User login

Cardiovascular Effects of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Patients With Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma at the VA San Diego Healthcare System (FULL)

Patients who have or are at high risk for developing cardiovascular disease and who are taking tyrosine kinase inhibitors for renal cell carcinoma should receive routine cardiovascular event monitoring during the first 4 months of therapy.

Targeted therapies have transformed the treatment of many malignant diseases by inhibiting molecular pathways involved in tumor growth and oncogenesis. Although these therapies can prevent disease progression, toxicities often result. Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is one of many cancers that responds well to these therapies.

RCC accounts for 2% to 3% of all malignancies in adults worldwide. About 30% of patients with RCC present with metastatic or advanced disease.1 Cytokine therapy was the standard of care until multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) were developed. Over the past 12 years, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 6 TKIs for the treatment of RCC: axitinib, cabozantinib, lenvatinib, pazopanib, sorafenib, and sunitinib. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) is one of many tyrosine kinase receptors targeted by these medications. This mechanism prevents angiogenesis and consequently increases the risk for hypertension, bleeding, and clot formation.

Given these risks, many patients were excluded from the initial clinical trials of these medications if they had a history of uncontrolled hypertension, advanced heart failure (HF), or a significant cardiovascular (CV) event within 6 months prior to study enrollment. Many of these studies did not report the incidence of CV events (other than hypertension) that occurred during the early trials.2 The recommended monitoring for TKI therapies is focused mainly on blood pressure. For patients on pazopanib and sunitinib therapy, baseline and periodic electrocardiograms (ECGs) are recommended; echocardiograms are recommended only for patients with a history of cardiac disease.3,4 In patients on sorafenib therapy, ECG is recommended for those at risk for corrected QT (QTc) intervalprolongation.5

According to a meta-analysis of the literature published between 1966 and 2013,many studies reported a CV toxicity risk associated with the TKIs used in RCC treatment.6 However, some studies have found modest, not clinically significant changes in cardiac function in patients with advanced disease. In 2013, Hall and colleagues found 73% of patients they studied experienced some type of CV toxicity, whereas only 33% of patients had CV toxicity when hypertension was excluded.7 Interestingly, Rini and colleagues found that RCC patients receiving sunitinib had better response rates and progression-free survival when they developed hypertension compared with those who did not develop hypertension.8

A review of several studies revealed similar numbers in patients on TKI therapy presenting with symptomatic HF, but Hall and colleagues found that 27% of patients developed asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction.7,9,10 These results suggest routine monitoring may allow for appropriate preventive interventions. In patients receiving TKI therapy, CV events, including QTc prolongation, left ventricular HF, myocardial infarction (MI), hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, and stroke, were commonly reported by investigators.7,9,10 Currently, there are no studies of the incidence of CV events for the 5 TKIs (axitinib, cabozantinib, pazopanib, sorafenib, sunitinib) in this patient population.

TKI therapy may require cardiac monitoring of all patients, as studies have associated TKIs with CV toxicity in varying degrees. Therefore, the authors set out to determine the incidence of CV events as well as time to first CV event in patients with and without a history of CV disease (CVD) who received a TKI for advanced RCC. More frequent monitoring for CV toxicity may present opportunities for clinical interventions for all patients on TKI therapy—especially for those with HF or other diseases in which the goal of therapy is to prevent disease progression. As TKIs have emerged as the standard treatment option for advanced RCC, many patients will continue therapy until disease progression or intolerable toxicity. Identifying and using appropriate monitoring parameters can lead to preventive interventions that allow patients to benefit from TKI therapy longer. At the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) San Diego Healthcare System (VASDHS), patients undergo routine cardiac monitoring at the discretion of the provider.

In this retrospective study, the authors wanted to determine the incidence of CV events in patients with and without a history of CVD who were receiving TKIs for advanced RCC. The authors also wanted to evaluate time to CV event from start of therapy in order to determine how often monitoring may be needed. The outcomes of this study may lead to a change in practice and development of monitoring parameters to ensure appropriate and adequate management of TKI therapy in RCC.

Methods

Each year, the VASDHS oncology team diagnose 5 to 10 patients with RCC who begin TKI therapy. When sorafenib was approved by the FDA in 2005, VASDHS estimated that about 100 of its patients had an RCC diagnosis and would be treated with a TKI between December 2005 and July 2017.

The authors identified VASDHS patients with a diagnosis of advanced RCC who received axitinib, cabozantinib, pazopanib, sorafenib, or sunitinib between December 1, 2005 and July 31, 2017. Patients were included if they had been on therapy for at least 30 days. The VASDHS pharmacy informatics team assisted in extracting a list of patients with an ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis of RCC and using prescription fills for any of the 5 TKIs previously noted. Medical records were reviewed for frequency of prescription fills, age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, TKI treatment duration, previous history of CVD, ethnicity, and smoking status. If documented, the incidence of CV events was reviewed for each patient at 0, 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. Patients who received medications (Appendix) for their CVD were assessed for adherence based on history of prescription refills from their medical records. Adherence was evaluated for the duration that patients were concurrently taking an oral TKI. The institutional review board at VASDHS approved the study design.

All patients included in this study started TKI therapy since the December 2005 FDA approval of sorafenib, the first oral TKI for treatment of RCC. Each new start was recorded as a separate event, regardless of previous oral TKI therapy. Albiges and colleagues found that the approximate median time from starting TKI therapy to complete response was 12.6 months, and the median duration of TKI therapy after complete response was 10.3 months.11 Based on these results, the follow-up period for patients in this study was 2 years after the start of each TKI therapy. For data analysis, patients were stratified by CVD history (yes or no). In addition, composite outcomes were evaluated to identify a potential cumulative increased risk for CV events for patients who had been on multiple TKI therapies.

For this study, CV toxicities were characterized using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.03; severity of adverse events (AEs) was graded 1 to 5. CTCAE commonly has been used to assess AEs in oncology clinical trials. The CV AEs selected for this study included QTc prolongation, hypertension, left ventricular dysfunction, stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), and pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Primary outcomes included incidence of CV events and time to first CV event after initiation of TKI therapy. Secondary outcomes included changes in ECG or echocardiogram results at 0, 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. Secondary outcomes at scheduled time points were not readily available for every patient, but any available time points were gathered to aid in identifying an optimal period for cardiac monitoring. In addition, patients with a history of CVD were evaluated for adherence to common first-line therapies for each disease.

A Fischer exact test was used to compare the incidence of CV events in patients with and without a history of CVD (significance level, α = 0.05). A subgroup analysis was used to compare the incidence of CV events in patients who experienced a CV event (significance level, α = 0.05). A Kaplan-Meier survival curve was used to determine time to first CV event. A log-rank test with significance level set at α = 0.05 also was used.

Results

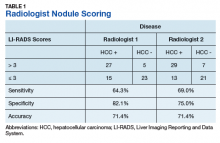

An initial database search identified 134 patients who received TKI therapy at VASDHS between December 1, 2005 and July 31, 2017. According to retrospective chart review, 54 patients met the inclusion criteria for the study (Table 1).

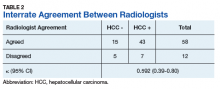

Patients without a history of CVD (17%) did not experience any CV events while on TKI therapy. Of the patients with a history of CVD, 9 (20%) experienced ≥ 1 CV event. Fifty-five percent of the events experienced were hypertension. One patient experienced QTc prolongation, and 2 patients experienced MI. As already noted, each new start of TKI was recorded as a separate event, regardless of previous TKI therapy. Among patients with a history of CVD, 2 experienced 2 CV events. Overall, 11 CV events occurred among patients who received ≥ 1 TKI, corresponding to an overall incidence of 24% (Table 2).

Of the 13 patients who were exposed to ≥ 2 TKI therapies, 2 experienced a CV event. Both patients were started on sunitinib and were switched to sorafenib. One of these used sunitinib for 7 months, experienced a partial response and was switched to sorafenib (with a 3-month break between therapies). The second patient was on sunitinib for 24 months, with multiple doses held because of low blood counts and diarrhea. While on sunitinib, this patient experienced a HF exacerbation, determined to be caused by the underlying disease. This event occurred 17 months after sunitinib was started, and therapy was continued for another 7 months. The patient was switched to sorafenib because of poor tolerability and disease progression. While on sorafenib, this patient experienced grade 1 QTc prolongation.

Discussion

Of the available oral TKI therapies for RCC, sunitinib and sorafenib have the most data associated with nonhypertensive CV toxicity.2,7-10,12 Instudies, the percentage of patients who experienced CV toxicity while on sunitinib or sorafenib has ranged widely, from 2.7% to 33.8%; the variance may be attributable to differences in how institutions report CV toxicities.7-9

According to the prescribing information for TKIs, hypertension is frequently reported as an AE for all 5 TKIs, and BP monitoring is recommended.3,4 However, the development of hypertension with these TKIs has been associated with response to therapy.7 With pazopanib, sorafenib, and sunitinib, there is a higher incidence of other AEs: edema, HF, MI, and QTc prolongation. Baseline ECG is recommended for all patients started on pazopanib and sunitinib and for patients with a history of CVD who are started on sorafenib. An ECG is recommended for patients with a history of CVD who are started on pazopanib and sunitinib.

Even with the medication prescribing information recommendations, it is unclear how frequently patients should be monitored. At VASDHS, CV monitoring for any patient started on a TKI remains at the discretion of the oncologist. There are concerns that ordering cardiac monitoring tests, which might be unnecessary, will change or guide therapy. In this study, data evaluation revealed 1 patient who experienced a CV event had a CVD history that was not documented in the patient’s medical history. It is important that providers obtain a detailed clinical assessment of patients CV history during each visit to determine whether CV monitoring should be considered. Patients also may benefit from additional counseling to emphasize the importance of adherence to CV medication therapy to reduce the incidence of these events.

Data from this study indicate that routine CV monitoring should be considered in patients with CVD, in keeping with current medication prescribing information recommendations. Of the patients who had a CV event, 54% experienced hypertension, 18% MI, and 28% stroke, QTc prolongation, or congestive HF.

Limitations

This retrospective study had several limitations. Many patients did not have a baseline cardiac monitoring test or any monitoring during therapy. Often, a cardiac test was performed only when the patient was symptomatic or experiencing a CV event. In addition, because of intolerance or nonadherence to therapy, many patients discontinued treatment early, before completing 30 days. That axitinib and cabozantinib are newer therapies and not first-line at VASDHS during the data collection period accounts for the small number of patients on these therapies. Therapy was shorter for patients started on pazopanib, axitinib, and cabozantinib than it was for patients on sunitinib and sorafenib. Duration of therapy may affect treatment-related events, but the majority of patients in this study experienced an event within 4 months of therapy. About half of the patients who experienced an event were nonadherent to their CV medication regimen. Another potential limitation is that this study was conducted at VASDHS, where most patients are male (RCC incidence is 2:1 male:female).

Conclusion

In this study, CV events occurred in 24% of patients with a history of CVD; 11% of these events were nonhypertensive. Baseline cardiac monitoring was not performed for most patients started on TKI therapy, but tests were performed once patients became symptomatic. The study results suggest that high-risk patients should undergo routine cardiac monitoring during the first 4 months of TKI therapy, in keeping with medication package insert monitoring recommendations. Cardiac monitoring of high-risk patients will allow for earlier identification of cardiac decline and offer opportunities for interventions, such as pharmacist-driven protocols to start CV medications. Implementation of this study’s recommendations should be evaluated to determine whether outcomes improve with routine cardiac monitoring in these high-risk patients.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, FrontlineMedical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects— before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Rini, BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9807):1931-1939.

2. Tolcher AW, Appleman LJ, Shapiro GI, et al. A phase I open-label study evaluating the cardiovascular safety of sorafenib in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;67(4):751-764.

3. Votrient [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2017.

4. Sutent [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Labs; 2018.

5. Nexavar [package insert]. Wayne, NJ; Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2018.

6. Ghatalia P, Morgan CJ, Je Y, et al. Congestive heart failure with vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2015;94:228–237.

7. Hall PS, Harshman LC, Srinivas S, Witteles RM. The frequency and severity of cardiovascular toxicity from targeted therapy in advanced renal cell carcinoma patients. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1(1):72-78.

8. Rini BI, Cohen DP, Lu DR, et al. Hypertension as a biomarker of efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(9):763-773.

9. Richards CJ, Je Y, Schutz FA, et al. Incidence and risk of congestive heart failure in patients with renal and nonrenal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3450-3456.

10. Schmidinger M, Zielinski CC, Vogl UM, et al. Cardiac toxicity of sunitinib and sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(32):5204-5212.

11. Albiges L, Oudard S, Negrier S, et al. Complete remission with tyrosine kinase inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(5):482-487.

12. Jang S, Zheng C, Tsai HT, et al. Cardiovascular toxicity after antiangiogenic therapy in persons older than 65 years with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2016;122(1):124-130

13. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

14. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. JACC. 2017;70(6):776-803.

15. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2160-2236.

16. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. JACC. 2013;61(4):e78-e140.

17. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(24):e139-e228.

18. Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(1):67-119.

Patients who have or are at high risk for developing cardiovascular disease and who are taking tyrosine kinase inhibitors for renal cell carcinoma should receive routine cardiovascular event monitoring during the first 4 months of therapy.

Patients who have or are at high risk for developing cardiovascular disease and who are taking tyrosine kinase inhibitors for renal cell carcinoma should receive routine cardiovascular event monitoring during the first 4 months of therapy.

Targeted therapies have transformed the treatment of many malignant diseases by inhibiting molecular pathways involved in tumor growth and oncogenesis. Although these therapies can prevent disease progression, toxicities often result. Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is one of many cancers that responds well to these therapies.

RCC accounts for 2% to 3% of all malignancies in adults worldwide. About 30% of patients with RCC present with metastatic or advanced disease.1 Cytokine therapy was the standard of care until multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) were developed. Over the past 12 years, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 6 TKIs for the treatment of RCC: axitinib, cabozantinib, lenvatinib, pazopanib, sorafenib, and sunitinib. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) is one of many tyrosine kinase receptors targeted by these medications. This mechanism prevents angiogenesis and consequently increases the risk for hypertension, bleeding, and clot formation.

Given these risks, many patients were excluded from the initial clinical trials of these medications if they had a history of uncontrolled hypertension, advanced heart failure (HF), or a significant cardiovascular (CV) event within 6 months prior to study enrollment. Many of these studies did not report the incidence of CV events (other than hypertension) that occurred during the early trials.2 The recommended monitoring for TKI therapies is focused mainly on blood pressure. For patients on pazopanib and sunitinib therapy, baseline and periodic electrocardiograms (ECGs) are recommended; echocardiograms are recommended only for patients with a history of cardiac disease.3,4 In patients on sorafenib therapy, ECG is recommended for those at risk for corrected QT (QTc) intervalprolongation.5

According to a meta-analysis of the literature published between 1966 and 2013,many studies reported a CV toxicity risk associated with the TKIs used in RCC treatment.6 However, some studies have found modest, not clinically significant changes in cardiac function in patients with advanced disease. In 2013, Hall and colleagues found 73% of patients they studied experienced some type of CV toxicity, whereas only 33% of patients had CV toxicity when hypertension was excluded.7 Interestingly, Rini and colleagues found that RCC patients receiving sunitinib had better response rates and progression-free survival when they developed hypertension compared with those who did not develop hypertension.8

A review of several studies revealed similar numbers in patients on TKI therapy presenting with symptomatic HF, but Hall and colleagues found that 27% of patients developed asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction.7,9,10 These results suggest routine monitoring may allow for appropriate preventive interventions. In patients receiving TKI therapy, CV events, including QTc prolongation, left ventricular HF, myocardial infarction (MI), hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, and stroke, were commonly reported by investigators.7,9,10 Currently, there are no studies of the incidence of CV events for the 5 TKIs (axitinib, cabozantinib, pazopanib, sorafenib, sunitinib) in this patient population.

TKI therapy may require cardiac monitoring of all patients, as studies have associated TKIs with CV toxicity in varying degrees. Therefore, the authors set out to determine the incidence of CV events as well as time to first CV event in patients with and without a history of CV disease (CVD) who received a TKI for advanced RCC. More frequent monitoring for CV toxicity may present opportunities for clinical interventions for all patients on TKI therapy—especially for those with HF or other diseases in which the goal of therapy is to prevent disease progression. As TKIs have emerged as the standard treatment option for advanced RCC, many patients will continue therapy until disease progression or intolerable toxicity. Identifying and using appropriate monitoring parameters can lead to preventive interventions that allow patients to benefit from TKI therapy longer. At the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) San Diego Healthcare System (VASDHS), patients undergo routine cardiac monitoring at the discretion of the provider.

In this retrospective study, the authors wanted to determine the incidence of CV events in patients with and without a history of CVD who were receiving TKIs for advanced RCC. The authors also wanted to evaluate time to CV event from start of therapy in order to determine how often monitoring may be needed. The outcomes of this study may lead to a change in practice and development of monitoring parameters to ensure appropriate and adequate management of TKI therapy in RCC.

Methods

Each year, the VASDHS oncology team diagnose 5 to 10 patients with RCC who begin TKI therapy. When sorafenib was approved by the FDA in 2005, VASDHS estimated that about 100 of its patients had an RCC diagnosis and would be treated with a TKI between December 2005 and July 2017.

The authors identified VASDHS patients with a diagnosis of advanced RCC who received axitinib, cabozantinib, pazopanib, sorafenib, or sunitinib between December 1, 2005 and July 31, 2017. Patients were included if they had been on therapy for at least 30 days. The VASDHS pharmacy informatics team assisted in extracting a list of patients with an ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis of RCC and using prescription fills for any of the 5 TKIs previously noted. Medical records were reviewed for frequency of prescription fills, age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, TKI treatment duration, previous history of CVD, ethnicity, and smoking status. If documented, the incidence of CV events was reviewed for each patient at 0, 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. Patients who received medications (Appendix) for their CVD were assessed for adherence based on history of prescription refills from their medical records. Adherence was evaluated for the duration that patients were concurrently taking an oral TKI. The institutional review board at VASDHS approved the study design.

All patients included in this study started TKI therapy since the December 2005 FDA approval of sorafenib, the first oral TKI for treatment of RCC. Each new start was recorded as a separate event, regardless of previous oral TKI therapy. Albiges and colleagues found that the approximate median time from starting TKI therapy to complete response was 12.6 months, and the median duration of TKI therapy after complete response was 10.3 months.11 Based on these results, the follow-up period for patients in this study was 2 years after the start of each TKI therapy. For data analysis, patients were stratified by CVD history (yes or no). In addition, composite outcomes were evaluated to identify a potential cumulative increased risk for CV events for patients who had been on multiple TKI therapies.

For this study, CV toxicities were characterized using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.03; severity of adverse events (AEs) was graded 1 to 5. CTCAE commonly has been used to assess AEs in oncology clinical trials. The CV AEs selected for this study included QTc prolongation, hypertension, left ventricular dysfunction, stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), and pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Primary outcomes included incidence of CV events and time to first CV event after initiation of TKI therapy. Secondary outcomes included changes in ECG or echocardiogram results at 0, 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. Secondary outcomes at scheduled time points were not readily available for every patient, but any available time points were gathered to aid in identifying an optimal period for cardiac monitoring. In addition, patients with a history of CVD were evaluated for adherence to common first-line therapies for each disease.

A Fischer exact test was used to compare the incidence of CV events in patients with and without a history of CVD (significance level, α = 0.05). A subgroup analysis was used to compare the incidence of CV events in patients who experienced a CV event (significance level, α = 0.05). A Kaplan-Meier survival curve was used to determine time to first CV event. A log-rank test with significance level set at α = 0.05 also was used.

Results

An initial database search identified 134 patients who received TKI therapy at VASDHS between December 1, 2005 and July 31, 2017. According to retrospective chart review, 54 patients met the inclusion criteria for the study (Table 1).

Patients without a history of CVD (17%) did not experience any CV events while on TKI therapy. Of the patients with a history of CVD, 9 (20%) experienced ≥ 1 CV event. Fifty-five percent of the events experienced were hypertension. One patient experienced QTc prolongation, and 2 patients experienced MI. As already noted, each new start of TKI was recorded as a separate event, regardless of previous TKI therapy. Among patients with a history of CVD, 2 experienced 2 CV events. Overall, 11 CV events occurred among patients who received ≥ 1 TKI, corresponding to an overall incidence of 24% (Table 2).

Of the 13 patients who were exposed to ≥ 2 TKI therapies, 2 experienced a CV event. Both patients were started on sunitinib and were switched to sorafenib. One of these used sunitinib for 7 months, experienced a partial response and was switched to sorafenib (with a 3-month break between therapies). The second patient was on sunitinib for 24 months, with multiple doses held because of low blood counts and diarrhea. While on sunitinib, this patient experienced a HF exacerbation, determined to be caused by the underlying disease. This event occurred 17 months after sunitinib was started, and therapy was continued for another 7 months. The patient was switched to sorafenib because of poor tolerability and disease progression. While on sorafenib, this patient experienced grade 1 QTc prolongation.

Discussion

Of the available oral TKI therapies for RCC, sunitinib and sorafenib have the most data associated with nonhypertensive CV toxicity.2,7-10,12 Instudies, the percentage of patients who experienced CV toxicity while on sunitinib or sorafenib has ranged widely, from 2.7% to 33.8%; the variance may be attributable to differences in how institutions report CV toxicities.7-9

According to the prescribing information for TKIs, hypertension is frequently reported as an AE for all 5 TKIs, and BP monitoring is recommended.3,4 However, the development of hypertension with these TKIs has been associated with response to therapy.7 With pazopanib, sorafenib, and sunitinib, there is a higher incidence of other AEs: edema, HF, MI, and QTc prolongation. Baseline ECG is recommended for all patients started on pazopanib and sunitinib and for patients with a history of CVD who are started on sorafenib. An ECG is recommended for patients with a history of CVD who are started on pazopanib and sunitinib.

Even with the medication prescribing information recommendations, it is unclear how frequently patients should be monitored. At VASDHS, CV monitoring for any patient started on a TKI remains at the discretion of the oncologist. There are concerns that ordering cardiac monitoring tests, which might be unnecessary, will change or guide therapy. In this study, data evaluation revealed 1 patient who experienced a CV event had a CVD history that was not documented in the patient’s medical history. It is important that providers obtain a detailed clinical assessment of patients CV history during each visit to determine whether CV monitoring should be considered. Patients also may benefit from additional counseling to emphasize the importance of adherence to CV medication therapy to reduce the incidence of these events.

Data from this study indicate that routine CV monitoring should be considered in patients with CVD, in keeping with current medication prescribing information recommendations. Of the patients who had a CV event, 54% experienced hypertension, 18% MI, and 28% stroke, QTc prolongation, or congestive HF.

Limitations

This retrospective study had several limitations. Many patients did not have a baseline cardiac monitoring test or any monitoring during therapy. Often, a cardiac test was performed only when the patient was symptomatic or experiencing a CV event. In addition, because of intolerance or nonadherence to therapy, many patients discontinued treatment early, before completing 30 days. That axitinib and cabozantinib are newer therapies and not first-line at VASDHS during the data collection period accounts for the small number of patients on these therapies. Therapy was shorter for patients started on pazopanib, axitinib, and cabozantinib than it was for patients on sunitinib and sorafenib. Duration of therapy may affect treatment-related events, but the majority of patients in this study experienced an event within 4 months of therapy. About half of the patients who experienced an event were nonadherent to their CV medication regimen. Another potential limitation is that this study was conducted at VASDHS, where most patients are male (RCC incidence is 2:1 male:female).

Conclusion

In this study, CV events occurred in 24% of patients with a history of CVD; 11% of these events were nonhypertensive. Baseline cardiac monitoring was not performed for most patients started on TKI therapy, but tests were performed once patients became symptomatic. The study results suggest that high-risk patients should undergo routine cardiac monitoring during the first 4 months of TKI therapy, in keeping with medication package insert monitoring recommendations. Cardiac monitoring of high-risk patients will allow for earlier identification of cardiac decline and offer opportunities for interventions, such as pharmacist-driven protocols to start CV medications. Implementation of this study’s recommendations should be evaluated to determine whether outcomes improve with routine cardiac monitoring in these high-risk patients.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, FrontlineMedical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects— before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Targeted therapies have transformed the treatment of many malignant diseases by inhibiting molecular pathways involved in tumor growth and oncogenesis. Although these therapies can prevent disease progression, toxicities often result. Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is one of many cancers that responds well to these therapies.

RCC accounts for 2% to 3% of all malignancies in adults worldwide. About 30% of patients with RCC present with metastatic or advanced disease.1 Cytokine therapy was the standard of care until multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) were developed. Over the past 12 years, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 6 TKIs for the treatment of RCC: axitinib, cabozantinib, lenvatinib, pazopanib, sorafenib, and sunitinib. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) is one of many tyrosine kinase receptors targeted by these medications. This mechanism prevents angiogenesis and consequently increases the risk for hypertension, bleeding, and clot formation.

Given these risks, many patients were excluded from the initial clinical trials of these medications if they had a history of uncontrolled hypertension, advanced heart failure (HF), or a significant cardiovascular (CV) event within 6 months prior to study enrollment. Many of these studies did not report the incidence of CV events (other than hypertension) that occurred during the early trials.2 The recommended monitoring for TKI therapies is focused mainly on blood pressure. For patients on pazopanib and sunitinib therapy, baseline and periodic electrocardiograms (ECGs) are recommended; echocardiograms are recommended only for patients with a history of cardiac disease.3,4 In patients on sorafenib therapy, ECG is recommended for those at risk for corrected QT (QTc) intervalprolongation.5

According to a meta-analysis of the literature published between 1966 and 2013,many studies reported a CV toxicity risk associated with the TKIs used in RCC treatment.6 However, some studies have found modest, not clinically significant changes in cardiac function in patients with advanced disease. In 2013, Hall and colleagues found 73% of patients they studied experienced some type of CV toxicity, whereas only 33% of patients had CV toxicity when hypertension was excluded.7 Interestingly, Rini and colleagues found that RCC patients receiving sunitinib had better response rates and progression-free survival when they developed hypertension compared with those who did not develop hypertension.8

A review of several studies revealed similar numbers in patients on TKI therapy presenting with symptomatic HF, but Hall and colleagues found that 27% of patients developed asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction.7,9,10 These results suggest routine monitoring may allow for appropriate preventive interventions. In patients receiving TKI therapy, CV events, including QTc prolongation, left ventricular HF, myocardial infarction (MI), hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, and stroke, were commonly reported by investigators.7,9,10 Currently, there are no studies of the incidence of CV events for the 5 TKIs (axitinib, cabozantinib, pazopanib, sorafenib, sunitinib) in this patient population.

TKI therapy may require cardiac monitoring of all patients, as studies have associated TKIs with CV toxicity in varying degrees. Therefore, the authors set out to determine the incidence of CV events as well as time to first CV event in patients with and without a history of CV disease (CVD) who received a TKI for advanced RCC. More frequent monitoring for CV toxicity may present opportunities for clinical interventions for all patients on TKI therapy—especially for those with HF or other diseases in which the goal of therapy is to prevent disease progression. As TKIs have emerged as the standard treatment option for advanced RCC, many patients will continue therapy until disease progression or intolerable toxicity. Identifying and using appropriate monitoring parameters can lead to preventive interventions that allow patients to benefit from TKI therapy longer. At the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) San Diego Healthcare System (VASDHS), patients undergo routine cardiac monitoring at the discretion of the provider.

In this retrospective study, the authors wanted to determine the incidence of CV events in patients with and without a history of CVD who were receiving TKIs for advanced RCC. The authors also wanted to evaluate time to CV event from start of therapy in order to determine how often monitoring may be needed. The outcomes of this study may lead to a change in practice and development of monitoring parameters to ensure appropriate and adequate management of TKI therapy in RCC.

Methods

Each year, the VASDHS oncology team diagnose 5 to 10 patients with RCC who begin TKI therapy. When sorafenib was approved by the FDA in 2005, VASDHS estimated that about 100 of its patients had an RCC diagnosis and would be treated with a TKI between December 2005 and July 2017.

The authors identified VASDHS patients with a diagnosis of advanced RCC who received axitinib, cabozantinib, pazopanib, sorafenib, or sunitinib between December 1, 2005 and July 31, 2017. Patients were included if they had been on therapy for at least 30 days. The VASDHS pharmacy informatics team assisted in extracting a list of patients with an ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis of RCC and using prescription fills for any of the 5 TKIs previously noted. Medical records were reviewed for frequency of prescription fills, age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, TKI treatment duration, previous history of CVD, ethnicity, and smoking status. If documented, the incidence of CV events was reviewed for each patient at 0, 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. Patients who received medications (Appendix) for their CVD were assessed for adherence based on history of prescription refills from their medical records. Adherence was evaluated for the duration that patients were concurrently taking an oral TKI. The institutional review board at VASDHS approved the study design.

All patients included in this study started TKI therapy since the December 2005 FDA approval of sorafenib, the first oral TKI for treatment of RCC. Each new start was recorded as a separate event, regardless of previous oral TKI therapy. Albiges and colleagues found that the approximate median time from starting TKI therapy to complete response was 12.6 months, and the median duration of TKI therapy after complete response was 10.3 months.11 Based on these results, the follow-up period for patients in this study was 2 years after the start of each TKI therapy. For data analysis, patients were stratified by CVD history (yes or no). In addition, composite outcomes were evaluated to identify a potential cumulative increased risk for CV events for patients who had been on multiple TKI therapies.

For this study, CV toxicities were characterized using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.03; severity of adverse events (AEs) was graded 1 to 5. CTCAE commonly has been used to assess AEs in oncology clinical trials. The CV AEs selected for this study included QTc prolongation, hypertension, left ventricular dysfunction, stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), and pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Primary outcomes included incidence of CV events and time to first CV event after initiation of TKI therapy. Secondary outcomes included changes in ECG or echocardiogram results at 0, 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. Secondary outcomes at scheduled time points were not readily available for every patient, but any available time points were gathered to aid in identifying an optimal period for cardiac monitoring. In addition, patients with a history of CVD were evaluated for adherence to common first-line therapies for each disease.

A Fischer exact test was used to compare the incidence of CV events in patients with and without a history of CVD (significance level, α = 0.05). A subgroup analysis was used to compare the incidence of CV events in patients who experienced a CV event (significance level, α = 0.05). A Kaplan-Meier survival curve was used to determine time to first CV event. A log-rank test with significance level set at α = 0.05 also was used.

Results

An initial database search identified 134 patients who received TKI therapy at VASDHS between December 1, 2005 and July 31, 2017. According to retrospective chart review, 54 patients met the inclusion criteria for the study (Table 1).

Patients without a history of CVD (17%) did not experience any CV events while on TKI therapy. Of the patients with a history of CVD, 9 (20%) experienced ≥ 1 CV event. Fifty-five percent of the events experienced were hypertension. One patient experienced QTc prolongation, and 2 patients experienced MI. As already noted, each new start of TKI was recorded as a separate event, regardless of previous TKI therapy. Among patients with a history of CVD, 2 experienced 2 CV events. Overall, 11 CV events occurred among patients who received ≥ 1 TKI, corresponding to an overall incidence of 24% (Table 2).

Of the 13 patients who were exposed to ≥ 2 TKI therapies, 2 experienced a CV event. Both patients were started on sunitinib and were switched to sorafenib. One of these used sunitinib for 7 months, experienced a partial response and was switched to sorafenib (with a 3-month break between therapies). The second patient was on sunitinib for 24 months, with multiple doses held because of low blood counts and diarrhea. While on sunitinib, this patient experienced a HF exacerbation, determined to be caused by the underlying disease. This event occurred 17 months after sunitinib was started, and therapy was continued for another 7 months. The patient was switched to sorafenib because of poor tolerability and disease progression. While on sorafenib, this patient experienced grade 1 QTc prolongation.

Discussion

Of the available oral TKI therapies for RCC, sunitinib and sorafenib have the most data associated with nonhypertensive CV toxicity.2,7-10,12 Instudies, the percentage of patients who experienced CV toxicity while on sunitinib or sorafenib has ranged widely, from 2.7% to 33.8%; the variance may be attributable to differences in how institutions report CV toxicities.7-9

According to the prescribing information for TKIs, hypertension is frequently reported as an AE for all 5 TKIs, and BP monitoring is recommended.3,4 However, the development of hypertension with these TKIs has been associated with response to therapy.7 With pazopanib, sorafenib, and sunitinib, there is a higher incidence of other AEs: edema, HF, MI, and QTc prolongation. Baseline ECG is recommended for all patients started on pazopanib and sunitinib and for patients with a history of CVD who are started on sorafenib. An ECG is recommended for patients with a history of CVD who are started on pazopanib and sunitinib.

Even with the medication prescribing information recommendations, it is unclear how frequently patients should be monitored. At VASDHS, CV monitoring for any patient started on a TKI remains at the discretion of the oncologist. There are concerns that ordering cardiac monitoring tests, which might be unnecessary, will change or guide therapy. In this study, data evaluation revealed 1 patient who experienced a CV event had a CVD history that was not documented in the patient’s medical history. It is important that providers obtain a detailed clinical assessment of patients CV history during each visit to determine whether CV monitoring should be considered. Patients also may benefit from additional counseling to emphasize the importance of adherence to CV medication therapy to reduce the incidence of these events.

Data from this study indicate that routine CV monitoring should be considered in patients with CVD, in keeping with current medication prescribing information recommendations. Of the patients who had a CV event, 54% experienced hypertension, 18% MI, and 28% stroke, QTc prolongation, or congestive HF.

Limitations

This retrospective study had several limitations. Many patients did not have a baseline cardiac monitoring test or any monitoring during therapy. Often, a cardiac test was performed only when the patient was symptomatic or experiencing a CV event. In addition, because of intolerance or nonadherence to therapy, many patients discontinued treatment early, before completing 30 days. That axitinib and cabozantinib are newer therapies and not first-line at VASDHS during the data collection period accounts for the small number of patients on these therapies. Therapy was shorter for patients started on pazopanib, axitinib, and cabozantinib than it was for patients on sunitinib and sorafenib. Duration of therapy may affect treatment-related events, but the majority of patients in this study experienced an event within 4 months of therapy. About half of the patients who experienced an event were nonadherent to their CV medication regimen. Another potential limitation is that this study was conducted at VASDHS, where most patients are male (RCC incidence is 2:1 male:female).

Conclusion

In this study, CV events occurred in 24% of patients with a history of CVD; 11% of these events were nonhypertensive. Baseline cardiac monitoring was not performed for most patients started on TKI therapy, but tests were performed once patients became symptomatic. The study results suggest that high-risk patients should undergo routine cardiac monitoring during the first 4 months of TKI therapy, in keeping with medication package insert monitoring recommendations. Cardiac monitoring of high-risk patients will allow for earlier identification of cardiac decline and offer opportunities for interventions, such as pharmacist-driven protocols to start CV medications. Implementation of this study’s recommendations should be evaluated to determine whether outcomes improve with routine cardiac monitoring in these high-risk patients.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, FrontlineMedical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects— before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Rini, BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9807):1931-1939.

2. Tolcher AW, Appleman LJ, Shapiro GI, et al. A phase I open-label study evaluating the cardiovascular safety of sorafenib in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;67(4):751-764.

3. Votrient [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2017.

4. Sutent [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Labs; 2018.

5. Nexavar [package insert]. Wayne, NJ; Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2018.

6. Ghatalia P, Morgan CJ, Je Y, et al. Congestive heart failure with vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2015;94:228–237.

7. Hall PS, Harshman LC, Srinivas S, Witteles RM. The frequency and severity of cardiovascular toxicity from targeted therapy in advanced renal cell carcinoma patients. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1(1):72-78.

8. Rini BI, Cohen DP, Lu DR, et al. Hypertension as a biomarker of efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(9):763-773.

9. Richards CJ, Je Y, Schutz FA, et al. Incidence and risk of congestive heart failure in patients with renal and nonrenal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3450-3456.

10. Schmidinger M, Zielinski CC, Vogl UM, et al. Cardiac toxicity of sunitinib and sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(32):5204-5212.

11. Albiges L, Oudard S, Negrier S, et al. Complete remission with tyrosine kinase inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(5):482-487.

12. Jang S, Zheng C, Tsai HT, et al. Cardiovascular toxicity after antiangiogenic therapy in persons older than 65 years with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2016;122(1):124-130

13. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

14. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. JACC. 2017;70(6):776-803.

15. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2160-2236.

16. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. JACC. 2013;61(4):e78-e140.

17. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(24):e139-e228.

18. Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(1):67-119.

1. Rini, BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9807):1931-1939.

2. Tolcher AW, Appleman LJ, Shapiro GI, et al. A phase I open-label study evaluating the cardiovascular safety of sorafenib in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;67(4):751-764.

3. Votrient [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2017.

4. Sutent [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Labs; 2018.

5. Nexavar [package insert]. Wayne, NJ; Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2018.

6. Ghatalia P, Morgan CJ, Je Y, et al. Congestive heart failure with vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2015;94:228–237.

7. Hall PS, Harshman LC, Srinivas S, Witteles RM. The frequency and severity of cardiovascular toxicity from targeted therapy in advanced renal cell carcinoma patients. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1(1):72-78.

8. Rini BI, Cohen DP, Lu DR, et al. Hypertension as a biomarker of efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(9):763-773.

9. Richards CJ, Je Y, Schutz FA, et al. Incidence and risk of congestive heart failure in patients with renal and nonrenal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3450-3456.

10. Schmidinger M, Zielinski CC, Vogl UM, et al. Cardiac toxicity of sunitinib and sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(32):5204-5212.

11. Albiges L, Oudard S, Negrier S, et al. Complete remission with tyrosine kinase inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(5):482-487.

12. Jang S, Zheng C, Tsai HT, et al. Cardiovascular toxicity after antiangiogenic therapy in persons older than 65 years with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2016;122(1):124-130

13. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

14. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. JACC. 2017;70(6):776-803.

15. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2160-2236.

16. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. JACC. 2013;61(4):e78-e140.

17. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(24):e139-e228.

18. Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(1):67-119.

Sharing Cancer Care Information Across VA Health Care Systems (FULL)

A telementoring program based on the Specialty Care Access Network Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes model shared information about cancer care across VA health Care systems.

In 2016, the Cancer Care Coordinator at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Healthcare System (VACT) in West Haven partnered with the VA New England Healthcare System to use its telementoring program. The VA Specialty Care Access Network Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (VA ECHO) was used to present a series of educational conferences on cancer care. This article describes our experience implementing the program and reviews participant feedback gathered from voluntary surveys.

Background

In 2011, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Office of Healthcare Transformation launched VA ECHO, a telementoring program for primary care providers (PCPs) and patient-aligned care team staff. VACT was selected as 1 of 7 hub sites across the US. The VA ECHO system uses video and online technology to provide PCPs with case-based specialist consultation and didactic education. The system enables providers at any VA location to participate in online and telephone conferences in real time. The presentations are recorded and made available online to VA providers through a secure site.

VA ECHO is based on the highly successful Project ECHO model established by Sanjeev Arora and the University of New Mexico in 2007.1 The rationale for Project ECHO was that patient care could be improved by increasing the competence of PCPs in the management of complex diseases by providing access to disease specialists through a case-based learning approach that used technology, which it termed knowledge networks, to connect the PCPs to specialists.

The original model addressed management of hepatitis C in a medically underserved area where half of the population was widely geographically dispersed, making the provision of specialty care challenging. Developers identified 6 characteristics that make a disease appropriate for treatment using the Project ECHO knowledge network model:

- The disease is common;

- Management of the disease is complex;

- Treatment for the disease is evolving;

- The disease has a high societal impact;

- There are serious outcomes if the disease is not treated; and

- Disease management improves outcomes.1

VA ECHO conferences are available to all VA personnel. Staff can subscribe to an e-mail group list to be alerted to conference times and topics. Participants can connect directly to the conference using Microsoft Outlook Lync or Skype (Redmond, WA) and see the slides in real time on their computer as they listen to the presentation. The presentations are recorded, and the slides with audio can be accessed easily on the VA ECHO SharePoint site for download, enabling VA staff to listen to conferences at their convenience (Figure).

VA Cancer ECHO

The impetus to create a series of talks related to cancer care using VA ECHO was the frequent and often time-consuming requests we received from colleagues at other VA sites for information about areas of cancer care, such as survivorship and cancer care coordination. It was felt that presenting cancer care information as a VA ECHO series would make this information available to a large group of providers at one time, making the method more time effective than sharing the information via one-on-one conversations.

The cancer care coordinator originally conceived this as a 3-part, 1-time series to present work done at VACT in the areas of survivorship, psychosocial distress monitoring, and coordination of cancer care using the VA Cancer Care Tracking System, an online tracking tool. Information about the series was disseminated via VA group e-mail lists for oncology providers and via the existing VA ECHO subscriber invitation process. The 3-presentation series garnered positive feedback and had attendance that ranged from 49 to 75 participants (mean, 60). Participants expressed enthusiasm for the format via e-mail and phone feedback directly to the West Haven staff.

Expansion

The success of this original 3-part series led to a trial of an ongoing Cancer Care Conference series (Conference) using VA ECHO. This was a novel use of VA ECHO and was outside its traditional format, which is geared to discussion of individual cases and clinical knowledge. Nevertheless, this new style of communication has been embraced by a wide range of VA cancer care professionals.

One reason we considered expanding the program was that oncology fit the framework of the original Project ECHO knowledge network model. Cancer is common at the VA, which cares for 175,000 patients with cancer annually.2 The management of cancer is complex involving many disciplines working together, and treatments are constantly changing. In addition, cancer has a high societal impact; there are serious outcomes both in terms of patient survival and patient symptom burden. And lastly, outcomes are improved with proactive disease management that is informed by the most current, evidence-based medicine.

The Conference was conceived as a forum for providers across disciplines to share best practices and discuss common challenges in caring for veterans with cancer. We invited participants to submit proposals for presentations related to cancer care initiatives at their VA sites. Potential speakers across all areas of care for veterans with cancer were invited to submit possible topics for the conference. The submissions were reviewed by the moderators in an effort to create a series of talks on a variety of topics across all aspects of care for oncology patients in the VA. This process of effectively crowd-sourcing educational content inspires providers to think more creatively about their practice and quality improvement projects and has sparked an ongoing dialogue about quality initiatives among VA oncology providers across disciplines and geographic locations. As a result, this approach also has enabled participants to learn from colleagues who work at a wide range of rural and urban VA locations throughout the country and to network with colleagues who are working on similar quality initiatives and challenges related to caring for veterans with cancer.

Program

The first Conference talk was in October 2016. It encompassed ten 1-hour talks during the 2016 to 2017 academic year. Speakers were recruited from the VACT West Haven campus and from several other VA sites nationwide. Topics included survivorship, psychosocial distress, palliative care, cancer navigation, and establishing a clinical trials program.

In its first year, the Conference series had 260 unique attendees representing such disciplines as medicine, nursing, social work, pharmacy, psychology, and clinic administration and representing all 21 Veterans Integrated Services Networks (VISNs). Speakers including oncologists, hepatologists, cancer care coordinators, health psychologists, and a research coordinator gave presentations on psychosocial distress screening and issues, cognitive behavioral therapy for cancer pain, cancer navigation, cancer case tracking, VISN-based liver cancer tumor tracker and liver tumor board, starting a VA-based clinical trial, palliative care, and survivorship.

The Conference accounted for 508 continuing medical education (CME) hours, which accounted for one-third of the total CME hours generated by the VACT West Haven VA ECHO program. Highlights of the talks were presented at the 2017 Association of VA Hematology/Oncology annual meeting in Denver, Colorado.

During the second year of the Conference, speakers were recruited to address new American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC) requirements regarding survivorship treatment summaries for a subset of cancer survivors.3 The focus on survivorship was driven by ongoing feedback from participants who were working on initiatives to implement this process at their VA sites and wanted to learn from peers involved in this process throughout the VA system. Several speakers gave talks on implementing survivorship care at their VA and specifically on the use of computerized patient record system templates to create survivorship treatment summaries for veterans in accordance with CoC standards.

Since the first Conference in 2016, the number of unique attendees grew by 20% to 327 in 2018. During its first 2 years, participants have earned a total of 1,095 CME credits through Yale University CME. Conferences are usually broadcast at noon eastern time so that providers can take advantage of sessions during lunch breaks.

Participant Surveys

Attendees were invited to participate in voluntary, anonymous surveys to obtain feedback on and to receive input on topics of interest for future talks. Participants also were asked to comment on resources that they utilized to be updated on practice changes (Table 1).

The Conference has led to increased awareness of other continuing education opportunities available through VA ECHO-Connecticut. Of survey participants, 20% reported that they had attended other VA ECHO conferences.

The survey samples are self-selecting and may not necessarily be representative of the Conference participants or of the VA oncology interdisciplinary team as a whole; however, the relatively large number of survey participants provides some confidence that these survey results can help inform future planning for this and other continuing education opportunities for VA oncology providers.

An additional online survey was designed to elucidate whether participants were incorporating knowledge gained from the Conference in their cancer care practice. Half of the 32 participants strongly agreed with the following statement: “Participation in the VA Cancer Care Conference has added to my knowledge of information relevant to my practice,” and 13 more agreed with the statement for a total of 90.6% of those surveyed responding affirmatively. Only 3 participants neither agreed nor disagreed, and none disagreed with the statement. More than half of the participants reported that they made changes to their practice or plan to make changes as a result of the Conference.

Conculsion

The VA ECHO program established at the VACT West Haven campus in 2012 now offers regular monthly or bimonthly conferences in 9 specialties: pain, liver/hepatitis C, neurology, nephrology, cardiology, diabetes/endocrinology, mental health and addiction, nursing grand rounds, and cancer care. The VACT ECHO program is led by a medical director, and each specialty has a clinical director who conducts sessions and recruits other specialists from their department.

Teleconferencing can provide opportunities for colleagues living in distant locations to connect; share best practices, common goals, and challenges; and initiate ongoing and lasting relationships. The Conference draws the most diverse audience by discipline of all the VA ECHO conferences hosted at VACT (Table 2).

Traditionally, the national VA ECHO program has been a forum for specialists to discuss clinical case presentations for the benefit of primary care providers and to deliver didactics about chronic clinical conditions. Our Cancer Care Management VA ECHO has explored new ground by discussing material that has helped sites set up and enhance cancer care clinics and disseminate best practices for cancer survivorship and other aspects of cancer care. As a result, this conference has attracted and provided a forum for the most diverse audience of staff among VA ECHO clinics, with participation from clinic administrators to social workers to primary care providers to tumor registrars.

Through the creation of the Conference, > 300 individuals who care for veterans with cancer have been provided with a regular forum at which to connect with colleagues, receive updates on new treatment options for their patients, and learn about and share best practices specific to VA oncology patients. The VA ECHO technology creates a resource that can be accessed by all VA staff from their desktop computer. The VA ECHO SharePoint saves the slides of the Conference presentations both with and without audio to enable staff who can’t participate in real time to access the information at their convenience.

The Conference has facilitated networking among VA oncology providers who have common interests. Conference participants also have participated in other VA ECHO conferences in disciplines beyond oncology. Participants in the Conference also are encouraged to participate as speakers by presenting quality improvement initiatives at their VA site. This novel approach to generating content for this educational series has led to a dynamic interchange of ideas and increased networking among VA providers related to their practice and quality improvement initiatives at their VA sites. The Conference provides a regular forum for VA staff across a wide range of disciplines to share personal experiences, successes, and frustrations and to get feedback from colleagues.

The Conference combines a structured approach to presenting VA-specific educational content related to cancer care and multiple mechanisms that encourage staff to participate in an ongoing dialogue related to quality initiatives both on the phone during the Conference, online using Outlook LYNC or Skype to ask questions during the Conference, and during conversations on group e-mail. The Conference promotes staff engagement at little or no extra cost to the VA. For more information about the VA ECHO Cancer Care Conference or to submit a presentation for consideration for a future session, please contact julie.beck@va.gov or pradeep.mutalik@va.gov.

1. Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):154-160.

2. Hematology and oncology federal health care data trends. Fed Pract. 2017;33(suppl 5):S12-S15.

3. American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient Centered Care, 2016 Edition. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/standards. Accessed March 14, 2018.

A telementoring program based on the Specialty Care Access Network Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes model shared information about cancer care across VA health Care systems.

A telementoring program based on the Specialty Care Access Network Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes model shared information about cancer care across VA health Care systems.

In 2016, the Cancer Care Coordinator at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Healthcare System (VACT) in West Haven partnered with the VA New England Healthcare System to use its telementoring program. The VA Specialty Care Access Network Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (VA ECHO) was used to present a series of educational conferences on cancer care. This article describes our experience implementing the program and reviews participant feedback gathered from voluntary surveys.

Background

In 2011, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Office of Healthcare Transformation launched VA ECHO, a telementoring program for primary care providers (PCPs) and patient-aligned care team staff. VACT was selected as 1 of 7 hub sites across the US. The VA ECHO system uses video and online technology to provide PCPs with case-based specialist consultation and didactic education. The system enables providers at any VA location to participate in online and telephone conferences in real time. The presentations are recorded and made available online to VA providers through a secure site.

VA ECHO is based on the highly successful Project ECHO model established by Sanjeev Arora and the University of New Mexico in 2007.1 The rationale for Project ECHO was that patient care could be improved by increasing the competence of PCPs in the management of complex diseases by providing access to disease specialists through a case-based learning approach that used technology, which it termed knowledge networks, to connect the PCPs to specialists.

The original model addressed management of hepatitis C in a medically underserved area where half of the population was widely geographically dispersed, making the provision of specialty care challenging. Developers identified 6 characteristics that make a disease appropriate for treatment using the Project ECHO knowledge network model:

- The disease is common;

- Management of the disease is complex;

- Treatment for the disease is evolving;

- The disease has a high societal impact;

- There are serious outcomes if the disease is not treated; and

- Disease management improves outcomes.1

VA ECHO conferences are available to all VA personnel. Staff can subscribe to an e-mail group list to be alerted to conference times and topics. Participants can connect directly to the conference using Microsoft Outlook Lync or Skype (Redmond, WA) and see the slides in real time on their computer as they listen to the presentation. The presentations are recorded, and the slides with audio can be accessed easily on the VA ECHO SharePoint site for download, enabling VA staff to listen to conferences at their convenience (Figure).

VA Cancer ECHO

The impetus to create a series of talks related to cancer care using VA ECHO was the frequent and often time-consuming requests we received from colleagues at other VA sites for information about areas of cancer care, such as survivorship and cancer care coordination. It was felt that presenting cancer care information as a VA ECHO series would make this information available to a large group of providers at one time, making the method more time effective than sharing the information via one-on-one conversations.

The cancer care coordinator originally conceived this as a 3-part, 1-time series to present work done at VACT in the areas of survivorship, psychosocial distress monitoring, and coordination of cancer care using the VA Cancer Care Tracking System, an online tracking tool. Information about the series was disseminated via VA group e-mail lists for oncology providers and via the existing VA ECHO subscriber invitation process. The 3-presentation series garnered positive feedback and had attendance that ranged from 49 to 75 participants (mean, 60). Participants expressed enthusiasm for the format via e-mail and phone feedback directly to the West Haven staff.

Expansion

The success of this original 3-part series led to a trial of an ongoing Cancer Care Conference series (Conference) using VA ECHO. This was a novel use of VA ECHO and was outside its traditional format, which is geared to discussion of individual cases and clinical knowledge. Nevertheless, this new style of communication has been embraced by a wide range of VA cancer care professionals.

One reason we considered expanding the program was that oncology fit the framework of the original Project ECHO knowledge network model. Cancer is common at the VA, which cares for 175,000 patients with cancer annually.2 The management of cancer is complex involving many disciplines working together, and treatments are constantly changing. In addition, cancer has a high societal impact; there are serious outcomes both in terms of patient survival and patient symptom burden. And lastly, outcomes are improved with proactive disease management that is informed by the most current, evidence-based medicine.

The Conference was conceived as a forum for providers across disciplines to share best practices and discuss common challenges in caring for veterans with cancer. We invited participants to submit proposals for presentations related to cancer care initiatives at their VA sites. Potential speakers across all areas of care for veterans with cancer were invited to submit possible topics for the conference. The submissions were reviewed by the moderators in an effort to create a series of talks on a variety of topics across all aspects of care for oncology patients in the VA. This process of effectively crowd-sourcing educational content inspires providers to think more creatively about their practice and quality improvement projects and has sparked an ongoing dialogue about quality initiatives among VA oncology providers across disciplines and geographic locations. As a result, this approach also has enabled participants to learn from colleagues who work at a wide range of rural and urban VA locations throughout the country and to network with colleagues who are working on similar quality initiatives and challenges related to caring for veterans with cancer.

Program

The first Conference talk was in October 2016. It encompassed ten 1-hour talks during the 2016 to 2017 academic year. Speakers were recruited from the VACT West Haven campus and from several other VA sites nationwide. Topics included survivorship, psychosocial distress, palliative care, cancer navigation, and establishing a clinical trials program.