User login

COVID-19 death rate was twice as high in cancer patients in NYC study

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

FROM CANCER DISCOVERY

Sensitizer prevalent in many hypoallergenic products for children

(AD) and allergic contact dermatitis, according to a research letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

In the letter, the authors, Reid W. Collis, of Washington University in St. Louis, and David M. Sheinbein, MD, of the division of dermatology at the university, referred to a previous study showing an association between contact sensitivity with CAPB and people with a history of AD. This was supported by the results of their own recent study in pediatric patients, they wrote, which found that reactions to CAPB were “exclusively” in patients with AD.

In the survey, they looked at children’s shampoo and soap products available on online databases of six of the biggest retailers, and analyzed the top 20 best-selling products for each retailer in 2018. Of the unique products, CAPB was found to be an ingredient in 52% (39 of 75) of the shampoos and 44% (29 of 66) of the soap products. But each of these products “contained the term ‘hypoallergenic; on the product itself or in the product’s description,” they noted.

“CAPB is a prevalent sensitizer in pediatric patients and should be avoided in patients with AD,” the investigators wrote. That said, it’s not included among the 35 prevalent allergens in the T.R.U.E. test, and they recommended that pediatricians and dermatologists “be aware of common products containing CAPB when counseling patients about their product choices,” considering that CAPB sensitivity is more likely in patients with AD.

The study had no funding source, and the authors had no disclosures.

cpalmer@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Cho SI et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 May. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.036.

(AD) and allergic contact dermatitis, according to a research letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

In the letter, the authors, Reid W. Collis, of Washington University in St. Louis, and David M. Sheinbein, MD, of the division of dermatology at the university, referred to a previous study showing an association between contact sensitivity with CAPB and people with a history of AD. This was supported by the results of their own recent study in pediatric patients, they wrote, which found that reactions to CAPB were “exclusively” in patients with AD.

In the survey, they looked at children’s shampoo and soap products available on online databases of six of the biggest retailers, and analyzed the top 20 best-selling products for each retailer in 2018. Of the unique products, CAPB was found to be an ingredient in 52% (39 of 75) of the shampoos and 44% (29 of 66) of the soap products. But each of these products “contained the term ‘hypoallergenic; on the product itself or in the product’s description,” they noted.

“CAPB is a prevalent sensitizer in pediatric patients and should be avoided in patients with AD,” the investigators wrote. That said, it’s not included among the 35 prevalent allergens in the T.R.U.E. test, and they recommended that pediatricians and dermatologists “be aware of common products containing CAPB when counseling patients about their product choices,” considering that CAPB sensitivity is more likely in patients with AD.

The study had no funding source, and the authors had no disclosures.

cpalmer@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Cho SI et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 May. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.036.

(AD) and allergic contact dermatitis, according to a research letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

In the letter, the authors, Reid W. Collis, of Washington University in St. Louis, and David M. Sheinbein, MD, of the division of dermatology at the university, referred to a previous study showing an association between contact sensitivity with CAPB and people with a history of AD. This was supported by the results of their own recent study in pediatric patients, they wrote, which found that reactions to CAPB were “exclusively” in patients with AD.

In the survey, they looked at children’s shampoo and soap products available on online databases of six of the biggest retailers, and analyzed the top 20 best-selling products for each retailer in 2018. Of the unique products, CAPB was found to be an ingredient in 52% (39 of 75) of the shampoos and 44% (29 of 66) of the soap products. But each of these products “contained the term ‘hypoallergenic; on the product itself or in the product’s description,” they noted.

“CAPB is a prevalent sensitizer in pediatric patients and should be avoided in patients with AD,” the investigators wrote. That said, it’s not included among the 35 prevalent allergens in the T.R.U.E. test, and they recommended that pediatricians and dermatologists “be aware of common products containing CAPB when counseling patients about their product choices,” considering that CAPB sensitivity is more likely in patients with AD.

The study had no funding source, and the authors had no disclosures.

cpalmer@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Cho SI et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 May. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.036.

Suicide prevention one key focus of upcoming NIMH strategic plan

Suicide prevention is a high priority for the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and will be one specific area of focus in the federal agency’s 5-year strategic plan that’s set to be released soon, according to Director Joshua A. Gordon, MD, PhD.

The agency is updating its strategic plan to guide research efforts and priorities over the next 5 years, Dr. Gordon said at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, which was held as a virtual live event.

That strategic plan, which will cover a broader range of priorities, is scheduled to be published “within the next few weeks,” Dr. Gordon said.

Closing the research gap in suicide prevention is a high priority for NIMH, Dr. Gordon said, especially in light of the age-adjusted U.S. suicide rates that have been increasing consistently in men and women for the past 2 decades, as data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

“And although we must acknowledge we don’t quite know why, there is lots of speculation and a little bit of data, but not really conclusive stuff,” he said. “We also recognize that, in addition to trying to understand why, we need to try interventions that will reverse this increase.”

Identifying those at risk for suicide is a key focus of research, according to Dr. Gordon, who highlighted results of the ED-SAFE study, describing it as a “mainstay” of approaches to reducing risk through intervention.

In that recent study, an emergency department (ED)-based suicide prevention intervention cut total suicide attempts by 30%, compared with treatment as usual (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Jun;74[6]:563-70). That intervention included universal suicide risk screening plus secondary screening by the physician in the ED, discharge resources, and post-ED telephone calls intended to reduce suicide risk.

The ED-SAFE study is an example of taking the lessons learned in psychiatry and bringing them to a “broader swath” of individuals who might be at risk, said Dr. Gordon, a research psychiatrist who was a faculty member at Columbia University, New York, prior to being appointed director of NIMH.

“Of course, we’d like to do this not just in emergency rooms, but in primary care offices as well,” said Dr. Gordon, who noted that ongoing studies are aimed at demonstrating similar results in primary care patient populations, including adults and children.

Beyond this ask-and-you-will-find approach, there are “more modern” methods that involve applying predictive modeling and analytics to large data sets, identifying individuals who might not otherwise be suspected as being at risk and getting them into treatment, according to the director.

In one recent report, investigators said a risk prediction method using a machine learning approach on 3.7 million patients across five U.S. health systems was able to detect 38% of suicide attempts a mean of 2.1 years in advance (JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Mar 25;3[3]:3201262).

Machine learning might be able to detect the risk of suicidal behavior in unselected patients, based on these findings and might facilitate development of clinical decision support tools for risk reduction, the investigators said.

“We’re now studying how to implement these algorithms in real-world practice,” Dr. Gordon said.

Beyond identification, new interventions are needed for suicide reduction, he added, calling ketamine infusion “one of the most promising” recent developments that may help reduce suicidal ideation.

he said. “So the question is, can we use this in real-world practice to reduce suicide risk?”

The NIMH focus on suicide prevention will intensify the agency’s focus on recent initiatives in detecting and preventing suicide behavior and ideation in the juvenile justice system, applied research toward the goal of zero-suicide health care systems, and looking at the safety and feasibility of rapid-acting interventions for severe suicide risk, among others, according to Dr. Gordon, who became director of the agency in 2016.

“We have a number of initiatives aimed at taking what we’ve learned over the past few years, and helping that have a significant public health impact,” Dr. Gordon said.

Dr. Gordon reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Gordon JA. APA 2020, Abstract.

Suicide prevention is a high priority for the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and will be one specific area of focus in the federal agency’s 5-year strategic plan that’s set to be released soon, according to Director Joshua A. Gordon, MD, PhD.

The agency is updating its strategic plan to guide research efforts and priorities over the next 5 years, Dr. Gordon said at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, which was held as a virtual live event.

That strategic plan, which will cover a broader range of priorities, is scheduled to be published “within the next few weeks,” Dr. Gordon said.

Closing the research gap in suicide prevention is a high priority for NIMH, Dr. Gordon said, especially in light of the age-adjusted U.S. suicide rates that have been increasing consistently in men and women for the past 2 decades, as data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

“And although we must acknowledge we don’t quite know why, there is lots of speculation and a little bit of data, but not really conclusive stuff,” he said. “We also recognize that, in addition to trying to understand why, we need to try interventions that will reverse this increase.”

Identifying those at risk for suicide is a key focus of research, according to Dr. Gordon, who highlighted results of the ED-SAFE study, describing it as a “mainstay” of approaches to reducing risk through intervention.

In that recent study, an emergency department (ED)-based suicide prevention intervention cut total suicide attempts by 30%, compared with treatment as usual (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Jun;74[6]:563-70). That intervention included universal suicide risk screening plus secondary screening by the physician in the ED, discharge resources, and post-ED telephone calls intended to reduce suicide risk.

The ED-SAFE study is an example of taking the lessons learned in psychiatry and bringing them to a “broader swath” of individuals who might be at risk, said Dr. Gordon, a research psychiatrist who was a faculty member at Columbia University, New York, prior to being appointed director of NIMH.

“Of course, we’d like to do this not just in emergency rooms, but in primary care offices as well,” said Dr. Gordon, who noted that ongoing studies are aimed at demonstrating similar results in primary care patient populations, including adults and children.

Beyond this ask-and-you-will-find approach, there are “more modern” methods that involve applying predictive modeling and analytics to large data sets, identifying individuals who might not otherwise be suspected as being at risk and getting them into treatment, according to the director.

In one recent report, investigators said a risk prediction method using a machine learning approach on 3.7 million patients across five U.S. health systems was able to detect 38% of suicide attempts a mean of 2.1 years in advance (JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Mar 25;3[3]:3201262).

Machine learning might be able to detect the risk of suicidal behavior in unselected patients, based on these findings and might facilitate development of clinical decision support tools for risk reduction, the investigators said.

“We’re now studying how to implement these algorithms in real-world practice,” Dr. Gordon said.

Beyond identification, new interventions are needed for suicide reduction, he added, calling ketamine infusion “one of the most promising” recent developments that may help reduce suicidal ideation.

he said. “So the question is, can we use this in real-world practice to reduce suicide risk?”

The NIMH focus on suicide prevention will intensify the agency’s focus on recent initiatives in detecting and preventing suicide behavior and ideation in the juvenile justice system, applied research toward the goal of zero-suicide health care systems, and looking at the safety and feasibility of rapid-acting interventions for severe suicide risk, among others, according to Dr. Gordon, who became director of the agency in 2016.

“We have a number of initiatives aimed at taking what we’ve learned over the past few years, and helping that have a significant public health impact,” Dr. Gordon said.

Dr. Gordon reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Gordon JA. APA 2020, Abstract.

Suicide prevention is a high priority for the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and will be one specific area of focus in the federal agency’s 5-year strategic plan that’s set to be released soon, according to Director Joshua A. Gordon, MD, PhD.

The agency is updating its strategic plan to guide research efforts and priorities over the next 5 years, Dr. Gordon said at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, which was held as a virtual live event.

That strategic plan, which will cover a broader range of priorities, is scheduled to be published “within the next few weeks,” Dr. Gordon said.

Closing the research gap in suicide prevention is a high priority for NIMH, Dr. Gordon said, especially in light of the age-adjusted U.S. suicide rates that have been increasing consistently in men and women for the past 2 decades, as data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

“And although we must acknowledge we don’t quite know why, there is lots of speculation and a little bit of data, but not really conclusive stuff,” he said. “We also recognize that, in addition to trying to understand why, we need to try interventions that will reverse this increase.”

Identifying those at risk for suicide is a key focus of research, according to Dr. Gordon, who highlighted results of the ED-SAFE study, describing it as a “mainstay” of approaches to reducing risk through intervention.

In that recent study, an emergency department (ED)-based suicide prevention intervention cut total suicide attempts by 30%, compared with treatment as usual (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Jun;74[6]:563-70). That intervention included universal suicide risk screening plus secondary screening by the physician in the ED, discharge resources, and post-ED telephone calls intended to reduce suicide risk.

The ED-SAFE study is an example of taking the lessons learned in psychiatry and bringing them to a “broader swath” of individuals who might be at risk, said Dr. Gordon, a research psychiatrist who was a faculty member at Columbia University, New York, prior to being appointed director of NIMH.

“Of course, we’d like to do this not just in emergency rooms, but in primary care offices as well,” said Dr. Gordon, who noted that ongoing studies are aimed at demonstrating similar results in primary care patient populations, including adults and children.

Beyond this ask-and-you-will-find approach, there are “more modern” methods that involve applying predictive modeling and analytics to large data sets, identifying individuals who might not otherwise be suspected as being at risk and getting them into treatment, according to the director.

In one recent report, investigators said a risk prediction method using a machine learning approach on 3.7 million patients across five U.S. health systems was able to detect 38% of suicide attempts a mean of 2.1 years in advance (JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Mar 25;3[3]:3201262).

Machine learning might be able to detect the risk of suicidal behavior in unselected patients, based on these findings and might facilitate development of clinical decision support tools for risk reduction, the investigators said.

“We’re now studying how to implement these algorithms in real-world practice,” Dr. Gordon said.

Beyond identification, new interventions are needed for suicide reduction, he added, calling ketamine infusion “one of the most promising” recent developments that may help reduce suicidal ideation.

he said. “So the question is, can we use this in real-world practice to reduce suicide risk?”

The NIMH focus on suicide prevention will intensify the agency’s focus on recent initiatives in detecting and preventing suicide behavior and ideation in the juvenile justice system, applied research toward the goal of zero-suicide health care systems, and looking at the safety and feasibility of rapid-acting interventions for severe suicide risk, among others, according to Dr. Gordon, who became director of the agency in 2016.

“We have a number of initiatives aimed at taking what we’ve learned over the past few years, and helping that have a significant public health impact,” Dr. Gordon said.

Dr. Gordon reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Gordon JA. APA 2020, Abstract.

FROM APA 2020

NSDUH data might underestimate substance use by pregnant women

New study suggests rate of alcohol use might be almost 19%

The use of alcohol, tobacco products, and drugs by pregnant women is a substantial problem that may be more prevalent than previously thought, according to researcher Kimberly Yonkers, MD.

Higher levels of substance use during pregnancy means more negative impacts on maternal and fetal, neonatal, and child health. However, one bit of good news is that pregnant women still are less likely than nonpregnant women to engage in such behavior, said Dr. Yonkers, director of psychological medicine and the Center for Wellbeing of Women and Mothers at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Dr. Yonkers said in a featured presentation at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, which was held as a virtual live event.

Tobacco predominates among substances of concern used by pregnant women, with 11.6% reporting past-month use in 2018, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Dr. Yonkers said. Alcohol was next, with 9.9% of pregnant women reporting use in the past month, followed by drugs at 5.4%, of which marijuana was the most common.

Those numbers may jump much higher when focusing on substance use that’s biologically verified, she added, referring to a recent three-center cross-sectional study she and her colleagues published in Addiction (2019 Jun 19. doi: 10.1111/add.14651). In that study, alcohol use was as high as 18.9% among pregnant women who either had positive urine or self-reported use. Similarly, rates of nicotine or nicotine byproduct detected were 27% at one center in the study, and tetrahydrocannabinol reached 29.4% at that same center.

“These numbers are impressive,” Dr. Yonkers told attendees at the meeting. “So what we may be seeing in terms of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, as valuable as it is, is in all likelihood it underestimates the use of substances in pregnancy.”

Substance use goes down in pregnancy as some women become more mindful of perinatal health, though unfortunately, that abstinence is offset by a dramatic rise in substance use in the 6-12 months’ post partum, research suggests.

Interestingly, big differences are found in both abstinence and relapse rates, with some data sets showing that, while alcohol is stopped fairly early, cigarettes are stopped much later, if at all.

On the postpartum side of the equation, relapse rates look similar for cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana, but for some reason, cocaine relapse rates are much lower “That’s kind of nice, and we’d like to be able to understand what it is about this whole process that enabled that relative period of wellness,” Dr. Yonkers said.

Opioid use disorder is rising among pregnant women, just like it is in the general population, and 50% – or possibly even as high as 80% – of babies born to these women will experience neonatal opioid withdrawal, Dr. Yonkers said.

Maternal mortality in the United States increased by 34% from 2008 to 2016; while that’s a sobering statistic, Dr. Yonkers said, opioid-related maternal mortality doubled over that same time period.

“We really have to be mindful that we’re not just talking about taking care of kids and offspring, but we have to take care of moms – it’s really critical,” she said.

With the increasing legalization of cannabis, it’s expected that a lot more cannabis-exposed pregnancies will be seen in clinical practice, and some studies are starting to show an increase in prevalence in the preconception, prenatal, and postpartum period.

While some people feel that cannabis is benign, more data are needed, according to Dr. Yonkers, who said that cannabis and its metabolites cross the blood/placenta and blood/milk barriers, and that cannabinoid receptors are “very important” to fertility, implantation, and fetal development. One study recently published linked cannabis use in pregnancy to significant increases in preterm birth rates (JAMA. 2019 Jun 18;322[2]:145-52).

“We don’t really have a context for this, so we don’t really know what’s going to have an impact, and what’s not,” Dr. Yonkers said.

While both standard and novel treatments could help in the quest to achieve and maintain well-being in this unique patient population, Dr. Yonkers said that health equity and universal approaches to care might be needed to more comprehensively address the problem, which means taking a close look at how much money women have, the resources available to them, and where they live.

In many communities, eliminating inequalities in care will be critical to successfully addressing substance use issues in pregnant women, agreed Maureen Sayres Van Niel, MD, a specialist in women’s psychiatry in Boston and president of the Women’s Caucus of the APA.

“What we see is such a disparity in the delivery of care to women who are poor and living in communities where the socioeconomic and financial problems are very severe,” Dr. Van Niel said in an interview. “Unless we address these disparities, women will not be getting the kind of health care that they really need to have in the perinatal period.”

Dr. Yonkers reported a disclosure related to UpToDate.

New study suggests rate of alcohol use might be almost 19%

New study suggests rate of alcohol use might be almost 19%

The use of alcohol, tobacco products, and drugs by pregnant women is a substantial problem that may be more prevalent than previously thought, according to researcher Kimberly Yonkers, MD.

Higher levels of substance use during pregnancy means more negative impacts on maternal and fetal, neonatal, and child health. However, one bit of good news is that pregnant women still are less likely than nonpregnant women to engage in such behavior, said Dr. Yonkers, director of psychological medicine and the Center for Wellbeing of Women and Mothers at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Dr. Yonkers said in a featured presentation at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, which was held as a virtual live event.

Tobacco predominates among substances of concern used by pregnant women, with 11.6% reporting past-month use in 2018, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Dr. Yonkers said. Alcohol was next, with 9.9% of pregnant women reporting use in the past month, followed by drugs at 5.4%, of which marijuana was the most common.

Those numbers may jump much higher when focusing on substance use that’s biologically verified, she added, referring to a recent three-center cross-sectional study she and her colleagues published in Addiction (2019 Jun 19. doi: 10.1111/add.14651). In that study, alcohol use was as high as 18.9% among pregnant women who either had positive urine or self-reported use. Similarly, rates of nicotine or nicotine byproduct detected were 27% at one center in the study, and tetrahydrocannabinol reached 29.4% at that same center.

“These numbers are impressive,” Dr. Yonkers told attendees at the meeting. “So what we may be seeing in terms of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, as valuable as it is, is in all likelihood it underestimates the use of substances in pregnancy.”

Substance use goes down in pregnancy as some women become more mindful of perinatal health, though unfortunately, that abstinence is offset by a dramatic rise in substance use in the 6-12 months’ post partum, research suggests.

Interestingly, big differences are found in both abstinence and relapse rates, with some data sets showing that, while alcohol is stopped fairly early, cigarettes are stopped much later, if at all.

On the postpartum side of the equation, relapse rates look similar for cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana, but for some reason, cocaine relapse rates are much lower “That’s kind of nice, and we’d like to be able to understand what it is about this whole process that enabled that relative period of wellness,” Dr. Yonkers said.

Opioid use disorder is rising among pregnant women, just like it is in the general population, and 50% – or possibly even as high as 80% – of babies born to these women will experience neonatal opioid withdrawal, Dr. Yonkers said.

Maternal mortality in the United States increased by 34% from 2008 to 2016; while that’s a sobering statistic, Dr. Yonkers said, opioid-related maternal mortality doubled over that same time period.

“We really have to be mindful that we’re not just talking about taking care of kids and offspring, but we have to take care of moms – it’s really critical,” she said.

With the increasing legalization of cannabis, it’s expected that a lot more cannabis-exposed pregnancies will be seen in clinical practice, and some studies are starting to show an increase in prevalence in the preconception, prenatal, and postpartum period.

While some people feel that cannabis is benign, more data are needed, according to Dr. Yonkers, who said that cannabis and its metabolites cross the blood/placenta and blood/milk barriers, and that cannabinoid receptors are “very important” to fertility, implantation, and fetal development. One study recently published linked cannabis use in pregnancy to significant increases in preterm birth rates (JAMA. 2019 Jun 18;322[2]:145-52).

“We don’t really have a context for this, so we don’t really know what’s going to have an impact, and what’s not,” Dr. Yonkers said.

While both standard and novel treatments could help in the quest to achieve and maintain well-being in this unique patient population, Dr. Yonkers said that health equity and universal approaches to care might be needed to more comprehensively address the problem, which means taking a close look at how much money women have, the resources available to them, and where they live.

In many communities, eliminating inequalities in care will be critical to successfully addressing substance use issues in pregnant women, agreed Maureen Sayres Van Niel, MD, a specialist in women’s psychiatry in Boston and president of the Women’s Caucus of the APA.

“What we see is such a disparity in the delivery of care to women who are poor and living in communities where the socioeconomic and financial problems are very severe,” Dr. Van Niel said in an interview. “Unless we address these disparities, women will not be getting the kind of health care that they really need to have in the perinatal period.”

Dr. Yonkers reported a disclosure related to UpToDate.

The use of alcohol, tobacco products, and drugs by pregnant women is a substantial problem that may be more prevalent than previously thought, according to researcher Kimberly Yonkers, MD.

Higher levels of substance use during pregnancy means more negative impacts on maternal and fetal, neonatal, and child health. However, one bit of good news is that pregnant women still are less likely than nonpregnant women to engage in such behavior, said Dr. Yonkers, director of psychological medicine and the Center for Wellbeing of Women and Mothers at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Dr. Yonkers said in a featured presentation at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, which was held as a virtual live event.

Tobacco predominates among substances of concern used by pregnant women, with 11.6% reporting past-month use in 2018, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Dr. Yonkers said. Alcohol was next, with 9.9% of pregnant women reporting use in the past month, followed by drugs at 5.4%, of which marijuana was the most common.

Those numbers may jump much higher when focusing on substance use that’s biologically verified, she added, referring to a recent three-center cross-sectional study she and her colleagues published in Addiction (2019 Jun 19. doi: 10.1111/add.14651). In that study, alcohol use was as high as 18.9% among pregnant women who either had positive urine or self-reported use. Similarly, rates of nicotine or nicotine byproduct detected were 27% at one center in the study, and tetrahydrocannabinol reached 29.4% at that same center.

“These numbers are impressive,” Dr. Yonkers told attendees at the meeting. “So what we may be seeing in terms of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, as valuable as it is, is in all likelihood it underestimates the use of substances in pregnancy.”

Substance use goes down in pregnancy as some women become more mindful of perinatal health, though unfortunately, that abstinence is offset by a dramatic rise in substance use in the 6-12 months’ post partum, research suggests.

Interestingly, big differences are found in both abstinence and relapse rates, with some data sets showing that, while alcohol is stopped fairly early, cigarettes are stopped much later, if at all.

On the postpartum side of the equation, relapse rates look similar for cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana, but for some reason, cocaine relapse rates are much lower “That’s kind of nice, and we’d like to be able to understand what it is about this whole process that enabled that relative period of wellness,” Dr. Yonkers said.

Opioid use disorder is rising among pregnant women, just like it is in the general population, and 50% – or possibly even as high as 80% – of babies born to these women will experience neonatal opioid withdrawal, Dr. Yonkers said.

Maternal mortality in the United States increased by 34% from 2008 to 2016; while that’s a sobering statistic, Dr. Yonkers said, opioid-related maternal mortality doubled over that same time period.

“We really have to be mindful that we’re not just talking about taking care of kids and offspring, but we have to take care of moms – it’s really critical,” she said.

With the increasing legalization of cannabis, it’s expected that a lot more cannabis-exposed pregnancies will be seen in clinical practice, and some studies are starting to show an increase in prevalence in the preconception, prenatal, and postpartum period.

While some people feel that cannabis is benign, more data are needed, according to Dr. Yonkers, who said that cannabis and its metabolites cross the blood/placenta and blood/milk barriers, and that cannabinoid receptors are “very important” to fertility, implantation, and fetal development. One study recently published linked cannabis use in pregnancy to significant increases in preterm birth rates (JAMA. 2019 Jun 18;322[2]:145-52).

“We don’t really have a context for this, so we don’t really know what’s going to have an impact, and what’s not,” Dr. Yonkers said.

While both standard and novel treatments could help in the quest to achieve and maintain well-being in this unique patient population, Dr. Yonkers said that health equity and universal approaches to care might be needed to more comprehensively address the problem, which means taking a close look at how much money women have, the resources available to them, and where they live.

In many communities, eliminating inequalities in care will be critical to successfully addressing substance use issues in pregnant women, agreed Maureen Sayres Van Niel, MD, a specialist in women’s psychiatry in Boston and president of the Women’s Caucus of the APA.

“What we see is such a disparity in the delivery of care to women who are poor and living in communities where the socioeconomic and financial problems are very severe,” Dr. Van Niel said in an interview. “Unless we address these disparities, women will not be getting the kind of health care that they really need to have in the perinatal period.”

Dr. Yonkers reported a disclosure related to UpToDate.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM APA 2020

Sepsis patients with hypothermia face greater mortality risk

Background: Fevers (like other vital sign abnormalities) often trigger interventions from providers. However, hypothermia (temperature under 36° C) may also be associated with higher mortality.

Study design: Retrospective subanalysis of a previous study (Focused Outcome Research on Emergency Care for Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Sepsis and Trauma [FORECAST]).

Setting: Adult patients with severe sepsis based on Sepsis-2 in 59 ICUs in Japan.

Synopsis: The study involved 1,143 patients admitted to ICUs with severe sepsis (62.6% with septic shock). The median age was 73 years with a median APACHE II and SOFA scores of 22 and 9, respectively. Core temperatures were measured on admission to ICU with patients categorized into three arms: temperature under 36° C (hypothermic), temperature 36°-38° C, and febrile patients with temperature greater than 38° C. Of studied patients, 11.1% were hypothermic on presentation. These patients were older, sicker (higher APACHE/SOFA scores), had lower body mass indexes, and had higher prevalence of septic shock than did the febrile patients. Hypothermic patients fared worse in every clinical outcome measured – in-hospital mortality, 28-day mortality, ventilator-free days, ICU-free days, length of hospital stay, and likelihood of discharge home. The odds ratio of in-hospital mortality for hypothermic patients, compared with reference febrile patients, was 1.76 (95% CI, 1.14-2.73). Patients with hypothermia were also significantly less likely to receive the entire 3-hour resuscitation bundle, including broad-spectrum antibiotics (56.3%) versus 60.8% of patients with temperature 36-38° C and 71.1% for febrile group (P = .003).

Bottom line: Hypothermia in patients with severe sepsis is associated with a significantly higher disease severity, mortality risk, and lower implementation of sepsis bundles. More emphasis on earlier identification and treatment of this specific patient population appears needed.

Citation: Kushimoto S et al. Impact of body temperature abnormalities on the implementation of sepsis bundles and outcomes in patients with severe sepsis: A retrospective sub-analysis of the focused outcome of research of emergency care for acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis and trauma study. Crit Care Med. 2019 May;47(5):691-9.

Dr. Sekaran is a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Background: Fevers (like other vital sign abnormalities) often trigger interventions from providers. However, hypothermia (temperature under 36° C) may also be associated with higher mortality.

Study design: Retrospective subanalysis of a previous study (Focused Outcome Research on Emergency Care for Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Sepsis and Trauma [FORECAST]).

Setting: Adult patients with severe sepsis based on Sepsis-2 in 59 ICUs in Japan.

Synopsis: The study involved 1,143 patients admitted to ICUs with severe sepsis (62.6% with septic shock). The median age was 73 years with a median APACHE II and SOFA scores of 22 and 9, respectively. Core temperatures were measured on admission to ICU with patients categorized into three arms: temperature under 36° C (hypothermic), temperature 36°-38° C, and febrile patients with temperature greater than 38° C. Of studied patients, 11.1% were hypothermic on presentation. These patients were older, sicker (higher APACHE/SOFA scores), had lower body mass indexes, and had higher prevalence of septic shock than did the febrile patients. Hypothermic patients fared worse in every clinical outcome measured – in-hospital mortality, 28-day mortality, ventilator-free days, ICU-free days, length of hospital stay, and likelihood of discharge home. The odds ratio of in-hospital mortality for hypothermic patients, compared with reference febrile patients, was 1.76 (95% CI, 1.14-2.73). Patients with hypothermia were also significantly less likely to receive the entire 3-hour resuscitation bundle, including broad-spectrum antibiotics (56.3%) versus 60.8% of patients with temperature 36-38° C and 71.1% for febrile group (P = .003).

Bottom line: Hypothermia in patients with severe sepsis is associated with a significantly higher disease severity, mortality risk, and lower implementation of sepsis bundles. More emphasis on earlier identification and treatment of this specific patient population appears needed.

Citation: Kushimoto S et al. Impact of body temperature abnormalities on the implementation of sepsis bundles and outcomes in patients with severe sepsis: A retrospective sub-analysis of the focused outcome of research of emergency care for acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis and trauma study. Crit Care Med. 2019 May;47(5):691-9.

Dr. Sekaran is a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Background: Fevers (like other vital sign abnormalities) often trigger interventions from providers. However, hypothermia (temperature under 36° C) may also be associated with higher mortality.

Study design: Retrospective subanalysis of a previous study (Focused Outcome Research on Emergency Care for Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Sepsis and Trauma [FORECAST]).

Setting: Adult patients with severe sepsis based on Sepsis-2 in 59 ICUs in Japan.

Synopsis: The study involved 1,143 patients admitted to ICUs with severe sepsis (62.6% with septic shock). The median age was 73 years with a median APACHE II and SOFA scores of 22 and 9, respectively. Core temperatures were measured on admission to ICU with patients categorized into three arms: temperature under 36° C (hypothermic), temperature 36°-38° C, and febrile patients with temperature greater than 38° C. Of studied patients, 11.1% were hypothermic on presentation. These patients were older, sicker (higher APACHE/SOFA scores), had lower body mass indexes, and had higher prevalence of septic shock than did the febrile patients. Hypothermic patients fared worse in every clinical outcome measured – in-hospital mortality, 28-day mortality, ventilator-free days, ICU-free days, length of hospital stay, and likelihood of discharge home. The odds ratio of in-hospital mortality for hypothermic patients, compared with reference febrile patients, was 1.76 (95% CI, 1.14-2.73). Patients with hypothermia were also significantly less likely to receive the entire 3-hour resuscitation bundle, including broad-spectrum antibiotics (56.3%) versus 60.8% of patients with temperature 36-38° C and 71.1% for febrile group (P = .003).

Bottom line: Hypothermia in patients with severe sepsis is associated with a significantly higher disease severity, mortality risk, and lower implementation of sepsis bundles. More emphasis on earlier identification and treatment of this specific patient population appears needed.

Citation: Kushimoto S et al. Impact of body temperature abnormalities on the implementation of sepsis bundles and outcomes in patients with severe sepsis: A retrospective sub-analysis of the focused outcome of research of emergency care for acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis and trauma study. Crit Care Med. 2019 May;47(5):691-9.

Dr. Sekaran is a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Fountains of Wayne, and a hospitalist’s first day, remembered

Like many in the health care field, I have found it hard to watch the news over these past couple of months when it seems that almost every story is about COVID-19 or its repercussions. Luckily, I have two young daughters who “encourage” me to listen to the Frozen 2 soundtrack instead of putting on the evening news when I get home from work. Still, news manages to seep through my defenses. As I scrolled through some headlines recently, I learned of the death of musician Adam Schlesinger from COVID-19. He wasn’t a household name, but his death still hit me in unexpected ways.

I started internship in late June 2005, in a city (Portland, Ore.) about as different from my previous home (Dallas) as any two places can possibly be. I think the day before internship started still ranks as the most nervous of my life. I’m not sure how I slept at all that night, but somehow I did and arrived at the Portland Veterans Affairs Hospital the following morning to start my new career.

And then … nothing happened. Early on that first day, the electronic medical records crashed, and no patients were admitted during our time on “short call.” My upper level resident took care of the one or two established patients on the team (both discharged), so I ended the day with records that would not be broken during the remainder of my residency: 0 notes written, 0 patients seen. Perhaps the most successful first day that any intern, anywhere has ever had, although it prepared me quite poorly for all the subsequent days.

Since I had some time on my hands, I made the 20-minute walk to one of my new hometown’s record stores where Fountains of Wayne (FOW) was playing an acoustic in-store set. Their album from a few years prior, “Welcome Interstate Managers,” was in heavy rotation when I made the drive from Dallas to Portland. It was (and is) a great album for long drives – melodic, catchy, and (mostly) up-tempo. Adam and the band’s singer, Chris Collingwood, played several songs that night on the store’s stage. Then they headed out to the next city, and I headed back home and on to many far-busier days of residency.

We would cross paths again a decade later. I moved back to Texas and became a hospitalist. It turns out that, if you have enough hospitalists of a certain age and if enough of those hospitalists have unearned confidence in their musical ability, then a covers band will undoubtedly be formed. And so, it happened here in San Antonio. We were not selective in our song choices – we played songs from every decade of the last 50 years, bands as popular as the Beatles and as indie as the Rentals. And we played some FOW.

Our band (which will go nameless here so that our YouTube recordings are more difficult to find) played a grand total of one gig during our years of intermittent practicing. That one gig was my wedding rehearsal dinner and the penultimate song we played was “Stacy’s Mom,” which is notable for being both FOW’s biggest hit and a completely inappropriate song to play at a wedding rehearsal dinner. The crowd was probably around the same size as the one that had seen Adam and Chris play in Portland 10 years prior. I don’t think the applause we received was quite as genuine or deserved, though.

After Adam and Chris played their gig, there was an autograph session and I took home a signed poster. Last year, I decided to take it out of storage and hang it in my office. The date of the show and the first day of my physician career, a date now nearly 15 years ago, is written in psychedelic typography at the bottom. The store that I went to that day is no longer there, a victim of progress like so many other record stores across the country. Another location of the same store is still open in Portland. I hope that it and all the other small book and music stores across the country can survive this current crisis, but I know that many will not.

So, here’s to you Adam, and to all the others who have lost their lives to this terrible illness. As a small token of remembrance, I’ll be playing some Fountains of Wayne on the drive home tonight. It’s not quite the same as playing it on a cross-country drive, but hopefully, we will all be able to do that again soon.

Dr. Sehgal is a clinical associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at the South Texas Veterans Health Care System and UT-Health San Antonio. He is a member of the editorial advisory board for The Hospitalist.

Like many in the health care field, I have found it hard to watch the news over these past couple of months when it seems that almost every story is about COVID-19 or its repercussions. Luckily, I have two young daughters who “encourage” me to listen to the Frozen 2 soundtrack instead of putting on the evening news when I get home from work. Still, news manages to seep through my defenses. As I scrolled through some headlines recently, I learned of the death of musician Adam Schlesinger from COVID-19. He wasn’t a household name, but his death still hit me in unexpected ways.

I started internship in late June 2005, in a city (Portland, Ore.) about as different from my previous home (Dallas) as any two places can possibly be. I think the day before internship started still ranks as the most nervous of my life. I’m not sure how I slept at all that night, but somehow I did and arrived at the Portland Veterans Affairs Hospital the following morning to start my new career.

And then … nothing happened. Early on that first day, the electronic medical records crashed, and no patients were admitted during our time on “short call.” My upper level resident took care of the one or two established patients on the team (both discharged), so I ended the day with records that would not be broken during the remainder of my residency: 0 notes written, 0 patients seen. Perhaps the most successful first day that any intern, anywhere has ever had, although it prepared me quite poorly for all the subsequent days.

Since I had some time on my hands, I made the 20-minute walk to one of my new hometown’s record stores where Fountains of Wayne (FOW) was playing an acoustic in-store set. Their album from a few years prior, “Welcome Interstate Managers,” was in heavy rotation when I made the drive from Dallas to Portland. It was (and is) a great album for long drives – melodic, catchy, and (mostly) up-tempo. Adam and the band’s singer, Chris Collingwood, played several songs that night on the store’s stage. Then they headed out to the next city, and I headed back home and on to many far-busier days of residency.

We would cross paths again a decade later. I moved back to Texas and became a hospitalist. It turns out that, if you have enough hospitalists of a certain age and if enough of those hospitalists have unearned confidence in their musical ability, then a covers band will undoubtedly be formed. And so, it happened here in San Antonio. We were not selective in our song choices – we played songs from every decade of the last 50 years, bands as popular as the Beatles and as indie as the Rentals. And we played some FOW.

Our band (which will go nameless here so that our YouTube recordings are more difficult to find) played a grand total of one gig during our years of intermittent practicing. That one gig was my wedding rehearsal dinner and the penultimate song we played was “Stacy’s Mom,” which is notable for being both FOW’s biggest hit and a completely inappropriate song to play at a wedding rehearsal dinner. The crowd was probably around the same size as the one that had seen Adam and Chris play in Portland 10 years prior. I don’t think the applause we received was quite as genuine or deserved, though.

After Adam and Chris played their gig, there was an autograph session and I took home a signed poster. Last year, I decided to take it out of storage and hang it in my office. The date of the show and the first day of my physician career, a date now nearly 15 years ago, is written in psychedelic typography at the bottom. The store that I went to that day is no longer there, a victim of progress like so many other record stores across the country. Another location of the same store is still open in Portland. I hope that it and all the other small book and music stores across the country can survive this current crisis, but I know that many will not.

So, here’s to you Adam, and to all the others who have lost their lives to this terrible illness. As a small token of remembrance, I’ll be playing some Fountains of Wayne on the drive home tonight. It’s not quite the same as playing it on a cross-country drive, but hopefully, we will all be able to do that again soon.

Dr. Sehgal is a clinical associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at the South Texas Veterans Health Care System and UT-Health San Antonio. He is a member of the editorial advisory board for The Hospitalist.

Like many in the health care field, I have found it hard to watch the news over these past couple of months when it seems that almost every story is about COVID-19 or its repercussions. Luckily, I have two young daughters who “encourage” me to listen to the Frozen 2 soundtrack instead of putting on the evening news when I get home from work. Still, news manages to seep through my defenses. As I scrolled through some headlines recently, I learned of the death of musician Adam Schlesinger from COVID-19. He wasn’t a household name, but his death still hit me in unexpected ways.

I started internship in late June 2005, in a city (Portland, Ore.) about as different from my previous home (Dallas) as any two places can possibly be. I think the day before internship started still ranks as the most nervous of my life. I’m not sure how I slept at all that night, but somehow I did and arrived at the Portland Veterans Affairs Hospital the following morning to start my new career.

And then … nothing happened. Early on that first day, the electronic medical records crashed, and no patients were admitted during our time on “short call.” My upper level resident took care of the one or two established patients on the team (both discharged), so I ended the day with records that would not be broken during the remainder of my residency: 0 notes written, 0 patients seen. Perhaps the most successful first day that any intern, anywhere has ever had, although it prepared me quite poorly for all the subsequent days.

Since I had some time on my hands, I made the 20-minute walk to one of my new hometown’s record stores where Fountains of Wayne (FOW) was playing an acoustic in-store set. Their album from a few years prior, “Welcome Interstate Managers,” was in heavy rotation when I made the drive from Dallas to Portland. It was (and is) a great album for long drives – melodic, catchy, and (mostly) up-tempo. Adam and the band’s singer, Chris Collingwood, played several songs that night on the store’s stage. Then they headed out to the next city, and I headed back home and on to many far-busier days of residency.

We would cross paths again a decade later. I moved back to Texas and became a hospitalist. It turns out that, if you have enough hospitalists of a certain age and if enough of those hospitalists have unearned confidence in their musical ability, then a covers band will undoubtedly be formed. And so, it happened here in San Antonio. We were not selective in our song choices – we played songs from every decade of the last 50 years, bands as popular as the Beatles and as indie as the Rentals. And we played some FOW.

Our band (which will go nameless here so that our YouTube recordings are more difficult to find) played a grand total of one gig during our years of intermittent practicing. That one gig was my wedding rehearsal dinner and the penultimate song we played was “Stacy’s Mom,” which is notable for being both FOW’s biggest hit and a completely inappropriate song to play at a wedding rehearsal dinner. The crowd was probably around the same size as the one that had seen Adam and Chris play in Portland 10 years prior. I don’t think the applause we received was quite as genuine or deserved, though.

After Adam and Chris played their gig, there was an autograph session and I took home a signed poster. Last year, I decided to take it out of storage and hang it in my office. The date of the show and the first day of my physician career, a date now nearly 15 years ago, is written in psychedelic typography at the bottom. The store that I went to that day is no longer there, a victim of progress like so many other record stores across the country. Another location of the same store is still open in Portland. I hope that it and all the other small book and music stores across the country can survive this current crisis, but I know that many will not.

So, here’s to you Adam, and to all the others who have lost their lives to this terrible illness. As a small token of remembrance, I’ll be playing some Fountains of Wayne on the drive home tonight. It’s not quite the same as playing it on a cross-country drive, but hopefully, we will all be able to do that again soon.

Dr. Sehgal is a clinical associate professor of medicine in the division of general and hospital medicine at the South Texas Veterans Health Care System and UT-Health San Antonio. He is a member of the editorial advisory board for The Hospitalist.

Teledermatology Fast Facts

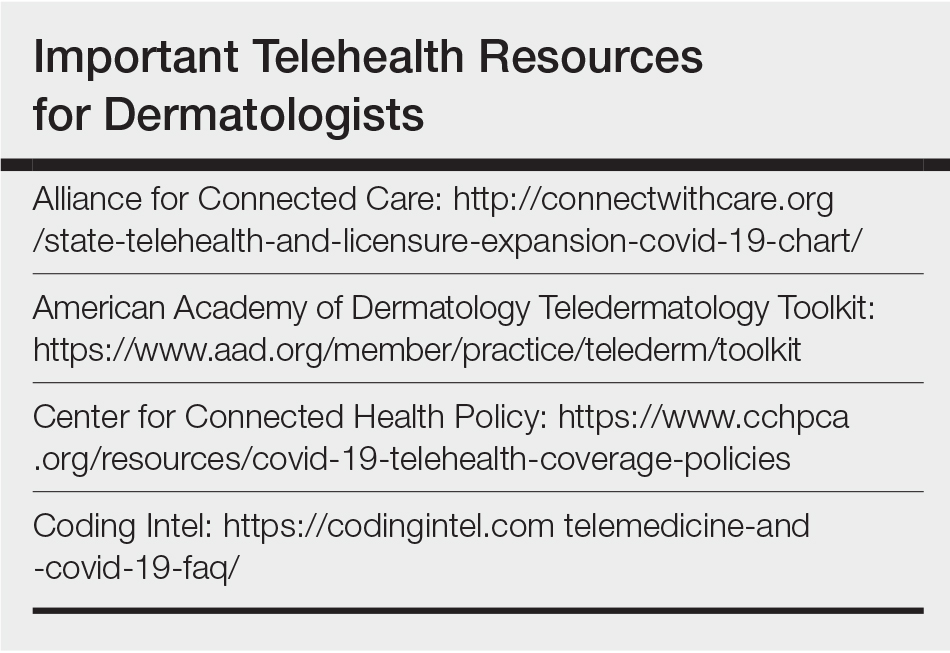

Due to the impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, many patients are working from home, which has led to a unique opportunity for dermatologists to step in and continue to care for their patients at home via telemedicine. With recent waivers and guidance from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), insurance coverage has been expanded for telehealth services, usually at the same level as an in-person visit. This editorial provides guidance for implementing telehealth services in your practice, and a tip sheet is available online for you to save and print. Please note that this information is changing on a day-to-day basis, so refer to the resources in the Table to get the latest updates.

Billing and Coding

The best reimbursements are for live telemedicine that emulates an outpatient visit and is billed using the same Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (99201–99215). Previously, Medicare did not allow direct-to-patient visits to be billed, instead requiring a waiver for these services to be provided in underserved areas. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this requirement has been lifted, allowing all patients to be seen from any originating site (eg, the patient’s home).

Previously, the CMS had issued guidelines for telehealth visits that required that a physician-patient relationship be established in person prior to conducting telemedicine visits. These guidelines also have been waived for the duration of this public health emergency, allowing physicians to conduct new patient visits via telehealth and bill Medicare. Many commercial payors also are covering new patient visits via telehealth; however, it is best to check the patient’s plan first, as some plans may have different requirements or restrictions on allowable CPT codes and/or place of service. Prior requirements that physicians at a distant site (ie, the physician providing telemedicine services) be located at a site of clinical care also have been relaxed, thus allowing physicians to be located anywhere while providing services, even for those who are confined to their homes.

In general, commercial payors are covering telehealth visits at 100% of an in-person visit. Although COVID-19–related visits are covered by law, many payors including Aetna, Anthem, Blue Cross Blue Shield, Cigna, Emblem Health, Humana, and United Healthcare have indicated that they will waive all telehealth co-pays for a limited time, including visits not related to COVID-19. At the time of publication, only Aetna has issued a formal policy to this effect, so it is best to check with the insurer.1,2 However, it is important to note that regional and employer-specific plans may have different policies, so it is best to check with the insurance plans directly to confirm coverage and co-pay status.

Coding should be performed using the usual new/established patient visit codes for outpatients (99201–99215). A place of service (POS) code of 02 previously was used for all telehealth visits; however, the CMS is allowing offices to bill with their usual POS (generally POS 11) and modifier -95 in an updated rule that is active during this public health crisis. This change allows access to higher reimbursements, as POS 02 visits are paid at lower facility fee rates. Commercial insurers have varying policies on POS that are changing, so it is best to check with them individually.

In certain states, store-and-forward services may be billed using a GQ modifier for Medicaid; however, the remote check-in and telephone codes for Medicare do not reimburse well and generally are best avoided if a live telemedicine encounter is possible, as it provides better patient care and direct counseling capabilities, similar to an in-person visit. The CMS has indicated that it is now covering telephone visits (99441-99443) so that providers can contact patients through an audio-only device and bill for the encounter. Generally speaking, telephone visits reimburse the same or more than the virtual check-in codes (G2010/G2012) as long as the telephone encounter is more than 5-minutes long. Digital visits also are available (99421-99423), which include both store-and-forward photographs and a telephone call, but the reimbursements are similar to the telephone-only visit codes.3

Although the CMS has relaxed regulations for physicians to provide care across state lines, not all state licensing authorities have adopted similar measures, and the CMS waiver only applies to federally funded programs. It is important to check with state medical licensing authorities to see whether you are authorized to provide care if your patient is not located within the state where you hold your license at the time of the visit. Many states, but not all, have waived this requirement or have set up very expedient ways to apply for telemedicine licenses.

The CMS also released guidance that rules for documentation requirements have been temporarily relaxed,3 such that visits should be billed at a level of service consistent with either medical decision-making or total time spent by the provider, including face-to-face and non–face-to-face time spent on the patient. (Note: If billing by time, which usually is not advised, use the CMS definitions of time-based coding.) History and physical examination criteria do not have to be met.

Workflow

In general, it is best to maintain your current workflow as much as possible, with a live video encounter replacing only the patient interaction portion of the visit. You will need to maintain an infrastructure for scheduling visits, collecting co-pays (eg, over the telephone prior to the video visit), and documentation/billing.

It is best to have one device for conducting the actual video visit (eg, a laptop, tablet, or smartphone) and a separate device to use for documentation (eg, another device to access the electronic medical record). The CMS has advised that it will not enforce Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) rules,4 allowing physicians to use video conferencing and chat applications such as FaceTime, Skype, or Google Hangouts; however, patient safety is still an issue, and it is imperative to make sure you identify the patient correctly upon starting the visit. During the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous telehealth companies are offering temporary free video conferencing software that is HIPAA compliant, such as Doximity, VSee, Doxy.me, and Medweb. If you are able to go through one of these vendors, you will be able to continue conducting some telemedicine visits after the public health emergency, which may be helpful to your practice.

For some visits, such as acne patients on isotretinoin, you can write for a standing laboratory order that can be drawn at a laboratory center near your patient, and you can perform the counseling via telemedicine. For patients on isotretinoin, iPledge has issued a program update allowing the use of at-home pregnancy tests during the pandemic. The results must be communicated to the provider and documented with a time/date.5

Video Visit Tips and Pearls

Make sure to have well-defined parameters about what can be triaged via a single video visit. Suggestions include no total-body skin examinations and a limit of 1 rash or 2 lesions. Provide a disclaimer that it is not always possible to tell whether or not a lesion is concerning via a video visit, and the patient may have to come in for a biopsy at some point.

It is better to overcall via telemedicine than to undercall. Unless something is a very obvious seborrheic keratosis, skin tag, cherry angioma, or other benign lesion, it might be reasonable to tell a patient to come in for further evaluation of a worrisome lesion after things get back to normal. A static photograph from the patient can be helpful so it is clear what lesion is being examined during the current visit. If the patient has a skin cancer at a distant site in the future, there will be no doubt as to what lesion you examined. Having the capability to receive static images from the patient to serve as representative photographs of their chief concern is very helpful before the visit. Often, these images turn out to be better diagnostically than the live video itself, which can be compressed and show inaccurate colors. Some of the telemedicine vendors have this feature built-in, which is preferable. If you are asking patients to send you emails, it is better to have access to a HIPAA-compliant email inbox to avoid any potential issues down the line.

When scheduling a video visit, have your schedulers specifically tell patients that they should be on a high-speed Wi-Fi connection with good lighting in the room. You would be surprised that this is not intuitive for everyone!

Finally, most telemedicine visits are relatively short and to the point. In the beginning, start by scheduling patients every 15 to 20 minutes to allow for technical difficulties, but ultimately plan to be seeing patients at least every 10 minutes—it can be quite efficient!

- America’s Health Insurance Providers. Health insurance providers respond to coronavirus (COVID-19). https://www.ahip.org/health-insurance-providers-respond-to-coronavirus-covid-19/. Published April 22, 2020. Accessed April 23, 2020.

- Private payer coverage during COVID-19. American College of Physicians website. https://www.acponline.org/system/files/documents/clinical_information/resources/covid19/payer_chart_covid-19.pdf. Updated April 22, 2020. Accessed April 23, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid programs; policy and regulatory revisions in response to the COVID-19 public health emergency. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/covid-final-ifc.pdf. Published March 26, 2020. Accessed April 23, 2020.

- Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. US Department of Health and Human Services website. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html. Updated March 30, 2020. Accessed April 23, 2020.

- Program update. iPledge website. https://www.ipledgeprogram.com/iPledgeUI/home.u. Accessed April 23, 2020.

Due to the impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, many patients are working from home, which has led to a unique opportunity for dermatologists to step in and continue to care for their patients at home via telemedicine. With recent waivers and guidance from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), insurance coverage has been expanded for telehealth services, usually at the same level as an in-person visit. This editorial provides guidance for implementing telehealth services in your practice, and a tip sheet is available online for you to save and print. Please note that this information is changing on a day-to-day basis, so refer to the resources in the Table to get the latest updates.

Billing and Coding