User login

Intraventricular methotrexate may improve survival for medulloblastoma subtypes

according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Investigators conducted a prospective trial of 87 children diagnosed with nonmetastatic medulloblastoma before the age of 4 years who were treated from 2001-2011.

At 5 years after diagnosis, the 42 DMB/MBEN patients had a 93% progression-free survival (PFS) rate, a 100% overall survival (OS) rate, and a 93% craniospinal irradiation (CSI)–free survival rate.

“Our results suggest that ... poor outcomes of patients treated with systemic chemotherapy alone can be improved by the addition of intraventricular [methotrexate],” wrote Martin Mynarek, MD, of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Germany), and colleagues.

However, it was a different story for the 45 patients with classic medulloblastoma (CMB) or large-cell/anaplastic medulloblastoma (CLA), in which outcomes are historically worse. At 5 years, the PFS was 37%, the OS was 62%, and the CSI-free survival was 39% in these patients.

In 2006, the CMB and CLA patients started receiving local radiotherapy in addition to chemotherapy and intraventricular methotrexate, but the radiotherapy did not seem to help with their disease.

“Because data suggest no effects, or even adverse effects, of local radiotherapy, additional development of this approach does not seem justified,” the investigators wrote.

“Interestingly, almost all patients with CMB/LCA had distant or combined relapses after local radiotherapy,” they added. “One might speculate that local radiotherapy reduced disease burden of the primary tumor and subclinical metastasis in the posterior fossa, leading to a survival advantage of distant subclinical metastasis over local residues.”

Treatment details

The 87 patients were enrolled in the BIS4 arm of the HIT 2000 trial (NCT00303810), which was designed to test six protocols and identify the optimal approach for treating young patients with medulloblastoma, supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumor, or ependymoma.

Patients started “HIT-SKK” chemotherapy within 2-4 weeks of surgery. They received three cycles of intravenous cyclophosphamide, vincristine, methotrexate (followed by leucovorin rescue after 42 hours), carboplatin, and etoposide, with concomitant intraventricular methotrexate, for a duration of 6 months (Neuro Oncol. 2011 Jun;13[6]:669-79).

Among patients who achieved a complete remission, treatment was ended after two additional cycles of chemotherapy. For other patients, secondary surgery, radiotherapy, and consolidation chemotherapy were recommended.

Starting in 2006, DMB and MBEN patients without complete remissions, as well as those with CMB or LCA, received 54 Gy of focal radiotherapy to the tumor bed after the first three treatment cycles.

SHH-I vs. SHH-II DMB/MBEN

DNA methylation profiling was available for 50 of the 87 patients in this analysis, 28 of whom had infantile sonic hedgehog (SHH)–activated DMB/MBEN. Data from these 28 patients – and 71 patients in a validation cohort – revealed no significant difference in 5-year PFS or OS based on methylation subtype.

The 5-year PFS was 73% in SHH-I patients and 83% in SHH-II patients (P = .25). The 5-year OS was 88% and 97%, respectively (P = .099).

“This suggests that the higher risk of relapse in the less favorable [SHH-I subtype] can be abrogated by the addition of intraventricular [methotrexate] to systemic chemotherapy,” the investigators wrote.

The results suggest SHH-I patients “markedly benefit” from the addition of intraventricular chemotherapy, according to the authors of a related editorial, Giles Robinson, MD, and Amar Gajjar, MD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn.

“However, cross-trial comparison of PFS among the SHH-II subtype does not suggest that SHH-II patients derive the same benefit,” the editorialists wrote.

These data divide SHH medulloblastoma into SHH-I, which benefits from chemotherapy with intraventricular methotrexate, and SHH-II, which can be cured without intraventricular methotrexate, high-dose chemotherapy, or focal radiotherapy, according to the editorialists.

This new information might prompt investigation of a risk-adapted approach. SHH-II patients would receive a reduced-intensity regimen with systemic chemotherapy only, and SHH-I patients would receive systemic chemotherapy combined with intraventricular methotrexate. This could avoid exposing young children to “more intensive therapy than necessary,” according to the editorialists.

Non-WNT/non-SHH disease

Patients with non-WNT/non-SHH medulloblastoma (CMB or LCA) were divided into molecularly defined subtypes group 3 (n = 14) and group 4 (n = 6). The patients in group 3 had lower survival rates than patients in group 4. The 5-year PFS rate was 36% and 83%, respectively (P < .001 ). The 5-year OS rate was 49% and 100%, respectively (P < .001).

“This represents the third recent publication to describe a poor PFS for group 3, and it signals a desperate need for better therapy,” the editorialists wrote. As for the “encouraging” survival rate for group 4 patients, there were only six subjects, which makes this finding “worthy of follow-up but not actionable.”

Even so, the investigators noted that “although poor survival has been reported for non-SHH CMB/LCA in almost every series of patients treated with CSI-sparing approaches, again, use of intraventricular [methotrexate] might be associated with slightly higher PFS, compared with conventional chemotherapy alone.”

As expected, IQ was significantly lower in patients who received CSI salvage. The mean IQ was 74 in patients who received CSI and 90 in patients who did not (P = .012). Neurocognitive outcomes were poor in general among CMB/LCA survivors, “which was closely related to use of radiotherapy,” according to the investigators.

“It is important to recognize that these studies were not designed to define outcome on the basis of molecular subgroup or subtype and that the sample size in all these studies is small,” Dr. Robinson and Dr. Gajjar wrote. “Thus, caution should be used when basing any treatment recommendation on these results, and it is our strong-held opinion that any treatment change be done on a well-planned and well-monitored clinical trial.”

This research was supported by the German Childhood Cancer Foundation, Styrian Childhood Cancer Foundation, and other organizations. Dr. Mynarek and colleagues disclosed relationships with Medac, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Bayer, Roche, and numerous other companies. Dr. Robinson disclosed relationships with Eli Lilly, Genentech, and Novartis. Dr. Gajjar reported relationships with Genentech and Kazia Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Mynarek M et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Jun 20;38(18):2028-40.

according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Investigators conducted a prospective trial of 87 children diagnosed with nonmetastatic medulloblastoma before the age of 4 years who were treated from 2001-2011.

At 5 years after diagnosis, the 42 DMB/MBEN patients had a 93% progression-free survival (PFS) rate, a 100% overall survival (OS) rate, and a 93% craniospinal irradiation (CSI)–free survival rate.

“Our results suggest that ... poor outcomes of patients treated with systemic chemotherapy alone can be improved by the addition of intraventricular [methotrexate],” wrote Martin Mynarek, MD, of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Germany), and colleagues.

However, it was a different story for the 45 patients with classic medulloblastoma (CMB) or large-cell/anaplastic medulloblastoma (CLA), in which outcomes are historically worse. At 5 years, the PFS was 37%, the OS was 62%, and the CSI-free survival was 39% in these patients.

In 2006, the CMB and CLA patients started receiving local radiotherapy in addition to chemotherapy and intraventricular methotrexate, but the radiotherapy did not seem to help with their disease.

“Because data suggest no effects, or even adverse effects, of local radiotherapy, additional development of this approach does not seem justified,” the investigators wrote.

“Interestingly, almost all patients with CMB/LCA had distant or combined relapses after local radiotherapy,” they added. “One might speculate that local radiotherapy reduced disease burden of the primary tumor and subclinical metastasis in the posterior fossa, leading to a survival advantage of distant subclinical metastasis over local residues.”

Treatment details

The 87 patients were enrolled in the BIS4 arm of the HIT 2000 trial (NCT00303810), which was designed to test six protocols and identify the optimal approach for treating young patients with medulloblastoma, supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumor, or ependymoma.

Patients started “HIT-SKK” chemotherapy within 2-4 weeks of surgery. They received three cycles of intravenous cyclophosphamide, vincristine, methotrexate (followed by leucovorin rescue after 42 hours), carboplatin, and etoposide, with concomitant intraventricular methotrexate, for a duration of 6 months (Neuro Oncol. 2011 Jun;13[6]:669-79).

Among patients who achieved a complete remission, treatment was ended after two additional cycles of chemotherapy. For other patients, secondary surgery, radiotherapy, and consolidation chemotherapy were recommended.

Starting in 2006, DMB and MBEN patients without complete remissions, as well as those with CMB or LCA, received 54 Gy of focal radiotherapy to the tumor bed after the first three treatment cycles.

SHH-I vs. SHH-II DMB/MBEN

DNA methylation profiling was available for 50 of the 87 patients in this analysis, 28 of whom had infantile sonic hedgehog (SHH)–activated DMB/MBEN. Data from these 28 patients – and 71 patients in a validation cohort – revealed no significant difference in 5-year PFS or OS based on methylation subtype.

The 5-year PFS was 73% in SHH-I patients and 83% in SHH-II patients (P = .25). The 5-year OS was 88% and 97%, respectively (P = .099).

“This suggests that the higher risk of relapse in the less favorable [SHH-I subtype] can be abrogated by the addition of intraventricular [methotrexate] to systemic chemotherapy,” the investigators wrote.

The results suggest SHH-I patients “markedly benefit” from the addition of intraventricular chemotherapy, according to the authors of a related editorial, Giles Robinson, MD, and Amar Gajjar, MD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn.

“However, cross-trial comparison of PFS among the SHH-II subtype does not suggest that SHH-II patients derive the same benefit,” the editorialists wrote.

These data divide SHH medulloblastoma into SHH-I, which benefits from chemotherapy with intraventricular methotrexate, and SHH-II, which can be cured without intraventricular methotrexate, high-dose chemotherapy, or focal radiotherapy, according to the editorialists.

This new information might prompt investigation of a risk-adapted approach. SHH-II patients would receive a reduced-intensity regimen with systemic chemotherapy only, and SHH-I patients would receive systemic chemotherapy combined with intraventricular methotrexate. This could avoid exposing young children to “more intensive therapy than necessary,” according to the editorialists.

Non-WNT/non-SHH disease

Patients with non-WNT/non-SHH medulloblastoma (CMB or LCA) were divided into molecularly defined subtypes group 3 (n = 14) and group 4 (n = 6). The patients in group 3 had lower survival rates than patients in group 4. The 5-year PFS rate was 36% and 83%, respectively (P < .001 ). The 5-year OS rate was 49% and 100%, respectively (P < .001).

“This represents the third recent publication to describe a poor PFS for group 3, and it signals a desperate need for better therapy,” the editorialists wrote. As for the “encouraging” survival rate for group 4 patients, there were only six subjects, which makes this finding “worthy of follow-up but not actionable.”

Even so, the investigators noted that “although poor survival has been reported for non-SHH CMB/LCA in almost every series of patients treated with CSI-sparing approaches, again, use of intraventricular [methotrexate] might be associated with slightly higher PFS, compared with conventional chemotherapy alone.”

As expected, IQ was significantly lower in patients who received CSI salvage. The mean IQ was 74 in patients who received CSI and 90 in patients who did not (P = .012). Neurocognitive outcomes were poor in general among CMB/LCA survivors, “which was closely related to use of radiotherapy,” according to the investigators.

“It is important to recognize that these studies were not designed to define outcome on the basis of molecular subgroup or subtype and that the sample size in all these studies is small,” Dr. Robinson and Dr. Gajjar wrote. “Thus, caution should be used when basing any treatment recommendation on these results, and it is our strong-held opinion that any treatment change be done on a well-planned and well-monitored clinical trial.”

This research was supported by the German Childhood Cancer Foundation, Styrian Childhood Cancer Foundation, and other organizations. Dr. Mynarek and colleagues disclosed relationships with Medac, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Bayer, Roche, and numerous other companies. Dr. Robinson disclosed relationships with Eli Lilly, Genentech, and Novartis. Dr. Gajjar reported relationships with Genentech and Kazia Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Mynarek M et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Jun 20;38(18):2028-40.

according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Investigators conducted a prospective trial of 87 children diagnosed with nonmetastatic medulloblastoma before the age of 4 years who were treated from 2001-2011.

At 5 years after diagnosis, the 42 DMB/MBEN patients had a 93% progression-free survival (PFS) rate, a 100% overall survival (OS) rate, and a 93% craniospinal irradiation (CSI)–free survival rate.

“Our results suggest that ... poor outcomes of patients treated with systemic chemotherapy alone can be improved by the addition of intraventricular [methotrexate],” wrote Martin Mynarek, MD, of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Germany), and colleagues.

However, it was a different story for the 45 patients with classic medulloblastoma (CMB) or large-cell/anaplastic medulloblastoma (CLA), in which outcomes are historically worse. At 5 years, the PFS was 37%, the OS was 62%, and the CSI-free survival was 39% in these patients.

In 2006, the CMB and CLA patients started receiving local radiotherapy in addition to chemotherapy and intraventricular methotrexate, but the radiotherapy did not seem to help with their disease.

“Because data suggest no effects, or even adverse effects, of local radiotherapy, additional development of this approach does not seem justified,” the investigators wrote.

“Interestingly, almost all patients with CMB/LCA had distant or combined relapses after local radiotherapy,” they added. “One might speculate that local radiotherapy reduced disease burden of the primary tumor and subclinical metastasis in the posterior fossa, leading to a survival advantage of distant subclinical metastasis over local residues.”

Treatment details

The 87 patients were enrolled in the BIS4 arm of the HIT 2000 trial (NCT00303810), which was designed to test six protocols and identify the optimal approach for treating young patients with medulloblastoma, supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumor, or ependymoma.

Patients started “HIT-SKK” chemotherapy within 2-4 weeks of surgery. They received three cycles of intravenous cyclophosphamide, vincristine, methotrexate (followed by leucovorin rescue after 42 hours), carboplatin, and etoposide, with concomitant intraventricular methotrexate, for a duration of 6 months (Neuro Oncol. 2011 Jun;13[6]:669-79).

Among patients who achieved a complete remission, treatment was ended after two additional cycles of chemotherapy. For other patients, secondary surgery, radiotherapy, and consolidation chemotherapy were recommended.

Starting in 2006, DMB and MBEN patients without complete remissions, as well as those with CMB or LCA, received 54 Gy of focal radiotherapy to the tumor bed after the first three treatment cycles.

SHH-I vs. SHH-II DMB/MBEN

DNA methylation profiling was available for 50 of the 87 patients in this analysis, 28 of whom had infantile sonic hedgehog (SHH)–activated DMB/MBEN. Data from these 28 patients – and 71 patients in a validation cohort – revealed no significant difference in 5-year PFS or OS based on methylation subtype.

The 5-year PFS was 73% in SHH-I patients and 83% in SHH-II patients (P = .25). The 5-year OS was 88% and 97%, respectively (P = .099).

“This suggests that the higher risk of relapse in the less favorable [SHH-I subtype] can be abrogated by the addition of intraventricular [methotrexate] to systemic chemotherapy,” the investigators wrote.

The results suggest SHH-I patients “markedly benefit” from the addition of intraventricular chemotherapy, according to the authors of a related editorial, Giles Robinson, MD, and Amar Gajjar, MD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn.

“However, cross-trial comparison of PFS among the SHH-II subtype does not suggest that SHH-II patients derive the same benefit,” the editorialists wrote.

These data divide SHH medulloblastoma into SHH-I, which benefits from chemotherapy with intraventricular methotrexate, and SHH-II, which can be cured without intraventricular methotrexate, high-dose chemotherapy, or focal radiotherapy, according to the editorialists.

This new information might prompt investigation of a risk-adapted approach. SHH-II patients would receive a reduced-intensity regimen with systemic chemotherapy only, and SHH-I patients would receive systemic chemotherapy combined with intraventricular methotrexate. This could avoid exposing young children to “more intensive therapy than necessary,” according to the editorialists.

Non-WNT/non-SHH disease

Patients with non-WNT/non-SHH medulloblastoma (CMB or LCA) were divided into molecularly defined subtypes group 3 (n = 14) and group 4 (n = 6). The patients in group 3 had lower survival rates than patients in group 4. The 5-year PFS rate was 36% and 83%, respectively (P < .001 ). The 5-year OS rate was 49% and 100%, respectively (P < .001).

“This represents the third recent publication to describe a poor PFS for group 3, and it signals a desperate need for better therapy,” the editorialists wrote. As for the “encouraging” survival rate for group 4 patients, there were only six subjects, which makes this finding “worthy of follow-up but not actionable.”

Even so, the investigators noted that “although poor survival has been reported for non-SHH CMB/LCA in almost every series of patients treated with CSI-sparing approaches, again, use of intraventricular [methotrexate] might be associated with slightly higher PFS, compared with conventional chemotherapy alone.”

As expected, IQ was significantly lower in patients who received CSI salvage. The mean IQ was 74 in patients who received CSI and 90 in patients who did not (P = .012). Neurocognitive outcomes were poor in general among CMB/LCA survivors, “which was closely related to use of radiotherapy,” according to the investigators.

“It is important to recognize that these studies were not designed to define outcome on the basis of molecular subgroup or subtype and that the sample size in all these studies is small,” Dr. Robinson and Dr. Gajjar wrote. “Thus, caution should be used when basing any treatment recommendation on these results, and it is our strong-held opinion that any treatment change be done on a well-planned and well-monitored clinical trial.”

This research was supported by the German Childhood Cancer Foundation, Styrian Childhood Cancer Foundation, and other organizations. Dr. Mynarek and colleagues disclosed relationships with Medac, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Bayer, Roche, and numerous other companies. Dr. Robinson disclosed relationships with Eli Lilly, Genentech, and Novartis. Dr. Gajjar reported relationships with Genentech and Kazia Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Mynarek M et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Jun 20;38(18):2028-40.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Rilzabrutinib shows positive results in phase 2b for pemphigus

accompanied by markedly reduced need for systemic corticosteroids in the phase 2b BELIEVE-PV trial, Dedee F. Murrell, MD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Moreover, in sharp contrast to the standard first-line treatments for pemphigus – rituximab (Rituxan) and high-dose corticosteroids – the treatment-emergent adverse events that arose with 6 months of rilzabrutinib in BELIEVE-PV were uniformly mild to moderate and transient, added Dr. Murrell, professor of dermatology at the University of New South Wales and head of the department of dermatology at St. George University Hospital, Sydney.

The phase 2b BELIEVE-PV trial was a small, 24-week, open-label study that included six patients with newly diagnosed pemphigus and nine others with relapsing pemphigus. The primary endpoint was control of disease activity, defined as no new lesions appearing and established lesions beginning to heal. This was achieved in 9 of 15 patients (60%) at 4 weeks and in 13 patients by week 12. Meanwhile, the mean daily dose of prednisone fell from 21 mg at baseline to 6 mg at 24 weeks.

The mean score on the Pemphigus Disease Area Index (PDAI) dropped by 79% from a baseline of 15.5. Ten of 15 subjects improved to a PDAI of 0 or 1 – clear or almost clear skin – by week 24. The complete remission rate, defined as an absence of both new and established lesions while on no or a very low dose of prednisone, was 40% at week 24.

Treatment-emergent adverse events consisted of nausea in four patients, dizziness in two, and abdominal distension in two, all of which were grade 1 or 2.

Based upon these favorable results, the pivotal phase 3, double-blind, international PEGASUS trial is underway, led by Dr. Murrell. The trial will enroll 120 pemphigus patients, randomized to rilzabrutinib at 400 mg twice daily or placebo on top of background steroid tapering.

Rilzabrutinib is also in earlier-stage clinical trials for the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia.

Dr. Murrell reported serving as a consultant to Principia Biopharma, sponsor of the BELIEVE-PV and PEGASUS trials, and has received institutional research grants from numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Murrell DF. AAD 2020 LBCT.

accompanied by markedly reduced need for systemic corticosteroids in the phase 2b BELIEVE-PV trial, Dedee F. Murrell, MD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Moreover, in sharp contrast to the standard first-line treatments for pemphigus – rituximab (Rituxan) and high-dose corticosteroids – the treatment-emergent adverse events that arose with 6 months of rilzabrutinib in BELIEVE-PV were uniformly mild to moderate and transient, added Dr. Murrell, professor of dermatology at the University of New South Wales and head of the department of dermatology at St. George University Hospital, Sydney.

The phase 2b BELIEVE-PV trial was a small, 24-week, open-label study that included six patients with newly diagnosed pemphigus and nine others with relapsing pemphigus. The primary endpoint was control of disease activity, defined as no new lesions appearing and established lesions beginning to heal. This was achieved in 9 of 15 patients (60%) at 4 weeks and in 13 patients by week 12. Meanwhile, the mean daily dose of prednisone fell from 21 mg at baseline to 6 mg at 24 weeks.

The mean score on the Pemphigus Disease Area Index (PDAI) dropped by 79% from a baseline of 15.5. Ten of 15 subjects improved to a PDAI of 0 or 1 – clear or almost clear skin – by week 24. The complete remission rate, defined as an absence of both new and established lesions while on no or a very low dose of prednisone, was 40% at week 24.

Treatment-emergent adverse events consisted of nausea in four patients, dizziness in two, and abdominal distension in two, all of which were grade 1 or 2.

Based upon these favorable results, the pivotal phase 3, double-blind, international PEGASUS trial is underway, led by Dr. Murrell. The trial will enroll 120 pemphigus patients, randomized to rilzabrutinib at 400 mg twice daily or placebo on top of background steroid tapering.

Rilzabrutinib is also in earlier-stage clinical trials for the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia.

Dr. Murrell reported serving as a consultant to Principia Biopharma, sponsor of the BELIEVE-PV and PEGASUS trials, and has received institutional research grants from numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Murrell DF. AAD 2020 LBCT.

accompanied by markedly reduced need for systemic corticosteroids in the phase 2b BELIEVE-PV trial, Dedee F. Murrell, MD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Moreover, in sharp contrast to the standard first-line treatments for pemphigus – rituximab (Rituxan) and high-dose corticosteroids – the treatment-emergent adverse events that arose with 6 months of rilzabrutinib in BELIEVE-PV were uniformly mild to moderate and transient, added Dr. Murrell, professor of dermatology at the University of New South Wales and head of the department of dermatology at St. George University Hospital, Sydney.

The phase 2b BELIEVE-PV trial was a small, 24-week, open-label study that included six patients with newly diagnosed pemphigus and nine others with relapsing pemphigus. The primary endpoint was control of disease activity, defined as no new lesions appearing and established lesions beginning to heal. This was achieved in 9 of 15 patients (60%) at 4 weeks and in 13 patients by week 12. Meanwhile, the mean daily dose of prednisone fell from 21 mg at baseline to 6 mg at 24 weeks.

The mean score on the Pemphigus Disease Area Index (PDAI) dropped by 79% from a baseline of 15.5. Ten of 15 subjects improved to a PDAI of 0 or 1 – clear or almost clear skin – by week 24. The complete remission rate, defined as an absence of both new and established lesions while on no or a very low dose of prednisone, was 40% at week 24.

Treatment-emergent adverse events consisted of nausea in four patients, dizziness in two, and abdominal distension in two, all of which were grade 1 or 2.

Based upon these favorable results, the pivotal phase 3, double-blind, international PEGASUS trial is underway, led by Dr. Murrell. The trial will enroll 120 pemphigus patients, randomized to rilzabrutinib at 400 mg twice daily or placebo on top of background steroid tapering.

Rilzabrutinib is also in earlier-stage clinical trials for the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia.

Dr. Murrell reported serving as a consultant to Principia Biopharma, sponsor of the BELIEVE-PV and PEGASUS trials, and has received institutional research grants from numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Murrell DF. AAD 2020 LBCT.

FROM AAD 20

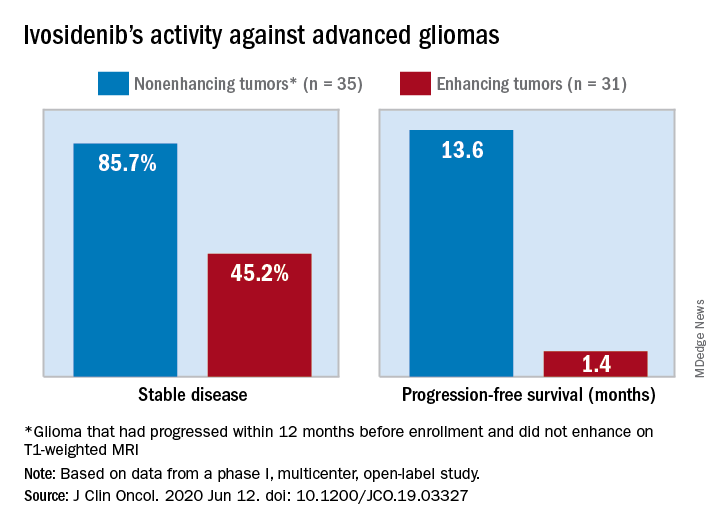

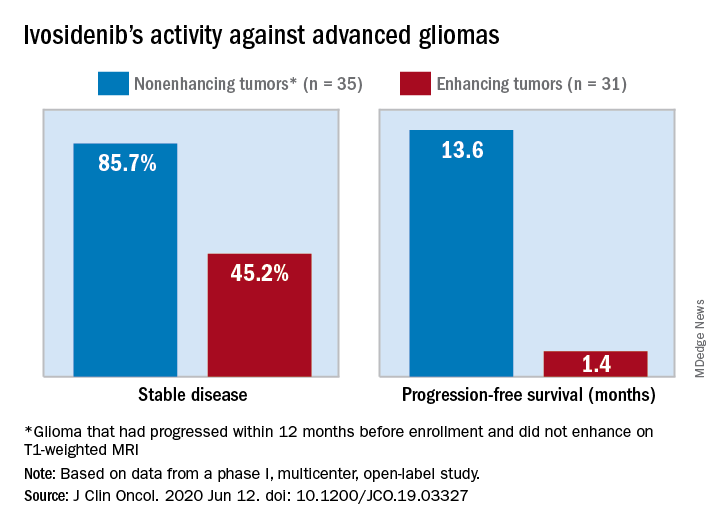

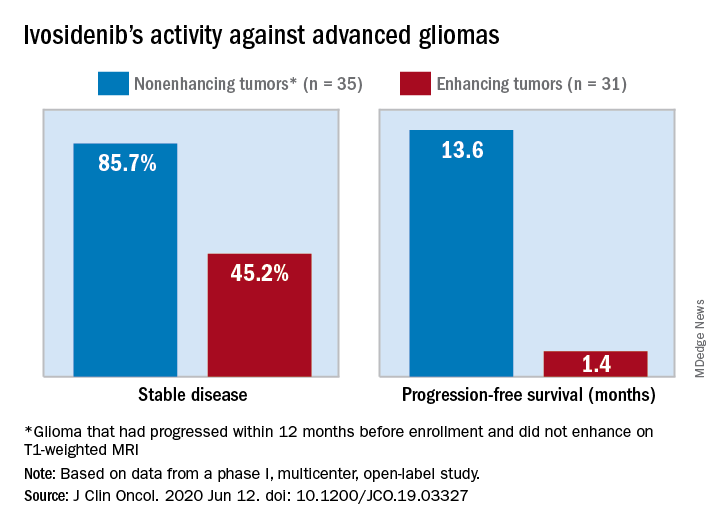

Early data support further study of ivosidenib in mIDH1 glioma

The median progression-free survival was 13.6 months for patients with nonenhancing tumors and 1.4 months for patients with enhancing tumors in a study of 66 adults with mIDH1 advanced glioma.

“On the basis of these data, additional clinical development of mIDH inhibitors for mIDH low-grade gliomas is warranted,” Ingo Mellinghoff, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, and colleagues wrote in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“This is not a home run but is of interest to the community,” said Lawrence Recht, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, who was not involved in this study. “Other companies are also developing agents like this.”

Considering that the ivosidenib study “is uncontrolled, one cannot say for sure that this wasn’t just the natural history of the disease,” Dr. Recht continued. “This type of tumor can behave very indolently, and patients can survive years without treatment, so this is rather a short interval to make a long-time statement. I think the authors are a bit overenthusiastic.”

The authors tested ivosidenib in 66 adults with mIDH1 glioma – 35 with nonenhancing glioma and 31 with enhancing glioma. Tumors had recurred after, or did not respond to, initial surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy.

The patients’ median age was 41 years (range, 21-71 years), and 25 patients (37.9%) were women. The most common tumor type at screening was oligodendroglioma in 23 patients (34.8%).

Patients received ivosidenib at doses ranging from 100 mg twice a day to 900 mg once a day. A total of 50 patients received the phase 2 recommended dose – 500 mg once a day. There were no dose-limiting toxicities, and there was no maximum-tolerated dose.

Adverse events of grade 3 or higher occurred in 19.7% of patients and included headache, seizure, hyperglycemia, neutropenia, and hypophosphatemia. Grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events occurred in two patients.

A total of 30 patients with nonenhancing tumors (85.7%) and 14 with enhancing tumors (45.2%) had a best response of stable disease. There was one partial response in a nonenhancing patient on 500 mg/day. The rest of the subjects had a best response of progressive disease.

The median treatment duration was 18.4 months among patients with nonenhancing tumors and 1.9 months among those with enhancing tumors. Discontinuation was caused byo progression in all but one case.

Among patients with measurable disease, tumor measurements decreased from baseline in 22 nonenhancing tumors (66.7%) and in 9 enhancing tumors (33.3%).

“Despite the heterogeneous patient population in our trial, the nonrandomized design, and the lack of central pathology review, the data from our trial suggest that ivosidenib has greater activity against nonenhancing gliomas than against enhancing gliomas,” the investigators wrote. “This finding may seem surprising because the absence of contrast enhancement is typically associated with impaired drug delivery.

“We hypothesize that ivosidenib may be more effective in nonenhancing gliomas because these tumors represent an earlier disease stage with fewer genetic alterations, reminiscent of the greater antitumor activity of the BCR-ABL inhibitor imatinib in earlier stages of chronic myeloid leukemia,” the investigators wrote.

The team also noted that the median progression-free survival for patients with nonenhancing gliomas in the current study “compares favorably to that reported for temozolomide” in advanced mIDH1 low-grade glioma, which was approximately 7 months.

This research was funded by Agios Pharmaceuticals, the company developing ivosidenib. Dr. Mellinghoff receives travel compensation from and is an adviser to the company. Several other investigators are employees. Dr. Recht disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mellinghoff I et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Jun 12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03327

The median progression-free survival was 13.6 months for patients with nonenhancing tumors and 1.4 months for patients with enhancing tumors in a study of 66 adults with mIDH1 advanced glioma.

“On the basis of these data, additional clinical development of mIDH inhibitors for mIDH low-grade gliomas is warranted,” Ingo Mellinghoff, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, and colleagues wrote in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“This is not a home run but is of interest to the community,” said Lawrence Recht, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, who was not involved in this study. “Other companies are also developing agents like this.”

Considering that the ivosidenib study “is uncontrolled, one cannot say for sure that this wasn’t just the natural history of the disease,” Dr. Recht continued. “This type of tumor can behave very indolently, and patients can survive years without treatment, so this is rather a short interval to make a long-time statement. I think the authors are a bit overenthusiastic.”

The authors tested ivosidenib in 66 adults with mIDH1 glioma – 35 with nonenhancing glioma and 31 with enhancing glioma. Tumors had recurred after, or did not respond to, initial surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy.

The patients’ median age was 41 years (range, 21-71 years), and 25 patients (37.9%) were women. The most common tumor type at screening was oligodendroglioma in 23 patients (34.8%).

Patients received ivosidenib at doses ranging from 100 mg twice a day to 900 mg once a day. A total of 50 patients received the phase 2 recommended dose – 500 mg once a day. There were no dose-limiting toxicities, and there was no maximum-tolerated dose.

Adverse events of grade 3 or higher occurred in 19.7% of patients and included headache, seizure, hyperglycemia, neutropenia, and hypophosphatemia. Grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events occurred in two patients.

A total of 30 patients with nonenhancing tumors (85.7%) and 14 with enhancing tumors (45.2%) had a best response of stable disease. There was one partial response in a nonenhancing patient on 500 mg/day. The rest of the subjects had a best response of progressive disease.

The median treatment duration was 18.4 months among patients with nonenhancing tumors and 1.9 months among those with enhancing tumors. Discontinuation was caused byo progression in all but one case.

Among patients with measurable disease, tumor measurements decreased from baseline in 22 nonenhancing tumors (66.7%) and in 9 enhancing tumors (33.3%).

“Despite the heterogeneous patient population in our trial, the nonrandomized design, and the lack of central pathology review, the data from our trial suggest that ivosidenib has greater activity against nonenhancing gliomas than against enhancing gliomas,” the investigators wrote. “This finding may seem surprising because the absence of contrast enhancement is typically associated with impaired drug delivery.

“We hypothesize that ivosidenib may be more effective in nonenhancing gliomas because these tumors represent an earlier disease stage with fewer genetic alterations, reminiscent of the greater antitumor activity of the BCR-ABL inhibitor imatinib in earlier stages of chronic myeloid leukemia,” the investigators wrote.

The team also noted that the median progression-free survival for patients with nonenhancing gliomas in the current study “compares favorably to that reported for temozolomide” in advanced mIDH1 low-grade glioma, which was approximately 7 months.

This research was funded by Agios Pharmaceuticals, the company developing ivosidenib. Dr. Mellinghoff receives travel compensation from and is an adviser to the company. Several other investigators are employees. Dr. Recht disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mellinghoff I et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Jun 12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03327

The median progression-free survival was 13.6 months for patients with nonenhancing tumors and 1.4 months for patients with enhancing tumors in a study of 66 adults with mIDH1 advanced glioma.

“On the basis of these data, additional clinical development of mIDH inhibitors for mIDH low-grade gliomas is warranted,” Ingo Mellinghoff, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, and colleagues wrote in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“This is not a home run but is of interest to the community,” said Lawrence Recht, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, who was not involved in this study. “Other companies are also developing agents like this.”

Considering that the ivosidenib study “is uncontrolled, one cannot say for sure that this wasn’t just the natural history of the disease,” Dr. Recht continued. “This type of tumor can behave very indolently, and patients can survive years without treatment, so this is rather a short interval to make a long-time statement. I think the authors are a bit overenthusiastic.”

The authors tested ivosidenib in 66 adults with mIDH1 glioma – 35 with nonenhancing glioma and 31 with enhancing glioma. Tumors had recurred after, or did not respond to, initial surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy.

The patients’ median age was 41 years (range, 21-71 years), and 25 patients (37.9%) were women. The most common tumor type at screening was oligodendroglioma in 23 patients (34.8%).

Patients received ivosidenib at doses ranging from 100 mg twice a day to 900 mg once a day. A total of 50 patients received the phase 2 recommended dose – 500 mg once a day. There were no dose-limiting toxicities, and there was no maximum-tolerated dose.

Adverse events of grade 3 or higher occurred in 19.7% of patients and included headache, seizure, hyperglycemia, neutropenia, and hypophosphatemia. Grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events occurred in two patients.

A total of 30 patients with nonenhancing tumors (85.7%) and 14 with enhancing tumors (45.2%) had a best response of stable disease. There was one partial response in a nonenhancing patient on 500 mg/day. The rest of the subjects had a best response of progressive disease.

The median treatment duration was 18.4 months among patients with nonenhancing tumors and 1.9 months among those with enhancing tumors. Discontinuation was caused byo progression in all but one case.

Among patients with measurable disease, tumor measurements decreased from baseline in 22 nonenhancing tumors (66.7%) and in 9 enhancing tumors (33.3%).

“Despite the heterogeneous patient population in our trial, the nonrandomized design, and the lack of central pathology review, the data from our trial suggest that ivosidenib has greater activity against nonenhancing gliomas than against enhancing gliomas,” the investigators wrote. “This finding may seem surprising because the absence of contrast enhancement is typically associated with impaired drug delivery.

“We hypothesize that ivosidenib may be more effective in nonenhancing gliomas because these tumors represent an earlier disease stage with fewer genetic alterations, reminiscent of the greater antitumor activity of the BCR-ABL inhibitor imatinib in earlier stages of chronic myeloid leukemia,” the investigators wrote.

The team also noted that the median progression-free survival for patients with nonenhancing gliomas in the current study “compares favorably to that reported for temozolomide” in advanced mIDH1 low-grade glioma, which was approximately 7 months.

This research was funded by Agios Pharmaceuticals, the company developing ivosidenib. Dr. Mellinghoff receives travel compensation from and is an adviser to the company. Several other investigators are employees. Dr. Recht disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mellinghoff I et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Jun 12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03327

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

One-week postsurgical interval for voiding trial increases pass rate

Women who underwent vaginal prolapse surgery and did not immediately have a successful voiding trial were seven times more likely to pass their second voiding trial if their follow-up was 7 days after surgery instead of 4 days, according to a study in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“This information is useful for setting expectations and for counseling patients on when it might be best to repeat a voiding trial in those with transient incomplete bladder emptying on the day of surgery, especially for those who may not live close to their surgeon, or for those who have difficulty traveling to the office,” said Jeffrey S. Schachar, MD, of Wake Forest Baptist Health in Winston-Salem, N.C., and colleagues. “Despite a higher rate of initial unsuccessful office voiding trials, however, the early group did have significantly fewer days with an indwelling transurethral catheter, as well as total catheterization days,” including self-catheterization.

The researchers note that rates of temporary use of catheters after surgery vary widely, from 12% to 83%, likely because no consensus exists on how long to wait for voiding trials and what constitutes a successful trial.

“It is critical to identify patients with incomplete bladder emptying in order to prevent pain, myogenic and neurogenic damage, ureteral reflux and bladder overdistension that may further impair voiding function,” the authors wrote. “However, extending bladder drainage beyond the necessary recovery period may be associated with higher rates of urinary tract infection (UTI) and patient bother.”

To learn more about the best duration for postoperative catheter use, the researchers enrolled 102 patients before they underwent vaginal prolapse surgery at Wake Forest Baptist Health and Cleveland Clinic Florida from February 2017 to November 2019. The 29 patients with a successful voiding trial within 6 hours after surgery left the study, and 5 others were excluded for needing longer vaginal packing.

The voiding trial involved helping the patient stand to drain the bladder via the catheter, backfilling the bladder with 300 mL of saline solution through the catheter, removing the catheter to give women 1 hour to urinate, and then measuring the postvoid residual with a catheter or ultrasound. At least 100 mL postvoid residual was considered persistent incomplete bladder emptying.

The 60 remaining patients who did not pass the initial voiding trial and opted to remain in the study received a transurethral indwelling catheter and were randomly assigned to return for a second voiding trial either 2-4 days after surgery (depending on day of the week) or 7 days after surgery. The groups were demographically and clinically similar, with predominantly white postmenopausal, non-smoking women with stage II or III multicompartment pelvic organ prolapse.

Women without successful trials could continue with the transurethral catheter or give themselves intermittent catheterizations with a follow-up schedule determined by their surgeon. The researchers then tracked the women for 6 weeks to determine the rate of unsuccessful repeat voiding trials.

Among the women who returned 2-4 days post surgery, 23% had unsuccessful follow-up voiding trials, compared with 3% in the group returning 7 days after surgery (relative risk = 7; P = .02). The researchers calculated that one case of persistent postoperative incomplete bladder emptying was prevented for every five patients who used a catheter for 7 days after surgery.

Kevin A. Ault, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, said the study was well done, although the findings were unsurprising. He said the clinical implication is straightforward – to wait a week before doing a second voiding trial.

“I suspect these findings match the clinical experience of many surgeons. It is always good to see a well-done clinical trial on a topic,” Dr Ault said in an interview. “The most notable finding is how this impacts patient counseling. Gynecologists should tell their patients that it will take a week with a catheter when this problem arises.”

“The main limitation is whether this finding can be extrapolated to other gynecological surgeries, such as hysterectomy,” said Dr. Ault, who was not involved in the study. “Urinary retention is likely less common after that surgery, but it is still bothersome to patients.”

Dr. Schachar and associates also reported that patients in the earlier group “used significantly more morphine dose equivalents within 24 hours of the office voiding trial than the late-voiding trial group, which was expected given the proximity to surgery” (3 vs. 0.38; P = .005). However, new postoperative pain medication prescriptions and refills were similar in both groups.

Secondary endpoints included UTI rates, total days with a catheter, and patient experience of discomfort with the catheter. The two groups of women reported similar levels of catheter bother, but there was a nonsignificant difference in UTI rates: 23% in the earlier group, compared with 7% in the later group (P = .07).

The early-voiding trial group had an average 5 days with an indwelling transurethral catheter, compared with a significantly different 7 days in the later group (P = .0007). The early group also had fewer total days with an indwelling transurethral catheter and self-catheterization (6 days), compared with the late group (7 days; P = .0013). No patients had persistent incomplete bladder emptying after 17 days post surgery.

“Being able to adequately predict which patients are more likely to have unsuccessful postoperative voiding trials allows surgeons to better counsel their patients and may guide clinical decisions,” Dr. Schachar and associates said. They acknowledged, however, that their study’s biggest weakness is the small enrollment, which led to larger confidence intervals related to relative risk differences between the groups.

The study did not use external funding. Four of the investigators received grant, research funding, or honoraria from one or many medical device or pharmaceutical companies. The remaining researchers had no disclosures. Dr. Ault said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Schachar JS et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.001.

Women who underwent vaginal prolapse surgery and did not immediately have a successful voiding trial were seven times more likely to pass their second voiding trial if their follow-up was 7 days after surgery instead of 4 days, according to a study in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“This information is useful for setting expectations and for counseling patients on when it might be best to repeat a voiding trial in those with transient incomplete bladder emptying on the day of surgery, especially for those who may not live close to their surgeon, or for those who have difficulty traveling to the office,” said Jeffrey S. Schachar, MD, of Wake Forest Baptist Health in Winston-Salem, N.C., and colleagues. “Despite a higher rate of initial unsuccessful office voiding trials, however, the early group did have significantly fewer days with an indwelling transurethral catheter, as well as total catheterization days,” including self-catheterization.

The researchers note that rates of temporary use of catheters after surgery vary widely, from 12% to 83%, likely because no consensus exists on how long to wait for voiding trials and what constitutes a successful trial.

“It is critical to identify patients with incomplete bladder emptying in order to prevent pain, myogenic and neurogenic damage, ureteral reflux and bladder overdistension that may further impair voiding function,” the authors wrote. “However, extending bladder drainage beyond the necessary recovery period may be associated with higher rates of urinary tract infection (UTI) and patient bother.”

To learn more about the best duration for postoperative catheter use, the researchers enrolled 102 patients before they underwent vaginal prolapse surgery at Wake Forest Baptist Health and Cleveland Clinic Florida from February 2017 to November 2019. The 29 patients with a successful voiding trial within 6 hours after surgery left the study, and 5 others were excluded for needing longer vaginal packing.

The voiding trial involved helping the patient stand to drain the bladder via the catheter, backfilling the bladder with 300 mL of saline solution through the catheter, removing the catheter to give women 1 hour to urinate, and then measuring the postvoid residual with a catheter or ultrasound. At least 100 mL postvoid residual was considered persistent incomplete bladder emptying.

The 60 remaining patients who did not pass the initial voiding trial and opted to remain in the study received a transurethral indwelling catheter and were randomly assigned to return for a second voiding trial either 2-4 days after surgery (depending on day of the week) or 7 days after surgery. The groups were demographically and clinically similar, with predominantly white postmenopausal, non-smoking women with stage II or III multicompartment pelvic organ prolapse.

Women without successful trials could continue with the transurethral catheter or give themselves intermittent catheterizations with a follow-up schedule determined by their surgeon. The researchers then tracked the women for 6 weeks to determine the rate of unsuccessful repeat voiding trials.

Among the women who returned 2-4 days post surgery, 23% had unsuccessful follow-up voiding trials, compared with 3% in the group returning 7 days after surgery (relative risk = 7; P = .02). The researchers calculated that one case of persistent postoperative incomplete bladder emptying was prevented for every five patients who used a catheter for 7 days after surgery.

Kevin A. Ault, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, said the study was well done, although the findings were unsurprising. He said the clinical implication is straightforward – to wait a week before doing a second voiding trial.

“I suspect these findings match the clinical experience of many surgeons. It is always good to see a well-done clinical trial on a topic,” Dr Ault said in an interview. “The most notable finding is how this impacts patient counseling. Gynecologists should tell their patients that it will take a week with a catheter when this problem arises.”

“The main limitation is whether this finding can be extrapolated to other gynecological surgeries, such as hysterectomy,” said Dr. Ault, who was not involved in the study. “Urinary retention is likely less common after that surgery, but it is still bothersome to patients.”

Dr. Schachar and associates also reported that patients in the earlier group “used significantly more morphine dose equivalents within 24 hours of the office voiding trial than the late-voiding trial group, which was expected given the proximity to surgery” (3 vs. 0.38; P = .005). However, new postoperative pain medication prescriptions and refills were similar in both groups.

Secondary endpoints included UTI rates, total days with a catheter, and patient experience of discomfort with the catheter. The two groups of women reported similar levels of catheter bother, but there was a nonsignificant difference in UTI rates: 23% in the earlier group, compared with 7% in the later group (P = .07).

The early-voiding trial group had an average 5 days with an indwelling transurethral catheter, compared with a significantly different 7 days in the later group (P = .0007). The early group also had fewer total days with an indwelling transurethral catheter and self-catheterization (6 days), compared with the late group (7 days; P = .0013). No patients had persistent incomplete bladder emptying after 17 days post surgery.

“Being able to adequately predict which patients are more likely to have unsuccessful postoperative voiding trials allows surgeons to better counsel their patients and may guide clinical decisions,” Dr. Schachar and associates said. They acknowledged, however, that their study’s biggest weakness is the small enrollment, which led to larger confidence intervals related to relative risk differences between the groups.

The study did not use external funding. Four of the investigators received grant, research funding, or honoraria from one or many medical device or pharmaceutical companies. The remaining researchers had no disclosures. Dr. Ault said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Schachar JS et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.001.

Women who underwent vaginal prolapse surgery and did not immediately have a successful voiding trial were seven times more likely to pass their second voiding trial if their follow-up was 7 days after surgery instead of 4 days, according to a study in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“This information is useful for setting expectations and for counseling patients on when it might be best to repeat a voiding trial in those with transient incomplete bladder emptying on the day of surgery, especially for those who may not live close to their surgeon, or for those who have difficulty traveling to the office,” said Jeffrey S. Schachar, MD, of Wake Forest Baptist Health in Winston-Salem, N.C., and colleagues. “Despite a higher rate of initial unsuccessful office voiding trials, however, the early group did have significantly fewer days with an indwelling transurethral catheter, as well as total catheterization days,” including self-catheterization.

The researchers note that rates of temporary use of catheters after surgery vary widely, from 12% to 83%, likely because no consensus exists on how long to wait for voiding trials and what constitutes a successful trial.

“It is critical to identify patients with incomplete bladder emptying in order to prevent pain, myogenic and neurogenic damage, ureteral reflux and bladder overdistension that may further impair voiding function,” the authors wrote. “However, extending bladder drainage beyond the necessary recovery period may be associated with higher rates of urinary tract infection (UTI) and patient bother.”

To learn more about the best duration for postoperative catheter use, the researchers enrolled 102 patients before they underwent vaginal prolapse surgery at Wake Forest Baptist Health and Cleveland Clinic Florida from February 2017 to November 2019. The 29 patients with a successful voiding trial within 6 hours after surgery left the study, and 5 others were excluded for needing longer vaginal packing.

The voiding trial involved helping the patient stand to drain the bladder via the catheter, backfilling the bladder with 300 mL of saline solution through the catheter, removing the catheter to give women 1 hour to urinate, and then measuring the postvoid residual with a catheter or ultrasound. At least 100 mL postvoid residual was considered persistent incomplete bladder emptying.

The 60 remaining patients who did not pass the initial voiding trial and opted to remain in the study received a transurethral indwelling catheter and were randomly assigned to return for a second voiding trial either 2-4 days after surgery (depending on day of the week) or 7 days after surgery. The groups were demographically and clinically similar, with predominantly white postmenopausal, non-smoking women with stage II or III multicompartment pelvic organ prolapse.

Women without successful trials could continue with the transurethral catheter or give themselves intermittent catheterizations with a follow-up schedule determined by their surgeon. The researchers then tracked the women for 6 weeks to determine the rate of unsuccessful repeat voiding trials.

Among the women who returned 2-4 days post surgery, 23% had unsuccessful follow-up voiding trials, compared with 3% in the group returning 7 days after surgery (relative risk = 7; P = .02). The researchers calculated that one case of persistent postoperative incomplete bladder emptying was prevented for every five patients who used a catheter for 7 days after surgery.

Kevin A. Ault, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, said the study was well done, although the findings were unsurprising. He said the clinical implication is straightforward – to wait a week before doing a second voiding trial.

“I suspect these findings match the clinical experience of many surgeons. It is always good to see a well-done clinical trial on a topic,” Dr Ault said in an interview. “The most notable finding is how this impacts patient counseling. Gynecologists should tell their patients that it will take a week with a catheter when this problem arises.”

“The main limitation is whether this finding can be extrapolated to other gynecological surgeries, such as hysterectomy,” said Dr. Ault, who was not involved in the study. “Urinary retention is likely less common after that surgery, but it is still bothersome to patients.”

Dr. Schachar and associates also reported that patients in the earlier group “used significantly more morphine dose equivalents within 24 hours of the office voiding trial than the late-voiding trial group, which was expected given the proximity to surgery” (3 vs. 0.38; P = .005). However, new postoperative pain medication prescriptions and refills were similar in both groups.

Secondary endpoints included UTI rates, total days with a catheter, and patient experience of discomfort with the catheter. The two groups of women reported similar levels of catheter bother, but there was a nonsignificant difference in UTI rates: 23% in the earlier group, compared with 7% in the later group (P = .07).

The early-voiding trial group had an average 5 days with an indwelling transurethral catheter, compared with a significantly different 7 days in the later group (P = .0007). The early group also had fewer total days with an indwelling transurethral catheter and self-catheterization (6 days), compared with the late group (7 days; P = .0013). No patients had persistent incomplete bladder emptying after 17 days post surgery.

“Being able to adequately predict which patients are more likely to have unsuccessful postoperative voiding trials allows surgeons to better counsel their patients and may guide clinical decisions,” Dr. Schachar and associates said. They acknowledged, however, that their study’s biggest weakness is the small enrollment, which led to larger confidence intervals related to relative risk differences between the groups.

The study did not use external funding. Four of the investigators received grant, research funding, or honoraria from one or many medical device or pharmaceutical companies. The remaining researchers had no disclosures. Dr. Ault said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Schachar JS et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.001.

FROM AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Bigotry and medical injustice

“We cannot teach people to withhold judgment; judgments are embedded in the way we view objects. I do not see a “tree”; I see a pleasant or an ugly tree. It is not possible without great, paralyzing effort to strip these small values we attach to matters. Likewise, it is not possible to hold a situation in one’s head without some element of bias” – Nassim Nicholas Taleb, MBA, PhD, “The Black Swan.”

Each morning I see the hungry ghosts congregate at the end of the alley behind my office waiting for their addiction clinic appointments (Maté G. “In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts, Close Encounters with Addiction” Berkeley, Calif.: North Atlantic Books, 2008). The fast food restaurant and the convenience store won’t let them linger, so there they sit on the curb in the saddest magpie’s row in the world. They have lip, nose, and eyebrow piercings, and lightning bolts tattooed up their cheeks. They all have backpacks, a few even rolling suitcases. They are opioid addicts, and almost all young, White adults. There they sit, once-innocent young girls, now worn and hardened, and vicious-looking young men, all with downcast empty eyes and miserable expressions. They are a frightening group marginalized by their addiction.

Opioid addiction became a national focus of attention with clarion calls for treatment, which resulted in legislative funding for treatment, restrictions on prescribing, and readily available Narcan. Physicians have greatly reduced their prescribing of narcotics and overdose death rates have dropped, but the drug crisis has not gone away, it has only been recently overshadowed by COVID-19.

The most ironic part of the current opioid epidemic and overdose deaths, and the other three bloodborne horsemen of death – endocarditis; hepatitis B, C, and D; and HIV – was that these scourges were affecting the Black community 40 years ago when, in my view, no one seemed to care. There was no addiction counseling, no treatment centers, and law enforcement would visit only with hopes of making a dealer’s arrest. Not until it became a White suburban issue, did this public health problem become recognized as something to act on. This is of course a result of racism, but there is a broader lesson here.

Humans may be naturally bigoted toward any marginalized or minority group. I recall working in the HIV clinic (before it was called HIV) in Dallas in the mid-1980s. The county refused to pay for zidovudine, which was very expensive at the time, and was sued to supply medication for a group marginalized by their sexual orientation. The AIDS epidemic was initially ignored, with the virus spreading to intravenous drug users and eventually to the broader population, which is when effective treatments became a priority.

Physicians and society should pay close attention to the ills of our marginalized communities. Because of isolation from health care, they are the medical canaries in the coal mine for all of us. Medical issues and infectious diseases identified there should be a priority and solutions sought and applied. This not only would benefit the marginalized group and ease their suffering, but would be salutary to society as a whole, because they surely will be coming everyone’s way.

COVID-19 highlights this. The working poor live in close quarters and most rely on crowded public transportation, and so a respiratory illness spreads rapidly in a population that cannot practically physically distance and probably cannot afford face masks, or alcohol hand gel.

As noted above, we have a persistent illegal drug epidemic. We also have a resurgence in venereal disease and tuberculosis, much of it drug resistant, which again is concentrated in our marginalized populations. Meanwhile, we have been cutting spending on public health, while we obviously need more resources devoted to public and community health.

When we step back and look, there are public health issues everywhere. We could eliminate 90% of cervical cancer and most of the oropharyngeal cancer with use of a very effective vaccine, but we struggle to get it paid for and to convince the public of its ultimate good.

Another example is in Ohio, where we raised the age to purchase tobacco to 21, which is laudable. But children of any age can still access tanning beds, which dramatically raises their lifetime risk of melanoma, often using a note from their “parents” that they write for each other on the car hood in the strip mall parking lot. This group of mostly young white women could also be considered a marginalized group despite their disposable income because of their belief in personal invincibility and false impressions of a tan conferring beauty and vitality repeated endlessly in their echo chamber of social media impressions.

Perhaps we should gauge the state of our public health by the health status of the most oppressed group of all, the incarcerated. Is it really possible that we don’t routinely test for and treat hepatitis C in many of our prisons? Is this indifference because the incarcerated are again a largely minority group and hepatitis C is spread by intravenous drug use?

Solutions and interventions for these problems range widely in cost, but all would eventually save the greater society money and alleviate great misery for those affected.

Perhaps we should be talking about the decriminalization of drug use. The drugs are already here and the consequences apparent, including overflowing prisons and out of control gun violence. This is a much thornier discussion, but seems at the root of many of our problems.

Bigotry is insidious and will take a long and continuing active effort to combat. As Dr. Taleb notes in the introductory quote, it requires a constant, tiring, deliberate mental effort to be mindful of one’s biases. As physicians, we have always been careful to try and treat all patients without bias, but this is not enough. We must become more insistent about the funding and application of public health measures.

Recognizing and treating the medical problems of our marginalized populations seems a doable first step while our greater society struggles with mental bias toward marginalized groups. Reducing the health burdens of these groups can only help them in their life struggles and will benefit all.

Someone once told me that the cold wind in the ghetto eventually blows out into the suburbs, and they were right. As physicians and a society, we should be insistent about correcting medical injustices beforehand. Let’s get started.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

“We cannot teach people to withhold judgment; judgments are embedded in the way we view objects. I do not see a “tree”; I see a pleasant or an ugly tree. It is not possible without great, paralyzing effort to strip these small values we attach to matters. Likewise, it is not possible to hold a situation in one’s head without some element of bias” – Nassim Nicholas Taleb, MBA, PhD, “The Black Swan.”

Each morning I see the hungry ghosts congregate at the end of the alley behind my office waiting for their addiction clinic appointments (Maté G. “In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts, Close Encounters with Addiction” Berkeley, Calif.: North Atlantic Books, 2008). The fast food restaurant and the convenience store won’t let them linger, so there they sit on the curb in the saddest magpie’s row in the world. They have lip, nose, and eyebrow piercings, and lightning bolts tattooed up their cheeks. They all have backpacks, a few even rolling suitcases. They are opioid addicts, and almost all young, White adults. There they sit, once-innocent young girls, now worn and hardened, and vicious-looking young men, all with downcast empty eyes and miserable expressions. They are a frightening group marginalized by their addiction.

Opioid addiction became a national focus of attention with clarion calls for treatment, which resulted in legislative funding for treatment, restrictions on prescribing, and readily available Narcan. Physicians have greatly reduced their prescribing of narcotics and overdose death rates have dropped, but the drug crisis has not gone away, it has only been recently overshadowed by COVID-19.

The most ironic part of the current opioid epidemic and overdose deaths, and the other three bloodborne horsemen of death – endocarditis; hepatitis B, C, and D; and HIV – was that these scourges were affecting the Black community 40 years ago when, in my view, no one seemed to care. There was no addiction counseling, no treatment centers, and law enforcement would visit only with hopes of making a dealer’s arrest. Not until it became a White suburban issue, did this public health problem become recognized as something to act on. This is of course a result of racism, but there is a broader lesson here.

Humans may be naturally bigoted toward any marginalized or minority group. I recall working in the HIV clinic (before it was called HIV) in Dallas in the mid-1980s. The county refused to pay for zidovudine, which was very expensive at the time, and was sued to supply medication for a group marginalized by their sexual orientation. The AIDS epidemic was initially ignored, with the virus spreading to intravenous drug users and eventually to the broader population, which is when effective treatments became a priority.

Physicians and society should pay close attention to the ills of our marginalized communities. Because of isolation from health care, they are the medical canaries in the coal mine for all of us. Medical issues and infectious diseases identified there should be a priority and solutions sought and applied. This not only would benefit the marginalized group and ease their suffering, but would be salutary to society as a whole, because they surely will be coming everyone’s way.

COVID-19 highlights this. The working poor live in close quarters and most rely on crowded public transportation, and so a respiratory illness spreads rapidly in a population that cannot practically physically distance and probably cannot afford face masks, or alcohol hand gel.

As noted above, we have a persistent illegal drug epidemic. We also have a resurgence in venereal disease and tuberculosis, much of it drug resistant, which again is concentrated in our marginalized populations. Meanwhile, we have been cutting spending on public health, while we obviously need more resources devoted to public and community health.

When we step back and look, there are public health issues everywhere. We could eliminate 90% of cervical cancer and most of the oropharyngeal cancer with use of a very effective vaccine, but we struggle to get it paid for and to convince the public of its ultimate good.

Another example is in Ohio, where we raised the age to purchase tobacco to 21, which is laudable. But children of any age can still access tanning beds, which dramatically raises their lifetime risk of melanoma, often using a note from their “parents” that they write for each other on the car hood in the strip mall parking lot. This group of mostly young white women could also be considered a marginalized group despite their disposable income because of their belief in personal invincibility and false impressions of a tan conferring beauty and vitality repeated endlessly in their echo chamber of social media impressions.

Perhaps we should gauge the state of our public health by the health status of the most oppressed group of all, the incarcerated. Is it really possible that we don’t routinely test for and treat hepatitis C in many of our prisons? Is this indifference because the incarcerated are again a largely minority group and hepatitis C is spread by intravenous drug use?

Solutions and interventions for these problems range widely in cost, but all would eventually save the greater society money and alleviate great misery for those affected.

Perhaps we should be talking about the decriminalization of drug use. The drugs are already here and the consequences apparent, including overflowing prisons and out of control gun violence. This is a much thornier discussion, but seems at the root of many of our problems.

Bigotry is insidious and will take a long and continuing active effort to combat. As Dr. Taleb notes in the introductory quote, it requires a constant, tiring, deliberate mental effort to be mindful of one’s biases. As physicians, we have always been careful to try and treat all patients without bias, but this is not enough. We must become more insistent about the funding and application of public health measures.

Recognizing and treating the medical problems of our marginalized populations seems a doable first step while our greater society struggles with mental bias toward marginalized groups. Reducing the health burdens of these groups can only help them in their life struggles and will benefit all.

Someone once told me that the cold wind in the ghetto eventually blows out into the suburbs, and they were right. As physicians and a society, we should be insistent about correcting medical injustices beforehand. Let’s get started.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

“We cannot teach people to withhold judgment; judgments are embedded in the way we view objects. I do not see a “tree”; I see a pleasant or an ugly tree. It is not possible without great, paralyzing effort to strip these small values we attach to matters. Likewise, it is not possible to hold a situation in one’s head without some element of bias” – Nassim Nicholas Taleb, MBA, PhD, “The Black Swan.”

Each morning I see the hungry ghosts congregate at the end of the alley behind my office waiting for their addiction clinic appointments (Maté G. “In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts, Close Encounters with Addiction” Berkeley, Calif.: North Atlantic Books, 2008). The fast food restaurant and the convenience store won’t let them linger, so there they sit on the curb in the saddest magpie’s row in the world. They have lip, nose, and eyebrow piercings, and lightning bolts tattooed up their cheeks. They all have backpacks, a few even rolling suitcases. They are opioid addicts, and almost all young, White adults. There they sit, once-innocent young girls, now worn and hardened, and vicious-looking young men, all with downcast empty eyes and miserable expressions. They are a frightening group marginalized by their addiction.

Opioid addiction became a national focus of attention with clarion calls for treatment, which resulted in legislative funding for treatment, restrictions on prescribing, and readily available Narcan. Physicians have greatly reduced their prescribing of narcotics and overdose death rates have dropped, but the drug crisis has not gone away, it has only been recently overshadowed by COVID-19.

The most ironic part of the current opioid epidemic and overdose deaths, and the other three bloodborne horsemen of death – endocarditis; hepatitis B, C, and D; and HIV – was that these scourges were affecting the Black community 40 years ago when, in my view, no one seemed to care. There was no addiction counseling, no treatment centers, and law enforcement would visit only with hopes of making a dealer’s arrest. Not until it became a White suburban issue, did this public health problem become recognized as something to act on. This is of course a result of racism, but there is a broader lesson here.

Humans may be naturally bigoted toward any marginalized or minority group. I recall working in the HIV clinic (before it was called HIV) in Dallas in the mid-1980s. The county refused to pay for zidovudine, which was very expensive at the time, and was sued to supply medication for a group marginalized by their sexual orientation. The AIDS epidemic was initially ignored, with the virus spreading to intravenous drug users and eventually to the broader population, which is when effective treatments became a priority.

Physicians and society should pay close attention to the ills of our marginalized communities. Because of isolation from health care, they are the medical canaries in the coal mine for all of us. Medical issues and infectious diseases identified there should be a priority and solutions sought and applied. This not only would benefit the marginalized group and ease their suffering, but would be salutary to society as a whole, because they surely will be coming everyone’s way.

COVID-19 highlights this. The working poor live in close quarters and most rely on crowded public transportation, and so a respiratory illness spreads rapidly in a population that cannot practically physically distance and probably cannot afford face masks, or alcohol hand gel.

As noted above, we have a persistent illegal drug epidemic. We also have a resurgence in venereal disease and tuberculosis, much of it drug resistant, which again is concentrated in our marginalized populations. Meanwhile, we have been cutting spending on public health, while we obviously need more resources devoted to public and community health.

When we step back and look, there are public health issues everywhere. We could eliminate 90% of cervical cancer and most of the oropharyngeal cancer with use of a very effective vaccine, but we struggle to get it paid for and to convince the public of its ultimate good.

Another example is in Ohio, where we raised the age to purchase tobacco to 21, which is laudable. But children of any age can still access tanning beds, which dramatically raises their lifetime risk of melanoma, often using a note from their “parents” that they write for each other on the car hood in the strip mall parking lot. This group of mostly young white women could also be considered a marginalized group despite their disposable income because of their belief in personal invincibility and false impressions of a tan conferring beauty and vitality repeated endlessly in their echo chamber of social media impressions.

Perhaps we should gauge the state of our public health by the health status of the most oppressed group of all, the incarcerated. Is it really possible that we don’t routinely test for and treat hepatitis C in many of our prisons? Is this indifference because the incarcerated are again a largely minority group and hepatitis C is spread by intravenous drug use?

Solutions and interventions for these problems range widely in cost, but all would eventually save the greater society money and alleviate great misery for those affected.

Perhaps we should be talking about the decriminalization of drug use. The drugs are already here and the consequences apparent, including overflowing prisons and out of control gun violence. This is a much thornier discussion, but seems at the root of many of our problems.

Bigotry is insidious and will take a long and continuing active effort to combat. As Dr. Taleb notes in the introductory quote, it requires a constant, tiring, deliberate mental effort to be mindful of one’s biases. As physicians, we have always been careful to try and treat all patients without bias, but this is not enough. We must become more insistent about the funding and application of public health measures.

Recognizing and treating the medical problems of our marginalized populations seems a doable first step while our greater society struggles with mental bias toward marginalized groups. Reducing the health burdens of these groups can only help them in their life struggles and will benefit all.

Someone once told me that the cold wind in the ghetto eventually blows out into the suburbs, and they were right. As physicians and a society, we should be insistent about correcting medical injustices beforehand. Let’s get started.