonal therapies is within less than 10 days of symptom onset, timely scheduling of appointments is crucial. Infusion appointments are typically provided the same or next day. The patients are informed that they must bring documentation of their positive COVID-19 PCR test to their ED visit. Lastly, because patients are pretreated with medication that may potentially impair driving, they are instructed that they cannot drive themselves home; ride shares also are not allowed in order to limit the spread of infection.

Emergency Department

Patient Arrival and Screening. A COVID-19 patient can be evaluated in the ED 1 of 2 ways. The first option is via outpatient office referral, as described previously. Upon arrival to the ED, a second screening is performed to ensure the patient still meets EUA criteria for use and the positive COVID-19 PCR test result is confirmed. If the patient no longer meets criteria, the patient is triaged accordingly, including evaluation for higher-level care (eg, supplemental oxygen, hospital admission). The second optoion is via new patient walk-ins without outpatient physician referral (Figure 4). In these cases, an initial screening is performed, documenting EUA criteria for use in the preliminary assessment (Figure 5). Physicians will consider an outside COVID-19 test as valid, so long as documentation is readily available confirming a positive PCR result. Otherwise, an in-house COVID-19 PCR test will be performed, which has a 2-hour turnaround time.

Infusion Schedule. The ED offers a total of 16 COVID-19 monoclonal infusions slots daily. These are broken up into 4 infusion time blocks (eg, 8

Patient Education. Prior to administration of the monoclonal therapy, physician and nursing staff obtain a formal, written patient consent for therapy and provide patients with the option of participating in the institutional review board (IRB) approved study. Details of this are discussed in the risk management and IRB sections of the article. Nursing staff also provides the medication-specific Fact Sheet for Patients and Caregivers in either Spanish or English, which is also included as a hyperlink on the COVID-19 Monoclonal Antibody Order Set for ease of access. Interpreter services are available for patients who speak other languages. An ED decentralized pharmacist is also available onsite Monday through Friday from 12

Infusion Ordering. Once the patient is ready to begin therapy, the he/she is brought to a dedicated overflow area of the ED. There are few, if any, patients in this location, and it is adjacent to the main emergency center for easy access by the patients, nurses, pharmacists, and physicians. The physician then enters orders in the EHR using the COVID-19 Monoclonal Antibody Order Set (Figure 3). Three discrete questions were built into the medication order: (1) Was patient consent obtained? (2) Was the Fact Sheet for Patient/Caregiver provided to the patient? (3) Is the patient COVID-19 PCR-positive? These questions were built as hard stops so that the medication orders cannot be placed without a response. This serves as another double-check to ensure processes are followed and helps facilitate timely verification by the pharmacist.

Medication Administration. One nurse is dedicated to administering the monoclonal therapies scheduled at 8

Pharmacy Department

Medication Receipt Process. Inventory is currently allocated biweekly from the state department of health and will soon be transitioning to a direct order system. The pharmacy technician in charge of deliveries notifies the pharmacy Antimicrobial Stewardship Program (ASP) clinical coordinator upon receipt of the monoclonal therapies. Bamlanivimab is supplied as 1 vial per dose, whereas casirivimab/imdevimab is supplied as 4 vials or 8 vials per dose, depending how it is shipped. To reduce the likelihood of medication errors, the ASP clinical coordinator assembles each of the casirivimab/imdevimab vials into kits, where 1 kit equals 1 dose. Labels are then affixed to each kit indicating the medication name, number of vials which equal a full dose, and pharmacist signature. The kits are stored in a dedicated refrigerator, and inventory logs are affixed to the outside of the refrigerator and updated daily. This inventory is also communicated daily to ED physician, nursing, and pharmacy leadership, as well as the director of patient safety, who reports weekly usage to the state Department of Health and Human Services. These weekly reports are used to determine allocation amounts.

Medication Verification and Delivery. The Mount Sinai Medical Center pharmacist staffing model consists of centralized order entry and specialized, decentralized positions. All orders are verified by the ED pharmacist when scheduled (not a 24/7 service) and by the designated pharmacist for all other times. At the time of medication verification, the pharmacist documents patient-specific EUA criteria for use and confirms that consent was obtained and the Fact Sheet for Patients/Caregivers was provided. A pharmacist intervention was developed to assist with this documentation. Pharmacists input smart text “.COVIDmonoclonal” and a drop-down menu of EUA criteria for use appears. The pharmacist reviews the patient care notes and medication order question responses to ascertain this information, contacting the ED prescriber if further clarification is required. This verification serves as another check to ensure processes put in place are followed. Lastly, intravenous preparation and delivery are electronically recorded in the EHR, and the medications require nursing signature at the time of delivery to ensure a formal chain of custody.

Risk Management

At Mount Sinai Medical Center, all EUA and investigational therapies require patient consent. Consistent with this requirement, a COVID-19 monoclonal specific consent was developed by risk management. This is provided to every patient receiving a COVID-19 monoclonal infusion, in addition to the FDA EUA Fact Sheet for Patients and Caregivers, and documented as part of their EHR. The questions providers must answer are built into the order set to ensure this process is followed and these patient safety checks are incorporated into the workflow.

Billing and Finance Department

In alignment with Mount Sinai Medical Center’s mission to provide high-quality health care to its diverse community through teaching, research, charity care, and financial responsibility, it was determined that this therapy would be provided to all patients regardless of insurance type, including those who are uninsured. The billing and finance department was consulted prior to this service being offered, to provide patients with accurate and pertinent information. The billing and finance department provided guidance on how to document patient encounters at time of registration to facilitate appropriate billing. At this time, the medication is free of charge, but nonmedication-related ED fees apply. This is explained to patients so there is a clear understanding prior to booking their appointment.

Infection Prevention

As patients receiving COVID-19 monoclonal therapies can transmit the virus to others, measures to ensure protection for other patients and staff are vital. To minimize exposure, specific nursing and physician staff from the ED are assigned to the treatment of these patients, and patients receive infusions and postobservation monitoring in a designated wing of the ED. Additionally, all staff who interact with these patients are required to don full personal protective equipment. This includes not only physicians and nurses but all specialties such as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, and laboratory technicians. Moreover, patients are not permitted to go home in a ride share and are counseled on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention quarantining following infusion.

Measurement of Process and Outcomes and Reporting

IRB approval was sought and obtained early during initiation of this service, allowing study consent to be offered to patients at the time general consent was obtained, which maximized patient recruitment and streamlined workflow. The study is a prospective observational research study to determine the impact of administration of COVID-19 monoclonal antibody therapy on length of symptoms, chronic illness, and rate of hospitalization. Most patients were eager to participate and offer their assistance to the scientific community during this pandemic.

Staff Education

In order to successfully implement this multidisciplinary EUA treatment option, comprehensive staff education was paramount after the workflow was developed. Prior to the first day of infusions, nurses and pharmacists were provided education during multiple huddle announcements. The pharmacy team also provided screen captures via email to the pharmacists so they could become familiar with the order set, intervention documentation, and location of the preliminary assessment of EUA criteria for use at the time of order verification. The emergency medicine department chair and chief medical officer also provided education via several virtual meetings and email to referring physicians (specialists and primary care) and residents in the emergency centers involved in COVID-19 monoclonal therapy-related patient care.

Factors Contributing to Success

We believe the reasons for continued success of this process are multifactorial and include the following key elements. Multidisciplinary planning, which included decision makers and all stakeholders, began at the time the idea was conceived. This allowed quick implementation of this service by efficiently navigating barriers to engaging impacted staff early on. Throughout this process, the authors set realistic step-wise goals. While navigating through the many details to implementation described, we also kept in mind the big picture, which was to provide this potentially lifesaving therapy to as many qualifying members of our community as possible. This included being flexible with the process and adapting when needed to achieve this ultimate goal. A focus on safety remained a priority to minimize possible errors and enhance patient and staff satisfaction. The optimization of the EHR streamlined workflow, provided point-of-care resources, and enhanced patient safety. Additionally, the target date set for implementation allowed staff and department leads adequate time to plan for and anticipate the changes. Serving only 1 patient on the first day allowed time for staff to experience this new process hands-on and provided opportunity for focused education. This team communication was essential to implementing this project, including staff training of processes and procedures prior to go-live. Early incorporation of IRB approval allowed the experience to be assessed and considered for contribution to the scientific literature to tackle this novel virus that has impacted our communities locally, nationally, and abroad. Moreover, continued measurement and reporting on a regular basis leads to performance improvement. The process outlined here can be adapted to incorporate other new therapies in the future, such as the recent February 9, 2021, EUA of the COVID-19 monoclonal antibody combination bamlanivimab and etesevimab.10

Conclusion

We administered 790 COVID-19 monoclonal antibody infusions between November 20, 2020 and March 5, 2021. Steps to minimize the likelihood of hypersensitivity reactions were implemented, and a low incidence (< 1%) has been observed. There has been no incidence of infection, concern from staff about infection prevention, or risk of infection during the processes. There have been very infrequent cost-related concerns raised by patients, typically due to incomplete communication regarding billing prior to the infusion. To address these issues, staff education has been provided to enhance patient instruction on this topic. The program has provided patient and family satisfaction, as well nursing, physician, pharmacist, clinical staff, and hospital administration pride and gratification. Setting up a new program to provide a 4-hour patient encounter to infuse therapy to high-risk patients with COVID-19 requires commitment and effort. This article describes the experience, ideas, and formula others may consider using to set up such a program. Through networking and formal phone calls and meetings about monoclonal antibody therapy, we have heard about other institutions who have not been able to institute this program due to various barriers to implementation. We hope our experience serves as a resource for others to provide this therapy to their patients and expand access in an effort to mitigate COVID-19 consequences and cases affecting our communities.

Corresponding author: Kathleen Jodoin, PharmD, BCPS, Mount Sinai Medical Center, 4300 Alton Rd, Miami Beach, FL 33140; kathleen.jodoin@msmc.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

From Mount Sinai Medical Center, Miami Beach, FL.

Abstract

Objective: To develop and implement a process for administering COVID-19 monoclonal antibody infusions for outpatients with mild or moderate COVID-19 at high risk for hospitalization, using multidisciplinary collaboration, US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance, and infection prevention standards.

Methods: When monoclonal antibody therapy became available for mild or moderate COVID-19 outpatients via Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), our institution sought to provide this therapy option to our patients. We describe the process for planning, implementing, and maintaining a successful program for administering novel therapies based on FDA guidance and infection prevention standards. Key components of our implementation process were multidisciplinary planning involving decision makers and stakeholders; setting realistic goals in the process; team communication; and measuring and reporting quality improvement on a regular basis.

Results: A total of 790 COVID-19 monoclonal antibody infusions were administered from November 20, 2020 to March 5, 2021. Steps to minimize the likelihood of adverse drug reactions were implemented and a low incidence (< 1%) has occurred. There has been no concern from staff regarding infection during the process. Rarely, patients have raised cost-related concerns, typically due to incomplete communication regarding billing prior to the infusion. Patients, families, nursing staff, physicians, pharmacy, and hospital administration have expressed satisfaction with the program.

Conclusion: This process can provide a template for other hospitals or health care delivery facilities to provide novel therapies to patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 in a safe and effective manner.

Keywords: COVID-19; monoclonal antibody; infusion; emergency use authorization.

SARS-CoV-2 and the disease it causes, COVID-19, have transformed from scientific vernacular to common household terms. It began with a cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown etiology in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, with physicians there reporting a novel coronavirus strain (2019-nCoV), now referred to as SARS-CoV-2. Rapid spread of this virus resulted in the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring an international public health emergency. Since this time, the virus has evolved into a worldwide pandemic. COVID-19 has dramatically impacted our society, resulting in more than 2.63 million global deaths as of this writing, of which more than 527,000 deaths have occurred in the United States.1 This novel virus has resulted in a flurry of literature, research, therapies, and collaboration across multiple disciplines in an effort to prevent, treat, and mitigate cases and complications of this disease.