User login

Diabetes targets remain elusive for patients

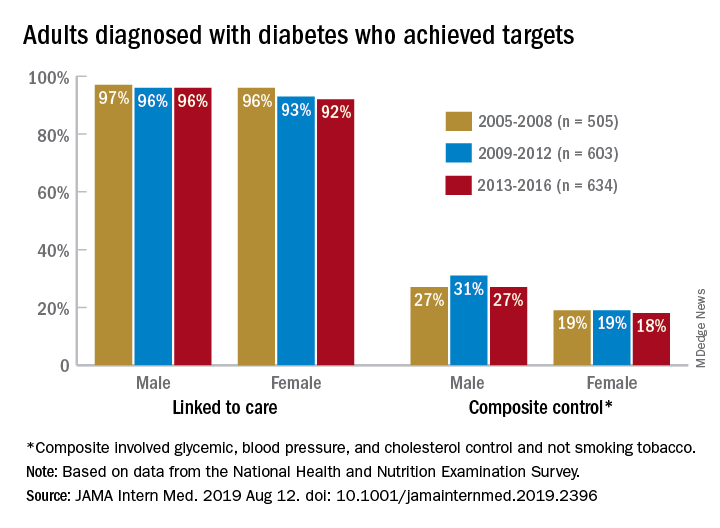

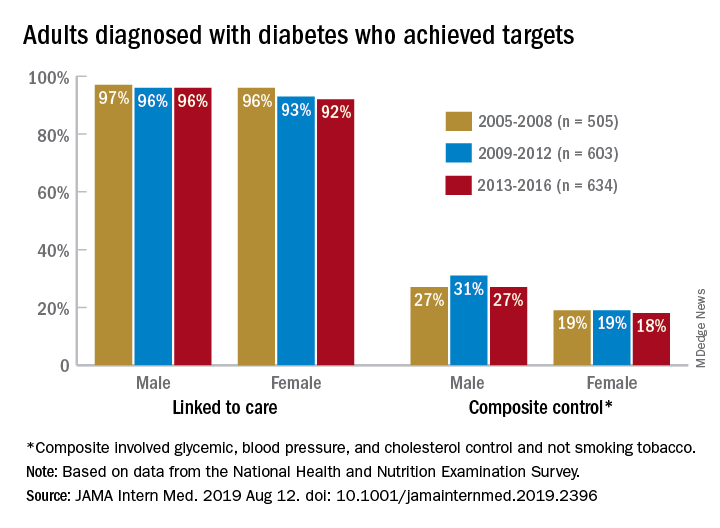

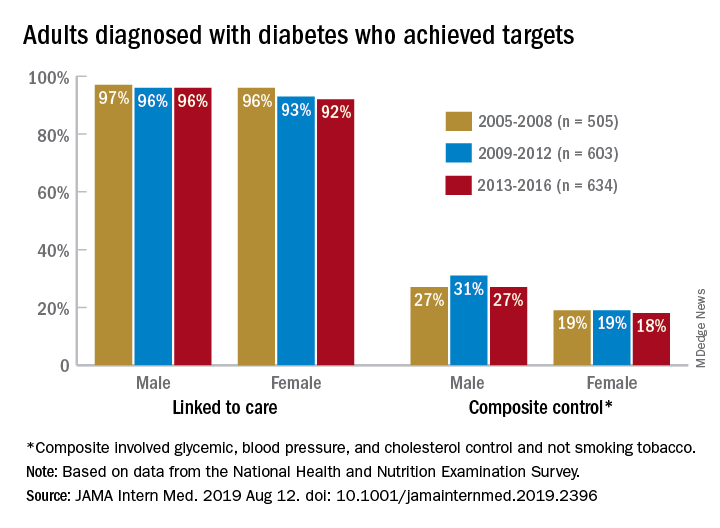

Some things never change: In 2005, most adults with diabetes missed their treatment targets. In 2016, most adults with diabetes missed their treatment targets. And during that time, from 2005 to 2016, around 96% of men and 94% of women were linked to care.

“Fewer than one in four American adults with diagnosed diabetes achieve a controlled level of blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol, and do not smoke tobacco. Our results suggest that, despite major advances in diabetes drug discovery and movement to develop innovative care delivery models over the past two decades, achievement of diabetes care targets has not improved in the United States since 2005,” Pooyan Kazemian, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in a written statement.

During 2013-2016, only 23% of adults with diabetes met a combined composite target of glycemic (HbA1c below a liberal personalized level), blood pressure (less than 140/90 mm Hg), and cholesterol (LDL cholesterol level less than 100 mg/dL) control, as well as not smoking tobacco, Dr. Kazemian and associates reported in JAMA Internal Medicine. The corresponding figures were 25% (2009-2012) and 23% (2005-2008) for the two earlier time periods covered in the study,

The investigators used data for 1,742 nonpregnant adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to evaluate the diabetes care cascade, which they defined as “diagnosis, linkage to care, achievement of individual treatment targets, and a composite of all individual targets.”

In 2013-2016, 94% of those diagnosed were linked to care, 64% met their HbA1c target, 70% achieved blood pressure control, 57% met the cholesterol target, and 85% were nonsmokers. When targets were combined, 41% achieved blood pressure and cholesterol control, and 25% met the glycemic, blood pressure, and cholesterol targets, they said.

“We found that none of the U.S. diabetes care variables improved from 2005 to 2016,” Dr. Kazemian and associates noted. Women were less likely than men to meet their treatment goals (see graph) over the course of the study, as were adults aged 18-44 years and black and Hispanic individuals.

“Recent advances in [treatments for diabetes] have not effectively reached the populations at risk and may indicate an immediate need for better approaches to the delivery of diabetes care, including a continued focus on reaching underserved populations with persistent disparities in care,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Boston Area Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center and Massachusetts General Hospital. One investigator reported that her husband has equity in Apolo1bio. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Kazemian P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2396.

Some things never change: In 2005, most adults with diabetes missed their treatment targets. In 2016, most adults with diabetes missed their treatment targets. And during that time, from 2005 to 2016, around 96% of men and 94% of women were linked to care.

“Fewer than one in four American adults with diagnosed diabetes achieve a controlled level of blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol, and do not smoke tobacco. Our results suggest that, despite major advances in diabetes drug discovery and movement to develop innovative care delivery models over the past two decades, achievement of diabetes care targets has not improved in the United States since 2005,” Pooyan Kazemian, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in a written statement.

During 2013-2016, only 23% of adults with diabetes met a combined composite target of glycemic (HbA1c below a liberal personalized level), blood pressure (less than 140/90 mm Hg), and cholesterol (LDL cholesterol level less than 100 mg/dL) control, as well as not smoking tobacco, Dr. Kazemian and associates reported in JAMA Internal Medicine. The corresponding figures were 25% (2009-2012) and 23% (2005-2008) for the two earlier time periods covered in the study,

The investigators used data for 1,742 nonpregnant adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to evaluate the diabetes care cascade, which they defined as “diagnosis, linkage to care, achievement of individual treatment targets, and a composite of all individual targets.”

In 2013-2016, 94% of those diagnosed were linked to care, 64% met their HbA1c target, 70% achieved blood pressure control, 57% met the cholesterol target, and 85% were nonsmokers. When targets were combined, 41% achieved blood pressure and cholesterol control, and 25% met the glycemic, blood pressure, and cholesterol targets, they said.

“We found that none of the U.S. diabetes care variables improved from 2005 to 2016,” Dr. Kazemian and associates noted. Women were less likely than men to meet their treatment goals (see graph) over the course of the study, as were adults aged 18-44 years and black and Hispanic individuals.

“Recent advances in [treatments for diabetes] have not effectively reached the populations at risk and may indicate an immediate need for better approaches to the delivery of diabetes care, including a continued focus on reaching underserved populations with persistent disparities in care,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Boston Area Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center and Massachusetts General Hospital. One investigator reported that her husband has equity in Apolo1bio. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Kazemian P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2396.

Some things never change: In 2005, most adults with diabetes missed their treatment targets. In 2016, most adults with diabetes missed their treatment targets. And during that time, from 2005 to 2016, around 96% of men and 94% of women were linked to care.

“Fewer than one in four American adults with diagnosed diabetes achieve a controlled level of blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol, and do not smoke tobacco. Our results suggest that, despite major advances in diabetes drug discovery and movement to develop innovative care delivery models over the past two decades, achievement of diabetes care targets has not improved in the United States since 2005,” Pooyan Kazemian, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in a written statement.

During 2013-2016, only 23% of adults with diabetes met a combined composite target of glycemic (HbA1c below a liberal personalized level), blood pressure (less than 140/90 mm Hg), and cholesterol (LDL cholesterol level less than 100 mg/dL) control, as well as not smoking tobacco, Dr. Kazemian and associates reported in JAMA Internal Medicine. The corresponding figures were 25% (2009-2012) and 23% (2005-2008) for the two earlier time periods covered in the study,

The investigators used data for 1,742 nonpregnant adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to evaluate the diabetes care cascade, which they defined as “diagnosis, linkage to care, achievement of individual treatment targets, and a composite of all individual targets.”

In 2013-2016, 94% of those diagnosed were linked to care, 64% met their HbA1c target, 70% achieved blood pressure control, 57% met the cholesterol target, and 85% were nonsmokers. When targets were combined, 41% achieved blood pressure and cholesterol control, and 25% met the glycemic, blood pressure, and cholesterol targets, they said.

“We found that none of the U.S. diabetes care variables improved from 2005 to 2016,” Dr. Kazemian and associates noted. Women were less likely than men to meet their treatment goals (see graph) over the course of the study, as were adults aged 18-44 years and black and Hispanic individuals.

“Recent advances in [treatments for diabetes] have not effectively reached the populations at risk and may indicate an immediate need for better approaches to the delivery of diabetes care, including a continued focus on reaching underserved populations with persistent disparities in care,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Boston Area Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center and Massachusetts General Hospital. One investigator reported that her husband has equity in Apolo1bio. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Kazemian P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2396.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

USPSTF draft guidance calls for drug use screening

according to a draft recommendation statement now available for public comment.

The statement defines illicit drug use as “use of illegal drugs and the nonmedical use of prescription psychoactive medications (i.e., use for reasons, for duration, in amounts, or with frequency other than prescribed or use by persons other than the prescribed individual).”

The guidelines do not apply to individuals younger than 18 years, for whom the USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend routine screening, or to adults currently diagnosed or in treatment for a drug use disorder.

In the draft recommendation statement, available online, the USPSTF noted that several screening tools are available for use in primary care practices, including the BSTAD (Brief Screener for Tobacco, Alcohol, and Other Drugs) that consists of six questions. The task force noted that they have found “adequate evidence” that these screening tools can detect illicit drug use. In addition, they wrote that no studies offer evidence of benefits versus harms of these screening tools, and evidence of harms associated with screening are limited.

Screening intervals can be simplified by screening young adults whenever they seek medical services and when clinicians suspect illicit drug use, the USPSTF said.

When the draft recommendation is finalized, it will replace the 2008 recommendation, which found insufficient evidence for screening in adults, as well as in adolescents. New evidence since 2008 supports the value of screening for adults aged 18 years and older, including pregnant and postpartum women.

The draft recommendations are based on the results of two systematic evidence reviews that assessed the accuracy and harms of routine illicit drug use screening. The USPSTF’s review included 12 studies on the accuracy of 15 screening tools. Overall, the sensitivity of direct screening tools to identify “unhealthy use of ‘any drug’ (including illegal drugs and nonmedical use of prescription drugs) in the past month or year” ranged from 0.71 to 0.94, and the specificity ranged from 0.87 to 0.97.

Based on the current evidence, the USPSTF assigned drug screening for adults a grade B recommendation, defined as “high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.”

For treatment, the Task Force found evidence to support strategies including pharmacotherapy with naltrexone, buprenorphine, and methadone, as well as for psychosocial interventions.

The USPSTF acknowledged that many factors may affect a clinicians’ decision of whether to implement the drug screening recommendation. “In many communities, affordable, accessible, and timely services for diagnostic assessment and treatment for patients with positive screening results are in limited supply or unaffordable. Providers should be aware of any state requirements for mandatory screening or reporting of screening results to medicolegal authorities and understand the positive and negative implications of reporting,” they wrote.

The draft recommendations also identified several research gaps including the effectiveness of screening for illicit drug use in adolescents, the optimal screening interval for all patients, the accuracy of screening tools for detecting opioids, the accuracy of screening within the same population, the benefits of naloxone as rescue therapy, and nonmedical use of other prescription drugs, as well as ways to improve access to care for those diagnosed with drug use disorders.

The draft recommendation is available for public comment until Sept. 9, 2019, at 8 p.m. EST.

The USPSTF is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

according to a draft recommendation statement now available for public comment.

The statement defines illicit drug use as “use of illegal drugs and the nonmedical use of prescription psychoactive medications (i.e., use for reasons, for duration, in amounts, or with frequency other than prescribed or use by persons other than the prescribed individual).”

The guidelines do not apply to individuals younger than 18 years, for whom the USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend routine screening, or to adults currently diagnosed or in treatment for a drug use disorder.

In the draft recommendation statement, available online, the USPSTF noted that several screening tools are available for use in primary care practices, including the BSTAD (Brief Screener for Tobacco, Alcohol, and Other Drugs) that consists of six questions. The task force noted that they have found “adequate evidence” that these screening tools can detect illicit drug use. In addition, they wrote that no studies offer evidence of benefits versus harms of these screening tools, and evidence of harms associated with screening are limited.

Screening intervals can be simplified by screening young adults whenever they seek medical services and when clinicians suspect illicit drug use, the USPSTF said.

When the draft recommendation is finalized, it will replace the 2008 recommendation, which found insufficient evidence for screening in adults, as well as in adolescents. New evidence since 2008 supports the value of screening for adults aged 18 years and older, including pregnant and postpartum women.

The draft recommendations are based on the results of two systematic evidence reviews that assessed the accuracy and harms of routine illicit drug use screening. The USPSTF’s review included 12 studies on the accuracy of 15 screening tools. Overall, the sensitivity of direct screening tools to identify “unhealthy use of ‘any drug’ (including illegal drugs and nonmedical use of prescription drugs) in the past month or year” ranged from 0.71 to 0.94, and the specificity ranged from 0.87 to 0.97.

Based on the current evidence, the USPSTF assigned drug screening for adults a grade B recommendation, defined as “high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.”

For treatment, the Task Force found evidence to support strategies including pharmacotherapy with naltrexone, buprenorphine, and methadone, as well as for psychosocial interventions.

The USPSTF acknowledged that many factors may affect a clinicians’ decision of whether to implement the drug screening recommendation. “In many communities, affordable, accessible, and timely services for diagnostic assessment and treatment for patients with positive screening results are in limited supply or unaffordable. Providers should be aware of any state requirements for mandatory screening or reporting of screening results to medicolegal authorities and understand the positive and negative implications of reporting,” they wrote.

The draft recommendations also identified several research gaps including the effectiveness of screening for illicit drug use in adolescents, the optimal screening interval for all patients, the accuracy of screening tools for detecting opioids, the accuracy of screening within the same population, the benefits of naloxone as rescue therapy, and nonmedical use of other prescription drugs, as well as ways to improve access to care for those diagnosed with drug use disorders.

The draft recommendation is available for public comment until Sept. 9, 2019, at 8 p.m. EST.

The USPSTF is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

according to a draft recommendation statement now available for public comment.

The statement defines illicit drug use as “use of illegal drugs and the nonmedical use of prescription psychoactive medications (i.e., use for reasons, for duration, in amounts, or with frequency other than prescribed or use by persons other than the prescribed individual).”

The guidelines do not apply to individuals younger than 18 years, for whom the USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend routine screening, or to adults currently diagnosed or in treatment for a drug use disorder.

In the draft recommendation statement, available online, the USPSTF noted that several screening tools are available for use in primary care practices, including the BSTAD (Brief Screener for Tobacco, Alcohol, and Other Drugs) that consists of six questions. The task force noted that they have found “adequate evidence” that these screening tools can detect illicit drug use. In addition, they wrote that no studies offer evidence of benefits versus harms of these screening tools, and evidence of harms associated with screening are limited.

Screening intervals can be simplified by screening young adults whenever they seek medical services and when clinicians suspect illicit drug use, the USPSTF said.

When the draft recommendation is finalized, it will replace the 2008 recommendation, which found insufficient evidence for screening in adults, as well as in adolescents. New evidence since 2008 supports the value of screening for adults aged 18 years and older, including pregnant and postpartum women.

The draft recommendations are based on the results of two systematic evidence reviews that assessed the accuracy and harms of routine illicit drug use screening. The USPSTF’s review included 12 studies on the accuracy of 15 screening tools. Overall, the sensitivity of direct screening tools to identify “unhealthy use of ‘any drug’ (including illegal drugs and nonmedical use of prescription drugs) in the past month or year” ranged from 0.71 to 0.94, and the specificity ranged from 0.87 to 0.97.

Based on the current evidence, the USPSTF assigned drug screening for adults a grade B recommendation, defined as “high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.”

For treatment, the Task Force found evidence to support strategies including pharmacotherapy with naltrexone, buprenorphine, and methadone, as well as for psychosocial interventions.

The USPSTF acknowledged that many factors may affect a clinicians’ decision of whether to implement the drug screening recommendation. “In many communities, affordable, accessible, and timely services for diagnostic assessment and treatment for patients with positive screening results are in limited supply or unaffordable. Providers should be aware of any state requirements for mandatory screening or reporting of screening results to medicolegal authorities and understand the positive and negative implications of reporting,” they wrote.

The draft recommendations also identified several research gaps including the effectiveness of screening for illicit drug use in adolescents, the optimal screening interval for all patients, the accuracy of screening tools for detecting opioids, the accuracy of screening within the same population, the benefits of naloxone as rescue therapy, and nonmedical use of other prescription drugs, as well as ways to improve access to care for those diagnosed with drug use disorders.

The draft recommendation is available for public comment until Sept. 9, 2019, at 8 p.m. EST.

The USPSTF is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE USPSTF

Lamotrigine-Induced Cutaneous Pseudolymphoma

To the Editor:

An 8-year-old girl presented with new lesions on the scalp that were mildly painful to palpation and had been increasing in size and number over the last 2 months. Her medical history was remarkable for seizures, keratosis pilaris, and seborrheic dermatitis. The seizures had been well controlled on oxcarbazepine; however, she was switched to lamotrigine 6 months prior to presentation under the care of her neurologist. The patient was not taking other oral medications, and she denied any trauma/insect bites to the affected area or systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, weight loss, nausea, swollen lymph nodes, or night sweats. Physical examination revealed 3 well-circumscribed, pink, slightly scaly, indurated nodules on the frontal and vertex scalp (Figure 1). She reported pain on palpation of the lesions. Treatment with ketoconazole shampoo and high-potency topical corticosteroids was ineffective.

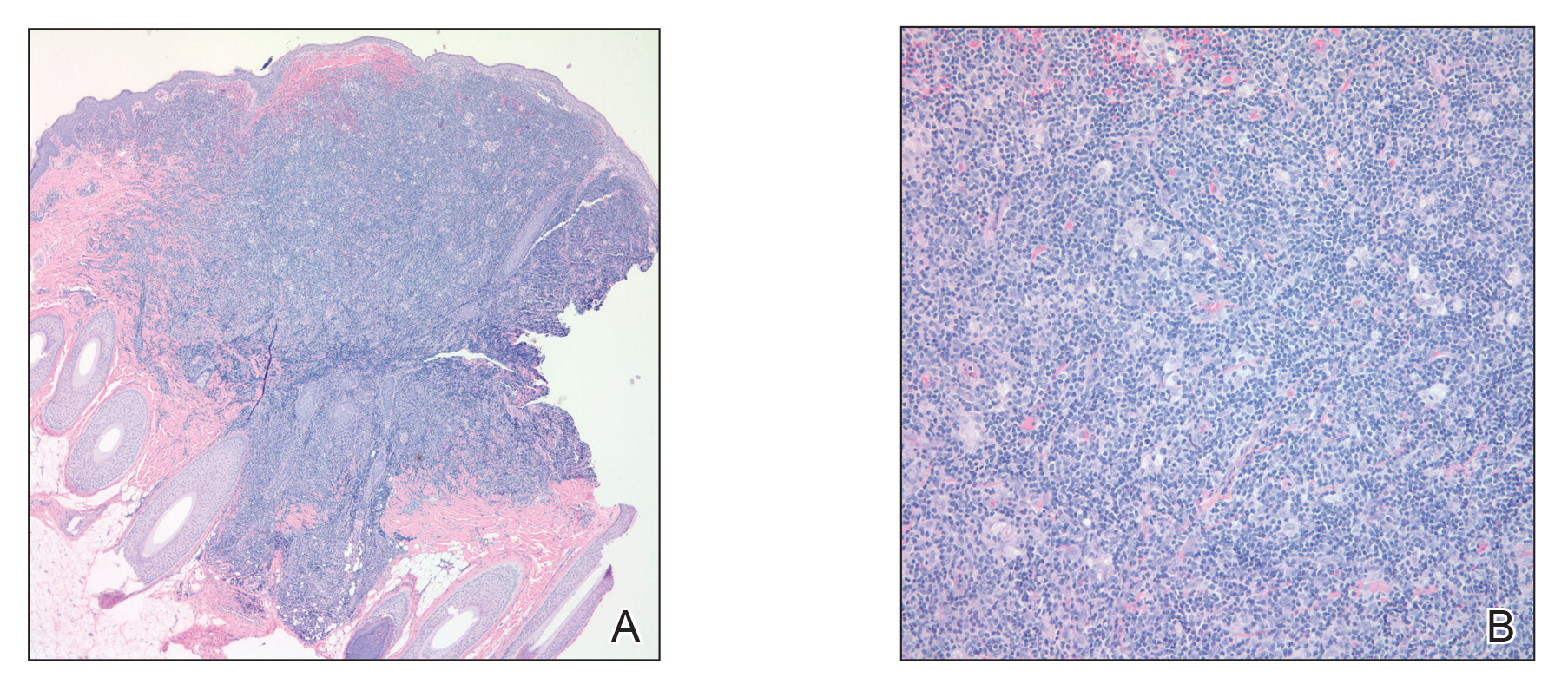

Over a period of 2 months after the initial presentation, the patient developed a total of 9 scalp lesions. Testing was performed 4 months after presentation of lesions. Bacterial and fungal cultures of the lesional skin of the scalp were negative. Two biopsies of lesions on the scalp were performed, the first of which showed a nonspecific lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. The second biopsy revealed a dense, nodular, atypical dermal lymphoid infiltrate composed primarily of round regular lymphocytes intermixed with some larger, more irregular lymphocytes and few scattered mitoses (Figure 2).

Immunohistochemical studies revealed small B-cell lymphoma 2–positive lymphocytes with a 2:1 mixture of CD3+ T cells and CD20+CD79a+ B cells. The T cells expressed CD2, CD5, and CD43, and a subset showed a loss of CD7. The CD4:CD8 ratio was 10 to 1. No follicular dendritic networks were noted with CD21 and CD23. Rare, scattered, medium-sized CD30 cells were noted. Staining for CD10, B-cell lymphoma 6, anaplastic lymphoma kinase, Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA 1, IgD, and IgM were negative. The plasma cells had a κ/λ free light chain ratio of 2 to 1. Ki-67 was positive in 15% of lymphoid cells. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of T-cell receptor gene rearrangement revealed a peak at 228 bp in a predominantly polyclonal background. A thorough systemic workup including complete blood cell count, immunoglobulin assay, bone marrow transplant panel, comprehensive metabolic panel, lactate dehydrogenase test, inflammatory markers, and viral testing failed to reveal any evidence of underlying malignancy.

After conferring with the patient’s neurologist, lamotrigine was discontinued. Within a few weeks of cessation, the scalp lesions resolved without recurrence at 9-month follow-up. In addition to the lack of clinical, histological, or immunohistochemical evidence of underlying malignancy, the temporal association of the development of lesions after starting lamotrigine and rapid resolution upon its discontinuation suggested a diagnosis of lamotrigine-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma.

Cutaneous pseudolymphoma is a term used to describe a heterogenous group of benign reactive T-cell, B-cell, or mixed-cell lymphoproliferative processes that resemble cutaneous lymphomas clinically and/or histopathologically.1 Historically, these types of proliferations have been classified under many alternative names that originally served to describe only B-cell–type proliferations. With advances in immunohistochemistry allowing for more specific cell marker identification, cutaneous pseudolymphomas often are found to contain a mixture of T-cell and B-cell populations, which also led to identifying and describing T-cell–type pseudolymphomas.2

The clinical appearance of cutaneous pseudolymphoma is variable, ranging from discrete nodules or papules to even confluent erythroderma in certain cases.2 The high clinical variability further complicates diagnosis. Although our patient presented with 9 individual nodular lesions, this finding alone is not sufficient to have high suspicion for cutaneous pseudolymphoma without including a much broader differential diagnosis. In our case, the differential diagnosis also included cutaneous lymphoma, arthropod bite reaction, lymphomatoid papulosis, tumid lupus, follicular mucinosis, lymphocytic infiltrate of Jessner, and leukemia cutis.

The primary concern regarding diagnosis of cutaneous pseudolymphoma is the clinician’s ability to effectively differentiate this entity from a true malignant lymphoma. Immunostaining has some value by identification of heterogeneous cell–type populations with a mixed T-cell and B-cell infiltrate that is more characteristic of a benign reactive process. Subsequent polymerase chain reaction analysis can detect the presence or absence of monoclonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangement or immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement.3 If these monoclonal rearrangements are absent, a benign diagnosis is favored; however, these rearrangements also have been shown to exist in a case of cutaneous pseudolymphoma that earned the final diagnosis when removal of the offending agent led to spontaneous lesion regression, similar to our case.4

Many different entities have been described as causative factors for the development of cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Of those that have been considered causative, simple categories have emerged, including endogenous, exogenous, and iatrogenic causes. One potential endogenous etiology of cutaneous pseudolymphoma is IgG4-related disease.5 A multitude of exogenous causes have been reported, including several cases of cutaneous pseudolymphoma developing in a prior tattoo site.6 Viruses, specifically molluscum contagiosum, also have been implicated as exogenous causes, and a report of cutaneous pseudolymphoma development at a prior site of herpes zoster lesions has been described.7 Development of cutaneous pseudolymphoma in vaccination sites also has been reported,8 as well as more obscure inciting events such as Leishmania donovani infection and medicinal leech therapy.9

A considerable number of reported cases of cutaneous pseudolymphoma have been attributed to drugs, including monoclonal antibodies,10 herbal supplements,11 and a multitude of other medications.1 As a class, anticonvulsants are considered more likely to cause lymph node pseudolymphomas than strictly cutaneous pseudolymphomas12; however, many drugs in this class of medications have been described in the development of cutaneous pseudolymphoma.3 A review of the literature by Ploysangam et al1 revealed reports of the development of cutaneous pseudolymphomas after administration of phenytoin, carbamazepine, mephenytoin, trimethadione, phenobarbital, primidone, butabarbital, methsuximide, phensuximide, and valproic acid.

Our patient represents a rare case of strictly cutaneous pseudolymphoma caused by administration of lamotrigine. Our case demonstrated a clear temporal relation between the cessation of lamotrigine and rapid and spontaneous disappearance of cutaneous lesions. We found another case of pseudolymphoma in which lamotrigine was deemed causative, but only lymph node involvement was observed.12

Proper diagnosis of cutaneous pseudolymphoma is important not only with regard to the initial differentiation from true malignant lymphoma but in allowing for appropriate follow-up and vigilant surveillance. Cases of progression from cutaneous pseudolymphoma to true lymphoma have been reported.1,2 It is recommended that watchful follow-up for these patients be carried out until at least 5 years after the diagnosis of cutaneous pseudolymphoma is made to rule out the possibility of malignant transformation, particularly in idiopathic cases.13

- Ploysangam T, Breneman D, Mutasim D. Cutaneous pseudolymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:877-898.

- Bergman R. Pseudolymphoma and cutaneous lymphoma: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:568-574.

- Braddock S, Harrington D, Vose J. Generalized nodular cutaneous pseudolymphoma associated with phenytoin therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:337-340.

- Cogrel O, Beylot-Barry M, Vergier B, et al. Sodium valproate-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma followed by recurrence with carbamazepine. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1235-1238.

- Cheuk W, Lee K, Chong L, et al. IgG4-related sclerosing disease: a potential new etiology of cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1713-1719.

- Marchesi A, Parodi P, Brioschi M, et al. Tattoo ink-related cutaneous pseudolymphomas: a rare but significant complication. case report and review of the literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38:471-478.

- Gonzalez J, Sanz A, Martin T, et al. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma associated with molluscum contagiosum: a case report. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:502-504.

- Maubec E, Pinquier L, Viguier M, et al. Vaccination-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:623-629.

- Altamura D, Calonje E, Liau J, et al. Diffuse cutaneous pseudolymphoma due to therapy with medicinal leeches. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:783-784.

- Imafuku S, Ito K, Nakayama J. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma induced by adalimumab and reproduced by infliximab in a patient with arthopathic psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2011;166:675-678.

- Meyer S, Vogt T, Obermann EC, et al. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma induced by Cimicifuga racemosa. Dermatology. 2007;214:94-96.

- Pathak P, McLachlan R. Drug-induced pseudolymphoma secondary to lamotrigine. Neurology. 1998;50:1509-1510.

- Prabu V, Shivani A, Pawar V. Idiopathic cutaneous pseudolymphoma: an enigma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:224-226.

To the Editor:

An 8-year-old girl presented with new lesions on the scalp that were mildly painful to palpation and had been increasing in size and number over the last 2 months. Her medical history was remarkable for seizures, keratosis pilaris, and seborrheic dermatitis. The seizures had been well controlled on oxcarbazepine; however, she was switched to lamotrigine 6 months prior to presentation under the care of her neurologist. The patient was not taking other oral medications, and she denied any trauma/insect bites to the affected area or systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, weight loss, nausea, swollen lymph nodes, or night sweats. Physical examination revealed 3 well-circumscribed, pink, slightly scaly, indurated nodules on the frontal and vertex scalp (Figure 1). She reported pain on palpation of the lesions. Treatment with ketoconazole shampoo and high-potency topical corticosteroids was ineffective.

Over a period of 2 months after the initial presentation, the patient developed a total of 9 scalp lesions. Testing was performed 4 months after presentation of lesions. Bacterial and fungal cultures of the lesional skin of the scalp were negative. Two biopsies of lesions on the scalp were performed, the first of which showed a nonspecific lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. The second biopsy revealed a dense, nodular, atypical dermal lymphoid infiltrate composed primarily of round regular lymphocytes intermixed with some larger, more irregular lymphocytes and few scattered mitoses (Figure 2).

Immunohistochemical studies revealed small B-cell lymphoma 2–positive lymphocytes with a 2:1 mixture of CD3+ T cells and CD20+CD79a+ B cells. The T cells expressed CD2, CD5, and CD43, and a subset showed a loss of CD7. The CD4:CD8 ratio was 10 to 1. No follicular dendritic networks were noted with CD21 and CD23. Rare, scattered, medium-sized CD30 cells were noted. Staining for CD10, B-cell lymphoma 6, anaplastic lymphoma kinase, Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA 1, IgD, and IgM were negative. The plasma cells had a κ/λ free light chain ratio of 2 to 1. Ki-67 was positive in 15% of lymphoid cells. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of T-cell receptor gene rearrangement revealed a peak at 228 bp in a predominantly polyclonal background. A thorough systemic workup including complete blood cell count, immunoglobulin assay, bone marrow transplant panel, comprehensive metabolic panel, lactate dehydrogenase test, inflammatory markers, and viral testing failed to reveal any evidence of underlying malignancy.

After conferring with the patient’s neurologist, lamotrigine was discontinued. Within a few weeks of cessation, the scalp lesions resolved without recurrence at 9-month follow-up. In addition to the lack of clinical, histological, or immunohistochemical evidence of underlying malignancy, the temporal association of the development of lesions after starting lamotrigine and rapid resolution upon its discontinuation suggested a diagnosis of lamotrigine-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma.

Cutaneous pseudolymphoma is a term used to describe a heterogenous group of benign reactive T-cell, B-cell, or mixed-cell lymphoproliferative processes that resemble cutaneous lymphomas clinically and/or histopathologically.1 Historically, these types of proliferations have been classified under many alternative names that originally served to describe only B-cell–type proliferations. With advances in immunohistochemistry allowing for more specific cell marker identification, cutaneous pseudolymphomas often are found to contain a mixture of T-cell and B-cell populations, which also led to identifying and describing T-cell–type pseudolymphomas.2

The clinical appearance of cutaneous pseudolymphoma is variable, ranging from discrete nodules or papules to even confluent erythroderma in certain cases.2 The high clinical variability further complicates diagnosis. Although our patient presented with 9 individual nodular lesions, this finding alone is not sufficient to have high suspicion for cutaneous pseudolymphoma without including a much broader differential diagnosis. In our case, the differential diagnosis also included cutaneous lymphoma, arthropod bite reaction, lymphomatoid papulosis, tumid lupus, follicular mucinosis, lymphocytic infiltrate of Jessner, and leukemia cutis.

The primary concern regarding diagnosis of cutaneous pseudolymphoma is the clinician’s ability to effectively differentiate this entity from a true malignant lymphoma. Immunostaining has some value by identification of heterogeneous cell–type populations with a mixed T-cell and B-cell infiltrate that is more characteristic of a benign reactive process. Subsequent polymerase chain reaction analysis can detect the presence or absence of monoclonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangement or immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement.3 If these monoclonal rearrangements are absent, a benign diagnosis is favored; however, these rearrangements also have been shown to exist in a case of cutaneous pseudolymphoma that earned the final diagnosis when removal of the offending agent led to spontaneous lesion regression, similar to our case.4

Many different entities have been described as causative factors for the development of cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Of those that have been considered causative, simple categories have emerged, including endogenous, exogenous, and iatrogenic causes. One potential endogenous etiology of cutaneous pseudolymphoma is IgG4-related disease.5 A multitude of exogenous causes have been reported, including several cases of cutaneous pseudolymphoma developing in a prior tattoo site.6 Viruses, specifically molluscum contagiosum, also have been implicated as exogenous causes, and a report of cutaneous pseudolymphoma development at a prior site of herpes zoster lesions has been described.7 Development of cutaneous pseudolymphoma in vaccination sites also has been reported,8 as well as more obscure inciting events such as Leishmania donovani infection and medicinal leech therapy.9

A considerable number of reported cases of cutaneous pseudolymphoma have been attributed to drugs, including monoclonal antibodies,10 herbal supplements,11 and a multitude of other medications.1 As a class, anticonvulsants are considered more likely to cause lymph node pseudolymphomas than strictly cutaneous pseudolymphomas12; however, many drugs in this class of medications have been described in the development of cutaneous pseudolymphoma.3 A review of the literature by Ploysangam et al1 revealed reports of the development of cutaneous pseudolymphomas after administration of phenytoin, carbamazepine, mephenytoin, trimethadione, phenobarbital, primidone, butabarbital, methsuximide, phensuximide, and valproic acid.

Our patient represents a rare case of strictly cutaneous pseudolymphoma caused by administration of lamotrigine. Our case demonstrated a clear temporal relation between the cessation of lamotrigine and rapid and spontaneous disappearance of cutaneous lesions. We found another case of pseudolymphoma in which lamotrigine was deemed causative, but only lymph node involvement was observed.12

Proper diagnosis of cutaneous pseudolymphoma is important not only with regard to the initial differentiation from true malignant lymphoma but in allowing for appropriate follow-up and vigilant surveillance. Cases of progression from cutaneous pseudolymphoma to true lymphoma have been reported.1,2 It is recommended that watchful follow-up for these patients be carried out until at least 5 years after the diagnosis of cutaneous pseudolymphoma is made to rule out the possibility of malignant transformation, particularly in idiopathic cases.13

To the Editor:

An 8-year-old girl presented with new lesions on the scalp that were mildly painful to palpation and had been increasing in size and number over the last 2 months. Her medical history was remarkable for seizures, keratosis pilaris, and seborrheic dermatitis. The seizures had been well controlled on oxcarbazepine; however, she was switched to lamotrigine 6 months prior to presentation under the care of her neurologist. The patient was not taking other oral medications, and she denied any trauma/insect bites to the affected area or systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, weight loss, nausea, swollen lymph nodes, or night sweats. Physical examination revealed 3 well-circumscribed, pink, slightly scaly, indurated nodules on the frontal and vertex scalp (Figure 1). She reported pain on palpation of the lesions. Treatment with ketoconazole shampoo and high-potency topical corticosteroids was ineffective.

Over a period of 2 months after the initial presentation, the patient developed a total of 9 scalp lesions. Testing was performed 4 months after presentation of lesions. Bacterial and fungal cultures of the lesional skin of the scalp were negative. Two biopsies of lesions on the scalp were performed, the first of which showed a nonspecific lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. The second biopsy revealed a dense, nodular, atypical dermal lymphoid infiltrate composed primarily of round regular lymphocytes intermixed with some larger, more irregular lymphocytes and few scattered mitoses (Figure 2).

Immunohistochemical studies revealed small B-cell lymphoma 2–positive lymphocytes with a 2:1 mixture of CD3+ T cells and CD20+CD79a+ B cells. The T cells expressed CD2, CD5, and CD43, and a subset showed a loss of CD7. The CD4:CD8 ratio was 10 to 1. No follicular dendritic networks were noted with CD21 and CD23. Rare, scattered, medium-sized CD30 cells were noted. Staining for CD10, B-cell lymphoma 6, anaplastic lymphoma kinase, Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA 1, IgD, and IgM were negative. The plasma cells had a κ/λ free light chain ratio of 2 to 1. Ki-67 was positive in 15% of lymphoid cells. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of T-cell receptor gene rearrangement revealed a peak at 228 bp in a predominantly polyclonal background. A thorough systemic workup including complete blood cell count, immunoglobulin assay, bone marrow transplant panel, comprehensive metabolic panel, lactate dehydrogenase test, inflammatory markers, and viral testing failed to reveal any evidence of underlying malignancy.

After conferring with the patient’s neurologist, lamotrigine was discontinued. Within a few weeks of cessation, the scalp lesions resolved without recurrence at 9-month follow-up. In addition to the lack of clinical, histological, or immunohistochemical evidence of underlying malignancy, the temporal association of the development of lesions after starting lamotrigine and rapid resolution upon its discontinuation suggested a diagnosis of lamotrigine-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma.

Cutaneous pseudolymphoma is a term used to describe a heterogenous group of benign reactive T-cell, B-cell, or mixed-cell lymphoproliferative processes that resemble cutaneous lymphomas clinically and/or histopathologically.1 Historically, these types of proliferations have been classified under many alternative names that originally served to describe only B-cell–type proliferations. With advances in immunohistochemistry allowing for more specific cell marker identification, cutaneous pseudolymphomas often are found to contain a mixture of T-cell and B-cell populations, which also led to identifying and describing T-cell–type pseudolymphomas.2

The clinical appearance of cutaneous pseudolymphoma is variable, ranging from discrete nodules or papules to even confluent erythroderma in certain cases.2 The high clinical variability further complicates diagnosis. Although our patient presented with 9 individual nodular lesions, this finding alone is not sufficient to have high suspicion for cutaneous pseudolymphoma without including a much broader differential diagnosis. In our case, the differential diagnosis also included cutaneous lymphoma, arthropod bite reaction, lymphomatoid papulosis, tumid lupus, follicular mucinosis, lymphocytic infiltrate of Jessner, and leukemia cutis.

The primary concern regarding diagnosis of cutaneous pseudolymphoma is the clinician’s ability to effectively differentiate this entity from a true malignant lymphoma. Immunostaining has some value by identification of heterogeneous cell–type populations with a mixed T-cell and B-cell infiltrate that is more characteristic of a benign reactive process. Subsequent polymerase chain reaction analysis can detect the presence or absence of monoclonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangement or immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement.3 If these monoclonal rearrangements are absent, a benign diagnosis is favored; however, these rearrangements also have been shown to exist in a case of cutaneous pseudolymphoma that earned the final diagnosis when removal of the offending agent led to spontaneous lesion regression, similar to our case.4

Many different entities have been described as causative factors for the development of cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Of those that have been considered causative, simple categories have emerged, including endogenous, exogenous, and iatrogenic causes. One potential endogenous etiology of cutaneous pseudolymphoma is IgG4-related disease.5 A multitude of exogenous causes have been reported, including several cases of cutaneous pseudolymphoma developing in a prior tattoo site.6 Viruses, specifically molluscum contagiosum, also have been implicated as exogenous causes, and a report of cutaneous pseudolymphoma development at a prior site of herpes zoster lesions has been described.7 Development of cutaneous pseudolymphoma in vaccination sites also has been reported,8 as well as more obscure inciting events such as Leishmania donovani infection and medicinal leech therapy.9

A considerable number of reported cases of cutaneous pseudolymphoma have been attributed to drugs, including monoclonal antibodies,10 herbal supplements,11 and a multitude of other medications.1 As a class, anticonvulsants are considered more likely to cause lymph node pseudolymphomas than strictly cutaneous pseudolymphomas12; however, many drugs in this class of medications have been described in the development of cutaneous pseudolymphoma.3 A review of the literature by Ploysangam et al1 revealed reports of the development of cutaneous pseudolymphomas after administration of phenytoin, carbamazepine, mephenytoin, trimethadione, phenobarbital, primidone, butabarbital, methsuximide, phensuximide, and valproic acid.

Our patient represents a rare case of strictly cutaneous pseudolymphoma caused by administration of lamotrigine. Our case demonstrated a clear temporal relation between the cessation of lamotrigine and rapid and spontaneous disappearance of cutaneous lesions. We found another case of pseudolymphoma in which lamotrigine was deemed causative, but only lymph node involvement was observed.12

Proper diagnosis of cutaneous pseudolymphoma is important not only with regard to the initial differentiation from true malignant lymphoma but in allowing for appropriate follow-up and vigilant surveillance. Cases of progression from cutaneous pseudolymphoma to true lymphoma have been reported.1,2 It is recommended that watchful follow-up for these patients be carried out until at least 5 years after the diagnosis of cutaneous pseudolymphoma is made to rule out the possibility of malignant transformation, particularly in idiopathic cases.13

- Ploysangam T, Breneman D, Mutasim D. Cutaneous pseudolymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:877-898.

- Bergman R. Pseudolymphoma and cutaneous lymphoma: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:568-574.

- Braddock S, Harrington D, Vose J. Generalized nodular cutaneous pseudolymphoma associated with phenytoin therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:337-340.

- Cogrel O, Beylot-Barry M, Vergier B, et al. Sodium valproate-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma followed by recurrence with carbamazepine. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1235-1238.

- Cheuk W, Lee K, Chong L, et al. IgG4-related sclerosing disease: a potential new etiology of cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1713-1719.

- Marchesi A, Parodi P, Brioschi M, et al. Tattoo ink-related cutaneous pseudolymphomas: a rare but significant complication. case report and review of the literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38:471-478.

- Gonzalez J, Sanz A, Martin T, et al. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma associated with molluscum contagiosum: a case report. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:502-504.

- Maubec E, Pinquier L, Viguier M, et al. Vaccination-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:623-629.

- Altamura D, Calonje E, Liau J, et al. Diffuse cutaneous pseudolymphoma due to therapy with medicinal leeches. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:783-784.

- Imafuku S, Ito K, Nakayama J. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma induced by adalimumab and reproduced by infliximab in a patient with arthopathic psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2011;166:675-678.

- Meyer S, Vogt T, Obermann EC, et al. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma induced by Cimicifuga racemosa. Dermatology. 2007;214:94-96.

- Pathak P, McLachlan R. Drug-induced pseudolymphoma secondary to lamotrigine. Neurology. 1998;50:1509-1510.

- Prabu V, Shivani A, Pawar V. Idiopathic cutaneous pseudolymphoma: an enigma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:224-226.

- Ploysangam T, Breneman D, Mutasim D. Cutaneous pseudolymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:877-898.

- Bergman R. Pseudolymphoma and cutaneous lymphoma: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:568-574.

- Braddock S, Harrington D, Vose J. Generalized nodular cutaneous pseudolymphoma associated with phenytoin therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:337-340.

- Cogrel O, Beylot-Barry M, Vergier B, et al. Sodium valproate-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma followed by recurrence with carbamazepine. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1235-1238.

- Cheuk W, Lee K, Chong L, et al. IgG4-related sclerosing disease: a potential new etiology of cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1713-1719.

- Marchesi A, Parodi P, Brioschi M, et al. Tattoo ink-related cutaneous pseudolymphomas: a rare but significant complication. case report and review of the literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38:471-478.

- Gonzalez J, Sanz A, Martin T, et al. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma associated with molluscum contagiosum: a case report. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:502-504.

- Maubec E, Pinquier L, Viguier M, et al. Vaccination-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:623-629.

- Altamura D, Calonje E, Liau J, et al. Diffuse cutaneous pseudolymphoma due to therapy with medicinal leeches. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:783-784.

- Imafuku S, Ito K, Nakayama J. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma induced by adalimumab and reproduced by infliximab in a patient with arthopathic psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2011;166:675-678.

- Meyer S, Vogt T, Obermann EC, et al. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma induced by Cimicifuga racemosa. Dermatology. 2007;214:94-96.

- Pathak P, McLachlan R. Drug-induced pseudolymphoma secondary to lamotrigine. Neurology. 1998;50:1509-1510.

- Prabu V, Shivani A, Pawar V. Idiopathic cutaneous pseudolymphoma: an enigma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:224-226.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous pseudolymphomas are a heterogenous group of benign T-cell, B-cell, or mixed-cell lymphoproliferative processes that resemble cutaneous lymphomas clinically and/or histopathologically.

- Cutaneous pseudolymphomas have many causative factors, including medications, infections, tattoo ink, vaccinations, and insect bites.

- Lamotrigine is a potential inciting factor of cutaneous pseudolymphoma.

Social determinants of health gaining prominence

Fragmented, essentializing, simplistic. That’s how students at Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, described their required course on cultural competence. Lectures and discussions about cultural groups and communication issues weren’t providing them with the skills they needed to navigate doctor-patient relationships.

Their criticism was a wake-up call that Horace Delisser, MD, associate dean for diversity and inclusion at the school, took to heart. He enlisted medical students to help reinvent the curriculum. The result, Introduction to Medicine and Society, launched in 2013 and described in an article published in 2017 (Acad Med. 2017;92[3]:335-43), emphasizes self-awareness and reflection about one’s own biases and the adoption of a less hierarchical and more respectful “other-oriented” approach to the patient relationship.

The course examines social determinants of health (SDHs) – the influences of society, government, culture, and health systems. Students analyze how health and health outcomes are affected by a patient’s income, education, and living and working conditions, as well as access to healthy food, safe water, and transportation.

A host of policy makers, advisory groups, and organized medicine groups have called in recent years for educational efforts to boost all physicians’ working knowledge of health inequities and SDHs.

Dr. Delisser, associate professor of medicine who also practices as a pulmonologist at the Harron Lung Center in the Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine, said SDHs play into daily care.

Consider the patient who is chronically late for appointments. “It may not be an issue of the patient being disinterested in their health care, but maybe the public transportation system is unreliable, or maybe the patient has to take two buses and a subway to get there. I need [this knowledge] to inform my care and to engage my patient. I need to know, ‘what does it take for you to get here?’ That factors into how I [make the care plan],” said Dr. Delisser.

Malika Fair, MD, MPH, who teaches a longitudinal professional development class at George Washington University, Washington, and is senior director of health equity partnerships and programs at the American Association of Medical Colleges, provided the example of how her medical students intervened during their rotation in the emergency department on behalf of a newly-diagnosed patient with diabetes who had been unable to fill a prescribed medication. After determining where the patient lived, the students ensured that she had transportation and was able to get the needed medication at a local grocery store. They asked about her barriers to healthy eating, researched local grocery stores, and made practical recommendations that the patient was amenable to implementing. They identified a clinic closer to the patient’s home, and worked with her on making an appointment at a time when she could take off from work.

“Because of their training, these students were able to identify and address social risks in their first month on the ward,” said Dr. Fair, who also practices emergency medicine. They had learned about how to ask about food access and how safe it was for the patient to walk and exercise in her neighborhood.

At Perelman, most students work in student-led community clinics, and some fourth-year students participate in an elective rotation as apprentices to community health workers, learning to address SDHs and develop the cultural humility that they learned about in the classroom. The rotation was similarly created in 2013 and is described in a 2018 article (J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29[2]:581-90).“Being a good physician involves being technically competent as well as what I call relationally competent,” Dr. Delisser said. “And [this involves] being aware that my relationship with a patient doesn’t exist in a vacuum ... that there’s a bigger, broader social and structural context that I need to know and understand. I [then need] to use that to inform how I mediate and empower that relationship.”

Aletha Maybank, MD, who became the American Medical Association’s first chief health equity officer earlier this year, explained that “the medical profession had a very strong social context at one point in time,” but this was dampened by the Flexner Report of 1910.*

The report revolutionized medical education by increasing its rigor, but “it was really focused on clinical and basic science and took out the social context, the context of what medicine is about,” said Dr. Maybank, a pediatrician with a board certification in preventive medicine/public health. “[Now] we’re asking, how do we revolutionize medical education again at this point in time, recognizing the confluence of information and data that we now have available to us about inequities and disparities ... and the sense of urgency from students.”

Students driving practice change

Students nationally are “the most important” drivers of the increasing focus on SDHs in medical education, according to Dr. Fair. “They are demanding experiences to learn about the entire patient. We know that only 20% of a patient’s health is dependent on their health care. Our students are demanding education about the other 80%.”

More and more, communities are identifying needs and “students will then come up with initiatives to meet those needs,” Dr. Fair said.

Others interviewed for this story predicted this trend will only intensify, since not-for-profit hospitals are required under the Affordable Care Act regulations to assess community health needs every few years and to intervene accordingly.

Education on health care systems is also advancing. Penn State University, for instance, utilized a million-dollar grant from the AMA’s Accelerating Change in Medical Education initiative to design and implement a 4-year curriculum on the health system sciences that started in 2014. The curriculum includes an immersive experience in patient navigation.

“Students were taught to be patient navigators, and they were assigned within the clinical context to work on issues like, why are [patients] having trouble getting their medications?” said Susan E. Skochelak, MD, MPH, who leads the 6-year-old Accelerating Change initiative as vice president for medical education at the AMA.

From the start, she noted, students at Penn State are encouraged to question inequities, social and structural barriers to health, and faults in the health care system. “The message given at their white coat ceremony is ‘Welcome to medicine. Now that you’re here, you’re a member of the health care team, and we want you to speak up if you think there are things that need to be addressed. We want you to tell us when the system is working and not working,’ ” said Dr Skochelak, who previously served as the senior associate dean for academic affairs at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, where she had been a tenured professor of family medicine.

Tomorrow’s physician partners

Approximately 80% of medical school graduates who participated in the AAMC’s 2018 survey of graduates said they had received significant training on health disparities—up from 71% in 2014.

“There’s a huge amount [of innovation] happening, but on the flip side, there’s not really a set of accepted tools and practices, and certainly no robust evaluation [of the training],” said Philip M. Alberti, PhD, senior director for health equity research and policy at the American Association of Medical Colleges. A recently published review (J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34[5]:720-30) shows growing interest in the teaching of SDHs in undergraduate medical education but variable content, strategies, and instructional practices.

Health care systems and practicing physicians are still very much feeling their way with SDHs. Screening tools are being developed and tested, and academic medical centers are trying to determine their roles in addressing issues such as transportation and housing – and what funding and structural levers can be pulled to fulfill these roles. “As we learn more about [these issues], it will become clearer what the right baseline set of competencies might be for all physicians,” Dr. Alberti noted.

In the meantime, some basic expectations for medical education are taking root officially. The National Board of Medical Examiners, with whom the AMA has partnered in its Accelerating Change initiative, has included questions in the United States Medical Licensing Examination on population health and SDHs, and plans to add more exam content on these topics and on health systems science, said Dr. Skochelak.

And through its site visit program (the Clinical Learning Environment Review program), the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has “made it pretty clear that there’s an expectation that residents and fellows are learning about the health system’s approach to identifying and addressing health care disparities – and that they’re given opportunities to develop quality improvement initiatives that target those disparities,” Dr. Alberti said.

In hopes of achieving consistency across medical specialties and in national accreditation and board certifications exams, the American Association of Medical Colleges is developing its first set of competencies in quality improvement and patient safety, with health equity being one of these competencies’ domains .

The competencies are tiered for medical school graduates, residency graduates, and faculty physicians who are 3-5 years post residency. At this point in time, said Dr. Alberti, the consensus among medical educators has been that physicians “need to be able to understand and consider [social, economic, and structural] contexts when they’re seeing patients, when they’re developing care plans, when they’re talking with caregivers, and when they’re looking at their own quality data.”

Elisabeth Poorman, MD, MPH, an internist at UW Medicine in Kent, Washington, said she worries that the passion of medical students for SDHs will too often be crushed, especially during residency and with immersion in the productivity-focused health care system. Studies show a drop in mental wellness and empathy and a rise in cynicism as training advances, said Dr. Poorman, who also writes about health care and issues of equity and serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

With similar concerns, the AMA has recently launched a “Reimagining Residency” initiative that aims to improve transitions from medical school to residency and the wellness of residents and faculty, and expand educational content relating to SDHs.

Dr. Fair is optimistic that new physicians’ knowledge of SDHs will permeate medical practices.

“Physicians who are out practicing are going to be working with our graduates, and they’re going to be asking in [job] interviews, do you have flexible hours for patients? What community partnerships do you have? Are there other professionals on staff to help us address social determinants of health? What data [relating to SDHs] are you collecting?” she said.

Correction, 8/26/2019: An earlier version of this story misstated the title of Aletha Maybank, MD. Dr. Maybank's correct title is the first chief health equity officer of the American Medical Association.

Fragmented, essentializing, simplistic. That’s how students at Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, described their required course on cultural competence. Lectures and discussions about cultural groups and communication issues weren’t providing them with the skills they needed to navigate doctor-patient relationships.

Their criticism was a wake-up call that Horace Delisser, MD, associate dean for diversity and inclusion at the school, took to heart. He enlisted medical students to help reinvent the curriculum. The result, Introduction to Medicine and Society, launched in 2013 and described in an article published in 2017 (Acad Med. 2017;92[3]:335-43), emphasizes self-awareness and reflection about one’s own biases and the adoption of a less hierarchical and more respectful “other-oriented” approach to the patient relationship.

The course examines social determinants of health (SDHs) – the influences of society, government, culture, and health systems. Students analyze how health and health outcomes are affected by a patient’s income, education, and living and working conditions, as well as access to healthy food, safe water, and transportation.

A host of policy makers, advisory groups, and organized medicine groups have called in recent years for educational efforts to boost all physicians’ working knowledge of health inequities and SDHs.

Dr. Delisser, associate professor of medicine who also practices as a pulmonologist at the Harron Lung Center in the Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine, said SDHs play into daily care.

Consider the patient who is chronically late for appointments. “It may not be an issue of the patient being disinterested in their health care, but maybe the public transportation system is unreliable, or maybe the patient has to take two buses and a subway to get there. I need [this knowledge] to inform my care and to engage my patient. I need to know, ‘what does it take for you to get here?’ That factors into how I [make the care plan],” said Dr. Delisser.

Malika Fair, MD, MPH, who teaches a longitudinal professional development class at George Washington University, Washington, and is senior director of health equity partnerships and programs at the American Association of Medical Colleges, provided the example of how her medical students intervened during their rotation in the emergency department on behalf of a newly-diagnosed patient with diabetes who had been unable to fill a prescribed medication. After determining where the patient lived, the students ensured that she had transportation and was able to get the needed medication at a local grocery store. They asked about her barriers to healthy eating, researched local grocery stores, and made practical recommendations that the patient was amenable to implementing. They identified a clinic closer to the patient’s home, and worked with her on making an appointment at a time when she could take off from work.

“Because of their training, these students were able to identify and address social risks in their first month on the ward,” said Dr. Fair, who also practices emergency medicine. They had learned about how to ask about food access and how safe it was for the patient to walk and exercise in her neighborhood.

At Perelman, most students work in student-led community clinics, and some fourth-year students participate in an elective rotation as apprentices to community health workers, learning to address SDHs and develop the cultural humility that they learned about in the classroom. The rotation was similarly created in 2013 and is described in a 2018 article (J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29[2]:581-90).“Being a good physician involves being technically competent as well as what I call relationally competent,” Dr. Delisser said. “And [this involves] being aware that my relationship with a patient doesn’t exist in a vacuum ... that there’s a bigger, broader social and structural context that I need to know and understand. I [then need] to use that to inform how I mediate and empower that relationship.”

Aletha Maybank, MD, who became the American Medical Association’s first chief health equity officer earlier this year, explained that “the medical profession had a very strong social context at one point in time,” but this was dampened by the Flexner Report of 1910.*

The report revolutionized medical education by increasing its rigor, but “it was really focused on clinical and basic science and took out the social context, the context of what medicine is about,” said Dr. Maybank, a pediatrician with a board certification in preventive medicine/public health. “[Now] we’re asking, how do we revolutionize medical education again at this point in time, recognizing the confluence of information and data that we now have available to us about inequities and disparities ... and the sense of urgency from students.”

Students driving practice change

Students nationally are “the most important” drivers of the increasing focus on SDHs in medical education, according to Dr. Fair. “They are demanding experiences to learn about the entire patient. We know that only 20% of a patient’s health is dependent on their health care. Our students are demanding education about the other 80%.”

More and more, communities are identifying needs and “students will then come up with initiatives to meet those needs,” Dr. Fair said.

Others interviewed for this story predicted this trend will only intensify, since not-for-profit hospitals are required under the Affordable Care Act regulations to assess community health needs every few years and to intervene accordingly.

Education on health care systems is also advancing. Penn State University, for instance, utilized a million-dollar grant from the AMA’s Accelerating Change in Medical Education initiative to design and implement a 4-year curriculum on the health system sciences that started in 2014. The curriculum includes an immersive experience in patient navigation.

“Students were taught to be patient navigators, and they were assigned within the clinical context to work on issues like, why are [patients] having trouble getting their medications?” said Susan E. Skochelak, MD, MPH, who leads the 6-year-old Accelerating Change initiative as vice president for medical education at the AMA.

From the start, she noted, students at Penn State are encouraged to question inequities, social and structural barriers to health, and faults in the health care system. “The message given at their white coat ceremony is ‘Welcome to medicine. Now that you’re here, you’re a member of the health care team, and we want you to speak up if you think there are things that need to be addressed. We want you to tell us when the system is working and not working,’ ” said Dr Skochelak, who previously served as the senior associate dean for academic affairs at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, where she had been a tenured professor of family medicine.

Tomorrow’s physician partners

Approximately 80% of medical school graduates who participated in the AAMC’s 2018 survey of graduates said they had received significant training on health disparities—up from 71% in 2014.

“There’s a huge amount [of innovation] happening, but on the flip side, there’s not really a set of accepted tools and practices, and certainly no robust evaluation [of the training],” said Philip M. Alberti, PhD, senior director for health equity research and policy at the American Association of Medical Colleges. A recently published review (J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34[5]:720-30) shows growing interest in the teaching of SDHs in undergraduate medical education but variable content, strategies, and instructional practices.

Health care systems and practicing physicians are still very much feeling their way with SDHs. Screening tools are being developed and tested, and academic medical centers are trying to determine their roles in addressing issues such as transportation and housing – and what funding and structural levers can be pulled to fulfill these roles. “As we learn more about [these issues], it will become clearer what the right baseline set of competencies might be for all physicians,” Dr. Alberti noted.

In the meantime, some basic expectations for medical education are taking root officially. The National Board of Medical Examiners, with whom the AMA has partnered in its Accelerating Change initiative, has included questions in the United States Medical Licensing Examination on population health and SDHs, and plans to add more exam content on these topics and on health systems science, said Dr. Skochelak.

And through its site visit program (the Clinical Learning Environment Review program), the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has “made it pretty clear that there’s an expectation that residents and fellows are learning about the health system’s approach to identifying and addressing health care disparities – and that they’re given opportunities to develop quality improvement initiatives that target those disparities,” Dr. Alberti said.

In hopes of achieving consistency across medical specialties and in national accreditation and board certifications exams, the American Association of Medical Colleges is developing its first set of competencies in quality improvement and patient safety, with health equity being one of these competencies’ domains .

The competencies are tiered for medical school graduates, residency graduates, and faculty physicians who are 3-5 years post residency. At this point in time, said Dr. Alberti, the consensus among medical educators has been that physicians “need to be able to understand and consider [social, economic, and structural] contexts when they’re seeing patients, when they’re developing care plans, when they’re talking with caregivers, and when they’re looking at their own quality data.”

Elisabeth Poorman, MD, MPH, an internist at UW Medicine in Kent, Washington, said she worries that the passion of medical students for SDHs will too often be crushed, especially during residency and with immersion in the productivity-focused health care system. Studies show a drop in mental wellness and empathy and a rise in cynicism as training advances, said Dr. Poorman, who also writes about health care and issues of equity and serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

With similar concerns, the AMA has recently launched a “Reimagining Residency” initiative that aims to improve transitions from medical school to residency and the wellness of residents and faculty, and expand educational content relating to SDHs.

Dr. Fair is optimistic that new physicians’ knowledge of SDHs will permeate medical practices.

“Physicians who are out practicing are going to be working with our graduates, and they’re going to be asking in [job] interviews, do you have flexible hours for patients? What community partnerships do you have? Are there other professionals on staff to help us address social determinants of health? What data [relating to SDHs] are you collecting?” she said.

Correction, 8/26/2019: An earlier version of this story misstated the title of Aletha Maybank, MD. Dr. Maybank's correct title is the first chief health equity officer of the American Medical Association.

Fragmented, essentializing, simplistic. That’s how students at Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, described their required course on cultural competence. Lectures and discussions about cultural groups and communication issues weren’t providing them with the skills they needed to navigate doctor-patient relationships.

Their criticism was a wake-up call that Horace Delisser, MD, associate dean for diversity and inclusion at the school, took to heart. He enlisted medical students to help reinvent the curriculum. The result, Introduction to Medicine and Society, launched in 2013 and described in an article published in 2017 (Acad Med. 2017;92[3]:335-43), emphasizes self-awareness and reflection about one’s own biases and the adoption of a less hierarchical and more respectful “other-oriented” approach to the patient relationship.

The course examines social determinants of health (SDHs) – the influences of society, government, culture, and health systems. Students analyze how health and health outcomes are affected by a patient’s income, education, and living and working conditions, as well as access to healthy food, safe water, and transportation.

A host of policy makers, advisory groups, and organized medicine groups have called in recent years for educational efforts to boost all physicians’ working knowledge of health inequities and SDHs.

Dr. Delisser, associate professor of medicine who also practices as a pulmonologist at the Harron Lung Center in the Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine, said SDHs play into daily care.

Consider the patient who is chronically late for appointments. “It may not be an issue of the patient being disinterested in their health care, but maybe the public transportation system is unreliable, or maybe the patient has to take two buses and a subway to get there. I need [this knowledge] to inform my care and to engage my patient. I need to know, ‘what does it take for you to get here?’ That factors into how I [make the care plan],” said Dr. Delisser.

Malika Fair, MD, MPH, who teaches a longitudinal professional development class at George Washington University, Washington, and is senior director of health equity partnerships and programs at the American Association of Medical Colleges, provided the example of how her medical students intervened during their rotation in the emergency department on behalf of a newly-diagnosed patient with diabetes who had been unable to fill a prescribed medication. After determining where the patient lived, the students ensured that she had transportation and was able to get the needed medication at a local grocery store. They asked about her barriers to healthy eating, researched local grocery stores, and made practical recommendations that the patient was amenable to implementing. They identified a clinic closer to the patient’s home, and worked with her on making an appointment at a time when she could take off from work.

“Because of their training, these students were able to identify and address social risks in their first month on the ward,” said Dr. Fair, who also practices emergency medicine. They had learned about how to ask about food access and how safe it was for the patient to walk and exercise in her neighborhood.

At Perelman, most students work in student-led community clinics, and some fourth-year students participate in an elective rotation as apprentices to community health workers, learning to address SDHs and develop the cultural humility that they learned about in the classroom. The rotation was similarly created in 2013 and is described in a 2018 article (J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29[2]:581-90).“Being a good physician involves being technically competent as well as what I call relationally competent,” Dr. Delisser said. “And [this involves] being aware that my relationship with a patient doesn’t exist in a vacuum ... that there’s a bigger, broader social and structural context that I need to know and understand. I [then need] to use that to inform how I mediate and empower that relationship.”

Aletha Maybank, MD, who became the American Medical Association’s first chief health equity officer earlier this year, explained that “the medical profession had a very strong social context at one point in time,” but this was dampened by the Flexner Report of 1910.*

The report revolutionized medical education by increasing its rigor, but “it was really focused on clinical and basic science and took out the social context, the context of what medicine is about,” said Dr. Maybank, a pediatrician with a board certification in preventive medicine/public health. “[Now] we’re asking, how do we revolutionize medical education again at this point in time, recognizing the confluence of information and data that we now have available to us about inequities and disparities ... and the sense of urgency from students.”

Students driving practice change

Students nationally are “the most important” drivers of the increasing focus on SDHs in medical education, according to Dr. Fair. “They are demanding experiences to learn about the entire patient. We know that only 20% of a patient’s health is dependent on their health care. Our students are demanding education about the other 80%.”

More and more, communities are identifying needs and “students will then come up with initiatives to meet those needs,” Dr. Fair said.

Others interviewed for this story predicted this trend will only intensify, since not-for-profit hospitals are required under the Affordable Care Act regulations to assess community health needs every few years and to intervene accordingly.

Education on health care systems is also advancing. Penn State University, for instance, utilized a million-dollar grant from the AMA’s Accelerating Change in Medical Education initiative to design and implement a 4-year curriculum on the health system sciences that started in 2014. The curriculum includes an immersive experience in patient navigation.

“Students were taught to be patient navigators, and they were assigned within the clinical context to work on issues like, why are [patients] having trouble getting their medications?” said Susan E. Skochelak, MD, MPH, who leads the 6-year-old Accelerating Change initiative as vice president for medical education at the AMA.

From the start, she noted, students at Penn State are encouraged to question inequities, social and structural barriers to health, and faults in the health care system. “The message given at their white coat ceremony is ‘Welcome to medicine. Now that you’re here, you’re a member of the health care team, and we want you to speak up if you think there are things that need to be addressed. We want you to tell us when the system is working and not working,’ ” said Dr Skochelak, who previously served as the senior associate dean for academic affairs at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, where she had been a tenured professor of family medicine.

Tomorrow’s physician partners