User login

Do Patients Benefit from Cancer Trial Participation?

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- The view that patients with cancer benefit from access to investigational drugs in the clinical trial setting is widely held but does necessarily align with trial findings, which often show limited evidence of a clinical benefit. First, most investigational treatments assessed in clinical trials fail to gain regulatory approval, and the minority that are approved tend to offer minimal clinical benefit, experts explained.

- To estimate the survival benefit and toxicities associated with receiving experimental treatments, researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 128 trials comprising 141 comparisons of an investigational drug and a control treatment, which included immunotherapies and targeted therapies.

- The analysis included 42 trials in non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), 37 in breast cancer, 15 in hepatobiliary cancer, 13 in pancreatic cancer, 12 in colorectal cancer, and 10 in prostate cancer, involving a total of 47,050 patients.

- The primary outcome was PFS and secondary outcomes were overall survival and grades 3-5 serious adverse events.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, the experimental treatment was associated with a 20% improvement in PFS (pooled hazard ratio [HR], 0.80), corresponding to a median 1.25-month PFS advantage. The PFS benefit was seen across all cancer types, except pancreatic cancer.

- Overall survival improved by 8% with experimental agents (HR, 0.92), corresponding to 1.18 additional months. A significant overall survival benefit was seen across NSCLC, breast cancer, and hepatobiliary cancer trials but not pancreatic, prostate, colorectal cancer trials.

- Patients in the experimental intervention group, however, experienced much higher risk for grade 3-5 serious adverse events (risk ratio [RR], 1.27), corresponding to 7.40% increase in absolute risk. The greater risk for serious adverse events was significant for all indications except prostate cancer (RR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.91-1.40).

IN PRACTICE:

“We believe our findings are best interpreted as suggesting that access to experimental interventions that have not yet received full FDA approval is associated with a marginal but nonzero clinical benefit,” the authors wrote.

“Although our findings seem to reflect poorly on trials as a vehicle for extending survival for participants, they have reassuring implications for clinical investigators, policymakers, and institutional review boards,” the researchers said, explaining that this “scenario allows clinical trials to continue to pursue promising new treatments — supporting incremental advances that sum to large gains over extended periods of research — without disadvantaging patients in comparator groups.”

SOURCE:

Renata Iskander, MSc, of McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, led this work, which was published online on April 29, 2024, in Annals of Internal Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

There was high heterogeneity across studies due to variations in drugs tested, comparators used, and populations involved. The use of comparators below standard care could have inflated survival benefits. Additionally, data collected from ClinicalTrials.gov might be biased due to some trials not being reported.

DISCLOSURES:

Canadian Institutes of Health Research supported this work. The authors received grants for this work from McGill University, Rossy Cancer Network, and National Science Foundation. One author received consulting fees outside this work. The other authors declared no competing interests.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- The view that patients with cancer benefit from access to investigational drugs in the clinical trial setting is widely held but does necessarily align with trial findings, which often show limited evidence of a clinical benefit. First, most investigational treatments assessed in clinical trials fail to gain regulatory approval, and the minority that are approved tend to offer minimal clinical benefit, experts explained.

- To estimate the survival benefit and toxicities associated with receiving experimental treatments, researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 128 trials comprising 141 comparisons of an investigational drug and a control treatment, which included immunotherapies and targeted therapies.

- The analysis included 42 trials in non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), 37 in breast cancer, 15 in hepatobiliary cancer, 13 in pancreatic cancer, 12 in colorectal cancer, and 10 in prostate cancer, involving a total of 47,050 patients.

- The primary outcome was PFS and secondary outcomes were overall survival and grades 3-5 serious adverse events.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, the experimental treatment was associated with a 20% improvement in PFS (pooled hazard ratio [HR], 0.80), corresponding to a median 1.25-month PFS advantage. The PFS benefit was seen across all cancer types, except pancreatic cancer.

- Overall survival improved by 8% with experimental agents (HR, 0.92), corresponding to 1.18 additional months. A significant overall survival benefit was seen across NSCLC, breast cancer, and hepatobiliary cancer trials but not pancreatic, prostate, colorectal cancer trials.

- Patients in the experimental intervention group, however, experienced much higher risk for grade 3-5 serious adverse events (risk ratio [RR], 1.27), corresponding to 7.40% increase in absolute risk. The greater risk for serious adverse events was significant for all indications except prostate cancer (RR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.91-1.40).

IN PRACTICE:

“We believe our findings are best interpreted as suggesting that access to experimental interventions that have not yet received full FDA approval is associated with a marginal but nonzero clinical benefit,” the authors wrote.

“Although our findings seem to reflect poorly on trials as a vehicle for extending survival for participants, they have reassuring implications for clinical investigators, policymakers, and institutional review boards,” the researchers said, explaining that this “scenario allows clinical trials to continue to pursue promising new treatments — supporting incremental advances that sum to large gains over extended periods of research — without disadvantaging patients in comparator groups.”

SOURCE:

Renata Iskander, MSc, of McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, led this work, which was published online on April 29, 2024, in Annals of Internal Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

There was high heterogeneity across studies due to variations in drugs tested, comparators used, and populations involved. The use of comparators below standard care could have inflated survival benefits. Additionally, data collected from ClinicalTrials.gov might be biased due to some trials not being reported.

DISCLOSURES:

Canadian Institutes of Health Research supported this work. The authors received grants for this work from McGill University, Rossy Cancer Network, and National Science Foundation. One author received consulting fees outside this work. The other authors declared no competing interests.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- The view that patients with cancer benefit from access to investigational drugs in the clinical trial setting is widely held but does necessarily align with trial findings, which often show limited evidence of a clinical benefit. First, most investigational treatments assessed in clinical trials fail to gain regulatory approval, and the minority that are approved tend to offer minimal clinical benefit, experts explained.

- To estimate the survival benefit and toxicities associated with receiving experimental treatments, researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 128 trials comprising 141 comparisons of an investigational drug and a control treatment, which included immunotherapies and targeted therapies.

- The analysis included 42 trials in non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), 37 in breast cancer, 15 in hepatobiliary cancer, 13 in pancreatic cancer, 12 in colorectal cancer, and 10 in prostate cancer, involving a total of 47,050 patients.

- The primary outcome was PFS and secondary outcomes were overall survival and grades 3-5 serious adverse events.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, the experimental treatment was associated with a 20% improvement in PFS (pooled hazard ratio [HR], 0.80), corresponding to a median 1.25-month PFS advantage. The PFS benefit was seen across all cancer types, except pancreatic cancer.

- Overall survival improved by 8% with experimental agents (HR, 0.92), corresponding to 1.18 additional months. A significant overall survival benefit was seen across NSCLC, breast cancer, and hepatobiliary cancer trials but not pancreatic, prostate, colorectal cancer trials.

- Patients in the experimental intervention group, however, experienced much higher risk for grade 3-5 serious adverse events (risk ratio [RR], 1.27), corresponding to 7.40% increase in absolute risk. The greater risk for serious adverse events was significant for all indications except prostate cancer (RR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.91-1.40).

IN PRACTICE:

“We believe our findings are best interpreted as suggesting that access to experimental interventions that have not yet received full FDA approval is associated with a marginal but nonzero clinical benefit,” the authors wrote.

“Although our findings seem to reflect poorly on trials as a vehicle for extending survival for participants, they have reassuring implications for clinical investigators, policymakers, and institutional review boards,” the researchers said, explaining that this “scenario allows clinical trials to continue to pursue promising new treatments — supporting incremental advances that sum to large gains over extended periods of research — without disadvantaging patients in comparator groups.”

SOURCE:

Renata Iskander, MSc, of McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, led this work, which was published online on April 29, 2024, in Annals of Internal Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

There was high heterogeneity across studies due to variations in drugs tested, comparators used, and populations involved. The use of comparators below standard care could have inflated survival benefits. Additionally, data collected from ClinicalTrials.gov might be biased due to some trials not being reported.

DISCLOSURES:

Canadian Institutes of Health Research supported this work. The authors received grants for this work from McGill University, Rossy Cancer Network, and National Science Foundation. One author received consulting fees outside this work. The other authors declared no competing interests.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Do Health-Related Social Needs Raise Mortality Risk in Cancer Survivors?

Little is known about the specific association between health-related social needs (HRSNs) and mortality risk even though HRSNs, defined as challenges in affording food, housing, and other necessities of daily living, are potential challenges for cancer survivors, wrote Zhiyuan Zheng, PhD, of the American Cancer Society, Atlanta, and colleagues.

A 2020 study by Dr. Zheng and colleagues published in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) showed that food insecurity and financial worries had a negative impact on cancer survivorship. In the new study, published in Cancer, the researchers identified cancer survivors using the 2013-2018 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and the NHIS Mortality File through December 31, 2019. The researchers examined mortality using the data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Death Index (NDI) through December 31, 2019, which links to the National Health Interview Survey Data used in the study.

Individuals’ HRSNs were categorized into three groups: severe, moderate, and minor/none. HRSNs included food insecurity and nonmedical financial concerns, such as housing costs (rent, mortgage). Medical financial hardship included material, psychological, and behavioral domains and was divided into three groups: 2-3 domains, 1 domain, or 0 domains.

What Are the Potential Financial Implications of this Research?

The high costs of cancer care often cause medical financial hardships for cancer survivors, and expenses also may cause psychological distress and nonmedical financial hardship as survivors try to make ends meet while facing medical bills, wrote Dr. Zheng and colleagues.

Policy makers are increasingly interested in adding HRSNs to insurance coverage; recent guidance from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) allows individual states to apply to provide nutrition and housing supports through state Medicaid programs, according to authors of a 2023 article published in JAMA Health Forum.

The new study adds to the understanding of how HRSNs impact people with cancer by examining the association with mortality risk, Yelak Biru, MSc, president and chief executive officer of the International Myeloma Foundation, said in an interview.

“This is a key area of study for addressing the disparities in treatments and outcomes that result in inequities,” said Mr. Biru, a patient advocate and multiple myeloma survivor who was not involved in the study.

What Does the New Study Show?

The new study characterized HRSNs in 5,855 adult cancer survivors aged 18-64 years and 5,918 aged 65-79 years. In the 18- to 64-year-old group, 25.5% reported moderate levels of HRSNs, and 18.3% reported severe HRSNs. In patients aged 65-79 years, 15.6% and 6.6% reported moderate HRSNs and severe HRSNs, respectively.

Severe HRSN was significantly associated with higher mortality risk in an adjusted analysis in patients aged 18-64 years (hazard ratio 2.00, P < .001).

Among adults aged 65-79 years, severe HRSN was not associated with higher mortality risk; however, in this older age group, those with 2-3 domains of medical financial hardship had significantly increased mortality risk compared with adults aged 65-79 years with zero domains of medical financial hardship (HR 1.58, P = .007).

Although the findings that HRSNs were associated with increased mortality risk, especially in the younger group, were not surprising, they serve as a call to action to address how HRSNs are contributing to cancer mortality, Mr. Biru said in an interview. “HRSNs, like food or housing insecurity, can lead to patients being unable to undergo the best treatment approach for their cancer,” he said.

What Are the Limitations and Research Gaps?

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of self-reports to measure medical financial hardship, food insecurity, and nonmedical financial concerns in the NHIS, the researchers wrote in their discussion. More research with longer follow-up time beyond 1-5 years is needed, wrote Dr. Zheng and colleagues.

Studies also are needed to illustrate how patient navigation can help prevent patients from falling through the cracks with regard to social needs and financial hardships, Mr. Biru told this news organization.

Other areas for research include how addressing social needs affects health outcomes and whether programs designed to address social needs are effective, he said.

“Finally, qualitative research is needed to capture the lived experiences of cancer survivors facing these challenges. This knowledge can inform the development of more patient-centered interventions and policies that effectively address the social determinants of health and improve overall outcomes for all cancer survivors,” Mr. Biru said.

What Is the Takeaway Message for Clinicians?

HRSNs and financial hardship are significantly associated with increased risk of mortality in adult cancer survivors, Dr. Zheng and colleagues concluded. Looking ahead, comprehensive assessment of HRSNs and financial hardship may help clinicians connect patients with relevant services to mitigate the social and financial impacts of cancer, they wrote.

“The takeaway message for oncologists in practice is that addressing [HRSNs] and financial hardship is crucial for providing comprehensive and equitable cancer care,” Mr. Biru said during his interview.

“The impact of social determinants of health on cancer outcomes cannot be ignored, and oncologists play a vital role in identifying and addressing these needs,” he said. Sensitive, discussion-based screenings are needed to identify core needs such as food and transportation, but clinicians also can consider broader social factors and work with a team to connect patients to appropriate resources, he added.

“By recognizing the importance of HRSN screening and taking proactive steps to address these needs, oncologists can contribute to improving health outcomes, reducing healthcare disparities, and providing more equitable cancer care for their patients,” he said.

What Other Guidance Is Available?

“High-quality cancer care requires treating the whole person; measuring and addressing anything in their life that could result in poorer health outcomes is a key component of comprehensive care,” Mr. Biru emphasized.

In September 2023, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) convened a working group cochaired by Mr. Biru that developed recommendations for how oncology practices should routinely measure HRSNs (NCCN.org/social-needs).

“The working group proposed that every cancer patient be assessed for food, transportation access, and financial and housing security at least once a year, and be reassessed at every care transition point as well,” Mr. Biru said. Such screenings should include follow-up to connect patients with services to address any HRSNs they are experiencing, he added.

Lead author Dr. Zheng is employed by the American Cancer Society, which as a nonprofit receives funds from the public through fundraising and contributions, as well as some support from corporations and industry to support its mission programs and services. Mr. Biru had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Little is known about the specific association between health-related social needs (HRSNs) and mortality risk even though HRSNs, defined as challenges in affording food, housing, and other necessities of daily living, are potential challenges for cancer survivors, wrote Zhiyuan Zheng, PhD, of the American Cancer Society, Atlanta, and colleagues.

A 2020 study by Dr. Zheng and colleagues published in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) showed that food insecurity and financial worries had a negative impact on cancer survivorship. In the new study, published in Cancer, the researchers identified cancer survivors using the 2013-2018 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and the NHIS Mortality File through December 31, 2019. The researchers examined mortality using the data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Death Index (NDI) through December 31, 2019, which links to the National Health Interview Survey Data used in the study.

Individuals’ HRSNs were categorized into three groups: severe, moderate, and minor/none. HRSNs included food insecurity and nonmedical financial concerns, such as housing costs (rent, mortgage). Medical financial hardship included material, psychological, and behavioral domains and was divided into three groups: 2-3 domains, 1 domain, or 0 domains.

What Are the Potential Financial Implications of this Research?

The high costs of cancer care often cause medical financial hardships for cancer survivors, and expenses also may cause psychological distress and nonmedical financial hardship as survivors try to make ends meet while facing medical bills, wrote Dr. Zheng and colleagues.

Policy makers are increasingly interested in adding HRSNs to insurance coverage; recent guidance from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) allows individual states to apply to provide nutrition and housing supports through state Medicaid programs, according to authors of a 2023 article published in JAMA Health Forum.

The new study adds to the understanding of how HRSNs impact people with cancer by examining the association with mortality risk, Yelak Biru, MSc, president and chief executive officer of the International Myeloma Foundation, said in an interview.

“This is a key area of study for addressing the disparities in treatments and outcomes that result in inequities,” said Mr. Biru, a patient advocate and multiple myeloma survivor who was not involved in the study.

What Does the New Study Show?

The new study characterized HRSNs in 5,855 adult cancer survivors aged 18-64 years and 5,918 aged 65-79 years. In the 18- to 64-year-old group, 25.5% reported moderate levels of HRSNs, and 18.3% reported severe HRSNs. In patients aged 65-79 years, 15.6% and 6.6% reported moderate HRSNs and severe HRSNs, respectively.

Severe HRSN was significantly associated with higher mortality risk in an adjusted analysis in patients aged 18-64 years (hazard ratio 2.00, P < .001).

Among adults aged 65-79 years, severe HRSN was not associated with higher mortality risk; however, in this older age group, those with 2-3 domains of medical financial hardship had significantly increased mortality risk compared with adults aged 65-79 years with zero domains of medical financial hardship (HR 1.58, P = .007).

Although the findings that HRSNs were associated with increased mortality risk, especially in the younger group, were not surprising, they serve as a call to action to address how HRSNs are contributing to cancer mortality, Mr. Biru said in an interview. “HRSNs, like food or housing insecurity, can lead to patients being unable to undergo the best treatment approach for their cancer,” he said.

What Are the Limitations and Research Gaps?

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of self-reports to measure medical financial hardship, food insecurity, and nonmedical financial concerns in the NHIS, the researchers wrote in their discussion. More research with longer follow-up time beyond 1-5 years is needed, wrote Dr. Zheng and colleagues.

Studies also are needed to illustrate how patient navigation can help prevent patients from falling through the cracks with regard to social needs and financial hardships, Mr. Biru told this news organization.

Other areas for research include how addressing social needs affects health outcomes and whether programs designed to address social needs are effective, he said.

“Finally, qualitative research is needed to capture the lived experiences of cancer survivors facing these challenges. This knowledge can inform the development of more patient-centered interventions and policies that effectively address the social determinants of health and improve overall outcomes for all cancer survivors,” Mr. Biru said.

What Is the Takeaway Message for Clinicians?

HRSNs and financial hardship are significantly associated with increased risk of mortality in adult cancer survivors, Dr. Zheng and colleagues concluded. Looking ahead, comprehensive assessment of HRSNs and financial hardship may help clinicians connect patients with relevant services to mitigate the social and financial impacts of cancer, they wrote.

“The takeaway message for oncologists in practice is that addressing [HRSNs] and financial hardship is crucial for providing comprehensive and equitable cancer care,” Mr. Biru said during his interview.

“The impact of social determinants of health on cancer outcomes cannot be ignored, and oncologists play a vital role in identifying and addressing these needs,” he said. Sensitive, discussion-based screenings are needed to identify core needs such as food and transportation, but clinicians also can consider broader social factors and work with a team to connect patients to appropriate resources, he added.

“By recognizing the importance of HRSN screening and taking proactive steps to address these needs, oncologists can contribute to improving health outcomes, reducing healthcare disparities, and providing more equitable cancer care for their patients,” he said.

What Other Guidance Is Available?

“High-quality cancer care requires treating the whole person; measuring and addressing anything in their life that could result in poorer health outcomes is a key component of comprehensive care,” Mr. Biru emphasized.

In September 2023, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) convened a working group cochaired by Mr. Biru that developed recommendations for how oncology practices should routinely measure HRSNs (NCCN.org/social-needs).

“The working group proposed that every cancer patient be assessed for food, transportation access, and financial and housing security at least once a year, and be reassessed at every care transition point as well,” Mr. Biru said. Such screenings should include follow-up to connect patients with services to address any HRSNs they are experiencing, he added.

Lead author Dr. Zheng is employed by the American Cancer Society, which as a nonprofit receives funds from the public through fundraising and contributions, as well as some support from corporations and industry to support its mission programs and services. Mr. Biru had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Little is known about the specific association between health-related social needs (HRSNs) and mortality risk even though HRSNs, defined as challenges in affording food, housing, and other necessities of daily living, are potential challenges for cancer survivors, wrote Zhiyuan Zheng, PhD, of the American Cancer Society, Atlanta, and colleagues.

A 2020 study by Dr. Zheng and colleagues published in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) showed that food insecurity and financial worries had a negative impact on cancer survivorship. In the new study, published in Cancer, the researchers identified cancer survivors using the 2013-2018 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and the NHIS Mortality File through December 31, 2019. The researchers examined mortality using the data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Death Index (NDI) through December 31, 2019, which links to the National Health Interview Survey Data used in the study.

Individuals’ HRSNs were categorized into three groups: severe, moderate, and minor/none. HRSNs included food insecurity and nonmedical financial concerns, such as housing costs (rent, mortgage). Medical financial hardship included material, psychological, and behavioral domains and was divided into three groups: 2-3 domains, 1 domain, or 0 domains.

What Are the Potential Financial Implications of this Research?

The high costs of cancer care often cause medical financial hardships for cancer survivors, and expenses also may cause psychological distress and nonmedical financial hardship as survivors try to make ends meet while facing medical bills, wrote Dr. Zheng and colleagues.

Policy makers are increasingly interested in adding HRSNs to insurance coverage; recent guidance from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) allows individual states to apply to provide nutrition and housing supports through state Medicaid programs, according to authors of a 2023 article published in JAMA Health Forum.

The new study adds to the understanding of how HRSNs impact people with cancer by examining the association with mortality risk, Yelak Biru, MSc, president and chief executive officer of the International Myeloma Foundation, said in an interview.

“This is a key area of study for addressing the disparities in treatments and outcomes that result in inequities,” said Mr. Biru, a patient advocate and multiple myeloma survivor who was not involved in the study.

What Does the New Study Show?

The new study characterized HRSNs in 5,855 adult cancer survivors aged 18-64 years and 5,918 aged 65-79 years. In the 18- to 64-year-old group, 25.5% reported moderate levels of HRSNs, and 18.3% reported severe HRSNs. In patients aged 65-79 years, 15.6% and 6.6% reported moderate HRSNs and severe HRSNs, respectively.

Severe HRSN was significantly associated with higher mortality risk in an adjusted analysis in patients aged 18-64 years (hazard ratio 2.00, P < .001).

Among adults aged 65-79 years, severe HRSN was not associated with higher mortality risk; however, in this older age group, those with 2-3 domains of medical financial hardship had significantly increased mortality risk compared with adults aged 65-79 years with zero domains of medical financial hardship (HR 1.58, P = .007).

Although the findings that HRSNs were associated with increased mortality risk, especially in the younger group, were not surprising, they serve as a call to action to address how HRSNs are contributing to cancer mortality, Mr. Biru said in an interview. “HRSNs, like food or housing insecurity, can lead to patients being unable to undergo the best treatment approach for their cancer,” he said.

What Are the Limitations and Research Gaps?

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of self-reports to measure medical financial hardship, food insecurity, and nonmedical financial concerns in the NHIS, the researchers wrote in their discussion. More research with longer follow-up time beyond 1-5 years is needed, wrote Dr. Zheng and colleagues.

Studies also are needed to illustrate how patient navigation can help prevent patients from falling through the cracks with regard to social needs and financial hardships, Mr. Biru told this news organization.

Other areas for research include how addressing social needs affects health outcomes and whether programs designed to address social needs are effective, he said.

“Finally, qualitative research is needed to capture the lived experiences of cancer survivors facing these challenges. This knowledge can inform the development of more patient-centered interventions and policies that effectively address the social determinants of health and improve overall outcomes for all cancer survivors,” Mr. Biru said.

What Is the Takeaway Message for Clinicians?

HRSNs and financial hardship are significantly associated with increased risk of mortality in adult cancer survivors, Dr. Zheng and colleagues concluded. Looking ahead, comprehensive assessment of HRSNs and financial hardship may help clinicians connect patients with relevant services to mitigate the social and financial impacts of cancer, they wrote.

“The takeaway message for oncologists in practice is that addressing [HRSNs] and financial hardship is crucial for providing comprehensive and equitable cancer care,” Mr. Biru said during his interview.

“The impact of social determinants of health on cancer outcomes cannot be ignored, and oncologists play a vital role in identifying and addressing these needs,” he said. Sensitive, discussion-based screenings are needed to identify core needs such as food and transportation, but clinicians also can consider broader social factors and work with a team to connect patients to appropriate resources, he added.

“By recognizing the importance of HRSN screening and taking proactive steps to address these needs, oncologists can contribute to improving health outcomes, reducing healthcare disparities, and providing more equitable cancer care for their patients,” he said.

What Other Guidance Is Available?

“High-quality cancer care requires treating the whole person; measuring and addressing anything in their life that could result in poorer health outcomes is a key component of comprehensive care,” Mr. Biru emphasized.

In September 2023, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) convened a working group cochaired by Mr. Biru that developed recommendations for how oncology practices should routinely measure HRSNs (NCCN.org/social-needs).

“The working group proposed that every cancer patient be assessed for food, transportation access, and financial and housing security at least once a year, and be reassessed at every care transition point as well,” Mr. Biru said. Such screenings should include follow-up to connect patients with services to address any HRSNs they are experiencing, he added.

Lead author Dr. Zheng is employed by the American Cancer Society, which as a nonprofit receives funds from the public through fundraising and contributions, as well as some support from corporations and industry to support its mission programs and services. Mr. Biru had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM CANCER

Terminal Cancer: What Matters to Patients and Caregivers

New research found that patients and caregivers both tend to prioritize symptom control over life extension but often preferring a balance. Patients and caregivers, however, are less aligned on decisions about cost containment, with patients more likely to prioritize cost containment.

“Our research has revealed that patients and caregivers generally share similar end-of-life goals,” with a “notable exception” when it comes to costs, first author Semra Ozdemir, PhD, with the Lien Centre for Palliative Care, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, told this news organization.

However, when patients and caregivers have a better understanding of the patient’s prognosis, both may be more inclined to avoid costly life-extending treatments and prioritize symptom management.

In other words, the survey suggests that “knowing the prognosis helps patients and their families set realistic expectations for care and adequately prepare for end-of-life decisions,” said Dr. Ozdemir.

This study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Patients with advanced cancer often face difficult decisions: Do they opt for treatments that may — or may not — extend life or do they focus more on symptom control?

Family caregivers, who also play an important role in this decision-making process, may have different care goals. Some research suggests that caregivers tend to prioritize treatments that could extend life, whereas patients prioritize symptom management, but it’s less clear how these priorities may change over time and how patients and caregivers may influence each other.

In the current study, the researchers examined goals of care among patients with stage IV solid tumors and caregivers during the last 2 years of life, focusing on life extension vs symptom management and cost containment, as well as how these goals changed over time.

The survey included 210 patient-caregiver pairs, recruited from outpatient clinics at two major cancer centers in Singapore. Patients had a mean age of 63 years, and about half were men. The caregivers had a mean age of 49 years, and almost two third (63%) were women.

Overall, 34% patients and 29% caregivers prioritized symptom management over life extension, whereas 24% patients and 19% caregivers prioritized life extension. Most patients and caregivers preferred balancing the two, with 34%-47% patients and 37%-69% caregivers supporting this approach.

When balancing cost and treatment decisions, however, patients were more likely to prioritize containing costs — 28% vs 17% for caregivers — over extending life — 26% of patients vs 35% of caregivers.

Cost containment tended to be more of a priority for older patients, those with a higher symptom burden, and those with less family caregiver support. For caregivers, cost containment was more of a priority for those who reported that caregiving had a big impact on their finances, those with worse self-esteem related to their caregiving abilities, as well as those caring for older patients.

To better align cost containment priorities between patients and caregivers, it’s essential for families to engage in open and thorough discussions about the allocation of resources, Dr. Ozdemir said.

Although “patients, families, and physicians often avoid discussions about prognosis,” such conversations are essential for setting realistic expectations for care and adequately preparing for end-of-life decisions, Dr. Ozdemir told this news organization.

“These conversations should aim to balance competing interests and create care plans that are mutually acceptable to both patients and caregivers,” she said, adding that “this approach will help in minimizing any potential conflicts and ensure that both parties feel respected and understood in their decision-making process.”

Managing Unrealistic Expectations

As patients approached the end of life, neither patients nor caregivers shifted their priorities from life extension to symptom management.

This finding raises concerns because it suggests that many patients hold unrealistic expectations regarding their care and “underscores the need for continuous dialogue and reassessment of care goals throughout the progression of illness,” Dr. Ozdemir said.

“This stability in preferences over time suggests that initial care decisions are deeply ingrained or that there may be a lack of ongoing communication about evolving care needs and possibilities as conditions change,” Ozdemir said.

Yet, it can be hard to define what unrealistic expectations mean, said Olivia Seecof, MD, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“I think people are hopeful that a devastating diagnosis won’t lead to the end of their life and that there will be a treatment or something that will change [their prognosis], and they’ll get better,” said Dr. Seecof, palliative care expert with the Supportive Oncology Program at NYU Langone Health’s Perlmutter Cancer Center in New York City.

Giving patients and caregivers a realistic understanding of the prognosis is important, but “there’s more to it than just telling the patient their diagnosis,” she said.

“We have to plan for end of life, what it can look like,” said Dr. Seecof, adding that “often we don’t do a very good job of talking about that early on in an illness course.”

Overall, though, Dr. Seecof stressed that no two patients or situations are the same, and it’s important to understand what’s important in each scenario. End-of-life care requires “an individual approach because every patient is different, even if they have the same diagnosis as someone else,” she said.

This work was supported by funding from the Singapore Millennium Foundation and the Lien Centre for Palliative Care. Dr. Ozdemir and Dr. Seecof had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New research found that patients and caregivers both tend to prioritize symptom control over life extension but often preferring a balance. Patients and caregivers, however, are less aligned on decisions about cost containment, with patients more likely to prioritize cost containment.

“Our research has revealed that patients and caregivers generally share similar end-of-life goals,” with a “notable exception” when it comes to costs, first author Semra Ozdemir, PhD, with the Lien Centre for Palliative Care, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, told this news organization.

However, when patients and caregivers have a better understanding of the patient’s prognosis, both may be more inclined to avoid costly life-extending treatments and prioritize symptom management.

In other words, the survey suggests that “knowing the prognosis helps patients and their families set realistic expectations for care and adequately prepare for end-of-life decisions,” said Dr. Ozdemir.

This study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Patients with advanced cancer often face difficult decisions: Do they opt for treatments that may — or may not — extend life or do they focus more on symptom control?

Family caregivers, who also play an important role in this decision-making process, may have different care goals. Some research suggests that caregivers tend to prioritize treatments that could extend life, whereas patients prioritize symptom management, but it’s less clear how these priorities may change over time and how patients and caregivers may influence each other.

In the current study, the researchers examined goals of care among patients with stage IV solid tumors and caregivers during the last 2 years of life, focusing on life extension vs symptom management and cost containment, as well as how these goals changed over time.

The survey included 210 patient-caregiver pairs, recruited from outpatient clinics at two major cancer centers in Singapore. Patients had a mean age of 63 years, and about half were men. The caregivers had a mean age of 49 years, and almost two third (63%) were women.

Overall, 34% patients and 29% caregivers prioritized symptom management over life extension, whereas 24% patients and 19% caregivers prioritized life extension. Most patients and caregivers preferred balancing the two, with 34%-47% patients and 37%-69% caregivers supporting this approach.

When balancing cost and treatment decisions, however, patients were more likely to prioritize containing costs — 28% vs 17% for caregivers — over extending life — 26% of patients vs 35% of caregivers.

Cost containment tended to be more of a priority for older patients, those with a higher symptom burden, and those with less family caregiver support. For caregivers, cost containment was more of a priority for those who reported that caregiving had a big impact on their finances, those with worse self-esteem related to their caregiving abilities, as well as those caring for older patients.

To better align cost containment priorities between patients and caregivers, it’s essential for families to engage in open and thorough discussions about the allocation of resources, Dr. Ozdemir said.

Although “patients, families, and physicians often avoid discussions about prognosis,” such conversations are essential for setting realistic expectations for care and adequately preparing for end-of-life decisions, Dr. Ozdemir told this news organization.

“These conversations should aim to balance competing interests and create care plans that are mutually acceptable to both patients and caregivers,” she said, adding that “this approach will help in minimizing any potential conflicts and ensure that both parties feel respected and understood in their decision-making process.”

Managing Unrealistic Expectations

As patients approached the end of life, neither patients nor caregivers shifted their priorities from life extension to symptom management.

This finding raises concerns because it suggests that many patients hold unrealistic expectations regarding their care and “underscores the need for continuous dialogue and reassessment of care goals throughout the progression of illness,” Dr. Ozdemir said.

“This stability in preferences over time suggests that initial care decisions are deeply ingrained or that there may be a lack of ongoing communication about evolving care needs and possibilities as conditions change,” Ozdemir said.

Yet, it can be hard to define what unrealistic expectations mean, said Olivia Seecof, MD, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“I think people are hopeful that a devastating diagnosis won’t lead to the end of their life and that there will be a treatment or something that will change [their prognosis], and they’ll get better,” said Dr. Seecof, palliative care expert with the Supportive Oncology Program at NYU Langone Health’s Perlmutter Cancer Center in New York City.

Giving patients and caregivers a realistic understanding of the prognosis is important, but “there’s more to it than just telling the patient their diagnosis,” she said.

“We have to plan for end of life, what it can look like,” said Dr. Seecof, adding that “often we don’t do a very good job of talking about that early on in an illness course.”

Overall, though, Dr. Seecof stressed that no two patients or situations are the same, and it’s important to understand what’s important in each scenario. End-of-life care requires “an individual approach because every patient is different, even if they have the same diagnosis as someone else,” she said.

This work was supported by funding from the Singapore Millennium Foundation and the Lien Centre for Palliative Care. Dr. Ozdemir and Dr. Seecof had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New research found that patients and caregivers both tend to prioritize symptom control over life extension but often preferring a balance. Patients and caregivers, however, are less aligned on decisions about cost containment, with patients more likely to prioritize cost containment.

“Our research has revealed that patients and caregivers generally share similar end-of-life goals,” with a “notable exception” when it comes to costs, first author Semra Ozdemir, PhD, with the Lien Centre for Palliative Care, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, told this news organization.

However, when patients and caregivers have a better understanding of the patient’s prognosis, both may be more inclined to avoid costly life-extending treatments and prioritize symptom management.

In other words, the survey suggests that “knowing the prognosis helps patients and their families set realistic expectations for care and adequately prepare for end-of-life decisions,” said Dr. Ozdemir.

This study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Patients with advanced cancer often face difficult decisions: Do they opt for treatments that may — or may not — extend life or do they focus more on symptom control?

Family caregivers, who also play an important role in this decision-making process, may have different care goals. Some research suggests that caregivers tend to prioritize treatments that could extend life, whereas patients prioritize symptom management, but it’s less clear how these priorities may change over time and how patients and caregivers may influence each other.

In the current study, the researchers examined goals of care among patients with stage IV solid tumors and caregivers during the last 2 years of life, focusing on life extension vs symptom management and cost containment, as well as how these goals changed over time.

The survey included 210 patient-caregiver pairs, recruited from outpatient clinics at two major cancer centers in Singapore. Patients had a mean age of 63 years, and about half were men. The caregivers had a mean age of 49 years, and almost two third (63%) were women.

Overall, 34% patients and 29% caregivers prioritized symptom management over life extension, whereas 24% patients and 19% caregivers prioritized life extension. Most patients and caregivers preferred balancing the two, with 34%-47% patients and 37%-69% caregivers supporting this approach.

When balancing cost and treatment decisions, however, patients were more likely to prioritize containing costs — 28% vs 17% for caregivers — over extending life — 26% of patients vs 35% of caregivers.

Cost containment tended to be more of a priority for older patients, those with a higher symptom burden, and those with less family caregiver support. For caregivers, cost containment was more of a priority for those who reported that caregiving had a big impact on their finances, those with worse self-esteem related to their caregiving abilities, as well as those caring for older patients.

To better align cost containment priorities between patients and caregivers, it’s essential for families to engage in open and thorough discussions about the allocation of resources, Dr. Ozdemir said.

Although “patients, families, and physicians often avoid discussions about prognosis,” such conversations are essential for setting realistic expectations for care and adequately preparing for end-of-life decisions, Dr. Ozdemir told this news organization.

“These conversations should aim to balance competing interests and create care plans that are mutually acceptable to both patients and caregivers,” she said, adding that “this approach will help in minimizing any potential conflicts and ensure that both parties feel respected and understood in their decision-making process.”

Managing Unrealistic Expectations

As patients approached the end of life, neither patients nor caregivers shifted their priorities from life extension to symptom management.

This finding raises concerns because it suggests that many patients hold unrealistic expectations regarding their care and “underscores the need for continuous dialogue and reassessment of care goals throughout the progression of illness,” Dr. Ozdemir said.

“This stability in preferences over time suggests that initial care decisions are deeply ingrained or that there may be a lack of ongoing communication about evolving care needs and possibilities as conditions change,” Ozdemir said.

Yet, it can be hard to define what unrealistic expectations mean, said Olivia Seecof, MD, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“I think people are hopeful that a devastating diagnosis won’t lead to the end of their life and that there will be a treatment or something that will change [their prognosis], and they’ll get better,” said Dr. Seecof, palliative care expert with the Supportive Oncology Program at NYU Langone Health’s Perlmutter Cancer Center in New York City.

Giving patients and caregivers a realistic understanding of the prognosis is important, but “there’s more to it than just telling the patient their diagnosis,” she said.

“We have to plan for end of life, what it can look like,” said Dr. Seecof, adding that “often we don’t do a very good job of talking about that early on in an illness course.”

Overall, though, Dr. Seecof stressed that no two patients or situations are the same, and it’s important to understand what’s important in each scenario. End-of-life care requires “an individual approach because every patient is different, even if they have the same diagnosis as someone else,” she said.

This work was supported by funding from the Singapore Millennium Foundation and the Lien Centre for Palliative Care. Dr. Ozdemir and Dr. Seecof had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Care for Patients With Skin Cancer

To the Editor:

The most common malignancy in the United States is skin cancer, with melanoma accounting for the majority of skin cancer deaths.1 Despite the lack of established guidelines for routine total-body skin examinations, many patients regularly visit their dermatologist for assessment of pigmented skin lesions.2 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients were unable to attend in-person dermatology visits, which resulted in many high-risk individuals not receiving care or alternatively seeking virtual care for cutaneous lesions.3 There has been a lack of research in the United States exploring the utilization of teledermatology during the pandemic and its overall impact on the care of patients with a history of skin cancer. We explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with skin cancer in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2020-2021 National Health Interview Survey,4 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with a self-reported history of skin cancer—melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, or unknown skin cancer. The 3 outcome variables included having a virtual medical appointment in the past 12 months (yes/no), delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no). Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between a history of skin cancer and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17.0 (StataCorp LLC). We controlled for patient age; education; race/ethnicity; received public assistance or welfare payments; sex; region; US citizenship status; health insurance status; comorbidities including history of hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia; and birthplace in the United States in the logistic regression models.

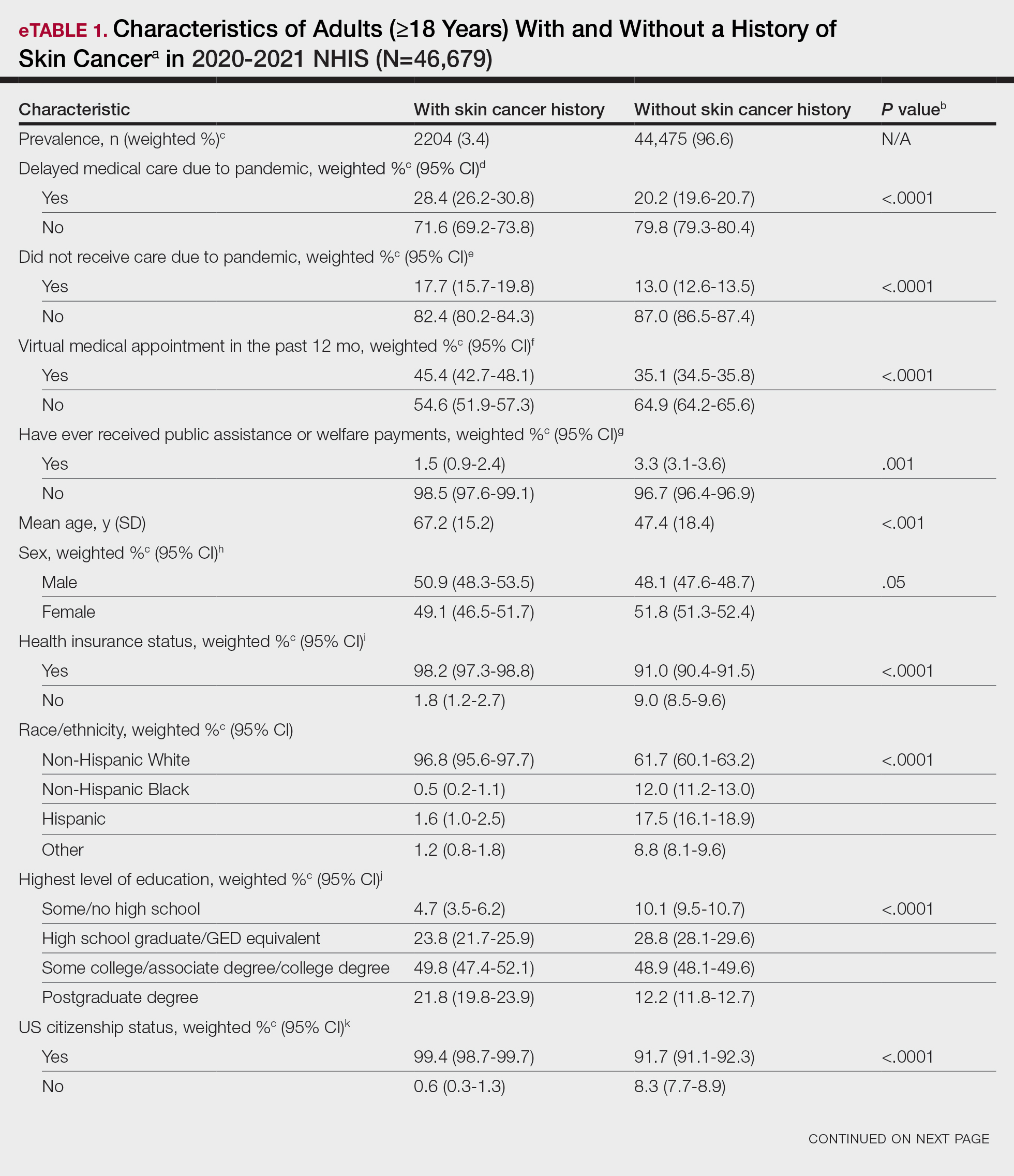

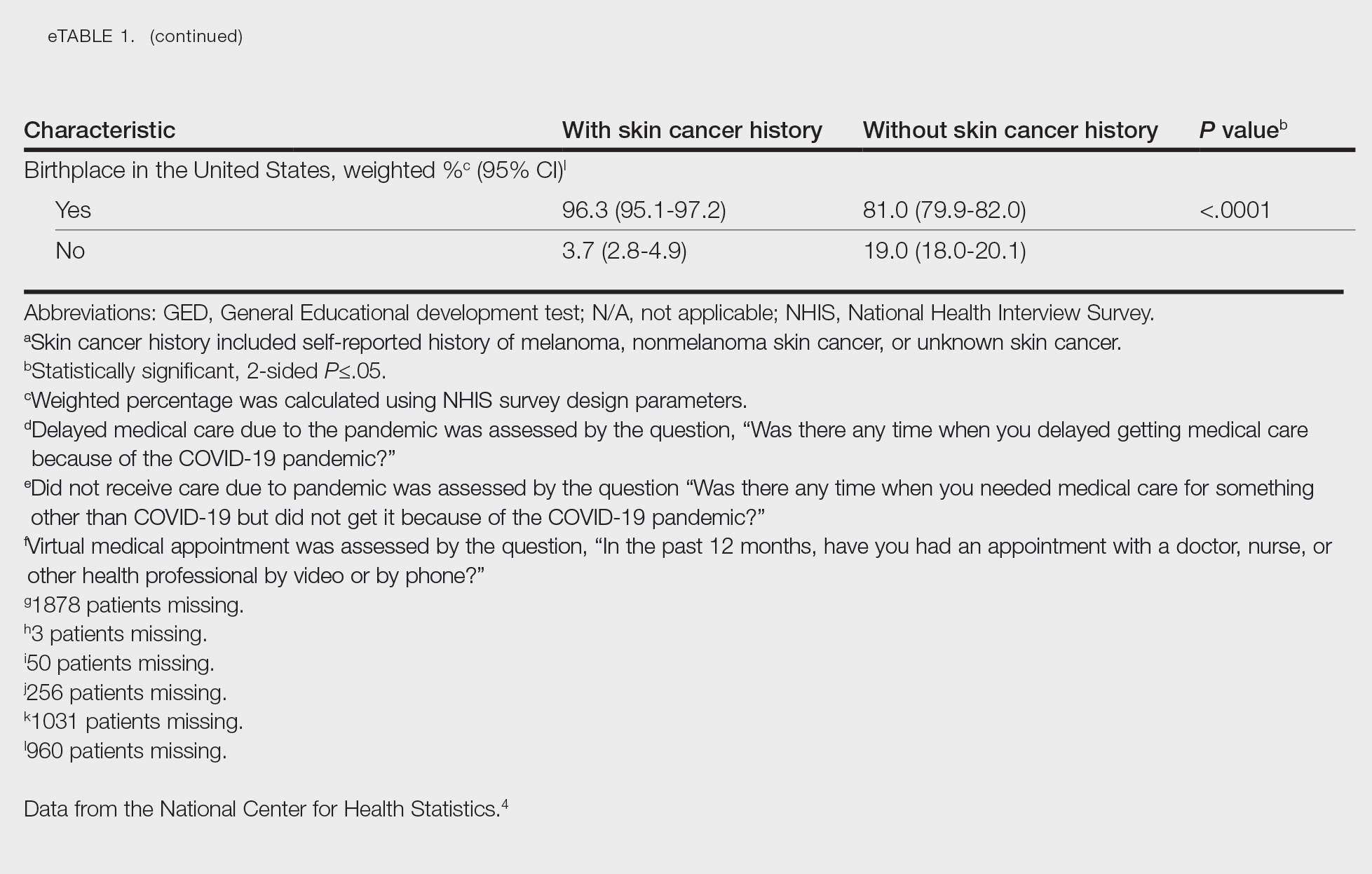

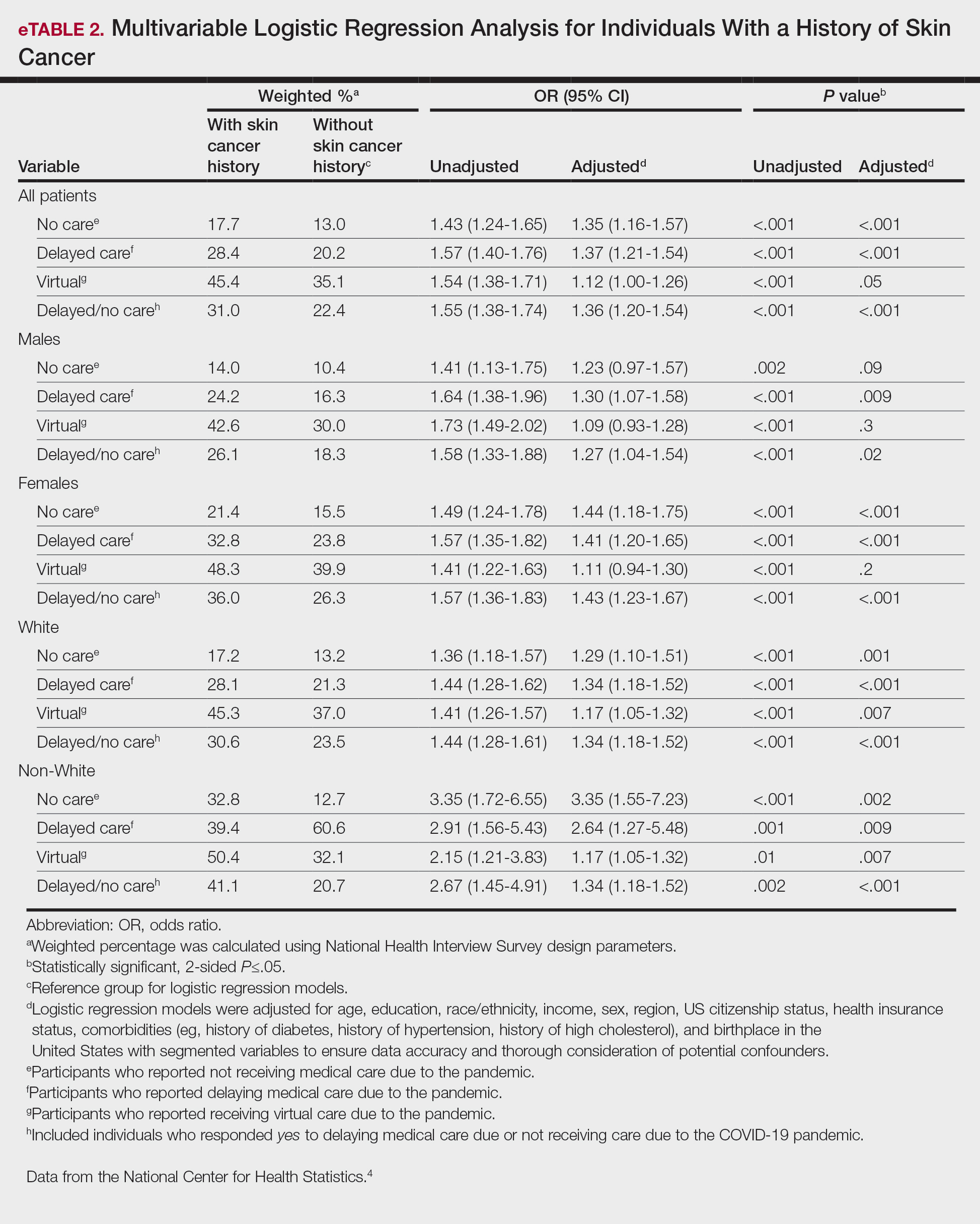

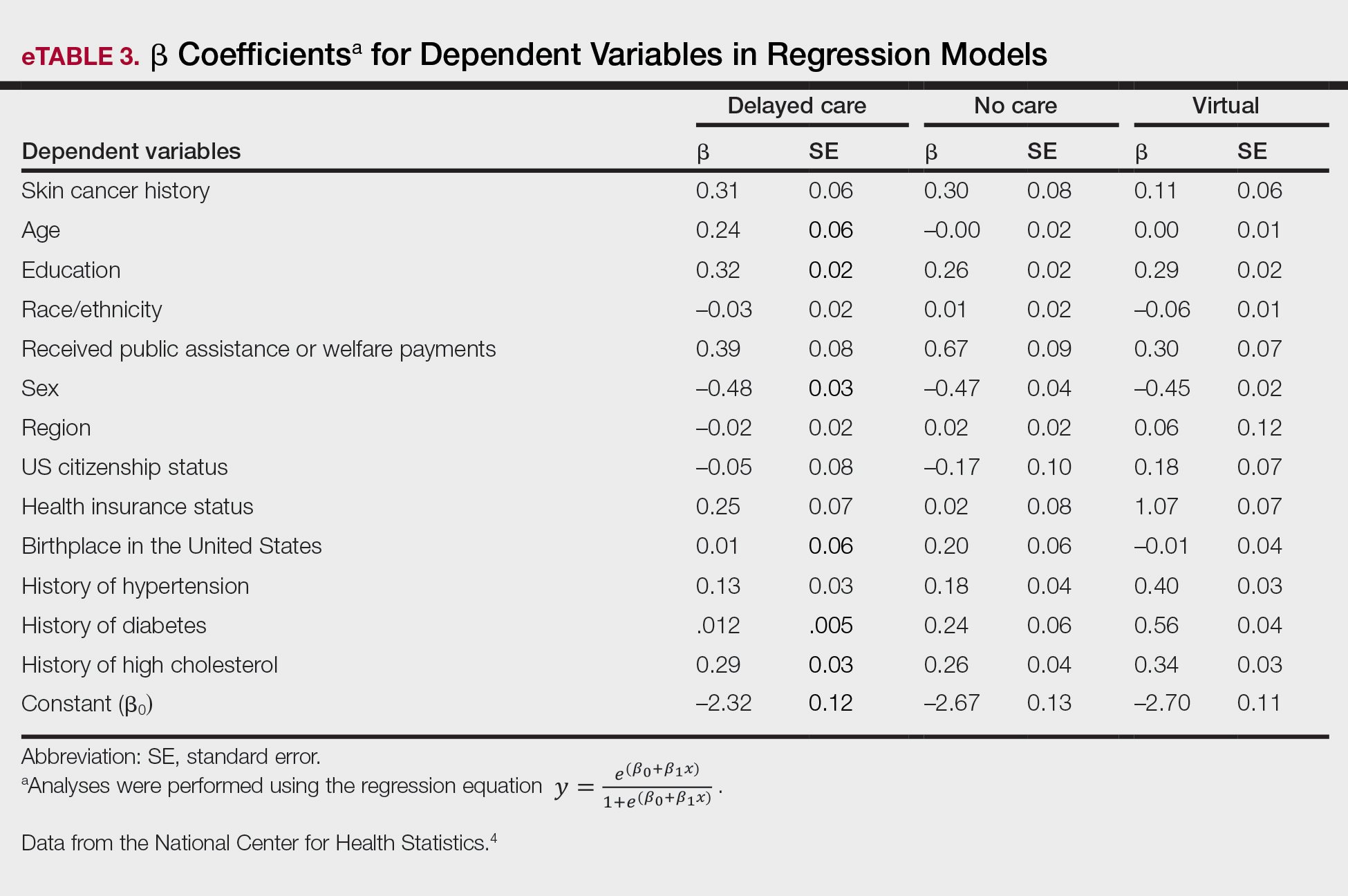

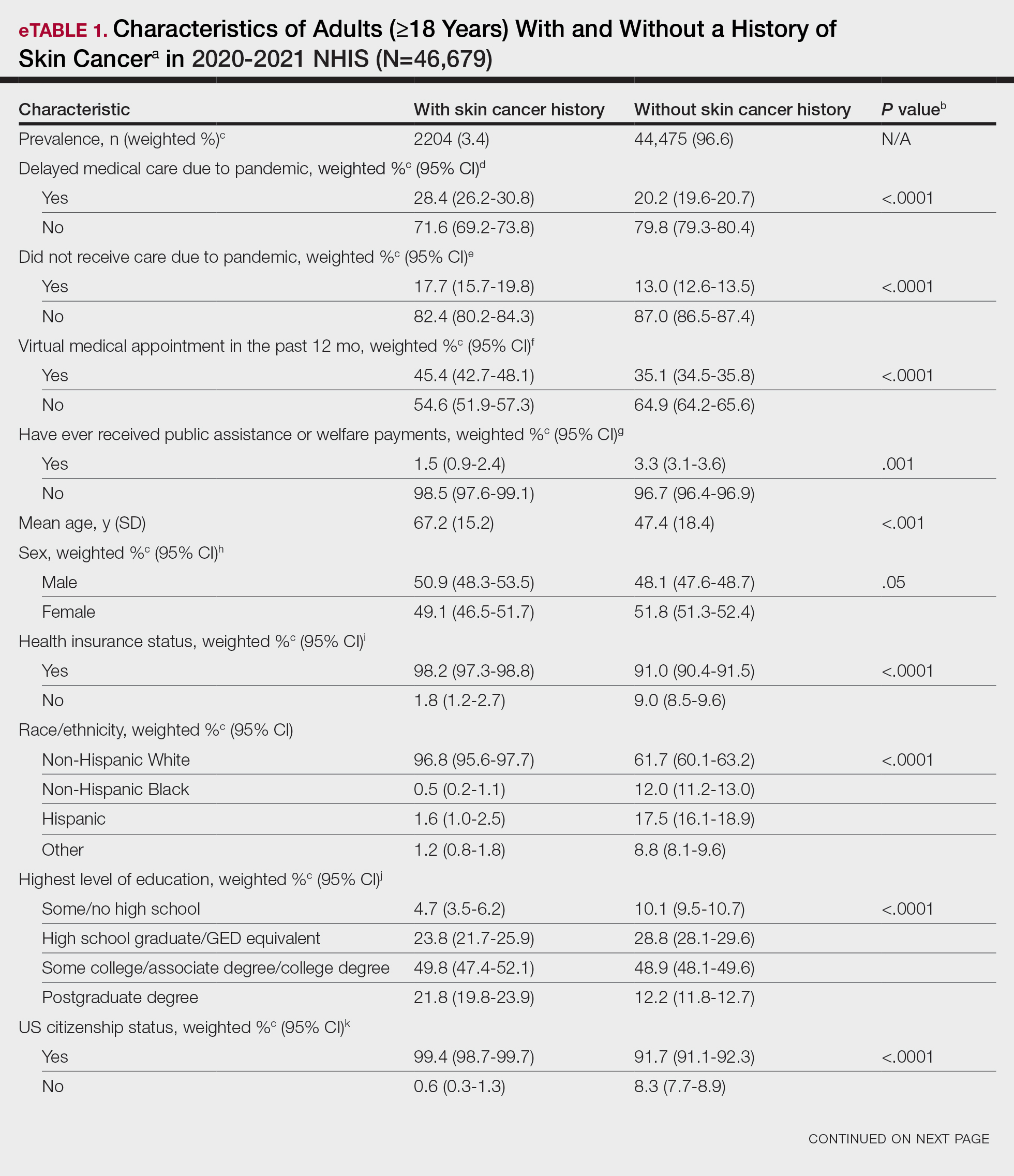

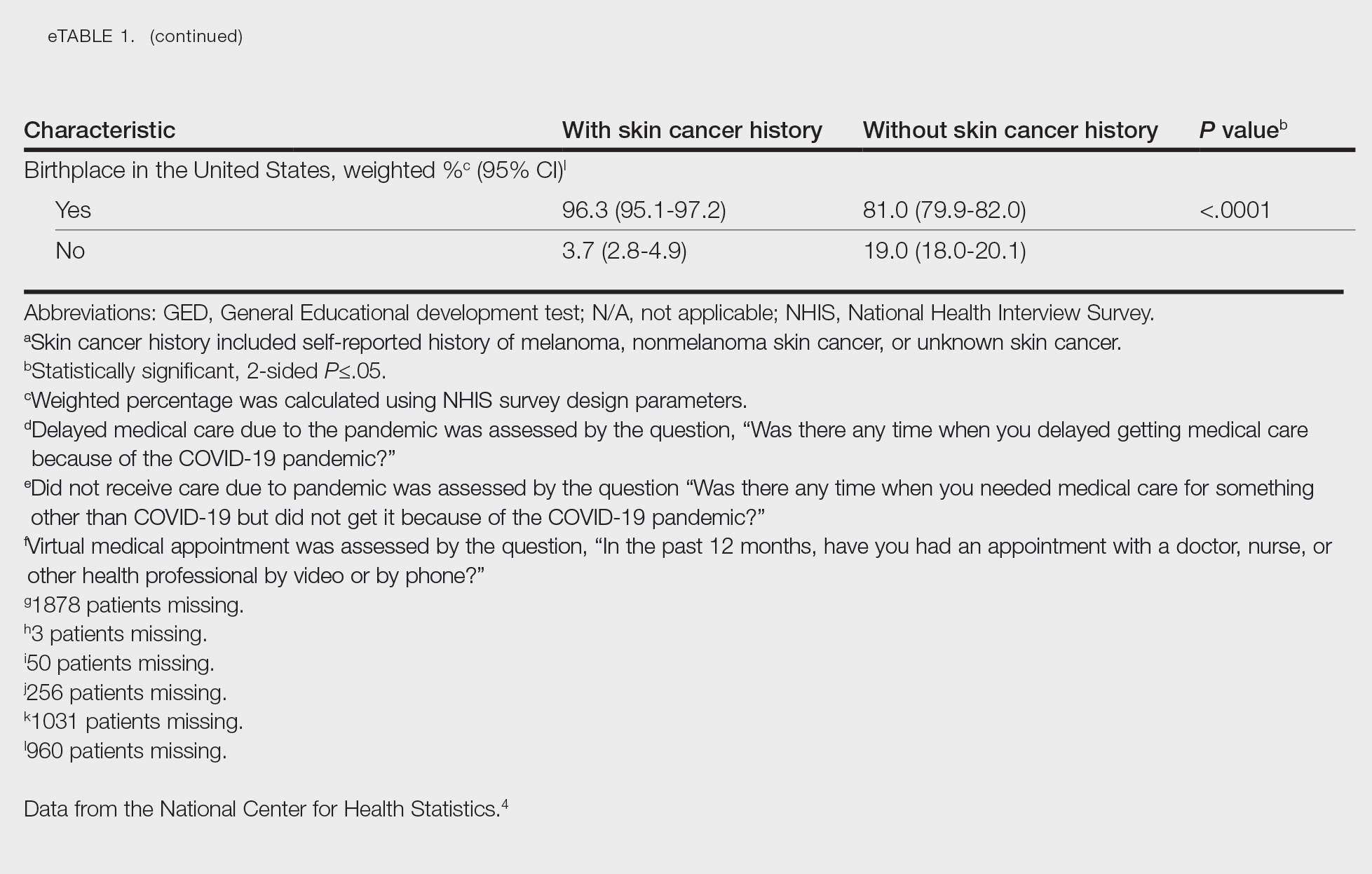

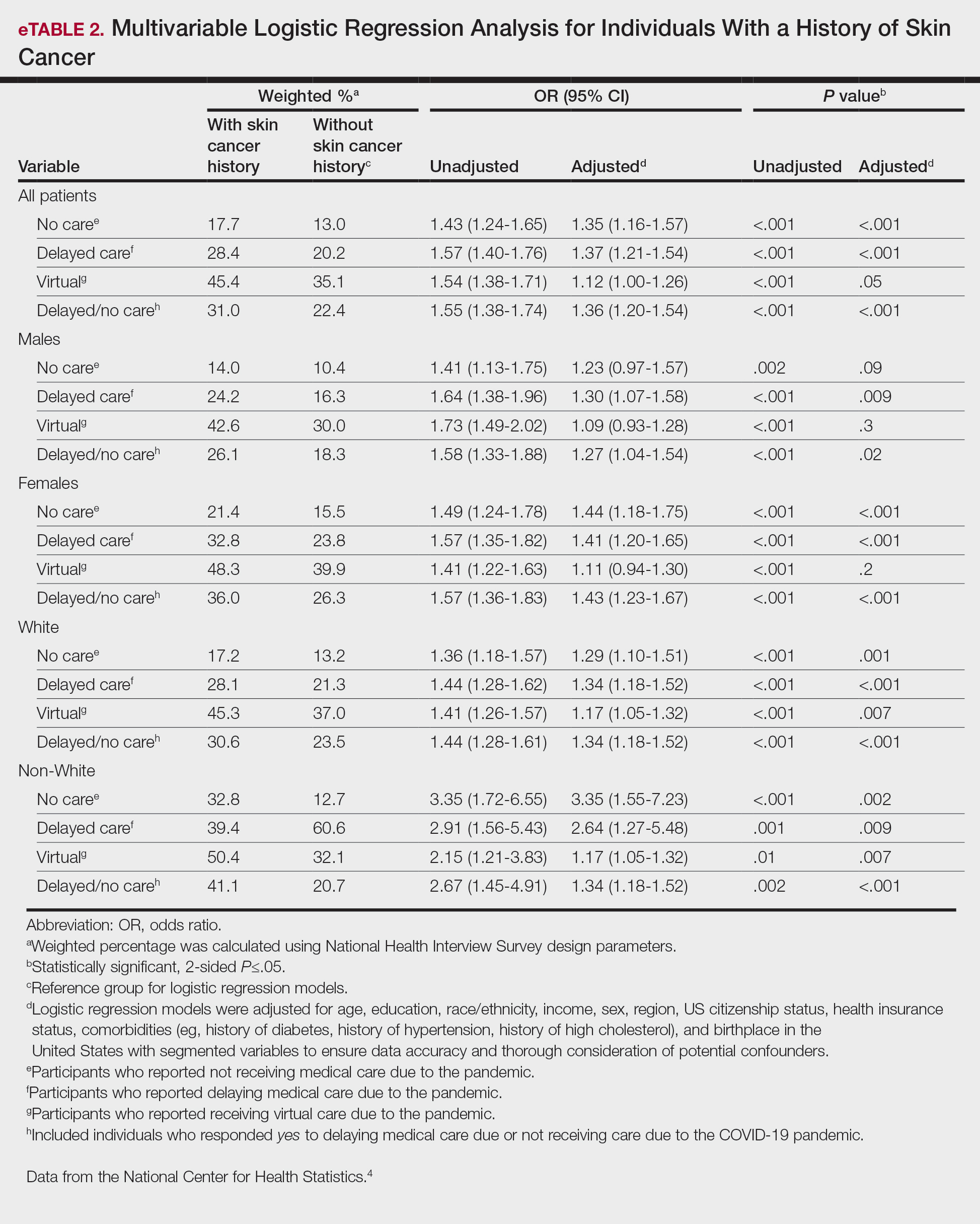

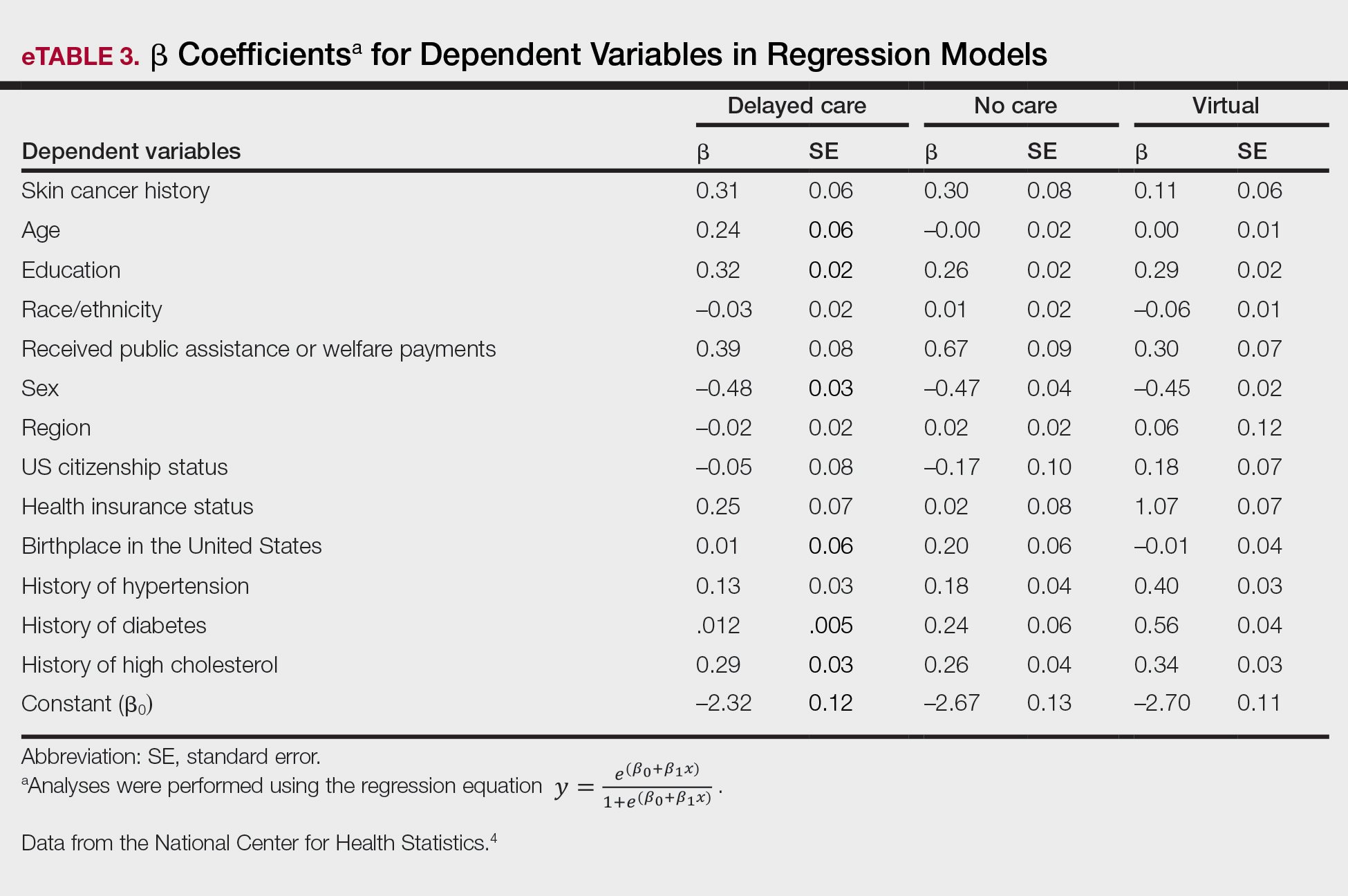

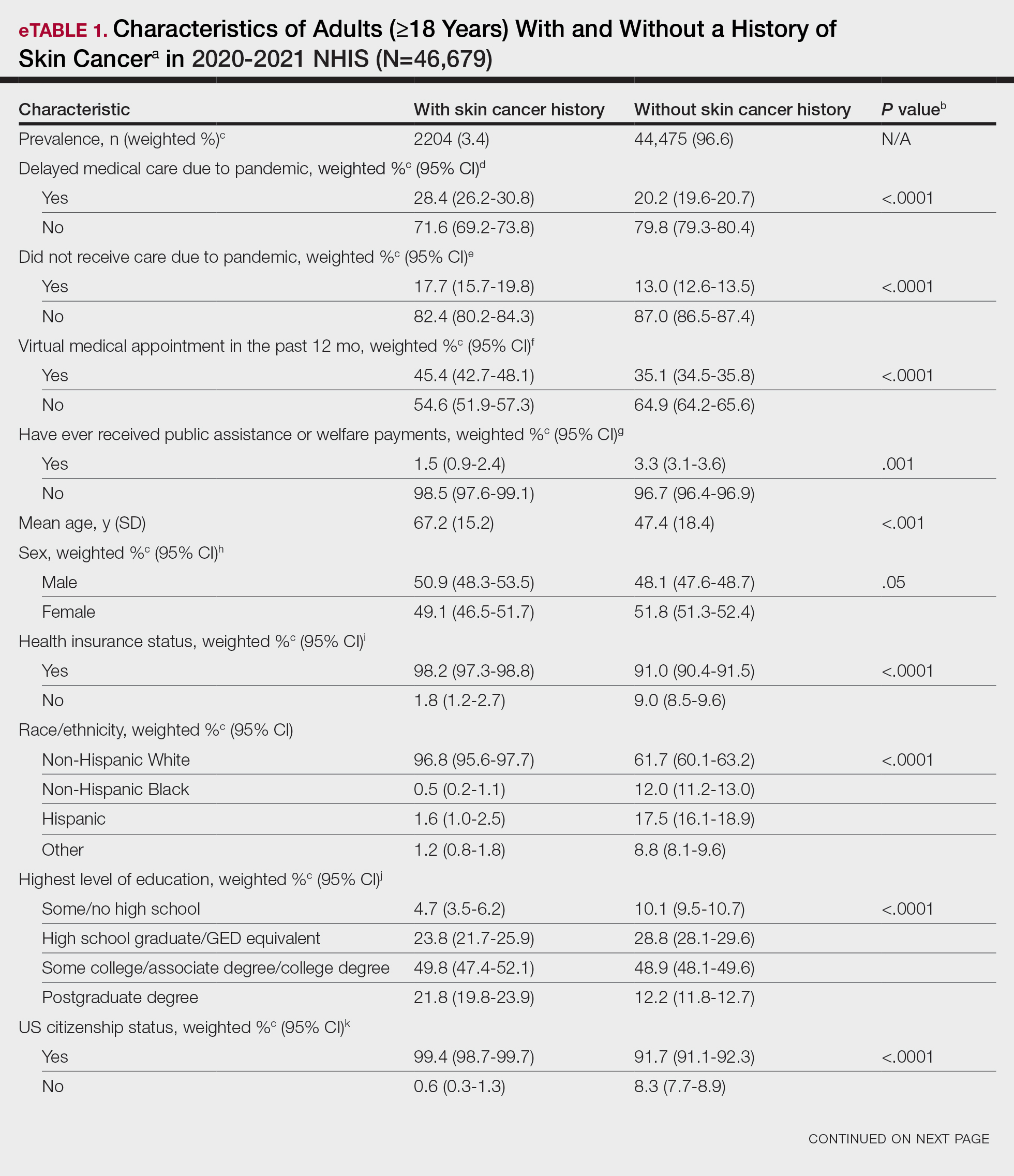

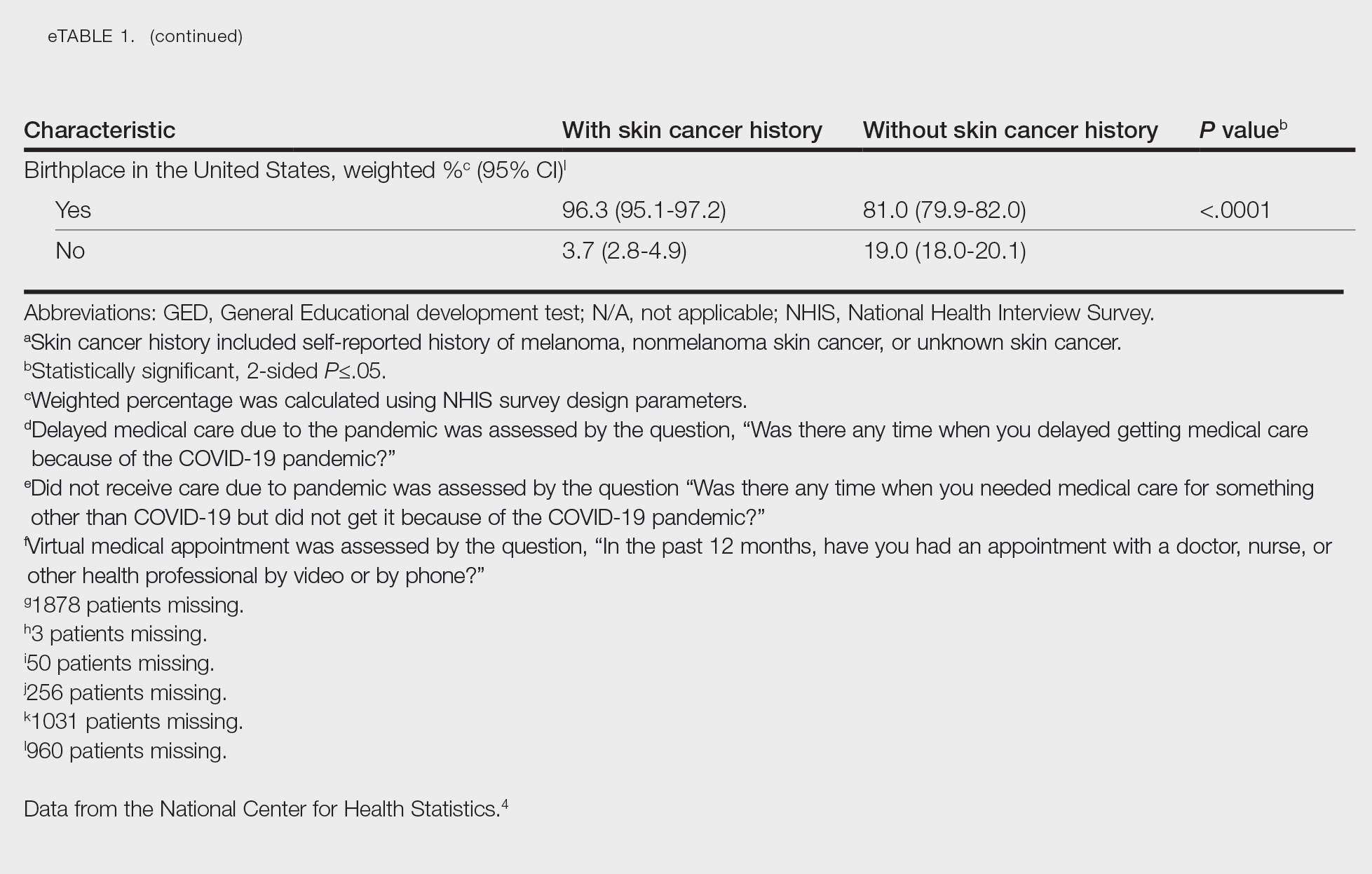

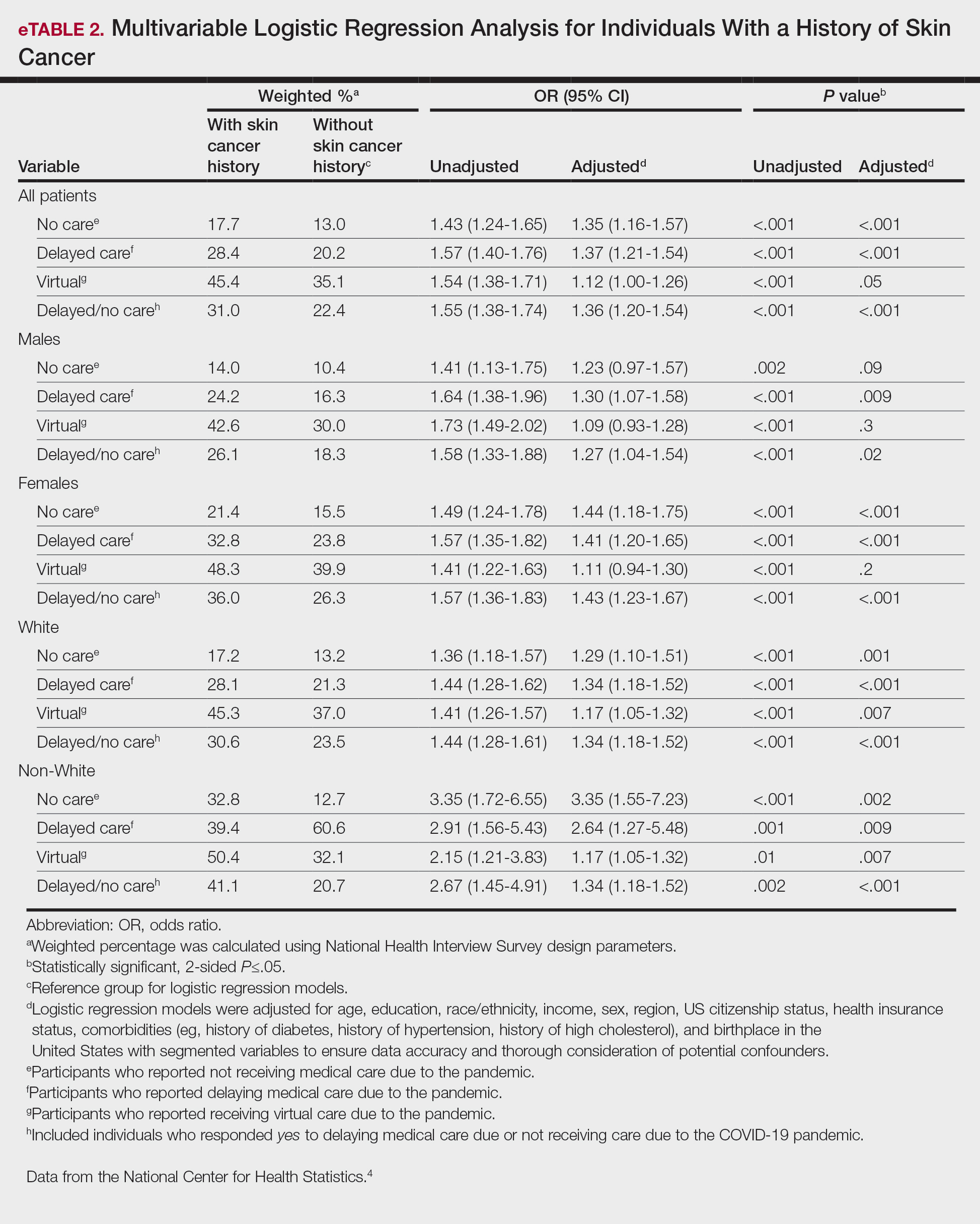

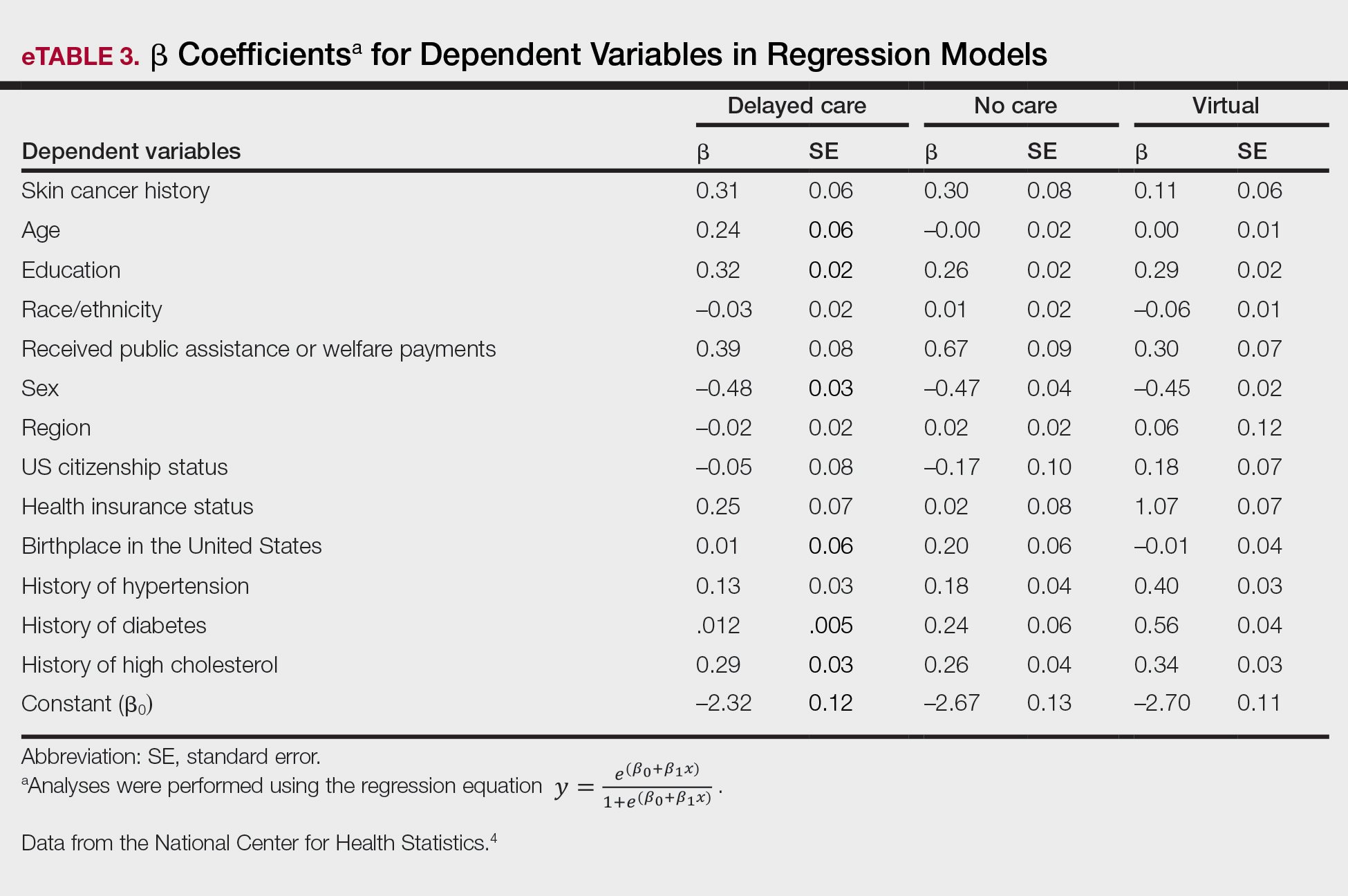

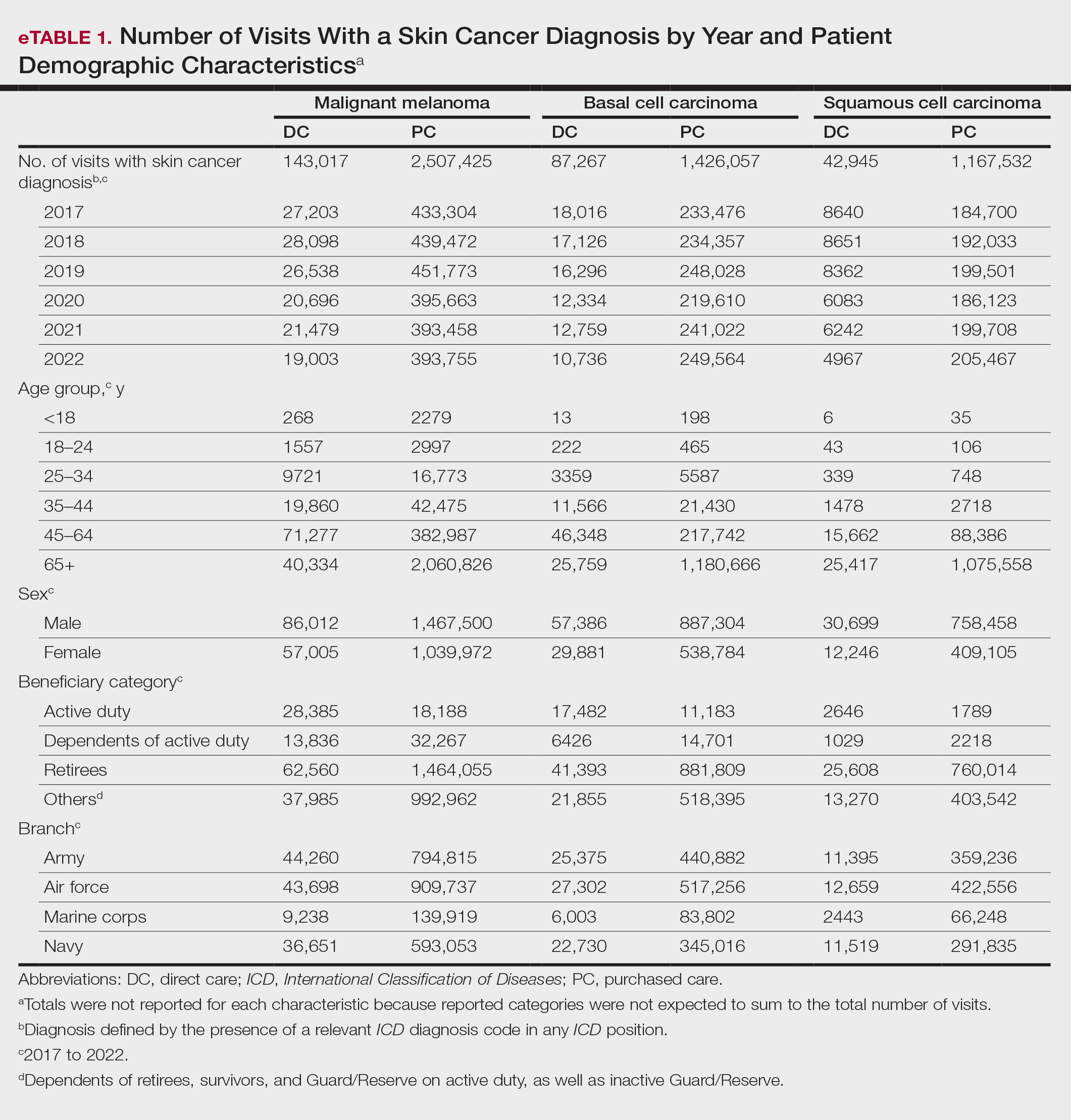

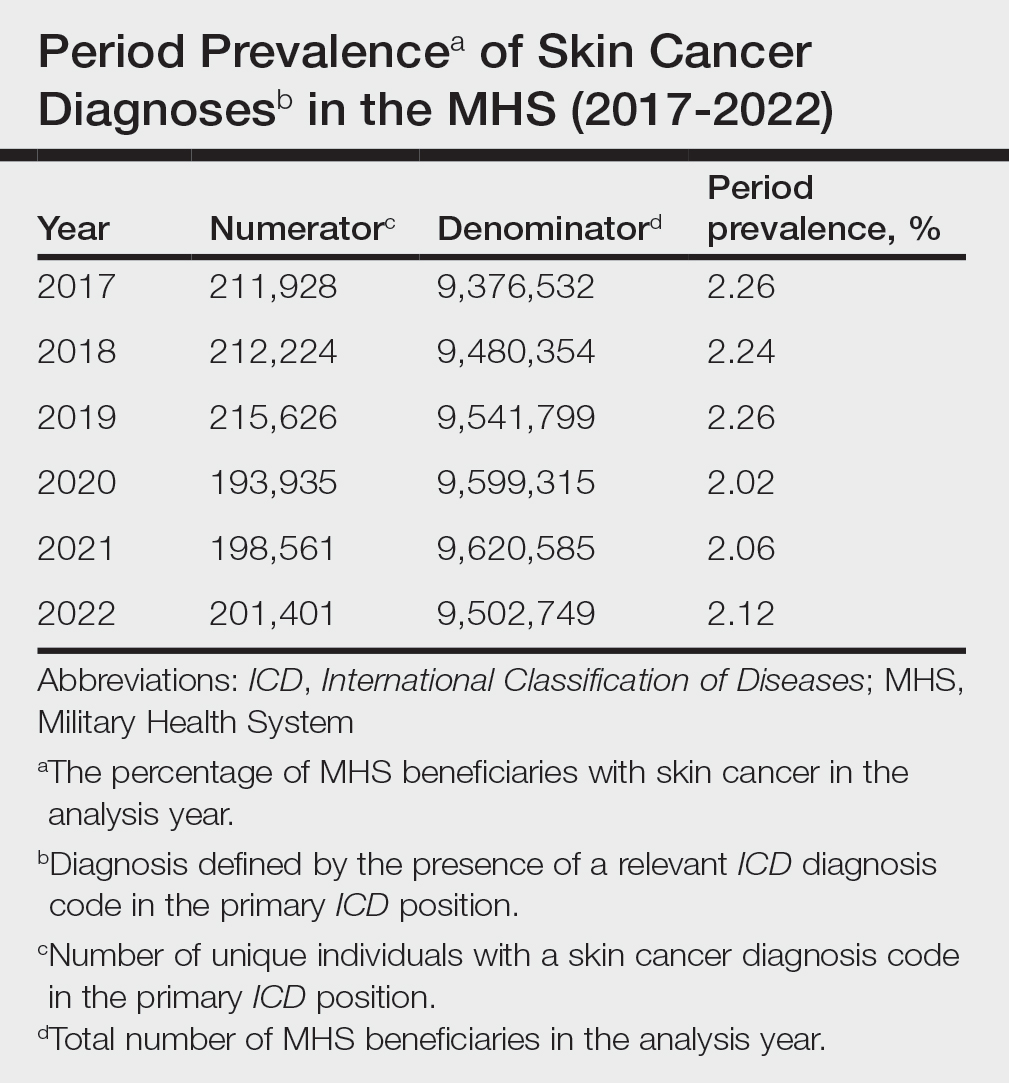

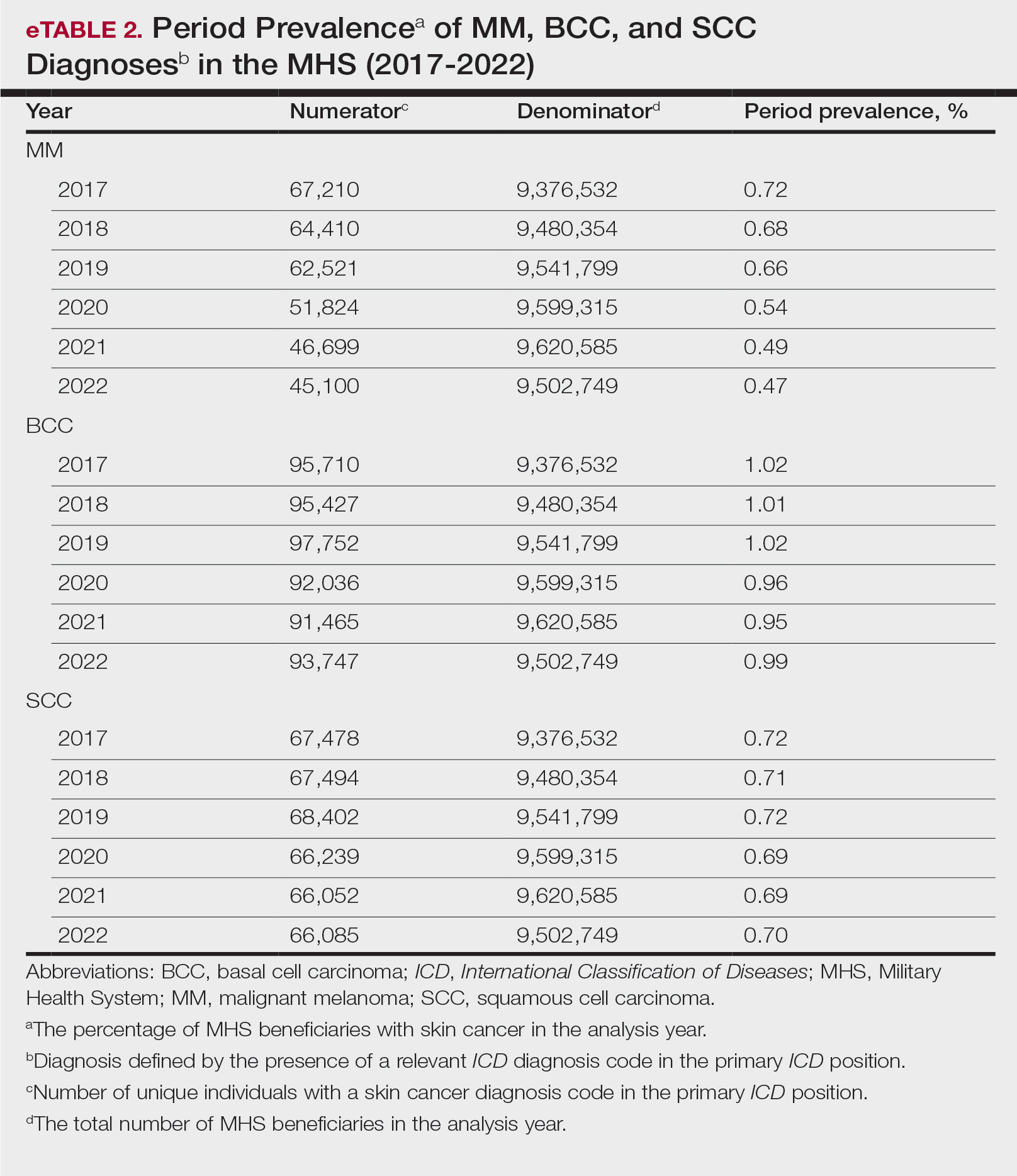

Our analysis included 46,679 patients aged 18 years or older, of whom 3.4% (weighted)(n=2204) reported a history of skin cancer (eTable 1). The weighted percentage was calculated using National Health Interview Survey design parameters (accounting for the multistage sampling design) to represent the general US population. Compared with those with no history of skin cancer, patients with a history of skin cancer were significantly more likely to delay medical care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.21-1.54; P<.001) or not receive care (AOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16-1.57; P<.001) due to the pandemic and were more likely to have had a virtual medical visit in the past 12 months (AOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00-1.26; P=.05). Additionally, subgroup analysis revealed that females were more likely than males to forego medical care (eTable 2). β Coefficients for independent and dependent variables were further analyzed using logistic regression (eTable 3).

After adjusting for various potential confounders including comorbidities, our results revealed that patients with a history of skin cancer reported that they were less likely to receive in-person medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as high-risk individuals with a history of skin cancer may have stopped receiving total-body skin examinations and dermatology care during the pandemic. Our findings showed that patients with a history of skin cancer were more likely than those without skin cancer to delay or forego care due to the pandemic, which may contribute to a higher incidence of advanced-stage melanomas postpandemic. Trepanowski et al5 reported an increased incidence of patients presenting with more advanced melanomas during the pandemic. Telemedicine was more commonly utilized by patients with a history of skin cancer during the pandemic.

In the future, virtual care may help limit advanced stages of skin cancer by serving as a viable alternative to in-person care.6 It has been reported that telemedicine can serve as a useful triage service reducing patient wait times.7 Teledermatology should not replace in-person care, as there is no evidence of the diagnostic accuracy of this service and many patients still will need to be seen in-person for confirmation of their diagnosis and potential biopsy. Further studies are needed to assess for missed skin cancer diagnoses due to the utilization of telemedicine.

Limitations of this study included a self-reported history of skin cancer, β coefficients that may suggest a high degree of collinearity, and lack of specific survey questions regarding dermatologic care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further long-term studies exploring the clinical applicability and diagnostic accuracy of virtual medicine visits for cutaneous malignancies are vital, as teledermatology may play an essential role in curbing rising skin cancer rates even beyond the pandemic.

- Guy GP Jr, Thomas CC, Thompson T, et al. Vital signs: melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections—United States, 1982-2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:591-596.

- Whiteman DC, Olsen CM, MacGregor S, et al; QSkin Study. The effect of screening on melanoma incidence and biopsy rates. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:515-522. doi:10.1111/bjd.21649

- Jobbágy A, Kiss N, Meznerics FA, et al. Emergency use and efficacy of an asynchronous teledermatology system as a novel tool for early diagnosis of skin cancer during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:2699. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052699

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

- Trepanowski N, Chang MS, Zhou G, et al. Delays in melanoma presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide multi-institutional cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1217-1219. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.031

- Chiru MR, Hindocha S, Burova E, et al. Management of the two-week wait pathway for skin cancer patients, before and during the pandemic: is virtual consultation an option? J Pers Med. 2022;12:1258. doi:10.3390/jpm12081258

- Finnane A Dallest K Janda M et al. Teledermatology for the diagnosis and management of skin cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:319-327. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4361

To the Editor:

The most common malignancy in the United States is skin cancer, with melanoma accounting for the majority of skin cancer deaths.1 Despite the lack of established guidelines for routine total-body skin examinations, many patients regularly visit their dermatologist for assessment of pigmented skin lesions.2 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients were unable to attend in-person dermatology visits, which resulted in many high-risk individuals not receiving care or alternatively seeking virtual care for cutaneous lesions.3 There has been a lack of research in the United States exploring the utilization of teledermatology during the pandemic and its overall impact on the care of patients with a history of skin cancer. We explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with skin cancer in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2020-2021 National Health Interview Survey,4 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with a self-reported history of skin cancer—melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, or unknown skin cancer. The 3 outcome variables included having a virtual medical appointment in the past 12 months (yes/no), delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no). Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between a history of skin cancer and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17.0 (StataCorp LLC). We controlled for patient age; education; race/ethnicity; received public assistance or welfare payments; sex; region; US citizenship status; health insurance status; comorbidities including history of hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia; and birthplace in the United States in the logistic regression models.

Our analysis included 46,679 patients aged 18 years or older, of whom 3.4% (weighted)(n=2204) reported a history of skin cancer (eTable 1). The weighted percentage was calculated using National Health Interview Survey design parameters (accounting for the multistage sampling design) to represent the general US population. Compared with those with no history of skin cancer, patients with a history of skin cancer were significantly more likely to delay medical care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.21-1.54; P<.001) or not receive care (AOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16-1.57; P<.001) due to the pandemic and were more likely to have had a virtual medical visit in the past 12 months (AOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00-1.26; P=.05). Additionally, subgroup analysis revealed that females were more likely than males to forego medical care (eTable 2). β Coefficients for independent and dependent variables were further analyzed using logistic regression (eTable 3).

After adjusting for various potential confounders including comorbidities, our results revealed that patients with a history of skin cancer reported that they were less likely to receive in-person medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as high-risk individuals with a history of skin cancer may have stopped receiving total-body skin examinations and dermatology care during the pandemic. Our findings showed that patients with a history of skin cancer were more likely than those without skin cancer to delay or forego care due to the pandemic, which may contribute to a higher incidence of advanced-stage melanomas postpandemic. Trepanowski et al5 reported an increased incidence of patients presenting with more advanced melanomas during the pandemic. Telemedicine was more commonly utilized by patients with a history of skin cancer during the pandemic.

In the future, virtual care may help limit advanced stages of skin cancer by serving as a viable alternative to in-person care.6 It has been reported that telemedicine can serve as a useful triage service reducing patient wait times.7 Teledermatology should not replace in-person care, as there is no evidence of the diagnostic accuracy of this service and many patients still will need to be seen in-person for confirmation of their diagnosis and potential biopsy. Further studies are needed to assess for missed skin cancer diagnoses due to the utilization of telemedicine.

Limitations of this study included a self-reported history of skin cancer, β coefficients that may suggest a high degree of collinearity, and lack of specific survey questions regarding dermatologic care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further long-term studies exploring the clinical applicability and diagnostic accuracy of virtual medicine visits for cutaneous malignancies are vital, as teledermatology may play an essential role in curbing rising skin cancer rates even beyond the pandemic.

To the Editor:

The most common malignancy in the United States is skin cancer, with melanoma accounting for the majority of skin cancer deaths.1 Despite the lack of established guidelines for routine total-body skin examinations, many patients regularly visit their dermatologist for assessment of pigmented skin lesions.2 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients were unable to attend in-person dermatology visits, which resulted in many high-risk individuals not receiving care or alternatively seeking virtual care for cutaneous lesions.3 There has been a lack of research in the United States exploring the utilization of teledermatology during the pandemic and its overall impact on the care of patients with a history of skin cancer. We explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with skin cancer in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2020-2021 National Health Interview Survey,4 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with a self-reported history of skin cancer—melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, or unknown skin cancer. The 3 outcome variables included having a virtual medical appointment in the past 12 months (yes/no), delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no). Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between a history of skin cancer and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17.0 (StataCorp LLC). We controlled for patient age; education; race/ethnicity; received public assistance or welfare payments; sex; region; US citizenship status; health insurance status; comorbidities including history of hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia; and birthplace in the United States in the logistic regression models.

Our analysis included 46,679 patients aged 18 years or older, of whom 3.4% (weighted)(n=2204) reported a history of skin cancer (eTable 1). The weighted percentage was calculated using National Health Interview Survey design parameters (accounting for the multistage sampling design) to represent the general US population. Compared with those with no history of skin cancer, patients with a history of skin cancer were significantly more likely to delay medical care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.21-1.54; P<.001) or not receive care (AOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16-1.57; P<.001) due to the pandemic and were more likely to have had a virtual medical visit in the past 12 months (AOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00-1.26; P=.05). Additionally, subgroup analysis revealed that females were more likely than males to forego medical care (eTable 2). β Coefficients for independent and dependent variables were further analyzed using logistic regression (eTable 3).

After adjusting for various potential confounders including comorbidities, our results revealed that patients with a history of skin cancer reported that they were less likely to receive in-person medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as high-risk individuals with a history of skin cancer may have stopped receiving total-body skin examinations and dermatology care during the pandemic. Our findings showed that patients with a history of skin cancer were more likely than those without skin cancer to delay or forego care due to the pandemic, which may contribute to a higher incidence of advanced-stage melanomas postpandemic. Trepanowski et al5 reported an increased incidence of patients presenting with more advanced melanomas during the pandemic. Telemedicine was more commonly utilized by patients with a history of skin cancer during the pandemic.

In the future, virtual care may help limit advanced stages of skin cancer by serving as a viable alternative to in-person care.6 It has been reported that telemedicine can serve as a useful triage service reducing patient wait times.7 Teledermatology should not replace in-person care, as there is no evidence of the diagnostic accuracy of this service and many patients still will need to be seen in-person for confirmation of their diagnosis and potential biopsy. Further studies are needed to assess for missed skin cancer diagnoses due to the utilization of telemedicine.

Limitations of this study included a self-reported history of skin cancer, β coefficients that may suggest a high degree of collinearity, and lack of specific survey questions regarding dermatologic care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further long-term studies exploring the clinical applicability and diagnostic accuracy of virtual medicine visits for cutaneous malignancies are vital, as teledermatology may play an essential role in curbing rising skin cancer rates even beyond the pandemic.

- Guy GP Jr, Thomas CC, Thompson T, et al. Vital signs: melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections—United States, 1982-2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:591-596.

- Whiteman DC, Olsen CM, MacGregor S, et al; QSkin Study. The effect of screening on melanoma incidence and biopsy rates. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:515-522. doi:10.1111/bjd.21649

- Jobbágy A, Kiss N, Meznerics FA, et al. Emergency use and efficacy of an asynchronous teledermatology system as a novel tool for early diagnosis of skin cancer during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:2699. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052699

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

- Trepanowski N, Chang MS, Zhou G, et al. Delays in melanoma presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide multi-institutional cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1217-1219. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.031

- Chiru MR, Hindocha S, Burova E, et al. Management of the two-week wait pathway for skin cancer patients, before and during the pandemic: is virtual consultation an option? J Pers Med. 2022;12:1258. doi:10.3390/jpm12081258

- Finnane A Dallest K Janda M et al. Teledermatology for the diagnosis and management of skin cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:319-327. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4361

- Guy GP Jr, Thomas CC, Thompson T, et al. Vital signs: melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections—United States, 1982-2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:591-596.

- Whiteman DC, Olsen CM, MacGregor S, et al; QSkin Study. The effect of screening on melanoma incidence and biopsy rates. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:515-522. doi:10.1111/bjd.21649

- Jobbágy A, Kiss N, Meznerics FA, et al. Emergency use and efficacy of an asynchronous teledermatology system as a novel tool for early diagnosis of skin cancer during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:2699. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052699

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

- Trepanowski N, Chang MS, Zhou G, et al. Delays in melanoma presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide multi-institutional cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1217-1219. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.031

- Chiru MR, Hindocha S, Burova E, et al. Management of the two-week wait pathway for skin cancer patients, before and during the pandemic: is virtual consultation an option? J Pers Med. 2022;12:1258. doi:10.3390/jpm12081258

- Finnane A Dallest K Janda M et al. Teledermatology for the diagnosis and management of skin cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:319-327. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4361

PRACTICE POINTS

- The COVID-19 pandemic has altered the landscape of medicine, as many individuals are now utilizing telemedicine to receive care.

- Many individuals will continue to receive telemedicine moving forward, making it crucial to understand access to care.

Comment on “Skin Cancer Screening: The Paradox of Melanoma and Improved All-Cause Mortality”

To the Editor:

I was unsurprised and gratified by the information presented in the Viewpoint on skin cancer screening by Ngo1 (Cutis. 2024;113:94-96). In my 30 years as a community dermatologist, I have observed that patients who opt to have periodic full-body skin examinations usually are more health literate, more likely to have a primary care physician (PCP) who has encouraged them to do so (ie, a conscientious practitioner directing their preventive care), more likely to have a strong will to live, and less likely to have multiple stressors that preclude self-care (eg, may be less likely to have a spouse for whom they are a caregiver) compared to those who do not get screened.

Findings on a full-body skin examination may impact patients in many ways, not only by the detection of skin cancers. I have discovered the following:

- evidence of diabetes/insulin resistance in the form of acanthosis nigricans, tinea corporis, erythrasma;

- evidence of rosacea associated with excessive alcohol intake;

- evidence of smoking-related issues such as psoriasis or hidradenitis suppurativa;

- cutaneous evidence of other systemic diseases (eg, autoimmune disease, cancer);

- elucidation of other chronic health problems (eg, psoriasis of the skin as a clue for undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis); and

- detection of parasites on the skin (eg, ticks) or signs of infection that may have notable ramifications (eg, interdigital maceration of a diabetic patient with tinea pedis).

I even saw a patient who had been sent for magnetic resonance imaging for back pain by her internist without any physical examination when she actually had an erosion over the sacrum from a rug burn!

When conducting full-body skin examinations, dermatologists should not underestimate these principles:

- The “magic” of using a relatively noninvasive and sensitive screening tool—comfort and stress reduction for the patient from a thorough visual, tactile, olfactory, and auditory examination.

- Human interaction—especially when the patient is seen annually or even more frequently over a period of years or decades, and especially when an excellent patient-physician rapport has been established.

- The impact of improving a patient’s appearance on their overall sense of well-being (eg, by controlling rosacea).

- The opportunity to introduce concepts (ie, educate patients) such as alcohol avoidance, smoking cessation, weight reduction, hygiene, diet, and exercise in a more tangential way than a PCP, as well as to consider with patients the idea that lifestyle modification may be an adjunct, if not a replacement, for prescription treatments.

- The stress reduction that ensues when a variety of self-identified health issues are addressed, for which the only treatment may be reassurance.

I would add to Dr. Ngo’s argument that stratifying patients into skin cancer risk categories may be a useful measure if the only goal of periodic dermatologic evaluation is skin cancer detection. One size rarely fits all when it comes to health recommendations.

In sum, I believe that periodic full-body skin examination is absolutely beneficial to patient care, and I am not at all surprised that all-cause mortality was lower in patients who have those examinations. Furthermore, when I offer my healthy, low-risk patients the option to return in 2 years rather than 1, the vast majority insist on 1 year. My mother used to say, “It’s better to be looked over than to be overlooked,” and I tell my patients that, too—but it seems they already know that instinctively.

- Ngo BT. Skin cancer screening: the paradox of melanoma and improved all-cause mortality. Cutis. 2024;113:94-96. doi:10.12788/cutis.0948

To the Editor:

I was unsurprised and gratified by the information presented in the Viewpoint on skin cancer screening by Ngo1 (Cutis. 2024;113:94-96). In my 30 years as a community dermatologist, I have observed that patients who opt to have periodic full-body skin examinations usually are more health literate, more likely to have a primary care physician (PCP) who has encouraged them to do so (ie, a conscientious practitioner directing their preventive care), more likely to have a strong will to live, and less likely to have multiple stressors that preclude self-care (eg, may be less likely to have a spouse for whom they are a caregiver) compared to those who do not get screened.

Findings on a full-body skin examination may impact patients in many ways, not only by the detection of skin cancers. I have discovered the following:

- evidence of diabetes/insulin resistance in the form of acanthosis nigricans, tinea corporis, erythrasma;

- evidence of rosacea associated with excessive alcohol intake;

- evidence of smoking-related issues such as psoriasis or hidradenitis suppurativa;

- cutaneous evidence of other systemic diseases (eg, autoimmune disease, cancer);

- elucidation of other chronic health problems (eg, psoriasis of the skin as a clue for undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis); and

- detection of parasites on the skin (eg, ticks) or signs of infection that may have notable ramifications (eg, interdigital maceration of a diabetic patient with tinea pedis).

I even saw a patient who had been sent for magnetic resonance imaging for back pain by her internist without any physical examination when she actually had an erosion over the sacrum from a rug burn!

When conducting full-body skin examinations, dermatologists should not underestimate these principles:

- The “magic” of using a relatively noninvasive and sensitive screening tool—comfort and stress reduction for the patient from a thorough visual, tactile, olfactory, and auditory examination.

- Human interaction—especially when the patient is seen annually or even more frequently over a period of years or decades, and especially when an excellent patient-physician rapport has been established.

- The impact of improving a patient’s appearance on their overall sense of well-being (eg, by controlling rosacea).

- The opportunity to introduce concepts (ie, educate patients) such as alcohol avoidance, smoking cessation, weight reduction, hygiene, diet, and exercise in a more tangential way than a PCP, as well as to consider with patients the idea that lifestyle modification may be an adjunct, if not a replacement, for prescription treatments.

- The stress reduction that ensues when a variety of self-identified health issues are addressed, for which the only treatment may be reassurance.

I would add to Dr. Ngo’s argument that stratifying patients into skin cancer risk categories may be a useful measure if the only goal of periodic dermatologic evaluation is skin cancer detection. One size rarely fits all when it comes to health recommendations.

In sum, I believe that periodic full-body skin examination is absolutely beneficial to patient care, and I am not at all surprised that all-cause mortality was lower in patients who have those examinations. Furthermore, when I offer my healthy, low-risk patients the option to return in 2 years rather than 1, the vast majority insist on 1 year. My mother used to say, “It’s better to be looked over than to be overlooked,” and I tell my patients that, too—but it seems they already know that instinctively.

To the Editor:

I was unsurprised and gratified by the information presented in the Viewpoint on skin cancer screening by Ngo1 (Cutis. 2024;113:94-96). In my 30 years as a community dermatologist, I have observed that patients who opt to have periodic full-body skin examinations usually are more health literate, more likely to have a primary care physician (PCP) who has encouraged them to do so (ie, a conscientious practitioner directing their preventive care), more likely to have a strong will to live, and less likely to have multiple stressors that preclude self-care (eg, may be less likely to have a spouse for whom they are a caregiver) compared to those who do not get screened.

Findings on a full-body skin examination may impact patients in many ways, not only by the detection of skin cancers. I have discovered the following:

- evidence of diabetes/insulin resistance in the form of acanthosis nigricans, tinea corporis, erythrasma;

- evidence of rosacea associated with excessive alcohol intake;

- evidence of smoking-related issues such as psoriasis or hidradenitis suppurativa;

- cutaneous evidence of other systemic diseases (eg, autoimmune disease, cancer);

- elucidation of other chronic health problems (eg, psoriasis of the skin as a clue for undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis); and

- detection of parasites on the skin (eg, ticks) or signs of infection that may have notable ramifications (eg, interdigital maceration of a diabetic patient with tinea pedis).

I even saw a patient who had been sent for magnetic resonance imaging for back pain by her internist without any physical examination when she actually had an erosion over the sacrum from a rug burn!

When conducting full-body skin examinations, dermatologists should not underestimate these principles: