User login

Beta-blockers in COPD

Airway disorders

Beta-blockers in COPD: A settled debate?

Beta-blockers are the cornerstone in the management of patients with heart failure and myocardial infarction where they have shown to improve morbidity and mortality. Cardiovascular disease is common in patients with COPD. A 2014 meta-analysis of retrospective studies involving patients with COPD using a beta-blocker has shown lower death and lower exacerbation rate (Du Q, et al. PLoS One. 2014;9[11]:e113048). More recent studies continue to note underutilization of beta-blockers in patients with COPD due to concerns for adverse effects on pulmonary function (Lipworth B, et al. Heart. 2016;102[23]:1909).

To further study these concerns, Dransfield and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial (BLOCK COPD) of 532 randomly assigned patients to receive either metoprolol or placebo (Dransfield, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381[24]:2304). Primary outcome was time to first COPD exacerbation whereas secondary outcomes included rate of exacerbation, mortality, hospitalization, symptoms, and spirometry data. Median time to exacerbation was similar between the two groups; however, metoprolol was associated with higher incidence of severe exacerbation requiring hospitalization (HR 1.91, 95% CI 1.29-2.83). There was nonstatistical increase in deaths in metoprolol group, mainly contributed by fatal COPD events (seven in metoprolol vs one in placebo). The study results validated some of the concerns of worsening pulmonary function with beta-blocker use; however, in order to better understand the study results, we must pay attention to the study cohort.

In summary, patients did not have significant cardiac disease and, therefore, did not have an overt indication for beta-blocker use. Patients with COPD in this study were sicker than average patients. Lastly, there were more patients in the metoprolol group who had COPD exacerbations requiring ED visit or hospitalization in 12 months prior to study enrollment. For the above-mentioned reasons, the conclusion of this study should not discourage the use of beta-blockers in patients with COPD when underlying cardiac disease warrants their use, after careful consideration of benefits and risks.

Muhammad Adrish, MD, FCCP, Steering Committee Member

Navitha Ramesh, MD, FCCP, Steering Committee Member

Clinical research

Nintedanib in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: Does one size really fit all?

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) include a variety of lung disorders, such as idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs), autoimmune diseases, granulomatous lung disease, and environmental diseases. They all have one thing in common—a progressive fibrosing phenotype that is almost universally fatal. It has been suggested that such diseases have a shared pathophysiologic mechanism irrespective of the cause and, hence, could respond to similar therapy. Nintedanib acts intracellularly by inhibiting multiple tyrosine kinases. Previous clinical trials have suggested that nintedanib inhibits the progression of lung fibrosis in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (Richeldi, et al. N Engl J Med. 2014;370[22]:2071) and systemic sclerosis-associated ILD (Distler, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380[26]:2518). The INBUILD trial was conducted to study the efficacy and safety of nintedanib in patients with fibrosing interstitial lung diseases (Flaherty, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381[18]:1718).

Patients with a wide spectrum of progressive fibrosing ILD were enrolled in the INBUILD trial. This gave the phenotypic approach needed to study the effects of nintedanib in fibrosing ILDs. The authors reported an absolute difference of 107 mL in the annual rate of decline in forced vital capacity in the overall population, 128.2 mL (95% CI 65.4 to 148.5; P less than .001) in patients with UIP-like fibrotic pattern and 75.3 mL in patients with other fibrotic patterns, between patients who received nintedanib and those who received placebo. Earlier studies have shown similar results in patients with IPF. The most frequent adverse event was diarrhea (66.9% in the nintedanib group and 23.9% in placebo group). Liver enzymes derangement was more common in the nintedanib group. Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, decreased appetite, and weight decrease were also more frequent in the nintedanib group than in those in the placebo group. In conclusion, this study not only explored the effects of nintedanib on progressive fibrosing ILDs but also helped to enhance the understanding of their natural history, suggesting a final common pathway toward lung fibrosis.

Mohsin Ijaz, MD, FCCP, Steering Committee Member

Critical care

Vaping-related acute lung injury: Where there’s smoke, there’s fire

E-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) is a burgeoning public health problem in the United States. There have been more than 2,506 hospitalizations and 54 deaths from EVALI (cdc.gov). Unfortunately, the diagnosis is one of exclusion at present. The CDC defines EVALI as lung disease associated with e-cigarette or vaping exposure within 90 days, infiltrates, and absence of other causes (Layden, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911614). As critical care providers, we are uniquely poised to detect and treat this illness, given that roughly 1 in 3 patients with EVALI require mechanical ventilation. Moreover, one-quarter of rehospitalizations and deaths occur 2 days after discharge from initial hospitalization (Mikosz, et al. MMWR 2020;68[5152]:1183). .

To better identify EVALI, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that health-care providers ask e-cigarette or vaping product users about respiratory, gastrointestinal, and constitutional symptoms, obtain chest imaging in those suspected of EVALI, consider outpatient management of stable patients, test for influenza, and use caution when prescribing steroids in the outpatient setting. Emphasizing cessation and advocating for annual influenza vaccination is also recommended (Update: Interim Guidance for Health Care Providers for Managing Patients with Suspected E-cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use–Associated Lung Injury. (MMWR. 2019;68[46]:1081).

So how can critical care providers assist in the understanding and treatment of EVALI? Critical care physicians treating patients with EVALI face unique challenges moving forward. We need to develop a better understanding of the triggers and pathophysiology of EVALI and learn to improve our recognition of the disease. We should study interventions that may improve outcomes such as corticosteroids. We know little about the long-term outcomes and sequalae of EVALI.

The best treatment for EVALI is prevention. Critical care physicians are experts at identifying and treating life-threatening conditions but as a community have less experience in the public health arena. If as physicians we are called upon to advocate for our patients, then perhaps there is a role for critical care physicians to advocate for a ban on vaping.

Matthew K. Hensley, MD, MPH, Fellow-in-Training

Daniel R. Ouellette, MD, MS, FCCP, NetWork Vice-Chair

Home-based mechanical ventilation and neuromuscular disease

Keeping up with the times: incorporating home mechanical ventilation education into pulmonary and critical care fellowship and clinical practice

Home mechanical ventilation (HMV) utilization for patients with chronic respiratory conditions is rapidly increasing in both pediatric and adult populations. By 2016, the estimated prevalence of HMV was 2.9-12.9/100,000 (3.1-18% via tracheotomy) (Rose, et al. Respir Care. 2015;60[5]:695; Valko, et al. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18[1]:190). In 2012 limited regional U.S. data were extrapolated to approximate a prevalence of 4.7-6.4/100,000 children utilizing HMV (King, A. Respir Care. 2012;57[6]921), but there is currently no comprehensive registry of HMV use in the United States. A U.S. Department of Health and Human Services report in 2016 described an 85-fold increase in Medicare claims for home ventilators in 2015 compared with 2009 (OEI-12-15-00370; 9/22/2016).

With increasing demand, educating clinicians responsible for providing and managing HMV is paramount. Education specific to longitudinal management of the HMV is noticeably overlooked. The ACGME core competencies for PCCM fellowships include principles inherent to HMV, including modes/principles of ventilation, modalities/principles of oxygen supplementation, tracheostomy tube management, as well as the use of “masks for delivery of supplemental oxygen, humidifiers, nebulizers, and incentive spirometry” (ACGME Common Program Requirements 7/1/2019). However, training programs are not required to provide skills essential in HMV management, including: (1) appropriate patient selection for long-term HMV, (2) selection of well-matched home ventilators suited to patients’ chronic conditions, (3) assessment/timing of transition to invasive ventilation, or (4) adjustments necessary to maintain optimal ventilator support. Life-sustaining ventilators used in ICUs differ from life-supporting HMV systems in modes, interface, cost, algorithms, circuitry, and available adjuncts.

There is an opportunity (and responsibility) to improve current training guidelines to meet growing needs of the population and anticipate needs of trainees as they enter unsupervised practice. Although simulation initiatives at national CHEST meetings attempt to bridge education gaps, it is incumbent upon fellowship training programs to prepare pulmonologists with skills to manage HMV in order to maintain high standards of care in a safe, financially responsible and evidence-based manner.

Bethany L. Lussier, MD, FCCP, NetWork Member

Won Y. Lee, MD, FCCP. Steering Committee Member

Interstitial and diffuse lung disease

Granulomatous lymphocytic interstitial lung disease (GL-ILD)

Among the granulomatous lung diseases, Gl-ILD is hardly a new discovery, but for many reasons, it often goes undiagnosed for years. The relative rareness of the disease itself and, hence, the lack of awareness makes it an uncommon differential for granulomatous ILD. Patients with GL-ILD are often misdiagnosed with sarcoidosis, unspecified ILD, or lymphoid interstitial pneumonia, etc, before receiving a diagnosis of GL-ILD.

GL-ILD is seen in 5% to 22% of patients with common variable immunoglobulin deficiency (CVID). There are instances where patients are diagnosed with CVID based on a radiologic or histologic diagnosis of GL-ILD. Although GL-ILD suggests a pulmonary process, it actually encompasses a multisystemic granulomatous inflammatory disease that may affect the liver, spleen, bowels, lymphoid tissue, and conceivably any other organ system (Hartono, et al. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118[5]:614. Pathogenesis of GL-ILD in CVID includes dysfunctional antigen handling (due to impaired T cell function) and aberrant immune response to viruses (Hurst, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5[4]:938).

Patients with GL-ILD often present with progressive shortness of breath, restrictive lung functions with a background of CVID. Imaging findings are 5-30 mm lower lobe-predominant, nodules, ground glass opacities, and splenomegaly. Histopathology varies with predominant granulomas vs lymphocytic infiltrates. The process can be treated and often reversed with use of high dose immunoglobulin replacement, immunomodulatory therapy with agents like azathioprine, and rituximab. However, steroids are not helpful. Due to the lymphocytic dysregulation in GL-ILD, patients are at high risk of death from lymphoma. Part of the management is surveillance for malignancy and involvement of other organ systems.

A. Thanushi Wynn, MD, Fellow-in-Training

Airway disorders

Beta-blockers in COPD: A settled debate?

Beta-blockers are the cornerstone in the management of patients with heart failure and myocardial infarction where they have shown to improve morbidity and mortality. Cardiovascular disease is common in patients with COPD. A 2014 meta-analysis of retrospective studies involving patients with COPD using a beta-blocker has shown lower death and lower exacerbation rate (Du Q, et al. PLoS One. 2014;9[11]:e113048). More recent studies continue to note underutilization of beta-blockers in patients with COPD due to concerns for adverse effects on pulmonary function (Lipworth B, et al. Heart. 2016;102[23]:1909).

To further study these concerns, Dransfield and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial (BLOCK COPD) of 532 randomly assigned patients to receive either metoprolol or placebo (Dransfield, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381[24]:2304). Primary outcome was time to first COPD exacerbation whereas secondary outcomes included rate of exacerbation, mortality, hospitalization, symptoms, and spirometry data. Median time to exacerbation was similar between the two groups; however, metoprolol was associated with higher incidence of severe exacerbation requiring hospitalization (HR 1.91, 95% CI 1.29-2.83). There was nonstatistical increase in deaths in metoprolol group, mainly contributed by fatal COPD events (seven in metoprolol vs one in placebo). The study results validated some of the concerns of worsening pulmonary function with beta-blocker use; however, in order to better understand the study results, we must pay attention to the study cohort.

In summary, patients did not have significant cardiac disease and, therefore, did not have an overt indication for beta-blocker use. Patients with COPD in this study were sicker than average patients. Lastly, there were more patients in the metoprolol group who had COPD exacerbations requiring ED visit or hospitalization in 12 months prior to study enrollment. For the above-mentioned reasons, the conclusion of this study should not discourage the use of beta-blockers in patients with COPD when underlying cardiac disease warrants their use, after careful consideration of benefits and risks.

Muhammad Adrish, MD, FCCP, Steering Committee Member

Navitha Ramesh, MD, FCCP, Steering Committee Member

Clinical research

Nintedanib in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: Does one size really fit all?

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) include a variety of lung disorders, such as idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs), autoimmune diseases, granulomatous lung disease, and environmental diseases. They all have one thing in common—a progressive fibrosing phenotype that is almost universally fatal. It has been suggested that such diseases have a shared pathophysiologic mechanism irrespective of the cause and, hence, could respond to similar therapy. Nintedanib acts intracellularly by inhibiting multiple tyrosine kinases. Previous clinical trials have suggested that nintedanib inhibits the progression of lung fibrosis in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (Richeldi, et al. N Engl J Med. 2014;370[22]:2071) and systemic sclerosis-associated ILD (Distler, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380[26]:2518). The INBUILD trial was conducted to study the efficacy and safety of nintedanib in patients with fibrosing interstitial lung diseases (Flaherty, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381[18]:1718).

Patients with a wide spectrum of progressive fibrosing ILD were enrolled in the INBUILD trial. This gave the phenotypic approach needed to study the effects of nintedanib in fibrosing ILDs. The authors reported an absolute difference of 107 mL in the annual rate of decline in forced vital capacity in the overall population, 128.2 mL (95% CI 65.4 to 148.5; P less than .001) in patients with UIP-like fibrotic pattern and 75.3 mL in patients with other fibrotic patterns, between patients who received nintedanib and those who received placebo. Earlier studies have shown similar results in patients with IPF. The most frequent adverse event was diarrhea (66.9% in the nintedanib group and 23.9% in placebo group). Liver enzymes derangement was more common in the nintedanib group. Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, decreased appetite, and weight decrease were also more frequent in the nintedanib group than in those in the placebo group. In conclusion, this study not only explored the effects of nintedanib on progressive fibrosing ILDs but also helped to enhance the understanding of their natural history, suggesting a final common pathway toward lung fibrosis.

Mohsin Ijaz, MD, FCCP, Steering Committee Member

Critical care

Vaping-related acute lung injury: Where there’s smoke, there’s fire

E-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) is a burgeoning public health problem in the United States. There have been more than 2,506 hospitalizations and 54 deaths from EVALI (cdc.gov). Unfortunately, the diagnosis is one of exclusion at present. The CDC defines EVALI as lung disease associated with e-cigarette or vaping exposure within 90 days, infiltrates, and absence of other causes (Layden, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911614). As critical care providers, we are uniquely poised to detect and treat this illness, given that roughly 1 in 3 patients with EVALI require mechanical ventilation. Moreover, one-quarter of rehospitalizations and deaths occur 2 days after discharge from initial hospitalization (Mikosz, et al. MMWR 2020;68[5152]:1183). .

To better identify EVALI, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that health-care providers ask e-cigarette or vaping product users about respiratory, gastrointestinal, and constitutional symptoms, obtain chest imaging in those suspected of EVALI, consider outpatient management of stable patients, test for influenza, and use caution when prescribing steroids in the outpatient setting. Emphasizing cessation and advocating for annual influenza vaccination is also recommended (Update: Interim Guidance for Health Care Providers for Managing Patients with Suspected E-cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use–Associated Lung Injury. (MMWR. 2019;68[46]:1081).

So how can critical care providers assist in the understanding and treatment of EVALI? Critical care physicians treating patients with EVALI face unique challenges moving forward. We need to develop a better understanding of the triggers and pathophysiology of EVALI and learn to improve our recognition of the disease. We should study interventions that may improve outcomes such as corticosteroids. We know little about the long-term outcomes and sequalae of EVALI.

The best treatment for EVALI is prevention. Critical care physicians are experts at identifying and treating life-threatening conditions but as a community have less experience in the public health arena. If as physicians we are called upon to advocate for our patients, then perhaps there is a role for critical care physicians to advocate for a ban on vaping.

Matthew K. Hensley, MD, MPH, Fellow-in-Training

Daniel R. Ouellette, MD, MS, FCCP, NetWork Vice-Chair

Home-based mechanical ventilation and neuromuscular disease

Keeping up with the times: incorporating home mechanical ventilation education into pulmonary and critical care fellowship and clinical practice

Home mechanical ventilation (HMV) utilization for patients with chronic respiratory conditions is rapidly increasing in both pediatric and adult populations. By 2016, the estimated prevalence of HMV was 2.9-12.9/100,000 (3.1-18% via tracheotomy) (Rose, et al. Respir Care. 2015;60[5]:695; Valko, et al. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18[1]:190). In 2012 limited regional U.S. data were extrapolated to approximate a prevalence of 4.7-6.4/100,000 children utilizing HMV (King, A. Respir Care. 2012;57[6]921), but there is currently no comprehensive registry of HMV use in the United States. A U.S. Department of Health and Human Services report in 2016 described an 85-fold increase in Medicare claims for home ventilators in 2015 compared with 2009 (OEI-12-15-00370; 9/22/2016).

With increasing demand, educating clinicians responsible for providing and managing HMV is paramount. Education specific to longitudinal management of the HMV is noticeably overlooked. The ACGME core competencies for PCCM fellowships include principles inherent to HMV, including modes/principles of ventilation, modalities/principles of oxygen supplementation, tracheostomy tube management, as well as the use of “masks for delivery of supplemental oxygen, humidifiers, nebulizers, and incentive spirometry” (ACGME Common Program Requirements 7/1/2019). However, training programs are not required to provide skills essential in HMV management, including: (1) appropriate patient selection for long-term HMV, (2) selection of well-matched home ventilators suited to patients’ chronic conditions, (3) assessment/timing of transition to invasive ventilation, or (4) adjustments necessary to maintain optimal ventilator support. Life-sustaining ventilators used in ICUs differ from life-supporting HMV systems in modes, interface, cost, algorithms, circuitry, and available adjuncts.

There is an opportunity (and responsibility) to improve current training guidelines to meet growing needs of the population and anticipate needs of trainees as they enter unsupervised practice. Although simulation initiatives at national CHEST meetings attempt to bridge education gaps, it is incumbent upon fellowship training programs to prepare pulmonologists with skills to manage HMV in order to maintain high standards of care in a safe, financially responsible and evidence-based manner.

Bethany L. Lussier, MD, FCCP, NetWork Member

Won Y. Lee, MD, FCCP. Steering Committee Member

Interstitial and diffuse lung disease

Granulomatous lymphocytic interstitial lung disease (GL-ILD)

Among the granulomatous lung diseases, Gl-ILD is hardly a new discovery, but for many reasons, it often goes undiagnosed for years. The relative rareness of the disease itself and, hence, the lack of awareness makes it an uncommon differential for granulomatous ILD. Patients with GL-ILD are often misdiagnosed with sarcoidosis, unspecified ILD, or lymphoid interstitial pneumonia, etc, before receiving a diagnosis of GL-ILD.

GL-ILD is seen in 5% to 22% of patients with common variable immunoglobulin deficiency (CVID). There are instances where patients are diagnosed with CVID based on a radiologic or histologic diagnosis of GL-ILD. Although GL-ILD suggests a pulmonary process, it actually encompasses a multisystemic granulomatous inflammatory disease that may affect the liver, spleen, bowels, lymphoid tissue, and conceivably any other organ system (Hartono, et al. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118[5]:614. Pathogenesis of GL-ILD in CVID includes dysfunctional antigen handling (due to impaired T cell function) and aberrant immune response to viruses (Hurst, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5[4]:938).

Patients with GL-ILD often present with progressive shortness of breath, restrictive lung functions with a background of CVID. Imaging findings are 5-30 mm lower lobe-predominant, nodules, ground glass opacities, and splenomegaly. Histopathology varies with predominant granulomas vs lymphocytic infiltrates. The process can be treated and often reversed with use of high dose immunoglobulin replacement, immunomodulatory therapy with agents like azathioprine, and rituximab. However, steroids are not helpful. Due to the lymphocytic dysregulation in GL-ILD, patients are at high risk of death from lymphoma. Part of the management is surveillance for malignancy and involvement of other organ systems.

A. Thanushi Wynn, MD, Fellow-in-Training

Airway disorders

Beta-blockers in COPD: A settled debate?

Beta-blockers are the cornerstone in the management of patients with heart failure and myocardial infarction where they have shown to improve morbidity and mortality. Cardiovascular disease is common in patients with COPD. A 2014 meta-analysis of retrospective studies involving patients with COPD using a beta-blocker has shown lower death and lower exacerbation rate (Du Q, et al. PLoS One. 2014;9[11]:e113048). More recent studies continue to note underutilization of beta-blockers in patients with COPD due to concerns for adverse effects on pulmonary function (Lipworth B, et al. Heart. 2016;102[23]:1909).

To further study these concerns, Dransfield and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial (BLOCK COPD) of 532 randomly assigned patients to receive either metoprolol or placebo (Dransfield, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381[24]:2304). Primary outcome was time to first COPD exacerbation whereas secondary outcomes included rate of exacerbation, mortality, hospitalization, symptoms, and spirometry data. Median time to exacerbation was similar between the two groups; however, metoprolol was associated with higher incidence of severe exacerbation requiring hospitalization (HR 1.91, 95% CI 1.29-2.83). There was nonstatistical increase in deaths in metoprolol group, mainly contributed by fatal COPD events (seven in metoprolol vs one in placebo). The study results validated some of the concerns of worsening pulmonary function with beta-blocker use; however, in order to better understand the study results, we must pay attention to the study cohort.

In summary, patients did not have significant cardiac disease and, therefore, did not have an overt indication for beta-blocker use. Patients with COPD in this study were sicker than average patients. Lastly, there were more patients in the metoprolol group who had COPD exacerbations requiring ED visit or hospitalization in 12 months prior to study enrollment. For the above-mentioned reasons, the conclusion of this study should not discourage the use of beta-blockers in patients with COPD when underlying cardiac disease warrants their use, after careful consideration of benefits and risks.

Muhammad Adrish, MD, FCCP, Steering Committee Member

Navitha Ramesh, MD, FCCP, Steering Committee Member

Clinical research

Nintedanib in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: Does one size really fit all?

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) include a variety of lung disorders, such as idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs), autoimmune diseases, granulomatous lung disease, and environmental diseases. They all have one thing in common—a progressive fibrosing phenotype that is almost universally fatal. It has been suggested that such diseases have a shared pathophysiologic mechanism irrespective of the cause and, hence, could respond to similar therapy. Nintedanib acts intracellularly by inhibiting multiple tyrosine kinases. Previous clinical trials have suggested that nintedanib inhibits the progression of lung fibrosis in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (Richeldi, et al. N Engl J Med. 2014;370[22]:2071) and systemic sclerosis-associated ILD (Distler, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380[26]:2518). The INBUILD trial was conducted to study the efficacy and safety of nintedanib in patients with fibrosing interstitial lung diseases (Flaherty, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381[18]:1718).

Patients with a wide spectrum of progressive fibrosing ILD were enrolled in the INBUILD trial. This gave the phenotypic approach needed to study the effects of nintedanib in fibrosing ILDs. The authors reported an absolute difference of 107 mL in the annual rate of decline in forced vital capacity in the overall population, 128.2 mL (95% CI 65.4 to 148.5; P less than .001) in patients with UIP-like fibrotic pattern and 75.3 mL in patients with other fibrotic patterns, between patients who received nintedanib and those who received placebo. Earlier studies have shown similar results in patients with IPF. The most frequent adverse event was diarrhea (66.9% in the nintedanib group and 23.9% in placebo group). Liver enzymes derangement was more common in the nintedanib group. Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, decreased appetite, and weight decrease were also more frequent in the nintedanib group than in those in the placebo group. In conclusion, this study not only explored the effects of nintedanib on progressive fibrosing ILDs but also helped to enhance the understanding of their natural history, suggesting a final common pathway toward lung fibrosis.

Mohsin Ijaz, MD, FCCP, Steering Committee Member

Critical care

Vaping-related acute lung injury: Where there’s smoke, there’s fire

E-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) is a burgeoning public health problem in the United States. There have been more than 2,506 hospitalizations and 54 deaths from EVALI (cdc.gov). Unfortunately, the diagnosis is one of exclusion at present. The CDC defines EVALI as lung disease associated with e-cigarette or vaping exposure within 90 days, infiltrates, and absence of other causes (Layden, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911614). As critical care providers, we are uniquely poised to detect and treat this illness, given that roughly 1 in 3 patients with EVALI require mechanical ventilation. Moreover, one-quarter of rehospitalizations and deaths occur 2 days after discharge from initial hospitalization (Mikosz, et al. MMWR 2020;68[5152]:1183). .

To better identify EVALI, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that health-care providers ask e-cigarette or vaping product users about respiratory, gastrointestinal, and constitutional symptoms, obtain chest imaging in those suspected of EVALI, consider outpatient management of stable patients, test for influenza, and use caution when prescribing steroids in the outpatient setting. Emphasizing cessation and advocating for annual influenza vaccination is also recommended (Update: Interim Guidance for Health Care Providers for Managing Patients with Suspected E-cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use–Associated Lung Injury. (MMWR. 2019;68[46]:1081).

So how can critical care providers assist in the understanding and treatment of EVALI? Critical care physicians treating patients with EVALI face unique challenges moving forward. We need to develop a better understanding of the triggers and pathophysiology of EVALI and learn to improve our recognition of the disease. We should study interventions that may improve outcomes such as corticosteroids. We know little about the long-term outcomes and sequalae of EVALI.

The best treatment for EVALI is prevention. Critical care physicians are experts at identifying and treating life-threatening conditions but as a community have less experience in the public health arena. If as physicians we are called upon to advocate for our patients, then perhaps there is a role for critical care physicians to advocate for a ban on vaping.

Matthew K. Hensley, MD, MPH, Fellow-in-Training

Daniel R. Ouellette, MD, MS, FCCP, NetWork Vice-Chair

Home-based mechanical ventilation and neuromuscular disease

Keeping up with the times: incorporating home mechanical ventilation education into pulmonary and critical care fellowship and clinical practice

Home mechanical ventilation (HMV) utilization for patients with chronic respiratory conditions is rapidly increasing in both pediatric and adult populations. By 2016, the estimated prevalence of HMV was 2.9-12.9/100,000 (3.1-18% via tracheotomy) (Rose, et al. Respir Care. 2015;60[5]:695; Valko, et al. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18[1]:190). In 2012 limited regional U.S. data were extrapolated to approximate a prevalence of 4.7-6.4/100,000 children utilizing HMV (King, A. Respir Care. 2012;57[6]921), but there is currently no comprehensive registry of HMV use in the United States. A U.S. Department of Health and Human Services report in 2016 described an 85-fold increase in Medicare claims for home ventilators in 2015 compared with 2009 (OEI-12-15-00370; 9/22/2016).

With increasing demand, educating clinicians responsible for providing and managing HMV is paramount. Education specific to longitudinal management of the HMV is noticeably overlooked. The ACGME core competencies for PCCM fellowships include principles inherent to HMV, including modes/principles of ventilation, modalities/principles of oxygen supplementation, tracheostomy tube management, as well as the use of “masks for delivery of supplemental oxygen, humidifiers, nebulizers, and incentive spirometry” (ACGME Common Program Requirements 7/1/2019). However, training programs are not required to provide skills essential in HMV management, including: (1) appropriate patient selection for long-term HMV, (2) selection of well-matched home ventilators suited to patients’ chronic conditions, (3) assessment/timing of transition to invasive ventilation, or (4) adjustments necessary to maintain optimal ventilator support. Life-sustaining ventilators used in ICUs differ from life-supporting HMV systems in modes, interface, cost, algorithms, circuitry, and available adjuncts.

There is an opportunity (and responsibility) to improve current training guidelines to meet growing needs of the population and anticipate needs of trainees as they enter unsupervised practice. Although simulation initiatives at national CHEST meetings attempt to bridge education gaps, it is incumbent upon fellowship training programs to prepare pulmonologists with skills to manage HMV in order to maintain high standards of care in a safe, financially responsible and evidence-based manner.

Bethany L. Lussier, MD, FCCP, NetWork Member

Won Y. Lee, MD, FCCP. Steering Committee Member

Interstitial and diffuse lung disease

Granulomatous lymphocytic interstitial lung disease (GL-ILD)

Among the granulomatous lung diseases, Gl-ILD is hardly a new discovery, but for many reasons, it often goes undiagnosed for years. The relative rareness of the disease itself and, hence, the lack of awareness makes it an uncommon differential for granulomatous ILD. Patients with GL-ILD are often misdiagnosed with sarcoidosis, unspecified ILD, or lymphoid interstitial pneumonia, etc, before receiving a diagnosis of GL-ILD.

GL-ILD is seen in 5% to 22% of patients with common variable immunoglobulin deficiency (CVID). There are instances where patients are diagnosed with CVID based on a radiologic or histologic diagnosis of GL-ILD. Although GL-ILD suggests a pulmonary process, it actually encompasses a multisystemic granulomatous inflammatory disease that may affect the liver, spleen, bowels, lymphoid tissue, and conceivably any other organ system (Hartono, et al. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118[5]:614. Pathogenesis of GL-ILD in CVID includes dysfunctional antigen handling (due to impaired T cell function) and aberrant immune response to viruses (Hurst, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5[4]:938).

Patients with GL-ILD often present with progressive shortness of breath, restrictive lung functions with a background of CVID. Imaging findings are 5-30 mm lower lobe-predominant, nodules, ground glass opacities, and splenomegaly. Histopathology varies with predominant granulomas vs lymphocytic infiltrates. The process can be treated and often reversed with use of high dose immunoglobulin replacement, immunomodulatory therapy with agents like azathioprine, and rituximab. However, steroids are not helpful. Due to the lymphocytic dysregulation in GL-ILD, patients are at high risk of death from lymphoma. Part of the management is surveillance for malignancy and involvement of other organ systems.

A. Thanushi Wynn, MD, Fellow-in-Training

Psoriasis ointment helped with itch, healing in phase 2 EB study

LONDON – , in a small, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study.

More importantly, use of the ointment promoted wound healing in those with the severe skin-blistering condition. Indeed, compared with placebo, a greater reduction in wound size was observed after 2 weeks when the ointment was applied (a mean reduction of 65.5% vs. 88.4%; P less than .006). However, at 1 month, no significant differences were seen in the size of the wounds between the two treatment arms.

“Calcipotriol is a vitamin D analog and it is well known that vitamin D is a very critical factor for skin homeostasis and proper wound healing,” Christina Guttmann-Gruber, PhD, said at the EB World Congress, organized by the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Association (DEBRA). Dr. Guttmann-Gruber, a group lead researcher for EB House Austria, which is based at the Salzburg (Austria) University Clinic for Dermatology, noted that vitamin D also helps with tissue repair and immune modulation, and enhances local antimicrobial activity.

During an oral poster presentation at the meeting, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber explained that in previous in vitro studies, it was found that low concentrations (100 nmol) of calcipotriol inhibited proliferation of RDEB tumor cells (Sci Rep. 2018 Sep 7;8:13430). Calcipotriol (also known as calcipotriene) also was found to improve the expression of antimicrobial peptides and promote wound closure. “Therefore, we thought that applying calcipotriol at the site of injury, on chronic wounds prone to superinfection where it is needed, might be beneficial for our patients.”

She and her associates designed a two-arm, randomized, double-blind crossover study to assess the effects of an existing calcipotriol-containing ointment on wound healing in patients with RDEB. The ointment used in the study is approved for treating psoriasis but was adapted by the in-house pharmacy team to reduce the concentration of calcipotriol to about 0.05 mcg/g, or around 121 nmol. The reason for the reduction was that, at higher doses, keratinocyte proliferation was reduced, which would be detrimental in RDEB patients.

Nine patients were included in the study and were randomized to either apply 1 g of the active or placebo ointment to each of two designated wounds, of at least 6 cm2 in size, every day for 4 weeks. A 2-month washout period then followed before the groups switched to use the other ointment for 1 month. Six out of the nine patients completed both treatment phases. The reasons for the patients not completing both intervention phases were not related to the drug.

Calcipotriol treatment resulted in a significant and steady reduction in itch over the entire course of treatment, which was not seen among those on placebo, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber observed. The reduction in itch was “striking,” but only while the treatment was being used, she said. Results for pain were less clear, with a significant reduction in pain after 2 weeks seen only in the placebo group, while both treatments reduced pain to the same degree by 1 month.

No serious adverse events were observed at any time point and topical use of the low-dose calcipotriol did not significantly change serum levels of calcium or vitamin D in the two patients in which this was studied, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber said.

“This is an approved drug; it’s used in psoriasis, but at a very high concentration. We were able to use it off label and make a diluted version,” she observed. “Any pharmacy can do it.” Although it was applied topically, it could be done by applying it to the dressing rather directly onto the wounded skin, she said.

Data on the skin microbiome response to treatment were also collected but were not available to analyze in time for presentation, but it appeared that there was improvement with the low-dose calcipotriol treatment, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber said. “When the wounds are healing, the microbial flora is improving.”

The next step will probably be to plan a multicenter trial of this treatment, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber said in an interview. The questions is whether such a trial would get the financial backing it needed, but if an orphan drug designation could be obtained for calcipotriol for EB, then it would be possible to conduct such a trial.

The study was funded by DEBRA Austria. The presenting author, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber, had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Guttmann-Gruber C et al. EB World Congress 2020. Poster 34.

LONDON – , in a small, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study.

More importantly, use of the ointment promoted wound healing in those with the severe skin-blistering condition. Indeed, compared with placebo, a greater reduction in wound size was observed after 2 weeks when the ointment was applied (a mean reduction of 65.5% vs. 88.4%; P less than .006). However, at 1 month, no significant differences were seen in the size of the wounds between the two treatment arms.

“Calcipotriol is a vitamin D analog and it is well known that vitamin D is a very critical factor for skin homeostasis and proper wound healing,” Christina Guttmann-Gruber, PhD, said at the EB World Congress, organized by the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Association (DEBRA). Dr. Guttmann-Gruber, a group lead researcher for EB House Austria, which is based at the Salzburg (Austria) University Clinic for Dermatology, noted that vitamin D also helps with tissue repair and immune modulation, and enhances local antimicrobial activity.

During an oral poster presentation at the meeting, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber explained that in previous in vitro studies, it was found that low concentrations (100 nmol) of calcipotriol inhibited proliferation of RDEB tumor cells (Sci Rep. 2018 Sep 7;8:13430). Calcipotriol (also known as calcipotriene) also was found to improve the expression of antimicrobial peptides and promote wound closure. “Therefore, we thought that applying calcipotriol at the site of injury, on chronic wounds prone to superinfection where it is needed, might be beneficial for our patients.”

She and her associates designed a two-arm, randomized, double-blind crossover study to assess the effects of an existing calcipotriol-containing ointment on wound healing in patients with RDEB. The ointment used in the study is approved for treating psoriasis but was adapted by the in-house pharmacy team to reduce the concentration of calcipotriol to about 0.05 mcg/g, or around 121 nmol. The reason for the reduction was that, at higher doses, keratinocyte proliferation was reduced, which would be detrimental in RDEB patients.

Nine patients were included in the study and were randomized to either apply 1 g of the active or placebo ointment to each of two designated wounds, of at least 6 cm2 in size, every day for 4 weeks. A 2-month washout period then followed before the groups switched to use the other ointment for 1 month. Six out of the nine patients completed both treatment phases. The reasons for the patients not completing both intervention phases were not related to the drug.

Calcipotriol treatment resulted in a significant and steady reduction in itch over the entire course of treatment, which was not seen among those on placebo, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber observed. The reduction in itch was “striking,” but only while the treatment was being used, she said. Results for pain were less clear, with a significant reduction in pain after 2 weeks seen only in the placebo group, while both treatments reduced pain to the same degree by 1 month.

No serious adverse events were observed at any time point and topical use of the low-dose calcipotriol did not significantly change serum levels of calcium or vitamin D in the two patients in which this was studied, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber said.

“This is an approved drug; it’s used in psoriasis, but at a very high concentration. We were able to use it off label and make a diluted version,” she observed. “Any pharmacy can do it.” Although it was applied topically, it could be done by applying it to the dressing rather directly onto the wounded skin, she said.

Data on the skin microbiome response to treatment were also collected but were not available to analyze in time for presentation, but it appeared that there was improvement with the low-dose calcipotriol treatment, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber said. “When the wounds are healing, the microbial flora is improving.”

The next step will probably be to plan a multicenter trial of this treatment, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber said in an interview. The questions is whether such a trial would get the financial backing it needed, but if an orphan drug designation could be obtained for calcipotriol for EB, then it would be possible to conduct such a trial.

The study was funded by DEBRA Austria. The presenting author, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber, had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Guttmann-Gruber C et al. EB World Congress 2020. Poster 34.

LONDON – , in a small, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study.

More importantly, use of the ointment promoted wound healing in those with the severe skin-blistering condition. Indeed, compared with placebo, a greater reduction in wound size was observed after 2 weeks when the ointment was applied (a mean reduction of 65.5% vs. 88.4%; P less than .006). However, at 1 month, no significant differences were seen in the size of the wounds between the two treatment arms.

“Calcipotriol is a vitamin D analog and it is well known that vitamin D is a very critical factor for skin homeostasis and proper wound healing,” Christina Guttmann-Gruber, PhD, said at the EB World Congress, organized by the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Association (DEBRA). Dr. Guttmann-Gruber, a group lead researcher for EB House Austria, which is based at the Salzburg (Austria) University Clinic for Dermatology, noted that vitamin D also helps with tissue repair and immune modulation, and enhances local antimicrobial activity.

During an oral poster presentation at the meeting, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber explained that in previous in vitro studies, it was found that low concentrations (100 nmol) of calcipotriol inhibited proliferation of RDEB tumor cells (Sci Rep. 2018 Sep 7;8:13430). Calcipotriol (also known as calcipotriene) also was found to improve the expression of antimicrobial peptides and promote wound closure. “Therefore, we thought that applying calcipotriol at the site of injury, on chronic wounds prone to superinfection where it is needed, might be beneficial for our patients.”

She and her associates designed a two-arm, randomized, double-blind crossover study to assess the effects of an existing calcipotriol-containing ointment on wound healing in patients with RDEB. The ointment used in the study is approved for treating psoriasis but was adapted by the in-house pharmacy team to reduce the concentration of calcipotriol to about 0.05 mcg/g, or around 121 nmol. The reason for the reduction was that, at higher doses, keratinocyte proliferation was reduced, which would be detrimental in RDEB patients.

Nine patients were included in the study and were randomized to either apply 1 g of the active or placebo ointment to each of two designated wounds, of at least 6 cm2 in size, every day for 4 weeks. A 2-month washout period then followed before the groups switched to use the other ointment for 1 month. Six out of the nine patients completed both treatment phases. The reasons for the patients not completing both intervention phases were not related to the drug.

Calcipotriol treatment resulted in a significant and steady reduction in itch over the entire course of treatment, which was not seen among those on placebo, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber observed. The reduction in itch was “striking,” but only while the treatment was being used, she said. Results for pain were less clear, with a significant reduction in pain after 2 weeks seen only in the placebo group, while both treatments reduced pain to the same degree by 1 month.

No serious adverse events were observed at any time point and topical use of the low-dose calcipotriol did not significantly change serum levels of calcium or vitamin D in the two patients in which this was studied, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber said.

“This is an approved drug; it’s used in psoriasis, but at a very high concentration. We were able to use it off label and make a diluted version,” she observed. “Any pharmacy can do it.” Although it was applied topically, it could be done by applying it to the dressing rather directly onto the wounded skin, she said.

Data on the skin microbiome response to treatment were also collected but were not available to analyze in time for presentation, but it appeared that there was improvement with the low-dose calcipotriol treatment, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber said. “When the wounds are healing, the microbial flora is improving.”

The next step will probably be to plan a multicenter trial of this treatment, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber said in an interview. The questions is whether such a trial would get the financial backing it needed, but if an orphan drug designation could be obtained for calcipotriol for EB, then it would be possible to conduct such a trial.

The study was funded by DEBRA Austria. The presenting author, Dr. Guttmann-Gruber, had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Guttmann-Gruber C et al. EB World Congress 2020. Poster 34.

REPORTING FROM EB 2020

Pharmacologic prophylaxis fails in pediatric migraine

Clinicians hoped that medications used in adults – such as antidepressants, antiepileptics, antihypertensive agents, calcium channel blockers, and food supplements – would find similar success in children. Unfortunately, researchers found only short-term signs of efficacy over placebo, with no benefit lasting more than 6 months.

The study, conducted by a team led by Cosima Locher, PhD, of Boston Children’s Hospital, included 23 double-blind, randomized, controlled trials with a total of 2,217 patients; the mean age was 11 years. They compared 12 pharmacologic agents with each other or with placebo in the study, published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

In a main efficacy analysis that included 19 studies, only two treatments outperformed placebo: propranolol (standardized mean difference, 0.60; 95% confidence interval, 0.03-1.17) and topiramate (SMD, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.03-1.15). There were no statistically significant between-treatment differences.

The results had an overall low to moderate certainty.

When propranolol was compared to placebo, the 95% prediction interval (–0.62 to 1.82) was wider than the significant confidence interval (0.03-1.17), and comprised both beneficial and detrimental effects. A similar result was found with topiramate, with a prediction interval of –0.62 to 1.80 extending into nonsignificant effects (95% CI, 0.03-1.15). In both cases, significant effects were found only when the prediction interval was 70%.

In a long-term analysis (greater than 6 months), no treatment outperformed placebo.

The treatments generally were acceptable. The researchers found no significant difference in tolerability between any of the treatments and each other or placebo. Safety data analyzed from 13 trials revealed no significant differences between treatments and placebo.

“Because specific effects of drugs are associated with the size of the placebo effect, the lack of drug efficacy in our NMA [network meta-analysis] could be owing to a comparatively high placebo effect in children. In fact, there is indirect evidence [from other studies] that the placebo effect is more pronounced in children and adolescents than in adults,” Dr. Locher and associates said. They suggested that studies were needed to quantify the placebo effect in pediatric migraine, and if it was large, to develop innovative therapies making use of this.

The findings should lead to some changes in practice, Boris Zernikow, MD, PhD, of Children’s and Adolescents’ Hospital Datteln (Germany) wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Pharmacological prophylactic treatment of childhood migraine should be an exception rather than the rule, and nonpharmacologic approaches should be emphasized, particularly because the placebo effect is magnified in children, he said.

Many who suffer migraines in childhood will continue to be affected in adulthood, so pediatric intervention is a good opportunity to instill effective strategies. These include: using abortive medication early in an attack and using antimigraine medications for only that specific type of headache; engaging in physical activity to reduce migraine attacks; getting sufficient sleep; and learning relaxation and other psychological approaches to counter migraines.

Dr. Zernikow had no relevant financial disclosures. One study author received grants from Amgen and other support from Grunenthal and Akelos. The study received funding from the Sara Page Mayo Endowment for Pediatric Pain Research, Education, and Treatment; the Swiss National Science Foundation; the Schweizer-Arau-Foundation; and the Theophrastus Foundation.

SOURCES: Locher C et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5856; Zernikow B. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5907.

Clinicians hoped that medications used in adults – such as antidepressants, antiepileptics, antihypertensive agents, calcium channel blockers, and food supplements – would find similar success in children. Unfortunately, researchers found only short-term signs of efficacy over placebo, with no benefit lasting more than 6 months.

The study, conducted by a team led by Cosima Locher, PhD, of Boston Children’s Hospital, included 23 double-blind, randomized, controlled trials with a total of 2,217 patients; the mean age was 11 years. They compared 12 pharmacologic agents with each other or with placebo in the study, published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

In a main efficacy analysis that included 19 studies, only two treatments outperformed placebo: propranolol (standardized mean difference, 0.60; 95% confidence interval, 0.03-1.17) and topiramate (SMD, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.03-1.15). There were no statistically significant between-treatment differences.

The results had an overall low to moderate certainty.

When propranolol was compared to placebo, the 95% prediction interval (–0.62 to 1.82) was wider than the significant confidence interval (0.03-1.17), and comprised both beneficial and detrimental effects. A similar result was found with topiramate, with a prediction interval of –0.62 to 1.80 extending into nonsignificant effects (95% CI, 0.03-1.15). In both cases, significant effects were found only when the prediction interval was 70%.

In a long-term analysis (greater than 6 months), no treatment outperformed placebo.

The treatments generally were acceptable. The researchers found no significant difference in tolerability between any of the treatments and each other or placebo. Safety data analyzed from 13 trials revealed no significant differences between treatments and placebo.

“Because specific effects of drugs are associated with the size of the placebo effect, the lack of drug efficacy in our NMA [network meta-analysis] could be owing to a comparatively high placebo effect in children. In fact, there is indirect evidence [from other studies] that the placebo effect is more pronounced in children and adolescents than in adults,” Dr. Locher and associates said. They suggested that studies were needed to quantify the placebo effect in pediatric migraine, and if it was large, to develop innovative therapies making use of this.

The findings should lead to some changes in practice, Boris Zernikow, MD, PhD, of Children’s and Adolescents’ Hospital Datteln (Germany) wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Pharmacological prophylactic treatment of childhood migraine should be an exception rather than the rule, and nonpharmacologic approaches should be emphasized, particularly because the placebo effect is magnified in children, he said.

Many who suffer migraines in childhood will continue to be affected in adulthood, so pediatric intervention is a good opportunity to instill effective strategies. These include: using abortive medication early in an attack and using antimigraine medications for only that specific type of headache; engaging in physical activity to reduce migraine attacks; getting sufficient sleep; and learning relaxation and other psychological approaches to counter migraines.

Dr. Zernikow had no relevant financial disclosures. One study author received grants from Amgen and other support from Grunenthal and Akelos. The study received funding from the Sara Page Mayo Endowment for Pediatric Pain Research, Education, and Treatment; the Swiss National Science Foundation; the Schweizer-Arau-Foundation; and the Theophrastus Foundation.

SOURCES: Locher C et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5856; Zernikow B. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5907.

Clinicians hoped that medications used in adults – such as antidepressants, antiepileptics, antihypertensive agents, calcium channel blockers, and food supplements – would find similar success in children. Unfortunately, researchers found only short-term signs of efficacy over placebo, with no benefit lasting more than 6 months.

The study, conducted by a team led by Cosima Locher, PhD, of Boston Children’s Hospital, included 23 double-blind, randomized, controlled trials with a total of 2,217 patients; the mean age was 11 years. They compared 12 pharmacologic agents with each other or with placebo in the study, published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

In a main efficacy analysis that included 19 studies, only two treatments outperformed placebo: propranolol (standardized mean difference, 0.60; 95% confidence interval, 0.03-1.17) and topiramate (SMD, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.03-1.15). There were no statistically significant between-treatment differences.

The results had an overall low to moderate certainty.

When propranolol was compared to placebo, the 95% prediction interval (–0.62 to 1.82) was wider than the significant confidence interval (0.03-1.17), and comprised both beneficial and detrimental effects. A similar result was found with topiramate, with a prediction interval of –0.62 to 1.80 extending into nonsignificant effects (95% CI, 0.03-1.15). In both cases, significant effects were found only when the prediction interval was 70%.

In a long-term analysis (greater than 6 months), no treatment outperformed placebo.

The treatments generally were acceptable. The researchers found no significant difference in tolerability between any of the treatments and each other or placebo. Safety data analyzed from 13 trials revealed no significant differences between treatments and placebo.

“Because specific effects of drugs are associated with the size of the placebo effect, the lack of drug efficacy in our NMA [network meta-analysis] could be owing to a comparatively high placebo effect in children. In fact, there is indirect evidence [from other studies] that the placebo effect is more pronounced in children and adolescents than in adults,” Dr. Locher and associates said. They suggested that studies were needed to quantify the placebo effect in pediatric migraine, and if it was large, to develop innovative therapies making use of this.

The findings should lead to some changes in practice, Boris Zernikow, MD, PhD, of Children’s and Adolescents’ Hospital Datteln (Germany) wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Pharmacological prophylactic treatment of childhood migraine should be an exception rather than the rule, and nonpharmacologic approaches should be emphasized, particularly because the placebo effect is magnified in children, he said.

Many who suffer migraines in childhood will continue to be affected in adulthood, so pediatric intervention is a good opportunity to instill effective strategies. These include: using abortive medication early in an attack and using antimigraine medications for only that specific type of headache; engaging in physical activity to reduce migraine attacks; getting sufficient sleep; and learning relaxation and other psychological approaches to counter migraines.

Dr. Zernikow had no relevant financial disclosures. One study author received grants from Amgen and other support from Grunenthal and Akelos. The study received funding from the Sara Page Mayo Endowment for Pediatric Pain Research, Education, and Treatment; the Swiss National Science Foundation; the Schweizer-Arau-Foundation; and the Theophrastus Foundation.

SOURCES: Locher C et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5856; Zernikow B. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5907.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

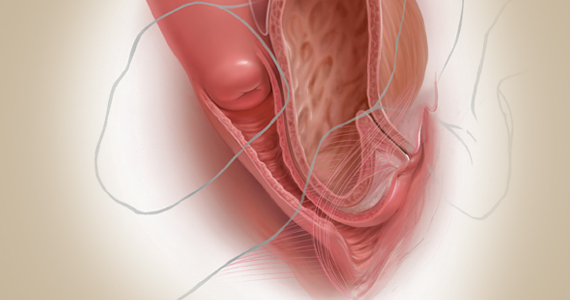

Exploring options for POP treatment: Patient selection, surgical approaches, and ways to manage risks

A number of presentations at the 2019 Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (PAGS) Symposium (Las Vegas, Nevada, December 12-14, 2019) focused on pelvic organ prolapse (POP) repair, including anatomic considerations, the evolution of surgical procedures, and transvaginal repair. OBG M

Nonsurgical approaches for POP: A good option for the right patient

John B. Gebhart, MD, MS: What are the nonsurgical options for POP?

Mark D. Walters, MD: Women who have prolapse could, of course, choose to continue to live with the prolapse. If they desire treatment, however, the main nonsurgical option is a combination of pessary use, possibly with some estrogen, and possibly with pelvic muscle exercises. Women who have a well-fitting pessary can be managed satisfactorily for years. If possible, women should be taught to take the pessary in and out on a regular basis to minimize their long-term complications.

Dr. Gebhart: How can nonsurgical treatment options be maximized?

Beri M. Ridgeway, MD: It depends on patient commitment. This is important to assess at the first visit when you are making management decisions, because if someone is not going to attend physical therapy or not going to continue to do the exercises, the expectation for the outcome is not going to be great.

Also, if a patient feels very uncomfortable using a pessary and really does not want it, I am fine proceeding with surgery as a first-line treatment. If the patient is committed, the ideal is to educate her and connect her with the right people, either a pelvic floor physical therapist or someone in your office who will encourage her and manage pessary use.

Dr. Gebhart: It goes back to assessing patient goals and expectations.

Mickey M. Karram, MD: If you have a patient who is a good candidate for a pessary—say she has a well-supported distal vagina and maybe a cervical prolapse or an apical prolapse—and you can fit a small pessary that will sit in the upper vagina in a comfortable fashion, it is worthwhile to explain to the patient that she is a really good candidate for this option. By contrast, someone who has a wide genital hiatus and a large rectocele will not have good success with a pessary.

Dr. Gebhart: That is important: Choose your nonsurgical patients well, those who will respond to therapy and maybe not get frustrated with it.

Dr. Walters: A problem I see is that some people are good at fitting a pessary, but they do not teach how to use it very well. When I see the patient back, she says, “What’s my long term on the pessary?” I say, “If we teach you to take it in and out, you are less likely to have any problems with it, and then you can manage it for years that way. Otherwise, you have to keep visiting a practitioner to change it and that is not necessarily a good long-term option.” At the very first visit, I teach them what a pessary is, its purpose, and how to maintain it themselves. I think that gives patients the best chance for long-term satisfaction.

Dr. Gebhart: Surgery is always an option if pessary management is not satisfactory.

Dr. Ridgeway: I also tell patients, especially those uncertain about using a pessary, “Worst case, you spend a little time to figure this out, but if it works, you can avoid surgery. If it doesn’t—the risks are very low and you perhaps wasted some time—but at least you’ll know you tried the conservative management.”

Dr. Gebhart: Mickey made an excellent point earlier that it can be a diagnostic treatment strategy as well.

Dr. Karram: If you are concerned about the prolapse worsening or negatively impacting a functional problem related to the bladder or bowel, it is good to place a pessary for a short period of time. This can potentially give you an idea of how your surgery will impact a patient’s bladder or bowel function.

Continue to: Decisions to make before choosing a surgical approach...

Decisions to make before choosing a surgical approach

Dr. Gebhart: Would you elaborate on the surgical options for managing POP?

Dr. Walters: For women with prolapse who decide they want to have surgery, the woman and the surgeon need to make a number of decisions. Some of these include whether the uterus, if present, needs to be removed; whether the woman would like to maintain sexual function or not; whether the repair would best be done vaginally only with native tissue suturing, vaginally with some augmentation (although that is not likely in the United States at this time), or through the abdomen, usually laparoscopically or robotically with a mesh-augmented sacrocolpopexy repair.

Also, we must decide whether to do additional cystocele and rectocele repairs and whether to add slings for stress incontinence, which can coexist or could develop after the prolapse repair. A lot of different decisions need to be made when choosing a prolapse repair for different women.

Dr. Ridgeway: It is shared decision-making with the patient. You need to understand her goals, the degree of prolapse, whether she has contraindications to uterine preservation, and how much risk she is willing to take.

Fundamentals of the clinical evaluation

Dr. Gebhart: For a woman who wants to manage her prolapse surgically, let us consider some fundamentals of clinical diagnosis. Take me through your office evaluation of the patient reporting prolapse symptoms—her history, yes, but from a physical exam standpoint, what is important?

Dr. Karram: You want to know if this is a primary prolapse or recurrent prolapse. You want to distinguish the various segments of the pelvic floor that are prolapsing and try to quantitate that in whatever way you would like. A standardized quantification system is useful, but you should have a system within your practice that you can standardize. Then, determine if there are coexisting functional derangements and how those are being impacted by the prolapse, because that is very important.

Take a good history, and identify how badly the prolapse bothers the patient and affects her quality of life. Understand how much she is willing to do about it. Does she just want to know what it is and has no interest in a surgical intervention, versus something she definitely wants to get corrected? Then do whatever potential testing around the bladder, and bowel, based on any functional derangements and finally determine interest in maintaining sexual function. Once all this information is obtained, a detailed discussion of surgical options can be undertaken.

Dr. Gebhart: What are your clinical pearls for a patient who has prolapse and does not describe any incontinence, voiding dysfunction, or defecatory symptoms? Do we need imaging testing of any sort or is the physical exam adequate for assessing prolapse?

Dr. Walters: When you do the standardized examination of the prolapse, it is important to measure how much prolapse affects the anterior wall of the apex and/or cervix and the posterior wall. Then note that in your notes and plan your surgery accordingly.

It is useful to have the patient fully bear down and then make your measurements; then, especially if she has a full bladder, have her cough while you hold up the prolapse with a speculum or your hand to see if she has stress urinary incontinence.

Continue to: I agree that to diagnose prolapse...

Dr. Ridgeway: I agree that to diagnose prolapse, it is physical exam alone. I would not recommend any significant testing other than testing for the potential for stress incontinence.

Dr. Gebhart: Is it necessary to use the POP-Q (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification system) in a nonacademic private practice setting? Or are other systems, like a Baden-Walker scoring system, adequate in the everyday practice of the experienced generalist?

Dr. Walters: The Baden-Walker system actually is adequate for use in everyday practice. However, Baden-Walker is an outdated measurement system that really is not taught anymore. I think that as older physicians finish and newer doctors come in, no one will even know what Baden-Walker is.

It is better to go ahead and start learning the POP-Q system. Everyone has electronic charts now and if you learn to use the POP-Q, you can do it very quickly and get a grading system for your chart that is reproducible for everyone.

Dr. Ridgeway: The most important thing is to assess all 3 compartments and document the amount of prolapse of each compartment. A modified POP-Q is often adequate. To do this, perform a split speculum exam and use the hymen as the reference. Zero is at the hymen, +1 is 1 cm beyond the hyman. Covering the rectum, how much does the anterior compartment prolapse in reference to the hymen? Covering the anterior compartment, get an idea of what is happening posteriorly. And the crux of any decision in my mind is what is happening at the apex or to the uterus/cervix if it is still present. It is really important to document at least those 3 compartments.

Dr. Karram: I agree. The POP-Q is the ideal, but I don’t think generalists are motivated to use it. It is very important, though, to have some anatomic landmarks, as already mentioned by Dr. Ridgeway.

Choose a surgical approach based on the clinical situation

Dr. Gebhart: How do you choose the surgical approach for someone with prolapse?

Dr. Karram: Most surgeons do what they think they do best. I have spent the majority of my career operating through the vagina, and most of that involves native tissue repairs. I almost always will do a primary prolapse through the vagina and not consider augmentation except in rare circumstances. A recurrent prolapse, a prolapsed shortened vagina, scarring, or a situation that is not straightforward has to be individualized. My basic intervention initially is almost always vaginally with native tissue.

Dr. Ridgeway: For a primary prolapse repair, I also will almost always use native tissue repair as firstline. Whether that is with hysterectomy or without, most people in the long term do very well with that. At least 70% of my repairs are done with a native tissue approach.

For a woman who has a significant prolapse posthysterectomy, especially of the anterior wall or with recurrent prolapse, I offer a laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. The only other time I offer that as a primary approach would be for a younger woman with very significant prolapse. In that case, I will review risks and benefits with the patient and, using shared decision-making, offer either a native tissue repair or a sacrocolpopexy. For that patient, no matter what you do, given that she has many years to live, the chances are that she will likely need a second intervention.

Dr. Gebhart: Mark, how do you choose an approach for prolapse?

Dr. Walters: I do things pretty much the way Dr. Karram and Dr. Ridgeway do. For women who have a primary prolapse, I usually take a vaginal approach, and for recurrences I frequently do sacrocolpopexy with mesh or I refer to one of my partners who does more laparoscopic or robotic sacrocolpopexy.

Whether the patient needs a hysterectomy or not is evolving. Traditionally, hysterectomy is almost always done at the first prolapse repair. That is being reassessed in the United States to match what is happening in some other countries. It is possible to do nice primary prolapse repair vaginally or laparoscopically and leave the uterus in, in selected women who desire that.

Continue to: Transvaginal prolapse repair: Mesh is no longer an option...

Transvaginal prolapse repair: Mesh is no longer an option

Dr. Gebhart: What led up to the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) market removal of mesh for transvaginal repair of POP?

Dr. Ridgeway: To clarify, it was not a recall—a word that many people use—it was an order to stop producing and distributing surgical mesh intended for transvaginal repair of POP.1 There is a very long history. Transvaginal mesh was introduced with the goal of improving prolapse anatomic and subjective outcomes. Over the last 13 years or so, there were adverse events that led to FDA public health notifications. Consequently, these devices were reclassified, and now require additional testing prior to approval. The newest transvaginal mesh kits were studied.

These 522 studies were completed recently and needed to show superior outcomes because, historically, the risks associated with transvaginal mesh compared to those associated with native tissue repairs are higher: higher reoperation rates, higher rates of other complications, and very minimal improvements in subjective and objective outcomes. Data were presented to the FDA, and it was deemed that these mesh kits did not improve outcomes significantly compared with native tissue repairs.

Dr. Karram: Beri, you stated that very accurately. The pro-mesh advocates were taken back by the idea that the FDA made this recommendation without allowing the outcomes to be followed longer.

Dr. Gebhart: My understanding is that the FDA had a timeline where they had to do a report and the studies had not matured to that end point; thus, they had to go with the data they had even though the studies were not completed. I think they are requesting that they be completed.

Dr. Ridgeway: Additional data will be available, some through the 522 studies, others through randomized controlled trials in which patients were already enrolled and had surgery. As far as I know, I do not think that the decision will be reversed.

Continue to: Native tissue repair and failure risk...

Native tissue repair and failure risk

Dr. Gebhart: I hear a lot that native tissue repairs fail. Mickey, as you do a lot of vaginal surgery, what are your thoughts? Should you use augmentation of some sort because native tissue fails?

Dr. Karram: There is going to be a failure rate with whatever surgery you do. I think that the failure rate with native tissue is somewhat overstated. I think a lot of that dates back to some of the things that were being promoted by mesh advocates. Initially, there was a lot of cherry-picking of native tissue data in some of those studies to promote the idea that the recurrent prolapse rates were 40% to 80%. We certainly do not see that in our patient population.

Based on our 5-year data, we have a recurrence rate of about 15% and a reoperation rate of less than 10%. That is the best I can quote based on our data. We have not followed patients longer than 5 years.

I can’t do much better than that with an augmentation; even if I get another 5% or 10% better anatomic outcome, that will be at the expense of some erosions and other complications specific to the mesh. I do think that the native tissue failure rate being promoted by a lot of individuals is a higher failure rate than what we are seeing.

Dr. Gebhart: What do you think, Mark?

Dr. Walters: Large cohort studies both at your institution, Mayo Clinic, and ours at the Cleveland Clinic mirror what Dr. Karram said, in that we have a reoperation rate somewhere between 8% and 15%. Of course, we have some failures that are stage 2 failures where patients choose not to have another operation. In general, a 10% or 12% reoperation rate at 5 to 7 years is acceptable.

Native tissue repairs probably fail at the apex a little more than mesh sacrocolpopexy. Mesh sacrocolpopexy, depending on what else you do with that operation, may have more distal vaginal failures, rates like distal rectoceles and more de novo stress urinary incontinence than we probably get with native tissue. I get some failures of the apex with native tissue repairs, but I am okay with using sacrocolpopexy as the second-line therapy in those patients.

Hysteropexy technique and pros and cons

Dr. Gebhart: Is hysteropexy a fad, or is there something to this?

Dr. Ridgeway: I do not think it is a fad. Women do feel strongly about this, and we now have data supporting this choice: randomized controlled trials of hysterectomy and prolapse repair versus hysteropexy with comparable outcomes at the short and medium term.2

The outcomes are similar, but as we said, outcomes for all prolapse repair types are not perfect. We have recurrences with sacrocolpopexy, native tissue repair, and hysteropexy. We need more data on types of hysteropexy and long-term outcomes for uterine preservation.

Dr. Walters: We have been discussing what patients think of their uterus, and some patients have very strong opinions. Some prefer to have a hysterectomy because then they don’t need to worry about cancer or do screening for cancer, and they are very happy with that. Other women with the same kind of prolapse prefer not to have a hysterectomy because philosophically they think they are better off keeping their organs. Since satisfaction is an outcome, it is useful to know what the patient wants and what she thinks about the surgical procedure.

Dr. Gebhart: For hysteropexy, do the data show that suture or a mesh augment provide an advantage one way or the other? Do we know that yet?

Dr. Walters: No, there are not enough studies with suture. There are only a few very good studies with suture hysteropexy, and they are mostly sacrospinous suture hysteropexies. Only a few studies look at mesh hysteropexy (with the Uphold device that was put on hold), or with variations of uterosacral support using strips of mesh, mostly done in other countries.

A point I want to add, if native tissue repairs fail at the apex more, why don’t you just always do sacrocolpopexy? One reason is because it might have a little higher complication rate due to the abdominal access and the fact that you are putting mesh in. If you have, for example, a 4% complication rate with the mesh but you get a better cure rate, those things balance out, and the woman may not be that much better off because of the extra complications. You have to assess the pro and con with each patient to pick what is best for her—either a more durable repair with a mesh or a little safer repair with native tissue.

Continue to: Women feel very strongly about risk...