User login

Practicing solo and feeling grateful – despite COVID-19

I know that the world has gone upside down. It’s a nightmare, and people are filled with fear, and death is everywhere. In my little bubble of a world, however, I’ve been doing well.

I can’t lose my job, because I am my job. I’m a solo practitioner and have been for more than a decade. The restrictions to stay at home have not affected me, because I have a home office. Besides, I’m an introvert and see myself as a bit of a recluse, so the social distancing hasn’t been stressful. Conducting appointments by phone rather than face to face hasn’t undermined my work, since I can do everything that I do in my office over the phone. But I do it now in sweats and at my desk in my bedroom more often than not. I am prepared for a decrease in income as people lose their jobs, but that hasn’t happened yet. There are still people out there who are very motivated to come off their medications holistically. No rest for the wicked, as the saying goes.

On an emotional level, I feel calm because I’m not attached to material things, though I like them when they’re here. My children and friends have remained healthy, so I am grateful for that. I feel grounded in my belief that life goes on one way or another, and I trust in God to direct me wherever I need to go. Socially, I’ve been forced to be less lazy and cook more at home. As a result: less salt, MSG, and greasy food. I’ve spent a lot less on restaurants this past month and am eating less since I have to eat whatever I cook.

Can a person be more pandemic proof? I was joking with a friend about how pandemic-friendly my lifestyle is: spiritually, mentally, emotionally, physically, and socially. Oh, did I forget to mention the year supply of supplements in my office closet? They were for my patients, but those whole food green and red powders may come in handy, just in case.

So, that is how things are going for me. Please don’t hate me for not freaking out. When I read the news, I feel very sad for people who are suffering. I get angry at the politicians who can’t get their egos out of the way. But, I look at the sunshine outside my window, and I feel grateful that, at least in my case, I am not adding to the burden of suffering in the world. Not yet, anyway. I will keep trying to do the little bit that I do to help others for as long as I can.

Dr. Lee specializes in integrative and holistic psychiatry and has a private practice in Gaithersburg, Md. She has no disclosures.

I know that the world has gone upside down. It’s a nightmare, and people are filled with fear, and death is everywhere. In my little bubble of a world, however, I’ve been doing well.

I can’t lose my job, because I am my job. I’m a solo practitioner and have been for more than a decade. The restrictions to stay at home have not affected me, because I have a home office. Besides, I’m an introvert and see myself as a bit of a recluse, so the social distancing hasn’t been stressful. Conducting appointments by phone rather than face to face hasn’t undermined my work, since I can do everything that I do in my office over the phone. But I do it now in sweats and at my desk in my bedroom more often than not. I am prepared for a decrease in income as people lose their jobs, but that hasn’t happened yet. There are still people out there who are very motivated to come off their medications holistically. No rest for the wicked, as the saying goes.

On an emotional level, I feel calm because I’m not attached to material things, though I like them when they’re here. My children and friends have remained healthy, so I am grateful for that. I feel grounded in my belief that life goes on one way or another, and I trust in God to direct me wherever I need to go. Socially, I’ve been forced to be less lazy and cook more at home. As a result: less salt, MSG, and greasy food. I’ve spent a lot less on restaurants this past month and am eating less since I have to eat whatever I cook.

Can a person be more pandemic proof? I was joking with a friend about how pandemic-friendly my lifestyle is: spiritually, mentally, emotionally, physically, and socially. Oh, did I forget to mention the year supply of supplements in my office closet? They were for my patients, but those whole food green and red powders may come in handy, just in case.

So, that is how things are going for me. Please don’t hate me for not freaking out. When I read the news, I feel very sad for people who are suffering. I get angry at the politicians who can’t get their egos out of the way. But, I look at the sunshine outside my window, and I feel grateful that, at least in my case, I am not adding to the burden of suffering in the world. Not yet, anyway. I will keep trying to do the little bit that I do to help others for as long as I can.

Dr. Lee specializes in integrative and holistic psychiatry and has a private practice in Gaithersburg, Md. She has no disclosures.

I know that the world has gone upside down. It’s a nightmare, and people are filled with fear, and death is everywhere. In my little bubble of a world, however, I’ve been doing well.

I can’t lose my job, because I am my job. I’m a solo practitioner and have been for more than a decade. The restrictions to stay at home have not affected me, because I have a home office. Besides, I’m an introvert and see myself as a bit of a recluse, so the social distancing hasn’t been stressful. Conducting appointments by phone rather than face to face hasn’t undermined my work, since I can do everything that I do in my office over the phone. But I do it now in sweats and at my desk in my bedroom more often than not. I am prepared for a decrease in income as people lose their jobs, but that hasn’t happened yet. There are still people out there who are very motivated to come off their medications holistically. No rest for the wicked, as the saying goes.

On an emotional level, I feel calm because I’m not attached to material things, though I like them when they’re here. My children and friends have remained healthy, so I am grateful for that. I feel grounded in my belief that life goes on one way or another, and I trust in God to direct me wherever I need to go. Socially, I’ve been forced to be less lazy and cook more at home. As a result: less salt, MSG, and greasy food. I’ve spent a lot less on restaurants this past month and am eating less since I have to eat whatever I cook.

Can a person be more pandemic proof? I was joking with a friend about how pandemic-friendly my lifestyle is: spiritually, mentally, emotionally, physically, and socially. Oh, did I forget to mention the year supply of supplements in my office closet? They were for my patients, but those whole food green and red powders may come in handy, just in case.

So, that is how things are going for me. Please don’t hate me for not freaking out. When I read the news, I feel very sad for people who are suffering. I get angry at the politicians who can’t get their egos out of the way. But, I look at the sunshine outside my window, and I feel grateful that, at least in my case, I am not adding to the burden of suffering in the world. Not yet, anyway. I will keep trying to do the little bit that I do to help others for as long as I can.

Dr. Lee specializes in integrative and holistic psychiatry and has a private practice in Gaithersburg, Md. She has no disclosures.

Which of the changes that coronavirus has forced upon us will remain?

Eventually this strange Twilight Zone world of coronavirus will end and life will return to normal.

But obviously it won’t be the same, and like everyone else I wonder what will be different.

Telemedicine is one obvious change in my world, though I don’t know how much yet (granted, no one else does, either). I’m seeing a handful of people that way, limited to established patients, where we’re discussing chronic issues or reviewing recent test results.

If I have to see a new patient or an established one with an urgent issue, I’m still willing to meet them at my office (wearing masks and washing hands frequently). In neurology, a lot still depends on a decent exam. It’s pretty hard to check reflexes, sensory modalities, and muscle tone over the phone. If you think a malpractice attorney is going to give you a pass because you missed something by not examining a patient because of coronavirus ... think again.

I’m not sure how the whole telemedicine thing will play out after the dust settles, at least not at my little practice. I’m currently seeing patients by FaceTime and Skype, neither of which is considered HIPAA compliant. The requirement has been waived during the crisis to make sure people can still see doctors, but I don’t see it lasting beyond that. Privacy will always be a central concern in medicine.

When they declare the pandemic over and say I can’t use FaceTime or Skype anymore, that will likely end my use of such. While there are HIPAA-compliant telemedicine services out there, in a small practice I don’t have the time or money to invest in them.

I also wonder how outcomes will change. I suspect the research-minded will be analyzing 2019 vs. 2020 data for years to come, trying to see if a sudden increase in telemedicine led to better or worse clinical outcomes. I’ll be curious to see what they find and how it breaks down by disease and specialty.

How will work change? Right now my staff of three (including me) are all working separately from home, handling phone calls as if it were another office day. In today’s era that’s easy to set up, and we’re used to the drill from when I’m out of town.

Maybe in the future, on lighter days, I’ll do this more often, and have my staff work from home (on typically busy days I’ll still need them to check patients in and out, fax things, file charts, and do all the other things they do to keep the practice running). The marked decrease in air pollution is certainly noticeable and good for all. When the year is over I’d like to see how non-coronavirus respiratory issues changed between 2019 and 2020.

Other businesses will be looking at that, too, with an increase in telecommuting. Why pay for a large office space when a lot can be done over the Internet? It saves rent, gas, and driving time. How it will affect us, as a socially-dependent species, I have no idea.

It’s the same with grocery delivery. While most of us will likely continue to shop at stores, many will stay with the ease of delivery services after this. It may cost more, but it certainly saves time.

There will be social changes, although how long they’ll last is anyone’s guess. Grocery baggers, stockers, and delivery staff, often seen as lower-level occupations, are now considered part of critical infrastructure in keeping people supplied with food and other necessities, as well as preventing fights from breaking out in the toilet paper and hand-sanitizer aisles.

I’d like to think that, in a country divided, the need to work together will help bring people of different opinions together again, but from the way things look I don’t see that happening, which is sad because viruses don’t discriminate, so we shouldn’t either in fighting them.

Like with other challenges that we face, big and little, I can only hope that we’ll learn something from this and have a better world after it’s over. Only time will tell.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

Eventually this strange Twilight Zone world of coronavirus will end and life will return to normal.

But obviously it won’t be the same, and like everyone else I wonder what will be different.

Telemedicine is one obvious change in my world, though I don’t know how much yet (granted, no one else does, either). I’m seeing a handful of people that way, limited to established patients, where we’re discussing chronic issues or reviewing recent test results.

If I have to see a new patient or an established one with an urgent issue, I’m still willing to meet them at my office (wearing masks and washing hands frequently). In neurology, a lot still depends on a decent exam. It’s pretty hard to check reflexes, sensory modalities, and muscle tone over the phone. If you think a malpractice attorney is going to give you a pass because you missed something by not examining a patient because of coronavirus ... think again.

I’m not sure how the whole telemedicine thing will play out after the dust settles, at least not at my little practice. I’m currently seeing patients by FaceTime and Skype, neither of which is considered HIPAA compliant. The requirement has been waived during the crisis to make sure people can still see doctors, but I don’t see it lasting beyond that. Privacy will always be a central concern in medicine.

When they declare the pandemic over and say I can’t use FaceTime or Skype anymore, that will likely end my use of such. While there are HIPAA-compliant telemedicine services out there, in a small practice I don’t have the time or money to invest in them.

I also wonder how outcomes will change. I suspect the research-minded will be analyzing 2019 vs. 2020 data for years to come, trying to see if a sudden increase in telemedicine led to better or worse clinical outcomes. I’ll be curious to see what they find and how it breaks down by disease and specialty.

How will work change? Right now my staff of three (including me) are all working separately from home, handling phone calls as if it were another office day. In today’s era that’s easy to set up, and we’re used to the drill from when I’m out of town.

Maybe in the future, on lighter days, I’ll do this more often, and have my staff work from home (on typically busy days I’ll still need them to check patients in and out, fax things, file charts, and do all the other things they do to keep the practice running). The marked decrease in air pollution is certainly noticeable and good for all. When the year is over I’d like to see how non-coronavirus respiratory issues changed between 2019 and 2020.

Other businesses will be looking at that, too, with an increase in telecommuting. Why pay for a large office space when a lot can be done over the Internet? It saves rent, gas, and driving time. How it will affect us, as a socially-dependent species, I have no idea.

It’s the same with grocery delivery. While most of us will likely continue to shop at stores, many will stay with the ease of delivery services after this. It may cost more, but it certainly saves time.

There will be social changes, although how long they’ll last is anyone’s guess. Grocery baggers, stockers, and delivery staff, often seen as lower-level occupations, are now considered part of critical infrastructure in keeping people supplied with food and other necessities, as well as preventing fights from breaking out in the toilet paper and hand-sanitizer aisles.

I’d like to think that, in a country divided, the need to work together will help bring people of different opinions together again, but from the way things look I don’t see that happening, which is sad because viruses don’t discriminate, so we shouldn’t either in fighting them.

Like with other challenges that we face, big and little, I can only hope that we’ll learn something from this and have a better world after it’s over. Only time will tell.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

Eventually this strange Twilight Zone world of coronavirus will end and life will return to normal.

But obviously it won’t be the same, and like everyone else I wonder what will be different.

Telemedicine is one obvious change in my world, though I don’t know how much yet (granted, no one else does, either). I’m seeing a handful of people that way, limited to established patients, where we’re discussing chronic issues or reviewing recent test results.

If I have to see a new patient or an established one with an urgent issue, I’m still willing to meet them at my office (wearing masks and washing hands frequently). In neurology, a lot still depends on a decent exam. It’s pretty hard to check reflexes, sensory modalities, and muscle tone over the phone. If you think a malpractice attorney is going to give you a pass because you missed something by not examining a patient because of coronavirus ... think again.

I’m not sure how the whole telemedicine thing will play out after the dust settles, at least not at my little practice. I’m currently seeing patients by FaceTime and Skype, neither of which is considered HIPAA compliant. The requirement has been waived during the crisis to make sure people can still see doctors, but I don’t see it lasting beyond that. Privacy will always be a central concern in medicine.

When they declare the pandemic over and say I can’t use FaceTime or Skype anymore, that will likely end my use of such. While there are HIPAA-compliant telemedicine services out there, in a small practice I don’t have the time or money to invest in them.

I also wonder how outcomes will change. I suspect the research-minded will be analyzing 2019 vs. 2020 data for years to come, trying to see if a sudden increase in telemedicine led to better or worse clinical outcomes. I’ll be curious to see what they find and how it breaks down by disease and specialty.

How will work change? Right now my staff of three (including me) are all working separately from home, handling phone calls as if it were another office day. In today’s era that’s easy to set up, and we’re used to the drill from when I’m out of town.

Maybe in the future, on lighter days, I’ll do this more often, and have my staff work from home (on typically busy days I’ll still need them to check patients in and out, fax things, file charts, and do all the other things they do to keep the practice running). The marked decrease in air pollution is certainly noticeable and good for all. When the year is over I’d like to see how non-coronavirus respiratory issues changed between 2019 and 2020.

Other businesses will be looking at that, too, with an increase in telecommuting. Why pay for a large office space when a lot can be done over the Internet? It saves rent, gas, and driving time. How it will affect us, as a socially-dependent species, I have no idea.

It’s the same with grocery delivery. While most of us will likely continue to shop at stores, many will stay with the ease of delivery services after this. It may cost more, but it certainly saves time.

There will be social changes, although how long they’ll last is anyone’s guess. Grocery baggers, stockers, and delivery staff, often seen as lower-level occupations, are now considered part of critical infrastructure in keeping people supplied with food and other necessities, as well as preventing fights from breaking out in the toilet paper and hand-sanitizer aisles.

I’d like to think that, in a country divided, the need to work together will help bring people of different opinions together again, but from the way things look I don’t see that happening, which is sad because viruses don’t discriminate, so we shouldn’t either in fighting them.

Like with other challenges that we face, big and little, I can only hope that we’ll learn something from this and have a better world after it’s over. Only time will tell.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

COVID-19 CRISIS: We must care for ourselves as we care for others

“I do not shrink from this responsibility, I welcome it.” —John F. Kennedy, inaugural address

COVID-19 has changed our world. Social distancing is now the norm and flattening the curve is our motto. Family physicians’ place on the front line of medicine is more important now than it has ever been.

In the Pennsylvania community in which we work, the first person to don protective gear and sample patients for viral testing in a rapidly organized COVID-19 testing site was John Russell, MD, a family physician. When I asked him about his experience, Dr. Russell said, “No one became a fireman to get cats out of trees ... it was to fight fires. As doctors, this is the same idea ... this is a chance to help fight the fires in our community.”

And, of course, it is primary care providers—family physicians, internists, pediatricians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and nurses—who day in and day out are putting aside their own fears, while dealing with those of their family, to come to work with a sense of purpose and courage.

The military uses the term “operational tempo” to describe the speed and intensity of actions relative to the speed and intensity of unfolding events in the operational environment. Family physicians are being asked to work at an increased speed in unfamiliar terrain as our environments change by the hour. The challenge is to answer the call—and take care of ourselves—in unprecedented ways. We often use anticipatory guidance with our patients to help prepare them for the challenges they will face. So, too, must we anticipate the things we will need to be attentive to in the coming months in order to sustain the effort that will be required of us.

With this in mind, we would be wise to consider developing plans in 3 domains: physical, mental, and social.

Physical. With gyms closed and restaurants limiting their offerings to take-out, this is an opportune time to create an exercise regimen at home and experiment with healthy meal options. YouTube videos abound for workouts of every length. And of course, you can simply take a daily walk, go for a run, or take a bike ride. Similarly, good choices can be made with take-out and the foods we prepare at home.

Continue to: Mentally...

Mentally we need the discipline to take breaks, delegate when necessary, and use downtime to clear our minds. Need another option? Consider meditation. Google “best meditation apps” and take your pick.

Social distancing doesn’t have to mean emotional isolation; technology allows us to connect with others through messaging and face-to-face video. We need to remember to regularly check in with those we care about; few things in life are as affirming as the connections with those who are close to us: family, co-workers, and patients.

Out of crisis comes opportunity. Should we be quarantined, we can remind ourselves that Sir Isaac Newton, while in quarantine during the bubonic plague, laid the foundation for classical physics, composed theories on light and optics, and penned his first draft of the law of gravity.1

Life carries on, amidst the pandemic. Even though the current focus is on the COVID-19 crisis, our many needs, joys, and challenges as human beings remain. Today, someone will find out she is pregnant; someone else will be diagnosed with cancer, or plan a wedding, or attend the funeral of a loved one. We, as family physicians, have the training to lead with courage and empathy. We have the expertise gained through years of helping patients though diverse physical and emotional challenges.

We will continue to listen to our patients’ stories, diagnose and treat their diseases, and take steps to bring a sense of calm to the chaos around us. We need to be mindful of our own mindset, because we have a choice. As the psychologist Victor Frankl said in 1946, after being liberated from the concentration camps, “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”2

1. Brockell G. During a pandemic, Isaac Newton had to work from home, too. He used the time wisely. The Washington Post. March 12, 2020. 2. Frankl VE. Man’s Search for Meaning. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2006.

“I do not shrink from this responsibility, I welcome it.” —John F. Kennedy, inaugural address

COVID-19 has changed our world. Social distancing is now the norm and flattening the curve is our motto. Family physicians’ place on the front line of medicine is more important now than it has ever been.

In the Pennsylvania community in which we work, the first person to don protective gear and sample patients for viral testing in a rapidly organized COVID-19 testing site was John Russell, MD, a family physician. When I asked him about his experience, Dr. Russell said, “No one became a fireman to get cats out of trees ... it was to fight fires. As doctors, this is the same idea ... this is a chance to help fight the fires in our community.”

And, of course, it is primary care providers—family physicians, internists, pediatricians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and nurses—who day in and day out are putting aside their own fears, while dealing with those of their family, to come to work with a sense of purpose and courage.

The military uses the term “operational tempo” to describe the speed and intensity of actions relative to the speed and intensity of unfolding events in the operational environment. Family physicians are being asked to work at an increased speed in unfamiliar terrain as our environments change by the hour. The challenge is to answer the call—and take care of ourselves—in unprecedented ways. We often use anticipatory guidance with our patients to help prepare them for the challenges they will face. So, too, must we anticipate the things we will need to be attentive to in the coming months in order to sustain the effort that will be required of us.

With this in mind, we would be wise to consider developing plans in 3 domains: physical, mental, and social.

Physical. With gyms closed and restaurants limiting their offerings to take-out, this is an opportune time to create an exercise regimen at home and experiment with healthy meal options. YouTube videos abound for workouts of every length. And of course, you can simply take a daily walk, go for a run, or take a bike ride. Similarly, good choices can be made with take-out and the foods we prepare at home.

Continue to: Mentally...

Mentally we need the discipline to take breaks, delegate when necessary, and use downtime to clear our minds. Need another option? Consider meditation. Google “best meditation apps” and take your pick.

Social distancing doesn’t have to mean emotional isolation; technology allows us to connect with others through messaging and face-to-face video. We need to remember to regularly check in with those we care about; few things in life are as affirming as the connections with those who are close to us: family, co-workers, and patients.

Out of crisis comes opportunity. Should we be quarantined, we can remind ourselves that Sir Isaac Newton, while in quarantine during the bubonic plague, laid the foundation for classical physics, composed theories on light and optics, and penned his first draft of the law of gravity.1

Life carries on, amidst the pandemic. Even though the current focus is on the COVID-19 crisis, our many needs, joys, and challenges as human beings remain. Today, someone will find out she is pregnant; someone else will be diagnosed with cancer, or plan a wedding, or attend the funeral of a loved one. We, as family physicians, have the training to lead with courage and empathy. We have the expertise gained through years of helping patients though diverse physical and emotional challenges.

We will continue to listen to our patients’ stories, diagnose and treat their diseases, and take steps to bring a sense of calm to the chaos around us. We need to be mindful of our own mindset, because we have a choice. As the psychologist Victor Frankl said in 1946, after being liberated from the concentration camps, “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”2

“I do not shrink from this responsibility, I welcome it.” —John F. Kennedy, inaugural address

COVID-19 has changed our world. Social distancing is now the norm and flattening the curve is our motto. Family physicians’ place on the front line of medicine is more important now than it has ever been.

In the Pennsylvania community in which we work, the first person to don protective gear and sample patients for viral testing in a rapidly organized COVID-19 testing site was John Russell, MD, a family physician. When I asked him about his experience, Dr. Russell said, “No one became a fireman to get cats out of trees ... it was to fight fires. As doctors, this is the same idea ... this is a chance to help fight the fires in our community.”

And, of course, it is primary care providers—family physicians, internists, pediatricians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and nurses—who day in and day out are putting aside their own fears, while dealing with those of their family, to come to work with a sense of purpose and courage.

The military uses the term “operational tempo” to describe the speed and intensity of actions relative to the speed and intensity of unfolding events in the operational environment. Family physicians are being asked to work at an increased speed in unfamiliar terrain as our environments change by the hour. The challenge is to answer the call—and take care of ourselves—in unprecedented ways. We often use anticipatory guidance with our patients to help prepare them for the challenges they will face. So, too, must we anticipate the things we will need to be attentive to in the coming months in order to sustain the effort that will be required of us.

With this in mind, we would be wise to consider developing plans in 3 domains: physical, mental, and social.

Physical. With gyms closed and restaurants limiting their offerings to take-out, this is an opportune time to create an exercise regimen at home and experiment with healthy meal options. YouTube videos abound for workouts of every length. And of course, you can simply take a daily walk, go for a run, or take a bike ride. Similarly, good choices can be made with take-out and the foods we prepare at home.

Continue to: Mentally...

Mentally we need the discipline to take breaks, delegate when necessary, and use downtime to clear our minds. Need another option? Consider meditation. Google “best meditation apps” and take your pick.

Social distancing doesn’t have to mean emotional isolation; technology allows us to connect with others through messaging and face-to-face video. We need to remember to regularly check in with those we care about; few things in life are as affirming as the connections with those who are close to us: family, co-workers, and patients.

Out of crisis comes opportunity. Should we be quarantined, we can remind ourselves that Sir Isaac Newton, while in quarantine during the bubonic plague, laid the foundation for classical physics, composed theories on light and optics, and penned his first draft of the law of gravity.1

Life carries on, amidst the pandemic. Even though the current focus is on the COVID-19 crisis, our many needs, joys, and challenges as human beings remain. Today, someone will find out she is pregnant; someone else will be diagnosed with cancer, or plan a wedding, or attend the funeral of a loved one. We, as family physicians, have the training to lead with courage and empathy. We have the expertise gained through years of helping patients though diverse physical and emotional challenges.

We will continue to listen to our patients’ stories, diagnose and treat their diseases, and take steps to bring a sense of calm to the chaos around us. We need to be mindful of our own mindset, because we have a choice. As the psychologist Victor Frankl said in 1946, after being liberated from the concentration camps, “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”2

1. Brockell G. During a pandemic, Isaac Newton had to work from home, too. He used the time wisely. The Washington Post. March 12, 2020. 2. Frankl VE. Man’s Search for Meaning. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2006.

1. Brockell G. During a pandemic, Isaac Newton had to work from home, too. He used the time wisely. The Washington Post. March 12, 2020. 2. Frankl VE. Man’s Search for Meaning. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2006.

Red painful nodules in a hospitalized patient

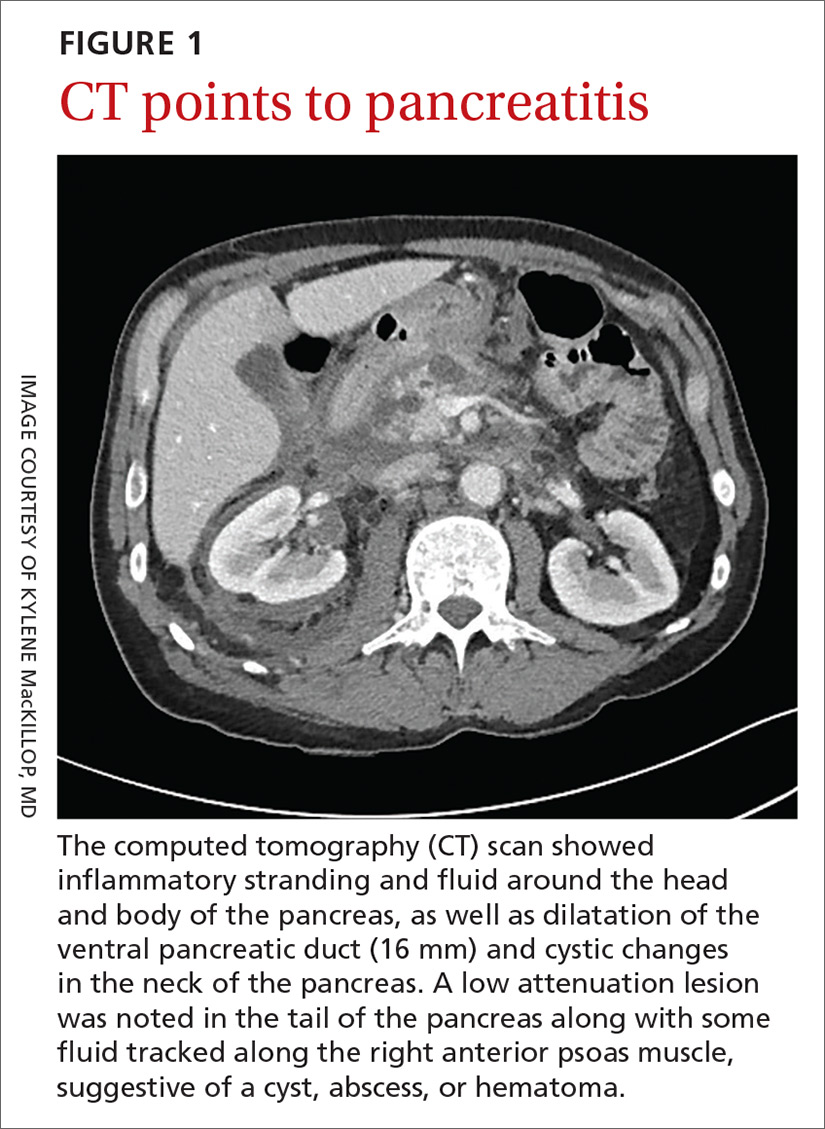

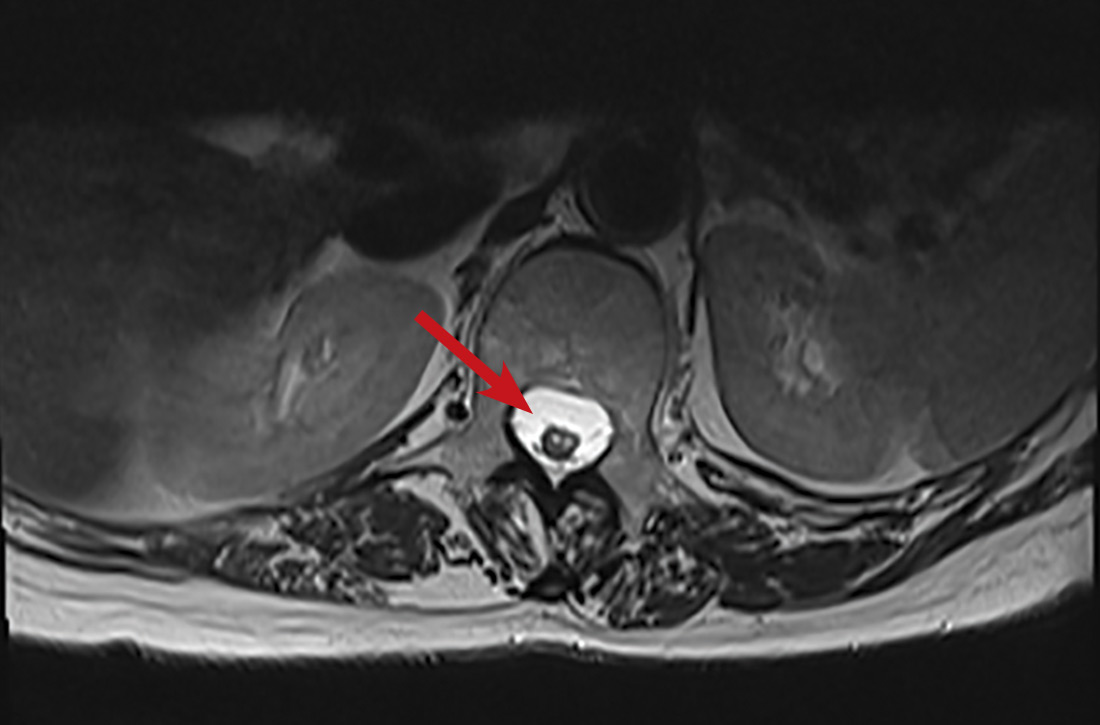

A 58-year-old white man with a history of alcoholism presented to the emergency department with epigastric and right upper quadrant pain radiating to the back, as well as emesis and anorexia. An elevated lipase of 16,609 U/L (reference range, 31–186 U/L) and pathognomonic abdominal computed tomography (CT) findings (FIGURE 1) led to the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, for which he was admitted.

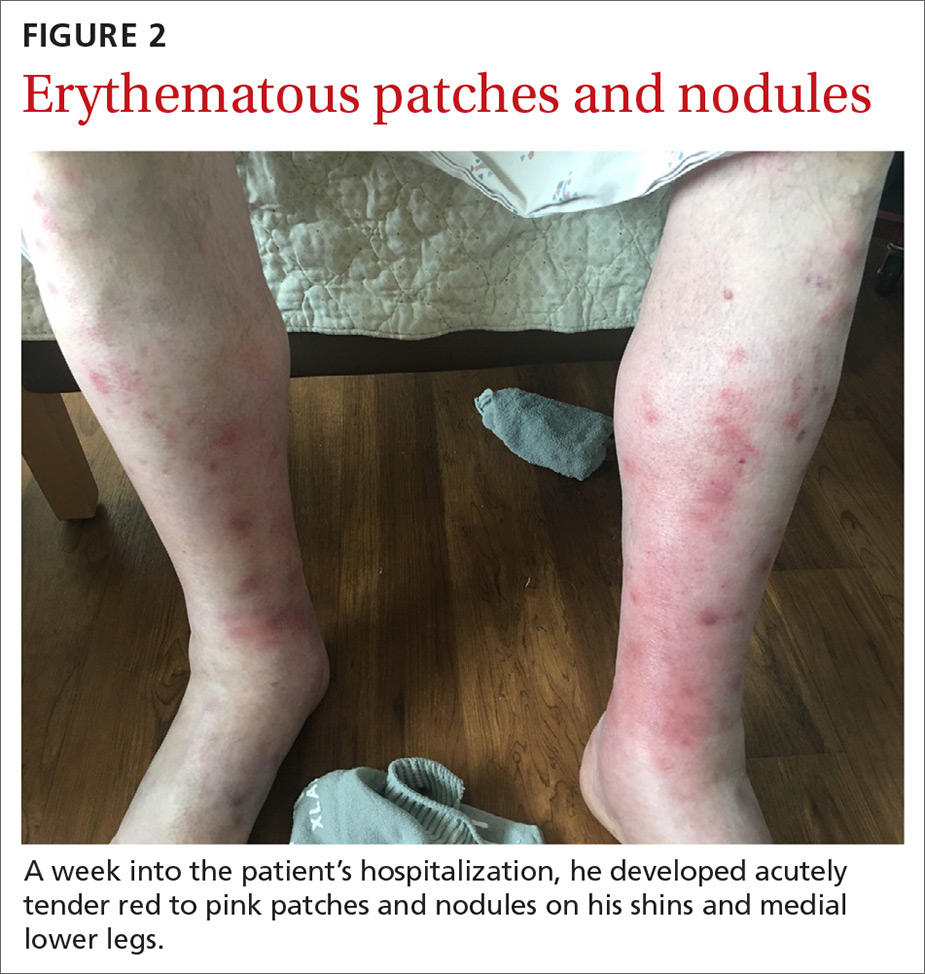

Fluid resuscitation and pain management were implemented, and over 3 days his diet was advanced from NPO to clear fluids to a full diet. On the sixth day of hospitalization, the patient developed increasing abdominal pain and worsening leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 16.6–22 K/mcL [reference range, 4.5–11 K/mcL]). Repeat CT and blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was started on intravenous meropenem 1 g every 8 hours for presumed necrotizing pancreatitis. The next day he developed acutely tender red to pink patches and nodules on his shins and medial lower legs (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pancreatic panniculitis

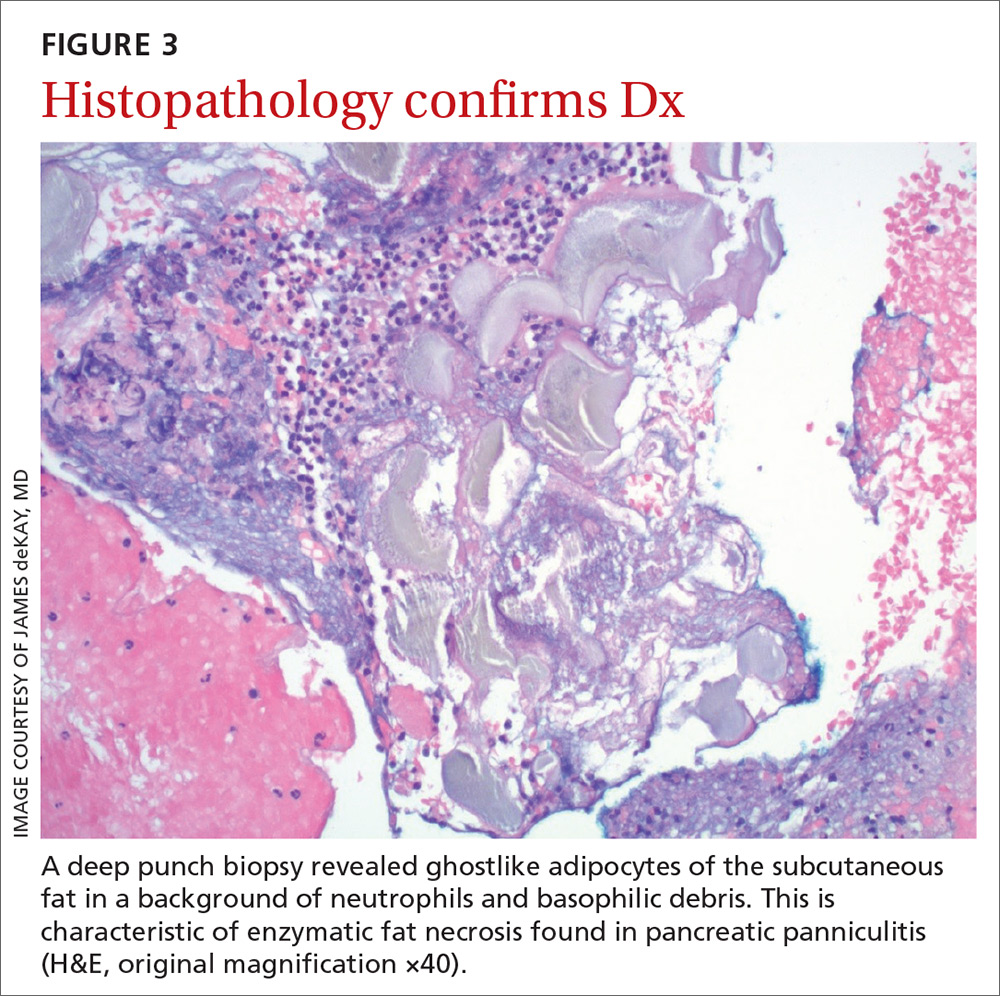

It’s theorized that the systemic release of trypsin from pancreatic cell destruction causes increased capillary permeability and subsequent escape of lipase from the circulation into the subcutaneous fat. This causes fat necrosis, saponification, and inflammation.3,4 Pancreatic panniculitis is demonstrated histologically as hollowed-out adipocytes with granular basophilic cytoplasm and displaced or absent nuclei—aptly named “ghostlike” adipocytes.3-6

Painful, erythematous nodules most commonly present on the distal lower extremities. Nodules may be found over the shins, posterior calves, and periarticular skin. Rarely, nodules may occur on the buttocks, abdomen, or intramedullary bone.7 In severe cases, nodules spontaneously may ulcerate and drain an oily brown, viscous material formed from necrotic adipocytes.1

Timing of the eruption of skin lesions is varied and may even precede abdominal pain. Lesions can involute and regress several weeks after the underlying etiology improves. With pancreatic carcinoma, there is a greater likelihood of persistence, atypical locations of involvement, ulcerations, and recurrences.7

The histologic features of pancreatic panniculitis and the assessment of the subcutaneous fat are paramount in diagnosis. A deep punch biopsy or incisional biopsy is necessary to reliably reach the depth of the subcutaneous tissue. In our patient, a deep punch biopsy from the lateral calf was performed at the suggestion of Dermatology, and histopathology revealed necrosis of fat lobules with calcium soap around necrotic lipocytes, consistent with pancreatic panniculitis (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

The differential diagnosis was broad due to the confounding factors of recent antibiotic use and worsening pancreatitis.

Cellulitis may present as a red patch and is common on the lower legs; it often is associated with skin pathogens including Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. Usually, symptoms are unilateral and associated with warmth to the touch, expanding borders, leukocytosis, and systemic symptoms.

Vasculitis, which is an inflammation of various sized vessels through immunologic or infectious processes, often manifests on the lower legs. The characteristic sign of small vessel vasculitis is nonblanching purpura or petechiae. There often is a preceding illness or medication that triggers immunoglobulin proliferation and off-target inflammation of the vessels. Associated symptoms include pain and pruritus.

Drug eruptions may present as red patches on the skin. Often the patches are scaly and red and have more widespread distribution than the lower legs. A history of exposure is important, but common inciting drugs include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that may be used only occasionally and are challenging to elicit in the history. Our patient did have known drug changes (ie, the introduction of meropenem) while hospitalized, but the morphology was not consistent with this diagnosis.

Treatment is directed to underlying disease

Treatment of pancreatic panniculitis primarily is supportive and directed toward treating the underlying pancreatic disease. Depending upon the underlying pancreatic diagnosis, surgical correction of anatomic or ductal anomalies or pseudocysts may lead to resolution of panniculitis.3,7,8

Continue to: In this case

In this case, our patient had already received fluid resuscitation and pain management, and his diet had been advanced. In addition, his antibiotics were changed to exclude drug eruption as a cause. Over the course of a week, our patient saw a reduction in his pain level and an improvement in the appearance of his legs (FIGURE 4).

His pancreatitis, however, continued to persist and resist increases in his diet. He ultimately required transfer to a tertiary care center for consideration of interventional options including stenting. The patient ultimately recovered, after stenting of the main pancreatic duct, and was discharged home.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, 6 East Chestnut Street, Augusta, ME 04330; Jonathan.Karnes@mainegeneral.org

1. Madarasingha NP, Satgurunathan K, Fernando R. Pancreatic panniculitis: a rare form of panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

2. Haber RM, Assaad DM. Panniculitis associated with a pancreas divisum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 pt 2):331-334.

3. Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

4. Rongioletti F, Caputo V. Pancreatic panniculitis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148:419-425.

5. Förström TL, Winkelmann RK. Acute, generalized panniculitis with amylase and lipase in skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:497-502.

6. Hughes SH, Apisarnthanarax P, Mullins F. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:506-510.

7. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

8. Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, et al. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chro nic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1835-1837.

A 58-year-old white man with a history of alcoholism presented to the emergency department with epigastric and right upper quadrant pain radiating to the back, as well as emesis and anorexia. An elevated lipase of 16,609 U/L (reference range, 31–186 U/L) and pathognomonic abdominal computed tomography (CT) findings (FIGURE 1) led to the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, for which he was admitted.

Fluid resuscitation and pain management were implemented, and over 3 days his diet was advanced from NPO to clear fluids to a full diet. On the sixth day of hospitalization, the patient developed increasing abdominal pain and worsening leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 16.6–22 K/mcL [reference range, 4.5–11 K/mcL]). Repeat CT and blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was started on intravenous meropenem 1 g every 8 hours for presumed necrotizing pancreatitis. The next day he developed acutely tender red to pink patches and nodules on his shins and medial lower legs (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pancreatic panniculitis

It’s theorized that the systemic release of trypsin from pancreatic cell destruction causes increased capillary permeability and subsequent escape of lipase from the circulation into the subcutaneous fat. This causes fat necrosis, saponification, and inflammation.3,4 Pancreatic panniculitis is demonstrated histologically as hollowed-out adipocytes with granular basophilic cytoplasm and displaced or absent nuclei—aptly named “ghostlike” adipocytes.3-6

Painful, erythematous nodules most commonly present on the distal lower extremities. Nodules may be found over the shins, posterior calves, and periarticular skin. Rarely, nodules may occur on the buttocks, abdomen, or intramedullary bone.7 In severe cases, nodules spontaneously may ulcerate and drain an oily brown, viscous material formed from necrotic adipocytes.1

Timing of the eruption of skin lesions is varied and may even precede abdominal pain. Lesions can involute and regress several weeks after the underlying etiology improves. With pancreatic carcinoma, there is a greater likelihood of persistence, atypical locations of involvement, ulcerations, and recurrences.7

The histologic features of pancreatic panniculitis and the assessment of the subcutaneous fat are paramount in diagnosis. A deep punch biopsy or incisional biopsy is necessary to reliably reach the depth of the subcutaneous tissue. In our patient, a deep punch biopsy from the lateral calf was performed at the suggestion of Dermatology, and histopathology revealed necrosis of fat lobules with calcium soap around necrotic lipocytes, consistent with pancreatic panniculitis (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

The differential diagnosis was broad due to the confounding factors of recent antibiotic use and worsening pancreatitis.

Cellulitis may present as a red patch and is common on the lower legs; it often is associated with skin pathogens including Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. Usually, symptoms are unilateral and associated with warmth to the touch, expanding borders, leukocytosis, and systemic symptoms.

Vasculitis, which is an inflammation of various sized vessels through immunologic or infectious processes, often manifests on the lower legs. The characteristic sign of small vessel vasculitis is nonblanching purpura or petechiae. There often is a preceding illness or medication that triggers immunoglobulin proliferation and off-target inflammation of the vessels. Associated symptoms include pain and pruritus.

Drug eruptions may present as red patches on the skin. Often the patches are scaly and red and have more widespread distribution than the lower legs. A history of exposure is important, but common inciting drugs include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that may be used only occasionally and are challenging to elicit in the history. Our patient did have known drug changes (ie, the introduction of meropenem) while hospitalized, but the morphology was not consistent with this diagnosis.

Treatment is directed to underlying disease

Treatment of pancreatic panniculitis primarily is supportive and directed toward treating the underlying pancreatic disease. Depending upon the underlying pancreatic diagnosis, surgical correction of anatomic or ductal anomalies or pseudocysts may lead to resolution of panniculitis.3,7,8

Continue to: In this case

In this case, our patient had already received fluid resuscitation and pain management, and his diet had been advanced. In addition, his antibiotics were changed to exclude drug eruption as a cause. Over the course of a week, our patient saw a reduction in his pain level and an improvement in the appearance of his legs (FIGURE 4).

His pancreatitis, however, continued to persist and resist increases in his diet. He ultimately required transfer to a tertiary care center for consideration of interventional options including stenting. The patient ultimately recovered, after stenting of the main pancreatic duct, and was discharged home.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, 6 East Chestnut Street, Augusta, ME 04330; Jonathan.Karnes@mainegeneral.org

A 58-year-old white man with a history of alcoholism presented to the emergency department with epigastric and right upper quadrant pain radiating to the back, as well as emesis and anorexia. An elevated lipase of 16,609 U/L (reference range, 31–186 U/L) and pathognomonic abdominal computed tomography (CT) findings (FIGURE 1) led to the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, for which he was admitted.

Fluid resuscitation and pain management were implemented, and over 3 days his diet was advanced from NPO to clear fluids to a full diet. On the sixth day of hospitalization, the patient developed increasing abdominal pain and worsening leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 16.6–22 K/mcL [reference range, 4.5–11 K/mcL]). Repeat CT and blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was started on intravenous meropenem 1 g every 8 hours for presumed necrotizing pancreatitis. The next day he developed acutely tender red to pink patches and nodules on his shins and medial lower legs (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pancreatic panniculitis

It’s theorized that the systemic release of trypsin from pancreatic cell destruction causes increased capillary permeability and subsequent escape of lipase from the circulation into the subcutaneous fat. This causes fat necrosis, saponification, and inflammation.3,4 Pancreatic panniculitis is demonstrated histologically as hollowed-out adipocytes with granular basophilic cytoplasm and displaced or absent nuclei—aptly named “ghostlike” adipocytes.3-6

Painful, erythematous nodules most commonly present on the distal lower extremities. Nodules may be found over the shins, posterior calves, and periarticular skin. Rarely, nodules may occur on the buttocks, abdomen, or intramedullary bone.7 In severe cases, nodules spontaneously may ulcerate and drain an oily brown, viscous material formed from necrotic adipocytes.1

Timing of the eruption of skin lesions is varied and may even precede abdominal pain. Lesions can involute and regress several weeks after the underlying etiology improves. With pancreatic carcinoma, there is a greater likelihood of persistence, atypical locations of involvement, ulcerations, and recurrences.7

The histologic features of pancreatic panniculitis and the assessment of the subcutaneous fat are paramount in diagnosis. A deep punch biopsy or incisional biopsy is necessary to reliably reach the depth of the subcutaneous tissue. In our patient, a deep punch biopsy from the lateral calf was performed at the suggestion of Dermatology, and histopathology revealed necrosis of fat lobules with calcium soap around necrotic lipocytes, consistent with pancreatic panniculitis (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

The differential diagnosis was broad due to the confounding factors of recent antibiotic use and worsening pancreatitis.

Cellulitis may present as a red patch and is common on the lower legs; it often is associated with skin pathogens including Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. Usually, symptoms are unilateral and associated with warmth to the touch, expanding borders, leukocytosis, and systemic symptoms.

Vasculitis, which is an inflammation of various sized vessels through immunologic or infectious processes, often manifests on the lower legs. The characteristic sign of small vessel vasculitis is nonblanching purpura or petechiae. There often is a preceding illness or medication that triggers immunoglobulin proliferation and off-target inflammation of the vessels. Associated symptoms include pain and pruritus.

Drug eruptions may present as red patches on the skin. Often the patches are scaly and red and have more widespread distribution than the lower legs. A history of exposure is important, but common inciting drugs include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that may be used only occasionally and are challenging to elicit in the history. Our patient did have known drug changes (ie, the introduction of meropenem) while hospitalized, but the morphology was not consistent with this diagnosis.

Treatment is directed to underlying disease

Treatment of pancreatic panniculitis primarily is supportive and directed toward treating the underlying pancreatic disease. Depending upon the underlying pancreatic diagnosis, surgical correction of anatomic or ductal anomalies or pseudocysts may lead to resolution of panniculitis.3,7,8

Continue to: In this case

In this case, our patient had already received fluid resuscitation and pain management, and his diet had been advanced. In addition, his antibiotics were changed to exclude drug eruption as a cause. Over the course of a week, our patient saw a reduction in his pain level and an improvement in the appearance of his legs (FIGURE 4).

His pancreatitis, however, continued to persist and resist increases in his diet. He ultimately required transfer to a tertiary care center for consideration of interventional options including stenting. The patient ultimately recovered, after stenting of the main pancreatic duct, and was discharged home.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, 6 East Chestnut Street, Augusta, ME 04330; Jonathan.Karnes@mainegeneral.org

1. Madarasingha NP, Satgurunathan K, Fernando R. Pancreatic panniculitis: a rare form of panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

2. Haber RM, Assaad DM. Panniculitis associated with a pancreas divisum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 pt 2):331-334.

3. Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

4. Rongioletti F, Caputo V. Pancreatic panniculitis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148:419-425.

5. Förström TL, Winkelmann RK. Acute, generalized panniculitis with amylase and lipase in skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:497-502.

6. Hughes SH, Apisarnthanarax P, Mullins F. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:506-510.

7. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

8. Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, et al. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chro nic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1835-1837.

1. Madarasingha NP, Satgurunathan K, Fernando R. Pancreatic panniculitis: a rare form of panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

2. Haber RM, Assaad DM. Panniculitis associated with a pancreas divisum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 pt 2):331-334.

3. Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

4. Rongioletti F, Caputo V. Pancreatic panniculitis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148:419-425.

5. Förström TL, Winkelmann RK. Acute, generalized panniculitis with amylase and lipase in skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:497-502.

6. Hughes SH, Apisarnthanarax P, Mullins F. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:506-510.

7. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

8. Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, et al. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chro nic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1835-1837.

Aspirin, Yes, for at-risk elderly—but what about the healthy elderly?

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A healthy 72-year-old man with well-controlled hypertension on amlodipine 10 mg/d presents to you for an annual exam. He has no history of coronary artery disease or stroke. Should you recommend that he start aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease?

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death in the United States.2 Aspirin therapy remains the standard of care for secondary prevention of CVD in patients with known coronary artery disease (CAD).3 Aspirin reduces the risk of atherothrombosis by irreversibly inhibiting platelet function. At the same time, it increases the risk of major bleeding, including gastrointestinal bleeds and hemorrhagic strokes. Even though the benefit of aspirin in patients with known CAD is well established, the benefit of aspirin as primary prevention is less certain.

Two recent large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examined the benefits and risks of aspirin in a variety of patient populations. The ARRIVE trial looked at more than 12,000 patients with a mean age of 63 years with moderate risk of CVD (approximately 15% risk of a cardiovascular event in 10 years) and randomly assigned them to receive aspirin or placebo.4 After an average follow-up period of 5 years, researchers observed that actual cardiovascular event risk was < 10% in both groups, and there was no significant difference in the primary outcome of first cardiovascular event or all-cause mortality. There was, however, a significant increase in bleeding events in the group receiving aspirin.4

The ASCEND trial evaluated aspirin vs placebo in more than 15,000 adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and a low risk of CVD (< 10% risk of cardiovascular event in 5 years). 5 The primary endpoint of the study was first cardiovascular event. The authors found a significantly lower rate of cardiovascular events in the aspirin group, as well as more major bleeding events. Additionally, there was no difference between the aspirin and placebo groups in all-cause mortality after 7 years. The authors concluded that the benefits of aspirin in this group were counterbalanced by the harms.5

Currently, several organizations offer recommendations on aspirin use in people 40 to 70 years of age based on a patient’s risk of bleeding and risk of CVD.6-8 Recommendations regarding aspirin use as primary prevention have been less clear for patients < 40 and > 70 years of age.6

Elderly patients are at higher risk of CVD and bleeding, but until recently, few studies had evaluated elderly populations to assess the benefits vs the risks of aspirin for primary CVD prevention. As of 2016, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) stated the evidence was insufficient to assess the balance of the benefits and harms of initiating aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD in patients older than 70 years of age.6 This trial focuses on aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD in healthy elderly adults.

STUDY SUMMARY

Don’t use aspirin as primary prevention of CVD in the elderly

This secondary analysis of a prior double-blind RCT, which found low-dose aspirin did not prolong survival in elderly patients, examined the effect of aspirin on CVD and hemorrhage in 19,114 elderly patients without known CVD.1 The patients were ≥ 70 years of age (≥ 65 years for blacks and Hispanics) with a mean age of 74 years and were from Australia (87%) and the United States (13%). Approximately one-third of the patients were taking a statin, and 14% were taking a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) regularly. Patients were randomized to either aspirin 100 mg/d or matching placebo and were followed for an average of 4.7 years.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes. The outcome of CVD was a composite of fatal coronary heart disease, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), fatal or nonfatal ischemic stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure, and the outcome of major adverse cardiovascular event was a composite of fatal cardiovascular disease (excluding death from heart failure), nonfatal MI, or fatal and nonfatal ischemic stroke.

Results. No difference was seen between the aspirin and placebo groups in CVD outcomes (10.7 events per 1000 person-years vs 11.3 events per 1000 person-years, respectively; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.95; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.83-1.08) or major cardiovascular events (7.8 events per 1000 person-years vs 8.8 events per 1000 person-years, respectively; HR = 0.89; 95% CI, 0.77-1.03). The composite and individual endpoints of fatal cardiovascular disease, heart failure hospitalizations, fatal and nonfatal MI, and ischemic stroke also did not differ significantly between the groups.

The rate of major hemorrhagic events (composite of hemorrhagic stroke, intracranial bleed, or extracranial bleed), however, was higher in the aspirin vs the placebo group (8.6 events per 1000 person-years vs 6.2 events per 1000 person-years, respectively; HR = 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.6; number needed to harm = 98).

WHAT’S NEW

Finding of more harm than good leads to change in ACC/AHA guidelines

Although the most recent USPSTF guidelines state the evidence is insufficient to assess the risks and benefits of aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in this age group, this trial reveals there is a greater risk of hemorrhagic events than there is prevention of cardiovascular outcomes with aspirin use in healthy elderly patients > 70 years of age.6 Because of this trial, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) have updated their guidelines on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease to recommend that aspirin not be used routinely in patients > 70 years of age.7

CAVEATS

Potential benefit to people at higher risk?

The rate of cardiovascular disease was lower than expected in this overall healthy population, so it is not known if cardiovascular benefits may outweigh the risk of bleeding in a higher-risk population. The trial also didn’t address the potential harms of deprescribing aspirin. Additionally, although aspirin may not be protective for cardiovascular events and may lead to more bleeding, there may be other benefits to aspirin in this patient population that were not addressed by this study.

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Popular beliefs and wide availability may make tide difficult to change

Patients have been told for years to take a daily aspirin to “protect their heart”; this behavior may be difficult to change. And because aspirin is widely available over the counter, patients may take it without their physician’s knowledge.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. McNeil JJ, Wolfe R, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on cardiovascular events and bleeding in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1509-1518.

2. Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD, et al. Mortality in the United States, 2017. NCHS Data Brief, no. 328. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018.

3. Smith SC Jr, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2011;124:2458-2473.

4. Gaziano JM, Brotons C, Coppolecchia R, et al. Use of aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events in patients at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease (ARRIVE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392:1036-1046.

5. Bowman L, Mafham M, Wallendszus K, et al; ASCEND Study Collaborative Group. Effects of aspirin for primary prevention in persons with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1529-1539.

6. Bibbins-Domingo K; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:836-845.

7. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1376-1414.

8. American Diabetes Association. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S103-S123.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A healthy 72-year-old man with well-controlled hypertension on amlodipine 10 mg/d presents to you for an annual exam. He has no history of coronary artery disease or stroke. Should you recommend that he start aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease?

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death in the United States.2 Aspirin therapy remains the standard of care for secondary prevention of CVD in patients with known coronary artery disease (CAD).3 Aspirin reduces the risk of atherothrombosis by irreversibly inhibiting platelet function. At the same time, it increases the risk of major bleeding, including gastrointestinal bleeds and hemorrhagic strokes. Even though the benefit of aspirin in patients with known CAD is well established, the benefit of aspirin as primary prevention is less certain.

Two recent large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examined the benefits and risks of aspirin in a variety of patient populations. The ARRIVE trial looked at more than 12,000 patients with a mean age of 63 years with moderate risk of CVD (approximately 15% risk of a cardiovascular event in 10 years) and randomly assigned them to receive aspirin or placebo.4 After an average follow-up period of 5 years, researchers observed that actual cardiovascular event risk was < 10% in both groups, and there was no significant difference in the primary outcome of first cardiovascular event or all-cause mortality. There was, however, a significant increase in bleeding events in the group receiving aspirin.4

The ASCEND trial evaluated aspirin vs placebo in more than 15,000 adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and a low risk of CVD (< 10% risk of cardiovascular event in 5 years). 5 The primary endpoint of the study was first cardiovascular event. The authors found a significantly lower rate of cardiovascular events in the aspirin group, as well as more major bleeding events. Additionally, there was no difference between the aspirin and placebo groups in all-cause mortality after 7 years. The authors concluded that the benefits of aspirin in this group were counterbalanced by the harms.5

Currently, several organizations offer recommendations on aspirin use in people 40 to 70 years of age based on a patient’s risk of bleeding and risk of CVD.6-8 Recommendations regarding aspirin use as primary prevention have been less clear for patients < 40 and > 70 years of age.6

Elderly patients are at higher risk of CVD and bleeding, but until recently, few studies had evaluated elderly populations to assess the benefits vs the risks of aspirin for primary CVD prevention. As of 2016, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) stated the evidence was insufficient to assess the balance of the benefits and harms of initiating aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD in patients older than 70 years of age.6 This trial focuses on aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD in healthy elderly adults.

STUDY SUMMARY

Don’t use aspirin as primary prevention of CVD in the elderly

This secondary analysis of a prior double-blind RCT, which found low-dose aspirin did not prolong survival in elderly patients, examined the effect of aspirin on CVD and hemorrhage in 19,114 elderly patients without known CVD.1 The patients were ≥ 70 years of age (≥ 65 years for blacks and Hispanics) with a mean age of 74 years and were from Australia (87%) and the United States (13%). Approximately one-third of the patients were taking a statin, and 14% were taking a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) regularly. Patients were randomized to either aspirin 100 mg/d or matching placebo and were followed for an average of 4.7 years.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes. The outcome of CVD was a composite of fatal coronary heart disease, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), fatal or nonfatal ischemic stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure, and the outcome of major adverse cardiovascular event was a composite of fatal cardiovascular disease (excluding death from heart failure), nonfatal MI, or fatal and nonfatal ischemic stroke.

Results. No difference was seen between the aspirin and placebo groups in CVD outcomes (10.7 events per 1000 person-years vs 11.3 events per 1000 person-years, respectively; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.95; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.83-1.08) or major cardiovascular events (7.8 events per 1000 person-years vs 8.8 events per 1000 person-years, respectively; HR = 0.89; 95% CI, 0.77-1.03). The composite and individual endpoints of fatal cardiovascular disease, heart failure hospitalizations, fatal and nonfatal MI, and ischemic stroke also did not differ significantly between the groups.

The rate of major hemorrhagic events (composite of hemorrhagic stroke, intracranial bleed, or extracranial bleed), however, was higher in the aspirin vs the placebo group (8.6 events per 1000 person-years vs 6.2 events per 1000 person-years, respectively; HR = 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.6; number needed to harm = 98).

WHAT’S NEW

Finding of more harm than good leads to change in ACC/AHA guidelines

Although the most recent USPSTF guidelines state the evidence is insufficient to assess the risks and benefits of aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in this age group, this trial reveals there is a greater risk of hemorrhagic events than there is prevention of cardiovascular outcomes with aspirin use in healthy elderly patients > 70 years of age.6 Because of this trial, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) have updated their guidelines on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease to recommend that aspirin not be used routinely in patients > 70 years of age.7

CAVEATS

Potential benefit to people at higher risk?

The rate of cardiovascular disease was lower than expected in this overall healthy population, so it is not known if cardiovascular benefits may outweigh the risk of bleeding in a higher-risk population. The trial also didn’t address the potential harms of deprescribing aspirin. Additionally, although aspirin may not be protective for cardiovascular events and may lead to more bleeding, there may be other benefits to aspirin in this patient population that were not addressed by this study.

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Popular beliefs and wide availability may make tide difficult to change

Patients have been told for years to take a daily aspirin to “protect their heart”; this behavior may be difficult to change. And because aspirin is widely available over the counter, patients may take it without their physician’s knowledge.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A healthy 72-year-old man with well-controlled hypertension on amlodipine 10 mg/d presents to you for an annual exam. He has no history of coronary artery disease or stroke. Should you recommend that he start aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease?

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death in the United States.2 Aspirin therapy remains the standard of care for secondary prevention of CVD in patients with known coronary artery disease (CAD).3 Aspirin reduces the risk of atherothrombosis by irreversibly inhibiting platelet function. At the same time, it increases the risk of major bleeding, including gastrointestinal bleeds and hemorrhagic strokes. Even though the benefit of aspirin in patients with known CAD is well established, the benefit of aspirin as primary prevention is less certain.

Two recent large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examined the benefits and risks of aspirin in a variety of patient populations. The ARRIVE trial looked at more than 12,000 patients with a mean age of 63 years with moderate risk of CVD (approximately 15% risk of a cardiovascular event in 10 years) and randomly assigned them to receive aspirin or placebo.4 After an average follow-up period of 5 years, researchers observed that actual cardiovascular event risk was < 10% in both groups, and there was no significant difference in the primary outcome of first cardiovascular event or all-cause mortality. There was, however, a significant increase in bleeding events in the group receiving aspirin.4

The ASCEND trial evaluated aspirin vs placebo in more than 15,000 adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and a low risk of CVD (< 10% risk of cardiovascular event in 5 years). 5 The primary endpoint of the study was first cardiovascular event. The authors found a significantly lower rate of cardiovascular events in the aspirin group, as well as more major bleeding events. Additionally, there was no difference between the aspirin and placebo groups in all-cause mortality after 7 years. The authors concluded that the benefits of aspirin in this group were counterbalanced by the harms.5

Currently, several organizations offer recommendations on aspirin use in people 40 to 70 years of age based on a patient’s risk of bleeding and risk of CVD.6-8 Recommendations regarding aspirin use as primary prevention have been less clear for patients < 40 and > 70 years of age.6

Elderly patients are at higher risk of CVD and bleeding, but until recently, few studies had evaluated elderly populations to assess the benefits vs the risks of aspirin for primary CVD prevention. As of 2016, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) stated the evidence was insufficient to assess the balance of the benefits and harms of initiating aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD in patients older than 70 years of age.6 This trial focuses on aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD in healthy elderly adults.

STUDY SUMMARY

Don’t use aspirin as primary prevention of CVD in the elderly

This secondary analysis of a prior double-blind RCT, which found low-dose aspirin did not prolong survival in elderly patients, examined the effect of aspirin on CVD and hemorrhage in 19,114 elderly patients without known CVD.1 The patients were ≥ 70 years of age (≥ 65 years for blacks and Hispanics) with a mean age of 74 years and were from Australia (87%) and the United States (13%). Approximately one-third of the patients were taking a statin, and 14% were taking a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) regularly. Patients were randomized to either aspirin 100 mg/d or matching placebo and were followed for an average of 4.7 years.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes. The outcome of CVD was a composite of fatal coronary heart disease, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), fatal or nonfatal ischemic stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure, and the outcome of major adverse cardiovascular event was a composite of fatal cardiovascular disease (excluding death from heart failure), nonfatal MI, or fatal and nonfatal ischemic stroke.

Results. No difference was seen between the aspirin and placebo groups in CVD outcomes (10.7 events per 1000 person-years vs 11.3 events per 1000 person-years, respectively; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.95; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.83-1.08) or major cardiovascular events (7.8 events per 1000 person-years vs 8.8 events per 1000 person-years, respectively; HR = 0.89; 95% CI, 0.77-1.03). The composite and individual endpoints of fatal cardiovascular disease, heart failure hospitalizations, fatal and nonfatal MI, and ischemic stroke also did not differ significantly between the groups.

The rate of major hemorrhagic events (composite of hemorrhagic stroke, intracranial bleed, or extracranial bleed), however, was higher in the aspirin vs the placebo group (8.6 events per 1000 person-years vs 6.2 events per 1000 person-years, respectively; HR = 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-1.6; number needed to harm = 98).

WHAT’S NEW

Finding of more harm than good leads to change in ACC/AHA guidelines

Although the most recent USPSTF guidelines state the evidence is insufficient to assess the risks and benefits of aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in this age group, this trial reveals there is a greater risk of hemorrhagic events than there is prevention of cardiovascular outcomes with aspirin use in healthy elderly patients > 70 years of age.6 Because of this trial, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) have updated their guidelines on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease to recommend that aspirin not be used routinely in patients > 70 years of age.7

CAVEATS

Potential benefit to people at higher risk?

The rate of cardiovascular disease was lower than expected in this overall healthy population, so it is not known if cardiovascular benefits may outweigh the risk of bleeding in a higher-risk population. The trial also didn’t address the potential harms of deprescribing aspirin. Additionally, although aspirin may not be protective for cardiovascular events and may lead to more bleeding, there may be other benefits to aspirin in this patient population that were not addressed by this study.

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Popular beliefs and wide availability may make tide difficult to change

Patients have been told for years to take a daily aspirin to “protect their heart”; this behavior may be difficult to change. And because aspirin is widely available over the counter, patients may take it without their physician’s knowledge.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. McNeil JJ, Wolfe R, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on cardiovascular events and bleeding in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1509-1518.

2. Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD, et al. Mortality in the United States, 2017. NCHS Data Brief, no. 328. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018.

3. Smith SC Jr, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2011;124:2458-2473.

4. Gaziano JM, Brotons C, Coppolecchia R, et al. Use of aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events in patients at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease (ARRIVE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392:1036-1046.

5. Bowman L, Mafham M, Wallendszus K, et al; ASCEND Study Collaborative Group. Effects of aspirin for primary prevention in persons with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1529-1539.

6. Bibbins-Domingo K; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:836-845.

7. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1376-1414.

8. American Diabetes Association. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S103-S123.

1. McNeil JJ, Wolfe R, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on cardiovascular events and bleeding in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1509-1518.

2. Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD, et al. Mortality in the United States, 2017. NCHS Data Brief, no. 328. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018.

3. Smith SC Jr, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2011;124:2458-2473.

4. Gaziano JM, Brotons C, Coppolecchia R, et al. Use of aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events in patients at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease (ARRIVE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392:1036-1046.

5. Bowman L, Mafham M, Wallendszus K, et al; ASCEND Study Collaborative Group. Effects of aspirin for primary prevention in persons with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1529-1539.

6. Bibbins-Domingo K; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:836-845.

7. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1376-1414.

8. American Diabetes Association. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S103-S123.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Do not prescribe aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in your elderly patients. Aspirin does not improve cardiovascular outcomes and it significantly increases the risk of bleeding events.

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single randomized controlled trial.

McNeil JJ, Wolfe R, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on cardiovascular events and bleeding in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1509-1518.1

Sharp lower back pain • left-side paraspinal tenderness • anterior thigh sensory loss • Dx?

THE CASE