User login

New Frontiers in High-Value Care Education and Innovation: When Less is Not More

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine®, Drs. Arora and Moriates highlight an important deficiency in quality improvement efforts designed to reduce overuse of tests and treatments: the potential for trainees—and by extension, more seasoned clinicians—to rationalize minimizing under the guise of high-value care.1 This insightful perspective from the Co-Directors of Costs of Care should serve as a catalyst for further robust and effective care redesign efforts to optimize the use of all medical resources, including tests, treatments, procedures, consultations, emergency department (ED) visits, and hospital admissions. The formula to root out minimizers is not straightforward and requires an evaluation of wasteful practices in a nuanced and holistic manner that considers not only the frequency that the overused test (or treatment) is ordered but also the collateral impact of not ordering it. This principle has implications for measuring, paying for, and studying high-value care.

Overuse of tests and treatments increases costs and carries a risk of harm, from unnecessary use of creatine kinase–myocardial band (CK-MB) in suspected acute coronary syndrome2 to unwarranted administration of antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria3 to over-administration of blood transfusions.4 However, decreasing the use of a commonly ordered test is not always clinically appropriate. To illustrate this point, we consider the evidence-based algorithm to deliver best practice in the work-up of pulmonary embolism (PE) by Raja et al; which integrates pretest probability, PERC assessment, and appropriate use of D-dimer and pulmonary CT angiography (CTA).5 Avoiding D-dimer testing is appropriate in patients with very low pretest probability who pass a pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) clinical assessment and is also appropriate in patients who have sufficiently high clinical probability for PE to justify CTA regardless of a D-dimer result. On the other hand, avoiding D-dimer testing by attributing a patient’s symptoms to anxiety (as a minimizer might do) would increase patient risk, and could potentially increase cost if that patient ends up in intensive care after delayed diagnosis. Following diagnostic algorithms that include physician decision-making and evidence-based guidelines can prevent overuse and underuse, thereby maximizing efficiency and effectiveness. Engaging trainees in the development of such algorithms and decision support tools will serve to ingrain these principles into their practice.

Arora and Moriates highlight the importance of caring for a patient along a continuum rather than simply optimizing practice with respect to a single management decision or an isolated care episode. This approach is fundamental to the quality of care we provide, the public trust our profession still commands, and the total cost of care (TCOC). The two largest contributors to debilitating patient healthcare debt are not overuse of tests and treatments, but ED visits and hospitalizations.6 Thus, high-value quality improvement needs to anticipate future healthcare needs, including those that may result from delayed or missed diagnoses. Furthermore, excessive focus on the minutiae of high-value care (fewer daily basic metabolic panels) can lead to change fatigue and divert attention from higher impact utilization. We endorse a holistic approach in which the lens is shifted from the test—and even from the encounter or episode of care—to the entire continuum of care so that we can safeguard against inappropriate minimization. This approach has started to gain traction with policymakers. For example, the state of

Research is needed to guide best practice from this global perspective; as such, value improvement projects aimed at optimizing use of tests and treatments should include rigorous methodology, measures of downstream outcomes and costs, and balancing safety measures.8 For example, the ROMICAT II randomized trial evaluated two diagnostic approaches in emergency department patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome: early coronary computed tomography angiogram (CCTA) and standard ED evaluation.9 In addition to outcomes related to the ED visit itself, downstream testing and outcomes for 28 days after the episode were studied. In the acute setting, CCTA decreased time to diagnosis, reduced mean hospital length of stay by 7.6 hours, and resulted in 47% of patients being discharged within 8.6 hours as opposed to only 12% of the standard evaluation cohort. No cases of ACS were missed, and the CCTA cohort has slightly fewer cardiovascular adverse events (P = .18). However, the CCTA patients received significantly more diagnostic and functional testing and higher radiation exposure than the standard evaluation cohort, and underwent modestly higher rates of coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention. The TCOC over the 28-day period was similar at $4,289 for CCTA versus $4,060 for standard care (P = .65).9

Reducing the TCOC is imperative to protect patients from the burden of healthcare debt, but concerns have been raised about the ethics of high-value care if decision-making is driven by cost considerations.10 A recent viewpoint proposed a framework where high-value care recommendations are categorized as obligatory (protecting patients from harm), permissible (call for shared decision-making), or suspect (entirely cost-driven). By reframing care redesign as thoughtful, responsible care delivery, we can better incentivize physicians to exercise professionalism and maintain medical practice as a public trust.

High-value champions have a great deal of work ahead to redesign care to improve health, reduce TCOC, and investigate outcomes of care redesign. We applaud Drs. Arora and Moriates for once again leading the charge in preparing medical students and residents to deliver higher-value healthcare by emphasizing that effective patient care is not measured by a single episode or clinical decision, but is defined through a lifelong partnership between the patient and the healthcare system. As the country moves toward improved holistic models of care and financing, physician leadership in care redesign is essential to ensure that quality, safety, and patient well-being are not sacrificed at the altar of cost savings.

Disclosures

Dr. Johnson is a Consultant and Advisory Board Member at Oliver Wyman, receives salary support from an AHRQ grant, and has pending potential royalties from licensure of evidence-based appropriate use guidelines/criteria to AgilMD (Agile is a clinical decision support company). The other authors have no relevant disclosures. Dr. Johnson and Dr. Pahwa are Co-directors, High Value Practice Academic Alliance, www.hvpaa.org

1. Arora V, Moriates C. Tackling the minimizers behind high value care. J Hos Med. 2019: 14(5):318-319. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3104 PubMed

2. Alvin MD, Jaffe AS, Ziegelstein RC, Trost JC. Eliminating creatine kinase-myocardial band testing in suspected acute coronary syndrome: a value-based quality improvement. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1508-1512. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3597. PubMed

3. Daniel M, Keller S, Mozafarihashjin M, Pahwa A, Soong C. An implementation guide to reducing overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 018;178(2):271-276. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7290. PubMed

4. Sadana D, Pratzer A, Scher LJ, et al. Promoting high-value practice by reducing unnecessary transfusions with a patient blood management program. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(1):116-122. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6369. PubMed

5. Raja AS, Greenberg JO, Qaseem A, et al. Evaluation of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism: Best practice advice from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(9):701-711. doi: 10.7326/M14-1772 PubMed

6. The Burden of Medical Debt: Results from the Kaiser Family Foundation/New York Times Medical Bills Survey. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/report/the-burden-of-medical-debt-results-from-the-kaiser-family-foundationnew-york-times-medical-bills-survey/. Accessed December 2, 2018.

7. Maryland Total Cost of Care Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/md-tccm/. Accessed December 2, 2018

8. Grady D, Redberg RF, O’Malley PG. Quality improvement for quality improvement studies. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):187. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6875. PubMed

9. Hoffmann U, Truong QA, Schoenfeld DA, et al. Coronary CT angiography versus standard evaluation in acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:299-308. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201161. PubMed

10. DeCamp M, Tilburt JC. Ethics and high-value care. J Med Ethics. 2017;43(5):307-309. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103880. PubMed

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine®, Drs. Arora and Moriates highlight an important deficiency in quality improvement efforts designed to reduce overuse of tests and treatments: the potential for trainees—and by extension, more seasoned clinicians—to rationalize minimizing under the guise of high-value care.1 This insightful perspective from the Co-Directors of Costs of Care should serve as a catalyst for further robust and effective care redesign efforts to optimize the use of all medical resources, including tests, treatments, procedures, consultations, emergency department (ED) visits, and hospital admissions. The formula to root out minimizers is not straightforward and requires an evaluation of wasteful practices in a nuanced and holistic manner that considers not only the frequency that the overused test (or treatment) is ordered but also the collateral impact of not ordering it. This principle has implications for measuring, paying for, and studying high-value care.

Overuse of tests and treatments increases costs and carries a risk of harm, from unnecessary use of creatine kinase–myocardial band (CK-MB) in suspected acute coronary syndrome2 to unwarranted administration of antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria3 to over-administration of blood transfusions.4 However, decreasing the use of a commonly ordered test is not always clinically appropriate. To illustrate this point, we consider the evidence-based algorithm to deliver best practice in the work-up of pulmonary embolism (PE) by Raja et al; which integrates pretest probability, PERC assessment, and appropriate use of D-dimer and pulmonary CT angiography (CTA).5 Avoiding D-dimer testing is appropriate in patients with very low pretest probability who pass a pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) clinical assessment and is also appropriate in patients who have sufficiently high clinical probability for PE to justify CTA regardless of a D-dimer result. On the other hand, avoiding D-dimer testing by attributing a patient’s symptoms to anxiety (as a minimizer might do) would increase patient risk, and could potentially increase cost if that patient ends up in intensive care after delayed diagnosis. Following diagnostic algorithms that include physician decision-making and evidence-based guidelines can prevent overuse and underuse, thereby maximizing efficiency and effectiveness. Engaging trainees in the development of such algorithms and decision support tools will serve to ingrain these principles into their practice.

Arora and Moriates highlight the importance of caring for a patient along a continuum rather than simply optimizing practice with respect to a single management decision or an isolated care episode. This approach is fundamental to the quality of care we provide, the public trust our profession still commands, and the total cost of care (TCOC). The two largest contributors to debilitating patient healthcare debt are not overuse of tests and treatments, but ED visits and hospitalizations.6 Thus, high-value quality improvement needs to anticipate future healthcare needs, including those that may result from delayed or missed diagnoses. Furthermore, excessive focus on the minutiae of high-value care (fewer daily basic metabolic panels) can lead to change fatigue and divert attention from higher impact utilization. We endorse a holistic approach in which the lens is shifted from the test—and even from the encounter or episode of care—to the entire continuum of care so that we can safeguard against inappropriate minimization. This approach has started to gain traction with policymakers. For example, the state of

Research is needed to guide best practice from this global perspective; as such, value improvement projects aimed at optimizing use of tests and treatments should include rigorous methodology, measures of downstream outcomes and costs, and balancing safety measures.8 For example, the ROMICAT II randomized trial evaluated two diagnostic approaches in emergency department patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome: early coronary computed tomography angiogram (CCTA) and standard ED evaluation.9 In addition to outcomes related to the ED visit itself, downstream testing and outcomes for 28 days after the episode were studied. In the acute setting, CCTA decreased time to diagnosis, reduced mean hospital length of stay by 7.6 hours, and resulted in 47% of patients being discharged within 8.6 hours as opposed to only 12% of the standard evaluation cohort. No cases of ACS were missed, and the CCTA cohort has slightly fewer cardiovascular adverse events (P = .18). However, the CCTA patients received significantly more diagnostic and functional testing and higher radiation exposure than the standard evaluation cohort, and underwent modestly higher rates of coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention. The TCOC over the 28-day period was similar at $4,289 for CCTA versus $4,060 for standard care (P = .65).9

Reducing the TCOC is imperative to protect patients from the burden of healthcare debt, but concerns have been raised about the ethics of high-value care if decision-making is driven by cost considerations.10 A recent viewpoint proposed a framework where high-value care recommendations are categorized as obligatory (protecting patients from harm), permissible (call for shared decision-making), or suspect (entirely cost-driven). By reframing care redesign as thoughtful, responsible care delivery, we can better incentivize physicians to exercise professionalism and maintain medical practice as a public trust.

High-value champions have a great deal of work ahead to redesign care to improve health, reduce TCOC, and investigate outcomes of care redesign. We applaud Drs. Arora and Moriates for once again leading the charge in preparing medical students and residents to deliver higher-value healthcare by emphasizing that effective patient care is not measured by a single episode or clinical decision, but is defined through a lifelong partnership between the patient and the healthcare system. As the country moves toward improved holistic models of care and financing, physician leadership in care redesign is essential to ensure that quality, safety, and patient well-being are not sacrificed at the altar of cost savings.

Disclosures

Dr. Johnson is a Consultant and Advisory Board Member at Oliver Wyman, receives salary support from an AHRQ grant, and has pending potential royalties from licensure of evidence-based appropriate use guidelines/criteria to AgilMD (Agile is a clinical decision support company). The other authors have no relevant disclosures. Dr. Johnson and Dr. Pahwa are Co-directors, High Value Practice Academic Alliance, www.hvpaa.org

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine®, Drs. Arora and Moriates highlight an important deficiency in quality improvement efforts designed to reduce overuse of tests and treatments: the potential for trainees—and by extension, more seasoned clinicians—to rationalize minimizing under the guise of high-value care.1 This insightful perspective from the Co-Directors of Costs of Care should serve as a catalyst for further robust and effective care redesign efforts to optimize the use of all medical resources, including tests, treatments, procedures, consultations, emergency department (ED) visits, and hospital admissions. The formula to root out minimizers is not straightforward and requires an evaluation of wasteful practices in a nuanced and holistic manner that considers not only the frequency that the overused test (or treatment) is ordered but also the collateral impact of not ordering it. This principle has implications for measuring, paying for, and studying high-value care.

Overuse of tests and treatments increases costs and carries a risk of harm, from unnecessary use of creatine kinase–myocardial band (CK-MB) in suspected acute coronary syndrome2 to unwarranted administration of antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria3 to over-administration of blood transfusions.4 However, decreasing the use of a commonly ordered test is not always clinically appropriate. To illustrate this point, we consider the evidence-based algorithm to deliver best practice in the work-up of pulmonary embolism (PE) by Raja et al; which integrates pretest probability, PERC assessment, and appropriate use of D-dimer and pulmonary CT angiography (CTA).5 Avoiding D-dimer testing is appropriate in patients with very low pretest probability who pass a pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) clinical assessment and is also appropriate in patients who have sufficiently high clinical probability for PE to justify CTA regardless of a D-dimer result. On the other hand, avoiding D-dimer testing by attributing a patient’s symptoms to anxiety (as a minimizer might do) would increase patient risk, and could potentially increase cost if that patient ends up in intensive care after delayed diagnosis. Following diagnostic algorithms that include physician decision-making and evidence-based guidelines can prevent overuse and underuse, thereby maximizing efficiency and effectiveness. Engaging trainees in the development of such algorithms and decision support tools will serve to ingrain these principles into their practice.

Arora and Moriates highlight the importance of caring for a patient along a continuum rather than simply optimizing practice with respect to a single management decision or an isolated care episode. This approach is fundamental to the quality of care we provide, the public trust our profession still commands, and the total cost of care (TCOC). The two largest contributors to debilitating patient healthcare debt are not overuse of tests and treatments, but ED visits and hospitalizations.6 Thus, high-value quality improvement needs to anticipate future healthcare needs, including those that may result from delayed or missed diagnoses. Furthermore, excessive focus on the minutiae of high-value care (fewer daily basic metabolic panels) can lead to change fatigue and divert attention from higher impact utilization. We endorse a holistic approach in which the lens is shifted from the test—and even from the encounter or episode of care—to the entire continuum of care so that we can safeguard against inappropriate minimization. This approach has started to gain traction with policymakers. For example, the state of

Research is needed to guide best practice from this global perspective; as such, value improvement projects aimed at optimizing use of tests and treatments should include rigorous methodology, measures of downstream outcomes and costs, and balancing safety measures.8 For example, the ROMICAT II randomized trial evaluated two diagnostic approaches in emergency department patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome: early coronary computed tomography angiogram (CCTA) and standard ED evaluation.9 In addition to outcomes related to the ED visit itself, downstream testing and outcomes for 28 days after the episode were studied. In the acute setting, CCTA decreased time to diagnosis, reduced mean hospital length of stay by 7.6 hours, and resulted in 47% of patients being discharged within 8.6 hours as opposed to only 12% of the standard evaluation cohort. No cases of ACS were missed, and the CCTA cohort has slightly fewer cardiovascular adverse events (P = .18). However, the CCTA patients received significantly more diagnostic and functional testing and higher radiation exposure than the standard evaluation cohort, and underwent modestly higher rates of coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention. The TCOC over the 28-day period was similar at $4,289 for CCTA versus $4,060 for standard care (P = .65).9

Reducing the TCOC is imperative to protect patients from the burden of healthcare debt, but concerns have been raised about the ethics of high-value care if decision-making is driven by cost considerations.10 A recent viewpoint proposed a framework where high-value care recommendations are categorized as obligatory (protecting patients from harm), permissible (call for shared decision-making), or suspect (entirely cost-driven). By reframing care redesign as thoughtful, responsible care delivery, we can better incentivize physicians to exercise professionalism and maintain medical practice as a public trust.

High-value champions have a great deal of work ahead to redesign care to improve health, reduce TCOC, and investigate outcomes of care redesign. We applaud Drs. Arora and Moriates for once again leading the charge in preparing medical students and residents to deliver higher-value healthcare by emphasizing that effective patient care is not measured by a single episode or clinical decision, but is defined through a lifelong partnership between the patient and the healthcare system. As the country moves toward improved holistic models of care and financing, physician leadership in care redesign is essential to ensure that quality, safety, and patient well-being are not sacrificed at the altar of cost savings.

Disclosures

Dr. Johnson is a Consultant and Advisory Board Member at Oliver Wyman, receives salary support from an AHRQ grant, and has pending potential royalties from licensure of evidence-based appropriate use guidelines/criteria to AgilMD (Agile is a clinical decision support company). The other authors have no relevant disclosures. Dr. Johnson and Dr. Pahwa are Co-directors, High Value Practice Academic Alliance, www.hvpaa.org

1. Arora V, Moriates C. Tackling the minimizers behind high value care. J Hos Med. 2019: 14(5):318-319. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3104 PubMed

2. Alvin MD, Jaffe AS, Ziegelstein RC, Trost JC. Eliminating creatine kinase-myocardial band testing in suspected acute coronary syndrome: a value-based quality improvement. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1508-1512. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3597. PubMed

3. Daniel M, Keller S, Mozafarihashjin M, Pahwa A, Soong C. An implementation guide to reducing overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 018;178(2):271-276. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7290. PubMed

4. Sadana D, Pratzer A, Scher LJ, et al. Promoting high-value practice by reducing unnecessary transfusions with a patient blood management program. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(1):116-122. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6369. PubMed

5. Raja AS, Greenberg JO, Qaseem A, et al. Evaluation of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism: Best practice advice from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(9):701-711. doi: 10.7326/M14-1772 PubMed

6. The Burden of Medical Debt: Results from the Kaiser Family Foundation/New York Times Medical Bills Survey. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/report/the-burden-of-medical-debt-results-from-the-kaiser-family-foundationnew-york-times-medical-bills-survey/. Accessed December 2, 2018.

7. Maryland Total Cost of Care Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/md-tccm/. Accessed December 2, 2018

8. Grady D, Redberg RF, O’Malley PG. Quality improvement for quality improvement studies. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):187. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6875. PubMed

9. Hoffmann U, Truong QA, Schoenfeld DA, et al. Coronary CT angiography versus standard evaluation in acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:299-308. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201161. PubMed

10. DeCamp M, Tilburt JC. Ethics and high-value care. J Med Ethics. 2017;43(5):307-309. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103880. PubMed

1. Arora V, Moriates C. Tackling the minimizers behind high value care. J Hos Med. 2019: 14(5):318-319. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3104 PubMed

2. Alvin MD, Jaffe AS, Ziegelstein RC, Trost JC. Eliminating creatine kinase-myocardial band testing in suspected acute coronary syndrome: a value-based quality improvement. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1508-1512. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3597. PubMed

3. Daniel M, Keller S, Mozafarihashjin M, Pahwa A, Soong C. An implementation guide to reducing overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 018;178(2):271-276. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7290. PubMed

4. Sadana D, Pratzer A, Scher LJ, et al. Promoting high-value practice by reducing unnecessary transfusions with a patient blood management program. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(1):116-122. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6369. PubMed

5. Raja AS, Greenberg JO, Qaseem A, et al. Evaluation of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism: Best practice advice from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(9):701-711. doi: 10.7326/M14-1772 PubMed

6. The Burden of Medical Debt: Results from the Kaiser Family Foundation/New York Times Medical Bills Survey. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/report/the-burden-of-medical-debt-results-from-the-kaiser-family-foundationnew-york-times-medical-bills-survey/. Accessed December 2, 2018.

7. Maryland Total Cost of Care Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/md-tccm/. Accessed December 2, 2018

8. Grady D, Redberg RF, O’Malley PG. Quality improvement for quality improvement studies. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):187. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6875. PubMed

9. Hoffmann U, Truong QA, Schoenfeld DA, et al. Coronary CT angiography versus standard evaluation in acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:299-308. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201161. PubMed

10. DeCamp M, Tilburt JC. Ethics and high-value care. J Med Ethics. 2017;43(5):307-309. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103880. PubMed

Tackling the Minimizers Hiding Behind High-Value Care

With the escalating need for academic health centers to control costs, high-value care initiatives targeted at residents have exploded. Recent estimates suggest that more than two-thirds of internal medicine residency programs have high-value care curricula.1 This growth has been catalyzed, in part, by compelling evidence suggesting that where the residents undergo training is strongly associated with their future utilization.2 Although we encourage, support, and participate in high-value care education, as hospitalists, there are potential consequences of the high-value care movement in medical training.

Minimizers – physicians who underestimate the signs and symptoms of a patient, hastily concluding that they have the most benign condition possible – have always existed within residency training. The ethos of “doing nothing” has been around since at least the days of the widely read medical satire House of God.3 However, the increasing focus on high-value care creates a socially acceptable banner for minimizers to hide behind when defending inappropriately doing less. For an inpatient with unexplained localized abdominal pain not responding to conservative therapy, a minimizing resident may report to the attending, “They’re fine. I am trying to practice high-value care and avoid getting a CT scan.”

In their 2011 book, Your Medical Mind, Groopman and Hartzband described how people naturally fall on a scale between medical maximizing and minimizing and how this influences their approach toward healthcare.4 Researchers have expanded this construct to create a “Maximizer-Minimizer Scale,” which has been used for studying patients and how these traits affect the degree of medical care they receive.5 Similar approaches could be used for identifying physicians and trainees at risk of too much minimizer behavior. Although the vast majority of trainees are not minimizers, and overuse continues to be the bigger problem in the majority of academic settings, it is important to understand how the high-value care movement could facilitate minimalist behavior in some residents. Although this article focuses on the educational system, the potential for minimization exists at all levels of clinical practice, including faculty and practicing physicians. Tackling this problem requires understanding the factors that promote the creation of minimizers, how patients and trainees are affected, and the solutions for preventing the spread of minimizers.

FACTORS THAT PROMOTE THE CREATION OF MINIMIZERS

Several factors may predispose a resident physician to become a minimizer. For example, resident burnout and overwhelming caseloads can contribute to the desire to decrease work by any means necessary. There are several ways a minimizer can accomplish this goal on inpatient rounds. First, a minimizer may present an important or acute problem as an “outpatient issue” that does not require inpatient workup. Second, minimizers may avoid requesting necessary consults, particularly those associated with intensive workups such as neurology, infectious disease, and rheumatology. Minimizers would claim that this is because of a concern of an unnecessary “costly workup,” when in reality they fear discovery of new problems, more tests to follow-up, and a potentially prolonged length of stay. Ironically, an institutional focus on hospital throughput can reinforce minimizers since the attending physicians or the hospital administrators may applaud them for avoiding “extra nights” in the hospital.

In addition to high workloads, inadequate clinical expertise favors the creation of minimizers. Although resident physicians may be aware that the probability of a rare disease is low, they may not recognize when ruling it out is appropriate. Thus, they could dismiss subtle cues or patterns that point to the need for further workup. Although attending physicians serve as a safety net, it could take time for them to recognize a resident minimizer who may be presenting biased information that influences their clinical decisions. Moreover, attending physicians may avoid further probing so that they are not perceived as promoting overuse and waste.

DANGERS OF MINIMIZERS

There are several dangers posed by minimizers, but the most concerning is the impact on patients. Missed diagnoses are a common source of patient maltreatment and contribute to avoidable deaths.6 Patients treated by minimizers may continue to experience their acute problem or have to be readmitted because of inadequate treatment. These patients may also lose faith or their trust in the medical system because of inattention to their problems. In fact, minimizing behaviors could have the greatest negative impact on the most vulnerable patients, who often cannot advocate for themselves or who may face conscious and unconscious biases, such as assumptions that they are “pain medication-seeking.”

In addition to harming patients, minimizers can jeopardize learning opportunities. A minimizer resident squanders the chance to recognize and contribute toward caring for a patient with a rare disease, diminishing their overall clinical development. Other trainees lose the opportunity to learn due to consultations or procedures never obtained. Lastly, as inappropriate attitudes and practices of minimizers spread through the hidden curriculum, particularly to medical students beginning their training, the overall clinical learning environment suffers.

SOLUTIONS FOR PREVENTING THE CREATION OF MINIMIZERS

There are specific techniques that academic hospitalists and teaching attending physicians can use to help curb the creation of minimizers and promote a clinical learning environment that counters these behaviors. First, instead of focusing on financial costs, it is important for educators to teach the true concept of healthcare value and the primary importance of improving patient outcomes. Embedding appropriateness criteria, such as those from the American College of Radiology, into daily workflows can enable residents to consider not just the cost of imaging but rather the appropriateness given a specific indication.7 Training programs can provide residents with a closed-loop feedback on patient outcomes so that they can recognize whether a diagnosis was missed or a necessary test was not ordered. Additionally, it is critical for residents to understand that improving healthcare value requires taking a big picture view of costs, particularly from the perspective of patients.8 A patient readmitted after receiving a minimalist workup is more costly to both the patient and the healthcare system.

Second, it is important for the hospitalist faculty to emphasize when a patient has failed a conservative approach and a more specialized, and sometimes intensive, workup or management strategy is appropriate. The classic example is a patient transferred from a community hospital to a tertiary center for further evaluation. Such patients are outside the scope of well-established guidelines. It is precisely these patients that Choosing Wisely or “Less is More” recommendations often do not apply. In contrast, transfer patients often do not end up receiving the specialty procedures that they were originally referred for9; it is important that all remain vigilant and committed to high-value care to avoid overuse in these situations.

Exposing residents to cognitive biases is equally important. For example, anchoring can lead to early closure, an easy path for a minimizer to follow. Given the recent focus on the harms related to diagnostic errors, more training in these biases can help promote better patient outcomes.10

Lastly, it is critical that hospitalists emphasize the importance of prioritizing a patient’s overall health to learners. Although it is tempting for trainees to focus only on acute episodes of a hospital stay, a holistic approach to patients and their quality of life can avoid the minimizer trap. The recent proposal to use home-to-home days in lieu of the routine length of hospital stay is a wonderful example of “measuring what matters to patients” and removing incentives for inappropriately shifting care to other clinicians or venues.11 Likewise, alternative payment models for emphasizing patient outcomes over time can create systems that reinforce holistic views of patient health.

CONCLUSION

The increasing focus on delivering high-value care has created a socially acceptable excuse for minimizers, who could thrive relatively unchecked in the clinical learning environment. To counter this unintended consequence, hospitalists must learn to identify minimizing behavior and actively guard against these tendencies by highlighting the value of appropriate care, not just doing less, and always striving to provide the best care for patients.

Disclosures

Dr. Arora reports personal fees from the American Board of Internal Medicine and personal fees from McGraw Hill, outside the submitted work. Dr. Moriates reports personal fees from McGraw Hill, outside the submitted work.

1. 2014 APDIM Program Directors Survey- Summary File. http://www.im.org/d/do/6030. Accessed on July 18, 2017.

2. Chen C, Petterson S, Phillips R, Bazemore A, Mullan F. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2385-2393. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15973 PubMed

3. Shem S. The House of God. London, UK: Bodley Head; 1979.

4. Groopman J, Hartzband P. Your Medical Mind: How to Decide What Is Right for You. Reprint edition. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2012.

5. Scherer LD, Caverly TJ, Burke J, et al. Development of the Medical Maximizer-Minimizer Scale. Health Psychol. 2016;35(11):1276-1287. doi: 10.1037/hea0000417 PubMed

6. National Academies of Sciences E. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care.; 2015. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/21794/improving-diagnosis-in-health-care. Accessed September 13, 2018.

7. American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria. https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/ACR-Appropriateness-Criteria. Accessed on July 28, 2018.

8. Parikh RB, Milstein A, Jain SH. Getting real about health care costs — a broader approach to cost stewardship in medical education. N Engl J Med.2017;376(10):913-915. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1612517 PubMed

9. Mueller SK, Zheng J, Orav EJ, Schnipper JL. Interhospital transfer and receipt of specialty procedures. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):383-387. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2875 PubMed

10. Trowbridge RL, Dhaliwal G, Cosby KS. Educational agenda for diagnostic error reduction. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(2 Suppl):ii28-ii32. PubMed

11. Barnett ML, Grabowski DC, Mehrotra A. Home-to-home time - measuring what matters to patients and payers. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):4-6. PubMed

With the escalating need for academic health centers to control costs, high-value care initiatives targeted at residents have exploded. Recent estimates suggest that more than two-thirds of internal medicine residency programs have high-value care curricula.1 This growth has been catalyzed, in part, by compelling evidence suggesting that where the residents undergo training is strongly associated with their future utilization.2 Although we encourage, support, and participate in high-value care education, as hospitalists, there are potential consequences of the high-value care movement in medical training.

Minimizers – physicians who underestimate the signs and symptoms of a patient, hastily concluding that they have the most benign condition possible – have always existed within residency training. The ethos of “doing nothing” has been around since at least the days of the widely read medical satire House of God.3 However, the increasing focus on high-value care creates a socially acceptable banner for minimizers to hide behind when defending inappropriately doing less. For an inpatient with unexplained localized abdominal pain not responding to conservative therapy, a minimizing resident may report to the attending, “They’re fine. I am trying to practice high-value care and avoid getting a CT scan.”

In their 2011 book, Your Medical Mind, Groopman and Hartzband described how people naturally fall on a scale between medical maximizing and minimizing and how this influences their approach toward healthcare.4 Researchers have expanded this construct to create a “Maximizer-Minimizer Scale,” which has been used for studying patients and how these traits affect the degree of medical care they receive.5 Similar approaches could be used for identifying physicians and trainees at risk of too much minimizer behavior. Although the vast majority of trainees are not minimizers, and overuse continues to be the bigger problem in the majority of academic settings, it is important to understand how the high-value care movement could facilitate minimalist behavior in some residents. Although this article focuses on the educational system, the potential for minimization exists at all levels of clinical practice, including faculty and practicing physicians. Tackling this problem requires understanding the factors that promote the creation of minimizers, how patients and trainees are affected, and the solutions for preventing the spread of minimizers.

FACTORS THAT PROMOTE THE CREATION OF MINIMIZERS

Several factors may predispose a resident physician to become a minimizer. For example, resident burnout and overwhelming caseloads can contribute to the desire to decrease work by any means necessary. There are several ways a minimizer can accomplish this goal on inpatient rounds. First, a minimizer may present an important or acute problem as an “outpatient issue” that does not require inpatient workup. Second, minimizers may avoid requesting necessary consults, particularly those associated with intensive workups such as neurology, infectious disease, and rheumatology. Minimizers would claim that this is because of a concern of an unnecessary “costly workup,” when in reality they fear discovery of new problems, more tests to follow-up, and a potentially prolonged length of stay. Ironically, an institutional focus on hospital throughput can reinforce minimizers since the attending physicians or the hospital administrators may applaud them for avoiding “extra nights” in the hospital.

In addition to high workloads, inadequate clinical expertise favors the creation of minimizers. Although resident physicians may be aware that the probability of a rare disease is low, they may not recognize when ruling it out is appropriate. Thus, they could dismiss subtle cues or patterns that point to the need for further workup. Although attending physicians serve as a safety net, it could take time for them to recognize a resident minimizer who may be presenting biased information that influences their clinical decisions. Moreover, attending physicians may avoid further probing so that they are not perceived as promoting overuse and waste.

DANGERS OF MINIMIZERS

There are several dangers posed by minimizers, but the most concerning is the impact on patients. Missed diagnoses are a common source of patient maltreatment and contribute to avoidable deaths.6 Patients treated by minimizers may continue to experience their acute problem or have to be readmitted because of inadequate treatment. These patients may also lose faith or their trust in the medical system because of inattention to their problems. In fact, minimizing behaviors could have the greatest negative impact on the most vulnerable patients, who often cannot advocate for themselves or who may face conscious and unconscious biases, such as assumptions that they are “pain medication-seeking.”

In addition to harming patients, minimizers can jeopardize learning opportunities. A minimizer resident squanders the chance to recognize and contribute toward caring for a patient with a rare disease, diminishing their overall clinical development. Other trainees lose the opportunity to learn due to consultations or procedures never obtained. Lastly, as inappropriate attitudes and practices of minimizers spread through the hidden curriculum, particularly to medical students beginning their training, the overall clinical learning environment suffers.

SOLUTIONS FOR PREVENTING THE CREATION OF MINIMIZERS

There are specific techniques that academic hospitalists and teaching attending physicians can use to help curb the creation of minimizers and promote a clinical learning environment that counters these behaviors. First, instead of focusing on financial costs, it is important for educators to teach the true concept of healthcare value and the primary importance of improving patient outcomes. Embedding appropriateness criteria, such as those from the American College of Radiology, into daily workflows can enable residents to consider not just the cost of imaging but rather the appropriateness given a specific indication.7 Training programs can provide residents with a closed-loop feedback on patient outcomes so that they can recognize whether a diagnosis was missed or a necessary test was not ordered. Additionally, it is critical for residents to understand that improving healthcare value requires taking a big picture view of costs, particularly from the perspective of patients.8 A patient readmitted after receiving a minimalist workup is more costly to both the patient and the healthcare system.

Second, it is important for the hospitalist faculty to emphasize when a patient has failed a conservative approach and a more specialized, and sometimes intensive, workup or management strategy is appropriate. The classic example is a patient transferred from a community hospital to a tertiary center for further evaluation. Such patients are outside the scope of well-established guidelines. It is precisely these patients that Choosing Wisely or “Less is More” recommendations often do not apply. In contrast, transfer patients often do not end up receiving the specialty procedures that they were originally referred for9; it is important that all remain vigilant and committed to high-value care to avoid overuse in these situations.

Exposing residents to cognitive biases is equally important. For example, anchoring can lead to early closure, an easy path for a minimizer to follow. Given the recent focus on the harms related to diagnostic errors, more training in these biases can help promote better patient outcomes.10

Lastly, it is critical that hospitalists emphasize the importance of prioritizing a patient’s overall health to learners. Although it is tempting for trainees to focus only on acute episodes of a hospital stay, a holistic approach to patients and their quality of life can avoid the minimizer trap. The recent proposal to use home-to-home days in lieu of the routine length of hospital stay is a wonderful example of “measuring what matters to patients” and removing incentives for inappropriately shifting care to other clinicians or venues.11 Likewise, alternative payment models for emphasizing patient outcomes over time can create systems that reinforce holistic views of patient health.

CONCLUSION

The increasing focus on delivering high-value care has created a socially acceptable excuse for minimizers, who could thrive relatively unchecked in the clinical learning environment. To counter this unintended consequence, hospitalists must learn to identify minimizing behavior and actively guard against these tendencies by highlighting the value of appropriate care, not just doing less, and always striving to provide the best care for patients.

Disclosures

Dr. Arora reports personal fees from the American Board of Internal Medicine and personal fees from McGraw Hill, outside the submitted work. Dr. Moriates reports personal fees from McGraw Hill, outside the submitted work.

With the escalating need for academic health centers to control costs, high-value care initiatives targeted at residents have exploded. Recent estimates suggest that more than two-thirds of internal medicine residency programs have high-value care curricula.1 This growth has been catalyzed, in part, by compelling evidence suggesting that where the residents undergo training is strongly associated with their future utilization.2 Although we encourage, support, and participate in high-value care education, as hospitalists, there are potential consequences of the high-value care movement in medical training.

Minimizers – physicians who underestimate the signs and symptoms of a patient, hastily concluding that they have the most benign condition possible – have always existed within residency training. The ethos of “doing nothing” has been around since at least the days of the widely read medical satire House of God.3 However, the increasing focus on high-value care creates a socially acceptable banner for minimizers to hide behind when defending inappropriately doing less. For an inpatient with unexplained localized abdominal pain not responding to conservative therapy, a minimizing resident may report to the attending, “They’re fine. I am trying to practice high-value care and avoid getting a CT scan.”

In their 2011 book, Your Medical Mind, Groopman and Hartzband described how people naturally fall on a scale between medical maximizing and minimizing and how this influences their approach toward healthcare.4 Researchers have expanded this construct to create a “Maximizer-Minimizer Scale,” which has been used for studying patients and how these traits affect the degree of medical care they receive.5 Similar approaches could be used for identifying physicians and trainees at risk of too much minimizer behavior. Although the vast majority of trainees are not minimizers, and overuse continues to be the bigger problem in the majority of academic settings, it is important to understand how the high-value care movement could facilitate minimalist behavior in some residents. Although this article focuses on the educational system, the potential for minimization exists at all levels of clinical practice, including faculty and practicing physicians. Tackling this problem requires understanding the factors that promote the creation of minimizers, how patients and trainees are affected, and the solutions for preventing the spread of minimizers.

FACTORS THAT PROMOTE THE CREATION OF MINIMIZERS

Several factors may predispose a resident physician to become a minimizer. For example, resident burnout and overwhelming caseloads can contribute to the desire to decrease work by any means necessary. There are several ways a minimizer can accomplish this goal on inpatient rounds. First, a minimizer may present an important or acute problem as an “outpatient issue” that does not require inpatient workup. Second, minimizers may avoid requesting necessary consults, particularly those associated with intensive workups such as neurology, infectious disease, and rheumatology. Minimizers would claim that this is because of a concern of an unnecessary “costly workup,” when in reality they fear discovery of new problems, more tests to follow-up, and a potentially prolonged length of stay. Ironically, an institutional focus on hospital throughput can reinforce minimizers since the attending physicians or the hospital administrators may applaud them for avoiding “extra nights” in the hospital.

In addition to high workloads, inadequate clinical expertise favors the creation of minimizers. Although resident physicians may be aware that the probability of a rare disease is low, they may not recognize when ruling it out is appropriate. Thus, they could dismiss subtle cues or patterns that point to the need for further workup. Although attending physicians serve as a safety net, it could take time for them to recognize a resident minimizer who may be presenting biased information that influences their clinical decisions. Moreover, attending physicians may avoid further probing so that they are not perceived as promoting overuse and waste.

DANGERS OF MINIMIZERS

There are several dangers posed by minimizers, but the most concerning is the impact on patients. Missed diagnoses are a common source of patient maltreatment and contribute to avoidable deaths.6 Patients treated by minimizers may continue to experience their acute problem or have to be readmitted because of inadequate treatment. These patients may also lose faith or their trust in the medical system because of inattention to their problems. In fact, minimizing behaviors could have the greatest negative impact on the most vulnerable patients, who often cannot advocate for themselves or who may face conscious and unconscious biases, such as assumptions that they are “pain medication-seeking.”

In addition to harming patients, minimizers can jeopardize learning opportunities. A minimizer resident squanders the chance to recognize and contribute toward caring for a patient with a rare disease, diminishing their overall clinical development. Other trainees lose the opportunity to learn due to consultations or procedures never obtained. Lastly, as inappropriate attitudes and practices of minimizers spread through the hidden curriculum, particularly to medical students beginning their training, the overall clinical learning environment suffers.

SOLUTIONS FOR PREVENTING THE CREATION OF MINIMIZERS

There are specific techniques that academic hospitalists and teaching attending physicians can use to help curb the creation of minimizers and promote a clinical learning environment that counters these behaviors. First, instead of focusing on financial costs, it is important for educators to teach the true concept of healthcare value and the primary importance of improving patient outcomes. Embedding appropriateness criteria, such as those from the American College of Radiology, into daily workflows can enable residents to consider not just the cost of imaging but rather the appropriateness given a specific indication.7 Training programs can provide residents with a closed-loop feedback on patient outcomes so that they can recognize whether a diagnosis was missed or a necessary test was not ordered. Additionally, it is critical for residents to understand that improving healthcare value requires taking a big picture view of costs, particularly from the perspective of patients.8 A patient readmitted after receiving a minimalist workup is more costly to both the patient and the healthcare system.

Second, it is important for the hospitalist faculty to emphasize when a patient has failed a conservative approach and a more specialized, and sometimes intensive, workup or management strategy is appropriate. The classic example is a patient transferred from a community hospital to a tertiary center for further evaluation. Such patients are outside the scope of well-established guidelines. It is precisely these patients that Choosing Wisely or “Less is More” recommendations often do not apply. In contrast, transfer patients often do not end up receiving the specialty procedures that they were originally referred for9; it is important that all remain vigilant and committed to high-value care to avoid overuse in these situations.

Exposing residents to cognitive biases is equally important. For example, anchoring can lead to early closure, an easy path for a minimizer to follow. Given the recent focus on the harms related to diagnostic errors, more training in these biases can help promote better patient outcomes.10

Lastly, it is critical that hospitalists emphasize the importance of prioritizing a patient’s overall health to learners. Although it is tempting for trainees to focus only on acute episodes of a hospital stay, a holistic approach to patients and their quality of life can avoid the minimizer trap. The recent proposal to use home-to-home days in lieu of the routine length of hospital stay is a wonderful example of “measuring what matters to patients” and removing incentives for inappropriately shifting care to other clinicians or venues.11 Likewise, alternative payment models for emphasizing patient outcomes over time can create systems that reinforce holistic views of patient health.

CONCLUSION

The increasing focus on delivering high-value care has created a socially acceptable excuse for minimizers, who could thrive relatively unchecked in the clinical learning environment. To counter this unintended consequence, hospitalists must learn to identify minimizing behavior and actively guard against these tendencies by highlighting the value of appropriate care, not just doing less, and always striving to provide the best care for patients.

Disclosures

Dr. Arora reports personal fees from the American Board of Internal Medicine and personal fees from McGraw Hill, outside the submitted work. Dr. Moriates reports personal fees from McGraw Hill, outside the submitted work.

1. 2014 APDIM Program Directors Survey- Summary File. http://www.im.org/d/do/6030. Accessed on July 18, 2017.

2. Chen C, Petterson S, Phillips R, Bazemore A, Mullan F. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2385-2393. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15973 PubMed

3. Shem S. The House of God. London, UK: Bodley Head; 1979.

4. Groopman J, Hartzband P. Your Medical Mind: How to Decide What Is Right for You. Reprint edition. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2012.

5. Scherer LD, Caverly TJ, Burke J, et al. Development of the Medical Maximizer-Minimizer Scale. Health Psychol. 2016;35(11):1276-1287. doi: 10.1037/hea0000417 PubMed

6. National Academies of Sciences E. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care.; 2015. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/21794/improving-diagnosis-in-health-care. Accessed September 13, 2018.

7. American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria. https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/ACR-Appropriateness-Criteria. Accessed on July 28, 2018.

8. Parikh RB, Milstein A, Jain SH. Getting real about health care costs — a broader approach to cost stewardship in medical education. N Engl J Med.2017;376(10):913-915. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1612517 PubMed

9. Mueller SK, Zheng J, Orav EJ, Schnipper JL. Interhospital transfer and receipt of specialty procedures. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):383-387. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2875 PubMed

10. Trowbridge RL, Dhaliwal G, Cosby KS. Educational agenda for diagnostic error reduction. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(2 Suppl):ii28-ii32. PubMed

11. Barnett ML, Grabowski DC, Mehrotra A. Home-to-home time - measuring what matters to patients and payers. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):4-6. PubMed

1. 2014 APDIM Program Directors Survey- Summary File. http://www.im.org/d/do/6030. Accessed on July 18, 2017.

2. Chen C, Petterson S, Phillips R, Bazemore A, Mullan F. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2385-2393. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15973 PubMed

3. Shem S. The House of God. London, UK: Bodley Head; 1979.

4. Groopman J, Hartzband P. Your Medical Mind: How to Decide What Is Right for You. Reprint edition. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2012.

5. Scherer LD, Caverly TJ, Burke J, et al. Development of the Medical Maximizer-Minimizer Scale. Health Psychol. 2016;35(11):1276-1287. doi: 10.1037/hea0000417 PubMed

6. National Academies of Sciences E. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care.; 2015. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/21794/improving-diagnosis-in-health-care. Accessed September 13, 2018.

7. American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria. https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/ACR-Appropriateness-Criteria. Accessed on July 28, 2018.

8. Parikh RB, Milstein A, Jain SH. Getting real about health care costs — a broader approach to cost stewardship in medical education. N Engl J Med.2017;376(10):913-915. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1612517 PubMed

9. Mueller SK, Zheng J, Orav EJ, Schnipper JL. Interhospital transfer and receipt of specialty procedures. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):383-387. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2875 PubMed

10. Trowbridge RL, Dhaliwal G, Cosby KS. Educational agenda for diagnostic error reduction. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(2 Suppl):ii28-ii32. PubMed

11. Barnett ML, Grabowski DC, Mehrotra A. Home-to-home time - measuring what matters to patients and payers. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):4-6. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Pharmacologic Management of Malignant Bowel Obstruction: When Surgery Is Not an Option

Malignant bowel obstruction (MBO) is a catastrophic complication of cancer that often requires hospitalization and a multidisciplinary approach in its management. Hospitalists frequently collaborate with such specialties as Hematology/Oncology, Surgery, Palliative Medicine, and Interventional Radiology in arriving at a treatment plan.

Initial management is focused on hydration, bowel rest and decompression via nasogastric (NG) tube. Surgical resection or endoscopic stenting should be considered early.1 However, patients who present in the terminal stages may be poor candidates for these options due to diminished functional status, multiple areas of obstruction, complicated anatomy limiting intervention, or an associated large volume of ascites.

Presence of inoperable MBO portends a poor prognosis, often measured in weeks.2 Presentation often occurs in the context of a sentinel hospitalization, signifying a shift in disease course.3,4 It is essential for hospitalists to be familiar with noninvasive therapies for inoperable MBO given the increasing role of hospitalists in providing inpatient palliative care. Palliative pharmacologic management of MBO can reduce symptom burden during these terminal stages and will be the focus of this paper.

BACKGROUND AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Malignant bowel obstruction occurs in about 3%-15% of patients with cancer.2 A consensus definition of MBO established the following specific criteria: (1) clinical evidence of bowel obstruction, (2) obstruction distal to the ligament of Treitz, and (3) the presence of primary intra-abdominal cancer with incurable disease or extra-abdominal cancer with peritoneal involvement.5 The most common malignancies are gastric, colorectal, and ovarian in origin.1,2 The most common extra-abdominal malignancies associated with MBO are breast, melanoma, and lung. MBO is most frequently diagnosed during the advanced stages of cancer.2 The obstruction can involve a partial or total blockage of the small or large intestine from either an intrinsic or extrinsic source. Peristalsis may also be impaired via direct tumor infiltration of the intestinal walls or within the enteric nervous system or celiac plexus. Other etiologies of MBO include peritoneal carcinomatosis and radiation-induced fibrosis.1,6 The obstruction can occur at a single level or involve multiple areas, which usually precludes surgical intervention.2

Symptoms of MBO can be insidious in onset and take several weeks to manifest. The most prevalent symptoms are nausea, vomiting, constipation, abdominal pain, and distension.2,6 The intermittent pattern of symptoms may evolve into continuous episodes with spontaneous remission in between. The etiology of symptoms can be attributed to distension proximal to the site of obstruction with concomitantly increased gastrointestinal and pancreaticobiliary secretions.

The distension creates a “hypertensive state” in the intestinal lumen causing enterochromaffin cells to release serotonin which activates the enteric nervous system and its effectors including substance P, nitric oxide, acetylcholine, somatostatin, and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP). These neurotransmitters stimulate the secretomotor actions that cause hypersecretion of mucus from cells of the intestinal crypts. Additional water and sodium secretions accumulate due to the expanded surface area of the bowel.1,2 Overloaded with luminal contents, the bowel attempts to overcome the obstruction by contracting, which leads to colicky abdominal pain. Tumor burden can also damage the intestinal epithelium and cause continuous pain.

INITIAL MANAGEMENT

Fluid resuscitation, electrolyte repletion, and a trial of NG tube decompression are part of the initial management of MBO (Figure ). While studies have shown that moderate intravenous hydration can minimize nausea and drowsiness, excessive fluids may worsen bowel edema and exacerbate vomiting.1,8 NG tube decompression is most effective in patients with proximal obstructions but some studies suggest it can decrease vomiting in patients with colonic obstructions as well.9 Computed tomography imaging can identify the extent of the tumor, the transition point of the obstruction, and any distant metastases. Surgery, Gastroenterology, and/or Interventional Radiology consultation should be obtained early to evaluate options for direct decompression. Hematology/Oncology and Radiation/Oncology referral may help delineate prognosis and achievable outcomes. Emergent exploratory surgery may be required in cases of bowel perforation or ischemia. Otherwise, a planned surgical resection should be considered in those with an isolated resectable lesion and acceptable perioperative risk. Colorectal or duodenal stents may be an option for those who are not surgical candidates or as a bridge to surgery.

As bowel obstruction is often a late manifestation of advanced malignancy, many patients may not be appropriate candidates for operative/interventional treatment due to malnutrition, comorbid conditions, or anatomic considerations. For these individuals, pharmacologic management is the mainstay of treatment. Additionally, the pharmacologic approaches detailed below may provide benefit as adjunctive therapy for patients undergoing procedural intervention.7 Consultation for early palliative care can improve symptom control as well as clarify goals of care.

PHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT

Given the pathophysiology of MBO, pharmacologic therapies are focused on controlling nausea and pain while reducing bowel edema and secretions.

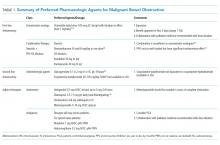

Antiemetic Agents

Nausea and vomiting in MBO are due to activation of vagal nerve fibers in the gastric wall and stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ).10 Dopamine antagonists have started to gain favor for MBO compared to more commonly used antiemetics such as the serotonin antagonists. Haloperidol should be considered as a first-line antiemetic in patients with MBO. Its potent D2-receptor antagonistic properties block receptors in the CTZ. The high affinity of the drug for only the D2-receptor makes it preferable to alternative agents in the same class such as chlorpromazine. However, haloperidol may cause or worsen QT prolongation and should be avoided in patients with Parkinson’s disease. The medication has less sedative and unwanted anticholinergic side effects due to its limited interaction with histaminergic and acetylcholine receptors.11 Haloperidol has been shown in the past to be efficacious for post-operative nausea but there are few randomized controlled trials in the terminally ill.12 Nonetheless, recent consensus guidelines from the Multinational Association of Supportive Care recommended haloperidol as the initial treatment of nausea for individuals with MBO based on available systematic reviews.10

Other dopamine antagonists remain good options, though they may cause additional side effects due to actions on other receptor types. Metoclopramide, another D2-receptor antagonist, has been shown to be effective in the treatment of nausea and vomiting due to advanced cancer.13 However as a prokinetic agent, this medication should be avoided in those with complete MBO and only considered in those with partial MBO.10,14

Olanzapine, an atypical antipsychotic, may also have a role in controlling nausea in patients with MBO. It functions as a 5-HT2A and D2-receptor antagonist, with a slightly greater affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor. Olanzapine thus can target two critical receptors playing a role in nausea and vomiting. A study of patients with incomplete bowel obstruction found the addition of olanzapine significantly decreased nausea and vomiting in patients who were refractory to other treatments including steroids and haloperidol.15 Olanzapine has the added advantage of single-day dosing as well as an oral disintegrating formulation.16

Intravenous and sublingual preparations of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists such as ondansetron are commonly used in the inpatient setting. These medications are potent antiemetics that exhibit their effects via pathways where serotonin acts as a neurotransmitter.17 An alternative agent, tropisetron, has shown promise when used alone or in conjunction with metoclopramide but is not currently available in the US.18 Granisetron is available in a transdermal formulation, which can be very convenient for patients with bowel obstruction. Its mechanism of action differs from ondansetron as it is an allosteric inhibitor rather than a competitive inhibitor.19 Granisetron needs more specific study with regards to its role in MBO.

Although haloperidol remains the initial choice, combination therapy can help to decrease the risk of extrapyramidal symptoms seen with higher doses of dopaminergic monotherapy.

Analgesics

Pain control is an essential part of the palliative treatment of MBO as bowel distention, secretions, and edema can cause rapid onset of pain. Parenteral step three opioids remain the optimal initial choice since patients are unable to take medications orally and may have compromised absorption. Opioids address both the colicky and continuous aspects of MBO pain.

Short-acting intravenous opioids such as morphine or hydromorphone may be scheduled every four hours with breakthrough dosing every hour in between. Alternatively, analgesics can be administered via a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump.1 Although doses vary across patients, opioid-naïve patients can be initiated on a low dose therapy such as hydromorphone 0.2 mg IV/SC or morphine 1 mg IV/SC every four hours as needed for pain control.

Ongoing pain management for patients with MBO requires coordination of care. Many patients will elect to receive hospice care following discharge. Direct communication with palliative consultants and hospice providers can help facilitate a smooth transition. In patients for whom bowel obstruction resolves, transition to oral opioids based on morphine equivalent daily dose is indicated with further dose adjustment as patients may have reduced pain at this stage.

Options for patients with unresolved obstruction include transdermal and sublingual preparations as well as outpatient PCA with hospice support. Transdermal fentanyl patch can be useful but onset of peak levels occur within 8-12 hours.20 The patch is usually exchanged every 72 hours and is most effective when applied to areas containing adipose tissue which may limit its use in cachectic patients. The liquid preparation of methadone can be useful even in patients with unresolved MBO. Its lipophilic properties allow for ease of absorption.21 A baseline electrocardiogram (EKG) is recommended prior to methadone initiation due to the potential for QT prolongation. Methadone should not be a first-line option for opioid-naïve individuals due to its longer onset of action which limits rapid dose titration. Close collaboration with palliative medicine is highly recommended when using longer acting opioids.

Antisecretory Agents

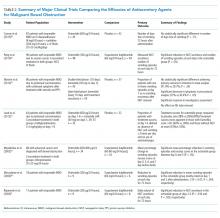

Antisecretory agents are a mainstay of the pharmacologic management of inoperable MBO. Medications that reduce secretions and bowel edema include: somatostatin analogs, H2-blockers, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), steroids, and anticholinergic agents. Table 2 summarizes the major studies comparing various antisecretory medications.

Octreotide, a somatostatin analog, has been increasingly used for the palliative treatment of MBO. The mechanism of action involves splanchnic vasoconstriction, reduction of intestinal and pancreatic secretions (via inhibition of VIP), decrease in gastric emptying, and slowing of smooth muscle contractions.22 Octreotide comes in an immediate-release formulation with an initial subcutaneous dose of 100 µg three or four times per day. Most patients will require 300-800 µg/day, maximum dose being up to 1 mg/day.22,23 A long-acting formulation, lanreotide, exists but can be difficult to obtain and may not provide the immediate relief needed in an acute care setting.

Initiation of octreotide should be considered in the presence of persistent symptoms. Studies have suggested that the benefit of octreotide is most apparent in the first three days of treatment (range 1-5 days).6,22,24 The medication should be discontinued if there is no clinical improvement such as reduction of NG tube output. Octreotide has been shown to be more efficacious than anticholinergic agents in reducing secretions as well as frequency of nausea and vomiting.8,25-28 Octreotide expedites NG tube removal, recovery of bowel function, and improvement in quality of life.29-32 The medication should also be considered in cases of recurrent MBO that previously responded to the medication.

Octreotide is considered the first-line agent in the palliative treatment of MBO, however the medication is costly. Recent studies suggest combination therapy with steroids and H2-blockers or PPIs may be an equally effective and less expensive alternative. The primary rationale for the use of steroids in MBO is their ability to decrease peritumoral edema and promote salt and water absorption from the intestine.1,2 PPIs and H2-blockers decrease distension, pain, and vomiting by reducing the volume of gastric secretions.33 A recent meta-analysis of phase 3 trials found both PPIs and H2-blockers to be effective in lowering volumes of gastric aspirates with ranitidine being slightly superior.34

Initial research into the utility of steroids in MBO garnered mixed results. One study showed marginal benefit for steroid plus octreotide combination therapy compared to octreotide, in a cohort of 27 patients.35 A subsequent review of practice patterns in the management of terminal MBO in Japan found that patients given steroids in combination with octreotide compared to octreotide alone were more likely to undergo early NG tube removal.36 A 1999 systematic review of corticosteroid treatment of MBO concluded low morbidity associated with the medications with a trend toward benefit that was not statistically significant.37 A 2015 study by Currow showed the addition of octreotide in patients already on a regime of dexamethasone and ranitidine did not improve the number of days free from vomiting but did reduce vomiting episodes in those with the most refractory symptoms.38

Collectively, the studies suggest that combination therapy with steroid and PPI or H2 blocker could be a less expensive option in the initial management of MBO. Alternatively, steroids may provide additional relief in patients with continued symptoms on octreotide and H2-blockers. Dexamethasone is preferable given its longer half-life and decreased propensity for sodium retention. Dosing of dexamethasone should be 8 mg IV once a day.38

Anticholinergic agents also reduce secretions. However, they are considered second-line therapy given their lower efficacy compared to other treatment options as well as their propensity to worsen cognitive function.1,2 Anticholinergics may benefit patients with continued symptoms who cannot tolerate the side effects of other treatments. Scopolamine, also known as hyoscine hydrobromide in the US, should be avoided as it crosses the blood-brain barrier. The quaternary formulation, scopolamine butylbromide (hyoscine butylbromide), does not pass this barrier but is currently not available in the US. Glycopyrrolate may be considered as it is also a quaternary ammonium compound that does not cross the blood-brain barrier. Several case reports have described its effectiveness in the resolution of refractory nausea and vomiting in combination with haloperidol and hydromorphone for symptom control.39 Effective oral care is imperative if anticholinergics are used in order to prevent the unpleasant feeling of dry mouth.

SUBSEQUENT SUPPORTIVE CARE

While initial management of MBO often requires placement of an NG tube, prolonged placement can increase the risk for erosions, aspiration, and sinus infections. Removal of the NG tube is most successful when secretions are minimal, but this may not happen unless the obstruction resolves. Some patients may elect to keep an NG tube if symptoms cannot be otherwise controlled by medications.

A venting gastrostomy tube can be considered as an alternative to prolonged NG tube placement. The tube may help alleviate distressing symptoms and can enhance the quality of life of patients by allowing the sensation of oral intake, though it will not allow for absorption of nutrients.40 Although a low risk procedure, patients may be too frail to undergo the procedure and may have postprocedure pain and complications. Anatomic abnormalities such as overlying bowel may also prevent the noninvasive percutaneous approach.

In patients with unresolved obstruction, oral intake should be reinitiated with caution with the patient’s wishes taken into account at all times. Some patients may prioritize the comfort derived from eating small amounts over any associated risks of increased nausea and vomiting.

Parenteral nutrition should be avoided in those with inoperable MBO in the advanced stages. The risks of infection, refeeding syndrome, and the discomfort of an intravenous line and intermittent testing may outweigh any benefits given the overall prognosis.41,42

CONCLUSION

Hospitalists are often involved in the initial care of patients with advanced malignancy who present with MBO. When interventions or surgeries to directly alleviate the obstruction are not possible, pharmacologic options are essential in managing burdensome symptoms and improving quality of life. Early Palliative Care referral can also assist with symptom management, emotional support, clarification of goals of care, and transition to the outpatient setting. While patients with inoperable MBO have a poor prognosis, hospitalists can play a vital role in alleviation of suffering in this devastating complication of advanced cancer.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Ripamonti CI, Easson AM, Gerdes H. Management of malignant bowel obstruction. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(8):1105-1115. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.028. PubMed

2. Tuca A, Guell E, Martinez-Losada E, Codorniu N. Malignant bowel obstruction in advanced cancer patients: epidemiology, management, and factors influencing spontaneous resolution. Cancer Manag Res. 2012;4:159-169. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S29297. PubMed

3. Meier DE. Palliative care in hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(1):21-28. doi: 10.1002/jhm.3. PubMed

4. Lin RJ, Adelman RD, Diamond RR, Evans AT. The sentinel hospitalization and the role of palliative care. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):320-323. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2160. PubMed

5. Anthony T, Baron T, Mercadante S, et al. Report of the clinical protocol committee: development of randomized trials for malignant bowel obstruction. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(1 Suppl):S49-S59. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.011. PubMed

6. Laval G, Marcelin-Benazech B, Guirimand F, et al. Recommendations for bowel obstruction with peritoneal carcinomatosis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(1):75-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.08.022. PubMed

7. Ferguson HJ, Ferguson CI, Speakman J, Ismail T. Management of intestinal obstruction in advanced malignancy. Ann Med Surg. 2015;4(3):264-270. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2015.07.018. PubMed

8. Ripamonti C, Mercadante S, Groff L, et al. Role of octreotide, scopolamine butylbromide, and hydration in symptom control of patients with inoperable bowel obstruction and nasogastric tubes: A prospective randomized trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(1):23-34. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(99)00147-5. PubMed

9. Rao W, Zhang X, Zhang J, et al. The role of nasogastric tube in decompression after elective colon and rectum surgery: a meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26(4):423-429. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-1093-4. PubMed