User login

Echoes of SARS mark 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak

The current outbreak of severe respiratory infections caused by the 2019 novel coronarvirus (2019-nCoV) has a clinical presentation resembling the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) outbreak that began in 2002, Chinese investigators caution.

By Jan. 2, 2020, 41 patients with confirmed 2019-nCoV had been admitted to a designated hospital in the city of Wuhan, Hubei Province, in central China. Thirteen required ICU admission and six died, reported Chaolin Huang, MD, from Jin Yin-tan Hospital in Wuhan, and colleagues.

“2019-nCoV still needs to be studied deeply in case it becomes a global health threat. Reliable quick pathogen tests and feasible differential diagnosis based on clinical description are crucial for clinicians in their first contact with suspected patients. Because of the pandemic potential of 2019-nCoV, careful surveillance is essential to monitor its future host adaption, viral evolution, infectivity, transmissibility, and pathogenicity,” they wrote in a review published online by The Lancet.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of Jan. 28, 2020, the total number of 2019-nCoV cases reported in the United States stood at five, but further cases of the infection – which Chinese health officials have confirmed can be transmitted person-to-person – are expected.

Dr. Huang and colleagues note that although most human coronavirus infections are mild, SARS-CoV and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) were responsible for more than 10,000 infections, with mortality rates ranging from 10% with SARS to 37% with MERS. To date, 2019-nCoV has “caused clusters of fatal pneumonia greatly resembling SARS-CoV,” they write.

The authors studied the epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, and radiological characteristics as well as treatments and clinical outcomes of 41 patients admitted or transferred to the Jin Yin-tan Hospital with laboratory-confirmed 2019-nCoV infections.

The median patient age was 49 years. Thirty of the 41 patients (73%) were male. Comorbid conditions included diabetes in 13 of the 41 patients (32%), hypertension in 6 (15%), and cardiovascular disease in 6.

In all 27 of the 41 patients had been exposed to the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, the suspected epicenter of the outbreak that was shut down by health authorities on Jan. 1 of this year.

The most common symptoms at the onset of the illness were fever in all but one of the 41 patients, cough in 31, and myalgia or fatigue in 18. Other, less frequent symptoms included sputum production in 11, headache in three, hemoptysis in two, and diarrhea in one.

“In this cohort, most patients presented with fever, dry cough, dyspnoea, and bilateral ground-glass opacities on chest CT scans. These features of 2019-nCoV infection bear some resemblance to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infections. However, few patients with 2019-nCoV infection had prominent upper respiratory tract signs and symptoms (e.g., rhinorrhoea, sneezing, or sore throat), indicating that the target cells might be located in the lower airway. Furthermore, 2019-nCoV patients rarely developed intestinal signs and symptoms (e.g., diarrhoea), whereas about 20%-25% of patients with MERS-CoV or SARS-CoV infection had diarrhoea.”

In all, 22 patients developed dyspnea, with a median time from illness onset to dyspnea of 8 days. The median time from illness onset to admission was 7 days, median time to shortness of breath was 8 days, median time to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was 9 days, and median time to both mechanical ventilation and ICU admission was 10.5 days.

All of the patients developed pneumonia with abnormal findings on chest CT scan. In addition, 12 patients developed ARDS, six had RNAaemia, five developed acute cardiac injury, and four developed a secondary infection. As noted before, 13 of the 14 patients were admitted to an ICU, and six died. RNAaemia is a positive result for real-time polymerase chain reaction in plasma samples. Patients admitted to the ICU had higher initial concentrations of multiple inflammatory cytokines than patients who did not need ICU care, “suggesting that the cytokine storm was associated with disease severity.”

All of the patients received empirical antibiotics, 38 were treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu), and 9 received systemic corticosteroids.

The investigators have initiated a randomized controlled trial of the antiviral agents lopinavir and ritonavir for patients hospitalized with 2019-nCoV infection.

The study was funded by the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, and Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission. All authors declared having no competing interests.

SOURCE: Huang C et al. Lancet. 2020 Jan 24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5.

The current outbreak of severe respiratory infections caused by the 2019 novel coronarvirus (2019-nCoV) has a clinical presentation resembling the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) outbreak that began in 2002, Chinese investigators caution.

By Jan. 2, 2020, 41 patients with confirmed 2019-nCoV had been admitted to a designated hospital in the city of Wuhan, Hubei Province, in central China. Thirteen required ICU admission and six died, reported Chaolin Huang, MD, from Jin Yin-tan Hospital in Wuhan, and colleagues.

“2019-nCoV still needs to be studied deeply in case it becomes a global health threat. Reliable quick pathogen tests and feasible differential diagnosis based on clinical description are crucial for clinicians in their first contact with suspected patients. Because of the pandemic potential of 2019-nCoV, careful surveillance is essential to monitor its future host adaption, viral evolution, infectivity, transmissibility, and pathogenicity,” they wrote in a review published online by The Lancet.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of Jan. 28, 2020, the total number of 2019-nCoV cases reported in the United States stood at five, but further cases of the infection – which Chinese health officials have confirmed can be transmitted person-to-person – are expected.

Dr. Huang and colleagues note that although most human coronavirus infections are mild, SARS-CoV and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) were responsible for more than 10,000 infections, with mortality rates ranging from 10% with SARS to 37% with MERS. To date, 2019-nCoV has “caused clusters of fatal pneumonia greatly resembling SARS-CoV,” they write.

The authors studied the epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, and radiological characteristics as well as treatments and clinical outcomes of 41 patients admitted or transferred to the Jin Yin-tan Hospital with laboratory-confirmed 2019-nCoV infections.

The median patient age was 49 years. Thirty of the 41 patients (73%) were male. Comorbid conditions included diabetes in 13 of the 41 patients (32%), hypertension in 6 (15%), and cardiovascular disease in 6.

In all 27 of the 41 patients had been exposed to the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, the suspected epicenter of the outbreak that was shut down by health authorities on Jan. 1 of this year.

The most common symptoms at the onset of the illness were fever in all but one of the 41 patients, cough in 31, and myalgia or fatigue in 18. Other, less frequent symptoms included sputum production in 11, headache in three, hemoptysis in two, and diarrhea in one.

“In this cohort, most patients presented with fever, dry cough, dyspnoea, and bilateral ground-glass opacities on chest CT scans. These features of 2019-nCoV infection bear some resemblance to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infections. However, few patients with 2019-nCoV infection had prominent upper respiratory tract signs and symptoms (e.g., rhinorrhoea, sneezing, or sore throat), indicating that the target cells might be located in the lower airway. Furthermore, 2019-nCoV patients rarely developed intestinal signs and symptoms (e.g., diarrhoea), whereas about 20%-25% of patients with MERS-CoV or SARS-CoV infection had diarrhoea.”

In all, 22 patients developed dyspnea, with a median time from illness onset to dyspnea of 8 days. The median time from illness onset to admission was 7 days, median time to shortness of breath was 8 days, median time to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was 9 days, and median time to both mechanical ventilation and ICU admission was 10.5 days.

All of the patients developed pneumonia with abnormal findings on chest CT scan. In addition, 12 patients developed ARDS, six had RNAaemia, five developed acute cardiac injury, and four developed a secondary infection. As noted before, 13 of the 14 patients were admitted to an ICU, and six died. RNAaemia is a positive result for real-time polymerase chain reaction in plasma samples. Patients admitted to the ICU had higher initial concentrations of multiple inflammatory cytokines than patients who did not need ICU care, “suggesting that the cytokine storm was associated with disease severity.”

All of the patients received empirical antibiotics, 38 were treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu), and 9 received systemic corticosteroids.

The investigators have initiated a randomized controlled trial of the antiviral agents lopinavir and ritonavir for patients hospitalized with 2019-nCoV infection.

The study was funded by the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, and Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission. All authors declared having no competing interests.

SOURCE: Huang C et al. Lancet. 2020 Jan 24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5.

The current outbreak of severe respiratory infections caused by the 2019 novel coronarvirus (2019-nCoV) has a clinical presentation resembling the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) outbreak that began in 2002, Chinese investigators caution.

By Jan. 2, 2020, 41 patients with confirmed 2019-nCoV had been admitted to a designated hospital in the city of Wuhan, Hubei Province, in central China. Thirteen required ICU admission and six died, reported Chaolin Huang, MD, from Jin Yin-tan Hospital in Wuhan, and colleagues.

“2019-nCoV still needs to be studied deeply in case it becomes a global health threat. Reliable quick pathogen tests and feasible differential diagnosis based on clinical description are crucial for clinicians in their first contact with suspected patients. Because of the pandemic potential of 2019-nCoV, careful surveillance is essential to monitor its future host adaption, viral evolution, infectivity, transmissibility, and pathogenicity,” they wrote in a review published online by The Lancet.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of Jan. 28, 2020, the total number of 2019-nCoV cases reported in the United States stood at five, but further cases of the infection – which Chinese health officials have confirmed can be transmitted person-to-person – are expected.

Dr. Huang and colleagues note that although most human coronavirus infections are mild, SARS-CoV and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) were responsible for more than 10,000 infections, with mortality rates ranging from 10% with SARS to 37% with MERS. To date, 2019-nCoV has “caused clusters of fatal pneumonia greatly resembling SARS-CoV,” they write.

The authors studied the epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, and radiological characteristics as well as treatments and clinical outcomes of 41 patients admitted or transferred to the Jin Yin-tan Hospital with laboratory-confirmed 2019-nCoV infections.

The median patient age was 49 years. Thirty of the 41 patients (73%) were male. Comorbid conditions included diabetes in 13 of the 41 patients (32%), hypertension in 6 (15%), and cardiovascular disease in 6.

In all 27 of the 41 patients had been exposed to the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, the suspected epicenter of the outbreak that was shut down by health authorities on Jan. 1 of this year.

The most common symptoms at the onset of the illness were fever in all but one of the 41 patients, cough in 31, and myalgia or fatigue in 18. Other, less frequent symptoms included sputum production in 11, headache in three, hemoptysis in two, and diarrhea in one.

“In this cohort, most patients presented with fever, dry cough, dyspnoea, and bilateral ground-glass opacities on chest CT scans. These features of 2019-nCoV infection bear some resemblance to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infections. However, few patients with 2019-nCoV infection had prominent upper respiratory tract signs and symptoms (e.g., rhinorrhoea, sneezing, or sore throat), indicating that the target cells might be located in the lower airway. Furthermore, 2019-nCoV patients rarely developed intestinal signs and symptoms (e.g., diarrhoea), whereas about 20%-25% of patients with MERS-CoV or SARS-CoV infection had diarrhoea.”

In all, 22 patients developed dyspnea, with a median time from illness onset to dyspnea of 8 days. The median time from illness onset to admission was 7 days, median time to shortness of breath was 8 days, median time to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was 9 days, and median time to both mechanical ventilation and ICU admission was 10.5 days.

All of the patients developed pneumonia with abnormal findings on chest CT scan. In addition, 12 patients developed ARDS, six had RNAaemia, five developed acute cardiac injury, and four developed a secondary infection. As noted before, 13 of the 14 patients were admitted to an ICU, and six died. RNAaemia is a positive result for real-time polymerase chain reaction in plasma samples. Patients admitted to the ICU had higher initial concentrations of multiple inflammatory cytokines than patients who did not need ICU care, “suggesting that the cytokine storm was associated with disease severity.”

All of the patients received empirical antibiotics, 38 were treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu), and 9 received systemic corticosteroids.

The investigators have initiated a randomized controlled trial of the antiviral agents lopinavir and ritonavir for patients hospitalized with 2019-nCoV infection.

The study was funded by the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, and Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission. All authors declared having no competing interests.

SOURCE: Huang C et al. Lancet. 2020 Jan 24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5.

FROM THE LANCET

Right hip and pelvic pain

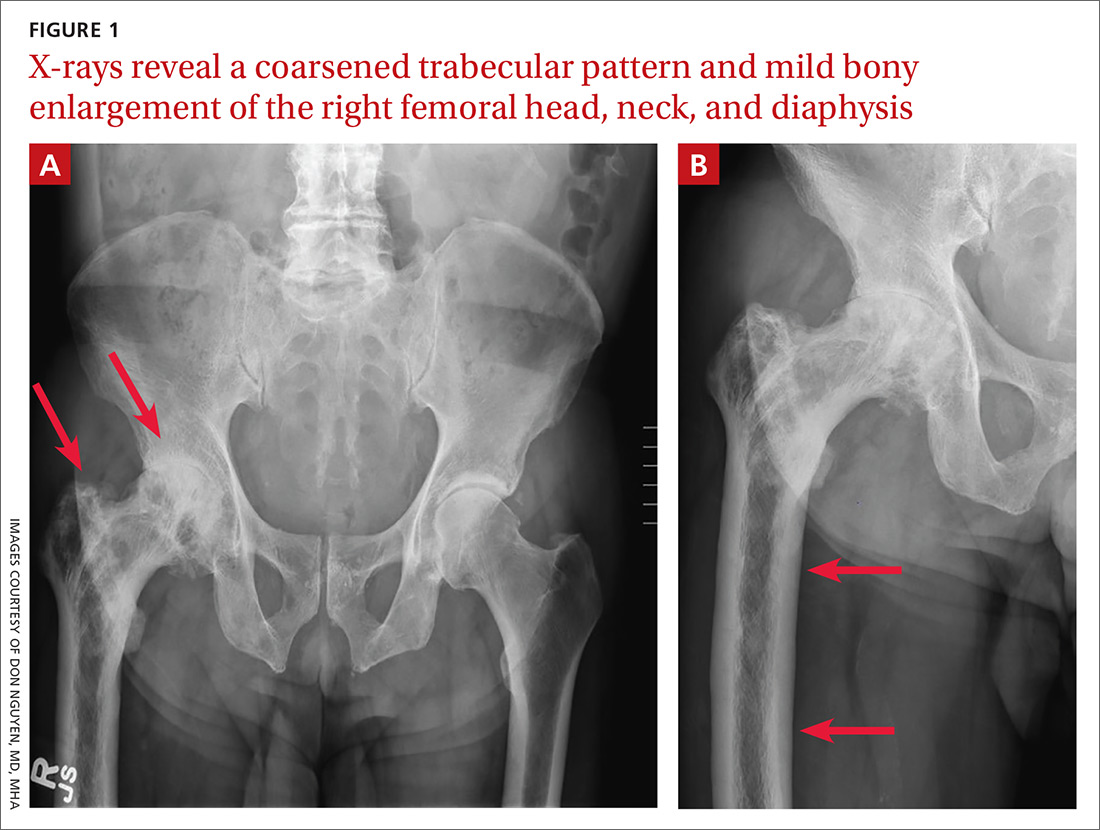

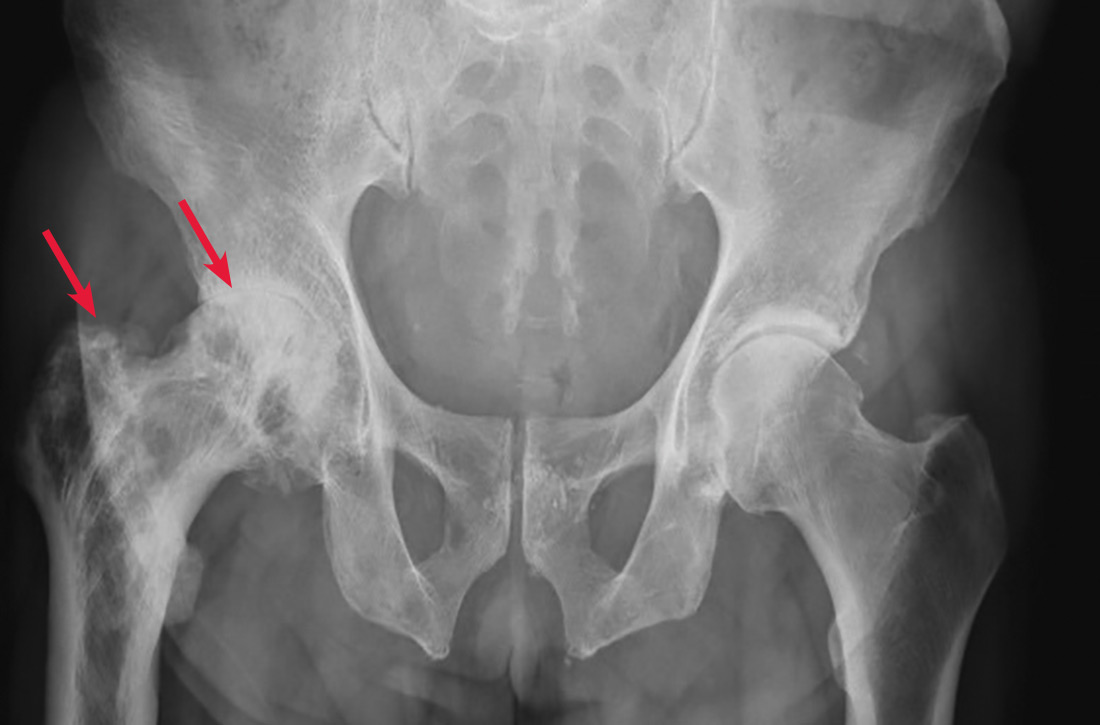

A 65-year-old man with a history of remote colon cancer, peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and bilateral knee replacements presented with right groin and hip pain of more than a year’s duration. The patient described his hip pain as aching and said that it had worsened over the previous 6 months, interfering with his sleep. He said the pain worsened following activity, and it briefly felt better following an intra-articular corticosteroid injection into his right hip. The patient denied recent trauma or fracture and said he had no scalp pain, hearing loss, or spinal tenderness. Physical examination showed limited range of motion of the right hip and mild tenderness to palpation. Laboratory values were within normal limits. X-rays of the pelvis (Figure 1A) and right hip (Figure 1B) were ordered.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Paget disease of bone

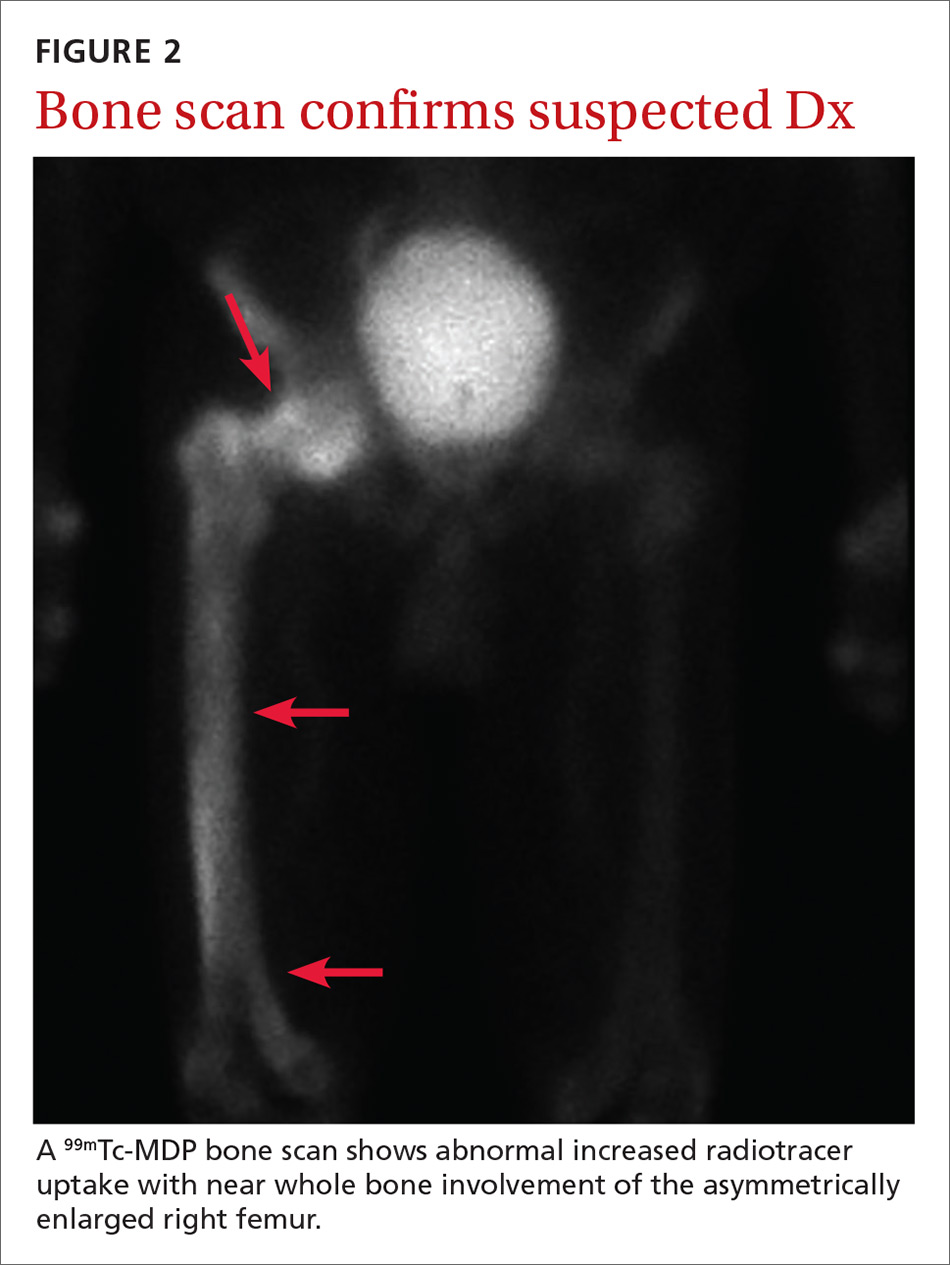

Based on the patient’s clinical history and initial imaging studies, which showed characteristic trabecular thickening with bony enlargement of the right femur, we suspected that he had Paget disease of bone. This was confirmed on subsequent whole-body 99mTc-MDP bone scan (Figure 2), which revealed corresponding diffuse increased radiotracer uptake of the right femur. There was no scintigraphic evidence of osseous involvement of the skull, spine, or pelvis.

Epidemiology/incidence. Paget disease, also known as osteitis deformans, is fairly common in the aging population, with a prevalence ranging from 2% to almost 10%.1,2 Although onset before age 40 is rare, the diagnosis should be considered in younger patients, given the high prevalence. There is a slight male predominance, and the disease is more common in the United Kingdom and Western Europe, as well as in countries settled by European immigrants.3

Both genetic and environmental causes are believed to contribute to the pathogenesis of Paget disease. Mutations in the gene encoding sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) can be seen in the autosomal dominant familial type (25%-50% of these cases), as well as in sporadic cases.4 Environmental influence has also been postulated as a possible cause, with a viral etiology (eg, chronic measles infection) being the most cited.5

Most patients will be asymptomatic

Paget disease can affect any bone in the body, although the skull, spine, pelvis, and long bones of the lower extremity are the most commonly affected sites.2 Most patients with Paget disease are asymptomatic. When symptoms are present, they either result from direct involvement of the bone or are secondary to bone overgrowth and deformity.

Direct involvement manifests as deep, constant bone pain that is worse at night. Symptoms related to bone overgrowth and deformity include spinal stenosis and related neurologic abnormalities, increased skull size, hearing loss (impingement of cranial nerve VIII), pathologic fracture (most commonly of the femur), and deformity such as protrusio acetabuli or femoral or tibial bowing.6 High-output heart failure and abnormalities in calcium and phosphate balance are uncommon but do occur.

Continue to: Degeneration into osteosarcoma...

Degeneration into osteosarcoma is a rare but almost invariably fatal complication of Paget disease, with an incidence of 0.2% to 1%.7 It clinically manifests as increased bone pain that is poorly responsive to medical therapy, local swelling, and pathologic fracture.8

Radiography is key to the work-up

The diagnosis of Paget disease is primarily radiographic. Early in the disease process, lytic lesions with thinning of the cortex will be noted. Later in the disease, there will be a mixed lytic/sclerotic phase, in which enlargement of the bone, a thickened cortex, and coarsened trabeculae are observed.

Characteristic radiographic findings. Focal lytic lesions in the skull are known as osteoporosis circumscripta. In the sclerotic phase, there is a thickening of the calvaria (termed “cotton wool”). Lesions involving the long bones will begin at the proximal or distal subchondral region and progress toward the diaphysis, with a sharp oblique delineation between involved bone and normal bone; this is described as “blade of grass” or “flame-shaped.”9

Within the pelvis, there will be cortical thickening and sclerosis with enlargement of the iliac wing. Within the spine, there will be enlarged vertebrae with a thickened sclerotic border, resulting in a “picture frame” appearance. Later in the disease, the sclerosis will involve the entire vertebrae (termed “ivory vertebra”).10

Additional testing options include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), bone scintigraphy, laboratory testing, and biopsy.

Continue to: MRI is recommended...

MRI is recommended when degeneration into osteosarcoma is present—indicated by permeative lesions with cortical breakthrough and a soft-tissue mass. MRI is helpful to further characterize the lesion. Absence of the normal fatty marrow on T1-weighted images would be concerning for tumor involvement.

Bone scintigraphy is used to determine the extent of disease. It will show increased uptake when the lesions are active.

Laboratory testing. Serum alkaline phosphatase (sAP) is frequently elevated in patients with Paget disease (normal range, 20-140 IU/L) and reflects the extent and activity of disease. However, this correlation is not always reliable; it depends on monostotic vs polyostotic involvement, as well as which bones are involved. For example, sAP levels may be markedly elevated when the skull is involved but normal when other bones are involved.11 In patients with elevated sAP, serum calcium and 25-hydroxyvitamin D measurements should be obtained in anticipation of bisphosphonate treatment.

Biopsy. If the radiographic findings are typical for Paget disease, bone biopsy is not indicated. However, the main competing diagnosis to consider is malignancy; in atypical cases when imaging is unable to elucidate an underlying tumor, biopsy would be warranted.

Differentiating Paget disease from sclerotic metastasis is important. In metastasis, there will be no trabecular coarsening or enlargement of the bone.

Continue to: Bisphosphonates are a Tx mainstay

Bisphosphonates are a Tx mainstay

Indications for treatment include symptomatic or asymptomatic disease with any of the following: elevated sAP with pagetic changes at sites where complications could occur; sAP more than 2 to 4 times the upper limit of normal; normal sAP with abnormal bone scintigraphy at a site where complications could occur; planned surgery at an active pagetic site; and hypercalcemia in association with immobilization in patients with polyostotic disease.

Newer generation nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates are the mainstay of treatment; they ease pain, slow bone turnover, and promote deposition of normal lamellar bone, which over time will normalize sAP levels.12 The most frequently used and studied bisphosphonates include oral alendronate, oral risedronate, and intravenous zoledronic acid.13

Prior to treatment initiation, the patient should have documented normal serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and these levels should be monitored throughout the first year of treatment. All patients should receive supplemental vitamin D and calcium to avoid hypocalcemia. sAP should be measured at 3 to 6 months to assess the initial response to therapy. Once the levels equilibrate, sAP can be measured once or twice a year to asses bone activity.14

Our patient was referred to Endocrinology for management of Paget disease of his right hip and femur. Lab values, including sAP and liver function test results, were normal. The patient was prescribed a zoledronic acid infusion (Reclast). At 4-week follow-up, the patient reported moderate relief of bone pain and improved sleep.

CORRESPONDENCE

Don Nguyen, MD, MHA, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Department of Radiology, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115; dnguyen42@bwh.harvard.edu

1. Altman RD, Bloch DA, Hochberg MC, et al. Prevalence of pelvic Paget’s disease of bone in the United States. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:461-465.

2. Singer F. Paget’s disease of bone. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al, eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

3. Merashli M, Jawad A. Paget’s disease of bone among various ethnic groups. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2015;15:E22-E26.

4. Hocking LJ, Lucas GJ, Daroszewska A, et al. Domain-specific mutations in sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) cause familial and sporadic Paget’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2735-2739.

5. Reddy SV, Kurihara N, Menaa C, et al. Osteoclasts formed by measles virus-infected osteoclast precursors from hCD46 transgenic mice express characteristics of pagetic osteoclasts. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2898-2905.

6. Moore TE, King AR, Kathol MH, et al. Sarcoma in Paget disease of bone: clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features in 22 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:1199-1203.

7. van Staa TP, Selby P, Leufkens HG, et al. Incidence and natural history of Paget’s disease of bone in England and Wales. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:465-471.

8. Hansen MF, Seton M, Merchant A. Osteosarcoma in Paget’s disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(suppl 2):P58-P63.

9. Wittenberg K. The blade of grass sign. Radiology. 2001;221:199-200.

10. Dennis JM. The solitary dense vertebral body. Radiology. 1961;77:618-621.

11. Seton M. Paget’s disease of bone. In: Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al, eds. Rheumatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby (Elsevier); 2008:2003.

12. Reid IR, Nicholson GC, Weinstein RS, et al. Biochemical and radiologic improvement in Paget’s disease of bone treated with alendronate: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Med. 1996;101:341-348.

13. Siris ES, Lyles KW, Singer FR, et al. Medical management of Paget’s disease of bone: indications for treatment and review of current therapies. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(suppl 2):P94-P98.

14. Alvarez L, Peris P, Guañabens N, et al. Long-term biochemical response after bisphosphonate therapy in Paget’s disease of bone: proposed intervals for monitoring treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:869-874.

A 65-year-old man with a history of remote colon cancer, peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and bilateral knee replacements presented with right groin and hip pain of more than a year’s duration. The patient described his hip pain as aching and said that it had worsened over the previous 6 months, interfering with his sleep. He said the pain worsened following activity, and it briefly felt better following an intra-articular corticosteroid injection into his right hip. The patient denied recent trauma or fracture and said he had no scalp pain, hearing loss, or spinal tenderness. Physical examination showed limited range of motion of the right hip and mild tenderness to palpation. Laboratory values were within normal limits. X-rays of the pelvis (Figure 1A) and right hip (Figure 1B) were ordered.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Paget disease of bone

Based on the patient’s clinical history and initial imaging studies, which showed characteristic trabecular thickening with bony enlargement of the right femur, we suspected that he had Paget disease of bone. This was confirmed on subsequent whole-body 99mTc-MDP bone scan (Figure 2), which revealed corresponding diffuse increased radiotracer uptake of the right femur. There was no scintigraphic evidence of osseous involvement of the skull, spine, or pelvis.

Epidemiology/incidence. Paget disease, also known as osteitis deformans, is fairly common in the aging population, with a prevalence ranging from 2% to almost 10%.1,2 Although onset before age 40 is rare, the diagnosis should be considered in younger patients, given the high prevalence. There is a slight male predominance, and the disease is more common in the United Kingdom and Western Europe, as well as in countries settled by European immigrants.3

Both genetic and environmental causes are believed to contribute to the pathogenesis of Paget disease. Mutations in the gene encoding sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) can be seen in the autosomal dominant familial type (25%-50% of these cases), as well as in sporadic cases.4 Environmental influence has also been postulated as a possible cause, with a viral etiology (eg, chronic measles infection) being the most cited.5

Most patients will be asymptomatic

Paget disease can affect any bone in the body, although the skull, spine, pelvis, and long bones of the lower extremity are the most commonly affected sites.2 Most patients with Paget disease are asymptomatic. When symptoms are present, they either result from direct involvement of the bone or are secondary to bone overgrowth and deformity.

Direct involvement manifests as deep, constant bone pain that is worse at night. Symptoms related to bone overgrowth and deformity include spinal stenosis and related neurologic abnormalities, increased skull size, hearing loss (impingement of cranial nerve VIII), pathologic fracture (most commonly of the femur), and deformity such as protrusio acetabuli or femoral or tibial bowing.6 High-output heart failure and abnormalities in calcium and phosphate balance are uncommon but do occur.

Continue to: Degeneration into osteosarcoma...

Degeneration into osteosarcoma is a rare but almost invariably fatal complication of Paget disease, with an incidence of 0.2% to 1%.7 It clinically manifests as increased bone pain that is poorly responsive to medical therapy, local swelling, and pathologic fracture.8

Radiography is key to the work-up

The diagnosis of Paget disease is primarily radiographic. Early in the disease process, lytic lesions with thinning of the cortex will be noted. Later in the disease, there will be a mixed lytic/sclerotic phase, in which enlargement of the bone, a thickened cortex, and coarsened trabeculae are observed.

Characteristic radiographic findings. Focal lytic lesions in the skull are known as osteoporosis circumscripta. In the sclerotic phase, there is a thickening of the calvaria (termed “cotton wool”). Lesions involving the long bones will begin at the proximal or distal subchondral region and progress toward the diaphysis, with a sharp oblique delineation between involved bone and normal bone; this is described as “blade of grass” or “flame-shaped.”9

Within the pelvis, there will be cortical thickening and sclerosis with enlargement of the iliac wing. Within the spine, there will be enlarged vertebrae with a thickened sclerotic border, resulting in a “picture frame” appearance. Later in the disease, the sclerosis will involve the entire vertebrae (termed “ivory vertebra”).10

Additional testing options include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), bone scintigraphy, laboratory testing, and biopsy.

Continue to: MRI is recommended...

MRI is recommended when degeneration into osteosarcoma is present—indicated by permeative lesions with cortical breakthrough and a soft-tissue mass. MRI is helpful to further characterize the lesion. Absence of the normal fatty marrow on T1-weighted images would be concerning for tumor involvement.

Bone scintigraphy is used to determine the extent of disease. It will show increased uptake when the lesions are active.

Laboratory testing. Serum alkaline phosphatase (sAP) is frequently elevated in patients with Paget disease (normal range, 20-140 IU/L) and reflects the extent and activity of disease. However, this correlation is not always reliable; it depends on monostotic vs polyostotic involvement, as well as which bones are involved. For example, sAP levels may be markedly elevated when the skull is involved but normal when other bones are involved.11 In patients with elevated sAP, serum calcium and 25-hydroxyvitamin D measurements should be obtained in anticipation of bisphosphonate treatment.

Biopsy. If the radiographic findings are typical for Paget disease, bone biopsy is not indicated. However, the main competing diagnosis to consider is malignancy; in atypical cases when imaging is unable to elucidate an underlying tumor, biopsy would be warranted.

Differentiating Paget disease from sclerotic metastasis is important. In metastasis, there will be no trabecular coarsening or enlargement of the bone.

Continue to: Bisphosphonates are a Tx mainstay

Bisphosphonates are a Tx mainstay

Indications for treatment include symptomatic or asymptomatic disease with any of the following: elevated sAP with pagetic changes at sites where complications could occur; sAP more than 2 to 4 times the upper limit of normal; normal sAP with abnormal bone scintigraphy at a site where complications could occur; planned surgery at an active pagetic site; and hypercalcemia in association with immobilization in patients with polyostotic disease.

Newer generation nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates are the mainstay of treatment; they ease pain, slow bone turnover, and promote deposition of normal lamellar bone, which over time will normalize sAP levels.12 The most frequently used and studied bisphosphonates include oral alendronate, oral risedronate, and intravenous zoledronic acid.13

Prior to treatment initiation, the patient should have documented normal serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and these levels should be monitored throughout the first year of treatment. All patients should receive supplemental vitamin D and calcium to avoid hypocalcemia. sAP should be measured at 3 to 6 months to assess the initial response to therapy. Once the levels equilibrate, sAP can be measured once or twice a year to asses bone activity.14

Our patient was referred to Endocrinology for management of Paget disease of his right hip and femur. Lab values, including sAP and liver function test results, were normal. The patient was prescribed a zoledronic acid infusion (Reclast). At 4-week follow-up, the patient reported moderate relief of bone pain and improved sleep.

CORRESPONDENCE

Don Nguyen, MD, MHA, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Department of Radiology, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115; dnguyen42@bwh.harvard.edu

A 65-year-old man with a history of remote colon cancer, peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and bilateral knee replacements presented with right groin and hip pain of more than a year’s duration. The patient described his hip pain as aching and said that it had worsened over the previous 6 months, interfering with his sleep. He said the pain worsened following activity, and it briefly felt better following an intra-articular corticosteroid injection into his right hip. The patient denied recent trauma or fracture and said he had no scalp pain, hearing loss, or spinal tenderness. Physical examination showed limited range of motion of the right hip and mild tenderness to palpation. Laboratory values were within normal limits. X-rays of the pelvis (Figure 1A) and right hip (Figure 1B) were ordered.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Paget disease of bone

Based on the patient’s clinical history and initial imaging studies, which showed characteristic trabecular thickening with bony enlargement of the right femur, we suspected that he had Paget disease of bone. This was confirmed on subsequent whole-body 99mTc-MDP bone scan (Figure 2), which revealed corresponding diffuse increased radiotracer uptake of the right femur. There was no scintigraphic evidence of osseous involvement of the skull, spine, or pelvis.

Epidemiology/incidence. Paget disease, also known as osteitis deformans, is fairly common in the aging population, with a prevalence ranging from 2% to almost 10%.1,2 Although onset before age 40 is rare, the diagnosis should be considered in younger patients, given the high prevalence. There is a slight male predominance, and the disease is more common in the United Kingdom and Western Europe, as well as in countries settled by European immigrants.3

Both genetic and environmental causes are believed to contribute to the pathogenesis of Paget disease. Mutations in the gene encoding sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) can be seen in the autosomal dominant familial type (25%-50% of these cases), as well as in sporadic cases.4 Environmental influence has also been postulated as a possible cause, with a viral etiology (eg, chronic measles infection) being the most cited.5

Most patients will be asymptomatic

Paget disease can affect any bone in the body, although the skull, spine, pelvis, and long bones of the lower extremity are the most commonly affected sites.2 Most patients with Paget disease are asymptomatic. When symptoms are present, they either result from direct involvement of the bone or are secondary to bone overgrowth and deformity.

Direct involvement manifests as deep, constant bone pain that is worse at night. Symptoms related to bone overgrowth and deformity include spinal stenosis and related neurologic abnormalities, increased skull size, hearing loss (impingement of cranial nerve VIII), pathologic fracture (most commonly of the femur), and deformity such as protrusio acetabuli or femoral or tibial bowing.6 High-output heart failure and abnormalities in calcium and phosphate balance are uncommon but do occur.

Continue to: Degeneration into osteosarcoma...

Degeneration into osteosarcoma is a rare but almost invariably fatal complication of Paget disease, with an incidence of 0.2% to 1%.7 It clinically manifests as increased bone pain that is poorly responsive to medical therapy, local swelling, and pathologic fracture.8

Radiography is key to the work-up

The diagnosis of Paget disease is primarily radiographic. Early in the disease process, lytic lesions with thinning of the cortex will be noted. Later in the disease, there will be a mixed lytic/sclerotic phase, in which enlargement of the bone, a thickened cortex, and coarsened trabeculae are observed.

Characteristic radiographic findings. Focal lytic lesions in the skull are known as osteoporosis circumscripta. In the sclerotic phase, there is a thickening of the calvaria (termed “cotton wool”). Lesions involving the long bones will begin at the proximal or distal subchondral region and progress toward the diaphysis, with a sharp oblique delineation between involved bone and normal bone; this is described as “blade of grass” or “flame-shaped.”9

Within the pelvis, there will be cortical thickening and sclerosis with enlargement of the iliac wing. Within the spine, there will be enlarged vertebrae with a thickened sclerotic border, resulting in a “picture frame” appearance. Later in the disease, the sclerosis will involve the entire vertebrae (termed “ivory vertebra”).10

Additional testing options include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), bone scintigraphy, laboratory testing, and biopsy.

Continue to: MRI is recommended...

MRI is recommended when degeneration into osteosarcoma is present—indicated by permeative lesions with cortical breakthrough and a soft-tissue mass. MRI is helpful to further characterize the lesion. Absence of the normal fatty marrow on T1-weighted images would be concerning for tumor involvement.

Bone scintigraphy is used to determine the extent of disease. It will show increased uptake when the lesions are active.

Laboratory testing. Serum alkaline phosphatase (sAP) is frequently elevated in patients with Paget disease (normal range, 20-140 IU/L) and reflects the extent and activity of disease. However, this correlation is not always reliable; it depends on monostotic vs polyostotic involvement, as well as which bones are involved. For example, sAP levels may be markedly elevated when the skull is involved but normal when other bones are involved.11 In patients with elevated sAP, serum calcium and 25-hydroxyvitamin D measurements should be obtained in anticipation of bisphosphonate treatment.

Biopsy. If the radiographic findings are typical for Paget disease, bone biopsy is not indicated. However, the main competing diagnosis to consider is malignancy; in atypical cases when imaging is unable to elucidate an underlying tumor, biopsy would be warranted.

Differentiating Paget disease from sclerotic metastasis is important. In metastasis, there will be no trabecular coarsening or enlargement of the bone.

Continue to: Bisphosphonates are a Tx mainstay

Bisphosphonates are a Tx mainstay

Indications for treatment include symptomatic or asymptomatic disease with any of the following: elevated sAP with pagetic changes at sites where complications could occur; sAP more than 2 to 4 times the upper limit of normal; normal sAP with abnormal bone scintigraphy at a site where complications could occur; planned surgery at an active pagetic site; and hypercalcemia in association with immobilization in patients with polyostotic disease.

Newer generation nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates are the mainstay of treatment; they ease pain, slow bone turnover, and promote deposition of normal lamellar bone, which over time will normalize sAP levels.12 The most frequently used and studied bisphosphonates include oral alendronate, oral risedronate, and intravenous zoledronic acid.13

Prior to treatment initiation, the patient should have documented normal serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and these levels should be monitored throughout the first year of treatment. All patients should receive supplemental vitamin D and calcium to avoid hypocalcemia. sAP should be measured at 3 to 6 months to assess the initial response to therapy. Once the levels equilibrate, sAP can be measured once or twice a year to asses bone activity.14

Our patient was referred to Endocrinology for management of Paget disease of his right hip and femur. Lab values, including sAP and liver function test results, were normal. The patient was prescribed a zoledronic acid infusion (Reclast). At 4-week follow-up, the patient reported moderate relief of bone pain and improved sleep.

CORRESPONDENCE

Don Nguyen, MD, MHA, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Department of Radiology, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115; dnguyen42@bwh.harvard.edu

1. Altman RD, Bloch DA, Hochberg MC, et al. Prevalence of pelvic Paget’s disease of bone in the United States. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:461-465.

2. Singer F. Paget’s disease of bone. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al, eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

3. Merashli M, Jawad A. Paget’s disease of bone among various ethnic groups. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2015;15:E22-E26.

4. Hocking LJ, Lucas GJ, Daroszewska A, et al. Domain-specific mutations in sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) cause familial and sporadic Paget’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2735-2739.

5. Reddy SV, Kurihara N, Menaa C, et al. Osteoclasts formed by measles virus-infected osteoclast precursors from hCD46 transgenic mice express characteristics of pagetic osteoclasts. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2898-2905.

6. Moore TE, King AR, Kathol MH, et al. Sarcoma in Paget disease of bone: clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features in 22 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:1199-1203.

7. van Staa TP, Selby P, Leufkens HG, et al. Incidence and natural history of Paget’s disease of bone in England and Wales. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:465-471.

8. Hansen MF, Seton M, Merchant A. Osteosarcoma in Paget’s disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(suppl 2):P58-P63.

9. Wittenberg K. The blade of grass sign. Radiology. 2001;221:199-200.

10. Dennis JM. The solitary dense vertebral body. Radiology. 1961;77:618-621.

11. Seton M. Paget’s disease of bone. In: Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al, eds. Rheumatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby (Elsevier); 2008:2003.

12. Reid IR, Nicholson GC, Weinstein RS, et al. Biochemical and radiologic improvement in Paget’s disease of bone treated with alendronate: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Med. 1996;101:341-348.

13. Siris ES, Lyles KW, Singer FR, et al. Medical management of Paget’s disease of bone: indications for treatment and review of current therapies. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(suppl 2):P94-P98.

14. Alvarez L, Peris P, Guañabens N, et al. Long-term biochemical response after bisphosphonate therapy in Paget’s disease of bone: proposed intervals for monitoring treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:869-874.

1. Altman RD, Bloch DA, Hochberg MC, et al. Prevalence of pelvic Paget’s disease of bone in the United States. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:461-465.

2. Singer F. Paget’s disease of bone. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al, eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

3. Merashli M, Jawad A. Paget’s disease of bone among various ethnic groups. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2015;15:E22-E26.

4. Hocking LJ, Lucas GJ, Daroszewska A, et al. Domain-specific mutations in sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) cause familial and sporadic Paget’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2735-2739.

5. Reddy SV, Kurihara N, Menaa C, et al. Osteoclasts formed by measles virus-infected osteoclast precursors from hCD46 transgenic mice express characteristics of pagetic osteoclasts. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2898-2905.

6. Moore TE, King AR, Kathol MH, et al. Sarcoma in Paget disease of bone: clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features in 22 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:1199-1203.

7. van Staa TP, Selby P, Leufkens HG, et al. Incidence and natural history of Paget’s disease of bone in England and Wales. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:465-471.

8. Hansen MF, Seton M, Merchant A. Osteosarcoma in Paget’s disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(suppl 2):P58-P63.

9. Wittenberg K. The blade of grass sign. Radiology. 2001;221:199-200.

10. Dennis JM. The solitary dense vertebral body. Radiology. 1961;77:618-621.

11. Seton M. Paget’s disease of bone. In: Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al, eds. Rheumatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby (Elsevier); 2008:2003.

12. Reid IR, Nicholson GC, Weinstein RS, et al. Biochemical and radiologic improvement in Paget’s disease of bone treated with alendronate: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Med. 1996;101:341-348.

13. Siris ES, Lyles KW, Singer FR, et al. Medical management of Paget’s disease of bone: indications for treatment and review of current therapies. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(suppl 2):P94-P98.

14. Alvarez L, Peris P, Guañabens N, et al. Long-term biochemical response after bisphosphonate therapy in Paget’s disease of bone: proposed intervals for monitoring treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:869-874.

33-year-old man • flaccid paralysis in limbs • 30-lb weight loss • thyromegaly without nodules • Dx?

THE CASE

A 33-year-old Hispanic man with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with generalized flaccid paralysis in both arms and legs. Two days before, he had been working on a construction site in hot weather. The following day, he woke up with very little energy or strength to perform his daily activities, and he had pain in the inguinal area and both calves. He denied taking any medications or supplements.

The patient had complete muscle weakness and was unable to move his arms and legs. He reported dysphagia and an unintentional weight loss of 30 lb during the previous month.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were within the normal range, and mild thyromegaly without nodules was present. Neurologic examination revealed decreased deep tendon reflexes with intact sensation. Muscle strength in his arms and legs was 0/5.

Initial laboratory test results included a potassium level of 2.2 mEq/L (normal range, 3.5–5 mEq/L) and normal acid-basic status that was confirmed by an arterial blood gas measurement. Serum magnesium was 1.6 mg/dL (normal range, 1.6–2.5 mg/dL); phosphorus, 1.9 mg/dL (normal range, 2.7–4.5 mg/dL); and random urinary potassium, 16 mEq/L (normal range, 25–125 mEq/L). An initial chest x-ray was normal, and an electrocardiogram showed a prolonged QT interval, flattening of the T wave, and a prominent U wave consistent with hypokalemia.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The initial clinical diagnosis was hypokalemic paralysis. The patient was treated with intravenous (IV) potassium chloride 40 mEq

Evaluation of the patient’s hypokalemia revealed the following: thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level, < 0.01 microIU/mL (normal range, 0.27–4.2 microIU/mL); free T4 (thyroxine) level, 4.47 ng/dL (normal range, 0.08–1.70 ng/dL); total T3 (triiodothyronine) level, 17.5 ng/dL (normal range, 2.6–4.4 ng/dL).

The patient was diagnosed with hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HPP) secondary to thyrotoxicosis, also known as thyrotoxicosis periodic paralysis (TPP). His hyperthyroidism was treated with oral atenolol 25 mg/d and oral methimazole 10 mg tid.

Continue to: Within a few hours...

Within a few hours of this treatment, the patient experienced significant improvement in muscle strength and complete resolution of weakness in his arms and legs. Serial measurements of potassium levels normalized.

Further workup revealed that the patient’s thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) was 4.2 on the TSI index (normal, ≤ 1.3) and his thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody level was 133.4 IU/mL (normal, < 34 IU/mL). Ultrasonography showed decreased echogenicity of the thyroid gland, consistent with the acute phase of Hashimoto thyroiditis or Graves disease.

The patient was unaware that he had any thyroid disorder previously. He was a private-pay, undocumented immigrant and did not have a regular primary care physician. On discharge, he was referred to a local primary care physician as well as an endocrinologist. He was discharged on atenolol and methimazole.

DISCUSSION

A rare neuromuscular disorder known as periodic paralysis can be precipitated by a hypokalemic or hyperkalemic state; HPP is more common and can be either familial (a defect in the gene) or acquired (secondary to thyrotoxicosis; TPP).1,2 In both forms of periodic paralysis, patients present with hypokalemia and paralysis. Physicians need to look closely at thyroid lab test results so as not to miss the cause of the paralysis.

TPP is most commonly seen in Asian populations, and 95% of cases reported occur in males, despite the higher incidence of hyperthyroidism in females.3 TPP can be precipitated by emotional stress, steroid use, beta-adrenergic bronchodilators, heavy exercise, fasting, or high-carbohydrate meals.2-4 In our patient, heavy exercise and fasting likely were the triggers.

Continue to: The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia...

The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia in TPP is thought to involve the sodium/potassium–adenosine triphosphatase (Na+/K+–ATPase) pump. This pump activity is increased in skeletal muscle and platelets in patients with TPP vs patients with thyrotoxicosis alone.3,5

The role of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis. Most acquired cases of TPP are mainly secondary to Graves disease with elevated levels of TSI and mildly elevated or normal levels of TPO. In this case, the patient was in the acute phase of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis (“hashitoxicosis”) with elevated levels of TPO and only mildly elevated TSI.Imaging studies to support the diagnosis, such as a thyroid uptake scan or ultrasonography, are not necessary to determine the cause of thyrotoxicosis. In the absence of test results for TPO and TSI antibodies, however, a scan can be helpful.6,7

Treatment of TPP consists of early recognition and supportive management by correcting the potassium deficit; failure to do so could cause severe complications, such as respiratory failure and psychosis.8 Because of the risk for rebound hyperkalemia, serial potassium levels must be measured until a stable potassium level in the normal range is achieved.

Nonselective beta-blockers, such as propranolol (3 mg/kg) 4 times per day, have been reported to ameliorate the periodic paralysis and prevent rebound hyperkalemia.9 Finally, restoring a euthyroid state will prevent the patient from experiencing future attacks.

THE TAKEAWAY

Few medical conditions result in complete muscle paralysis in a matter of hours. Clinicians should consider the possibility of TPP in any patient who presents with acute onset of paralysis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jorge Luis Chavez, MD; 8405 E. San Pedro Drive, Scottsdale, AZ 85258; jorgeluischavezmd@yahoo.com.

1. Fontaine B. Periodic paralysis. Adv Genet. 2008;63:3-23.

2. Ober KP. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the United States. Report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore).1992;71:109-120.

3. Lin YF, Wu CC, Pei D, et al. Diagnosing thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:339-342.

4. Yu TS, Tseng CF, Chuang YY, et al. Potassium chloride supplementation alone may not improve hypokalemia in thyrotoxic hypokalemic periodic paralysis. J Emerg Med. 2007;32:263-265.

5. Chan A, Shinde R, Chow CC, et al. In vivo and in vitro sodium pump activity in subjects with thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. BMJ. 1991;303:1096-1099.

6. Harsch IA, Hahn EG, Strobel D. Hashitoxicosis—three cases and a review of the literature. Eur Endocrinol. 2008;4:70-72. 7. Pou Ucha JL. Imaging in hyperthyroidism. In: Díaz-Soto G, ed. Thyroid Disorders: Focus on Hyperthyroidism. InTechOpen; 2014. www.intechopen.com/books/thyroid-disorders-focus-on-hyperthyroidism/imaging-in-hyperthyroidism. Accessed January 14, 2020.

8. Abbasi B, Sharif Z, Sprabery LR. Hypokalemic thyrotoxic periodic paralysis with thyrotoxic psychosis and hypercapnic respiratory failure. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:147-153.

9. Lin SH, Lin YF. Propranolol rapidly reverses paralysis, hypokalemia, and hypophosphatemia in thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:620-623.

THE CASE

A 33-year-old Hispanic man with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with generalized flaccid paralysis in both arms and legs. Two days before, he had been working on a construction site in hot weather. The following day, he woke up with very little energy or strength to perform his daily activities, and he had pain in the inguinal area and both calves. He denied taking any medications or supplements.

The patient had complete muscle weakness and was unable to move his arms and legs. He reported dysphagia and an unintentional weight loss of 30 lb during the previous month.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were within the normal range, and mild thyromegaly without nodules was present. Neurologic examination revealed decreased deep tendon reflexes with intact sensation. Muscle strength in his arms and legs was 0/5.

Initial laboratory test results included a potassium level of 2.2 mEq/L (normal range, 3.5–5 mEq/L) and normal acid-basic status that was confirmed by an arterial blood gas measurement. Serum magnesium was 1.6 mg/dL (normal range, 1.6–2.5 mg/dL); phosphorus, 1.9 mg/dL (normal range, 2.7–4.5 mg/dL); and random urinary potassium, 16 mEq/L (normal range, 25–125 mEq/L). An initial chest x-ray was normal, and an electrocardiogram showed a prolonged QT interval, flattening of the T wave, and a prominent U wave consistent with hypokalemia.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The initial clinical diagnosis was hypokalemic paralysis. The patient was treated with intravenous (IV) potassium chloride 40 mEq

Evaluation of the patient’s hypokalemia revealed the following: thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level, < 0.01 microIU/mL (normal range, 0.27–4.2 microIU/mL); free T4 (thyroxine) level, 4.47 ng/dL (normal range, 0.08–1.70 ng/dL); total T3 (triiodothyronine) level, 17.5 ng/dL (normal range, 2.6–4.4 ng/dL).

The patient was diagnosed with hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HPP) secondary to thyrotoxicosis, also known as thyrotoxicosis periodic paralysis (TPP). His hyperthyroidism was treated with oral atenolol 25 mg/d and oral methimazole 10 mg tid.

Continue to: Within a few hours...

Within a few hours of this treatment, the patient experienced significant improvement in muscle strength and complete resolution of weakness in his arms and legs. Serial measurements of potassium levels normalized.

Further workup revealed that the patient’s thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) was 4.2 on the TSI index (normal, ≤ 1.3) and his thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody level was 133.4 IU/mL (normal, < 34 IU/mL). Ultrasonography showed decreased echogenicity of the thyroid gland, consistent with the acute phase of Hashimoto thyroiditis or Graves disease.

The patient was unaware that he had any thyroid disorder previously. He was a private-pay, undocumented immigrant and did not have a regular primary care physician. On discharge, he was referred to a local primary care physician as well as an endocrinologist. He was discharged on atenolol and methimazole.

DISCUSSION

A rare neuromuscular disorder known as periodic paralysis can be precipitated by a hypokalemic or hyperkalemic state; HPP is more common and can be either familial (a defect in the gene) or acquired (secondary to thyrotoxicosis; TPP).1,2 In both forms of periodic paralysis, patients present with hypokalemia and paralysis. Physicians need to look closely at thyroid lab test results so as not to miss the cause of the paralysis.

TPP is most commonly seen in Asian populations, and 95% of cases reported occur in males, despite the higher incidence of hyperthyroidism in females.3 TPP can be precipitated by emotional stress, steroid use, beta-adrenergic bronchodilators, heavy exercise, fasting, or high-carbohydrate meals.2-4 In our patient, heavy exercise and fasting likely were the triggers.

Continue to: The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia...

The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia in TPP is thought to involve the sodium/potassium–adenosine triphosphatase (Na+/K+–ATPase) pump. This pump activity is increased in skeletal muscle and platelets in patients with TPP vs patients with thyrotoxicosis alone.3,5

The role of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis. Most acquired cases of TPP are mainly secondary to Graves disease with elevated levels of TSI and mildly elevated or normal levels of TPO. In this case, the patient was in the acute phase of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis (“hashitoxicosis”) with elevated levels of TPO and only mildly elevated TSI.Imaging studies to support the diagnosis, such as a thyroid uptake scan or ultrasonography, are not necessary to determine the cause of thyrotoxicosis. In the absence of test results for TPO and TSI antibodies, however, a scan can be helpful.6,7

Treatment of TPP consists of early recognition and supportive management by correcting the potassium deficit; failure to do so could cause severe complications, such as respiratory failure and psychosis.8 Because of the risk for rebound hyperkalemia, serial potassium levels must be measured until a stable potassium level in the normal range is achieved.

Nonselective beta-blockers, such as propranolol (3 mg/kg) 4 times per day, have been reported to ameliorate the periodic paralysis and prevent rebound hyperkalemia.9 Finally, restoring a euthyroid state will prevent the patient from experiencing future attacks.

THE TAKEAWAY

Few medical conditions result in complete muscle paralysis in a matter of hours. Clinicians should consider the possibility of TPP in any patient who presents with acute onset of paralysis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jorge Luis Chavez, MD; 8405 E. San Pedro Drive, Scottsdale, AZ 85258; jorgeluischavezmd@yahoo.com.

THE CASE

A 33-year-old Hispanic man with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with generalized flaccid paralysis in both arms and legs. Two days before, he had been working on a construction site in hot weather. The following day, he woke up with very little energy or strength to perform his daily activities, and he had pain in the inguinal area and both calves. He denied taking any medications or supplements.

The patient had complete muscle weakness and was unable to move his arms and legs. He reported dysphagia and an unintentional weight loss of 30 lb during the previous month.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were within the normal range, and mild thyromegaly without nodules was present. Neurologic examination revealed decreased deep tendon reflexes with intact sensation. Muscle strength in his arms and legs was 0/5.

Initial laboratory test results included a potassium level of 2.2 mEq/L (normal range, 3.5–5 mEq/L) and normal acid-basic status that was confirmed by an arterial blood gas measurement. Serum magnesium was 1.6 mg/dL (normal range, 1.6–2.5 mg/dL); phosphorus, 1.9 mg/dL (normal range, 2.7–4.5 mg/dL); and random urinary potassium, 16 mEq/L (normal range, 25–125 mEq/L). An initial chest x-ray was normal, and an electrocardiogram showed a prolonged QT interval, flattening of the T wave, and a prominent U wave consistent with hypokalemia.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The initial clinical diagnosis was hypokalemic paralysis. The patient was treated with intravenous (IV) potassium chloride 40 mEq

Evaluation of the patient’s hypokalemia revealed the following: thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level, < 0.01 microIU/mL (normal range, 0.27–4.2 microIU/mL); free T4 (thyroxine) level, 4.47 ng/dL (normal range, 0.08–1.70 ng/dL); total T3 (triiodothyronine) level, 17.5 ng/dL (normal range, 2.6–4.4 ng/dL).

The patient was diagnosed with hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HPP) secondary to thyrotoxicosis, also known as thyrotoxicosis periodic paralysis (TPP). His hyperthyroidism was treated with oral atenolol 25 mg/d and oral methimazole 10 mg tid.

Continue to: Within a few hours...

Within a few hours of this treatment, the patient experienced significant improvement in muscle strength and complete resolution of weakness in his arms and legs. Serial measurements of potassium levels normalized.

Further workup revealed that the patient’s thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) was 4.2 on the TSI index (normal, ≤ 1.3) and his thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody level was 133.4 IU/mL (normal, < 34 IU/mL). Ultrasonography showed decreased echogenicity of the thyroid gland, consistent with the acute phase of Hashimoto thyroiditis or Graves disease.

The patient was unaware that he had any thyroid disorder previously. He was a private-pay, undocumented immigrant and did not have a regular primary care physician. On discharge, he was referred to a local primary care physician as well as an endocrinologist. He was discharged on atenolol and methimazole.

DISCUSSION

A rare neuromuscular disorder known as periodic paralysis can be precipitated by a hypokalemic or hyperkalemic state; HPP is more common and can be either familial (a defect in the gene) or acquired (secondary to thyrotoxicosis; TPP).1,2 In both forms of periodic paralysis, patients present with hypokalemia and paralysis. Physicians need to look closely at thyroid lab test results so as not to miss the cause of the paralysis.

TPP is most commonly seen in Asian populations, and 95% of cases reported occur in males, despite the higher incidence of hyperthyroidism in females.3 TPP can be precipitated by emotional stress, steroid use, beta-adrenergic bronchodilators, heavy exercise, fasting, or high-carbohydrate meals.2-4 In our patient, heavy exercise and fasting likely were the triggers.

Continue to: The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia...

The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia in TPP is thought to involve the sodium/potassium–adenosine triphosphatase (Na+/K+–ATPase) pump. This pump activity is increased in skeletal muscle and platelets in patients with TPP vs patients with thyrotoxicosis alone.3,5

The role of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis. Most acquired cases of TPP are mainly secondary to Graves disease with elevated levels of TSI and mildly elevated or normal levels of TPO. In this case, the patient was in the acute phase of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis (“hashitoxicosis”) with elevated levels of TPO and only mildly elevated TSI.Imaging studies to support the diagnosis, such as a thyroid uptake scan or ultrasonography, are not necessary to determine the cause of thyrotoxicosis. In the absence of test results for TPO and TSI antibodies, however, a scan can be helpful.6,7

Treatment of TPP consists of early recognition and supportive management by correcting the potassium deficit; failure to do so could cause severe complications, such as respiratory failure and psychosis.8 Because of the risk for rebound hyperkalemia, serial potassium levels must be measured until a stable potassium level in the normal range is achieved.

Nonselective beta-blockers, such as propranolol (3 mg/kg) 4 times per day, have been reported to ameliorate the periodic paralysis and prevent rebound hyperkalemia.9 Finally, restoring a euthyroid state will prevent the patient from experiencing future attacks.

THE TAKEAWAY

Few medical conditions result in complete muscle paralysis in a matter of hours. Clinicians should consider the possibility of TPP in any patient who presents with acute onset of paralysis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jorge Luis Chavez, MD; 8405 E. San Pedro Drive, Scottsdale, AZ 85258; jorgeluischavezmd@yahoo.com.

1. Fontaine B. Periodic paralysis. Adv Genet. 2008;63:3-23.

2. Ober KP. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the United States. Report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore).1992;71:109-120.

3. Lin YF, Wu CC, Pei D, et al. Diagnosing thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:339-342.

4. Yu TS, Tseng CF, Chuang YY, et al. Potassium chloride supplementation alone may not improve hypokalemia in thyrotoxic hypokalemic periodic paralysis. J Emerg Med. 2007;32:263-265.

5. Chan A, Shinde R, Chow CC, et al. In vivo and in vitro sodium pump activity in subjects with thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. BMJ. 1991;303:1096-1099.

6. Harsch IA, Hahn EG, Strobel D. Hashitoxicosis—three cases and a review of the literature. Eur Endocrinol. 2008;4:70-72. 7. Pou Ucha JL. Imaging in hyperthyroidism. In: Díaz-Soto G, ed. Thyroid Disorders: Focus on Hyperthyroidism. InTechOpen; 2014. www.intechopen.com/books/thyroid-disorders-focus-on-hyperthyroidism/imaging-in-hyperthyroidism. Accessed January 14, 2020.

8. Abbasi B, Sharif Z, Sprabery LR. Hypokalemic thyrotoxic periodic paralysis with thyrotoxic psychosis and hypercapnic respiratory failure. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:147-153.

9. Lin SH, Lin YF. Propranolol rapidly reverses paralysis, hypokalemia, and hypophosphatemia in thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:620-623.

1. Fontaine B. Periodic paralysis. Adv Genet. 2008;63:3-23.

2. Ober KP. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the United States. Report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore).1992;71:109-120.

3. Lin YF, Wu CC, Pei D, et al. Diagnosing thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:339-342.

4. Yu TS, Tseng CF, Chuang YY, et al. Potassium chloride supplementation alone may not improve hypokalemia in thyrotoxic hypokalemic periodic paralysis. J Emerg Med. 2007;32:263-265.

5. Chan A, Shinde R, Chow CC, et al. In vivo and in vitro sodium pump activity in subjects with thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. BMJ. 1991;303:1096-1099.

6. Harsch IA, Hahn EG, Strobel D. Hashitoxicosis—three cases and a review of the literature. Eur Endocrinol. 2008;4:70-72. 7. Pou Ucha JL. Imaging in hyperthyroidism. In: Díaz-Soto G, ed. Thyroid Disorders: Focus on Hyperthyroidism. InTechOpen; 2014. www.intechopen.com/books/thyroid-disorders-focus-on-hyperthyroidism/imaging-in-hyperthyroidism. Accessed January 14, 2020.

8. Abbasi B, Sharif Z, Sprabery LR. Hypokalemic thyrotoxic periodic paralysis with thyrotoxic psychosis and hypercapnic respiratory failure. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:147-153.

9. Lin SH, Lin YF. Propranolol rapidly reverses paralysis, hypokalemia, and hypophosphatemia in thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:620-623.

A better approach to preventing active TB?

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 27-year-old daycare worker was tested for tuberculosis (TB) as part of a recent work physical. She presents to your office for follow-up for her positive purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test. You confirm the result with a quantiferon gold test and ensure she does not have active TB. What medication should you prescribe to treat her latent TB infection (LTBI)?

In 2017, there were 9093 cases of new active TB in the United States.2 It’s estimated that one-fourth of the world’s population has latent TB.3 Identifying and treating latent TB infection is vital to achieving TB’s elimination.4,5

Primary care clinicians are at the forefront of screening high-risk populations for TB. Once identified, treating LTBI can be challenging for providers and patients. Treatment guidelines recommend 4 to 9 months of daily isoniazid.5-8 Shorter treatment regimens were recommended previously; they tended to be rigorous, to involve multiple drugs, and to require high adherence rates. As such, they included directly observed therapy, which prevented widespread adoption.

Consequently, the mainstay for treating LTBI has been 9 months of daily isoniazid. However, isoniazid use is limited by hepatoxicity and by suboptimal treatment completion rates. A 2018 retrospective analysis of patients treated for LTBI reported a completion rate of only 49% for 9 months of isoniazid.9 Additionally, a Cochrane review last updated in 2013 suggests that shorter courses of rifampin are similar in efficacy to isoniazid (although with a wide confidence interval [CI]), and likely have higher adherence rates.10

STUDY SUMMARY

Rifampin is as effective as isoniazid with fewer adverse effects

The study by Menzies et al1 was a multisite, 9-country, open-label, randomized controlled trial (RCT) that compared 4 months of daily rifampin to 9 months of daily isoniazid for the treatment of LTBI in adults. Participants were eligible if they had a positive tuberculin skin test or interferon-gamma-release assay, were ≥ 18 years of age, had an increased risk for reactivation of active TB, and if their health care provider had recommended treatment with isoniazid. Exclusion criteria included current pregnancy or plans to become pregnant, exposure to a patient with TB whose isolates were resistant to either trial drug, an allergy to either of the trial drugs, use of a medication with serious potential interactions with the trial drugs, or current active TB.

Method, outcomes, patient characteristics. Patients received either isoniazid 5 mg/kg body weight (maximum dose 300 mg) daily for 9 months or rifampin 10 mg/kg (maximum dose 600 mg) daily for 4 months and were followed for 28 months. Patients in the isoniazid group also received pyridoxine (vitamin B6) if they were at risk for neuropathy. The primary outcome was the rate of active TB. Secondary outcomes included adverse events, medication regimen completion rate, and drug resistance, among others.

A total of 2989 patients were treated with isoniazid; 3023 patients were treated with rifampin. The mean age of the participants was 38.4 years, 41% of the population was male, and 71% of the groups had confirmed active TB in close contacts.

Continue to: Results

Results. Overall, rates of active TB were low with 9 cases in the isoniazid group and 8 in the rifampin group. In the intention-to-treat analysis, the rate difference for confirmed active TB was < 0.01 cases per 100 person-years (95% CI; −0.14 to 0.16). This met the prespecified noninferiority endpoint, but did not show superiority. A total of 79% of patients treated with rifampin vs 63% treated with isoniazid completed their respective medication courses (difference of 15.1 percentage points; 95% CI, 12.7-17.4; P < .001). Compared with patients in the isoniazid group, those taking rifampin had fewer adverse events, leading to discontinuation (5.6% vs 2.8%).

WHAT’S NEW?

First high-quality study to show that less is more

This is the first large, high-quality study to show that a shorter (4 month) rifampin-based regimen is not inferior to a longer (9 months) isoniazid-based regimen for the treatment of LTBI, and that rifampin is associated with improved adherence and fewer adverse events.

CAVEATS

Low rate of active TB infection and potential bias

The current study had lower-than-anticipated rates of active TB infection, which made the study’s conclusions less compelling. This may have been because of a small number of patients with human immunodeficiency virus enrolled in the study and/or that even participants who discontinued treatment received a median of 3 months of partial treatment.

In addition, the study was an open-label RCT, subjecting it to potential bias. However, the diagnosis of active TB and attribution of adverse events were made by an independent, blinded review panel.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

No challenges to speak of

We see no challenges to implementing this recommendation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Menzies D, Adjobimey M, Ruslami R, et al. Four months of rifampin or nine months of isoniazid for latent tuberculosis in adults. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:440-453.

2. Stewart RJ, Tsang CA, Pratt RH, et al. Tuberculosis — United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:317-323.

3. Houben RM, Dodd PJ. The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: a re-estimation using mathematical modeling. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002152.

4. Lönnroth K, Migliori GB, Abubakar I, et al. Towards tuberculosis elimination: an action framework for low-incidence countries. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:928-952.

5. Uplekar M, Weil D, Lonnroth K, et al. WHO’s new end TB strategy. Lancet. 2015;385:1799-1801.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment regimens for latent TB infection (LTBI). Last reviewed April 5, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm. Accessed January 15, 2020.

7. World Health Organization. Latent TB infection: updated and consolidated guidelines for programmatic management. 2018. Publication no. WHO/CDS/TB/2018.4. https://www.who.int/tb/publications/2018/latent-tuberculosis-infection/en/. Accessed January 15, 2020.

8. Borisov AS, Bamrah Morris S, Njie GJ, et al. Update of recommendations for use of once-weekly isoniazid-rifapentine regimen to treat latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:723-726.

9. Macaraig MM, Jalees M, Lam C, et al. Improved treatment completion with shorter treatment regimens for latent tuberculous infection. Int J Tuber Lung Dis. 2018;22:1344-1349. 10. Sharma SK, Sharma A, Kadhiravan T, et al. Rifamycins (rifampicin, rifabutin and rifapentine) compared to isoniazid for preventing tuberculosis in HIV-negative people at risk of active TB. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(7):CD007545.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 27-year-old daycare worker was tested for tuberculosis (TB) as part of a recent work physical. She presents to your office for follow-up for her positive purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test. You confirm the result with a quantiferon gold test and ensure she does not have active TB. What medication should you prescribe to treat her latent TB infection (LTBI)?

In 2017, there were 9093 cases of new active TB in the United States.2 It’s estimated that one-fourth of the world’s population has latent TB.3 Identifying and treating latent TB infection is vital to achieving TB’s elimination.4,5

Primary care clinicians are at the forefront of screening high-risk populations for TB. Once identified, treating LTBI can be challenging for providers and patients. Treatment guidelines recommend 4 to 9 months of daily isoniazid.5-8 Shorter treatment regimens were recommended previously; they tended to be rigorous, to involve multiple drugs, and to require high adherence rates. As such, they included directly observed therapy, which prevented widespread adoption.

Consequently, the mainstay for treating LTBI has been 9 months of daily isoniazid. However, isoniazid use is limited by hepatoxicity and by suboptimal treatment completion rates. A 2018 retrospective analysis of patients treated for LTBI reported a completion rate of only 49% for 9 months of isoniazid.9 Additionally, a Cochrane review last updated in 2013 suggests that shorter courses of rifampin are similar in efficacy to isoniazid (although with a wide confidence interval [CI]), and likely have higher adherence rates.10

STUDY SUMMARY

Rifampin is as effective as isoniazid with fewer adverse effects

The study by Menzies et al1 was a multisite, 9-country, open-label, randomized controlled trial (RCT) that compared 4 months of daily rifampin to 9 months of daily isoniazid for the treatment of LTBI in adults. Participants were eligible if they had a positive tuberculin skin test or interferon-gamma-release assay, were ≥ 18 years of age, had an increased risk for reactivation of active TB, and if their health care provider had recommended treatment with isoniazid. Exclusion criteria included current pregnancy or plans to become pregnant, exposure to a patient with TB whose isolates were resistant to either trial drug, an allergy to either of the trial drugs, use of a medication with serious potential interactions with the trial drugs, or current active TB.

Method, outcomes, patient characteristics. Patients received either isoniazid 5 mg/kg body weight (maximum dose 300 mg) daily for 9 months or rifampin 10 mg/kg (maximum dose 600 mg) daily for 4 months and were followed for 28 months. Patients in the isoniazid group also received pyridoxine (vitamin B6) if they were at risk for neuropathy. The primary outcome was the rate of active TB. Secondary outcomes included adverse events, medication regimen completion rate, and drug resistance, among others.

A total of 2989 patients were treated with isoniazid; 3023 patients were treated with rifampin. The mean age of the participants was 38.4 years, 41% of the population was male, and 71% of the groups had confirmed active TB in close contacts.

Continue to: Results

Results. Overall, rates of active TB were low with 9 cases in the isoniazid group and 8 in the rifampin group. In the intention-to-treat analysis, the rate difference for confirmed active TB was < 0.01 cases per 100 person-years (95% CI; −0.14 to 0.16). This met the prespecified noninferiority endpoint, but did not show superiority. A total of 79% of patients treated with rifampin vs 63% treated with isoniazid completed their respective medication courses (difference of 15.1 percentage points; 95% CI, 12.7-17.4; P < .001). Compared with patients in the isoniazid group, those taking rifampin had fewer adverse events, leading to discontinuation (5.6% vs 2.8%).

WHAT’S NEW?

First high-quality study to show that less is more

This is the first large, high-quality study to show that a shorter (4 month) rifampin-based regimen is not inferior to a longer (9 months) isoniazid-based regimen for the treatment of LTBI, and that rifampin is associated with improved adherence and fewer adverse events.

CAVEATS

Low rate of active TB infection and potential bias