User login

Subungual Hemorrhage From an Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitor

To the Editor:

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway plays a role in the differentiation, proliferation, and survival of several cell types.1 Erlotinib is an EGFR inhibitor that targets aberrant cells that overexpress this receptor and has been used in the treatment of various solid malignant tumors.2,3 Common dermatologic side effects associated with EGFR inhibitors include papulopustular rash, xeroderma, and paronychia.2,3 We present a unique finding of subungual hemorrhage of the thumbnails in a patient taking erlotinib.

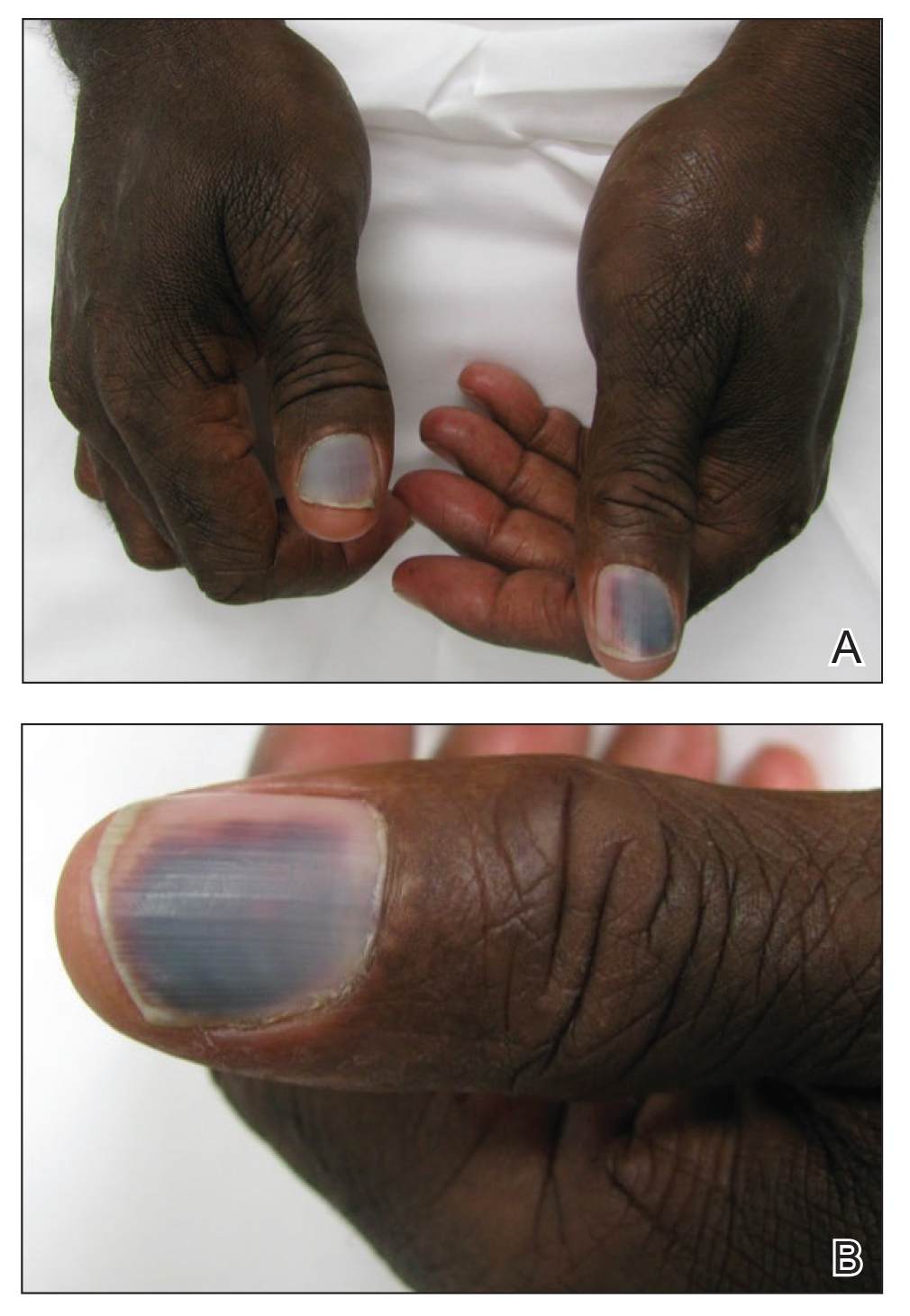

A 50-year-old man presented with acute-onset tenderness and discoloration of the thumbnails of 1 week’s duration. There was no preceding trauma or history of similar symptoms. His medical history was notable for recurrent lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR L858R mutation. Erlotinib therapy was initiated 5 weeks prior to symptom onset. He developed notable xeroderma of the palms and soles that preceded nail changes by a few days. He completed treatment with carboplatin and pemetrexed 16 months prior to relapse after paclitaxel failed due to a severe allergic reaction. There were no nail symptoms during that time. The patient did not have a documented coagulation disorder and was not on any known medications that would predispose him to bleeding. Physical examination demonstrated subungual hemorrhage of the thumbnails with tenderness on palpation (Figure). There was no evidence of periungual changes or nail plate abnormality. All other nails appeared normal. Laboratory test results showed normal platelets. Supportive therapeutic measures were recommended, and the patient was advised to avoid trauma to the nails.

Nail toxicities reported with EGFR inhibitors include paronychia, periungual pyogenic granulomas, and ingrown nails.1-3 Inflammation of the nail bed also can lead to secondary nail changes, such as onychodystrophy or onycholysis.2 Subungual hemorrhage has been reported as a side effect of taxanes, anticoagulants, anthracyclines, anti-inflammatory agents, and retinoids.4,5

The pathogenesis of nail toxicity secondary to EGFR inhibitors is not entirely clear. Symptoms commonly occur several weeks to months after therapy initiation.6 Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors disrupt proliferation and promote apoptosis of keratinocytes that is thought to enhance fragility of the periungual skin and nail plate.1,3 Under the influence of EGFR inhibition, a proinflammatory microenvironment in the skin is created through a type I interferon response leading to tissue damage.7 These changes may predispose patients to develop subungual hemorrhage in response to repeated nail microtrauma. Subungual asymptomatic splinter hemorrhage is a nail finding described in patients treated with the multikinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib. Splinter hemorrhages of the nails are thought to be secondary to capillary microinjuries of the digits that cannot be repaired due to inhibition of vascular EGFRs.4

The time course of erlotinib administration and the simultaneous onset of xeroderma, a known side effect of the drug, in our patient are consistent with other cases.6 Subungual hemorrhage, which the patient reported observing only days after the onset of xeroderma, provides increased support that the anti-EGFR medication was likely responsible for both side effects concurrently. Bilateral involvement of the thumbs makes trauma as an inciting event unlikely.

Incidence of nail changes secondary to anti-EGFR drugs are likely underestimated and underreported.3 Subungual hemorrhage should be considered as an additional, less common nail side effect of EGFR inhibitors that clinicians and patients may encounter. Improved awareness and understanding of nail toxicities associated with EGFR inhibitors may offer better insight into the pathogenesis of these side effects and management options.

- Piraccini BM, Alessandrini A. Drug-related nail disease. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:618-626.

- Kiyohara Y, Yamazaki N, Kishi A. Erlotinib-related skin toxicities: treatment strategies in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:463-472.

- Minisini AM, Tosti A, Sobrero AF, et al. Taxane-induced nail changes: incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;333-337.

- Garden BC, Wu S, Lacouture ME. The risk of nail changes with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:400-408.

- Fox LP. Nail toxicity associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:460-465.

- Chen KL, Lin CC, Cho YT, et al. Comparison of skin toxic effects associated with gefitinib, erlotinib or afatinib treatment for non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:340-342.

- Lulli D, Carbone ML, Pastore S. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors trigger a type I interferon response in human skin. Oncotarget. 2016;7:47777-47793.

To the Editor:

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway plays a role in the differentiation, proliferation, and survival of several cell types.1 Erlotinib is an EGFR inhibitor that targets aberrant cells that overexpress this receptor and has been used in the treatment of various solid malignant tumors.2,3 Common dermatologic side effects associated with EGFR inhibitors include papulopustular rash, xeroderma, and paronychia.2,3 We present a unique finding of subungual hemorrhage of the thumbnails in a patient taking erlotinib.

A 50-year-old man presented with acute-onset tenderness and discoloration of the thumbnails of 1 week’s duration. There was no preceding trauma or history of similar symptoms. His medical history was notable for recurrent lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR L858R mutation. Erlotinib therapy was initiated 5 weeks prior to symptom onset. He developed notable xeroderma of the palms and soles that preceded nail changes by a few days. He completed treatment with carboplatin and pemetrexed 16 months prior to relapse after paclitaxel failed due to a severe allergic reaction. There were no nail symptoms during that time. The patient did not have a documented coagulation disorder and was not on any known medications that would predispose him to bleeding. Physical examination demonstrated subungual hemorrhage of the thumbnails with tenderness on palpation (Figure). There was no evidence of periungual changes or nail plate abnormality. All other nails appeared normal. Laboratory test results showed normal platelets. Supportive therapeutic measures were recommended, and the patient was advised to avoid trauma to the nails.

Nail toxicities reported with EGFR inhibitors include paronychia, periungual pyogenic granulomas, and ingrown nails.1-3 Inflammation of the nail bed also can lead to secondary nail changes, such as onychodystrophy or onycholysis.2 Subungual hemorrhage has been reported as a side effect of taxanes, anticoagulants, anthracyclines, anti-inflammatory agents, and retinoids.4,5

The pathogenesis of nail toxicity secondary to EGFR inhibitors is not entirely clear. Symptoms commonly occur several weeks to months after therapy initiation.6 Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors disrupt proliferation and promote apoptosis of keratinocytes that is thought to enhance fragility of the periungual skin and nail plate.1,3 Under the influence of EGFR inhibition, a proinflammatory microenvironment in the skin is created through a type I interferon response leading to tissue damage.7 These changes may predispose patients to develop subungual hemorrhage in response to repeated nail microtrauma. Subungual asymptomatic splinter hemorrhage is a nail finding described in patients treated with the multikinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib. Splinter hemorrhages of the nails are thought to be secondary to capillary microinjuries of the digits that cannot be repaired due to inhibition of vascular EGFRs.4

The time course of erlotinib administration and the simultaneous onset of xeroderma, a known side effect of the drug, in our patient are consistent with other cases.6 Subungual hemorrhage, which the patient reported observing only days after the onset of xeroderma, provides increased support that the anti-EGFR medication was likely responsible for both side effects concurrently. Bilateral involvement of the thumbs makes trauma as an inciting event unlikely.

Incidence of nail changes secondary to anti-EGFR drugs are likely underestimated and underreported.3 Subungual hemorrhage should be considered as an additional, less common nail side effect of EGFR inhibitors that clinicians and patients may encounter. Improved awareness and understanding of nail toxicities associated with EGFR inhibitors may offer better insight into the pathogenesis of these side effects and management options.

To the Editor:

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway plays a role in the differentiation, proliferation, and survival of several cell types.1 Erlotinib is an EGFR inhibitor that targets aberrant cells that overexpress this receptor and has been used in the treatment of various solid malignant tumors.2,3 Common dermatologic side effects associated with EGFR inhibitors include papulopustular rash, xeroderma, and paronychia.2,3 We present a unique finding of subungual hemorrhage of the thumbnails in a patient taking erlotinib.

A 50-year-old man presented with acute-onset tenderness and discoloration of the thumbnails of 1 week’s duration. There was no preceding trauma or history of similar symptoms. His medical history was notable for recurrent lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR L858R mutation. Erlotinib therapy was initiated 5 weeks prior to symptom onset. He developed notable xeroderma of the palms and soles that preceded nail changes by a few days. He completed treatment with carboplatin and pemetrexed 16 months prior to relapse after paclitaxel failed due to a severe allergic reaction. There were no nail symptoms during that time. The patient did not have a documented coagulation disorder and was not on any known medications that would predispose him to bleeding. Physical examination demonstrated subungual hemorrhage of the thumbnails with tenderness on palpation (Figure). There was no evidence of periungual changes or nail plate abnormality. All other nails appeared normal. Laboratory test results showed normal platelets. Supportive therapeutic measures were recommended, and the patient was advised to avoid trauma to the nails.

Nail toxicities reported with EGFR inhibitors include paronychia, periungual pyogenic granulomas, and ingrown nails.1-3 Inflammation of the nail bed also can lead to secondary nail changes, such as onychodystrophy or onycholysis.2 Subungual hemorrhage has been reported as a side effect of taxanes, anticoagulants, anthracyclines, anti-inflammatory agents, and retinoids.4,5

The pathogenesis of nail toxicity secondary to EGFR inhibitors is not entirely clear. Symptoms commonly occur several weeks to months after therapy initiation.6 Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors disrupt proliferation and promote apoptosis of keratinocytes that is thought to enhance fragility of the periungual skin and nail plate.1,3 Under the influence of EGFR inhibition, a proinflammatory microenvironment in the skin is created through a type I interferon response leading to tissue damage.7 These changes may predispose patients to develop subungual hemorrhage in response to repeated nail microtrauma. Subungual asymptomatic splinter hemorrhage is a nail finding described in patients treated with the multikinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib. Splinter hemorrhages of the nails are thought to be secondary to capillary microinjuries of the digits that cannot be repaired due to inhibition of vascular EGFRs.4

The time course of erlotinib administration and the simultaneous onset of xeroderma, a known side effect of the drug, in our patient are consistent with other cases.6 Subungual hemorrhage, which the patient reported observing only days after the onset of xeroderma, provides increased support that the anti-EGFR medication was likely responsible for both side effects concurrently. Bilateral involvement of the thumbs makes trauma as an inciting event unlikely.

Incidence of nail changes secondary to anti-EGFR drugs are likely underestimated and underreported.3 Subungual hemorrhage should be considered as an additional, less common nail side effect of EGFR inhibitors that clinicians and patients may encounter. Improved awareness and understanding of nail toxicities associated with EGFR inhibitors may offer better insight into the pathogenesis of these side effects and management options.

- Piraccini BM, Alessandrini A. Drug-related nail disease. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:618-626.

- Kiyohara Y, Yamazaki N, Kishi A. Erlotinib-related skin toxicities: treatment strategies in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:463-472.

- Minisini AM, Tosti A, Sobrero AF, et al. Taxane-induced nail changes: incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;333-337.

- Garden BC, Wu S, Lacouture ME. The risk of nail changes with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:400-408.

- Fox LP. Nail toxicity associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:460-465.

- Chen KL, Lin CC, Cho YT, et al. Comparison of skin toxic effects associated with gefitinib, erlotinib or afatinib treatment for non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:340-342.

- Lulli D, Carbone ML, Pastore S. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors trigger a type I interferon response in human skin. Oncotarget. 2016;7:47777-47793.

- Piraccini BM, Alessandrini A. Drug-related nail disease. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:618-626.

- Kiyohara Y, Yamazaki N, Kishi A. Erlotinib-related skin toxicities: treatment strategies in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:463-472.

- Minisini AM, Tosti A, Sobrero AF, et al. Taxane-induced nail changes: incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;333-337.

- Garden BC, Wu S, Lacouture ME. The risk of nail changes with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:400-408.

- Fox LP. Nail toxicity associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:460-465.

- Chen KL, Lin CC, Cho YT, et al. Comparison of skin toxic effects associated with gefitinib, erlotinib or afatinib treatment for non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:340-342.

- Lulli D, Carbone ML, Pastore S. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors trigger a type I interferon response in human skin. Oncotarget. 2016;7:47777-47793.

Practice Points

- Subungual hemorrhage is a potential adverse side effect of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors.

- Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition may lead to enhanced fragility of the periungual skin and nail plate as well as a proinflammatory microenvironment in the skin, predisposing patients to nail toxicity.

Clinical Psychiatry News welcomes new board member

Clinical Psychiatry News is pleased to welcome Alice W. Lee, MD, to its editorial advisory board.

Dr. Lee, who works with children, adolescents and adults, specializes in integrative and holistic psychiatry. In her private practice in Gaithersburg, Md., she integrates functional/orthomolecular medicine and mind–body/energy medicine in her work with patients.

In addition, Dr. Lee is a Reiki master who integrates the biochemistry of chemistry with the quantum physics of healing. One of her specialties is helping patients withdraw from their psychiatric medications safely.

Dr. Lee is a member of the Academy of Integrative Health & Medicine, the Association for Comprehensive Energy Psychology, the Integrative Healthcare Symposium, and the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine.

Clinical Psychiatry News is pleased to welcome Alice W. Lee, MD, to its editorial advisory board.

Dr. Lee, who works with children, adolescents and adults, specializes in integrative and holistic psychiatry. In her private practice in Gaithersburg, Md., she integrates functional/orthomolecular medicine and mind–body/energy medicine in her work with patients.

In addition, Dr. Lee is a Reiki master who integrates the biochemistry of chemistry with the quantum physics of healing. One of her specialties is helping patients withdraw from their psychiatric medications safely.

Dr. Lee is a member of the Academy of Integrative Health & Medicine, the Association for Comprehensive Energy Psychology, the Integrative Healthcare Symposium, and the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine.

Clinical Psychiatry News is pleased to welcome Alice W. Lee, MD, to its editorial advisory board.

Dr. Lee, who works with children, adolescents and adults, specializes in integrative and holistic psychiatry. In her private practice in Gaithersburg, Md., she integrates functional/orthomolecular medicine and mind–body/energy medicine in her work with patients.

In addition, Dr. Lee is a Reiki master who integrates the biochemistry of chemistry with the quantum physics of healing. One of her specialties is helping patients withdraw from their psychiatric medications safely.

Dr. Lee is a member of the Academy of Integrative Health & Medicine, the Association for Comprehensive Energy Psychology, the Integrative Healthcare Symposium, and the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine.

Nonuremic Calciphylaxis Triggered by Rapid Weight Loss and Hypotension

Calciphylaxis, otherwise known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is characterized by calcification of the tunica media of the small- to medium-sized blood vessels of the dermis and subcutis, leading to ischemia and necrosis.1 It is a deadly disease with a 1-year mortality rate of more than 50%.2 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is the most common risk factor for calciphylaxis, with a prevalence of 1% to 4% of hemodialysis patients with calciphylaxis in the United States.2-5 However, nonuremic calciphylaxis (NUC) has been increasingly reported in the literature and has risk factors other than ESRD, including but not limited to obesity, alcoholic liver disease, primary hyperparathyroidism, connective tissue disease, and underlying malignancy.3,6-9 Triggers for calciphylaxis in at-risk patients include use of corticosteroids or warfarin, iron or albumin infusions, and rapid weight loss.3,6,9-11 We report an unusual case of NUC that most likely was triggered by rapid weight loss and hypotension in a patient with multiple risk factors for calciphylaxis.

Case Report

A 75-year-old white woman with history of morbid obesity (body mass index, 40 kg/m2), unexplained weight loss of 70 lb over the last year, and polymyalgia rheumatica requiring chronic prednisone therapy presented with painful lesions on the thighs, buttocks, and right shoulder of 4 months’ duration. She had multiple hospital admissions preceding the onset of lesions for severe infections resulting in sepsis with hypotension, including Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase bacteremia, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Physical examination revealed large well-demarcated ulcers and necrotic eschars with surrounding violaceous induration and stellate erythema on the anterior, medial, and posterior thighs and buttocks that were exquisitely tender (Figures 1 and 2).

Notable laboratory results included hypoalbuminemia (1.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.5–5.0 g/dL]) with normal renal function, a corrected calcium level of 9.7 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL), a serum phosphorus level of 3.5 mg/dL (reference range, 2.3–4.7 mg/dL), a calcium-phosphate product of 27.3 mg2/dL2 (reference range, <55 mg2/dL2), and a parathyroid hormone level of 49.3 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL). Antinuclear antibodies were negative. A hypercoagulability evaluation showed normal protein C and S levels, negative lupus anticoagulant, and negative anticardiolipin antibodies.

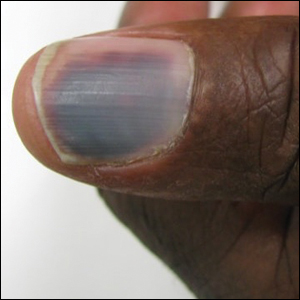

Telescoping punch biopsies of the indurated borders of the eschars showed prominent calcification of the small- and medium-sized vessels in the mid and deep dermis, intravascular thrombi, and necrosis of the epidermis and subcutaneous fat consistent with calciphylaxis (Figure 3).

After the diagnosis of calciphylaxis was made, the patient was treated with intravenous sodium thiosulfate 25 mg 3 times weekly and alendronate 70 mg weekly. Daily arterial blood gas studies did not detect metabolic acidosis during the patient’s sodium thiosulfate therapy. The wounds were debrided, and we attempted to slowly taper the patient off the oral prednisone. Unfortunately, her condition slowly deteriorated secondary to sepsis, resulting in septic shock. The patient died 3 weeks after the diagnosis of calciphylaxis was made. At the time of diagnosis, the patient had a poor prognosis and notable risk for sepsis due to the large eschars on the thighs and abdomen as well as her relative immunosuppression due to chronic prednisone use.

Comment

Background on Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis is a rare but deadly disease that affects both ESRD patients receiving dialysis and patients without ESRD who have known risk factors for calciphylaxis, including female gender, white race, obesity, alcoholic liver disease, primary hyperparathyroidism, connective tissue disease, underlying malignancy, protein C or S deficiency, corticosteroid use, warfarin use, diabetes, iron or albumin infusions, and rapid weight loss.3,6-9,11 Although the molecular pathogenesis of calciphylaxis is not completely understood, it is believed to be caused by local deposition of calcium in the tunica media of small- to medium-sized arterioles and venules in the skin.12 This deposition leads to intimal proliferation and progressive narrowing of the vessels with resultant thrombosis, ischemia, and necrosis. The cutaneous manifestations and histopathology of calciphylaxis classically follow its pathogenesis. Calciphylaxis typically presents with livedo reticularis as vessels narrow and then progresses to purpura, bullae, necrosis, and eschar formation with the onset of acute thrombosis and ischemia. Histopathology is characterized by small- and medium-sized vessel calcification and thrombus, dermal necrosis, and septal panniculitis, though the histology can be highly variable.12 Unfortunately, the already poor prognosis for calciphylaxis worsens when lesions become either ulcerative or present on the proximal extremities and trunk.4,13 Sepsis is the leading cause of death in calciphylaxis patients, affecting more than 50% of patients.2,3,14 The differential diagnoses for calciphylactic-appearing lesions include warfarin-induced skin necrosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, pyoderma gangrenosum, cholesterol emboli, and various vasculitides and coagulopathies.

Risk Factors

Our case demonstrates the importance of risk factor minimization, trigger avoidance, and early intervention due to the high mortality rate of calciphylaxis. Selye et al15 coined the term calciphylaxis in 1961 based on experiments that induced calciphylaxis in rat models. Their research concluded that there were certain sensitizers (ie, risk factors) that predisposed patients to medial calcium deposition in blood vessels and other challengers (ie, triggers) that acted as inciting events to calcium deposition. Our patient presented with multiple known risk factors for calciphylaxis, including obesity (body mass index, 40 kg/m2), female gender, white race, hypoalbuminemia, and chronic corticosteroid use.16 In the presence of a milieu of risk factors, the patient’s rapid weight loss and episodes of hypotension likely were triggers for calciphylaxis.

Other case reports in the literature have suggested weight loss as a trigger for NUC. One morbidly obese patient with inactive rheumatoid arthritis had onset of calciphylaxis lesions after unintentional weight loss of approximately 50% body weight in 1 year17; however, the weight loss does not have to be drastic to trigger calciphylaxis. Another study of 16 patients with uremic calciphylaxis found that 7 of 16 (44%) patients lost 10 to 50 kg in the 6 months prior to calciphylaxis onset.14 One proposed mechanism by Munavalli et al10 is that elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinases during catabolic weight loss states enhance the deposition of calcium into elastic fibers of small vessels. The authors found elevated serum levels of matrix metalloproteinases in their patients with NUC induced by rapid weight loss.10

A meta-analysis by Nigwekar et al3 found a history of prior corticosteroid use in 61% (22/36) of NUC cases reviewed. However, it is unclear whether it is the use of corticosteroids or chronic inflammation that is implicated in NUC pathogenesis. Chronic inflammation causes downregulation of anticalcification signaling pathways.18-20 The role of 2 vascular calcification inhibitors has been evaluated in the pathogenesis of calciphylaxis: fetuin-A and matrix gla protein (MGP).21 The activity of these proteins is decreased not only in calciphylaxis but also in other inflammatory states and chronic renal failure.18-20 One study found lower fetuin-A levels in 312 hemodialysis patients compared to healthy controls and an association between low fetuin-A levels and increased C-reactive protein levels.22 Reduced fetuin-A and MGP levels may be the result of several calciphylaxis risk factors. Warfarin is believed to trigger calciphylaxis via inhibition of gamma-carboxylation of MGP, which is necessary for its anticalcification activity.23 Hypoalbuminemia and alcoholic liver disease also are risk factors that may be explained by the fact that fetuin-A is synthesized in the liver.24 Therefore, liver disease results in decreased production of fetuin-A that is permissive to vascular calcification in calciphylaxis patients.

There have been other reports of calciphylaxis patients who were originally hospitalized due to hypotension, which may serve as a trigger for calciphylaxis onset.25 Because calciphylaxis lesions are more likely to occur in the fatty areas of the abdomen and proximal thighs where blood flow is slower, hypotension likely accentuates the slowing of blood flow and subsequent blood vessel calcification. This theory is supported by studies showing that established calciphylactic lesions worsen more quickly in the presence of systemic hypotension.26 One patient with ESRD and calciphylaxis of the breasts had consistent systolic blood pressure readings in the high 60s to low 70s between dialysis sessions.27 Due to this association, we recommend that patients with calciphylaxis have close blood pressure monitoring to aid in preventing disease progression.28

Management

Calciphylaxis treatment has not yet been standardized, as it is an uncommon disease whose pathogenesis is not fully understood. Current management strategies aim to normalize metabolic abnormalities such as hypercalcemia if they are present and remove inciting agents such as warfarin and corticosteroids.29 Other medical treatments that have been successfully used include sodium thiosulfate, oral steroids, and adjunctive bisphosphonates.29-31 Sodium thiosulfate is known to cause metabolic acidosis by generating thiosulfuric acid in vivo in patients with or without renal disease; therefore, patients on sodium thiosulfate therapy should be monitored for development of metabolic acidosis and treated with oral sodium bicarbonate or dialysis as needed.30,32 Wound care also is an important element of calciphylaxis treatment; however, the debridement of wounds is controversial. Some argue that dry intact eschars serve to protect against sepsis, which is the leading cause of death in calciphylaxis.2,14,33 In contrast, a retrospective study of 63 calciphylaxis patients found a 1-year survival rate of 61.6% in 17 patients receiving wound debridement vs 27.4% in 46 patients who did not.2 The current consensus is that debridement should be considered on a case-by-case basis, factoring in the presence of wound infection, size of wounds, stability of eschars, and treatment goals of the patient.34 Future studies should be aimed at this issue, with special focus on how these factors and the decision to debride or not impact patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Calciphylaxis is a potentially fatal disease that impacts both patients with ESRD and those with nonuremic risk factors. The term calcific uremic arteriolopathy should be disregarded, as nonuremic causes are being reported with increased frequency in the literature. In such cases, patients often have multiple risk factors, including obesity, primary hyperparathyroidism, alcoholic liver disease, and underlying malignancy, among others. Certain triggers for onset of calciphylaxis should be avoided in at-risk patients, including the use of corticosteroids or warfarin; iron and albumin infusions; hypotension; and rapid weight loss. Our fatal case of NUC is a reminder to dermatologists treating at-risk patients to avoid these triggers and to keep calciphylaxis in the differential diagnosis when encountering early lesions such as livedo reticularis, as progression of these lesions has a 1-year mortality rate of more than 50% with the therapies being utilized at this time.

- Au S, Crawford RI. Three-dimensional analysis of a calciphylaxis plaque: clues to pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;47:53-57.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, et al. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:569-579.

- Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, et al. Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1139-1143.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2210-2217.

- Angelis M, Wong LL, Myers SA, et al. Calciphylaxis in patients on hemodialysis: a prevalence study. Surgery. 1997;122:1083-1090.

- Chavel SM, Taraszka KS, Schaffer JV, et al. Calciphylaxis associated with acute, reversible renal failure in the setting of alcoholic cirrhosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:125-128.

- Bosler DS, Amin MB, Gulli F, et al. Unusual case of calciphylaxis associated with metastatic breast carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:400-403.

- Buxtorf K, Cerottini JP, Panizzon RG. Lower limb skin ulcerations, intravascular calcifications and sensorimotor polyneuropathy: calciphylaxis as part of a hyperparathyroidism? Dermatology. 1999;198:423-425.

- Brouns K, Verbeken E, Degreef H, et al. Fatal calciphylaxis in two patients with giant cell arteritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:836-840.

- Munavalli G, Reisenauer A, Moses M, et al. Weight loss-induced calciphylaxis: potential role of matrix metalloproteinases. J Dermatol. 2003;30:915-919.

- Bae GH, Nambudiri VE, Bach DQ, et al. Rapidly progressive nonuremic calciphylaxis in setting of warfarin. Am J Med. 2015;128:E19-E21.

- Essary LR, Wick MR. Cutaneous calciphylaxis. an underrecognized clinicopathologic entity. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:280-287.

- Hafner J, Keusch G, Wahl C, et al. Uremic small-artery disease with medial calcification and intimal hyperplasia (so-called calciphylaxis): a complication of chronic renal failure and benefit from parathyroidectomy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:954-962.

- Coates T, Kirkland GS, Dymock RB, et al. Cutaneous necrosis from calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:384-391.

- Selye H, Gentile G, Prioreschi P. Cutaneous molt induced by calciphylaxis in the rat. Science. 1961;134:1876-1877.

- Kalajian AH, Malhotra PS, Callen JP, et al. Calciphylaxis with normal renal and parathyroid function: not as rare as previously believed. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:451-458.

- Malabu U, Roberts L, Sangla K. Calciphylaxis in a morbidly obese woman with rheumatoid arthritis presenting with severe weight loss and vitamin D deficiency. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:104-108.

- Schäfer C, Heiss A, Schwarz A, et al. The serum protein alpha 2–Heremans-Schmid glycoprotein/fetuin-A is a systemically acting inhibitor of ectopic calcification. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:357-366.

- Cozzolino M, Galassi A, Biondi ML, et al. Serum fetuin-A levels link inflammation and cardiovascular calcification in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2006;26:423-429.

- Luo G, Ducy P, McKee MD, et al. Spontaneous calcification of arteries and cartilage in mice lacking matrix GLA protein. Nature. 1997;386:78-81.

- Weenig RH. Pathogenesis of calciphylaxis: Hans Selye to nuclear factor kappa-B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:458-471.

- Ketteler M, Bongartz P, Westenfeld R, et al. Association of low fetuin-A (AHSG) concentrations in serum with cardiovascular mortality in patients on dialysis: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2003;361:827-833.

- Wallin R, Cain D, Sane DC. Matrix Gla protein synthesis and gamma-carboxylation in the aortic vessel wall and proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells a cell system which resembles the system in bone cells. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:1764-1767.

- Sowers KM, Hayden MR. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy: pathophysiology, reactive oxygen species and therapeutic approaches. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2010;3:109-121.

- Allegretti AS, Nazarian RM, Goverman J, et al. Calciphylaxis: a rare but fatal delayed complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:274-277.

- Wilmer WA, Magro CM. Calciphylaxis: emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Dial. 2002;15:172-186.

- Gupta D, Tadros R, Mazumdar A, et al. Breast lesions with intractable pain in end-stage renal disease: calciphylaxis with chronic hypotensive dermatopathy related watershed breast lesions. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:551-554.

- Janigan DT, Hirsch DJ, Klassen GA, et al. Calcified subcutaneous arterioles with infarcts of the subcutis and skin (“calciphylaxis”) in chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:588-597.

- Jeong HS, Dominguez AR. Calciphylaxis: controversies in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Med Sci. 2016;351:217-227.

- Bourgeois P, De Haes P. Sodium thiosulfate as a treatment for calciphylaxis: a case series. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:520-524.

- Biswas A, Walsh NM, Tremaine R. A case of nonuremic calciphylaxis treated effectively with systemic corticosteroids. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:275-278.

- Selk N, Rodby, RA. Unexpectedly severe metabolic acidosis associated with sodium thiosulfate therapy in a patient with calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Semin Dial. 2011;24:85-88.

- Martin R. Mysterious calciphylaxis: wounds with eschar—to debride or not to debride? Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004:50:64-66, 68-70.

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146.

Calciphylaxis, otherwise known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is characterized by calcification of the tunica media of the small- to medium-sized blood vessels of the dermis and subcutis, leading to ischemia and necrosis.1 It is a deadly disease with a 1-year mortality rate of more than 50%.2 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is the most common risk factor for calciphylaxis, with a prevalence of 1% to 4% of hemodialysis patients with calciphylaxis in the United States.2-5 However, nonuremic calciphylaxis (NUC) has been increasingly reported in the literature and has risk factors other than ESRD, including but not limited to obesity, alcoholic liver disease, primary hyperparathyroidism, connective tissue disease, and underlying malignancy.3,6-9 Triggers for calciphylaxis in at-risk patients include use of corticosteroids or warfarin, iron or albumin infusions, and rapid weight loss.3,6,9-11 We report an unusual case of NUC that most likely was triggered by rapid weight loss and hypotension in a patient with multiple risk factors for calciphylaxis.

Case Report

A 75-year-old white woman with history of morbid obesity (body mass index, 40 kg/m2), unexplained weight loss of 70 lb over the last year, and polymyalgia rheumatica requiring chronic prednisone therapy presented with painful lesions on the thighs, buttocks, and right shoulder of 4 months’ duration. She had multiple hospital admissions preceding the onset of lesions for severe infections resulting in sepsis with hypotension, including Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase bacteremia, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Physical examination revealed large well-demarcated ulcers and necrotic eschars with surrounding violaceous induration and stellate erythema on the anterior, medial, and posterior thighs and buttocks that were exquisitely tender (Figures 1 and 2).

Notable laboratory results included hypoalbuminemia (1.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.5–5.0 g/dL]) with normal renal function, a corrected calcium level of 9.7 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL), a serum phosphorus level of 3.5 mg/dL (reference range, 2.3–4.7 mg/dL), a calcium-phosphate product of 27.3 mg2/dL2 (reference range, <55 mg2/dL2), and a parathyroid hormone level of 49.3 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL). Antinuclear antibodies were negative. A hypercoagulability evaluation showed normal protein C and S levels, negative lupus anticoagulant, and negative anticardiolipin antibodies.

Telescoping punch biopsies of the indurated borders of the eschars showed prominent calcification of the small- and medium-sized vessels in the mid and deep dermis, intravascular thrombi, and necrosis of the epidermis and subcutaneous fat consistent with calciphylaxis (Figure 3).

After the diagnosis of calciphylaxis was made, the patient was treated with intravenous sodium thiosulfate 25 mg 3 times weekly and alendronate 70 mg weekly. Daily arterial blood gas studies did not detect metabolic acidosis during the patient’s sodium thiosulfate therapy. The wounds were debrided, and we attempted to slowly taper the patient off the oral prednisone. Unfortunately, her condition slowly deteriorated secondary to sepsis, resulting in septic shock. The patient died 3 weeks after the diagnosis of calciphylaxis was made. At the time of diagnosis, the patient had a poor prognosis and notable risk for sepsis due to the large eschars on the thighs and abdomen as well as her relative immunosuppression due to chronic prednisone use.

Comment

Background on Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis is a rare but deadly disease that affects both ESRD patients receiving dialysis and patients without ESRD who have known risk factors for calciphylaxis, including female gender, white race, obesity, alcoholic liver disease, primary hyperparathyroidism, connective tissue disease, underlying malignancy, protein C or S deficiency, corticosteroid use, warfarin use, diabetes, iron or albumin infusions, and rapid weight loss.3,6-9,11 Although the molecular pathogenesis of calciphylaxis is not completely understood, it is believed to be caused by local deposition of calcium in the tunica media of small- to medium-sized arterioles and venules in the skin.12 This deposition leads to intimal proliferation and progressive narrowing of the vessels with resultant thrombosis, ischemia, and necrosis. The cutaneous manifestations and histopathology of calciphylaxis classically follow its pathogenesis. Calciphylaxis typically presents with livedo reticularis as vessels narrow and then progresses to purpura, bullae, necrosis, and eschar formation with the onset of acute thrombosis and ischemia. Histopathology is characterized by small- and medium-sized vessel calcification and thrombus, dermal necrosis, and septal panniculitis, though the histology can be highly variable.12 Unfortunately, the already poor prognosis for calciphylaxis worsens when lesions become either ulcerative or present on the proximal extremities and trunk.4,13 Sepsis is the leading cause of death in calciphylaxis patients, affecting more than 50% of patients.2,3,14 The differential diagnoses for calciphylactic-appearing lesions include warfarin-induced skin necrosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, pyoderma gangrenosum, cholesterol emboli, and various vasculitides and coagulopathies.

Risk Factors

Our case demonstrates the importance of risk factor minimization, trigger avoidance, and early intervention due to the high mortality rate of calciphylaxis. Selye et al15 coined the term calciphylaxis in 1961 based on experiments that induced calciphylaxis in rat models. Their research concluded that there were certain sensitizers (ie, risk factors) that predisposed patients to medial calcium deposition in blood vessels and other challengers (ie, triggers) that acted as inciting events to calcium deposition. Our patient presented with multiple known risk factors for calciphylaxis, including obesity (body mass index, 40 kg/m2), female gender, white race, hypoalbuminemia, and chronic corticosteroid use.16 In the presence of a milieu of risk factors, the patient’s rapid weight loss and episodes of hypotension likely were triggers for calciphylaxis.

Other case reports in the literature have suggested weight loss as a trigger for NUC. One morbidly obese patient with inactive rheumatoid arthritis had onset of calciphylaxis lesions after unintentional weight loss of approximately 50% body weight in 1 year17; however, the weight loss does not have to be drastic to trigger calciphylaxis. Another study of 16 patients with uremic calciphylaxis found that 7 of 16 (44%) patients lost 10 to 50 kg in the 6 months prior to calciphylaxis onset.14 One proposed mechanism by Munavalli et al10 is that elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinases during catabolic weight loss states enhance the deposition of calcium into elastic fibers of small vessels. The authors found elevated serum levels of matrix metalloproteinases in their patients with NUC induced by rapid weight loss.10

A meta-analysis by Nigwekar et al3 found a history of prior corticosteroid use in 61% (22/36) of NUC cases reviewed. However, it is unclear whether it is the use of corticosteroids or chronic inflammation that is implicated in NUC pathogenesis. Chronic inflammation causes downregulation of anticalcification signaling pathways.18-20 The role of 2 vascular calcification inhibitors has been evaluated in the pathogenesis of calciphylaxis: fetuin-A and matrix gla protein (MGP).21 The activity of these proteins is decreased not only in calciphylaxis but also in other inflammatory states and chronic renal failure.18-20 One study found lower fetuin-A levels in 312 hemodialysis patients compared to healthy controls and an association between low fetuin-A levels and increased C-reactive protein levels.22 Reduced fetuin-A and MGP levels may be the result of several calciphylaxis risk factors. Warfarin is believed to trigger calciphylaxis via inhibition of gamma-carboxylation of MGP, which is necessary for its anticalcification activity.23 Hypoalbuminemia and alcoholic liver disease also are risk factors that may be explained by the fact that fetuin-A is synthesized in the liver.24 Therefore, liver disease results in decreased production of fetuin-A that is permissive to vascular calcification in calciphylaxis patients.

There have been other reports of calciphylaxis patients who were originally hospitalized due to hypotension, which may serve as a trigger for calciphylaxis onset.25 Because calciphylaxis lesions are more likely to occur in the fatty areas of the abdomen and proximal thighs where blood flow is slower, hypotension likely accentuates the slowing of blood flow and subsequent blood vessel calcification. This theory is supported by studies showing that established calciphylactic lesions worsen more quickly in the presence of systemic hypotension.26 One patient with ESRD and calciphylaxis of the breasts had consistent systolic blood pressure readings in the high 60s to low 70s between dialysis sessions.27 Due to this association, we recommend that patients with calciphylaxis have close blood pressure monitoring to aid in preventing disease progression.28

Management

Calciphylaxis treatment has not yet been standardized, as it is an uncommon disease whose pathogenesis is not fully understood. Current management strategies aim to normalize metabolic abnormalities such as hypercalcemia if they are present and remove inciting agents such as warfarin and corticosteroids.29 Other medical treatments that have been successfully used include sodium thiosulfate, oral steroids, and adjunctive bisphosphonates.29-31 Sodium thiosulfate is known to cause metabolic acidosis by generating thiosulfuric acid in vivo in patients with or without renal disease; therefore, patients on sodium thiosulfate therapy should be monitored for development of metabolic acidosis and treated with oral sodium bicarbonate or dialysis as needed.30,32 Wound care also is an important element of calciphylaxis treatment; however, the debridement of wounds is controversial. Some argue that dry intact eschars serve to protect against sepsis, which is the leading cause of death in calciphylaxis.2,14,33 In contrast, a retrospective study of 63 calciphylaxis patients found a 1-year survival rate of 61.6% in 17 patients receiving wound debridement vs 27.4% in 46 patients who did not.2 The current consensus is that debridement should be considered on a case-by-case basis, factoring in the presence of wound infection, size of wounds, stability of eschars, and treatment goals of the patient.34 Future studies should be aimed at this issue, with special focus on how these factors and the decision to debride or not impact patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Calciphylaxis is a potentially fatal disease that impacts both patients with ESRD and those with nonuremic risk factors. The term calcific uremic arteriolopathy should be disregarded, as nonuremic causes are being reported with increased frequency in the literature. In such cases, patients often have multiple risk factors, including obesity, primary hyperparathyroidism, alcoholic liver disease, and underlying malignancy, among others. Certain triggers for onset of calciphylaxis should be avoided in at-risk patients, including the use of corticosteroids or warfarin; iron and albumin infusions; hypotension; and rapid weight loss. Our fatal case of NUC is a reminder to dermatologists treating at-risk patients to avoid these triggers and to keep calciphylaxis in the differential diagnosis when encountering early lesions such as livedo reticularis, as progression of these lesions has a 1-year mortality rate of more than 50% with the therapies being utilized at this time.

Calciphylaxis, otherwise known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is characterized by calcification of the tunica media of the small- to medium-sized blood vessels of the dermis and subcutis, leading to ischemia and necrosis.1 It is a deadly disease with a 1-year mortality rate of more than 50%.2 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is the most common risk factor for calciphylaxis, with a prevalence of 1% to 4% of hemodialysis patients with calciphylaxis in the United States.2-5 However, nonuremic calciphylaxis (NUC) has been increasingly reported in the literature and has risk factors other than ESRD, including but not limited to obesity, alcoholic liver disease, primary hyperparathyroidism, connective tissue disease, and underlying malignancy.3,6-9 Triggers for calciphylaxis in at-risk patients include use of corticosteroids or warfarin, iron or albumin infusions, and rapid weight loss.3,6,9-11 We report an unusual case of NUC that most likely was triggered by rapid weight loss and hypotension in a patient with multiple risk factors for calciphylaxis.

Case Report

A 75-year-old white woman with history of morbid obesity (body mass index, 40 kg/m2), unexplained weight loss of 70 lb over the last year, and polymyalgia rheumatica requiring chronic prednisone therapy presented with painful lesions on the thighs, buttocks, and right shoulder of 4 months’ duration. She had multiple hospital admissions preceding the onset of lesions for severe infections resulting in sepsis with hypotension, including Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase bacteremia, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Physical examination revealed large well-demarcated ulcers and necrotic eschars with surrounding violaceous induration and stellate erythema on the anterior, medial, and posterior thighs and buttocks that were exquisitely tender (Figures 1 and 2).

Notable laboratory results included hypoalbuminemia (1.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.5–5.0 g/dL]) with normal renal function, a corrected calcium level of 9.7 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL), a serum phosphorus level of 3.5 mg/dL (reference range, 2.3–4.7 mg/dL), a calcium-phosphate product of 27.3 mg2/dL2 (reference range, <55 mg2/dL2), and a parathyroid hormone level of 49.3 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL). Antinuclear antibodies were negative. A hypercoagulability evaluation showed normal protein C and S levels, negative lupus anticoagulant, and negative anticardiolipin antibodies.

Telescoping punch biopsies of the indurated borders of the eschars showed prominent calcification of the small- and medium-sized vessels in the mid and deep dermis, intravascular thrombi, and necrosis of the epidermis and subcutaneous fat consistent with calciphylaxis (Figure 3).

After the diagnosis of calciphylaxis was made, the patient was treated with intravenous sodium thiosulfate 25 mg 3 times weekly and alendronate 70 mg weekly. Daily arterial blood gas studies did not detect metabolic acidosis during the patient’s sodium thiosulfate therapy. The wounds were debrided, and we attempted to slowly taper the patient off the oral prednisone. Unfortunately, her condition slowly deteriorated secondary to sepsis, resulting in septic shock. The patient died 3 weeks after the diagnosis of calciphylaxis was made. At the time of diagnosis, the patient had a poor prognosis and notable risk for sepsis due to the large eschars on the thighs and abdomen as well as her relative immunosuppression due to chronic prednisone use.

Comment

Background on Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis is a rare but deadly disease that affects both ESRD patients receiving dialysis and patients without ESRD who have known risk factors for calciphylaxis, including female gender, white race, obesity, alcoholic liver disease, primary hyperparathyroidism, connective tissue disease, underlying malignancy, protein C or S deficiency, corticosteroid use, warfarin use, diabetes, iron or albumin infusions, and rapid weight loss.3,6-9,11 Although the molecular pathogenesis of calciphylaxis is not completely understood, it is believed to be caused by local deposition of calcium in the tunica media of small- to medium-sized arterioles and venules in the skin.12 This deposition leads to intimal proliferation and progressive narrowing of the vessels with resultant thrombosis, ischemia, and necrosis. The cutaneous manifestations and histopathology of calciphylaxis classically follow its pathogenesis. Calciphylaxis typically presents with livedo reticularis as vessels narrow and then progresses to purpura, bullae, necrosis, and eschar formation with the onset of acute thrombosis and ischemia. Histopathology is characterized by small- and medium-sized vessel calcification and thrombus, dermal necrosis, and septal panniculitis, though the histology can be highly variable.12 Unfortunately, the already poor prognosis for calciphylaxis worsens when lesions become either ulcerative or present on the proximal extremities and trunk.4,13 Sepsis is the leading cause of death in calciphylaxis patients, affecting more than 50% of patients.2,3,14 The differential diagnoses for calciphylactic-appearing lesions include warfarin-induced skin necrosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, pyoderma gangrenosum, cholesterol emboli, and various vasculitides and coagulopathies.

Risk Factors

Our case demonstrates the importance of risk factor minimization, trigger avoidance, and early intervention due to the high mortality rate of calciphylaxis. Selye et al15 coined the term calciphylaxis in 1961 based on experiments that induced calciphylaxis in rat models. Their research concluded that there were certain sensitizers (ie, risk factors) that predisposed patients to medial calcium deposition in blood vessels and other challengers (ie, triggers) that acted as inciting events to calcium deposition. Our patient presented with multiple known risk factors for calciphylaxis, including obesity (body mass index, 40 kg/m2), female gender, white race, hypoalbuminemia, and chronic corticosteroid use.16 In the presence of a milieu of risk factors, the patient’s rapid weight loss and episodes of hypotension likely were triggers for calciphylaxis.

Other case reports in the literature have suggested weight loss as a trigger for NUC. One morbidly obese patient with inactive rheumatoid arthritis had onset of calciphylaxis lesions after unintentional weight loss of approximately 50% body weight in 1 year17; however, the weight loss does not have to be drastic to trigger calciphylaxis. Another study of 16 patients with uremic calciphylaxis found that 7 of 16 (44%) patients lost 10 to 50 kg in the 6 months prior to calciphylaxis onset.14 One proposed mechanism by Munavalli et al10 is that elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinases during catabolic weight loss states enhance the deposition of calcium into elastic fibers of small vessels. The authors found elevated serum levels of matrix metalloproteinases in their patients with NUC induced by rapid weight loss.10

A meta-analysis by Nigwekar et al3 found a history of prior corticosteroid use in 61% (22/36) of NUC cases reviewed. However, it is unclear whether it is the use of corticosteroids or chronic inflammation that is implicated in NUC pathogenesis. Chronic inflammation causes downregulation of anticalcification signaling pathways.18-20 The role of 2 vascular calcification inhibitors has been evaluated in the pathogenesis of calciphylaxis: fetuin-A and matrix gla protein (MGP).21 The activity of these proteins is decreased not only in calciphylaxis but also in other inflammatory states and chronic renal failure.18-20 One study found lower fetuin-A levels in 312 hemodialysis patients compared to healthy controls and an association between low fetuin-A levels and increased C-reactive protein levels.22 Reduced fetuin-A and MGP levels may be the result of several calciphylaxis risk factors. Warfarin is believed to trigger calciphylaxis via inhibition of gamma-carboxylation of MGP, which is necessary for its anticalcification activity.23 Hypoalbuminemia and alcoholic liver disease also are risk factors that may be explained by the fact that fetuin-A is synthesized in the liver.24 Therefore, liver disease results in decreased production of fetuin-A that is permissive to vascular calcification in calciphylaxis patients.

There have been other reports of calciphylaxis patients who were originally hospitalized due to hypotension, which may serve as a trigger for calciphylaxis onset.25 Because calciphylaxis lesions are more likely to occur in the fatty areas of the abdomen and proximal thighs where blood flow is slower, hypotension likely accentuates the slowing of blood flow and subsequent blood vessel calcification. This theory is supported by studies showing that established calciphylactic lesions worsen more quickly in the presence of systemic hypotension.26 One patient with ESRD and calciphylaxis of the breasts had consistent systolic blood pressure readings in the high 60s to low 70s between dialysis sessions.27 Due to this association, we recommend that patients with calciphylaxis have close blood pressure monitoring to aid in preventing disease progression.28

Management

Calciphylaxis treatment has not yet been standardized, as it is an uncommon disease whose pathogenesis is not fully understood. Current management strategies aim to normalize metabolic abnormalities such as hypercalcemia if they are present and remove inciting agents such as warfarin and corticosteroids.29 Other medical treatments that have been successfully used include sodium thiosulfate, oral steroids, and adjunctive bisphosphonates.29-31 Sodium thiosulfate is known to cause metabolic acidosis by generating thiosulfuric acid in vivo in patients with or without renal disease; therefore, patients on sodium thiosulfate therapy should be monitored for development of metabolic acidosis and treated with oral sodium bicarbonate or dialysis as needed.30,32 Wound care also is an important element of calciphylaxis treatment; however, the debridement of wounds is controversial. Some argue that dry intact eschars serve to protect against sepsis, which is the leading cause of death in calciphylaxis.2,14,33 In contrast, a retrospective study of 63 calciphylaxis patients found a 1-year survival rate of 61.6% in 17 patients receiving wound debridement vs 27.4% in 46 patients who did not.2 The current consensus is that debridement should be considered on a case-by-case basis, factoring in the presence of wound infection, size of wounds, stability of eschars, and treatment goals of the patient.34 Future studies should be aimed at this issue, with special focus on how these factors and the decision to debride or not impact patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Calciphylaxis is a potentially fatal disease that impacts both patients with ESRD and those with nonuremic risk factors. The term calcific uremic arteriolopathy should be disregarded, as nonuremic causes are being reported with increased frequency in the literature. In such cases, patients often have multiple risk factors, including obesity, primary hyperparathyroidism, alcoholic liver disease, and underlying malignancy, among others. Certain triggers for onset of calciphylaxis should be avoided in at-risk patients, including the use of corticosteroids or warfarin; iron and albumin infusions; hypotension; and rapid weight loss. Our fatal case of NUC is a reminder to dermatologists treating at-risk patients to avoid these triggers and to keep calciphylaxis in the differential diagnosis when encountering early lesions such as livedo reticularis, as progression of these lesions has a 1-year mortality rate of more than 50% with the therapies being utilized at this time.

- Au S, Crawford RI. Three-dimensional analysis of a calciphylaxis plaque: clues to pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;47:53-57.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, et al. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:569-579.

- Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, et al. Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1139-1143.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2210-2217.

- Angelis M, Wong LL, Myers SA, et al. Calciphylaxis in patients on hemodialysis: a prevalence study. Surgery. 1997;122:1083-1090.

- Chavel SM, Taraszka KS, Schaffer JV, et al. Calciphylaxis associated with acute, reversible renal failure in the setting of alcoholic cirrhosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:125-128.

- Bosler DS, Amin MB, Gulli F, et al. Unusual case of calciphylaxis associated with metastatic breast carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:400-403.

- Buxtorf K, Cerottini JP, Panizzon RG. Lower limb skin ulcerations, intravascular calcifications and sensorimotor polyneuropathy: calciphylaxis as part of a hyperparathyroidism? Dermatology. 1999;198:423-425.

- Brouns K, Verbeken E, Degreef H, et al. Fatal calciphylaxis in two patients with giant cell arteritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:836-840.

- Munavalli G, Reisenauer A, Moses M, et al. Weight loss-induced calciphylaxis: potential role of matrix metalloproteinases. J Dermatol. 2003;30:915-919.

- Bae GH, Nambudiri VE, Bach DQ, et al. Rapidly progressive nonuremic calciphylaxis in setting of warfarin. Am J Med. 2015;128:E19-E21.

- Essary LR, Wick MR. Cutaneous calciphylaxis. an underrecognized clinicopathologic entity. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:280-287.

- Hafner J, Keusch G, Wahl C, et al. Uremic small-artery disease with medial calcification and intimal hyperplasia (so-called calciphylaxis): a complication of chronic renal failure and benefit from parathyroidectomy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:954-962.

- Coates T, Kirkland GS, Dymock RB, et al. Cutaneous necrosis from calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:384-391.

- Selye H, Gentile G, Prioreschi P. Cutaneous molt induced by calciphylaxis in the rat. Science. 1961;134:1876-1877.

- Kalajian AH, Malhotra PS, Callen JP, et al. Calciphylaxis with normal renal and parathyroid function: not as rare as previously believed. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:451-458.

- Malabu U, Roberts L, Sangla K. Calciphylaxis in a morbidly obese woman with rheumatoid arthritis presenting with severe weight loss and vitamin D deficiency. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:104-108.

- Schäfer C, Heiss A, Schwarz A, et al. The serum protein alpha 2–Heremans-Schmid glycoprotein/fetuin-A is a systemically acting inhibitor of ectopic calcification. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:357-366.

- Cozzolino M, Galassi A, Biondi ML, et al. Serum fetuin-A levels link inflammation and cardiovascular calcification in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2006;26:423-429.

- Luo G, Ducy P, McKee MD, et al. Spontaneous calcification of arteries and cartilage in mice lacking matrix GLA protein. Nature. 1997;386:78-81.

- Weenig RH. Pathogenesis of calciphylaxis: Hans Selye to nuclear factor kappa-B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:458-471.

- Ketteler M, Bongartz P, Westenfeld R, et al. Association of low fetuin-A (AHSG) concentrations in serum with cardiovascular mortality in patients on dialysis: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2003;361:827-833.

- Wallin R, Cain D, Sane DC. Matrix Gla protein synthesis and gamma-carboxylation in the aortic vessel wall and proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells a cell system which resembles the system in bone cells. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:1764-1767.

- Sowers KM, Hayden MR. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy: pathophysiology, reactive oxygen species and therapeutic approaches. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2010;3:109-121.

- Allegretti AS, Nazarian RM, Goverman J, et al. Calciphylaxis: a rare but fatal delayed complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:274-277.

- Wilmer WA, Magro CM. Calciphylaxis: emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Dial. 2002;15:172-186.

- Gupta D, Tadros R, Mazumdar A, et al. Breast lesions with intractable pain in end-stage renal disease: calciphylaxis with chronic hypotensive dermatopathy related watershed breast lesions. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:551-554.

- Janigan DT, Hirsch DJ, Klassen GA, et al. Calcified subcutaneous arterioles with infarcts of the subcutis and skin (“calciphylaxis”) in chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:588-597.

- Jeong HS, Dominguez AR. Calciphylaxis: controversies in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Med Sci. 2016;351:217-227.

- Bourgeois P, De Haes P. Sodium thiosulfate as a treatment for calciphylaxis: a case series. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:520-524.

- Biswas A, Walsh NM, Tremaine R. A case of nonuremic calciphylaxis treated effectively with systemic corticosteroids. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:275-278.

- Selk N, Rodby, RA. Unexpectedly severe metabolic acidosis associated with sodium thiosulfate therapy in a patient with calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Semin Dial. 2011;24:85-88.

- Martin R. Mysterious calciphylaxis: wounds with eschar—to debride or not to debride? Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004:50:64-66, 68-70.

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146.

- Au S, Crawford RI. Three-dimensional analysis of a calciphylaxis plaque: clues to pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;47:53-57.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, et al. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:569-579.

- Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, et al. Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1139-1143.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2210-2217.

- Angelis M, Wong LL, Myers SA, et al. Calciphylaxis in patients on hemodialysis: a prevalence study. Surgery. 1997;122:1083-1090.

- Chavel SM, Taraszka KS, Schaffer JV, et al. Calciphylaxis associated with acute, reversible renal failure in the setting of alcoholic cirrhosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:125-128.

- Bosler DS, Amin MB, Gulli F, et al. Unusual case of calciphylaxis associated with metastatic breast carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:400-403.

- Buxtorf K, Cerottini JP, Panizzon RG. Lower limb skin ulcerations, intravascular calcifications and sensorimotor polyneuropathy: calciphylaxis as part of a hyperparathyroidism? Dermatology. 1999;198:423-425.

- Brouns K, Verbeken E, Degreef H, et al. Fatal calciphylaxis in two patients with giant cell arteritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:836-840.

- Munavalli G, Reisenauer A, Moses M, et al. Weight loss-induced calciphylaxis: potential role of matrix metalloproteinases. J Dermatol. 2003;30:915-919.

- Bae GH, Nambudiri VE, Bach DQ, et al. Rapidly progressive nonuremic calciphylaxis in setting of warfarin. Am J Med. 2015;128:E19-E21.

- Essary LR, Wick MR. Cutaneous calciphylaxis. an underrecognized clinicopathologic entity. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:280-287.

- Hafner J, Keusch G, Wahl C, et al. Uremic small-artery disease with medial calcification and intimal hyperplasia (so-called calciphylaxis): a complication of chronic renal failure and benefit from parathyroidectomy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:954-962.

- Coates T, Kirkland GS, Dymock RB, et al. Cutaneous necrosis from calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:384-391.

- Selye H, Gentile G, Prioreschi P. Cutaneous molt induced by calciphylaxis in the rat. Science. 1961;134:1876-1877.

- Kalajian AH, Malhotra PS, Callen JP, et al. Calciphylaxis with normal renal and parathyroid function: not as rare as previously believed. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:451-458.

- Malabu U, Roberts L, Sangla K. Calciphylaxis in a morbidly obese woman with rheumatoid arthritis presenting with severe weight loss and vitamin D deficiency. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:104-108.

- Schäfer C, Heiss A, Schwarz A, et al. The serum protein alpha 2–Heremans-Schmid glycoprotein/fetuin-A is a systemically acting inhibitor of ectopic calcification. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:357-366.

- Cozzolino M, Galassi A, Biondi ML, et al. Serum fetuin-A levels link inflammation and cardiovascular calcification in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2006;26:423-429.

- Luo G, Ducy P, McKee MD, et al. Spontaneous calcification of arteries and cartilage in mice lacking matrix GLA protein. Nature. 1997;386:78-81.

- Weenig RH. Pathogenesis of calciphylaxis: Hans Selye to nuclear factor kappa-B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:458-471.

- Ketteler M, Bongartz P, Westenfeld R, et al. Association of low fetuin-A (AHSG) concentrations in serum with cardiovascular mortality in patients on dialysis: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2003;361:827-833.

- Wallin R, Cain D, Sane DC. Matrix Gla protein synthesis and gamma-carboxylation in the aortic vessel wall and proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells a cell system which resembles the system in bone cells. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:1764-1767.

- Sowers KM, Hayden MR. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy: pathophysiology, reactive oxygen species and therapeutic approaches. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2010;3:109-121.

- Allegretti AS, Nazarian RM, Goverman J, et al. Calciphylaxis: a rare but fatal delayed complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:274-277.

- Wilmer WA, Magro CM. Calciphylaxis: emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Dial. 2002;15:172-186.

- Gupta D, Tadros R, Mazumdar A, et al. Breast lesions with intractable pain in end-stage renal disease: calciphylaxis with chronic hypotensive dermatopathy related watershed breast lesions. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:551-554.

- Janigan DT, Hirsch DJ, Klassen GA, et al. Calcified subcutaneous arterioles with infarcts of the subcutis and skin (“calciphylaxis”) in chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:588-597.

- Jeong HS, Dominguez AR. Calciphylaxis: controversies in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Med Sci. 2016;351:217-227.

- Bourgeois P, De Haes P. Sodium thiosulfate as a treatment for calciphylaxis: a case series. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:520-524.

- Biswas A, Walsh NM, Tremaine R. A case of nonuremic calciphylaxis treated effectively with systemic corticosteroids. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:275-278.

- Selk N, Rodby, RA. Unexpectedly severe metabolic acidosis associated with sodium thiosulfate therapy in a patient with calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Semin Dial. 2011;24:85-88.

- Martin R. Mysterious calciphylaxis: wounds with eschar—to debride or not to debride? Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004:50:64-66, 68-70.

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146.

Practice Points

- Calciphylaxis is a potentially fatal disease caused by metastatic calcification of cutaneous small- and medium-sized blood vessels leading to ischemia and necrosis.

- Calciphylaxis most commonly is seen in patients with renal disease requiring dialysis, but it also may be triggered by nonuremic causes in patients with known risk factors for calciphylaxis.

- Risk factors for calciphylaxis include female gender, white race, obesity, alcoholic liver disease, primary hyperparathyroidism, connective tissue disease, underlying malignancy, protein C or S deficiency, corticosteroid use, warfarin use, diabetes, iron or albumin infusions, and rapid weight loss.

- The term calcific uremic arteriolopathy should be disregarded, as nonuremic causes are being reported with increased frequency in the literature.

Antimalarial adherence is important for diabetes prevention in lupus

Adhering to antimalarial treatment offers some protection to patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) from developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), according to new research.

Patients who took at least 90% of their prescribed antimalarial doses were 39% less likely to develop T2DM than patients who discontinued antimalarial therapy. Patients who took less than 90% of their prescribed doses but didn’t discontinue treatment were 22% less likely to develop T2DM.

“[O]ur study provides further support for the importance of adherence to antimalarials in SLE by demonstrating protective impacts on T2DM,” Shahrzad Salmasi, PhD, of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and colleagues wrote in Arthritis Care & Research.

Dr. Salmasi and colleagues conducted this retrospective study using administrative health data on patients in British Columbia. The researchers analyzed 1,498 patients with SLE. Their mean age was about 44 years, and 91% were women.

The researchers used data on prescription dates and days’ supply to establish antimalarial drug courses and gaps in treatment. A new treatment course occurred when a 90-day gap was exceeded between refills. The researchers calculated the proportion of days covered (PDC) – the total number of days with antimalarials divided by the length of the course – and separated patients into three categories:

- Adherent to treatment – PDC of 0.90 or greater

- Nonadherent – PDC greater than 0 but less than 0.90

- Discontinuer – PDC of 0

The patients had a mean of about 23 antimalarial prescriptions and a mean of about two courses. The mean course duration was 554 days.

At a median follow-up of 4.6 years, there were 140 incident cases of T2DM. The researchers calculated the risk of T2DM among adherent and nonadherent patients, comparing these groups with the discontinuers and adjusting for age, sex, comorbidities, and concomitant medications.

The adjusted hazard ratio for developing T2DM was 0.61 among adherent patients and 0.78 among nonadherent patients.

“This population-based study highlighted that taking less than 90% of the prescribed antimalarials compromises their effect in preventing T2DM in SLE patients,” Dr. Salmasi and colleagues wrote. “Our findings should be used to emphasize the importance of medication adherence in not only treating SLE but also preventing its complications.”

The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Salmasi S et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2020 Jan 21. doi: 10.1002/acr.24147.

Adhering to antimalarial treatment offers some protection to patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) from developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), according to new research.

Patients who took at least 90% of their prescribed antimalarial doses were 39% less likely to develop T2DM than patients who discontinued antimalarial therapy. Patients who took less than 90% of their prescribed doses but didn’t discontinue treatment were 22% less likely to develop T2DM.

“[O]ur study provides further support for the importance of adherence to antimalarials in SLE by demonstrating protective impacts on T2DM,” Shahrzad Salmasi, PhD, of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and colleagues wrote in Arthritis Care & Research.

Dr. Salmasi and colleagues conducted this retrospective study using administrative health data on patients in British Columbia. The researchers analyzed 1,498 patients with SLE. Their mean age was about 44 years, and 91% were women.

The researchers used data on prescription dates and days’ supply to establish antimalarial drug courses and gaps in treatment. A new treatment course occurred when a 90-day gap was exceeded between refills. The researchers calculated the proportion of days covered (PDC) – the total number of days with antimalarials divided by the length of the course – and separated patients into three categories:

- Adherent to treatment – PDC of 0.90 or greater

- Nonadherent – PDC greater than 0 but less than 0.90

- Discontinuer – PDC of 0

The patients had a mean of about 23 antimalarial prescriptions and a mean of about two courses. The mean course duration was 554 days.

At a median follow-up of 4.6 years, there were 140 incident cases of T2DM. The researchers calculated the risk of T2DM among adherent and nonadherent patients, comparing these groups with the discontinuers and adjusting for age, sex, comorbidities, and concomitant medications.

The adjusted hazard ratio for developing T2DM was 0.61 among adherent patients and 0.78 among nonadherent patients.

“This population-based study highlighted that taking less than 90% of the prescribed antimalarials compromises their effect in preventing T2DM in SLE patients,” Dr. Salmasi and colleagues wrote. “Our findings should be used to emphasize the importance of medication adherence in not only treating SLE but also preventing its complications.”

The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Salmasi S et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2020 Jan 21. doi: 10.1002/acr.24147.

Adhering to antimalarial treatment offers some protection to patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) from developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), according to new research.

Patients who took at least 90% of their prescribed antimalarial doses were 39% less likely to develop T2DM than patients who discontinued antimalarial therapy. Patients who took less than 90% of their prescribed doses but didn’t discontinue treatment were 22% less likely to develop T2DM.

“[O]ur study provides further support for the importance of adherence to antimalarials in SLE by demonstrating protective impacts on T2DM,” Shahrzad Salmasi, PhD, of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and colleagues wrote in Arthritis Care & Research.

Dr. Salmasi and colleagues conducted this retrospective study using administrative health data on patients in British Columbia. The researchers analyzed 1,498 patients with SLE. Their mean age was about 44 years, and 91% were women.

The researchers used data on prescription dates and days’ supply to establish antimalarial drug courses and gaps in treatment. A new treatment course occurred when a 90-day gap was exceeded between refills. The researchers calculated the proportion of days covered (PDC) – the total number of days with antimalarials divided by the length of the course – and separated patients into three categories:

- Adherent to treatment – PDC of 0.90 or greater

- Nonadherent – PDC greater than 0 but less than 0.90

- Discontinuer – PDC of 0

The patients had a mean of about 23 antimalarial prescriptions and a mean of about two courses. The mean course duration was 554 days.

At a median follow-up of 4.6 years, there were 140 incident cases of T2DM. The researchers calculated the risk of T2DM among adherent and nonadherent patients, comparing these groups with the discontinuers and adjusting for age, sex, comorbidities, and concomitant medications.

The adjusted hazard ratio for developing T2DM was 0.61 among adherent patients and 0.78 among nonadherent patients.

“This population-based study highlighted that taking less than 90% of the prescribed antimalarials compromises their effect in preventing T2DM in SLE patients,” Dr. Salmasi and colleagues wrote. “Our findings should be used to emphasize the importance of medication adherence in not only treating SLE but also preventing its complications.”

The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Salmasi S et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2020 Jan 21. doi: 10.1002/acr.24147.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Core behaviors enhance communication about neonatal death

Clinicians can improve communications with parents during neonatal end-of-life situations by adopting key behaviors such as sitting down to talk to parents and using the infant’s name, according to data from a simulation study.