User login

DynamX Bioadaptor coronary stent shows promise in pilot study

The DynamX Bioadaptor – arguably the most original concept in coronary stent design to come along in 3 decades – demonstrated excellent safety and efficacy in a 12-month international, proof-of-concept study, Stefan Verheye, MD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“There has been no fundamental change in stent design in over 30 years,” declared Dr. Verheye, codirector of the Antwerp (Belgium) Cardiovascular Center. “The DynamX Bioadaptor is a fundamental innovation in device design.”

The investigational device is a 71-mcm-thick, cobalt-chromium metal platform that elutes novolimus from a biodegradable polymer. Circumferential rings in low-stress sections of the device are held together by polymer connectors, and when the polymer erodes at about 6 months the stent segments are able to disengage from each other while maintaining longitudinal continuity. Dr. Verheye called this process “uncaging” the stented artery. The result is restoration of normal vessel angulation and compliance; the artery is no longer artificially straightened and constrained by a relatively stiff stent. Positive adaptive remodeling is preserved with enhanced vessel pulsatility and maintenance of lumenal area for good blood flow.

Dr. Verheye said the impetus for developing this outside-the-box novel stent platform lies in the recognition of a major unmet need for better drug-eluting stent (DES) performance. “Despite excellent acute outcomes, data with current-generation DES show long-term event rates are high and accrue at a rate of 2%-3% per year without a plateau.”

He was coprincipal investigator for the international study, which included 50 patients who received a DynamX Bioadaptor for a single de novo coronary artery lesion no more than 24 mm in length. The acute performance of the device was similar to that of second-generation DES, with a mean acute gain post procedure of 1.63 mm by quantitative coronary angiography and a mean late lumen loss of 0.12 mm when measured again at 9 or 12 months.

Intravascular ultrasound imaging showed a 3% increase in mean target vessel area and a 5% increase in the stented area from post procedure to 9 or 12 months’ follow-up, with no change in mean lumen area, all of which translates into maintenance of good blood flow over time. In contrast, what typically occurs following implantation of current DES is maintenance of target vessel and device areas, but with a loss in mean lumen area, the cardiologist noted.

There were two cardiac deaths but no cases of target lesion revascularization, device thrombosis, or strut fracture within 12 months of the procedure.

“The Bioadaptor performs similarly to second-generation DES in terms of implantation technique, deliverability, conformability, and radial strength during the healing phase, while showing the promise of mitigating the 2%-3% annualized event rate beyond 1 year,” Dr. Verheye concluded, adding, “Obviously, longer-term follow-up in comparative studies will be needed to show a reduction in the device-oriented events that have been observed with current DES.”

Session cochair Davide Capodanno, MD, PhD, of the University of Catania (Italy), declared: “This is an intriguing device because it’s metal, but it’s a kind of pulsatile metal after the biodegradation of the connectors. It’s something I’ve never seen.”

Discussant William Wijns, MD, PhD, said he was “thrilled” by the innovative aspect of the DynamX Bioadaptor, but he’s a long way from being persuaded that the device’s potential physiological advantages will translate into improved clinical outcomes relative to current DES.

“Don’t we all have a strange feeling of deja vu because all these anticipated benefits are the same as those we were told we would see with fully bioresorbable scaffolds? And we know so much after 10 years of experience with bioresorbable scaffolds that probably we will not accept this great story unless we get more and more evidence,” cautioned Dr. Wijns, professor of interventional cardiology at the National University of Ireland, Galway, and chairman of EuroPCR.

The claim regarding bioresorbable scaffolds was that, even though the acute results weren’t as good as with DES, that disadvantage would be outweighed by superior long-term clinical outcomes. But in fact the long-term outcomes turned out to be worse as well.

“We had to give up immediate results with the bioresorbable scaffolds. I don’t think we want to go that route again this time,” the cardiologist said.

Thus, the first thing that’s needed in order to make a convincing case for the Bioadaptor is evidence from a large, randomized, comparative trial demonstrating that the acute performance of the novel device is noninferior to that of current DES, including data on complex lesions. Such a study was supposed to be underway now but has been delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, he noted.

Once there is evidence that the acute results with the Bioadaptor are truly comparable with those achieved with current DES, there will be a need for long-term data showing that the device reduces the 2%-3% annualized event rate seen with DES beyond 1 year, Dr. Wijns added.

Dr. Verheye reported receiving consultation fees from study sponsor Elixir Medical as well as from Biotronik. Dr. Wijns reported receiving research grants from MicroPort.

The DynamX Bioadaptor – arguably the most original concept in coronary stent design to come along in 3 decades – demonstrated excellent safety and efficacy in a 12-month international, proof-of-concept study, Stefan Verheye, MD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“There has been no fundamental change in stent design in over 30 years,” declared Dr. Verheye, codirector of the Antwerp (Belgium) Cardiovascular Center. “The DynamX Bioadaptor is a fundamental innovation in device design.”

The investigational device is a 71-mcm-thick, cobalt-chromium metal platform that elutes novolimus from a biodegradable polymer. Circumferential rings in low-stress sections of the device are held together by polymer connectors, and when the polymer erodes at about 6 months the stent segments are able to disengage from each other while maintaining longitudinal continuity. Dr. Verheye called this process “uncaging” the stented artery. The result is restoration of normal vessel angulation and compliance; the artery is no longer artificially straightened and constrained by a relatively stiff stent. Positive adaptive remodeling is preserved with enhanced vessel pulsatility and maintenance of lumenal area for good blood flow.

Dr. Verheye said the impetus for developing this outside-the-box novel stent platform lies in the recognition of a major unmet need for better drug-eluting stent (DES) performance. “Despite excellent acute outcomes, data with current-generation DES show long-term event rates are high and accrue at a rate of 2%-3% per year without a plateau.”

He was coprincipal investigator for the international study, which included 50 patients who received a DynamX Bioadaptor for a single de novo coronary artery lesion no more than 24 mm in length. The acute performance of the device was similar to that of second-generation DES, with a mean acute gain post procedure of 1.63 mm by quantitative coronary angiography and a mean late lumen loss of 0.12 mm when measured again at 9 or 12 months.

Intravascular ultrasound imaging showed a 3% increase in mean target vessel area and a 5% increase in the stented area from post procedure to 9 or 12 months’ follow-up, with no change in mean lumen area, all of which translates into maintenance of good blood flow over time. In contrast, what typically occurs following implantation of current DES is maintenance of target vessel and device areas, but with a loss in mean lumen area, the cardiologist noted.

There were two cardiac deaths but no cases of target lesion revascularization, device thrombosis, or strut fracture within 12 months of the procedure.

“The Bioadaptor performs similarly to second-generation DES in terms of implantation technique, deliverability, conformability, and radial strength during the healing phase, while showing the promise of mitigating the 2%-3% annualized event rate beyond 1 year,” Dr. Verheye concluded, adding, “Obviously, longer-term follow-up in comparative studies will be needed to show a reduction in the device-oriented events that have been observed with current DES.”

Session cochair Davide Capodanno, MD, PhD, of the University of Catania (Italy), declared: “This is an intriguing device because it’s metal, but it’s a kind of pulsatile metal after the biodegradation of the connectors. It’s something I’ve never seen.”

Discussant William Wijns, MD, PhD, said he was “thrilled” by the innovative aspect of the DynamX Bioadaptor, but he’s a long way from being persuaded that the device’s potential physiological advantages will translate into improved clinical outcomes relative to current DES.

“Don’t we all have a strange feeling of deja vu because all these anticipated benefits are the same as those we were told we would see with fully bioresorbable scaffolds? And we know so much after 10 years of experience with bioresorbable scaffolds that probably we will not accept this great story unless we get more and more evidence,” cautioned Dr. Wijns, professor of interventional cardiology at the National University of Ireland, Galway, and chairman of EuroPCR.

The claim regarding bioresorbable scaffolds was that, even though the acute results weren’t as good as with DES, that disadvantage would be outweighed by superior long-term clinical outcomes. But in fact the long-term outcomes turned out to be worse as well.

“We had to give up immediate results with the bioresorbable scaffolds. I don’t think we want to go that route again this time,” the cardiologist said.

Thus, the first thing that’s needed in order to make a convincing case for the Bioadaptor is evidence from a large, randomized, comparative trial demonstrating that the acute performance of the novel device is noninferior to that of current DES, including data on complex lesions. Such a study was supposed to be underway now but has been delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, he noted.

Once there is evidence that the acute results with the Bioadaptor are truly comparable with those achieved with current DES, there will be a need for long-term data showing that the device reduces the 2%-3% annualized event rate seen with DES beyond 1 year, Dr. Wijns added.

Dr. Verheye reported receiving consultation fees from study sponsor Elixir Medical as well as from Biotronik. Dr. Wijns reported receiving research grants from MicroPort.

The DynamX Bioadaptor – arguably the most original concept in coronary stent design to come along in 3 decades – demonstrated excellent safety and efficacy in a 12-month international, proof-of-concept study, Stefan Verheye, MD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“There has been no fundamental change in stent design in over 30 years,” declared Dr. Verheye, codirector of the Antwerp (Belgium) Cardiovascular Center. “The DynamX Bioadaptor is a fundamental innovation in device design.”

The investigational device is a 71-mcm-thick, cobalt-chromium metal platform that elutes novolimus from a biodegradable polymer. Circumferential rings in low-stress sections of the device are held together by polymer connectors, and when the polymer erodes at about 6 months the stent segments are able to disengage from each other while maintaining longitudinal continuity. Dr. Verheye called this process “uncaging” the stented artery. The result is restoration of normal vessel angulation and compliance; the artery is no longer artificially straightened and constrained by a relatively stiff stent. Positive adaptive remodeling is preserved with enhanced vessel pulsatility and maintenance of lumenal area for good blood flow.

Dr. Verheye said the impetus for developing this outside-the-box novel stent platform lies in the recognition of a major unmet need for better drug-eluting stent (DES) performance. “Despite excellent acute outcomes, data with current-generation DES show long-term event rates are high and accrue at a rate of 2%-3% per year without a plateau.”

He was coprincipal investigator for the international study, which included 50 patients who received a DynamX Bioadaptor for a single de novo coronary artery lesion no more than 24 mm in length. The acute performance of the device was similar to that of second-generation DES, with a mean acute gain post procedure of 1.63 mm by quantitative coronary angiography and a mean late lumen loss of 0.12 mm when measured again at 9 or 12 months.

Intravascular ultrasound imaging showed a 3% increase in mean target vessel area and a 5% increase in the stented area from post procedure to 9 or 12 months’ follow-up, with no change in mean lumen area, all of which translates into maintenance of good blood flow over time. In contrast, what typically occurs following implantation of current DES is maintenance of target vessel and device areas, but with a loss in mean lumen area, the cardiologist noted.

There were two cardiac deaths but no cases of target lesion revascularization, device thrombosis, or strut fracture within 12 months of the procedure.

“The Bioadaptor performs similarly to second-generation DES in terms of implantation technique, deliverability, conformability, and radial strength during the healing phase, while showing the promise of mitigating the 2%-3% annualized event rate beyond 1 year,” Dr. Verheye concluded, adding, “Obviously, longer-term follow-up in comparative studies will be needed to show a reduction in the device-oriented events that have been observed with current DES.”

Session cochair Davide Capodanno, MD, PhD, of the University of Catania (Italy), declared: “This is an intriguing device because it’s metal, but it’s a kind of pulsatile metal after the biodegradation of the connectors. It’s something I’ve never seen.”

Discussant William Wijns, MD, PhD, said he was “thrilled” by the innovative aspect of the DynamX Bioadaptor, but he’s a long way from being persuaded that the device’s potential physiological advantages will translate into improved clinical outcomes relative to current DES.

“Don’t we all have a strange feeling of deja vu because all these anticipated benefits are the same as those we were told we would see with fully bioresorbable scaffolds? And we know so much after 10 years of experience with bioresorbable scaffolds that probably we will not accept this great story unless we get more and more evidence,” cautioned Dr. Wijns, professor of interventional cardiology at the National University of Ireland, Galway, and chairman of EuroPCR.

The claim regarding bioresorbable scaffolds was that, even though the acute results weren’t as good as with DES, that disadvantage would be outweighed by superior long-term clinical outcomes. But in fact the long-term outcomes turned out to be worse as well.

“We had to give up immediate results with the bioresorbable scaffolds. I don’t think we want to go that route again this time,” the cardiologist said.

Thus, the first thing that’s needed in order to make a convincing case for the Bioadaptor is evidence from a large, randomized, comparative trial demonstrating that the acute performance of the novel device is noninferior to that of current DES, including data on complex lesions. Such a study was supposed to be underway now but has been delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, he noted.

Once there is evidence that the acute results with the Bioadaptor are truly comparable with those achieved with current DES, there will be a need for long-term data showing that the device reduces the 2%-3% annualized event rate seen with DES beyond 1 year, Dr. Wijns added.

Dr. Verheye reported receiving consultation fees from study sponsor Elixir Medical as well as from Biotronik. Dr. Wijns reported receiving research grants from MicroPort.

REPORTING FROM EUROPCR 2020

He Doesn’t Love It Warts and All

ANSWER

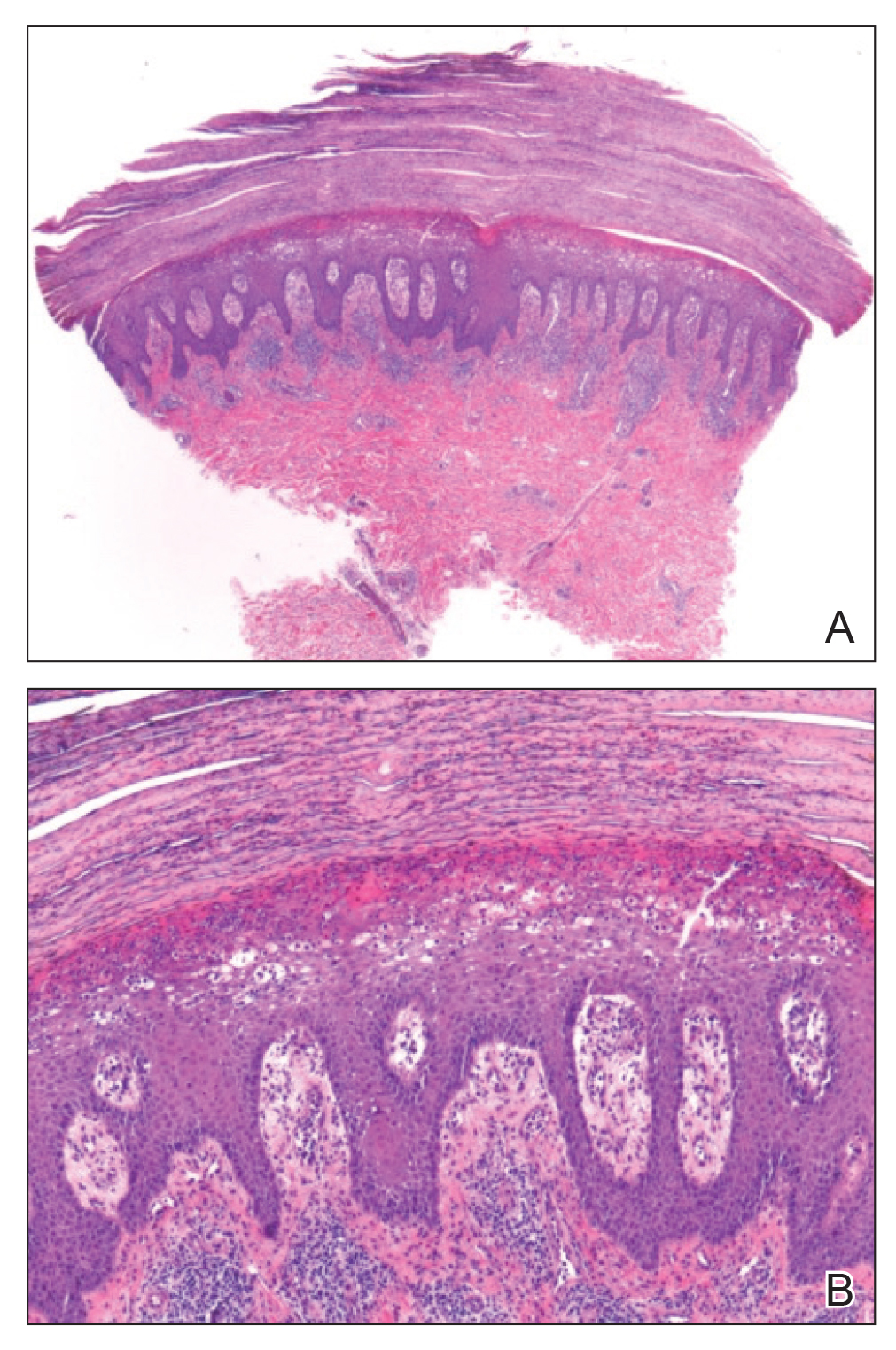

The correct answer is lichen planus (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Condyloma accuminata can demonstrate amazing lability, sometimes appearing decades after exposure. And spouses may not always be truthful when questioned about such exposure. To further confuse the issue, it's entirely possible that a patient may be unaware he or she has condyloma. So, this might well have been condyloma. But the differential for penile lesions would include this condition—and more.

Psoriasis (choice “a”) commonly affects the penis, manifesting as pinkish plaques and papules. But there is a good chance that examination would have revealed corroborative signs of this disease. Furthermore, the histologic results would have been entirely different.

While syphilis (choice “b”), especially in its primary stage, can present with nonhealing sores, in no way do they resemble the patient’s lesions. There is also no source for such an infection. And biopsy would have shown a predominately plasma cell infiltrate in an entirely different pattern.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (choice “d”) is quite uncommon, especially on the penis, where it is usually known as balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO). As its name suggests, BXO is usually atrophic—therefore macular—and whitish. Exclusive to uncircumcised men, it bears no resemblance to condyloma.

Though idiopathic, lichen planus is not contagious. Unless neglected, this condition seldom causes any suffering aside from mental anguish over its appearance. To make a more accurate diagnosis, it is always helpful for providers to consider a mnemonic device for “7 Ps” associated with lichen planus:

- Penile

- Pruritic

- Plaque-like

- Purple

- Papular

- Planar

- Puzzling.

TREATMENT

Fortunately, lichen planus affecting the penis responds readily to treatment with mid-strength topical steroid cream and the "tincture of time," which improves its appearance until it eventually disappears. For this patient, the PCP treated the affected area with triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid for 2 weeks. This was then applied once a day every other day for a month, which cleared the patient’s lesions.

ANSWER

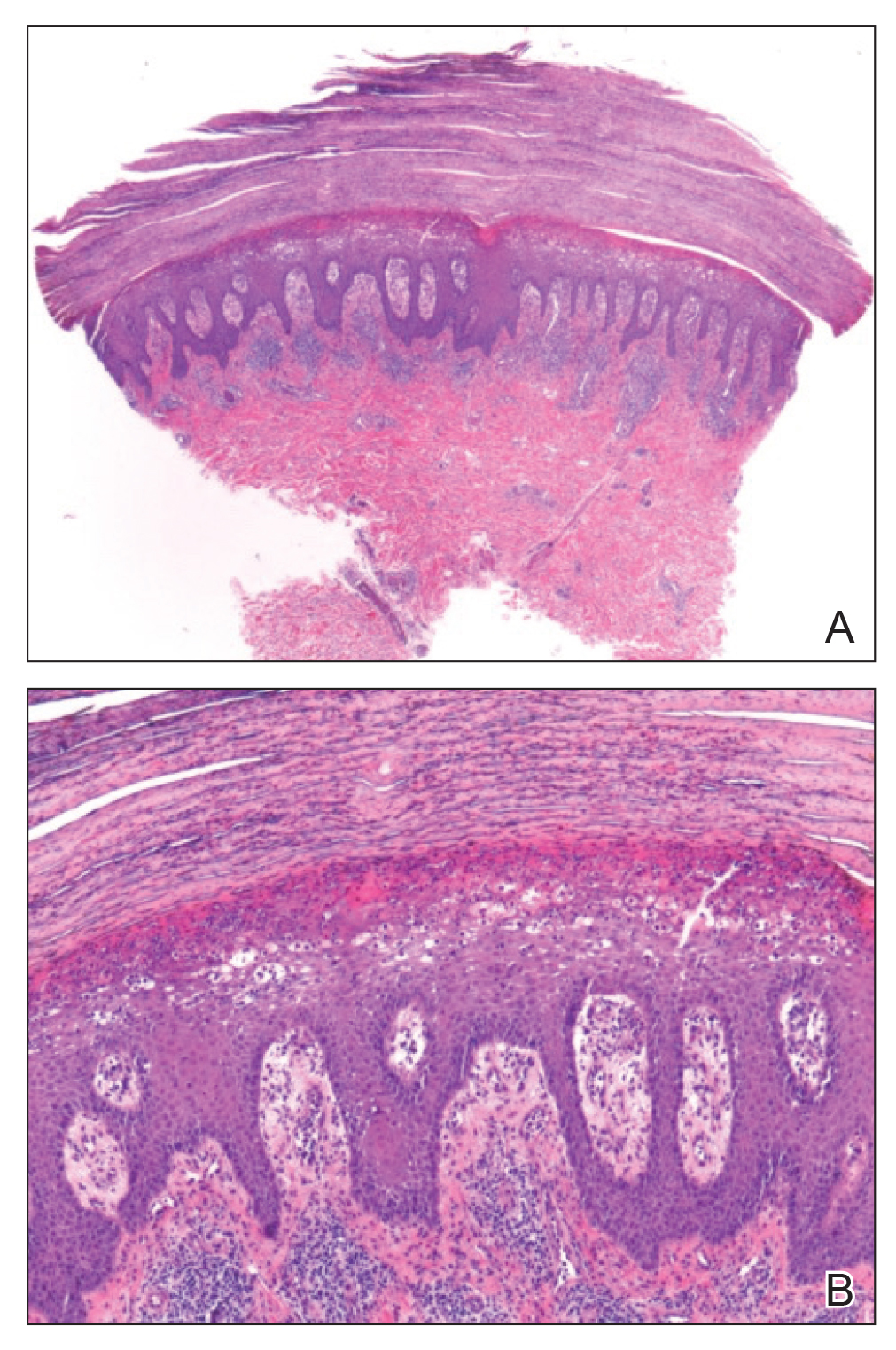

The correct answer is lichen planus (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Condyloma accuminata can demonstrate amazing lability, sometimes appearing decades after exposure. And spouses may not always be truthful when questioned about such exposure. To further confuse the issue, it's entirely possible that a patient may be unaware he or she has condyloma. So, this might well have been condyloma. But the differential for penile lesions would include this condition—and more.

Psoriasis (choice “a”) commonly affects the penis, manifesting as pinkish plaques and papules. But there is a good chance that examination would have revealed corroborative signs of this disease. Furthermore, the histologic results would have been entirely different.

While syphilis (choice “b”), especially in its primary stage, can present with nonhealing sores, in no way do they resemble the patient’s lesions. There is also no source for such an infection. And biopsy would have shown a predominately plasma cell infiltrate in an entirely different pattern.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (choice “d”) is quite uncommon, especially on the penis, where it is usually known as balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO). As its name suggests, BXO is usually atrophic—therefore macular—and whitish. Exclusive to uncircumcised men, it bears no resemblance to condyloma.

Though idiopathic, lichen planus is not contagious. Unless neglected, this condition seldom causes any suffering aside from mental anguish over its appearance. To make a more accurate diagnosis, it is always helpful for providers to consider a mnemonic device for “7 Ps” associated with lichen planus:

- Penile

- Pruritic

- Plaque-like

- Purple

- Papular

- Planar

- Puzzling.

TREATMENT

Fortunately, lichen planus affecting the penis responds readily to treatment with mid-strength topical steroid cream and the "tincture of time," which improves its appearance until it eventually disappears. For this patient, the PCP treated the affected area with triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid for 2 weeks. This was then applied once a day every other day for a month, which cleared the patient’s lesions.

ANSWER

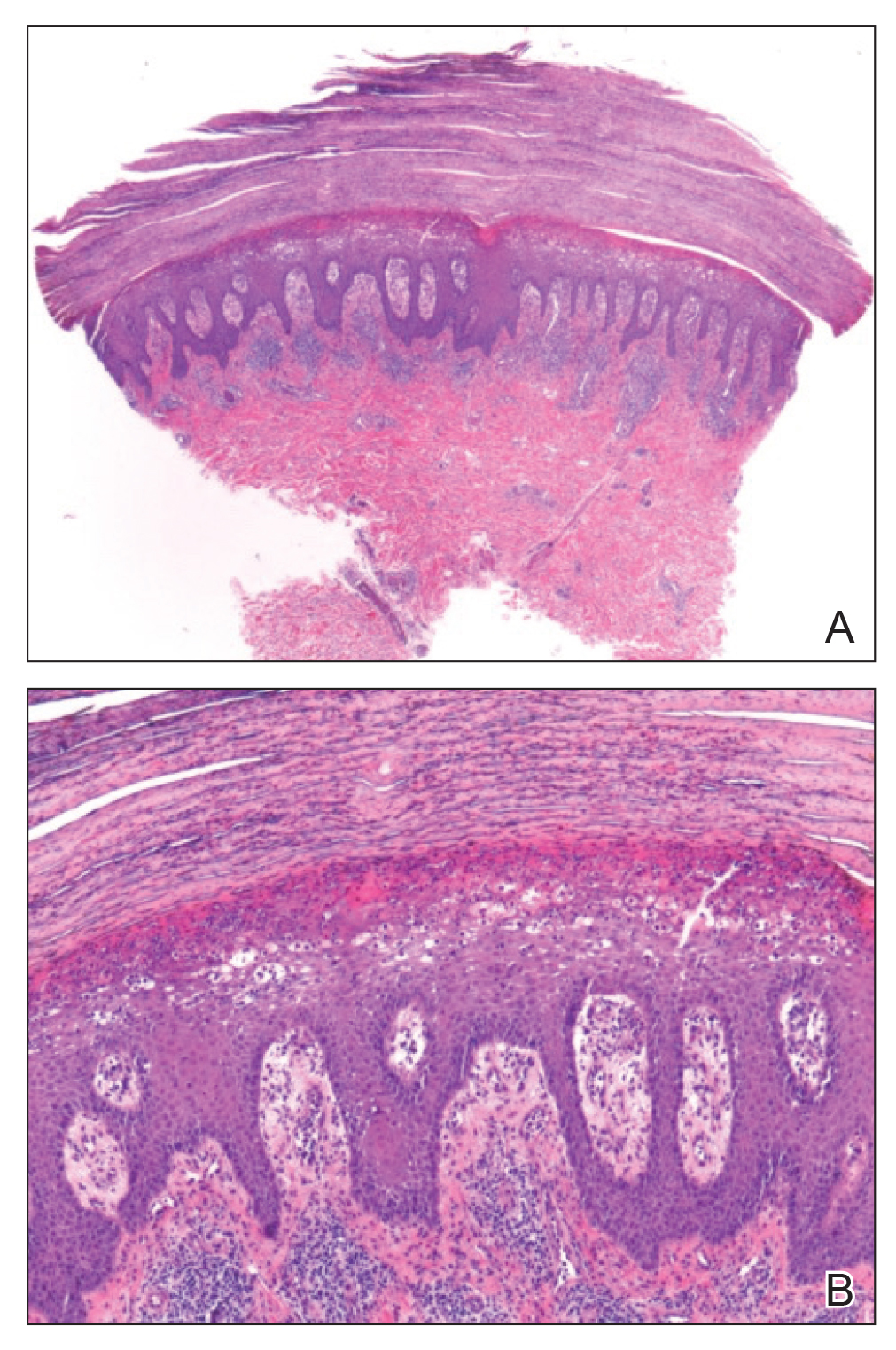

The correct answer is lichen planus (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Condyloma accuminata can demonstrate amazing lability, sometimes appearing decades after exposure. And spouses may not always be truthful when questioned about such exposure. To further confuse the issue, it's entirely possible that a patient may be unaware he or she has condyloma. So, this might well have been condyloma. But the differential for penile lesions would include this condition—and more.

Psoriasis (choice “a”) commonly affects the penis, manifesting as pinkish plaques and papules. But there is a good chance that examination would have revealed corroborative signs of this disease. Furthermore, the histologic results would have been entirely different.

While syphilis (choice “b”), especially in its primary stage, can present with nonhealing sores, in no way do they resemble the patient’s lesions. There is also no source for such an infection. And biopsy would have shown a predominately plasma cell infiltrate in an entirely different pattern.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (choice “d”) is quite uncommon, especially on the penis, where it is usually known as balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO). As its name suggests, BXO is usually atrophic—therefore macular—and whitish. Exclusive to uncircumcised men, it bears no resemblance to condyloma.

Though idiopathic, lichen planus is not contagious. Unless neglected, this condition seldom causes any suffering aside from mental anguish over its appearance. To make a more accurate diagnosis, it is always helpful for providers to consider a mnemonic device for “7 Ps” associated with lichen planus:

- Penile

- Pruritic

- Plaque-like

- Purple

- Papular

- Planar

- Puzzling.

TREATMENT

Fortunately, lichen planus affecting the penis responds readily to treatment with mid-strength topical steroid cream and the "tincture of time," which improves its appearance until it eventually disappears. For this patient, the PCP treated the affected area with triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid for 2 weeks. This was then applied once a day every other day for a month, which cleared the patient’s lesions.

A 41-year-old man is understandably upset when his primary care provider (PCP) diagnoses him with penile warts. Still, he is more than willing to allow his PCP to treat the area with liquid nitrogen, which clears the affected area. However, after about a month, the warts reappear in the same area, with the same appearance, and the patient decides to consult his PCP about additional treatment.

To his distress, his PCP suggests that the warts may continue to return despite treatment. This prompts the patient to ask a more upsetting question: How had he even acquired the warts? Neither he nor his wife of 20 years has had any other sexual contact. Prior to marriage, he had no sexual encounters by which he might have acquired human papillomavirus (HPV).

The patient is otherwise quite healthy, though anxious to have his warts treated again despite the possibility of recurrence. At no point have the warts been symptomatic. His wife's Pap smears have been completely normal.

Examination reveals 4 tiny, pink, planar (flat-topped), 2-to-4-mm papules in 2 locations on the penile shaft. Each has a soft shiny surface. There is also a soft, smooth, pink, annular, 2-cm plaque on the distal shaft that spills over onto the corona focally.

Shave biopsy of 1 lesion shows a brisk lymphocytic infiltrate, which obliterated the dermo-epidermal junction, imparting a jagged sawtooth pattern to its usually smooth wave-like pattern. There are no signs of HPV. The patient has no other remarkable lesions or changes on his elbows, knees, trunk, legs, nails, or scalp.

Radial artery beats saphenous vein grafting 10 years after CABG

With a median follow-up of 10 years after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), patients who received a radial artery graft rather than a saphenous vein graft as a second conduit were less likely to experience death, MI, or repeat revascularization, according to pooled data from five randomized trials.

The same result from the same set of data was produced after a median of 5 years, but the longer follow-up provides a more compelling case for the superiority of the radial artery graft, according to the authors of this meta-analysis, led by Mario F.L. Gaudino, MD, professor of cardiothoracic surgery at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

For the primary composite endpoint of death, MI, or repeat revascularization, the favorable hazard ratio at 5 years corresponded to a 33% risk reduction (HR, 0.67; P = .01), according to the previously published results (Gaudino M et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2069-77).

The new data at 10 years show about the same risk reduction for the primary endpoint, but with more robust statistical significance (HR, 0.73; P < .001).

More importantly, because of the greater number of events by 10 years, the advantage of radial artery graft for the secondary composite outcome of death or MI has now reached statistical significance (HR, 0.77; P = .01).

In addition, there was a 27% reduction in risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-0.93) at 10 years associated with the radial artery graft. But this was not a prespecified endpoint, and so this is a hypothesis-generating post hoc finding.

The data was drawn from five randomized trials with a total of 1,036 patients. When used as an additional conduit to an internal thoracic artery in CABG, radial artery grafts relative to saphenous vein grafts were associated with a lower but nonsignificant risk of adverse outcomes in all five trials.

The advantage of radial artery grafts in the meta-analysis at 5 and now 10 years supports a series of observational studies that have also claimed better results with radial artery grafts.

The analysis was published July 14 in JAMA with essentially the same outcomes reported at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation in March.

However, a editorial that accompanied this meta-analysis in JAMA raised fundamental questions about revascularization.

“Intuitively, high-severity coronary lesions with significant ischemic burden, poor collateralization, and significant myocardium at risk may benefit from a durable revascularization option,” observed the editorial coauthors, Steven E. Nissen, MD, and Faisal G. Bakaeen, MD, both of the Cleveland Clinic. However, they cautioned that there is no definitive evidence that “any revascularization procedure reduces cardiovascular morbidity or mortality in patients with anatomically and physiologically stable coronary artery disease.”

They called the 10-year outcomes from the meta-analysis “the best available long-term data on the potential value of using the radial artery as a bypass conduit,” but warned that no randomized trial has confirmed that two or more conduits are superior to a single internal thoracic artery in CABG to for preventing death and major adverse cardiovascular events.

Such a trial, called ROMA, is now underway (Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;52:1031-40), but results are not expected until 2025.

In the meantime, placement of second conduits remains common in CABG procedures, about 400,000 of which are performed each year in the United States. According to Dr. Gaudino, there are indications and contraindications for second conduits, but radial artery should be the preferred standard when these are considered.

“Our data indicate that the radial artery graft should be used to complement the left internal thoracic artery in all patients who meet the indications for radial artery grafts,” he explained in an interview.

“Unfortunately, at the moment radial artery grafts are used in less than 10% of CABG cases in the U.S.,” he reported. “Hopefully, our data will lead to a larger use of this conduit by the surgical community.”

Dr. Gaudino, the principal investigator, reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Gaudino MFL et al. JAMA. 2020;324:179-87.

With a median follow-up of 10 years after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), patients who received a radial artery graft rather than a saphenous vein graft as a second conduit were less likely to experience death, MI, or repeat revascularization, according to pooled data from five randomized trials.

The same result from the same set of data was produced after a median of 5 years, but the longer follow-up provides a more compelling case for the superiority of the radial artery graft, according to the authors of this meta-analysis, led by Mario F.L. Gaudino, MD, professor of cardiothoracic surgery at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

For the primary composite endpoint of death, MI, or repeat revascularization, the favorable hazard ratio at 5 years corresponded to a 33% risk reduction (HR, 0.67; P = .01), according to the previously published results (Gaudino M et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2069-77).

The new data at 10 years show about the same risk reduction for the primary endpoint, but with more robust statistical significance (HR, 0.73; P < .001).

More importantly, because of the greater number of events by 10 years, the advantage of radial artery graft for the secondary composite outcome of death or MI has now reached statistical significance (HR, 0.77; P = .01).

In addition, there was a 27% reduction in risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-0.93) at 10 years associated with the radial artery graft. But this was not a prespecified endpoint, and so this is a hypothesis-generating post hoc finding.

The data was drawn from five randomized trials with a total of 1,036 patients. When used as an additional conduit to an internal thoracic artery in CABG, radial artery grafts relative to saphenous vein grafts were associated with a lower but nonsignificant risk of adverse outcomes in all five trials.

The advantage of radial artery grafts in the meta-analysis at 5 and now 10 years supports a series of observational studies that have also claimed better results with radial artery grafts.

The analysis was published July 14 in JAMA with essentially the same outcomes reported at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation in March.

However, a editorial that accompanied this meta-analysis in JAMA raised fundamental questions about revascularization.

“Intuitively, high-severity coronary lesions with significant ischemic burden, poor collateralization, and significant myocardium at risk may benefit from a durable revascularization option,” observed the editorial coauthors, Steven E. Nissen, MD, and Faisal G. Bakaeen, MD, both of the Cleveland Clinic. However, they cautioned that there is no definitive evidence that “any revascularization procedure reduces cardiovascular morbidity or mortality in patients with anatomically and physiologically stable coronary artery disease.”

They called the 10-year outcomes from the meta-analysis “the best available long-term data on the potential value of using the radial artery as a bypass conduit,” but warned that no randomized trial has confirmed that two or more conduits are superior to a single internal thoracic artery in CABG to for preventing death and major adverse cardiovascular events.

Such a trial, called ROMA, is now underway (Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;52:1031-40), but results are not expected until 2025.

In the meantime, placement of second conduits remains common in CABG procedures, about 400,000 of which are performed each year in the United States. According to Dr. Gaudino, there are indications and contraindications for second conduits, but radial artery should be the preferred standard when these are considered.

“Our data indicate that the radial artery graft should be used to complement the left internal thoracic artery in all patients who meet the indications for radial artery grafts,” he explained in an interview.

“Unfortunately, at the moment radial artery grafts are used in less than 10% of CABG cases in the U.S.,” he reported. “Hopefully, our data will lead to a larger use of this conduit by the surgical community.”

Dr. Gaudino, the principal investigator, reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Gaudino MFL et al. JAMA. 2020;324:179-87.

With a median follow-up of 10 years after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), patients who received a radial artery graft rather than a saphenous vein graft as a second conduit were less likely to experience death, MI, or repeat revascularization, according to pooled data from five randomized trials.

The same result from the same set of data was produced after a median of 5 years, but the longer follow-up provides a more compelling case for the superiority of the radial artery graft, according to the authors of this meta-analysis, led by Mario F.L. Gaudino, MD, professor of cardiothoracic surgery at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

For the primary composite endpoint of death, MI, or repeat revascularization, the favorable hazard ratio at 5 years corresponded to a 33% risk reduction (HR, 0.67; P = .01), according to the previously published results (Gaudino M et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2069-77).

The new data at 10 years show about the same risk reduction for the primary endpoint, but with more robust statistical significance (HR, 0.73; P < .001).

More importantly, because of the greater number of events by 10 years, the advantage of radial artery graft for the secondary composite outcome of death or MI has now reached statistical significance (HR, 0.77; P = .01).

In addition, there was a 27% reduction in risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-0.93) at 10 years associated with the radial artery graft. But this was not a prespecified endpoint, and so this is a hypothesis-generating post hoc finding.

The data was drawn from five randomized trials with a total of 1,036 patients. When used as an additional conduit to an internal thoracic artery in CABG, radial artery grafts relative to saphenous vein grafts were associated with a lower but nonsignificant risk of adverse outcomes in all five trials.

The advantage of radial artery grafts in the meta-analysis at 5 and now 10 years supports a series of observational studies that have also claimed better results with radial artery grafts.

The analysis was published July 14 in JAMA with essentially the same outcomes reported at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation in March.

However, a editorial that accompanied this meta-analysis in JAMA raised fundamental questions about revascularization.

“Intuitively, high-severity coronary lesions with significant ischemic burden, poor collateralization, and significant myocardium at risk may benefit from a durable revascularization option,” observed the editorial coauthors, Steven E. Nissen, MD, and Faisal G. Bakaeen, MD, both of the Cleveland Clinic. However, they cautioned that there is no definitive evidence that “any revascularization procedure reduces cardiovascular morbidity or mortality in patients with anatomically and physiologically stable coronary artery disease.”

They called the 10-year outcomes from the meta-analysis “the best available long-term data on the potential value of using the radial artery as a bypass conduit,” but warned that no randomized trial has confirmed that two or more conduits are superior to a single internal thoracic artery in CABG to for preventing death and major adverse cardiovascular events.

Such a trial, called ROMA, is now underway (Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;52:1031-40), but results are not expected until 2025.

In the meantime, placement of second conduits remains common in CABG procedures, about 400,000 of which are performed each year in the United States. According to Dr. Gaudino, there are indications and contraindications for second conduits, but radial artery should be the preferred standard when these are considered.

“Our data indicate that the radial artery graft should be used to complement the left internal thoracic artery in all patients who meet the indications for radial artery grafts,” he explained in an interview.

“Unfortunately, at the moment radial artery grafts are used in less than 10% of CABG cases in the U.S.,” he reported. “Hopefully, our data will lead to a larger use of this conduit by the surgical community.”

Dr. Gaudino, the principal investigator, reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Gaudino MFL et al. JAMA. 2020;324:179-87.

FROM JAMA

Pooled Testing for SARS-CoV-2 in Hospitalized Patients

Viral testing for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) of all patients admitted to the hospital is an appealing objective given the recognition of asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic infections. Yet such testing requires that all admitted patients be classified as persons under investigation (PUIs) until their test results are known. If an outside laboratory is used for the SARS-CoV-2 testing, the delay in obtaining results for these PUIs may cause significant personal protective equipment (PPE) use, postpone some care for non-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) conditions, block beds, and produce anxiety among staff and other patients. Rapid in-house testing of all admitted patients may resolve these issues but may be limited by the supply of reagents. To address this challenge, we piloted a pooled testing strategy for patients at low risk for SARS-CoV-2 admitted to a community hospital.

METHODS

From April 17, 2020, to May 11, 2020, we implemented a pooled testing strategy using the GeneXpert® System (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California) at Saratoga Hospital, a 171-bed community hospital in upstate New York. Under normal procedures for this system, a single patient swab is placed in a vial containing viral transport media (VTM). An aliquot of this media is then transferred into a Xpert® Xpress SARS CoV-2 test cartridge and assayed on the GeneXpert® instrument in our laboratory. Obtaining immediate results allowed us to assign admitted patients to either a COVID-19 or a non–COVID-19 unit, improving the issues associated with PUIs. Unfortunately, we did not have enough test cartridges to sustain this strategy of rapid individual testing of all admitted patients, and supply lines have remained uncertain.

We sought to conserve our limited Xpert Xpress SARS CoV-2 test cartridges using the strategy of pooled testing, a technique reported in Germany and by the University of Nebraska.1,2 In this method, variable numbers of tests are pooled for a single analysis. If the test from the pooled vial is negative, these patients are all considered negative. If the pooled test is positive, all those patients need individual testing. This pooling method has been theorized to preserve test cartridges when the expected frequency of positive results is low.3

All patients admitted or placed on observation underwent SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing. The Emergency Department (ED) staff stratified patients into high or low risk to determine if they would be tested in a single send-out test (high risk) or a rapid in-house pooled group (low risk). High-risk patients were those with compatible history, physical exam, laboratory markers, and radiographic studies for COVID-19 disease. This often included increased supplemental oxygen requirement, multiple elevated inflammatory markers (including D-dimer, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and ferritin levels), lymphopenia, and findings on chest radiograph or computed tomography scan including ground glass changes, multifocal pneumonia, or pneumonia. High-risk patients were admitted to the COVID unit or intensive care unit, had a send-out SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, and were treated as a PUI until the results of their testing was known and correlated with their clinical course. Low-risk patients were those without complaints suggestive of COVID-19 infection and who may have had negative inflammatory markers, no significant lymphopenia, and negative imaging.

The samples from 3 admitted patients thought to be at low-risk for COVID-19 using the clinical judgement of our ED staff were pooled for testing. All samples were obtained using nasopharyngeal swabs by experienced staff. The swabs from these patients were placed into a single vial of 3 mL VTM, maintaining the recommended 1 swab per mL of VTM. An aliquot of this media was then transferred into an Xpert Xpress SARS CoV-2 test cartridge and assayed on the GeneXpert instrument in our laboratory following manufacturer’s instructions. Based on analytic laboratory studies of the Cepheid Xpert Express SARS-CoV-2 test,4 we assume a clinical performance comparable to other reverse-transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) tests, which have so far demonstrated sensitivities of 60% to 80% and specificities of 95% to 99%.5

Validation studies were performed on pools made from samples obtained from admitted patients with previously known positive and negative samples tested at the New York State Department of Health, Wadsworth Center laboratory (Albany, New York). A total of 14 samples were used for the instrument validation study, including three samples for pooled testing. The cycle threshold (Ct) value is defined as the number of PCR cycles required for the signal to be detectable. Ct values for each nucleic acid target of a known positive sample tested singly and in the pool with known negative patients were compared. A small shift in Ct values was noted between single and pooled testing, demonstrating no decrease in analytic sensitivity and suggesting that we would experience no decrease in clinical sensitivity.

We selected the pooling of 3 samples into 1 cartridge for several reasons: (1) 3-sample pools are well within the appropriate pooling size for the percentage positive rate in the population being tested. The use of larger pool sizes results in the need for more repeat testing when a positive result is obtained; (2) Given our supply lines, the projected savings would allow us to continue this strategy; and (3) Holding 3 patients in the ED until a pool was ready was manageable given our rate of admissions and ED volume.

The strategy required patients being held in the ED until a pooled group of 3 could be tested. On select occasions when holding patients in the ED to obtain a pool of 3 was not practical, 2 patients were tested in the pool. These decisions required close coordination between the laboratory, ED, and nursing staff.

RESULTS

This strategy resulted in 530 unique patient tests in 179 cartridges (172 with three swabs and 7 with two swabs). We had 4 positive pooled tests, requiring the use of 11 additional cartridges, for a positive rate of 0.8% (4/530) in this low-risk population (patients without COVID-19–related symptoms). There were no patients from negative pools who developed evidence of COVID-19 disease or tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during their hospitalization. The total number of cartridges used was 190 and the number saved was 340.

DISCUSSION

The strategy of pooled testing for SARS-CoV-2 in patients admitted to our community hospital allowed us to continue rapid testing of admitted patients at low risk for COVID-19 disease during a period when supplies would otherwise not have been sufficient. We believe this strategy conserved PPE, led to a marked reduction in staff and patient anxiety, and improved patient care. Our impression is that testing all admitted patients has also been reassuring to our community. Like many others, we have observed that public fear of entering the hospital during this pandemic has caused delays in patients seeking care for non–COVID-19 conditions. We believe this strategy will help reduce those fears.

This strategy may require modification as the pandemic progresses. Our ED physicians were able to identify patients who they felt to be low risk for having COVID-19 disease based on signs, symptoms, and clinical impression during a time when we had an 8% positive rate among symptomatic outpatients and an estimated community positive rate in the range of 1% to 2%. If the rate of positive tests in our community rises, the use of pooling may need to be limited or the pool size reduced. If our supply of reagents is further limited or patient testing demand increases, the pool size may need to be increased. This will need to be balanced with our ability to hold patients in the ED while waiting for the pool size to be reached.

CONCLUSION

The strategy of pooled testing for SARS-CoV-2 has allowed us to continue to immediately test all admitted patients, thus improving patient care. It has required close coordination between multiple members of our laboratory and clinical staff and may require adjustment as the pandemic progresses. We believe it is a valuable tool during a time of limited resources that may have application in testing other low-risk groups, including healthcare workers and clients of occupational medicine services.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Kirsten St. George, MAppSc, PhD, Director, Virology Laboratory, Wadsworth, NYSDOH, and the services supplied by the Wadsworth laboratory to our region.

1. Corona ‘pool testing’ increases worldwide capacities many times over. January 4, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2020. https://healthcare-in-europe.com/en/news/corona-pool-testing-increases-worldwide-capacities-many-times-over.html

2. Abdalhamid B, Bilder CR, McCutchen EL, Hinrichs SH, Koepsell SA, Iwen PC. Assessment of specimen pooling to conserve SARS CoV-2 testing resources. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153(6):715-718. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqaa064

3. Shani-Narkiss H, Gilday OD, Yayon N, Landau ID. Efficient and practical sample pooling for high-throughput PCR diagnosis of COVID-19. medRxiv. April 6, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.06.20052159

4. Wolters F, van de Bovenkamp J, van den Bosch B, et al. Multi-center evaluation of Cepheid Xpert® Xpress SARS-CoV-2 point-of-care test during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J Clin Virol. 2020;128:104426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104426

5. Woloshin S, Patel N, Kesselheim AS. False negative tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection—challenges and implications. N Engl J Med. 2020. Online first. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2015897

Viral testing for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) of all patients admitted to the hospital is an appealing objective given the recognition of asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic infections. Yet such testing requires that all admitted patients be classified as persons under investigation (PUIs) until their test results are known. If an outside laboratory is used for the SARS-CoV-2 testing, the delay in obtaining results for these PUIs may cause significant personal protective equipment (PPE) use, postpone some care for non-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) conditions, block beds, and produce anxiety among staff and other patients. Rapid in-house testing of all admitted patients may resolve these issues but may be limited by the supply of reagents. To address this challenge, we piloted a pooled testing strategy for patients at low risk for SARS-CoV-2 admitted to a community hospital.

METHODS

From April 17, 2020, to May 11, 2020, we implemented a pooled testing strategy using the GeneXpert® System (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California) at Saratoga Hospital, a 171-bed community hospital in upstate New York. Under normal procedures for this system, a single patient swab is placed in a vial containing viral transport media (VTM). An aliquot of this media is then transferred into a Xpert® Xpress SARS CoV-2 test cartridge and assayed on the GeneXpert® instrument in our laboratory. Obtaining immediate results allowed us to assign admitted patients to either a COVID-19 or a non–COVID-19 unit, improving the issues associated with PUIs. Unfortunately, we did not have enough test cartridges to sustain this strategy of rapid individual testing of all admitted patients, and supply lines have remained uncertain.

We sought to conserve our limited Xpert Xpress SARS CoV-2 test cartridges using the strategy of pooled testing, a technique reported in Germany and by the University of Nebraska.1,2 In this method, variable numbers of tests are pooled for a single analysis. If the test from the pooled vial is negative, these patients are all considered negative. If the pooled test is positive, all those patients need individual testing. This pooling method has been theorized to preserve test cartridges when the expected frequency of positive results is low.3

All patients admitted or placed on observation underwent SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing. The Emergency Department (ED) staff stratified patients into high or low risk to determine if they would be tested in a single send-out test (high risk) or a rapid in-house pooled group (low risk). High-risk patients were those with compatible history, physical exam, laboratory markers, and radiographic studies for COVID-19 disease. This often included increased supplemental oxygen requirement, multiple elevated inflammatory markers (including D-dimer, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and ferritin levels), lymphopenia, and findings on chest radiograph or computed tomography scan including ground glass changes, multifocal pneumonia, or pneumonia. High-risk patients were admitted to the COVID unit or intensive care unit, had a send-out SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, and were treated as a PUI until the results of their testing was known and correlated with their clinical course. Low-risk patients were those without complaints suggestive of COVID-19 infection and who may have had negative inflammatory markers, no significant lymphopenia, and negative imaging.

The samples from 3 admitted patients thought to be at low-risk for COVID-19 using the clinical judgement of our ED staff were pooled for testing. All samples were obtained using nasopharyngeal swabs by experienced staff. The swabs from these patients were placed into a single vial of 3 mL VTM, maintaining the recommended 1 swab per mL of VTM. An aliquot of this media was then transferred into an Xpert Xpress SARS CoV-2 test cartridge and assayed on the GeneXpert instrument in our laboratory following manufacturer’s instructions. Based on analytic laboratory studies of the Cepheid Xpert Express SARS-CoV-2 test,4 we assume a clinical performance comparable to other reverse-transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) tests, which have so far demonstrated sensitivities of 60% to 80% and specificities of 95% to 99%.5

Validation studies were performed on pools made from samples obtained from admitted patients with previously known positive and negative samples tested at the New York State Department of Health, Wadsworth Center laboratory (Albany, New York). A total of 14 samples were used for the instrument validation study, including three samples for pooled testing. The cycle threshold (Ct) value is defined as the number of PCR cycles required for the signal to be detectable. Ct values for each nucleic acid target of a known positive sample tested singly and in the pool with known negative patients were compared. A small shift in Ct values was noted between single and pooled testing, demonstrating no decrease in analytic sensitivity and suggesting that we would experience no decrease in clinical sensitivity.

We selected the pooling of 3 samples into 1 cartridge for several reasons: (1) 3-sample pools are well within the appropriate pooling size for the percentage positive rate in the population being tested. The use of larger pool sizes results in the need for more repeat testing when a positive result is obtained; (2) Given our supply lines, the projected savings would allow us to continue this strategy; and (3) Holding 3 patients in the ED until a pool was ready was manageable given our rate of admissions and ED volume.

The strategy required patients being held in the ED until a pooled group of 3 could be tested. On select occasions when holding patients in the ED to obtain a pool of 3 was not practical, 2 patients were tested in the pool. These decisions required close coordination between the laboratory, ED, and nursing staff.

RESULTS

This strategy resulted in 530 unique patient tests in 179 cartridges (172 with three swabs and 7 with two swabs). We had 4 positive pooled tests, requiring the use of 11 additional cartridges, for a positive rate of 0.8% (4/530) in this low-risk population (patients without COVID-19–related symptoms). There were no patients from negative pools who developed evidence of COVID-19 disease or tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during their hospitalization. The total number of cartridges used was 190 and the number saved was 340.

DISCUSSION

The strategy of pooled testing for SARS-CoV-2 in patients admitted to our community hospital allowed us to continue rapid testing of admitted patients at low risk for COVID-19 disease during a period when supplies would otherwise not have been sufficient. We believe this strategy conserved PPE, led to a marked reduction in staff and patient anxiety, and improved patient care. Our impression is that testing all admitted patients has also been reassuring to our community. Like many others, we have observed that public fear of entering the hospital during this pandemic has caused delays in patients seeking care for non–COVID-19 conditions. We believe this strategy will help reduce those fears.

This strategy may require modification as the pandemic progresses. Our ED physicians were able to identify patients who they felt to be low risk for having COVID-19 disease based on signs, symptoms, and clinical impression during a time when we had an 8% positive rate among symptomatic outpatients and an estimated community positive rate in the range of 1% to 2%. If the rate of positive tests in our community rises, the use of pooling may need to be limited or the pool size reduced. If our supply of reagents is further limited or patient testing demand increases, the pool size may need to be increased. This will need to be balanced with our ability to hold patients in the ED while waiting for the pool size to be reached.

CONCLUSION

The strategy of pooled testing for SARS-CoV-2 has allowed us to continue to immediately test all admitted patients, thus improving patient care. It has required close coordination between multiple members of our laboratory and clinical staff and may require adjustment as the pandemic progresses. We believe it is a valuable tool during a time of limited resources that may have application in testing other low-risk groups, including healthcare workers and clients of occupational medicine services.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Kirsten St. George, MAppSc, PhD, Director, Virology Laboratory, Wadsworth, NYSDOH, and the services supplied by the Wadsworth laboratory to our region.

Viral testing for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) of all patients admitted to the hospital is an appealing objective given the recognition of asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic infections. Yet such testing requires that all admitted patients be classified as persons under investigation (PUIs) until their test results are known. If an outside laboratory is used for the SARS-CoV-2 testing, the delay in obtaining results for these PUIs may cause significant personal protective equipment (PPE) use, postpone some care for non-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) conditions, block beds, and produce anxiety among staff and other patients. Rapid in-house testing of all admitted patients may resolve these issues but may be limited by the supply of reagents. To address this challenge, we piloted a pooled testing strategy for patients at low risk for SARS-CoV-2 admitted to a community hospital.

METHODS

From April 17, 2020, to May 11, 2020, we implemented a pooled testing strategy using the GeneXpert® System (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California) at Saratoga Hospital, a 171-bed community hospital in upstate New York. Under normal procedures for this system, a single patient swab is placed in a vial containing viral transport media (VTM). An aliquot of this media is then transferred into a Xpert® Xpress SARS CoV-2 test cartridge and assayed on the GeneXpert® instrument in our laboratory. Obtaining immediate results allowed us to assign admitted patients to either a COVID-19 or a non–COVID-19 unit, improving the issues associated with PUIs. Unfortunately, we did not have enough test cartridges to sustain this strategy of rapid individual testing of all admitted patients, and supply lines have remained uncertain.

We sought to conserve our limited Xpert Xpress SARS CoV-2 test cartridges using the strategy of pooled testing, a technique reported in Germany and by the University of Nebraska.1,2 In this method, variable numbers of tests are pooled for a single analysis. If the test from the pooled vial is negative, these patients are all considered negative. If the pooled test is positive, all those patients need individual testing. This pooling method has been theorized to preserve test cartridges when the expected frequency of positive results is low.3

All patients admitted or placed on observation underwent SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing. The Emergency Department (ED) staff stratified patients into high or low risk to determine if they would be tested in a single send-out test (high risk) or a rapid in-house pooled group (low risk). High-risk patients were those with compatible history, physical exam, laboratory markers, and radiographic studies for COVID-19 disease. This often included increased supplemental oxygen requirement, multiple elevated inflammatory markers (including D-dimer, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and ferritin levels), lymphopenia, and findings on chest radiograph or computed tomography scan including ground glass changes, multifocal pneumonia, or pneumonia. High-risk patients were admitted to the COVID unit or intensive care unit, had a send-out SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, and were treated as a PUI until the results of their testing was known and correlated with their clinical course. Low-risk patients were those without complaints suggestive of COVID-19 infection and who may have had negative inflammatory markers, no significant lymphopenia, and negative imaging.

The samples from 3 admitted patients thought to be at low-risk for COVID-19 using the clinical judgement of our ED staff were pooled for testing. All samples were obtained using nasopharyngeal swabs by experienced staff. The swabs from these patients were placed into a single vial of 3 mL VTM, maintaining the recommended 1 swab per mL of VTM. An aliquot of this media was then transferred into an Xpert Xpress SARS CoV-2 test cartridge and assayed on the GeneXpert instrument in our laboratory following manufacturer’s instructions. Based on analytic laboratory studies of the Cepheid Xpert Express SARS-CoV-2 test,4 we assume a clinical performance comparable to other reverse-transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) tests, which have so far demonstrated sensitivities of 60% to 80% and specificities of 95% to 99%.5

Validation studies were performed on pools made from samples obtained from admitted patients with previously known positive and negative samples tested at the New York State Department of Health, Wadsworth Center laboratory (Albany, New York). A total of 14 samples were used for the instrument validation study, including three samples for pooled testing. The cycle threshold (Ct) value is defined as the number of PCR cycles required for the signal to be detectable. Ct values for each nucleic acid target of a known positive sample tested singly and in the pool with known negative patients were compared. A small shift in Ct values was noted between single and pooled testing, demonstrating no decrease in analytic sensitivity and suggesting that we would experience no decrease in clinical sensitivity.

We selected the pooling of 3 samples into 1 cartridge for several reasons: (1) 3-sample pools are well within the appropriate pooling size for the percentage positive rate in the population being tested. The use of larger pool sizes results in the need for more repeat testing when a positive result is obtained; (2) Given our supply lines, the projected savings would allow us to continue this strategy; and (3) Holding 3 patients in the ED until a pool was ready was manageable given our rate of admissions and ED volume.

The strategy required patients being held in the ED until a pooled group of 3 could be tested. On select occasions when holding patients in the ED to obtain a pool of 3 was not practical, 2 patients were tested in the pool. These decisions required close coordination between the laboratory, ED, and nursing staff.

RESULTS

This strategy resulted in 530 unique patient tests in 179 cartridges (172 with three swabs and 7 with two swabs). We had 4 positive pooled tests, requiring the use of 11 additional cartridges, for a positive rate of 0.8% (4/530) in this low-risk population (patients without COVID-19–related symptoms). There were no patients from negative pools who developed evidence of COVID-19 disease or tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during their hospitalization. The total number of cartridges used was 190 and the number saved was 340.

DISCUSSION

The strategy of pooled testing for SARS-CoV-2 in patients admitted to our community hospital allowed us to continue rapid testing of admitted patients at low risk for COVID-19 disease during a period when supplies would otherwise not have been sufficient. We believe this strategy conserved PPE, led to a marked reduction in staff and patient anxiety, and improved patient care. Our impression is that testing all admitted patients has also been reassuring to our community. Like many others, we have observed that public fear of entering the hospital during this pandemic has caused delays in patients seeking care for non–COVID-19 conditions. We believe this strategy will help reduce those fears.

This strategy may require modification as the pandemic progresses. Our ED physicians were able to identify patients who they felt to be low risk for having COVID-19 disease based on signs, symptoms, and clinical impression during a time when we had an 8% positive rate among symptomatic outpatients and an estimated community positive rate in the range of 1% to 2%. If the rate of positive tests in our community rises, the use of pooling may need to be limited or the pool size reduced. If our supply of reagents is further limited or patient testing demand increases, the pool size may need to be increased. This will need to be balanced with our ability to hold patients in the ED while waiting for the pool size to be reached.

CONCLUSION

The strategy of pooled testing for SARS-CoV-2 has allowed us to continue to immediately test all admitted patients, thus improving patient care. It has required close coordination between multiple members of our laboratory and clinical staff and may require adjustment as the pandemic progresses. We believe it is a valuable tool during a time of limited resources that may have application in testing other low-risk groups, including healthcare workers and clients of occupational medicine services.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Kirsten St. George, MAppSc, PhD, Director, Virology Laboratory, Wadsworth, NYSDOH, and the services supplied by the Wadsworth laboratory to our region.

1. Corona ‘pool testing’ increases worldwide capacities many times over. January 4, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2020. https://healthcare-in-europe.com/en/news/corona-pool-testing-increases-worldwide-capacities-many-times-over.html

2. Abdalhamid B, Bilder CR, McCutchen EL, Hinrichs SH, Koepsell SA, Iwen PC. Assessment of specimen pooling to conserve SARS CoV-2 testing resources. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153(6):715-718. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqaa064

3. Shani-Narkiss H, Gilday OD, Yayon N, Landau ID. Efficient and practical sample pooling for high-throughput PCR diagnosis of COVID-19. medRxiv. April 6, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.06.20052159

4. Wolters F, van de Bovenkamp J, van den Bosch B, et al. Multi-center evaluation of Cepheid Xpert® Xpress SARS-CoV-2 point-of-care test during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J Clin Virol. 2020;128:104426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104426

5. Woloshin S, Patel N, Kesselheim AS. False negative tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection—challenges and implications. N Engl J Med. 2020. Online first. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2015897

1. Corona ‘pool testing’ increases worldwide capacities many times over. January 4, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2020. https://healthcare-in-europe.com/en/news/corona-pool-testing-increases-worldwide-capacities-many-times-over.html

2. Abdalhamid B, Bilder CR, McCutchen EL, Hinrichs SH, Koepsell SA, Iwen PC. Assessment of specimen pooling to conserve SARS CoV-2 testing resources. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153(6):715-718. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqaa064

3. Shani-Narkiss H, Gilday OD, Yayon N, Landau ID. Efficient and practical sample pooling for high-throughput PCR diagnosis of COVID-19. medRxiv. April 6, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.06.20052159

4. Wolters F, van de Bovenkamp J, van den Bosch B, et al. Multi-center evaluation of Cepheid Xpert® Xpress SARS-CoV-2 point-of-care test during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J Clin Virol. 2020;128:104426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104426

5. Woloshin S, Patel N, Kesselheim AS. False negative tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection—challenges and implications. N Engl J Med. 2020. Online first. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2015897

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Collateral Damage: How COVID-19 Is Adversely Impacting Women Physicians

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has affected every facet of our work and personal lives. While many hope we will return to “normal” with the pandemic’s passing, there is reason to believe medicine, and society, will experience irrevocable changes. Although the number of women pursuing and practicing medicine has increased, inequities remain in compensation, academic rank, and leadership positions.1,2 Within the workplace, women are more likely to be in frontline clinical positions, are more likely to be integral in promoting positive interpersonal relationships and collaborative work environments, and often are less represented in the high-level, decision-making roles in leadership or administration.3,4 These well-described issues may be exacerbated during this pandemic crisis. We describe how the current COVID-19 pandemic may intensify workplace inequities for women, and propose solutions for hospitalist groups, leaders, and administrators to ensure female hospitalists continue to prosper and thrive in these tenuous times.

HOW THE PANDEMIC MAY EXACERBATE EXISTING INEQUITIES

Increasing Demands at Home

Female physicians are more likely to have partners who are employed full-time and report spending more time on household activities including cleaning, cooking, and the care of children, compared with their male counterparts.5 With school and daycare closings, as well as stay-at-home orders in many US states, there has been an increase in household responsibilities and care needs for children remaining at home with a marked decrease in options for stable or emergency childcare.6 As compared with primary care and subspecialty colleagues who can provide a large percentage of their care through telemedicine, this is not the case for hospitalists who must be physically present to care for their patients. Therefore, hospitalists are unable to clinically “work from home” in the same way as many of their colleagues in other specialties. Increased childcare and schooling obligations, coupled with disproportionate household responsibilities and an inability to work from home, will likely result in female hospitalists struggling to meet family needs while pandemic-related work responsibilities are ramping up.7 In addition, women who are involved with administrative, leadership, or research activities may struggle to execute their responsibilities as a result of increased domestic duties.

Many hospitalists are also concerned about contracting COVID-19 and exposing their families to the illness given the high infection rate among healthcare workers and the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE).8,9 Institutions and national organizations, including the Society of Hospital Medicine, have partnered with industry to provide discounted or complimentary hotel rooms for members to aid self-isolation while providing clinical care.10 One famous photo in popular and social media showed a pulmonary and critical care physician in a tent in his garage in order to self-isolate from his family.11 However, since women are often the primary caregivers for their children or other family members and may also be responsible for other important household activities, they may be unable or unwilling to remove themselves from their children and families. As a result, female hospitalists may encounter feelings of guilt or inadequacy if they’re unable to isolate in the same manner as male colleagues.8

Exaggerating Leadership Gap

One of the keys to a robust response to this pandemic is strong, thoughtful, and strategic leadership.12 Institutional, regional, and national leaders are at the forefront of designing the solutions to the many problems the COVID-19 pandemic has created. The paucity of women at high-level leadership positions in institutions across the United States, including university-based, community, public, and private institutions, means that there is a lack of female representation when institutional policy is being discussed and decided.4 This lack of representation may lead to policies and procedures that negatively affect female hospitalists or, at best, fail to consider the needs of or support female physicians. For example, leaders of a hospital medicine group may create mandatory “backup” coverage for night and weekend shifts for their group during surge periods of the pandemic without considering implications for childcare. Finding weekday, daytime coverage is challenging for many during this time when daycares and school are closed, and finding coverage during weekend or overnight hours will be even more challenging. With increased risks for older adults with high-risk medical conditions, grandparents or other friends or family members that previously would have assisted with childcare may no longer be an option. If a female hospitalist is not a member of the leadership group that helped design this coverage structure, there could be a lack of recognition of the undue strain this coverage model could create for women in the group. Even if not intentional, such policies may hinder women’s career stability and opportunities for further advancement, as well as their ability to adequately provide care for their families. Having women as a part of the leadership group that creates policies and schedules and makes pivotal decisions is imperative, especially regarding topics of providing access and compensation for “emergency childcare,” hazard pay, shift length, work conditions, job security, sick leave, workers compensation, advancement opportunities, and hiring practices.

Compensation

The gender pay gap in medicine has been consistently demonstrated among many specialties.13,14 The reasons for this inequity are multifactorial, and the COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to further widen this gap. With the unequal burden of unpaid care provided by women and their higher prevalence as frontline workers, they are at greater risk of needing to take unpaid leave to care for a sick family member or themselves.6,7 Similarly, without hazard pay, those with direct clinical responsibilities bear the risk of illness for themselves and their families without adequate compensation.

Impact on Physical and Mental Health

The overall well-being of the hospitalist workforce is critical to continue to provide the highest level of care for our patients. With higher workloads at home and at work, female hospitalists are at risk for increased burnout. Burnout has been linked to many negative outcomes including poor performance, depression, suicide, and leaving the profession.15 Burnout is documented to be higher in female physicians with several contributing factors that are aggravated by gender inequities, including having children at home, gender bias, and real or perceived lack of fairness in promotion and compensation.16 The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the stress of having children in the home, as well as concerns around fair compensation as described above. The consequences of this have yet to be fully realized but may be dire.

PROPOSED RECOMMENDATIONS

We propose the following recommendations to help mitigate the effects of this epidemic and to continue to move our field forward on our path to equity.

1. Closely monitor the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 on female hospitalists. While there has been a recent increase in scholarship on the pre–COVID-19 state of gender disparities, there is still much that is unknown. As we experience this upheaval in the way our institutions function, it is even more imperative to track gender deaggregated key indicators of wellness, burnout, and productivity. This includes the use of burnout inventories, salary equity reviews, procedures that track progress toward promotion, and even focus groups of female hospitalists.

2. Inquire about the needs of women in your organization and secure the support they need. This may take the form of including women on key task forces that address personal protective equipment allocation, design new processes, and prepare for surge capacity, as well as providing wellness initiatives, fostering collaborative social networks, or connecting them with emergency childcare resources.

3. Provide a mechanism to account for lack of academic productivity during this time. This period of decreased academic productivity may disproportionately derail progress toward promotion for women. Academic institutions should consider extending deadlines for promotion or tenure, as well as increasing flexibility in metrics used to determine appropriate progress in annual performance reviews.

4. Recognize and reward increased efforts in the areas of clinical or administrative contribution. In this time of crisis, women may be stepping up and leading efforts without titles or positions in ways that are significant and meaningful for their group or organization. Recognizing the ways women are contributing in a tangible and explicit way can provide an avenue for fair compensation, recognition, and career advancement. Female hospitalists should also “manage up” by speaking up and ensuring that leaders are aware of contributions. Amplification is another powerful technique whereby unrecognized contributions can be called out by other women or men.17

5. Support diversity, inclusion, and equity efforts. Keeping equity targets at the top of priority lists for goals moving forward will be imperative. Many institutions struggled to support strong diversity, inclusion, and equity efforts prior to COVID-19; however, the pandemic has highlighted the stark racial and socioeconomic disparities that exist in healthcare.18,19 As healthcare institutions and providers work to mitigate these disparities for patients, there would be no better time to look internally at how they pay, support, and promote their own employees. This would include actively identifying and mitigating any disparities that exist for employees by gender, race, religion, sexual orientation, ethnicity, age, or disability status.

6. Advocate for fair compensation for providers caring for COVID-19 patients. Frontline clinicians are bearing significant risks and increased workload during this crisis and should be compensated accordingly. Hazard pay, paid sick leave, medical and supplemental life insurance, and strong workers’ compensation protections for hospitalists who become ill at work are important for all clinicians, including women. Other long-term plans should include institutional interventions such as salary corrections and ongoing monitoring.20

SUMMARY

The COVID-19 pandemic will have long-term effects that are yet to be realized, including potentially widening gender disparities in medicine. With the current health and economic crises facing our institutions and nations, it can be tempting for diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives to fall by the wayside. However, it is imperative that hospitalists, leaders, and institutions monitor the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on women and proactively work to mitigate worsening disparities. Without this focus there is a risk that the recent gains in equity and advancement for women may be lost.

1. Association of American Medical Colleges. Table 13: US medical school faculty by sex, rank, and department, 2017-2018. December 31, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/download/486102/data/17table13.pdf

2. Spector ND, Asante PA, Marcelin JR, et al. Women in pediatrics: progress, barriers, and opportunities for equity, diversity, and inclusion. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20192149. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2149

3. Rouse LP, Nagy-Agren S, Gebhard RE, Bernstein WK. Women physicians: gender and the medical workplace. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29(3):297‐309. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.7290

4. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340