User login

Treatment of Inpatient Asymptomatic Hypertension: Not a Call to Act but to Think

Your pager beeps. Your patient, Mrs. Jones, who was admitted with cellulitis and is improving, now has a blood pressure of 188/103 on routine vitals. Her nurse reports that she is comfortable and asymptomatic, but she met the “call parameters.” You review her chart and find that since admission her systolic blood pressure (SBP) has ranged from 149 to 157 mm Hg and her diastolic blood pressure (DBP) from 84 to 96 mm Hg. Her nurse asks how you would like to treat her.

While over half of inpatients have at least one hypertensive episode during their stay, evidence suggests that nearly all such episodes—estimates are between 98% and 99%1,2—should be treated over several days with oral antihypertensives, not acutely with intravenous medications.3-6 Current guidelines recommend that intravenous medications should be reserved for severe hypertensive episodes (SBP > 180, DBP > 120) with acute end-organ damage,7,8 but such “hypertensive emergencies” are rare on the general medicine wards. Still, hospitalists regularly face the dilemma posed by Mrs. Jones, and evidence shows they often prescribe intravenous antihypertensives.1,4,5 This unnecessary use can lead to unreliable drops in blood pressure and exposes our patients to potential harm.5,6

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, two papers describe the frequency of inappropriate intravenous antihypertensive use in their hospitals and the subsequent quality improvement efforts implemented to reduce this practice. The first, by Jacobs et al., found that over a 10-month period, 11% of patients who experienced “asymptomatic hypertension” on an urban academic hospital medicine service were treated inappropriately with intravenous antihypertensives,9 with 14% of those experiencing an adverse event. The second paper, by Pasik et al., found that in their urban academic medical center there were 8.3 inappropriate intravenous antihypertensive orders placed per 1,000 patient days,10 with nearly half of those treated experiencing an adverse event. Based on these findings, each group then led interventions to reduce the use of intravenous antihypertensives.

While both groups engaged physicians and nurses as primary stakeholders, Pasik et al.10 worked to further expand nursing staff roles by empowering them to assess for underlying causes of hypertension, such as pain or anxiety, as well as end-organ damage via specific guided algorithms prior to contacting physicians. In doing so, they reduced intravenous antihypertensive use by 60% during the postintervention period, with a proportional reduction in adverse events. In addition to their educational initiative, Jacobs et al. aimed to limit calls by liberalizing the “ceiling” on standard nursing call parameters for blood pressure from 160/80 to 180/90. Following their intervention, intravenous antihypertensive orders were reduced by 40%, with the mean orders per patient with asymptomatic hypertension decreasing from 11% to 7% .

While these results are admirable, some caution in their interpretation is needed. For example, Jacobs et al. used electronic health record data to retrospectively identify hypertension as “symptomatic” or “asymptomatic” using laboratory, electrocardiogram, and imaging diagnostics as surrogate markers for “provider concern for end-organ damage.” Although it appropriately focused on concern for end-organ damage as justification for intravenous antihypertensives, this approach potentially underappreciated true hypertensive emergencies, thereby overestimating the amount of inappropriate use of intravenous antihypertensives. Pasik et al. utilized chart review of patients prescribed intravenous antihypertensives and therefore did not explore how often symptomatic hypertension occurred in patients who did not receive intravenous antihypertensives. Subsequently, this limited their ability to evaluate unintended harms of their initiative. To address this limitation, the authors followed a group of 111 patients who had elevated hypertension but did not receive intravenous antihypertensives and found no adverse outcomes.10 Because both studies were retrospective in nature, they were subject to biases from providers choosing intravenous antihypertensives for reasons that were neither captured by their datasets nor adjusted for. Additionally, neither study reported downstream impacts such as an increase in symptomatic hypertensive episodes or more rare events such as kidney injury, stroke, or myocardial infarction.

Given that guidelines discourage using intravenous antihypertensives, why were the efforts of Jacobs et al.9 and Pasik et al.10 needed in the first place? In a recent installment of Choosing Wisely: Things We Do For No Reason, Breu et al.11 cite two primary reasons: first, providers have unfounded fears that asymptomatic hypertension will quickly progress to cause organ damage; second, providers lack understanding of the potential harms from overtreatment. It is fitting, therefore, that both groups of authors focused on these topics in their education initiatives for physicians and nurses. Yet, as good quality improvement requires steps beyond education, it was promising to see that both authors additionally focused on intervening to change the systems and culture that existed around physician and nursing communication.

In the age of electronic health records, there has been a sustained focus on creating standardized order sets. While the value of these order sets has been widely demonstrated, there are downsides. For example, nursing call parameters in admission order sets are rarely patient-specific but account for a significant portion of nursing and physician communication. These one-size-fits-all orders limit nurses from using their clinical training and create unnecessary tensions as nurses are obligated to call covering hospitalists to address “abnormal” but clinically insignificant findings. Regular monitoring of vital signs is an integral part of caring for acutely ill inpatients but for most inpatients, the importance of vitals is to detect clinically meaningful changes, not to treat risk factors like hypertension that should be treated safely over the long term.

When inpatients become febrile, tachycardic, or hypoxic, hospitalists use critical thinking to diagnose the underlying causes. Unfortunately, high blood pressure is a vital sign that is treated differently. Many hospitalists see it as a number to fix, not a potential sign of a new underlying problem such as uncontrolled pain, anxiety, or medication side effects.8 Both groups of authors took the important first step of educating physicians to think critically when called about high blood pressure. Even more importantly, they took steps to change the system and culture in which providers make these decisions in the first place. Future work in this area would be wise to follow in these footsteps, by encouraging collaboration between hospitalist and nurses to create more logical and patient-specific call parameters that could potentially improve nursing-physician communication, and subsequently, patient care.

Changing the culture to limit the use of intravenous antihypertensives will not be easy, but it is necessary. We encourage readers to investigate intravenous antihypertensives in their own hospitals and consider how better communication between nurses and physicians could change their practice. Recalling Mrs. Jones above, the provider should engage her nurse to help confirm that her hypertension is “asymptomatic” and then consider underlying causes such as pain, anxiety, or withholding her home medications as reasons for her elevated blood pressure. After all, if nothing else, it seems clear that a call about inpatient hypertension is not a call to act, but to think.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

Dr. Lucas is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development and Dartmouth SYNERGY, National Institutes of Health, National Center for Translational Science (UL1TR001086).

1. Axon RN, Cousineau L, Egan BM. Prevalence and management of hypertension in the inpatient setting: A systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(7):417- 422. doi: 10.1002/jhm.804. PubMed

2. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2011. 3.

3. Herzog E, Frankenberger O, Aziz E, et al. A novel pathway for the management of hypertension for hospitalized patients. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2007;6(4):150-160. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0b013e318160c3a7. PubMed

4. Weder AB, Erickson S. Treatment of hypertension in the inpatient setting: use of intravenous labetalol and hydralazine. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12(1):29-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00196.x. PubMed

5. Campbell P, Baker WL, Bendel SD, White WB. Intravenous hydralazine for blood pressure management in the hospitalized patient: its use is often unjustified. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5(6):473-477. doi: 10.1016/j. jash.2011.07.002. PubMed

6. Gaynor MF, Wright GC, Vondracek S. Retrospective review of the use of as-needed hydralazine and labetalol for the treatment of acute hypertension in hospitalized medicine patients. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;12(1):7-15. doi: 10.1177/1753944717746613. PubMed

7. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. PubMed

8. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1269-1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066. PubMed

9. Reducing Unnecessary Treatment of Asymptomatic Elevated Blood Pressure with Intravenous Medications on the General Internal Medicine Wards: A Quality Improvement Initiative. Jacobs ZG, Najafi N, Fang MC, et al. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:XXX-XXX. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3087. PubMed

10. Assess Before Rx: Reducing the Overtreatment of Asymptomatic Blood Pressure Elevation in the Inpatient Setting. Pasik SD, Chiu S, Yang J, et al. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:XXX-XXX. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3125. PubMed

11. Breu AC, Axon RN. Acute treatment of hypertensive urgency. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):860-862. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3086. PubMed

Your pager beeps. Your patient, Mrs. Jones, who was admitted with cellulitis and is improving, now has a blood pressure of 188/103 on routine vitals. Her nurse reports that she is comfortable and asymptomatic, but she met the “call parameters.” You review her chart and find that since admission her systolic blood pressure (SBP) has ranged from 149 to 157 mm Hg and her diastolic blood pressure (DBP) from 84 to 96 mm Hg. Her nurse asks how you would like to treat her.

While over half of inpatients have at least one hypertensive episode during their stay, evidence suggests that nearly all such episodes—estimates are between 98% and 99%1,2—should be treated over several days with oral antihypertensives, not acutely with intravenous medications.3-6 Current guidelines recommend that intravenous medications should be reserved for severe hypertensive episodes (SBP > 180, DBP > 120) with acute end-organ damage,7,8 but such “hypertensive emergencies” are rare on the general medicine wards. Still, hospitalists regularly face the dilemma posed by Mrs. Jones, and evidence shows they often prescribe intravenous antihypertensives.1,4,5 This unnecessary use can lead to unreliable drops in blood pressure and exposes our patients to potential harm.5,6

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, two papers describe the frequency of inappropriate intravenous antihypertensive use in their hospitals and the subsequent quality improvement efforts implemented to reduce this practice. The first, by Jacobs et al., found that over a 10-month period, 11% of patients who experienced “asymptomatic hypertension” on an urban academic hospital medicine service were treated inappropriately with intravenous antihypertensives,9 with 14% of those experiencing an adverse event. The second paper, by Pasik et al., found that in their urban academic medical center there were 8.3 inappropriate intravenous antihypertensive orders placed per 1,000 patient days,10 with nearly half of those treated experiencing an adverse event. Based on these findings, each group then led interventions to reduce the use of intravenous antihypertensives.

While both groups engaged physicians and nurses as primary stakeholders, Pasik et al.10 worked to further expand nursing staff roles by empowering them to assess for underlying causes of hypertension, such as pain or anxiety, as well as end-organ damage via specific guided algorithms prior to contacting physicians. In doing so, they reduced intravenous antihypertensive use by 60% during the postintervention period, with a proportional reduction in adverse events. In addition to their educational initiative, Jacobs et al. aimed to limit calls by liberalizing the “ceiling” on standard nursing call parameters for blood pressure from 160/80 to 180/90. Following their intervention, intravenous antihypertensive orders were reduced by 40%, with the mean orders per patient with asymptomatic hypertension decreasing from 11% to 7% .

While these results are admirable, some caution in their interpretation is needed. For example, Jacobs et al. used electronic health record data to retrospectively identify hypertension as “symptomatic” or “asymptomatic” using laboratory, electrocardiogram, and imaging diagnostics as surrogate markers for “provider concern for end-organ damage.” Although it appropriately focused on concern for end-organ damage as justification for intravenous antihypertensives, this approach potentially underappreciated true hypertensive emergencies, thereby overestimating the amount of inappropriate use of intravenous antihypertensives. Pasik et al. utilized chart review of patients prescribed intravenous antihypertensives and therefore did not explore how often symptomatic hypertension occurred in patients who did not receive intravenous antihypertensives. Subsequently, this limited their ability to evaluate unintended harms of their initiative. To address this limitation, the authors followed a group of 111 patients who had elevated hypertension but did not receive intravenous antihypertensives and found no adverse outcomes.10 Because both studies were retrospective in nature, they were subject to biases from providers choosing intravenous antihypertensives for reasons that were neither captured by their datasets nor adjusted for. Additionally, neither study reported downstream impacts such as an increase in symptomatic hypertensive episodes or more rare events such as kidney injury, stroke, or myocardial infarction.

Given that guidelines discourage using intravenous antihypertensives, why were the efforts of Jacobs et al.9 and Pasik et al.10 needed in the first place? In a recent installment of Choosing Wisely: Things We Do For No Reason, Breu et al.11 cite two primary reasons: first, providers have unfounded fears that asymptomatic hypertension will quickly progress to cause organ damage; second, providers lack understanding of the potential harms from overtreatment. It is fitting, therefore, that both groups of authors focused on these topics in their education initiatives for physicians and nurses. Yet, as good quality improvement requires steps beyond education, it was promising to see that both authors additionally focused on intervening to change the systems and culture that existed around physician and nursing communication.

In the age of electronic health records, there has been a sustained focus on creating standardized order sets. While the value of these order sets has been widely demonstrated, there are downsides. For example, nursing call parameters in admission order sets are rarely patient-specific but account for a significant portion of nursing and physician communication. These one-size-fits-all orders limit nurses from using their clinical training and create unnecessary tensions as nurses are obligated to call covering hospitalists to address “abnormal” but clinically insignificant findings. Regular monitoring of vital signs is an integral part of caring for acutely ill inpatients but for most inpatients, the importance of vitals is to detect clinically meaningful changes, not to treat risk factors like hypertension that should be treated safely over the long term.

When inpatients become febrile, tachycardic, or hypoxic, hospitalists use critical thinking to diagnose the underlying causes. Unfortunately, high blood pressure is a vital sign that is treated differently. Many hospitalists see it as a number to fix, not a potential sign of a new underlying problem such as uncontrolled pain, anxiety, or medication side effects.8 Both groups of authors took the important first step of educating physicians to think critically when called about high blood pressure. Even more importantly, they took steps to change the system and culture in which providers make these decisions in the first place. Future work in this area would be wise to follow in these footsteps, by encouraging collaboration between hospitalist and nurses to create more logical and patient-specific call parameters that could potentially improve nursing-physician communication, and subsequently, patient care.

Changing the culture to limit the use of intravenous antihypertensives will not be easy, but it is necessary. We encourage readers to investigate intravenous antihypertensives in their own hospitals and consider how better communication between nurses and physicians could change their practice. Recalling Mrs. Jones above, the provider should engage her nurse to help confirm that her hypertension is “asymptomatic” and then consider underlying causes such as pain, anxiety, or withholding her home medications as reasons for her elevated blood pressure. After all, if nothing else, it seems clear that a call about inpatient hypertension is not a call to act, but to think.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

Dr. Lucas is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development and Dartmouth SYNERGY, National Institutes of Health, National Center for Translational Science (UL1TR001086).

Your pager beeps. Your patient, Mrs. Jones, who was admitted with cellulitis and is improving, now has a blood pressure of 188/103 on routine vitals. Her nurse reports that she is comfortable and asymptomatic, but she met the “call parameters.” You review her chart and find that since admission her systolic blood pressure (SBP) has ranged from 149 to 157 mm Hg and her diastolic blood pressure (DBP) from 84 to 96 mm Hg. Her nurse asks how you would like to treat her.

While over half of inpatients have at least one hypertensive episode during their stay, evidence suggests that nearly all such episodes—estimates are between 98% and 99%1,2—should be treated over several days with oral antihypertensives, not acutely with intravenous medications.3-6 Current guidelines recommend that intravenous medications should be reserved for severe hypertensive episodes (SBP > 180, DBP > 120) with acute end-organ damage,7,8 but such “hypertensive emergencies” are rare on the general medicine wards. Still, hospitalists regularly face the dilemma posed by Mrs. Jones, and evidence shows they often prescribe intravenous antihypertensives.1,4,5 This unnecessary use can lead to unreliable drops in blood pressure and exposes our patients to potential harm.5,6

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, two papers describe the frequency of inappropriate intravenous antihypertensive use in their hospitals and the subsequent quality improvement efforts implemented to reduce this practice. The first, by Jacobs et al., found that over a 10-month period, 11% of patients who experienced “asymptomatic hypertension” on an urban academic hospital medicine service were treated inappropriately with intravenous antihypertensives,9 with 14% of those experiencing an adverse event. The second paper, by Pasik et al., found that in their urban academic medical center there were 8.3 inappropriate intravenous antihypertensive orders placed per 1,000 patient days,10 with nearly half of those treated experiencing an adverse event. Based on these findings, each group then led interventions to reduce the use of intravenous antihypertensives.

While both groups engaged physicians and nurses as primary stakeholders, Pasik et al.10 worked to further expand nursing staff roles by empowering them to assess for underlying causes of hypertension, such as pain or anxiety, as well as end-organ damage via specific guided algorithms prior to contacting physicians. In doing so, they reduced intravenous antihypertensive use by 60% during the postintervention period, with a proportional reduction in adverse events. In addition to their educational initiative, Jacobs et al. aimed to limit calls by liberalizing the “ceiling” on standard nursing call parameters for blood pressure from 160/80 to 180/90. Following their intervention, intravenous antihypertensive orders were reduced by 40%, with the mean orders per patient with asymptomatic hypertension decreasing from 11% to 7% .

While these results are admirable, some caution in their interpretation is needed. For example, Jacobs et al. used electronic health record data to retrospectively identify hypertension as “symptomatic” or “asymptomatic” using laboratory, electrocardiogram, and imaging diagnostics as surrogate markers for “provider concern for end-organ damage.” Although it appropriately focused on concern for end-organ damage as justification for intravenous antihypertensives, this approach potentially underappreciated true hypertensive emergencies, thereby overestimating the amount of inappropriate use of intravenous antihypertensives. Pasik et al. utilized chart review of patients prescribed intravenous antihypertensives and therefore did not explore how often symptomatic hypertension occurred in patients who did not receive intravenous antihypertensives. Subsequently, this limited their ability to evaluate unintended harms of their initiative. To address this limitation, the authors followed a group of 111 patients who had elevated hypertension but did not receive intravenous antihypertensives and found no adverse outcomes.10 Because both studies were retrospective in nature, they were subject to biases from providers choosing intravenous antihypertensives for reasons that were neither captured by their datasets nor adjusted for. Additionally, neither study reported downstream impacts such as an increase in symptomatic hypertensive episodes or more rare events such as kidney injury, stroke, or myocardial infarction.

Given that guidelines discourage using intravenous antihypertensives, why were the efforts of Jacobs et al.9 and Pasik et al.10 needed in the first place? In a recent installment of Choosing Wisely: Things We Do For No Reason, Breu et al.11 cite two primary reasons: first, providers have unfounded fears that asymptomatic hypertension will quickly progress to cause organ damage; second, providers lack understanding of the potential harms from overtreatment. It is fitting, therefore, that both groups of authors focused on these topics in their education initiatives for physicians and nurses. Yet, as good quality improvement requires steps beyond education, it was promising to see that both authors additionally focused on intervening to change the systems and culture that existed around physician and nursing communication.

In the age of electronic health records, there has been a sustained focus on creating standardized order sets. While the value of these order sets has been widely demonstrated, there are downsides. For example, nursing call parameters in admission order sets are rarely patient-specific but account for a significant portion of nursing and physician communication. These one-size-fits-all orders limit nurses from using their clinical training and create unnecessary tensions as nurses are obligated to call covering hospitalists to address “abnormal” but clinically insignificant findings. Regular monitoring of vital signs is an integral part of caring for acutely ill inpatients but for most inpatients, the importance of vitals is to detect clinically meaningful changes, not to treat risk factors like hypertension that should be treated safely over the long term.

When inpatients become febrile, tachycardic, or hypoxic, hospitalists use critical thinking to diagnose the underlying causes. Unfortunately, high blood pressure is a vital sign that is treated differently. Many hospitalists see it as a number to fix, not a potential sign of a new underlying problem such as uncontrolled pain, anxiety, or medication side effects.8 Both groups of authors took the important first step of educating physicians to think critically when called about high blood pressure. Even more importantly, they took steps to change the system and culture in which providers make these decisions in the first place. Future work in this area would be wise to follow in these footsteps, by encouraging collaboration between hospitalist and nurses to create more logical and patient-specific call parameters that could potentially improve nursing-physician communication, and subsequently, patient care.

Changing the culture to limit the use of intravenous antihypertensives will not be easy, but it is necessary. We encourage readers to investigate intravenous antihypertensives in their own hospitals and consider how better communication between nurses and physicians could change their practice. Recalling Mrs. Jones above, the provider should engage her nurse to help confirm that her hypertension is “asymptomatic” and then consider underlying causes such as pain, anxiety, or withholding her home medications as reasons for her elevated blood pressure. After all, if nothing else, it seems clear that a call about inpatient hypertension is not a call to act, but to think.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

Dr. Lucas is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development and Dartmouth SYNERGY, National Institutes of Health, National Center for Translational Science (UL1TR001086).

1. Axon RN, Cousineau L, Egan BM. Prevalence and management of hypertension in the inpatient setting: A systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(7):417- 422. doi: 10.1002/jhm.804. PubMed

2. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2011. 3.

3. Herzog E, Frankenberger O, Aziz E, et al. A novel pathway for the management of hypertension for hospitalized patients. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2007;6(4):150-160. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0b013e318160c3a7. PubMed

4. Weder AB, Erickson S. Treatment of hypertension in the inpatient setting: use of intravenous labetalol and hydralazine. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12(1):29-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00196.x. PubMed

5. Campbell P, Baker WL, Bendel SD, White WB. Intravenous hydralazine for blood pressure management in the hospitalized patient: its use is often unjustified. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5(6):473-477. doi: 10.1016/j. jash.2011.07.002. PubMed

6. Gaynor MF, Wright GC, Vondracek S. Retrospective review of the use of as-needed hydralazine and labetalol for the treatment of acute hypertension in hospitalized medicine patients. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;12(1):7-15. doi: 10.1177/1753944717746613. PubMed

7. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. PubMed

8. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1269-1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066. PubMed

9. Reducing Unnecessary Treatment of Asymptomatic Elevated Blood Pressure with Intravenous Medications on the General Internal Medicine Wards: A Quality Improvement Initiative. Jacobs ZG, Najafi N, Fang MC, et al. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:XXX-XXX. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3087. PubMed

10. Assess Before Rx: Reducing the Overtreatment of Asymptomatic Blood Pressure Elevation in the Inpatient Setting. Pasik SD, Chiu S, Yang J, et al. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:XXX-XXX. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3125. PubMed

11. Breu AC, Axon RN. Acute treatment of hypertensive urgency. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):860-862. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3086. PubMed

1. Axon RN, Cousineau L, Egan BM. Prevalence and management of hypertension in the inpatient setting: A systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(7):417- 422. doi: 10.1002/jhm.804. PubMed

2. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2011. 3.

3. Herzog E, Frankenberger O, Aziz E, et al. A novel pathway for the management of hypertension for hospitalized patients. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2007;6(4):150-160. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0b013e318160c3a7. PubMed

4. Weder AB, Erickson S. Treatment of hypertension in the inpatient setting: use of intravenous labetalol and hydralazine. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12(1):29-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00196.x. PubMed

5. Campbell P, Baker WL, Bendel SD, White WB. Intravenous hydralazine for blood pressure management in the hospitalized patient: its use is often unjustified. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5(6):473-477. doi: 10.1016/j. jash.2011.07.002. PubMed

6. Gaynor MF, Wright GC, Vondracek S. Retrospective review of the use of as-needed hydralazine and labetalol for the treatment of acute hypertension in hospitalized medicine patients. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;12(1):7-15. doi: 10.1177/1753944717746613. PubMed

7. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. PubMed

8. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1269-1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066. PubMed

9. Reducing Unnecessary Treatment of Asymptomatic Elevated Blood Pressure with Intravenous Medications on the General Internal Medicine Wards: A Quality Improvement Initiative. Jacobs ZG, Najafi N, Fang MC, et al. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:XXX-XXX. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3087. PubMed

10. Assess Before Rx: Reducing the Overtreatment of Asymptomatic Blood Pressure Elevation in the Inpatient Setting. Pasik SD, Chiu S, Yang J, et al. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:XXX-XXX. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3125. PubMed

11. Breu AC, Axon RN. Acute treatment of hypertensive urgency. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):860-862. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3086. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Adherence to Recommended Inpatient Hepatic Encephalopathy Workup

Clinical guidelines are periodically released by medical societies with the overarching goal of improving deliverable medical care by standardizing disease management according to best available published literature and by reducing healthcare expenditure associated with unnecessary and superfluous testing.1 Unfortunately, nonadherence to guidelines is common in clinical practice2 and contributes to the rising cost of healthcare.3 Health resource utilization is particularly relevant in management of cirrhosis, a condition with an annual healthcare expenditure of $13 billion.4 Hepatic encephalopathy (HE), the most common complication of cirrhosis, is characterized by altered sensorium and is the leading indication for hospitalization among cirrhotics. The joint guidelines of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) for diagnostic workup for HE recommend identification and treatment of potential precipitants.5 The guidelines also recommend against checking serum ammonia levels, which have not been shown to correlate with diagnosis or severity of HE.6-8 Currently, limited data are available on practice patterns regarding guideline adherence and unnecessary serum ammonia testing for initial evaluation of HE in hospitals. To overcome this gap in knowledge, we conducted the present study to provide granular details regarding the diagnostic workup for hospitalized patients with HE.

METHODS

This study adopted a retrospective design and recruited patients admitted to the Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center between July 1, 2016 and July 1, 2017. The institutional review board approved the study, and the manuscript was reviewed and approved by all authors prior to submission. All chart reviews were performed by hepatologists with access to patients’ electronic medical record (EMR).

Patient Population

Patients were identified from the EMR system by using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for cirrhosis, hepatic encephalopathy, and altered mental status. All consecutive admissions with these diagnosis codes were considered for inclusion. Adult patients with cirrhosis resulting from any etiology of chronic liver diseases with primary reason for admission of HE were included. If patients were readmitted for HE during the study period, then only the data from index HE admission was included in the analysis and data from subsequent admissions were excluded. The other exclusion criteria included non-HE causes of confusion, acute liver failure, and those admitted with a preformulated plan (eg, direct hepatology clinic admission or outside hospital transfer). Patients who developed HE during their hospitalization where HE was not the indication for admission were also excluded. Finally, all patients admitted under the direct care of hepatology were excluded.

Diagnostic Workup

The recommendations of the AASLD and the EASL for workup for HE include obtaining detailed history and physical examination supplemented by diagnostic evaluation for potential HE precipitants including infections, electrolyte disturbances, dehydration, renal failure, glycemic disturbances, and toxin ingestion (eg, alcohol, illicit drugs).5 Based on the guideline recommendation, this study defined a “complete workup” as including all of the following elements: infection evaluation (blood culture, urinalysis/urine culture, chest radiograph, diagnostic paracentesis in the presence of ascites), electrolyte/renal evaluation (serum sodium, potassium, creatinine, and glucose), and toxin evaluation (urine drug screening). Any HE admission that was missing elements from the aforementioned battery of tests was defined as “incomplete workup.” In patients admitted with decompensated cirrhosis, serum ammonia testing was considered inappropriate unless there was a nuanced explanation supporting its use documented within the EMR. The frequency and specialty of the physician ordering serum ammonia level tests were determined. The financial burden of unnecessary ammonia testing was estimated by assigning a laboratory charge ($258) for each patient.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous and categorical variables are reported as means (± standard deviation), median (interquartile range or IQR), or proportion (%) as appropriate. Across-group differences were compared using Student t-test for normally distributed continuous variables and Mann-Whitney U test for skewed data. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportion. HE evaluations were quantified by the number of patients with complete workup and by the number of patients with missing components of the workup. A nominal P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 24.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York).

RESULTS

Cohort Characteristics

The baseline cohort demographics are listed in the Table. Of the 145 patients identified using diagnostic codes for cirrhosis, 78 subjects met the study criteria. The most common exclusion criteria included non-HE etiology of altered mental status (n = 37) and patients with readmissions for HE during the study period (n = 30). The mean age of the study cohort was 59.3 years, and the most common etiology of cirrhosis was hepatitis C (n = 41), alcohol induced (n = 14), and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (n = 13).

Initial Diagnostic Evaluation

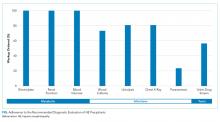

The major precipitants of HE in the study cohort were ineffective lactulose dosing (n = 43), infections (n = 25), and electrolyte disturbances/renal injury (n = 6). At the time of admission, 53 patients were on therapy for HE. Only 17 (22%) patients had complete diagnostic workup within 24 hours of hospital admission. The individual components of the complete workup are shown in the Figure. Notably, 23 (30%) patients were missing blood cultures, 16 (21%) were missing urinalysis, 15 (20%) were missing chest radiograph, and 34 (44%) were missing urine drug screening. Of the 34 patients with ascites on admission, only eight (23%) had diagnostic paracentesis performed on admission to rule out spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Serum Ammonia Testing

Serum ammonia testing was performed on 74 patients (94.9%), and no patient met the criteria for appropriate testing. Forty patients already had a known diagnosis of HE prior to index admission. Furthermore, 10 (14%) patients had serum ammonia testing repeated after admission without documentation in the EMR to justify repeat testing. Emergency Department (ED) physicians ordered ammonia testing in 57 cases (77%), internists ordered the testing in 11 cases (15%), and intensivists ordered the testing in two cases (3%). The patient’s charges for serum ammonia testing at the time of admission and for repeat testing were $19,092 and $2,580, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This study utilized HE in patients with decompensated cirrhosis as a framework to analyze adherence to societal guidelines. The adherence rate to AALSD/EASL recommended inpatient evaluation of HE is surprisingly low, and most patients are missing key essential elements of the diagnostic work up. While the diagnostic tests that are ordered as part of a panel are completed universally (renal function, electrolytes, and glucose testing), individual testing is less inclined to be ordered (blood cultures, urine culture/urinalysis, CXR, UDS) and procedural testing, such as diagnostic paracentesis, is often missed. This last finding is in line with published literature showing that 40% of patients admitted with ascites or HE did not have diagnostic paracentesis during hospital admission despite 24% reduction of inhospital mortality among patients undergoing the procedure.9

Although serum ammonia testing is not endorsed by the AASLD/EASL guidelines for HE,5 it is ordered nearly universally. The cost of an individual test is relatively low, but the cumulative cost of serum ammonia testing can be substantial because HE is the most common indication for hospitalization among patients with cirrhosis.4 Initiatives, such as the Choosing Wisely® campaign, encourage high-value and evidence-based care by limiting excessive and unnecessary diagnostic testing.10 The Canadian Choosing Wisely campaign specifically includes avoidance of serum ammonia testing for diagnosis of HE to provide high-value care in hepatology.11

Although the exact reasons for nonadherence to recommended HE evaluations are unclear, a potential method to mitigate excessive testing is to utilize the EMR and ordering system.3 EMR-based strategies can curb unnecessary testing in inpatient settings.12 The use of HE order sets, the inclusion of clinical decision support systems, and the restriction of access to specialized testing can be readily incorporated into the EMR to encourage adherence to guideline-based care while limiting unnecessary testing.

This study should be interpreted in the context of study limitations. Given the retrospective design of the study, salient factors in decisions behind diagnostic testing cannot be assessed. Future studies should utilize mixed-model methodology to elucidate reasons behind these decisions. The present study used a strict definition of complete workup including all the mentioned elements of the diagnostic workup for HE; however, in clinical practice, providers could be justified in not ordering certain tests if the specific clinical scenario does not lead to its use (eg, chest X-ray deferred in a patient with clear lung exam, no symptoms, or hypoxia). Similarly, UDS was included as a required element for a complete workup. While it may be ordered in a case-by-case basis to screen for illicit drug abuse, UDS is also a critical element of the workup to screen for opioid use as a precipitant of HE. Finally, considering the strict study entry criteria, we excluded repeated admissions for HE during the study period and therefore likely underestimate the cost burden of serum ammonia testing.

In conclusion, valuable guideline-based diagnostic testing is often missing in patients admitted for HE while serum ammonia testing is nearly universally ordered. These findings underscore the importance of implementing educational strategies, such as the Choosing Wisely® campaign, and EMR-based clinical decision support systems to improve health resource utilization in patients with cirrhosis and HE.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Andrews EJ, Redmond HP. A review of clinical guidelines. Br J Surg. 2004;91:956-964. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4630 PubMed

2. Arts DL, Voncken AG, Medlock S, Abu-Hanna A, van Weert HC. Reasons for intentional guideline non-adherence: a systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2016;89:55-62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.02.009. PubMed

3. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-1839. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152. PubMed

4. Everhart J. The burden of digestive diseases in the United States. Washington D.C.: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health. U.S. Government Printing Office; 2008:111-114.

5. Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology . 2014;60:715-735. doi: 10.1002/hep.27210 PubMed

6. Stahl J. Studies of the blood ammonia in liver disease: Its diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic significance. Ann Intern Med . 1963;58:1-24. PubMed

7. Ong JP, Aggarwal A, Kreiger D, et al. Correlation between ammonia levels and the severity of hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Med . 2003;114:188-193. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01477-8 PubMed

8. Nicalao F, Efrati C, Masini A, Merli M, Attili AF, Riggio O. Role of determination of partial pressure of ammonia in cirrhotic patients with and without hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2003;38:441-446. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00436-1 PubMed

9. Orman ES, Hayashi PH, Bataller R, Barritt AS 4th. Paracentesis is associated with reduced mortality in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and ascites. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:496-503. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.025. PubMed

10. Cassek CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307:1801-1802. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.476. PubMed

11. Choosing Wisely Canada. 2018. Five things patients and physicians should question. Available at: https://choosingwiselycanada.org/hepatology/ . Accessed November 18, 2018.

12. Iturrate E, Jubelt L, Volpicelli F, Hochman K. Optimize your electronic medical record to increase value: reducing laboratory overutilization. Am J Med . 2016;129:215-220. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.09.009. PubMed

Clinical guidelines are periodically released by medical societies with the overarching goal of improving deliverable medical care by standardizing disease management according to best available published literature and by reducing healthcare expenditure associated with unnecessary and superfluous testing.1 Unfortunately, nonadherence to guidelines is common in clinical practice2 and contributes to the rising cost of healthcare.3 Health resource utilization is particularly relevant in management of cirrhosis, a condition with an annual healthcare expenditure of $13 billion.4 Hepatic encephalopathy (HE), the most common complication of cirrhosis, is characterized by altered sensorium and is the leading indication for hospitalization among cirrhotics. The joint guidelines of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) for diagnostic workup for HE recommend identification and treatment of potential precipitants.5 The guidelines also recommend against checking serum ammonia levels, which have not been shown to correlate with diagnosis or severity of HE.6-8 Currently, limited data are available on practice patterns regarding guideline adherence and unnecessary serum ammonia testing for initial evaluation of HE in hospitals. To overcome this gap in knowledge, we conducted the present study to provide granular details regarding the diagnostic workup for hospitalized patients with HE.

METHODS

This study adopted a retrospective design and recruited patients admitted to the Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center between July 1, 2016 and July 1, 2017. The institutional review board approved the study, and the manuscript was reviewed and approved by all authors prior to submission. All chart reviews were performed by hepatologists with access to patients’ electronic medical record (EMR).

Patient Population

Patients were identified from the EMR system by using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for cirrhosis, hepatic encephalopathy, and altered mental status. All consecutive admissions with these diagnosis codes were considered for inclusion. Adult patients with cirrhosis resulting from any etiology of chronic liver diseases with primary reason for admission of HE were included. If patients were readmitted for HE during the study period, then only the data from index HE admission was included in the analysis and data from subsequent admissions were excluded. The other exclusion criteria included non-HE causes of confusion, acute liver failure, and those admitted with a preformulated plan (eg, direct hepatology clinic admission or outside hospital transfer). Patients who developed HE during their hospitalization where HE was not the indication for admission were also excluded. Finally, all patients admitted under the direct care of hepatology were excluded.

Diagnostic Workup

The recommendations of the AASLD and the EASL for workup for HE include obtaining detailed history and physical examination supplemented by diagnostic evaluation for potential HE precipitants including infections, electrolyte disturbances, dehydration, renal failure, glycemic disturbances, and toxin ingestion (eg, alcohol, illicit drugs).5 Based on the guideline recommendation, this study defined a “complete workup” as including all of the following elements: infection evaluation (blood culture, urinalysis/urine culture, chest radiograph, diagnostic paracentesis in the presence of ascites), electrolyte/renal evaluation (serum sodium, potassium, creatinine, and glucose), and toxin evaluation (urine drug screening). Any HE admission that was missing elements from the aforementioned battery of tests was defined as “incomplete workup.” In patients admitted with decompensated cirrhosis, serum ammonia testing was considered inappropriate unless there was a nuanced explanation supporting its use documented within the EMR. The frequency and specialty of the physician ordering serum ammonia level tests were determined. The financial burden of unnecessary ammonia testing was estimated by assigning a laboratory charge ($258) for each patient.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous and categorical variables are reported as means (± standard deviation), median (interquartile range or IQR), or proportion (%) as appropriate. Across-group differences were compared using Student t-test for normally distributed continuous variables and Mann-Whitney U test for skewed data. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportion. HE evaluations were quantified by the number of patients with complete workup and by the number of patients with missing components of the workup. A nominal P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 24.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York).

RESULTS

Cohort Characteristics

The baseline cohort demographics are listed in the Table. Of the 145 patients identified using diagnostic codes for cirrhosis, 78 subjects met the study criteria. The most common exclusion criteria included non-HE etiology of altered mental status (n = 37) and patients with readmissions for HE during the study period (n = 30). The mean age of the study cohort was 59.3 years, and the most common etiology of cirrhosis was hepatitis C (n = 41), alcohol induced (n = 14), and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (n = 13).

Initial Diagnostic Evaluation

The major precipitants of HE in the study cohort were ineffective lactulose dosing (n = 43), infections (n = 25), and electrolyte disturbances/renal injury (n = 6). At the time of admission, 53 patients were on therapy for HE. Only 17 (22%) patients had complete diagnostic workup within 24 hours of hospital admission. The individual components of the complete workup are shown in the Figure. Notably, 23 (30%) patients were missing blood cultures, 16 (21%) were missing urinalysis, 15 (20%) were missing chest radiograph, and 34 (44%) were missing urine drug screening. Of the 34 patients with ascites on admission, only eight (23%) had diagnostic paracentesis performed on admission to rule out spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Serum Ammonia Testing

Serum ammonia testing was performed on 74 patients (94.9%), and no patient met the criteria for appropriate testing. Forty patients already had a known diagnosis of HE prior to index admission. Furthermore, 10 (14%) patients had serum ammonia testing repeated after admission without documentation in the EMR to justify repeat testing. Emergency Department (ED) physicians ordered ammonia testing in 57 cases (77%), internists ordered the testing in 11 cases (15%), and intensivists ordered the testing in two cases (3%). The patient’s charges for serum ammonia testing at the time of admission and for repeat testing were $19,092 and $2,580, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This study utilized HE in patients with decompensated cirrhosis as a framework to analyze adherence to societal guidelines. The adherence rate to AALSD/EASL recommended inpatient evaluation of HE is surprisingly low, and most patients are missing key essential elements of the diagnostic work up. While the diagnostic tests that are ordered as part of a panel are completed universally (renal function, electrolytes, and glucose testing), individual testing is less inclined to be ordered (blood cultures, urine culture/urinalysis, CXR, UDS) and procedural testing, such as diagnostic paracentesis, is often missed. This last finding is in line with published literature showing that 40% of patients admitted with ascites or HE did not have diagnostic paracentesis during hospital admission despite 24% reduction of inhospital mortality among patients undergoing the procedure.9

Although serum ammonia testing is not endorsed by the AASLD/EASL guidelines for HE,5 it is ordered nearly universally. The cost of an individual test is relatively low, but the cumulative cost of serum ammonia testing can be substantial because HE is the most common indication for hospitalization among patients with cirrhosis.4 Initiatives, such as the Choosing Wisely® campaign, encourage high-value and evidence-based care by limiting excessive and unnecessary diagnostic testing.10 The Canadian Choosing Wisely campaign specifically includes avoidance of serum ammonia testing for diagnosis of HE to provide high-value care in hepatology.11

Although the exact reasons for nonadherence to recommended HE evaluations are unclear, a potential method to mitigate excessive testing is to utilize the EMR and ordering system.3 EMR-based strategies can curb unnecessary testing in inpatient settings.12 The use of HE order sets, the inclusion of clinical decision support systems, and the restriction of access to specialized testing can be readily incorporated into the EMR to encourage adherence to guideline-based care while limiting unnecessary testing.

This study should be interpreted in the context of study limitations. Given the retrospective design of the study, salient factors in decisions behind diagnostic testing cannot be assessed. Future studies should utilize mixed-model methodology to elucidate reasons behind these decisions. The present study used a strict definition of complete workup including all the mentioned elements of the diagnostic workup for HE; however, in clinical practice, providers could be justified in not ordering certain tests if the specific clinical scenario does not lead to its use (eg, chest X-ray deferred in a patient with clear lung exam, no symptoms, or hypoxia). Similarly, UDS was included as a required element for a complete workup. While it may be ordered in a case-by-case basis to screen for illicit drug abuse, UDS is also a critical element of the workup to screen for opioid use as a precipitant of HE. Finally, considering the strict study entry criteria, we excluded repeated admissions for HE during the study period and therefore likely underestimate the cost burden of serum ammonia testing.

In conclusion, valuable guideline-based diagnostic testing is often missing in patients admitted for HE while serum ammonia testing is nearly universally ordered. These findings underscore the importance of implementing educational strategies, such as the Choosing Wisely® campaign, and EMR-based clinical decision support systems to improve health resource utilization in patients with cirrhosis and HE.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Clinical guidelines are periodically released by medical societies with the overarching goal of improving deliverable medical care by standardizing disease management according to best available published literature and by reducing healthcare expenditure associated with unnecessary and superfluous testing.1 Unfortunately, nonadherence to guidelines is common in clinical practice2 and contributes to the rising cost of healthcare.3 Health resource utilization is particularly relevant in management of cirrhosis, a condition with an annual healthcare expenditure of $13 billion.4 Hepatic encephalopathy (HE), the most common complication of cirrhosis, is characterized by altered sensorium and is the leading indication for hospitalization among cirrhotics. The joint guidelines of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) for diagnostic workup for HE recommend identification and treatment of potential precipitants.5 The guidelines also recommend against checking serum ammonia levels, which have not been shown to correlate with diagnosis or severity of HE.6-8 Currently, limited data are available on practice patterns regarding guideline adherence and unnecessary serum ammonia testing for initial evaluation of HE in hospitals. To overcome this gap in knowledge, we conducted the present study to provide granular details regarding the diagnostic workup for hospitalized patients with HE.

METHODS

This study adopted a retrospective design and recruited patients admitted to the Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center between July 1, 2016 and July 1, 2017. The institutional review board approved the study, and the manuscript was reviewed and approved by all authors prior to submission. All chart reviews were performed by hepatologists with access to patients’ electronic medical record (EMR).

Patient Population

Patients were identified from the EMR system by using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for cirrhosis, hepatic encephalopathy, and altered mental status. All consecutive admissions with these diagnosis codes were considered for inclusion. Adult patients with cirrhosis resulting from any etiology of chronic liver diseases with primary reason for admission of HE were included. If patients were readmitted for HE during the study period, then only the data from index HE admission was included in the analysis and data from subsequent admissions were excluded. The other exclusion criteria included non-HE causes of confusion, acute liver failure, and those admitted with a preformulated plan (eg, direct hepatology clinic admission or outside hospital transfer). Patients who developed HE during their hospitalization where HE was not the indication for admission were also excluded. Finally, all patients admitted under the direct care of hepatology were excluded.

Diagnostic Workup

The recommendations of the AASLD and the EASL for workup for HE include obtaining detailed history and physical examination supplemented by diagnostic evaluation for potential HE precipitants including infections, electrolyte disturbances, dehydration, renal failure, glycemic disturbances, and toxin ingestion (eg, alcohol, illicit drugs).5 Based on the guideline recommendation, this study defined a “complete workup” as including all of the following elements: infection evaluation (blood culture, urinalysis/urine culture, chest radiograph, diagnostic paracentesis in the presence of ascites), electrolyte/renal evaluation (serum sodium, potassium, creatinine, and glucose), and toxin evaluation (urine drug screening). Any HE admission that was missing elements from the aforementioned battery of tests was defined as “incomplete workup.” In patients admitted with decompensated cirrhosis, serum ammonia testing was considered inappropriate unless there was a nuanced explanation supporting its use documented within the EMR. The frequency and specialty of the physician ordering serum ammonia level tests were determined. The financial burden of unnecessary ammonia testing was estimated by assigning a laboratory charge ($258) for each patient.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous and categorical variables are reported as means (± standard deviation), median (interquartile range or IQR), or proportion (%) as appropriate. Across-group differences were compared using Student t-test for normally distributed continuous variables and Mann-Whitney U test for skewed data. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportion. HE evaluations were quantified by the number of patients with complete workup and by the number of patients with missing components of the workup. A nominal P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 24.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York).

RESULTS

Cohort Characteristics

The baseline cohort demographics are listed in the Table. Of the 145 patients identified using diagnostic codes for cirrhosis, 78 subjects met the study criteria. The most common exclusion criteria included non-HE etiology of altered mental status (n = 37) and patients with readmissions for HE during the study period (n = 30). The mean age of the study cohort was 59.3 years, and the most common etiology of cirrhosis was hepatitis C (n = 41), alcohol induced (n = 14), and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (n = 13).

Initial Diagnostic Evaluation

The major precipitants of HE in the study cohort were ineffective lactulose dosing (n = 43), infections (n = 25), and electrolyte disturbances/renal injury (n = 6). At the time of admission, 53 patients were on therapy for HE. Only 17 (22%) patients had complete diagnostic workup within 24 hours of hospital admission. The individual components of the complete workup are shown in the Figure. Notably, 23 (30%) patients were missing blood cultures, 16 (21%) were missing urinalysis, 15 (20%) were missing chest radiograph, and 34 (44%) were missing urine drug screening. Of the 34 patients with ascites on admission, only eight (23%) had diagnostic paracentesis performed on admission to rule out spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Serum Ammonia Testing

Serum ammonia testing was performed on 74 patients (94.9%), and no patient met the criteria for appropriate testing. Forty patients already had a known diagnosis of HE prior to index admission. Furthermore, 10 (14%) patients had serum ammonia testing repeated after admission without documentation in the EMR to justify repeat testing. Emergency Department (ED) physicians ordered ammonia testing in 57 cases (77%), internists ordered the testing in 11 cases (15%), and intensivists ordered the testing in two cases (3%). The patient’s charges for serum ammonia testing at the time of admission and for repeat testing were $19,092 and $2,580, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This study utilized HE in patients with decompensated cirrhosis as a framework to analyze adherence to societal guidelines. The adherence rate to AALSD/EASL recommended inpatient evaluation of HE is surprisingly low, and most patients are missing key essential elements of the diagnostic work up. While the diagnostic tests that are ordered as part of a panel are completed universally (renal function, electrolytes, and glucose testing), individual testing is less inclined to be ordered (blood cultures, urine culture/urinalysis, CXR, UDS) and procedural testing, such as diagnostic paracentesis, is often missed. This last finding is in line with published literature showing that 40% of patients admitted with ascites or HE did not have diagnostic paracentesis during hospital admission despite 24% reduction of inhospital mortality among patients undergoing the procedure.9

Although serum ammonia testing is not endorsed by the AASLD/EASL guidelines for HE,5 it is ordered nearly universally. The cost of an individual test is relatively low, but the cumulative cost of serum ammonia testing can be substantial because HE is the most common indication for hospitalization among patients with cirrhosis.4 Initiatives, such as the Choosing Wisely® campaign, encourage high-value and evidence-based care by limiting excessive and unnecessary diagnostic testing.10 The Canadian Choosing Wisely campaign specifically includes avoidance of serum ammonia testing for diagnosis of HE to provide high-value care in hepatology.11

Although the exact reasons for nonadherence to recommended HE evaluations are unclear, a potential method to mitigate excessive testing is to utilize the EMR and ordering system.3 EMR-based strategies can curb unnecessary testing in inpatient settings.12 The use of HE order sets, the inclusion of clinical decision support systems, and the restriction of access to specialized testing can be readily incorporated into the EMR to encourage adherence to guideline-based care while limiting unnecessary testing.

This study should be interpreted in the context of study limitations. Given the retrospective design of the study, salient factors in decisions behind diagnostic testing cannot be assessed. Future studies should utilize mixed-model methodology to elucidate reasons behind these decisions. The present study used a strict definition of complete workup including all the mentioned elements of the diagnostic workup for HE; however, in clinical practice, providers could be justified in not ordering certain tests if the specific clinical scenario does not lead to its use (eg, chest X-ray deferred in a patient with clear lung exam, no symptoms, or hypoxia). Similarly, UDS was included as a required element for a complete workup. While it may be ordered in a case-by-case basis to screen for illicit drug abuse, UDS is also a critical element of the workup to screen for opioid use as a precipitant of HE. Finally, considering the strict study entry criteria, we excluded repeated admissions for HE during the study period and therefore likely underestimate the cost burden of serum ammonia testing.

In conclusion, valuable guideline-based diagnostic testing is often missing in patients admitted for HE while serum ammonia testing is nearly universally ordered. These findings underscore the importance of implementing educational strategies, such as the Choosing Wisely® campaign, and EMR-based clinical decision support systems to improve health resource utilization in patients with cirrhosis and HE.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Andrews EJ, Redmond HP. A review of clinical guidelines. Br J Surg. 2004;91:956-964. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4630 PubMed

2. Arts DL, Voncken AG, Medlock S, Abu-Hanna A, van Weert HC. Reasons for intentional guideline non-adherence: a systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2016;89:55-62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.02.009. PubMed

3. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-1839. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152. PubMed

4. Everhart J. The burden of digestive diseases in the United States. Washington D.C.: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health. U.S. Government Printing Office; 2008:111-114.

5. Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology . 2014;60:715-735. doi: 10.1002/hep.27210 PubMed

6. Stahl J. Studies of the blood ammonia in liver disease: Its diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic significance. Ann Intern Med . 1963;58:1-24. PubMed

7. Ong JP, Aggarwal A, Kreiger D, et al. Correlation between ammonia levels and the severity of hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Med . 2003;114:188-193. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01477-8 PubMed

8. Nicalao F, Efrati C, Masini A, Merli M, Attili AF, Riggio O. Role of determination of partial pressure of ammonia in cirrhotic patients with and without hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2003;38:441-446. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00436-1 PubMed

9. Orman ES, Hayashi PH, Bataller R, Barritt AS 4th. Paracentesis is associated with reduced mortality in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and ascites. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:496-503. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.025. PubMed

10. Cassek CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307:1801-1802. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.476. PubMed

11. Choosing Wisely Canada. 2018. Five things patients and physicians should question. Available at: https://choosingwiselycanada.org/hepatology/ . Accessed November 18, 2018.

12. Iturrate E, Jubelt L, Volpicelli F, Hochman K. Optimize your electronic medical record to increase value: reducing laboratory overutilization. Am J Med . 2016;129:215-220. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.09.009. PubMed

1. Andrews EJ, Redmond HP. A review of clinical guidelines. Br J Surg. 2004;91:956-964. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4630 PubMed

2. Arts DL, Voncken AG, Medlock S, Abu-Hanna A, van Weert HC. Reasons for intentional guideline non-adherence: a systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2016;89:55-62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.02.009. PubMed

3. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-1839. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152. PubMed

4. Everhart J. The burden of digestive diseases in the United States. Washington D.C.: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health. U.S. Government Printing Office; 2008:111-114.

5. Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology . 2014;60:715-735. doi: 10.1002/hep.27210 PubMed

6. Stahl J. Studies of the blood ammonia in liver disease: Its diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic significance. Ann Intern Med . 1963;58:1-24. PubMed

7. Ong JP, Aggarwal A, Kreiger D, et al. Correlation between ammonia levels and the severity of hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Med . 2003;114:188-193. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01477-8 PubMed

8. Nicalao F, Efrati C, Masini A, Merli M, Attili AF, Riggio O. Role of determination of partial pressure of ammonia in cirrhotic patients with and without hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2003;38:441-446. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00436-1 PubMed

9. Orman ES, Hayashi PH, Bataller R, Barritt AS 4th. Paracentesis is associated with reduced mortality in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and ascites. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:496-503. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.025. PubMed

10. Cassek CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307:1801-1802. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.476. PubMed

11. Choosing Wisely Canada. 2018. Five things patients and physicians should question. Available at: https://choosingwiselycanada.org/hepatology/ . Accessed November 18, 2018.

12. Iturrate E, Jubelt L, Volpicelli F, Hochman K. Optimize your electronic medical record to increase value: reducing laboratory overutilization. Am J Med . 2016;129:215-220. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.09.009. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Reviews Reenvisioned: Supporting Enhanced Practice Improvement for Hospitalists

As part of the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s® commitment to our readership, we are excited to announce innovative new review formats, designed for busy hospitalists. The state of knowledge in our field is changing rapidly, and the 21st century poses a conundrum to clinicians in the form of increasingly complex studies and guidelines amidst ever-decreasing time to digest them. As a result, it can be challenging for hospitalists to access and interpret recently published research to inform their clinical practice. Because we are committed to practical innovation for hospitalists, starting in 2019, JHM will offer focused yet informative content that places important advances into relevant clinical or methodological context and provides our readers with information that is accessible, meaningful, and actionable—all in a more concise format.

Our new Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist is a brief, targeted review of recently published clinical guidelines, distilling the major recommendations relevant to hospital medicine and placing them in context of the available evidence. This review format also offers a critique of gaps in the literature and notes areas ripe for future study. In this issue, we debut two articles using this new approach—one aimed at adult hospitalists and the other at pediatric hospitalists—regarding recently published studies and guidelines about maintenance intravenous fluids.1-5

In 2019, we will also introduce a second new format, called Progress Notes. These reviews will be shorter than JHM’s traditional review format, and will accept two types of articles: clinical and methodological. The clinical Progress Notes will provide an update on the last several years of evidence related to diagnosis, treatment, risk stratification, and/or prevention of a clinical problem highly pertinent to hospitalists. The methodological Progress Notes will provide our readers with insight into the application of quantitative, qualitative, and quality improvement methods commonly used in work published in this journal. Our aim is to use Progress Notes as a way to enhance both clinical practice and scholarship efforts by our readers.

Finally, we will introduce “Hospital Medicine: The Year in Review,” an annual feature that concisely compiles and critiques the top articles in both adult and pediatric hospital medicine over the past year. The “Year in Review” will serve as a written corollary to the popular “Updates in Hospital Medicine” presentation at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting, and will highlight important research that advanced our field or provided us a fresh perspective on hospitalist practice.

As we introduce these new review formats, it is important to note that JHM will continue to accept traditional, long-form reviews on any topic relevant to hospitalists, with a preference for rigorous systematic reviews or meta-analyses. Equally important is that JHM’s overarching commitment remains unchanged: support clinicians, leaders, and scholars in our field in their pursuit of delivering evidence-based, high-value clinical care. We hope you enjoy these new article formats and we look forward to your feedback.

Disclosures

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest/competing interests.

1. National Clinical Guideline Centre. Intravenous Fluid Therapy: Intravenous Fluid Therapy in Adults in Hospital. London: Royal College of Physicians (UK); 2013 Dec. PubMed

2. Selmer MW, Self WH, Wanderer JP, et al. Balanced Crystalloids versus Saline in Critically Ill Adults, N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 1;378(9):829-839. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711584. PubMed

3. Fled LG, et. al. “Clinical Practice Guideline: Maintenance Intravenous Fluids in Children,” Pediatrics. 2018 Dec;142(6). doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3083. PubMed

4. Gottenborg E, Pierce R. Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist: The Use of Intravenous Fluids in the Hospitalized Adult. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(3):172-173. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3178. PubMed

5. Girdwood ST, Parker MW, Shaughnessy EE. Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist: Maintenance Intravenous Fluids in Infants and Children. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(3):170-171. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3177. PubMed

As part of the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s® commitment to our readership, we are excited to announce innovative new review formats, designed for busy hospitalists. The state of knowledge in our field is changing rapidly, and the 21st century poses a conundrum to clinicians in the form of increasingly complex studies and guidelines amidst ever-decreasing time to digest them. As a result, it can be challenging for hospitalists to access and interpret recently published research to inform their clinical practice. Because we are committed to practical innovation for hospitalists, starting in 2019, JHM will offer focused yet informative content that places important advances into relevant clinical or methodological context and provides our readers with information that is accessible, meaningful, and actionable—all in a more concise format.

Our new Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist is a brief, targeted review of recently published clinical guidelines, distilling the major recommendations relevant to hospital medicine and placing them in context of the available evidence. This review format also offers a critique of gaps in the literature and notes areas ripe for future study. In this issue, we debut two articles using this new approach—one aimed at adult hospitalists and the other at pediatric hospitalists—regarding recently published studies and guidelines about maintenance intravenous fluids.1-5

In 2019, we will also introduce a second new format, called Progress Notes. These reviews will be shorter than JHM’s traditional review format, and will accept two types of articles: clinical and methodological. The clinical Progress Notes will provide an update on the last several years of evidence related to diagnosis, treatment, risk stratification, and/or prevention of a clinical problem highly pertinent to hospitalists. The methodological Progress Notes will provide our readers with insight into the application of quantitative, qualitative, and quality improvement methods commonly used in work published in this journal. Our aim is to use Progress Notes as a way to enhance both clinical practice and scholarship efforts by our readers.

Finally, we will introduce “Hospital Medicine: The Year in Review,” an annual feature that concisely compiles and critiques the top articles in both adult and pediatric hospital medicine over the past year. The “Year in Review” will serve as a written corollary to the popular “Updates in Hospital Medicine” presentation at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting, and will highlight important research that advanced our field or provided us a fresh perspective on hospitalist practice.

As we introduce these new review formats, it is important to note that JHM will continue to accept traditional, long-form reviews on any topic relevant to hospitalists, with a preference for rigorous systematic reviews or meta-analyses. Equally important is that JHM’s overarching commitment remains unchanged: support clinicians, leaders, and scholars in our field in their pursuit of delivering evidence-based, high-value clinical care. We hope you enjoy these new article formats and we look forward to your feedback.

Disclosures

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest/competing interests.