User login

No difference between ipilimumab/nivolumab combo and immunotherapy plus VEGF for metastatic RCC

There is no significant difference in response or survival rates between the combination of ipilimumab/nivolumab (ipi-nivo) and immuno-oncology plus vascular endothelial growth factor inhibition (IOVE) for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

Therefore, the treatment should probably be directed by patient preferences, among other things, Shaan Dudani, MD, and colleagues wrote in European Oncology.

“Given the current lack of evidence to suggest a difference in efficacy between treatment strategies, patients, clinicians and policy makers are likely to take into account other considerations, such as toxicity, cost, logistics, prognostic categories, and patient preferences in deciding between the various front-line [immuno-oncology] combination regimens,” wrote Dr. Dudani, of the University of Calgary, and coauthors.

The team examined response rates among 263 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma from the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) dataset. Patients treated with any first-line IOVE combination (n = 113) were compared with those treated with ipi-nivo (n = 75). Patients were about 62 years old. The most common sites of metastasis were liver (about 20%) and bone (about 33%), and about 20% had sarcomatoid features (about 20%). Most (about 75%) had multiple metastatic sites.

Thirty percent of those in the IOVE group and 40% in the ipi-nivo group had received second-line treatments. These included axitinib, levantinib plus severolimus, nivolumab alone, pazopanib, and sunitinib, as well as other treatments.

At a mean follow-up of 11.7 months, the response rates were 33% for IOVE and 40% for ipi-nivo. This difference was not statistically significant (between group difference, 7%; 95% confidence interval, –8% to 22%; P = .4). Complete response occurred in 2% in IOVE and 5% of the ipi-nivo group.

The time to treatment failure was 14.3 months for IOVE and 10.2 months for ipi-nivo – again not a significant difference (P = .2). Time to next treatment also was not significantly different (19.7 vs. 17.9 months; P = .4). Neither group met the study’s overall survival goal.

After adjustment for IMDC risk score, hazard ratios for death were 0.71 for IOVE and 1.74 for ipi-nivo. There were no significant between-group differences when comparing intermediate- and poor-risk patients or when the analysis was restricted only to favorable-risk patients. Among 55 who received second-line therapy, there was also no significant difference in time to treatment failure.

“It was interesting, though not surprising, to observe that the majority [88%] of second-line therapies in this cohort were VEGF-based following ipi-nivo vs. IOVE combinations,” the authors noted. “The higher response rates observed in patients receiving second-line VEGF combinations is noteworthy and thought provoking. Biologically, it is plausible that VEGF-based second-line therapy would be more likely to be effective in the VEGF-naive ipi-nivo cohort. It remains to be seen whether the numerical difference in time to treatment failure becomes significant with increased sample size and further follow-up, and whether this contributes to differences in overall survival, which ultimately impacts treatment selections in the first-line setting.”

Dr. Dudani had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Dudani S et al. Euro Onc. 2019 Aug 22. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.07.048.

There is no significant difference in response or survival rates between the combination of ipilimumab/nivolumab (ipi-nivo) and immuno-oncology plus vascular endothelial growth factor inhibition (IOVE) for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

Therefore, the treatment should probably be directed by patient preferences, among other things, Shaan Dudani, MD, and colleagues wrote in European Oncology.

“Given the current lack of evidence to suggest a difference in efficacy between treatment strategies, patients, clinicians and policy makers are likely to take into account other considerations, such as toxicity, cost, logistics, prognostic categories, and patient preferences in deciding between the various front-line [immuno-oncology] combination regimens,” wrote Dr. Dudani, of the University of Calgary, and coauthors.

The team examined response rates among 263 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma from the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) dataset. Patients treated with any first-line IOVE combination (n = 113) were compared with those treated with ipi-nivo (n = 75). Patients were about 62 years old. The most common sites of metastasis were liver (about 20%) and bone (about 33%), and about 20% had sarcomatoid features (about 20%). Most (about 75%) had multiple metastatic sites.

Thirty percent of those in the IOVE group and 40% in the ipi-nivo group had received second-line treatments. These included axitinib, levantinib plus severolimus, nivolumab alone, pazopanib, and sunitinib, as well as other treatments.

At a mean follow-up of 11.7 months, the response rates were 33% for IOVE and 40% for ipi-nivo. This difference was not statistically significant (between group difference, 7%; 95% confidence interval, –8% to 22%; P = .4). Complete response occurred in 2% in IOVE and 5% of the ipi-nivo group.

The time to treatment failure was 14.3 months for IOVE and 10.2 months for ipi-nivo – again not a significant difference (P = .2). Time to next treatment also was not significantly different (19.7 vs. 17.9 months; P = .4). Neither group met the study’s overall survival goal.

After adjustment for IMDC risk score, hazard ratios for death were 0.71 for IOVE and 1.74 for ipi-nivo. There were no significant between-group differences when comparing intermediate- and poor-risk patients or when the analysis was restricted only to favorable-risk patients. Among 55 who received second-line therapy, there was also no significant difference in time to treatment failure.

“It was interesting, though not surprising, to observe that the majority [88%] of second-line therapies in this cohort were VEGF-based following ipi-nivo vs. IOVE combinations,” the authors noted. “The higher response rates observed in patients receiving second-line VEGF combinations is noteworthy and thought provoking. Biologically, it is plausible that VEGF-based second-line therapy would be more likely to be effective in the VEGF-naive ipi-nivo cohort. It remains to be seen whether the numerical difference in time to treatment failure becomes significant with increased sample size and further follow-up, and whether this contributes to differences in overall survival, which ultimately impacts treatment selections in the first-line setting.”

Dr. Dudani had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Dudani S et al. Euro Onc. 2019 Aug 22. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.07.048.

There is no significant difference in response or survival rates between the combination of ipilimumab/nivolumab (ipi-nivo) and immuno-oncology plus vascular endothelial growth factor inhibition (IOVE) for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

Therefore, the treatment should probably be directed by patient preferences, among other things, Shaan Dudani, MD, and colleagues wrote in European Oncology.

“Given the current lack of evidence to suggest a difference in efficacy between treatment strategies, patients, clinicians and policy makers are likely to take into account other considerations, such as toxicity, cost, logistics, prognostic categories, and patient preferences in deciding between the various front-line [immuno-oncology] combination regimens,” wrote Dr. Dudani, of the University of Calgary, and coauthors.

The team examined response rates among 263 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma from the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) dataset. Patients treated with any first-line IOVE combination (n = 113) were compared with those treated with ipi-nivo (n = 75). Patients were about 62 years old. The most common sites of metastasis were liver (about 20%) and bone (about 33%), and about 20% had sarcomatoid features (about 20%). Most (about 75%) had multiple metastatic sites.

Thirty percent of those in the IOVE group and 40% in the ipi-nivo group had received second-line treatments. These included axitinib, levantinib plus severolimus, nivolumab alone, pazopanib, and sunitinib, as well as other treatments.

At a mean follow-up of 11.7 months, the response rates were 33% for IOVE and 40% for ipi-nivo. This difference was not statistically significant (between group difference, 7%; 95% confidence interval, –8% to 22%; P = .4). Complete response occurred in 2% in IOVE and 5% of the ipi-nivo group.

The time to treatment failure was 14.3 months for IOVE and 10.2 months for ipi-nivo – again not a significant difference (P = .2). Time to next treatment also was not significantly different (19.7 vs. 17.9 months; P = .4). Neither group met the study’s overall survival goal.

After adjustment for IMDC risk score, hazard ratios for death were 0.71 for IOVE and 1.74 for ipi-nivo. There were no significant between-group differences when comparing intermediate- and poor-risk patients or when the analysis was restricted only to favorable-risk patients. Among 55 who received second-line therapy, there was also no significant difference in time to treatment failure.

“It was interesting, though not surprising, to observe that the majority [88%] of second-line therapies in this cohort were VEGF-based following ipi-nivo vs. IOVE combinations,” the authors noted. “The higher response rates observed in patients receiving second-line VEGF combinations is noteworthy and thought provoking. Biologically, it is plausible that VEGF-based second-line therapy would be more likely to be effective in the VEGF-naive ipi-nivo cohort. It remains to be seen whether the numerical difference in time to treatment failure becomes significant with increased sample size and further follow-up, and whether this contributes to differences in overall survival, which ultimately impacts treatment selections in the first-line setting.”

Dr. Dudani had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Dudani S et al. Euro Onc. 2019 Aug 22. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.07.048.

FROM EUROPEAN ONCOLOGY

Snapshots of an oncologist

It’s 6:30 on a Friday night, and I am triaging three admissions to the leukemia service at once. The call from the ED about you makes me pause. I recognize your name – you were my patient a few years before. At the time, you were undergoing chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia, and I cared for you during the aftermath. I now pull up your chart and fill in the gaps of the last 2 years. You got into remission and received a bone marrow transplant. For 2 years, you were cured. But today, you are back. The ED has picked up an abundance of blasts – cancer cells – in your blood. I walk to your ED gurney slowly, thinking of how to tell you this. You recognize me, too. And I can see in your eyes that you already know. “I am so sorry this is happening,” I say.

You are here for your third cycle of chemotherapy. It’s a standard check-in. The first cycle was tolerable, the second cycle was rough, and now you are exhausted. You wonder if it’s normal to be so beat up from this. You ask how much nausea is too much nausea. But your hair didn’t fall out – isn’t that strange? Is it a sure thing that it will? And, by the way, is there anything to prevent the neuropathy? You wiggle your fingers as if to emphasize the point. We go through each of your symptoms and strategize ways to make this cycle better than the last. “OK,” you conclude triumphantly. “I got this!”

It’s your 1-month follow-up and it’s time to pivot. After you were diagnosed with an aggressive triple-negative breast cancer, you met with a medical oncologist and a surgeon. Chemotherapy first, they agreed. The chemo would shrink the tumor, they said, so that it could all be scooped out with surgery. The medications were rough, but you knew it was for the best. But now it’s been two cycles and the lump in your breast is getting bigger not smaller. I ask if I may draw on your skin, promising I’ll wash it off. I gently trace the mass in pen and pull out a tape measure. Yes. It is bigger. I listen to your heart and hear it racing. “What now?” you ask.

When you saw your doctor for bloating and were told it’s not gas, actually, but stage 4 cancer, you didn’t cry. You didn’t deny it. You prepared. You called your lawyer and made a will. You contacted your job and planned for retirement. You organized your things so your children wouldn’t have to. Your oncologist recommended palliative chemotherapy as it could give you some more good days. The best case scenario would be 1 year. That was 2½ years ago. You still like to be prepared, you tell me, but that’s on the back burner now. You are busy, after all – your feet still ache from dancing all night in heels at your niece’s wedding last weekend. I pull up your latest PET scan and we look together: Again, wonderfully, everything appears stable. “See you in 3 months,” I say.

You called three times to move up this appointment because you didn’t know if you’d be alive this long. You want a second opinion. When your kidney cancer grew after surgery, two immunotherapy drugs, and a chemotherapy pill, the latest setback has been fevers up to 104 ° with drenching night sweats. They found a deep infection gnawing around the edges of your tumor, and antibiotics aren’t touching it. The only chance to stop the cancer is more chemotherapy, but that could make the infection worse and lead to a rapid demise. You can’t decide. Today, in the exam room, you are sweating. Your temperature is 101 °. Your partner is trying to keep it together, but the crumpled tissues in her hand give it away. She looks at me earnestly: “What would you do if this were your family member?”

You teach about this disease in your classes and never thought it would happen to you. It started simply enough – you were bruising. Your joints ached. Small things; odd things. The ER doctor cleverly noticed that some numbers were off in your blood counts and sent you to a hematology-oncology doctor, who then cleverly ordered a molecular blood test. It was a long shot. He didn’t really expect it to come back with chronic myeloid leukemia. But there it is, and here we are. You return to talk about treatment options. You understand in detail the biology of how they work. What you don’t know is which is best for you. I go through the four choices and unpleasant effects of each. Muscle aches; diarrhea; risk of bleeding; twice a day dosing tied to mealtimes. “Is there an Option 5?” you wonder.

You have been in the hospital for 34 days, but who’s counting? You are. Because it has been Thirty. Four. Days. You knew the chemotherapy would suppress your blood counts. Now you know what “impaired immune system” really means. You had the bloodstream bacterial infection, requiring 2 days in the ICU. You had the invasive fungus growing in your lungs. The nurses post a calendar on your wall and kindly fill it in every day with your white blood cell count so you don’t have to ask. For days, it’s the same. Your bag stays packed – “just in case,” you explain. Your spouse diligently keeps your children – 2 and 4 years old – away, as kids are notorious germ factories. Then one Sunday morning and – finally! “Put me on speakerphone,” you tell your spouse. “Daddy is coming home!”

One of the most precious parts of hematology and oncology is the relationships. You are there not just for one difficult moment, but for the journey. I await getting to help you over the years to come. For now, I will settle for snapshots.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz and listen to her each week on the Blood & Cancer podcast.

It’s 6:30 on a Friday night, and I am triaging three admissions to the leukemia service at once. The call from the ED about you makes me pause. I recognize your name – you were my patient a few years before. At the time, you were undergoing chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia, and I cared for you during the aftermath. I now pull up your chart and fill in the gaps of the last 2 years. You got into remission and received a bone marrow transplant. For 2 years, you were cured. But today, you are back. The ED has picked up an abundance of blasts – cancer cells – in your blood. I walk to your ED gurney slowly, thinking of how to tell you this. You recognize me, too. And I can see in your eyes that you already know. “I am so sorry this is happening,” I say.

You are here for your third cycle of chemotherapy. It’s a standard check-in. The first cycle was tolerable, the second cycle was rough, and now you are exhausted. You wonder if it’s normal to be so beat up from this. You ask how much nausea is too much nausea. But your hair didn’t fall out – isn’t that strange? Is it a sure thing that it will? And, by the way, is there anything to prevent the neuropathy? You wiggle your fingers as if to emphasize the point. We go through each of your symptoms and strategize ways to make this cycle better than the last. “OK,” you conclude triumphantly. “I got this!”

It’s your 1-month follow-up and it’s time to pivot. After you were diagnosed with an aggressive triple-negative breast cancer, you met with a medical oncologist and a surgeon. Chemotherapy first, they agreed. The chemo would shrink the tumor, they said, so that it could all be scooped out with surgery. The medications were rough, but you knew it was for the best. But now it’s been two cycles and the lump in your breast is getting bigger not smaller. I ask if I may draw on your skin, promising I’ll wash it off. I gently trace the mass in pen and pull out a tape measure. Yes. It is bigger. I listen to your heart and hear it racing. “What now?” you ask.

When you saw your doctor for bloating and were told it’s not gas, actually, but stage 4 cancer, you didn’t cry. You didn’t deny it. You prepared. You called your lawyer and made a will. You contacted your job and planned for retirement. You organized your things so your children wouldn’t have to. Your oncologist recommended palliative chemotherapy as it could give you some more good days. The best case scenario would be 1 year. That was 2½ years ago. You still like to be prepared, you tell me, but that’s on the back burner now. You are busy, after all – your feet still ache from dancing all night in heels at your niece’s wedding last weekend. I pull up your latest PET scan and we look together: Again, wonderfully, everything appears stable. “See you in 3 months,” I say.

You called three times to move up this appointment because you didn’t know if you’d be alive this long. You want a second opinion. When your kidney cancer grew after surgery, two immunotherapy drugs, and a chemotherapy pill, the latest setback has been fevers up to 104 ° with drenching night sweats. They found a deep infection gnawing around the edges of your tumor, and antibiotics aren’t touching it. The only chance to stop the cancer is more chemotherapy, but that could make the infection worse and lead to a rapid demise. You can’t decide. Today, in the exam room, you are sweating. Your temperature is 101 °. Your partner is trying to keep it together, but the crumpled tissues in her hand give it away. She looks at me earnestly: “What would you do if this were your family member?”

You teach about this disease in your classes and never thought it would happen to you. It started simply enough – you were bruising. Your joints ached. Small things; odd things. The ER doctor cleverly noticed that some numbers were off in your blood counts and sent you to a hematology-oncology doctor, who then cleverly ordered a molecular blood test. It was a long shot. He didn’t really expect it to come back with chronic myeloid leukemia. But there it is, and here we are. You return to talk about treatment options. You understand in detail the biology of how they work. What you don’t know is which is best for you. I go through the four choices and unpleasant effects of each. Muscle aches; diarrhea; risk of bleeding; twice a day dosing tied to mealtimes. “Is there an Option 5?” you wonder.

You have been in the hospital for 34 days, but who’s counting? You are. Because it has been Thirty. Four. Days. You knew the chemotherapy would suppress your blood counts. Now you know what “impaired immune system” really means. You had the bloodstream bacterial infection, requiring 2 days in the ICU. You had the invasive fungus growing in your lungs. The nurses post a calendar on your wall and kindly fill it in every day with your white blood cell count so you don’t have to ask. For days, it’s the same. Your bag stays packed – “just in case,” you explain. Your spouse diligently keeps your children – 2 and 4 years old – away, as kids are notorious germ factories. Then one Sunday morning and – finally! “Put me on speakerphone,” you tell your spouse. “Daddy is coming home!”

One of the most precious parts of hematology and oncology is the relationships. You are there not just for one difficult moment, but for the journey. I await getting to help you over the years to come. For now, I will settle for snapshots.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz and listen to her each week on the Blood & Cancer podcast.

It’s 6:30 on a Friday night, and I am triaging three admissions to the leukemia service at once. The call from the ED about you makes me pause. I recognize your name – you were my patient a few years before. At the time, you were undergoing chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia, and I cared for you during the aftermath. I now pull up your chart and fill in the gaps of the last 2 years. You got into remission and received a bone marrow transplant. For 2 years, you were cured. But today, you are back. The ED has picked up an abundance of blasts – cancer cells – in your blood. I walk to your ED gurney slowly, thinking of how to tell you this. You recognize me, too. And I can see in your eyes that you already know. “I am so sorry this is happening,” I say.

You are here for your third cycle of chemotherapy. It’s a standard check-in. The first cycle was tolerable, the second cycle was rough, and now you are exhausted. You wonder if it’s normal to be so beat up from this. You ask how much nausea is too much nausea. But your hair didn’t fall out – isn’t that strange? Is it a sure thing that it will? And, by the way, is there anything to prevent the neuropathy? You wiggle your fingers as if to emphasize the point. We go through each of your symptoms and strategize ways to make this cycle better than the last. “OK,” you conclude triumphantly. “I got this!”

It’s your 1-month follow-up and it’s time to pivot. After you were diagnosed with an aggressive triple-negative breast cancer, you met with a medical oncologist and a surgeon. Chemotherapy first, they agreed. The chemo would shrink the tumor, they said, so that it could all be scooped out with surgery. The medications were rough, but you knew it was for the best. But now it’s been two cycles and the lump in your breast is getting bigger not smaller. I ask if I may draw on your skin, promising I’ll wash it off. I gently trace the mass in pen and pull out a tape measure. Yes. It is bigger. I listen to your heart and hear it racing. “What now?” you ask.

When you saw your doctor for bloating and were told it’s not gas, actually, but stage 4 cancer, you didn’t cry. You didn’t deny it. You prepared. You called your lawyer and made a will. You contacted your job and planned for retirement. You organized your things so your children wouldn’t have to. Your oncologist recommended palliative chemotherapy as it could give you some more good days. The best case scenario would be 1 year. That was 2½ years ago. You still like to be prepared, you tell me, but that’s on the back burner now. You are busy, after all – your feet still ache from dancing all night in heels at your niece’s wedding last weekend. I pull up your latest PET scan and we look together: Again, wonderfully, everything appears stable. “See you in 3 months,” I say.

You called three times to move up this appointment because you didn’t know if you’d be alive this long. You want a second opinion. When your kidney cancer grew after surgery, two immunotherapy drugs, and a chemotherapy pill, the latest setback has been fevers up to 104 ° with drenching night sweats. They found a deep infection gnawing around the edges of your tumor, and antibiotics aren’t touching it. The only chance to stop the cancer is more chemotherapy, but that could make the infection worse and lead to a rapid demise. You can’t decide. Today, in the exam room, you are sweating. Your temperature is 101 °. Your partner is trying to keep it together, but the crumpled tissues in her hand give it away. She looks at me earnestly: “What would you do if this were your family member?”

You teach about this disease in your classes and never thought it would happen to you. It started simply enough – you were bruising. Your joints ached. Small things; odd things. The ER doctor cleverly noticed that some numbers were off in your blood counts and sent you to a hematology-oncology doctor, who then cleverly ordered a molecular blood test. It was a long shot. He didn’t really expect it to come back with chronic myeloid leukemia. But there it is, and here we are. You return to talk about treatment options. You understand in detail the biology of how they work. What you don’t know is which is best for you. I go through the four choices and unpleasant effects of each. Muscle aches; diarrhea; risk of bleeding; twice a day dosing tied to mealtimes. “Is there an Option 5?” you wonder.

You have been in the hospital for 34 days, but who’s counting? You are. Because it has been Thirty. Four. Days. You knew the chemotherapy would suppress your blood counts. Now you know what “impaired immune system” really means. You had the bloodstream bacterial infection, requiring 2 days in the ICU. You had the invasive fungus growing in your lungs. The nurses post a calendar on your wall and kindly fill it in every day with your white blood cell count so you don’t have to ask. For days, it’s the same. Your bag stays packed – “just in case,” you explain. Your spouse diligently keeps your children – 2 and 4 years old – away, as kids are notorious germ factories. Then one Sunday morning and – finally! “Put me on speakerphone,” you tell your spouse. “Daddy is coming home!”

One of the most precious parts of hematology and oncology is the relationships. You are there not just for one difficult moment, but for the journey. I await getting to help you over the years to come. For now, I will settle for snapshots.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz and listen to her each week on the Blood & Cancer podcast.

October 2019 Advances in Federal Mental Health Care

Click here to access October 2019 Advances in Federal Mental Health Care

Table of Contents

- Research News

- Open Clinical Trials for Veterans With Suicidal Ideation

- Validation of the Timberlawn Couple and Family Evaluation Scales-Self-Report in Veterans with PTSD

- Perceived Barriers and Facilitators of Clozapine Use: A National Survey of Veterans Affairs Prescribers

- Standardizing the Use of Mental Health Screening Instruments in Patients With Pain

- Assessing Refill Data Among Different Classes of Antidepressants

Click here to access October 2019 Advances in Federal Mental Health Care

Table of Contents

- Research News

- Open Clinical Trials for Veterans With Suicidal Ideation

- Validation of the Timberlawn Couple and Family Evaluation Scales-Self-Report in Veterans with PTSD

- Perceived Barriers and Facilitators of Clozapine Use: A National Survey of Veterans Affairs Prescribers

- Standardizing the Use of Mental Health Screening Instruments in Patients With Pain

- Assessing Refill Data Among Different Classes of Antidepressants

Click here to access October 2019 Advances in Federal Mental Health Care

Table of Contents

- Research News

- Open Clinical Trials for Veterans With Suicidal Ideation

- Validation of the Timberlawn Couple and Family Evaluation Scales-Self-Report in Veterans with PTSD

- Perceived Barriers and Facilitators of Clozapine Use: A National Survey of Veterans Affairs Prescribers

- Standardizing the Use of Mental Health Screening Instruments in Patients With Pain

- Assessing Refill Data Among Different Classes of Antidepressants

VA Health Care Facilities Enter a New Smoke-Free Era

The updated smoking policy goes into effect for employees, patients, visitors, volunteers, contractors, and vendors, whether they smoke cigarettes, cigars, pipes, or even electronic and vaping devices, and whenever they are on the grounds of VA health care facilities, including parking areas.

The new policy comes after the VA reviewed research on second- and thirdhand smoke and best practices in the health care industry. “There is no risk-free level of exposure to tobacco smoke,” the VA’s Smokefree website says. Overwhelming evidence shows exposure to secondhand smoke has significant medical risks. Moreover, a growing body of evidence shows exposure to thirdhand smoke (residual nicotine and other chemicals left on indoor surfaces) also is a health hazard. The residue is thought to react with indoor pollutants to create a toxic mix that clings long after smoking has stopped and cannot be eliminated by opening windows, or using fans, or other means of clearing rooms.

“We are not alone in recognizing the importance of creating a smoke-free campus,” said VA Secretary Robert Wilkie. He notes that as of 2014, 4000 health care facilities and 4 national health care systems in the US have implemented smoke-free grounds.

National Association of Government employees will begin implementing the policy as of October 1, and have until January 1, 2020, to fully comply. Smoking shelters will be closed, although each facility will independently determine the disposition of smoking areas and shelters.

The new policy does not mean anyone has to quit smoking but to encourage quitting, the VA offers resources, including www.publichealth.va.gov/smoking/quit/index.asp. More tips and tools are available at the Smokefree Veteran website: https://veterans.smokefree.gov. SmokefreeVET is a text-messaging program (https://veterans.smokefree.gov/tools-tips-vet/smokefreevet) that provides 24/7 support to help veterans quit for good. Employees can contact their facility for resources.

The policies are available at https://www.va.gov/health/smokefree.

The updated smoking policy goes into effect for employees, patients, visitors, volunteers, contractors, and vendors, whether they smoke cigarettes, cigars, pipes, or even electronic and vaping devices, and whenever they are on the grounds of VA health care facilities, including parking areas.

The new policy comes after the VA reviewed research on second- and thirdhand smoke and best practices in the health care industry. “There is no risk-free level of exposure to tobacco smoke,” the VA’s Smokefree website says. Overwhelming evidence shows exposure to secondhand smoke has significant medical risks. Moreover, a growing body of evidence shows exposure to thirdhand smoke (residual nicotine and other chemicals left on indoor surfaces) also is a health hazard. The residue is thought to react with indoor pollutants to create a toxic mix that clings long after smoking has stopped and cannot be eliminated by opening windows, or using fans, or other means of clearing rooms.

“We are not alone in recognizing the importance of creating a smoke-free campus,” said VA Secretary Robert Wilkie. He notes that as of 2014, 4000 health care facilities and 4 national health care systems in the US have implemented smoke-free grounds.

National Association of Government employees will begin implementing the policy as of October 1, and have until January 1, 2020, to fully comply. Smoking shelters will be closed, although each facility will independently determine the disposition of smoking areas and shelters.

The new policy does not mean anyone has to quit smoking but to encourage quitting, the VA offers resources, including www.publichealth.va.gov/smoking/quit/index.asp. More tips and tools are available at the Smokefree Veteran website: https://veterans.smokefree.gov. SmokefreeVET is a text-messaging program (https://veterans.smokefree.gov/tools-tips-vet/smokefreevet) that provides 24/7 support to help veterans quit for good. Employees can contact their facility for resources.

The policies are available at https://www.va.gov/health/smokefree.

The updated smoking policy goes into effect for employees, patients, visitors, volunteers, contractors, and vendors, whether they smoke cigarettes, cigars, pipes, or even electronic and vaping devices, and whenever they are on the grounds of VA health care facilities, including parking areas.

The new policy comes after the VA reviewed research on second- and thirdhand smoke and best practices in the health care industry. “There is no risk-free level of exposure to tobacco smoke,” the VA’s Smokefree website says. Overwhelming evidence shows exposure to secondhand smoke has significant medical risks. Moreover, a growing body of evidence shows exposure to thirdhand smoke (residual nicotine and other chemicals left on indoor surfaces) also is a health hazard. The residue is thought to react with indoor pollutants to create a toxic mix that clings long after smoking has stopped and cannot be eliminated by opening windows, or using fans, or other means of clearing rooms.

“We are not alone in recognizing the importance of creating a smoke-free campus,” said VA Secretary Robert Wilkie. He notes that as of 2014, 4000 health care facilities and 4 national health care systems in the US have implemented smoke-free grounds.

National Association of Government employees will begin implementing the policy as of October 1, and have until January 1, 2020, to fully comply. Smoking shelters will be closed, although each facility will independently determine the disposition of smoking areas and shelters.

The new policy does not mean anyone has to quit smoking but to encourage quitting, the VA offers resources, including www.publichealth.va.gov/smoking/quit/index.asp. More tips and tools are available at the Smokefree Veteran website: https://veterans.smokefree.gov. SmokefreeVET is a text-messaging program (https://veterans.smokefree.gov/tools-tips-vet/smokefreevet) that provides 24/7 support to help veterans quit for good. Employees can contact their facility for resources.

The policies are available at https://www.va.gov/health/smokefree.

Streaked Discoloration on the Upper Body

The Diagnosis: Bleomycin-Induced Flagellate Hyperpigmentation

Histopathology of the affected skin demonstrated a slight increase in collagen bundle thickness, a chronic dermal perivascular inflammation, and associated pigment incontinence with dermal melanophages compared to unaffected skin (Figure). CD34 was faintly decreased, and dermal mucin increased in affected skin. This postinflammatory pigmentary alteration with subtle dermal sclerosis had persisted unchanged for more than 5 years after cessation of bleomycin therapy. Topical hydroquinone, physical blocker photoprotection, and laser modalities such as the Q-switched alexandrite (755-nm)/Nd:YAG (1064-nm) and ablative CO2 resurfacing lasers were attempted with minimal overall impact on cosmesis.

Bleomycin is a chemotherapeutic antibiotic that has been commonly used to treat Hodgkin lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and recurrent malignant pleural effusions.1 The drug is inactivated in most tissues by the enzyme bleomycin hydrolase. This enzyme is not present in skin and lung tissue; as a result, these organs are the most common sites of bleomycin toxicity.1 There are a variety of cutaneous effects associated with bleomycin including alopecia, hyperpigmentation, acral erythema, Raynaud phenomenon, and nail dystrophy.2 Flagellate hyperpigmentation is a less common cutaneous toxicity. It is an unusual eruption that appears as whiplike linear streaks on the upper chest and back, limbs, and flanks.3 This cutaneous manifestation was once thought to be specific to bleomycin use; however, it also has been described in dermatomyositis, adult-onset Still disease, and after the ingestion of uncooked or undercooked shiitake mushrooms.4 Flagellate hyperpigmentation also was once thought to be dose dependent; however, it has been described in even very small doses.5 The eruption has been described as independent of the route of drug administration, appearing with intravenous, subcutaneous, and intramuscular bleomycin.2 The association of bleomycin and flagellate hyperpigmentation has been reported since 1970; however, it is less commonly seen in clinical practice with the declining use of bleomycin.1

The exact mechanism for the hyperpigmentation is unknown. It has been proposed that the linear lesions are related to areas of pruritus and subsequent excoriations.1 Dermatographism may be present to a limited extent, but it is unlikely to be a chief cause of flagellate hyperpigmentation, as linear streaks have been reported in the absence of trauma. It also has been proposed that bleomycin has a direct toxic effect on the melanocytes, which stimulates increased melanin secretion.2 The hyperpigmentation also may be due to pigmentary incontinence secondary to inflammation.5 Histopathologic findings usually are varied and nonspecific.2 There may be a deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, which is nonspecific but can be associated with drug-induced pathology.4 Bleomycin also is used to induce localized scleroderma in mouse-model research6 and has been reported to cause localized scleroderma at an infusion site or after an intralesional injection,7,8 which is not typically reported in flagellate erythema, but bleomycin's sclerosing effects may have played a role in the visible and sclerosing atrophy noted in our patient. Yamamoto et al9 reported a similar case of dermal sclerosis induced by bleomycin.

Flagellate hyperpigmentation typically lasts for up to 6 months.3 Patients with cutaneous manifestations from bleomycin therapy usually respond to steroid therapy and discontinuation of the drug. Bleomycin re-exposure should be avoided, as it may cause extension or widespread recurrence of flagellate hyperpigmentation.3 Postinflammatory pigment alteration may persist in patients with darker skin types and in patients with dramatic inciting inflammation.

Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini is a form of dermal atrophy that presents with 1 or more sharply demarcated depressed patches. There is some debate whether it is a distinct entity or a primary atrophic morphea.10 Linear atrophoderma of Moulin has a similar morphology with hyperpigmented depressions and "cliff-drop" borders, but these lesions follow the lines of Blaschko.11 Linear morphea initially can present as a linear erythematous streak but more commonly appears as a plaque-type morphea lesion that forms a scarlike band.12 Erythema dyschromicum perstans is an ashy dermatosis characterized by gray or blue-brown macules seen in Fitzpatrick skin types III through V and typically is chronic and progressive.13

- Lee HY, Lim KH, Ryu Y, et al. Bleomycininduced flagellate erythema: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:933-935.

- Simpson RC, Da Forno P, Nagarajan C, et al. A pruritic rash in a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:680-682.

- Fyfe AJ, McKay P. Toxicities associated with bleomycin. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2010;40:213-215.

- Lu CC, Lu YY, Wang QR, et al. Bleomycin-induced flagellate erythema. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:189-190.

- Abess A, Keel DM, Graham BS. Flagellate hyperpigmentation following intralesional bleomycin treatment of verruca plantaris. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:337-339.

- Yamamoto T. The bleomycin-induced scleroderma model: what have we learned for scleroderma pathogenesis? Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;297:333-344.

- Kim KH, Yoon TJ, Oh CW, et al. A case of bleomycin-induced scleroderma. J Korean Med Sci. 1996;11:454-456.

- Kerr LD, Spiera H. Scleroderma in association with the use of bleomycin: a report of 3 cases. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:294-296.

- Yamamoto T, Yokozeki H, Nishioka K. Dermal sclerosis in the lesional skin of 'flagellate' erythema (scratch dermatitis) induced by bleomycin. Dermatology. 1998;197:399-400.

- Kencka D, Blaszczyk M, Jablońska S. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini is a primary atrophic abortive morphea. Dermatology. 1995;190:203-206.

- Moulin G, Hill MP, Guillaud V, et al. Acquired atrophic pigmented band-like lesions following Blaschko's lines. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1992;119:729-736.

- Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228.

- Zaynoun S, Rubeiz N, Kibbi AG. Ashy dermatosis--a critical review of literature and a proposed simplified clinical classification. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:542-544.

The Diagnosis: Bleomycin-Induced Flagellate Hyperpigmentation

Histopathology of the affected skin demonstrated a slight increase in collagen bundle thickness, a chronic dermal perivascular inflammation, and associated pigment incontinence with dermal melanophages compared to unaffected skin (Figure). CD34 was faintly decreased, and dermal mucin increased in affected skin. This postinflammatory pigmentary alteration with subtle dermal sclerosis had persisted unchanged for more than 5 years after cessation of bleomycin therapy. Topical hydroquinone, physical blocker photoprotection, and laser modalities such as the Q-switched alexandrite (755-nm)/Nd:YAG (1064-nm) and ablative CO2 resurfacing lasers were attempted with minimal overall impact on cosmesis.

Bleomycin is a chemotherapeutic antibiotic that has been commonly used to treat Hodgkin lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and recurrent malignant pleural effusions.1 The drug is inactivated in most tissues by the enzyme bleomycin hydrolase. This enzyme is not present in skin and lung tissue; as a result, these organs are the most common sites of bleomycin toxicity.1 There are a variety of cutaneous effects associated with bleomycin including alopecia, hyperpigmentation, acral erythema, Raynaud phenomenon, and nail dystrophy.2 Flagellate hyperpigmentation is a less common cutaneous toxicity. It is an unusual eruption that appears as whiplike linear streaks on the upper chest and back, limbs, and flanks.3 This cutaneous manifestation was once thought to be specific to bleomycin use; however, it also has been described in dermatomyositis, adult-onset Still disease, and after the ingestion of uncooked or undercooked shiitake mushrooms.4 Flagellate hyperpigmentation also was once thought to be dose dependent; however, it has been described in even very small doses.5 The eruption has been described as independent of the route of drug administration, appearing with intravenous, subcutaneous, and intramuscular bleomycin.2 The association of bleomycin and flagellate hyperpigmentation has been reported since 1970; however, it is less commonly seen in clinical practice with the declining use of bleomycin.1

The exact mechanism for the hyperpigmentation is unknown. It has been proposed that the linear lesions are related to areas of pruritus and subsequent excoriations.1 Dermatographism may be present to a limited extent, but it is unlikely to be a chief cause of flagellate hyperpigmentation, as linear streaks have been reported in the absence of trauma. It also has been proposed that bleomycin has a direct toxic effect on the melanocytes, which stimulates increased melanin secretion.2 The hyperpigmentation also may be due to pigmentary incontinence secondary to inflammation.5 Histopathologic findings usually are varied and nonspecific.2 There may be a deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, which is nonspecific but can be associated with drug-induced pathology.4 Bleomycin also is used to induce localized scleroderma in mouse-model research6 and has been reported to cause localized scleroderma at an infusion site or after an intralesional injection,7,8 which is not typically reported in flagellate erythema, but bleomycin's sclerosing effects may have played a role in the visible and sclerosing atrophy noted in our patient. Yamamoto et al9 reported a similar case of dermal sclerosis induced by bleomycin.

Flagellate hyperpigmentation typically lasts for up to 6 months.3 Patients with cutaneous manifestations from bleomycin therapy usually respond to steroid therapy and discontinuation of the drug. Bleomycin re-exposure should be avoided, as it may cause extension or widespread recurrence of flagellate hyperpigmentation.3 Postinflammatory pigment alteration may persist in patients with darker skin types and in patients with dramatic inciting inflammation.

Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini is a form of dermal atrophy that presents with 1 or more sharply demarcated depressed patches. There is some debate whether it is a distinct entity or a primary atrophic morphea.10 Linear atrophoderma of Moulin has a similar morphology with hyperpigmented depressions and "cliff-drop" borders, but these lesions follow the lines of Blaschko.11 Linear morphea initially can present as a linear erythematous streak but more commonly appears as a plaque-type morphea lesion that forms a scarlike band.12 Erythema dyschromicum perstans is an ashy dermatosis characterized by gray or blue-brown macules seen in Fitzpatrick skin types III through V and typically is chronic and progressive.13

The Diagnosis: Bleomycin-Induced Flagellate Hyperpigmentation

Histopathology of the affected skin demonstrated a slight increase in collagen bundle thickness, a chronic dermal perivascular inflammation, and associated pigment incontinence with dermal melanophages compared to unaffected skin (Figure). CD34 was faintly decreased, and dermal mucin increased in affected skin. This postinflammatory pigmentary alteration with subtle dermal sclerosis had persisted unchanged for more than 5 years after cessation of bleomycin therapy. Topical hydroquinone, physical blocker photoprotection, and laser modalities such as the Q-switched alexandrite (755-nm)/Nd:YAG (1064-nm) and ablative CO2 resurfacing lasers were attempted with minimal overall impact on cosmesis.

Bleomycin is a chemotherapeutic antibiotic that has been commonly used to treat Hodgkin lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and recurrent malignant pleural effusions.1 The drug is inactivated in most tissues by the enzyme bleomycin hydrolase. This enzyme is not present in skin and lung tissue; as a result, these organs are the most common sites of bleomycin toxicity.1 There are a variety of cutaneous effects associated with bleomycin including alopecia, hyperpigmentation, acral erythema, Raynaud phenomenon, and nail dystrophy.2 Flagellate hyperpigmentation is a less common cutaneous toxicity. It is an unusual eruption that appears as whiplike linear streaks on the upper chest and back, limbs, and flanks.3 This cutaneous manifestation was once thought to be specific to bleomycin use; however, it also has been described in dermatomyositis, adult-onset Still disease, and after the ingestion of uncooked or undercooked shiitake mushrooms.4 Flagellate hyperpigmentation also was once thought to be dose dependent; however, it has been described in even very small doses.5 The eruption has been described as independent of the route of drug administration, appearing with intravenous, subcutaneous, and intramuscular bleomycin.2 The association of bleomycin and flagellate hyperpigmentation has been reported since 1970; however, it is less commonly seen in clinical practice with the declining use of bleomycin.1

The exact mechanism for the hyperpigmentation is unknown. It has been proposed that the linear lesions are related to areas of pruritus and subsequent excoriations.1 Dermatographism may be present to a limited extent, but it is unlikely to be a chief cause of flagellate hyperpigmentation, as linear streaks have been reported in the absence of trauma. It also has been proposed that bleomycin has a direct toxic effect on the melanocytes, which stimulates increased melanin secretion.2 The hyperpigmentation also may be due to pigmentary incontinence secondary to inflammation.5 Histopathologic findings usually are varied and nonspecific.2 There may be a deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, which is nonspecific but can be associated with drug-induced pathology.4 Bleomycin also is used to induce localized scleroderma in mouse-model research6 and has been reported to cause localized scleroderma at an infusion site or after an intralesional injection,7,8 which is not typically reported in flagellate erythema, but bleomycin's sclerosing effects may have played a role in the visible and sclerosing atrophy noted in our patient. Yamamoto et al9 reported a similar case of dermal sclerosis induced by bleomycin.

Flagellate hyperpigmentation typically lasts for up to 6 months.3 Patients with cutaneous manifestations from bleomycin therapy usually respond to steroid therapy and discontinuation of the drug. Bleomycin re-exposure should be avoided, as it may cause extension or widespread recurrence of flagellate hyperpigmentation.3 Postinflammatory pigment alteration may persist in patients with darker skin types and in patients with dramatic inciting inflammation.

Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini is a form of dermal atrophy that presents with 1 or more sharply demarcated depressed patches. There is some debate whether it is a distinct entity or a primary atrophic morphea.10 Linear atrophoderma of Moulin has a similar morphology with hyperpigmented depressions and "cliff-drop" borders, but these lesions follow the lines of Blaschko.11 Linear morphea initially can present as a linear erythematous streak but more commonly appears as a plaque-type morphea lesion that forms a scarlike band.12 Erythema dyschromicum perstans is an ashy dermatosis characterized by gray or blue-brown macules seen in Fitzpatrick skin types III through V and typically is chronic and progressive.13

- Lee HY, Lim KH, Ryu Y, et al. Bleomycininduced flagellate erythema: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:933-935.

- Simpson RC, Da Forno P, Nagarajan C, et al. A pruritic rash in a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:680-682.

- Fyfe AJ, McKay P. Toxicities associated with bleomycin. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2010;40:213-215.

- Lu CC, Lu YY, Wang QR, et al. Bleomycin-induced flagellate erythema. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:189-190.

- Abess A, Keel DM, Graham BS. Flagellate hyperpigmentation following intralesional bleomycin treatment of verruca plantaris. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:337-339.

- Yamamoto T. The bleomycin-induced scleroderma model: what have we learned for scleroderma pathogenesis? Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;297:333-344.

- Kim KH, Yoon TJ, Oh CW, et al. A case of bleomycin-induced scleroderma. J Korean Med Sci. 1996;11:454-456.

- Kerr LD, Spiera H. Scleroderma in association with the use of bleomycin: a report of 3 cases. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:294-296.

- Yamamoto T, Yokozeki H, Nishioka K. Dermal sclerosis in the lesional skin of 'flagellate' erythema (scratch dermatitis) induced by bleomycin. Dermatology. 1998;197:399-400.

- Kencka D, Blaszczyk M, Jablońska S. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini is a primary atrophic abortive morphea. Dermatology. 1995;190:203-206.

- Moulin G, Hill MP, Guillaud V, et al. Acquired atrophic pigmented band-like lesions following Blaschko's lines. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1992;119:729-736.

- Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228.

- Zaynoun S, Rubeiz N, Kibbi AG. Ashy dermatosis--a critical review of literature and a proposed simplified clinical classification. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:542-544.

- Lee HY, Lim KH, Ryu Y, et al. Bleomycininduced flagellate erythema: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:933-935.

- Simpson RC, Da Forno P, Nagarajan C, et al. A pruritic rash in a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:680-682.

- Fyfe AJ, McKay P. Toxicities associated with bleomycin. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2010;40:213-215.

- Lu CC, Lu YY, Wang QR, et al. Bleomycin-induced flagellate erythema. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:189-190.

- Abess A, Keel DM, Graham BS. Flagellate hyperpigmentation following intralesional bleomycin treatment of verruca plantaris. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:337-339.

- Yamamoto T. The bleomycin-induced scleroderma model: what have we learned for scleroderma pathogenesis? Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;297:333-344.

- Kim KH, Yoon TJ, Oh CW, et al. A case of bleomycin-induced scleroderma. J Korean Med Sci. 1996;11:454-456.

- Kerr LD, Spiera H. Scleroderma in association with the use of bleomycin: a report of 3 cases. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:294-296.

- Yamamoto T, Yokozeki H, Nishioka K. Dermal sclerosis in the lesional skin of 'flagellate' erythema (scratch dermatitis) induced by bleomycin. Dermatology. 1998;197:399-400.

- Kencka D, Blaszczyk M, Jablońska S. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini is a primary atrophic abortive morphea. Dermatology. 1995;190:203-206.

- Moulin G, Hill MP, Guillaud V, et al. Acquired atrophic pigmented band-like lesions following Blaschko's lines. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1992;119:729-736.

- Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228.

- Zaynoun S, Rubeiz N, Kibbi AG. Ashy dermatosis--a critical review of literature and a proposed simplified clinical classification. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:542-544.

An 18-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with persistent diffuse discoloration on the upper body of more than 5 years’ duration. Her medical history was notable for primary mediastinal classical Hodgkin lymphoma treated with ABVE-PC (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vincristine, etoposide, prednisone, cyclophosphamide) chemotherapy and 22 Gy radiation therapy to the chest 5 years prior. She reported the initial onset of diffuse pruritus with associated scratching and persistent skin discoloration while receiving a course of chemotherapy. Physical examination revealed numerous thin, flagellate, faintly hyperpigmented streaks with subtle atrophy in a parallel configuration on the bilateral shoulders (top), upper back (bottom), and abdomen. Punch biopsies (5 mm) of both affected and unaffected skin on the left side of the lateral upper back were performed.

When providing contraceptive counseling to women with migraine headaches, how do you identify migraine with aura?

Most physicians know that migraine with aura is a risk factor for ischemic stroke and that the use of an estrogen-containing contraceptive further increases this risk.1-3 Additional important and prevalent risk factors for ischemic stroke include cigarette smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and ischemic heart disease.1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)2 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)3 recommend against the use of estrogen-containing contraceptives for women with migraine with aura because of the increased risk of ischemic stroke (Medical Eligibility Criteria [MEC] category 4—unacceptable health risk, method not to be used).

However, those who have migraine with aura can use nonhormonal and progestin-only forms of contraception, including copper- and levonorgestrel-intrauterine devices, the etonogestrel subdermal implant, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and progestin-only pills (MEC category 1—no restriction).2,3 ACOG and the CDC advise that estrogen-containing contraceptives can be used for those with migraine without aura who have no other risk factors for stroke (MEC category 2—advantages generally outweigh theoretical or proven risks).2,3 Given the high prevalence of migraine in reproductive-age women, accurate diagnosis of aura is of paramount importance in order to provide appropriate contraceptive counseling.

When is migraine with aura the right diagnosis?

In clinical practice, there is a high level of confusion about the migraine symptoms that warrant a diagnosis of migraine with aura. One approach to improving the accuracy of such a diagnosis is to refer every woman seeking contraceptive counseling who has migraine headaches to a neurologist for expert adjudication of the presence or absence of aura. But in the clinical context of contraceptive counseling, neurology consultation is not always readily available, and requiring consultation increases barriers to care. However, there are tools—such as the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS), which is discussed below—that may help non-neurologists identify migraine with aura.4 First, let us review the data that links migraine with aura with increased risk of ischemic stroke.

Migraine with aura is a risk factor for stroke

Multiple case-control studies report that migraine with aura is a risk factor for ischemic stroke.1,5,6 Studies also report that women with migraine with aura who use estrogen-containing contraceptives have an even greater risk of ischemic stroke. For example, one recent case-control study used a commercial claims database of 1,884 cases of ischemic stroke among individuals who identify as women 15 to 49 years of age matched to 7,536 controls without ischemic stroke.1 In this study, the risk of ischemic stroke was increased more than 2.5-fold by cigarette smoking (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.59), hypertension (aOR, 2.73), diabetes (aOR, 2.78), migraine with aura (aOR, 2.89), and ischemic heart disease (aOR, 5.49). For those with migraine with aura who also used an estrogen-containing contraceptive, the aOR for ischemic stroke was 6.08. By contrast, the risk for stroke among those with migraine with aura who were not using an estrogen-containing contraceptive was 2.65. Furthermore, among those with migraine without aura, the risk of ischemic stroke was only 1.77 with the use of an estrogen-containing contraceptive.

Continue to: Although women with migraine...

Although women with migraine with and without aura are at increased risk for stroke, the absolute risk is still very low. For example, one review reported that the incidence of ischemic stroke per 100,000 person-years among women 20 to 44 years of age was 2.5 for those without migraine not taking estrogen-containing contraceptives, 5.9 for those with migraine with aura not taking estrogen-containing contraceptives, and 14.5 among those with migraine with aura and taking estrogen-containing contraceptives.6 Another important observation is that the incidence of thrombotic stroke dramatically increases from adolescence (3.4 per 100,000 person-years) to 45-49 years of age (64.4 per 100,000 person-years).7 Therefore, older women with migraine are at greater risk for stroke than adolescents.

Diagnostic criteria for migraine with and without aura

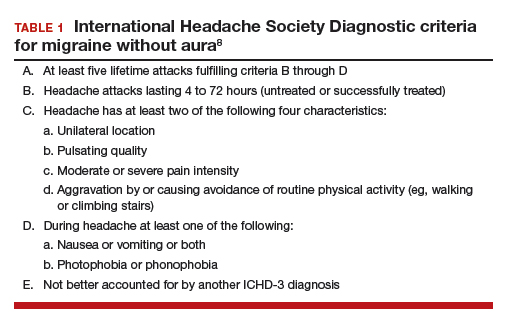

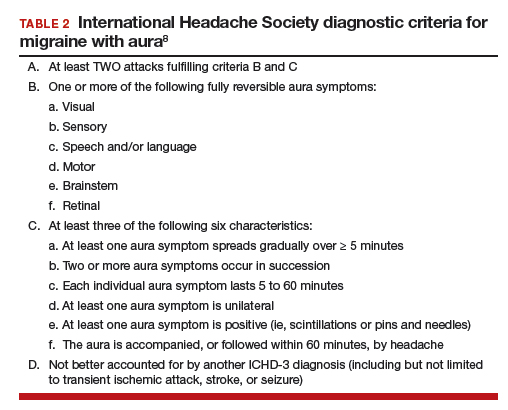

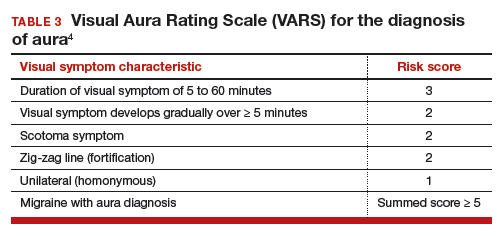

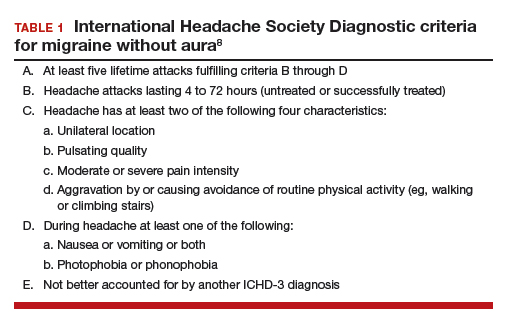

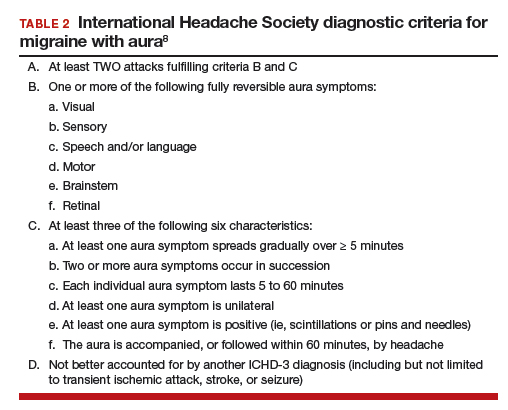

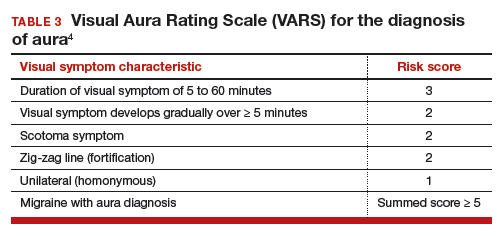

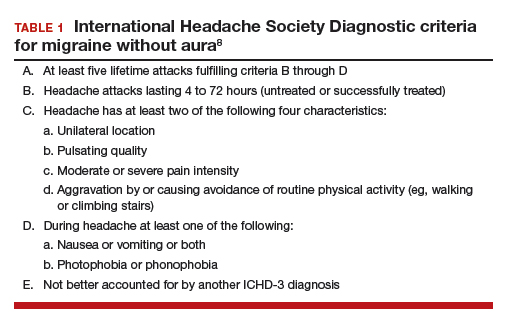

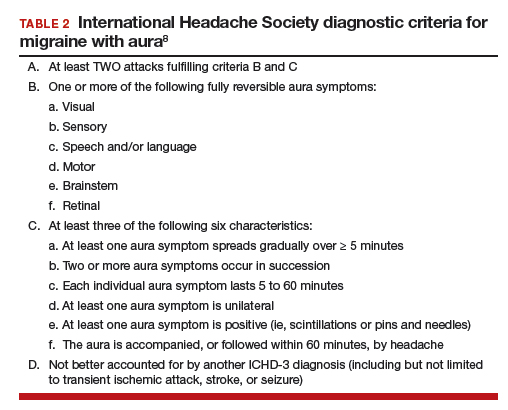

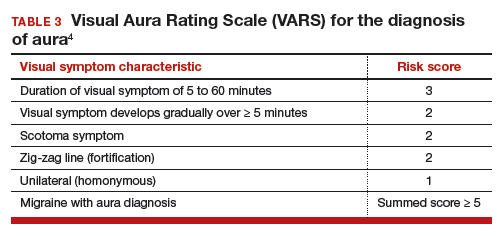

In contraceptive counseling, if an estrogen-containing contraceptive is being considered, it is important to identify women with migraine headache, determine migraine subtype, assess the frequency of migraines and identify other cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and cigarette smoking. The International Headache Society has evolved the diagnostic criteria for migraine with and without aura, and now endorses the criteria published in the 3rd edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3; TABLES 1 and 2).8 For non-neurologists, these criteria may be difficult to remember and impractical to utilize in daily contraceptive counseling. Two simplified tools, the ID Migraine Questionnaire9 and the Visual Aura Rating Scale (TABLE 3)4 may help identify women who have migraine headaches and assess for the presence of aura.

The ID Migraine Questionnaire

In a study of 563 people seeking primary care who had headaches in the past 3 months, 3 questions were identified as being helpful in identifying women with migraine. This 3-question screening tool had reasonable sensitivity (81%), specificity (75%), and positive predictive value (93%) compared with expert diagnosis using the ICHD-3.9 The 3 questions in this screening tool, which are answered “Yes” or “No,” are:

During the last 3 months did you have the following symptoms with your headaches:

- Feel nauseated or sick to your stomach?

- Light bothered you?

- Your headaches limited your ability to work, study or do what you needed to do for at least 1 day?

If two questions are answered “Yes” the patient may have migraine headaches.

Visual Aura Rating Scale for the diagnosis of migraine with aura

More than 90% of women with migraine with aura have visual auras, leaving only a minority with non–visual aura, such as tingling or numbness in a limb, speech or language problems, or muscle weakness. Hence for non-neurologists, it is reasonable to focus on the accurate diagnosis of visual aura to identify those with migraine with aura.

In the clinical context of contraceptive counseling, the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS) is especially useful because it has good sensitivity and specificity, and it is easy to use in practice (TABLE 3).4 VARS assesses for 5 characteristics of a visual aura, and each characteristic is associated with a weighted risk score. The 5 symptoms assessed include:

- duration of visual symptom between 5 and 60 minutes (3 points)

- visual symptom develops gradually over 5 minutes (2 points)

- scotoma (2 points)

- zig-zag line (2 points)

- unilateral (1 point).

Continue to: Of note, visual aura is usually...

Of note, visual aura is usually slow-spreading and persists for more than 5 minutes but less than 60 minutes. If a visual symptom has a sudden onset and persists for much longer than 60 minutes, concern is heightened for a more serious neurologic diagnosis such as transient ischemic attack or stroke. A summed score of 5 or more points supports the diagnosis of migraine with aura. In one study, VARS had a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 96% for identifying women with migraine with aura diagnosed by the ICHD-3 criteria.4

Consider using VARS to identify migraine with aura

Epidemiologic studies report that about 17% of adults have migraine, and about 5% have migraine with aura.10,11 Consequently, migraine with aura is one of the most common medical conditions encountered during contraceptive counseling. The CDC MEC recommend against the use of estrogen-containing contraceptives in women with migraine with aura (Category 4 rating). The VARS may help clinicians identify those who have migraine with aura who should not be offered estrogen-containing contraceptives. Equally important, the use of VARS could help reduce the number of women who are inappropriately diagnosed as having migraine with aura based on fleeting visual symptoms lasting far less than 5 minutes during a migraine headache.

- Champaloux SW, Tepper NK, Monsour M, et al. Use of combined hormonal contraceptives among women with migraine and risk of ischemic stroke. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:489.e1-e7.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 206: use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e128-e150.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Eriksen MK, Thomsen LL, Olesen J. The Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS) for migraine aura diagnosis. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:801-810.

- Schürks M, Rist PM, Bigal ME, et al. Migraine and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b3914.

- Sacco S, Merki-Feld G, Aegidius KL, et al. Hormonal contraceptives and risk of ischemic stroke in women with migraine: a consensus statement from the European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESC). J Headache Pain. 2017;18:108.

- Lidegaard Ø, Lokkegaard E, Jensen A, et al. Thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction with hormonal contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2257-2266.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1-211.

- Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky R, et al. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care: the ID Migraine validation study. Neurology. 2003;12;61:375-382.

- Lipton RB, Scher AI, Kolodner K, et al. Migraine in the United States: epidemiology and patterns of health care use. Neurology. 2002;58:885-894.

- Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al; AMPP Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343-349.

Most physicians know that migraine with aura is a risk factor for ischemic stroke and that the use of an estrogen-containing contraceptive further increases this risk.1-3 Additional important and prevalent risk factors for ischemic stroke include cigarette smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and ischemic heart disease.1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)2 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)3 recommend against the use of estrogen-containing contraceptives for women with migraine with aura because of the increased risk of ischemic stroke (Medical Eligibility Criteria [MEC] category 4—unacceptable health risk, method not to be used).

However, those who have migraine with aura can use nonhormonal and progestin-only forms of contraception, including copper- and levonorgestrel-intrauterine devices, the etonogestrel subdermal implant, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and progestin-only pills (MEC category 1—no restriction).2,3 ACOG and the CDC advise that estrogen-containing contraceptives can be used for those with migraine without aura who have no other risk factors for stroke (MEC category 2—advantages generally outweigh theoretical or proven risks).2,3 Given the high prevalence of migraine in reproductive-age women, accurate diagnosis of aura is of paramount importance in order to provide appropriate contraceptive counseling.

When is migraine with aura the right diagnosis?

In clinical practice, there is a high level of confusion about the migraine symptoms that warrant a diagnosis of migraine with aura. One approach to improving the accuracy of such a diagnosis is to refer every woman seeking contraceptive counseling who has migraine headaches to a neurologist for expert adjudication of the presence or absence of aura. But in the clinical context of contraceptive counseling, neurology consultation is not always readily available, and requiring consultation increases barriers to care. However, there are tools—such as the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS), which is discussed below—that may help non-neurologists identify migraine with aura.4 First, let us review the data that links migraine with aura with increased risk of ischemic stroke.

Migraine with aura is a risk factor for stroke

Multiple case-control studies report that migraine with aura is a risk factor for ischemic stroke.1,5,6 Studies also report that women with migraine with aura who use estrogen-containing contraceptives have an even greater risk of ischemic stroke. For example, one recent case-control study used a commercial claims database of 1,884 cases of ischemic stroke among individuals who identify as women 15 to 49 years of age matched to 7,536 controls without ischemic stroke.1 In this study, the risk of ischemic stroke was increased more than 2.5-fold by cigarette smoking (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.59), hypertension (aOR, 2.73), diabetes (aOR, 2.78), migraine with aura (aOR, 2.89), and ischemic heart disease (aOR, 5.49). For those with migraine with aura who also used an estrogen-containing contraceptive, the aOR for ischemic stroke was 6.08. By contrast, the risk for stroke among those with migraine with aura who were not using an estrogen-containing contraceptive was 2.65. Furthermore, among those with migraine without aura, the risk of ischemic stroke was only 1.77 with the use of an estrogen-containing contraceptive.

Continue to: Although women with migraine...

Although women with migraine with and without aura are at increased risk for stroke, the absolute risk is still very low. For example, one review reported that the incidence of ischemic stroke per 100,000 person-years among women 20 to 44 years of age was 2.5 for those without migraine not taking estrogen-containing contraceptives, 5.9 for those with migraine with aura not taking estrogen-containing contraceptives, and 14.5 among those with migraine with aura and taking estrogen-containing contraceptives.6 Another important observation is that the incidence of thrombotic stroke dramatically increases from adolescence (3.4 per 100,000 person-years) to 45-49 years of age (64.4 per 100,000 person-years).7 Therefore, older women with migraine are at greater risk for stroke than adolescents.

Diagnostic criteria for migraine with and without aura

In contraceptive counseling, if an estrogen-containing contraceptive is being considered, it is important to identify women with migraine headache, determine migraine subtype, assess the frequency of migraines and identify other cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and cigarette smoking. The International Headache Society has evolved the diagnostic criteria for migraine with and without aura, and now endorses the criteria published in the 3rd edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3; TABLES 1 and 2).8 For non-neurologists, these criteria may be difficult to remember and impractical to utilize in daily contraceptive counseling. Two simplified tools, the ID Migraine Questionnaire9 and the Visual Aura Rating Scale (TABLE 3)4 may help identify women who have migraine headaches and assess for the presence of aura.

The ID Migraine Questionnaire

In a study of 563 people seeking primary care who had headaches in the past 3 months, 3 questions were identified as being helpful in identifying women with migraine. This 3-question screening tool had reasonable sensitivity (81%), specificity (75%), and positive predictive value (93%) compared with expert diagnosis using the ICHD-3.9 The 3 questions in this screening tool, which are answered “Yes” or “No,” are:

During the last 3 months did you have the following symptoms with your headaches:

- Feel nauseated or sick to your stomach?

- Light bothered you?

- Your headaches limited your ability to work, study or do what you needed to do for at least 1 day?

If two questions are answered “Yes” the patient may have migraine headaches.

Visual Aura Rating Scale for the diagnosis of migraine with aura

More than 90% of women with migraine with aura have visual auras, leaving only a minority with non–visual aura, such as tingling or numbness in a limb, speech or language problems, or muscle weakness. Hence for non-neurologists, it is reasonable to focus on the accurate diagnosis of visual aura to identify those with migraine with aura.

In the clinical context of contraceptive counseling, the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS) is especially useful because it has good sensitivity and specificity, and it is easy to use in practice (TABLE 3).4 VARS assesses for 5 characteristics of a visual aura, and each characteristic is associated with a weighted risk score. The 5 symptoms assessed include:

- duration of visual symptom between 5 and 60 minutes (3 points)

- visual symptom develops gradually over 5 minutes (2 points)

- scotoma (2 points)

- zig-zag line (2 points)

- unilateral (1 point).

Continue to: Of note, visual aura is usually...

Of note, visual aura is usually slow-spreading and persists for more than 5 minutes but less than 60 minutes. If a visual symptom has a sudden onset and persists for much longer than 60 minutes, concern is heightened for a more serious neurologic diagnosis such as transient ischemic attack or stroke. A summed score of 5 or more points supports the diagnosis of migraine with aura. In one study, VARS had a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 96% for identifying women with migraine with aura diagnosed by the ICHD-3 criteria.4

Consider using VARS to identify migraine with aura

Epidemiologic studies report that about 17% of adults have migraine, and about 5% have migraine with aura.10,11 Consequently, migraine with aura is one of the most common medical conditions encountered during contraceptive counseling. The CDC MEC recommend against the use of estrogen-containing contraceptives in women with migraine with aura (Category 4 rating). The VARS may help clinicians identify those who have migraine with aura who should not be offered estrogen-containing contraceptives. Equally important, the use of VARS could help reduce the number of women who are inappropriately diagnosed as having migraine with aura based on fleeting visual symptoms lasting far less than 5 minutes during a migraine headache.

Most physicians know that migraine with aura is a risk factor for ischemic stroke and that the use of an estrogen-containing contraceptive further increases this risk.1-3 Additional important and prevalent risk factors for ischemic stroke include cigarette smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and ischemic heart disease.1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)2 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)3 recommend against the use of estrogen-containing contraceptives for women with migraine with aura because of the increased risk of ischemic stroke (Medical Eligibility Criteria [MEC] category 4—unacceptable health risk, method not to be used).

However, those who have migraine with aura can use nonhormonal and progestin-only forms of contraception, including copper- and levonorgestrel-intrauterine devices, the etonogestrel subdermal implant, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and progestin-only pills (MEC category 1—no restriction).2,3 ACOG and the CDC advise that estrogen-containing contraceptives can be used for those with migraine without aura who have no other risk factors for stroke (MEC category 2—advantages generally outweigh theoretical or proven risks).2,3 Given the high prevalence of migraine in reproductive-age women, accurate diagnosis of aura is of paramount importance in order to provide appropriate contraceptive counseling.

When is migraine with aura the right diagnosis?

In clinical practice, there is a high level of confusion about the migraine symptoms that warrant a diagnosis of migraine with aura. One approach to improving the accuracy of such a diagnosis is to refer every woman seeking contraceptive counseling who has migraine headaches to a neurologist for expert adjudication of the presence or absence of aura. But in the clinical context of contraceptive counseling, neurology consultation is not always readily available, and requiring consultation increases barriers to care. However, there are tools—such as the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS), which is discussed below—that may help non-neurologists identify migraine with aura.4 First, let us review the data that links migraine with aura with increased risk of ischemic stroke.

Migraine with aura is a risk factor for stroke

Multiple case-control studies report that migraine with aura is a risk factor for ischemic stroke.1,5,6 Studies also report that women with migraine with aura who use estrogen-containing contraceptives have an even greater risk of ischemic stroke. For example, one recent case-control study used a commercial claims database of 1,884 cases of ischemic stroke among individuals who identify as women 15 to 49 years of age matched to 7,536 controls without ischemic stroke.1 In this study, the risk of ischemic stroke was increased more than 2.5-fold by cigarette smoking (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.59), hypertension (aOR, 2.73), diabetes (aOR, 2.78), migraine with aura (aOR, 2.89), and ischemic heart disease (aOR, 5.49). For those with migraine with aura who also used an estrogen-containing contraceptive, the aOR for ischemic stroke was 6.08. By contrast, the risk for stroke among those with migraine with aura who were not using an estrogen-containing contraceptive was 2.65. Furthermore, among those with migraine without aura, the risk of ischemic stroke was only 1.77 with the use of an estrogen-containing contraceptive.

Continue to: Although women with migraine...

Although women with migraine with and without aura are at increased risk for stroke, the absolute risk is still very low. For example, one review reported that the incidence of ischemic stroke per 100,000 person-years among women 20 to 44 years of age was 2.5 for those without migraine not taking estrogen-containing contraceptives, 5.9 for those with migraine with aura not taking estrogen-containing contraceptives, and 14.5 among those with migraine with aura and taking estrogen-containing contraceptives.6 Another important observation is that the incidence of thrombotic stroke dramatically increases from adolescence (3.4 per 100,000 person-years) to 45-49 years of age (64.4 per 100,000 person-years).7 Therefore, older women with migraine are at greater risk for stroke than adolescents.

Diagnostic criteria for migraine with and without aura