User login

TAVR valves now FDA approved for low-risk patients

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication for the Sapien 3, Sapien 3 Ultra, CoreValve Evolut R, and CoreValve Evolut PRO transcatheter heart valves to include patients with severe aortic valve stenosis at low risk for death or major complications associated with open-heart surgery.

The announcement was based on results of a pair of clinical trials involving patients with severe aortic valve stenosis. In the first, 1,000 patients were randomly sorted to receive either transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) with the Edwards Lifescience’s Sapien 3 device or open-heart surgery. In the second, 1,468 patients received either Medtronic’s CoreValve Evolut R or CoreValve Evolut PRO or open heart surgery. In both studies, after an average follow-up time of 15-17 months, outcomes such as all-cause mortality and stroke were similar in patients who underwent open heart surgery and who received the transcatheter heart valve.

Serious adverse events associated with transcatheter heart valves include death, stroke, acute kidney injury, heart attack, bleeding, and the need for a permanent pacemaker. Patients who cannot tolerate blood-thinning medication or have an infection in the heart are contraindicated; in addition, the CoreValve devices should not be used in patients sensitive to titanium or nickel. Because the longevity of transcatheter heart valves, compared with open-heart surgery, has not been established, younger patients should discuss options with their health care provider.

“This new approval significantly expands the number of patients that can be treated with this less invasive procedure for aortic valve replacement and follows a thorough review of data demonstrating these devices are safe and effective for this larger population,” Bram Zuckerman, MD, director of the Office of Cardiovascular Devices in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication for the Sapien 3, Sapien 3 Ultra, CoreValve Evolut R, and CoreValve Evolut PRO transcatheter heart valves to include patients with severe aortic valve stenosis at low risk for death or major complications associated with open-heart surgery.

The announcement was based on results of a pair of clinical trials involving patients with severe aortic valve stenosis. In the first, 1,000 patients were randomly sorted to receive either transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) with the Edwards Lifescience’s Sapien 3 device or open-heart surgery. In the second, 1,468 patients received either Medtronic’s CoreValve Evolut R or CoreValve Evolut PRO or open heart surgery. In both studies, after an average follow-up time of 15-17 months, outcomes such as all-cause mortality and stroke were similar in patients who underwent open heart surgery and who received the transcatheter heart valve.

Serious adverse events associated with transcatheter heart valves include death, stroke, acute kidney injury, heart attack, bleeding, and the need for a permanent pacemaker. Patients who cannot tolerate blood-thinning medication or have an infection in the heart are contraindicated; in addition, the CoreValve devices should not be used in patients sensitive to titanium or nickel. Because the longevity of transcatheter heart valves, compared with open-heart surgery, has not been established, younger patients should discuss options with their health care provider.

“This new approval significantly expands the number of patients that can be treated with this less invasive procedure for aortic valve replacement and follows a thorough review of data demonstrating these devices are safe and effective for this larger population,” Bram Zuckerman, MD, director of the Office of Cardiovascular Devices in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication for the Sapien 3, Sapien 3 Ultra, CoreValve Evolut R, and CoreValve Evolut PRO transcatheter heart valves to include patients with severe aortic valve stenosis at low risk for death or major complications associated with open-heart surgery.

The announcement was based on results of a pair of clinical trials involving patients with severe aortic valve stenosis. In the first, 1,000 patients were randomly sorted to receive either transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) with the Edwards Lifescience’s Sapien 3 device or open-heart surgery. In the second, 1,468 patients received either Medtronic’s CoreValve Evolut R or CoreValve Evolut PRO or open heart surgery. In both studies, after an average follow-up time of 15-17 months, outcomes such as all-cause mortality and stroke were similar in patients who underwent open heart surgery and who received the transcatheter heart valve.

Serious adverse events associated with transcatheter heart valves include death, stroke, acute kidney injury, heart attack, bleeding, and the need for a permanent pacemaker. Patients who cannot tolerate blood-thinning medication or have an infection in the heart are contraindicated; in addition, the CoreValve devices should not be used in patients sensitive to titanium or nickel. Because the longevity of transcatheter heart valves, compared with open-heart surgery, has not been established, younger patients should discuss options with their health care provider.

“This new approval significantly expands the number of patients that can be treated with this less invasive procedure for aortic valve replacement and follows a thorough review of data demonstrating these devices are safe and effective for this larger population,” Bram Zuckerman, MD, director of the Office of Cardiovascular Devices in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

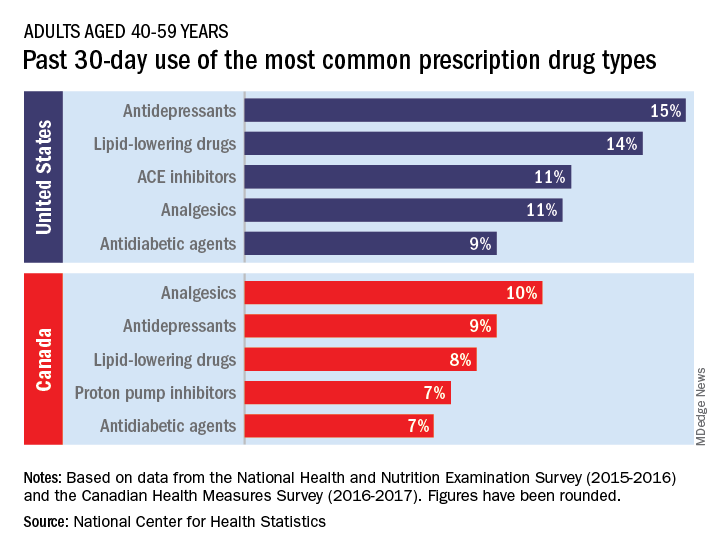

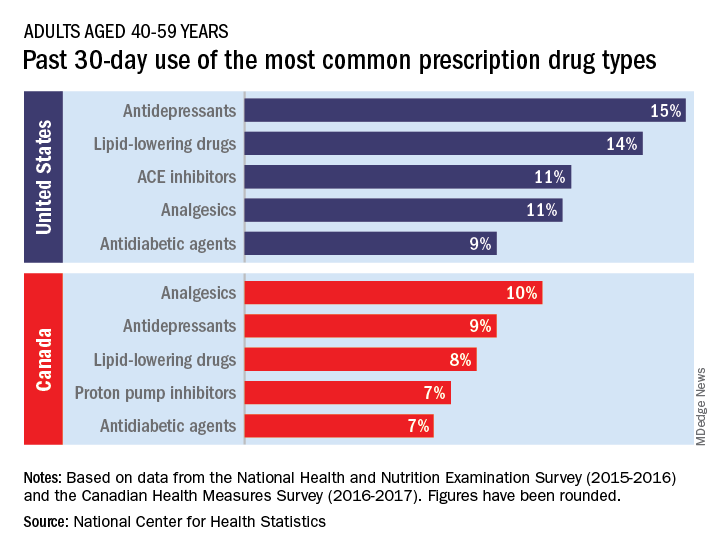

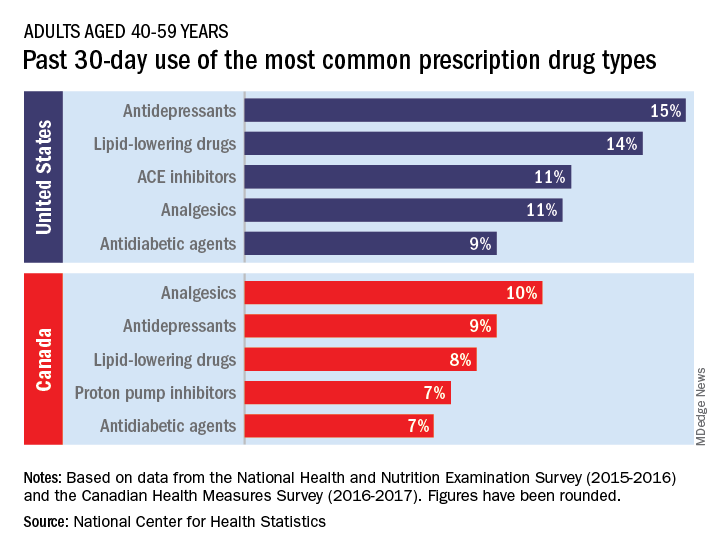

Prescription drug use varies between U.S. and Canada

The United States and Canada deliver health care in different ways, and patterns of prescription drug use also vary between the two countries, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The populations of the two countries, however, have similar age distributions – adults aged 40-79 years made up 44% of the population in the United States and 48% in Canada in 2016 – so “monitoring the use of prescription drugs provides insights into the health and health care of U.S. and Canadian adults,” the NCHS investigators wrote.

Data from the 2015-2016 National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey show that 15% of Americans aged 40-59 years had used antidepressants in the past 30 days, putting them ahead of lipid-lowering drugs (14%) and ACE inhibitors (11%), the NCHS said in a recent Data Brief.

Analgesics were the leading drug type in Canada, with 10% of adults aged 40-59 years reporting use in the past month, although that’s still lower than in the United States (11%), where they were fourth in popularity. The American top two were second and third among Canadians, while proton pump inhibitors were fourth in Canada but did not crack the top five in the United States, the NCHS reported based on 2016-2017 data from the Canadian Health Measures Survey.

Older adults (60-79 years) in the two countries managed to share some common ground: Lipid-lowering drugs were the most commonly used prescription medication both north and south of the border, although past 30-day use was considerably higher in the United States (45% vs. 34%), the NCHS investigators said.

There were differences to be found, however, in the older age group. Analgesics were the second most commonly used drug type in Canada but did not even reach the top five in the United States, while beta-blockers were third among Americans but missed the Canadian top five, they noted.

(60% vs. 53%) and to have used at least five such drugs (15% vs. 10%). The differences among adults aged 60-79 were not significant, although American use was higher for at least one drug (84% vs. 83%) and for at least five (35% vs. 31%), according to the report.

The United States and Canada deliver health care in different ways, and patterns of prescription drug use also vary between the two countries, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The populations of the two countries, however, have similar age distributions – adults aged 40-79 years made up 44% of the population in the United States and 48% in Canada in 2016 – so “monitoring the use of prescription drugs provides insights into the health and health care of U.S. and Canadian adults,” the NCHS investigators wrote.

Data from the 2015-2016 National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey show that 15% of Americans aged 40-59 years had used antidepressants in the past 30 days, putting them ahead of lipid-lowering drugs (14%) and ACE inhibitors (11%), the NCHS said in a recent Data Brief.

Analgesics were the leading drug type in Canada, with 10% of adults aged 40-59 years reporting use in the past month, although that’s still lower than in the United States (11%), where they were fourth in popularity. The American top two were second and third among Canadians, while proton pump inhibitors were fourth in Canada but did not crack the top five in the United States, the NCHS reported based on 2016-2017 data from the Canadian Health Measures Survey.

Older adults (60-79 years) in the two countries managed to share some common ground: Lipid-lowering drugs were the most commonly used prescription medication both north and south of the border, although past 30-day use was considerably higher in the United States (45% vs. 34%), the NCHS investigators said.

There were differences to be found, however, in the older age group. Analgesics were the second most commonly used drug type in Canada but did not even reach the top five in the United States, while beta-blockers were third among Americans but missed the Canadian top five, they noted.

(60% vs. 53%) and to have used at least five such drugs (15% vs. 10%). The differences among adults aged 60-79 were not significant, although American use was higher for at least one drug (84% vs. 83%) and for at least five (35% vs. 31%), according to the report.

The United States and Canada deliver health care in different ways, and patterns of prescription drug use also vary between the two countries, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The populations of the two countries, however, have similar age distributions – adults aged 40-79 years made up 44% of the population in the United States and 48% in Canada in 2016 – so “monitoring the use of prescription drugs provides insights into the health and health care of U.S. and Canadian adults,” the NCHS investigators wrote.

Data from the 2015-2016 National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey show that 15% of Americans aged 40-59 years had used antidepressants in the past 30 days, putting them ahead of lipid-lowering drugs (14%) and ACE inhibitors (11%), the NCHS said in a recent Data Brief.

Analgesics were the leading drug type in Canada, with 10% of adults aged 40-59 years reporting use in the past month, although that’s still lower than in the United States (11%), where they were fourth in popularity. The American top two were second and third among Canadians, while proton pump inhibitors were fourth in Canada but did not crack the top five in the United States, the NCHS reported based on 2016-2017 data from the Canadian Health Measures Survey.

Older adults (60-79 years) in the two countries managed to share some common ground: Lipid-lowering drugs were the most commonly used prescription medication both north and south of the border, although past 30-day use was considerably higher in the United States (45% vs. 34%), the NCHS investigators said.

There were differences to be found, however, in the older age group. Analgesics were the second most commonly used drug type in Canada but did not even reach the top five in the United States, while beta-blockers were third among Americans but missed the Canadian top five, they noted.

(60% vs. 53%) and to have used at least five such drugs (15% vs. 10%). The differences among adults aged 60-79 were not significant, although American use was higher for at least one drug (84% vs. 83%) and for at least five (35% vs. 31%), according to the report.

Is your office ready for a case of measles?

It’s a typically busy Friday and the doctor is running 20 minutes behind schedule. He enters the next exam room and the sight of the patient makes him forget the apology he had prepared.

The 10 month old looks miserable. Red eyes. Snot dripping from his nose. A red rash that extends from his face and involves most of the chest, arms, and upper thighs.

“When did this start?” he asks the mother as he searches for a surgical mask in the cabinet next to the exam table.

“Two days after we returned from our vacation in France,” the worried young woman replies. “Do you think it could be measles?”

Between Jan. 1 and Aug. 8, 2019, 1,182 cases of measles had been confirmed in the United States. That’s more than three times the number of cases reported in all of 2018, and the highest number of cases reported in a single year in more than a quarter century. While 75% of the cases this year have been linked to outbreaks in New York, individuals from 30 states have been affected.

Given the widespread nature of the outbreak, With measles in particular, time is limited to deliver effective postexposure prophylaxis and prevent the spread of measles in the community, making it difficult to develop a plan on the fly.

Schedule strategically. You don’t want a patient with measles hanging out in your waiting room. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, measures to prevent the transmission of contagious infectious agents in ambulatory facilities begin at the time the visit is scheduled. When there is measles transmission in the community, consider using a standardized script when scheduling patients that includes questions about fever, rash, other symptoms typical for measles, and possible exposures. Some offices will have procedures in place that can be adapted to care for patients with suspected measles. When a patient presents for suspected chicken pox, do you advise them to come at the end of the day to minimize exposures? Enter through a side door? Perform a car visit?

Triage promptly. Mask patients with fever and rash, move to a private room, and close the door.

Once measles is suspected, only health care personnel who are immune to measles should enter the exam room. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, presumptive evidence of measles immunity in health care providers is written documentation of vaccination with two doses of live measles or MMR vaccine administered at least 28 days apart, laboratory evidence of immunity (that is, positive measles IgG), laboratory confirmation of disease, or birth before 1957.

Even though health care providers born before 1957 are presumed to have had the disease at some point and have traditionally been considered immune, the CDC suggests that health care facilities consider giving these individuals two doses of MMR vaccine unless they have prior laboratory confirmation of disease immunity. Do you know who in your office is immune or would you need to scramble if you had an exposure?

When measles is suspected, health care personnel should wear an N-95 if they have been fit tested and the appropriate mask is available. Practically, most ambulatory offices do not stock N-95 masks and the next best choice is a regular surgical mask.

Order the recommended tests to confirm the diagnosis, but do not wait for the results to confirm the diagnosis. The CDC recommends testing serum for IgM antibodies and sending a throat or nasopharyngeal swab to look for the virus by polymerase chain reaction testing. Measles virus also is shed in the urine so collecting a urine specimen for testing may increase the chances of finding the virus. Depending on where you practice, the tests may take 3 days or more to result. Contact your local health department as soon as you consider a measles diagnosis.

Discharge patients home or transferred to a higher level of care if this is necessary as quickly as possible. Fortunately, most patients with measles do not require hospitalization. Do not send patients to the hospital simply for the purpose of laboratory testing if this can be accomplished quickly in your office or for evaluation by other providers. This just creates the potential for more exposures. If a patient does require higher-level care, provider-to-provider communication about the suspected diagnosis and the need for airborne isolation should take place.

Keep the door closed. Once a patient with suspected measles is discharged from a regular exam room, the door should remain closed, and it should not be used for at least 1 hour. Remember that infectious virus can remain in the air for 1-2 hours after a patient leaves an area. The same is true for the waiting room.

Develop the exposure list. In general, patients and family members who were in the waiting room at the same time as the index patient and up to 1-2 hours after the index patient left are considered exposed. Measles is highly contagious and 9 out of 10 susceptible people who are exposed will develop disease. How many infants aged less than 1 year might be in your waiting room at any given time? How many immunocompromised patients or family members? Public health authorities can help determine who needs prophylaxis.

Don’t get anxious and start testing everyone for measles, especially patients who lack typical signs and symptoms or exposures. Ordering a test in a patient who has a low likelihood of measles is more likely to result in a false-positive test than a true-positive test. False-positive measles IgM tests can be seen with some viral infections, including parvovirus and Epstein-Barr. Some rheumatologic disorders also can contribute to false-positive tests.

Review your office procedure for vaccine counseling. The 10 month old with measles in the opening vignette should have been given an MMR vaccine before travel. The vaccine is recommended for infants aged 6-11 months who are traveling outside the United States, but it doesn’t count toward the vaccine series. Reimmunize young travelers at 12-15 months and again at 4-6 years. The CDC has developed a toolkit that contains resources for taking to parents about vaccines. It is available at https://www.cdc.gov/measles/toolkit/healthcare-providers.html.

It’s a typically busy Friday and the doctor is running 20 minutes behind schedule. He enters the next exam room and the sight of the patient makes him forget the apology he had prepared.

The 10 month old looks miserable. Red eyes. Snot dripping from his nose. A red rash that extends from his face and involves most of the chest, arms, and upper thighs.

“When did this start?” he asks the mother as he searches for a surgical mask in the cabinet next to the exam table.

“Two days after we returned from our vacation in France,” the worried young woman replies. “Do you think it could be measles?”

Between Jan. 1 and Aug. 8, 2019, 1,182 cases of measles had been confirmed in the United States. That’s more than three times the number of cases reported in all of 2018, and the highest number of cases reported in a single year in more than a quarter century. While 75% of the cases this year have been linked to outbreaks in New York, individuals from 30 states have been affected.

Given the widespread nature of the outbreak, With measles in particular, time is limited to deliver effective postexposure prophylaxis and prevent the spread of measles in the community, making it difficult to develop a plan on the fly.

Schedule strategically. You don’t want a patient with measles hanging out in your waiting room. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, measures to prevent the transmission of contagious infectious agents in ambulatory facilities begin at the time the visit is scheduled. When there is measles transmission in the community, consider using a standardized script when scheduling patients that includes questions about fever, rash, other symptoms typical for measles, and possible exposures. Some offices will have procedures in place that can be adapted to care for patients with suspected measles. When a patient presents for suspected chicken pox, do you advise them to come at the end of the day to minimize exposures? Enter through a side door? Perform a car visit?

Triage promptly. Mask patients with fever and rash, move to a private room, and close the door.

Once measles is suspected, only health care personnel who are immune to measles should enter the exam room. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, presumptive evidence of measles immunity in health care providers is written documentation of vaccination with two doses of live measles or MMR vaccine administered at least 28 days apart, laboratory evidence of immunity (that is, positive measles IgG), laboratory confirmation of disease, or birth before 1957.

Even though health care providers born before 1957 are presumed to have had the disease at some point and have traditionally been considered immune, the CDC suggests that health care facilities consider giving these individuals two doses of MMR vaccine unless they have prior laboratory confirmation of disease immunity. Do you know who in your office is immune or would you need to scramble if you had an exposure?

When measles is suspected, health care personnel should wear an N-95 if they have been fit tested and the appropriate mask is available. Practically, most ambulatory offices do not stock N-95 masks and the next best choice is a regular surgical mask.

Order the recommended tests to confirm the diagnosis, but do not wait for the results to confirm the diagnosis. The CDC recommends testing serum for IgM antibodies and sending a throat or nasopharyngeal swab to look for the virus by polymerase chain reaction testing. Measles virus also is shed in the urine so collecting a urine specimen for testing may increase the chances of finding the virus. Depending on where you practice, the tests may take 3 days or more to result. Contact your local health department as soon as you consider a measles diagnosis.

Discharge patients home or transferred to a higher level of care if this is necessary as quickly as possible. Fortunately, most patients with measles do not require hospitalization. Do not send patients to the hospital simply for the purpose of laboratory testing if this can be accomplished quickly in your office or for evaluation by other providers. This just creates the potential for more exposures. If a patient does require higher-level care, provider-to-provider communication about the suspected diagnosis and the need for airborne isolation should take place.

Keep the door closed. Once a patient with suspected measles is discharged from a regular exam room, the door should remain closed, and it should not be used for at least 1 hour. Remember that infectious virus can remain in the air for 1-2 hours after a patient leaves an area. The same is true for the waiting room.

Develop the exposure list. In general, patients and family members who were in the waiting room at the same time as the index patient and up to 1-2 hours after the index patient left are considered exposed. Measles is highly contagious and 9 out of 10 susceptible people who are exposed will develop disease. How many infants aged less than 1 year might be in your waiting room at any given time? How many immunocompromised patients or family members? Public health authorities can help determine who needs prophylaxis.

Don’t get anxious and start testing everyone for measles, especially patients who lack typical signs and symptoms or exposures. Ordering a test in a patient who has a low likelihood of measles is more likely to result in a false-positive test than a true-positive test. False-positive measles IgM tests can be seen with some viral infections, including parvovirus and Epstein-Barr. Some rheumatologic disorders also can contribute to false-positive tests.

Review your office procedure for vaccine counseling. The 10 month old with measles in the opening vignette should have been given an MMR vaccine before travel. The vaccine is recommended for infants aged 6-11 months who are traveling outside the United States, but it doesn’t count toward the vaccine series. Reimmunize young travelers at 12-15 months and again at 4-6 years. The CDC has developed a toolkit that contains resources for taking to parents about vaccines. It is available at https://www.cdc.gov/measles/toolkit/healthcare-providers.html.

It’s a typically busy Friday and the doctor is running 20 minutes behind schedule. He enters the next exam room and the sight of the patient makes him forget the apology he had prepared.

The 10 month old looks miserable. Red eyes. Snot dripping from his nose. A red rash that extends from his face and involves most of the chest, arms, and upper thighs.

“When did this start?” he asks the mother as he searches for a surgical mask in the cabinet next to the exam table.

“Two days after we returned from our vacation in France,” the worried young woman replies. “Do you think it could be measles?”

Between Jan. 1 and Aug. 8, 2019, 1,182 cases of measles had been confirmed in the United States. That’s more than three times the number of cases reported in all of 2018, and the highest number of cases reported in a single year in more than a quarter century. While 75% of the cases this year have been linked to outbreaks in New York, individuals from 30 states have been affected.

Given the widespread nature of the outbreak, With measles in particular, time is limited to deliver effective postexposure prophylaxis and prevent the spread of measles in the community, making it difficult to develop a plan on the fly.

Schedule strategically. You don’t want a patient with measles hanging out in your waiting room. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, measures to prevent the transmission of contagious infectious agents in ambulatory facilities begin at the time the visit is scheduled. When there is measles transmission in the community, consider using a standardized script when scheduling patients that includes questions about fever, rash, other symptoms typical for measles, and possible exposures. Some offices will have procedures in place that can be adapted to care for patients with suspected measles. When a patient presents for suspected chicken pox, do you advise them to come at the end of the day to minimize exposures? Enter through a side door? Perform a car visit?

Triage promptly. Mask patients with fever and rash, move to a private room, and close the door.

Once measles is suspected, only health care personnel who are immune to measles should enter the exam room. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, presumptive evidence of measles immunity in health care providers is written documentation of vaccination with two doses of live measles or MMR vaccine administered at least 28 days apart, laboratory evidence of immunity (that is, positive measles IgG), laboratory confirmation of disease, or birth before 1957.

Even though health care providers born before 1957 are presumed to have had the disease at some point and have traditionally been considered immune, the CDC suggests that health care facilities consider giving these individuals two doses of MMR vaccine unless they have prior laboratory confirmation of disease immunity. Do you know who in your office is immune or would you need to scramble if you had an exposure?

When measles is suspected, health care personnel should wear an N-95 if they have been fit tested and the appropriate mask is available. Practically, most ambulatory offices do not stock N-95 masks and the next best choice is a regular surgical mask.

Order the recommended tests to confirm the diagnosis, but do not wait for the results to confirm the diagnosis. The CDC recommends testing serum for IgM antibodies and sending a throat or nasopharyngeal swab to look for the virus by polymerase chain reaction testing. Measles virus also is shed in the urine so collecting a urine specimen for testing may increase the chances of finding the virus. Depending on where you practice, the tests may take 3 days or more to result. Contact your local health department as soon as you consider a measles diagnosis.

Discharge patients home or transferred to a higher level of care if this is necessary as quickly as possible. Fortunately, most patients with measles do not require hospitalization. Do not send patients to the hospital simply for the purpose of laboratory testing if this can be accomplished quickly in your office or for evaluation by other providers. This just creates the potential for more exposures. If a patient does require higher-level care, provider-to-provider communication about the suspected diagnosis and the need for airborne isolation should take place.

Keep the door closed. Once a patient with suspected measles is discharged from a regular exam room, the door should remain closed, and it should not be used for at least 1 hour. Remember that infectious virus can remain in the air for 1-2 hours after a patient leaves an area. The same is true for the waiting room.

Develop the exposure list. In general, patients and family members who were in the waiting room at the same time as the index patient and up to 1-2 hours after the index patient left are considered exposed. Measles is highly contagious and 9 out of 10 susceptible people who are exposed will develop disease. How many infants aged less than 1 year might be in your waiting room at any given time? How many immunocompromised patients or family members? Public health authorities can help determine who needs prophylaxis.

Don’t get anxious and start testing everyone for measles, especially patients who lack typical signs and symptoms or exposures. Ordering a test in a patient who has a low likelihood of measles is more likely to result in a false-positive test than a true-positive test. False-positive measles IgM tests can be seen with some viral infections, including parvovirus and Epstein-Barr. Some rheumatologic disorders also can contribute to false-positive tests.

Review your office procedure for vaccine counseling. The 10 month old with measles in the opening vignette should have been given an MMR vaccine before travel. The vaccine is recommended for infants aged 6-11 months who are traveling outside the United States, but it doesn’t count toward the vaccine series. Reimmunize young travelers at 12-15 months and again at 4-6 years. The CDC has developed a toolkit that contains resources for taking to parents about vaccines. It is available at https://www.cdc.gov/measles/toolkit/healthcare-providers.html.

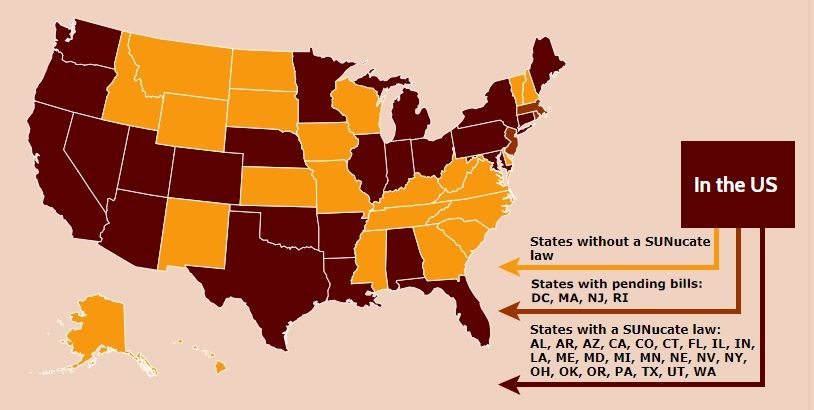

Nebraska issues SUNucate-based guidance for schools

Nebraska’s Department of Education recommended in a guidance that children be allowed to possess and use sunscreen products in school and at school-sponsored events, according to an Aug. 2 release from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The department’s guidance is based on model legislation developed by the SUNucate Coalition, which was created by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association and “works to address barriers to sunscreen use in school and camps and promote sun-safe behavior.” The coalition was created in 2016 because of reports that some U.S. schools had banned sunscreen products as part of broader medication bans because of these products’ classification as an over-the-counter medication.

Twenty-three other states have moved to lift such bans; these states were joined by Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Minnesota, Nevada, and now Nebraska in 2019 alone. The District of Columbia, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island are expected to follow suit.

Nebraska’s Department of Education recommended in a guidance that children be allowed to possess and use sunscreen products in school and at school-sponsored events, according to an Aug. 2 release from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The department’s guidance is based on model legislation developed by the SUNucate Coalition, which was created by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association and “works to address barriers to sunscreen use in school and camps and promote sun-safe behavior.” The coalition was created in 2016 because of reports that some U.S. schools had banned sunscreen products as part of broader medication bans because of these products’ classification as an over-the-counter medication.

Twenty-three other states have moved to lift such bans; these states were joined by Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Minnesota, Nevada, and now Nebraska in 2019 alone. The District of Columbia, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island are expected to follow suit.

Nebraska’s Department of Education recommended in a guidance that children be allowed to possess and use sunscreen products in school and at school-sponsored events, according to an Aug. 2 release from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The department’s guidance is based on model legislation developed by the SUNucate Coalition, which was created by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association and “works to address barriers to sunscreen use in school and camps and promote sun-safe behavior.” The coalition was created in 2016 because of reports that some U.S. schools had banned sunscreen products as part of broader medication bans because of these products’ classification as an over-the-counter medication.

Twenty-three other states have moved to lift such bans; these states were joined by Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Minnesota, Nevada, and now Nebraska in 2019 alone. The District of Columbia, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island are expected to follow suit.

Legal duty to nonpatients: Driving accidents

Question: Driver D strikes a pedestrian after losing control of his vehicle from insulin-induced hypoglycemia. Both Driver D and pedestrian were seriously injured. Driver D was recently diagnosed with diabetes, and his physician had started him on insulin, but did not warn of driving risks associated with hypoglycemia. The injured pedestrian is a total stranger to both Driver D and his doctor. Given these facts, which one of the following choices is correct?

A. Driver D can sue his doctor for failure to disclose hypoglycemic risk of insulin therapy under the doctrine of informed consent.

B. The pedestrian can sue Driver D for negligent driving.

C. The pedestrian may succeed in suing Driver D’s doctor for failure to warn of hypoglycemia.

D. The pedestrian’s lawsuit against Driver D’s doctor may fail in a jurisdiction that does not recognize a doctor’s legal duty to an unidentifiable, nonpatient third party.

E. All statements above are correct.

Answer: E. This legal duty grows out of the doctor-patient relationship, and is normally owed to the patient and to no one else. However, in limited circumstances, it may be extended to other individuals, so-called third parties, who may be total strangers. Injured nonpatient third parties from driving accidents have successfully sued doctors for failing to warn their patients that their medical conditions and/or medications can adversely affect driving ability.

Vizzoni v. Mulford-Dera is a New Jersey malpractice case that is currently before the state’s appellate court. The issue is whether Dr. Lerner, a psychiatrist, can be found negligent for the death of a bicyclist caused by the psychiatrist’s patient, Ms. Mulford-Dera, whose car struck and killed the cyclist. The decedent’s estate alleged that the physician should have warned the patient of the risks of driving while taking psychotropic medications. Dr. Lerner had been treating Ms. Mulford-Dera for psychological conditions, including major depression, panic disorder, and attention deficit disorder. As part of her treatment, Dr. Lerner prescribed several medications, allegedly without disclosing their potential adverse impact on driving. The trial court granted summary judgment and dismissed the case, ruling that the doctor owed no direct or indirect duty to the victim.

The case is currently on appeal. The AMA has filed an amicus brief in support of Dr. Lerner,1 pointing out that third-party claims had previously been rejected in New Jersey, where the injured victim is not readily identifiable. The brief emphasizes the folly of placing the physician or therapist in the untenable position of serving two potentially competing interests when a physician’s priority should be providing care to the patient. It referenced a similar case in Kansas, where a motorist who had fallen asleep at the wheel struck a bicyclist. The motorist was being treated by a neurologist for a sleep disorder.2 The Kansas Supreme Court held that there was no special relationship between the doctor and the cyclist that would impose a duty to warn the motorist about harming a third party.

Other jurisdictions have likewise rejected attempts at “derivative duties” in automobile accident cases. The Connecticut Supreme Court has ruled3 that doctors are immune from third party traffic accident lawsuits, as such litigation would detract from what’s best for the patient (“a physician’s desire to avoid lawsuits may result in far more restrictive advice than necessary for the patient’s well-being”). In that case, the defendant-gastroenterologist, Dr. Troncale, was treating a patient with hepatic encephalopathy and had not warned of the associated risk of driving. And an Illinois court dismissed a third party’s case against a hospital when one of its physicians fell asleep at the wheel after working excessive hours.4

In contrast, other jurisdictions have found a legal duty for physicians toward nonpatient victims. For example, in McKenzie v. Hawaii Permanente Medical Group,5 a car suddenly veered across five lanes of traffic, striking an 11-year-old girl and crushing her against a cement planter. The driver alleged that the prescription medication, Prazosin, caused him to lose control of the car, and that the treating physician was negligent, first in prescribing an inappropriate type and dose of medication, and second in failing to warn of potential side effects that could affect driving ability. The Hawaii Supreme Court emphasized that the risk of tort liability to an individual physician already discourages negligent prescribing; therefore, a physician does not have a duty to third parties where the alleged negligence involves prescribing decisions, i.e., whether to prescribe medication at all, which medication to prescribe, and what dosage to use. On the other hand, physicians have a duty to their patients to warn of potential adverse effects and this responsibility should therefore extend to third parties. Thus, liability would attach to injuries of innocent third parties as a result of failing to warn of a medication’s effects on driving—unless a reasonable person could be expected to be aware of this risk without the warning.

A foreseeable and unreasonable risk of harm is an important but not the only decisive factor in construing the existence of legal duty. Under some circumstances, the term “special relationship” has been employed based on a consideration of existing social values, customs, and policy considerations. In a Massachusetts case,6 a family physician had failed to warn his patient of the risk of diabetes drugs when operating a vehicle. Some 45 minutes after the patient’s discharge from the hospital, he developed hypoglycemia, losing consciousness and injuring a motorcyclist who then sued the doctor. The court invoked the “special relationship” rationale in ruling that the doctor owed a duty to the motorcyclist for public policy reasons.

Dr. Tan is professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu.

References

1. Vizzoni v. Mulford-Dera, In the Superior Court of New Jersey Appellate Division, Docket No. A-001255-18T3.

2. Calwell v. Hassan, 925 P.2d 422, 430 (Kan. 1996).

3. Jarmie v. Troncale, 50 A.3d 802 (Conn. 2012).

4. Brewster v. Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Med. Ctr., 836 N.E.2d 635 (Ill. Ct. App. 2005).

5. McKenzie v. Hawaii Permanente Medical Group, 47 P.3d 1209 (Haw. 2002).

6. Arsenault v. McConarty, 21 Mass. L. Rptr. 500 (2006).

Question: Driver D strikes a pedestrian after losing control of his vehicle from insulin-induced hypoglycemia. Both Driver D and pedestrian were seriously injured. Driver D was recently diagnosed with diabetes, and his physician had started him on insulin, but did not warn of driving risks associated with hypoglycemia. The injured pedestrian is a total stranger to both Driver D and his doctor. Given these facts, which one of the following choices is correct?

A. Driver D can sue his doctor for failure to disclose hypoglycemic risk of insulin therapy under the doctrine of informed consent.

B. The pedestrian can sue Driver D for negligent driving.

C. The pedestrian may succeed in suing Driver D’s doctor for failure to warn of hypoglycemia.

D. The pedestrian’s lawsuit against Driver D’s doctor may fail in a jurisdiction that does not recognize a doctor’s legal duty to an unidentifiable, nonpatient third party.

E. All statements above are correct.

Answer: E. This legal duty grows out of the doctor-patient relationship, and is normally owed to the patient and to no one else. However, in limited circumstances, it may be extended to other individuals, so-called third parties, who may be total strangers. Injured nonpatient third parties from driving accidents have successfully sued doctors for failing to warn their patients that their medical conditions and/or medications can adversely affect driving ability.

Vizzoni v. Mulford-Dera is a New Jersey malpractice case that is currently before the state’s appellate court. The issue is whether Dr. Lerner, a psychiatrist, can be found negligent for the death of a bicyclist caused by the psychiatrist’s patient, Ms. Mulford-Dera, whose car struck and killed the cyclist. The decedent’s estate alleged that the physician should have warned the patient of the risks of driving while taking psychotropic medications. Dr. Lerner had been treating Ms. Mulford-Dera for psychological conditions, including major depression, panic disorder, and attention deficit disorder. As part of her treatment, Dr. Lerner prescribed several medications, allegedly without disclosing their potential adverse impact on driving. The trial court granted summary judgment and dismissed the case, ruling that the doctor owed no direct or indirect duty to the victim.

The case is currently on appeal. The AMA has filed an amicus brief in support of Dr. Lerner,1 pointing out that third-party claims had previously been rejected in New Jersey, where the injured victim is not readily identifiable. The brief emphasizes the folly of placing the physician or therapist in the untenable position of serving two potentially competing interests when a physician’s priority should be providing care to the patient. It referenced a similar case in Kansas, where a motorist who had fallen asleep at the wheel struck a bicyclist. The motorist was being treated by a neurologist for a sleep disorder.2 The Kansas Supreme Court held that there was no special relationship between the doctor and the cyclist that would impose a duty to warn the motorist about harming a third party.

Other jurisdictions have likewise rejected attempts at “derivative duties” in automobile accident cases. The Connecticut Supreme Court has ruled3 that doctors are immune from third party traffic accident lawsuits, as such litigation would detract from what’s best for the patient (“a physician’s desire to avoid lawsuits may result in far more restrictive advice than necessary for the patient’s well-being”). In that case, the defendant-gastroenterologist, Dr. Troncale, was treating a patient with hepatic encephalopathy and had not warned of the associated risk of driving. And an Illinois court dismissed a third party’s case against a hospital when one of its physicians fell asleep at the wheel after working excessive hours.4

In contrast, other jurisdictions have found a legal duty for physicians toward nonpatient victims. For example, in McKenzie v. Hawaii Permanente Medical Group,5 a car suddenly veered across five lanes of traffic, striking an 11-year-old girl and crushing her against a cement planter. The driver alleged that the prescription medication, Prazosin, caused him to lose control of the car, and that the treating physician was negligent, first in prescribing an inappropriate type and dose of medication, and second in failing to warn of potential side effects that could affect driving ability. The Hawaii Supreme Court emphasized that the risk of tort liability to an individual physician already discourages negligent prescribing; therefore, a physician does not have a duty to third parties where the alleged negligence involves prescribing decisions, i.e., whether to prescribe medication at all, which medication to prescribe, and what dosage to use. On the other hand, physicians have a duty to their patients to warn of potential adverse effects and this responsibility should therefore extend to third parties. Thus, liability would attach to injuries of innocent third parties as a result of failing to warn of a medication’s effects on driving—unless a reasonable person could be expected to be aware of this risk without the warning.

A foreseeable and unreasonable risk of harm is an important but not the only decisive factor in construing the existence of legal duty. Under some circumstances, the term “special relationship” has been employed based on a consideration of existing social values, customs, and policy considerations. In a Massachusetts case,6 a family physician had failed to warn his patient of the risk of diabetes drugs when operating a vehicle. Some 45 minutes after the patient’s discharge from the hospital, he developed hypoglycemia, losing consciousness and injuring a motorcyclist who then sued the doctor. The court invoked the “special relationship” rationale in ruling that the doctor owed a duty to the motorcyclist for public policy reasons.

Dr. Tan is professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu.

References

1. Vizzoni v. Mulford-Dera, In the Superior Court of New Jersey Appellate Division, Docket No. A-001255-18T3.

2. Calwell v. Hassan, 925 P.2d 422, 430 (Kan. 1996).

3. Jarmie v. Troncale, 50 A.3d 802 (Conn. 2012).

4. Brewster v. Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Med. Ctr., 836 N.E.2d 635 (Ill. Ct. App. 2005).

5. McKenzie v. Hawaii Permanente Medical Group, 47 P.3d 1209 (Haw. 2002).

6. Arsenault v. McConarty, 21 Mass. L. Rptr. 500 (2006).

Question: Driver D strikes a pedestrian after losing control of his vehicle from insulin-induced hypoglycemia. Both Driver D and pedestrian were seriously injured. Driver D was recently diagnosed with diabetes, and his physician had started him on insulin, but did not warn of driving risks associated with hypoglycemia. The injured pedestrian is a total stranger to both Driver D and his doctor. Given these facts, which one of the following choices is correct?

A. Driver D can sue his doctor for failure to disclose hypoglycemic risk of insulin therapy under the doctrine of informed consent.

B. The pedestrian can sue Driver D for negligent driving.

C. The pedestrian may succeed in suing Driver D’s doctor for failure to warn of hypoglycemia.

D. The pedestrian’s lawsuit against Driver D’s doctor may fail in a jurisdiction that does not recognize a doctor’s legal duty to an unidentifiable, nonpatient third party.

E. All statements above are correct.

Answer: E. This legal duty grows out of the doctor-patient relationship, and is normally owed to the patient and to no one else. However, in limited circumstances, it may be extended to other individuals, so-called third parties, who may be total strangers. Injured nonpatient third parties from driving accidents have successfully sued doctors for failing to warn their patients that their medical conditions and/or medications can adversely affect driving ability.

Vizzoni v. Mulford-Dera is a New Jersey malpractice case that is currently before the state’s appellate court. The issue is whether Dr. Lerner, a psychiatrist, can be found negligent for the death of a bicyclist caused by the psychiatrist’s patient, Ms. Mulford-Dera, whose car struck and killed the cyclist. The decedent’s estate alleged that the physician should have warned the patient of the risks of driving while taking psychotropic medications. Dr. Lerner had been treating Ms. Mulford-Dera for psychological conditions, including major depression, panic disorder, and attention deficit disorder. As part of her treatment, Dr. Lerner prescribed several medications, allegedly without disclosing their potential adverse impact on driving. The trial court granted summary judgment and dismissed the case, ruling that the doctor owed no direct or indirect duty to the victim.

The case is currently on appeal. The AMA has filed an amicus brief in support of Dr. Lerner,1 pointing out that third-party claims had previously been rejected in New Jersey, where the injured victim is not readily identifiable. The brief emphasizes the folly of placing the physician or therapist in the untenable position of serving two potentially competing interests when a physician’s priority should be providing care to the patient. It referenced a similar case in Kansas, where a motorist who had fallen asleep at the wheel struck a bicyclist. The motorist was being treated by a neurologist for a sleep disorder.2 The Kansas Supreme Court held that there was no special relationship between the doctor and the cyclist that would impose a duty to warn the motorist about harming a third party.

Other jurisdictions have likewise rejected attempts at “derivative duties” in automobile accident cases. The Connecticut Supreme Court has ruled3 that doctors are immune from third party traffic accident lawsuits, as such litigation would detract from what’s best for the patient (“a physician’s desire to avoid lawsuits may result in far more restrictive advice than necessary for the patient’s well-being”). In that case, the defendant-gastroenterologist, Dr. Troncale, was treating a patient with hepatic encephalopathy and had not warned of the associated risk of driving. And an Illinois court dismissed a third party’s case against a hospital when one of its physicians fell asleep at the wheel after working excessive hours.4

In contrast, other jurisdictions have found a legal duty for physicians toward nonpatient victims. For example, in McKenzie v. Hawaii Permanente Medical Group,5 a car suddenly veered across five lanes of traffic, striking an 11-year-old girl and crushing her against a cement planter. The driver alleged that the prescription medication, Prazosin, caused him to lose control of the car, and that the treating physician was negligent, first in prescribing an inappropriate type and dose of medication, and second in failing to warn of potential side effects that could affect driving ability. The Hawaii Supreme Court emphasized that the risk of tort liability to an individual physician already discourages negligent prescribing; therefore, a physician does not have a duty to third parties where the alleged negligence involves prescribing decisions, i.e., whether to prescribe medication at all, which medication to prescribe, and what dosage to use. On the other hand, physicians have a duty to their patients to warn of potential adverse effects and this responsibility should therefore extend to third parties. Thus, liability would attach to injuries of innocent third parties as a result of failing to warn of a medication’s effects on driving—unless a reasonable person could be expected to be aware of this risk without the warning.

A foreseeable and unreasonable risk of harm is an important but not the only decisive factor in construing the existence of legal duty. Under some circumstances, the term “special relationship” has been employed based on a consideration of existing social values, customs, and policy considerations. In a Massachusetts case,6 a family physician had failed to warn his patient of the risk of diabetes drugs when operating a vehicle. Some 45 minutes after the patient’s discharge from the hospital, he developed hypoglycemia, losing consciousness and injuring a motorcyclist who then sued the doctor. The court invoked the “special relationship” rationale in ruling that the doctor owed a duty to the motorcyclist for public policy reasons.

Dr. Tan is professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu.

References

1. Vizzoni v. Mulford-Dera, In the Superior Court of New Jersey Appellate Division, Docket No. A-001255-18T3.

2. Calwell v. Hassan, 925 P.2d 422, 430 (Kan. 1996).

3. Jarmie v. Troncale, 50 A.3d 802 (Conn. 2012).

4. Brewster v. Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Med. Ctr., 836 N.E.2d 635 (Ill. Ct. App. 2005).

5. McKenzie v. Hawaii Permanente Medical Group, 47 P.3d 1209 (Haw. 2002).

6. Arsenault v. McConarty, 21 Mass. L. Rptr. 500 (2006).

‘Substantial burden’ of enterovirus meningitis in young infants

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A prospective international surveillance study has provided new insights into the surprisingly substantial clinical burden of viral meningitis caused by enteroviruses and human parechoviruses in young infants, Seilesh Kadambari, MBBS, PhD, said in his ESPID Young Investigator Award Lecture at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

This comprehensive study captured all cases of laboratory-confirmed enterovirus (EV) and human parechovirus (HPeV) meningitis in infants less than 90 days old seen by pediatricians in the United Kingdom and Ireland during a 13-month period starting in July 2014, a time free of outbreaks. Dr. Kadambari, a pediatrician at the University of Oxford (England), was first author of the study. It was for this project, as well as his earlier studies shedding light on congenital viral infections, that he received the Young Investigator honor.

Among the key findings of the U.K./Ireland surveillance study: The incidence of EV/HPeV meningitis was more than twice that of bacterial meningitis in the same age group and more than fivefold higher than that of group B streptococcal meningitis, the No. 1 cause of bacterial meningitis in early infancy. Moreover, more than one-half of infants with EV/HPeV meningitis had low levels of inflammatory markers and no cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis, which underscores the importance of routinely testing the cerebrospinal fluid for viral causes of meningitis in such patients using modern molecular tools such as multiplex polymerase chain reaction, according to Dr. Kadambari.

“Also, not a single one of the patients with EV/HPeV meningitis had a secondary bacterial infection – and that has important implications for management of our antibiotic stewardship programs,” he observed.

The study (Arch Dis Child. 2019 Jun;104(6):552-7) identified 668 cases of EV meningitis and 35 of HPeV meningitis, for an incidence of 0.79 and 0.04 per 1,000 live births, respectively. The most common clinical presentations were those generally seen in meningitis: fever, irritability, and reduced feeding. Circulatory shock was present in 43% of the infants with HPeV and 27% of the infants with EV infections.

Of infants with EV meningitis, 11% required admission to an intensive care unit, as did 23% of those with HPeV meningitis. Two babies with EV meningitis died and four others had continued neurologic complications at 12 months of follow-up. In contrast, all infants with HPeV survived without long-term sequelae.

Reassuringly, none of the 189 infants who underwent formal hearing testing had sensorineural hearing loss.

The surveillance study data have played an influential role in evidence-based guidelines for EV diagnosis and characterization published by the European Society of Clinical Virology (J Clin Virol. 2018 Apr;101:11-7).

An earlier study led by Dr. Kadambari documented a hefty sevenfold increase in the rate of laboratory-confirmed viral meningo-encephalitis in England and Wales during 2004-2013 across all age groups (J Infect. 2014 Oct;69[4]:326-32).

He attributed this increase to improved diagnosis of viral forms of meningitis through greater use of polymerase chain reaction. The study, based upon National Health Service hospital records, showed that more than 90% of all cases of viral meningo-encephalitis in infants less than 90 days old were caused by EV, a finding that prompted the subsequent prospective U.K./Ireland surveillance study.

Dr. Kadambari closed by noting the past decade had seen a greatly improved ability to diagnose congenital viral infections, but those improvements are not good enough.

“In the decade ahead, we hope to improve the management of this poorly understood group of infections,” the pediatrician promised.

Planned efforts include a cost-effectiveness analysis of a cytomegalovirus vaccine, an ESPID-funded research project aimed at identifying which EV/HPeV strains are most responsible for outbreaks and isolated severe disease, and gaining insight into the host-immunity factors associated with a proclivity to develop EV/HPeV meningitis in early infancy.

Dr. Kadambari reported having no financial conflicts regarding his studies, which was funded largely by Public Health England and university grants.

bjancin@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Kadambari S et al. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104:552-7.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A prospective international surveillance study has provided new insights into the surprisingly substantial clinical burden of viral meningitis caused by enteroviruses and human parechoviruses in young infants, Seilesh Kadambari, MBBS, PhD, said in his ESPID Young Investigator Award Lecture at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

This comprehensive study captured all cases of laboratory-confirmed enterovirus (EV) and human parechovirus (HPeV) meningitis in infants less than 90 days old seen by pediatricians in the United Kingdom and Ireland during a 13-month period starting in July 2014, a time free of outbreaks. Dr. Kadambari, a pediatrician at the University of Oxford (England), was first author of the study. It was for this project, as well as his earlier studies shedding light on congenital viral infections, that he received the Young Investigator honor.

Among the key findings of the U.K./Ireland surveillance study: The incidence of EV/HPeV meningitis was more than twice that of bacterial meningitis in the same age group and more than fivefold higher than that of group B streptococcal meningitis, the No. 1 cause of bacterial meningitis in early infancy. Moreover, more than one-half of infants with EV/HPeV meningitis had low levels of inflammatory markers and no cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis, which underscores the importance of routinely testing the cerebrospinal fluid for viral causes of meningitis in such patients using modern molecular tools such as multiplex polymerase chain reaction, according to Dr. Kadambari.

“Also, not a single one of the patients with EV/HPeV meningitis had a secondary bacterial infection – and that has important implications for management of our antibiotic stewardship programs,” he observed.

The study (Arch Dis Child. 2019 Jun;104(6):552-7) identified 668 cases of EV meningitis and 35 of HPeV meningitis, for an incidence of 0.79 and 0.04 per 1,000 live births, respectively. The most common clinical presentations were those generally seen in meningitis: fever, irritability, and reduced feeding. Circulatory shock was present in 43% of the infants with HPeV and 27% of the infants with EV infections.

Of infants with EV meningitis, 11% required admission to an intensive care unit, as did 23% of those with HPeV meningitis. Two babies with EV meningitis died and four others had continued neurologic complications at 12 months of follow-up. In contrast, all infants with HPeV survived without long-term sequelae.

Reassuringly, none of the 189 infants who underwent formal hearing testing had sensorineural hearing loss.

The surveillance study data have played an influential role in evidence-based guidelines for EV diagnosis and characterization published by the European Society of Clinical Virology (J Clin Virol. 2018 Apr;101:11-7).

An earlier study led by Dr. Kadambari documented a hefty sevenfold increase in the rate of laboratory-confirmed viral meningo-encephalitis in England and Wales during 2004-2013 across all age groups (J Infect. 2014 Oct;69[4]:326-32).

He attributed this increase to improved diagnosis of viral forms of meningitis through greater use of polymerase chain reaction. The study, based upon National Health Service hospital records, showed that more than 90% of all cases of viral meningo-encephalitis in infants less than 90 days old were caused by EV, a finding that prompted the subsequent prospective U.K./Ireland surveillance study.

Dr. Kadambari closed by noting the past decade had seen a greatly improved ability to diagnose congenital viral infections, but those improvements are not good enough.

“In the decade ahead, we hope to improve the management of this poorly understood group of infections,” the pediatrician promised.

Planned efforts include a cost-effectiveness analysis of a cytomegalovirus vaccine, an ESPID-funded research project aimed at identifying which EV/HPeV strains are most responsible for outbreaks and isolated severe disease, and gaining insight into the host-immunity factors associated with a proclivity to develop EV/HPeV meningitis in early infancy.

Dr. Kadambari reported having no financial conflicts regarding his studies, which was funded largely by Public Health England and university grants.

bjancin@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Kadambari S et al. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104:552-7.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A prospective international surveillance study has provided new insights into the surprisingly substantial clinical burden of viral meningitis caused by enteroviruses and human parechoviruses in young infants, Seilesh Kadambari, MBBS, PhD, said in his ESPID Young Investigator Award Lecture at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

This comprehensive study captured all cases of laboratory-confirmed enterovirus (EV) and human parechovirus (HPeV) meningitis in infants less than 90 days old seen by pediatricians in the United Kingdom and Ireland during a 13-month period starting in July 2014, a time free of outbreaks. Dr. Kadambari, a pediatrician at the University of Oxford (England), was first author of the study. It was for this project, as well as his earlier studies shedding light on congenital viral infections, that he received the Young Investigator honor.

Among the key findings of the U.K./Ireland surveillance study: The incidence of EV/HPeV meningitis was more than twice that of bacterial meningitis in the same age group and more than fivefold higher than that of group B streptococcal meningitis, the No. 1 cause of bacterial meningitis in early infancy. Moreover, more than one-half of infants with EV/HPeV meningitis had low levels of inflammatory markers and no cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis, which underscores the importance of routinely testing the cerebrospinal fluid for viral causes of meningitis in such patients using modern molecular tools such as multiplex polymerase chain reaction, according to Dr. Kadambari.

“Also, not a single one of the patients with EV/HPeV meningitis had a secondary bacterial infection – and that has important implications for management of our antibiotic stewardship programs,” he observed.

The study (Arch Dis Child. 2019 Jun;104(6):552-7) identified 668 cases of EV meningitis and 35 of HPeV meningitis, for an incidence of 0.79 and 0.04 per 1,000 live births, respectively. The most common clinical presentations were those generally seen in meningitis: fever, irritability, and reduced feeding. Circulatory shock was present in 43% of the infants with HPeV and 27% of the infants with EV infections.

Of infants with EV meningitis, 11% required admission to an intensive care unit, as did 23% of those with HPeV meningitis. Two babies with EV meningitis died and four others had continued neurologic complications at 12 months of follow-up. In contrast, all infants with HPeV survived without long-term sequelae.

Reassuringly, none of the 189 infants who underwent formal hearing testing had sensorineural hearing loss.

The surveillance study data have played an influential role in evidence-based guidelines for EV diagnosis and characterization published by the European Society of Clinical Virology (J Clin Virol. 2018 Apr;101:11-7).

An earlier study led by Dr. Kadambari documented a hefty sevenfold increase in the rate of laboratory-confirmed viral meningo-encephalitis in England and Wales during 2004-2013 across all age groups (J Infect. 2014 Oct;69[4]:326-32).

He attributed this increase to improved diagnosis of viral forms of meningitis through greater use of polymerase chain reaction. The study, based upon National Health Service hospital records, showed that more than 90% of all cases of viral meningo-encephalitis in infants less than 90 days old were caused by EV, a finding that prompted the subsequent prospective U.K./Ireland surveillance study.

Dr. Kadambari closed by noting the past decade had seen a greatly improved ability to diagnose congenital viral infections, but those improvements are not good enough.

“In the decade ahead, we hope to improve the management of this poorly understood group of infections,” the pediatrician promised.

Planned efforts include a cost-effectiveness analysis of a cytomegalovirus vaccine, an ESPID-funded research project aimed at identifying which EV/HPeV strains are most responsible for outbreaks and isolated severe disease, and gaining insight into the host-immunity factors associated with a proclivity to develop EV/HPeV meningitis in early infancy.

Dr. Kadambari reported having no financial conflicts regarding his studies, which was funded largely by Public Health England and university grants.

bjancin@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Kadambari S et al. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104:552-7.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

FDA approves fedratinib for myelofibrosis

The Food and Drug Administration has approved fedratinib (Inrebic), an oral JAK2/FLT3 inhibitor, to treat myelofibrosis.

Fedratinib is approved to treat adults with intermediate-2 or high-risk primary or secondary (post–polycythemia vera or post–essential thrombocythemia) myelofibrosis.

The prescribing information for fedratinib includes a boxed warning detailing the risk of serious and fatal encephalopathy, including Wernicke’s.

The encephalopathy risk prompted Sanofi to stop developing fedratinib in 2013. The FDA placed a clinical hold on all trials of fedratinib after potential cases of Wernicke’s encephalopathy were observed in eight patients.

The FDA lifted the clinical hold in 2017, and Celgene Corporation decided to develop fedratinib when the company acquired Impact Biomedicines in 2018.

In the phase 3 JAKARTA trial, fedratinib significantly reduced splenomegaly and symptom burden in patients with primary or secondary myelofibrosis (JAMA Oncol. 2015 Aug;1[5]:643-51). In the phase 2 JAKARTA2 trial, fedratinib produced responses in myelofibrosis patients previously treated with ruxolitinib (Lancet Haematol. 2017 Jul;4[7]:e317-e324).

Fedratinib received orphan drug designation from the FDA, and the application for fedratinib received priority review.

The FDA granted approval of fedratinib to Impact Biomedicines, a wholly owned subsidiary of Celgene.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved fedratinib (Inrebic), an oral JAK2/FLT3 inhibitor, to treat myelofibrosis.

Fedratinib is approved to treat adults with intermediate-2 or high-risk primary or secondary (post–polycythemia vera or post–essential thrombocythemia) myelofibrosis.

The prescribing information for fedratinib includes a boxed warning detailing the risk of serious and fatal encephalopathy, including Wernicke’s.

The encephalopathy risk prompted Sanofi to stop developing fedratinib in 2013. The FDA placed a clinical hold on all trials of fedratinib after potential cases of Wernicke’s encephalopathy were observed in eight patients.

The FDA lifted the clinical hold in 2017, and Celgene Corporation decided to develop fedratinib when the company acquired Impact Biomedicines in 2018.

In the phase 3 JAKARTA trial, fedratinib significantly reduced splenomegaly and symptom burden in patients with primary or secondary myelofibrosis (JAMA Oncol. 2015 Aug;1[5]:643-51). In the phase 2 JAKARTA2 trial, fedratinib produced responses in myelofibrosis patients previously treated with ruxolitinib (Lancet Haematol. 2017 Jul;4[7]:e317-e324).

Fedratinib received orphan drug designation from the FDA, and the application for fedratinib received priority review.

The FDA granted approval of fedratinib to Impact Biomedicines, a wholly owned subsidiary of Celgene.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved fedratinib (Inrebic), an oral JAK2/FLT3 inhibitor, to treat myelofibrosis.

Fedratinib is approved to treat adults with intermediate-2 or high-risk primary or secondary (post–polycythemia vera or post–essential thrombocythemia) myelofibrosis.

The prescribing information for fedratinib includes a boxed warning detailing the risk of serious and fatal encephalopathy, including Wernicke’s.

The encephalopathy risk prompted Sanofi to stop developing fedratinib in 2013. The FDA placed a clinical hold on all trials of fedratinib after potential cases of Wernicke’s encephalopathy were observed in eight patients.

The FDA lifted the clinical hold in 2017, and Celgene Corporation decided to develop fedratinib when the company acquired Impact Biomedicines in 2018.

In the phase 3 JAKARTA trial, fedratinib significantly reduced splenomegaly and symptom burden in patients with primary or secondary myelofibrosis (JAMA Oncol. 2015 Aug;1[5]:643-51). In the phase 2 JAKARTA2 trial, fedratinib produced responses in myelofibrosis patients previously treated with ruxolitinib (Lancet Haematol. 2017 Jul;4[7]:e317-e324).

Fedratinib received orphan drug designation from the FDA, and the application for fedratinib received priority review.

The FDA granted approval of fedratinib to Impact Biomedicines, a wholly owned subsidiary of Celgene.

Screening for pancreatic and lung cancers

In this edition of “How I will treat my next patient,” I examine the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement regarding screening for pancreatic cancer in normal-risk populations. I also review newly published information regarding low-dose CT screening (LDCT) for lung cancer in a commonly screened population – individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Both publications highlight the complexity of implementing shared decision making in clinicians’ efforts to find these highly lethal cancers in their earliest, most curable stages.

Pancreatic cancer screening

In their recommendation, the USPSTF considered data relevant to the benefits and harms (exclusive of costs) of screening for pancreatic cancer in the 85%-90% of individuals who are at normal risk because they lack a known familial or genetic syndrome and do not have at least two affected relatives or one first-degree affected relative (JAMA. 2019;322[5]:438-44).

After reviewing 13 cohort studies employing image-based technologies (CT, MRI, endoscopic ultrasound) and biomarkers for screening, the USPSTF reaffirmed its 2004 recommendation against pancreatic cancer screening. They found no new evidence of sufficient strength and quality to alter their previous “D grade” for screening (i.e., “Don’t do it.”). There were at least moderate harms of screening and subsequent treatment in normal-risk populations. These recommendations apply to asymptomatic individuals with new-onset diabetes mellitus, smokers, older adults, obese patients, and patients with a history of chronic pancreatitis.

What this means in practice

In the nicely written and comprehensive recommendation statement and in the two accompanying editorials (JAMA Surg. 2019 Aug 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.2832; JAMA. 2019;322[5]:407-8), the authors were explicit that the “D grade” for pancreatic cancer screening did not apply to individuals from familial pancreatic cancer kindreds and those with germline mutations and Lynch syndrome mismatch repair genes. For them, the relative risk of pancreatic cancer (greater than 5%) may justify the morbidity of available surveillance technologies, especially since U.S. and International screening studies in these high-risk individuals have generated data suggesting a benefit for treatment of screen-detected cancers.

The USPSTF and the editorial authors were strongly supportive of, and enthusiastic about, ongoing research efforts. Recently, a joint effort at the National Institutes of Health began recruiting centers for a study to assess the sensitivity of novel biomarkers in detecting pancreatic cancer among adults with new-onset diabetes (A211701).

To me, it is clear that the pathway to identifying effective screening for pancreatic cancer – which is forecast to become the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States by 2020 – will focus on high-risk populations first, enabling accurate determination of sensitivity and specificity before being applied to the general population. This is as it should be.

Lung cancer screening

Currently, guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend LDCT screening annually for high-risk smokers, former smokers, and individuals with additional risk factors aged 55-77 years. The National Lung Screening Trial indicated that LDCT screening achieved a 20% relative reduction in lung cancer mortality and 6.7% relative reduction in overall mortality in a similar population. NCCN guidelines stress the importance of shared decision making and include a table of risks and benefits that should be considered.

Jonathan M. Iaccarino, MD, and colleagues quantified the risks of screening among COPD patients in a secondary analysis of the more than 75,000 LDCT scans that were performed among the more than 26,000 participants in the National Lung Screening Trial (Chest 2019 Jul 5. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.06.016). In comparison with participants who did not self-report a diagnosis of COPD, the 4,632 participants with self-reported COPD were significantly more likely to require further diagnostic studies, have an invasive procedure, have a complication of any type from the invasive procedure, and suffer a serious complication. The establishment of a lung cancer diagnosis from the invasive procedure, however, occurred in just 6.1% of COPD patients versus 3.6% of patients without COPD.

What this means in practice

At a consensus conference convened by the National Quality Forum, shared decision making was defined as a process of communication in which clinicians and patients work together to make decisions that align with what matters most to patients. Ideally, shared decision making requires clear, accurate, unbiased medical evidence about reasonable alternatives; tailored evidence for individual patients; and the incorporation of patient values, goals, informed preferences and concerns, including a discussion of treatment burdens. All of us wrestle with the challenge of conducting these conversations in a comprehensive and unbiased manner. I am not sure that I have ever achieved an ideal shared decision-making conversation in my practice.

Despite the limitations acknowledged by the authors – self-reported diagnosis of COPD, outcomes that were not the primary focus of the trial, failure to incorporate other important comorbid conditions – the study by Dr. Iaccarino and colleagues helps to quantify risks and benefits for a commonly screened population, specifically COPD patients. Most importantly, it focuses our attention on the key goal of all cancer-screening efforts – applying our personal and technological resources to patients who benefit the most and will suffer the least harm from our efforts.

Dr. Lyss has been a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years, practicing in St. Louis. His clinical and research interests are in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of breast and lung cancers and in expanding access to clinical trials to medically underserved populations.

In this edition of “How I will treat my next patient,” I examine the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement regarding screening for pancreatic cancer in normal-risk populations. I also review newly published information regarding low-dose CT screening (LDCT) for lung cancer in a commonly screened population – individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Both publications highlight the complexity of implementing shared decision making in clinicians’ efforts to find these highly lethal cancers in their earliest, most curable stages.

Pancreatic cancer screening