User login

Oral propranolol shown safe in PHACE

LAHAINA, HAWAII – Reassuring evidence of the safety of oral propranolol for treatment of complicated infantile hemangiomas in patients with PHACE syndrome comes from a recent multicenter study.

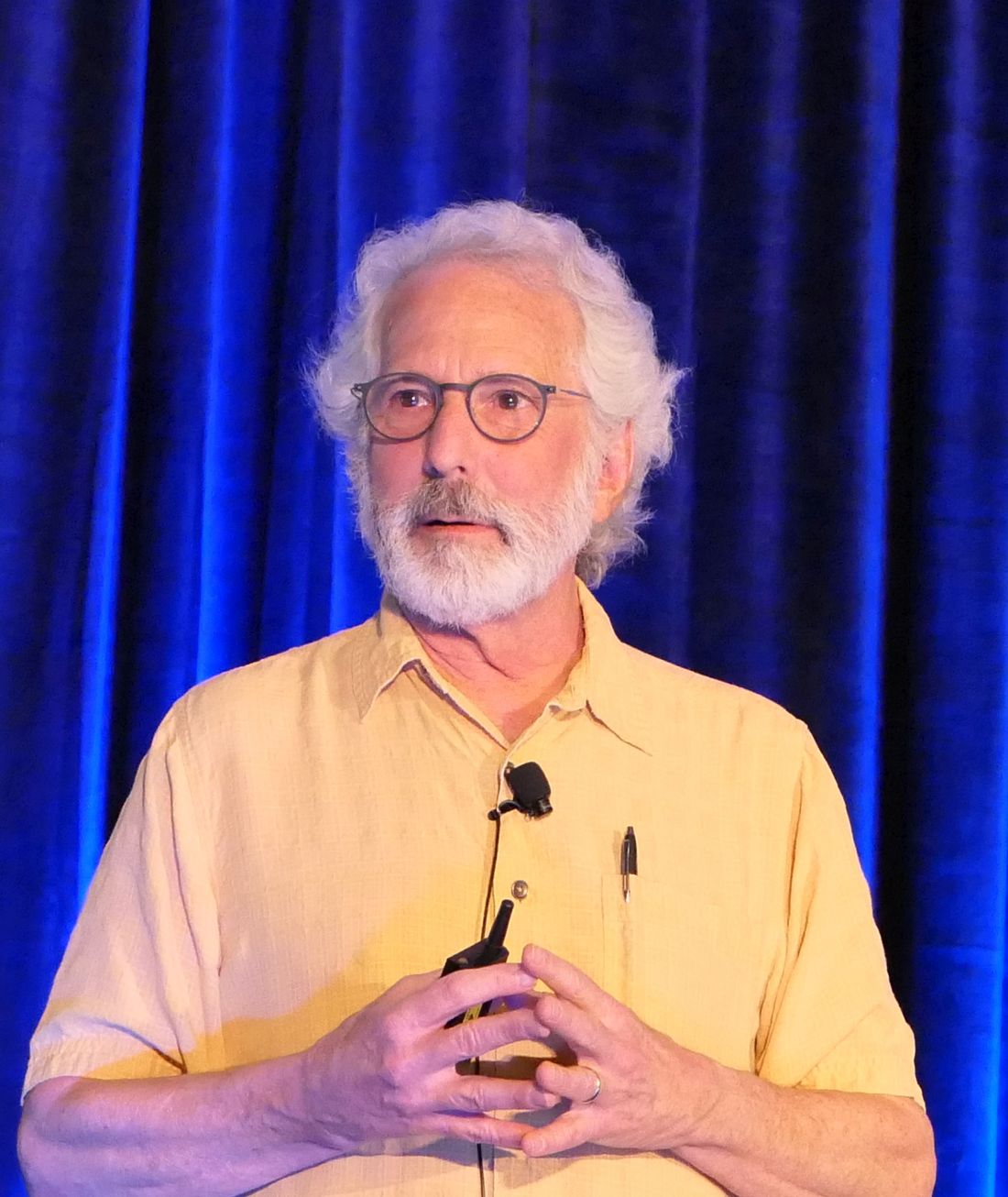

Oral propranolol is now well-ensconced as first-line therapy for complicated infantile hemangiomas in otherwise healthy children. However, the beta-blocker’s use in PHACE (Posterior fossa malformations, Hemangiomas, Arterial anomalies, Cardiac defects, and Eye abnormalities) syndrome has been controversial, with concerns raised by some that it might raise the risk for arterial ischemic stroke. Not so, Moise L. Levy, MD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“I’m not suggesting you use propranolol with reckless abandon in this population, but this stroke concern is something that should be put to bed based on this study,” advised Dr. Levy, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Dell Medical School in Austin, Tex., and physician-in-chief at Dell Children’s Medical Center.

PHACE syndrome is characterized by large, thick, plaque-like hemangiomas greater than 5 cm in size, most commonly on the face, although they can be located elsewhere.

“There was concern that if you found severely altered cerebrovascular arterial flow and you put a kid on a beta-blocker you might be causing some harm. But what I will tell you is that in this recently published paper this was not in fact an issue,” he said.

Dr. Levy was not an investigator in the multicenter retrospective study, which included 76 patients with PHACE syndrome treated for infantile hemangioma with oral propranolol at 0.3 mg/kg per dose or more at 11 academic tertiary care pediatric dermatology clinics. Treatment started at a median age of 56 days.

There were no strokes, TIAs, cardiovascular events, or other significant problems associated with treatment. Twenty-nine children experienced mild adverse events: minor gastrointestinal or respiratory symptoms, and sleep disturbances were threefold more frequent than reported with placebo in another study. The investigators noted that the safety experience in their PHACE syndrome population compared favorably with that in 726 infants without PHACE syndrome who received oral propranolol for hemangiomas, where the incidence of serious adverse events on treatment was 0.4% (JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Dec 11. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3839).

‘Hemangiomas – but we were taught that they go away’

Dr. Levy gave a shout-out to the American Academy of Pediatrics for publishing interdisciplinary expert consensus-based practice guidelines for the management of infantile hemangiomas, which he praised as “quite well done” (Pediatrics. 2019 Jan;143[1]. pii: e20183475. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3475).

Following release of the guidelines last year, he and other pediatric vascular anomalies experts saw an uptick in referrals from general pediatricians, which has since tapered off.

“It’s probably like for all of us: We read an article, it’s fresh on the mind, then you forget about the article and what you’ve read. So we need a little reinforcement from a learning perspective. This is a great article,” he said.

The guidelines debunk as myth the classic teaching that infantile hemangiomas go away. Explicit information is provided about the high-risk anatomic sites warranting consideration for early referral, including the periocular, lumbosacral, and perineal areas, the lip, and lower face.

“The major point is early identification of those lesions requiring evaluation and intervention. Hemangiomas generally speaking are at their ultimate size by 3-5 months of age. The bottom line is if you think something needs to be done, please send that patient, or act upon that patient, sooner rather than later. I can’t tell you how many cases of hemangiomas I’ve seen when the kid is 18 months of age, 3 years of age, 5 years, with a large area of redundant skin, scarring, or something of that sort, and it would have been really nice to have seen them earlier and acted upon them then,” the pediatric dermatologist said.

The guidelines recommend intervention or referral by 1 month of age, ideally. Guidance is provided about the use of oral propranolol as first-line therapy.

“Propranolol is something that has been a real game changer for us,” he noted. “Many people continue to be worried about side effects in using this, particularly in the young childhood population, but this paper shows pretty clearly that hypotension or bradycardia is not a real concern. I never hospitalize these patients for propranolol therapy except in high-risk populations: very preemie, any history of breathing problems. We check the blood pressure and heart rate at baseline, again at 7-10 days, and at every visit. We’ve never found any significant drop in blood pressure.”

Dr. Levy reported financial relationships with half a dozen pharmaceutical companies, none relevant to his presentation.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – Reassuring evidence of the safety of oral propranolol for treatment of complicated infantile hemangiomas in patients with PHACE syndrome comes from a recent multicenter study.

Oral propranolol is now well-ensconced as first-line therapy for complicated infantile hemangiomas in otherwise healthy children. However, the beta-blocker’s use in PHACE (Posterior fossa malformations, Hemangiomas, Arterial anomalies, Cardiac defects, and Eye abnormalities) syndrome has been controversial, with concerns raised by some that it might raise the risk for arterial ischemic stroke. Not so, Moise L. Levy, MD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“I’m not suggesting you use propranolol with reckless abandon in this population, but this stroke concern is something that should be put to bed based on this study,” advised Dr. Levy, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Dell Medical School in Austin, Tex., and physician-in-chief at Dell Children’s Medical Center.

PHACE syndrome is characterized by large, thick, plaque-like hemangiomas greater than 5 cm in size, most commonly on the face, although they can be located elsewhere.

“There was concern that if you found severely altered cerebrovascular arterial flow and you put a kid on a beta-blocker you might be causing some harm. But what I will tell you is that in this recently published paper this was not in fact an issue,” he said.

Dr. Levy was not an investigator in the multicenter retrospective study, which included 76 patients with PHACE syndrome treated for infantile hemangioma with oral propranolol at 0.3 mg/kg per dose or more at 11 academic tertiary care pediatric dermatology clinics. Treatment started at a median age of 56 days.

There were no strokes, TIAs, cardiovascular events, or other significant problems associated with treatment. Twenty-nine children experienced mild adverse events: minor gastrointestinal or respiratory symptoms, and sleep disturbances were threefold more frequent than reported with placebo in another study. The investigators noted that the safety experience in their PHACE syndrome population compared favorably with that in 726 infants without PHACE syndrome who received oral propranolol for hemangiomas, where the incidence of serious adverse events on treatment was 0.4% (JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Dec 11. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3839).

‘Hemangiomas – but we were taught that they go away’

Dr. Levy gave a shout-out to the American Academy of Pediatrics for publishing interdisciplinary expert consensus-based practice guidelines for the management of infantile hemangiomas, which he praised as “quite well done” (Pediatrics. 2019 Jan;143[1]. pii: e20183475. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3475).

Following release of the guidelines last year, he and other pediatric vascular anomalies experts saw an uptick in referrals from general pediatricians, which has since tapered off.

“It’s probably like for all of us: We read an article, it’s fresh on the mind, then you forget about the article and what you’ve read. So we need a little reinforcement from a learning perspective. This is a great article,” he said.

The guidelines debunk as myth the classic teaching that infantile hemangiomas go away. Explicit information is provided about the high-risk anatomic sites warranting consideration for early referral, including the periocular, lumbosacral, and perineal areas, the lip, and lower face.

“The major point is early identification of those lesions requiring evaluation and intervention. Hemangiomas generally speaking are at their ultimate size by 3-5 months of age. The bottom line is if you think something needs to be done, please send that patient, or act upon that patient, sooner rather than later. I can’t tell you how many cases of hemangiomas I’ve seen when the kid is 18 months of age, 3 years of age, 5 years, with a large area of redundant skin, scarring, or something of that sort, and it would have been really nice to have seen them earlier and acted upon them then,” the pediatric dermatologist said.

The guidelines recommend intervention or referral by 1 month of age, ideally. Guidance is provided about the use of oral propranolol as first-line therapy.

“Propranolol is something that has been a real game changer for us,” he noted. “Many people continue to be worried about side effects in using this, particularly in the young childhood population, but this paper shows pretty clearly that hypotension or bradycardia is not a real concern. I never hospitalize these patients for propranolol therapy except in high-risk populations: very preemie, any history of breathing problems. We check the blood pressure and heart rate at baseline, again at 7-10 days, and at every visit. We’ve never found any significant drop in blood pressure.”

Dr. Levy reported financial relationships with half a dozen pharmaceutical companies, none relevant to his presentation.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – Reassuring evidence of the safety of oral propranolol for treatment of complicated infantile hemangiomas in patients with PHACE syndrome comes from a recent multicenter study.

Oral propranolol is now well-ensconced as first-line therapy for complicated infantile hemangiomas in otherwise healthy children. However, the beta-blocker’s use in PHACE (Posterior fossa malformations, Hemangiomas, Arterial anomalies, Cardiac defects, and Eye abnormalities) syndrome has been controversial, with concerns raised by some that it might raise the risk for arterial ischemic stroke. Not so, Moise L. Levy, MD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“I’m not suggesting you use propranolol with reckless abandon in this population, but this stroke concern is something that should be put to bed based on this study,” advised Dr. Levy, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Dell Medical School in Austin, Tex., and physician-in-chief at Dell Children’s Medical Center.

PHACE syndrome is characterized by large, thick, plaque-like hemangiomas greater than 5 cm in size, most commonly on the face, although they can be located elsewhere.

“There was concern that if you found severely altered cerebrovascular arterial flow and you put a kid on a beta-blocker you might be causing some harm. But what I will tell you is that in this recently published paper this was not in fact an issue,” he said.

Dr. Levy was not an investigator in the multicenter retrospective study, which included 76 patients with PHACE syndrome treated for infantile hemangioma with oral propranolol at 0.3 mg/kg per dose or more at 11 academic tertiary care pediatric dermatology clinics. Treatment started at a median age of 56 days.

There were no strokes, TIAs, cardiovascular events, or other significant problems associated with treatment. Twenty-nine children experienced mild adverse events: minor gastrointestinal or respiratory symptoms, and sleep disturbances were threefold more frequent than reported with placebo in another study. The investigators noted that the safety experience in their PHACE syndrome population compared favorably with that in 726 infants without PHACE syndrome who received oral propranolol for hemangiomas, where the incidence of serious adverse events on treatment was 0.4% (JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Dec 11. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3839).

‘Hemangiomas – but we were taught that they go away’

Dr. Levy gave a shout-out to the American Academy of Pediatrics for publishing interdisciplinary expert consensus-based practice guidelines for the management of infantile hemangiomas, which he praised as “quite well done” (Pediatrics. 2019 Jan;143[1]. pii: e20183475. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3475).

Following release of the guidelines last year, he and other pediatric vascular anomalies experts saw an uptick in referrals from general pediatricians, which has since tapered off.

“It’s probably like for all of us: We read an article, it’s fresh on the mind, then you forget about the article and what you’ve read. So we need a little reinforcement from a learning perspective. This is a great article,” he said.

The guidelines debunk as myth the classic teaching that infantile hemangiomas go away. Explicit information is provided about the high-risk anatomic sites warranting consideration for early referral, including the periocular, lumbosacral, and perineal areas, the lip, and lower face.

“The major point is early identification of those lesions requiring evaluation and intervention. Hemangiomas generally speaking are at their ultimate size by 3-5 months of age. The bottom line is if you think something needs to be done, please send that patient, or act upon that patient, sooner rather than later. I can’t tell you how many cases of hemangiomas I’ve seen when the kid is 18 months of age, 3 years of age, 5 years, with a large area of redundant skin, scarring, or something of that sort, and it would have been really nice to have seen them earlier and acted upon them then,” the pediatric dermatologist said.

The guidelines recommend intervention or referral by 1 month of age, ideally. Guidance is provided about the use of oral propranolol as first-line therapy.

“Propranolol is something that has been a real game changer for us,” he noted. “Many people continue to be worried about side effects in using this, particularly in the young childhood population, but this paper shows pretty clearly that hypotension or bradycardia is not a real concern. I never hospitalize these patients for propranolol therapy except in high-risk populations: very preemie, any history of breathing problems. We check the blood pressure and heart rate at baseline, again at 7-10 days, and at every visit. We’ve never found any significant drop in blood pressure.”

Dr. Levy reported financial relationships with half a dozen pharmaceutical companies, none relevant to his presentation.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

What I Learned From SARS in 2003 That Will Help Me Cope With COVID-19 in 2020

On March 25, 2003, I was in Vancouver at my niece’s bat mitzvah when I saw a picture of my hospital in Toronto on the television news; a story about SARS patients in Toronto. Until then, SARS had been a distant event happening in mainland China and Hong Kong; it had been something that seemed very far away and theoretical. When I returned to Toronto, we had clusters of cases in several hospitals and healthcare workers were falling ill. I was the Physician in Chief at one of those hospitals and was responsible for the clinical care delivered by physicians in the Department of Medicine. So the burden of figuring out what we were going to do fell on me and the other members of the hospital leadership team.

SARS IN 2003

As the outbreak evolved, we only knew a few things. It was a respiratory infection, likely viral, with a very high mortality rate, compared with most other viral respiratory infections. We learned the hard way that, while it was mostly transmitted by droplets, some patients were able to widely transmit it through the air, and therefore likely through ventilation systems. We knew that most infections were occurring in hospitals but there was also community spread at events like funerals. We had no test to confirm the presence of the virus and, indeed, only figured out it was a coronavirus well into the outbreak. Diagnoses were made using clinical criteria; this uncertainty was a major source of anxiety about potential community spread without direct links to known cases. We had no idea how long it was going to last, nor did we know how it would end. We were entering uncharted territory.

Decisions had to be made. Which patients needed isolation, and which did not? We made mistakes early on that caused hundreds of healthcare workers and people to be quarantined (complete isolation) for 10 days; this was a difficult situation for them, their families, and the people who had to replace them in the workplace.

Within a very short period we changed our way of life in hospitals. We screened everyone who entered with questionnaires and measured their temperatures. Once entering the hospital, we all wore N95 masks in public spaces and when in a room with another person—not just patients. We all got sore throats from wearing the masks 10 hours a day. All patients were placed in respiratory precautions, which meant that, any time we entered their rooms, we had to don all the personal protective equipment (PPE). Yet we didn’t run out of supplies. When a member of a provincial leadership team fell ill with SARS shortly after attending an in-person meeting of the committee, all the other members went into quarantine. As a result, we stopped having leadership team meetings in person, and mostly stayed in our own offices, communicating by phone and email.

The hospital took on a bizarre atmosphere: everyone in masks and little face-to-face contact. Yet outside the hospital, life went on mostly as normal. Some people wore masks on the street, but public events and businesses stayed open. Some healthcare workers were shunned in the community out of fear. But I went to another bat mitzvah and even a Stanley Cup playoff game at the height of the outbreak. Only healthcare workers were asked to stop meeting in large groups. The contrast for me was striking.

The Ontario Ministry of Health started a daily noon hour phone conference call; one physician and one administrator from every hospital in the province were on the call. I attended those for my hospital and, because I knew or taught many of the people on the line, was quickly asked to chair the calls. They were incredibly important and were a source of information exchange and emotional support for all of us. Before each call, I spoke with a person from Toronto Public Health who updated me on the number of cases and deaths. I needed to absorb that information before the calls to maintain my composure when she told the rest of the group. At times I could hear the fear in people’s voices as they described the clinical course of their patients.

Because I chaired the calls, I was asked to coordinate the study that documented the clinical outcomes of all the patients in the hopes that we could distinguish it from other common respiratory syndromes. With the help of my colleagues in the 11 hospitals that treated SARS patients, the ethics review boards, medical records personnel who copied the charts, Christopher Booth, MD, (a second- year resident at the time who headed the study), and a few medical students we were able to go from the idea to do the study to electronic publication in JAMA in 30 days.1 It was JAMA’s first experience with rapid review, and the editors there were very helpful. Working on this study was very therapeutic; it allowed me to feel I was doing something that could help.

I was scared—both for my own health and the health of my family, but also terribly frightened for the health of the people who worked here. When I went home every night, I looked at the people on the street and wondered how many would still be there a few months later. And then it all ended. (Actually, it ended twice; we let up a bit too early because we so wanted it to be over.)

COVID-19 IN 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has many similarities, but there are also significant differences. The most obvious is that because there is more community spread, life outside the hospital is much more severely disrupted. Countries have responded by sliding into more and more practices that try to limit person-to-person spread. First travel restrictions from other countries, then moral suasion to promote social distancing (which is really just physical distancing), then closing schools and nonessential businesses, and finally complete lock downs.

These events have spurred panic buying of some items (hand sanitizer, toilet paper, masks), and the fear of major disruptions of the supply chain for things like food. SARS was much more limited in its overall economic effect, though the WHO precautionary travel advisory against nonessential travel to Toronto, which lasted for only 1 week, resulted in a long-lasting reduction in tourism and a hit to the theatre business in our city.

The internet and social media have made it easier to disseminate valuable information and instructions, while at the same time easier to spread false information. But we had a lot of false information during SARS, too. One of the biggest differences for the United States (which was almost unaffected by SARS) is that the current extreme political divide creates two separate tracks of information and beliefs. A united message is very important.

Finally, the shortage of PPE in some jurisdictions, which was not an issue in Toronto during SARS, has severely heightened the fear for healthcare workers. In 2003, we also had lots of discussion about the tension between our professional duty and the safety of healthcare workers and their families (many of us separated ourselves from our families in our own homes while working clinically). To my recollection, two nurses and one physician died of SARS in Toronto. But when hospitals actually run out of PPE—something that is happening with COVID-19—those discussions take on a much more ominous tone.

LESSONS LEARNED

In my opinion, SARS was a dry run for us in Toronto and the other places in the world that it affected (Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore); one that helped us prepare in advance and will help us cope with COVID-19. But what did I personally learn from my SARS experience?

First, I learned that accurate information in these kinds of situations is hard to come by. We heard lots of rumors from people all over the world. But when I found that it was very difficult for me to figure out exactly what was going on in my own hospital (eg, who was in contact with people who fell ill or went into quarantine, how patients were faring), I realized that figuring out what was happening half way around the world from news reports was near impossible. I learned to wait for official announcements.

Second, I learned that talking to my colleagues was both therapeutic—providing emotional support and an outlet for feelings—and anxiety provoking when we overreacted to rumors.

Third, I learned that, like others, I was susceptible to exhibiting obsessive behaviors in an attempt to establish control over uncertainty. Constantly washing my hands, checking my temperature, and seeking reassuring facts from others only worked to calm me for a few minutes. And then I felt the need to do it again. This time I find myself checking my twitter account constantly; half afraid I will see something frightening, half looking for good news from people I trust. I now recognize this behavior and it helps me contain it.

Fourth, I learned that events that occurred remotely had much less effect on everyone than those that occurred close by. Having two people I knew get SARS, and then learning they recovered was perhaps the most meaningful event for me during the entire episode.

Finally, I learned that in the end I and the people I care about survived—nothing bad happened to us. The world did not end after SARS. It took me about a year, including some time with a terrific psychiatrist, to realize I was safe after all. And that realization is what I am most hanging on to today.

Acknowledgments

Sanjay Saint (University of Michigan), Christopher Booth (Queens University), and Sagar Rohailla (University of Toronto) provided comments on an earlier draft. None were compensated for doing so.

1. Booth C, Matukas LM, Tomlinson GA, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 144 patients with SARS in the greater Toronto area. JAMA. 2003;289(21):2801-2809. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.21.JOC30885.

On March 25, 2003, I was in Vancouver at my niece’s bat mitzvah when I saw a picture of my hospital in Toronto on the television news; a story about SARS patients in Toronto. Until then, SARS had been a distant event happening in mainland China and Hong Kong; it had been something that seemed very far away and theoretical. When I returned to Toronto, we had clusters of cases in several hospitals and healthcare workers were falling ill. I was the Physician in Chief at one of those hospitals and was responsible for the clinical care delivered by physicians in the Department of Medicine. So the burden of figuring out what we were going to do fell on me and the other members of the hospital leadership team.

SARS IN 2003

As the outbreak evolved, we only knew a few things. It was a respiratory infection, likely viral, with a very high mortality rate, compared with most other viral respiratory infections. We learned the hard way that, while it was mostly transmitted by droplets, some patients were able to widely transmit it through the air, and therefore likely through ventilation systems. We knew that most infections were occurring in hospitals but there was also community spread at events like funerals. We had no test to confirm the presence of the virus and, indeed, only figured out it was a coronavirus well into the outbreak. Diagnoses were made using clinical criteria; this uncertainty was a major source of anxiety about potential community spread without direct links to known cases. We had no idea how long it was going to last, nor did we know how it would end. We were entering uncharted territory.

Decisions had to be made. Which patients needed isolation, and which did not? We made mistakes early on that caused hundreds of healthcare workers and people to be quarantined (complete isolation) for 10 days; this was a difficult situation for them, their families, and the people who had to replace them in the workplace.

Within a very short period we changed our way of life in hospitals. We screened everyone who entered with questionnaires and measured their temperatures. Once entering the hospital, we all wore N95 masks in public spaces and when in a room with another person—not just patients. We all got sore throats from wearing the masks 10 hours a day. All patients were placed in respiratory precautions, which meant that, any time we entered their rooms, we had to don all the personal protective equipment (PPE). Yet we didn’t run out of supplies. When a member of a provincial leadership team fell ill with SARS shortly after attending an in-person meeting of the committee, all the other members went into quarantine. As a result, we stopped having leadership team meetings in person, and mostly stayed in our own offices, communicating by phone and email.

The hospital took on a bizarre atmosphere: everyone in masks and little face-to-face contact. Yet outside the hospital, life went on mostly as normal. Some people wore masks on the street, but public events and businesses stayed open. Some healthcare workers were shunned in the community out of fear. But I went to another bat mitzvah and even a Stanley Cup playoff game at the height of the outbreak. Only healthcare workers were asked to stop meeting in large groups. The contrast for me was striking.

The Ontario Ministry of Health started a daily noon hour phone conference call; one physician and one administrator from every hospital in the province were on the call. I attended those for my hospital and, because I knew or taught many of the people on the line, was quickly asked to chair the calls. They were incredibly important and were a source of information exchange and emotional support for all of us. Before each call, I spoke with a person from Toronto Public Health who updated me on the number of cases and deaths. I needed to absorb that information before the calls to maintain my composure when she told the rest of the group. At times I could hear the fear in people’s voices as they described the clinical course of their patients.

Because I chaired the calls, I was asked to coordinate the study that documented the clinical outcomes of all the patients in the hopes that we could distinguish it from other common respiratory syndromes. With the help of my colleagues in the 11 hospitals that treated SARS patients, the ethics review boards, medical records personnel who copied the charts, Christopher Booth, MD, (a second- year resident at the time who headed the study), and a few medical students we were able to go from the idea to do the study to electronic publication in JAMA in 30 days.1 It was JAMA’s first experience with rapid review, and the editors there were very helpful. Working on this study was very therapeutic; it allowed me to feel I was doing something that could help.

I was scared—both for my own health and the health of my family, but also terribly frightened for the health of the people who worked here. When I went home every night, I looked at the people on the street and wondered how many would still be there a few months later. And then it all ended. (Actually, it ended twice; we let up a bit too early because we so wanted it to be over.)

COVID-19 IN 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has many similarities, but there are also significant differences. The most obvious is that because there is more community spread, life outside the hospital is much more severely disrupted. Countries have responded by sliding into more and more practices that try to limit person-to-person spread. First travel restrictions from other countries, then moral suasion to promote social distancing (which is really just physical distancing), then closing schools and nonessential businesses, and finally complete lock downs.

These events have spurred panic buying of some items (hand sanitizer, toilet paper, masks), and the fear of major disruptions of the supply chain for things like food. SARS was much more limited in its overall economic effect, though the WHO precautionary travel advisory against nonessential travel to Toronto, which lasted for only 1 week, resulted in a long-lasting reduction in tourism and a hit to the theatre business in our city.

The internet and social media have made it easier to disseminate valuable information and instructions, while at the same time easier to spread false information. But we had a lot of false information during SARS, too. One of the biggest differences for the United States (which was almost unaffected by SARS) is that the current extreme political divide creates two separate tracks of information and beliefs. A united message is very important.

Finally, the shortage of PPE in some jurisdictions, which was not an issue in Toronto during SARS, has severely heightened the fear for healthcare workers. In 2003, we also had lots of discussion about the tension between our professional duty and the safety of healthcare workers and their families (many of us separated ourselves from our families in our own homes while working clinically). To my recollection, two nurses and one physician died of SARS in Toronto. But when hospitals actually run out of PPE—something that is happening with COVID-19—those discussions take on a much more ominous tone.

LESSONS LEARNED

In my opinion, SARS was a dry run for us in Toronto and the other places in the world that it affected (Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore); one that helped us prepare in advance and will help us cope with COVID-19. But what did I personally learn from my SARS experience?

First, I learned that accurate information in these kinds of situations is hard to come by. We heard lots of rumors from people all over the world. But when I found that it was very difficult for me to figure out exactly what was going on in my own hospital (eg, who was in contact with people who fell ill or went into quarantine, how patients were faring), I realized that figuring out what was happening half way around the world from news reports was near impossible. I learned to wait for official announcements.

Second, I learned that talking to my colleagues was both therapeutic—providing emotional support and an outlet for feelings—and anxiety provoking when we overreacted to rumors.

Third, I learned that, like others, I was susceptible to exhibiting obsessive behaviors in an attempt to establish control over uncertainty. Constantly washing my hands, checking my temperature, and seeking reassuring facts from others only worked to calm me for a few minutes. And then I felt the need to do it again. This time I find myself checking my twitter account constantly; half afraid I will see something frightening, half looking for good news from people I trust. I now recognize this behavior and it helps me contain it.

Fourth, I learned that events that occurred remotely had much less effect on everyone than those that occurred close by. Having two people I knew get SARS, and then learning they recovered was perhaps the most meaningful event for me during the entire episode.

Finally, I learned that in the end I and the people I care about survived—nothing bad happened to us. The world did not end after SARS. It took me about a year, including some time with a terrific psychiatrist, to realize I was safe after all. And that realization is what I am most hanging on to today.

Acknowledgments

Sanjay Saint (University of Michigan), Christopher Booth (Queens University), and Sagar Rohailla (University of Toronto) provided comments on an earlier draft. None were compensated for doing so.

On March 25, 2003, I was in Vancouver at my niece’s bat mitzvah when I saw a picture of my hospital in Toronto on the television news; a story about SARS patients in Toronto. Until then, SARS had been a distant event happening in mainland China and Hong Kong; it had been something that seemed very far away and theoretical. When I returned to Toronto, we had clusters of cases in several hospitals and healthcare workers were falling ill. I was the Physician in Chief at one of those hospitals and was responsible for the clinical care delivered by physicians in the Department of Medicine. So the burden of figuring out what we were going to do fell on me and the other members of the hospital leadership team.

SARS IN 2003

As the outbreak evolved, we only knew a few things. It was a respiratory infection, likely viral, with a very high mortality rate, compared with most other viral respiratory infections. We learned the hard way that, while it was mostly transmitted by droplets, some patients were able to widely transmit it through the air, and therefore likely through ventilation systems. We knew that most infections were occurring in hospitals but there was also community spread at events like funerals. We had no test to confirm the presence of the virus and, indeed, only figured out it was a coronavirus well into the outbreak. Diagnoses were made using clinical criteria; this uncertainty was a major source of anxiety about potential community spread without direct links to known cases. We had no idea how long it was going to last, nor did we know how it would end. We were entering uncharted territory.

Decisions had to be made. Which patients needed isolation, and which did not? We made mistakes early on that caused hundreds of healthcare workers and people to be quarantined (complete isolation) for 10 days; this was a difficult situation for them, their families, and the people who had to replace them in the workplace.

Within a very short period we changed our way of life in hospitals. We screened everyone who entered with questionnaires and measured their temperatures. Once entering the hospital, we all wore N95 masks in public spaces and when in a room with another person—not just patients. We all got sore throats from wearing the masks 10 hours a day. All patients were placed in respiratory precautions, which meant that, any time we entered their rooms, we had to don all the personal protective equipment (PPE). Yet we didn’t run out of supplies. When a member of a provincial leadership team fell ill with SARS shortly after attending an in-person meeting of the committee, all the other members went into quarantine. As a result, we stopped having leadership team meetings in person, and mostly stayed in our own offices, communicating by phone and email.

The hospital took on a bizarre atmosphere: everyone in masks and little face-to-face contact. Yet outside the hospital, life went on mostly as normal. Some people wore masks on the street, but public events and businesses stayed open. Some healthcare workers were shunned in the community out of fear. But I went to another bat mitzvah and even a Stanley Cup playoff game at the height of the outbreak. Only healthcare workers were asked to stop meeting in large groups. The contrast for me was striking.

The Ontario Ministry of Health started a daily noon hour phone conference call; one physician and one administrator from every hospital in the province were on the call. I attended those for my hospital and, because I knew or taught many of the people on the line, was quickly asked to chair the calls. They were incredibly important and were a source of information exchange and emotional support for all of us. Before each call, I spoke with a person from Toronto Public Health who updated me on the number of cases and deaths. I needed to absorb that information before the calls to maintain my composure when she told the rest of the group. At times I could hear the fear in people’s voices as they described the clinical course of their patients.

Because I chaired the calls, I was asked to coordinate the study that documented the clinical outcomes of all the patients in the hopes that we could distinguish it from other common respiratory syndromes. With the help of my colleagues in the 11 hospitals that treated SARS patients, the ethics review boards, medical records personnel who copied the charts, Christopher Booth, MD, (a second- year resident at the time who headed the study), and a few medical students we were able to go from the idea to do the study to electronic publication in JAMA in 30 days.1 It was JAMA’s first experience with rapid review, and the editors there were very helpful. Working on this study was very therapeutic; it allowed me to feel I was doing something that could help.

I was scared—both for my own health and the health of my family, but also terribly frightened for the health of the people who worked here. When I went home every night, I looked at the people on the street and wondered how many would still be there a few months later. And then it all ended. (Actually, it ended twice; we let up a bit too early because we so wanted it to be over.)

COVID-19 IN 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has many similarities, but there are also significant differences. The most obvious is that because there is more community spread, life outside the hospital is much more severely disrupted. Countries have responded by sliding into more and more practices that try to limit person-to-person spread. First travel restrictions from other countries, then moral suasion to promote social distancing (which is really just physical distancing), then closing schools and nonessential businesses, and finally complete lock downs.

These events have spurred panic buying of some items (hand sanitizer, toilet paper, masks), and the fear of major disruptions of the supply chain for things like food. SARS was much more limited in its overall economic effect, though the WHO precautionary travel advisory against nonessential travel to Toronto, which lasted for only 1 week, resulted in a long-lasting reduction in tourism and a hit to the theatre business in our city.

The internet and social media have made it easier to disseminate valuable information and instructions, while at the same time easier to spread false information. But we had a lot of false information during SARS, too. One of the biggest differences for the United States (which was almost unaffected by SARS) is that the current extreme political divide creates two separate tracks of information and beliefs. A united message is very important.

Finally, the shortage of PPE in some jurisdictions, which was not an issue in Toronto during SARS, has severely heightened the fear for healthcare workers. In 2003, we also had lots of discussion about the tension between our professional duty and the safety of healthcare workers and their families (many of us separated ourselves from our families in our own homes while working clinically). To my recollection, two nurses and one physician died of SARS in Toronto. But when hospitals actually run out of PPE—something that is happening with COVID-19—those discussions take on a much more ominous tone.

LESSONS LEARNED

In my opinion, SARS was a dry run for us in Toronto and the other places in the world that it affected (Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore); one that helped us prepare in advance and will help us cope with COVID-19. But what did I personally learn from my SARS experience?

First, I learned that accurate information in these kinds of situations is hard to come by. We heard lots of rumors from people all over the world. But when I found that it was very difficult for me to figure out exactly what was going on in my own hospital (eg, who was in contact with people who fell ill or went into quarantine, how patients were faring), I realized that figuring out what was happening half way around the world from news reports was near impossible. I learned to wait for official announcements.

Second, I learned that talking to my colleagues was both therapeutic—providing emotional support and an outlet for feelings—and anxiety provoking when we overreacted to rumors.

Third, I learned that, like others, I was susceptible to exhibiting obsessive behaviors in an attempt to establish control over uncertainty. Constantly washing my hands, checking my temperature, and seeking reassuring facts from others only worked to calm me for a few minutes. And then I felt the need to do it again. This time I find myself checking my twitter account constantly; half afraid I will see something frightening, half looking for good news from people I trust. I now recognize this behavior and it helps me contain it.

Fourth, I learned that events that occurred remotely had much less effect on everyone than those that occurred close by. Having two people I knew get SARS, and then learning they recovered was perhaps the most meaningful event for me during the entire episode.

Finally, I learned that in the end I and the people I care about survived—nothing bad happened to us. The world did not end after SARS. It took me about a year, including some time with a terrific psychiatrist, to realize I was safe after all. And that realization is what I am most hanging on to today.

Acknowledgments

Sanjay Saint (University of Michigan), Christopher Booth (Queens University), and Sagar Rohailla (University of Toronto) provided comments on an earlier draft. None were compensated for doing so.

1. Booth C, Matukas LM, Tomlinson GA, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 144 patients with SARS in the greater Toronto area. JAMA. 2003;289(21):2801-2809. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.21.JOC30885.

1. Booth C, Matukas LM, Tomlinson GA, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 144 patients with SARS in the greater Toronto area. JAMA. 2003;289(21):2801-2809. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.21.JOC30885.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Don’t call it perioral dermatitis

LAHAINA, HAWAII – , according to Jessica Sprague, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital.

Years ago, some of her senior colleagues at the children’s hospital carried out a retrospective study of 79 patients, aged 6 months to 18 years, who were treated for what’s typically called perioral dermatitis. Of note, only 40% of patients had isolated perioral involvement, while 30% of the patients had no perioral lesions at all. Perinasal lesions were present in 43%, and 25% had periocular involvement, she noted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

The peak incidence of periorificial dermatitis in this series was under age 5 years. At presentation, the rash had been present for an average of 8 months. Seventy-two percent of patients had a history of exposure to corticosteroids, most often in the form of topical steroids, but in some cases inhaled or systemic steroids.

“Obviously you want to discontinue the topical steroid. Sometimes you need to taper them off, or you can switch to a topical calcineurin inhibitor [TCI] because they tend to flare a lot when you stop their topical steroid, although there are cases of TCIs precipitating periorificial dermatitis, so keep that in mind,” Dr. Sprague said.

If a patient is on inhaled steroids by mask for asthma, switching to a tube can sometimes limit the exposure, she continued.

Her first-line therapy for mild to moderate periorificial dermatitis, and the one supported by the strongest evidence base, is metronidazole cream. Other topical agents shown to be effective include azelaic acid, sulfacetamide, clindamycin, and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Oral therapy is a good option for more extensive or recalcitrant cases.

“If parents are very anxious, like before school photos or holiday photos, sometimes I’ll use oral therapy as well. In younger kids, I prefer erythromycin at 30 mg/kg per day t.i.d. for 3-6 weeks. In kids 8 years old and up you can use doxycycline at 50-100 mg b.i.d., again for 3-6 weeks. And you have to tell them it’s going to take a while for this to go away,” Dr. Sprague said.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – , according to Jessica Sprague, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital.

Years ago, some of her senior colleagues at the children’s hospital carried out a retrospective study of 79 patients, aged 6 months to 18 years, who were treated for what’s typically called perioral dermatitis. Of note, only 40% of patients had isolated perioral involvement, while 30% of the patients had no perioral lesions at all. Perinasal lesions were present in 43%, and 25% had periocular involvement, she noted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

The peak incidence of periorificial dermatitis in this series was under age 5 years. At presentation, the rash had been present for an average of 8 months. Seventy-two percent of patients had a history of exposure to corticosteroids, most often in the form of topical steroids, but in some cases inhaled or systemic steroids.

“Obviously you want to discontinue the topical steroid. Sometimes you need to taper them off, or you can switch to a topical calcineurin inhibitor [TCI] because they tend to flare a lot when you stop their topical steroid, although there are cases of TCIs precipitating periorificial dermatitis, so keep that in mind,” Dr. Sprague said.

If a patient is on inhaled steroids by mask for asthma, switching to a tube can sometimes limit the exposure, she continued.

Her first-line therapy for mild to moderate periorificial dermatitis, and the one supported by the strongest evidence base, is metronidazole cream. Other topical agents shown to be effective include azelaic acid, sulfacetamide, clindamycin, and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Oral therapy is a good option for more extensive or recalcitrant cases.

“If parents are very anxious, like before school photos or holiday photos, sometimes I’ll use oral therapy as well. In younger kids, I prefer erythromycin at 30 mg/kg per day t.i.d. for 3-6 weeks. In kids 8 years old and up you can use doxycycline at 50-100 mg b.i.d., again for 3-6 weeks. And you have to tell them it’s going to take a while for this to go away,” Dr. Sprague said.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – , according to Jessica Sprague, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital.

Years ago, some of her senior colleagues at the children’s hospital carried out a retrospective study of 79 patients, aged 6 months to 18 years, who were treated for what’s typically called perioral dermatitis. Of note, only 40% of patients had isolated perioral involvement, while 30% of the patients had no perioral lesions at all. Perinasal lesions were present in 43%, and 25% had periocular involvement, she noted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

The peak incidence of periorificial dermatitis in this series was under age 5 years. At presentation, the rash had been present for an average of 8 months. Seventy-two percent of patients had a history of exposure to corticosteroids, most often in the form of topical steroids, but in some cases inhaled or systemic steroids.

“Obviously you want to discontinue the topical steroid. Sometimes you need to taper them off, or you can switch to a topical calcineurin inhibitor [TCI] because they tend to flare a lot when you stop their topical steroid, although there are cases of TCIs precipitating periorificial dermatitis, so keep that in mind,” Dr. Sprague said.

If a patient is on inhaled steroids by mask for asthma, switching to a tube can sometimes limit the exposure, she continued.

Her first-line therapy for mild to moderate periorificial dermatitis, and the one supported by the strongest evidence base, is metronidazole cream. Other topical agents shown to be effective include azelaic acid, sulfacetamide, clindamycin, and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Oral therapy is a good option for more extensive or recalcitrant cases.

“If parents are very anxious, like before school photos or holiday photos, sometimes I’ll use oral therapy as well. In younger kids, I prefer erythromycin at 30 mg/kg per day t.i.d. for 3-6 weeks. In kids 8 years old and up you can use doxycycline at 50-100 mg b.i.d., again for 3-6 weeks. And you have to tell them it’s going to take a while for this to go away,” Dr. Sprague said.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

What is seronegative rheumatoid arthritis, anyway?

MAUI, HAWAII – Viewing seronegative rheumatoid arthritis as something akin to RA-lite would be a big mistake, John J. Cush, MD, asserted at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“It’s not a benign subtype of RA. And then again, it may not be RA,” Dr. Cush observed,

“Seronegative RA means that either you need to get serious about what is probably badass disease or you need to reevaluate whether this really is RA and your need for DMARDs [disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs] in an ongoing fashion,” the rheumatologist said. “Always reconsider whether they need less therapy or maybe no therapy at all. Maybe they had inflammation at one point and now they’re left with degenerative and mechanical changes that don’t require a DMARD or biologic.”

He highlighted a Finnish 10-year, prospective, observational study that sheds light on the subject. The study demonstrated that seronegative RA is seldom what it at first seems. The Finnish rheumatologists followed 435 consecutive patients initially diagnosed as having seronegative early RA. The structured follow-up entailed four or five interdisciplinary clinic visits within the first 2 years after diagnosis and again at 5 and 10 years.

By the 10-year mark only 4 of the 435 initially seronegative RA patients had been reclassified as having seropositive RA, while another 9 were reclassified as having erosive RA based upon the development of pathognomonic joint lesions. That’s a paltry 3% reclassification rate to classic RA.

Nearly two-thirds of patients were ultimately reclassified within 10 years as they evolved into diagnoses other than their original seronegative RA. The most common included nonerosive polymyalgia rheumatica in 16% of participants, psoriatic arthritis in 11%, osteoarthritis in 10%, spondyloarthritis in 8.7%, gout in 2.3%, and pseudogout in 3.9%.

“I think that’s sobering for you if you’re taking care of these patients, that maybe you need to rethink the diagnosis at every visit or at periodic intervals, especially if you’re going to change therapy,” advised Dr. Cush, who is professor of medicine and rheumatology at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, and director of clinical rheumatology at the Baylor Research Institute.

The Finnish rheumatologists observed that their findings have important implications both for clinical practice and for research, since RA clinical trials typically include a substantial proportion of seronegative patients.

“If seronegative patients are treated according to the treatment guidelines for progressive RA, a substantial proportion of patients is exposed to unnecessary long-term medication,” the investigators wrote, adding that their “results suggest that it may not be reasonable to study seronegative arthritis patients as a homogeneous entity in RA studies.”

The best recent data suggests about 15% of RA patients are seronegative, Dr. Cush said.

Delay in diagnosis is common in seronegative RA, as highlighted in a recent population-based study by Mayo Clinic rheumatologists. They reported that the median time from first joint swelling to diagnosis of seronegative RA using the 2010 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism criteria was 187 days, compared with a mere 11 days for seropositive RA. The median time to DMARD initiation was longer, too. Half of seropositive RA patients achieved remission within 5 years, as did 28% of seronegative patients, prompting the investigators to conclude “the window of opportunity for intervention may be more frequently missed in this group.”

Choosing the best treatment

Several medications appear to have greater efficacy in seropositive than seronegative RA patients. For example, a meta-analysis of four randomized trials including a collective 2,177 RA patients assigned 2:1 to rituximab (Rituxan) or placebo concluded that 75% of seropositive RA patients had a EULAR moderate or good response at week 24 on the biologic, compared with 44% of seronegative patients.

“Would you not use rituximab in someone who’s seronegative? No, I actually would use it. I may not rush to use it as much, maybe give it earlier in someone who’s seropositive, but I’ve used rituximab in seronegative patients who’ve done just fine,” according to Dr. Cush.

The published experience with abatacept (Orencia) is mixed, most of it coming from European observational datasets. On balance though, 80% of the articles addressing the issue have concluded that response rates to the biologic are better in seropositive RA, he continued.

Australian investigators who pooled data from five phase 3 randomized clinical trials of tofacitinib (Xeljanz) in RA concluded that double-positive patients – that is, those who were seropositive for both rheumatoid factor and anti–citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) – were roughly twice as likely to achieve ACR20 and ACR50 responses to the oral Janus kinase inhibitor at either 5 or 10 mg twice daily than patients who were double negative.

“Double positivity is very important in prognosis and severity, compared to single positivity,” the rheumatologist observed. “I think you should worry most about the patients who have the highest titers of rheumatoid factor and ACPA.”

Asked about the merits of supplemental laboratory testing for serum 14-3-3 eta, a proposed novel biomarker in RA, as well as for anti–carbamylated protein antibodies (anti-CarP), Dr. Cush replied that it’s unclear that the additional testing is really worthwhile.

“Ordering more tests doesn’t make us smarter,” he commented. “Quite simply, with rheumatoid factor and ACPA, adding one on top of the other, you just gain maybe 10% more certainty in the diagnosis. Adding anti-CarP antibodies or serum 14-3-3 eta doesn’t add more than a few percentage points, but now you’ve quadrupled the cost of testing.”

Dr. Cush reported receiving research funding from and/or serving as a consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – Viewing seronegative rheumatoid arthritis as something akin to RA-lite would be a big mistake, John J. Cush, MD, asserted at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“It’s not a benign subtype of RA. And then again, it may not be RA,” Dr. Cush observed,

“Seronegative RA means that either you need to get serious about what is probably badass disease or you need to reevaluate whether this really is RA and your need for DMARDs [disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs] in an ongoing fashion,” the rheumatologist said. “Always reconsider whether they need less therapy or maybe no therapy at all. Maybe they had inflammation at one point and now they’re left with degenerative and mechanical changes that don’t require a DMARD or biologic.”

He highlighted a Finnish 10-year, prospective, observational study that sheds light on the subject. The study demonstrated that seronegative RA is seldom what it at first seems. The Finnish rheumatologists followed 435 consecutive patients initially diagnosed as having seronegative early RA. The structured follow-up entailed four or five interdisciplinary clinic visits within the first 2 years after diagnosis and again at 5 and 10 years.

By the 10-year mark only 4 of the 435 initially seronegative RA patients had been reclassified as having seropositive RA, while another 9 were reclassified as having erosive RA based upon the development of pathognomonic joint lesions. That’s a paltry 3% reclassification rate to classic RA.

Nearly two-thirds of patients were ultimately reclassified within 10 years as they evolved into diagnoses other than their original seronegative RA. The most common included nonerosive polymyalgia rheumatica in 16% of participants, psoriatic arthritis in 11%, osteoarthritis in 10%, spondyloarthritis in 8.7%, gout in 2.3%, and pseudogout in 3.9%.

“I think that’s sobering for you if you’re taking care of these patients, that maybe you need to rethink the diagnosis at every visit or at periodic intervals, especially if you’re going to change therapy,” advised Dr. Cush, who is professor of medicine and rheumatology at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, and director of clinical rheumatology at the Baylor Research Institute.

The Finnish rheumatologists observed that their findings have important implications both for clinical practice and for research, since RA clinical trials typically include a substantial proportion of seronegative patients.

“If seronegative patients are treated according to the treatment guidelines for progressive RA, a substantial proportion of patients is exposed to unnecessary long-term medication,” the investigators wrote, adding that their “results suggest that it may not be reasonable to study seronegative arthritis patients as a homogeneous entity in RA studies.”

The best recent data suggests about 15% of RA patients are seronegative, Dr. Cush said.

Delay in diagnosis is common in seronegative RA, as highlighted in a recent population-based study by Mayo Clinic rheumatologists. They reported that the median time from first joint swelling to diagnosis of seronegative RA using the 2010 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism criteria was 187 days, compared with a mere 11 days for seropositive RA. The median time to DMARD initiation was longer, too. Half of seropositive RA patients achieved remission within 5 years, as did 28% of seronegative patients, prompting the investigators to conclude “the window of opportunity for intervention may be more frequently missed in this group.”

Choosing the best treatment

Several medications appear to have greater efficacy in seropositive than seronegative RA patients. For example, a meta-analysis of four randomized trials including a collective 2,177 RA patients assigned 2:1 to rituximab (Rituxan) or placebo concluded that 75% of seropositive RA patients had a EULAR moderate or good response at week 24 on the biologic, compared with 44% of seronegative patients.

“Would you not use rituximab in someone who’s seronegative? No, I actually would use it. I may not rush to use it as much, maybe give it earlier in someone who’s seropositive, but I’ve used rituximab in seronegative patients who’ve done just fine,” according to Dr. Cush.

The published experience with abatacept (Orencia) is mixed, most of it coming from European observational datasets. On balance though, 80% of the articles addressing the issue have concluded that response rates to the biologic are better in seropositive RA, he continued.

Australian investigators who pooled data from five phase 3 randomized clinical trials of tofacitinib (Xeljanz) in RA concluded that double-positive patients – that is, those who were seropositive for both rheumatoid factor and anti–citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) – were roughly twice as likely to achieve ACR20 and ACR50 responses to the oral Janus kinase inhibitor at either 5 or 10 mg twice daily than patients who were double negative.

“Double positivity is very important in prognosis and severity, compared to single positivity,” the rheumatologist observed. “I think you should worry most about the patients who have the highest titers of rheumatoid factor and ACPA.”

Asked about the merits of supplemental laboratory testing for serum 14-3-3 eta, a proposed novel biomarker in RA, as well as for anti–carbamylated protein antibodies (anti-CarP), Dr. Cush replied that it’s unclear that the additional testing is really worthwhile.

“Ordering more tests doesn’t make us smarter,” he commented. “Quite simply, with rheumatoid factor and ACPA, adding one on top of the other, you just gain maybe 10% more certainty in the diagnosis. Adding anti-CarP antibodies or serum 14-3-3 eta doesn’t add more than a few percentage points, but now you’ve quadrupled the cost of testing.”

Dr. Cush reported receiving research funding from and/or serving as a consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – Viewing seronegative rheumatoid arthritis as something akin to RA-lite would be a big mistake, John J. Cush, MD, asserted at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“It’s not a benign subtype of RA. And then again, it may not be RA,” Dr. Cush observed,

“Seronegative RA means that either you need to get serious about what is probably badass disease or you need to reevaluate whether this really is RA and your need for DMARDs [disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs] in an ongoing fashion,” the rheumatologist said. “Always reconsider whether they need less therapy or maybe no therapy at all. Maybe they had inflammation at one point and now they’re left with degenerative and mechanical changes that don’t require a DMARD or biologic.”

He highlighted a Finnish 10-year, prospective, observational study that sheds light on the subject. The study demonstrated that seronegative RA is seldom what it at first seems. The Finnish rheumatologists followed 435 consecutive patients initially diagnosed as having seronegative early RA. The structured follow-up entailed four or five interdisciplinary clinic visits within the first 2 years after diagnosis and again at 5 and 10 years.

By the 10-year mark only 4 of the 435 initially seronegative RA patients had been reclassified as having seropositive RA, while another 9 were reclassified as having erosive RA based upon the development of pathognomonic joint lesions. That’s a paltry 3% reclassification rate to classic RA.

Nearly two-thirds of patients were ultimately reclassified within 10 years as they evolved into diagnoses other than their original seronegative RA. The most common included nonerosive polymyalgia rheumatica in 16% of participants, psoriatic arthritis in 11%, osteoarthritis in 10%, spondyloarthritis in 8.7%, gout in 2.3%, and pseudogout in 3.9%.

“I think that’s sobering for you if you’re taking care of these patients, that maybe you need to rethink the diagnosis at every visit or at periodic intervals, especially if you’re going to change therapy,” advised Dr. Cush, who is professor of medicine and rheumatology at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, and director of clinical rheumatology at the Baylor Research Institute.

The Finnish rheumatologists observed that their findings have important implications both for clinical practice and for research, since RA clinical trials typically include a substantial proportion of seronegative patients.

“If seronegative patients are treated according to the treatment guidelines for progressive RA, a substantial proportion of patients is exposed to unnecessary long-term medication,” the investigators wrote, adding that their “results suggest that it may not be reasonable to study seronegative arthritis patients as a homogeneous entity in RA studies.”

The best recent data suggests about 15% of RA patients are seronegative, Dr. Cush said.

Delay in diagnosis is common in seronegative RA, as highlighted in a recent population-based study by Mayo Clinic rheumatologists. They reported that the median time from first joint swelling to diagnosis of seronegative RA using the 2010 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism criteria was 187 days, compared with a mere 11 days for seropositive RA. The median time to DMARD initiation was longer, too. Half of seropositive RA patients achieved remission within 5 years, as did 28% of seronegative patients, prompting the investigators to conclude “the window of opportunity for intervention may be more frequently missed in this group.”

Choosing the best treatment

Several medications appear to have greater efficacy in seropositive than seronegative RA patients. For example, a meta-analysis of four randomized trials including a collective 2,177 RA patients assigned 2:1 to rituximab (Rituxan) or placebo concluded that 75% of seropositive RA patients had a EULAR moderate or good response at week 24 on the biologic, compared with 44% of seronegative patients.

“Would you not use rituximab in someone who’s seronegative? No, I actually would use it. I may not rush to use it as much, maybe give it earlier in someone who’s seropositive, but I’ve used rituximab in seronegative patients who’ve done just fine,” according to Dr. Cush.

The published experience with abatacept (Orencia) is mixed, most of it coming from European observational datasets. On balance though, 80% of the articles addressing the issue have concluded that response rates to the biologic are better in seropositive RA, he continued.

Australian investigators who pooled data from five phase 3 randomized clinical trials of tofacitinib (Xeljanz) in RA concluded that double-positive patients – that is, those who were seropositive for both rheumatoid factor and anti–citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) – were roughly twice as likely to achieve ACR20 and ACR50 responses to the oral Janus kinase inhibitor at either 5 or 10 mg twice daily than patients who were double negative.

“Double positivity is very important in prognosis and severity, compared to single positivity,” the rheumatologist observed. “I think you should worry most about the patients who have the highest titers of rheumatoid factor and ACPA.”

Asked about the merits of supplemental laboratory testing for serum 14-3-3 eta, a proposed novel biomarker in RA, as well as for anti–carbamylated protein antibodies (anti-CarP), Dr. Cush replied that it’s unclear that the additional testing is really worthwhile.

“Ordering more tests doesn’t make us smarter,” he commented. “Quite simply, with rheumatoid factor and ACPA, adding one on top of the other, you just gain maybe 10% more certainty in the diagnosis. Adding anti-CarP antibodies or serum 14-3-3 eta doesn’t add more than a few percentage points, but now you’ve quadrupled the cost of testing.”

Dr. Cush reported receiving research funding from and/or serving as a consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM RWCS 2020

CLEOPATRA: Pertuzumab has long-term benefit in HER2+ breast cancer

, with nearly 40% of patients achieving long-term survival, the CLEOPATRA end-of-study analysis shows.

The regimen, combining dual HER2 targeting with chemotherapy, became standard of care in this population as a result of its good efficacy and safety relative to placebo, first established in the phase 3, randomized trial 8 years ago (N Engl J Med. 2012;366:109-19).

Trial updates since then, most recently at a median follow-up of 50 months (N Engl J Med. 2015;372:724-34), have shown clear progression-free and overall survival benefits, with acceptable cardiac and other toxicity.

Investigators led by Sandra M. Swain, MD, of Georgetown University, Washington, performed a final analysis of data from the 808 patients in CLEOPATRA, now at a median follow-up of 99.9 months.

Results reported in The Lancet Oncology showed that, compared with placebo, pertuzumab prolonged investigator-assessed progression-free survival by 6.3 months (the same as that seen in the previous update) and prolonged overall survival by 16.3 months (up from 15.7 months in the previous update).

At 8 years, 37% of patients in the pertuzumab group were still alive, and 16% were still alive without progression.

“The combination of pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel remains the standard of care for the first-line treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer, owing to its overall survival benefits and maintained long-term overall and cardiac safety,” Dr. Swain and coinvestigators concluded. “Prospective identification of patients who will be long-term responders to treatment is an area for future research.”

In an accompanying comment, Matteo Lambertini, MD, PhD, of IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino in Genova, Italy, and Ines Vaz-Luis, MD, of Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France, contended that these results, “which are also observed in real-world datasets, challenge the concept of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer being an incurable disease and open the path to several interconnected clinical and research questions.”

Those questions include the optimal duration of anti-HER2 maintenance therapy in patients without disease progression, best strategies for combining this systemic therapy with local treatment to further improve survival, and new markers to better identify patients likely to be long-term responders, who might benefit from a curative approach, the authors elaborated. They noted that more than half of CLEOPATRA patients had de novo stage IV disease.

“The performance of the current standard pertuzumab-based first-line treatment in patients previously exposed to adjuvant or neoadjuvant anti-HER2 therapy remains to be clarified,” the authors wrote. “Results from several ongoing prospective cohort studies investigating real-world patterns of care and outcomes of patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer will help to clarify this important issue and optimize treatment sequencing.”

Study details

The end-of-study analysis showed that median progression-free survival was 18.7 months with pertuzumab and 12.4 months with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.69; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.81). The 8-year landmark progression-free survival rate was 16% with the former and 10% with the latter.

The median overall survival was 57.1 months with pertuzumab and 40.8 months with placebo (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58-0.82). The 8-year landmark overall survival rate was 37% with the former and 23% with the latter.

A comparison of patients who did and did not achieve long-term response showed that, in both treatment groups, the former more often had tumors that were 3+ positive by HER2 immunohistochemistry and PIK3CA wild-type tumors. The leading grade 3 or 4 adverse event was neutropenia, seen in 49% of patients in the pertuzumab group and 46% of those in the placebo group. The rate of treatment-related death was 1% and 2%, respectively.

Since the last update, only two additional serious adverse events were reported: one case of heart failure and one case of symptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients given pertuzumab.

The CLEOPATRA trial was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche and Genentech. Dr. Swain and coauthors disclosed relationships with these and other companies. Dr. Lambertini disclosed relationships with Roche, Theramex, and Takeda. Dr. Vaz-Luis disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Kephren, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Swain SM et al. Lancet Oncol. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30863-0; Lambertini M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30058-9.

, with nearly 40% of patients achieving long-term survival, the CLEOPATRA end-of-study analysis shows.

The regimen, combining dual HER2 targeting with chemotherapy, became standard of care in this population as a result of its good efficacy and safety relative to placebo, first established in the phase 3, randomized trial 8 years ago (N Engl J Med. 2012;366:109-19).

Trial updates since then, most recently at a median follow-up of 50 months (N Engl J Med. 2015;372:724-34), have shown clear progression-free and overall survival benefits, with acceptable cardiac and other toxicity.

Investigators led by Sandra M. Swain, MD, of Georgetown University, Washington, performed a final analysis of data from the 808 patients in CLEOPATRA, now at a median follow-up of 99.9 months.

Results reported in The Lancet Oncology showed that, compared with placebo, pertuzumab prolonged investigator-assessed progression-free survival by 6.3 months (the same as that seen in the previous update) and prolonged overall survival by 16.3 months (up from 15.7 months in the previous update).

At 8 years, 37% of patients in the pertuzumab group were still alive, and 16% were still alive without progression.

“The combination of pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel remains the standard of care for the first-line treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer, owing to its overall survival benefits and maintained long-term overall and cardiac safety,” Dr. Swain and coinvestigators concluded. “Prospective identification of patients who will be long-term responders to treatment is an area for future research.”

In an accompanying comment, Matteo Lambertini, MD, PhD, of IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino in Genova, Italy, and Ines Vaz-Luis, MD, of Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France, contended that these results, “which are also observed in real-world datasets, challenge the concept of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer being an incurable disease and open the path to several interconnected clinical and research questions.”

Those questions include the optimal duration of anti-HER2 maintenance therapy in patients without disease progression, best strategies for combining this systemic therapy with local treatment to further improve survival, and new markers to better identify patients likely to be long-term responders, who might benefit from a curative approach, the authors elaborated. They noted that more than half of CLEOPATRA patients had de novo stage IV disease.

“The performance of the current standard pertuzumab-based first-line treatment in patients previously exposed to adjuvant or neoadjuvant anti-HER2 therapy remains to be clarified,” the authors wrote. “Results from several ongoing prospective cohort studies investigating real-world patterns of care and outcomes of patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer will help to clarify this important issue and optimize treatment sequencing.”

Study details

The end-of-study analysis showed that median progression-free survival was 18.7 months with pertuzumab and 12.4 months with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.69; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.81). The 8-year landmark progression-free survival rate was 16% with the former and 10% with the latter.

The median overall survival was 57.1 months with pertuzumab and 40.8 months with placebo (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58-0.82). The 8-year landmark overall survival rate was 37% with the former and 23% with the latter.

A comparison of patients who did and did not achieve long-term response showed that, in both treatment groups, the former more often had tumors that were 3+ positive by HER2 immunohistochemistry and PIK3CA wild-type tumors. The leading grade 3 or 4 adverse event was neutropenia, seen in 49% of patients in the pertuzumab group and 46% of those in the placebo group. The rate of treatment-related death was 1% and 2%, respectively.