User login

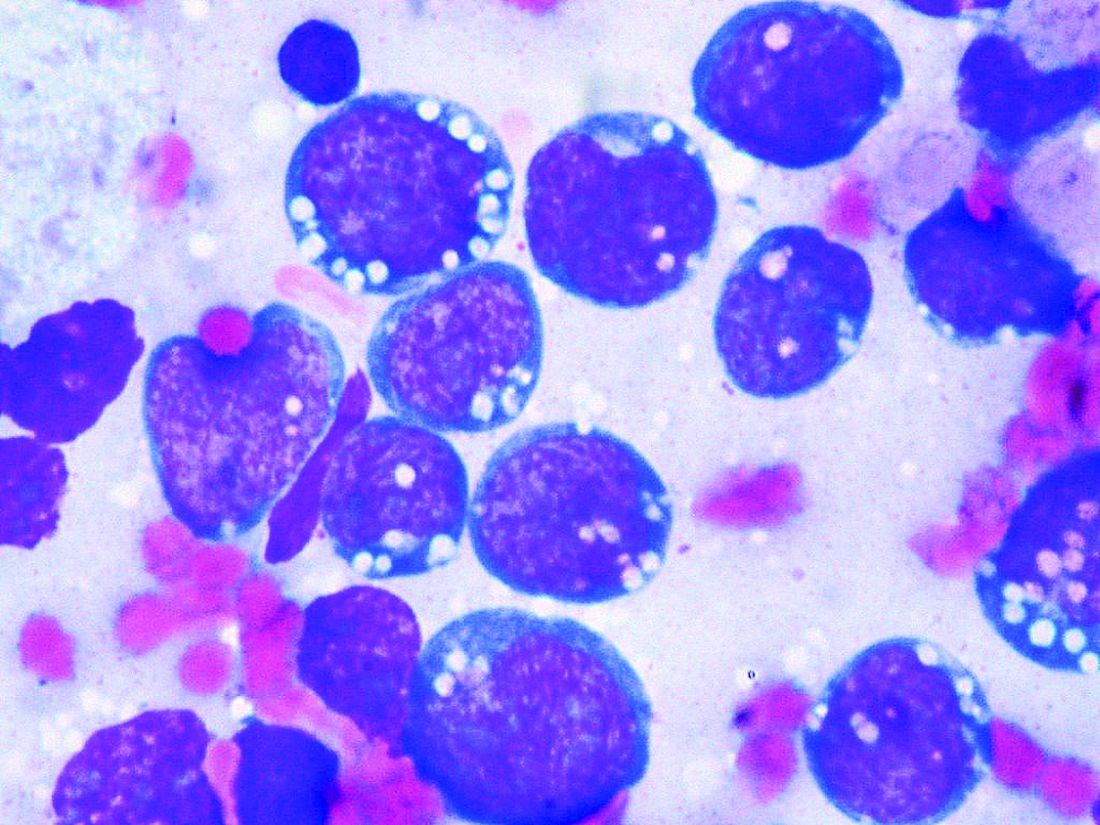

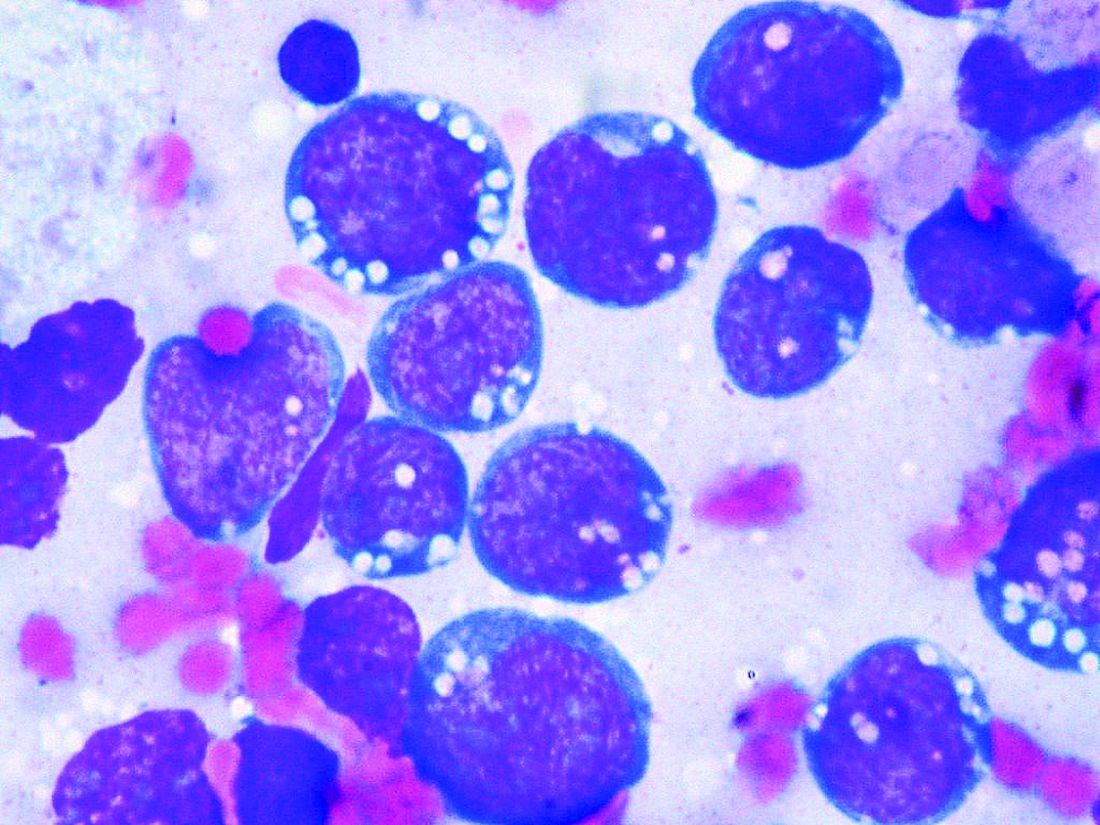

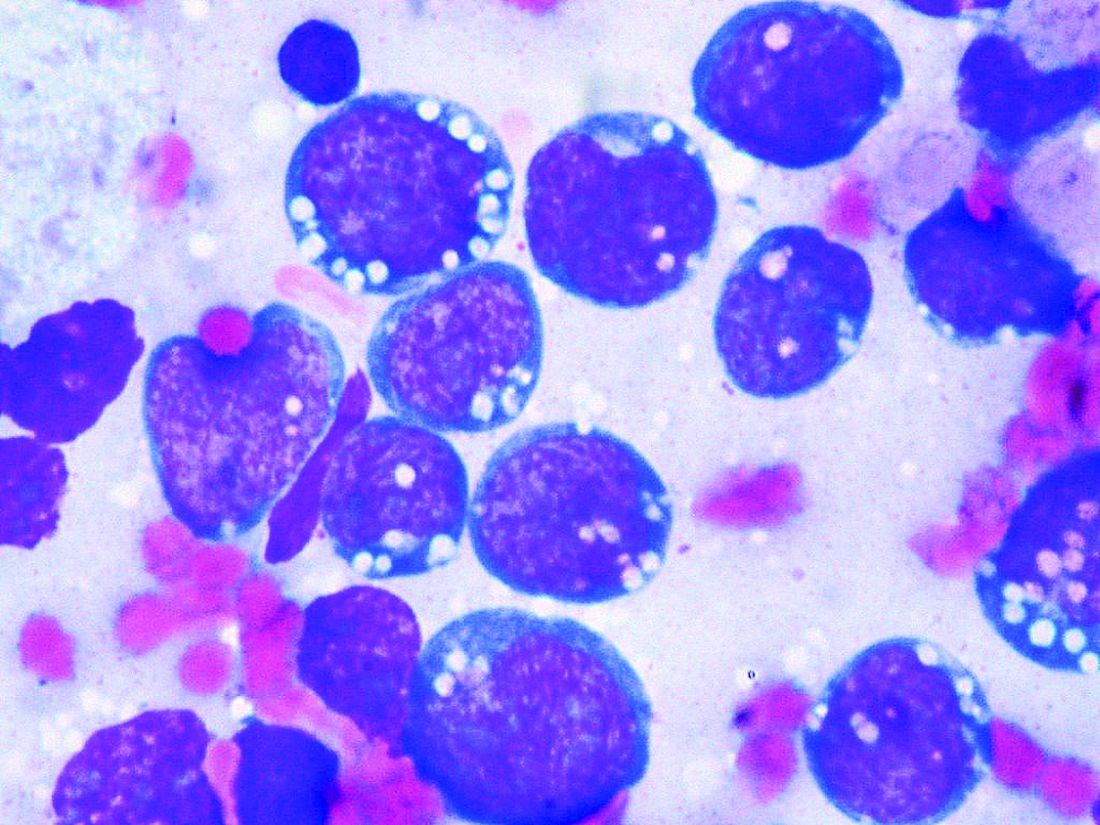

New EPOCH for adult patients with Burkitt lymphoma

Adult patients with Burkitt lymphoma can achieve equally sound survival outcomes with dose-adjusted chemotherapy versus high-intensity regimens, but can do so while avoiding the severe toxicities, U.S. study data shows.

Although Burkitt lymphoma is the most common B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children, it accounts for only 1% to 2% of adult lymphoma cases.

Highly dose-intensive chemotherapy regimens, developed for children and young adults, have rendered the disease curable. But older patients in particular, and patients with comorbidities such as HIV, can suffer severe adverse effects, as well as late sequelae like second malignancies.

Mark Roschewski, MD, from the lymphoid malignancies branch at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md., and colleagues therefore examined whether a dose-adjusted regimen would maintain outcomes while reducing toxicities.

Tailoring treatment with etoposide, doxorubicin, and vincristine with prednisone, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (EPOCH-R) to whether patients had high- or low-risk disease, they achieved 4-year survival rates of higher than 85%.

The research, published by the Journal of Clinical Oncology, also showed that patients taking the regimen, which was well tolerated, had low rates of relapse in the central nervous system.

The team reports that their results with the dose-adjusted regimen “significantly improve on the complexity, cost, and toxicity profile of other regimens,” also highlighting that it is administered on an outpatient basis.

As the outcomes also “compare favorably” with those with high intensity regimens, they say the findings “support our treatment strategies to ameliorate toxicity while maintaining efficacy.”

Importantly, they suggest highly dose-intensive chemotherapy is unnecessary for cure, and carefully defined low-risk patients may be treated with limited chemotherapy.

Dr. Roschewski said in an interview that, in patients aged 40 years and older, dose-adjusted EPOCH-R is “probably the preferred choice,” despite its “weakness” in controlling the disease in patients with active CNS involvement.

However, the “real question” is what to use in younger patients, Dr. Roschewski said, as the “unknown” is whether the additional magnitude of a high-intensity regimen that “gets into the CNS” outweighs the risk of toxicities.

“What was important about our study,” he said, was that patients with CNS involvement “did the worst but it was equally split among patients that died of toxicity and patients that progressed.”

In other words, each choice increases one risk while decreasing another. “So I would have to have that discussion with the patient, and individual patient decisions are typically based on the details,” said Dr. Roschewski.

One issue, however, that could limit the adoption of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R is that, without a randomized study comparing it directly with a high-intensity regimen, clinicians may to stick to what they know.

Dr. Roschewski said that “this is particularly true of more experienced clinicians.”

“They’re less likely, I think, to adopt something else outside of a randomized study because our natural inclination with this disease has always been dose intensity is critical. ... This is a dogma, and to shift from that probably does require a higher level of evidence, at least for some practitioners,” he explained.

Further study details

Following a pilot study of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R in 30 adult patients in which the authors say the regimen showed “high efficacy,” they enrolled 113 patients with untreated Burkitt lymphoma at 22 centers between June 2010 and May 2017.

The patients were divided into low-risk and high-risk categories, with low-risk defined as stage 1 or 2 disease, normal lactate dehydrogenase levels, ECOG performance status ≤ 1, and no tumor mass ≥ 7 cm.

High-risk patients were given six cycles of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R (with rituximab on day 1 only) along with CNS prophylaxis or active therapy with intrathecal methotrexate.

In contrast, low-risk patients were given two cycles of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R, with rituximab on days 1 and 5, followed by positron emission tomography.

If that was negative, the patients had one additional treatment cycle and no CNS prophylaxis, but if it was positive, they were given four additional cycles, plus intrathecal methotrexate.

Of the 113 patients enrolled, 79% were male, median age was 49 years, and 62% were aged at least 40 years, including 26% aged at least 60 years.

The team determined that 13% of the patients were of low risk, 87% were high risk, and 11% had cerebrospinal fluid involvement. One-quarter (24.7%) were HIV positive, with a median CD4+ T-cell count of 268 cells/mm3.

The majority (87%) of low-risk patients received three treatment cycles, and 82% of high-risk patents were administered six treatment cycles.

Over a median follow-up of 58.7 months (4.9 years), the 4-year event-free survival (EFS) rate across the whole cohort was 84.5% and overall survival was 87%.

At the time of analysis, all low-risk patients were in remission; among high-risk patients, the 4-year EFS was 82.1% and overall survival was 84.9%.

The team reports that treatment was equally effective across age groups, and irrespective of HIV status and International Prognostic Index risk group.

Only 2% of high-risk patients with no pretreatment evidence of CNS involvement had relapses in the brain parenchyma. Just over half (55%) of patients with cerebrospinal fluid involvement at presentation experienced disease progression or died.

Five patients died of treatment-related toxicity. Grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia occurred during 17% of cycles, and febrile neutropenia was seen during 16%. Tumor lysis syndrome was rare, occurring in 5% of patients.

Next, the researchers are planning on focusing on CNS disease, looking at EPOCH-R as the backbone and adding intrathecal methotrexate and an additional targeted agent with known CNS penetration.

Dr. Roschewski said that is “a very attractive strategy and ... we will initiate enrollment in that study probably in the next couple of months here at the NCI,” he added, noting that it will be an early phase 1 study.

Another issue he identified that “doesn’t get spoken about quite as much but I do think is important is potentially working on supportive care guidelines for how we manage these patients.” Dr. Roschewski explained, “One of the things you see over and over in these Burkitt lymphoma studies is that some patients don’t make it through therapy because they’re so sick at the beginning, and they have certain risks.

“I think simply improving that type of care, independent of what regimen is used, can potentially improve the outcomes across patient groups.”

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, AIDS Malignancy Consortium, and the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and Lymphoid Malignancies Branch. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Adult patients with Burkitt lymphoma can achieve equally sound survival outcomes with dose-adjusted chemotherapy versus high-intensity regimens, but can do so while avoiding the severe toxicities, U.S. study data shows.

Although Burkitt lymphoma is the most common B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children, it accounts for only 1% to 2% of adult lymphoma cases.

Highly dose-intensive chemotherapy regimens, developed for children and young adults, have rendered the disease curable. But older patients in particular, and patients with comorbidities such as HIV, can suffer severe adverse effects, as well as late sequelae like second malignancies.

Mark Roschewski, MD, from the lymphoid malignancies branch at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md., and colleagues therefore examined whether a dose-adjusted regimen would maintain outcomes while reducing toxicities.

Tailoring treatment with etoposide, doxorubicin, and vincristine with prednisone, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (EPOCH-R) to whether patients had high- or low-risk disease, they achieved 4-year survival rates of higher than 85%.

The research, published by the Journal of Clinical Oncology, also showed that patients taking the regimen, which was well tolerated, had low rates of relapse in the central nervous system.

The team reports that their results with the dose-adjusted regimen “significantly improve on the complexity, cost, and toxicity profile of other regimens,” also highlighting that it is administered on an outpatient basis.

As the outcomes also “compare favorably” with those with high intensity regimens, they say the findings “support our treatment strategies to ameliorate toxicity while maintaining efficacy.”

Importantly, they suggest highly dose-intensive chemotherapy is unnecessary for cure, and carefully defined low-risk patients may be treated with limited chemotherapy.

Dr. Roschewski said in an interview that, in patients aged 40 years and older, dose-adjusted EPOCH-R is “probably the preferred choice,” despite its “weakness” in controlling the disease in patients with active CNS involvement.

However, the “real question” is what to use in younger patients, Dr. Roschewski said, as the “unknown” is whether the additional magnitude of a high-intensity regimen that “gets into the CNS” outweighs the risk of toxicities.

“What was important about our study,” he said, was that patients with CNS involvement “did the worst but it was equally split among patients that died of toxicity and patients that progressed.”

In other words, each choice increases one risk while decreasing another. “So I would have to have that discussion with the patient, and individual patient decisions are typically based on the details,” said Dr. Roschewski.

One issue, however, that could limit the adoption of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R is that, without a randomized study comparing it directly with a high-intensity regimen, clinicians may to stick to what they know.

Dr. Roschewski said that “this is particularly true of more experienced clinicians.”

“They’re less likely, I think, to adopt something else outside of a randomized study because our natural inclination with this disease has always been dose intensity is critical. ... This is a dogma, and to shift from that probably does require a higher level of evidence, at least for some practitioners,” he explained.

Further study details

Following a pilot study of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R in 30 adult patients in which the authors say the regimen showed “high efficacy,” they enrolled 113 patients with untreated Burkitt lymphoma at 22 centers between June 2010 and May 2017.

The patients were divided into low-risk and high-risk categories, with low-risk defined as stage 1 or 2 disease, normal lactate dehydrogenase levels, ECOG performance status ≤ 1, and no tumor mass ≥ 7 cm.

High-risk patients were given six cycles of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R (with rituximab on day 1 only) along with CNS prophylaxis or active therapy with intrathecal methotrexate.

In contrast, low-risk patients were given two cycles of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R, with rituximab on days 1 and 5, followed by positron emission tomography.

If that was negative, the patients had one additional treatment cycle and no CNS prophylaxis, but if it was positive, they were given four additional cycles, plus intrathecal methotrexate.

Of the 113 patients enrolled, 79% were male, median age was 49 years, and 62% were aged at least 40 years, including 26% aged at least 60 years.

The team determined that 13% of the patients were of low risk, 87% were high risk, and 11% had cerebrospinal fluid involvement. One-quarter (24.7%) were HIV positive, with a median CD4+ T-cell count of 268 cells/mm3.

The majority (87%) of low-risk patients received three treatment cycles, and 82% of high-risk patents were administered six treatment cycles.

Over a median follow-up of 58.7 months (4.9 years), the 4-year event-free survival (EFS) rate across the whole cohort was 84.5% and overall survival was 87%.

At the time of analysis, all low-risk patients were in remission; among high-risk patients, the 4-year EFS was 82.1% and overall survival was 84.9%.

The team reports that treatment was equally effective across age groups, and irrespective of HIV status and International Prognostic Index risk group.

Only 2% of high-risk patients with no pretreatment evidence of CNS involvement had relapses in the brain parenchyma. Just over half (55%) of patients with cerebrospinal fluid involvement at presentation experienced disease progression or died.

Five patients died of treatment-related toxicity. Grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia occurred during 17% of cycles, and febrile neutropenia was seen during 16%. Tumor lysis syndrome was rare, occurring in 5% of patients.

Next, the researchers are planning on focusing on CNS disease, looking at EPOCH-R as the backbone and adding intrathecal methotrexate and an additional targeted agent with known CNS penetration.

Dr. Roschewski said that is “a very attractive strategy and ... we will initiate enrollment in that study probably in the next couple of months here at the NCI,” he added, noting that it will be an early phase 1 study.

Another issue he identified that “doesn’t get spoken about quite as much but I do think is important is potentially working on supportive care guidelines for how we manage these patients.” Dr. Roschewski explained, “One of the things you see over and over in these Burkitt lymphoma studies is that some patients don’t make it through therapy because they’re so sick at the beginning, and they have certain risks.

“I think simply improving that type of care, independent of what regimen is used, can potentially improve the outcomes across patient groups.”

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, AIDS Malignancy Consortium, and the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and Lymphoid Malignancies Branch. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Adult patients with Burkitt lymphoma can achieve equally sound survival outcomes with dose-adjusted chemotherapy versus high-intensity regimens, but can do so while avoiding the severe toxicities, U.S. study data shows.

Although Burkitt lymphoma is the most common B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children, it accounts for only 1% to 2% of adult lymphoma cases.

Highly dose-intensive chemotherapy regimens, developed for children and young adults, have rendered the disease curable. But older patients in particular, and patients with comorbidities such as HIV, can suffer severe adverse effects, as well as late sequelae like second malignancies.

Mark Roschewski, MD, from the lymphoid malignancies branch at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md., and colleagues therefore examined whether a dose-adjusted regimen would maintain outcomes while reducing toxicities.

Tailoring treatment with etoposide, doxorubicin, and vincristine with prednisone, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (EPOCH-R) to whether patients had high- or low-risk disease, they achieved 4-year survival rates of higher than 85%.

The research, published by the Journal of Clinical Oncology, also showed that patients taking the regimen, which was well tolerated, had low rates of relapse in the central nervous system.

The team reports that their results with the dose-adjusted regimen “significantly improve on the complexity, cost, and toxicity profile of other regimens,” also highlighting that it is administered on an outpatient basis.

As the outcomes also “compare favorably” with those with high intensity regimens, they say the findings “support our treatment strategies to ameliorate toxicity while maintaining efficacy.”

Importantly, they suggest highly dose-intensive chemotherapy is unnecessary for cure, and carefully defined low-risk patients may be treated with limited chemotherapy.

Dr. Roschewski said in an interview that, in patients aged 40 years and older, dose-adjusted EPOCH-R is “probably the preferred choice,” despite its “weakness” in controlling the disease in patients with active CNS involvement.

However, the “real question” is what to use in younger patients, Dr. Roschewski said, as the “unknown” is whether the additional magnitude of a high-intensity regimen that “gets into the CNS” outweighs the risk of toxicities.

“What was important about our study,” he said, was that patients with CNS involvement “did the worst but it was equally split among patients that died of toxicity and patients that progressed.”

In other words, each choice increases one risk while decreasing another. “So I would have to have that discussion with the patient, and individual patient decisions are typically based on the details,” said Dr. Roschewski.

One issue, however, that could limit the adoption of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R is that, without a randomized study comparing it directly with a high-intensity regimen, clinicians may to stick to what they know.

Dr. Roschewski said that “this is particularly true of more experienced clinicians.”

“They’re less likely, I think, to adopt something else outside of a randomized study because our natural inclination with this disease has always been dose intensity is critical. ... This is a dogma, and to shift from that probably does require a higher level of evidence, at least for some practitioners,” he explained.

Further study details

Following a pilot study of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R in 30 adult patients in which the authors say the regimen showed “high efficacy,” they enrolled 113 patients with untreated Burkitt lymphoma at 22 centers between June 2010 and May 2017.

The patients were divided into low-risk and high-risk categories, with low-risk defined as stage 1 or 2 disease, normal lactate dehydrogenase levels, ECOG performance status ≤ 1, and no tumor mass ≥ 7 cm.

High-risk patients were given six cycles of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R (with rituximab on day 1 only) along with CNS prophylaxis or active therapy with intrathecal methotrexate.

In contrast, low-risk patients were given two cycles of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R, with rituximab on days 1 and 5, followed by positron emission tomography.

If that was negative, the patients had one additional treatment cycle and no CNS prophylaxis, but if it was positive, they were given four additional cycles, plus intrathecal methotrexate.

Of the 113 patients enrolled, 79% were male, median age was 49 years, and 62% were aged at least 40 years, including 26% aged at least 60 years.

The team determined that 13% of the patients were of low risk, 87% were high risk, and 11% had cerebrospinal fluid involvement. One-quarter (24.7%) were HIV positive, with a median CD4+ T-cell count of 268 cells/mm3.

The majority (87%) of low-risk patients received three treatment cycles, and 82% of high-risk patents were administered six treatment cycles.

Over a median follow-up of 58.7 months (4.9 years), the 4-year event-free survival (EFS) rate across the whole cohort was 84.5% and overall survival was 87%.

At the time of analysis, all low-risk patients were in remission; among high-risk patients, the 4-year EFS was 82.1% and overall survival was 84.9%.

The team reports that treatment was equally effective across age groups, and irrespective of HIV status and International Prognostic Index risk group.

Only 2% of high-risk patients with no pretreatment evidence of CNS involvement had relapses in the brain parenchyma. Just over half (55%) of patients with cerebrospinal fluid involvement at presentation experienced disease progression or died.

Five patients died of treatment-related toxicity. Grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia occurred during 17% of cycles, and febrile neutropenia was seen during 16%. Tumor lysis syndrome was rare, occurring in 5% of patients.

Next, the researchers are planning on focusing on CNS disease, looking at EPOCH-R as the backbone and adding intrathecal methotrexate and an additional targeted agent with known CNS penetration.

Dr. Roschewski said that is “a very attractive strategy and ... we will initiate enrollment in that study probably in the next couple of months here at the NCI,” he added, noting that it will be an early phase 1 study.

Another issue he identified that “doesn’t get spoken about quite as much but I do think is important is potentially working on supportive care guidelines for how we manage these patients.” Dr. Roschewski explained, “One of the things you see over and over in these Burkitt lymphoma studies is that some patients don’t make it through therapy because they’re so sick at the beginning, and they have certain risks.

“I think simply improving that type of care, independent of what regimen is used, can potentially improve the outcomes across patient groups.”

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, AIDS Malignancy Consortium, and the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and Lymphoid Malignancies Branch. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Your diet may be aging you

Recent studies have shown a correlation between many dietary elements and skin diseases including acne, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis. and there is now evidence that the aging process can also be slowed with a healthy diet. Previous studies have shown that intake of vegetables, fish, and foods high in vitamin C, carotenoids, olive oil, and linoleic acid are associated with decreased wrinkles.

In a Dutch population-based cohort study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 2019, Mekić et al. investigated the association between diet and facial wrinkles in an elderly population. Facial photographs were used to evaluate wrinkle severity and diet of the participants was assessed with the Food Frequency Questionnaire and adherence to the Dutch Healthy Diet Index (DHDI).

The DHDI is a measure of the ability to adhere to the Dutch Guidelines for a Healthy Diet. The guidelines recommend a daily intake in the diet of at least 200 g of vegetables daily; at least 200 g of fruit; 90 g of brown bread, wholemeal bread, or other whole-grain products; and at least 15 g of unsalted nuts. One serving of fish (preferably oily fish) per week and little to no dairy, alcohol, red meat, cooking fats, and sugar is also recommended.

The study revealed that better adherence to the DHDI was significantly associated with fewer wrinkles among women but not men. Women who ate more animal meat and fats and carbohydrates had more wrinkles than did those with a fruit-dominant diet.

Although other healthy behaviors such as exercise and alcohol are likely to play a role in confounding these data, UV exposure as a cause of wrinkling was accounted for, and in the study, increased outdoor exercise was associated with more wrinkles. Unhealthy food can induce oxidative stress, increased skin and gut inflammation, and glycation, which are some of the physiologic mechanisms suggested to increase wrinkle formation. In contrast, nutrients in fruits and vegetables stimulate collagen production and DNA repair and reduce oxidative stress on the skin.

Nutritional advice is largely rare in internal medicine, cardiology, and even endocrinology. We are developing better ways to assess and understand the way foods interact and cause inflammation of the gut and the body and skin. I highly recommend nutritional education be a part of our residency training programs and to make better guidelines on the prevention of skin disease and aging available for both practitioners and patients.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Mekić S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 May;80(5):1358-1363.e2.

Purba MB et al. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20(1):71‐80.

van Lee L et al. Nutr J. 2012 Jul 20;11:49.

Kromhout D et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016 Aug;70(8):869‐78.

Recent studies have shown a correlation between many dietary elements and skin diseases including acne, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis. and there is now evidence that the aging process can also be slowed with a healthy diet. Previous studies have shown that intake of vegetables, fish, and foods high in vitamin C, carotenoids, olive oil, and linoleic acid are associated with decreased wrinkles.

In a Dutch population-based cohort study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 2019, Mekić et al. investigated the association between diet and facial wrinkles in an elderly population. Facial photographs were used to evaluate wrinkle severity and diet of the participants was assessed with the Food Frequency Questionnaire and adherence to the Dutch Healthy Diet Index (DHDI).

The DHDI is a measure of the ability to adhere to the Dutch Guidelines for a Healthy Diet. The guidelines recommend a daily intake in the diet of at least 200 g of vegetables daily; at least 200 g of fruit; 90 g of brown bread, wholemeal bread, or other whole-grain products; and at least 15 g of unsalted nuts. One serving of fish (preferably oily fish) per week and little to no dairy, alcohol, red meat, cooking fats, and sugar is also recommended.

The study revealed that better adherence to the DHDI was significantly associated with fewer wrinkles among women but not men. Women who ate more animal meat and fats and carbohydrates had more wrinkles than did those with a fruit-dominant diet.

Although other healthy behaviors such as exercise and alcohol are likely to play a role in confounding these data, UV exposure as a cause of wrinkling was accounted for, and in the study, increased outdoor exercise was associated with more wrinkles. Unhealthy food can induce oxidative stress, increased skin and gut inflammation, and glycation, which are some of the physiologic mechanisms suggested to increase wrinkle formation. In contrast, nutrients in fruits and vegetables stimulate collagen production and DNA repair and reduce oxidative stress on the skin.

Nutritional advice is largely rare in internal medicine, cardiology, and even endocrinology. We are developing better ways to assess and understand the way foods interact and cause inflammation of the gut and the body and skin. I highly recommend nutritional education be a part of our residency training programs and to make better guidelines on the prevention of skin disease and aging available for both practitioners and patients.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Mekić S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 May;80(5):1358-1363.e2.

Purba MB et al. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20(1):71‐80.

van Lee L et al. Nutr J. 2012 Jul 20;11:49.

Kromhout D et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016 Aug;70(8):869‐78.

Recent studies have shown a correlation between many dietary elements and skin diseases including acne, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis. and there is now evidence that the aging process can also be slowed with a healthy diet. Previous studies have shown that intake of vegetables, fish, and foods high in vitamin C, carotenoids, olive oil, and linoleic acid are associated with decreased wrinkles.

In a Dutch population-based cohort study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 2019, Mekić et al. investigated the association between diet and facial wrinkles in an elderly population. Facial photographs were used to evaluate wrinkle severity and diet of the participants was assessed with the Food Frequency Questionnaire and adherence to the Dutch Healthy Diet Index (DHDI).

The DHDI is a measure of the ability to adhere to the Dutch Guidelines for a Healthy Diet. The guidelines recommend a daily intake in the diet of at least 200 g of vegetables daily; at least 200 g of fruit; 90 g of brown bread, wholemeal bread, or other whole-grain products; and at least 15 g of unsalted nuts. One serving of fish (preferably oily fish) per week and little to no dairy, alcohol, red meat, cooking fats, and sugar is also recommended.

The study revealed that better adherence to the DHDI was significantly associated with fewer wrinkles among women but not men. Women who ate more animal meat and fats and carbohydrates had more wrinkles than did those with a fruit-dominant diet.

Although other healthy behaviors such as exercise and alcohol are likely to play a role in confounding these data, UV exposure as a cause of wrinkling was accounted for, and in the study, increased outdoor exercise was associated with more wrinkles. Unhealthy food can induce oxidative stress, increased skin and gut inflammation, and glycation, which are some of the physiologic mechanisms suggested to increase wrinkle formation. In contrast, nutrients in fruits and vegetables stimulate collagen production and DNA repair and reduce oxidative stress on the skin.

Nutritional advice is largely rare in internal medicine, cardiology, and even endocrinology. We are developing better ways to assess and understand the way foods interact and cause inflammation of the gut and the body and skin. I highly recommend nutritional education be a part of our residency training programs and to make better guidelines on the prevention of skin disease and aging available for both practitioners and patients.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Mekić S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 May;80(5):1358-1363.e2.

Purba MB et al. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20(1):71‐80.

van Lee L et al. Nutr J. 2012 Jul 20;11:49.

Kromhout D et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016 Aug;70(8):869‐78.

Dermatology News welcomes new advisory board member

at University Hospital Saint-Louis in Paris, in the inflammatory diseases outpatient clinic, where he treats patients with severe psoriasis and other inflammatory chronic skin diseases.

He is a member of several dermatology specialty organizations, including the Société Française de Dermatologie, the European Academy of Dermatology, as well as the American Academy of Dermatology. His research interests are in immunology and inflammatory diseases; he also has a passion for art and history.

at University Hospital Saint-Louis in Paris, in the inflammatory diseases outpatient clinic, where he treats patients with severe psoriasis and other inflammatory chronic skin diseases.

He is a member of several dermatology specialty organizations, including the Société Française de Dermatologie, the European Academy of Dermatology, as well as the American Academy of Dermatology. His research interests are in immunology and inflammatory diseases; he also has a passion for art and history.

at University Hospital Saint-Louis in Paris, in the inflammatory diseases outpatient clinic, where he treats patients with severe psoriasis and other inflammatory chronic skin diseases.

He is a member of several dermatology specialty organizations, including the Société Française de Dermatologie, the European Academy of Dermatology, as well as the American Academy of Dermatology. His research interests are in immunology and inflammatory diseases; he also has a passion for art and history.

Frequent hypoglycemic episodes raise cardiac event risk

Frequent hypoglycemic episodes were linked to a raised incidence of cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes in a recent retrospective study, suggesting certain hypoglycemia-associated diabetes drugs should be avoided, an investigator said.

Patients who had more than five hypoglycemic episodes per year had a 61% greater risk of cardiovascular (CV) events, compared with patients with less frequent episodes, according to results of the study.

Although there were fewer strokes among younger patients, the overall increase in cardiovascular event risk held up regardless of age group, according to investigator Aman Rajpal, MD, of Louis Stokes Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Case Western Reserve University, both in Cleveland.

On the basis of these and earlier studies tying hypoglycemia to CV risk, health care providers need to “pay close attention” to low blood sugar and personalize glycemic control targets for each patient based on risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Rajpal said in a presentation of the study at the virtual annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Also, this suggests that avoidance of drugs associated with increased risk of hypoglycemia – namely insulin, sulfonylureas, or others – is essential to avoid and minimize the risk of cardiovascular events in this patient population with type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Rajpal. “Let us remember part of our Hippocratic oath: ‘Above all, do no harm.’ ”

Tailoring treatment to mitigate risk

Mark Schutta, MD, medical director of Penn Rodebaugh Diabetes Center in Philadelphia, said that results of this study suggest a need to carefully select medical therapy for each individual patient with diabetes in order to mitigate CV risk.

“It’s really about tailoring their drugs to their personal situation,” Dr. Schutta said in an interview.

Although newer diabetes drug classes are associated with low to no risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Schutta said that there is still a place for drugs such as sulfonylureas in certain situations.

Among sulfonylureas, glyburide comes with a much higher incidence of hypoglycemia, compared with glipizide and glimepiride, according to Dr. Schutta. “I think there’s a role for both drugs, but you have to be very careful, and you have to get the data from your patients.”

Hypoglycemia frequency and outcomes

Speculation that hypoglycemia could be linked to adverse CV outcomes was sparked years ago by trials such as ADVANCE. Severe hypoglycemia in that study was associated with a 168% increased risk of death from a CV cause (N Engl J Med. 2010 Oct 7;363:1410-8).

At the time, ADVANCE investigators said they were unable to find evidence that multiple severe hypoglycemia episodes conferred a greater risk of CV events versus a single hypoglycemia episode, though they added that few patients had recurrent events.

“In other words, the association between the number of hypoglycemia events, and adverse CV outcomes is still unclear,” said Dr. Rajpal in his virtual ADA presentation.

Potential elevated risks with more than five episodes

To evaluate the association between frequent hypoglycemic episodes (i.e., more than five per year, compared with one to five episodes) and CV events, Dr. Rajpal and colleagues evaluated outcomes data for 4.9 million adults with type 2 diabetes found in a large commercial database including information on patients in 27 U.S. health care networks.

Database records indicated that about 182,000 patients, or nearly 4%, had episodes of hyperglycemia, which Dr. Rajpal said was presumed to mean a plasma glucose level of less than 70 mg/dL.

Characteristics of the patients with more than five hypoglycemic episodes were similar to those with one to five episodes, although they were more likely to be 65 years or older, and were “slightly more likely” to be on insulin, which could possibly precipitate more hypoglycemic episodes in that group, Dr. Rajpal said.

Key findings

In the main analysis, Dr. Rajpal said, risk of CV events was significantly increased in those with more than five hypoglycemic episodes, compared with those with one to five episodes, with an odds ratio of 1.61 (95% confidence interval, 1.56-1.66). The incidence of cardiovascular events was 33.1% in those with more than five episodes and 23.5% in those with one to five episodes, according to the data presented.

Risks were also significantly increased specifically for cardiac arrhythmias, cerebrovascular accidents, and MI, Dr. Rajpal said, with ORs of 1.65 (95% CI, 1.9-1.71), 1.38 (95% CI, 1.22-1.56), and 1.43 (95% CI, 1.36-1.50), respectively.

Because individuals in the group with more than five hypoglycemic episodes were more likely to be elderly, Dr. Rajpal said that he and coinvestigators decided to perform an age-specific stratified analysis.

Although cerebral vascular incidence was low in younger patients, risk of CV events overall was nevertheless significantly elevated for those aged 65 years or older, 45-64 years, and 18-44 years, with ORs of 1.69 (95% CI, 1.61-1.7), 1.58 (95% CI, 1.48-1.69), and 1.62 (95% CI, 1.33-1.97).

“The results were still valid in stratified analysis based on different age groups,” Dr. Rajpal said.

Dr. Rajpal and coauthors reported that he had no conflicts of interest related to the research.

SOURCE: Rajpal A et al. ADA 2020, Abstract 161-OR.

Frequent hypoglycemic episodes were linked to a raised incidence of cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes in a recent retrospective study, suggesting certain hypoglycemia-associated diabetes drugs should be avoided, an investigator said.

Patients who had more than five hypoglycemic episodes per year had a 61% greater risk of cardiovascular (CV) events, compared with patients with less frequent episodes, according to results of the study.

Although there were fewer strokes among younger patients, the overall increase in cardiovascular event risk held up regardless of age group, according to investigator Aman Rajpal, MD, of Louis Stokes Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Case Western Reserve University, both in Cleveland.

On the basis of these and earlier studies tying hypoglycemia to CV risk, health care providers need to “pay close attention” to low blood sugar and personalize glycemic control targets for each patient based on risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Rajpal said in a presentation of the study at the virtual annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Also, this suggests that avoidance of drugs associated with increased risk of hypoglycemia – namely insulin, sulfonylureas, or others – is essential to avoid and minimize the risk of cardiovascular events in this patient population with type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Rajpal. “Let us remember part of our Hippocratic oath: ‘Above all, do no harm.’ ”

Tailoring treatment to mitigate risk

Mark Schutta, MD, medical director of Penn Rodebaugh Diabetes Center in Philadelphia, said that results of this study suggest a need to carefully select medical therapy for each individual patient with diabetes in order to mitigate CV risk.

“It’s really about tailoring their drugs to their personal situation,” Dr. Schutta said in an interview.

Although newer diabetes drug classes are associated with low to no risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Schutta said that there is still a place for drugs such as sulfonylureas in certain situations.

Among sulfonylureas, glyburide comes with a much higher incidence of hypoglycemia, compared with glipizide and glimepiride, according to Dr. Schutta. “I think there’s a role for both drugs, but you have to be very careful, and you have to get the data from your patients.”

Hypoglycemia frequency and outcomes

Speculation that hypoglycemia could be linked to adverse CV outcomes was sparked years ago by trials such as ADVANCE. Severe hypoglycemia in that study was associated with a 168% increased risk of death from a CV cause (N Engl J Med. 2010 Oct 7;363:1410-8).

At the time, ADVANCE investigators said they were unable to find evidence that multiple severe hypoglycemia episodes conferred a greater risk of CV events versus a single hypoglycemia episode, though they added that few patients had recurrent events.

“In other words, the association between the number of hypoglycemia events, and adverse CV outcomes is still unclear,” said Dr. Rajpal in his virtual ADA presentation.

Potential elevated risks with more than five episodes

To evaluate the association between frequent hypoglycemic episodes (i.e., more than five per year, compared with one to five episodes) and CV events, Dr. Rajpal and colleagues evaluated outcomes data for 4.9 million adults with type 2 diabetes found in a large commercial database including information on patients in 27 U.S. health care networks.

Database records indicated that about 182,000 patients, or nearly 4%, had episodes of hyperglycemia, which Dr. Rajpal said was presumed to mean a plasma glucose level of less than 70 mg/dL.

Characteristics of the patients with more than five hypoglycemic episodes were similar to those with one to five episodes, although they were more likely to be 65 years or older, and were “slightly more likely” to be on insulin, which could possibly precipitate more hypoglycemic episodes in that group, Dr. Rajpal said.

Key findings

In the main analysis, Dr. Rajpal said, risk of CV events was significantly increased in those with more than five hypoglycemic episodes, compared with those with one to five episodes, with an odds ratio of 1.61 (95% confidence interval, 1.56-1.66). The incidence of cardiovascular events was 33.1% in those with more than five episodes and 23.5% in those with one to five episodes, according to the data presented.

Risks were also significantly increased specifically for cardiac arrhythmias, cerebrovascular accidents, and MI, Dr. Rajpal said, with ORs of 1.65 (95% CI, 1.9-1.71), 1.38 (95% CI, 1.22-1.56), and 1.43 (95% CI, 1.36-1.50), respectively.

Because individuals in the group with more than five hypoglycemic episodes were more likely to be elderly, Dr. Rajpal said that he and coinvestigators decided to perform an age-specific stratified analysis.

Although cerebral vascular incidence was low in younger patients, risk of CV events overall was nevertheless significantly elevated for those aged 65 years or older, 45-64 years, and 18-44 years, with ORs of 1.69 (95% CI, 1.61-1.7), 1.58 (95% CI, 1.48-1.69), and 1.62 (95% CI, 1.33-1.97).

“The results were still valid in stratified analysis based on different age groups,” Dr. Rajpal said.

Dr. Rajpal and coauthors reported that he had no conflicts of interest related to the research.

SOURCE: Rajpal A et al. ADA 2020, Abstract 161-OR.

Frequent hypoglycemic episodes were linked to a raised incidence of cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes in a recent retrospective study, suggesting certain hypoglycemia-associated diabetes drugs should be avoided, an investigator said.

Patients who had more than five hypoglycemic episodes per year had a 61% greater risk of cardiovascular (CV) events, compared with patients with less frequent episodes, according to results of the study.

Although there were fewer strokes among younger patients, the overall increase in cardiovascular event risk held up regardless of age group, according to investigator Aman Rajpal, MD, of Louis Stokes Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Case Western Reserve University, both in Cleveland.

On the basis of these and earlier studies tying hypoglycemia to CV risk, health care providers need to “pay close attention” to low blood sugar and personalize glycemic control targets for each patient based on risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Rajpal said in a presentation of the study at the virtual annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Also, this suggests that avoidance of drugs associated with increased risk of hypoglycemia – namely insulin, sulfonylureas, or others – is essential to avoid and minimize the risk of cardiovascular events in this patient population with type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Rajpal. “Let us remember part of our Hippocratic oath: ‘Above all, do no harm.’ ”

Tailoring treatment to mitigate risk

Mark Schutta, MD, medical director of Penn Rodebaugh Diabetes Center in Philadelphia, said that results of this study suggest a need to carefully select medical therapy for each individual patient with diabetes in order to mitigate CV risk.

“It’s really about tailoring their drugs to their personal situation,” Dr. Schutta said in an interview.

Although newer diabetes drug classes are associated with low to no risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Schutta said that there is still a place for drugs such as sulfonylureas in certain situations.

Among sulfonylureas, glyburide comes with a much higher incidence of hypoglycemia, compared with glipizide and glimepiride, according to Dr. Schutta. “I think there’s a role for both drugs, but you have to be very careful, and you have to get the data from your patients.”

Hypoglycemia frequency and outcomes

Speculation that hypoglycemia could be linked to adverse CV outcomes was sparked years ago by trials such as ADVANCE. Severe hypoglycemia in that study was associated with a 168% increased risk of death from a CV cause (N Engl J Med. 2010 Oct 7;363:1410-8).

At the time, ADVANCE investigators said they were unable to find evidence that multiple severe hypoglycemia episodes conferred a greater risk of CV events versus a single hypoglycemia episode, though they added that few patients had recurrent events.

“In other words, the association between the number of hypoglycemia events, and adverse CV outcomes is still unclear,” said Dr. Rajpal in his virtual ADA presentation.

Potential elevated risks with more than five episodes

To evaluate the association between frequent hypoglycemic episodes (i.e., more than five per year, compared with one to five episodes) and CV events, Dr. Rajpal and colleagues evaluated outcomes data for 4.9 million adults with type 2 diabetes found in a large commercial database including information on patients in 27 U.S. health care networks.

Database records indicated that about 182,000 patients, or nearly 4%, had episodes of hyperglycemia, which Dr. Rajpal said was presumed to mean a plasma glucose level of less than 70 mg/dL.

Characteristics of the patients with more than five hypoglycemic episodes were similar to those with one to five episodes, although they were more likely to be 65 years or older, and were “slightly more likely” to be on insulin, which could possibly precipitate more hypoglycemic episodes in that group, Dr. Rajpal said.

Key findings

In the main analysis, Dr. Rajpal said, risk of CV events was significantly increased in those with more than five hypoglycemic episodes, compared with those with one to five episodes, with an odds ratio of 1.61 (95% confidence interval, 1.56-1.66). The incidence of cardiovascular events was 33.1% in those with more than five episodes and 23.5% in those with one to five episodes, according to the data presented.

Risks were also significantly increased specifically for cardiac arrhythmias, cerebrovascular accidents, and MI, Dr. Rajpal said, with ORs of 1.65 (95% CI, 1.9-1.71), 1.38 (95% CI, 1.22-1.56), and 1.43 (95% CI, 1.36-1.50), respectively.

Because individuals in the group with more than five hypoglycemic episodes were more likely to be elderly, Dr. Rajpal said that he and coinvestigators decided to perform an age-specific stratified analysis.

Although cerebral vascular incidence was low in younger patients, risk of CV events overall was nevertheless significantly elevated for those aged 65 years or older, 45-64 years, and 18-44 years, with ORs of 1.69 (95% CI, 1.61-1.7), 1.58 (95% CI, 1.48-1.69), and 1.62 (95% CI, 1.33-1.97).

“The results were still valid in stratified analysis based on different age groups,” Dr. Rajpal said.

Dr. Rajpal and coauthors reported that he had no conflicts of interest related to the research.

SOURCE: Rajpal A et al. ADA 2020, Abstract 161-OR.

FROM ADA 2020

Choosing a career in health equity and health care policy

Dr. Anyane-Yeboa is a Commonwealth Fund Fellow in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University and a recent graduate of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She previously completed her gastroenterology fellowship at the University of Chicago. She will be an academic gastroenterologist at Massachusetts General Hospital starting in the fall of 2020.

How did your career pathway lead you to a career in health equity and policy?

I have been passionate about issues related to health equity, workforce diversity, and care of vulnerable populations since the early years of my career. For instance, as undergraduates my friends and I received a grant to start a program to provide mentorship for endangered youth in Boston. During my residency and chief residency, I advocated for increased resident diversity and created programs for underrepresented minority medical students to increase minority representation in medicine. During my gastroenterology fellowship, I remained passionate about the care of minority and underserved populations. During my second year of fellowship, I looked for advanced training opportunities where I could learn the skills to tackle health disparities in minority communities, and almost serendipitously came across the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy. When I decided to apply for the fellowship, I knew that this would be a nontraditional path for most gastroenterology fellows, but the right path for me.

About the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship

The purpose of the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University is to train the next generation of leaders in health care. The program is based at Harvard Medical School and supported by the Commonwealth Fund whose mission is to “provide affordable quality health care for all.” To date, the fellowship has trained more than 130 physicians who are advancing health care across the nation as leaders in public health, academic medicine, and health policy.

The fellowship is a year-long, full-time, degree-granting program. Fellows are eligible for a master’s in public health with a concentration in health management or health policy from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health or a master’s in public administration from the Harvard Kennedy School.

The fellowship program and experiences have been transformative for me. The structure of the program consists of visits to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Boston Public Health Commission, and the Commonwealth Fund, as well as lectures, seminars, and journal club sessions with national leaders in public health, health policy, and health care delivery reform. Additional opportunities include one-on-one shadowing experiences with leaders in hospital administration at academic institutions in Boston and private meetings with leaders and staff at several government agencies in Washington, including the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services, the Office of Minority Health, the Food and Drug Administration, the Health Resources & Services Administration, and the National Institutes of Health.

The program has given me an opportunity to meet and learn from physicians who have chosen a variety of different career paths. Through the program I have had exposure to physicians in academic medicine, health care administration, health policy, and public service as well as those who have chosen a combination of clinical practice with any of the above. This experience has opened my eyes to the different possibilities for physician careers and has encouraged me to be open if new opportunities should arise.

As part of the fellowship, we also have regular meetings with Joan Reede, MD, MPH, who is the director of the fellowship and has been with the program since its inception; she is also the Dean of Diversity and Inclusion at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Reede is an incredibly wise, insightful, and caring mentor, but also a powerhouse in issues surrounding workforce diversity, mentorship, policy, care of underserved communities, and being an advocate for change. To have access to such a powerful individual who has dedicated her career to the mentorship of individuals like myself, who cares deeply about the impact of our careers, and who genuinely values each fellow almost as her own child is a unique gift that is hard to describe in words.

The Commonwealth Fund Fellowship also provides a large network of mentors and advisers. My direct mentor for the program is Monica Bharel, MD, MPH, who is a former Commonwealth Fund fellow and the current Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. However, I also have a wealth of other mentors and advisers in the alumni fellows, including Darrell Gray II, MD, MPH, a former fellow and gastroenterologist at the Ohio State University College of Medicine, as well as the other faculty associated with the program. I never imagined that I would have access to leaders in so many different sectors of health care and policy who are genuinely and passionately rooting for my success. In addition, my cofellows and I have created a uniquely special bond, and they will likely continue as my close network of peer advisers as I move forward throughout my career.

After the fellowship

I have no doubt that the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship will alter the trajectory of my career. It has already affected my career path in ways that I could not have anticipated years ago. The knowledge that I have gained in health care policy, innovation, and equity, as well as the networks that I have access to as a fellow, will be invaluable as I move forward. In terms of next steps, I will be working as an academic gastroenterologist; I will continue to lead initiatives, perform research, and participate in projects to elevate the voices of underserved communities and work toward health equity in gastroenterology. I am particularly passionate about ending disparities in colorectal cancer in minority communities and increasing awareness around minorities with inflammatory bowel disease.

I plan to work with health centers, city- and state-level organizations, and community partners to raise awareness around issues of equity in gastroenterology and develop interventions to create change. I will also work with local legislators and community-based organizations to advocate for policies that remove barriers to screening both locally and nationally. Further down the line, I am open to exploring careers in the public sector or health care administration if that is where my career takes me. The exposure that I had to these fields as part of the fellowship has shown me that it is possible to be a practicing gastroenterologist and simultaneously work in the public sector, health policy, or health care administration. If you are interested in applying to the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University, please feel free to contact me at adjoa.anyaneyeboa@gmail.com. More information about the program and how to apply can be found at https://cff.hms.harvard.edu/.

Dr. Anyane-Yeboa is a Commonwealth Fund Fellow in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University and a recent graduate of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She previously completed her gastroenterology fellowship at the University of Chicago. She will be an academic gastroenterologist at Massachusetts General Hospital starting in the fall of 2020.

How did your career pathway lead you to a career in health equity and policy?

I have been passionate about issues related to health equity, workforce diversity, and care of vulnerable populations since the early years of my career. For instance, as undergraduates my friends and I received a grant to start a program to provide mentorship for endangered youth in Boston. During my residency and chief residency, I advocated for increased resident diversity and created programs for underrepresented minority medical students to increase minority representation in medicine. During my gastroenterology fellowship, I remained passionate about the care of minority and underserved populations. During my second year of fellowship, I looked for advanced training opportunities where I could learn the skills to tackle health disparities in minority communities, and almost serendipitously came across the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy. When I decided to apply for the fellowship, I knew that this would be a nontraditional path for most gastroenterology fellows, but the right path for me.

About the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship

The purpose of the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University is to train the next generation of leaders in health care. The program is based at Harvard Medical School and supported by the Commonwealth Fund whose mission is to “provide affordable quality health care for all.” To date, the fellowship has trained more than 130 physicians who are advancing health care across the nation as leaders in public health, academic medicine, and health policy.

The fellowship is a year-long, full-time, degree-granting program. Fellows are eligible for a master’s in public health with a concentration in health management or health policy from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health or a master’s in public administration from the Harvard Kennedy School.

The fellowship program and experiences have been transformative for me. The structure of the program consists of visits to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Boston Public Health Commission, and the Commonwealth Fund, as well as lectures, seminars, and journal club sessions with national leaders in public health, health policy, and health care delivery reform. Additional opportunities include one-on-one shadowing experiences with leaders in hospital administration at academic institutions in Boston and private meetings with leaders and staff at several government agencies in Washington, including the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services, the Office of Minority Health, the Food and Drug Administration, the Health Resources & Services Administration, and the National Institutes of Health.

The program has given me an opportunity to meet and learn from physicians who have chosen a variety of different career paths. Through the program I have had exposure to physicians in academic medicine, health care administration, health policy, and public service as well as those who have chosen a combination of clinical practice with any of the above. This experience has opened my eyes to the different possibilities for physician careers and has encouraged me to be open if new opportunities should arise.

As part of the fellowship, we also have regular meetings with Joan Reede, MD, MPH, who is the director of the fellowship and has been with the program since its inception; she is also the Dean of Diversity and Inclusion at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Reede is an incredibly wise, insightful, and caring mentor, but also a powerhouse in issues surrounding workforce diversity, mentorship, policy, care of underserved communities, and being an advocate for change. To have access to such a powerful individual who has dedicated her career to the mentorship of individuals like myself, who cares deeply about the impact of our careers, and who genuinely values each fellow almost as her own child is a unique gift that is hard to describe in words.

The Commonwealth Fund Fellowship also provides a large network of mentors and advisers. My direct mentor for the program is Monica Bharel, MD, MPH, who is a former Commonwealth Fund fellow and the current Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. However, I also have a wealth of other mentors and advisers in the alumni fellows, including Darrell Gray II, MD, MPH, a former fellow and gastroenterologist at the Ohio State University College of Medicine, as well as the other faculty associated with the program. I never imagined that I would have access to leaders in so many different sectors of health care and policy who are genuinely and passionately rooting for my success. In addition, my cofellows and I have created a uniquely special bond, and they will likely continue as my close network of peer advisers as I move forward throughout my career.

After the fellowship

I have no doubt that the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship will alter the trajectory of my career. It has already affected my career path in ways that I could not have anticipated years ago. The knowledge that I have gained in health care policy, innovation, and equity, as well as the networks that I have access to as a fellow, will be invaluable as I move forward. In terms of next steps, I will be working as an academic gastroenterologist; I will continue to lead initiatives, perform research, and participate in projects to elevate the voices of underserved communities and work toward health equity in gastroenterology. I am particularly passionate about ending disparities in colorectal cancer in minority communities and increasing awareness around minorities with inflammatory bowel disease.

I plan to work with health centers, city- and state-level organizations, and community partners to raise awareness around issues of equity in gastroenterology and develop interventions to create change. I will also work with local legislators and community-based organizations to advocate for policies that remove barriers to screening both locally and nationally. Further down the line, I am open to exploring careers in the public sector or health care administration if that is where my career takes me. The exposure that I had to these fields as part of the fellowship has shown me that it is possible to be a practicing gastroenterologist and simultaneously work in the public sector, health policy, or health care administration. If you are interested in applying to the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University, please feel free to contact me at adjoa.anyaneyeboa@gmail.com. More information about the program and how to apply can be found at https://cff.hms.harvard.edu/.

Dr. Anyane-Yeboa is a Commonwealth Fund Fellow in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University and a recent graduate of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She previously completed her gastroenterology fellowship at the University of Chicago. She will be an academic gastroenterologist at Massachusetts General Hospital starting in the fall of 2020.

How did your career pathway lead you to a career in health equity and policy?

I have been passionate about issues related to health equity, workforce diversity, and care of vulnerable populations since the early years of my career. For instance, as undergraduates my friends and I received a grant to start a program to provide mentorship for endangered youth in Boston. During my residency and chief residency, I advocated for increased resident diversity and created programs for underrepresented minority medical students to increase minority representation in medicine. During my gastroenterology fellowship, I remained passionate about the care of minority and underserved populations. During my second year of fellowship, I looked for advanced training opportunities where I could learn the skills to tackle health disparities in minority communities, and almost serendipitously came across the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy. When I decided to apply for the fellowship, I knew that this would be a nontraditional path for most gastroenterology fellows, but the right path for me.

About the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship

The purpose of the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University is to train the next generation of leaders in health care. The program is based at Harvard Medical School and supported by the Commonwealth Fund whose mission is to “provide affordable quality health care for all.” To date, the fellowship has trained more than 130 physicians who are advancing health care across the nation as leaders in public health, academic medicine, and health policy.

The fellowship is a year-long, full-time, degree-granting program. Fellows are eligible for a master’s in public health with a concentration in health management or health policy from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health or a master’s in public administration from the Harvard Kennedy School.

The fellowship program and experiences have been transformative for me. The structure of the program consists of visits to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Boston Public Health Commission, and the Commonwealth Fund, as well as lectures, seminars, and journal club sessions with national leaders in public health, health policy, and health care delivery reform. Additional opportunities include one-on-one shadowing experiences with leaders in hospital administration at academic institutions in Boston and private meetings with leaders and staff at several government agencies in Washington, including the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services, the Office of Minority Health, the Food and Drug Administration, the Health Resources & Services Administration, and the National Institutes of Health.

The program has given me an opportunity to meet and learn from physicians who have chosen a variety of different career paths. Through the program I have had exposure to physicians in academic medicine, health care administration, health policy, and public service as well as those who have chosen a combination of clinical practice with any of the above. This experience has opened my eyes to the different possibilities for physician careers and has encouraged me to be open if new opportunities should arise.

As part of the fellowship, we also have regular meetings with Joan Reede, MD, MPH, who is the director of the fellowship and has been with the program since its inception; she is also the Dean of Diversity and Inclusion at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Reede is an incredibly wise, insightful, and caring mentor, but also a powerhouse in issues surrounding workforce diversity, mentorship, policy, care of underserved communities, and being an advocate for change. To have access to such a powerful individual who has dedicated her career to the mentorship of individuals like myself, who cares deeply about the impact of our careers, and who genuinely values each fellow almost as her own child is a unique gift that is hard to describe in words.

The Commonwealth Fund Fellowship also provides a large network of mentors and advisers. My direct mentor for the program is Monica Bharel, MD, MPH, who is a former Commonwealth Fund fellow and the current Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. However, I also have a wealth of other mentors and advisers in the alumni fellows, including Darrell Gray II, MD, MPH, a former fellow and gastroenterologist at the Ohio State University College of Medicine, as well as the other faculty associated with the program. I never imagined that I would have access to leaders in so many different sectors of health care and policy who are genuinely and passionately rooting for my success. In addition, my cofellows and I have created a uniquely special bond, and they will likely continue as my close network of peer advisers as I move forward throughout my career.

After the fellowship

I have no doubt that the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship will alter the trajectory of my career. It has already affected my career path in ways that I could not have anticipated years ago. The knowledge that I have gained in health care policy, innovation, and equity, as well as the networks that I have access to as a fellow, will be invaluable as I move forward. In terms of next steps, I will be working as an academic gastroenterologist; I will continue to lead initiatives, perform research, and participate in projects to elevate the voices of underserved communities and work toward health equity in gastroenterology. I am particularly passionate about ending disparities in colorectal cancer in minority communities and increasing awareness around minorities with inflammatory bowel disease.

I plan to work with health centers, city- and state-level organizations, and community partners to raise awareness around issues of equity in gastroenterology and develop interventions to create change. I will also work with local legislators and community-based organizations to advocate for policies that remove barriers to screening both locally and nationally. Further down the line, I am open to exploring careers in the public sector or health care administration if that is where my career takes me. The exposure that I had to these fields as part of the fellowship has shown me that it is possible to be a practicing gastroenterologist and simultaneously work in the public sector, health policy, or health care administration. If you are interested in applying to the Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University, please feel free to contact me at adjoa.anyaneyeboa@gmail.com. More information about the program and how to apply can be found at https://cff.hms.harvard.edu/.

Vulvar melanoma is increasing in older women

Maia K. Erickson reported in a poster at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

These are often aggressive malignancies. The 5-year survival following diagnosis of vulvar melanoma in women aged 60 years or older was 39.7%, compared with 61.9% in younger women, according to Ms. Erickson, a visiting research fellow in the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

She presented a population-based study of epidemiologic trends in vulvar melanoma based upon analysis of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database. Vulvar melanoma was rare during the study years 2000-2016, with an overall incidence rate of 0.1 cases per 100,000 women. That worked out to 746 analyzable cases. Of note, the incidence rate ratio was 680% higher in older women (age 60 and older).

One reason for the markedly worse 5-year survival in older women was that the predominant histologic subtype of vulvar melanoma in that population was nodular melanoma, accounting for 48% of the cases where a histologic subtype was specified. In contrast, the less-aggressive superficial spreading melanoma subtype prevailed in patients aged under 60 years, accounting for 63% of cases.

About 93% of vulvar melanomas occurred in whites; 63% were local and 8.7% were metastatic.

Ms. Erickson noted that the vulva is the most common site for gynecologic tract melanomas, accounting for 70% of them. And while the female genitalia make up only 1%-2% of body surface area, that’s the anatomic site of up to 7% of all melanomas in women.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

Maia K. Erickson reported in a poster at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

These are often aggressive malignancies. The 5-year survival following diagnosis of vulvar melanoma in women aged 60 years or older was 39.7%, compared with 61.9% in younger women, according to Ms. Erickson, a visiting research fellow in the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

She presented a population-based study of epidemiologic trends in vulvar melanoma based upon analysis of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database. Vulvar melanoma was rare during the study years 2000-2016, with an overall incidence rate of 0.1 cases per 100,000 women. That worked out to 746 analyzable cases. Of note, the incidence rate ratio was 680% higher in older women (age 60 and older).

One reason for the markedly worse 5-year survival in older women was that the predominant histologic subtype of vulvar melanoma in that population was nodular melanoma, accounting for 48% of the cases where a histologic subtype was specified. In contrast, the less-aggressive superficial spreading melanoma subtype prevailed in patients aged under 60 years, accounting for 63% of cases.

About 93% of vulvar melanomas occurred in whites; 63% were local and 8.7% were metastatic.

Ms. Erickson noted that the vulva is the most common site for gynecologic tract melanomas, accounting for 70% of them. And while the female genitalia make up only 1%-2% of body surface area, that’s the anatomic site of up to 7% of all melanomas in women.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

Maia K. Erickson reported in a poster at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

These are often aggressive malignancies. The 5-year survival following diagnosis of vulvar melanoma in women aged 60 years or older was 39.7%, compared with 61.9% in younger women, according to Ms. Erickson, a visiting research fellow in the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

She presented a population-based study of epidemiologic trends in vulvar melanoma based upon analysis of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database. Vulvar melanoma was rare during the study years 2000-2016, with an overall incidence rate of 0.1 cases per 100,000 women. That worked out to 746 analyzable cases. Of note, the incidence rate ratio was 680% higher in older women (age 60 and older).

One reason for the markedly worse 5-year survival in older women was that the predominant histologic subtype of vulvar melanoma in that population was nodular melanoma, accounting for 48% of the cases where a histologic subtype was specified. In contrast, the less-aggressive superficial spreading melanoma subtype prevailed in patients aged under 60 years, accounting for 63% of cases.

About 93% of vulvar melanomas occurred in whites; 63% were local and 8.7% were metastatic.

Ms. Erickson noted that the vulva is the most common site for gynecologic tract melanomas, accounting for 70% of them. And while the female genitalia make up only 1%-2% of body surface area, that’s the anatomic site of up to 7% of all melanomas in women.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

FROM AAD 2020

FDA approves Cosentyx for treatment of active nr-axSpA

The Food and Drug Administration has approved secukinumab (Cosentyx) for the treatment of active nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA), according to an announcement from the drug’s manufacturer, Novartis.

FDA approval was based on results of the 2-year PREVENT trial, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study in 555 adults with active nr-axSpA who received a loading dose of 150 mg secukinumab subcutaneously weekly for 4 weeks, then maintenance dosing with 150 mg secukinumab monthly; 150 mg secukinumab monthly with no loading dose; or placebo. Patients were included if they were aged at least 18 years with 6 months or more of inflammatory back pain, had objective signs of inflammation (sacroiliitis on MRI and/or C-reactive protein at 5.0 mg/dL or higher), had active disease and spinal pain according to the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, had total back pain with a visual analog scale of 40 mm or greater, and had not received a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor or had an inadequate response to no more than one TNF inhibitor. A total of 501 patients had not previously taken a biologic medication.

A significantly greater proportion of biologic-naive patients taking secukinumab in both active treatment arm met the trial’s primary endpoint of at least a 40% improvement in the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society response criteria versus placebo after 52 weeks. Both loading and nonloading arms saw significant improvements in Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life scores, compared with those in the placebo group.

The safety profile of secukinumab in PREVENT was shown to be consistent with previous clinical trials, with no new safety signals detected.

Secukinumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody that directly inhibits interleukin-17A, also received European Medicines Agency approval for the treatment of nr-axSpA in April 2020. It is already approved by the FDA for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved secukinumab (Cosentyx) for the treatment of active nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA), according to an announcement from the drug’s manufacturer, Novartis.

FDA approval was based on results of the 2-year PREVENT trial, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study in 555 adults with active nr-axSpA who received a loading dose of 150 mg secukinumab subcutaneously weekly for 4 weeks, then maintenance dosing with 150 mg secukinumab monthly; 150 mg secukinumab monthly with no loading dose; or placebo. Patients were included if they were aged at least 18 years with 6 months or more of inflammatory back pain, had objective signs of inflammation (sacroiliitis on MRI and/or C-reactive protein at 5.0 mg/dL or higher), had active disease and spinal pain according to the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, had total back pain with a visual analog scale of 40 mm or greater, and had not received a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor or had an inadequate response to no more than one TNF inhibitor. A total of 501 patients had not previously taken a biologic medication.

A significantly greater proportion of biologic-naive patients taking secukinumab in both active treatment arm met the trial’s primary endpoint of at least a 40% improvement in the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society response criteria versus placebo after 52 weeks. Both loading and nonloading arms saw significant improvements in Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life scores, compared with those in the placebo group.

The safety profile of secukinumab in PREVENT was shown to be consistent with previous clinical trials, with no new safety signals detected.