User login

The in-person postpartum blood pressure check: For whose benefit?

CASE Patient questions need for postpartum BP check

Ms. P presents at 28 weeks’ gestation with superimposed preeclampsia. She receives antenatal corticosteroids and titration of her nifedipine, but she is delivered at 29 weeks because of worsening fetal status. Her physician recommends a blood pressure (BP) visit in the office at 7 days postpartum.

She asks, “But can’t I just call you with the BP reading? And what do I do in the meantime?”

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and chronic hypertension remain among the leading causes of maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide.1 The postpartum period remains a particularly high-risk time since up to 40% of maternal mortality can occur after delivery. To that end, the 2013 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Hypertension in Pregnancy Task Force recommends postpartum follow-up 7 to 10 days after delivery in women with a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy.2

Why we need to find an alternative approach

Unfortunately, these guidelines are both cumbersome and insufficient. Up to one-third of patients do not attend their postpartum visit, particularly those who are young, uninsured, and nonwhite, a list uncomfortably similar to that for women most at risk for adverse outcomes after a high-risk pregnancy. In addition, the 7- to 10-day visit still represents only a single snapshot of the patient’s BP values rather than an ongoing assessment of symptoms or BP elevation over time. Moreover, studies also have shown that BP in both normotensive and hypertensive women often rises by the fifth day postpartum, suggesting that leaving this large window of time without surveillance may miss an opportunity to detect elevated BP in a more timely manner.3

It is time to break the habit of the in-office postpartum BP check and to evaluate the patient where she is and when she needs it. Research in the last 2 years shows that there are several solutions to our case patient’s question.

Solution 1: The provider-driven system

“Of course. Text us your numbers, and you will hear from the doctor if you need to do anything differently.”

One method that addresses both the communication and safety issues inherent in the 7- to 10-day routine in-office BP check is to have the patient send in her BP measurements for direct clinician review.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania developed a robust program using their Way to Health platform.4 Participating patients text their BP values twice daily, and they receive automated feedback for all values, with additional human feedback in real time from a clinician for severe-range values (>160 mm Hg systolic or >110 mm Hg diastolic). As an added safety measure, a physician reviews all inputted BPs daily and assesses the need for antihypertensive medication for BPs in the high mild range. Using this protocol, the researchers achieved a significant increase in adherence with the recommendation for reporting a BP value in the first 10 days after discharge (from 44% to 92%) as well as having fewer readmissions in the text-messaging arm (4% vs 0%).

Perhaps most impressive, though, is that the technology use eliminated pre-existing racial disparities in adherence. Black participants were as likely as nonblack participants to report a postpartum BP in the text-messaging system (93% vs 91%) despite being less than half as likely to keep a BP check visit (33% vs 70%).5

A similar solution is in place at the University of Pittsburgh, where a text message system on the Vivify platform is used to deliver patient BP measurements to a centralized monitoring team.6 This program is unique in that, rather than relying on a single physician, it is run through a nurse “call center” that allowed them to expand to 3 hospitals with the use of a single centralized monitoring team. To date, the program has enrolled more than 2,000 patients and achieved patient satisfaction rates greater than 94%.

A final program to consider was developed and piloted at the University of Wisconsin with an added technological advance: the use of a Bluetooth-enabled BP cuff that permits values to be automatically transmitted to a tablet that then uploads the information to a centralized database.7 This database was in turn monitored by trained nurses for safety and initiation or titration of antihypertensive medication as needed. Similar to the experience at the University of Pennsylvania, the researchers found improved adherence with monitoring and a notable reduction in readmissions (3.7% in controls vs 0.5% in the intervention arm). Of note, among those who did receive the ongoing monitoring, severe hypertension occurred in 56 (26.2%) of those patients and did so a mean of 6 days after discharge (that is, prior to when they typically would have seen a provider.)

The promise of such provider-driven systems is that they represent a true chronicle of a patient’s ongoing clinical course rather than a single snapshot of her BP in an artificial environment (and often after the highest risk time period!). In addition, direct monitoring by clinicians ensures an optimal safety profile.

Such systems, however, are also extremely resource intense in terms of both upfront information technology investment and ongoing provider surveillance. The systems above also relied on giving the patients a BP cuff, so it is unclear whether it was the technology support or this simple intervention that yielded the benefits. Nonetheless, the benefits were undeniable, and the financial costs saved by reducing even 1 hospital admission as well as the costs of outpatient surveillance may in the end justify these upfront expenditures.

Continue to: Solution 2: The algorithm-driven system...

Solution 2: The algorithm-driven system

“Sure. Plug your numbers into our system, and you’ll receive an automated response as to what to do next.”

One way to alleviate both the financial and opportunity cost of constant clinician surveillance would be to offload some tasks to algorithmic support. This approach—home BP monitoring accompanied by self-titration of antihypertensive medication—has been validated in outpatient primary care hypertension management in nonpregnant adults and more recently for postpartum patients as well.

In the SNAP-HT trial, investigators randomly assigned women to either usual care or algorithm-driven outpatient BP management.8 While both groups had serial visits (for safety monitoring), those in the experimental arm were advised only by the algorithm for any ongoing titration of medication. At 6 weeks, the investigators found that BPs were lower in the intervention group, and diastolic BPs remained lower at 6 months.

This methodology emphasizes the potential utility of true self-management of hypertension in the postpartum period. It relies, however, on having a highly developed system in place that can receive the data, respond with recommendations, and safely monitor for any aberrations in the feed. Still, this hybrid method may represent the sweet spot: a combination that ensures adequate surveillance while not overburdening the clinician with the simpler, initial steps in postpartum antihypertensive management.

Solution 3: The DIY system

“That’s a good point. I want to hear about your blood pressure readings in the meantime. Here’s what we can do.”

What about the 99% of practicing ObGyns who do not have an entire connected system for remote hypertension monitoring? A number of options can be put in place today with little cost and even less tech know-how (see “Do-it-yourself options for remote blood pressure monitoring,” below). Note that since many of these options would not be monitored in “real time” like the connected systems discussed above, the patient should be given strict parameters for contacting her clinician directly. These do-it-yourself, or DIY, methods are instead best for the purpose of chronic monitoring and medication titration but are still an improvement in communication over the single-serve BP check.

The bottom line

Pregnant women represent one of the most connected, Internet-savvy demographic groups of any patient population: More than three-quarters of pregnant women turn to the Internet for advice during their pregnancy.9,10 In addition, unlike most social determinants of health, such as housing, food access, and health care coverage, access to connected electronic devices differs little across racial lines, suggesting the potential for targeting health care inequities by implementing more—not less—technology into prenatal and postpartum care.

For this generation of new mothers, the in-office postpartum BP check is insufficient, artificial, and simply a waste of everyone’s time. While there is no one-size-fits-all approach, there are many options, and it is up to us as health care providers to facilitate the right care, in the right place, at the right time for our patients. ●

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Haritha Pavuluri, Margaret Oliver, and Samantha Boniface for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Electronic health record (EHR) messaging

Most EHR systems have some form of patient messaging built in. Consider asking your patient to:

- message her blood pressure measurements every 1 to 2 days

- send a photo of handwritten blood pressure measurements

Vendor text messaging platforms

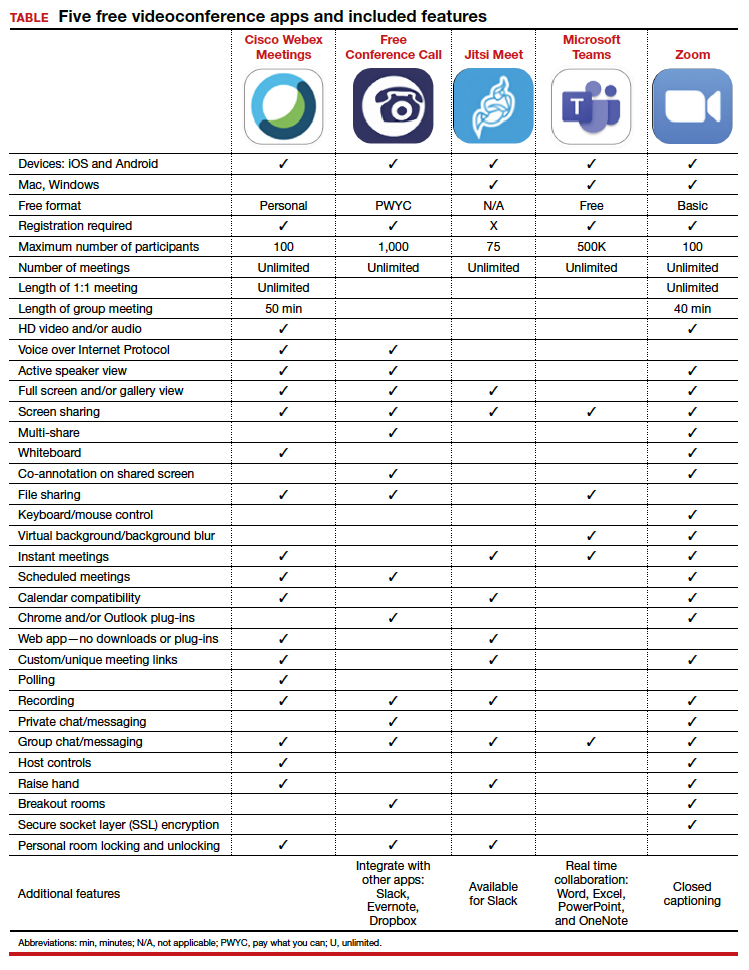

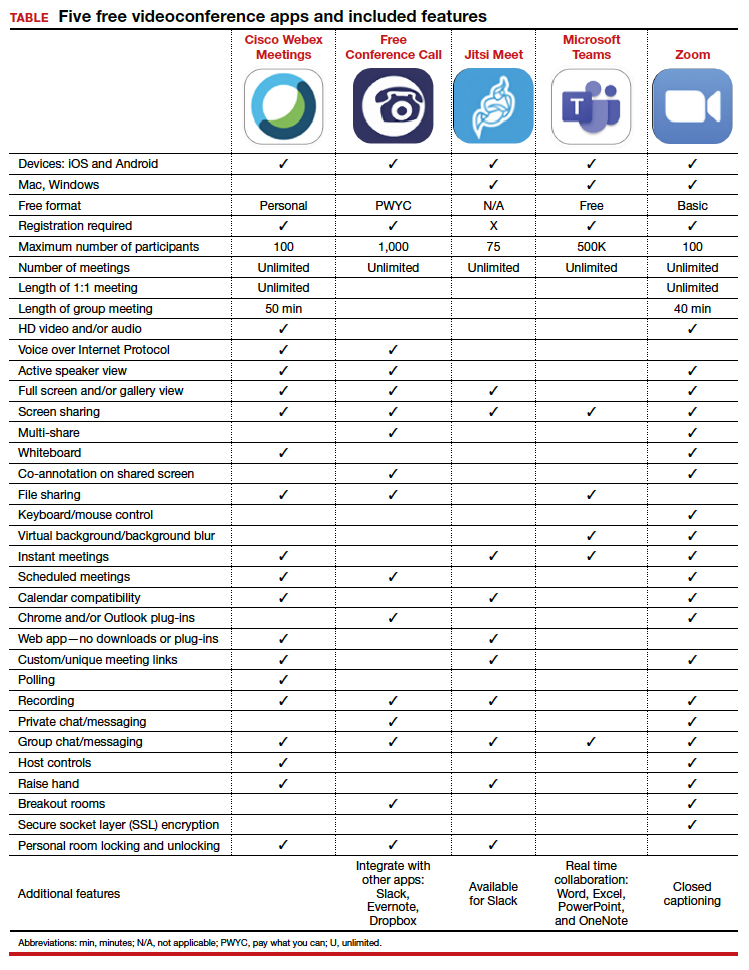

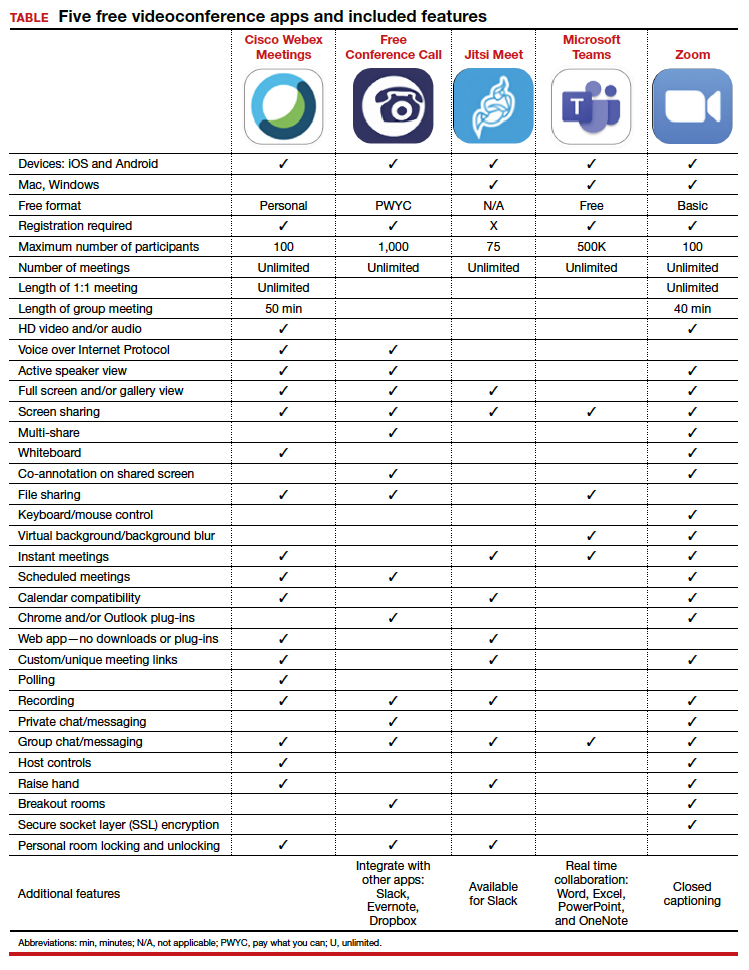

The year 2020 has seen the entire telehealth space grow tremendously, and platforms such as Doxy.me (https://doxy.me) and Updox (https://www.updox.com) allow secure text messaging with patients.

All-in-one connected vendor solutions

Third-party solutions are available that give the patient a connected blood pressure cuff, scale, and personalized app. For the clinician, these data then can be accessed either independently through a portal or can be integrated into the EHR. Examples of 2 companies include:

- Babyscripts (https://www.getbabyscripts.com)

- Wildflower Health (https://www.wildflowerhealth.com)

Telehealth visits

Scheduling weekly telephone or video visits (while not near the frequency of the above) would still yield greater engagement, and many payors currently reimburse for these visits at rates on par with in-person visits.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin summary, No. 222. Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:1492-1495.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1122-1131.

- Walters BN, Thompson ME, Lee A, et al. Blood pressure in the puerperium. Clin Sci. 1986;71:589-594.

- Hirshberg A, Downes K, Srinivas S. Comparing standard office-based follow-up with text-based remote monitoring in the management of postpartum hypertension: a randomised clinical trial. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27:871-877.

- Hirshberg A, Sammel MD, Srinivas SK. Text message remote monitoring reduced racial disparities in postpartum blood pressure ascertainment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:283-285.

- Hauspurg A, Lemon LS, Quinn BA, et al. A postpartum remote hypertension monitoring protocol implemented at the hospital level. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:685-691.

- Hoppe KK, Thomas N, Zernick M, et al. Telehealth with remote blood pressure monitoring compared to standard care for postpartum hypertension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;S0002-9378(20)30554-doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.027.

- Cairns AE, Tucker KL, Leeson P, et al. Self-management of postnatal hypertension. Hypertension. 2018;72:425-432.

- Pew Research Center. Mobile fact sheet, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- Sayakhot P, Carolan-Olah M. Internet use by pregnant women seeking pregnancy-related information: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:65

CASE Patient questions need for postpartum BP check

Ms. P presents at 28 weeks’ gestation with superimposed preeclampsia. She receives antenatal corticosteroids and titration of her nifedipine, but she is delivered at 29 weeks because of worsening fetal status. Her physician recommends a blood pressure (BP) visit in the office at 7 days postpartum.

She asks, “But can’t I just call you with the BP reading? And what do I do in the meantime?”

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and chronic hypertension remain among the leading causes of maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide.1 The postpartum period remains a particularly high-risk time since up to 40% of maternal mortality can occur after delivery. To that end, the 2013 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Hypertension in Pregnancy Task Force recommends postpartum follow-up 7 to 10 days after delivery in women with a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy.2

Why we need to find an alternative approach

Unfortunately, these guidelines are both cumbersome and insufficient. Up to one-third of patients do not attend their postpartum visit, particularly those who are young, uninsured, and nonwhite, a list uncomfortably similar to that for women most at risk for adverse outcomes after a high-risk pregnancy. In addition, the 7- to 10-day visit still represents only a single snapshot of the patient’s BP values rather than an ongoing assessment of symptoms or BP elevation over time. Moreover, studies also have shown that BP in both normotensive and hypertensive women often rises by the fifth day postpartum, suggesting that leaving this large window of time without surveillance may miss an opportunity to detect elevated BP in a more timely manner.3

It is time to break the habit of the in-office postpartum BP check and to evaluate the patient where she is and when she needs it. Research in the last 2 years shows that there are several solutions to our case patient’s question.

Solution 1: The provider-driven system

“Of course. Text us your numbers, and you will hear from the doctor if you need to do anything differently.”

One method that addresses both the communication and safety issues inherent in the 7- to 10-day routine in-office BP check is to have the patient send in her BP measurements for direct clinician review.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania developed a robust program using their Way to Health platform.4 Participating patients text their BP values twice daily, and they receive automated feedback for all values, with additional human feedback in real time from a clinician for severe-range values (>160 mm Hg systolic or >110 mm Hg diastolic). As an added safety measure, a physician reviews all inputted BPs daily and assesses the need for antihypertensive medication for BPs in the high mild range. Using this protocol, the researchers achieved a significant increase in adherence with the recommendation for reporting a BP value in the first 10 days after discharge (from 44% to 92%) as well as having fewer readmissions in the text-messaging arm (4% vs 0%).

Perhaps most impressive, though, is that the technology use eliminated pre-existing racial disparities in adherence. Black participants were as likely as nonblack participants to report a postpartum BP in the text-messaging system (93% vs 91%) despite being less than half as likely to keep a BP check visit (33% vs 70%).5

A similar solution is in place at the University of Pittsburgh, where a text message system on the Vivify platform is used to deliver patient BP measurements to a centralized monitoring team.6 This program is unique in that, rather than relying on a single physician, it is run through a nurse “call center” that allowed them to expand to 3 hospitals with the use of a single centralized monitoring team. To date, the program has enrolled more than 2,000 patients and achieved patient satisfaction rates greater than 94%.

A final program to consider was developed and piloted at the University of Wisconsin with an added technological advance: the use of a Bluetooth-enabled BP cuff that permits values to be automatically transmitted to a tablet that then uploads the information to a centralized database.7 This database was in turn monitored by trained nurses for safety and initiation or titration of antihypertensive medication as needed. Similar to the experience at the University of Pennsylvania, the researchers found improved adherence with monitoring and a notable reduction in readmissions (3.7% in controls vs 0.5% in the intervention arm). Of note, among those who did receive the ongoing monitoring, severe hypertension occurred in 56 (26.2%) of those patients and did so a mean of 6 days after discharge (that is, prior to when they typically would have seen a provider.)

The promise of such provider-driven systems is that they represent a true chronicle of a patient’s ongoing clinical course rather than a single snapshot of her BP in an artificial environment (and often after the highest risk time period!). In addition, direct monitoring by clinicians ensures an optimal safety profile.

Such systems, however, are also extremely resource intense in terms of both upfront information technology investment and ongoing provider surveillance. The systems above also relied on giving the patients a BP cuff, so it is unclear whether it was the technology support or this simple intervention that yielded the benefits. Nonetheless, the benefits were undeniable, and the financial costs saved by reducing even 1 hospital admission as well as the costs of outpatient surveillance may in the end justify these upfront expenditures.

Continue to: Solution 2: The algorithm-driven system...

Solution 2: The algorithm-driven system

“Sure. Plug your numbers into our system, and you’ll receive an automated response as to what to do next.”

One way to alleviate both the financial and opportunity cost of constant clinician surveillance would be to offload some tasks to algorithmic support. This approach—home BP monitoring accompanied by self-titration of antihypertensive medication—has been validated in outpatient primary care hypertension management in nonpregnant adults and more recently for postpartum patients as well.

In the SNAP-HT trial, investigators randomly assigned women to either usual care or algorithm-driven outpatient BP management.8 While both groups had serial visits (for safety monitoring), those in the experimental arm were advised only by the algorithm for any ongoing titration of medication. At 6 weeks, the investigators found that BPs were lower in the intervention group, and diastolic BPs remained lower at 6 months.

This methodology emphasizes the potential utility of true self-management of hypertension in the postpartum period. It relies, however, on having a highly developed system in place that can receive the data, respond with recommendations, and safely monitor for any aberrations in the feed. Still, this hybrid method may represent the sweet spot: a combination that ensures adequate surveillance while not overburdening the clinician with the simpler, initial steps in postpartum antihypertensive management.

Solution 3: The DIY system

“That’s a good point. I want to hear about your blood pressure readings in the meantime. Here’s what we can do.”

What about the 99% of practicing ObGyns who do not have an entire connected system for remote hypertension monitoring? A number of options can be put in place today with little cost and even less tech know-how (see “Do-it-yourself options for remote blood pressure monitoring,” below). Note that since many of these options would not be monitored in “real time” like the connected systems discussed above, the patient should be given strict parameters for contacting her clinician directly. These do-it-yourself, or DIY, methods are instead best for the purpose of chronic monitoring and medication titration but are still an improvement in communication over the single-serve BP check.

The bottom line

Pregnant women represent one of the most connected, Internet-savvy demographic groups of any patient population: More than three-quarters of pregnant women turn to the Internet for advice during their pregnancy.9,10 In addition, unlike most social determinants of health, such as housing, food access, and health care coverage, access to connected electronic devices differs little across racial lines, suggesting the potential for targeting health care inequities by implementing more—not less—technology into prenatal and postpartum care.

For this generation of new mothers, the in-office postpartum BP check is insufficient, artificial, and simply a waste of everyone’s time. While there is no one-size-fits-all approach, there are many options, and it is up to us as health care providers to facilitate the right care, in the right place, at the right time for our patients. ●

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Haritha Pavuluri, Margaret Oliver, and Samantha Boniface for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Electronic health record (EHR) messaging

Most EHR systems have some form of patient messaging built in. Consider asking your patient to:

- message her blood pressure measurements every 1 to 2 days

- send a photo of handwritten blood pressure measurements

Vendor text messaging platforms

The year 2020 has seen the entire telehealth space grow tremendously, and platforms such as Doxy.me (https://doxy.me) and Updox (https://www.updox.com) allow secure text messaging with patients.

All-in-one connected vendor solutions

Third-party solutions are available that give the patient a connected blood pressure cuff, scale, and personalized app. For the clinician, these data then can be accessed either independently through a portal or can be integrated into the EHR. Examples of 2 companies include:

- Babyscripts (https://www.getbabyscripts.com)

- Wildflower Health (https://www.wildflowerhealth.com)

Telehealth visits

Scheduling weekly telephone or video visits (while not near the frequency of the above) would still yield greater engagement, and many payors currently reimburse for these visits at rates on par with in-person visits.

CASE Patient questions need for postpartum BP check

Ms. P presents at 28 weeks’ gestation with superimposed preeclampsia. She receives antenatal corticosteroids and titration of her nifedipine, but she is delivered at 29 weeks because of worsening fetal status. Her physician recommends a blood pressure (BP) visit in the office at 7 days postpartum.

She asks, “But can’t I just call you with the BP reading? And what do I do in the meantime?”

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and chronic hypertension remain among the leading causes of maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide.1 The postpartum period remains a particularly high-risk time since up to 40% of maternal mortality can occur after delivery. To that end, the 2013 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Hypertension in Pregnancy Task Force recommends postpartum follow-up 7 to 10 days after delivery in women with a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy.2

Why we need to find an alternative approach

Unfortunately, these guidelines are both cumbersome and insufficient. Up to one-third of patients do not attend their postpartum visit, particularly those who are young, uninsured, and nonwhite, a list uncomfortably similar to that for women most at risk for adverse outcomes after a high-risk pregnancy. In addition, the 7- to 10-day visit still represents only a single snapshot of the patient’s BP values rather than an ongoing assessment of symptoms or BP elevation over time. Moreover, studies also have shown that BP in both normotensive and hypertensive women often rises by the fifth day postpartum, suggesting that leaving this large window of time without surveillance may miss an opportunity to detect elevated BP in a more timely manner.3

It is time to break the habit of the in-office postpartum BP check and to evaluate the patient where she is and when she needs it. Research in the last 2 years shows that there are several solutions to our case patient’s question.

Solution 1: The provider-driven system

“Of course. Text us your numbers, and you will hear from the doctor if you need to do anything differently.”

One method that addresses both the communication and safety issues inherent in the 7- to 10-day routine in-office BP check is to have the patient send in her BP measurements for direct clinician review.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania developed a robust program using their Way to Health platform.4 Participating patients text their BP values twice daily, and they receive automated feedback for all values, with additional human feedback in real time from a clinician for severe-range values (>160 mm Hg systolic or >110 mm Hg diastolic). As an added safety measure, a physician reviews all inputted BPs daily and assesses the need for antihypertensive medication for BPs in the high mild range. Using this protocol, the researchers achieved a significant increase in adherence with the recommendation for reporting a BP value in the first 10 days after discharge (from 44% to 92%) as well as having fewer readmissions in the text-messaging arm (4% vs 0%).

Perhaps most impressive, though, is that the technology use eliminated pre-existing racial disparities in adherence. Black participants were as likely as nonblack participants to report a postpartum BP in the text-messaging system (93% vs 91%) despite being less than half as likely to keep a BP check visit (33% vs 70%).5

A similar solution is in place at the University of Pittsburgh, where a text message system on the Vivify platform is used to deliver patient BP measurements to a centralized monitoring team.6 This program is unique in that, rather than relying on a single physician, it is run through a nurse “call center” that allowed them to expand to 3 hospitals with the use of a single centralized monitoring team. To date, the program has enrolled more than 2,000 patients and achieved patient satisfaction rates greater than 94%.

A final program to consider was developed and piloted at the University of Wisconsin with an added technological advance: the use of a Bluetooth-enabled BP cuff that permits values to be automatically transmitted to a tablet that then uploads the information to a centralized database.7 This database was in turn monitored by trained nurses for safety and initiation or titration of antihypertensive medication as needed. Similar to the experience at the University of Pennsylvania, the researchers found improved adherence with monitoring and a notable reduction in readmissions (3.7% in controls vs 0.5% in the intervention arm). Of note, among those who did receive the ongoing monitoring, severe hypertension occurred in 56 (26.2%) of those patients and did so a mean of 6 days after discharge (that is, prior to when they typically would have seen a provider.)

The promise of such provider-driven systems is that they represent a true chronicle of a patient’s ongoing clinical course rather than a single snapshot of her BP in an artificial environment (and often after the highest risk time period!). In addition, direct monitoring by clinicians ensures an optimal safety profile.

Such systems, however, are also extremely resource intense in terms of both upfront information technology investment and ongoing provider surveillance. The systems above also relied on giving the patients a BP cuff, so it is unclear whether it was the technology support or this simple intervention that yielded the benefits. Nonetheless, the benefits were undeniable, and the financial costs saved by reducing even 1 hospital admission as well as the costs of outpatient surveillance may in the end justify these upfront expenditures.

Continue to: Solution 2: The algorithm-driven system...

Solution 2: The algorithm-driven system

“Sure. Plug your numbers into our system, and you’ll receive an automated response as to what to do next.”

One way to alleviate both the financial and opportunity cost of constant clinician surveillance would be to offload some tasks to algorithmic support. This approach—home BP monitoring accompanied by self-titration of antihypertensive medication—has been validated in outpatient primary care hypertension management in nonpregnant adults and more recently for postpartum patients as well.

In the SNAP-HT trial, investigators randomly assigned women to either usual care or algorithm-driven outpatient BP management.8 While both groups had serial visits (for safety monitoring), those in the experimental arm were advised only by the algorithm for any ongoing titration of medication. At 6 weeks, the investigators found that BPs were lower in the intervention group, and diastolic BPs remained lower at 6 months.

This methodology emphasizes the potential utility of true self-management of hypertension in the postpartum period. It relies, however, on having a highly developed system in place that can receive the data, respond with recommendations, and safely monitor for any aberrations in the feed. Still, this hybrid method may represent the sweet spot: a combination that ensures adequate surveillance while not overburdening the clinician with the simpler, initial steps in postpartum antihypertensive management.

Solution 3: The DIY system

“That’s a good point. I want to hear about your blood pressure readings in the meantime. Here’s what we can do.”

What about the 99% of practicing ObGyns who do not have an entire connected system for remote hypertension monitoring? A number of options can be put in place today with little cost and even less tech know-how (see “Do-it-yourself options for remote blood pressure monitoring,” below). Note that since many of these options would not be monitored in “real time” like the connected systems discussed above, the patient should be given strict parameters for contacting her clinician directly. These do-it-yourself, or DIY, methods are instead best for the purpose of chronic monitoring and medication titration but are still an improvement in communication over the single-serve BP check.

The bottom line

Pregnant women represent one of the most connected, Internet-savvy demographic groups of any patient population: More than three-quarters of pregnant women turn to the Internet for advice during their pregnancy.9,10 In addition, unlike most social determinants of health, such as housing, food access, and health care coverage, access to connected electronic devices differs little across racial lines, suggesting the potential for targeting health care inequities by implementing more—not less—technology into prenatal and postpartum care.

For this generation of new mothers, the in-office postpartum BP check is insufficient, artificial, and simply a waste of everyone’s time. While there is no one-size-fits-all approach, there are many options, and it is up to us as health care providers to facilitate the right care, in the right place, at the right time for our patients. ●

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Haritha Pavuluri, Margaret Oliver, and Samantha Boniface for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Electronic health record (EHR) messaging

Most EHR systems have some form of patient messaging built in. Consider asking your patient to:

- message her blood pressure measurements every 1 to 2 days

- send a photo of handwritten blood pressure measurements

Vendor text messaging platforms

The year 2020 has seen the entire telehealth space grow tremendously, and platforms such as Doxy.me (https://doxy.me) and Updox (https://www.updox.com) allow secure text messaging with patients.

All-in-one connected vendor solutions

Third-party solutions are available that give the patient a connected blood pressure cuff, scale, and personalized app. For the clinician, these data then can be accessed either independently through a portal or can be integrated into the EHR. Examples of 2 companies include:

- Babyscripts (https://www.getbabyscripts.com)

- Wildflower Health (https://www.wildflowerhealth.com)

Telehealth visits

Scheduling weekly telephone or video visits (while not near the frequency of the above) would still yield greater engagement, and many payors currently reimburse for these visits at rates on par with in-person visits.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin summary, No. 222. Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:1492-1495.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1122-1131.

- Walters BN, Thompson ME, Lee A, et al. Blood pressure in the puerperium. Clin Sci. 1986;71:589-594.

- Hirshberg A, Downes K, Srinivas S. Comparing standard office-based follow-up with text-based remote monitoring in the management of postpartum hypertension: a randomised clinical trial. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27:871-877.

- Hirshberg A, Sammel MD, Srinivas SK. Text message remote monitoring reduced racial disparities in postpartum blood pressure ascertainment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:283-285.

- Hauspurg A, Lemon LS, Quinn BA, et al. A postpartum remote hypertension monitoring protocol implemented at the hospital level. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:685-691.

- Hoppe KK, Thomas N, Zernick M, et al. Telehealth with remote blood pressure monitoring compared to standard care for postpartum hypertension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;S0002-9378(20)30554-doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.027.

- Cairns AE, Tucker KL, Leeson P, et al. Self-management of postnatal hypertension. Hypertension. 2018;72:425-432.

- Pew Research Center. Mobile fact sheet, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- Sayakhot P, Carolan-Olah M. Internet use by pregnant women seeking pregnancy-related information: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:65

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin summary, No. 222. Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:1492-1495.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1122-1131.

- Walters BN, Thompson ME, Lee A, et al. Blood pressure in the puerperium. Clin Sci. 1986;71:589-594.

- Hirshberg A, Downes K, Srinivas S. Comparing standard office-based follow-up with text-based remote monitoring in the management of postpartum hypertension: a randomised clinical trial. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27:871-877.

- Hirshberg A, Sammel MD, Srinivas SK. Text message remote monitoring reduced racial disparities in postpartum blood pressure ascertainment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:283-285.

- Hauspurg A, Lemon LS, Quinn BA, et al. A postpartum remote hypertension monitoring protocol implemented at the hospital level. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:685-691.

- Hoppe KK, Thomas N, Zernick M, et al. Telehealth with remote blood pressure monitoring compared to standard care for postpartum hypertension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;S0002-9378(20)30554-doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.027.

- Cairns AE, Tucker KL, Leeson P, et al. Self-management of postnatal hypertension. Hypertension. 2018;72:425-432.

- Pew Research Center. Mobile fact sheet, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- Sayakhot P, Carolan-Olah M. Internet use by pregnant women seeking pregnancy-related information: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:65

2020 Update on abnormal uterine bleeding

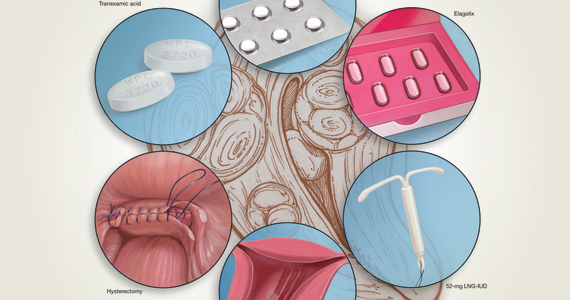

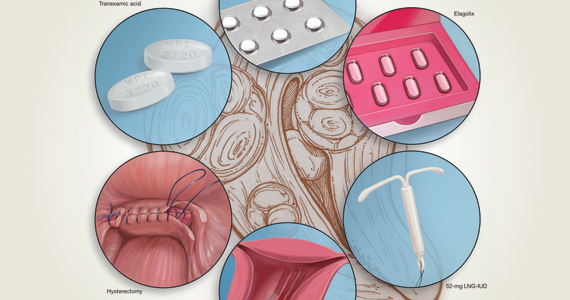

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) continues to be a top reason that women present for gynecologic care. In general, our approach to the management of AUB is to diagnose causes before we prescribe therapy and to offer conservative therapies initially and progress to more invasive measures if indicated.

In this Update, we highlight several new studies that provide evidence for preferential use of certain medical and surgical therapies. In considering conservative therapy for the treatment of AUB, we take a closer look at the efficacy of cyclic progestogens. Another important issue, as more types of endometrial ablation (EA) are being developed and are coming into the market, is the need for additional guidance regarding decisions about EA versus progestin-releasing intrauterine devices (IUDs). Lastly, an unintended consequence of an increased cesarean delivery rate is the development of isthmocele, also known as cesarean scar defect or uterine niche. These defects, which can be bothersome and cause abnormal bleeding, are treated with various techniques. Within the last year, 2 systematic reviews that compare the efficacy of several different approaches and provide guidance have been published.

Is it time to retire cyclic progestogens for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding?

Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Low C, et al. Cyclical progestogens for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(8):CD001016.

In a recent Cochrane Database Systematic Review, Bofill Rodriguez and colleagues looked at the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of oral progestogen therapy for heavy menstrual bleeding.1 They considered progestogen (medroxyprogesterone acetate or norethisterone) in short-cycle use (7 to 10 days in the luteal phase) and long-cycle use (21 days per cycle) in a review of 15 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that included a total of 1,071 women. As this topic had not been updated in 12 years, this review was essential in demonstrating changes that occurred over the past decade.

The primary outcomes of the analysis were menstrual blood loss and treatment satisfaction. Secondary outcomes included the number of days of bleeding, quality of life, adherence and acceptability of treatment, adverse events, and costs.

Classic progestogens fall short compared with newer approaches

Analysis of the data revealed that short-cycle progestogen was inferior to treatment with tranexamic acid, danazol, and the 65-µg progesterone-releasing IUD (Pg-IUD). Of note, the 65-µg Pg-IUD has been off the market since 2001, and danazol is rarely used in current practice. Furthermore, based on 2 trials, cyclic progestogens demonstrated no clear benefit over nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Additionally, long-cycle progestogen therapy was found to be inferior to the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (LNG-IUD), tranexamic acid, and ormeloxifene.

It should be noted that the quality of evidence is still lacking for progestogen therapy, and this study's main limitation is bias, as the women and the researchers were aware of the treatments that were given. This review is helpful, however, for emphasizing the advantage of tranexamic acid and LNG-IUD use in clinical care.

The takeaway. Although it may not necessarily be time to retire the use of cyclic oral progestogens, the 52-mg LNG-IUD or tranexamic acid may be more successful for treating AUB in women who are appropriate candidates.

Cyclic progestogen therapy appears to be less effective for the treatment of AUB when compared with tranexamic acid and the LNG-IUD. It does not appear to be more helpful than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. We frequently offer and prescribe tranexamic acid, 1,300 mg 3 times daily, as a medical alternative to hormonal therapy for up to 5 days monthly for women without thromboembolism risk. Lukes and colleagues published an RCT in 2010 that demonstrated a 40% reduction of bleeding in tranexamic acid–treated women compared with an 8.2% reduction in the placebo group.2

Continue to: Endometrial ablation...

Endometrial ablation: New evidence informs when it could (and could not) be the best option

Bergeron C, Laberge PY, Boutin A, et al. Endometrial ablation or resection versus levonorgestrel intra-uterine system for the treatment of women with heavy menstrual bleeding and a normal uterine cavity: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:302-311.

Vitale SG, Ferrero S, Ciebiera M, et al. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection vs hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding: impact on quality of life and sexuality. Evidence from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32:159-165.

Two systematic reviews evaluated the efficacy of EA in women with abnormal uterine bleeding. One compared EA with the LNG-IUD and reported on safety and efficacy, while the other compared EA with hysterectomy and reported on quality of life.

Bergeron and colleagues reviewed 13 studies that included 884 women to compare the efficacy and safety of EA or resection with the LNG-IUD for the treatment of premenopausal women with AUB.3 They found no significant differences between EA and the LNG-IUD in terms of subsequent hysterectomy (risk ratio [RR] = 1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.60-2.11). It was not surprising that, when looking at age, EA was associated with a higher risk for hysterectomy in women younger than age 42 (RR = 5.26; 95% CI, 1.21-22.91). Conversely, subsequent hysterectomy was less likely with EA compared to LNG-IUD use in women older than 42 years. However, statistical significance was not reached in the older group (RR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.21-1.24).

In the systematic review by Vitale and colleagues, 9 studies met inclusion criteria for a comparison of EA and hysterectomy, with the objective of ascertaining improvement in quality of life and several other measures.4

Although there was significant heterogeneity between assessment tools, both treatment groups experienced similar improvements in quality of life during the first year. However, hysterectomy was more advantageous in terms of improving uterine bleeding and satisfaction in the long term when compared with EA.4

As EA is considered, it is important to continue to counsel about the efficacy of the LNG-IUD, as well as its decreased associated morbidity. Additionally, EA is particularly less effective in younger women.

Continue to: Laparoscopy is best approach for isthomocele management, with caveats...

Laparoscopy is best approach for isthomocele management, with caveats

He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

Vitale SG, Ludwin A, Vilos GA, et al. From hysteroscopy to laparoendoscopic surgery: what is the best surgical approach for symptomatic isthmocele? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:33-52.

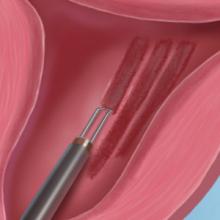

The isthmocele (cesarean scar defect, uterine niche), a known complication of cesarean delivery, represents a myometrial defect in the anterior uterine wall that often presents as abnormal uterine bleeding. It also can be a site for pregnancy-related complications, such as invasive placentation, placenta previa, and uterine rupture.

Two systematic reviews compared surgical strategies for treating isthmocele, including laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy, laparotomy, and vaginal repair.

Laparoscopy reduced isthmocele-associated AUB better than other techniques

A review by He and colleagues analyzed data from 10 pertinent studies (4 RCTs and 6 observational studies) that included 858 patients in total.5 Treatments compared were laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined laparoscopy with hysteroscopy, and vaginal repair for reduction of AUB and isthmocele and diverticulum depth.

The authors found no difference in intraoperative bleeding between the 4 surgical methods (laparotomy was not included in this review). Hysteroscopic surgery was associated with the shortest operative time, while laparoscopy was the longest surgery. In terms of reducing intermittent abnormal bleeding and scar depth, laparoscopic surgery performed better than the other 3 methods.

Approach considerations in isthmocele repair

Vitale and colleagues conducted a systematic review that included 33 publications (28 focused on a single surgical technique, 5 compared different techniques) to examine the effectiveness and risks of various surgical approaches for isthmocele in women with AUB, infertility, or for prevention of obstetric complications.6

Results of their analysis in general favored a laparoscopic approach for patients who desired future fertility, with an improvement rate of 92.7%. Hysteroscopic correction had an 85% improvement rate, and vaginal correction had an 82.5% improvement rate.

Although there were no high-level data to suggest a threshold for myometrial thickness in recommending a surgical approach, the authors provided a helpful algorithm for choosing a route based on a patient's fertility desires. For the asymptomatic patient, they suggest no treatment. In symptomatic patients, the laparoscopic approach is the gold standard but requires significant laparoscopic surgical skill, and a hysteroscopic approach may be considered as an alternative route if the residual myometrial defect is greater than 2.5 to 3.5 mm. For patients who are not considering future reproduction, hysteroscopy is the gold standard as long as the residual myometrial thickness is greater than 2.5 to 3.5 mm.

The takeaway. Of the several methods used for surgical isthmocele management, the laparoscopic approach reduced intermittent abnormal bleeding and scar depth better than other methods. It also was associated with the longest surgical duration. Hysteroscopic surgery was the quickest procedure to perform and is effective in removing the upper valve to promote the elimination of the hematocele and symptoms of abnormal bleeding; however, it does not change the anatomic aspects of the isthmocele in terms of myometrial thickness. Some authors suggested that deciding on the surgical route should be based on fertility desires and the residual thickness of the myometrium. ●

In terms of isthmocele repair, the laparoscopic approach is preferred in patients who desire fertility, as long as the surgeon possesses the skill set to perform this difficult surgery, and as long as the residual myometrium is thicker than 2.5 to 3.5 mm.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Low C, et al. Cyclical progestogens for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(8):CD001016.

- Lukes AS, Moore KA, Muse KN, et al. Tranexamic acid treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled study. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:865-875.

- Bergeron C, Laberge PY, Boutin A, et al. Endometrial ablation or resection versus levonorgestrel intra-uterine system for the treatment of women with heavy menstrual bleeding and a normal uterine cavity: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:302-311.

- Vitale SG, Ferrero S, Ciebiera M, et al. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection vs hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding: impact on quality of life and sexuality. Evidence from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32:159-165.

- He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

- Vitale SG, Ludwin A, Vilos GA, et al. From hysteroscopy to laparoendoscopic surgery: what is the best surgical approach for symptomatic isthmocele? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:33-52.

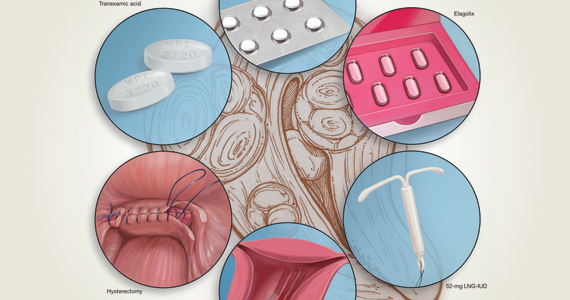

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) continues to be a top reason that women present for gynecologic care. In general, our approach to the management of AUB is to diagnose causes before we prescribe therapy and to offer conservative therapies initially and progress to more invasive measures if indicated.

In this Update, we highlight several new studies that provide evidence for preferential use of certain medical and surgical therapies. In considering conservative therapy for the treatment of AUB, we take a closer look at the efficacy of cyclic progestogens. Another important issue, as more types of endometrial ablation (EA) are being developed and are coming into the market, is the need for additional guidance regarding decisions about EA versus progestin-releasing intrauterine devices (IUDs). Lastly, an unintended consequence of an increased cesarean delivery rate is the development of isthmocele, also known as cesarean scar defect or uterine niche. These defects, which can be bothersome and cause abnormal bleeding, are treated with various techniques. Within the last year, 2 systematic reviews that compare the efficacy of several different approaches and provide guidance have been published.

Is it time to retire cyclic progestogens for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding?

Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Low C, et al. Cyclical progestogens for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(8):CD001016.

In a recent Cochrane Database Systematic Review, Bofill Rodriguez and colleagues looked at the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of oral progestogen therapy for heavy menstrual bleeding.1 They considered progestogen (medroxyprogesterone acetate or norethisterone) in short-cycle use (7 to 10 days in the luteal phase) and long-cycle use (21 days per cycle) in a review of 15 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that included a total of 1,071 women. As this topic had not been updated in 12 years, this review was essential in demonstrating changes that occurred over the past decade.

The primary outcomes of the analysis were menstrual blood loss and treatment satisfaction. Secondary outcomes included the number of days of bleeding, quality of life, adherence and acceptability of treatment, adverse events, and costs.

Classic progestogens fall short compared with newer approaches

Analysis of the data revealed that short-cycle progestogen was inferior to treatment with tranexamic acid, danazol, and the 65-µg progesterone-releasing IUD (Pg-IUD). Of note, the 65-µg Pg-IUD has been off the market since 2001, and danazol is rarely used in current practice. Furthermore, based on 2 trials, cyclic progestogens demonstrated no clear benefit over nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Additionally, long-cycle progestogen therapy was found to be inferior to the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (LNG-IUD), tranexamic acid, and ormeloxifene.

It should be noted that the quality of evidence is still lacking for progestogen therapy, and this study's main limitation is bias, as the women and the researchers were aware of the treatments that were given. This review is helpful, however, for emphasizing the advantage of tranexamic acid and LNG-IUD use in clinical care.

The takeaway. Although it may not necessarily be time to retire the use of cyclic oral progestogens, the 52-mg LNG-IUD or tranexamic acid may be more successful for treating AUB in women who are appropriate candidates.

Cyclic progestogen therapy appears to be less effective for the treatment of AUB when compared with tranexamic acid and the LNG-IUD. It does not appear to be more helpful than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. We frequently offer and prescribe tranexamic acid, 1,300 mg 3 times daily, as a medical alternative to hormonal therapy for up to 5 days monthly for women without thromboembolism risk. Lukes and colleagues published an RCT in 2010 that demonstrated a 40% reduction of bleeding in tranexamic acid–treated women compared with an 8.2% reduction in the placebo group.2

Continue to: Endometrial ablation...

Endometrial ablation: New evidence informs when it could (and could not) be the best option

Bergeron C, Laberge PY, Boutin A, et al. Endometrial ablation or resection versus levonorgestrel intra-uterine system for the treatment of women with heavy menstrual bleeding and a normal uterine cavity: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:302-311.

Vitale SG, Ferrero S, Ciebiera M, et al. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection vs hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding: impact on quality of life and sexuality. Evidence from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32:159-165.

Two systematic reviews evaluated the efficacy of EA in women with abnormal uterine bleeding. One compared EA with the LNG-IUD and reported on safety and efficacy, while the other compared EA with hysterectomy and reported on quality of life.

Bergeron and colleagues reviewed 13 studies that included 884 women to compare the efficacy and safety of EA or resection with the LNG-IUD for the treatment of premenopausal women with AUB.3 They found no significant differences between EA and the LNG-IUD in terms of subsequent hysterectomy (risk ratio [RR] = 1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.60-2.11). It was not surprising that, when looking at age, EA was associated with a higher risk for hysterectomy in women younger than age 42 (RR = 5.26; 95% CI, 1.21-22.91). Conversely, subsequent hysterectomy was less likely with EA compared to LNG-IUD use in women older than 42 years. However, statistical significance was not reached in the older group (RR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.21-1.24).

In the systematic review by Vitale and colleagues, 9 studies met inclusion criteria for a comparison of EA and hysterectomy, with the objective of ascertaining improvement in quality of life and several other measures.4

Although there was significant heterogeneity between assessment tools, both treatment groups experienced similar improvements in quality of life during the first year. However, hysterectomy was more advantageous in terms of improving uterine bleeding and satisfaction in the long term when compared with EA.4

As EA is considered, it is important to continue to counsel about the efficacy of the LNG-IUD, as well as its decreased associated morbidity. Additionally, EA is particularly less effective in younger women.

Continue to: Laparoscopy is best approach for isthomocele management, with caveats...

Laparoscopy is best approach for isthomocele management, with caveats

He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

Vitale SG, Ludwin A, Vilos GA, et al. From hysteroscopy to laparoendoscopic surgery: what is the best surgical approach for symptomatic isthmocele? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:33-52.

The isthmocele (cesarean scar defect, uterine niche), a known complication of cesarean delivery, represents a myometrial defect in the anterior uterine wall that often presents as abnormal uterine bleeding. It also can be a site for pregnancy-related complications, such as invasive placentation, placenta previa, and uterine rupture.

Two systematic reviews compared surgical strategies for treating isthmocele, including laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy, laparotomy, and vaginal repair.

Laparoscopy reduced isthmocele-associated AUB better than other techniques

A review by He and colleagues analyzed data from 10 pertinent studies (4 RCTs and 6 observational studies) that included 858 patients in total.5 Treatments compared were laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined laparoscopy with hysteroscopy, and vaginal repair for reduction of AUB and isthmocele and diverticulum depth.

The authors found no difference in intraoperative bleeding between the 4 surgical methods (laparotomy was not included in this review). Hysteroscopic surgery was associated with the shortest operative time, while laparoscopy was the longest surgery. In terms of reducing intermittent abnormal bleeding and scar depth, laparoscopic surgery performed better than the other 3 methods.

Approach considerations in isthmocele repair

Vitale and colleagues conducted a systematic review that included 33 publications (28 focused on a single surgical technique, 5 compared different techniques) to examine the effectiveness and risks of various surgical approaches for isthmocele in women with AUB, infertility, or for prevention of obstetric complications.6

Results of their analysis in general favored a laparoscopic approach for patients who desired future fertility, with an improvement rate of 92.7%. Hysteroscopic correction had an 85% improvement rate, and vaginal correction had an 82.5% improvement rate.

Although there were no high-level data to suggest a threshold for myometrial thickness in recommending a surgical approach, the authors provided a helpful algorithm for choosing a route based on a patient's fertility desires. For the asymptomatic patient, they suggest no treatment. In symptomatic patients, the laparoscopic approach is the gold standard but requires significant laparoscopic surgical skill, and a hysteroscopic approach may be considered as an alternative route if the residual myometrial defect is greater than 2.5 to 3.5 mm. For patients who are not considering future reproduction, hysteroscopy is the gold standard as long as the residual myometrial thickness is greater than 2.5 to 3.5 mm.

The takeaway. Of the several methods used for surgical isthmocele management, the laparoscopic approach reduced intermittent abnormal bleeding and scar depth better than other methods. It also was associated with the longest surgical duration. Hysteroscopic surgery was the quickest procedure to perform and is effective in removing the upper valve to promote the elimination of the hematocele and symptoms of abnormal bleeding; however, it does not change the anatomic aspects of the isthmocele in terms of myometrial thickness. Some authors suggested that deciding on the surgical route should be based on fertility desires and the residual thickness of the myometrium. ●

In terms of isthmocele repair, the laparoscopic approach is preferred in patients who desire fertility, as long as the surgeon possesses the skill set to perform this difficult surgery, and as long as the residual myometrium is thicker than 2.5 to 3.5 mm.

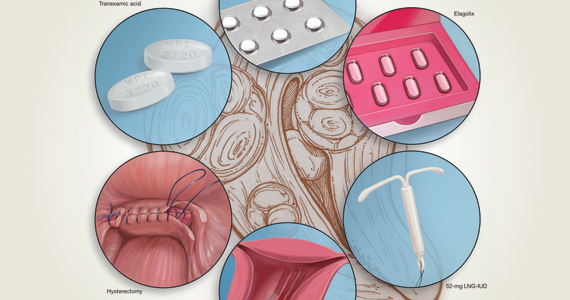

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) continues to be a top reason that women present for gynecologic care. In general, our approach to the management of AUB is to diagnose causes before we prescribe therapy and to offer conservative therapies initially and progress to more invasive measures if indicated.

In this Update, we highlight several new studies that provide evidence for preferential use of certain medical and surgical therapies. In considering conservative therapy for the treatment of AUB, we take a closer look at the efficacy of cyclic progestogens. Another important issue, as more types of endometrial ablation (EA) are being developed and are coming into the market, is the need for additional guidance regarding decisions about EA versus progestin-releasing intrauterine devices (IUDs). Lastly, an unintended consequence of an increased cesarean delivery rate is the development of isthmocele, also known as cesarean scar defect or uterine niche. These defects, which can be bothersome and cause abnormal bleeding, are treated with various techniques. Within the last year, 2 systematic reviews that compare the efficacy of several different approaches and provide guidance have been published.

Is it time to retire cyclic progestogens for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding?

Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Low C, et al. Cyclical progestogens for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(8):CD001016.

In a recent Cochrane Database Systematic Review, Bofill Rodriguez and colleagues looked at the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of oral progestogen therapy for heavy menstrual bleeding.1 They considered progestogen (medroxyprogesterone acetate or norethisterone) in short-cycle use (7 to 10 days in the luteal phase) and long-cycle use (21 days per cycle) in a review of 15 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that included a total of 1,071 women. As this topic had not been updated in 12 years, this review was essential in demonstrating changes that occurred over the past decade.

The primary outcomes of the analysis were menstrual blood loss and treatment satisfaction. Secondary outcomes included the number of days of bleeding, quality of life, adherence and acceptability of treatment, adverse events, and costs.

Classic progestogens fall short compared with newer approaches

Analysis of the data revealed that short-cycle progestogen was inferior to treatment with tranexamic acid, danazol, and the 65-µg progesterone-releasing IUD (Pg-IUD). Of note, the 65-µg Pg-IUD has been off the market since 2001, and danazol is rarely used in current practice. Furthermore, based on 2 trials, cyclic progestogens demonstrated no clear benefit over nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Additionally, long-cycle progestogen therapy was found to be inferior to the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (LNG-IUD), tranexamic acid, and ormeloxifene.

It should be noted that the quality of evidence is still lacking for progestogen therapy, and this study's main limitation is bias, as the women and the researchers were aware of the treatments that were given. This review is helpful, however, for emphasizing the advantage of tranexamic acid and LNG-IUD use in clinical care.

The takeaway. Although it may not necessarily be time to retire the use of cyclic oral progestogens, the 52-mg LNG-IUD or tranexamic acid may be more successful for treating AUB in women who are appropriate candidates.

Cyclic progestogen therapy appears to be less effective for the treatment of AUB when compared with tranexamic acid and the LNG-IUD. It does not appear to be more helpful than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. We frequently offer and prescribe tranexamic acid, 1,300 mg 3 times daily, as a medical alternative to hormonal therapy for up to 5 days monthly for women without thromboembolism risk. Lukes and colleagues published an RCT in 2010 that demonstrated a 40% reduction of bleeding in tranexamic acid–treated women compared with an 8.2% reduction in the placebo group.2

Continue to: Endometrial ablation...

Endometrial ablation: New evidence informs when it could (and could not) be the best option

Bergeron C, Laberge PY, Boutin A, et al. Endometrial ablation or resection versus levonorgestrel intra-uterine system for the treatment of women with heavy menstrual bleeding and a normal uterine cavity: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:302-311.

Vitale SG, Ferrero S, Ciebiera M, et al. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection vs hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding: impact on quality of life and sexuality. Evidence from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32:159-165.

Two systematic reviews evaluated the efficacy of EA in women with abnormal uterine bleeding. One compared EA with the LNG-IUD and reported on safety and efficacy, while the other compared EA with hysterectomy and reported on quality of life.

Bergeron and colleagues reviewed 13 studies that included 884 women to compare the efficacy and safety of EA or resection with the LNG-IUD for the treatment of premenopausal women with AUB.3 They found no significant differences between EA and the LNG-IUD in terms of subsequent hysterectomy (risk ratio [RR] = 1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.60-2.11). It was not surprising that, when looking at age, EA was associated with a higher risk for hysterectomy in women younger than age 42 (RR = 5.26; 95% CI, 1.21-22.91). Conversely, subsequent hysterectomy was less likely with EA compared to LNG-IUD use in women older than 42 years. However, statistical significance was not reached in the older group (RR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.21-1.24).

In the systematic review by Vitale and colleagues, 9 studies met inclusion criteria for a comparison of EA and hysterectomy, with the objective of ascertaining improvement in quality of life and several other measures.4

Although there was significant heterogeneity between assessment tools, both treatment groups experienced similar improvements in quality of life during the first year. However, hysterectomy was more advantageous in terms of improving uterine bleeding and satisfaction in the long term when compared with EA.4

As EA is considered, it is important to continue to counsel about the efficacy of the LNG-IUD, as well as its decreased associated morbidity. Additionally, EA is particularly less effective in younger women.

Continue to: Laparoscopy is best approach for isthomocele management, with caveats...

Laparoscopy is best approach for isthomocele management, with caveats

He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

Vitale SG, Ludwin A, Vilos GA, et al. From hysteroscopy to laparoendoscopic surgery: what is the best surgical approach for symptomatic isthmocele? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:33-52.

The isthmocele (cesarean scar defect, uterine niche), a known complication of cesarean delivery, represents a myometrial defect in the anterior uterine wall that often presents as abnormal uterine bleeding. It also can be a site for pregnancy-related complications, such as invasive placentation, placenta previa, and uterine rupture.

Two systematic reviews compared surgical strategies for treating isthmocele, including laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy, laparotomy, and vaginal repair.

Laparoscopy reduced isthmocele-associated AUB better than other techniques

A review by He and colleagues analyzed data from 10 pertinent studies (4 RCTs and 6 observational studies) that included 858 patients in total.5 Treatments compared were laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined laparoscopy with hysteroscopy, and vaginal repair for reduction of AUB and isthmocele and diverticulum depth.

The authors found no difference in intraoperative bleeding between the 4 surgical methods (laparotomy was not included in this review). Hysteroscopic surgery was associated with the shortest operative time, while laparoscopy was the longest surgery. In terms of reducing intermittent abnormal bleeding and scar depth, laparoscopic surgery performed better than the other 3 methods.

Approach considerations in isthmocele repair

Vitale and colleagues conducted a systematic review that included 33 publications (28 focused on a single surgical technique, 5 compared different techniques) to examine the effectiveness and risks of various surgical approaches for isthmocele in women with AUB, infertility, or for prevention of obstetric complications.6

Results of their analysis in general favored a laparoscopic approach for patients who desired future fertility, with an improvement rate of 92.7%. Hysteroscopic correction had an 85% improvement rate, and vaginal correction had an 82.5% improvement rate.

Although there were no high-level data to suggest a threshold for myometrial thickness in recommending a surgical approach, the authors provided a helpful algorithm for choosing a route based on a patient's fertility desires. For the asymptomatic patient, they suggest no treatment. In symptomatic patients, the laparoscopic approach is the gold standard but requires significant laparoscopic surgical skill, and a hysteroscopic approach may be considered as an alternative route if the residual myometrial defect is greater than 2.5 to 3.5 mm. For patients who are not considering future reproduction, hysteroscopy is the gold standard as long as the residual myometrial thickness is greater than 2.5 to 3.5 mm.

The takeaway. Of the several methods used for surgical isthmocele management, the laparoscopic approach reduced intermittent abnormal bleeding and scar depth better than other methods. It also was associated with the longest surgical duration. Hysteroscopic surgery was the quickest procedure to perform and is effective in removing the upper valve to promote the elimination of the hematocele and symptoms of abnormal bleeding; however, it does not change the anatomic aspects of the isthmocele in terms of myometrial thickness. Some authors suggested that deciding on the surgical route should be based on fertility desires and the residual thickness of the myometrium. ●

In terms of isthmocele repair, the laparoscopic approach is preferred in patients who desire fertility, as long as the surgeon possesses the skill set to perform this difficult surgery, and as long as the residual myometrium is thicker than 2.5 to 3.5 mm.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Low C, et al. Cyclical progestogens for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(8):CD001016.

- Lukes AS, Moore KA, Muse KN, et al. Tranexamic acid treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled study. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:865-875.

- Bergeron C, Laberge PY, Boutin A, et al. Endometrial ablation or resection versus levonorgestrel intra-uterine system for the treatment of women with heavy menstrual bleeding and a normal uterine cavity: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:302-311.

- Vitale SG, Ferrero S, Ciebiera M, et al. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection vs hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding: impact on quality of life and sexuality. Evidence from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32:159-165.

- He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

- Vitale SG, Ludwin A, Vilos GA, et al. From hysteroscopy to laparoendoscopic surgery: what is the best surgical approach for symptomatic isthmocele? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:33-52.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Low C, et al. Cyclical progestogens for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(8):CD001016.

- Lukes AS, Moore KA, Muse KN, et al. Tranexamic acid treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled study. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:865-875.

- Bergeron C, Laberge PY, Boutin A, et al. Endometrial ablation or resection versus levonorgestrel intra-uterine system for the treatment of women with heavy menstrual bleeding and a normal uterine cavity: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:302-311.

- Vitale SG, Ferrero S, Ciebiera M, et al. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection vs hysterectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding: impact on quality of life and sexuality. Evidence from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32:159-165.

- He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

- Vitale SG, Ludwin A, Vilos GA, et al. From hysteroscopy to laparoendoscopic surgery: what is the best surgical approach for symptomatic isthmocele? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:33-52.

Should all women with a history of OASI have a mediolateral episiotomy at their subsequent delivery?

Van Bavel J, Ravelli AC, Abu-Hanna A, et al. Risk factors for the recurrence of obstetrical anal sphincter injury and the role of a mediolateral episiotomy: an analysis of a national registry. BJOG. 2020;127:951-956.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

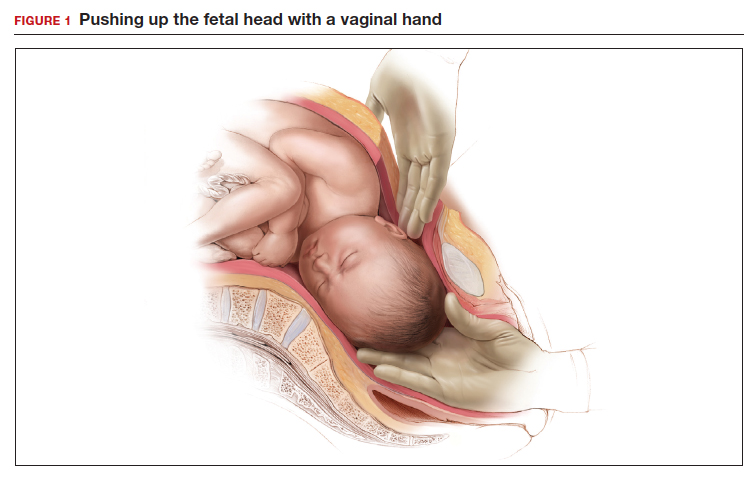

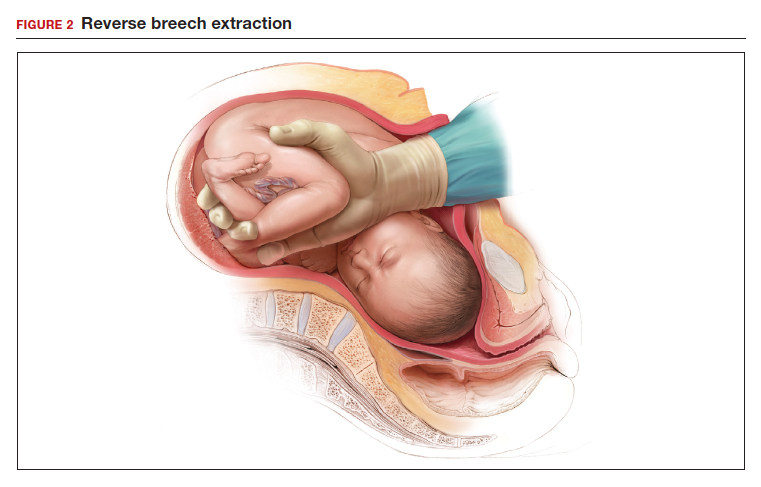

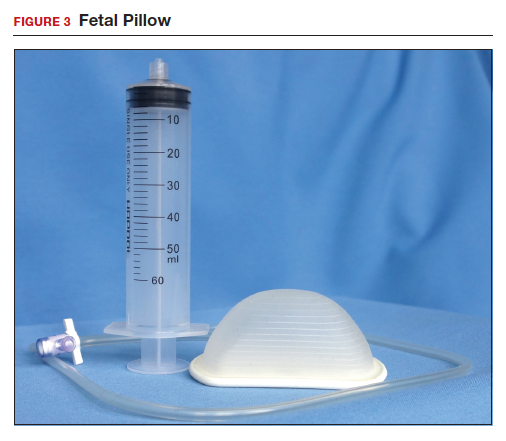

Women with a history of OASI are at increased risk for recurrence in a subsequent delivery. Higher rates of anal and fecal incontinence are reported in women with recurrent OASI (rOASI) compared with women who had an OASI only in their first delivery. Previous studies have reported recurrence rates of 5% to 7%,1 and some suggested that MLE may be protective, but standardized recommendations for mode of delivery and use of MLE currently are not available.

Recently, van Bavel and colleagues sought to determine the rate of rOASI in their population as well as the factors that increase and decrease the risk of this complication.

Details of the study

This cohort study used data from the Dutch Perinatal Registry (Perined) that included 268,607 women who had their first and second deliveries (singleton, term, vertex, < 43 weeks) vaginally in 2000–2009. The study’s primary objective was to determine the rate of rOASI in women who had OASI in their first delivery. The secondary objectives were to identify risk factors for rOASI and to assess the effect of MLE. For the purposes of this study, OASI was defined as subtotal and total rupture of the perineum, or grades 3A-4 as defined by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.2

Within this cohort, 9,943 women had an OASI in their first delivery (4%), and the rate of rOASI was 5.8% (579 of 9,943). After multivariate analysis, the risk factors for rOASI were birth weight of 4,000 g or greater (odds ratio [OR], 2.1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.6–2.6) and duration of the second stage of labor of 30 minutes or longer (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.4–2.3).

The MLE rate was 40.8% (4,054 of 9,943) and was associated with a lower rate of rOASI (OR, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.3–0.4). This association persisted when delivery type was separated into spontaneous and operative vaginal deliveries, with the number of MLEs needed to prevent one rOASI of 22 and 8, respectively. Birth weight of less than 3,000 g also was noted to be protective against rOASI (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3–0.9).

Based on these findings, as well as comparisons to previous studies, the authors concluded that MLE could be considered for routine use or at least discussed with all women with a prior OASI for prevention of rOASI.

Continue to: Study strengths and limitations...

Study strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was the large number of deliveries and the wide variation of practice included in the registry database, which promotes the generalizability of the results and reduces bias. This also provides an adequate base on which to determine an accurate rate of rOASI in the Dutch population.

One study limitation is that information is not available regarding how the episiotomies were performed (specifically, angle of incision), delivery techniques (“hands on” vs “hands off”), and indication for the episiotomy. Additional limitations suggested are that clinicians who perform an episiotomy may have an inherent bias regarding the protective nature of the procedure and may miss a rOASI due to inadequate examination postprocedure, overestimating its protective effect.

Finally, the relatively high rate of MLE and low rate of cesarean delivery (6.9%) in this study are specific to the Netherlands and do not reflect the obstetric practices used in many other countries. Generalizability of these results in the context of much lower MLE and higher cesarean delivery rates (as in the United States) would therefore be in question.●

Prevention of rOASI is important, as fecal incontinence is debilitating and difficult to treat. While this study provides evidence that MLE may protect against this complication, its results may not be generalizable to all patient or clinician populations. Differences in baseline rate of MLE and cesarean delivery, technique, indication, and comfort with repair—all not evaluated in this study—must be taken into account when counseling OASI patients about their options for delivery and the use of MLE in a subsequent pregnancy.

JAIMEY M. PAULI, MD

- Van Bavel J, Ravelli AC, Abu-Hanna A, et al. Risk factors for the recurrence of obstetrical anal sphincter injury and the role of a mediolateral episiotomy: an analysis of a national registry. BJOG. 2020;127:951-956.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Green-top guideline No. 29: the management of third- and fourth-degree perineal tears. June 2014. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg-29.pdf. Accessed June 12, 2020.

Van Bavel J, Ravelli AC, Abu-Hanna A, et al. Risk factors for the recurrence of obstetrical anal sphincter injury and the role of a mediolateral episiotomy: an analysis of a national registry. BJOG. 2020;127:951-956.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Women with a history of OASI are at increased risk for recurrence in a subsequent delivery. Higher rates of anal and fecal incontinence are reported in women with recurrent OASI (rOASI) compared with women who had an OASI only in their first delivery. Previous studies have reported recurrence rates of 5% to 7%,1 and some suggested that MLE may be protective, but standardized recommendations for mode of delivery and use of MLE currently are not available.

Recently, van Bavel and colleagues sought to determine the rate of rOASI in their population as well as the factors that increase and decrease the risk of this complication.

Details of the study

This cohort study used data from the Dutch Perinatal Registry (Perined) that included 268,607 women who had their first and second deliveries (singleton, term, vertex, < 43 weeks) vaginally in 2000–2009. The study’s primary objective was to determine the rate of rOASI in women who had OASI in their first delivery. The secondary objectives were to identify risk factors for rOASI and to assess the effect of MLE. For the purposes of this study, OASI was defined as subtotal and total rupture of the perineum, or grades 3A-4 as defined by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.2

Within this cohort, 9,943 women had an OASI in their first delivery (4%), and the rate of rOASI was 5.8% (579 of 9,943). After multivariate analysis, the risk factors for rOASI were birth weight of 4,000 g or greater (odds ratio [OR], 2.1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.6–2.6) and duration of the second stage of labor of 30 minutes or longer (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.4–2.3).

The MLE rate was 40.8% (4,054 of 9,943) and was associated with a lower rate of rOASI (OR, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.3–0.4). This association persisted when delivery type was separated into spontaneous and operative vaginal deliveries, with the number of MLEs needed to prevent one rOASI of 22 and 8, respectively. Birth weight of less than 3,000 g also was noted to be protective against rOASI (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3–0.9).