User login

Large percentage of psychiatrists sued for malpractice at least once

Forty-one percent of U.S. psychiatrists have been sued for malpractice at least once, findings from the newly released Medscape Psychiatrist Malpractice Report 2019 show.

The top reason for the legal action was wrongful death (31%), followed by poor outcome/disease progression (23%), failure to treat/delayed treatment (11%), errors in medication administration (10%), and complications from treatment/surgery (8%).

Only 7% of psychiatrists said failure to treat/delayed treatment was the reason for the lawsuit, whereas this was the top reason for physicians overall (33%) in the report.

Medscape surveyed 4,360 physician members in more than 25 specialties about whether they have been sued for malpractice, reasons for a lawsuit, what happened, and how the experience affected the way they practice medicine and interact with patients.

Among psychiatrists named in a lawsuit, 44% said they were very surprised to be the subject of litigation. A similar percentage reported they were somewhat surprised (41%), while 15% were not at all surprised.

The vast majority of psychiatrists (87%) believed the lawsuit was not warranted, while 11% were unsure. Only a small percentage (2%) believed that legal action was justified, the lowest percentage of all physicians (6%).

Among psychiatrists who were sued, 42% were able to identify the incident that sparked the lawsuit. A slightly higher percentage (47%) said there was no specific incident that spurred legal action; 11% couldn’t recall.

Psychological factors

“There’s a whole host of what you could call psychological factors that can contribute to the filing of a claim,” David S. Szabo, a malpractice defense attorney with Locke Lord LLP, Boston, said in an interview.

“These can occur when a patient perceives a breakdown in the doctor-patient relationship or is pretty certain that there’s been a mistake and they feel like they’ve been shut out of productive conversation with their health care provider or providers,” said Mr. Szabo.

Legal action eats up time. A total of 43% of psychiatrists reported spending more than 40 hours on their defense, which involved gathering records, meeting with attorneys, and preparing for depositions.

Forty-six percent reported that the entire process took 1-2 years to resolve, but nearly a quarter (23%) said the process dragged on for 3-5 years.

One-third of psychiatrists who were named in a malpractice lawsuit said the case was settled out of court. Of the cases that went to trial, 12% of psychiatrists reported that the verdict was in their favor; 3% reported that the outcome of the case was in the plaintiff’s favor.

Asked why they think most malpractice lawsuits occurred, 61% of psychiatrists said that patients don’t understand medical risks and blame the doctor for bad outcomes even if the doctor does everything right.

A similar percentage of psychiatrists recognized that if a true medical error has occurred, patients wanted to seek restitution and/or assign blame. Only 29% of psychiatrists felt that constant advertising by lawyers to get new clients was the reason for most malpractice cases.

The overwhelming majority of psychiatrists (93%) who responded to the survey carry malpractice insurance, about the same as physicians overall (94%).

Among those with malpractice coverage who either settled or went to trial, about half were either encouraged by their insurer to settle the case or were required by their insurer to do so.

“Generally, if a physician senses that he or she is heading toward a difference of opinion with the insurer about settlement, they probably ought to invest a little time in having personal counsel look at the case,” Mr. Szabo said.

Practice changing?

Facing a lawsuit can be devastating for any physician, but nearly half (48%) of psychiatrists surveyed said they made no changes after the case was resolved.

Just over a quarter (27%) of psychiatrists said the legal action prompted a change in their approach to patients. In addition, 8% said they left their practice setting, and 3% said they bought more malpractice insurance.

Among psychiatrist cases that resulted in a settlement or a verdict in the plaintiff’s favor, nearly half (48%) of monetary awards maxed out at $100,000, while 31% maxed out at $500,000, and 8% at $1 million.

More than half of psychiatrists (55%) named in a lawsuit believed the outcome of the case was fair; 45% felt it was unfair.

Psychiatrists reported that, in retrospect, they would have done several things differently. These included maintaining better documentation of their patient’s chart (20%) and not taking on the patient in the first place (15%), followed by spending more time with the patient and his/her family (11%), getting a second opinion from a colleague (9%), and reviewing the history/chart more carefully (7%).

About three-quarters of psychiatrists felt that saying sorry or offering an apology to the patient would not have prevented the lawsuit. This is a lower percentage than was indicated by all physicians (82%) who have been sued.

Psychiatrists believe the best ways to discourage lawsuits is through better patient communication and rapport (59%) and having a medical panel screen cases for merit (50%).

About half of psychiatrists (51%) and more than half (56%) of all physicians believe that medical organizations or state societies are not doing enough to discourage malpractice cases.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Forty-one percent of U.S. psychiatrists have been sued for malpractice at least once, findings from the newly released Medscape Psychiatrist Malpractice Report 2019 show.

The top reason for the legal action was wrongful death (31%), followed by poor outcome/disease progression (23%), failure to treat/delayed treatment (11%), errors in medication administration (10%), and complications from treatment/surgery (8%).

Only 7% of psychiatrists said failure to treat/delayed treatment was the reason for the lawsuit, whereas this was the top reason for physicians overall (33%) in the report.

Medscape surveyed 4,360 physician members in more than 25 specialties about whether they have been sued for malpractice, reasons for a lawsuit, what happened, and how the experience affected the way they practice medicine and interact with patients.

Among psychiatrists named in a lawsuit, 44% said they were very surprised to be the subject of litigation. A similar percentage reported they were somewhat surprised (41%), while 15% were not at all surprised.

The vast majority of psychiatrists (87%) believed the lawsuit was not warranted, while 11% were unsure. Only a small percentage (2%) believed that legal action was justified, the lowest percentage of all physicians (6%).

Among psychiatrists who were sued, 42% were able to identify the incident that sparked the lawsuit. A slightly higher percentage (47%) said there was no specific incident that spurred legal action; 11% couldn’t recall.

Psychological factors

“There’s a whole host of what you could call psychological factors that can contribute to the filing of a claim,” David S. Szabo, a malpractice defense attorney with Locke Lord LLP, Boston, said in an interview.

“These can occur when a patient perceives a breakdown in the doctor-patient relationship or is pretty certain that there’s been a mistake and they feel like they’ve been shut out of productive conversation with their health care provider or providers,” said Mr. Szabo.

Legal action eats up time. A total of 43% of psychiatrists reported spending more than 40 hours on their defense, which involved gathering records, meeting with attorneys, and preparing for depositions.

Forty-six percent reported that the entire process took 1-2 years to resolve, but nearly a quarter (23%) said the process dragged on for 3-5 years.

One-third of psychiatrists who were named in a malpractice lawsuit said the case was settled out of court. Of the cases that went to trial, 12% of psychiatrists reported that the verdict was in their favor; 3% reported that the outcome of the case was in the plaintiff’s favor.

Asked why they think most malpractice lawsuits occurred, 61% of psychiatrists said that patients don’t understand medical risks and blame the doctor for bad outcomes even if the doctor does everything right.

A similar percentage of psychiatrists recognized that if a true medical error has occurred, patients wanted to seek restitution and/or assign blame. Only 29% of psychiatrists felt that constant advertising by lawyers to get new clients was the reason for most malpractice cases.

The overwhelming majority of psychiatrists (93%) who responded to the survey carry malpractice insurance, about the same as physicians overall (94%).

Among those with malpractice coverage who either settled or went to trial, about half were either encouraged by their insurer to settle the case or were required by their insurer to do so.

“Generally, if a physician senses that he or she is heading toward a difference of opinion with the insurer about settlement, they probably ought to invest a little time in having personal counsel look at the case,” Mr. Szabo said.

Practice changing?

Facing a lawsuit can be devastating for any physician, but nearly half (48%) of psychiatrists surveyed said they made no changes after the case was resolved.

Just over a quarter (27%) of psychiatrists said the legal action prompted a change in their approach to patients. In addition, 8% said they left their practice setting, and 3% said they bought more malpractice insurance.

Among psychiatrist cases that resulted in a settlement or a verdict in the plaintiff’s favor, nearly half (48%) of monetary awards maxed out at $100,000, while 31% maxed out at $500,000, and 8% at $1 million.

More than half of psychiatrists (55%) named in a lawsuit believed the outcome of the case was fair; 45% felt it was unfair.

Psychiatrists reported that, in retrospect, they would have done several things differently. These included maintaining better documentation of their patient’s chart (20%) and not taking on the patient in the first place (15%), followed by spending more time with the patient and his/her family (11%), getting a second opinion from a colleague (9%), and reviewing the history/chart more carefully (7%).

About three-quarters of psychiatrists felt that saying sorry or offering an apology to the patient would not have prevented the lawsuit. This is a lower percentage than was indicated by all physicians (82%) who have been sued.

Psychiatrists believe the best ways to discourage lawsuits is through better patient communication and rapport (59%) and having a medical panel screen cases for merit (50%).

About half of psychiatrists (51%) and more than half (56%) of all physicians believe that medical organizations or state societies are not doing enough to discourage malpractice cases.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Forty-one percent of U.S. psychiatrists have been sued for malpractice at least once, findings from the newly released Medscape Psychiatrist Malpractice Report 2019 show.

The top reason for the legal action was wrongful death (31%), followed by poor outcome/disease progression (23%), failure to treat/delayed treatment (11%), errors in medication administration (10%), and complications from treatment/surgery (8%).

Only 7% of psychiatrists said failure to treat/delayed treatment was the reason for the lawsuit, whereas this was the top reason for physicians overall (33%) in the report.

Medscape surveyed 4,360 physician members in more than 25 specialties about whether they have been sued for malpractice, reasons for a lawsuit, what happened, and how the experience affected the way they practice medicine and interact with patients.

Among psychiatrists named in a lawsuit, 44% said they were very surprised to be the subject of litigation. A similar percentage reported they were somewhat surprised (41%), while 15% were not at all surprised.

The vast majority of psychiatrists (87%) believed the lawsuit was not warranted, while 11% were unsure. Only a small percentage (2%) believed that legal action was justified, the lowest percentage of all physicians (6%).

Among psychiatrists who were sued, 42% were able to identify the incident that sparked the lawsuit. A slightly higher percentage (47%) said there was no specific incident that spurred legal action; 11% couldn’t recall.

Psychological factors

“There’s a whole host of what you could call psychological factors that can contribute to the filing of a claim,” David S. Szabo, a malpractice defense attorney with Locke Lord LLP, Boston, said in an interview.

“These can occur when a patient perceives a breakdown in the doctor-patient relationship or is pretty certain that there’s been a mistake and they feel like they’ve been shut out of productive conversation with their health care provider or providers,” said Mr. Szabo.

Legal action eats up time. A total of 43% of psychiatrists reported spending more than 40 hours on their defense, which involved gathering records, meeting with attorneys, and preparing for depositions.

Forty-six percent reported that the entire process took 1-2 years to resolve, but nearly a quarter (23%) said the process dragged on for 3-5 years.

One-third of psychiatrists who were named in a malpractice lawsuit said the case was settled out of court. Of the cases that went to trial, 12% of psychiatrists reported that the verdict was in their favor; 3% reported that the outcome of the case was in the plaintiff’s favor.

Asked why they think most malpractice lawsuits occurred, 61% of psychiatrists said that patients don’t understand medical risks and blame the doctor for bad outcomes even if the doctor does everything right.

A similar percentage of psychiatrists recognized that if a true medical error has occurred, patients wanted to seek restitution and/or assign blame. Only 29% of psychiatrists felt that constant advertising by lawyers to get new clients was the reason for most malpractice cases.

The overwhelming majority of psychiatrists (93%) who responded to the survey carry malpractice insurance, about the same as physicians overall (94%).

Among those with malpractice coverage who either settled or went to trial, about half were either encouraged by their insurer to settle the case or were required by their insurer to do so.

“Generally, if a physician senses that he or she is heading toward a difference of opinion with the insurer about settlement, they probably ought to invest a little time in having personal counsel look at the case,” Mr. Szabo said.

Practice changing?

Facing a lawsuit can be devastating for any physician, but nearly half (48%) of psychiatrists surveyed said they made no changes after the case was resolved.

Just over a quarter (27%) of psychiatrists said the legal action prompted a change in their approach to patients. In addition, 8% said they left their practice setting, and 3% said they bought more malpractice insurance.

Among psychiatrist cases that resulted in a settlement or a verdict in the plaintiff’s favor, nearly half (48%) of monetary awards maxed out at $100,000, while 31% maxed out at $500,000, and 8% at $1 million.

More than half of psychiatrists (55%) named in a lawsuit believed the outcome of the case was fair; 45% felt it was unfair.

Psychiatrists reported that, in retrospect, they would have done several things differently. These included maintaining better documentation of their patient’s chart (20%) and not taking on the patient in the first place (15%), followed by spending more time with the patient and his/her family (11%), getting a second opinion from a colleague (9%), and reviewing the history/chart more carefully (7%).

About three-quarters of psychiatrists felt that saying sorry or offering an apology to the patient would not have prevented the lawsuit. This is a lower percentage than was indicated by all physicians (82%) who have been sued.

Psychiatrists believe the best ways to discourage lawsuits is through better patient communication and rapport (59%) and having a medical panel screen cases for merit (50%).

About half of psychiatrists (51%) and more than half (56%) of all physicians believe that medical organizations or state societies are not doing enough to discourage malpractice cases.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

HHS: Coronavirus risk low in U.S., vaccine development underway

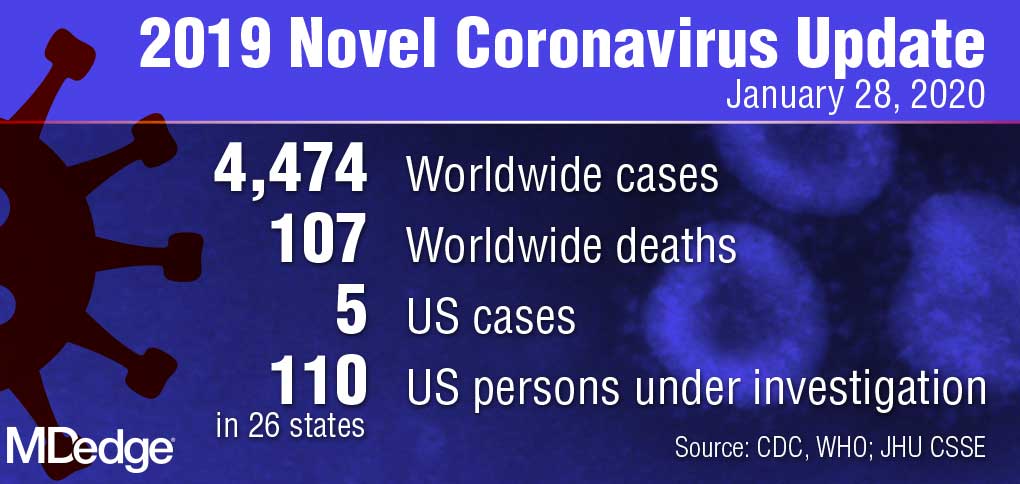

U.S. public health officials attempted to stymie concerns about the coronavirus during a press conference on Tuesday,

“Right now, there is no spread of this virus in our communities here at home,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention director Robert Redfield, MD, said during the Jan. 28 press conference. “This is why our current assessment is that the immediate health risk of this new virus to the general public is low in our nation. The coming days and weeks are likely to bring more confirmed cases here and around the world, including the possibility of some person-to-person spreading, but our goal of the ongoing U.S. public health response is to contain this outbreak and prevent sustained spread of the virus in our country.”

During the press conference, Department Health & Human Services Secretary Alex M. Azar II, reiterated there have been only five confirmed U.S. cases of the coronavirus thus far and all were associated with travel to Wuhan, China, where the virus first appeared. The number of confirmed cases in China, meanwhile, has risen to more than 4,500 with about 100 associated deaths.

U.S. health providers should be on the lookout for any patient who has traveled to China recently, particularly to Hubei province, and they should pay close attention to any relevant symptoms, Secretary Azar said during the press conference.

He defended the decision not to declare a public health emergency at this time, stressing that such a move is based on standards and requirements not yet met by the coronavirus.

“It’s important to remember where we are right now; we have five cases in the United States, each of those individuals with direct contact to Wuhan and no person-to-person transmission in the United States,” Secretary Azar said. “I won’t hesitate at all to invoke any authorities that I need to ensure that we’re taking all the steps to protect the American people, but I’ll do it when it’s appropriate under the standards that we have and the authorities that I need.”

In the meantime, a number of efforts are underway by U.S. agencies to assess the nation’s emergency preparedness stockpile, to assist American families in China with evacuation, and to pursue research into diagnostics and a potential vaccine for the virus, Secretary Azar said.

With regard to countermeasures, the CDC has rapidly developed a diagnostic based on the published sequence of the virus, said Anthony Fauci, MD, director for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). The National Institutes of Health and the CDC are now working on the development of next-generation diagnostics to better identify the virus in the United States and throughout the world, Dr. Fauci said during the press conference.

Currently, there are no proven therapeutics for the coronavirus infection, Dr. Fauci said. Based on experiences with SARS and MERS, however, researchers are studying certain antiviral drugs that could potentially treat the virus, he said. This includes the antiviral drug remdesivir, which was developed for the treatment of the Ebola virus, and lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra), a combination therapy commonly used to treat HIV. In addition, monoclonal antibodies developed during the SARS outbreak are also being studied.

“Given the somewhat close homology between SARS and the new novel coronavirus, there could be some cross reactivity there that could be utilized,” he said.

Most importantly, he said, vaccine development is underway. Since China isolated the virus and published its sequence, U.S. researchers have already analyzed the components and determined an immunogen to be used in a vaccine, Dr. Fauci said. He anticipates moving to a Phase 1 trial within the next 3 months. The trial would then move to Phase 2 after another few more months for safety data.

“What we do from that point will be determined by what has happened with the outbreak over those months,” he said. “We are proceeding as if we will have to deploy a vaccine. In other words, we’re looking at the worst scenario that this becomes a bigger outbreak.”

Federal health officials, however, stressed that more data about infected patients in China is needed for research. HHS has repeatedly offered to send a CDC team to China to help with public health efforts, research, and response, but China has so far declined the offer, Secretary Azar added.

In addition, the CDC has updated its travel advisory in response to the illness. The latest travel guidance recommends that travelers avoid all nonessential travel to all parts of China.

U.S. public health officials attempted to stymie concerns about the coronavirus during a press conference on Tuesday,

“Right now, there is no spread of this virus in our communities here at home,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention director Robert Redfield, MD, said during the Jan. 28 press conference. “This is why our current assessment is that the immediate health risk of this new virus to the general public is low in our nation. The coming days and weeks are likely to bring more confirmed cases here and around the world, including the possibility of some person-to-person spreading, but our goal of the ongoing U.S. public health response is to contain this outbreak and prevent sustained spread of the virus in our country.”

During the press conference, Department Health & Human Services Secretary Alex M. Azar II, reiterated there have been only five confirmed U.S. cases of the coronavirus thus far and all were associated with travel to Wuhan, China, where the virus first appeared. The number of confirmed cases in China, meanwhile, has risen to more than 4,500 with about 100 associated deaths.

U.S. health providers should be on the lookout for any patient who has traveled to China recently, particularly to Hubei province, and they should pay close attention to any relevant symptoms, Secretary Azar said during the press conference.

He defended the decision not to declare a public health emergency at this time, stressing that such a move is based on standards and requirements not yet met by the coronavirus.

“It’s important to remember where we are right now; we have five cases in the United States, each of those individuals with direct contact to Wuhan and no person-to-person transmission in the United States,” Secretary Azar said. “I won’t hesitate at all to invoke any authorities that I need to ensure that we’re taking all the steps to protect the American people, but I’ll do it when it’s appropriate under the standards that we have and the authorities that I need.”

In the meantime, a number of efforts are underway by U.S. agencies to assess the nation’s emergency preparedness stockpile, to assist American families in China with evacuation, and to pursue research into diagnostics and a potential vaccine for the virus, Secretary Azar said.

With regard to countermeasures, the CDC has rapidly developed a diagnostic based on the published sequence of the virus, said Anthony Fauci, MD, director for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). The National Institutes of Health and the CDC are now working on the development of next-generation diagnostics to better identify the virus in the United States and throughout the world, Dr. Fauci said during the press conference.

Currently, there are no proven therapeutics for the coronavirus infection, Dr. Fauci said. Based on experiences with SARS and MERS, however, researchers are studying certain antiviral drugs that could potentially treat the virus, he said. This includes the antiviral drug remdesivir, which was developed for the treatment of the Ebola virus, and lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra), a combination therapy commonly used to treat HIV. In addition, monoclonal antibodies developed during the SARS outbreak are also being studied.

“Given the somewhat close homology between SARS and the new novel coronavirus, there could be some cross reactivity there that could be utilized,” he said.

Most importantly, he said, vaccine development is underway. Since China isolated the virus and published its sequence, U.S. researchers have already analyzed the components and determined an immunogen to be used in a vaccine, Dr. Fauci said. He anticipates moving to a Phase 1 trial within the next 3 months. The trial would then move to Phase 2 after another few more months for safety data.

“What we do from that point will be determined by what has happened with the outbreak over those months,” he said. “We are proceeding as if we will have to deploy a vaccine. In other words, we’re looking at the worst scenario that this becomes a bigger outbreak.”

Federal health officials, however, stressed that more data about infected patients in China is needed for research. HHS has repeatedly offered to send a CDC team to China to help with public health efforts, research, and response, but China has so far declined the offer, Secretary Azar added.

In addition, the CDC has updated its travel advisory in response to the illness. The latest travel guidance recommends that travelers avoid all nonessential travel to all parts of China.

U.S. public health officials attempted to stymie concerns about the coronavirus during a press conference on Tuesday,

“Right now, there is no spread of this virus in our communities here at home,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention director Robert Redfield, MD, said during the Jan. 28 press conference. “This is why our current assessment is that the immediate health risk of this new virus to the general public is low in our nation. The coming days and weeks are likely to bring more confirmed cases here and around the world, including the possibility of some person-to-person spreading, but our goal of the ongoing U.S. public health response is to contain this outbreak and prevent sustained spread of the virus in our country.”

During the press conference, Department Health & Human Services Secretary Alex M. Azar II, reiterated there have been only five confirmed U.S. cases of the coronavirus thus far and all were associated with travel to Wuhan, China, where the virus first appeared. The number of confirmed cases in China, meanwhile, has risen to more than 4,500 with about 100 associated deaths.

U.S. health providers should be on the lookout for any patient who has traveled to China recently, particularly to Hubei province, and they should pay close attention to any relevant symptoms, Secretary Azar said during the press conference.

He defended the decision not to declare a public health emergency at this time, stressing that such a move is based on standards and requirements not yet met by the coronavirus.

“It’s important to remember where we are right now; we have five cases in the United States, each of those individuals with direct contact to Wuhan and no person-to-person transmission in the United States,” Secretary Azar said. “I won’t hesitate at all to invoke any authorities that I need to ensure that we’re taking all the steps to protect the American people, but I’ll do it when it’s appropriate under the standards that we have and the authorities that I need.”

In the meantime, a number of efforts are underway by U.S. agencies to assess the nation’s emergency preparedness stockpile, to assist American families in China with evacuation, and to pursue research into diagnostics and a potential vaccine for the virus, Secretary Azar said.

With regard to countermeasures, the CDC has rapidly developed a diagnostic based on the published sequence of the virus, said Anthony Fauci, MD, director for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). The National Institutes of Health and the CDC are now working on the development of next-generation diagnostics to better identify the virus in the United States and throughout the world, Dr. Fauci said during the press conference.

Currently, there are no proven therapeutics for the coronavirus infection, Dr. Fauci said. Based on experiences with SARS and MERS, however, researchers are studying certain antiviral drugs that could potentially treat the virus, he said. This includes the antiviral drug remdesivir, which was developed for the treatment of the Ebola virus, and lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra), a combination therapy commonly used to treat HIV. In addition, monoclonal antibodies developed during the SARS outbreak are also being studied.

“Given the somewhat close homology between SARS and the new novel coronavirus, there could be some cross reactivity there that could be utilized,” he said.

Most importantly, he said, vaccine development is underway. Since China isolated the virus and published its sequence, U.S. researchers have already analyzed the components and determined an immunogen to be used in a vaccine, Dr. Fauci said. He anticipates moving to a Phase 1 trial within the next 3 months. The trial would then move to Phase 2 after another few more months for safety data.

“What we do from that point will be determined by what has happened with the outbreak over those months,” he said. “We are proceeding as if we will have to deploy a vaccine. In other words, we’re looking at the worst scenario that this becomes a bigger outbreak.”

Federal health officials, however, stressed that more data about infected patients in China is needed for research. HHS has repeatedly offered to send a CDC team to China to help with public health efforts, research, and response, but China has so far declined the offer, Secretary Azar added.

In addition, the CDC has updated its travel advisory in response to the illness. The latest travel guidance recommends that travelers avoid all nonessential travel to all parts of China.

How to help patients become successful diabetes self-managers

Through the years, I have had the privilege of educating clinicians about scientific advances in diabetes care. Prior to displaying the first slide of my presentation, I ask the audience, “How many of you have seen a ‘noncompliant’ patient with diabetes within the past month?” Without fail, 99% of the attendees will raise their hand and start laughing, as if to say, “Well, of course they’re noncompliant. They just don’t get it! How incompetent can these people be?”

Blaming patients for failing to achieve metabolic control is inappropriate and misguided. How many physicians would be able or willing to monitor their blood glucose levels 4 times a day? Based on the premeal glucose level, how many physicians know how much insulin to inject in order to keep the postprandial excursions below 180 mg/dL? How many would remember to take 8 other medications daily without missing a dose? And how many physicians exercise daily; have actually looked at their feet in the past month; and have gained no weight in the past year?

Diabetes self-management is time-consuming and difficult for many patients, especially those with health illiteracy, financial restraints, or social barriers. Any patient who presents to the doctor is, in fact, “compliant.” These individuals expect to receive the safest and most effective treatments for their diabetes while learning as much as possible about lifestyle and behavioral interventions.

I challenge each of you to ask your patients: “What concerns you the most about having diabetes?” Initially, patients will express guilt and remorse about having diabetes. They will hang their heads in shame, admit to not going to the gym as often as they could, and promise to eat smaller portions. They will then look you in the eye and say, “I am worried about losing my eye, my leg, and my kidney to this life-threatening disease. I’m scared I won’t be able to see my daughter walk down the aisle at her wedding or my son graduate from college.”

These patients are terrified because they are unfamiliar with the advances in clinical science that aid our ability to improve the lives of all patients with diabetes. After hearing patients’ concerns about dying prematurely or losing an extremity to diabetes, I assure them that, “Nothing is going to happen to you on my watch. You are safe with me, and I will always have your back.” This level of trust is vitally important to the patient as well as to the treating physician. We all want our patients to achieve treatment success, just as any teacher would want their students to excel and graduate to the next grade level. Diabetes cannot be cured, yet we, as physicians, are able to heal with reassurance and expert guidance.

So, how do we help our patients achieve better adherence to their chronic disease state interventions? Here are 9 techniques that I have learned in my years helping patients manage their diabetes (all of which are more broadly applicable to any chronic disease state):

- Explain the disease state you are comanaging with the patient to the best of your ability. The more the patient understands, the easier your job as the “drug police” becomes.

- Remind the patient that he/she is the captain of the disease management team. You, the physician, serve as the personal coach. You can help the patient win the game, but he/she is ultimately responsible for achieving successful metabolic targets.

- Explain the risks, benefits, and any expected adverse effects that are likely to occur. Do this prior to initiating any medication.

- Discuss when metabolic change might be expected after initiating a given medication. Patients who observe rapid improvement in their glucose levels will be encouraged to adhere to their prescribed treatment regimen.

- Make certain that any and all screening tests are performed prior to initiating a medication. For example, renal function should be assessed prior to beginning most diabetes medications.

- Use shared decision-making to negotiate acceptable metabolic targets with each patient. Discuss the urgency and importance of achieving these goals.

- Assess the A1C reduction from baseline at 4 weeks after therapy initiation, rather than at 3 months. About 50% of the total A1C is reflective of the preceding 4 weeks of treatment.1 Thus, if the baseline A1C drops from 8.2% to 7.8%, the patient is moving in the right direction. However, if the A1C increases from 8.2% to 8.5%, the patient is not taking the prescribed medications.

- Recommend that the patient use a continuous glucose monitor; this newer technology is now readily available for patients who are covered by private insurance or Medicare. These devices allow patients to observe their glucose levels every 5 minutes of every day without fingersticks and actually cost less than self-monitoring one’s blood glucose.

- Find a reason to praise the patient at each visit. Patients who receive a powerful compliment, such as “I am so very proud of your efforts at improving your diabetes control,” will do their absolute best to remain adherent to their prescribed medication regimen. The response might be different if a patient is told, “Once again, your blood sugars are too high. At this rate, you are probably going to die, just like your father did 20 years ago. Now come back in 6 months and show me what you’re really made of!”

With more than 30 million Americans living with diabetes and another 84 million with prediabetes, the burden of preventive and intensive care lies squarely with family physicians.2 Rather than complain about our patients’ lack of metabolic control, we should provide them with the knowledge, skills, tools, and encouragement that they need to become successful diabetes self-managers.

1. Berard LD, Siemens R, Woo V; Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Monitoring glycemic control. Can J Diabetes. 2018;42(suppl 1):S47-S325.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. New CDC report: More than 100 million Americans have diabetes or prediabetes. July 18, 2017. www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2017/p0718-diabetes-report.html. Accessed January 15, 2020.

Through the years, I have had the privilege of educating clinicians about scientific advances in diabetes care. Prior to displaying the first slide of my presentation, I ask the audience, “How many of you have seen a ‘noncompliant’ patient with diabetes within the past month?” Without fail, 99% of the attendees will raise their hand and start laughing, as if to say, “Well, of course they’re noncompliant. They just don’t get it! How incompetent can these people be?”

Blaming patients for failing to achieve metabolic control is inappropriate and misguided. How many physicians would be able or willing to monitor their blood glucose levels 4 times a day? Based on the premeal glucose level, how many physicians know how much insulin to inject in order to keep the postprandial excursions below 180 mg/dL? How many would remember to take 8 other medications daily without missing a dose? And how many physicians exercise daily; have actually looked at their feet in the past month; and have gained no weight in the past year?

Diabetes self-management is time-consuming and difficult for many patients, especially those with health illiteracy, financial restraints, or social barriers. Any patient who presents to the doctor is, in fact, “compliant.” These individuals expect to receive the safest and most effective treatments for their diabetes while learning as much as possible about lifestyle and behavioral interventions.

I challenge each of you to ask your patients: “What concerns you the most about having diabetes?” Initially, patients will express guilt and remorse about having diabetes. They will hang their heads in shame, admit to not going to the gym as often as they could, and promise to eat smaller portions. They will then look you in the eye and say, “I am worried about losing my eye, my leg, and my kidney to this life-threatening disease. I’m scared I won’t be able to see my daughter walk down the aisle at her wedding or my son graduate from college.”

These patients are terrified because they are unfamiliar with the advances in clinical science that aid our ability to improve the lives of all patients with diabetes. After hearing patients’ concerns about dying prematurely or losing an extremity to diabetes, I assure them that, “Nothing is going to happen to you on my watch. You are safe with me, and I will always have your back.” This level of trust is vitally important to the patient as well as to the treating physician. We all want our patients to achieve treatment success, just as any teacher would want their students to excel and graduate to the next grade level. Diabetes cannot be cured, yet we, as physicians, are able to heal with reassurance and expert guidance.

So, how do we help our patients achieve better adherence to their chronic disease state interventions? Here are 9 techniques that I have learned in my years helping patients manage their diabetes (all of which are more broadly applicable to any chronic disease state):

- Explain the disease state you are comanaging with the patient to the best of your ability. The more the patient understands, the easier your job as the “drug police” becomes.

- Remind the patient that he/she is the captain of the disease management team. You, the physician, serve as the personal coach. You can help the patient win the game, but he/she is ultimately responsible for achieving successful metabolic targets.

- Explain the risks, benefits, and any expected adverse effects that are likely to occur. Do this prior to initiating any medication.

- Discuss when metabolic change might be expected after initiating a given medication. Patients who observe rapid improvement in their glucose levels will be encouraged to adhere to their prescribed treatment regimen.

- Make certain that any and all screening tests are performed prior to initiating a medication. For example, renal function should be assessed prior to beginning most diabetes medications.

- Use shared decision-making to negotiate acceptable metabolic targets with each patient. Discuss the urgency and importance of achieving these goals.

- Assess the A1C reduction from baseline at 4 weeks after therapy initiation, rather than at 3 months. About 50% of the total A1C is reflective of the preceding 4 weeks of treatment.1 Thus, if the baseline A1C drops from 8.2% to 7.8%, the patient is moving in the right direction. However, if the A1C increases from 8.2% to 8.5%, the patient is not taking the prescribed medications.

- Recommend that the patient use a continuous glucose monitor; this newer technology is now readily available for patients who are covered by private insurance or Medicare. These devices allow patients to observe their glucose levels every 5 minutes of every day without fingersticks and actually cost less than self-monitoring one’s blood glucose.

- Find a reason to praise the patient at each visit. Patients who receive a powerful compliment, such as “I am so very proud of your efforts at improving your diabetes control,” will do their absolute best to remain adherent to their prescribed medication regimen. The response might be different if a patient is told, “Once again, your blood sugars are too high. At this rate, you are probably going to die, just like your father did 20 years ago. Now come back in 6 months and show me what you’re really made of!”

With more than 30 million Americans living with diabetes and another 84 million with prediabetes, the burden of preventive and intensive care lies squarely with family physicians.2 Rather than complain about our patients’ lack of metabolic control, we should provide them with the knowledge, skills, tools, and encouragement that they need to become successful diabetes self-managers.

Through the years, I have had the privilege of educating clinicians about scientific advances in diabetes care. Prior to displaying the first slide of my presentation, I ask the audience, “How many of you have seen a ‘noncompliant’ patient with diabetes within the past month?” Without fail, 99% of the attendees will raise their hand and start laughing, as if to say, “Well, of course they’re noncompliant. They just don’t get it! How incompetent can these people be?”

Blaming patients for failing to achieve metabolic control is inappropriate and misguided. How many physicians would be able or willing to monitor their blood glucose levels 4 times a day? Based on the premeal glucose level, how many physicians know how much insulin to inject in order to keep the postprandial excursions below 180 mg/dL? How many would remember to take 8 other medications daily without missing a dose? And how many physicians exercise daily; have actually looked at their feet in the past month; and have gained no weight in the past year?

Diabetes self-management is time-consuming and difficult for many patients, especially those with health illiteracy, financial restraints, or social barriers. Any patient who presents to the doctor is, in fact, “compliant.” These individuals expect to receive the safest and most effective treatments for their diabetes while learning as much as possible about lifestyle and behavioral interventions.

I challenge each of you to ask your patients: “What concerns you the most about having diabetes?” Initially, patients will express guilt and remorse about having diabetes. They will hang their heads in shame, admit to not going to the gym as often as they could, and promise to eat smaller portions. They will then look you in the eye and say, “I am worried about losing my eye, my leg, and my kidney to this life-threatening disease. I’m scared I won’t be able to see my daughter walk down the aisle at her wedding or my son graduate from college.”

These patients are terrified because they are unfamiliar with the advances in clinical science that aid our ability to improve the lives of all patients with diabetes. After hearing patients’ concerns about dying prematurely or losing an extremity to diabetes, I assure them that, “Nothing is going to happen to you on my watch. You are safe with me, and I will always have your back.” This level of trust is vitally important to the patient as well as to the treating physician. We all want our patients to achieve treatment success, just as any teacher would want their students to excel and graduate to the next grade level. Diabetes cannot be cured, yet we, as physicians, are able to heal with reassurance and expert guidance.

So, how do we help our patients achieve better adherence to their chronic disease state interventions? Here are 9 techniques that I have learned in my years helping patients manage their diabetes (all of which are more broadly applicable to any chronic disease state):

- Explain the disease state you are comanaging with the patient to the best of your ability. The more the patient understands, the easier your job as the “drug police” becomes.

- Remind the patient that he/she is the captain of the disease management team. You, the physician, serve as the personal coach. You can help the patient win the game, but he/she is ultimately responsible for achieving successful metabolic targets.

- Explain the risks, benefits, and any expected adverse effects that are likely to occur. Do this prior to initiating any medication.

- Discuss when metabolic change might be expected after initiating a given medication. Patients who observe rapid improvement in their glucose levels will be encouraged to adhere to their prescribed treatment regimen.

- Make certain that any and all screening tests are performed prior to initiating a medication. For example, renal function should be assessed prior to beginning most diabetes medications.

- Use shared decision-making to negotiate acceptable metabolic targets with each patient. Discuss the urgency and importance of achieving these goals.

- Assess the A1C reduction from baseline at 4 weeks after therapy initiation, rather than at 3 months. About 50% of the total A1C is reflective of the preceding 4 weeks of treatment.1 Thus, if the baseline A1C drops from 8.2% to 7.8%, the patient is moving in the right direction. However, if the A1C increases from 8.2% to 8.5%, the patient is not taking the prescribed medications.

- Recommend that the patient use a continuous glucose monitor; this newer technology is now readily available for patients who are covered by private insurance or Medicare. These devices allow patients to observe their glucose levels every 5 minutes of every day without fingersticks and actually cost less than self-monitoring one’s blood glucose.

- Find a reason to praise the patient at each visit. Patients who receive a powerful compliment, such as “I am so very proud of your efforts at improving your diabetes control,” will do their absolute best to remain adherent to their prescribed medication regimen. The response might be different if a patient is told, “Once again, your blood sugars are too high. At this rate, you are probably going to die, just like your father did 20 years ago. Now come back in 6 months and show me what you’re really made of!”

With more than 30 million Americans living with diabetes and another 84 million with prediabetes, the burden of preventive and intensive care lies squarely with family physicians.2 Rather than complain about our patients’ lack of metabolic control, we should provide them with the knowledge, skills, tools, and encouragement that they need to become successful diabetes self-managers.

1. Berard LD, Siemens R, Woo V; Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Monitoring glycemic control. Can J Diabetes. 2018;42(suppl 1):S47-S325.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. New CDC report: More than 100 million Americans have diabetes or prediabetes. July 18, 2017. www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2017/p0718-diabetes-report.html. Accessed January 15, 2020.

1. Berard LD, Siemens R, Woo V; Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Monitoring glycemic control. Can J Diabetes. 2018;42(suppl 1):S47-S325.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. New CDC report: More than 100 million Americans have diabetes or prediabetes. July 18, 2017. www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2017/p0718-diabetes-report.html. Accessed January 15, 2020.

Evidence-based tools for premenstrual disorders

CASE

A 30-year-old G2P2 woman presents for a well-woman visit and reports 6 months of premenstrual symptoms including irritability, depression, breast pain, and headaches. She is not taking any medications or hormonal contraceptives. She is sexually active and currently not interested in becoming pregnant. She asks what you can do for her symptoms, as they are affecting her life at home and at work.

Symptoms and definitions vary

Although more than 150 premenstrual symptoms have been reported, the most common psychological and behavioral ones are mood swings, depression, anxiety, irritability, crying, social withdrawal, forgetfulness, and problems concentrating.1-3 The most common physical symptoms are fatigue, abdominal bloating, weight gain, breast tenderness, acne, change in appetite or food cravings, edema, headache, and gastrointestinal upset. The etiology of these symptoms is usually multifactorial, with some combination of hormonal, neurotransmitter, lifestyle, environmental, and psychosocial factors playing a role.

Premenstrual disorder. In reviewing diagnostic criteria for the various premenstrual syndromes and disorders from different organizations (eg, the International Society for Premenstrual Disorders; the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition), there is agreement on the following criteria for premenstrual syndrome (PMS)4-6:

- The woman must be ovulating. (Women who no longer menstruate [eg, because of hysterectomy or endometrial ablation] can have premenstrual disorders as long as ovarian function remains intact.)

- The woman experiences a constellation of disabling physical and/or psychological symptoms that appears in the luteal phase of her menstrual cycle.

- The symptoms improve soon after the onset of menses.

- There is a symptom-free interval before ovulation.

- There is prospective documentation of symptoms for at least 2 consecutive cycles.

- The symptoms are sufficient in severity to affect activities of daily living and/or important relationships.

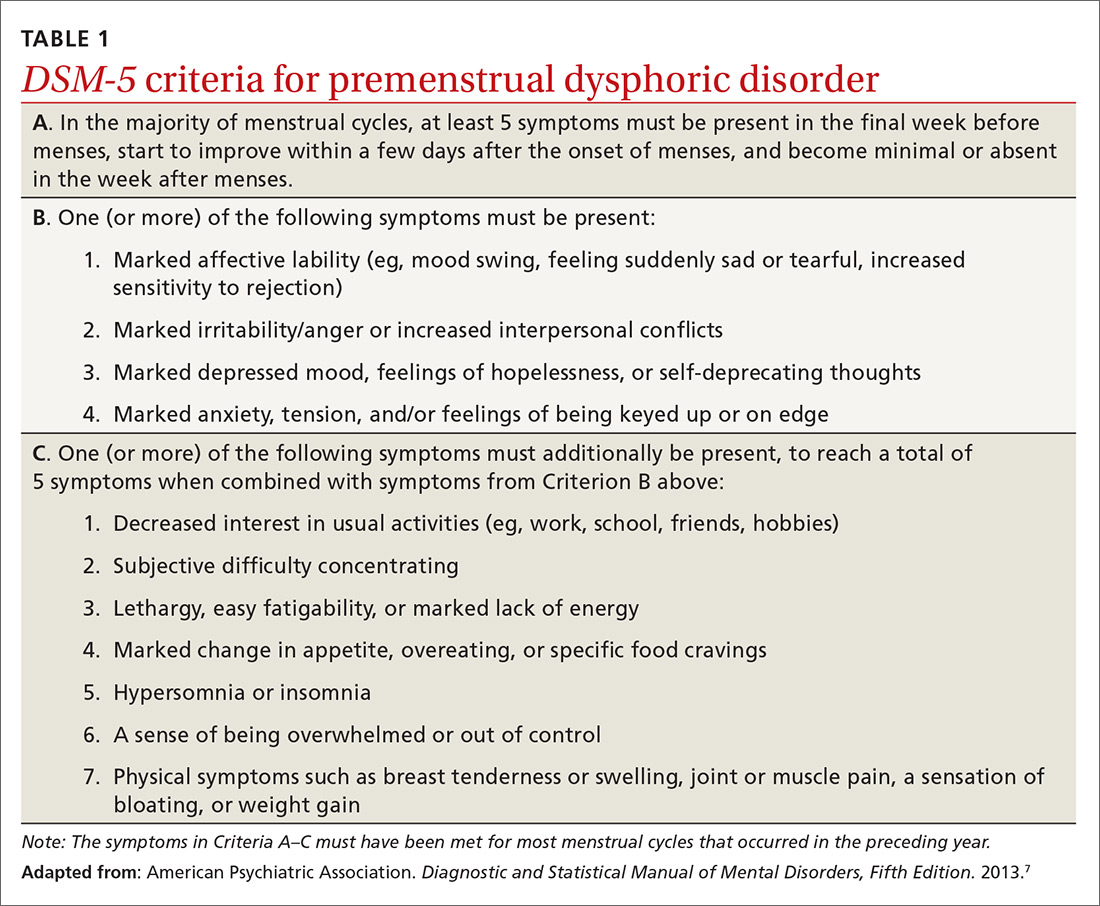

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder. PMDD is another common premenstrual disorder. It is distinguished by significant premenstrual psychological symptoms and requires the presence of marked affective lability, marked irritability or anger, markedly depressed mood, and/or marked anxiety (TABLE 1).7

Exacerbation of other ailments. Another premenstrual disorder is the premenstrual exacerbation of underlying chronic medical or psychological problems such as migraines, seizures, asthma, diabetes, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, anxiety, or depression.

Differences in interpretation lead to variations in prevalence

Differences in the interpretation of significant premenstrual symptoms have led to variations in estimated prevalence. For example, 80% to 95% of women report premenstrual symptoms, but only 30% to 40% meet criteria for PMS and only 3% to 8% meet criteria for PMDD.8 Many women who report premenstrual symptoms in a retrospective questionnaire do not meet criteria for PMS or PMDD based on prospective symptom charting. The Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP), a prospective tracking tool for premenstrual symptoms, is sensitive and specific for diagnosing PMS and PMDD if administered on the first day of menstruation.9

Ask about symptoms and use a tracking tool

When you see a woman for a well-woman visit or a gynecologic problem, inquire about physical/emotional symptoms and their severity during the week that precedes menstruation. If a patient reports few symptoms of a mild nature, then no further work-up is needed.

Continue to: If patients report significant...

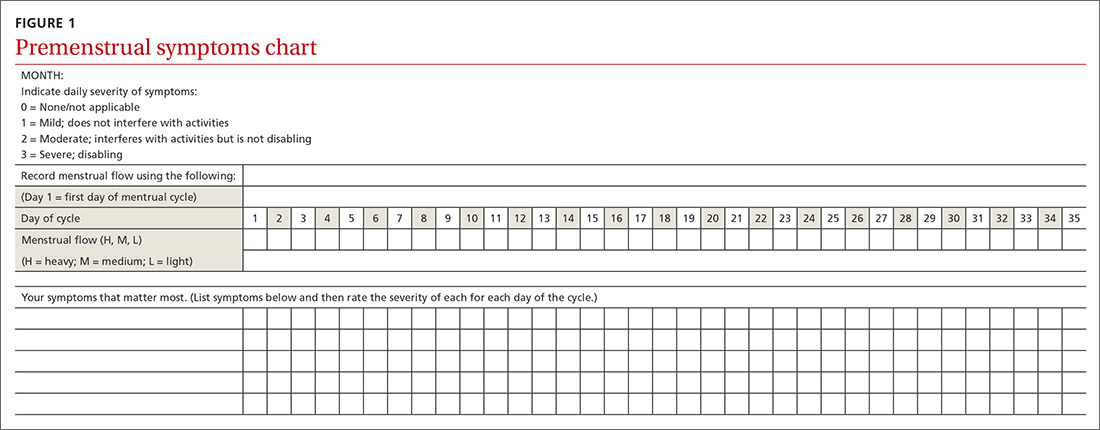

If patients report significant premenstrual symptoms, recommend the use of a tool to track the symptoms. Older tools such as the DRSP and the Premenstrual Symptoms Screening Tool (PSST), newer symptom diaries that can be used for both PMS and PMDD,and questionnaires that have been used in research situations can be time consuming and difficult for patients to complete.10-12 Instead, physicians can easily construct their own charting tool, as we did for patients to use when tracking their most bothersome symptoms (FIGURE 1). Tracking helps to confirm the diagnosis and helps you and the patient focus on treatment goals.

Keep in mind other diagnoses (eg, anemia, thyroid disorders, perimenopause, anxiety, depression, eating disorders, substance abuse) that can cause or exacerbate the psychological/physical symptoms the patient is reporting. If you suspect any of these other diagnoses, laboratory evaluation (eg, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone level or other hormonal testing, urine drug screen, etc) may be warranted to rule out other etiologies for the reported symptoms.

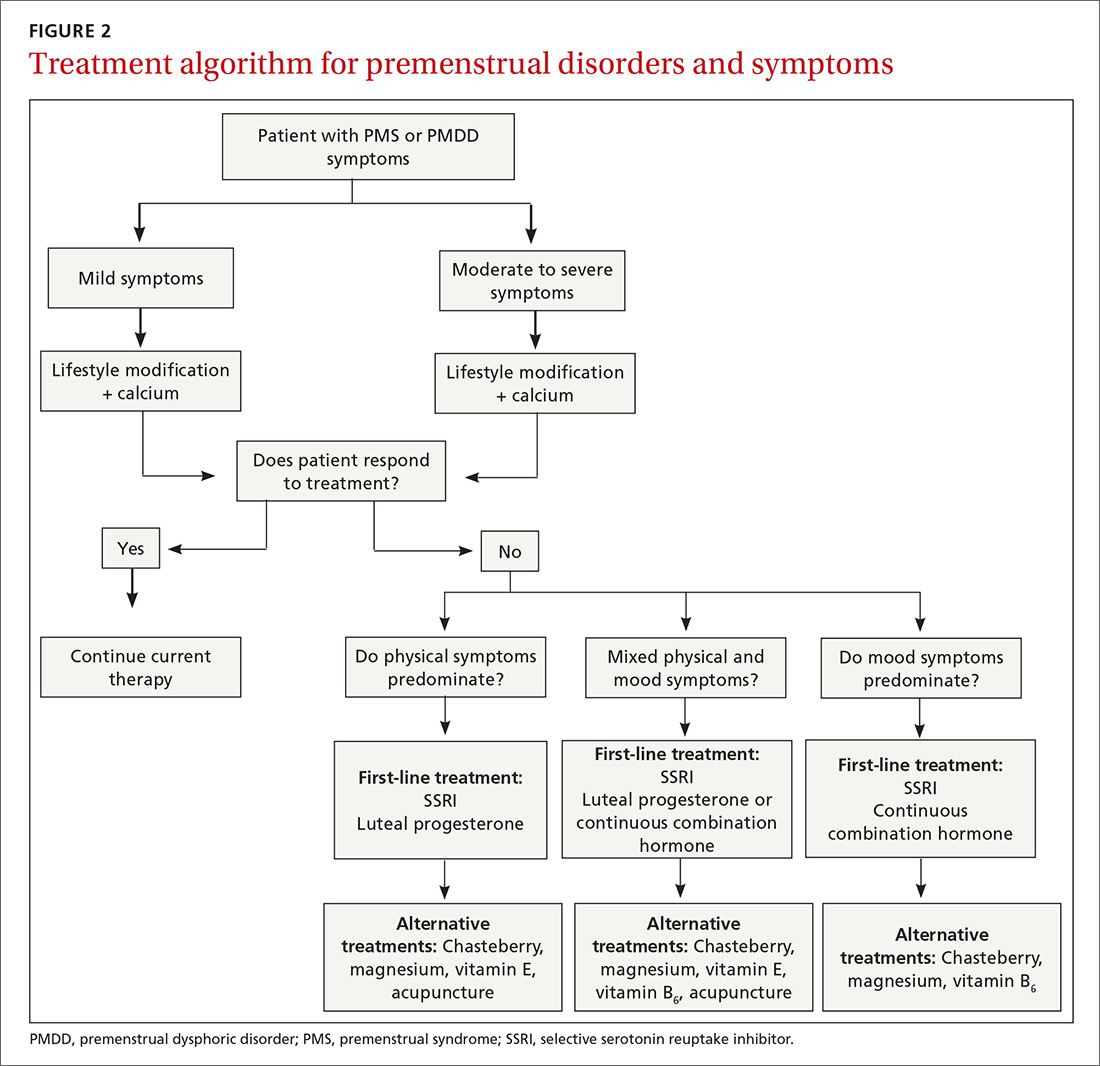

Develop a Tx plan that considers symptoms, family-planning needs

Focus treatment on the patient’s predominant symptoms whether they are physical, psychological, or mixed (FIGURE 2). The patient’s preferences regarding family planning are another important consideration. Women who are using a fertility awareness

Although the definitions for PMS and PMDD require at least 2 cycles of prospective documentation of symptoms, dietary and lifestyle changes can begin immediately. Regular follow-up to document improvement of symptoms is important; using the patient’s symptoms charting tool can help with this.

Focus on diet and lifestyle right away

Experts in the field of PMS/PMDD suggest that simple dietary changes may be a reasonable first step to help improve symptoms. Researchers have found that diets high in fiber, vegetables, and whole grains are inversely related to PMS.13 Older studies have suggested an increased prevalence and severity of PMS with increased caffeine intake; however, a newer study found no such association.14

Continue to: A case-control study nested...

A case-control study nested within the Nurses’ Health Study II cohort showed that a high intake of both dietary calcium and vitamin D prevented the development of PMS in women ages 27 to 44.15 B vitamins, such as thiamine and riboflavin, from food sources have been associated with a lower risk of PMS.16 A variety of older clinical studies showed benefit from aerobic exercise on PMS symptoms,17-19 but a newer cross-sectional study of young adult women found no association between physical activity and the prevalence of PMS.20 Acupuncture has demonstrated efficacy for the treatment of the physical symptoms of PMS and PMDD, but more rigorous studies are needed.21,22 Cognitive behavioral therapy has been studied as a treatment, but data to support this approach are limited so it cannot be recommended at this time.23

Make the most of supplements—especially calcium

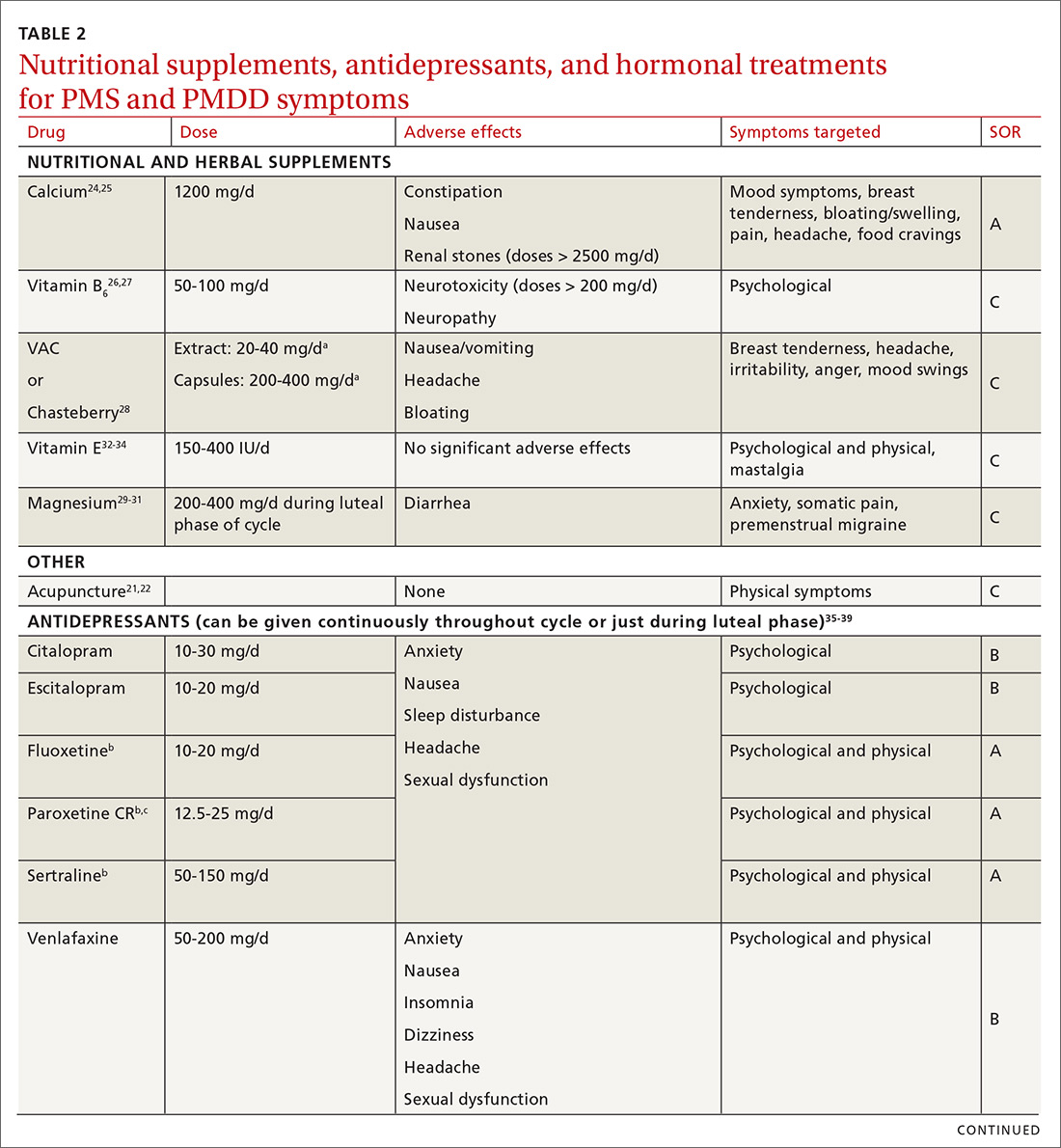

Calcium is the nutritional supplement with the most evidence to support its use to relieve symptoms of PMS and PMDD (TABLE 221,22,24-45). Research indicates that disturbances in calcium regulation and calcium deficiency may be responsible for various premenstrual symptoms. One study showed that, compared with placebo, women who took 1200 mg/d calcium carbonate for 3 menstrual cycles had a 48% decrease in both somatic and affective symptoms.24 Another trial demonstrated improvement in PMS symptoms of early tiredness, appetite changes, and depression with calcium therapy.25

Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) has potential benefit in treating PMS due to its ability to increase levels of serotonin, norepinephrine, histamine, dopamine, and taurine.26 An older systematic review showed benefit for symptoms associated with PMS, but the authors concluded that larger randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were needed before definitive recommendations could be made.27

Chasteberry. A number of studies have evaluated the effect of vitex agnus castus (VAC), commonly referred to as chasteberry, on PMS and PMDD symptoms. The exact mechanism of VAC is unknown, but in vitro studies show binding of VAC extracts to dopamine-2 receptors and opioid receptors, and an affinity for estrogen receptors.28

A recent meta-analysis concluded that VAC extracts are not superior to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or oral contraceptives (OCs) for PMS/PMDD.28 The authors suggested a possible benefit of VAC compared with placebo or other nutritional supplements; however, the studies supporting its use are limited by small sample size and potential bias.

Continue to: Magnesium

Magnesium. Many small studies have evaluated the role of other herbal and nutritional supplements for the treatment of PMS/PMDD. A systematic review of studies on the effect of magnesium supplementation on anxiety and stress showed that magnesium may have a potential role in the treatment of the premenstrual symptom of anxiety.29 Other studies have demonstrated a potential role in the treatment of premenstrual migraine.30,31

Vitamin E has demonstrated benefit in the treatment of cyclic mastalgia; however, evidence for using vitamin E for mood and depressive symptoms associated with PMS and PMDD is inconsistent.32-34 Other studies involving vitamin D, St. John’s wort, black cohosh, evening primrose oil, saffron, and ginkgo biloba either showed these agents to be nonefficacious in relieving PMS/PMDD symptoms or to require more data before they can be recommended for use.34,46

Patient doesn’t respond? Start an SSRI

Pharmacotherapy with antidepressants is typically reserved for those who do not respond to nonpharmacologic therapies and are experiencing more moderate to severe symptoms of PMS or PMDD. Reduced levels of serotonin and serotonergic activity in the brain may be linked to symptoms of PMS and PMDD.47 Studies have shown SSRIs to be effective in reducing many psychological symptoms (eg, depression, anxiety, lethargy, irritability) and some physical symptoms (eg, headache, breast tenderness, muscle or joint pain) associated with PMS and PMDD.

A Cochrane review of 31 RCTs compared various SSRIs to placebo. When taken either continuously or intermittently (administration during luteal phase), SSRIs were similarly effective in relieving symptoms when compared with placebo.35 Psychological symptoms are more likely to improve with both low and moderate doses of SSRIs, while physical symptoms may only improve with moderate or higher doses. A direct comparison of the various SSRIs for the treatment of PMS or PMDD is lacking; therefore, the selection of SSRI may be based on patient characteristics and preference.

The benefits of SSRIs are noted much earlier in the treatment of PMS/PMDD than they are observed in their use for depression or anxiety.36 This suggests that the mechanism by which SSRIs relieve PMS/PMDD symptoms is different than that for depression or anxiety. Intermittent dosing capitalizes upon the rapid effect seen with these medications and the cyclical nature of these disorders. In most studies, the benefit of intermittent dosing is similar to continuous dosing; however, one meta-analysis did note that continuous dosing had a larger effect.37

Continue to: The doses of SSRIs...

The doses of SSRIs used in most PMS/PMDD trials were lower than those typically used for the treatment of depression and anxiety. The withdrawal effect that can be seen with abrupt cessation of SSRIs has not been reported in the intermittent-dosing studies for PMS/PMDD.38 While this might imply a more tolerable safety profile, the most common adverse effects reported in trials were still as expected: sleep disturbances, headache, nausea, and sexual dysfunction. It is important to note that SSRIs should be used with caution during pregnancy, and paroxetine should be avoided in women considering pregnancy in the near future.

Other antidepressant classes have been studied to a lesser extent than SSRIs. Continuously dosed venlafaxine, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, demonstrated efficacy in PMS/PMDD treatment when compared with placebo within the first cycle of therapy.39 The response seen was comparable to that associated with SSRI treatments in other trials.

Buspirone, an anxiolytic with serotonin receptor activity that is different from that of the SSRIs, demonstrated efficacy in reducing the symptom of irritability.48 Buspirone may have a role to play in those presenting with irritability as a primary symptom or in those who are unable to tolerate the adverse effects of SSRIs. Tricyclic antidepressants, bupropion, and alprazolam have either limited data regarding efficacy or are associated with adverse effects that limit their use.38

Hormonal treatments may be worth considering

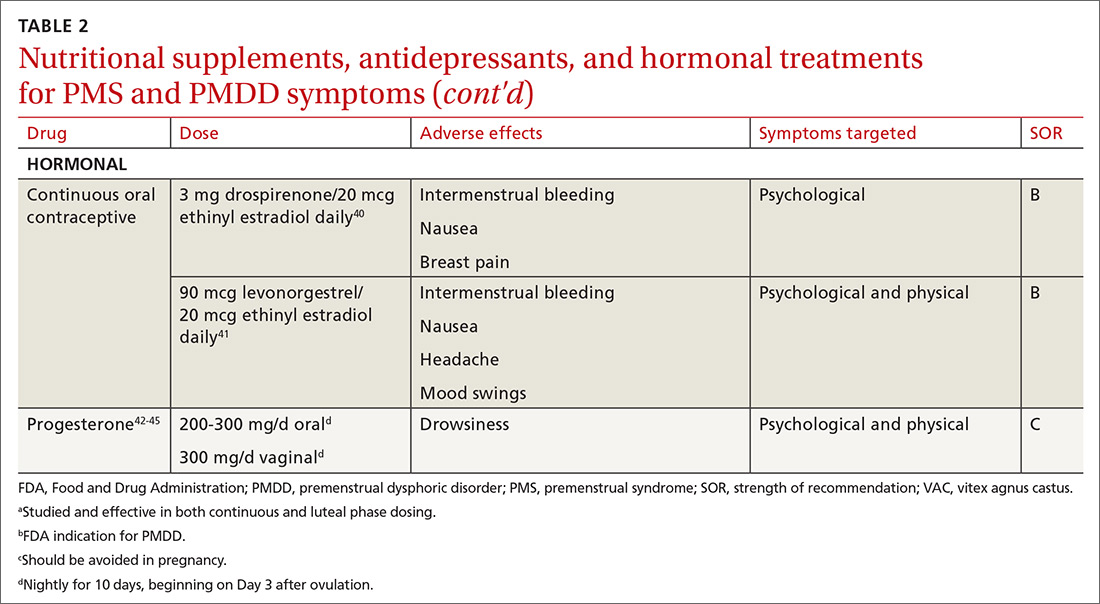

One commonly prescribed hormonal therapy for PMS and PMDD is continuous OCs. A 2012 Cochrane review of OCs containing drospirenone evaluated 5 trials and a total of 1920 women.40 Two placebo-controlled trials of women with severe premenstrual symptoms (PMDD) showed improvement after 3 months of taking daily drospirenone 3 mg with ethinyl estradiol 20 mcg, compared with placebo.

While experiencing greater benefit, these groups also experienced significantly more adverse effects including nausea, intermenstrual bleeding, and breast pain. The respective odds ratios for the 3 adverse effects were 3.15 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.90-5.22), 4.92 (95% CI, 3.03-7.96), and 2.67 (95% CI, 1.50-4.78). The review concluded that drospirenone 3 mg with ethinyl estradiol 20 mcg may help in the treatment of severe premenstrual symptoms (PMDD) but that it is unknown whether this treatment is appropriate for patients with less severe premenstrual symptoms.

Continue to: Another multicenter RCT

Another multicenter RCT evaluated women with PMDD who received levonorgestrel 90 mcg with ethinyl estradiol 20 mcg or placebo daily for 112 days.41 Symptoms were recorded utilizing the DRSP. Significantly more women taking the daily combination hormone (52%) than placebo (40%) had a positive response (≥ 50% improvement in the DRSP 7-day late luteal phase score and Clinical Global Impression of Severity score of ≥ 1 improvement, evaluated at the last “on-therapy” cycle [P = .025]). Twenty-three of 186 patients in the treatment arm dropped out because of adverse effects.

Noncontraceptive estrogen-containing preparations. Hormone therapy preparations containing lower doses of estrogen than seen in OC preparations have also been studied for PMS management. A 2017 Cochrane review of noncontraceptive estrogen-containing preparations found very low-quality evidence to support the effectiveness of continuous estrogen (transdermal patches or subcutaneous implants) plus progestogen.49

Progesterone. The cyclic use of progesterone in the luteal phase has been reviewed as a hormonal treatment for PMS. A 2012 Cochrane review of the efficacy of progesterone for PMS was inconclusive; however, route of administration, dose, and duration differed across studies.42

Another systematic review of 10 trials involving 531 women concluded that progesterone was no better than placebo in the treatment of PMS.43 However, it should be noted that each trial evaluated a different dose of progesterone, and all but 1 of the trials administered progesterone by using the calendar method to predict the beginning of the luteal phase. The only trial to use an objective confirmation of ovulation prior to beginning progesterone therapy did demonstrate significant improvement in premenstrual symptoms.

This 1985 study by Dennerstein et al44 prescribed progesterone for 10 days of each menstrual cycle starting 3 days after ovulation. In each cycle, ovulation was confirmed by determinations of urinary 24-hour pregnanediol and total estrogen concentrations. Progesterone was then prescribed during the objectively identified luteal phase, resulting in significant improvement in symptoms.

Continue to: Another study evaluated...

Another study evaluated the post-ovulatory progesterone profiles of 77 women with symptoms of PMS and found lower levels of progesterone and a sharper rate of decline in the women with PMS vs the control group.45 Subsequent progesterone treatment during the objectively identified luteal phase significantly improved PMS symptoms. These studies would seem to suggest that progesterone replacement when administered during an objectively identified luteal phase may offer some benefit in the treatment of PMS, but larger RCTs are needed to confirm this.

CASE

You provide the patient with diet and lifestyle education as well as a recommendation for calcium supplementation. The patient agrees to prospectively chart her most significant premenstrual symptoms. You review additional treatment options including SSRI medications and hormonal approaches. She is using a fertility awareness–based method of family planning that allows her to confidently identify her luteal phase. She agrees to take sertraline 50 mg/d during the luteal phase of her cycle. At her follow-up office visit 3 months later, she reports improvement in her premenstrual symptoms. Her charting of symptoms confirms this.

CORRESPONDENCE

Peter Danis, MD, Mercy Family Medicine St. Louis, 12680 Olive Boulevard, St. Louis, MO 63141; Peter.Danis@mercy.net.

1. Woods NF, Most A, Dery GK. Prevalence of perimenstrual symptoms. Am J Public Health. 1982;72:1257-1264.

2. Johnson SR, McChesney C, Bean JA. Epidemiology of premenstrual symptoms in a nonclinical sample. 1. Prevalence, natural history and help-seeking behavior. J Repro Med. 1988;33:340-346.

3. Campbell EM, Peterkin D, O’Grady K, et al. Premenstrual symptoms in general practice patients. Prevalence and treatment. J Reprod Med. 1997;42:637-646.

4. O’Brien PM, Bäckström T, Brown C, et al. Towards a consensus on diagnostic criteria, measurement, and trial design of the premenstrual disorders: the ISPMD Montreal consensus. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14:13-21.

5. Epperson CN, Steiner M, Hartlage SA, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: evidence for a new category for DSM-5. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:465-475.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for Women’s Health Care: A Resource Manual. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2014:607-613.

7. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

8. Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Heinemann K. Epidemiology of premenstrual symptoms and disorders. Menopause Int. 2012;18:48-51.

9. Borenstein JE, Dean BB, Yonkers KA, et al. Using the daily record of severity of problems as a screening instrument for premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:1068-1075.

10. Steiner M, Macdougall M, Brown E. The premenstrual symptoms screening tool (PSST) for clinicians. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2003;6:203-209.

11. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W. Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP): reliability and validity. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9:41-49.

12. Janda C, Kues JN, Andersson G, et al. A symptom diary to assess severe premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Women Health. 2017;57:837-854.

13. Farasati N, Siassi F, Koohdani F, et al. Western dietary pattern is related to premenstrual syndrome: a case-control study. Brit J Nutr. 2015;114:2016-2021.

14. Purdue-Smithe AC, Manson JE, Hankinson SE, et al. A prospective study of caffeine and coffee intake and premenstrual syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:499-507.

15. Bertone-Johnson ER, Hankinson SE, Bendich A, et al. Calcium and vitamin D intake and risk of incident premenstrual syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1246-1252.

16. Chocano-Bedoya PO, Manson JE, Hankinson SE, et al. Dietary B vitamin intake and incident premenstrual syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:1080-1086.

17. Prior JC, Vigna Y. Conditioning exercise and premenstrual symptoms. J Reprod Med. 1987;32:423-428.

18. Aganoff JA, Boyle GJ. Aerobic exercise, mood states, and menstrual cycle symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38:183-192.

19. El-Lithy A, El-Mazny A, Sabbour A, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on premenstrual symptoms, haematological and hormonal parameters in young women. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;35:389-392.

20. Kroll-Desrosiers AR, Ronnenberg AG, Zagarins SE, et al. Recreational physical activity and premenstrual syndrome in young adult women: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017;12:1-13.

21. Jang SH, Kim DI, Choi MS. Effects and treatment methods of acupuncture and herbal medicine for premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder: systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:11.

22. Kim SY, Park HJ, Lee H, et al. Acupuncture for premenstrual syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BJOG. 2011;118:899-915.

23. Lustyk MK, Gerrish WG, Shaver S, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12:85-96.

24. Thys-Jacob S, Starkey P, Bernstein D, et al. Calcium carbonate and the premenstrual syndrome: effects on premenstrual and menstrual syndromes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:444-452.

25. Ghanbari Z, Haghollahi F, Shariat M, et al. Effects of calcium supplement therapy in women with premenstrual syndrome. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;48:124-129.

26. Girman A, Lee R, Kligler B. An integrative medicine approach to premenstrual syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(5 suppl):s56-s65.

27. Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Jones PW, et al. Efficacy of vitamin B-6 in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: systematic review. BMJ. 1999;318:1375-1381.

28. Verkaik S, Kamperman AM, van Westrhenen R, et al. The treatment of premenstrual syndrome with preparations of vitex agnus castus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:150-166.

29. Boyle NB, Lawton C, Dye L. The effects of magnesium supplementation on subjective anxiety and stress—a systematic review. Nutrients. 2017;9:429-450.

30. Mauskop A, Altura BT, Altura BM. Serum ionized magnesium levels and serum ionized calcium/ionized magnesium ratios in women with menstrual migraine. Headache. 2002;42:242-248.

31. Facchinetti F, Sances C, Borella P, et al. Magnesium prophylaxis of menstrual migraine: effects on intracellular magnesium. Headache. 1991;31:298-301.

32. Parsay S, Olfati F, Nahidi S. Therapeutic effects of vitamin E on cyclic mastalgia. Breast J. 2009;15:510-514.

33. London RS, Murphy L, Kitlowski KE, et al. Efficacy of alpha-tocopherol in the treatment of the premenstrual syndrome. J Reprod Med. 1987;32:400-404.

34. Whelan AM, Jurgens TM, Naylor H. Herbs, vitamins, and minerals in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: a systematic review. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;16:e407-e429.

, , , . Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6): CD001396.

36. Dimmock P, Wyatt K, Jones P, et al. Efficacy of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in premenstrual syndrome: a systematic review. Lancet. 2000;356:1131-1136.

37. Shah NR, Jones JB, Aperi J, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1175-1182.

38. Freeman EW. Luteal phase administration of agents for the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. CNS Drugs. 2004;18:453-468.

39. Freeman EW, Rickels K, Yonkers KA, et al. Venlafaxine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:737-744.

40. Lopez LM, Kaptein AA, Helmerhorst FM. Oral contraceptives containing drospirenone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(2):CD006586.

41. Halbreich U, Freeman EW, Rapkin AJ, et al. Continuous oral levonorgestrel/ethinyl estradiol for treating premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Contraception. 2012;85:19-27.

, , , . Progesterone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD003415.

43. Wyatt K, Dimmock P, Jones P, et al. Efficacy of progesterone and progestogens in management of premenstrual syndrome: systematic review. BMJ. 2001;323: 776-780.

44. Dennerstein L, Spencer-Gardner C, Gotts G, et al. Progesterone and the premenstrual syndrome: a double-blind crossover trial. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;290:1617-1621.

45. NaProTECHNOLOGY. The Medical and Surgical Practice of NaProTECHNOLOGY. Premenstrual Syndrome: Evaluation and Treatment. Omaha, NE: Pope Paul VI Institute Press. 2004;29:345-368. https://www.naprotechnology.com/naprotext.htm. Accessed January 23, 2020.

46. Dante G, Facchinetti F. Herbal treatments for alleviating premenstrual symptoms: a systematic review. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;32:42-51.

47. Jarvis CI, Lynch AM, Morin AK. Management strategies for premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:967-978.

48. Landen M, Eriksson O, Sundblad C, et al. Compounds with affinity for serotonergic receptors in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria: a comparison of buspirone, nefazodone and placebo. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2001;155:292-298.

, , , . Non-contraceptive oestrogen-containing preparations for controlling symptoms of premenstrual syndrome . Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2017 ;( 3) :CD010503.

CASE

A 30-year-old G2P2 woman presents for a well-woman visit and reports 6 months of premenstrual symptoms including irritability, depression, breast pain, and headaches. She is not taking any medications or hormonal contraceptives. She is sexually active and currently not interested in becoming pregnant. She asks what you can do for her symptoms, as they are affecting her life at home and at work.

Symptoms and definitions vary

Although more than 150 premenstrual symptoms have been reported, the most common psychological and behavioral ones are mood swings, depression, anxiety, irritability, crying, social withdrawal, forgetfulness, and problems concentrating.1-3 The most common physical symptoms are fatigue, abdominal bloating, weight gain, breast tenderness, acne, change in appetite or food cravings, edema, headache, and gastrointestinal upset. The etiology of these symptoms is usually multifactorial, with some combination of hormonal, neurotransmitter, lifestyle, environmental, and psychosocial factors playing a role.

Premenstrual disorder. In reviewing diagnostic criteria for the various premenstrual syndromes and disorders from different organizations (eg, the International Society for Premenstrual Disorders; the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition), there is agreement on the following criteria for premenstrual syndrome (PMS)4-6:

- The woman must be ovulating. (Women who no longer menstruate [eg, because of hysterectomy or endometrial ablation] can have premenstrual disorders as long as ovarian function remains intact.)

- The woman experiences a constellation of disabling physical and/or psychological symptoms that appears in the luteal phase of her menstrual cycle.

- The symptoms improve soon after the onset of menses.

- There is a symptom-free interval before ovulation.

- There is prospective documentation of symptoms for at least 2 consecutive cycles.

- The symptoms are sufficient in severity to affect activities of daily living and/or important relationships.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder. PMDD is another common premenstrual disorder. It is distinguished by significant premenstrual psychological symptoms and requires the presence of marked affective lability, marked irritability or anger, markedly depressed mood, and/or marked anxiety (TABLE 1).7

Exacerbation of other ailments. Another premenstrual disorder is the premenstrual exacerbation of underlying chronic medical or psychological problems such as migraines, seizures, asthma, diabetes, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, anxiety, or depression.

Differences in interpretation lead to variations in prevalence

Differences in the interpretation of significant premenstrual symptoms have led to variations in estimated prevalence. For example, 80% to 95% of women report premenstrual symptoms, but only 30% to 40% meet criteria for PMS and only 3% to 8% meet criteria for PMDD.8 Many women who report premenstrual symptoms in a retrospective questionnaire do not meet criteria for PMS or PMDD based on prospective symptom charting. The Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP), a prospective tracking tool for premenstrual symptoms, is sensitive and specific for diagnosing PMS and PMDD if administered on the first day of menstruation.9

Ask about symptoms and use a tracking tool

When you see a woman for a well-woman visit or a gynecologic problem, inquire about physical/emotional symptoms and their severity during the week that precedes menstruation. If a patient reports few symptoms of a mild nature, then no further work-up is needed.

Continue to: If patients report significant...

If patients report significant premenstrual symptoms, recommend the use of a tool to track the symptoms. Older tools such as the DRSP and the Premenstrual Symptoms Screening Tool (PSST), newer symptom diaries that can be used for both PMS and PMDD,and questionnaires that have been used in research situations can be time consuming and difficult for patients to complete.10-12 Instead, physicians can easily construct their own charting tool, as we did for patients to use when tracking their most bothersome symptoms (FIGURE 1). Tracking helps to confirm the diagnosis and helps you and the patient focus on treatment goals.