User login

Infected Bronchogenic Cyst With Left Atrial, Pulmonary Artery, and Esophageal Compression

Bronchogenic cyst is a rare foregut malformation that typically presents during the second decade of life that arises due to aberrant development from the tracheobronchial tree.1 Mediastinal bronchogenic cyst is the most common primary cystic lesion of the mediastinum, and bronchogenic cysts of the mediastinum represent 18% of all primary mediastinal malformations.2 Patients with mediastinal bronchogenic cysts may present with symptoms of cough, dyspnea, or wheezing if there is encroachment on surrounding structures.

Rarely, bronchogenic cysts can become infected. Definitive treatment of bronchogenic cysts is surgical excision; however, endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS)-guided drainage also can be employed. EBUS-guided drainage may be used when the cyst cannot be distinguished from solid mass on computed tomography (CT) images, to relieve symptomatic compression of surrounding structures, or to provide a histologic or microbial diagnosis in cases where surgical excision is not immediately available. We present the first-ever described case of bronchogenic cyst infected with Actinomyces, diagnosed by EBUS-guided drainage as well as a review of the literature regarding infected bronchogenic cysts and management of cysts affecting mediastinal structures.

Case Presentation

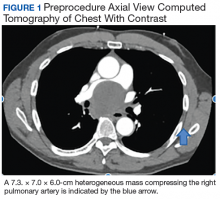

A 57-year-old African American male presented with a 4-day history of continuous, sharp, substernal chest pain accompanied by dyspnea. Additionally, the patient reported progressive dysphagia to solids. The posteroanterior view of a chest X-ray showed a widened mediastinum with splaying of the carina. A contrast-enhanced CT of the chest showed a large, middle mediastinal mass of heterogenous density measuring 7.3. × 7.0 × 6.0 cm with compression of the right pulmonary artery, left atria, superior vena cava and esophagus (Figure 1).

The mass demonstrated neither clear fluid-fluid level nor rounded structure with a distinct wall and uniform attenuation consistent with pure cystic structure and, in fact, was concerning for malignant process, such as lymphoma. Due to the malignancy concern and the findings of significant compression of surrounding mediastinal structures, the decision was made to proceed with bronchoscopy and EBUS-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) to assist in diagnosis and potentially provide symptomatic relief.

Under general anesthesia a P160 Olympus bronchoscope was advanced into the tracheobronchial tree; bronchoscopy with airway inspection revealed splayed carina with obtuse angle but was otherwise unremarkable. Next, an EBUS P160 fiber optic Olympus bronchoscope was advanced; ultrasound demonstrated a cystic structure. The EBUS-TBNA of cystic structure yielded 20 mL of brown, purulent fluid with decompression bringing pulmonary artery in ultrasound field (Figure 2). Rapid on-site cytology was performed with no preliminary findings of malignancy. The fluid was then sent for cytology and microbiologic evaluation.

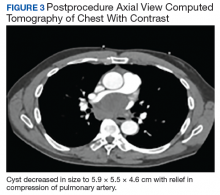

Following EBUS-guided aspiration, the patient reported significant improvement in chest pain, dyspnea, and dysphagia. A repeat chest CT demonstrated decrease in mass size to 5.9 × 5.5 × 4.6 cm with relief of the compression of the right pulmonary artery and decreased mass effect on the carina (Figure 3). Pathology ultimately demonstrated no evidence of malignancy but did demonstrate filamentous material with sulfur granules and anthracotic pigment suggestive of Actinomyces infection (Figure 4).

The patient was placed on amoxicillin/clavulanate 875 mg to 125 mg twice daily for 4 weeks based on antibiotic susceptibility testing to prevent progression to mediastinitis related to Actinomyces infection. The duration of therapy was extrapolated from treatment regimens described in case series of cervicofacial and abdominal Actinomyces infections.3 Thoracic surgery evaluation for definitive excision of cyst was recommended after the patient completed his course of antibiotics.

The patient underwent dental evaluation to identify the source of Actinomyces infection but there appeared to be no odontogenic source. The patient also had extensive skin survey with no findings of overt source of Actinomyces and CT abdomen/pelvis also identified no abscess that could be a potential source. He subsequently underwent thoracoscopic resection with pathology demonstrating a fibrous cyst wall lined with ciliated columnar epithelium consistent with diagnosis of bronchogenic cyst (Figure 5).

Discussion

Bronchogenic cysts can present at birth or later in life; patients may be asymptomatic for decades prior to discovery.4 Cysts located in the mediastinum can cause compression of the trachea and esophagus and cause cough, dyspnea, chest pain, and dysphagia.5 More life-threatening complications include infection, tracheal compression, malignant transformation, superior vena cava syndrome, or spontaneous rupture into the airway.6,7

Infection can occasionally occur, and various bacterial etiologies have been described. Hernandez-Solis and colleagues describe 12 cases of superinfected bronchogenic cysts with Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeroginosa, the most commonly described organisms.8 Casal and colleagues describe a case of α-hemolytic Streptococci treated with amoxicillin.9 Liman and colleagues describe 2 cases of bronchogenic cyst infected with Mycobacterium and cite an additional case report by Lin and colleagues similarly infected by Mycobacterium.10,11 Only 1 case was identified to have direct bronchial communication as a potential source of introduction of infection into bronchogenic cyst. In other cases, potential sources of infection were not identified, though it was postulated that direct ventilation could be a potential source of inoculation.

Surgical resection of mediastinal bronchogenic cysts has traditionally been considered the definitive treatment of choice.12,13 However, bronchogenic cysts may sometimes be difficult to differentiate from soft tissue tumors by chest CT, especially in cases of cysts with nonserous fluid. In particular, cysts that are infected are likely to have increased density and high attenuation on imaging; therefore, surgical excision may be delayed until diagnosis is made.14 Due to low complication rates, EBUS is increasingly used in the diagnosis and therapeutic management of bronchogenic cysts as an alternative to surgery, particularly for those who are symptomatic.15,16 Ultrasound guidance can allow for complete aspiration of the cyst, causing complete collapse of the cystic space and can facilitate adhesion between the mucosal surfaces lining the cavity and reduce recurrence.17 Nonetheless, bronchogenic cysts that are found to be infected, recur, or have a malignant component should be resected for definitive treatment.18

The mass discovered on our patient’s imaging appeared to have heterogenous attenuation consistent with malignancy rather than homogenous attenuation surrounded by a clearly demarcated wall consistent with a cystic structure; therefore, EBUS-TBNA was initially pursued and yielded an expedited diagnosis of the first-ever described bronchogenic cyst with Actinomyces superinfection as well as dramatic symptomatic relief of compression of surrounding mediastinal structures, particularly of the right pulmonary artery. As this is a congenital malformation, the patient was likely asymptomatic until the cyst became infected, after which he likely experience cyst growth with subsequent encroachment of surrounding mediastinal structures. Additionally, identification of pathogen by TBNA allowed for treatment before surgical excision, possibly avoiding accidental spread of pathogen intraoperatively.

Conclusions

Our case adds to the literature on the use of EBUS-TBNA as a diagnostic and therapeutic modality for bronchogenic cyst. While cases of mediastinitis and pleural effusion following EBUS-guided aspiration of bronchogenic cysts have been reported, complications are extremely rare.19 EBUS is increasingly favored as a means of immediate diagnosis and treatment in cases where CT imaging may not overtly suggest cystic structure and in patients experiencing compression of critical mediastinal structures.

1. Weber T, Roth TC, Beshay M, Herrmann P, Stein R, Schmid RA. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery of mediastinal bronchogenic cysts in adults: a single-center experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(3):987-991.

2. Martinod E, Pons F, Azorin J, et al. Thoracoscopic excision of mediastinal bronchogenic cysts: results in 20 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69(5):1525-1528.

3. Könönen E, Wade WG. Actinomyces and related organisms in human infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(2):419-442.

4. Ribet ME, Copin MC, Gosselin BH. Bronchogenic cysts of the lung. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61(6):1636-1640.

5. Guillem P, Porte H, Marquette CH, Wurtz A. Progressive dysphonia and acute respiratory failure: revealing a bronchogenic cyst. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;12(6):925-927.

6. McAdams HP, Kirejczyk WM, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Matsumoto S. Bronchogenic cyst: imaging features with clinical and histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 2000;217(2):441-446.

7. Rammohan G, Berger HW, Lajam F, Buhain WJ. Superior vena cava syndrome caused by bronchogenic cyst. Chest. 1975;68(4):599-601.

8. Hernández-Solís A, Cruz-Ortiz H, Gutiérrez-Díaz Ceballos ME, Cicero-Sabido R. Quistes broncogénicos. Importancia de la infección en adultos. Estudio de 12 casos [Bronchogenic cysts. Importance of infection in adults. Study of 12 cases]. Cir Cir. 2015;83(2):112-116.

9. Casal RF, Jimenez CA, Mehran RJ, et al. Infected mediastinal bronchogenic cyst successfully treated by endobronchial ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(4):e52-e53.

10. Liman ST, Dogan Y, Topcu S, Karabulut N, Demirkan N, Keser Z. Mycobacterial infection of intraparenchymal bronchogenic cysts. Respir Med. 2006;100(11):2060-2062.

11. Lin SH, Lee LN, Chang YL, Lee YC, Ding LW, Hsueh PR. Infected bronchogenic cyst due to Mycobacterium avium in an immunocompetent patient. J Infect. 2005;51(3):e131-e133.

12. Gharagozloo F, Dausmann MJ, McReynolds SD, Sanderson DR, Helmers RA. Recurrent bronchogenic pseudocyst 24 years after incomplete excision. Report of a case. Chest. 1995;108(3):880-883.

13. Bolton JW, Shahian DM. Asymptomatic bronchogenic cysts: what is the best management? Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;53(6):1134-1137.

14. Sarper A, Ayten A, Golbasi I, Demircan A, Isin E. Bronchogenic cyst. Tex Heart Inst J. 2003;30(2):105-108.

15. Varela-Lema L, Fernández-Villar A, Ruano-Ravina A. Effectiveness and safety of endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1156-1164.

16. Maturu VN, Dhooria S, Agarwal R. Efficacy and safety of transbronchial needle aspiration in diagnosis and treatment of mediastinal bronchogenic cysts: systematic review of case reports. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2015;22(3):195-203.

17. Galluccio G, Lucantoni G. Mediastinal bronchogenic cyst’s recurrence treated with EBUS-FNA with a long-term follow-up. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29(4):627-629.

18. Lee DH, Park CK, Kum DY, Kim JB, Hwang I. Clinical characteristics and management of intrathoracic bronchogenic cysts: a single center experience. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;44(4):279-284.

19. Onuki T, Kuramochi M, Inagaki M. Mediastinitis of bronchogenic cyst caused by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Respirol Case Rep. 2014;2(2):73-75.

Bronchogenic cyst is a rare foregut malformation that typically presents during the second decade of life that arises due to aberrant development from the tracheobronchial tree.1 Mediastinal bronchogenic cyst is the most common primary cystic lesion of the mediastinum, and bronchogenic cysts of the mediastinum represent 18% of all primary mediastinal malformations.2 Patients with mediastinal bronchogenic cysts may present with symptoms of cough, dyspnea, or wheezing if there is encroachment on surrounding structures.

Rarely, bronchogenic cysts can become infected. Definitive treatment of bronchogenic cysts is surgical excision; however, endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS)-guided drainage also can be employed. EBUS-guided drainage may be used when the cyst cannot be distinguished from solid mass on computed tomography (CT) images, to relieve symptomatic compression of surrounding structures, or to provide a histologic or microbial diagnosis in cases where surgical excision is not immediately available. We present the first-ever described case of bronchogenic cyst infected with Actinomyces, diagnosed by EBUS-guided drainage as well as a review of the literature regarding infected bronchogenic cysts and management of cysts affecting mediastinal structures.

Case Presentation

A 57-year-old African American male presented with a 4-day history of continuous, sharp, substernal chest pain accompanied by dyspnea. Additionally, the patient reported progressive dysphagia to solids. The posteroanterior view of a chest X-ray showed a widened mediastinum with splaying of the carina. A contrast-enhanced CT of the chest showed a large, middle mediastinal mass of heterogenous density measuring 7.3. × 7.0 × 6.0 cm with compression of the right pulmonary artery, left atria, superior vena cava and esophagus (Figure 1).

The mass demonstrated neither clear fluid-fluid level nor rounded structure with a distinct wall and uniform attenuation consistent with pure cystic structure and, in fact, was concerning for malignant process, such as lymphoma. Due to the malignancy concern and the findings of significant compression of surrounding mediastinal structures, the decision was made to proceed with bronchoscopy and EBUS-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) to assist in diagnosis and potentially provide symptomatic relief.

Under general anesthesia a P160 Olympus bronchoscope was advanced into the tracheobronchial tree; bronchoscopy with airway inspection revealed splayed carina with obtuse angle but was otherwise unremarkable. Next, an EBUS P160 fiber optic Olympus bronchoscope was advanced; ultrasound demonstrated a cystic structure. The EBUS-TBNA of cystic structure yielded 20 mL of brown, purulent fluid with decompression bringing pulmonary artery in ultrasound field (Figure 2). Rapid on-site cytology was performed with no preliminary findings of malignancy. The fluid was then sent for cytology and microbiologic evaluation.

Following EBUS-guided aspiration, the patient reported significant improvement in chest pain, dyspnea, and dysphagia. A repeat chest CT demonstrated decrease in mass size to 5.9 × 5.5 × 4.6 cm with relief of the compression of the right pulmonary artery and decreased mass effect on the carina (Figure 3). Pathology ultimately demonstrated no evidence of malignancy but did demonstrate filamentous material with sulfur granules and anthracotic pigment suggestive of Actinomyces infection (Figure 4).

The patient was placed on amoxicillin/clavulanate 875 mg to 125 mg twice daily for 4 weeks based on antibiotic susceptibility testing to prevent progression to mediastinitis related to Actinomyces infection. The duration of therapy was extrapolated from treatment regimens described in case series of cervicofacial and abdominal Actinomyces infections.3 Thoracic surgery evaluation for definitive excision of cyst was recommended after the patient completed his course of antibiotics.

The patient underwent dental evaluation to identify the source of Actinomyces infection but there appeared to be no odontogenic source. The patient also had extensive skin survey with no findings of overt source of Actinomyces and CT abdomen/pelvis also identified no abscess that could be a potential source. He subsequently underwent thoracoscopic resection with pathology demonstrating a fibrous cyst wall lined with ciliated columnar epithelium consistent with diagnosis of bronchogenic cyst (Figure 5).

Discussion

Bronchogenic cysts can present at birth or later in life; patients may be asymptomatic for decades prior to discovery.4 Cysts located in the mediastinum can cause compression of the trachea and esophagus and cause cough, dyspnea, chest pain, and dysphagia.5 More life-threatening complications include infection, tracheal compression, malignant transformation, superior vena cava syndrome, or spontaneous rupture into the airway.6,7

Infection can occasionally occur, and various bacterial etiologies have been described. Hernandez-Solis and colleagues describe 12 cases of superinfected bronchogenic cysts with Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeroginosa, the most commonly described organisms.8 Casal and colleagues describe a case of α-hemolytic Streptococci treated with amoxicillin.9 Liman and colleagues describe 2 cases of bronchogenic cyst infected with Mycobacterium and cite an additional case report by Lin and colleagues similarly infected by Mycobacterium.10,11 Only 1 case was identified to have direct bronchial communication as a potential source of introduction of infection into bronchogenic cyst. In other cases, potential sources of infection were not identified, though it was postulated that direct ventilation could be a potential source of inoculation.

Surgical resection of mediastinal bronchogenic cysts has traditionally been considered the definitive treatment of choice.12,13 However, bronchogenic cysts may sometimes be difficult to differentiate from soft tissue tumors by chest CT, especially in cases of cysts with nonserous fluid. In particular, cysts that are infected are likely to have increased density and high attenuation on imaging; therefore, surgical excision may be delayed until diagnosis is made.14 Due to low complication rates, EBUS is increasingly used in the diagnosis and therapeutic management of bronchogenic cysts as an alternative to surgery, particularly for those who are symptomatic.15,16 Ultrasound guidance can allow for complete aspiration of the cyst, causing complete collapse of the cystic space and can facilitate adhesion between the mucosal surfaces lining the cavity and reduce recurrence.17 Nonetheless, bronchogenic cysts that are found to be infected, recur, or have a malignant component should be resected for definitive treatment.18

The mass discovered on our patient’s imaging appeared to have heterogenous attenuation consistent with malignancy rather than homogenous attenuation surrounded by a clearly demarcated wall consistent with a cystic structure; therefore, EBUS-TBNA was initially pursued and yielded an expedited diagnosis of the first-ever described bronchogenic cyst with Actinomyces superinfection as well as dramatic symptomatic relief of compression of surrounding mediastinal structures, particularly of the right pulmonary artery. As this is a congenital malformation, the patient was likely asymptomatic until the cyst became infected, after which he likely experience cyst growth with subsequent encroachment of surrounding mediastinal structures. Additionally, identification of pathogen by TBNA allowed for treatment before surgical excision, possibly avoiding accidental spread of pathogen intraoperatively.

Conclusions

Our case adds to the literature on the use of EBUS-TBNA as a diagnostic and therapeutic modality for bronchogenic cyst. While cases of mediastinitis and pleural effusion following EBUS-guided aspiration of bronchogenic cysts have been reported, complications are extremely rare.19 EBUS is increasingly favored as a means of immediate diagnosis and treatment in cases where CT imaging may not overtly suggest cystic structure and in patients experiencing compression of critical mediastinal structures.

Bronchogenic cyst is a rare foregut malformation that typically presents during the second decade of life that arises due to aberrant development from the tracheobronchial tree.1 Mediastinal bronchogenic cyst is the most common primary cystic lesion of the mediastinum, and bronchogenic cysts of the mediastinum represent 18% of all primary mediastinal malformations.2 Patients with mediastinal bronchogenic cysts may present with symptoms of cough, dyspnea, or wheezing if there is encroachment on surrounding structures.

Rarely, bronchogenic cysts can become infected. Definitive treatment of bronchogenic cysts is surgical excision; however, endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS)-guided drainage also can be employed. EBUS-guided drainage may be used when the cyst cannot be distinguished from solid mass on computed tomography (CT) images, to relieve symptomatic compression of surrounding structures, or to provide a histologic or microbial diagnosis in cases where surgical excision is not immediately available. We present the first-ever described case of bronchogenic cyst infected with Actinomyces, diagnosed by EBUS-guided drainage as well as a review of the literature regarding infected bronchogenic cysts and management of cysts affecting mediastinal structures.

Case Presentation

A 57-year-old African American male presented with a 4-day history of continuous, sharp, substernal chest pain accompanied by dyspnea. Additionally, the patient reported progressive dysphagia to solids. The posteroanterior view of a chest X-ray showed a widened mediastinum with splaying of the carina. A contrast-enhanced CT of the chest showed a large, middle mediastinal mass of heterogenous density measuring 7.3. × 7.0 × 6.0 cm with compression of the right pulmonary artery, left atria, superior vena cava and esophagus (Figure 1).

The mass demonstrated neither clear fluid-fluid level nor rounded structure with a distinct wall and uniform attenuation consistent with pure cystic structure and, in fact, was concerning for malignant process, such as lymphoma. Due to the malignancy concern and the findings of significant compression of surrounding mediastinal structures, the decision was made to proceed with bronchoscopy and EBUS-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) to assist in diagnosis and potentially provide symptomatic relief.

Under general anesthesia a P160 Olympus bronchoscope was advanced into the tracheobronchial tree; bronchoscopy with airway inspection revealed splayed carina with obtuse angle but was otherwise unremarkable. Next, an EBUS P160 fiber optic Olympus bronchoscope was advanced; ultrasound demonstrated a cystic structure. The EBUS-TBNA of cystic structure yielded 20 mL of brown, purulent fluid with decompression bringing pulmonary artery in ultrasound field (Figure 2). Rapid on-site cytology was performed with no preliminary findings of malignancy. The fluid was then sent for cytology and microbiologic evaluation.

Following EBUS-guided aspiration, the patient reported significant improvement in chest pain, dyspnea, and dysphagia. A repeat chest CT demonstrated decrease in mass size to 5.9 × 5.5 × 4.6 cm with relief of the compression of the right pulmonary artery and decreased mass effect on the carina (Figure 3). Pathology ultimately demonstrated no evidence of malignancy but did demonstrate filamentous material with sulfur granules and anthracotic pigment suggestive of Actinomyces infection (Figure 4).

The patient was placed on amoxicillin/clavulanate 875 mg to 125 mg twice daily for 4 weeks based on antibiotic susceptibility testing to prevent progression to mediastinitis related to Actinomyces infection. The duration of therapy was extrapolated from treatment regimens described in case series of cervicofacial and abdominal Actinomyces infections.3 Thoracic surgery evaluation for definitive excision of cyst was recommended after the patient completed his course of antibiotics.

The patient underwent dental evaluation to identify the source of Actinomyces infection but there appeared to be no odontogenic source. The patient also had extensive skin survey with no findings of overt source of Actinomyces and CT abdomen/pelvis also identified no abscess that could be a potential source. He subsequently underwent thoracoscopic resection with pathology demonstrating a fibrous cyst wall lined with ciliated columnar epithelium consistent with diagnosis of bronchogenic cyst (Figure 5).

Discussion

Bronchogenic cysts can present at birth or later in life; patients may be asymptomatic for decades prior to discovery.4 Cysts located in the mediastinum can cause compression of the trachea and esophagus and cause cough, dyspnea, chest pain, and dysphagia.5 More life-threatening complications include infection, tracheal compression, malignant transformation, superior vena cava syndrome, or spontaneous rupture into the airway.6,7

Infection can occasionally occur, and various bacterial etiologies have been described. Hernandez-Solis and colleagues describe 12 cases of superinfected bronchogenic cysts with Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeroginosa, the most commonly described organisms.8 Casal and colleagues describe a case of α-hemolytic Streptococci treated with amoxicillin.9 Liman and colleagues describe 2 cases of bronchogenic cyst infected with Mycobacterium and cite an additional case report by Lin and colleagues similarly infected by Mycobacterium.10,11 Only 1 case was identified to have direct bronchial communication as a potential source of introduction of infection into bronchogenic cyst. In other cases, potential sources of infection were not identified, though it was postulated that direct ventilation could be a potential source of inoculation.

Surgical resection of mediastinal bronchogenic cysts has traditionally been considered the definitive treatment of choice.12,13 However, bronchogenic cysts may sometimes be difficult to differentiate from soft tissue tumors by chest CT, especially in cases of cysts with nonserous fluid. In particular, cysts that are infected are likely to have increased density and high attenuation on imaging; therefore, surgical excision may be delayed until diagnosis is made.14 Due to low complication rates, EBUS is increasingly used in the diagnosis and therapeutic management of bronchogenic cysts as an alternative to surgery, particularly for those who are symptomatic.15,16 Ultrasound guidance can allow for complete aspiration of the cyst, causing complete collapse of the cystic space and can facilitate adhesion between the mucosal surfaces lining the cavity and reduce recurrence.17 Nonetheless, bronchogenic cysts that are found to be infected, recur, or have a malignant component should be resected for definitive treatment.18

The mass discovered on our patient’s imaging appeared to have heterogenous attenuation consistent with malignancy rather than homogenous attenuation surrounded by a clearly demarcated wall consistent with a cystic structure; therefore, EBUS-TBNA was initially pursued and yielded an expedited diagnosis of the first-ever described bronchogenic cyst with Actinomyces superinfection as well as dramatic symptomatic relief of compression of surrounding mediastinal structures, particularly of the right pulmonary artery. As this is a congenital malformation, the patient was likely asymptomatic until the cyst became infected, after which he likely experience cyst growth with subsequent encroachment of surrounding mediastinal structures. Additionally, identification of pathogen by TBNA allowed for treatment before surgical excision, possibly avoiding accidental spread of pathogen intraoperatively.

Conclusions

Our case adds to the literature on the use of EBUS-TBNA as a diagnostic and therapeutic modality for bronchogenic cyst. While cases of mediastinitis and pleural effusion following EBUS-guided aspiration of bronchogenic cysts have been reported, complications are extremely rare.19 EBUS is increasingly favored as a means of immediate diagnosis and treatment in cases where CT imaging may not overtly suggest cystic structure and in patients experiencing compression of critical mediastinal structures.

1. Weber T, Roth TC, Beshay M, Herrmann P, Stein R, Schmid RA. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery of mediastinal bronchogenic cysts in adults: a single-center experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(3):987-991.

2. Martinod E, Pons F, Azorin J, et al. Thoracoscopic excision of mediastinal bronchogenic cysts: results in 20 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69(5):1525-1528.

3. Könönen E, Wade WG. Actinomyces and related organisms in human infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(2):419-442.

4. Ribet ME, Copin MC, Gosselin BH. Bronchogenic cysts of the lung. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61(6):1636-1640.

5. Guillem P, Porte H, Marquette CH, Wurtz A. Progressive dysphonia and acute respiratory failure: revealing a bronchogenic cyst. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;12(6):925-927.

6. McAdams HP, Kirejczyk WM, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Matsumoto S. Bronchogenic cyst: imaging features with clinical and histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 2000;217(2):441-446.

7. Rammohan G, Berger HW, Lajam F, Buhain WJ. Superior vena cava syndrome caused by bronchogenic cyst. Chest. 1975;68(4):599-601.

8. Hernández-Solís A, Cruz-Ortiz H, Gutiérrez-Díaz Ceballos ME, Cicero-Sabido R. Quistes broncogénicos. Importancia de la infección en adultos. Estudio de 12 casos [Bronchogenic cysts. Importance of infection in adults. Study of 12 cases]. Cir Cir. 2015;83(2):112-116.

9. Casal RF, Jimenez CA, Mehran RJ, et al. Infected mediastinal bronchogenic cyst successfully treated by endobronchial ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(4):e52-e53.

10. Liman ST, Dogan Y, Topcu S, Karabulut N, Demirkan N, Keser Z. Mycobacterial infection of intraparenchymal bronchogenic cysts. Respir Med. 2006;100(11):2060-2062.

11. Lin SH, Lee LN, Chang YL, Lee YC, Ding LW, Hsueh PR. Infected bronchogenic cyst due to Mycobacterium avium in an immunocompetent patient. J Infect. 2005;51(3):e131-e133.

12. Gharagozloo F, Dausmann MJ, McReynolds SD, Sanderson DR, Helmers RA. Recurrent bronchogenic pseudocyst 24 years after incomplete excision. Report of a case. Chest. 1995;108(3):880-883.

13. Bolton JW, Shahian DM. Asymptomatic bronchogenic cysts: what is the best management? Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;53(6):1134-1137.

14. Sarper A, Ayten A, Golbasi I, Demircan A, Isin E. Bronchogenic cyst. Tex Heart Inst J. 2003;30(2):105-108.

15. Varela-Lema L, Fernández-Villar A, Ruano-Ravina A. Effectiveness and safety of endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1156-1164.

16. Maturu VN, Dhooria S, Agarwal R. Efficacy and safety of transbronchial needle aspiration in diagnosis and treatment of mediastinal bronchogenic cysts: systematic review of case reports. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2015;22(3):195-203.

17. Galluccio G, Lucantoni G. Mediastinal bronchogenic cyst’s recurrence treated with EBUS-FNA with a long-term follow-up. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29(4):627-629.

18. Lee DH, Park CK, Kum DY, Kim JB, Hwang I. Clinical characteristics and management of intrathoracic bronchogenic cysts: a single center experience. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;44(4):279-284.

19. Onuki T, Kuramochi M, Inagaki M. Mediastinitis of bronchogenic cyst caused by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Respirol Case Rep. 2014;2(2):73-75.

1. Weber T, Roth TC, Beshay M, Herrmann P, Stein R, Schmid RA. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery of mediastinal bronchogenic cysts in adults: a single-center experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(3):987-991.

2. Martinod E, Pons F, Azorin J, et al. Thoracoscopic excision of mediastinal bronchogenic cysts: results in 20 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69(5):1525-1528.

3. Könönen E, Wade WG. Actinomyces and related organisms in human infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(2):419-442.

4. Ribet ME, Copin MC, Gosselin BH. Bronchogenic cysts of the lung. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61(6):1636-1640.

5. Guillem P, Porte H, Marquette CH, Wurtz A. Progressive dysphonia and acute respiratory failure: revealing a bronchogenic cyst. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;12(6):925-927.

6. McAdams HP, Kirejczyk WM, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Matsumoto S. Bronchogenic cyst: imaging features with clinical and histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 2000;217(2):441-446.

7. Rammohan G, Berger HW, Lajam F, Buhain WJ. Superior vena cava syndrome caused by bronchogenic cyst. Chest. 1975;68(4):599-601.

8. Hernández-Solís A, Cruz-Ortiz H, Gutiérrez-Díaz Ceballos ME, Cicero-Sabido R. Quistes broncogénicos. Importancia de la infección en adultos. Estudio de 12 casos [Bronchogenic cysts. Importance of infection in adults. Study of 12 cases]. Cir Cir. 2015;83(2):112-116.

9. Casal RF, Jimenez CA, Mehran RJ, et al. Infected mediastinal bronchogenic cyst successfully treated by endobronchial ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(4):e52-e53.

10. Liman ST, Dogan Y, Topcu S, Karabulut N, Demirkan N, Keser Z. Mycobacterial infection of intraparenchymal bronchogenic cysts. Respir Med. 2006;100(11):2060-2062.

11. Lin SH, Lee LN, Chang YL, Lee YC, Ding LW, Hsueh PR. Infected bronchogenic cyst due to Mycobacterium avium in an immunocompetent patient. J Infect. 2005;51(3):e131-e133.

12. Gharagozloo F, Dausmann MJ, McReynolds SD, Sanderson DR, Helmers RA. Recurrent bronchogenic pseudocyst 24 years after incomplete excision. Report of a case. Chest. 1995;108(3):880-883.

13. Bolton JW, Shahian DM. Asymptomatic bronchogenic cysts: what is the best management? Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;53(6):1134-1137.

14. Sarper A, Ayten A, Golbasi I, Demircan A, Isin E. Bronchogenic cyst. Tex Heart Inst J. 2003;30(2):105-108.

15. Varela-Lema L, Fernández-Villar A, Ruano-Ravina A. Effectiveness and safety of endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1156-1164.

16. Maturu VN, Dhooria S, Agarwal R. Efficacy and safety of transbronchial needle aspiration in diagnosis and treatment of mediastinal bronchogenic cysts: systematic review of case reports. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2015;22(3):195-203.

17. Galluccio G, Lucantoni G. Mediastinal bronchogenic cyst’s recurrence treated with EBUS-FNA with a long-term follow-up. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29(4):627-629.

18. Lee DH, Park CK, Kum DY, Kim JB, Hwang I. Clinical characteristics and management of intrathoracic bronchogenic cysts: a single center experience. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;44(4):279-284.

19. Onuki T, Kuramochi M, Inagaki M. Mediastinitis of bronchogenic cyst caused by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Respirol Case Rep. 2014;2(2):73-75.

Observations From Embedded Health Engagement Team Members

“Whenever possible, we will develop innovative, low-cost, and small-footprint approaches to achieve our security objectives.” 1

Team member and participant observations can deliver valuable insight into the effectiveness of an activity or project. Certainly, documentation of such qualitative assessment through survey questions or narratives can reveal important information for future action. This qualitative aspect was a significant consideration in the formation of an embedded health engagement team (EHET) intended to improve foreign assistance and health outcomes for global humanitarian and security cooperation activities.

Since health activities are centered on human interaction and relationships, some observation or qualitative assessment must be included to truly determine short-term local buy-in and long-term outcomes. The following observations include the direct narrative perspectives of team members from a multidisciplinary primary care EHET that add experiential depth to prior assessment of the pilot test of such teams during Continuing Promise 2011, a 9-country series of health engagement activities employed from the USNS Comfort.2 The embedded team consisted of US Air Force (USAF), US Navy (USN), and nongovernmental organization (NGO) personnel working directly in a primary care clinic of the Costa Rican public health system.

This is small sample of a few team members who responded to a simple, open-ended prompt to record their impression of the EHET concept and experiences. Documenting this information should highlight the importance of seeking similar qualitative mission data for future health engagements. Standardized questionnaires have been used to evaluate health activities and have provided valuable analysis and recommendations that have advanced US Department of Defense (DoD) global health engagement.3 Captured narrative observation from the EHET pilot study is a complementary qualitative method that supports the concept of small, well prepared, culturally competent, EHETs tailored to work within a partner system rather than outside of it will achieve greater mutual benefit, including the application of better, more equitable health and health system principles.4 In this embedded manner, health care professionals may readily contribute to host nation health sector plans and goals while achieving military objectives, political goals, and mutual strategic interests through both military-military and military-civilian applications.

Observations and Reflections

Family Physician (Maj, Second Physician, USAF)

“Overall, the experience I had with the embedded team was truly rewarding. I hope this becomes a tool used to augment humanitarian missions. There is no way to truly understand a systems strengths and weakness except by being embedded in the clinic or hospital. For 3 days I worked alongside a bilingual physician at a local family practice clinic. The clinic did full spectrum family practice, including prenatal care. The doctor saw between 25 and 35 patients each day plus covered urgent care during lunch. Paper charting was used although the clinic is looking into electronic records. The clinic was very efficient. All team members were very aware of their roles and did their jobs with a smile and worked well together.

“Most patient encounters took between 10 and 15 minutes although the patient might stay around for IV therapy, intramuscular pain medications, or other treatments that were carried out by the nursing staff. There was a small procedure room and procedures would be performed on the same day they were identified. The nursing staff would set up everything, and in between patients the provider would complete the procedure. On the first day I mostly shadowed, but in the afternoon, I was asked to consult on some of the more complicated patients with diabetes mellitus or hypertension. On the second day I shadowed a health care provider who did not speak English and through an interpreter he asked for my input. In the afternoon the nursing staff asked me to discuss the treatment of abscesses. I discussed techniques of incision and drainage and importance of packing and proper wound care, worked with one of their wound care nurses on packing of several wounds, and consulted on a patient with a venous stasis ulcer.

“We identified an educational opportunity for the nursing staff. On the third day I brought a US certified wound care specialist and I gave a Microsoft PowerPoint presentation on venous stasis ulcers and proper wound care. The nursing staff and clinic were very receptive and asked if we would develop a patient-based educational presentation. The wound care specialist spent the afternoon giving hands-on demonstrations in the wound care clinic, and I taught technique for excisional biopsy of skin tags and moles to physicians. One of the host physicians arranged for more consultations on more of the clinic’s complicated patients, which included a staff member and a relative.”

Medical Technician (MSgt, E-7, Independent Duty Medical Technician, USAF)

“The first day I was assigned to work with the ‘auxiliaries,’ nurses working in the urgent care area at the clinic. Their urgent care area had limited equipment and supplies and included equipment such as mercury thermometers, a few stethoscopes and 1 blood pressure cuff. Their duties consisted of screening patients, starting IVs, giving injections and breathing treatments. They also had a minor surgery room where the nurses helped.

“During the observation of the placement of an IV catheter, I noticed that they were using a port and attaching a needle to the IV tubing and leaving the needle attached to the patient. I asked them about their procedure and incidents with needlesticks since they had to be pretty accurate in getting the needle through the port. The nurse stated there were a significant number of cases of needlesticks. The following day, we brought 18-g, 20-g, and 23-g IV catheters, saline locks, syringes, and our team’s junior physician and I instructed the nurses how to set up an IV without using the needle port.

“The third day at the clinic, I assisted in checking in patients (blood pressure, weight, interviews). I also helped run the immunizations clinic, assisting in giving both pediatric and adult immunizations. Since there was only 1 nurse on shift that day, we multitasked and also gave injections prescribed by the providers, such as medroxyprogesterone and dexamethasone. By far, this was the most rewarding part of the mission. I really felt as though we were part of the team and believe we truly made a difference.”

Administrator (LTC, Medical Service Corps, USN)

“I learned many items from our visit to Clinica Dr. Francisco Quintanas Area de Salud 4 Chacarita. I reviewed the business plan contained in two 1.5-inch hardbound books. Their business plan outlined the population served, projections for upcoming year, and contracts. Area 4 served 21,344 people (11,197 men and 10,147 women). The business plan reviewed historical encounter information (ie, average patient is seen 2.6 times annually, 203,285 laboratory tests were performed in 2010, no radiology capabilities) and contained metrics for key programs for upcoming year (eg, vaccinations, women wellness) that seemed similar to US Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures.

“Our partners discussed financing of the health care they provide, including money flows to and from the government, the work center, and the employees. The business plan contains contract information and costs for maintenance, utilities, personnel, and other issues that would be typical for US-based operations as well. Housekeeping, some of the secretaries, and security staff are not employees—they are contracted personnel. Money is shifted to meet unexpected needs (ie, in 2009/2010–H1N1 influenza was unanticipated). Money was taken from other programs to meet the need.

“Within the Area 4 clinics there are 94 personnel, including 15 physicians. They have a document that is similar to our Activity Manning Document, which outlines personnel billet code, name, and specialty. The Asistentes Técnicos de Atención Primaria are the personnel who conduct home visits and are a unique capability—we do not have an exact equivalent in most US health care systems. Pregnant workers are released from work 1 month prior to the due date and are expected to return to work 3 months postdelivery.”

Medical Logistics (Capt, Medical Service Corps, USAF)

“Costa Rica is still growing in aspects of national health care but has a reliable system in place it seems. Similar to many of the countries visited, it has great capacity for building, but is challenged to increase its infrastructure. In 2011, part of this was due to a recent economic decline in the nation and its health care sector. They have interaction both with other regional clinics managed under the same national health system construct (Caja Costarricense del Seguro Social) as well as with private practices and specialty services. The clinics are open only daytime business hours. Only the regional hospital is open 24/7 for emergent care.

“Supplies are distributed to the regional clinics primarily from San José (the capital and largest city), but also there are some smaller warehousing of clinical materials located around the region. One of these warehouses was in Puntarenas where our clinic was located. To get better information for future supply chain management support we would need to speak with the central distribution/suppliers of all nationalized clinic-run entities. What our partners did teach is that at a higher, national level the clinics are standardized with what they will carry and need to keep on-hand depending upon the clinic classification (ie, level 1, 2, or 3).

“Equipment is purchased similar to the DoD method: Requests are submitted toward the end of the year, the administration prioritizes the lists, and then buys what they feel is most beneficial to the clinic with the resources available. Our hosts stated that before the end of the year, it is very difficult to prioritize needs other than some of the items that they ‘always need’ because they are unlikely to receive items very low on their list. The hosts stated that they would be very interested in having a chance to receive any excess US military equipment from their priority lists if there was a mechanism to do so. In future EHET missions, advance coordination would need to occur to see if (locally compatible) equipment needs could be met through the Defense Reutilization and Marketing Office (DRMO). Alternatively, an embedded team focused on Biomedical Equipment repair could work alongside partners such as at this clinic to develop a sustainable preventive maintenance and equipment testing program. Advance coordination on equipment status would foster improvement for resourceful partner clinics such as Chacarita, with targeted involvement from US military biomedical equipment technicians.”

Discussion

These 4 firsthand accounts from a multidisciplinary, primary-care focused, EHET offers multiple preliminary evidence of the value of this small-scale embedded approach. The accounts are responses to an open-ended prompt for personal impressions and key thoughts as part of an EHET. Three of the advantages gleaned from these accounts are greater personal satisfaction, detailed insight into local operations and health systems, and deeper empathy and respect for common challenges despite health system differences compared with the US military health system.

These advantages are critical to afford the US military personnel the ability to more effectively execute engagement goals, such as meeting health needs in humanitarian assistance, advancing interoperable capacity for security cooperation, or achieving targeted training to enhance US medical operational skills. The greater personal satisfaction was evident in the team member responses that, despite mission stops in 7 prior countries, “This by far was the most rewarding part of the Continuing Promise 2011 mission” and “I hope this becomes a tool used to augment humanitarian missions.”

The descriptions by both the administrator and the logistician on the intimate details that the hosts shared with them is a testament to the rapid trust engendered by the embedded approach. There was a trust to share information as a result of acknowledged local strengths and legitimate interest in local challenges. Peer appreciation was evident; although they did not speak the same literal language, they spoke the same professional language, which was apparent even through the use of an interpreter.

A third advantage, evident from these written exchanges is a regular acknowledgement that health system issues, pursued processes, and desired outcomes are similar between different systems. There may be significant differences in actual resources and infrastructure, but some of the bureaucracy is similar. This last insight is essential to grasp in order to seek capacity building and interoperable solutions toward common goals; empathy is needed to encourage local ownership and sustainability while respecting local challenges and different problem-solving approaches and processes.

Conclusions

The EHET concept afforded deep insight by team members into ways to partner with their hosts to target better health outcomes and meaningful partnership for potential long-term geopolitical impact. Long duration embedded teams, or recurrent insertion, in a single location will achieve greater long-term benefits because of greater health system and cultural understanding. EHETs, once accepted and refined from prototype to standard employment tool, should prove to be a more effective tool in building partnerships, building capacity, and increased security cooperation by using US military resources to support legitimate health needs either in a military-military or military-civilian setting.5 These firsthand accounts provide preliminary evidence that embedded teams may be a critical and needed tool to “ensure that military health engagement is appropriate, constructive, effective, and coordinated with other actors.”6

Acknowledgments

Additional original EHET team members included LCDR Jeanne Jimenez, RN; CDR Francine Worthington, Health Administrator; Maj Tony McClung, RN; Mrs. Romero, RN of LDS Charities, and the staff of the Chacarita clinics in Costa Rica.

1. US Department of Defense. Sustaining U.S. global leadership: priorities for 21st century defense. https://archive.defense.gov/news/Defense_Strategic_Guidance.pdf. Published January 2012. Accessed March 18, 2020.

2. Burkett EK. An embedded health engagement team pilot test, Mil Med. 2019;184(11-12):606-610.

3. Center for Disaster and Humanitarian Assistance Medicine. U.S. participants perspectives on military humanitarian assistance. https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=446168. Accessed March 18, 2020.

4. Burkett EK. Embedded health engagement teams for improved health outcomes and foreign assistance, Poster presented at: AMSUS Annual Meeting November 30, 2015; San Antonio, TX. http://cdm16005.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p16005coll8/id/14. Accessed March 18, 2020.

5. Burkett EK, Ubiera J, Vess, J, Griffay T, Neese B, Lawrence C. Developing the prototype embedded health engagement team, Poster presented at: Military Health System Research Symposium, August 21, 2018; Orlando, FL. https://cdm16005.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16005coll8/id/61/rec/1. Accessed March 18, 2020.

6. Michaud J, Moss K, Licina D, et al. Security and public health: the interface. Lancet. 2019;393(10168):P276-P286. http://glham.org/wp-content/uploads/Militaries-and-Global-Health-Lancet-Series.pdf. Accessed March 18, 2020.

“Whenever possible, we will develop innovative, low-cost, and small-footprint approaches to achieve our security objectives.” 1

Team member and participant observations can deliver valuable insight into the effectiveness of an activity or project. Certainly, documentation of such qualitative assessment through survey questions or narratives can reveal important information for future action. This qualitative aspect was a significant consideration in the formation of an embedded health engagement team (EHET) intended to improve foreign assistance and health outcomes for global humanitarian and security cooperation activities.

Since health activities are centered on human interaction and relationships, some observation or qualitative assessment must be included to truly determine short-term local buy-in and long-term outcomes. The following observations include the direct narrative perspectives of team members from a multidisciplinary primary care EHET that add experiential depth to prior assessment of the pilot test of such teams during Continuing Promise 2011, a 9-country series of health engagement activities employed from the USNS Comfort.2 The embedded team consisted of US Air Force (USAF), US Navy (USN), and nongovernmental organization (NGO) personnel working directly in a primary care clinic of the Costa Rican public health system.

This is small sample of a few team members who responded to a simple, open-ended prompt to record their impression of the EHET concept and experiences. Documenting this information should highlight the importance of seeking similar qualitative mission data for future health engagements. Standardized questionnaires have been used to evaluate health activities and have provided valuable analysis and recommendations that have advanced US Department of Defense (DoD) global health engagement.3 Captured narrative observation from the EHET pilot study is a complementary qualitative method that supports the concept of small, well prepared, culturally competent, EHETs tailored to work within a partner system rather than outside of it will achieve greater mutual benefit, including the application of better, more equitable health and health system principles.4 In this embedded manner, health care professionals may readily contribute to host nation health sector plans and goals while achieving military objectives, political goals, and mutual strategic interests through both military-military and military-civilian applications.

Observations and Reflections

Family Physician (Maj, Second Physician, USAF)

“Overall, the experience I had with the embedded team was truly rewarding. I hope this becomes a tool used to augment humanitarian missions. There is no way to truly understand a systems strengths and weakness except by being embedded in the clinic or hospital. For 3 days I worked alongside a bilingual physician at a local family practice clinic. The clinic did full spectrum family practice, including prenatal care. The doctor saw between 25 and 35 patients each day plus covered urgent care during lunch. Paper charting was used although the clinic is looking into electronic records. The clinic was very efficient. All team members were very aware of their roles and did their jobs with a smile and worked well together.

“Most patient encounters took between 10 and 15 minutes although the patient might stay around for IV therapy, intramuscular pain medications, or other treatments that were carried out by the nursing staff. There was a small procedure room and procedures would be performed on the same day they were identified. The nursing staff would set up everything, and in between patients the provider would complete the procedure. On the first day I mostly shadowed, but in the afternoon, I was asked to consult on some of the more complicated patients with diabetes mellitus or hypertension. On the second day I shadowed a health care provider who did not speak English and through an interpreter he asked for my input. In the afternoon the nursing staff asked me to discuss the treatment of abscesses. I discussed techniques of incision and drainage and importance of packing and proper wound care, worked with one of their wound care nurses on packing of several wounds, and consulted on a patient with a venous stasis ulcer.

“We identified an educational opportunity for the nursing staff. On the third day I brought a US certified wound care specialist and I gave a Microsoft PowerPoint presentation on venous stasis ulcers and proper wound care. The nursing staff and clinic were very receptive and asked if we would develop a patient-based educational presentation. The wound care specialist spent the afternoon giving hands-on demonstrations in the wound care clinic, and I taught technique for excisional biopsy of skin tags and moles to physicians. One of the host physicians arranged for more consultations on more of the clinic’s complicated patients, which included a staff member and a relative.”

Medical Technician (MSgt, E-7, Independent Duty Medical Technician, USAF)

“The first day I was assigned to work with the ‘auxiliaries,’ nurses working in the urgent care area at the clinic. Their urgent care area had limited equipment and supplies and included equipment such as mercury thermometers, a few stethoscopes and 1 blood pressure cuff. Their duties consisted of screening patients, starting IVs, giving injections and breathing treatments. They also had a minor surgery room where the nurses helped.

“During the observation of the placement of an IV catheter, I noticed that they were using a port and attaching a needle to the IV tubing and leaving the needle attached to the patient. I asked them about their procedure and incidents with needlesticks since they had to be pretty accurate in getting the needle through the port. The nurse stated there were a significant number of cases of needlesticks. The following day, we brought 18-g, 20-g, and 23-g IV catheters, saline locks, syringes, and our team’s junior physician and I instructed the nurses how to set up an IV without using the needle port.

“The third day at the clinic, I assisted in checking in patients (blood pressure, weight, interviews). I also helped run the immunizations clinic, assisting in giving both pediatric and adult immunizations. Since there was only 1 nurse on shift that day, we multitasked and also gave injections prescribed by the providers, such as medroxyprogesterone and dexamethasone. By far, this was the most rewarding part of the mission. I really felt as though we were part of the team and believe we truly made a difference.”

Administrator (LTC, Medical Service Corps, USN)

“I learned many items from our visit to Clinica Dr. Francisco Quintanas Area de Salud 4 Chacarita. I reviewed the business plan contained in two 1.5-inch hardbound books. Their business plan outlined the population served, projections for upcoming year, and contracts. Area 4 served 21,344 people (11,197 men and 10,147 women). The business plan reviewed historical encounter information (ie, average patient is seen 2.6 times annually, 203,285 laboratory tests were performed in 2010, no radiology capabilities) and contained metrics for key programs for upcoming year (eg, vaccinations, women wellness) that seemed similar to US Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures.

“Our partners discussed financing of the health care they provide, including money flows to and from the government, the work center, and the employees. The business plan contains contract information and costs for maintenance, utilities, personnel, and other issues that would be typical for US-based operations as well. Housekeeping, some of the secretaries, and security staff are not employees—they are contracted personnel. Money is shifted to meet unexpected needs (ie, in 2009/2010–H1N1 influenza was unanticipated). Money was taken from other programs to meet the need.

“Within the Area 4 clinics there are 94 personnel, including 15 physicians. They have a document that is similar to our Activity Manning Document, which outlines personnel billet code, name, and specialty. The Asistentes Técnicos de Atención Primaria are the personnel who conduct home visits and are a unique capability—we do not have an exact equivalent in most US health care systems. Pregnant workers are released from work 1 month prior to the due date and are expected to return to work 3 months postdelivery.”

Medical Logistics (Capt, Medical Service Corps, USAF)

“Costa Rica is still growing in aspects of national health care but has a reliable system in place it seems. Similar to many of the countries visited, it has great capacity for building, but is challenged to increase its infrastructure. In 2011, part of this was due to a recent economic decline in the nation and its health care sector. They have interaction both with other regional clinics managed under the same national health system construct (Caja Costarricense del Seguro Social) as well as with private practices and specialty services. The clinics are open only daytime business hours. Only the regional hospital is open 24/7 for emergent care.

“Supplies are distributed to the regional clinics primarily from San José (the capital and largest city), but also there are some smaller warehousing of clinical materials located around the region. One of these warehouses was in Puntarenas where our clinic was located. To get better information for future supply chain management support we would need to speak with the central distribution/suppliers of all nationalized clinic-run entities. What our partners did teach is that at a higher, national level the clinics are standardized with what they will carry and need to keep on-hand depending upon the clinic classification (ie, level 1, 2, or 3).

“Equipment is purchased similar to the DoD method: Requests are submitted toward the end of the year, the administration prioritizes the lists, and then buys what they feel is most beneficial to the clinic with the resources available. Our hosts stated that before the end of the year, it is very difficult to prioritize needs other than some of the items that they ‘always need’ because they are unlikely to receive items very low on their list. The hosts stated that they would be very interested in having a chance to receive any excess US military equipment from their priority lists if there was a mechanism to do so. In future EHET missions, advance coordination would need to occur to see if (locally compatible) equipment needs could be met through the Defense Reutilization and Marketing Office (DRMO). Alternatively, an embedded team focused on Biomedical Equipment repair could work alongside partners such as at this clinic to develop a sustainable preventive maintenance and equipment testing program. Advance coordination on equipment status would foster improvement for resourceful partner clinics such as Chacarita, with targeted involvement from US military biomedical equipment technicians.”

Discussion

These 4 firsthand accounts from a multidisciplinary, primary-care focused, EHET offers multiple preliminary evidence of the value of this small-scale embedded approach. The accounts are responses to an open-ended prompt for personal impressions and key thoughts as part of an EHET. Three of the advantages gleaned from these accounts are greater personal satisfaction, detailed insight into local operations and health systems, and deeper empathy and respect for common challenges despite health system differences compared with the US military health system.

These advantages are critical to afford the US military personnel the ability to more effectively execute engagement goals, such as meeting health needs in humanitarian assistance, advancing interoperable capacity for security cooperation, or achieving targeted training to enhance US medical operational skills. The greater personal satisfaction was evident in the team member responses that, despite mission stops in 7 prior countries, “This by far was the most rewarding part of the Continuing Promise 2011 mission” and “I hope this becomes a tool used to augment humanitarian missions.”

The descriptions by both the administrator and the logistician on the intimate details that the hosts shared with them is a testament to the rapid trust engendered by the embedded approach. There was a trust to share information as a result of acknowledged local strengths and legitimate interest in local challenges. Peer appreciation was evident; although they did not speak the same literal language, they spoke the same professional language, which was apparent even through the use of an interpreter.

A third advantage, evident from these written exchanges is a regular acknowledgement that health system issues, pursued processes, and desired outcomes are similar between different systems. There may be significant differences in actual resources and infrastructure, but some of the bureaucracy is similar. This last insight is essential to grasp in order to seek capacity building and interoperable solutions toward common goals; empathy is needed to encourage local ownership and sustainability while respecting local challenges and different problem-solving approaches and processes.

Conclusions

The EHET concept afforded deep insight by team members into ways to partner with their hosts to target better health outcomes and meaningful partnership for potential long-term geopolitical impact. Long duration embedded teams, or recurrent insertion, in a single location will achieve greater long-term benefits because of greater health system and cultural understanding. EHETs, once accepted and refined from prototype to standard employment tool, should prove to be a more effective tool in building partnerships, building capacity, and increased security cooperation by using US military resources to support legitimate health needs either in a military-military or military-civilian setting.5 These firsthand accounts provide preliminary evidence that embedded teams may be a critical and needed tool to “ensure that military health engagement is appropriate, constructive, effective, and coordinated with other actors.”6

Acknowledgments

Additional original EHET team members included LCDR Jeanne Jimenez, RN; CDR Francine Worthington, Health Administrator; Maj Tony McClung, RN; Mrs. Romero, RN of LDS Charities, and the staff of the Chacarita clinics in Costa Rica.

“Whenever possible, we will develop innovative, low-cost, and small-footprint approaches to achieve our security objectives.” 1

Team member and participant observations can deliver valuable insight into the effectiveness of an activity or project. Certainly, documentation of such qualitative assessment through survey questions or narratives can reveal important information for future action. This qualitative aspect was a significant consideration in the formation of an embedded health engagement team (EHET) intended to improve foreign assistance and health outcomes for global humanitarian and security cooperation activities.

Since health activities are centered on human interaction and relationships, some observation or qualitative assessment must be included to truly determine short-term local buy-in and long-term outcomes. The following observations include the direct narrative perspectives of team members from a multidisciplinary primary care EHET that add experiential depth to prior assessment of the pilot test of such teams during Continuing Promise 2011, a 9-country series of health engagement activities employed from the USNS Comfort.2 The embedded team consisted of US Air Force (USAF), US Navy (USN), and nongovernmental organization (NGO) personnel working directly in a primary care clinic of the Costa Rican public health system.

This is small sample of a few team members who responded to a simple, open-ended prompt to record their impression of the EHET concept and experiences. Documenting this information should highlight the importance of seeking similar qualitative mission data for future health engagements. Standardized questionnaires have been used to evaluate health activities and have provided valuable analysis and recommendations that have advanced US Department of Defense (DoD) global health engagement.3 Captured narrative observation from the EHET pilot study is a complementary qualitative method that supports the concept of small, well prepared, culturally competent, EHETs tailored to work within a partner system rather than outside of it will achieve greater mutual benefit, including the application of better, more equitable health and health system principles.4 In this embedded manner, health care professionals may readily contribute to host nation health sector plans and goals while achieving military objectives, political goals, and mutual strategic interests through both military-military and military-civilian applications.

Observations and Reflections

Family Physician (Maj, Second Physician, USAF)

“Overall, the experience I had with the embedded team was truly rewarding. I hope this becomes a tool used to augment humanitarian missions. There is no way to truly understand a systems strengths and weakness except by being embedded in the clinic or hospital. For 3 days I worked alongside a bilingual physician at a local family practice clinic. The clinic did full spectrum family practice, including prenatal care. The doctor saw between 25 and 35 patients each day plus covered urgent care during lunch. Paper charting was used although the clinic is looking into electronic records. The clinic was very efficient. All team members were very aware of their roles and did their jobs with a smile and worked well together.

“Most patient encounters took between 10 and 15 minutes although the patient might stay around for IV therapy, intramuscular pain medications, or other treatments that were carried out by the nursing staff. There was a small procedure room and procedures would be performed on the same day they were identified. The nursing staff would set up everything, and in between patients the provider would complete the procedure. On the first day I mostly shadowed, but in the afternoon, I was asked to consult on some of the more complicated patients with diabetes mellitus or hypertension. On the second day I shadowed a health care provider who did not speak English and through an interpreter he asked for my input. In the afternoon the nursing staff asked me to discuss the treatment of abscesses. I discussed techniques of incision and drainage and importance of packing and proper wound care, worked with one of their wound care nurses on packing of several wounds, and consulted on a patient with a venous stasis ulcer.

“We identified an educational opportunity for the nursing staff. On the third day I brought a US certified wound care specialist and I gave a Microsoft PowerPoint presentation on venous stasis ulcers and proper wound care. The nursing staff and clinic were very receptive and asked if we would develop a patient-based educational presentation. The wound care specialist spent the afternoon giving hands-on demonstrations in the wound care clinic, and I taught technique for excisional biopsy of skin tags and moles to physicians. One of the host physicians arranged for more consultations on more of the clinic’s complicated patients, which included a staff member and a relative.”

Medical Technician (MSgt, E-7, Independent Duty Medical Technician, USAF)

“The first day I was assigned to work with the ‘auxiliaries,’ nurses working in the urgent care area at the clinic. Their urgent care area had limited equipment and supplies and included equipment such as mercury thermometers, a few stethoscopes and 1 blood pressure cuff. Their duties consisted of screening patients, starting IVs, giving injections and breathing treatments. They also had a minor surgery room where the nurses helped.

“During the observation of the placement of an IV catheter, I noticed that they were using a port and attaching a needle to the IV tubing and leaving the needle attached to the patient. I asked them about their procedure and incidents with needlesticks since they had to be pretty accurate in getting the needle through the port. The nurse stated there were a significant number of cases of needlesticks. The following day, we brought 18-g, 20-g, and 23-g IV catheters, saline locks, syringes, and our team’s junior physician and I instructed the nurses how to set up an IV without using the needle port.

“The third day at the clinic, I assisted in checking in patients (blood pressure, weight, interviews). I also helped run the immunizations clinic, assisting in giving both pediatric and adult immunizations. Since there was only 1 nurse on shift that day, we multitasked and also gave injections prescribed by the providers, such as medroxyprogesterone and dexamethasone. By far, this was the most rewarding part of the mission. I really felt as though we were part of the team and believe we truly made a difference.”

Administrator (LTC, Medical Service Corps, USN)

“I learned many items from our visit to Clinica Dr. Francisco Quintanas Area de Salud 4 Chacarita. I reviewed the business plan contained in two 1.5-inch hardbound books. Their business plan outlined the population served, projections for upcoming year, and contracts. Area 4 served 21,344 people (11,197 men and 10,147 women). The business plan reviewed historical encounter information (ie, average patient is seen 2.6 times annually, 203,285 laboratory tests were performed in 2010, no radiology capabilities) and contained metrics for key programs for upcoming year (eg, vaccinations, women wellness) that seemed similar to US Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures.

“Our partners discussed financing of the health care they provide, including money flows to and from the government, the work center, and the employees. The business plan contains contract information and costs for maintenance, utilities, personnel, and other issues that would be typical for US-based operations as well. Housekeeping, some of the secretaries, and security staff are not employees—they are contracted personnel. Money is shifted to meet unexpected needs (ie, in 2009/2010–H1N1 influenza was unanticipated). Money was taken from other programs to meet the need.

“Within the Area 4 clinics there are 94 personnel, including 15 physicians. They have a document that is similar to our Activity Manning Document, which outlines personnel billet code, name, and specialty. The Asistentes Técnicos de Atención Primaria are the personnel who conduct home visits and are a unique capability—we do not have an exact equivalent in most US health care systems. Pregnant workers are released from work 1 month prior to the due date and are expected to return to work 3 months postdelivery.”

Medical Logistics (Capt, Medical Service Corps, USAF)

“Costa Rica is still growing in aspects of national health care but has a reliable system in place it seems. Similar to many of the countries visited, it has great capacity for building, but is challenged to increase its infrastructure. In 2011, part of this was due to a recent economic decline in the nation and its health care sector. They have interaction both with other regional clinics managed under the same national health system construct (Caja Costarricense del Seguro Social) as well as with private practices and specialty services. The clinics are open only daytime business hours. Only the regional hospital is open 24/7 for emergent care.

“Supplies are distributed to the regional clinics primarily from San José (the capital and largest city), but also there are some smaller warehousing of clinical materials located around the region. One of these warehouses was in Puntarenas where our clinic was located. To get better information for future supply chain management support we would need to speak with the central distribution/suppliers of all nationalized clinic-run entities. What our partners did teach is that at a higher, national level the clinics are standardized with what they will carry and need to keep on-hand depending upon the clinic classification (ie, level 1, 2, or 3).

“Equipment is purchased similar to the DoD method: Requests are submitted toward the end of the year, the administration prioritizes the lists, and then buys what they feel is most beneficial to the clinic with the resources available. Our hosts stated that before the end of the year, it is very difficult to prioritize needs other than some of the items that they ‘always need’ because they are unlikely to receive items very low on their list. The hosts stated that they would be very interested in having a chance to receive any excess US military equipment from their priority lists if there was a mechanism to do so. In future EHET missions, advance coordination would need to occur to see if (locally compatible) equipment needs could be met through the Defense Reutilization and Marketing Office (DRMO). Alternatively, an embedded team focused on Biomedical Equipment repair could work alongside partners such as at this clinic to develop a sustainable preventive maintenance and equipment testing program. Advance coordination on equipment status would foster improvement for resourceful partner clinics such as Chacarita, with targeted involvement from US military biomedical equipment technicians.”

Discussion

These 4 firsthand accounts from a multidisciplinary, primary-care focused, EHET offers multiple preliminary evidence of the value of this small-scale embedded approach. The accounts are responses to an open-ended prompt for personal impressions and key thoughts as part of an EHET. Three of the advantages gleaned from these accounts are greater personal satisfaction, detailed insight into local operations and health systems, and deeper empathy and respect for common challenges despite health system differences compared with the US military health system.

These advantages are critical to afford the US military personnel the ability to more effectively execute engagement goals, such as meeting health needs in humanitarian assistance, advancing interoperable capacity for security cooperation, or achieving targeted training to enhance US medical operational skills. The greater personal satisfaction was evident in the team member responses that, despite mission stops in 7 prior countries, “This by far was the most rewarding part of the Continuing Promise 2011 mission” and “I hope this becomes a tool used to augment humanitarian missions.”

The descriptions by both the administrator and the logistician on the intimate details that the hosts shared with them is a testament to the rapid trust engendered by the embedded approach. There was a trust to share information as a result of acknowledged local strengths and legitimate interest in local challenges. Peer appreciation was evident; although they did not speak the same literal language, they spoke the same professional language, which was apparent even through the use of an interpreter.

A third advantage, evident from these written exchanges is a regular acknowledgement that health system issues, pursued processes, and desired outcomes are similar between different systems. There may be significant differences in actual resources and infrastructure, but some of the bureaucracy is similar. This last insight is essential to grasp in order to seek capacity building and interoperable solutions toward common goals; empathy is needed to encourage local ownership and sustainability while respecting local challenges and different problem-solving approaches and processes.

Conclusions